Abstract

Fibrillarin is a phylogenetically conserved protein essential for efficient processing of pre-rRNA through its association with a class of small nucleolar RNAs during ribosomal biogenesis. The protein is the antigen for the autoimmune disease scleroderma. Here we report the crystal structure of the fibrillarin homologue from Methanococcus jannaschii, a hyperthermophile, at 1.6 Å resolution. The structure consists of two domains, with a novel fold in the N-terminal region and a methyltransferase-like domain in the C-terminal region. Mapping temperature-sensitive mutations found in yeast fibrillarin Nop1 to the Methanococcus homologue structure reveals that many of the mutations cluster in the core of the methyltransferase-like domain.

Keywords: crystal structure/fibrillarin/ribosome biogenesis/rRNA methylation/snoRNA

Introduction

Fibrillarin homologues have been isolated in a number of eukaryotes and archaebacteria, including Methanococcus jannaschii (Christensen et al., 1977; Ochs et al., 1985; Schimmang et al., 1989; Lapeyre et al., 1990; Aris and Blobel, 1991; Turley et al., 1993; Amiri, 1994; Bult et al., 1996; David et al., 1997; Narcisi et al., 1998). Immunological cross-reactivity and functional complementarity among fibrillarin homologues demonstrate that these proteins have a high degree of conservation over a wide phylogenetic range (Lapeyre et al., 1990; Aris and Blobel, 1991; Jansen et al., 1991; Amiri, 1994; David et al., 1997). Eukaryotic fibrillarins are longer than the Methanococcus homologues and have the extra glycine–arginine-rich (GAR) domain that is implicated in localizing fibrillarins in the nucleolus (Amiri, 1994; Bult et al., 1996). However, the remaining region is homologous to Methanococcus protein, with a sequence identity of ∼40%.

Fibrillarin is the most abundant protein in the fibrillar regions of the eukaryotic cell nucleolus where early stages of pre-rRNA processing take place (Warner, 1990; Eichler and Craig, 1994). In humans, it is the nucleolar autoantigen for the non-hereditary immune disease scleroderma (Aris and Blobel, 1991). Fibrillarin is also a common protein component in many small nucleolar ribonucleoprotein (snoRNP) particles (Maxwell and Fournier, 1995). During rRNA maturation, snoRNPs mediate post-transcriptional activities such as cleavage of the primary pre-rRNA transcripts, nucleotide modifications and assembly of ribosomal proteins and rRNAs into ribosomal subunits (Eichler and Craig, 1994; Maxwell and Fournier, 1995). Each snoRNP particle contains both a small nucleolar RNA (snoRNA), ranging in size from 70 to 600 nucleotides, and a set of associated nucleolar proteins, including fibrillarin (Eichler and Craig, 1994; Maxwell and Fournier, 1995). In vertebrates, all fibrillarin-associated snoRNA molecules contain consensus sequence elements called C (5′-UGAUGA-3′) and D (5′-CUGA-3′) boxes (reviewed in Sollner-Webb, 1993; Smith and Steitz, 1997). A majority of fibrillarin-associated box C/D snoRNAs function in rRNA methylation. These antisense snoRNAs function as guides for rRNA 2′-O-methylation through RNA duplex formation over the methylation site. The methylation occurs at the base complementary to the fifth nucleotide upstream from the consensus D box sequence (Cavaille et al., 1996; Kiss-Laszlo et al., 1996).

Although the biochemical function of fibrillarin is not completely understood, a number of temperature-sensitive fibrillarin mutants have been isolated in yeast that affect all post-transcriptional activities in rRNA maturation (Tollervey et al., 1991, 1993). Similar phenotypes can be found in alleles encoding proteins that physically interact with fibrillarin (Gautier et al., 1997). Thus, fibrillarin appears to be a key component in the snoRNPs required for pre-rRNA processing, either through direct mediation or by acting as an accessory protein in a larger supramolecular complex. To investigate the role of fibrillarin in snoRNPs during ribosome maturation, we determined the crystal structure of the fibrillarin homologue of Methanococcus jannaschii (Mj0697) and correlated the Mj0697 structure with existing data on other fibrillarin homologues.

Results

Overall structure and topology

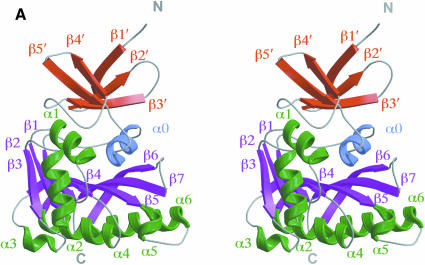

Mj0697 has a globular two-domain structure with overall dimensions of ∼50 × 35 × 35 Å (Figure 1A). Composed of a total of seven α-helices and 12 β-strands, it is divided into a smaller N-terminal domain (residues 1–54) and a larger C-terminal domain (residues 55–230). The N-terminal domain represents a novel fold, forming a crescent-shaped arrangement consisting of five β-strands. The C-terminal domain, which is connected to the N-terminal domain by a short helix (residues 57–64), has a mixed α/β structure with alternating α-helices and β-strands. The core of this C-terminal domain is a seven-stranded β-sheet (β1–β7), flanked by three α-helices on one side (α0, α1 and α2) and four α-helices on the other (α3, α4, α5 and α6) (Figure 1A). The strands of the β-sheet are arranged in the order 3–2–1–4–5–7–6, and all strands, except for the seventh strand, are in parallel orientation (Figure 1C).

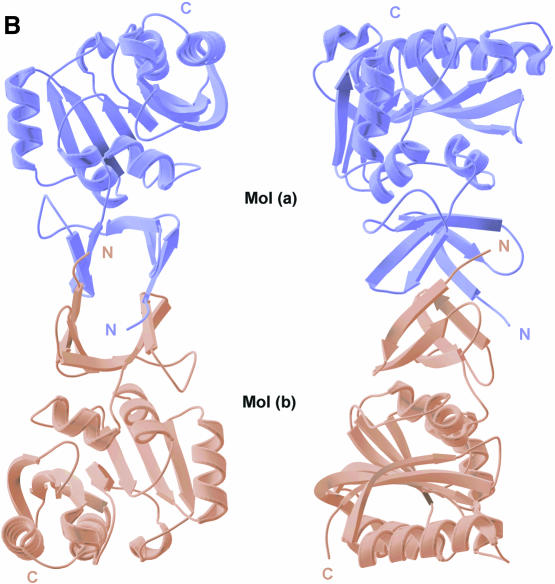

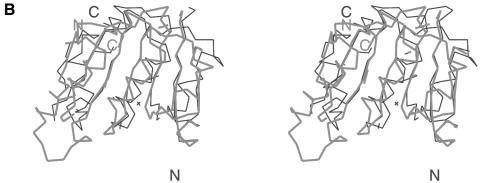

Fig. 1. (A)Ribbon diagram of the Mj0697 monomer. The β-strands in the C-terminal domain (β1–β7) and in the N-terminal domain (β1′–β5′) are shown in magenta and red, respectively, while the α-helices (α1–α6) are shown in green and the connecting helix (α0) in blue. The secondary structure elements were assigned using PROCHECK (Laskowski et al., 1993). The ribbon representation was generated using MOLSCRIPT (Kraulis, 1991). (B)Ribbon diagram of the Mj0697 dimer viewed from two angles, differing by rotations of ∼90° on the vertical axis. (C)Topological diagram of the Mj0697 dimer. Helices are represented as cylinders and β-sheets as arrows.

In the crystal, two N-terminal domains join to form a homodimer related by a crystallographic 2-fold axis (Figure 1B and C). The dimer interface is a β-barrel of 10 β-strands, with a hollow centre ∼5 Å in diameter, and composed of β-strands from each monomer (Figure 1B). The buried surface area at the dimer interface is ∼1700 Å2. Native gel electrophoresis indicated that Mj0697 dimerizes in solution (data not shown), suggesting that the interdomain sheet observed in the crystal may be a functional molecular interface.

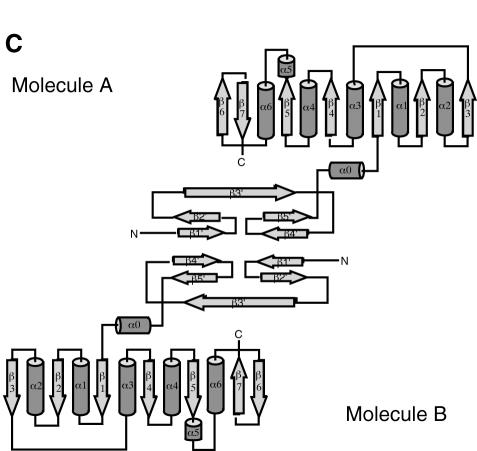

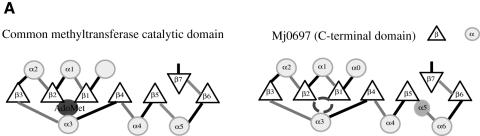

Despite the absence of any significant sequence similarities, the overall fold of the C-terminal domain is similar to the catalytic domain common to many S-adenosyl-l-methionine (AdoMet)-dependent methyltransferases, such as several DNA methyltransferases, including: HhaI (Cheng et al., 1993; Klimasauskas et al., 1994), TaqI (Labahn et al., 1994), HaeIII (Reinisch et al., 1995) and PvuII (Gong et al., 1997); a few small molecule methyltransferases, such as catechol O-methyltransferase (COMT) (Vidgren et al., 1994) and GNMT (Fu et al., 1996); two RNA methyltransferases, VP39 (Hodel et al., 1996) and ErmC′ (Bussiere et al., 1998); and one protein methyltransferase, CheR (Djordjevic and Stock, 1997). The consensus topology for the methyltransferase catalytic domain is a seven-stranded β-sheet flanked by three α–helices on each side of the sheet (Figure 2A). The C–terminal domain of Mj0697 differs from the methyltransferase consensus topology only by the addition of a minihelix (α5). Similarly to methyltransferases, a Rossmann fold is formed in Mj0697 by the first three β–strands (β1, β2 and β3) and the two helices that lie above the surface of the β-sheet closest to the N-terminal domain (designated α1 and α2) (Eklund et al., 1981).

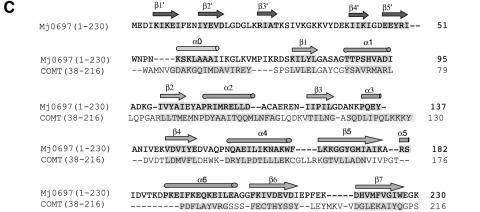

Fig. 2. (A) A comparison of the topological representations of the C-terminal domain of Mj0697 and the consensus catalytic domain derived from other methyltransferases (Vidgren et al., 1994; Schluckebier et al., 1995; Djordjevic and Stock, 1997). Helices are shown as circles, β-strands as triangles. The AdoMet-binding pocket is indicated. The location of the analogous pocket is indicated by an empty circle in the Mj0697 scheme. An extra helix present in the Methanococcus homologue that does not occur in the consensus domain is shaded darker. (B) Superposition of the Cα traces of the C–terminal domain in Mj0697 (black line), and of the methyltransferase catalytic domain in catechol O-methyltransferase, COMT (grey line). The diagram was prepared using INSIGHTII (Molecular Systems Inc.). (C) Structural-based sequence alignment of Mj0697 and COMT.

Comparison of the C-terminal domain with methyltransferases

Alignment of the Cα positions of the C-terminal domain of Mj0697 with the catalytic domain of the methyltransferases shows that the backbone configurations are almost identical. The root-mean-squared deviation (r.m.s.d.) of the Cα positions of all the corresponding residues in the conserved seven-stranded β-sheet region (49 residues) between Mj0697 and these methyltransferases varies from 1.3 to 2.1 Å. Among these, Mj0697 is most similar to COMT (PDB accession number 1VID) with an r.m.s.d. of 1.3 Å. Three-dimensional superposition of Mj0697 and 1VID is shown as a stereo view of the Cα trace in Figure 2B. A structure-based sequence alignment of Mj0697 and 1VID is shown in Figure 2C.

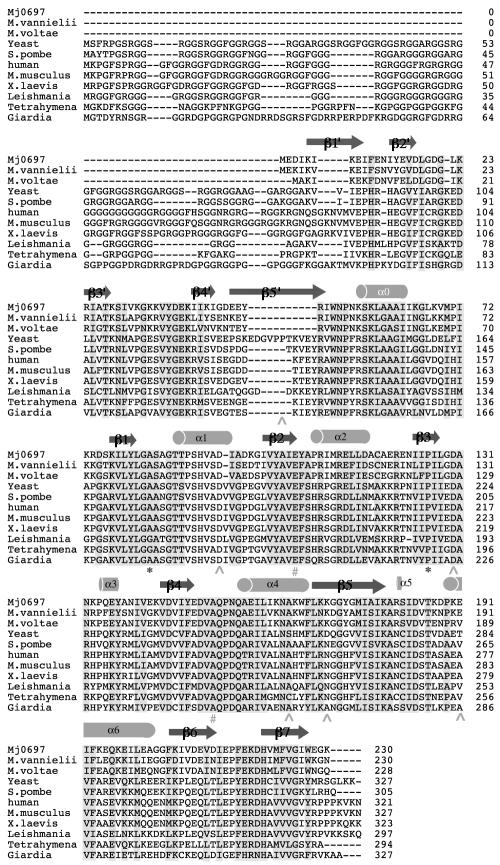

Sequence motifs characteristic of AdoMet-dependent methyltransferases can also be identified in this domain of Mj0697. These motifs are present in all fibrillarin homologues (Figure 3). In Mj0697, a majority of them are located around a small pocket at the C-terminal ends of the parallel β-strands (β1–β4) as seen in other methyltransferases. These include a loop between α1 and β1 corresponding to GASAG (82–86), an acidic residue at the end of β2 (E105) and a small residue juxtaposed with this acidic residue at the end of β1 (G82). In all methyltransferases, these motifs are important for AdoMet interactions.

Fig. 3. Amino acid sequence alignment of the fibrillarin homologues. The alignment was performed using CLUSTAL W (Thompson et al., 1994). The secondary structural elements are labelled. Shaded residues are conserved residues, including identical, conserved substitutions and semi-conserved substitutions. The yeast fibrillarin mutants shown include: Nop 1.3 mutants blocking rRNA methylation (*); Nop 1.5 and Nop 1.2 mutants affecting rRNA cleavage (∧); and Nop 1.7 mutants affecting rRNA assembly (#).

Discussion

Even though Mj0697 has no significant sequence homology with previously identified methyltransferases (aligned using the BLAST program against GenBank), the C-terminal domain of the molecule is structurally homologous to the catalytic domains found in many methyltransferases (Altschul et al., 1997). Among the fibrillarin homologues, however, this domain is conserved even at the primary amino acid sequence level. BLAST alignment shows that Mj0697 is 56–64% identical and 78–80% similar to vertebrate fibrillarins between residues 25 and 95 (containing the α1–β1 loop). Even in the less similar regions outside this segment (residues 95–227), it is 37–40% identical, with a similarity of 65–69%. Such high sequence identity among fibrillarin homologues suggests that they all contain a methyltransferase folding domain.

A short consensus amino acid sequence, ‘S-adenosyl-l-methionine-binding motif’, was used to predict fibrillarin's function as a putative methyltransferase. This sequence has been located in our structure (Ingrosso et al., 1989; Koonin, 1993; Koonin et al., 1995). As predicted by Koonin et al. (1995), it forms part of the central portion of the β-sheet that is conserved in all known methyltransferase structures. Our structure shows that this sequence covers the entire helix α1 and the preceding α1–β1 loop of the methyltransferase domain. This sequence motif is also present in the archaebacterial fibrillarin-like proteins from Methanococcus vannielii and Methanococcus voltae. Recently, using conserved methyltransferase motifs, Niewmierzycka and Clarke (1999) identified an AdoMet-binding domain in yeast fibrillarin Nop1.

There is a significant variance in the N-terminal domain of fibrillarin from different species. Archaebacterial homologues lack an N-terminal GAR domain that is present in the eukaryotes (Amiri, 1994). In Mj0697, the N-terminal domain is shorter and contains a novel fold that in the crystal appears to mediate the formation of a homodimer, where it forms the previously mentioned β-barrel with its symmetry-related partner. Even though this domain is likely to be present in the eukaryote versions based upon sequence homology, whether or not it mediates dimerization has not been determined.

A number of temperature-sensitive mutants that affect rRNA maturation, including rRNA methylation, have been isolated in the yeast fibrillarin homologue, Nop1 (Tollervey et al., 1993). Locations of yeast mutations are mapped on the homologous positions of the Mj0697 sequence, as shown in Table I. These mutations cluster at or in the vicinity of the small pocket at the C-terminal ends of the parallel β-strands, or are mapped to the conserved regions of the methyltransferase-like domain. Mutations that severely inhibit rRNA methylation in yeast fibrillarin include P219S and A175V. P219S corresponds to a highly conserved proline (P126 in Mj0697). The A175V mutation (corresponding to A83 in Mj0697) is located on the α1–β1 loop, where it could interfere with the AdoMet interaction.

Table I. Locations of the Nop1 mutants on the Mj0697 structure.

| Phenotype | Nop1 mutants (Tollervey et al., 1993) | Corresponding residues in Mj0697 |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-rRNA cleavage | ||

| Nop 1.2 | D186G | D94 |

| D223N | D130 | |

| D236G | K170 | |

| Nop 1.5 | K138E | – |

| S257P | A164 | |

| T284A | E191 | |

| Pre-rRNA methylation | ||

| Nop 1.3 | A175V | A83 |

| P219S | P126 | |

| Pre-rRNA assembly | ||

| Nop 1.4 | A245V | A152 |

| Nop 1.7 | E198G | E105 |

In vitro, fibrillarin associates either directly or indirectly with a large number of C/D box-containing snoRNAs. Many of these fibrillarin-associated snoRNAs direct ribose methylation by forming an RNA duplex over the methylation site (Cavaille et al., 1996; Kiss-Laszlo et al., 1996). However, the methyltransferase activity in this process has not yet been identified. The presence of a methyltransferase-like domain in fibrillarin homologues suggests that fibrillarin could be an enzyme. Direct biochemical evidence to characterize the methyltransferase activity of fibrillarin in snoRNA-guided ribose methylation may not be readily attainable. In our tests of the in vitro activity of the protein, we have been unable to obtain activity with Mj0697 alone. This is not entirely unexpected, because fibrillarin normally functions as part of the snoRNP particles (Eichler and Craig, 1994; Maxwell and Fournier, 1995), where it associates with other processing factors. It is likely that some of the latter components are required for the methylation reaction. Identification of fibrillarin-associated snoRNP components will be useful in order to understand this process.

In summary, the three-dimensional structure of fibrillarin from M.jannaschii presented here identifies a methyltransferase-like domain and a novel fold that forms the dimerization domain. The presence of the methyltransferase-like domain in fibrillarin homologues, together with the previous sequence prediction and genetic data, allows us to link fibrillarin's role in ribosome biogenesis with rRNA methylation.

Materials and methods

Expression and purification

Mj0697 was overexpressed at room temperature in Escherichia coli strain BL21(DE3) containing the expression vector pET21a (Wang et al., 1999) with the Mj0697 gene and an additional plasmid encoding rare E.coli tRNAs. Soluble Mj0697 protein was purified by heating E.coli cell lysate at 80°C for 30 min, followed by a single-column elution (Pharmacia HiTrap Q). Selenomethionine (Se-Met)-substituted protein was produced by overexpression in E.coli B834, a methionine auxotroph, and cultured in minimal media supplemented with 45 μg/ml selenomethionine.

Crystallization and data collection

The crystals of Mj0697 were grown by the vapour diffusion method from a solution containing 25 mg/ml protein, 10% PEG 4000, 10% isopropanol and 0.05 M sodium citrate pH 5.6, equilibrated against a solution containing 20% PEG 4000, 20% isopropanol and 0.1 M sodium citrate pH 5.6. The crystals are in the C2 space group with unit cell dimensions of a = 121.4 Å, b = 43.2 Å, c = 55.3 Å and β = 96.9°. Purification and crystallization of the Se-Met-substituted protein were performed under essentially the same conditions as for the native protein (Wang et al., 1999). Diffraction data for the heavy-atom derivative crystals were collected on a Rigaku R-axis IIC imaging plate system, using CuKα radiation from a Rigaku RU200 HB rotating anode operated at 40 kV and 100 mA. The data for the multiwavelength anomalous diffraction of the Se-Met crystals were collected at the National Synchrotron Light Source (NSLS), Brookhaven beamline X4A corresponding to wavelengths 0.96373, 0.97894 and 0.97921 Å.

Structure determination

X-ray diffraction data sets were processed using program packages DENZO and SCALEPACK (Otwinowski, 1993). Crystallographic statistics for X-ray diffraction data, phase calculation and model refinement are summarized in Table II. The crystals were first phased using the multiple isomorphous replacement (MIR) method. Heavy-atom derivatives were initially analysed using XTALVIEW (McRee, 1992). The CCP4 package (Collaborative Computational Project, 1994) was used for heavy-atom refinement and phase calculation. Two derivatives were used, a mercury heavy-atom derivative (mersalyl acid) and a Se-Met-substituted crystal. Each asymmetric unit was found to contain a single mercury site and five Se-Met sites employing both Patterson and cross-Fourier analysis. After solvent flattening and density modification, the resulting phases were used to calculate an electron density map, which revealed a seven-stranded β-sheet of the larger C-terminal domain. However, the quality of the map was not good enough to trace the backbone completely.

Table II. Summary of crystallographic statistics.

| MIR data collection and processing | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nativea | Mersalyl acid | Se-Met | |

| Resolution (Å) | 1.8 | 3.0 | 2.0 |

| Unique reflections | 31 292 | 5508 | 18 503 |

| Completeness (%) | 99 | 97 | 97 |

| Rsym | 6.1 | 8.7 | 7.6 |

| Heavy atom concentration (mM) | 10 | ||

| No. of sites | 1 | 5 | |

| Rcullis | 0.9 | ||

| Phasing power | 1.0 | 1.3 | |

| Figure of merit |

|

|

0.22 |

| Se-Met crystal data collection and phasing | |||

| |

λ1 |

λ2 |

λ3 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.96373 | 0.97694 | 0.97921 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 2.0 | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| Unique reflections | 19 130 | 37 155 | 37 035 |

| Completeness (%) | 97 | 97 | 97 |

| Rsym | 5.4 | 7.6 | 7.6 |

| Rcullis | 0.9 | ||

| Phasing power | 0.9 | ||

| Figure of merit |

0.22 |

|

|

| Refinement statistics | |||

| Resolution (Å) | 12–1.6 | ||

| Rworking/Rfree (%) | 22.9/24.7 | ||

| Reflections (working/test) | 35 943/36 45 | ||

| Atoms modelled (no. of protein residues/water) | 230/185 | ||

| R.m.s.d. bond length (Å) | 0.007 | ||

| R.m.s.d. bond angles (°) | 1.31 | ||

| R.m.s.d. B-factor (Å2) | 2.26 | ||

Rsym = 100 (ΣhklΣi |Ii – <I>|)/(ΣhklΣiIi), where Ii is the intensity of the ith measurement and <I> is the weighted mean of all measurements of I.

Phasing power = Σ|Fh|/Σ||Fph(obs)| – |Fph(calc)||

Rcullis = Σ||Fph(obs) – Fp(obs)| – Fh(calc)|/Σ|Fph(obs) – Fp(obs)||

Rworking = Σ|Fobs – Fcalc|/Σ|Fobs|

Rfree was calculated using 10% of the reflection data.

aData were collected at SSRL beamline 5-1.

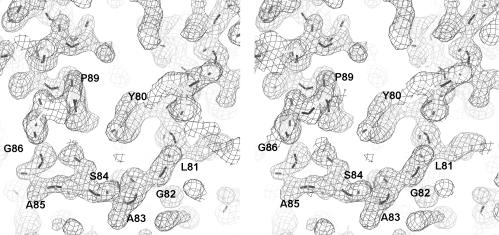

Subsequently, a second Se-Met data set was collected at the three wavelengths close to the selenium absorption edge at NSLS beamline X4A. This multiwavelength anomalous diffraction data set was treated as a special case of MIR (Ramakrishnan and Biou, 1997). Using HEAVY (Terwilliger et al., 1987), positions were verified for the five selenium atom sites, resulting in close agreement with those previously obtained by MIR. MLPHARE (CCP4) was used for heavy-atom position refinement and phase calculation. The phase was calculated utilizing data collected from the wavelength corresponding to the maximum anomalous signal as the heavy-atom derivative data set, and the data at a remote wavelength from the selenium absorption edge as the native data set. After solvent flattening and density modification, an experimental electron density map was calculated with the CCP4 package using data between 15 and 2.0 Å. The resulting map was of sufficient quality to identify most regions of the molecule, with the exception of several loop regions (Figure 4).

Fig. 4. Stereo diagram of the electron density map of the α1–β1 loop (82–86) region in the Mj0697 structure. The solvent-flattened experimental electron density map was contoured at 1.5σ, superimposed with the current model. This diagram was generated using the program O (Jones et al., 1991).

Model building and refinement

The initial chain tracing and all subsequent model building were performed using O (Jones et al., 1991). Crystallographic refinement was performed using X-PLOR (Brünger, 1992a) with cycles of bulk solvent correction, energy minimization and simulated annealing. The model was refined against 90% of the data set with the maximum anomalous signal, while 10% was used to calculate the free R-factor (Brünger, 1992b). At later stages of refinement, the X-PLOR-refined model was also refined using the program CNS (Brünger et al., 1998). After the free R-factor was reduced to 26% and the R-factor was reduced to 23%, 185 water molecules were identified from the refined electron densities in the Fo – Fc map. The final model was refined to 1.6 Å resolution with an R-value of 22% and a free R-value of 24%, and includes all the residues of Mj0697 (Table II). None of the amino acid residues lie within the disallowed regions of a Ramachandran plot (Laskowski et al., 1993). The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession code 1FBN.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Hisao Yokota for cloning the Mj0697 gene, Jaru Jancraik and Edward Berry for discussions, and Craig Ogata of National Synchrotron Light Source of Brookhaven National Laboratory and Thomas Earnest of Advance Light Source of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory for their help with data collection. We gratefully acknowledge the support of the Office of Biological and Environmental Research, the Office of Science, DOE (to R.K. and S.-H.K.; DE-AC03-76SF00098).

References

- Altschul S.F., Madden, T.L., Schaffer, A.A., Zhang, J., Zhang, Z., Miller, W. and Lipman, D.J. (1997) Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amiri K.A. (1994) Fibrillarin-like proteins occur in the domain Archaea. J. Bacteriol., 176, 2124–2127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aris J.P. and Blobel, G. (1991) cDNA cloning and sequencing of human fibrillarin, a conserved nucleolar protein recognized by autoimmune antisera. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 88, 931–935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brünger A.T. (1992a) X-PLOR Version 3.1. A System for Crystallography and NMR. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT. [Google Scholar]

- Brünger A.T. (1992b) The free R value: a novel statistical quantity for assessing the accuracy of crystal structures. Nature, 335, 472–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brünger A.T. et al. (1998) Crystallography and NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D, 54, 905–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bult C.J. et al. (1996) Complete genome sequence of the methanogenic archaeon, Methanococcus jannaschii. Science, 273, 1058–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussiere D.E. et al. (1998) Crystal structure of ErmC′, an rRNA methyltransferase which mediates antibiotic resistance in bacteria. Biochemistry, 37, 7103–7112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavaille J., Nicoloso, M. and Bachellerie, J.P. (1996) Targeted ribose methylation of RNA in vivo directed by tailored antisense RNA guides. Nature, 383, 732–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X.D., Kumar, S., Posfai, J., Pflugrath, J.W. and Roberts, R.J. (1993) Crystal structure of the HhaI DNA methyltransferase complexed with S-adenosyl-l-methionine. Cell, 74, 299–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen M.E., Beyer, A.L., Walker, B. and Lestourgeon, W.M. (1977) Identification of NG, NG-dimethylarginine in a nuclear protein from the lower eukaryote Physarum polycephalum homologous to the major proteins of mammalian 40S ribonucleoprotein particles. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 74, 621–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collaborative Computational Project (1994) The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. [DOI] [PubMed]

- David E., McNeil, J.B., Basile, V. and Pearlman, R.E. (1997) An unusual fibrillarin gene and protein: structure and functional implications. Mol. Biol. Cell, 8, 1051–1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djordjevic S. and Stock, A.M. (1997) Crystal structure of the chemotaxis receptor methyltransferase CheR suggests a conserved structural motif for binding S-adenosylmethionine. Structure, 5, 545–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichler D.C. and Craig, N. (1994) Processing of eukaryotic ribosomal RNA. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol., 49, 197–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eklund H. et al. (1981) Structure of a triclinic ternary complex of horse liver alcohol dehydrogenase at 2.9 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol., 146, 561–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Z.J. et al. (1996) Crystal structure of glycine N-methyltransferase from rat liver. Biochemistry, 35, 11985–11993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautier T., Berges, T., Tollervey, D. and Hurt, E. (1997) Nucleolar KKE/D repeat proteins Nop56p and Nop58p interact with Nop1p and are required for ribosome biogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol., 17, 7088–7098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong W.M., Ogara, M., Blumenthal, R.M. and Cheng, X.D. (1997) Structure of PvuII DNA (cytosine N4) methyltransferase, an example of domain permutation and protein fold assignment. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 2702–2715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodel A.E., Gershon, P.D., Shi, X.N. and Quiocho, F.A. (1996) The 1.85 Å structure of vaccinia protein VP39—a bifunctional enzyme that participates in the modification of both mRNA ends. Cell, 85, 247–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingrosso D., Fowler, A.V., Bleibaum, J. and Clarke, S. (1989) Sequence of the d-aspartyl/l-isoaspartyl protein methyltransferase from human erythrocytes. Common sequence motifs for protein, DNA, RNA and small molecule S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferases. J. Biol. Chem., 264, 20131–20139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen R.P. et al. (1991) Evolutionary conservation of the human nucleolar protein fibrillarin and its functional expression in yeast. J. Cell Biol., 113, 715–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones T.A., Zou, J.-Y., Cowan, S.W. and Kjeldgaard, M. (1991) Improved methods for building protein models electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr. A, 47, 110–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss-Laszlo Z., Henry, Y., Bachellerie, J.P., Caizergues-Ferrer, M. and Kiss, T. (1996) Site-specific ribose methylation of preribosomal RNA: a novel function for small nucleolar RNAs. Cell, 85, 1077–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimasauskas S., Kumar,S., Roberts,R.J. and Cheng,X. (1994) HhaI methyltransferase flips its target base out of the DNA helix. Cell, 76, 357–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koonin E.V. (1993) Computer-assisted identification of a putative methyltransferase domain in NS5 protein of flaviviruses and lambda 2 protein of reovirus. J. Gen. Virol., 74, 733–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koonin E.V., Tatusov, R.L. and Rudd, K.E. (1995) Sequence similarity analysis of Escherichia coli proteins: functional and evolutionary implications. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 92, 11921–11925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraulis P.J. (1991) MOLSCRIPT: a program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr., 24, 946–950. [Google Scholar]

- Labahn J. et al. (1994) Three-dimensional structure of the adenine-specific DNA methyltransferase TaqI in complex with the cofactor S-adenosylmethionine. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 10957–10961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapeyre B. et al. (1990) Molecular cloning of Xenopus fibrillarin, a conserved U3 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein recognized by antisera from humans with autoimmune disease. Mol. Cell. Biol., 10, 430–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski R.A., MacArthur, M.W., Moss, D.S. and Thornton, J.M. (1993) PROCHECK—a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr., 26, 283–291. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell E.S. and Fournier, M.J. (1995) The small nucleolar RNAs. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 64, 897–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRee D.E. (1992) A visual protein crystallographic software system for X11/XView. J. Mol. Graph., 10, 44–46. [Google Scholar]

- Narcisi E.M., Glover, C.V.C. and Fechheimer, M. (1998) Fibrillarin, a conserved pre-ribosomal RNA processing protein of Giardia. Eur. J. Microbiol., 45, 105–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niewmierzycka A. and Clarke,S. (1999) S-Adenosylmethionine-dependent methylation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Identification of a novel protein arginine methyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 814–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochs R.L., Lischwe, M.A., Spohn, W.H. and Busch, H. (1985) Fibrillarin: a new protein of the nucleolus identified by autoimmune sera. Biol. Cell, 54, 123–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z. (1993) In Sawyer,L., Isaacs,N. and Bailey,S. (eds), Proceedings of the CCP4 Study Weekend: ‘Data Collection and Processing’. SERC Daresbury Laboratory, UK, pp. 56–62. [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnan V. and Biou, V. (1997) Treatment of multiwavelength anomalous diffraction data as a special case of multiple isomorphous replacement. Methods Enzymol., 276, 538–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinisch K.M., Chen, L., Verdine, G.L. and Lipscomb, W.N. (1995) The crystal structure of HaeIII methyltransferase covalently complexed to DNA—an extrahelical cytosine and rearranged base pairing. Cell, 82, 143–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schimmang T., Tollervey, D., Kern, H., Frank, R. and Hurt, E.C. (1989) A yeast nucleolar protein related to mammalian fibrillarin is associated with small nucleolar RNA and is essential for viability. EMBO J., 8, 4015–4024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schluckebier G., O'Gara, M., Saenger, W. and Cheng, X. (1995) Universal catalytic domain structure of AdoMet-dependent methyltransferases. J. Mol. Biol., 247, 16–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C.M. and Steitz, J.A. (1997) Sno storm in the nucleolus: new roles for myriad small RNPs. Cell, 89, 669–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sollner-Webb B. (1993) Novel intron-encoded small nucleolar RNAs. Cell, 75, 403–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwilliger T.C., Kim, S.-H. and Eisenberg, D. (1987) Generalized method of determining heavy-atom positions using the difference Patterson function. Acta Crystallogr. A, 43, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J.D., Higgins, D.G. and Gibson, T.J. (1994) CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res., 22, 4673–4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tollervey D., Lehtonen, H., Carmo-Fonseca, M. and Hurt, E.C. (1991) The small nucleolar RNP protein NOP1 (fibrillarin) is required for pre-rRNA processing in yeast. EMBO J., 10, 573–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tollervey D., Lehtonen, H., Jansen, R., Kern, H. and Hurt, E.C. (1993) Temperature-sensitive mutations demonstrate roles for yeast fibrillarin in pre-rRNA processing, pre-rRNA methylation and ribosome assembly. Cell, 72, 443–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turley S.J., Tan, E.M. and Pollard, K.M. (1993) Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of U3 snoRNA-associated mouse fibrillarin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1216, 119–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidgren J., Svensson, L.A. and Liljas, A. (1994) Crystal structure of catechol O-methyltransferase. Nature, 368, 354–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Yokota, H., Kim, R. and Kim, S.-H. (1999) Expression, purification and preliminary X-ray analysis of a fibrillarin homologue from Methanococcus jannaschii, a hyperthermophile. Acta Crystallogr. D, 55, 338–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner J.R. (1990) The nucleolus and ribosome formation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 2, 521–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]