Abstract

Cryopreserved peripheral blood stem cell (PBSC) products can induce a number of infusion-related adverse reactions, including life-threatening cardiac, neurologic and other end-organ complications. Preliminary analyses suggested limiting the daily total nucleated cell dose infused might decrease the incidence of these adverse effects. A policy change implemented in December 2007, limiting the TNC dose to <1.63 × 109 TNC/kg/day, allowed us to assess the impact of this intervention on infusion-related safety, infusion schedules, engraftment and costs in cohorts of patients undergoing autologous stem cell transplants (ASCTs) two years before (325 ASCTs in 288 patients) and two years after the policy change (519 ASCTs in 479 patients). The percentage of autologous transplant patients requiring multiple day infusions increased from 6% to 24%. Concurrently, the incidence of infusion-related grade 3–5 SAEs decreased significantly, from 4% (13/325) pre-policy change to 0.6 % (3/519) post-policy change (p<0.0004). Multi-day infusions were not associated with increased time to neutrophil or platelet engraftment or the costs of transplantation. We conclude that limiting the daily TNC dose improved the safety of this procedure without compromising engraftment or increasing the costs of the procedure.

INTRODUCTION

High dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) remains a common treatment approach in multiple myeloma and lymphoma. Peripheral blood progenitor cells are used most commonly as a graft source for autologous transplants. When a patient undergoes ASCT, CD34+ stem cells are mobilized into the peripheral blood, harvested by apheresis and cryopreserved, to be thawed and reinfused after administration of high dose ablative chemotherapy with or without radiotherapy. Infusion of cryopreserved autologous stem cell products has been associated with adverse reactions. These range from mild events like nausea/vomiting, hypotension or hypertension, abdominal cramps, diarrhea, flushing and chills to severe life-threatening events like cardiac arrhythmia, encephalopathy, acute renal failure and respiratory depression(1–22). These reactions have been attributed to the cryoprotectant, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)(3, 7, 14, 15), red cell hemolysate(19–21), bacterial contamination of product(12, 22), high numbers of infused total nucleated cells (TNCs) and granulocytes(8, 16–18), or to idiosyncratic reactions.

Severe infusion-related adverse events (SAEs) occurred in three patients receiving cryopreserved peripheral blood stem cell (PBSC) products for ASCT between August 2005 and October 2007 in our program. Investigation of these cases suggested a possible causal association with high TNC and/or granulocyte content of the cryopreserved PBSC products, thus our institutional experience with infusion-related AEs was reviewed and a policy change was implemented in December 2007 to establish infusion limits. The new policy limited the daily cryopreserved PBSC product cell dose to ≤1.63 × 109 TNC/kg/day (in addition to the standard 10mL/kg/day total volume restriction to limit the amount of DMSO) in an effort to avoid/reduce the severity of infusion-related SAEs. The purpose of the current study was to assess the impact of this institutional policy change on cryopreserved PBSC product infusion schedules, neutrophil and platelet engraftment and infusion-related safety outcomes and costs of the transplant.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Retrospective analysis of infusion-related SAEs and institutional policy change

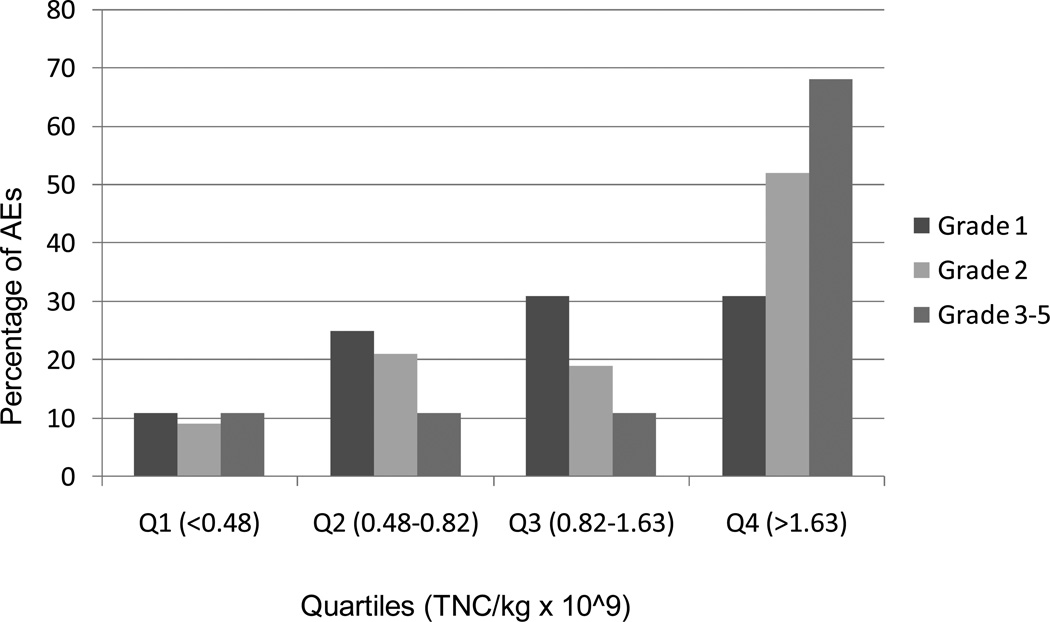

Three patients undergoing ASCT in 2007 developed infusion-related SAEs during or shortly after receiving thawed autologous cryopreserved PBSC product for multiple myeloma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma and Hodgkin lymphoma (Table 1). The thawed, unmanipulated PBSC products were infused after intravenous pre-hydration and administration of pre-medication with diphenhydramine and hydrocortisone, per institutional guidelines. Because these SAEs were temporally related to cryopreserved product infusions and did not appear to be causally associated with excessive DMSO exposure, anaphylaxis, haemolysis, concurrent infection or other direct cause, a quality assurance investigation was carried out to determine whether infusion-related SAEs might be associated with a high cellular content in the product, as had been recently reported by others(6, 8, 16, 17). For this quality investigation, infusion-related AEs were those that occurred within 4 hours post-infusion, and were reported on the Cellular Therapy Laboratory (CTL) Infusion Monitoring Form. The CTCAEv3.0 was used to grade acute conditions temporally associated with the infusions and distinguished grades 1 through 5, with grade 1, mild; grade 2, moderate; grade 3, severe; grade 4, life-threatening/ disabling; grade 5, death due to the AE(23). The association of distribution of the grades of the AEs with the total infused volume of cryopreserved PBSC product per kg recipient weight, the cumulative pre-freeze TNC content of all product bags and the cumulative TNC/kg was evaluated. The pre-freeze granulocyte content of PBSC products are not routinely quantified; however, analyses of a subset of autologous PBSC products revealed that the granulocyte content typically ranged from 40 – 70% of the TNC content, which is consistent with other centers using similar apheresis instruments and methodologies (24). A total of 411 patients who received PBSC cryoproduct infusions for ASCT from 1/3/2006–10/31/2007 were reviewed. Median and quartile analyses identified the pre-freeze TNC/kg dose as the strongest predictor of SAEs, with 67% of SAEs (grade 3 or higher; Figure 1) occurring in the highest quartile of patients who received ≥ 1.63 × 109 TNC/kg/day. Although product DMSO exposure (up to a maximum of 1 gm/kg/day or 10 mL/kg/day of product frozen in 10% DMSO, per institutional guidelines) also increased with greater numbers of PBSC product bags and TNCs infused, this parameter was not as strongly predictive of infusion-related SAEs as the TNC/kg (data not shown). Based on this quality assessment review, our SAE cases and the recent published reports of infusion-related AEs being independently associated with high TNC and granulocyte exposure, an institutional policy change was adopted to split infusions to deliver ≤ 1.63 × 109 TNC/kg/day. This policy change was implemented on 12/4/2007.

Table 1.

Index Cases with severe infusion-related adverse events (SAEs)

| Patient | History | SAE | Volume & Number of bags |

CD34+ cells/kg* |

TNC/kg* | Granulocytes/kg (% TNC)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 48/F; plasma cell leukemia; multiple infections; 2nd HCT | Rapid multiorgan failure; death 30 hrs after infusion | 466 mL 8 bags | 5.17×106 | 3.05×109 | 2.29×109 (65.4%) |

| II | 59/M; recurrent lymphoma; cardiovascular disease (2-day PBSC infusion) | 2nd day of infusion¶: Myocardial infarction & death | (2nd day product) 550 mL 10 bags | (2nd day product) 1.3×106 | 3.75×109 | 2.03×109 (54.13%) |

| III | 60/M; refractory Hodgkin lymphoma; cardiovascular disease | Acute renal failure; hemodialysis | 766 mL€ 12 bags | 5.57×106 | 6.14×109 | 4.64×109(75.57%) |

All product parameters are on pre-freeze product

Received 596 ml of PBSC cryoproduct on the 1st day

Did not exceed 10 ml/kg DMSO limit

Figure 1.

Distribution of adverse events according to grades in quartiles based on TNC/kg. Each of the grades (1, 2, 3–5) sums to 100% over the four quartiles (Q1+Q2+Q3+Q4)

Patients and study design to assess the impact of the policy change

A retrospective cohort study was undertaken to assess the impact of the policy change to limit the daily TNC/kg dose of cryopreserved PBSC products for ASCT patients on infusion-related safety, engraftment and costs. The study was designed to compare outcomes in a cohort of patients undergoing infusion of cryopreserved PBSC products for ASCTs from 5/20/2006 to 12/04/2007 (pre-policy change) to a cohort of ASCTs from 12/05/07 to 12/31/2009 (post-policy change). This retrospective cohort study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

Seven hundred and sixty seven patients were included in the study. These patients underwent a total of 844 ASCTs at 4 different centers including the University of Washington Medical Center (UWMC), Seattle Cancer Care Alliance (SCCA), Seattle Children’s Hospital and Veteran’s Administration Puget Sound Health Care System. Patients who received multiple days of PBSC cryoproduct infusions because of protocol requirement, rather than due to DMSO content or total number of infused TNC/kg, were excluded from the study. All patients received thawed PBSC products that were not diluted, washed or otherwise manipulated. Intravenous pre-hydration and pre-medications were routinely given. Infusion monitoring forms recorded either no infusion-related AEs during 4 hours post-infusion or AEs associated with specific signs and/or symptoms. Nursing and treatment interventions were also recorded. For CTL quality assurance purposes, additional clinical information was routinely obtained to formally investigate AEs of grade 3 or greater.

PBSC collection and product parameters

All patients had undergone collection of mobilized PBSCs by the SCCA Apheresis Unit. Mononuclear cell apheresis was performed on all patients using the COBE Spectra instrument (CaridianBCT, Lakewood, CO) with the white blood cell (WBC) kit and manual V4.7 program, processing 3- to 6-times total blood volume, as previously described (25). Apheresis collections commenced when the blood CD34+ count achieved at least 5 – 10 × 106/L or the WBC count had recovered to 1 × 109/L following mobilization with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) and preceding chemotherapy or on day 4 or 5 when mobilized from steady-state with G-CSF alone. A few patients received plerixafor in addition to G-CSF for mobilization. Daily apheresis continued until ≥ 5 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg were collected for a single ASCT or at least 2.5 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg if the patient was difficult to mobilize. Prior to concentration and cryopreservation in 10% DMSO, the TNC content, viability and sterility of the PBSC products were routinely determined. As with the prior quality assurance investigation, the granulocyte contents of autologous PBSC products were not routinely quantified before cryopreservation. To confirm our preliminary observations of the range of PBSC product granulocyte content and to determine whether the product quality had changed over time, we accessed archival pre-freeze flow cytometry data on a random subset of products from both the pre- and post-policy change cohorts to enumerate granulocyte content in relation to TNC content.

Data collection

The CTL product records and infusion monitoring forms were reviewed to retrieve information about patient age and diagnosis, the location and date(s) of autologous cryopreserved PBSC product infusion, cumulative product volumes, number of bags infused, clinical infusion-related AEs with grades and additional information based on internal CTL quality investigations. The CTCAEv3.0 was used to grade acute conditions temporally associated with the infusions, as outlined above. For the purpose of the study, any AEs grade 3 and above were termed as SAEs. Product cumulative CD34+ cell counts, CD34+ cells/kg, cumulative product TNC counts and TNC/kg, neutrophil and platelet engraftment data were extracted from the electronic medical records as well as an institutional database. Costs were retrieved from the accounting database for the SCCA and UWMC patients for whom charges and department ratio of costs to charges (RCCs) for the first 3 months after the transplant were available.

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as median (range) for continuous variables and counts (percentages) for categorical variables. For purposes of display and analysis, each ASCT is counted as a separate data point, although some patients experienced more than one ASCT. Statistical comparison between pre-policy and post-policy change was performed using Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continous variables and chi-squared test for categorical variables. All p-values are two-sided.

RESULTS

Study Population

Study cohorts included 288 patients undergoing 325 ASCTs (261 with 1 ASCT, 21 with 2, 2 with 3, and 4 with 4) before the policy change and 479 patients undergoing 519 ASCTs (446 with 1 ASCT, 28 with 2, 3 with 3, and 2 with 4) after the policy change.

Table 2 compares the patient and transplant characteristics in the overall pre- and post-policy cohorts and in the subset of patients with cryopreserved PBSC products that contained > 1.63 × 109 TNC/kg. There were no significant differences in the age, gender, distribution of diagnosis and product TNC and CD34+ cell counts between the high TNC cohorts pre and post policy change. The median volume/kg/day was lower for post-policy group as compared to pre-policy both for overall cohort (p=0.003) and the high TNC subgroup (p<0.001). However the median total volume per ASCT was similar in pre and policy cohorts both for overall and high TNC subgroups. The frequencies of patients with cryopreserved products containing a cumulative TNC content of > 1.63 × 109/kg were similar in the pre-policy and post-policy cohorts (25.2% and 24.1%, respectively). The quartile distributions of cryopreserved product granulocyte contents were no different for PBSC products collected and stored from patients in the pre-policy and post-policy cohorts (Table 3). Together, these parameters indicated that apheresis collection quality and the cellular composition of the cryopreserved PBSC products had not changed appreciably over the course of the study period. There were no significant changes in the practices for stem cell collection or processing, clinical policies for reinfusion of cryopreserved PBSCs and for tracking of AEs over the study period.

Table 2.

Patient and Transplant Characteristics. (A) All autologous stem cell transplants (ASCTs) during the study period. (B) ASCTs with cryopreserved PBSC products containing a cumulative TNC dose of > 1.63 × 109/kg.

| (A) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-policy change (n=325) |

Post-policy change (n=519) |

P-value | |

| Age at ASCT, years, median (range) | 53 (1–78) | 55 (0–74) | 0.02 |

| Male, n (%) | 230 (71) | 342 (66) | 0.14 |

| Weight, median (range) | 81.1 (10.6–165.0) | 81.8 (7.5–158.8) | 0.55 |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | |||

| Multiple myeloma | 118 (36) | 225 (43) | |

| Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma/CLL | 119 (37) | 175 (34) | |

| Other Diagnoses | 88 (27) | 119 (23) | 0.12 |

| CD34 × 106/kg, median (range) | 6.29 (0.22–59.25) | 6.35 (0.81–87.04) | 0.49 |

| TNC × 109/kg, median (range) | 0.82 (0.09–8.65) | 0.92 (0.05–7.26) | 0.43 |

| Volume (mL)/kg/day, median (range) | 1.75 (0.26–9.27) | 1.68 (0.30–7.61) | 0.003 |

| Volume (mL) /kg total, median (range) | 1.80 (0.26–16.78) | 1.80 (0.30–10.49) | 0.88 |

| (B) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-policy change (n=82) |

Post-policy change (n=125) |

P-value | |

| Age at ASCT, years, median (range) | 57 (2–75) | 60 (2–73) | 0.32 |

| Male, n (%) | 56 (68) | 73 (58) | 0.15 |

| Weight, median (range) | 78.9 (15.1–137.8) | 72.3 (14.8–121.7) | 0.69 |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | |||

| Multiple myeloma | 20 (24) | 45 (36) | |

| Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma/CLL | 44 (54) | 61 (49) | |

| Other Diagnoses | 18 (22) | 19 (15) | 0.16 |

| CD34 × 106/kg, median (range) | 4.98 (1.11–25.8) | 5.00 (0.81–53.6) | 0.64 |

| TNC × 109/kg, median (range) | 2.66 (1.64–8.64) | 2.53 (1.63–7.26) | 0.90 |

| Volume (mL)/kg/day, median (range) | 4.54 (1.13–9.27) | 2.37 (1.00–7.61) | <0.0001 |

| Volume (mL)/kg total, median (range) | 5.29 (2.26–16.78) | 5.11 (2.00–10.49) | 0.81 |

Table 3.

Pre and post policy change granulocye contents of pre-freeze apheresis products

| TNC/kg Quartiles | Pre-policy change | Post-policy change | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Granulocytes/kg (×109) Median (range) |

N | Granulocytes/kg (×109) Median (range) |

||

| Q1 (TNC/kg < 0.49) | 20 | 0.22 (0.04–0.33) | 16 | 0.25 (0.07–0.41) | 0.31 |

| Q2 (TNC/kg 0.49–0.82) | 18 | 0.38 (0.18–0.54) | 19 | 0.34 (0.03–0.56) | 0.83 |

| Q3 (TNC/kg 0.83–1.63) | 19 | 0.62 (0.38–1.00) | 19 | 0.58 (0.18–0.97) | 0.59 |

| Q4 (TNC/kg >1.63) | 18 | 1.23 (0.66–5.54) | 19 | 1.45 (0.60–3.23) | 0.46 |

Number of infusion days

The median number of infusion days was 1 vs. 1 for all patients, and 1 vs. 2 for those with > 1.63 × 109 TNC/kg product cell doses (p<0.0001). The percentage of patients requiring 1, 2 or >2 days of infusion before the policy change was 93.6%, 5.8% and 0.6%, respectively, whereas it was 76.5%, 16.0% and 7.5% after the policy change (p<0.0001).

Infusion-related AEs and time to engraftment

There was no difference in the incidence of all grades of infusion-related AEs in the post-policy cohort, but the number of ASCTs with grade 3–5 AEs was significantly reduced after the policy change. This was true among all autologous transplants [4 % pre-policy change vs. 0.6 % post-policy change, respectively, p<0.0004] and among the subset of ASCTs with cryopreserved PBSC products containing > 1.63 × 109 TNC/kg [10% vs. 1%, p=0.002] (Table 4). Ten of the 125 ASCTs with products containing > 1.63 × 109 TNC/kg in the post-policy cohort received all of their cells on one day (Table 4B). The decision for a single-day infusion was made predominantly because the cumulative TNC content only minimally exceeded the 1.63 × 109/kg limit.

Table 4.

Clinical Outcomes. (A) All patients undergoing autologous transplantation during the study period. (B) Patients with cryopreserved PBSC products containing a cumulative TNC dose of > 1.63 × 109/kg.

| (A) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-policy change (n=325) |

Post-policy change (n=519) |

P-value | |

| > 1 infusion days, n (%) | 21 (6) | 122 (24) | <0.0001 |

| Infusion AEs (any grade), n (%) | 149 (46) | 256 (49) | 0.32 |

| Infusion AEs (grade 3–5), n (%) | 13 (4.0) | 3 (0.6) | 0.0004 |

| Days to neutrophil engraftment, median (range), [n evaluable]2 | 14 (8–41) [295] | 14 (8–31) [495] | 0.99 |

| Days to platelet engraftment, median (range), [n evaluable]2 | 12 (5–45) [273] | 12 (6–53) [454] | 0.82 |

| (B) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-policy change (n=82) |

Post-policy change (n=125) |

P-value | |

| > 1 infusion days, n (%) | 20 (24) | 115 (92)1 | <0.0001 |

| Infusion AEs (any grade), n (%) | 60 (73) | 90 (72) | 0.85 |

| Infusion AEs (grade 3–5), n (%) | 8 (10) | 1 (1) | 0.002 |

| Days to neutrophil engraftment, median (range), [n evaluable]2 | 14 (8–41) [76] | 14 (8–28) [121] | 0.12 |

| Days to platelet engraftment, median (range), [n evaluable]2 | 13 (7–43) [70] | 13 (6–43) [109] | 0.87 |

The few patients in this group who received one day of infusion generally had PBSC products that only minimally exceeded the 1.63 × 109 TNC/kg limit.

All patients could not be evaluated due to death or missing data due to loss to follow-up.

There were three SAEs in the post-policy change cohort. Two of those had received products containing ≤ 1.63. One of them was a patient with a known seizure disorder who developed a self-limited, partial complex seizure at the end of infusion and was subsequently found to have sub therapeutic blood levels of antiseizure medication. The second patient had transient chest pain that required brief hospitalization to rule out a myocardial infarction. No etiology was determined and the patient suffered no sequelae. The third event was in a pediatric patient, who received a product with >1.63 × 109 TNC/kg and ultimately suffered a grade 4 adverse event.

To determine whether the significant difference in post-policy SAE incidence was due to the difference in TNC/kg/day or DMSO volume per day, a logistic regression analysis was performed. Product volume was a significant predictor of infusion-related SAEs by itself (p<0.0001), but this parameter lost significance when adjusted for TNC/kg (p=0.54). By comparison, TNC/kg was a highly significant predictor for AEs in both univariate analysis (p<0.0001) and when adjusted for product volume (p<0.0001).

The policy change did not have any apparent detrimental impact on neutrophil or platelet engraftment. The median days to neutrophil engraftment were the same for the overall pre-policy and post-policy cohorts (14 vs. 14, p=0.99) and for ASCTs with cryopreserved products containing cumulative TNC doses of > 1.63 × 109/kg (14 vs. 14, p=0.12) (Table 4). Similarly, no differences were seen in the median days to platelet engraftment in either the overall cohorts (12 vs. 12, p=0.82) or among those who received TNC doses of > 1.63 × 109/kg (13 vs. 13, p=0.82) (Table 4). Times to neutrophil and platelet engraftment within subgroups of ASCTs for patients with multiple myeloma, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma/CLL or other diagnoses were not affected by the increased number of infusion days prompted by the policy change (Table 5). Engraftment times were also the same among ASCTs in disease-specific subgroups who received > 1.63 × 109 TNC/kg; however, more rigorous statistical analyses of the potential effects of multi-day infusions were precluded by small numbers (Table 5B and C).

Table 5.

Engraftment outcomes based on diagnosis. (A) All ASCTs during the study period. (B) ASCTs with cryopreserved PBSC products containing a cumulative TNC dose of > 1.63 × 109/kg. (C) ASCTs with cryopreserved PBSC products containing a cumulative TNC dose of > 1.63 × 109/kg with multi-day infusions

| (A) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-policy change All infusions |

Post-policy change All infusions |

P-value | |

| Median days to neutrophil engraftment (n evaluable) | |||

| Multiple Myeloma | 15 (117) | 15 (223) | 0.59 |

| Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma/CLL | 13 (118) | 13 (173) | 0.99 |

| Other diagnosis | 14 (60) | 12 (100) | 0.07 |

| Median days to platelet engraftment (n evaluable) | |||

| Multiple Myeloma | 11 (106) | 11 (199) | 0.62 |

| Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma/CLL | 12 (111) | 12 (158) | 0.36 |

| Other diagnosis | 13 (56) | 12 (97) | 0.21 |

| (B) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-policy change All infusions |

Post-policy change All infusions |

P-value | |

| Median days to neutrophil engraftment (n evaluable) | |||

| Multiple Myeloma | 14 (19) | 15 (44) | 0.39 |

| Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma/CLL | 14 (43) | 14 (60) | 0.40 |

| Other diagnosis | 13 (14) | 13 (17) | 0.60 |

| Median days to platelet engraftment (n evaluable) | |||

| Multiple Myeloma | 14 (17) | 12.5 (40) | 0.09 |

| Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma/CLL | 12 (41) | 13 (54) | 0.33 |

| Other diagnosis | 12.5 (12) | 14 (15) | 0.68 |

| (C) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-policy cohort Number of Infusions |

Post-policy cohort Number of Infusions |

|||||

| 1 | 2 | >2 | 1 | 2 | >2 | |

| Median days to neutrophil engraftment (n evaluable) | ||||||

| Multiple Myeloma | 14.5 (12) | 14 (7) | -- | 16 (1) | 15 (37) | 15 (6) |

| Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma/CLL | 14 (34) | 14 (7) | 14.5 (2) | 16.5 (2) | 14 (33) | 14 (25) |

| Other diagnosis | 14 (11) | 11 (3) | -- | 10 (5) | 12.5 (6) | 16.5 (6) |

| Median days to platelet engraftment (n evaluable) | ||||||

| Multiple Myeloma | 15 (12) | 12 (5) | -- | 20 (1) | 12 (34) | 15 (5) |

| Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma/CLL | 12 (34) | 14.5 (6) | 12 (1) | 11.5 (2) | 12 (31) | 13 (21) |

| Other diagnosis | 12.5 (10) | 16.5 (2) | -- | 12 (5) | 21 (5) | 14 (5) |

Cost analysis

There were no significant differences between inpatient and outpatient costs for the first 3 months after ASCT between the transplants in pre and post-policy cohorts (Table 6). The overall costs for ASCTs in the post-policy cohort with products containing > 1.63 × 109 TNC/kg and for whom infusions were given over multiple days were similar to overall costs for pre-policy ASCTs with high product TNC content and for whom infusions were usually completed in one day (Table 6B).

Table 6.

Comparison of costs for 3 months post autologous transplantation. (A) All ASCTs during the study period. (B) ASCTs with cryopreserved PBSC products containing a cumulative TNC dose of > 1.63 × 109/kg.

| (A) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-policy change | Post-policy change | P-value | |||

| N | Median cost* (range) | N | Median cost* (range) | ||

| Inpatient | 94 | 68.8 (8.7–223.7) | 170 | 65.4 (22.3–267.7) | 0.76 |

| Outpatient | 119 | 58.8 (21.0–330.8) | 207 | 58.5 (0.3–294.0) | 0.57 |

| (B) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-policy change | Post-policy change | P-value | |||

| N | Median cost* (range) | N | Median cost* (range) | ||

| Inpatient | 32 | 65.1 (8.7–223.7) | 47 | 69.2 (31.7–159.6) | 0.67 |

| Outpatient | 29 | 59.3 (30.3–147.4) | 46 | 68.3 (2.1–214.5) | 0.25 |

Cost in $1000’s

DISCUSSION

The overall incidence of all adverse events associated with autologous PBSC infusions reported in the literature ranges from 13.5 to 67.3%(4, 8, 16, 17). More severe infusion-related events occur in the range of 0.4%, as reported by Graves et al.(26). Multiple studies have shown persistence of these AEs even after depletion of DMSO and as such these complications have been attributed to the nucleated cell and/or granulocyte content of the cryopreserved apheresis product. In fact, Calmels et al. reported strong correlations not only between the occurrence but also severity of infusion-related AEs with a high pre-freeze product granulocyte content and low post-thaw CD45+ cell viability (16). Together, these observations suggest that granulocytes, both viable and dead cells, and cellular debris (membranes, granule contents, and cytokines) play a direct causal role in the pathobiology of infusion-related toxicities.

Investigators have suggested a variety of ways to address the issue of toxicity due to high granulocyte content of the cryopreserved PBSC product. At the time of collection, obtaining high quality apheresis products with minimal contamination by mature myeloid cells is desirable (4, 8, 16, 17). Poor mobilization of CD34+ progenitor cells is a major factor that can negatively affect the quality of the apheresis product. Difficulty mobilizing CD34+ cells has also been described as a poor prognostic factor in terms of predicting engraftment delay and worse event-free survival despite transplanting adequate CD34+ cell doses (27, 28). High peripheral blood WBC and granulocyte counts as seen with mobilization using only hematopoietic growth-factor (GF) stimulation are associated with decreased CD34+ cell collection efficiency and a higher rate of granulocyte contamination of the PBSC product(29, 30). Cooling et al. recently reported that chemotherapy and GF mobilization along with manual collection on the COBE Spectra instrument with the WBC kit improved CD34+ cell yield and decreased the granulocyte content and infusion reaction rates as compared to mobilization with GF only and use of AUTO-kits (24). This raises the consideration that different apheresis devices, collection parameters or flow rates may be employed to optimize CD34+ cell collection efficiency and reduce the amount of granulocytes in the final product in order to decrease cryopreserved PBSC product infusional toxicity. Plerixafor is a relatively new agent that is being increasingly used to improve CD34+ cell mobilization and collection in heavily pretreated patients who are poor mobilizers (31), (32, 33). These and other interventions that improve graft quality without the need for repeated apheresis procedures may help decrease infusion-related AEs due to cryopreserved product granulocyte contamination.

This study demonstrates that spreading out the infusions of cryopreserved PBSC products for ASCT over multiple days can significantly reduce the incidence of grade 3–5 infusion-related AEs without compromising the speed of hematopoietic recovery. The days to neutrophil and platelet engraftment were comparable in our pre-policy change and post-policy change cohorts, regardless of whether the cumulative PBSC product TNC content was above or below our safety threshold of 1.63 × 109 TNC/kg. Neutrophil and platelet engraftment times were similar for patients with myeloma, lymphoid malignancies or other diseases whether they required one day for product infusion or more than one day. Splitting the infusions over multiple days does impose increased workload for the cell therapy facility and the nursing staff. However, this did not translate into significantly increased costs to third-party payers among the overall post-policy change cohort or among the subset of patients with high product TNC content who were subject to multiple days of infusion. We believe that the increased safety from severe infusion-related adverse events ultimately compensates for the logistic challenges of multi-day infusions.

Our study does have some limitations. Although we assessed days to platelet and neutrophil engraftment, we did not specifically evaluate for any effects of limiting the daily TNC dose on immune reconstitution, infectious complications or days of hospitalization. While our decision to split the infusions was based on daily TNC dose, this also resulted in lowering the daily DMSO exposure, which might have accounted for the decrease in SAEs. However, 4% of patients in the pre-policy cohort suffered grade 3 – 5 AEs despite limiting the daily volume/kg of product to at or below the well accepted standard limit of 10 ml/kg to restrict the DMSO exposure.(21) To address this question further, we performed a multivariable analysis and found that, although volume was a significant predictor of infusion-related SAEs by itself (p<0.0001), after adjustment for TNC it lost all significance (p=0.54). In contrast, TNC was a highly significant predictor by itself and after adjustment for volume. Another limitation was that in examining costs, the estimates in the study represent costs of autologous stem cell transplants at our center and may not be representative, although they are in the range of overall costs as suggested by the National Bone Marrow Transplant LINK resource guide in the United States (http://www.nbmtlink.org/resources_support/rg/rg_costs.htm).

Due to a small number of patients receiving plerixafor, we could not assess its impact on the number of TNCs in the collection product or whether it might eliminate the need for multi-day infusions. We also acknowledge that the adverse effects of high TNC and granulocytes in the thawed apheresis product may be related to as yet undefined risk factors in patients with certain disease characteristics. It is possible that factors predisposing to poor mobilization and/or correlating with pre-transplant co-morbidity profiles, especially cardiovascular disease or infections might also predispose a patient to more severe infusion-related toxicity. Age, gender and patient diagnosis have been reported as predictors of AEs in other studies (4, 8, 17). Bojanic et al identified female gender and diagnosis of multiple myeloma in addition to granulocyte content as factors predicting infusion-related toxicity(4). The effect of age is not so clear as Milone et al reported increasing incidence of AEs with increasing age(8) whereas Cordoba et al found increased age to be protective against occurrence of AEs(17).

In conclusion, limiting the daily dose of infused TNC/kg in cryopreserved PBSC products for ASCT resulted in a significant reduction in grade 3 – 5 infusion-related SAEs. Although this practice translated into an increased frequency of multi-day infusions, the kinetics of post-transplant hematopoietic recovery and the overall costs of transplantation were not affected by this safety measure.

Our study sets the stage for continued evaluation of interventions and techniques at the time of collection to procure a high quality apheresis product that minimizes the chance of infusion-related complications and improves the safety and outcomes of autologous transplantation. Further research is needed to study efficacy and compare costs of these techniques and strategies. Future investigations should also attempt to identify patients who may be at highest risk for AEs, especially those with co-morbidities or poor mobilization, since they might benefit the most from a cost-effective alternative approach.

Acknowledgements of research support

Grant support: CA 15704, CA 18029, DK56465.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosures: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alessandrino P, Bernasconi P, Caldera D, et al. Adverse events occurring during bone marrow or peripheral blood progenitor cell infusion: analysis of 126 cases. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1999;23:533–537. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauwens D, Hantson P, Laterre PF, et al. Recurrent seizure and sustained encephalopathy associated with dimethylsulfoxide-preserved stem cell infusion. Leuk Lymphoma. 2005;46:1671–1674. doi: 10.1080/10428190500235611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benekli M, Anderson B, Wentling D, Bernstein S, Czuczman M, McCarthy P. Severe respiratory depression after dimethylsulphoxide-containing autologous stem cell infusion in a patient with AL amyloidosis. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2000;25:1299–1301. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bojanic I, Cepulic BG, Mazic S, Batinic D, Nemet D, Labar B. Toxicity related to autologous peripheral blood haematopoietic progenitor cell infusion is associated with number of granulocytes in graft, gender and diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Vox Sang. 2008;95:70–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2008.01060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis JM, Rowley SD, Braine HG, Piantadosi S, Santos GW. Clinical toxicity of cryopreserved bone marrow graft infusion. Blood. 1990;75:781–786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fois E, Desmartin M, Benhamida S, et al. Recovery, viability and clinical toxicity of thawed and washed haematopoietic progenitor cells: analysis of 952 autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantations. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;40:831–835. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoyt R, Szer J, Grigg A. Neurological events associated with the infusion of cryopreserved bone marrow and/or peripheral blood progenitor cells. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2000;25:1285–1287. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milone G, Mercurio S, Strano A, et al. Adverse events after infusions of cryopreserved hematopoietic stem cells depend on non-mononuclear cells in the infused suspension and patient age. Cytotherapy. 2007;9:348–355. doi: 10.1080/14653240701326756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rapoport AP, Rowe JM, Packman CH, Ginsberg SJ. Cardiac arrest after autologous marrow infusion. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1991;7:401–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rowley S, MacLeod B, Heimfeld S, Holmberg L, Bensinger W. Severe central nervous system toxicity associated with the infusion of cryopreserved PBSC components. Cytotherapy. 1999;1:311–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith DM, Weisenburger DD, Bierman P, Kessinger A, Vaughan WP, Armitage JO. Acute renal failure associated with autologous bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1987;2:195–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stroncek DF, Fautsch SK, Lasky LC, Hurd DD, Ramsay NK, McCullough J. Adverse reactions in patients transfused with cryopreserved marrow. Transfusion. 1991;31:521–526. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1991.31691306250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Windrum P, Morris TC. Severe neurotoxicity because of dimethyl sulphoxide following peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2003;31:315. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zambelli A, Poggi G, Da Prada G, et al. Clinical toxicity of cryopreserved circulating progenitor cells infusion. Anticancer Res. 1998;18:4705–4708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zenhausern R, Tobler A, Leoncini L, Hess OM, Ferrari P. Fatal cardiac arrhythmia after infusion of dimethyl sulfoxide-cryopreserved hematopoietic stem cells in a patient with severe primary cardiac amyloidosis and end-stage renal failure. Ann Hematol. 2000;79:523–526. doi: 10.1007/s002770000186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calmels B, Lemarie C, Esterni B, et al. Occurrence and severity of adverse events after autologous hematopoietic progenitor cell infusion are related to the amount of granulocytes in the apheresis product. Transfusion. 2007;47:1268–1275. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cordoba R, Arrieta R, Kerguelen A, Hernandez-Navarro F. The occurrence of adverse events during the infusion of autologous peripheral blood stem cells is related to the number of granulocytes in the leukapheresis product. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;40:1063–1067. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donmez A, Tombuloglu M, Gungor A, Soyer N, Saydam G, Cagirgan S. Clinical side effects during peripheral blood progenitor cell infusion. Transfus Apher Sci. 2007;36:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2006.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oziel-Taieb S, Faucher-Barbey C, Chabannon C, et al. Early and fatal immune haemolysis after so-called 'minor' ABO-incompatible peripheral blood stem cell allotransplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997;19:1155–1156. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1700794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salmon JP, Michaux S, Hermanne JP, et al. Delayed massive immune hemolysis mediated by minor ABO incompatibility after allogeneic peripheral blood progenitor cell transplantation. Transfusion. 1999;39:824–827. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1999.39080824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sauer-Heilborn A, Kadidlo D, McCullough J. Patient care during infusion of hematopoietic progenitor cells. Transfusion. 2004;44:907–916. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2004.03230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwella N, Zimmermann R, Heuft HG, et al. Microbiologic contamination of peripheral blood stem cell autografts. Vox Sang. 1994;67:32–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.1994.tb05034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Program. CTE. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v3.0. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cooling L, Hoffmann S, Herrst M, Muck C, Armelagos H, Davenport R. A prospective randomized trial of two popular mononuclear cell collection sets for autologous peripheral blood stem cell collection in multiple myeloma. Transfusion. 2010;50:100–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rowley SD, Prather K, Bui KT, Appel M, Felt T, Bensinger WI. Collection of peripheral blood progenitor cells with an automated leukapheresis system. Transfusion. 1999;39:1200–1206. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1999.39111200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Graves VDC, Abonour R, McCarthy LJ. How to ensure safe and well-tolerated stem cell infusions. Transfusion. 1998;38 (suppl):30S. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pavone V, Gaudio F, Console G, et al. Poor mobilization is an independent prognostic factor in patients with malignant lymphomas treated by peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;37:719–724. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tomblyn M, Burns LJ, Blazar B, et al. Difficult stem cell mobilization despite adequate CD34+ cell dose predicts shortened progression free and overall survival after autologous HSCT for lymphoma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;40:111–118. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burgstaler JEPA, Winter JL. Effects of high whole blood flow rates and high peripheral WBC on CD34+ yield and cross-cellular contamination[abstract] Cytotherapy. 2003;5:446. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gidron A, Verma A, Doyle M, et al. Can the stem cell mobilization technique influence CD34+ cell collection efficiency of leukapheresis procedures in patients with hematologic malignancies? Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;35:243–246. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duarte RF, Shaw BE, Marin P, et al. Plerixafor plus granulocyte CSF can mobilize hematopoietic stem cells from multiple myeloma and lymphoma patients failing previous mobilization attempts: EU compassionate use data. Bone Marrow Transplant. 46:52–58. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2010.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dugan MJ, Maziarz RT, Bensinger WI, et al. Safety and preliminary efficacy of plerixafor (Mozobil) in combination with chemotherapy and G-CSF: an open-label, multicenter, exploratory trial in patients with multiple myeloma and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma undergoing stem cell mobilization. Bone Marrow Transplant. 45:39–47. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stiff P, Micallef I, McCarthy P, et al. Treatment with plerixafor in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and multiple myeloma patients to increase the number of peripheral blood stem cells when given a mobilizing regimen of G-CSF: implications for the heavily pretreated patient. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15:249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]