Abstract

Objectives

Osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee is a major cause of pain and limited function in older adults. Longer-term studies of medical therapy of OA are uncommon. This study was undertaken to evaluate the efficacy and safety of glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate (CS), alone or in combination, as well as celecoxib and placebo on painful knee OA over 24 months.

Methods

A 24-month, double-blind, placebo controlled study, conducted at 9 sites in the United States ancillary to the Glucosamine/Chondroitin Arthritis Intervention Trial (GAIT), enrolled 662 patients with knee OA who satisfied radiographic criteria (Kellgren/ Lawrence [K/L] grade 2 or grade 3 changes and JSW of at least 2 mm at baseline). Patients who had been randomized to 1 of the 5 groups in GAIT continued to receive glucosamine 500 mg 3 times daily, CS 400 mg 3 times daily, the combination of glucosamine and CS, celecoxib 200 mg daily, or placebo over 24 months. The primary outcome measure was the number who reached a 20% reduction in WOMAC pain over 24 months. Secondary outcomes included reaching an OMERACT/OARSI response and change from baseline in WOMAC pain and function.

Results

The odds of achieving a 20%WOMAC were 1.21 for celecoxib, 1.16 for glucosamine, 0.83 for glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate and 0.69 for chondroitin sulfate alone with widely overlapping confidence intervals for all treatments.

Conclusions

Over 2 years, no treatment achieved a clinically important difference in WOMAC Pain or Function as compared with placebo. However, glucosamine and celecoxib showed beneficial trends. Adverse reactions were not meaningfully different among treatment groups and serious adverse events were rare for all therapies.

Keywords: Osteoarthritis, nutraceutical, coxib, adverse events, efficacy

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee results in chronic pain in a sizable minority of the population and considerable expense [1] is associated with the resultant disability and costs of treatment directed to control that pain.[2-4] Conventional medications for chronic pain, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) including coxibs increase the risk for adverse events.[5] In addition, many patients with OA are on medications for long periods of time, have co-morbidities and use other medications for those illnesses, which all further increase the likelihood of adverse events. The increase in OA-related musculoskeletal pain especially in the growing elderly population has created heightened interest in effective treatments with better safety profiles. The Glucosamine/chondroitin Arthritis Intervention Trial (GAIT) was designed to examine the effects of the dietary supplements glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate given alone or in combination as compared to celecoxib or placebo on pain associated with osteoarthritis of the knee. The primary symptomatic outcome assessment of the GAIT study was after 24 weeks of randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled therapy.[6] An ancillary structural study describing the effects of the agents on radiographic joint space width loss for up to two years has also recently been reported.[7] To date, very few data have been reported for the long-term treatment of OA with any agent including the supplements and celecoxib studied here. Patients in the structural study continued to have safety and clinical efficacy assessments at all scheduled visits. This paper details the clinical efficacy and safety experience with these agents alone and in combination along with celecoxib as compared to placebo in patients from this subset of GAIT over 24 months offollow-up.

Methods

Study Design

Study subjects enrolled in the GAIT ancillary structural study met the original GAIT inclusion criteria, summarized as at least 40 years of age with clinical evidence of painful OA of the knee for at least six months and radiographic evidence of OA as determined by having a Kellgren & Lawrence grade 2- or 3-rated radiograph of the index knee. 662 of the 1583 original GAIT study participants were also in the structural study.[7] Participants in the structural study remained on their originally assigned blinded treatment for up to two years and continued to have safety monitoring and efficacy assessments as prescribed by the protocol (approximately quarterly) throughout the two-year follow-up period. Patients were asked to continue follow-up even if they stopped taking their assigned treatment. The study treatments were glucosamine hydrochloride (HCl) 500 mg three times daily, sodium chondroitin sulfate 400 mg three times daily, both glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate as above, celecoxib 200 mg once daily or placebo daily. The study included a “double dummy” and “double placebo” design. Up to four grams acetaminophen daily could be taken as rescue analgesia. Patients were instructed not to take this medication within 24 hours of a follow-up visit to allow for accurate measurement of their current pain levels.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measure for the original 6 month symptomatic GAIT study was the number of patients who attained a 20% decrease in their summed Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) Pain subscale [8] from baseline to week 24. For this 2-year follow-up study, we report the likelihood of reaching a 20% reduction in WOMAC Pain score from baseline modeled over two years in those patients who participated in this extension of the original symptomatic treatment study.

Secondary Outcome Measures

Secondary measures included the actual amount of pain reduction attributable to each therapy, and the likelihood of achieving an Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT)/Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) response over 24 months [9]. The OMERACT/OARSI response is included as it was reported in the original GAIT report, and each component had been prospectively collected. Further, the OMERACT/OARSI response at 24 weeks was more discriminating of improvement than was a 20% reduction in WOMAC Pain at 24 weeks in the original GAIT report.[6]

Adverse Events

Information on adverse events was collected per patient report at each visit in response to an open-ended query. The reported events were assessed by the investigator at each study visit and followed until resolution or end of follow-up. Adverse events or serious adverse events (SAE) were assessed per Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidelines.[10] Monitoring of vital signs, blood counts, serum glucose, aminotransferases, creatinine, partial thromboplastin time and urinalysis was also performed per protocol. An independent data and safety monitoring board reviewed study performance and safety data annually.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses compared placebo with each of the four treatments on a modified intention-to-treat basis. Baseline characteristics were compared across groups using a chi-square test for categorical variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables. Statistical testing of treatment differences, which were adjusted for the comparison of each of the 4 treatment groups with the placebo group, was performed by using multivariate t-statistics (analogous to Dunnet's t-test) to calculate 95% confidence intervals.[11] Multiple regression analyses longitudinally compared each intervention group to placebo while controlling for design factors (weeks on treatment, weeks squared (to account for non-linearity)) and literature-based clinical factors (gender, baseline pain, disease duration, body mass index (BMI) class, Kellgren & Lawrence grade) over 24 months. Logistic regression was used to analyze the odds of a response over 24 months of follow-up separately for 20% WOMAC pain reduction and OMERACT/OARSI outcomes. Linear regression was used to analyze the mean change from baseline over two years of follow-up separately for WOMAC Pain and WOMAC Function. Recognizing that dropout before the two year visit in this study may not be completely at random, we applied selection models as described by Hogan et al [12] using weighted generalized estimating equations (GEE) to estimate the multiple regression models. This form of repeated measures analysis utilizes all data collected on this cohort while accounting for potentially nonrandom dropout. These analyses were implemented with SAS 9.1®.

Results

Efficacy

Since not all patients randomized to GAIT at the ancillary sites qualified for the ancillary study, comparison of baseline data was done to assess any loss of comparability of the treatment groups due to departure from randomization. Table 1 shows the baseline data were similar among all groups with no statistically significant differences between them. Most participants were female, most had BMI >30, and their average age was nearly 57 years. The average duration of osteoarthritis symptoms was approximately 10 years. Slightly more Kellgren & Lawrence grade 3 knees were found in patients treated with the combination of glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate than in the other groups.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of the Structural Study by Group.

| Placebo | Glucosamine | Chondroitin | Glucosamine and Chondroitin | Celecoxib | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects (N) | 131 | 134 | 126 | 129 | 142 | |

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 56.9 (9.8) | 56.7 (10.5) | 56.3 (8.8) | 56.7 (10.7) | 57.6 (10.6) | 0.87 |

| Females (%) | 65.7 | 68.7 | 73.0 | 65.1 | 65.5 | 0.62 |

| BMI <25 | 25.2 | 27.6 | 30.2 | 27.1 | 25.4 | 0.97 |

| BMI 25-30 Overweight | 24.4 | 19.4 | 22.2 | 20.2 | 22.5 | |

| BMI >30 Obese | 50.4 | 53.0 | 47.6 | 52.7 | 52.1 | |

| KL 2 (%) | 61.1 | 59.7 | 66.7 | 51.9 | 62.0 | 0.19 |

| Duration OA symptoms mean (y)(SD) | 10.1 (9.4) | 9.7 (10.3) | 9.0 (9.0) | 10.0 (9.4) | 10.2 (9.2) | 0.84 |

OA=osteoarthritis; BMI= body mass index; KL=Kellgren & Lawrence grade; SD=standard deviation

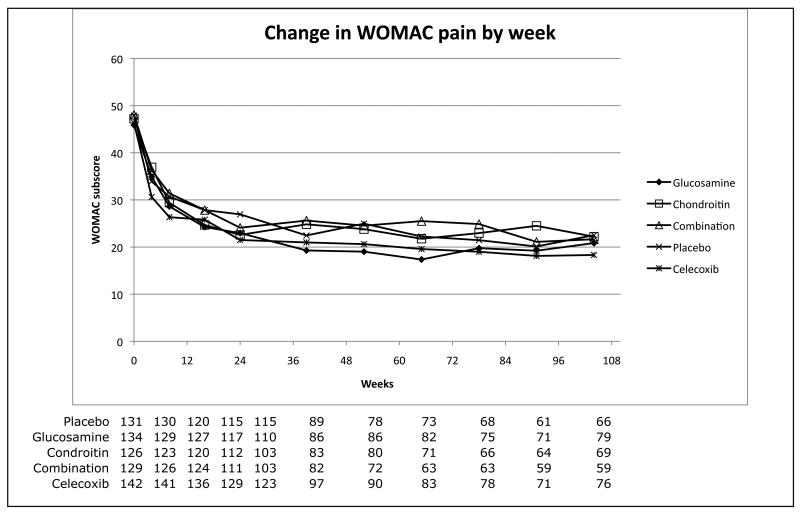

Figure 1 shows the change in WOMAC Pain and WOMAC Function over time as well as the number of participants contributing data at each visit. No statistically significant differences in dropout by group are observed. In addition, approximately 60% of the achieved improvement in outcome measures occurred within the first three visits (18 weeks) for all groups, and the magnitude of improvement did not differ significantly by treatment group. Although the rate of this improvement was most rapid for celecoxib, this does not represent a statistically significant difference when compared to placebo.

Figure 1.

Decline in WOMAC function and pain subscores versus study week. The number of participants contributing data at each visit is shown below the matching week.

The odds of achieving benefit over 24 months by use of an agent, whether defined as a 20% WOMAC Pain response or OMERACT/OARSI response is shown in Table 2. While no agent was statistically more effective than placebo, a trend toward improvement occurred with celecoxib and with glucosamine for both endpoints. The trends were most apparent when using the OMERACT/OARSI responder criteria.

Table 2. Odds of pain response over 24 months versus placebo by WOMAC and OMERACT/OARSI.

| 20% WOMAC | OMERACT/OARSI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment arm | Odds ratio* | 95% Confidence Interval | Odds ratio* | 95% Confidence Interval |

| Placebo | Reference | Reference | ||

| Glucosamine | 1.16 | 0.65 – 2.04 | 1.16 | 0.74 – 1.83 |

| Chondroitin sulfate | 0.69 | 0.40 – 1.21 | 0.89 | 0.53 – 1.50 |

| Combination | 0.83 | 0.51 – 1.34 | 0.85 | 0.55 – 1.31 |

| Celecoxib | 1.21 | 0.71 – 2.07 | 1.45 | 0.86 – 2.42 |

Odds ratio adjusted for the following baseline factors: age, gender, BMI class, pain, Kellgren & Lawrence grade as well as time in study, time squared using GEE. A confidence interval excluding 1 indicates a significant response compared to placebo group.

The specific changes in WOMAC Pain and Function subscores by treatment after adjustment for design and clinical factors are shown in Table 3. The magnitude of improvement over 24 months was greatest for celecoxib. However, when compared to placebo, no significant differences were shown for WOMAC Pain or for WOMAC Function for any of the interventions.

Table 3. Change in WOMAC pain and function score over 24 months versus placebo.

| WOMAC pain | WOMAC function | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment arm | Decline in pain score* | Difference from placebo | 95% CI for difference from placebo | Decline in function score* | Difference from placebo | 95% CI for difference from placebo |

| Placebo | 151.04 | Reference | 393.40 | Reference | ||

| Glucosamine | 155.88 | -4.84 | -28.29 – 18.61 | 383.84 | 9.56 | -79.79 – 98.91 |

| Chondroitin sulfate | 139.54 | 11.50 | -15.40 – 38.40 | 356.76 | 36.64 | -64.57 – 137.86 |

| Combination | 150.00 | 1.04 | -21.44 – 23.51 | 338.99 | 54.41 | -37.59 – 146.41 |

| Celecoxib | 164.58 | -13.54 | -35.92 – 8.84 | 409.22 | -15.82 | -102.31 – 70.67 |

Adjusted for the following baseline factors: age, gender, BMI class, pain, Kellgren & Lawrence grade as well as time in study, time squared using GEE. A 95% confidence interval (CI) excluding 0 indicates a significant difference from the placebo group.

In the original GAIT report, a subset of participants with more severe baseline pain appeared to benefit by use of the combination of glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate. This question was examined in the present study by including interactions between severe pain and treatment group; none of these interactions was statistically significant.

Safety

Adverse events (AEs) were reported as the percentage of patients who reported the adverse event at least once during follow-up. They were characterized according to standard FDA reporting language as AEs or SAEs.[10] AEs statistically divergent from placebo were mild, showed no important differences and were evenly distributed among treatment groups. There were 84 SAEs occurring in 64 patients, of which 5 were felt to be possibly related to the study medications. These included myocardial infarction (in a patient receiving the glucosamine/chondroitin sulfate combination, hereafter referred to as “combination”), coronary angioplasty (in placebo group), and hip arthroplasty, cerebrovascular accident and abdominal wall abscess (all receiving celecoxib). Other SAEs reported regardless of relatedness are one death, which occurred as a completed suicide (placebo group), two myocardial infarctions (one glucosamine, one combination), two cerebrovascular accidents (one glucosamine, one celecoxib), two hypertension (one combination, one placebo), one case with palpitations (combination), and one transient ischemic attack (combination). There were no serious adverse gastrointestinal bleeding events reported.

Compliance was evaluated by pill counts at each visit. While patients continued in the trial, the percentage of prescribed medication taken was 90%. The use of rescue acetaminophen averaged 570 mg daily. The lowest use was in the celecoxib (465 mg) group and the highest use in the placebo group (645 mg). Interestingly, the rank order of rescue medication use (least to greatest) exactly paralleled that of the primary efficacy outcome for this study.

Discussion

Literature examining the use of the dietary supplements, especially glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate, to treat osteoarthritis has increased substantially over the last five years. Reviews describe their effects on symptoms [13-15] and to a lesser extent on structural modification.[7, 16, 17] Unfortunately, the duration of most of the symptomatic studies is relatively short, especially when compared to the duration of use expected for these agents in patients affected by OA of the knee. Systematically collected data on safety of these agents are also limited by short study durations as well. The prior report from GAIT examined the primary outcome in the overall study population of 1583 patients at 24 weeks.[6] This report describes the efficacy and safety over two years of exposure to the therapies.

The patients reported in this two-year cohort from GAIT are, as would be expected of OA patients in general, predominantly female, overweight and over 45 years of age. As shown in Table 3, improvement in pain and function over 24 months was observed in all groups, and no therapy was statistically superior to placebo. However, patients treated with celecoxib and with glucosamine monotherapy had the greatest improvement. Table 2 shows an improved sensitivity to change relative to placebo for the OMERACT/OARSI outcome measure as compared to a 20% reduction in WOMAC Pain score. Overall our results are in agreement with the Cochrane review of glucosamine, which found glucosamine ineffective for treatment of pain in studies that used a WOMAC Pain outcome.[15] Interestingly, in the Cochrane analysis, studies which used the Lequesne index as an outcome measure showed glucosamine sulfate to be superior to placebo. Two trials, including the parent to this study (GAIT), reported that use of glucosamine hydrochloride, did not show a benefit compared to placebo.[6, 18] While meta-analyses have supported benefit for OA pain from use of chondroitin sulfate [19, 20], we did not see evidence for such a benefit. A protocol for a Cochrane review of chondroitin sulfate for OA has been defined, but a completed analysis has not been reported.

Remarkably few published reports of efficacy data exist in OA of the knee beyond six months duration. Those studies that are published typically use patient global pain measures rather than validated composite indexes. For example, naproxen was shown equal to diclofenac for 26 weeks based on continuation of use and patient reports of pain at rest [21], while two year data for naproxen using a 5 point Likert scale showed it to be statistically similar to acetaminophen.[22] Sustained release diclofenac was also studied for two years and shown similar to placebo as assessed by patient report on a 5 point Likert scale.[23] Use of celecoxib to treat OA for one year has been reported. [24] Celecoxib has demonstrated efficacy as compared to placebo at 12 weeks as a mean reduction in WOMAC pain score [25], and was effective at 24 weeks in the primary GAIT study.[6] The ancillary study reported here suggests a waning of benefit with longer usage like has been described for NSAIDs in general.

AEs were mild and occurred in all groups over the two-year period. Only five SAEs were thought to be related to study agents. While there were concerns that glucosamine might exacerbate diabetes or asthma, three-year studies from Europe and these data do not substantiate those concerns.[26, 27] A two-year study with safety data for celecoxib comes from a trial on prevention of adenomatous polyps. [26] Another longer-term study of celecoxib use was in ankylosing spondylitis (one year).[27] Reports of the relative safety of celecoxib are supported by our findings, which show no difference from the safety profile of placebo. While the number of participants using celecoxib in this study is modest, it is noteworthy that no adverse events related to gastrointestinal bleeding were reported and no difference in cardiovascular events as compared to use of placebo was demonstrated.

Perhaps the most interesting finding is the pronounced and persistent clinical improvement shown in Figure 1, which shows an improved WOMAC Pain and WOMAC Function score for all treatment groups, including placebo. The improvement is seen early and persists throughout the two-year study period. This response cannot easily be dismissed as regression to the mean as it persists throughout the entire 24-month duration of follow-up. Patients in flare studies may demonstrate regression toward the mean, but this study did not require flare criteria for entry, and patients did not systematically discontinue medications prior to entry. If the agents indeed had therapeutic benefit to account for the change, then the placebo group's improvement is difficult to explain, as it is identical to the other arms. While a benefit of being closely followed by a study team is reported, it is not typically of this magnitude or of this extended duration.

In another two year study in OA evaluating risedronate as a possible structure modifying agent in OA, there was a very similar benefit demonstrated in all treatment groups as well as in the placebo group, which was detected at the first efficacy time point at six months, and persistent through the two years of the study.[28] Risedronate decreases biochemical markers of cartilage degradation, but does not decrease symptoms or slow radiographic progression in patients with medial compartment OA of the knee.[29] While the study allowed patients to take background analgesics, all patients were required to discontinue NSAIDs and analgesics in a proscribed manner prior to all clinical assessments to allow for a possible flare to better detect a treatment effect of the study medications. While in this study regression to the mean is a possibility, baseline levels of pain were also low (mean WOMAC pain 42.4), making it more difficult to detect a treatment effect due to a floor effect of the outcome measurement. Also, a significant expectation bias on the part of participants as reflected in the very high completion rate at two years (76.4%) might have contributed.

As evidenced by both of these longer-term studies demonstrating similarly sustained placebo benefits, further evaluation of the factors involved is warranted and will be important in designing future OA trials. The current study is limited by its design as an ancillary preplanned continuation of a randomized controlled trial in which all of the initially randomized patients were not eligible to participate. There was significant dropout manifested as discontinuation of medication use as well as missed assessments. Recognizing that selective dropout can bias study findings, specific analytical methods were applied to mitigate this problem.

In conclusion, findings from this study provide important longer-term safety information on the use of glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate given alone or in combination and the use of celecoxib in a two-year placebo-controlled trial for treatment of OA of the knee. All of the tested therapies appeared to be generally safe and well tolerated over a two-year period. A clinically detectable symptomatic benefit was seen as early as 24 weeks in all groups, including placebo, and was sustained over two years of study. Although none of the agents were statistically superior to placebo, celecoxib and glucosamine gave the highest odds of benefit for improved pain and function, but with widely overlapping confidence intervals for all treatments.

What is Already Known

It is already known that successful longer-term medical treatment of asteoarthritis (OA) of the knee is limited.

It is estimated that only 15-20% will continue to receive a given non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug after 1 year of use, because of a combination of loss of efficacy and/or accumulated toxicities.

Relatively long-term efficacy and safety data for glucosamine and chonroitinsulfate alone, and especially in combination, are also limited.

What this Study ADDS?

This study adds long-term data to the efficacy and safety data not only for the nutraceuticals but also for the coxib-celecoxib.

All data were obtained using dosages typically used to treat OA of the knee and gathered prospectively.

Only one other report of celecoxib use in OA of greater than 1-years duration has been reported.

Acknowledgments

Acknowlegements and Affiliations: The authors gratefully acknowledge statistical advice from Dr Donald Hedeker, University of Illinois.

Funding: Supported by NIH (National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases and National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Contract N01-AR-2236

References

- 1.Simon LS. Osteoarthritis: a review. Clin Cornerstone. 1999;2(2):26–37. doi: 10.1016/s1098-3597(99)90012-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gregory PJ, Sperry M, Wilson AF. Dietary supplements for osteoarthritis. Am Fam Physician. 2008 Jan 15;77(2):177–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamath CC, Kremers HM, Vanness DJ, O'Fallon WM, Cabanela RL, Gabriel SE. The cost-effectiveness of acetaminophen, NSAIDs, and selective COX-2 inhibitors in the treatment of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Value Health. 2003 Mar-Apr;6(2):144–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4733.2003.00215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki G, Abramson S, Altman RD, Arden N, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, Part II: OARSI evidence-based, expert consensus guidelines. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008 Feb;16(2):137–62. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rostom A, Muir K, Dube C, Jolicoeur E, Boucher M, Joyce J, et al. Gastrointestinal safety of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors: a Cochrane Collaboration systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007 Jul;5(7):818–28. 28 e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.03.011. quiz 768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clegg DO, Reda DJ, Harris CL, Klein MA, O'Dell JR, Hooper MM, et al. Glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, and the two in combination for painful knee osteoarthritis. N Engl J Med. 2006 Feb 23;354(8):795–808. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sawitzke AD, Shi H, Finco MF, Dunlop DD, Bingham CO, 3rd, Harris CL, et al. The effect of glucosamine and/or chondroitin sulfate on the progression of knee osteoarthritis: A report from the glucosamine/chondroitin arthritis intervention trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2008 Oct;58(10):3183–91. doi: 10.1002/art.23973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bellamy N. Pain assessment in osteoarthritis: experience with the WOMAC osteoarthritis index. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1989 May;18(4 Suppl 2):14–7. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(89)90010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pham T, van der Heijde D, Altman RD, Anderson JJ, Bellamy N, Hochberg M, et al. OMERACT-OARSI initiative: Osteoarthritis Research Society International set of responder criteria for osteoarthritis clinical trials revisited. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004 May;12(5):389–99. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Expert working group (efficacy) of the international conference on harmonization of technical requirements for registration of pharmaceuticals for human use. FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hochberg Y, Tamhane AC. Multiple comparison procedures. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hogan JW, Roy J, Korkontzelou C. Handling drop-out in longitudinal studies. Stat Med. 2004 May 15;23(9):1455–97. doi: 10.1002/sim.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bruyere O, Reginster JY. Glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate as therapeutic agents for knee and hip osteoarthritis. Drugs Aging. 2007;24(7):573–80. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200724070-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bennett AN, Crossley KM, Brukner PD, Hinman RS. Predictors of symptomatic response to glucosamine in knee osteoarthritis: an exploratory study. Br J Sports Med. 2007 Jul;41(7):415–9. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.033381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Towheed TE, Maxwell L, Anastassiades TP, Shea B, Houpt J, Robinson V, et al. Glucosamine therapy for treating osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(2):CD002946. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002946.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poolsup N, Suthisisang C, Channark P, Kittikulsuth W. Glucosamine long-term treatment and the progression of knee osteoarthritis: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Ann Pharmacother. 2005 Jun;39(6):1080–7. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reginster JY, Bruyere O, Henrotin Y. New perspectives in the management of osteoarthritis. structure modification: facts or fantasy? J Rheumatol Suppl. 2003 Aug;67:14–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Houpt JB, McMillan R, Wein C, Paget-Dellio SD. Effect of glucosamine hydrochloride in the treatment of pain of osteoarthritis of the knee. J Rheumatol. 1999 Nov;26(11):2423–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leeb BF, Schweitzer H, Montag K, Smolen JS. A metaanalysis of chondroitin sulfate in the treatment of osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2000 Jan;27(1):205–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richy F, Bruyere O, Ethgen O, Cucherat M, Henrotin Y, Reginster JY. Structural and symptomatic efficacy of glucosamine and chondroitin in knee osteoarthritis: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2003 Jul 14;163(13):1514–22. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.13.1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scharf Y, Nahir M, Schapira D, Lorber M. A comparative study of naproxen with diclofenac sodium in osteoarthrosis of the knees. Rheumatol Rehabil. 1982 Aug;21(3):167–70. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/21.3.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams HJ, Ward JR, Egger MJ, Neuner R, Brooks RH, Clegg DO, et al. Comparison of naproxen and acetaminophen in a two-year study of treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Rheum. 1993 Sep;36(9):1196–206. doi: 10.1002/art.1780360904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dieppe P, Cushnaghan J, Jasani MK, McCrae F, Watt I. A two-year, placebo-controlled trail of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory therapy in osteoarthritis of the knee joint. Br J Rheumatol. 1993 Jul;32(7):595–600. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/32.7.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fleischmann R, Tannenbaum H, Patel NP, Notter M, Sallstig P, Reginster JY. Long-term retention on treatment with lumiracoxib 100 mg once or twice daily compared with celecoxib 200 mg once daily: a randomised controlled trial in patients with osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:32. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-9-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bensen WG, Fiechtner JJ, McMillen JI, Zhao WW, Yu SS, Woods EM, et al. Treatment of osteoarthritis with celecoxib, a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor: a randomized controlled trial. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999 Nov;74(11):1095–105. doi: 10.4065/74.11.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solomon SD, Pfeffer MA, McMurray JJ, Fowler R, Finn P, Levin B, et al. Effect of celecoxib on cardiovascular events and blood pressure in two trials for the prevention of colorectal adenomas. Circulation. 2006 Sep 5;114(10):1028–35. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.636746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poddubnyy DA, Song IH, Sieper J. The safety of celecoxib in ankylosing spondylitis treatment. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2008 Jul;7(4):401–9. doi: 10.1517/14740338.7.4.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buckland-Wright JC, Messent EA, Bingham CO, 3rd, Ward RJ, Tonkin C. A 2 yr longitudinal radiographic study examining the effect of a bisphosphonate (risedronate) upon subchondral bone loss in osteoarthritic knee patients. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007 Feb;46(2):257–64. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bingham CO, 3rd, Buckland-Wright JC, Garnero P, Cohen SB, Dougados M, Adami S, et al. Risedronate decreases biochemical markers of cartilage degradation but does not decrease symptoms or slow radiographic progression in patients with medial compartment osteoarthritis of the knee: results of the two-year multinational knee osteoarthritis structural arthritis study. Arthritis Rheum. 2006 Nov;54(11):3494–507. doi: 10.1002/art.22160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]