Abstract

IFNγ exerts multiple biological effects on effector cells by regulating many downstream genes, including smooth muscle-specific genes. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying IFNγ-induced inhibition of smooth muscle-specific gene expression remain unclear. In this study, we have shown that serum response factor (SRF), a common transcriptional factor important in cell proliferation, migration, and differentiation, is targeted by IFNγ in a STAT1-dependent manner. We show that the molecular mechanism by which IFNγ regulates SRF is via activation of the 2-5A-RNase L system, which triggers SRF mRNA decay and reduced SRF expression. As a result, decreased SRF expression reduces expression of SRF target genes such as smooth muscle α-actin and smooth muscle myosin heavy chain. Additionally, IFNγ reduced p300 and acetylated histone-3 binding in both smooth muscle α-actin and SRF promoters, epigenetically decreasing smooth muscle α-actin and SRF transcriptional activation. Our data reveal that SRF is a novel IFNγ-regulated gene and further elucidate the molecular pathway between IFNγ, IFNγ-regulated genes, and SRF and its target genes.

Keywords: Actin, Gene Regulation, Interferon, Liver, Liver Injury, Smooth Muscle, Fibrosis, Wound Healing

Introduction

IFNγ, a pleiotropic cytokine that is primarily produced by T cells and NK cells, plays a complex and central role in antiviral, antiproliferative, antifibrogenesis, antitumor, and immunomodulatory activities (reviewed in Refs. 1 and 2). The complexity of such a variety of IFNγ effects appears to be achieved by its signaling to over 200 genes, leading to a highly networked pattern of cell-specific gene regulation (3). In the canonical pathway, through binding to cognate IFN type II receptors, IFNγ initiates a cascade that includes JAK family kinases and the STAT1 family of transcriptional factors to induce STAT1-dependent gene expression, which largely mediates the actions of IFNγ (reviewed in Ref. 4). Among IFNγ-regulated genes, smooth muscle α-actin, a cytoskeleton protein that is critical in smooth muscle cell differentiation (reviewed in Ref. 5), myofibroblast activation (reviewed in Ref. 6), and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (7), is negatively regulated by IFNγ (8, 9). Although the observation that IFNγ regulates smooth muscle α-actin is well established, the molecular mechanisms underlying IFNγ-induced inhibition of smooth muscle α-actin expression remain unclear.

Regulation of smooth muscle α-actin expression is complex, having been studied extensively in cardiovascular and vascular diseases, particularly in smooth muscle cells (reviewed in Ref. 5). It has been well demonstrated that most muscle-specific genes, including smooth muscle α-actin, are SRF2 target genes. SRF binds to the CArG boxes (CC(A/T)6GG) of the smooth muscle α-actin gene promoter and activates smooth muscle α-actin transcription (reviewed in Ref. 10). Extracellular factors can exert their effects on smooth muscle gene expression through regulating SRF or/and SRF cofactors (11). TGFβ, a well characterized cytokine important in smooth muscle cell differentiation and epithelial-mesenchymal transition, up-regulates smooth muscle α-actin expression in both smooth muscle and nonsmooth muscle cells and is mediated through a TGFβ-responsive element in smooth muscle α-actin gene promoter (12) and elevation of SRF expression (13, 14). Although IFNγ clearly exhibits an inhibitory effect on smooth muscle α-actin expression in smooth muscle (8) and nonsmooth muscle cell types (9), its effects on the smooth muscle α-actin promoter are unknown.

Previous studies have shown that IFNγ inhibits smooth muscle α-actin expression in activated hepatic stellate cells (9), a cell type that undergoes phenotypic transition to a myofibroblast-like cell in a process that is tightly linked to a smooth muscle-specific gene expression program (15, 16). Further, IFNγ exerts a protective role in liver fibrogenesis, likely via effects on stellate cells (17). In the present study, we have demonstrated the presence of a novel signaling network linking IFNγ, SRF, and smooth muscle-specific genes. We show that the mechanism by which IFNγ regulates SRF is via the 2-5A-RNase L system, which triggers SRF mRNA decay. The degradation of SRF mRNA, in turn, creates a negative autoregulatory cycle, which further reduces SRF expression (18) and consequently reduces smooth muscle α-actin and smooth muscle myosin heavy chain (SMMHC). The findings provide novel insight into the molecular mechanism of IFNγ-mediated regulation of smooth muscle-specific genes.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Stellate Cell Isolation, Culture, and Animals

All stellate cells used in the experiments presented were primary cells isolated from normal Sprague-Dawley rats or wild type Balb/c or STAT1-deficient mice as described in the supplemental data. STAT1-deficient mice (129S6/SvEV; Taconic Farms, Germantown, NY) were backcrossed with Balb/c inbred mice (Taconic) for more than four generations. Genotyping of the mice was performed by PCR as described (17). Cell purity was assessed by examination of morphologic features, vitamin A droplets, and immunohistochemical detection of desmin (characteristic of stellate cells) and was greater than 95% pure in all cases as described previously (15). Stellate cells were cultured for 4–5 days (activated stellate cells) before experiments unless indicated otherwise. The animals were cared for and experiments were performed in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines.

Plasmids

A −125 + 5-bp fragment of the rat smooth muscle (SM) α-actin promoter (SMpro-125) and a −787 + 11-bp fragment of the mouse SRF promoter (SRFpro-787) were cloned from genomic DNA using PCR. PCR primers were designed based on available DNA sequences (GenBankTM accession numbers S76011 and AC165445). The sequence of the isolated mouse SRF gene promoter (798 bp) has been submitted to GenBankTM (accession number EF654102). PCR products were ligated into a pGL3 Basic luciferase reporter vector (Promega), and a series of deletions and mutations were generated. A rat SRF mRNA 3′-UTR fragment (1,500 bp from the stop codon; GenBankTM accession number XM-576514) was cloned from rat stellate cell cDNA and inserted into the XbaI site of pGL3 promoter luciferase reporter vector. Mouse RNase L (GenBankTM accession number NM-0118820) cDNAs were cloned into a pcDNA3.1 vector (with a FLAG tag). The SMMHC promoter construct was obtained from Dr. White (University of Vermont).

For RPA cRNA probe constructs, 237-bp fragments of rat and mouse SM α-actin were subcloned from SM α-actin full-length cDNA (GenBankTM accession numbers X06801 and X13297, respectively) into pGEM7Zf(+) (Promega); the rat SMMHC cRNA probe was constructed by cloning a 552-bp cDNA fragment (GenBankTM accession number XM_001053402) into PCRII vector (Invitrogen); a 156-bp fragment of rat SRF cDNA (GenBankTM accession number XM-576514) was cloned and ligated into pGEM7Zf(+); and a 292-bp fragment of mouse RNase L cDNA was subcloned from full-length RNase L cDNA and inserted into the XbaI and HindIII sites of pGEM7Zf(+) vector (Promega).

The sequences for the all of the constructs were confirmed by sequencing (University of Texas Southwestern DNA sequencing core facility). All of the PCR primers are available in the supplemental data.

Transfection and Luciferase Assay

Stellate cells were transduced with 2 μg of plasmid DNA using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). The cells were incubated with 199OR medium containing 0.1% serum with or without IFNγ (1,000 IU/ml; PBL Biomedical) for 2 days, and whole cell lysates were assayed using a dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega). All of the transfection experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated at least three times. The number of relative light units from pGL3 basic luciferase reporter vector (pGL3B) (Promega) was arbitrarily set to 1, and the experimental data were presented as fold increase relative to pGL3B activity. The number of relative light units from pGL3 promoter-SRF mRNA 3′-UTR construct was arbitrarily set to 100, and the experimental data were presented as a percentage of decrease.

Overexpression of Exogenous RNase L

HEK293 cells were grown in DMEM, 10% FBS, and the expression plasmid harboring FLAG-tagged RNase L was transduced using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) with low serum (0.5%) medium overnight. The cells were harvested after 24 h for immunoblot. Wild type RNase L (RNase L+/+) and RNase L null (RNase L−/−) mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) were obtained from Dr. Silverman (Cleveland, Ohio).

Immunoblot

Cultured stellate cells were washed three times with cold PBS, and proteins were extracted with radioimmune precipitation assay buffer containing protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Science). The cell lysates were incubated on ice for 30 min and centrifuged at 4 °C for 20 min. The supernatant was harvested, and protein concentration was measured (Bio-Rad). Proteins were subjected to immunoblotting as described previously (19). Anti-SM α-actin, anti-β-actin, anti-FLAG M2, and anti-α-tubulin were from Sigma; anti-SRF and anti-pSTAT1 were from Santa Cruz, and anti-STAT1 was from BD Transduction Laboratories. Specific signals were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce) and captured with a digital imaging system (Chemigenius 2 photo documentation system; Syngene). The intensities of specific bands were quantified using standard software (Gene Tool, Syngene), and the raw volume from the first control sample (IFNγ −) in each experiment was arbitrarily set at 100. The specific protein expression in each sample was presented as a percentage of decrease.

RNase Protection Assay

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen) and hybridized with radioactively labeled cRNA probes using an RPA III kit (Ambion) as performed (17). For RNA decay assay, stellate cells were starved (0.1% serum) for 1 day and incubated with IFNγ (1,000 IU/ml) for 2 h, and actinomycin D (10 μg/ml; Sigma) was subsequently added. The specific mRNA abundances at the indicated time points were measured by RPA. The raw volume from the first control sample (IFNγ −) or actinomycin D zero time point sample was arbitrarily set at 100. The reduction of mRNA expression in each sample was presented as a percentage of decrease.

EMSA

Nuclear extracts were prepared as described (19). The nuclear proteins were incubated with 32P-labeled double-stranded DNA probe for 30 min. The resulting DNA-protein complexes were separated by nondenaturing electrophoresis. For supershift assay, 2 μl of anti-SRF or pSTAT1 (Santa Cruz) antibody was incubated with the reaction mixture for 30 min before incubation with 32P-labeled probe. All of the oligonucleotide sequences for EMSA are available in the supplemental data.

ChIP Assay

Stellate cells were starved (0.1% serum) for 1 day, and IFNγ (1,000 IU/ml) was added for 16 h. ChIP assay was performed using ChIP assay kit (Upstate) as described (20). The antibodies against SRF, pSTAT1, and normal mouse and rabbit IgG were obtained from Santa Cruz; anti-acetylated H3 (H3Ac) and anti-P300 antibodies were from Upstate. Unless stated otherwise, the results have been presented as percentages relative to normalized sample input (the average raw volume of input samples was arbitrarily set to 1). The data from at least three individual experiments are presented graphically.

Statistics

All of the experiments were repeated at least three times, unless otherwise stated. A Student's t test was used for comparison in experiments examining the effect of IFNγ (i.e. +IFNγ versus −IFNγ). The level of significance was considered to be p < 0.05.

RESULTS

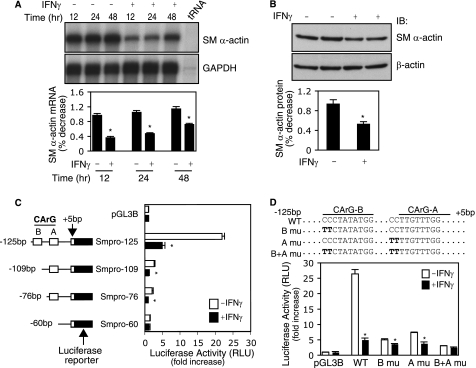

IFNγ-mediated Inhibition of Smooth Muscle α-Actin Expression Is Dependent on CArG Boxes

We initially examined the effect of IFNγ on smooth muscle α-actin mRNA expression in activated stellate cells. As shown in Fig. 1A, the expression of smooth muscle α-actin mRNA was significantly suppressed between 12 and 24 h after IFNγ exposure. Concomitant with the effect of IFNγ on smooth muscle α-actin mRNA, smooth muscle α-actin protein levels were also reduced (Fig. 1B). To explore the molecular mechanism by which IFNγ exerts its inhibitory effect on smooth muscle α-actin expression, we examined smooth muscle α-actin transcriptional regulation. Constructs harboring a series of rat smooth muscle α-actin promoter fragments were generated and used to examine promoter activity. In Fig. 1C, it is shown that the Smpro-125 construct, which contains CArG-B and A boxes, generated a prominent response to IFNγ: a 5-fold reduction of promoter activity compared with control. However, deletion of the CArG-B box (Smpro-109) resulted in marked reduction of promoter activity, which was almost complete after IFNγ exposure. Because CArG boxes are known to be DNA-binding sites for SRF, these data suggest that the IFNγ-mediated inhibitory effect on smooth muscle α-actin gene promoter activity is linked to SRF.

FIGURE 1.

IFNγ-mediated inhibition of smooth muscle α-actin requires CArG boxes. A and B, stellate cells were starved (0.1% serum) for 1 day and subsequently exposed to IFNγ. The cells were harvested, and RNA was isolated at the indicated times. In A, SM α-actin mRNA abundance was measured by RPA as under “Experimental Procedures” (n = 3; *, p < 0.05 for IFNγ versus control (−)). In B, following exposure to IFNγ for 48 h, the cells were harvested and subjected to immunoblotting to detect SM α-actin (β-actin was used as a loading control) (n = 3; *, p < 0.05 for IFNγ versus control (−)). C, luciferase reporter constructs harboring different truncated SM α-actin gene promoter (Smpro) fragments were transduced into stellate cells, and promoter activity was assayed (n = 3; *, p < 0.01 for IFNγ versus control). D, SM α-actin gene promoter CArG B and A boxes were mutated individually or combination. The resultant luciferase reporter constructs were transduced into stellate cells, and promoter activity was assayed (n = 3; *, p < 0.01 for IFNγ versus control). GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; IB, immunoblot; RLU, relative light units.

To further examine the relationship between CArG boxes and the IFNγ-mediated inhibitory effect on smooth muscle α-actin promoter activity, we generated mutations in CArG-B and CArG-A boxes. Promoter activity for the wild type construct was reduced by 5-fold following IFNγ treatment (Fig. 1D). In contrast, mutation of CArG-A or CArG-B boxes or both led to reduced promoter activity and a loss of IFNγ responsiveness. These data indicate that smooth muscle α-actin promoter CArG-A and CArG-B boxes are critical in mediating the inhibitory effect of IFNγ on smooth muscle α-actin expression and that SRF is an important intermediate partner.

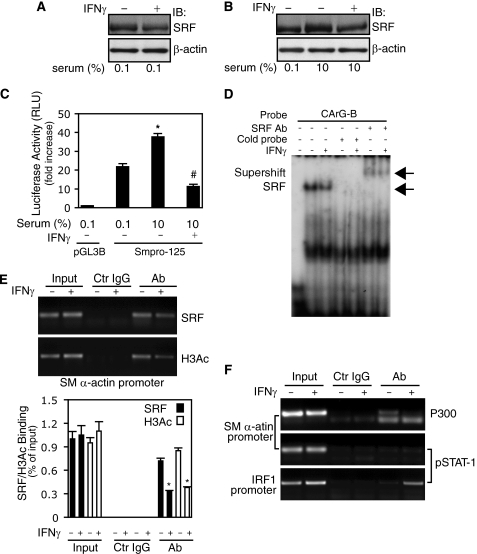

IFNγ Reduces SRF Expression and Binding to the Smooth Muscle α-Actin Promoter

Given previous data indicating that SRF is an essential transcription factor for multiple muscle-specific genes, we postulated that it might be a target of IFNγ. To explore this possibility, we examined known IFNγ signaling pathways in stellate cells. As predicted, IFNγ exposure led to increases in STAT1 phosphorylation (pSTAT1) in both whole cell lysates and nuclear extracts (supplemental Fig. S1A). Next, we found that IFNγ led to a significant reduction in SRF expression in stellate cells (Fig. 2A). Serum stimulation increased SRF expression and failed to elevate SRF in the presence of IFNγ (Fig. 2B). These data indicate that SRF is a target of IFNγ in stellate cells. Next, we examined whether the IFNγ-mediated inhibition of SRF expression affected smooth muscle α-actin promoter activity. Serum stimulation increased promoter activity compared with 0.1% serum-containing medium (Fig. 2C). However, IFNγ abrogated this effect. These data suggest that the IFNγ-induced inhibitory effect on smooth muscle α-actin promoter activity occurs, at least in part, via reduction of SRF in stellate cells.

FIGURE 2.

IFNγ-STAT1 pathway reduces SRF expression and binding to CArG boxes in smooth muscle α-actin promoter. A, stellate cells were starved (0.1% serum) for 1 day and incubated with IFNγ for 2 days. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting with anti-SRF antibody. B, stellate cells were starved (0.1% serum) for 1 day, then replaced with 10% serum-containing 199OR medium with or without IFNγ for 2 days. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting with anti-SRF antibody. C, following transduction with the Smpro-125 luciferase reporter construct, stellate cells were incubated in 0.1% serum-containing medium for 2 days, and then the medium was changed to 10% serum-containing medium with or without IFNγ for a further 24 h. Cell lysates were assayed for luciferase activity (n = 3; *, p < 0.01 for 0.1% versus 10% serum-containing medium; #, p < 0.01 for IFNγ versus control). D, after incubation with 0.1% serum-containing medium for 1 day, stellate cells were exposed to IFNγ for 2 days, and nuclear extracts were prepared for EMSA with a probe containing the CArG-B box of SM α-actin gene promoter. The left-most lane contains buffer plus labeled probe only (i.e. without nuclear extract). The arrows denote the SRF and probe complex or a supershift complex with SRF antibody. E and F, stellate cells were starved (0.1% serum) for 1 day and exposed to IFNγ for 16 h; cells were subjected to ChIP assay as under “Experimental Procedures”. In E, the data are depicted graphically below (n = 3; *, p < 0.01 for IFNγ versus control). IB, immunoblot; Ab, antibody; Ctr, control.

Because smooth muscle α-actin promoter activity is SRF-dependent (Fig. 1D), we examined whether IFNγ might inhibit SRF binding activity. In these experiments, a probe containing the CArG-B box of smooth muscle α-actin promoter was utilized. Nuclear extracts from stellate cells exposed to IFNγ had a weaker shifted band compared with control (Fig. 2D). The addition of anti-SRF antibody and cold probe demonstrated that the SRF binding was specific. These data suggest that IFNγ reduces nuclear SRF binding in stellate cells. Further, we examined whether IFNγ decreased SRF binding to smooth muscle α-actin promoter CArG boxes in vivo. Following exposure of stellate cells to IFNγ for 16 h, SRF binding to smooth muscle α-actin promoter CArG boxes was dramatically reduced compared with control (Fig. 2E). Interestingly, decreased binding of SRF to smooth muscle α-actin promoter CArG boxes was accompanied by reduced binding of H3Ac, which itself is associated with gene transcriptional activation (21). We also found that IFNγ reduced both SRF and H3Ac binding to smooth muscle α-actin promoter CArG boxes even under serum stimulation (supplemental Fig. S1B). Because p300, a transcriptional coactivator, plays a critical role in gene regulation through histone acetylation and interaction with a variety of transcriptional factors such as STAT1 (22), we examined whether p300 and STAT1 might form DNA-protein complexes in the smooth muscle α-actin promoter in vivo. As shown in Fig. 2F (top panel), p300 was found in control, but after exposure to IFNγ, p300 in the smooth muscle α-actin promoter essentially disappeared, consistent with the reduced amount of H3Ac in the smooth muscle α-actin promoter after IFNγ (Fig. 2E). In contrast, we could not identify pSTAT1 in the smooth muscle α-actin promoter (Fig. 2F, middle panel; as a control, pSTAT1 was readily identified in the interferon regulatory factor 1 gene promoter, Fig. 2F, bottom panel). Taken together, these data demonstrate that both SRF expression and binding activity to smooth muscle α-actin promoter CArG boxes were significantly reduced by IFNγ. IFNγ also induced negative epigenetic regulation of smooth muscle α-actin through reducing smooth muscle α-actin promoter histone 3 acetylation.

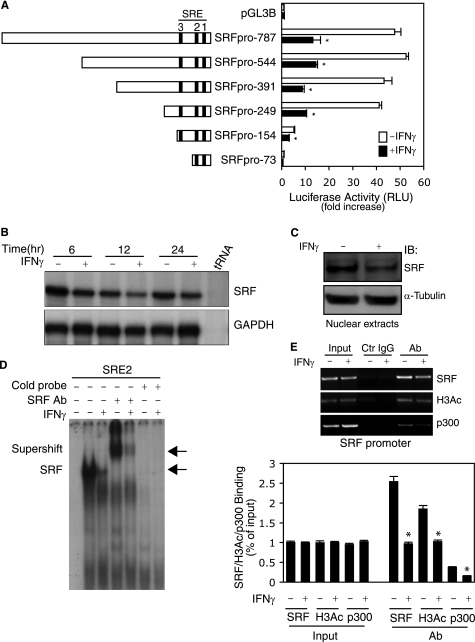

IFNγ Inhibits SRF Expression through Its Own Transcriptional Regulation

To further explore the molecular mechanism by which IFNγ down-regulates SRF, we cloned a 798-bp fragment in the proximal SRF gene promoter region from stellate cells and tested the effects of IFNγ on SRF transcription. SRF promoter activity was dramatically suppressed by IFNγ (Fig. 3A). Next, we asked whether IFNγ-mediated suppression of SRF promoter activity could be associated with the serum response elements of the SRF gene promoter. As shown in supplemental Fig. S2, all of the serum response elements appeared to be required for maintenance of full SRF promoter activity. Mutation of serum response elements 1 and 2 in the SRF promoter substantially abrogated the inhibitory effect of IFNγ on SRF promoter activity. These data led us to further hypothesize that IFNγ could reduce SRF mRNA levels. As expected, SRF mRNA expression was reduced at all time points after IFNγ exposure compared with control (Fig. 3B). However, the most prominent SRF mRNA reduction occurred at the 12-h time point, which correlated with the most significant reduction in smooth muscle α-actin mRNA (Fig. 1A). Given the finding that IFNγ down-regulated SRF mRNA expression, we further hypothesized that SRF levels in stellate cell nuclei would likewise be reduced, in turn leading to reduced SRF binding to its own gene promoter. To test this postulate, we examined SRF levels in stellate cell nuclear extracts as well as SRF binding activity to SRF promoter CArG boxes in vitro and in vivo. IFNγ decreased SRF in stellate cell nuclei (Fig. 3C). SRF binding to its CArG boxes was reduced following IFNγ exposure (Fig. 3, D and E). Additionally, H3Ac and p300 were reduced in the SRF promoter after IFNγ exposure. These findings were similar to those found with the smooth muscle α-actin promoter (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 3.

IFNγ inhibits SRF promoter activity and reduces SRF binding to CArG boxes in the SRF promoter. A, stellate cells were transduced with truncated SRF reporter constructs as indicated and then incubated in 0.1% serum-containing 199OR medium with or without IFNγ for 2 days. The cell lysates were assayed to detect SRF promoter activity (n = 3; *, p < 0.01 for IFNγ versus control). B, stellate cells were starved (0.1% serum) for 1 day and exposed to IFNγ at indicated time points. Total RNA was extracted, and SRF mRNA levels were measured by RPA. C and D, stellate cells were starved in 0.1% serum-containing 199OR medium for 1 day and exposed to IFNγ for 2 days. SRF was detected in nuclear extracts by immunoblotting (C) and EMSA (D). The left-most lane contains buffer plus labeled probe only (i.e. without nuclear extract). The arrows denote SRF and probe complex and supershift complex with SRF antibody (D). E, stellate cells were starved (0.1% serum) for 1 day and exposed to IFNγ for 16 h. SRF binding activity to its own promoter was examined by ChIP assay. The data are depicted graphically below (n = 3; *, p < 0.01 for IFNγ versus control). GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; IB, immunoblot; Ctr, control; Ab, antibody.

We next examined whether two potential γ-activated sites (GAS) (23) in the SRF promoter might modulate SRF expression. As shown in supplemental Fig. 3A, pSTAT1 did not appear to form a DNA-protein complex with either of the two putative SRF GAS elements. Although cross-linked DNA-pSTAT1complexes could be readily identified in the lysates from cells exposed to IFNγ (supplemental Fig. 3B), specific DNA fragments harboring GAS elements from the SRF gene promoter were undetectable whether exposed to IFNγ or not (supplemental Fig. S3C, upper panel). In contrast, a DNA fragment containing the interferon regulatory factor 1 GAS element was identified (supplemental Fig. S3C, lower panel). These data suggest that IFNγ-mediated down-regulation of SRF occurs via pathways other than by direct targeting of SRF gene transcription.

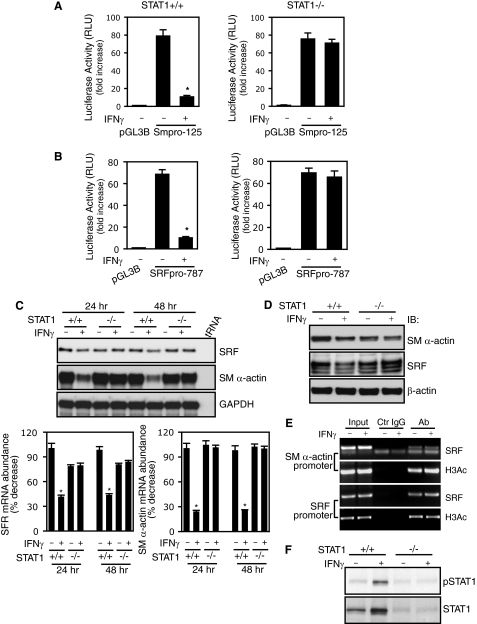

IFNγ-mediated Down-regulation of Smooth Muscle α-Actin and SRF Is STAT1-dependent

Because IFNγ exerts its effects through both STAT1-dependent and -independent pathways (24), we studied stellate cells from STAT1+/+ (wild type) and STAT1−/− (knock-out) mice. Stellate cells from STAT1+/+ mice (Fig. 4A, left panel) and STAT1−/− mice (Fig. 4A, right panel) exhibited remarkably different promoter activity responses to IFNγ. Smooth muscle α-actin promoter activity was reduced by IFNγ in stellate cells from STAT1+/+ mice but not in those from STAT1−/− mice. Similar results were obtained in experiments with SRF promoter constructs (Fig. 4B), in which the inhibitory effect of IFNγ on SRF promoter activity was abrogated in STAT1-deficient stellate cells (Fig. 4B, right panel). The results suggest that IFNγ- inducedinhibitory effects on smooth muscle α-actin and SRF promoter activity are both STAT1-dependent.

FIGURE 4.

STAT1 is required for IFNγ-induced down-regulation of smooth muscle α-actin and SRF. A and B, stellate cells from STAT1 wild type (+/+) and STAT1 knock-out (−/−) mice were transduced with SM α-actin (A) or SRF (B) reporter constructs as indicated. The cells were incubated in 0.1% serum-containing medium with or without IFNγ for 2 days before harvest (n = 3; *, p < 0.01 for IFNγ versus control). C, stellate cells from wild type and STAT1 knock-out mice were serum-starved for 1 day and then exposed to IFNγ for 24 or 48 h. SM α-actin and SRF mRNA levels were measured by RPA. The data were quantitated and are depicted graphically below (n = 3; *, p < 0.01 for IFNγ versus control). D, stellate cells were starved (0.1% serum) for 1 day and incubated with or without IFNγ for 2 days. The cell lysates were immunoblotted with specific antibodies as indicated. E, stellate cells from STAT1−/− mice were serum-starved for 1 day and exposed to IFNγ for 16 h. ChIP assay was performed as in Fig. 2E. F, genotypes of wild type and STAT1 knock-out stellate cells were further verified by immunoblotting. RLU, relative light units; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; IB, immunoblot; Ab, antibody; Ctr, control.

Given the evidence that STAT1 is required for the negative effects of IFNγ on both smooth muscle α-actin and SRF promoter activity, we reasoned that IFNγ-mediated down-regulation of smooth muscle α-actin and SRF gene expression would be abrogated in STAT1-deficient stellate cells. As predicted, SRF and smooth muscle α-actin mRNA expression were reduced in stellate cells from STAT1+/+ mice after IFNγ exposure (Fig. 4C). However, smooth muscle α-actin and SRF mRNA levels were not reduced by IFNγ in STAT1-deficient stellate cells. Immunoblot analyses paralleled mRNA findings (Fig. 4D). We further examined whether STAT1 is required for IFNγ-mediated inhibition of SRF binding activity and histone 3 acetylation in both smooth muscle α-actin and SRF promoters. IFNγ failed to reduce SRF and H3Ac binding activity in both promoters in STAT1-deficient stellate cells (Fig. 4E). Further, we examined pSTAT1 levels in stellate cells from STAT1+/+ and STAT1−/− mice (Fig. 4F). pSTAT1 was readily detected in STAT1+/+ stellate cells following IFNγ but was undetectable in stellate cells from STAT1−/− mice.

IFNγ Induces SRF mRNA Degradation in a STAT1-dependent Manner

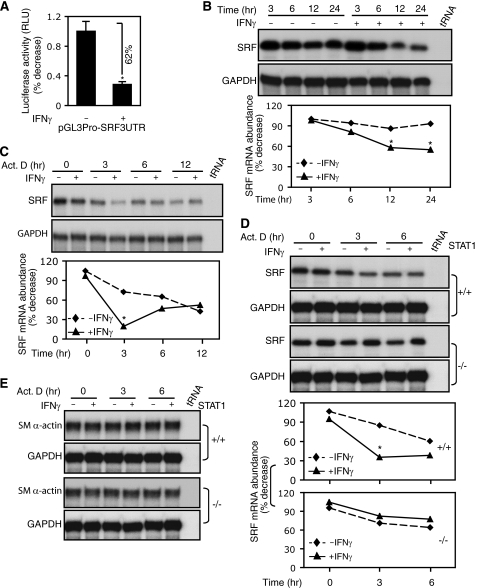

It is well known that mRNA stability plays an important role in determining levels of gene expression (25). We further examined whether IFNγ might contribute to SRF mRNA degradation in stellate cells. We first cloned the rat SRF mRNA 3′-UTR region and examined mRNA decay with a luciferase reporter; IFNγ significantly reduced luciferase activity (Fig. 5A), suggesting that IFNγ likely targets SRF mRNA stability. Next, we examined whether IFNγ might contribute to SRF mRNA degradation in stellate cells. IFNγ led to a persistent decrease in SRF mRNA levels, whereas SRF mRNA levels in control samples remained stable (Fig. 5B). We further examined whether IFNγ enhances SRF mRNA decay under actinomycin D treatment. The cells were exposed to IFNγ for 2 h to activate the IFNγ signal pathway (supplemental Fig. S1A) and then incubated with actinomycin D. SRF mRNA was decreased at the 3-h time point compared with controls (Fig. 5C). These results suggest that IFNγ is able to activate SRF mRNA degradation machinery in stellate cells.

FIGURE 5.

IFNγ induces SRF mRNA degradation but has no effect on smooth muscle α-actin mRNA stability. A, following transfection with a SRF mRNA 3′-UTR-luciferase report construct, stellate cells were exposed to IFNγ for 2 days, and luciferase activity was measured in cell lysates (n = 3; *, p < 0.05 for IFNγ versus control). B, following serum starvation (0.1%) for 1 day, stellate cells were exposed to IFNγ for various periods of time, and total RNA was subsequently extracted and subjected to RPA. The data were quantitated and are depicted graphically below (n = 3; *, p < 0.01 for IFNγ versus control). C, stellate cells were starved (0.1% serum) for 1 day. The cells were exposed to IFNγ for 2 h and then incubated with actinomycin D (10 μg/ml). Total RNA was subsequently extracted and subjected to RPA. The data were quantitated and are depicted graphically below (n = 3; *, p < 0.01 for IFNγ versus control). D and E, stellate cells from wild type (+/+) and STAT1 knock-out (−/−) mice were subjected to mRNA decay assay as in C. The data were quantitated and are depicted graphically (n = 3; *, p < 0.01 for IFNγ versus control in C). GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; Act. D, actinomycin D.

Given that IFNγ down-regulated SRF mRNA expression via a STAT1-dependent pathway, we further hypothesized that deletion of STAT1 would abrogate IFNγ-mediated SRF mRNA decay in stellate cells. As predicated, IFNγ led to degradation of SRF mRNA in stellate cells from STAT1+/+ mice, similar to rat stellate cells (Fig. 5D). Notably, IFNγ failed to induce SRF mRNA degradation in STAT1-deficient stellate cells (Fig. 5D). These data suggest that IFNγ targets the SRF gene via post-transcriptional STAT1-mediated SRF mRNA degradation.

Furthermore, we explored whetherIFNγ might induce smooth muscle α-actin mRNA degradation, which would contribute to the reduction in smooth muscle α-actin expression. Compared with SRF, IFNγ had little effect on smooth muscle α-actin mRNA stability in stellate cells (Fig. 5E), suggesting that IFNγ reduces smooth muscle α-actin expression not directly but by regulation of SRF.

The 2-5A Synthetase-RNase L System Mediates IFNγ-induced SRF mRNA Decay

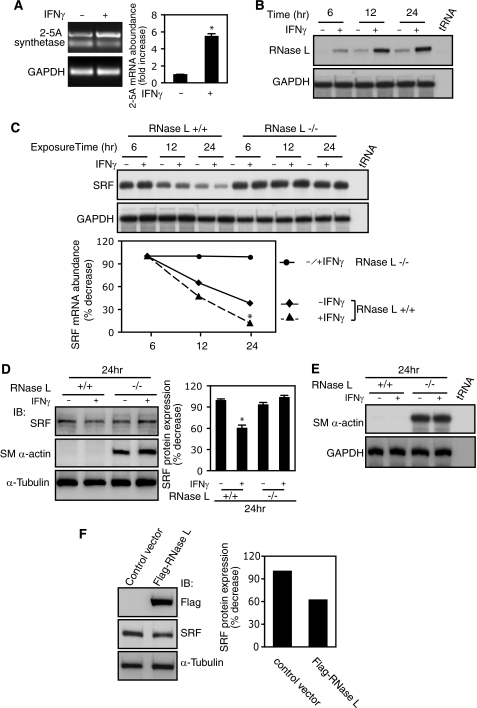

To explore the pathways leading to SRF mRNA decay, we first examined the 2-5A system, an RNA degradation pathway that can be induced by IFNs (26). IFNγ increased 2-5A synthetase mRNA levels ∼5-fold compared with control (Fig. 6A). Because 2-5A synthetase generates 2-5A and activates RNase L, we hypothesized that RNase L might also respond to IFNγ stimulation. As shown in Fig. 6B, RNase L mRNA levels were robustly stimulated by IFNγ compared with control. Next, we examined whether RNase L targets SRF mRNA by using RNase L−/− MEFs (27). IFNγ reduced SRF mRNA levels in RNase L+/+ MEFs but failed to reduce SRF mRNA levels in RNase L-deficient MEFs (Fig. 6C). The results suggested that RNase L plays a critical role in IFNγ-mediated SRF mRNA degradation. We next examined SRF protein levels in RNase L−/− and RNase L+/+ MEFs following IFNγ exposure. IFNγ led to a reduction in SRF expression in wild type but not knock-out RNase L MEFs (Fig. 6D, top panel), consistent with the SRF mRNA levels depicted in Fig. 6C.

FIGURE 6.

SRF is a novel target gene of IFNγ-induced 2-5A-RNase L system. A, stellate cells were serum-starved (0.1%) for 1 day and exposed to IFNγ for 24 h. 2-5A synthetase 1A mRNA expression was determined by RT-PCR (n = 3; *, p < 0.05 for IFNγ versus control). B and C, RNase L+/+ (B) and RNase L−/− (C) MEFs were serum-starved (0.2%) for 1 day and exposed to IFNγ at the indicated time points. RNase L (B) and SRF (C) mRNA expression were measured by RPA. In C, the data were quantitated and are depicted graphically (n = 3; *, p < 0.05 for IFNγ versus control in RNase L+/+ MEFs). D and E, RNase L+/+ and RNase L−/− MEFs were serum-starved (0.2%) for 1 day and exposed to IFNγ for 24 h. In D, cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting with specific antibodies as indicated. The data were quantitated and are depicted graphically (n = 3; *, p < 0.05 for IFNγ versus control in RNase L+/+ MEFs). In E, SM α-actin mRNA expression was measured by RPA. F, HEK293 cells were transfected with a mouse FLAG-RNase L expression construct or an empty vector overnight and incubated in 0.2% serum-containing medium for 24 h, and nuclear extracts were subjected to immunoblotting with specific antibodies as indicated. SRF bands were quantitated and shown in the graph on the right. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; IB, immunoblot.

Because RNase L has been shown to regulate skeletal muscle cell differentiation (28), we postulated that it may also regulate smooth muscle programs. Interestingly, smooth muscle α-actin expression was detected in RNase l−/− MEFs but not in RNase L+/+ MEFs at both protein (Fig. 6D, middle panel) and mRNA levels (Fig. 6E). Notably, IFNγ-induced inhibition of smooth muscle α-actin expression was abrogated in RNase L null MEFs (Fig. 6, D and E), which paralleled SRF levels in these cells (Fig. 6, C and D, top panel). Furthermore, overexpression of RNase L led to decreased SRF levels in HKE293 cells compared with the control (Fig. 6F). Taken together, these data indicated that SRF is a new molecular target in the IFNγ-induced 2-5A-RNase L pathway, which plays a critical role in IFNγ-induced SRF mRNA degradation.

IFNγ-induced Inhibition of SMMHC mRNA Expression Links to Decreased SRF Binding in CArG Box of SMMHC Promoter

In addition to smooth muscle α-actin, SMMHC is another smooth muscle cell and myofibroblast marker, whose expression, at least in smooth muscle cells, is also tightly controlled by SRF (5). Therefore, we examined whether IFNγ-induced targeting of SRF might affect SMMHC mRNA expression. SMMHC mRNA expression was reduced at all time points following IFNγ exposure (Fig. 7A). Promoter analysis indicated that IFNγ-induced reduction of luciferase activity was closely linked to CArG boxes in the SMMHC promoter (Fig. 7B). Next, we examined SRF binding activity to the SMMHC promoter CArG box. As predicted, IFNγ caused a reduction in SRF binding to the SMMHC promoter CArG box compared with control (Fig. 7C). These data provide further evidence for the prominent effect of IFNγ on SRF (and thus a repertoire of smooth muscle-specific gene expression).

FIGURE 7.

IFNγ inhibits SMMHC mRNA expression and SRF binding to SMMHC promoter CArG boxes. A, stellate cells were serum-starved (0.1% serum) for 1 day and exposed to IFNγ at the indicated time points. Total RNA was isolated, and SMMHC mRNA expression was measured by RPA. B, a luciferase reporter plasmid harboring different truncated SMMHC promoter fragments was created as in the top panel. Following transfection, stellate cells were incubated in 0.1% serum-containing medium with or without IFNγ for 2 days. Cell lysates were assayed for luciferase activity (n = 3; *, p < 0.05 for IFNγ versus control). C, stellate cells were serum-starved (0.1% serum) for 1 day and exposed to IFNγ for 2 days. Nuclear extracts were subjected to EMSA. The arrows denote shifted bands and supershift with SRF antibody. The first lane on the left contains buffer plus labeled probe only (i.e. without nuclear extract). D, an overview of the IFNγ SRF signaling pathway is highlighted. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; Ab, antibody; RLU, relative light units.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have identified a novel target of IFNγ, namely SRF. We have also discovered a novel IFNγ-induced SRF mRNA decay-promoting pathway that involves the 2-5A-RNase L system. Together, this pathway makes up a novel signaling network from IFNγ to SRF and smooth muscle protein expression (Fig. 7D). In the context of IFNγ biology, our work is consistent with previous studies emphasizing a number of IFNγ-regulated genes. Further, elucidation of such targets is critical for understanding IFNγ-mediated biological effects (1, 3, 29).

Abundant evidence links IFNγ to fibrogenesis, and this cytokine has been proposed as a putative therapy for fibrosis (17, 30, 31). In the wounding milieu, IFNγ exhibits prominent inhibitory effects on fibroblasts and myofibroblasts, including hepatic stellate cells, liver-specific myofibroblasts. Myofibroblasts are characterized by de novo expression of smooth muscle α-actin and excessive production of extracellular matrix, particularly collagen type 1 (32). Although the mechanisms for IFNγ-mediated inhibition of collagen type 1 expression have been well described (33), the molecular mechanism by which IFNγ inhibits smooth muscle α-actin expression appears to be different. Specifically, the effect of IFNγ on myofibroblasts appears to be tightly linked to SRF regulation. Here, we have demonstrated that the binding activity of SRF to the smooth muscle α-actin promoter (CArG boxes) is reduced by IFNγ (Figs. 1 and 2). This occurs as a result of IFNγ targeting SRF (Fig. 2). We speculate that IFNγ-mediated inhibition of SRF (Figs. 2 and 3) is likely to be a critical modulator of myofibroblast differentiation in wound healing, because SRF targets the promoters of multiple smooth muscle genes that are expressed in myofibroblasts. In support of this position is our finding that not only did IFNγ inhibit smooth muscle α-actin but also it potently inhibited SMMHC promoter activity (Fig. 7B). Further, because SRF is also regulated in an apparent feedback loop (18), it is possible that reduction of SRF by IFNγ likely has indirect effects on its own promoter activity (supplemental Fig. S2). Interestingly, reduced SRF binding in the smooth muscle α-actin and SRF promoters was closely linked to decreased p300 and H3Ac binding (Figs. 2 and 3), which further led to decreased SRF and smooth muscle α-actin expression through IFNγ-induced negative epigenetic regulation.

Although IFNγ is able to signal via STAT1-independent pathways, the IFNγ-STAT1 pathway likely mediates the majority of IFNγ-induced biological effects, which have been well demonstrated in STAT1 gene knock-out animal models (34). Our data are highly consistent with this position, as specifically demonstrated in Figs. 4 and 5. The finding that STAT1 deletion completely abrogated IFNγ-mediated SRF mRNA decay (Fig. 5) and previous work linking STAT1 to 2-5A synthetase/RNase L (26) led us to explore the possibility that the 2-5A synthetase/RNase L signal pathway could play a role in our system. We found that IFNγ regulated SRF mRNA stability in a 2-5A synthetase/RNase L-dependent manner (Fig. 6). Thus, our data have also highlighted an additional novel target (i.e. SRF) of the 2-5A synthetase/RNase L system. A surprising finding in our study was that smooth muscle α-actin expression was activated in RNase L-deficient MEFs (Fig. 6, D and E). This finding implicates the 2-5A synthetase/RNase L system in control of smooth muscle gene transcriptional activation through regulation of SRF and/or SRF cofactors. For example, it remains to be determined whether RNase L also targets the SRF cofactor, myocardin, whose expression was tightly linked to smooth muscle-specific gene expression including smooth muscle α-actin and SMMHC (35).

RNase L is a latent endoribonuclease whose activity appears to be tightly regulated by 2-5A. Furthermore, 2-5A is generated by 2-5A synthetase, which is induced by IFNs (36). Importantly, the effects of 2-5A are transient, because 2-5A is unstable due to the activities of phosphodiesterases and phosphatases (37). Such a sensitive regulatory cascade appears to be important for regulating protein synthesis via mRNA degradation in response to exogenous stimuli. In our study, IFNγ-induced 2-5A synthetase and RNase L expression rapidly increased at ∼12 h (Fig. 6, A and B); simultaneously, SRF/smooth muscle α-actin mRNA levels reached their lowest point at ∼12 h (3 h with actinomycin D) and then gradually rebounded (Figs. 1, 2, 3, and 5). The phenomenon of SRF mRNA rebound was highly reproducible and likely reflects a crucial effect of RNase L in regulation of SRF mRNA stability (Fig. 6) as well as the complex nature of the SRF mRNA regulatory machinery. Nonetheless, these data integrate IFNγ-STAT1 signaling with the 2-5A/RNase L system, SRF, and SRF target genes and provide a framework for a complicated molecular regulatory network for IFNγ-mediated inhibition of smooth muscle-specific gene expression (Fig. 7D).

Identification of SRF as a novel target of IFNγ in myofibroblasts has implications not only for wound healing but also in vascular biology and perhaps even oncogenesis. It is well appreciated that SRF plays a central role in smooth muscle cell differentiation, which is characterized by expression of a unique repertoire of contractile proteins, such as smooth muscle α-actin and SMMHC. Vascular diseases such as atherosclerosis are characterized by dysregulation of contractile protein expression in smooth muscle cells, and it is likely that SRF plays a role in regulation of these proteins (10). Further, SRF expression appears to be linked to cancer invasion/metastasis (38). Thus, although speculative, our data raise the possibility that the IFNγ-SRF signaling pathway identified here could be important in oncogenesis. Finally, the complicated nature by which SRF is regulated in our system and in other studies implies a highly complex regulatory hierarchy and suggests that efforts to manipulate SRF biologically will be challenging.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Yingyu Ren for expert assistance with rat and mouse stellate cell isolation and culture and Tianxia Li for assistance with RNase protection assays and immunoblots. We thank R. H. Silverman for RNase L−/− and RNase L+/+ MEF cell lines and S. L. White for the rat SMMHC gene promoter plasmid.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 DK 60338 and R01 DK 50574 (to D. C. R.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental text, Table S1, and Figs. S1–S3.

- SRF

- serum response factor

- SM α-actin

- smooth muscle α-actin

- H3Ac

- acetylated histone 3

- SMMHC

- smooth muscle myosin heavy chain

- RPA

- RNase protection assay

- MEF

- mouse embryo fibroblast

- GAS

- γ-activated site(s)

- 2-5A

- 2′-5′-phosphodiester-linked oligoadenylates.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boehm U., Klamp T., Groot M., Howard J. C. (1997) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 15, 749–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunn G. P., Koebel C. M., Schreiber R. D. (2006) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 6, 836–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Der S. D., Zhou A., Williams B. R., Silverman R. H. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 15623–15628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schroder K., Hertzog P. J., Ravasi T., Hume D. A. (2004) J. Leukocyte Biol. 75, 163–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Owens G. K., Kumar M. S., Wamhoff B. R. (2004) Physiol. Rev. 84, 767–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hinz B., Phan S. H., Thannickal V. J., Galli A., Bochaton-Piallat M. L., Gabbiani G. (2007) Am. J. Pathol. 170, 1807–1816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thiery J. P., Acloque H., Huang R. Y., Nieto M. A. (2009) Cell 139, 871–890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hansson G. K., Hellstrand M., Rymo L., Rubbia L., Gabbiani G. (1989) J. Exp. Med. 170, 1595–1608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rockey D. C., Maher J. J., Jarnagin W. R., Gabbiani G., Friedman S. L. (1992) Hepatology 16, 776–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miano J. M., Long X., Fujiwara K. (2007) Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 292, C70–C81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoshida T., Hoofnagle M. H., Owens G. K. (2004) Circ. Res. 94, 1075–1082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang J., Zohar R., McCulloch C. A. (2006) Exp. Cell. Res. 312, 205–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herrmann J., Haas U., Gressner A. M., Weiskirchen R. (2007) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1772, 1250–1257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sandbo N., Kregel S., Taurin S., Bhorade S., Dulin N. O. (2009) Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 41, 332–338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rockey D. C., Boyles J. K., Gabbiani G., Friedman S. L. (1992) J. Submicrosc. Cytol. Pathol. 24, 193–203 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brenner D. A., Waterboer T., Choi S. K., Lindquist J. N., Stefanovic B., Burchardt E., Yamauchi M., Gillan A., Rippe R. A. (2000) J. Hepatol. 32, (Suppl. 1) 32–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi Z., Wakil A. E., Rockey D. C. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 10663–10668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Belaguli N. S., Schildmeyer L. A., Schwartz R. J. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 18222–18231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shao R., Shi Z., Gotwals P. J., Koteliansky V. E., George J., Rockey D. C. (2003) Mol. Biol. Cell. 14, 2327–2341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meeson A. P., Shi X., Alexander M. S., Williams R. S., Allen R. E., Jiang N., Adham I. M., Goetsch S. C., Hammer R. E., Garry D. J. (2007) EMBO J. 26, 1902–1912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mizzen C. A., Allis C. D. (1998) Cell. Mol. Life. Sci. 54, 6–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horvai A. E., Xu L., Korzus E., Brard G., Kalafus D., Mullen T. M., Rose D. W., Rosenfeld M. G., Glass C. K. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 1074–1079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tau G., Rothman P. (1999) Allergy 54, 1233–1251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Darnell J. E., Jr., Kerr I. M., Stark G. R. (1994) Science 264, 1415–1421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garneau N. L., Wilusz J., Wilusz C. J. (2007) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8, 113–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bisbal C., Silverman R. H. (2007) Biochimie 89, 789–798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khabar K. S., Siddiqui Y. M., al-Zoghaibi F., al-Haj L., Dhalla M., Zhou A., Dong B., Whitmore M., Paranjape J., Al-Ahdal M. N., Al-Mohanna F., Williams B. R., Silverman R. H. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 20124–20132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bisbal C., Silhol M., Laubenthal H., Kaluza T., Carnac G., Milligan L., Le Roy F., Salehzada T. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 4959–4969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fujita T., Maesawa C., Oikawa K., Nitta H., Wakabayashi G., Masuda T. (2006) Int. J. Mol. Med. 17, 605–616 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muir A. J., Sylvestre P. B., Rockey D. C. (2006) J. Viral Hepat. 13, 322–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raghu G., Brown K. K., Bradford W. Z., Starko K., Noble P. W., Schwartz D. A., King T. E., Jr. (2004) N. Engl. J. Med. 350, 125–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Friedman S. L. (2008) Gastroenterology 134, 1655–1669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Higashi K., Inagaki Y., Suzuki N., Mitsui S., Mauviel A., Kaneko H., Nakatsuka I. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 5156–5162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meraz M. A., White J. M., Sheehan K. C., Bach E. A., Rodig S. J., Dighe A. S., Kaplan D. H., Riley J. K., Greenlund A. C., Campbell D., Carver-Moore K., DuBois R. N., Clark R., Aguet M., Schreiber R. D. (1996) Cell 84, 431–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang D., Chang P. S., Wang Z., Sutherland L., Richardson J. A., Small E., Krieg P. A., Olson E. N. (2001) Cell 105, 851–862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liang S. L., Quirk D., Zhou A. (2006) IUBMB Life. 58, 508–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Player M. R., Torrence P. F. (1998) Pharmacol. Ther. 78, 55–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Medjkane S., Perez-Sanchez C., Gaggioli C., Sahai E., Treisman R. (2009) Nat. Cell. Biol. 11, 257–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.