Abstract

Human bocavirus (HBoV) was discovered in 2005 and is associated with respiratory tract symptoms in young children. Three additional members of the genus Bocavirus, HBoV2, -3, and -4, were discovered recently from fecal specimens, and early results indicate an association between HBoV2 and gastrointestinal disease. In this study, we present an undifferentiating multiplex real-time quantitative PCR assay for the detection of these novel viruses. Differentiation of the individual bocavirus species can be subsequently achieved with corresponding singleplex PCRs or by sequencing. Both multiplex and singleplex assays were consistently able to detect ≤10 copies of HBoV1 to -4 plasmid templates/reaction, with dynamic quantification ranges of 8 logs and 97% to 102% average reaction efficiencies. These new assays were used to screen stool samples from 250 Finnish patients (median age, 40 years) that had been sent for diagnosis of gastrointestinal infection. Four patients (1.6%; median age, 1.1 years) were reproducibly positive for HBoV2, and one patient (0.4%; 18 years of age) was reproducibly positive for HBoV3. The viral DNA loads varied from <103 to 109 copies/ml of stool extract. None of the stool samples harbored HBoV1 or HBoV4. The highly conserved sequence of the hydrolysis probe used in this assay may provide a flexible future platform for the quantification of additional, hitherto-unknown human bocaviruses that might later be discovered. Our results support earlier findings that HBoV2 is a relatively common pathogen in the stools of diarrheic young children, yet does not often occur in the stools of adults.

During recent years, the number of bocaviruses known has increased rapidly. In addition to human parvovirus B19, the family Parvoviridae now also includes another pathogen member, human bocavirus (HBoV), first detected in pediatric respiratory secretions in 2005 (2). Several studies have shown an association of HBoV with acute respiratory tract symptoms in young children (1, 8, 14, 16). Three other human bocaviruses, designated HBoV2, HBoV3, and HBoV4, were recently reported in quick succession to have been detected in human feces (4, 12, 13) as well as sewage samples (5). Subsequent studies have indicated that HBoV2 occurs rarely in respiratory secretions but fairly commonly in stools of children, and it is likely to circulate globally (4, 6, 7, 10, 13, 19, 21). To date, two publications have provided evidence for an association of HBoV2 with gastrointestinal disease (4, 7). HBoV3 and HBoV4 were discovered so recently that little is known of their epidemiology, transmission, or pathogenicity (4, 6, 12, 19). However, the pathobiological characteristics of HBoV2 to -4 could conceivably be expected to be more similar to each other than to those of HBoV1, due to significantly closer phylogenic relationships (12).

While high-performance quantitative PCR (qPCR) assays are available for HBoV1 detection (15, 18), HBoV2 and HBoV3 have so far been detected by qualitative PCR. In addition to allowing for quantification of the target DNA, real-time qPCR has many other advantages, including a lower risk of contamination, decreased hands-on time, and better specificity of detection. Moreover, as we have shown serologically, the low-level presence of HBoV1 DNA in the nasopharynx is not a reliable indicator of acute HBoV1 infection (11, 20). The present study reports the development of multiplex and singleplex qPCR assays for sensitive real-time detection of all four human bocaviruses (HBoV1 to -4) in clinical samples. These new methods were validated using plasmids with cloned HBoV1 to -4 DNAs and stool samples from patients with or without a recent travel history. Furthermore, we wanted to investigate whether traveling beyond Northern Europe would result in elevated infection rates by these novel viruses, which might have regional differences in occurrence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical specimens.

Stool samples were obtained from 250 Finnish patients, 100 with and 150 without a history of travel outside Northern Europe within 1 month before sample acquisition. The median ages were 30.5 years (range, <1 to 74 years) and 52.5 years (range, <1 to 95 years), respectively. The destinations for the 100 travelers were Europe for 54%, Asia for 29%, Africa for 9%, South America for 2%, and unknown for 2% of travelers. Of the 250 subjects, 33 were children aged 0 to 10 years, of whom 12 (36%) had traveled abroad. All samples had been sent to the Helsinki University Central Hospital Laboratory Division for diagnosis of enteric pathogens, as suggested by symptoms of diarrhea. All samples were cultured for enteropathogenic bacteria, with emphasis on Salmonella, Yersinia, Shigella, and Campylobacter. In addition, several samples were studied for enteric parasites and viruses. All samples had further been tested for diarrheagenic Escherichia coli strains by PCR (3).

For PCR, stool swabs were suspended in 200 μl of Tris-EDTA buffer and boiled for 15 min, and the nucleic acids were purified with a NucliSENS kit using the easyMAG platform (bioMérieux, Lyon, France) and eluted in the elution medium to a volume of 25 μl. The median DNA concentration of the fecal extracts was 40 ng/μl (25th percentile, 20 ng/μl; 75th percentile, 77 ng/μl; range, 2 to 200 ng/μl). Potential PCR inhibition had been studied with 80 of the 250 DNA extracts by DNA spiking (17). None of the spiked samples were inhibitory. To further evaluate our qPCR assay, we analyzed three stool DNA extracts shown by qualitative PCR to contain HBoV2, HBoV3, or HBoV4 DNA (12).

Plasmids.

The performances of the qPCR assays were studied with plasmids containing the joint region of the left-hand untranslated region (UTR) and the NS1 gene of the human bocavirus 1 to 4 genomes, corresponding in HBoV1 to nucleotides (nt) 98 to 388 (GenBank accession number EU984245). The corresponding regions of HBoV2 (FJ170279) and HBoV3 (EU918736) were synthesized and cloned into pUC57 by Genscript (NJ), and that of HBoV4 was synthesized and cloned into pJet1.2 (Fermentas, Burlington, Canada) in Helsinki, Finland. The near-full-length HBoV1 clone, pST2, was a kind gift from Tobias Allander (2). Plasmid DNA concentrations were determined by an ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Nanodrop, Wilmington, DE). Each plasmid was diluted serially from 0.5 × 108 to 0.5 × 101 copies/μl in 10 mM Tris-EDTA buffer, aliquoted, and stored at −20°C until use for generation of standard curves for DNA quantification.

Of note, the HBoV2 and HBoV4 primer binding sites in the HBoV2 and HBoV4 plasmids are identical except for a single nucleotide mismatch in the sense primer (Fig. 1). This dissimilarity was taken into account by the use of a degenerate nucleotide (C+T; IUPAC code Y). The HBoV2 and HBoV4 plasmids were indistinguishable with respect to assay sensitivity and reproducibility. Moreover, Mfold (22) secondary structure predictions showed no major difference between the amplified regions of the two sequences (data not shown). Consequently, the results reported herein for HBoV2 and HBoV4 are designated HBoV2/4 results and were acquired using only the HBoV2 plasmid unless otherwise stated.

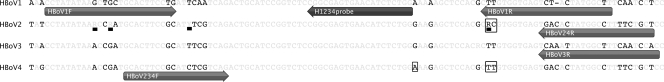

FIG. 1.

Nucleotide sequence alignment of the HBoV1 to -4 genome segments used for qPCR. Intraspecies sequence variation is underlined and shown as degenerate bases according to IUPAC symbols (R, A+G; Y, C+T). Fully conserved nucleotides are shown without underlining, whereas nucleotide differences between the species are in bold. Arrow symbols show the positions and directions of the corresponding primers and probe. For HBoV2 and HBoV4, direct PCR product identification is possible by PCR product sequencing to distinguish three nucleotide differences (boxed nucleotides).

Primers and hydrolysis probe.

Conserved and variable regions of the HBoV1 to -4 genomes were identified by aligning nine HBoV1 sequences, nine HBoV2 sequences, four HBoV3 sequences, and one HBoV4 sequence (Fig. 1). The HBoV1 and -2 strains were selected from a wide variety of geographical locations (10 countries) to take into account intraspecies variation. For HBoV3 and -4, we used all publicly available near-full-length genomic sequences. Primer selection was done with the aid of AlleleId 6.01 software (Premier Biosoft International, CA) for maximum intraspecies similarity and, when appropriate, maximum interspecies heterology. The primers are as follows (with GenBank accession numbers and primer annealing positions in parentheses): HBoV1F, 5′-CCTATATAAGCTGCTGCACTTCCTG-3′ (NC_007455; 152 to 177); HBoV1R, 5′-AAGCCATAGTAGACTCACCACAAG-3′ (NC_007455; 235 to 259); HBoV234F, 5′-GCACTTCCGCATYTCGTCAG-3′ (FJ170279; 50 to 70); HBoV3R, 5′-GTGGATTGAAAGCCATAATTTGA-3′ (EU918736; 205 to 230); and HBoV24R, 5′-AGCAGAAAAGGCCATAGTGTCA-3′ (FJ170279; 128 to 150). The primer region covers the left-hand untranslated region of the human bocavirus genome and the beginning of the NS1 gene. Both of the HBoV1 primers and the antisense HBoV3 primer (HBoV3R) were selected from regions with minimal similarity to the other bocaviruses. The qPCRs for HBoV2, -3, and -4 share a single sense primer (HBoV234F), and the qPCR for HBoV2 and -4 (i.e., the HBoV2/4 qPCR) uses the same reverse primer (HBoV2/4R). The hydrolysis probe sequence 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM)-5′-CCAGAGATGTTCACTCGCCG-3′-minor groove binder (MGB)-quencher black hole 1 (BHQ1) (FJ170279; 85 to 104) was selected from a region fully conserved between all four known human bocaviruses. In multiplex format, this combination of primers and hydrolysis probe was designed to detect all published types of human bocaviruses. In singleplex format, the primers were designed to distinguish between HBoV1, HBoV3, and HBoV2/4. All oligonucleotides were synthesized by Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany). The MGB hydrolysis probe was labeled at the 5′ end with the reporter dye FAM, and the 3′ end was blocked with the nonfluorescent quencher BHQ1. Blasting of primers and the probe against GenBank sequences did not reveal matching sequences that would plausibly result in probe hydrolysis. The amplified template region, together with 100 bp of surrounding sequence in both directions, was also analyzed for secondary structures with Mfold (22). No significant DNA secondary structures were detected (data not shown).

Real-time PCR.

All PCRs were done in a volume of 25 μl using Stratagene Mx3005p and approved clear PCR plasticware (Stratagene, CA). The singleplex reactions consisted of 1× TaqMan Universal Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, CA) with AmpErase uracil-N-glycosylase (UNG), 0.6 μM concentrations of sense and antisense primers, 0.3 μM probe, 2 μl of template, and molecular biology-grade water for a final volume of 25 μl. The multiplex reactions were set up similarly but with all five primers included. UNG was allowed to degrade any potential carryover PCR products for 2 min at 50°C before activation of the AmpliTaq Gold polymerase for 10 min at 95°C. The amplification consisted of 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C and 1 min at 60°C. Each run included plasmid and no-template controls. To generate baseline-corrected fluorescence (dR) data, baseline fluorescence was automatically determined by the Mx4000 software version 3.01 (Stratagene) baseline algorithm. The cutoff for quantification cycle (Cq) determination was automatically calculated as 20 times the standard deviation of the fluorescence value of the baseline in cycles 5 through 9. Each fluorescent reporter signal from the FAM channel was measured against the internal reference dye (ROX) signal to normalize for non-PCR-related fluorescence fluctuations between samples. Strict laboratory procedures were followed to prevent PCR contamination, including separate spaces for handling of samples, Master Mix ingredients, and plasmid templates. All runs included negative controls, which gave negative results for human bocavirus DNA throughout the study.

Analytical specificity.

Analytical specificities of the real-time qPCR assays were evaluated with 500 ng human DNA per reaction (i.e., 25 μl) from cultured 293T cells and cloned full-length or near-full-length genomes of TT virus (GenBank AY666122), parvovirus B19 genotypes 1 (AY504945), 2 (AY044266) and 3 (AJ249437; a kind gift from Antoine Garbarg-Chenon), and polyomaviruses BK virus (BKV), JC virus (JCV), and simian virus 40 (SV40) (kind gifts from Kristina Dörries). We also tested a partial genome of human parvovirus 4 (PARV4) and the late-region genes of KI polyomavirus (KIPyV) (EF127906; a kind gift from Tobias Allander). We further tested pooled nucleic acid extracts of human stool containing astrovirus, norovirus, and rotavirus. The stool specimens had been found virus positive by diagnostic electron microscopy and/or PCR by the Helsinki University Central Hospital Laboratory Division.

RESULTS

Analytical sensitivity, linearity, and amplification efficiency.

Limits of detection (LOD) of the real-time assays were determined with serial dilutions of control plasmids. At 10 copies/reaction (5,000 copies/ml of eluate), 100% of 20 replicates were positive with the multiplex and all singleplex assays regardless of the presence or absence of human genomic DNA at 500 ng/reaction. This indicates a robust LOD of ≤10 copies/reaction. We further tested 8 replicates of 10−2 to 102 nominal plasmid copies/reaction diluted in a pool (n = 140) of stool DNA extracts that were qPCR negative for human bocavirus. Testing was repeated with another instrument on a different day. A generalized linear model was fitted to the total observed proportion of positive results and to the nominal numbers of template copies using MATLAB software's (Mathworks, Natick, MA) GLMFIT command with the probit link function. According to the probit analysis, the assay sensitivities in stool extracts remained good, ranging from ∼4 copies/reaction (HBoV2/4) to ∼9 copies/reaction (HBoV1) for both the multiplex and the singleplex assays (data not shown).

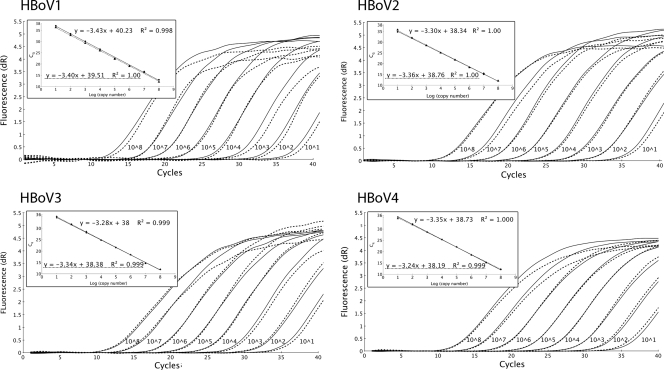

The real-time PCRs were linear over the range of 10 to at least 108 copies/reaction (Fig. 2). The average reaction efficiencies for the singleplex and multiplex reactions were high for all assays regardless of the presence or absence of 500 ng of human genomic DNA per reaction, ranging from 97% to 102% (Table 1).

FIG. 2.

Representative results from the real-time PCR quantification of serial dilutions of HBoV1, HBoV2, HBoV3, and HBoV4 plasmids (101 to 108 copies/reaction) with baseline-corrected fluorescence plotted against cycle number. Each type of plasmid was analyzed with the respective singleplex assay (solid curves) and the nondiscriminating multiplex assay (dotted curves). The insets show the corresponding standard curves with the logarithm of the input copy number (y) plotted against the corresponding Cq values (x), and the square of the correlation coefficient (R2). The standard curves for the singleplex (solid line) assays are almost indistinguishable from those of the multiplex (dotted line) assays.

TABLE 1.

Mean Cq values from human bocavirus singleplex assaysa

| Plasmid copy no. | Mean Cq value (±SD) for indicated plasmid |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without human DNA |

With 500 ng human genomic DNA |

|||||

| HBoV1 | HBoV2/4 | HboV3 | HBoV1 | HBoV2/4 | HBoV3 | |

| 101 | 36.2 ± 0.5 | 35.2 ± 0.8 | 34.4 ± 0.6 | 36.5 ± 0.7 | 35.4 ± 0.8 | 35.0 ± 0.7 |

| 102 | 32.7 ± 0.2 | 32.0 ± 0.1 | 32.0 ± 0.2 | 32.3 ± 0.2 | 32.2 ± 0.2 | 31.8 ± 0.2 |

| 103 | 29.1 ± 0.1 | 28.4 ± 0.1 | 28.0 ± 0.0 | 29.3 ± 0.1 | 28.3 ± 0.1 | 28.1 ± 0.1 |

| 104 | 25.9 ± 0.0 | 25.0 ± 0.0 | 25.0 ± 0.1 | 25.9 ± 0.0 | 24.8 ± 0.4 | 24.9 ± 0.1 |

| 105 | 22.2 ± 0.1 | 21.7 ± 0.0 | 22.1 ± 0.1 | 21.7 ± 0.1 | 21.4 ± 0.0 | 21.5 ± 0.1 |

| 106 | 19.0 ± 0.1 | 18.4 ± 0.1 | 18.4 ± 0.0 | 18.8 ± 0.1 | 18.7 ± 0.0 | 18.7 ± 0.1 |

| 107 | 16.5 ± 0.0 | 15.1 ± 0.2 | 14.6 ± 0.2 | 16.4 ± 0.1 | 15.1 ± 0.1 | 15.2 ± 0.1 |

| 108 | 12.1 ± 0.2 | 12.0 ± 0.3 | 12.0 ± 0.1 | 12.5 ± 0.1 | 12.0 ± 0.1 | 12.2 ± 0.20 |

| Efficiencyb | 97% | 98% | 98% | 97% | 97% | 98% |

| Slopec | −3.39 | −3.37 | −3.37 | −3.39 | −3.39 | −3.37 |

| y interceptc | 39.5 | 38.5 | 38.1 | 39.4 | 38.8 | 38.2 |

| R2 | 0.998 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.998 |

Values ± standard deviations (SD) from three replicate human bocavirus singleplex assays of estimated plasmid DNA copy number are shown. Cq, quantitation cycle; R2, square of correlation coefficient.

Efficiency (E) was calculated from the average slope of the standard curves using the formula E = 10(−1/slope) − 1.

The slope and y intercept were determined by the formula Cq = y intercept − slope × log(initial DNA quantity).

Analytical specificity.

Analytical specificities of the real-time PCR assays were evaluated with purified human DNA, DNA from virus-positive stool samples, and with cloned viral DNA of 9 viruses. All plasmids were tested at 1010 copies/reaction, corresponding to 5 × 1012 copies/ml of original sample. Neither the multiplex nor the singleplex qPCR assays showed observable amplification with any of the plasmids or clinical specimens within the 40 PCR cycles.

Cross-reactivity.

Potential cross-amplification of HBoV1 to -4 plasmid templates with the three singleplex assays was studied at high input levels of the plasmids (106 to 109 copies/reaction) with 10 replicates. No cross-amplification was observed with any of the assays at ≤2 × 107 copies/reaction. At 1 × 108 copies, the HBoV3 primers showed cross-amplification of HBoV2 and HBoV4 plasmids, with 9 copies/reaction detected. Similarly, HBoV2 primers showed cross-amplification of the HBoV3 plasmid at 1 × 109 copies/reaction (14 copies/reaction detected); however, no signal was generated at 2 × 108 copies/reaction or less. No cross-amplification with HBoV1 singleplex was observed at 2 × 109 copies/reaction of HBoV2, HBoV3, or HBoV4 templates. Copy numbers higher than 2 × 109 copies/reaction were not tested for cross-reactivity.

All singleplex assays were able to detect the respective bocavirus species also from mixtures of HBoV1 to -4 templates, in which HBoV1 to -4 were simultaneously present in varied quantities. Table 2 shows the calculated and measured amounts of HBoV1, HBoV2/4, and HBoV3 plasmids.

TABLE 2.

DNA quantification from heterologous mixtures of multiple human bocavirus plasmidsa

| Mix no.b | Calculated no. of copies per mix |

Measured no. of copies per mix (CV%c) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBoV1 | HBoV2/4 | HBoV3 | HBoV1 | HBoV2/4 | HBoV3 | |

| 1 | NT | 2 × 103 | 2 × 107 | No Cq | 1.4 × 103 (25) | 1.7 × 107 (11) |

| 2 | NT | 2 × 105 | 2 × 102 | No Cq | 1.5 × 105 (20) | 2.8 × 102 (24) |

| 3 | NT | 2 × 106 | 2 × 106 | No Cq | 1.5 × 106 (20) | 1.4 × 106 (25) |

| 4 | 2 × 103 | NT | 2 × 106 | 3.5 × 103 (38) | No Cq | 1.8 × 106 (7) |

| 5 | 2 × 106 | NT | 2 × 105 | 1.7 × 106 (11) | No Cq | 1.6 × 105 (16) |

| 6 | 2 × 101 | 2 × 107 | NT | 1.2 × 101 (35) | 1.3 × 107 (30) | No Cq |

| 7 | 2 × 107 | 2 × 101 | NT | 1.5 × 107 (20) | 3.3 × 101 (35) | No Cq |

| 8 | 2 × 104 | 2 × 106 | 2 × 103 | 4.4 × 104 (53) | 1.8 × 106 (7) | 1.2 × 103 (35) |

| 9 | 2 × 101 | 2 × 101 | 2 × 101 | 1.2 × 101 (35) | 1.1 × 101 (41) | 9.2 × 100 (52) |

| 10 | 2 × 101 | 2 × 104 | 2 × 106 | 1.1 × 101 (41) | 1.4 × 104 (25) | 1.9 × 106 (3.6) |

NT, no template; CV, coefficient of variation; Cq, quantification cycle.

Each row represents a single mix of templates. For instance, the mix 1 contains an estimated 2 × 103 copies of HBoV2 and 2 × 107 copies of HBoV3 plasmids but no HBoV1 plasmid.

CV%, CV percentage computed from the difference between the calculated and measured numbers of copies per mix without replicates.

Reproducibility.

Reproducibilities of the multiplex and singleplex assays were studied by replicate analysis of quantification standards in a single run (intraassay variation) and repeated runs (interassay variation) using three replicates, each at concentrations of 101 to 108 copies/reaction (Table 3). Of note, the intra- and interassay variations were calculated with measured quantities of target DNA rather than from the corresponding Cq values. Highest intra- and interassay variations were observed at 101 copies/reaction, with mean coefficients of variation (CV) of 40% and 33%, respectively. With 103 copies/reaction, the corresponding figures were reduced to 3% and 16%, respectively.

TABLE 3.

Reproducibility of HBoV1, HBoV2/4, and HBoV3 singleplex assays for different concentrations of the plasmidsa

| No. of copies/reaction | Intraassay variation (CV%) |

Interassay variation (CV%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBoV1 | HBoV2/4 | HBoV3 | HBoV1 | HBoV2/4 | HBoV3 | |

| 101 | 17.5 | 71.1 | 29.8 | 21.5 | 60.9 | 15.7 |

| 102 | 14.8 | 6.4 | 15.9 | 16.3 | 29.8 | 10.9 |

| 103 | 4.1 | 2.8 | 3.1 | 18.9 | 22.1 | 5.8 |

| 104 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 7.0 | 4.5 | 11.8 | 6.8 |

| 105 | 2.4 | 0.7 | 2.1 | 11.8 | 4.3 | 6.4 |

| 106 | 4.7 | 0.7 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 13.9 | 15.7 |

| 107 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 4.0 | 9.3 | 3.5 | 7.3 |

| 108 | 7.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 5.2 | 15.1 | 7.2 |

Intraassay variation was determined from three replicates within a single run, and interassay variation was determined from three replicates, each performed on different days. CV was calculated from the measured number of template rather than Cqs.

qPCR of stool extracts.

For clinical evaluation of the qPCR methods presented here, stool samples sent for diagnosis of enteric infections from Finnish travelers and nontravelers were screened for DNA of the four human bocaviruses. Of the 250 samples, 5 (2%) were found reproducibly positive for human bocavirus DNA in the initial multiplex screening. Of these 5 samples, 4 and 1 were positive with the HBoV2 and HBoV3 singleplex assays, respectively, and were further confirmed by sequencing. All four samples with HBoV2 DNA were from children aged ≤2 years, and the sample with HBoV3 DNA was from an 18-year-old female who had recently traveled to Bulgaria. The HBoV2 prevalence among 250 subjects below 95 years of age was only 1.6%; however, it was 10% among the 41 children below 18 years of age, 12.5% among the 32 children aged below 10 years, and 20% among the 20 infants ≤2 years of age. Further patient characteristics, including travel histories, HBoV DNA loads, and other microbial findings, are listed in Table 4. HBoV1 and HBoV4 DNAs were not detected in any of the 250 samples.

TABLE 4.

Characteristics of patients with human bocavirus in stoola

| Age (yr) | Gender | Virus | DNA load (copies/ml) | Recent travel to: | Other finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Female | HBoV2 | 1 × 109 | Spain | EPEC |

| 2 | Male | HBoV2 | 7.5 × 104 | Ethiopia | — |

| 1 | Male | HBoV2 | 4.1 × 105 | — | — |

| 1 | Female | HBoV2 | ≤103 | — | EPEC |

| 18 | Female | HBoV3 | ≤103 | Bulgaria | Salmonella enteritidis |

The DNA load is given as copies per ml of fecal extract. Recent travel, a journey outside Northern Europe within 1 month before sample acquisition. EPEC, enteropathogenic E. coli; —, no recent travels or no other findings.

With respect to HBoV1 to -3, the qPCR results were validated by rescreening all the samples with a previously described quantitative assay for HBoV1 (1) and qualitative PCR assays for HBoV2 (6) and HBoV3 (19). The results of the confirming HBoV1 qPCR assay were in full accordance with our original results: all 250 samples were negative for HBoV1 DNA. Likewise, the samples that were positive with our HBoV2 or HBoV3 singleplex assays were also positive with the respective qualitative PCR assays, with results confirmed by PCR product sequencing. The sequences from the qualitative PCRs were 98 to 100% identical to previously published HBoV2 and HBoV3 sequences, with no observable regional differences.

The three fecal extracts that had previously been shown to contain HBoV2, HBoV3, or HBoV4 DNA (12) were all reproducibly positive in the respective singleplexes, but not with the heterologous assays. Samples with HBoV2 and HBoV3 DNA were also positive in the multiplex qPCR. The HBoV4 positive sample was not multiplex tested due to the very limited amount of DNA extract available.

qPCR of serum DNA extracts.

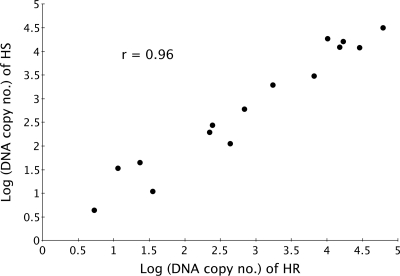

To further compare our new HBoV1 singleplex assay with the established qPCR test (1) that we have previously used for HBoV1 quantification (11, 20), we examined with both tests 15 serum samples that had been shown to contain different loads of HBoV1 DNA (1). Correlation between these two methods was high despite the relatively low levels of viral DNA (r = 0.95) (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

qPCR quantification of 15 HBoV1 DNA positive sera with a previously established (1) reference assay (HR) plotted against the HBoV1 singleplex assay (HS) introduced in this study. r, Spearman's rank correlation coefficient.

DISCUSSION

The new human bocaviruses and their possible roles in human disease are currently under intensive investigation. The methods published so far have relied on qualitative rather than quantitative PCR, which limits the interpretation of results and slows down sample screening. We present real-time qPCR assays for the detection of all currently known human bocaviruses, HBoV1, HBoV2, HBoV3, and HBoV4. The initial multiplex screening indiscriminately detects and gives a good estimate of the level of human bocavirus DNA in a sample. For this approximate quantification, the average standard curve of the three plasmids can be used as the quantification reference. The preliminary screening is followed by singleplex qPCRs of the positive samples to identify and accurately quantify the amount of viral DNA.

This rather unusual approach of using primers rather than hydrolysis probes for template identification has both advantages and drawbacks. In addition to lowered probe-related costs, another major advantage is that the new assays presented here can be used with minimal technological requirements. The only requirement is for the real-time machine to be capable of detecting the FAM signal; no multiplexing capability with multiple detection channels is required. In general, multiplexing with numerous fluorescent dyes can be a challenge for some laboratories with qPCR equipment with a limited variety of wavelength filters. Furthermore, multiplex data analysis may be affected by cross talk if the combination of chosen fluorophores is suboptimal for the qPCR hardware in use. Our approach bypasses these technical obstacles. The highly conserved probe furthermore may provide a flexible and low-cost qPCR platform for the quantification of related bocaviruses that might be discovered in the future.

A drawback with our approach is low-level cross-amplification of HBoV2/4 and HBoV3 bocaviruses in very high copy numbers. This is seen as dual positivity in the singleplex qPCRs and can be overcome by diluting and reanalyzing those samples. This could then lead to false-negative results if the samples simultaneously contained two different human bocaviruses, one at very high and the other at very low levels.

Such cases are, however, likely to be very rare and of little clinical significance.

A remaining difficulty is the separation of the genetically similar HBoV2 and -4 viruses, which in our approach requires PCR product sequencing. The currently available GenBank sequences show a three-nucleotide difference in the nonprimer sequence of our HBoV2 and HBoV4 PCR amplicons (Fig. 1). Whether these differences are conserved or variable will become known in the future upon accumulation of HBoV4 sequence data. All in all, the pathogenic respiratory bocavirus HBoV1, which has been found also in stool, is by our assays most clearly differentiated from the enteric species HBoV2 to -4, with no cross-reactivity with any of the three other human bocaviruses.

The repeatability of our assays may superficially appear to be low. However, rather than using quantification cycles (Cqs) for calculating coefficients of variance (CV), we calculated CV from measured numbers of template copies. The Cq method significantly underestimates the true assay variance (9). Furthermore, with our method, the CV values are comparable when varied amounts of starting template are used. This is not true for CV based on untransformed Cqs, as proportionally equal variations in observed levels of DNA cause significantly unequal absolute changes in Cq-derived CV in different regions of the dynamic range.

The three most recently identified human bocaviruses were discovered with stool samples, and HBoV2 has since been observed to be present not infrequently in feces of young children (4, 6, 12, 13). Also, the respiratory virus HBoV1 has been detected in stool (6, 18). To test and validate our new HBoV1 to -4 assays with such material, we used fecal samples from 250 patients of diverse ages. Our HBoV2 prevalence was 1.6% among all 250 subjects. However, all four HBoV2-positive children were ≤2 years of age. In this age group of 20 children, the HBoV2 prevalence was 20%, comparable to that of a previous study, which reported a 17% prevalence among young children with gastroenteritis and 8% among healthy children (4). Our results, together with those of two other recent studies (6, 13), suggest that HBoV2 DNA is detected mainly in the stools of children aged 5 years or less. The putatively narrow age range of HBoV2 infections should be taken into consideration when interpreting the percentages of HBoV2-positive subjects. In our study, the only bocavirus-positive adult, a female 18 years of age, harbored HBoV3. Altogether, the relatively low frequency of HBoV1, -3, and -4 among the 250 samples of this study are in line with the results of Kapoor et al. (12), who found these viruses in stools of only 1.4%, 2.8%, and 1.4% of 288 children, respectively, whereas HBoV2 occurred in 23.6% of the pediatric stool samples. However, a higher frequency of HBoV1 than HBoV2 DNA in the stools of children has also been reported (7). The same study also found HBoV2 DNA more frequently in the stools of adults than in those of children.

We furthermore examined the travel histories of our patients, with the hypothesis that traveling outside Northern Europe might result in first contact with a regional bocavirus species and result in an elevated infection rate. This same set of samples has been shown to contain a significantly higher proportion of diarrheagenic E. coli in travelers (39%) than in nontravelers (8.7%) (3). However, travelers and nontravelers harbored HBoV2 equally. Our results therefore do not support a link between travel beyond Northern Europe and increased infection risk by the enteric human bocaviruses. Our results with infants should, however, be considered with caution, because we tested only 20 children aged ≤2 years, resulting in a low statistical power. Furthermore, viral shedding among the subjects with a recent travel history may have ceased between the time of infection and the time of sample acquisition.

Our real-time qPCRs were highly sensitive and specific, and they reproducibly detected the genomic sequences of all four known human bocaviruses down to <10 copies/reaction. All other viral, human, or bacterial DNAs in native or plasmid form remained negative. Any putative secondary structures or the flanking terminal regions of the human bocavirus genome did not seem to interfere with the results, as our HBoV1 qPCR showed excellent correlation with a well-established HBoV1 qPCR assay that amplifies another genomic region (1). Furthermore, no interfering secondary structures were revealed by in silico nucleic acid folding predictions. Last, arguing against possible PCR inhibition, we found that (i) the analytical sensitivities of the multiplex and singleplex assays remained excellent (<10 copies/reaction) in the presence of pooled stool DNA extract, (ii) all the 80 spiked samples were noninhibitory (17), and (iii) 52 of these stool extracts were found to be PCR positive for other pathogens (3).

In conclusion, we present sensitive and specific real-time qPCR assays for the detection and quantification of all four species of human bocaviruses currently known, facilitating forthcoming studies of their epidemiology and pathobiology. Our findings furthermore support earlier notions on the preferential occurrence of HBoV2 in stool specimens from young children as opposed to those from adults.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Academy of Finland (project 1122539), the Helsinki University Central Hospital Research and Education Fund and Research and Development Fund, the Medical Society of Finland (FLS), and the Sigrid Jusélius Foundation (for K.K., R.S., K.H., and M.S.V.).

We thank Kristina Dörries for the BKV, JCV, and SV40 clones, Antoine Garbarg-Chenon for the B19 genotype 3 clone, Tobias Allander for the HBoV1 ST2 and polyomavirus KIPyV clones, and Olli Ruuskanen and Tuomas Jartti for the 15 serum samples.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 15 September 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allander, T., T. Jartti, S. Gupta, H. G. Niesters, P. Lehtinen, R. Österback, T. Vuorinen, M. Waris, A. Bjerkner, A. Tiveljung-Lindell, B. G. van den Hoogen, T. Hyypiä, and O. Ruuskanen. 2007. Human bocavirus and acute wheezing in children. Clin. Infect. Dis. 44:904-910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allander, T., M. T. Tammi, M. Eriksson, A. Bjerkner, A. Tiveljung-Lindell, and B. Andersson. 2005. Cloning of a human parvovirus by molecular screening of respiratory tract samples. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:12891-12896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antikainen, J., E. Tarkka, K. Haukka, A. Siitonen, M. Vaara, and J. Kirveskari. 2009. New 16-plex PCR method for rapid detection of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli directly from stool samples. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 28:899-908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arthur, J. L., G. D. Higgins, G. P. Davidson, R. C. Givney, and R. M. Ratcliff. 2009. A novel bocavirus associated with acute gastroenteritis in Australian children. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blinkova, O., K. Rosario, L. Li, A. Kapoor, B. Slikas, F. Bernardin, M. Breitbart, and E. Delwart. 2009. Frequent detection of highly diverse variants of cardiovirus, cosavirus, bocavirus, and circovirus in sewage samples collected in the United States. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:3507-3513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chieochansin, T., A. Kapoor, E. Delwart, Y. Poovorawan, and P. Simmonds. 2009. Absence of detectable replication of human bocavirus species 2 in respiratory tract. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 15:1503-1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chow, B. D., Z. Ou, and F. P. Esper. 2010. Newly recognized bocaviruses (HBoV, HBoV2) in children and adults with gastrointestinal illness in the United States. J. Clin. Virol. 47:143-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fry, A. M., X. Lu, M. Chittaganpitch, T. Peret, J. Fischer, S. F. Dowell, L. J. Anderson, D. Erdman, and S. J. Olsen. 2007. Human bocavirus: a novel parvovirus epidemiologically associated with pneumonia requiring hospitalization in Thailand. J. Infect. Dis. 195:1038-1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garson, J. A., J. F. Huggett, S. A. Bustin, M. W. Pfaffl, V. Benes, J. Vandesompele, and G. L. Shipley. 2009. Unreliable real-time PCR analysis of human endogenous retrovirus-W (HERV-W) RNA expression and DNA copy number in multiple sclerosis. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 25:377-378. Author reply, 379-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han, T. H., J. Y. Chung, and E. S. Hwang. 2009. Human bocavirus 2 in children, South Korea. Emerging Infect. Dis. 15:1698-1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kantola, K., L. Hedman, T. Allander, T. Jartti, P. Lehtinen, O. Ruuskanen, K. Hedman, and M. Söderlund-Venermo. 2008. Serodiagnosis of human bocavirus infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46:540-546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kapoor, A., P. Simmonds, E. Slikas, L. Li, L. Bodhidatta, O. Sethabutr, H. Triki, O. Bahri, B. S. Oderinde, M. M. Baba, D. N. Bukbuk, J. Besser, J. Bartkus, and E. Delwart. 2010. Human bocaviruses are highly diverse, dispersed, recombination prone, and prevalent in enteric infections. J. Infect. Dis. 201:1633-1643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kapoor, A., E. Slikas, P. Simmonds, T. Chieochansin, A. Naeem, S. Shaukat, M. M. Alam, S. Sharif, M. Angez, S. Zaidi, and E. Delwart. 2009. A newly identified bocavirus species in human stool. J. Infect. Dis. 199:196-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kesebir, D., M. Vazquez, C. Weibel, E. D. Shapiro, D. Ferguson, M. L. Landry, and J. S. Kahn. 2006. Human bocavirus infection in young children in the United States: molecular epidemiological profile and clinical characteristics of a newly emerging respiratory virus. J. Infect. Dis. 194:1276-1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu, X., M. Chittaganpitch, S. Olsen, I. Mackay, T. Sloots, A. Fry, and D. Erdman. 2006. Real-time PCR assays for detection of bocavirus in human specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:3231-3235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maggi, F., E. Andreoli, M. Pifferi, S. Meschi, J. Rocchi, and M. Bendinelli. 2007. Human bocavirus in Italian patients with respiratory diseases. J. Clin. Virol. 38:321-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matero, P., T. Pasanen, R. Laukkanen, P. Tissari, E. Tarkka, M. Vaara, and M. Skurnik. 2009. Real-time multiplex PCR assay for detection of Yersinia pestis and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. APMIS 117:34-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neske, F., K. Blessing, F. Tollmann, J. Schubert, A. Rethwilm, H. W. Kreth, and B. Weissbrich. 2007. Real-time PCR for diagnosis of human bocavirus infections and phylogenetic analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santos, N., T. Peret, C. Humphrey, M. Albuquerque, R. Silva, F. Benati, X. Lu, and D. Erdman. 2010. Human bocavirus species 2 and 3 in Brazil. J. Clin. Virol. 48:127-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Söderlund-Venermo, M., A. Lahtinen, T. Jartti, L. Hedman, K. Kemppainen, P. Lehtinen, T. Allander, O. Ruuskanen, and K. Hedman. 2009. Clinical assessment and improved diagnosis of bocavirus-induced wheezing in children, Finland. Emerging Infect. Dis. 15:1423-1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song, J. R., Y. Jin, Z. P. Xie, H. C. Gao, N. G. Xiao, W. X. Chen, Z. Q. Xu, K. L. Yan, Y. Zhao, Y. D. Hou, and Z. J. Duan. 2010. Novel human bocavirus in children with acute respiratory tract infection. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 16:324-327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zuker, M. 2003. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:3406-3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]