Abstract

Arenaviruses include several important human pathogens, and there are very limited options of preventive or therapeutic interventions to combat these viruses. An off-label use of the purine nucleoside analogue ribavirin (1-β-d-ribofuranosyl-1-H-1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxamide) is the only antiviral treatment currently available for arenavirus infections. However, the ribavirin antiviral mechanism action against arenaviruses remains unknown. Here we document that ribavirin is mutagenic for the prototypic arenavirus lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) in cell culture. The mutagenic activity of ribavirin on LCMV was observed under single- and multiple-passage regimes and could not be accounted for by a decrease of the intracellular GTP pool promoted by ribavirin-mediated inhibition of inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH). Our findings suggest that the antiviral activity of ribavirin on arenaviruses might be exerted, at least partially, by lethal mutagenesis. Implications for antiarenavirus therapy are discussed.

INTRODUCTION

Arenaviruses are a group of enveloped viruses with a bisegmented negative-strand RNA genome. Both the small (S) and large (L) genome RNAs use an ambisense coding strategy to direct the synthesis of two proteins; the S segment encodes the virus nucleoprotein (NP) and glycoprotein (GPC), whereas the L segment encodes the virus polymerase (L) and matrix (Z) proteins. Arenaviruses cause persistent infection in rodents with a worldwide distribution (11, 13, 72, 72a). Several arenaviruses can infect humans, which may result in severe clinical symptoms, including hemorrhagic fever (HF) disease in areas of South America (Junin virus in Argentina, Machupo virus in Bolivia, and Sabia virus in Brazil) and West Africa (Lassa and Lujo viruses). HF arenaviruses are a great public health concern in the regions where these viruses are endemic. In addition, arenaviruses also pose a biodefense threat, and six arenaviruses are category A agents (12, 13, 27, 72, 72a). On the other hand, the prototypic arenavirus lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) provides investigators with a superb model system for the investigation of virus-host interactions and associated disease (reviewed in references 72 and 72a). Moreover, mounting evidence indicates that LCMV is a neglected human pathogen of clinical significance (9, 31, 45, 73).

Public health concerns about arenavirus infections of humans are further exacerbated because of the lack of licensed vaccines and current therapy being limited to an off-label use of the purine nucleoside analogue ribavirin (1-β-d-ribofuranosyl-1-H-1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxamide) (1, 13, 36, 55, 66, 68). Ribavirin has been licensed for human use as an antiviral agent for 4 decades (86, 89). It is administered either alone or in combination with other antiviral agents, and it is currently employed to treat chronic hepatitis C in combination with pegylated alpha interferon (IFN-α) and respiratory syncytial virus infections in infants and is used off-label to treat some other respiratory infections (21–23, 44, 66, 67). The antiviral activity of ribavirin is mediated by several mechanisms, including inhibition of the cellular inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH) and viral mutagenesis (reviewed in reference 37). The mutagenic activity of ribavirin was discovered with poliovirus (18) and then documented with several additional RNA viruses (37). Ribavirin triphosphate (RTP) is a substrate for the RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RdRps) of some RNA viruses, and the incorporation of RTP in place of ATP or GTP results in mutagenic activity during viral RNA elongation (3, 5, 7, 17, 18, 62, 87).

LCMV exhibits the high mutation rates and quasispecies dynamics typical of RNA viruses, and this confers this pathogen great adaptability to different environments (26, 28, 85). Because of the need to explore new strategies for the control of arenavirus-associated disease, we took LCMV as a model system to investigate lethal mutagenesis or virus extinction through an increase in the mutation rate (for reviews, see references 6, 24, 32, and 38). The analogue 5-fluorouracil (FU) is an effective mutagenic agent for LCMV and can lead to viral extinction through a decrease in the specific infectivity of the mutagenized virus (39–41). Ribavirin has also been used to extinguish RNA viruses by lethal mutagenesis (38). However, in studies in which ribavirin was administered to arenavirus-infected cells or animals, the drug acted as an inhibitor of viral replication, but no mutagenic activity was reported (29, 43, 49, 51, 60, 81, 83, 88). In our previous studies on lethal mutagenesis, we documented a higher efficacy of a mutagen-inhibitor combination treatment over administration of a mutagen alone (74, 92). In an exploration of protocols to achieve extinction of foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) using ribavirin as a mutagenic agent and guanidine hydrochloride as an inhibitor of FMDV replication, we observed an advantage of a sequential inhibitor-mutagen treatment over the corresponding combination treatment (77). The scope of the advantage of the sequential treatment is currently under investigation. Since the advantage of the sequential treatment was dependent on one of the drugs being a mutagenic agent, we reexamined the inhibitory and potential mutagenic activity of ribavirin on LCMV. Here we provide evidence that besides its well-documented inhibitory activity on arenavirus multiplication, ribavirin also exerts mutagenic activity when present at subinhibitory concentrations (that is, concentrations that result in lower but detectable progeny production) during virus replication in cultured cells. The inhibitory and mutagenic activities of ribavirin were largely reversed by supplying cells with excess guanosine, suggesting that both activities may operate in competition with intracellular GTP. However, the mutagenic activity of ribavirin on LCMV cannot be attributed to a depletion of intracellular GTP levels as a result of inhibition of IMPDH, because treatment with mycophenolic acid (MPA), an inhibitor of IMPDH (33), did not exert any detectable mutagenic activity on LCMV. Our findings raise the possibility that lethal mutagenesis promoted by ribavirin-induced mutagenesis might contribute to the antiviral activity of ribavirin against LCMV and arenaviruses in general.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, virus, and drugs.

Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) strain Armstrong (Arm) 53b is a clone from LCMV Arm CA that was plaque purified three times and passaged four times in BHK-21 cells. This virus was used for all cell culture infections described in the present study. Procedures to grow BHK-21 and Vero cells and to infect cells with LCMV have been previously described (39–41, 64). Briefly, for single-step infections, BHK-21 cells were infected with LCMV at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 PFU/cell in the presence or absence of ribavirin, mycophenolic acid (MPA), or guanosine or combinations of these drugs at the concentrations indicated for each experiment. Progeny virus was collected at 48 h postinfection (p.i.) from the cell culture medium. For serial passages, infections of BHK-21 cells were carried out at an MOI of 0.01 PFU/cell in the presence or absence of drugs as indicated for each experiment. In each passage, the cells were infected with the progeny virus from the preceding infection and collected at 48 h postinfection. For LCMV infections in the presence of ribavirin, BHK-21 cells were preincubated with the desired amount of ribavirin (Sigma) (0, 10, 20, or 100 μM) for 7 h, and the same ribavirin concentration was maintained throughout the infection. The toxicity of ribavirin for BHK-21 cells under the culture conditions used in the present study has been previously reported (3, 77). BHK-21 cells maintained at least 90% viability after 48 h of treatment with 100 μM ribavirin compared to control BHK-21 cells maintained in parallel in the absence of the drug. For LCMV infections in the presence of 0, 5, and 30 μM MPA, no toxicity for the cells was detected (100% survival after 48 h in 30 μM MPA). Treatment of BHK-21 cells with guanosine (100 μM), which did not result in detectable toxicity for the cells, was carried out as previously described (5). LCMV was titrated by plaque assay on Vero cell monolayers (4). Mock-infected BHK-21 and Vero cells were maintained in parallel, and the corresponding cell culture supernatants were titrated to control possible viral contamination. No infectivity was detected in the mock-infected cultures at any time.

RNA extraction, RT-PCR amplification, and LCMV RNA quantification.

RNA was extracted from the supernatants of LCMV-infected cultures using Trizol (Invitrogen), following the manufacturer's instructions. LCMV RNA was amplified by reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) using RT transcriptor (Roche) and Pfu DNA polymerase (Promega) and the following pair of primers, primers L3654F (F stands for forward) (5′-AGTTTAAGAACCCTTCCCGC-3′; residues 3654 to 4268) and L4260R (R stands for reverse) (5′-CGAGACACCTTGGGAGTTGTGC-3′; residues 4239 to 4260). Nucleotide positions are given in the viral (genomic) sense and refer to the consensus genomic sequence determined previously for the L segment (GenBank accession number AY847351-L) (39). To ensure that in the RT-PCR amplification, excess LCMV RNA template was present for quasispecies analysis, 1:10 and 1:100 dilutions of the initial template preparations were amplified in parallel. Only preparations that yielded a positive amplification band at the two dilutions were subjected to molecular cloning and sequencing of individual clones (5). The amplified cDNAs were either purified with a Wizard PCR purification kit (Promega) or subjected to agarose (Pronadisa) gel electrophoresis; the cDNA band was extracted from the gel using a QIAEX II gel extraction kit (Qiagen). Purified DNA was sequenced by Macrogen, Inc., to obtain the consensus sequence of the corresponding population.

Genomic large (L) RNA was quantified by Light Cycler DNA Master SYBR green I kit (Roche), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The polymerase-coding region was amplified with primers L4183F (5′-ATCGAGGCCACACTGATCTT-3′; residues 4183 to 4202) and L4260R (5′-CGAGACACCTTGGAGTTGTGC-3′; residues 4239 to 4260). An LCMV RNA fragment spanning nucleotides 3662 to 4268 was used as the standard. This was obtained as a runoff transcript from a molecular DNA clone of the polymerase-coding region in the genomic sense, cloned into pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega). The denaturation curve of the amplified DNAs was determined to monitor the specificity of the reaction. Negative controls (without template RNA) were run in parallel with each amplification reaction mixture. Each value is the average of at least three determinations. The specific infectivity of LCMV was calculated by dividing the number of progeny infectivity (PFU) by the amount of LCMV RNA in the same volume of culture medium.

Molecular cloning and calculation of mutant spectrum complexity.

Molecular clones were prepared from cDNA (the band corresponding to the RT-PCR amplification obtained with undiluted template) using primers L3654F and L4260R (described above in “RNA extraction, RT-PCR amplification, and LCMV RNA quantification”). cDNA was ligated to the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega) and transformed into Escherichia coli DH5α. cDNA from individual positive E. coli colonies was amplified with Templiphi (GE Healthcare) and sequenced (Macrogen, Inc.).

The average mutation frequency among components of the mutant spectrum of an LCMV population was calculated by dividing the number of different mutations found by the total number of nucleotides sequenced. The Shannon entropy (S) (which measures the proportion of different sequences in the region analyzed) was calculated using the formula S = −[∑i (pi × ln pi)]/ln N where pi is the proportion of each sequence in the mutant spectrum and N is the total number of sequences compared (94). An S value of 0 means that all sequences are identical, while a value of 1 means that the sequences are different from each other. Statistical significance values were calculated using Prism software program version 5.0 or higher. The mutation frequency calculated for LCMV passaged in the absence of ribavirin was at least 2.8-fold larger than can be attributed to the error incorporation during the RT-PCR procedure used (82).

RESULTS

Assessment of the inhibitory and mutagenic activity of ribavirin during LCMV replication in cultured cells.

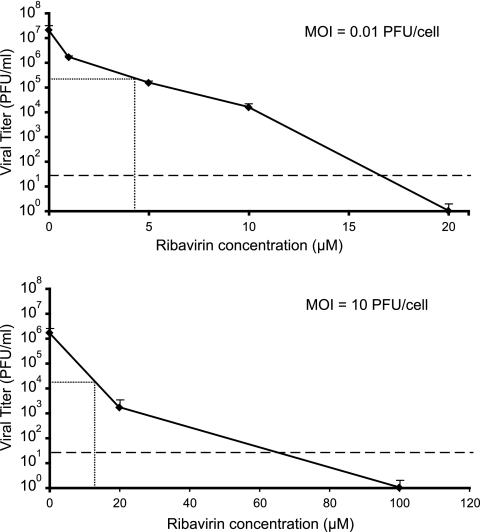

We first compared the inhibitory effect of ribavirin on LCMV multiplication in BHK-21 cells following infection at a low MOI and a high MOI (Fig. 1). The concentrations of ribavirin that produced a decrease of 99% in the yield of infectious progeny (99% inhibitory concentrations [IC99]) were 4.28 ± 0.24 μM for the infections carried out with an MOI of 0.01 PFU/cell and 12.83 ± 0.61 μM for the infections carried out with an MOI of 10 PFU/cell. Thus, the inhibitory effect of ribavirin on LCMV was more pronounced in infections carried out at a low MOI.

Fig. 1.

Inhibition of LCMV replication by ribavirin. BHK-21 cells were infected with LCMV Armstrong (Arm) 53b at an MOI of either 0.01 PFU/cell or 10 PFU/cell. Viral titers were determined at 48 h postinfection (p.i.) in triplicate, and standard deviations (error bars) are given. The horizontal and vertical lines indicate the viral titer and ribavirin concentration that yield the IC99 values (concentration of ribavirin that produces a 99% inhibition of LCMV infectious progeny production), given in the text as the average of triplicate determinations. The broken line indicates the limit of detection of LCMV infectivity. Note the different scale of the abscissa in the two plots. Procedures for LCMV infection in the presence or absence of ribavirin and for the determination of infectivity by plaque assays are detailed in Materials and Methods.

Ribavirin has been recognized as a mutagen for several RNA viruses (reviewed in reference 37). To investigate whether ribavirin could exert a dual inhibitory and mutagenic activity during LCMV replication, single-step infections were carried out at an MOI of 10 PFU/cell in the presence and absence of 20 μM or 100 μM ribavirin. The progeny infectivity, progeny RNA, mutant spectrum complexity, and types of mutations in the progeny populations were analyzed. The results (Table 1) confirm a strong inhibitory activity of ribavirin, with at least a 106-fold reduction of virus titer and 102-fold reduction of viral RNA levels in the presence of 100 μM ribavirin. It must be noted that the specific infectivity of progeny LCMV decreased 28.5-fold in the infection carried out in the presence of 20 μM ribavirin and at least 2,170-fold in the presence of 100 μM ribavirin (considering the limit of detection of infectivity [Table 1]). The significant decrease of specific infectivity may be relevant to the mechanism of inhibition of LCMV replication by ribavirin (see Discussion). The mutation frequency among components of the LCMV population passaged in the presence of 20 μM ribavirin was significantly higher (2.3-fold; P = 0.0385 by χ2 test) than in the population passaged in the absence of ribavirin. In contrast, no increase in mutation frequency was detected in the mutant spectrum of LCMV replicated in the presence of 100 μM ribavirin compared to LCMV replicated in the absence of ribavirin. The difference of population complexity was also reflected in the Shannon entropy (Table 1). Furthermore, examination of the mutation types shows that the infection in the presence of 20 μM ribavirin, but not in the presence of 100 μM ribavirin, led to a specific increase of G→A and C→U transitions (P < 0.05 by χ2 test) (Table 1). G→A and C→U are the types of mutations previously associated with ribavirin mutagenesis (3, 5, 18). In the population passaged in the absence of ribavirin, A→G and U→C transitions were more frequent than G→A and C→U transitions, and the same bias was present in the progeny of the infection carried out in the presence of 100 μM ribavirin (Table 1). In all cases, transitions were 3- to 5-fold more frequent than transversions. The results strongly suggest that ribavirin can exert a dual mutagenic and inhibitory activity on LCMV.

Table 1.

Quasispecies analysis of LCMV populations produced in the presence or absence of ribavirin and/or guanosinea

| Ribavirin concn (μM) | Guanosine concn (μM) | Progeny infectivity (PFU/ml)b | Progeny RNA (mol/ml)c | Specific infectivity (PFU/mol of RNA)d | Mutation frequencye | Shannon entropyf | No. of nucleotides sequencedg | Mutation types |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transition |

Transversionh |

|||||||||||||||||

| A→G | G→A | U→C | C→U | C→A | A→C | C→G | A→U | U→A | G→U | U→G | ||||||||

| 0i | 0 | (3.7 ± 0.7) × 106 | (1.0 ± 0.01) × 1010 | 3.7 × 10−4 | 4.8 × 10−4 | 0.29 | 34,720 | 10 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 20i | 0 | (6.3 ± 5.0) × 104 | (4.6 ± 0.09) × 109 | 1.3 × 10−5 | 1.1 × 10−3 | 0.73 | 81,200 | 30 | 26 | 12 | 17 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 0 |

| 100i | 0 | ND | (1.9 ± 0.02) × 108 | 1.7 × 10−7 | 4.4 × 10−4 | 0.29 | 40,880 | 11 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0j | 100 | (2.0 ± 0.6) × 106 | (1.5 ± 0.1) × 1010 | 1.3 × 10−4 | 6.1 × 10−4 | 0.30 | 44,240 | 11 | 1 | 11 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 20j | 100 | (1.2 ± 0.02) × 106 | (8.7 ± 1.0) × 109 | 1.3 × 10−4 | 5.4 × 10−4 | 0.32 | 40,320 | 9 | 1 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 100j | 100 | (1.2 ± 0.2) × 105 | (1.1 ± 0.08) × 1010 | 1.0 × 10−5 | 8.4 × 10−4 | 0.46 | 41,440 | 10 | 5 | 15 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

BHK-21 cell monolayers were infected at an MOI of 10 PFU/cell, and the infection was allowed to proceed in the presence of 0, 20, or 100 μM ribavirin and 0 or 100 μM guanosine, as detailed in Materials and Methods.

Titer (see Materials and Methods) of LCMV populations obtained at 48 h postinfection (hpi). The corresponding background (time zero; after washing the monolayers) for each infection has been subtracted from the values obtained at subsequent times. ND, not detectable (the limit of detection is 33 PFU/ml).

RNA quantification (described in Materials and Methods) of LCMV populations obtained at 48 hpi. The corresponding background (time zero; after washing the monolayers) for each infection has been subtracted from the values obtained at subsequent times.

Ratio between virus titer and number of viral RNA molecules per ml of the LCMV populations obtained at 48 hpi.

Average number of mutations per nucleotide relative to the corresponding consensus sequence.

Shannon entropy (S) is a measure of the number of different molecules in the mutant spectrum of the quasispecies. It is calculated by the formula S = −[∑i (pi × ln pi)]/ln N, in which pi is the frequency of each sequence in the quasispecies and N is the total number of sequences compared.

Residues 3654 to 4260 (560 nucleotides) from the large (L) gene were sequenced.

Omitted transversions were not represented in the sequences analyzed.

Differences in the mutation frequency and Shannon entropy between the population produced in the absence of ribavirin and in the presence of 20 μM ribavirin and also between the population produced in the presence of 20 μM and 100 μM ribavirin were statistically significant (P < 0.05 by χ2 test).

Differences in the mutation frequency and Shannon entropy between the three populations were not statistically significant (P = 0.8165 by χ2 test).

Effect of guanosine on the inhibitory and mutagenic activity of ribavirin exerted on LCMV.

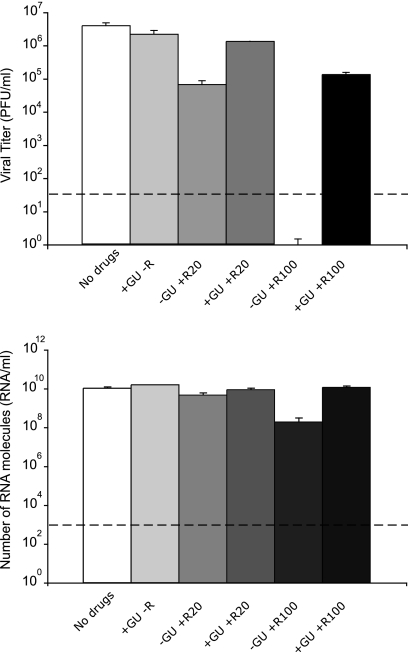

In the cell, ribavirin is phosphorylated into ribavirin mono-, di-, and triphosphate (RMP, RDP, and RTP, respectively) by cellular enzymes (91, 98). RMP acts as a competitive inhibitor of inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH) and reduces the intracellular concentration of GTP (33, 90, 91). RTP is used as a substrate by the RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RdRps) of picornaviruses in place of GTP or ATP during RNA elongation resulting in mutagenesis of viral RNA (3, 18, 30, 37, 69, 87). The addition of guanosine to the cell culture medium can restore intracellular GTP levels despite the presence of RMP (5, 50, 54, 98). To study whether GTP levels were involved in the inhibition and mutagenesis of LCMV by ribavirin, single-step infections were carried out in the presence or absence of ribavirin and in the presence of 100 μM guanosine, a concentration that compensates for the decrease of GTP produced by ribavirin treatment of BHK-21 cells (5). The results (Fig. 2 and Table 1) show that the presence of guanosine in the culture medium greatly reduced the inhibition of infectious LCMV progeny production by 100 μM ribavirin (16.6-fold decrease of infectious progeny production in the presence of guanosine versus at least a 112,121-fold reduction in the absence of guanosine [Table 1]). Guanosine also prevented the increase of mutation frequency and Shannon entropy associated with the presence of 20 μM ribavirin and abolished the differences in the frequency of transition types observed between the mutant spectra of LCMV passaged in the presence and absence of 20 μM ribavirin (Table 1). Thus, the inhibitory and mutagenic activities of ribavirin exerted on LCMV during virus replication were largely overcome by the presence of guanosine in the culture medium, suggesting that inhibition and mutagenesis of LCMV by ribavirin were mediated or enhanced by low intracellular GTP levels.

Fig. 2.

LCMV progeny production in the presence or absence of ribavirin (R) and guanosine (GU). BHK-21 cells were infected with LCMV Arm 53b at an MOI of 10 PFU/cell either in the absence of drugs or in the presence of 100 μM guanosine (+GU) or 20 μM or 100 μM ribavirin (+R20 and +R100, respectively) (−R, no ribavirin), as indicated for each column. LCMV infectivity (top panel) and number of LCMV RNA molecules measured by quantitative RT-PCR (bottom panel) were determined in the cell culture supernatant at 48 h p.i. Background values (PFU/ml and RNA/ml measured at time zero) have been subtracted from each titer and number of RNA molecules, respectively. The broken lines indicate the limit of detection for LCMV infectivity and the number of RNA molecules. Values are means of triplicate determinations, and standard deviations are given. Procedures for infections, titration by plaque assay and LCMV RNA quantification are described in Materials and Methods.

Effect of treatment with mycophenolic acid on LCMV multiplication in cultured cells.

Low intracellular GTP caused by ribavirin treatment may favor misincorporation of AMP (if RTP is not a substrate for LCMV polymerase) or both AMP and RMP (if RTP is a substrate for the polymerase) in place of GMP. To quantitate the mutagenic activity evoked by low intracellular GTP levels in the absence of ribavirin, we conducted LCMV infections in the presence or absence of MPA, an inhibitor of IMPDH that cannot be incorporated into nucleic acids (33). We conducted single-step LCMV infections (MOI of 10 PFU/cell) in the presence or absence of 5 and 30 μM MPA, as 30 μM MPA results in a decrease of intracellular GTP levels at least equal to the decrease produced by 500 μM ribavirin (5). The infections were done in the presence or absence of 100 μM guanosine. The results (Table 2) show that MPA reduced LCMV infectious progeny production by 2.1- to 2.3-fold, an inhibition which is at least 48,000-fold lower than the inhibition produced by ribavirin (compare Tables 1 and 2). Guanosine totally compensated for the inhibition exerted by MPA on LCMV progeny production (Table 2). The presence of MPA did not lead to any increase in mutant spectrum complexity, a result which contrasts with that obtained with 20 μM ribavirin (Tables 1 and 2). In fact, the mutation frequency and Shannon entropy of the LCMV that replicated in the presence of 30 μM MPA decreased 4.3- and 3.6-fold, respectively, relative to the populations replicated in the absence of MPA (Table 2). Thus, in contrast to ribavirin, MPA is not mutagenic for LCMV. The decrease of mutant spectrum complexity in the presence of MPA was associated mainly with a lower frequency of A→G and U→ C transitions, the transition types that LCMV tends to produce during replication. This lower frequency is expected if this mutational tendency is favored by high intracellular GTP concentrations during LCMV replication. Surprisingly, the amount of LCMV progeny RNA decreased significantly in the virus produced in the presence of MPA (P < 0.05 by Student's t test) (Table 2). As a consequence, the specific infectivity of the LCMV produced in these infections was 1.2- to 3.2-fold higher than that of the population generated in the absence of drugs. Since mutagenesis of RNA viruses is associated with decreases in specific infectivity (2, 3, 34, 35, 39, 40, 76, 77), the increase in specific infectivity that the virus undergoes in the presence of MPA and guanosine reinforces the conclusion of the absence of mutagenic activity of MPA on LCMV. How alterations of intracellular GTP levels can modify the specific infectivity of LCMV is unknown (see Discussion). Thus, the mutagenic activity of ribavirin cannot be attributed to the inhibition of IMPDH exerted by RMP.

Table 2.

Quasispecies analysis of LCMV populations produced in the presence or absence of mycophenolic acid and guanosinea

| Mycophenolic acid concn (μM) | Guanosine concn (μM) | Progeny infectivity (PFU/ml)b | Progeny RNA (mol/ml)c | Specific infectivity (PFU/mol of RNA)d | Mutation frequencye | Shannon entropyf | No. of nucleotides sequencedg | Mutation types |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transition |

Transversionh |

|||||||||||||

| A→G | G→A | U→C | C→U | C→A | A→C | A→U | ||||||||

| 0 | 0 | (1.9 ± 0.5) × 105 | (1.0 ± 0.01) × 1010 | 1.9 × 10−5 | 4.8 × 10−4 | 0.29 | 34,720 | 10 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| 100 | (1.7 ± 0.5) × 105 | (1.5 ± 0.1) × 1010 | 1.1 × 10−5 | 6.1 × 10−4 | 0.30 | 44,240 | 11 | 1 | 11 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | |

| 5 | 0 | (8.1 ± 3.6) × 104 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 100 | (2.4 ± 0.2) × 105 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| 30 | 0 | (9.0 ± 2.0) × 104 | (3.7 ± 0.3) × 109 | 2.4 × 10−5 | 1.1 × 10−4 | 0.08 | 53,200 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 100 | (5.5 ± 1.2) × 105 | (1.5 ± 0.0) × 1010 | 3.6 × 10−5 | 1.9 × 10−4 | 0.12 | 53,200 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

BHK-21 cell monolayers were infected at an MOI of 10 PFU/cell, and the infection was allowed to proceed in the presence of 0, 5 or 30 μM mycophenolic acid (MPA) and 0 or 100 μM guanosine, as detailed in Materials and Methods. ND, not determined.

Titer (see Materials and Methods) of LCMV populations obtained at 48 hpi. The corresponding background (time zero; after washing the monolayers) for each infection has been subtracted from the remaining collected times.

RNA quantification (described in Materials and Methods) of LCMV populations obtained at 48 hpi. The corresponding background (time zero; after washing the monolayers) for each infection has been subtracted from the values obtained at subsequent times.

Ratio between virus titer and number of viral RNA molecules per ml of LCMV population obtained at 48 hpi.

Average number of mutations per nucleotide relative to the corresponding consensus sequence.

Shannon entropy (S) is a measure of the number of different molecules in the mutant spectrum of the quasispecies. It is calculated by the formula S = −[∑i (pi × ln pi)]/ln N, in which pi is the frequency of each sequence in the quasispecies and N is the total number of sequences compared.

Residues 3654 to 4260 (560 nucleotides) from the L gene were sequenced.

Omitted transversions are not represented in the sequences analyzed.

Assessment of ribavirin mutagenic activity and its prevention by guanosine during serial LCMV infections in cultured cells.

The mutagenic activity of ribavirin on LCMV and its compensation by guanosine (Fig. 2 and Table 1) were studied in single-step infections carried out at a high MOI. The IC99 for ribavirin was 3-fold higher in the infections carried out at an MOI of 10 PFU/cell than at 0.01 PFU/cell (Fig. 1). Infection at a high MOI promotes accumulation of defective interfering (DI) particles of LCMV (80, 95, 96), whereas infection at a low MOI acts as a filter to eliminate DI particles whose replication is dependent on standard, infectious LCMV. Previous studies showed that a subset of defective but RNA replication-competent LCMVs termed defectors could interfere with replication of standard LCMV and contribute to virus extinction (40, 42, 63). Since the proportion of defector LCMV genomes increases with moderate intensities of mutagenesis (40), it was important to ascertain that the mutagenic activity of ribavirin observed during LCMV infection at a high MOI was not dependent on DI particles and defector genomes. To achieve this aim, we conducted parallel infections of BHK-21 cells at a low (0.01 PFU/cell) and high (10 PFU/cell) MOI in the presence of increasing concentrations of ribavirin (Fig. 3). Quantification of infectivity and viral RNA after the first passage shows that the inhibition of infectious progeny production by ribavirin measured at 24 h and 48 h postinfection (p.i.) was 100- to 300-fold higher at a low MOI than at a high MOI (Fig. 3A and B). In contrast, the decrease in viral RNA progeny production by ribavirin was less pronounced at 48 h p.i. and almost absent at 24 h p.i. at a low MOI (Fig. 3C and D).

Fig. 3.

Inhibition of LCMV progeny production by ribavirin. BHK-21 cells were infected with LCMV Arm 53b at an MOI of either 0.01 PFU/cell (left panels) or 10 PFU/cell (right panels) in the presence of the indicated concentrations of ribavirin (R) (0 to 100 μM). The broken lines indicate the limit of detection of LCMV infectivity and number of RNA molecules. Viral titers obtained in the presence of 100 μM ribavirin at an MOI of 0.01 PFU/cell and at 48 h at an MOI of 10 PFU/cell were below the limit of detection (indicated by a short black bar next to the abscissa). Background values (PFU/ml and RNA/ml measured at time zero) have been subtracted from each titer and number of RNA molecules, respectively. (A to F) Virus titers (A and B) and number of LCMV RNA molecules measured by quantitative RT-PCR (C and D) in the supernatants of the infected cultures at 24 and 48 h postinfection were used to calculate the corresponding specific infectivities (E and F). The asterisks in parentheses indicate that a specific infectivity was calculated assuming 1 PFU/ml, since the virus titer was below the limit of detection. Procedures for infections, titration by plaque assay, and LCMV RNA quantification are described in Materials and Methods.

The different effects of ribavirin on the yield of infectious units and viral genomes resulted in a significant decrease of specific infectivity due to ribavirin activity at an MOI of 0.01 PFU/cell at high concentrations of ribavirin (100 μM), not at low concentrations of ribavirin (5 and 20 μM) (Fig. 3E). The decrease in specific infectivity in the infection carried out in the presence of 100 μM ribavirin was diminished at a high MOI (Fig. 3F). The results with an MOI of 10 PFU/cell are in agreement with those reported in the previous series of independent infections described in Table 1.

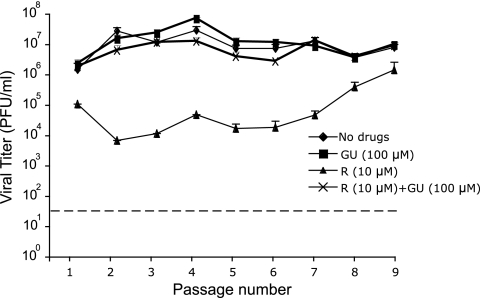

A total of nine passages were performed at a low MOI in the presence of 10 μM ribavirin to ensure continued virus infectivity (absence of extinction) over nine passages. Evolution of the infectivity values in the presence or absence of ribavirin and guanosine in the course of the nine passages indicated an inhibitory activity of ribavirin that decreased with passage number and that was largely compensated for by the presence of guanosine at all passages (Fig. 4 and Table 3). The yields of infectivity and viral RNA at passage 1 were significantly reduced by 10 μM ribavirin, resulting in a 15-fold increase in specific infectivity. At passage 9, the inhibition by ribavirin diminished and no difference in specific infectivity was detected (Fig. 4 and Table 3). The mutation frequency and Shannon entropy at passage 9 were significantly higher in the virus passaged in the presence of ribavirin than in the virus passaged in the absence of ribavirin (P < 0.005 by χ2 test), and the increase was associated with G→A and C→U transitions, the transition types expected from ribavirin mutagenesis. Guanosine compensated for the decrease of infectious progeny production and progeny RNA levels associated with the presence of ribavirin but compensated only partially for the increase of mutant spectrum complexity evoked by ribavirin (Table 3). Thus, several passage regimes indicate that ribavirin displays a dual inhibitory and mutagenic activity for LCMV during virus replication in cell culture, and both activities can be either totally or partially prevented by the presence of guanosine in the culture medium. The mutagenic activity of ribavirin on LCMV cannot be explained as a result of the inhibition of IMPDH by RMP.

Fig. 4.

Infectious progeny production during serial passages of LCMV in the presence of ribavirin and guanosine. BHK-21 cells were infected with LCMV Arm 53b at an MOI of 0.01 PFU/cell either in the presence or absence of 10 μM ribavirin (R) or 100 μM guanosine (GU), or both, as indicated. The progeny virus was used to infect a fresh BHK-21 cell monolayer under the same conditions, and infection was repeated for a total of nine passages. Virus titers were determined in triplicate in the supernatant of the infected cultures at 48 h p.i. The broken line indicates the limit of detection of LCMV infectivity. Procedures for infections in the presence or absence of drugs and titration by plaque assay are described in Materials and Methods.

Table 3.

Quasispecies analysis of LCMV populations subjected to nine low-MOI passages in the presence or absence of ribavirin and guanosinea

| Passage | Ribavirin concn (μM) | Guanosine concn (μM) | Progeny infectivity (PFU/ml)b | Progeny RNA (mol/ml)c | Specific infectivity (PFU/mol of RNA)d | Mutation frequencye | Shannon entropyf | No. of nucleotides sequencedg | Mutation types |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transition |

Transversionh |

||||||||||||||||

| A→G | G→A | U→C | C→U | U→A | C→A | G→U | U→G | A→C | |||||||||

| Passage 1 | 0i | 0 | (1.5 ± 0.8) × 106 | (4.9 ± 0.9) × 109 | 3.0 × 10−4 | 1.1 × 10−4 | 0.08 | 53,200 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 10i | 0 | (9.9 ± 0.1) × 104 | (2.2 ± 0.6) × 107 | 4.5 × 10−3 | 2.0 × 10−4 | 0.13 | 44,800 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Passage 9 | 0i | 0 | (8.0 ± 2.2) × 106 | (5.5 ± 0.2) × 1010 | 1.4 × 10−4 | 1.9 × 10−4 | 0.12 | 48,160 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 100 | (1.1 ± 0.2) × 107 | (1.6 ± 0.2) × 1010 | 6.8 × 10−4 | 1.4 × 10−4 | 0.09 | 49,280 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 10i | 0 | (1.7 ± 0.8) × 106 | (1.7 ± 0.2) × 1010 | 1.0 × 10−4 | 1.0 × 10−3 | 0.37 | 106,960 | 1 | 32 | 5 | 70 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| 100 | (8.3 ± 1.2) × 106 | (9.4 ± 0.9) × 1010 | 8.8 × 10−5 | 5.2 × 10−4 | 0.28 | 96,320 | 17 | 15 | 7 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

Nine serial passages of LCMV in BHK-21 cells at an MOI of 0.01 PFU/cell in the presence or absence of 10 μM ribavirin and/or 100 μM guanosine were performed, as detailed in Materials and Methods. Passages one and nine are analyzed.

Titer (see Materials and Methods) of LCMV populations obtained at 48 hpi. The corresponding background (time zero; after washing the monolayers) for each infection has been subtracted from the remaining collected times.

RNA quantification (described in Materials and Methods) of LCMV populations obtained at 48 hpi. The corresponding background (time zero; after washing the monolayers) for each infection has been subtracted from the values obtained at subsequent times.

Ratio between virus titer and number of viral RNA molecules per ml of LCMV populations obtained at 48 hpi.

Average number of mutations per nucleotide relative to the corresponding consensus sequence.

Shannon entropy (S) is a measure of the number of different molecules in the mutant spectrum of the quasispecies. It is calculated by the formula S = −[∑i (pi × ln pi)]/ln N, in which pi is the frequency of each sequence in the quasispecies and N is the total number of sequences compared.

Residues 3654 to 4260 (560 nucleotides) from the L gene were sequenced.

Omitted transversions were not represented in the sequences analyzed.

Differences in the mutation frequency and Shannon entropy between the population subjected to 9 passages in the presence of 10 μM ribavirin and any other population analyzed were statistically significant (P < 0.05 by χ2 test).

DISCUSSION

The results described in the present study establish ribavirin as a mutagenic agent for LCMV replicating in cell culture. It remains to be determined whether this mutagenic activity of ribavirin can also be observed in LCMV-infected mice and whether these findings could be extended to other arenaviruses. Ribavirin has been shown to be mutagenic for several RNA viruses (3, 16, 17, 38, 54, 84, 87). However, for some other RNA viruses tested, ribavirin did not exhibit noticeable mutagenic activity (57, 59). Ribavirin is currently the only drug therapy recommended to treat arenavirus infections, but its mechanism of action has not been entirely elucidated. There is, however, evidence indicating that ribavirin likely targets different steps of the arenavirus life cycle (58, 75).

We have now provided evidence that at subinhibitory concentrations, ribavirin exerts a mutagenic activity on LCMV. One could envision at least two distinct mechanisms by which ribavirin could exert a mutagenic activity on LCMV. (i) RMP could mediate the inhibition of IMPDH, which could result in depletion of intracellular GTP (33, 91), which would facilitate incorporation of ATP instead of GTP opposite C in the template (53, 65). (ii) RTP might be used as a substrate by the arenavirus polymerase and be incorporated instead of ATP or GTP during arenavirus RNA synthesis. The subsequent ambiguous reading within the template RNA of reading ribavirin as G or A would result in increased numbers of mutations during virus RNA replication as reported for picornaviruses (3, 17, 18, 87). These two mechanisms are not mutually exclusive, and both could contribute to the mutagenic activity of ribavirin. Our finding that MPA at concentrations in excess of those required to produce the same depletion of GTP levels as found with 100 μM ribavirin in BHK-21 cells (5) did not display any detectable mutagenic activity for LCMV (Table 2) supports the conclusion that RMP-mediated inhibition of IMPDH cannot account for the mutagenic activity of ribavirin on LCMV.

Guanosine largely reversed the inhibition of LCMV progeny production exerted by either MPA or ribavirin (Fig. 2 and 4 and Tables 1 and 3). Interestingly, the ribavirin-induced increase in mutation frequency and Shannon entropy observed in infections done at a high, but not at a low, MOI were prevented by the guanosine treatment (Tables 1 and 3). At the concentration used, guanosine restores normal intracellular GTP levels in BHK-21 cells (5), suggesting that the inhibitory activity of ribavirin on LCMV is likely associated with decreased GTP levels caused by RMP-mediated inhibition of IMPDH, whereas the mutagenic activity of ribavirin likely reflects its incorporation by the arenavirus polymerase into nascent RNA molecules during virus replication. A direct demonstration of a competition between RTP and GTP or ATP during LCMV RNA synthesis will require in vitro assays to assess the incorporation of RTP by the LCMV RdRp and the isolation and mapping of ribavirin resistance mutations in LCMV. It is worth noting that the observed decrease in ribavirin-mediated inhibition of LCMV replication during serial passages in the presence of 10 μM ribavirin suggests the possible selection of an LCMV population with decreased sensitivity to ribavirin, whose mutant spectrum tends to become enriched in transition mutations (Fig. 4 and Table 3). This is a subject currently under investigation in our laboratory.

Our results raise the question of whether the inhibitory and mutagenic activities of ribavirin on LCMV are independent or related. It is plausible that the strong inhibition of LCMV production at high ribavirin concentrations was due to lethal mutagenesis. Evidence against this possibility is the fact that viral populations grown in the presence or absence of a high concentration (100 μM) of ribavirin exhibited similar mutation frequencies and Shannon entropies (Table 1). A counterargument, however, is that highly mutated genomes do not survive to be analyzed, and therefore, the genomes subjected to analysis were mainly genomes that underwent none, or minimal, replication. It should be noted that LCMV progeny produced in the presence of 100 μM ribavirin displayed a severe reduction in specific infectivity (Fig. 3E and F), a hallmark of the transition of viruses into error catastrophe (34, 40).

The findings presented here open the possibility that the antiarenavirus activity of ribavirin might be exerted at least in part through its mutagenic activity. There is evidence that in whole organisms, ribavirin accumulates in blood rather than in organs (15, 25, 47). Therefore, it is likely that in tissues where LCMV replicates ribavirin, it is present at subinhibitory, rather than inhibitory, concentrations. Notably, the mutagenic activity of ribavirin could be observed at subinhibitory concentrations of ribavirin. Nevertheless, it may be difficult to associate a therapeutic activity of ribavirin with mutagenesis during treatment of human arenavirus infections, as exemplified by the conflicting evidence in the case of ribavirin treatment of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections (8, 14, 20, 61, 78), despite evidence of mutagenesis in HCV replicon systems (16, 48, 79, 97). The role of mutagenesis versus inhibition in the anti-LCMV activity of ribavirin remains an open issue.

Whether an antiviral drug acts mainly as an inhibitor of virus multiplication or as a mutagen is highly relevant for the design of the optimal treatment protocols. Combination therapy is generally accepted as a necessity to prevent or delay selection of inhibitor-resistant viral mutants (10, 19, 46, 52, 56, 70, 71, 93). However, when a mutagenic agent is one of the components of drug therapy, the sequential administration of giving the inhibitor first and then the mutagenic agent can be more effective than the corresponding combination treatment (77). Therefore, the use of ribavirin in combination therapy with novel antiarenavirus drugs yet to be developed would benefit from determining the contribution of ribavirin-mediated mutagenic effects to its overall antiarenavirus activity. Certainly, the demonstration of viral mutagenesis by ribavirin in arenavirus-infected individuals would not exclude a beneficial effect of ribavirin by any of the alternative antiviral mechanisms displayed by this nucleoside analogue (38, 58, 75, 90).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Work at the Centro de Biología Molecular Severo Ochoa was supported by grant BFU2008-02816/BMC from the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (MICINN) and Fundación R. Areces. The Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Hepáticas y Digestivas (CIBERehd) is funded by Instituto de Salud Carlos III. Work at the Centro de Investigación en Sanidad Animal was supported by grants RYC-2010-06516 and AGL2004-0049 and by EPIZONE (contract FOOD-CT-2006-016236). Work at The Scripps Research Institute is supported by NIH grant RO1 AI047140 to J.C.D.L.T.

We thank A. I. de ÁAvila for expert technical assistance, H. Tejero for help with statistics, and C. Perales and J. Sheldon for critically reading the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 11 May 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Acosta E. G., et al. 2008. Dehydroepiandrosterone, epiandrosterone and synthetic derivatives inhibit Junin virus replication in vitro. Virus Res. 135:203–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Agudo R., et al. 2008. Molecular characterization of a dual inhibitory and mutagenic activity of 5-fluorouridine triphosphate on viral RNA synthesis. Implications for lethal mutagenesis. J. Mol. Biol. 382:652–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Agudo R., et al. 2010. A multi-step process of viral adaptation to a mutagenic nucleoside analogue by modulation of transition types leads to extinction-escape. PLoS Pathog. 6(8):e1001072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ahmed R., et al. 1988. Genetic analysis of in vivo-selected viral variants causing chronic infection: importance of mutation in the L RNA segment of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. J. Virol. 62:3301–3308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Airaksinen A., Pariente N., Menendez-Arias L., Domingo E. 2003. Curing of foot-and-mouth disease virus from persistently infected cells by ribavirin involves enhanced mutagenesis. Virology 311:339–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Anderson J. P., Daifuku R., Loeb L. A. 2004. Viral error catastrophe by mutagenic nucleosides. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 58:183–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Arias A., et al. 2008. Determinants of RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (in)fidelity revealed by kinetic analysis of the polymerase encoded by a foot-and-mouth disease virus mutant with reduced sensitivity to ribavirin. J. Virol. 82:12346–12355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Asahina Y., et al. 2005. Mutagenic effects of ribavirin and response to interferon/ribavirin combination therapy in chronic hepatitis C. J. Hepatol. 43:623–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Barton L. L. 1996. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus: a neglected central nervous system pathogen. Clin. Infect. Dis. 22:197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bonhoeffer S., May R. M., Shaw G. M., Nowak M. A. 1997. Virus dynamics and drug therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94:6971–6976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bowen M. D., Peters C. J., Nichol S. T. 1997. Phylogenetic analysis of the Arenaviridae: patterns of virus evolution and evidence for cospeciation between arenaviruses and their rodent hosts. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 8:301–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Briese T., et al. 2009. Genetic detection and characterization of Lujo virus, a new hemorrhagic fever-associated arenavirus from southern Africa. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Buchmeier M. J., de la Torre J. C., Peters C. J. 2007. Arenaviridae: the viruses and their replication, p. 1791–1827 In Knipe D. M., Howley P. M. (ed.), Fields virology, 5th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chevaliez S., Brillet R., Lazaro E., Hezode C., Pawlotsky J. M. 2007. Analysis of ribavirin mutagenicity in human hepatitis C virus infection. J. Virol. 81:7732–7741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Connor E., et al. 1993. Safety, tolerance, and pharmacokinetics of systemic ribavirin in children with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:532–539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Contreras A. M., et al. 2002. Viral RNA mutations are region specific and increased by ribavirin in a full-length hepatitis C virus replication system. J. Virol. 76:8505–8517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Crotty S., Cameron C. E., Andino R. 2001. RNA virus error catastrophe: direct molecular test by using ribavirin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:6895–6900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Crotty S., et al. 2000. The broad-spectrum antiviral ribonucleotide, ribavirin, is an RNA virus mutagen. Nat. Med. 6:1375–1379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cubero M., et al. 2008. Naturally occurring NS3-protease-inhibitor resistant mutant A156T in the liver of an untreated chronic hepatitis C patient. Virology 370:237–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cuevas J. M., Gonzalez-Candelas F., Moya A., Sanjuan R. 2009. Effect of ribavirin on the mutation rate and spectrum of hepatitis C virus in vivo. J. Virol. 83:5760–5764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cummings K. J., et al. 2001. Interferon and ribavirin vs interferon alone in the re-treatment of chronic hepatitis C previously nonresponsive to interferon: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA 285:193–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Davis G. L., et al. 1998. Interferon alfa-2b alone or in combination with ribavirin for the treatment of relapse of chronic hepatitis C. International Hepatitis Interventional Therapy Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 339:1493–1499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Di Bisceglie A. M., Thompson J., Smith-Wilkaitis N., Brunt E. M., Bacon B. R. 2001. Combination of interferon and ribavirin in chronic hepatitis C: re-treatment of nonresponders to interferon. Hepatology 33:704–707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Domingo E. (ed.). 2005. Virus entry into error catastrophe as a new antiviral strategy. Virus Res. 107:115–228 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dusheiko G., Nelson D., Reddy K. R. 2008. Ribavirin considerations in treatment optimization. Antivir. Ther. 13(Suppl. 1):23–30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dutko F. J., Oldstone M. B. A. 1983. Genomic and biologic variation among commonly used lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus strains. J. Gen. Virol. 64:1689–1694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Emonet S., Lemasson J. J., Gonzalez J. P., de Lamballerie X., Charrel R. N. 2006. Phylogeny and evolution of old world arenaviruses. Virology 350:251–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Emonet S. F., de la Torre J. C., Domingo E., Sevilla N. 2009. Arenavirus genetic diversity and its biological implications. Infect. Genet. Evol. 9:417–429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Enria D. A., Maiztegui J. I. 1994. Antiviral treatment of Argentine hemorrhagic fever. Antiviral Res. 23:23–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ferrer-Orta C., et al. 2010. Structure of foot-and-mouth disease virus mutant polymerases with reduced sensitivity to ribavirin. J. Virol. 84:6188–6199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fischer S. A., et al. 2006. Transmission of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus by organ transplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 354:2235–2249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fox E. J., Loeb L. A. 2010. Lethal mutagenesis: targeting the mutator phenotype in cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 20:353–359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Franklin T. J., Cook J. M. 1969. The inhibition of nucleic acid synthesis by mycophenolic acid. Biochem. J. 113:515–524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. González-López C., Arias A., Pariente N., Gómez-Mariano G., Domingo E. 2004. Preextinction viral RNA can interfere with infectivity. J. Virol. 78:3319–3324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. González-López C., Gómez-Mariano G., Escarmís C., Domingo E. 2005. Invariant aphthovirus consensus nucleotide sequence in the transition to error catastrophe. Infect. Genet. Evol. 5:366–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gowen B. B., et al. 2008. Treatment of late stage disease in a model of arenaviral hemorrhagic fever: T-705 efficacy and reduced toxicity suggests an alternative to ribavirin. PLoS One 3:e3725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Graci J. D., Cameron C. E. 2006. Mechanisms of action of ribavirin against distinct viruses. Rev. Med. Virol. 16:37–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Graci J. D., Cameron C. E. 2008. Therapeutically targeting RNA viruses via lethal mutagenesis. Future Virol. 3:553–566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Grande-Pérez A., Gómez-Mariano G., Lowenstein P. R., Domingo E. 2005. Mutagenesis-induced, large fitness variations with an invariant arenavirus consensus genomic nucleotide sequence. J. Virol. 79:10451–10459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Grande-Pérez A., Lazaro E., Lowenstein P., Domingo E., Manrubia S. C. 2005. Suppression of viral infectivity through lethal defection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:4448–4452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Grande-Pérez A., Sierra S., Castro M. G., Domingo E., Lowenstein P. R. 2002. Molecular indetermination in the transition to error catastrophe: systematic elimination of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus through mutagenesis does not correlate linearly with large increases in mutant spectrum complexity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:12938–12943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Iranzo J., Manrubia S. C. 2009. Stochastic extinction of viral infectivity through the action of defectors. Europhys. Lett. 85:18001 [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jahrling P. B., et al. 1980. Lassa virus infection of rhesus monkeys: pathogenesis and treatment with ribavirin. J. Infect. Dis. 141:580–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jahrling P. B., Peters C. J., Stephen E. L. 1984. Enhanced treatment of Lassa fever by immune plasma combined with ribavirin in cynomolgus monkeys. J. Infect. Dis. 149:420–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jamieson D. J., Kourtis A. P., Bell M., Rasmussen S. A. 2006. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus: an emerging obstetric pathogen? Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 194:1532–1536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Johnson J. A., et al. 2008. Minority HIV-1 drug resistance mutations are present in antiretroviral treatment-naive populations and associate with reduced treatment efficacy. PLoS Med. 5:e158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Jordan I., Briese T., Fischer N., Lau J. Y., Lipkin W. I. 2000. Ribavirin inhibits West Nile virus replication and cytopathic effect in neural cells. J. Infect. Dis. 182:1214–1217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kanda T., et al. 2004. Inhibition of subgenomic hepatitis C virus RNA in Huh-7 cells: ribavirin induces mutagenesis in HCV RNA. J. Viral. Hepat. 11:479–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kenyon R. H., Canonico P. G., Green D. E., Peters C. J. 1986. Effect of ribavirin and tributylribavirin on Argentine hemorrhagic fever (Junin virus) in guinea pigs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 29:521–523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kerr S. J. 1987. Ribavirin induced differentiation of murine erythroleukemia cells. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 77:187–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kilgore P. E., et al. 1997. Treatment of Bolivian hemorrhagic fever with intravenous ribavirin. Clin. Infect. Dis. 24:718–722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kuntzen T., et al. 2008. Naturally occurring dominant resistance mutations to hepatitis C virus protease and polymerase inhibitors in treatment-naive patients. Hepatology 48:1769–1778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kunz B. A., et al. 1994. International Commission for Protection Against Environmental Mutagens and Carcinogens. Deoxyribonucleoside triphosphate levels: a critical factor in the maintenance of genetic stability. Mutat. Res. 318:1–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lanford R. E., et al. 2001. Ribavirin induces error-prone replication of GB virus B in primary tamarin hepatocytes. J. Virol. 75:8074–8081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lee A. M., et al. 2008. Inhibition of cellular entry of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus by amphipathic DNA polymers. Virology 372:107–117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Le Moing V., et al. 2002. Predictors of virological rebound in HIV-1-infected patients initiating a protease inhibitor-containing regimen. AIDS 16:21–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Leyssen P., Balzarini J., De Clercq E., Neyts J. 2005. The predominant mechanism by which ribavirin exerts its antiviral activity in vitro against flaviviruses and paramyxoviruses is mediated by inhibition of IMP dehydrogenase. J. Virol. 79:1943–1947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Leyssen P., De Clercq E., Neyts J. 2008. Molecular strategies to inhibit the replication of RNA viruses. Antiviral Res. 78:9–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Leyssen P., De Clercq E., Neyts J. 2006. The anti-yellow fever virus activity of ribavirin is independent of error-prone replication. Mol. Pharmacol. 69:1461–1467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lucia H. L., Coppenhaver D. H., Baron S. 1989. Arenavirus infection in the guinea pig model: antiviral therapy with recombinant interferon-alpha, the immunomodulator CL246,738 and ribavirin. Antiviral Res. 12:279–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Lutchman G., et al. 2007. Mutation rate of the hepatitis C virus NS5B in patients undergoing treatment with ribavirin monotherapy. Gastroenterology 132:1757–1766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Maag D., Castro C., Hong Z., Cameron C. E. 2001. Hepatitis C virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (NS5B) as a mediator of the antiviral activity of ribavirin. J. Biol. Chem. 276:46094–46098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Martin V., Abia D., Domingo E., Grande-Perez A. 2010. An interfering activity against lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus replication associated with enhanced mutagenesis. J. Gen. Virol. 91:990–1003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Martín V., Grande-Pérez A., Domingo E. 2008. No evidence of selection for mutational robustness during lethal mutagenesis of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. Virology 378:185–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Martínez M. A., Vartanian J. P., Wain-Hobson S. 1994. Hypermutagenesis of RNA using human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase and biased dNTP concentrations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91:11787–11791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. McCormick J. B., et al. 1986. Lassa fever. Effective therapy with ribavirin. N. Engl. J. Med. 314:20–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. McHutchison J. G., et al. 1998. Interferon alfa-2b alone or in combination with ribavirin as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis C. Hepatitis Interventional Therapy Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 339:1485–1492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Mendenhall M., et al. 2011. T-705 (favipiravir) inhibition of arenavirus replication in cell culture. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:782–787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Moriyama K., et al. 2008. Effects of introduction of hydrophobic group on ribavirin base on mutation induction and anti-RNA viral activity. J. Med. Chem. 51:159–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Müller V., Bonhoeffer S. 2008. Intra-host dynamics and evolution of HIV infections, p. 279–302 In Domingo E., Parrish C. R., Holland J. J. (ed.), Origin and evolution of viruses, 2nd ed. Academic Press, London, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 71. Nijhuis M., van Maarseveen N. M., Boucher C. A. 2009. Antiviral resistance and impact on viral replication capacity: evolution of viruses under antiviral pressure occurs in three phases. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 189:299–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Oldstone M. B. A. (ed.). 2002. Current topics in microbiology and immunology, vol. 262. Arenaviruses I. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 72a. Oldstone M. B. A. (ed.). 2002. Current topics in microbiology and immunology, vol. 263. Arenaviruses II. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 73. Palacios G., et al. 2008. A new arenavirus in a cluster of fatal transplant-associated diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 358:991–998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Pariente N., Airaksinen A., Domingo E. 2003. Mutagenesis versus inhibition in the efficiency of extinction of foot-and-mouth disease virus. J. Virol. 77:7131–7138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Parker W. B. 2005. Metabolism and antiviral activity of ribavirin. Virus Res. 107:165–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Perales C., Agudo R., Manrubia S. C., Domingo E. 2011. Influence of mutagenesis and viral load in sustained, low-level replication of an RNA virus. J. Mol. Biol. 407:60–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Perales C., Agudo R., Tejero H., Manrubia S. C., Domingo E. 2009. Potential benefits of sequential inhibitor-mutagen treatments of RNA virus infections. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Perelson A. S., Layden T. J. 2007. Ribavirin: is it a mutagen for hepatitis C virus? Gastroenterology 132:2050–2052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Pfeiffer J. K., Kirkegaard K. 2005. Ribavirin resistance in hepatitis C virus replicon-containing cell lines conferred by changes in the cell line or mutations in the replicon RNA. J. Virol. 79:2346–2355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Popescu M., Schaefer H., Lehmann-Grube F. 1976. Homologous interference of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus: detection and measurement of interference focus-forming units. J. Virol. 20:1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Ruiz-Jarabo C. M., Ly C., Domingo E., de la Torre J. C. 2003. Lethal mutagenesis of the prototypic arenavirus lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV). Virology 308:37–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Sánchez G., Bosch A., Gómez-Mariano G., Domingo E., Pinto R. 2003. Evidence for quasispecies distributions in the human hepatitis A virus genome. Virology 315:34–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Schmitz H., et al. 2002. Monitoring of clinical and laboratory data in two cases of imported Lassa fever. Microbes Infect. 4:43–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Severson W. E., Schmaljohn C. S., Javadian A., Jonsson C. B. 2003. Ribavirin causes error catastrophe during Hantaan virus replication. J. Virol. 77:481–488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Sevilla N., de la Torre J. C. 2006. Arenavirus diversity and evolution: quasispecies in vivo. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 299:315–335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Sidwell O. W., Simon L. N., Witkowski J. T., Robins R. K. 1974. Antiviral activity of virazole: review and structure-activity relationships. Prog. Chemother. 2:889–903 [Google Scholar]

- 87. Sierra M., et al. 2007. Foot-and-mouth disease virus mutant with decreased sensitivity to ribavirin: implications for error catastrophe. J. Virol. 81:2012–2024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Smee D. F., et al. 1993. Treatment of lethal Pichinde virus infections in weanling LVG/Lak hamsters with ribavirin, ribamidine, selenazofurin, and ampligen. Antiviral Res. 20:57–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Smith R. A., Kirkpatrick W. 1980. Ribavirin: a broad spectrum antiviral agent. Academic Press, Inc., New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 90. Snell N. J. 2001. Ribavirin-current status of a broad spectrum antiviral agent. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2:1317–1324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Streeter D. G., et al. 1973. Mechanism of action of 1-β-d-ribofuranosyl-1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxamide (Virazole), a new broad-spectrum antiviral agent. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 70:1174–1178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Tapia N., et al. 2005. Combination of a mutagenic agent with a reverse transcriptase inhibitor results in systematic inhibition of HIV-1 infection. Virology 338:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Van Vaerenbergh K., et al. 2002. Initiation of HAART in drug-naive HIV type 1 patients prevents viral breakthrough for a median period of 35.5 months in 60% of the patients. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 18:419–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Volkenstein M. V. 1994. Physical approaches to biological evolution. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 95. Welsh R. M., et al. 1975. A comparison of biochemical and biological properties of standard and defective lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. Bull. World Health Organ. 52:403–408 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Welsh R. M., O'Connell C. M., Pfau C. J. 1972. Properties of defective lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. J. Gen. Virol. 17:355–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Zhou S., Liu R., Baroudy B. M., Malcolm B. A., Reyes G. R. 2003. The effect of ribavirin and IMPDH inhibitors on hepatitis C virus subgenomic replicon RNA. Virology 310:333–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Zimmerman T. P., Deeprose R. D. 1978. Metabolism of 5-amino-1-beta-d-ribofuranosylimidazole-4-carboxamide and related five-membered heterocycles to 5′-triphosphates in human blood and L5178Y cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 27:709–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]