Abstract

The mammalian retina is comprised of six major neuronal cell types and is subdivided into more morphological and physiological subtypes. The transcriptional machinery underlying these subtype fate choices is largely unknown. The LIM-homeodomain protein, Isl1, plays an essential role in central nervous system (CNS) differentiation but its relationship to retinal neurogenesis remains unknown. We report here its dynamic spatiotemporal expression in the mouse retina. Among bipolar interneurons, Isl1 expression commences at postnatal day (P)5 and is later restricted to ON-bipolar cells. The intensity of Isl1 expression is found to segregate the pool of ON-bipolar cells into rod and ON-cone bipolar cells with higher expression in rod bipolar cells. As bipolar cell development proceeds from P5–10 the colocalization of Isl1 and the pan-bipolar cell marker Chx10 reveals the organization of ON-center bipolar cell nuclei to the upper portion of the inner nuclear layer. Further, whereas Isl1 is predominantly a ganglion cell marker prior to embryonic day (E)15.5, at E15.5 and later its expression in nonganglion cells expands. We demonstrate that these Isl1-positive, nonganglion cells acquire the expression of amacrine cell markers embryonically, likely representing nascent cholinergic amacrine cells. Taken together, Isl1 is expressed during the maturation of and is later maintained in retinal ganglion cells and subtypes of amacrine and bipolar cells where it may function in the maintenance of these cells into adulthood. J. Comp. Neurol. 503: 182–197, 2007.

Indexing terms: ON-bipolar cells, Chx10, amacrine cell, retina, neurogenesis, transcription factors, subtype markers

The vertebrate retina is a three-layered sensory structure comprised of six major neuronal cell types and one glial cell type. The inner nuclear layer (INL) contains four of the seven major cell types found in the retina: horizontal, bipolar, Müller, and amacrine cells. These different cell types are arranged in a laminar fashion. Horizontal cells are located closer to the outer, scleral end of the eye and amacrine cells closer to the inner, vitreous end. Cell bodies for bipolar cells and Müller cells lie between horizontal and amacrine cells. The photoreceptors, rods and cones, reside in the outer nuclear layer (ONL) and the ganglion cell layer (GCL) contains ganglion cells and displaced amacrine cells. In the INL, bipolar and amacrine cells transmit and modulate visual signals in the retina, respectively. Both cell types display well-documented anatomic and physiologic heterogeneities that contribute to the scope of visual processing at the level of the retina. An unanswered question in retinogenesis is precisely how this heterogeneity is realized. The scope of bipolar and amacrine cell differentiation encompasses their diversification into multiple subtypes with distinguishing morphological, physiologic, and antigenic differences. For example, bipolar cell pools are parsed into ON-center and OFF-center categories depending on whether they depolarize (ON-center) or hyperpolarize (OFF-center) in response to light (Werblin and Dowling, 1969; Nelson, 1978; Nelson and Kolb, 1983). Bipolar cells are further divided into cone and rod bipolar subtypes based on the predominant photoreceptor type from which they receive synaptic input (Kolb and Famiglietti, 1974; Brown and Masland, 1999; Masland, 2001). While markers of terminally differentiated bipolar and amacrine subtypes exist, their expression often commences after major decisions in a cell’s ontogeny are made, such as is the case for PKCα and choline acetyltransferase (ChAT), respectively (Galli-Resta et al., 1997; Bramblett et al., 2004). Developmental markers, on the other hand, are useful in labeling cells undergoing differentiation. Such markers are expressed prior to adult cell-type markers and identify subsets of bipolar and amacrine cells within the total pool of developing cells. Early antigenic markers specific for different subtypes of amacrine or bipolar cells, while few in number, double in their roles of labeling cells developmentally and of being candidates for cell-type diversification. Even a fewer number of such markers display the specificity to explain how fundamental differences in bipolar or amacrine cell physiology arise (Bramblett et al., 2004; Chow et al., 2004; Feng et al., 2006).

Mouse amacrine cells can be distinguished morphologically into at least 26 subtypes. A number of transmitter molecules are used to identify some of these different subsets of amacrine cells (Masland, 2001; Mo et al., 2004). Cholinergic or starburst amacrine cells are a population of ChAT-positive cells implicated in the generation of retinal waves (Famiglietti, 1983; Masland, 2005; Zheng et al., 2006). While some factors governing amacrine cell differentiation have been revealed (Li et al., 2004), how amacrine subtypes are generated is just being established. Recently, Foxn4 has been shown to regulate the development of amacrine and horizontal cells (Li et al., 2004), while Bhlhb5 regulates the development of subpopulations of amacrine and bipolar cells (Feng et al., 2006).

Retinogenesis spans embryonic and postnatal developmental periods, beginning midway through gestation (embryonic day 10, E10) and proceeding through the second postnatal week (Cepko et al., 1996). Beginning at E11, retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) are among the first retinal cells to differentiate. Bipolar cells arise principally during the later half of retinal development, relying heavily on the appropriate expression of multiple coordinately acting transcription factor classes, most notably, the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) and homeodomain-containing transcriptional regulators, Mash1, Math3, and Chx10 (Hatakeyama et al., 2001). Amacrine cells arise earlier, starting at E11 and proceeding to the fourth day postnatally.

Isl1 is a highly conserved transcriptional regulator belonging to a family of LIM homeodomain-containing proteins that orchestrate cell fate decisions in a variety of systems (Pfaff et al., 1996; Hobert and Westphal, 2000). Adult retinal expression of Isl1 is restricted to subpopu-lations of bipolar, amacrine, and ganglion cells (Galli-Resta et al., 1997). Our objective was to characterize Isl1’s expression at relevant timepoints during the ontogeny of retinal cell generation in the mouse retina. The early expression of Isl1 within differentiating RGCs and subsets of bipolar and amacrine cells suggests Isl1 could function in diversifying these neuronal pools.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

To generate the Isl1lacZ allele, genomic sequences were isolated from a mouse 129S6 (formerly 129SvEvTac) BAC library (CHORI) using Isl1 coding sequences as a probe. The Isl1lacZ targeting construct was generated by inserting 2.5 kb of 5′-flanking sequences that ends immediately upstream of the translational initiation codon ATG in exon 1 and 4.2 kb of 3′-flanking sequences into the BamHI and the Not1 sites of the pKII-lacZ vector, respectively. The knockin construct removed the translational initiation codon ATG in exon 1 and the entire exon 2 sequence, which encodes the first LIM domain. This was replaced by the coding sequence for the lacZ reporter gene under the control of Isl1 regulatory sequences. To generate Isl1lacZ knockin mice, an AscI-linearized Isl1lacZ targeting construct was electroporated into W4 mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells (a gift from Dr. Alexandra Joyner, New York University). Targeted ES clones were obtained from 192 G418- and FIAU-resistant ES clones. Genotypes of targeted clones were confirmed by Southern blotting. Targeted ES clones were injected into C57BL/6Jblastocysts to generate mouse chimeras and heterozygous Isl1lacZ mice were generated in a 129S6 and C57BL/6J mixed background. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) methods were used to genotype mice from subsequent breeding of Isl1lacZ heterozygotes to wildtype C57Bl/6J mice. The PCR primers used to identify the lacZ knockin allele were 5′-AGGGCCGCAAGAAAACTATCC-3′ and 5′ACTTCGGCA-CCTTAC GCTTCTTCT-3′. Embryos were designated as E0.5 at noon on the day at which vaginal plugs were observed. All animal procedures in this study were approved by the University Committee of Animal Resources (UCAR) at the University of Rochester.

Retinal tissue preparation

Retinas of embryonic and postnatal C57BL/6J mice were investigated in this study. Postnatal eyes were enucleated and the anterior segment and vitreous were removed to make posterior eyecups. Eyecups and embryos were fixed with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde in 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.3) for 10 minutes to overnight at 4°C. After fixation the samples were washed in PBS at room temperature to remove residual fixative and cryoprotected in 20% sucrose. The samples were subsequently embedded in OCT medium and stored at −80°C prior to sectioning. Sections were cut at 20 µm on a cryostat and collected on superfrost plus microslides (VWR Brand, Westchester, PA).

Immunohistochemistry

Primary antibodies used in this study are detailed in Table 1. Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies were obtained from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR) and used at a dilution of 1:250. Immunohistochemical labeling was performed using either indirect or direct immunofluorescence methods. Nonspecific binding was blocked with 10% normal horse serum in 0.1% Triton X-100, 1× PBS (pH 7.3) at room temperature for 30 minutes. Primary antibodies were diluted in 3% normal horse serum, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1× PBS (pH 7.3), and were applied overnight at 4°C. Six 10-minute washes were performed in 0.1% Triton X-100, 1× PBS (pH 7.3) with constant agitation. Secondary antibody incubation was performed for 1 hour at room temperature. Double-labeling experiments were performed by incubating cryosections in a mixture of primary antibodies, followed by a mixture of secondary antibodies. Triple-labeling experiments were performed by adding a mixture anti-Isl1 and anti-PKCα, as in double labeling, followed by a mixture of secondary antibodies. The third antibody, anti-Goα, required direct fluorescent labeling using a Zenon-labeling kit (for rabbit primary antibodies, Molecular Probes) because of the use of anti-PKCα concurrently. Following incubation with the directly conjugated primary, a 15-minute postfixation in 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde in 1× PBS (pH 7.3) at room temperature was performed to prevent transfer of conjugated fluorescent molecule to the other antibody on the sections from the same species. Slides were subsequently mounted in Mowiol mounting solution in preparation for fluorescent microscopy.

TABLE 1.

Antibodies

| Antiserum | Description of Immunogen |

Source/Cat. No. | Antibody Immunoblotting Specificity |

Immunohistochemistry Specificity |

Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse anti-calbindin | Purified bovine kidney calbindin-D-28 |

Sigma (St. Louis, MO) C 9848 | A single 28-kDa protein band (Gargini et al., 2007) |

Immunostaining prevented by preabsorption (Gargini et al., 2007) |

1:3,000 |

| Rabbit anti-Prox-1 | C-terminal 15 amino acids of mouse Prox1 |

Covance (Denver, PA) PRB- 238C |

Detects a single band of ~85 kDa in retinal lysate from adult mouse tissue |

Antibody staining coincides with in situ pattern (Beleky-Adams et al., 1997) |

1:5,000 |

| Goat anti-ChAT | Purified Choline acetyltransferase from human placenta |

Chemicon International (Temecula, CA) AB144P |

Detects a single 68–72- kDa band (Brunelli et al., 2005) |

Immunostaining abrogated following immunodepletion of cholinergic neurons (Kitabatake et al., 2003); retinal immunostaining consistent with reported patterns (Yoshida et al, 2001) |

1:100 |

| Mouse anti-Pax-6 | Recombinant chicken Pax6 |

DSHB #Pax6 | Antibody staining coincides with in situ pattern (Beleky-Adams et al., 1997) |

1:200 | |

| Mouse anti-Brn3a | Recombinant mouse Brn3a, truncated (amino acids 1–109) |

Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) # SC- 8429 |

Detects a 47–53-kDa band corresponding to recombinant full- length Brn3a (manufacturer’s tech. info.) |

Immunostaining pattern coincides with in situ data (Pan et al., 2005) |

1:500 |

| Mouse anti-Brn3b | Amino acids 360–410 of human Brn-3b |

Santa Cruz # SC-6026 | Detects a single band at ~50-kDa in mouse retinal extract |

Immunostaining pattern coincides with in situ data (Pan et al, 2005) |

1:200 |

| Mouse anti-Kip-I (p27) |

Recombinant mouse Kip-1 |

BD Transduction Laboratories (San Diego, CA) (610241) |

A single band of 27-kDa in a retinal lysate from adult mouse |

Inner nuclear staining pattern identical with previous description (Dyer and Cepko, 2001) |

1:200 |

| Sheep anti-Chx10 | Recombinant N- terminal amino acids 1–131 of human Chx10 conjugated to GST |

Exalpha Biologicals (Watertown, MA) |

46-kDa band in a retinal lysate from adult mouse tissue (manufacturer’s tech. info.) |

Antibody staining matches in situ pattern staining in the adult retina (Liu et al., 1994) |

1:1,000 |

| Rabbit anti-PKCα | C-terminal peptide of rat PKCα, amino acids 659–672 |

Sigma P4334 | A major ~81 kDa band, and a minor ~45 kDa band in a retinal lysate from adult mouse |

Labeling of typical rod bipolar cells, based on morphology and distribution (Gargini et al., 2007; Strettoi et al., 2002) |

1:7,000 |

| Rabbit anti-Goα | Purified native bovine Go alpha |

Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY) |

Detects a single ~40 kDa band in a retinal lysate from adult mouse |

Labeling of ON-bipolar cells confirmed by colocalization with PKCα, another ON- bipolar marker (Fig. 6) |

1:1,000 |

| Mouse anti-Islet-1/2 | Recombinant C- terminal portion of rat Islet-1, amino acids 178–349 |

DSHB # 39.4D5 | Reacts with a truncated 25 kDa Isl1 protein expressed in CHO cells but not in untransfected controls (Thor et al., 1991) |

Antibody staining matches in situ staining (Fig. 1) |

1:200 |

| Rabbit anti-β- galactosidase |

Beta galactosidase purified from E coli |

Chemicon # AB986 | No reactivity in retinal lysate from adult mouse tissue |

No staining in wildtype tissue; pattern of staining coincides with Isl1 immunohistochemistry and in situ patterns (Isl1-lacZ knockin) (Figs. 1 2) |

1:300 |

| Rabbit anti-recoverin | Recombinant human recoverin. |

Chemicon # AB5585 | A major band at 25 kDa, with minor bands at 50 and 90 kDa in retinal lysate from adult mouse |

Stains photoreceptors and cone bipolar cells (Milam et al., 1993) |

1:500 |

| Goat anti-NeuroD | NeuroD of mouse origin (G-20), amino acids 300- 334. |

Santa Cruz # SC-1086 (G-20) | Reacts with a single ~40-kDa band in retinal lysate from adult mouse tissue |

Antibody staining matches in situ staining (Morrow et al, 1999) |

1:200 |

Image acquisition and quantification

Images were captured at a resolution of 1024 × 1024 pixels. Green, red, and far-red fluorescence was scanned and imaged separately as gray-scale images and were later merged into RGB color space with Adobe Photoshop (San Jose, CA, v. 7.0 for PC). Colocalization counts were performed using 20-µm sections doubly labeled for Isl1 and PKCα. Analysis was confined to sections obtained within 0.5 mm of the optic disc. In terms of calculating Isl1-high and -low cells, a paintshop program was used to demarcate nuclei of all high-expressing cells. Subsequently, the same procedure was followed for demarcating nuclei of all low-expressing cells. The separate files containing demarcated low- and high-expressing cells were merged with a file in which the cell bodies of PKCα-positive was also demarcated using a paint feature. PKCα images were subsequently overlaid with images in which Isl1-high cells were demarcated, and separately overlaid with images in which Isl1-low cells were demarcated. Colocalization was judged by the close overlap of demarcated nuclei expressing either high or low amounts of Isl1, with cell bodies demarcated as PKCα-positive cells.

RESULTS

Isl1 expression in the mouse retina

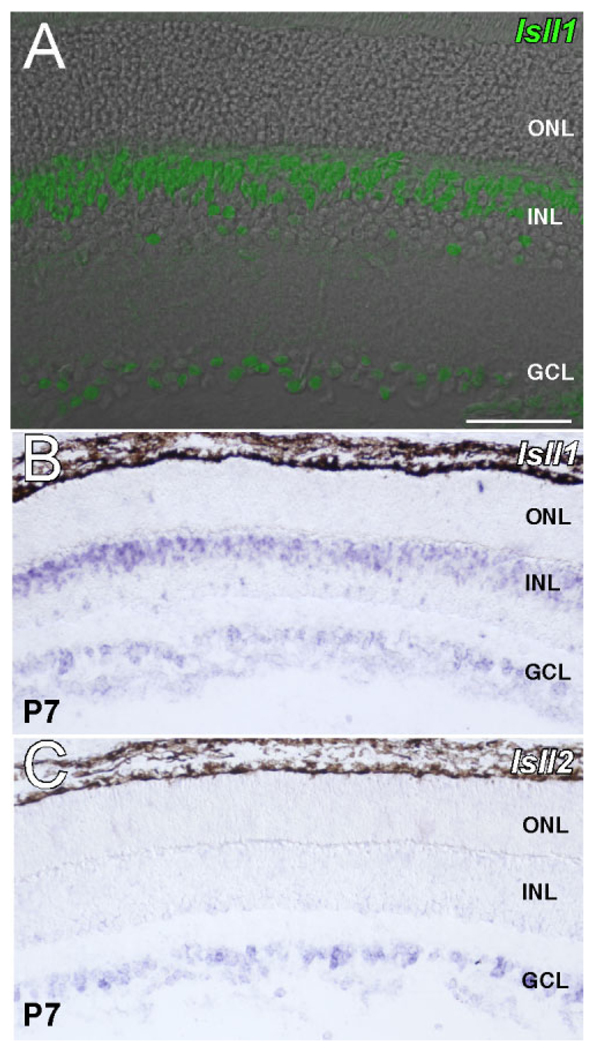

To determine the spatial expression pattern of Isl1 within the retina, an antibody recognizing the C-terminus of Isl1 and Isl2 (Isl1/2) was used. Adult mouse retina stained for Isl1/2 revealed staining in the GCL and multilaminar staining within the INL (Fig. 1). With respect to the INL, Isl1 immunoreactivity detected more cells along the outermost border of the INL, where bipolar cells reside, than the scattered array of Isl1/2-positive cells along the inner border of the INL, in the amacrine cell layer (ACL, Fig. 1). The orderly array of scattered Isl1-positive cells along the ACL has previously been shown to represent a mosaic of ChAT-positive amacrine cells in the rat retina (Galli-Resta et al., 1997). Further, in situ hybridization for Isl1 and Isl2 in postnatal eyes at P7 demonstrated that Isl2 transcript was restricted to the GCL, whereas Isl1 was expressed in both the GCL and within the INL at this age, although the same was observed at P14 (Fig. 1B,C; data not shown).

Fig. 1.

The expression of Isl1 in adult mouse retina. Confocal micrograph is overlaid on a phase contrast image of the same retinal section (A). Immunolabeling of Isl1 reveals it is expressed in the INL and GCL but not the ONL. Within the INL, a dense band of immunoreactive cells is present along the outermost INL border, while a more sparse array of immunoreactive cells are found along the innermost INL border, representing putative bipolar and amacrine cell nuclei, respectively. In situ hybridization for Isl1 at P7 demonstrates expression of Isl1 in the INL and GCL (B), while Isl2 expression is restricted to the GCL (C). INL, the inner nuclear layer; GCL, the ganglion cell layer; ONL, the outer nuclear layer. Scale bar = 50 µm.

Colocalization of Isl1 with cell-type markers for bipolar, amacrine, and ganglion cells

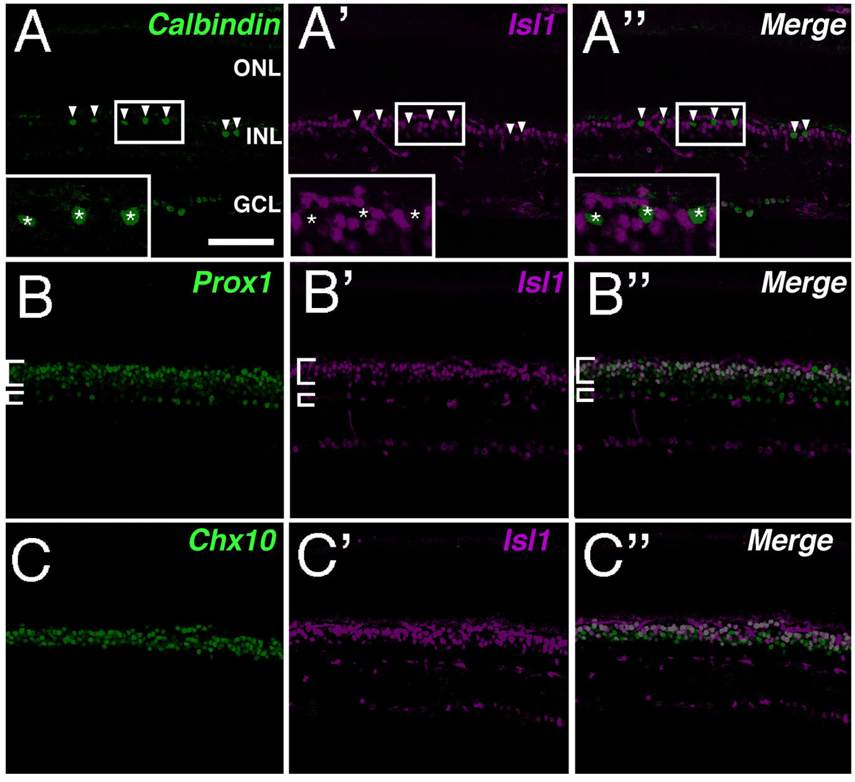

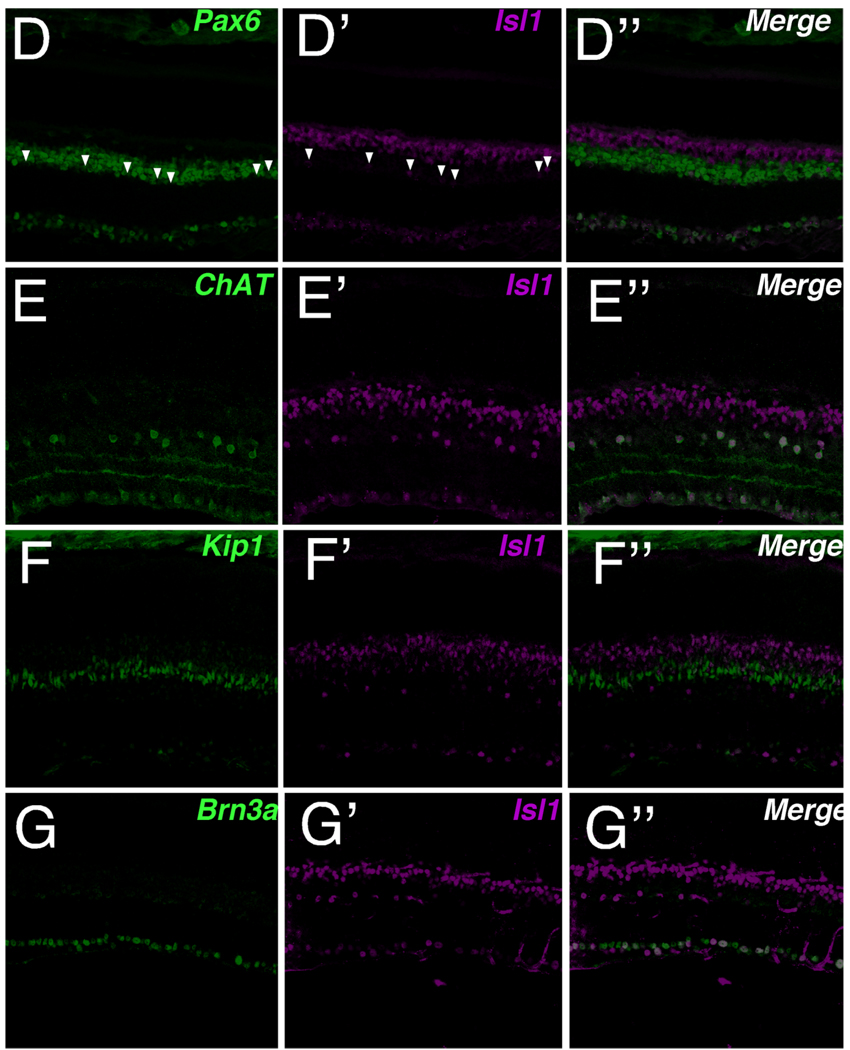

To assess comprehensively the Isl1-expressing cells in adult mouse retina, a range of cell-type markers for neurons and glia of the INL were utilized (Fig. 2). Calbindin, a mature horizontal cell marker in rodents (Pasteels et al., 1990; Pochet et al., 1991; Peichl and Gonzalez-Soriano, 1994), failed to colocalize with Isl1 (Fig. 2). Further, the absence of colocalization of Isl1 with Prox1, a marker for developing horizontal cells, at E15.5, 17.5, and 18.5 in mouse retina confirmed that Isl1 is not expressed in developing horizontal cells (data not shown). Prox1 highlights horizontal, bipolar, and AII amacrine cells in adult retina (Dyer et al., 2003). Its expression demonstrated a high degree of colocalization with Isl1 signal along the outermost border of the INL where Prox1 identifies bipolar cells (Fig. 2B,B″). Pax6 expression in postnatal mouse retina serves as a pan-amacrine marker (Marquardt et al., 2001). Its expression closely abuts the lower boundary of Isl1-expressing cells that were shown to colocalize with Prox1. Since anti-Pax6 and anti-Isl1 are both mouse antibodies (Table 1), colocalization of Pax6 was performed with lacZ in an Isl1-lacZ knockin mouse strain. The lacZ knockin recapitulated the expression pattern of Isl1 in the retina (Fig. 2D). The scattered cells expressing Isl1-lacZ along the innermost INL border colocalized with Pax6 and were consistent with an amacrine cell type (Fig. 2D, arrowheads). p27Kip1 in the adult mouse retina identifies the nuclei of Müller glia along a well-defined band slightly inferior to the outermost boundary of Pax6-expressing amacrine cells. No colocalization of Isl1 and p27Kip1 was detected (Fig. 2F,F″). Brn3a, a POU-domain transcription factor, identified a predominant fraction of retinal ganglion cell nuclei, of which a proportion was also positive for Isl1 expression (Fig. 2G,G"). Thus, in adult mouse retina, Isl1 is expressed in RGCs, bipolar, and amacrine cells but not in horizontal, photoreceptor, or Müller cells.

Fig. 2.

Double labeling of Isl1 and cell-type-specific markers in adult mouse retina. Confocal micrographs of retinal sections co-immunolabeled for Isl1 and various cell-type-specific markers. A,A″: Immunolabeling for Isl1 (A′) and the horizontal cell marker, calbindin (A; arrowheads, asterisks in inset). Isl1 immunoreactivity does not colocalize with calbindin (A″ arrowheads, asterisks in inset). B,B″: Immunolabeling for Isl1 (B′) and the bipolar cell marker, Prox1 (B). Isl1 colocalizes with Prox1 within the outermost portion of the INL (B,B″, larger bracket), whereas along the innermost INL, Isl1 and Prox1 do not colocalize (B,B″, smaller brackets). C,C″: Immunolabeling for Isl1 (C) and the bipolar cell marker, Chx10 (C). Isl1 colocalizes with Chx10 along the outermost INL, whereas Isl1-expressing cells located in the innermost INL and GCL do not express Chx10. D,D″: Immunolabeling for Isl1-LacZ (D′) and the amacrine cell marker, Pax6 (D). Isl1 immunolabeled cells along the innermost INL (arrowheads D,D″) are found within the region of amacrine cells labeled by Pax6 expression. At higher magnification, Pax6 and Isl1 immunoreactivity colocalize (data not shown). The Isl1-lacz reporter gene recapitulates Isl1 immunoreactivity. E,E″: Immunolabeling for Isl1 (E′) and the cholinergic amacrine cell marker, ChAT (E). ChAT-immunoreactive cells are uniformly colocalized with Isl1 (E″). F,F″: Immunolabeling for Isl1 (F′) and the Müller cell marker Kip1 (F) demonstrates that there is no colocalization of Isl1 and Kip1. G,G″: Immunolabeling for Isl1 (G′) and the RGC marker Brn3a (G) demonstrates that a proportion of retinal ganglion cells are immunoreactive for Isl1. Scale bar = 50 µm.

Colocalization of Isl1 with early markers of ganglion and amacrine cell differentiation

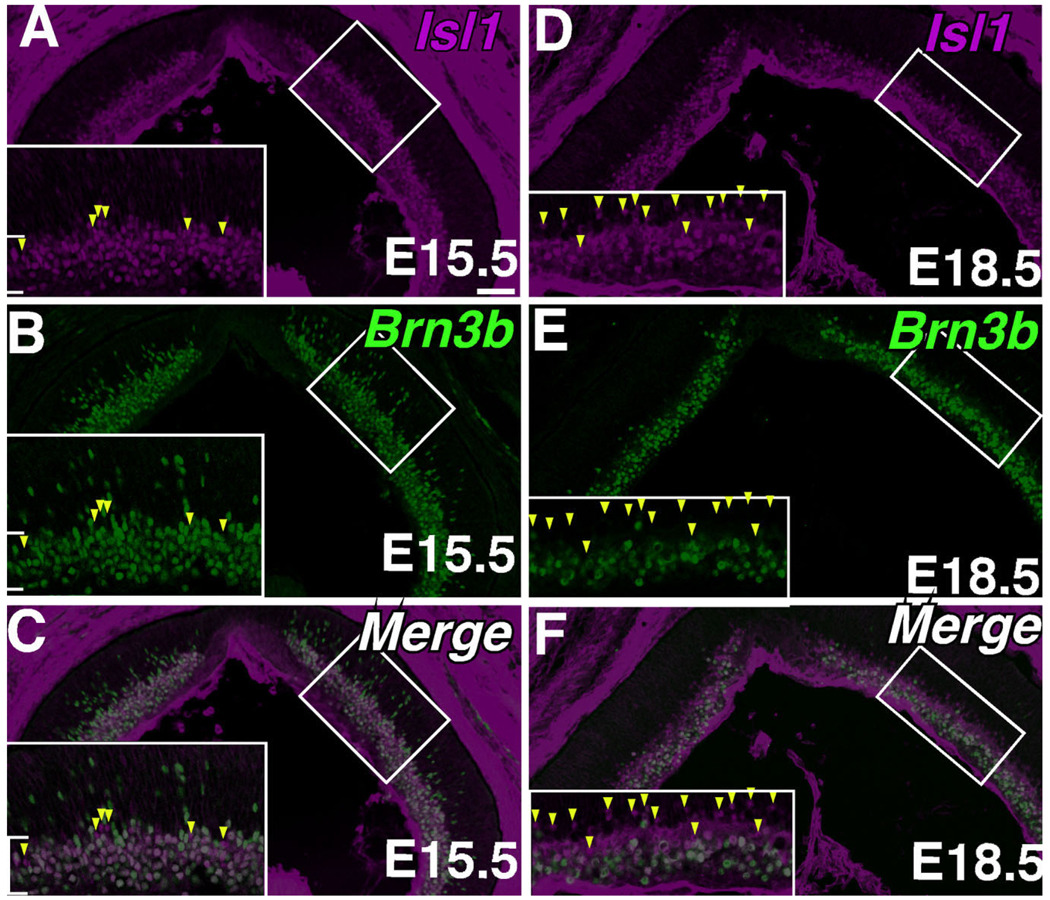

To determine whether Isl1 colocalizes with early markers of RGC development, co-immunolabeling with anti-Isl1 and anti-Brn3b was performed. Embryonic expression of Isl1 along the GCL overlapped completely with that of Brn3b, a marker of differentiating retinal ganglion cells (Fig. 3A–C, brackets). Outside the GCL, however, Brn3b was detected at higher intensities in more migrating RGCs than Isl1. As early as E15.5 there existed cells immunopositive for Isl1 but immunonegative for Brn3b (Fig. 3A–C, arrowheads). Many more such cells were detected at E17.5, when a lamina of Isl1 expression becomes evident (Fig. 3D–F, arrowheads).

Fig. 3.

Double immunolabeling of Isl1 and markers of developing RGCs. Confocal micrographs of horizontal sections of developing mouse retina immunolabeled for Isl1 (A,D) and the developing RGC marker Brn3b (B,E). A–C: Co-immunolabeling for Isl1 and Brn3b at E15.5. Most cells are doubly immunoreactive for Isl1 and Brn3b (brackets in inset), although several cells are singly immunoreactive towards Isl1 (arrowheads in inset). D–F: Co-immunolabeling for Isl1 and Brn3b at E18.5. The distinct array of Isl1 above the band of cells coexpressing both Brn3b and Isl1 represent amacrine cells in the nascent ACL. More cells immunoreactive for only Isl1 are detectable at this stage of development (arrowheads in bracket). Scale bar = 50 µm.

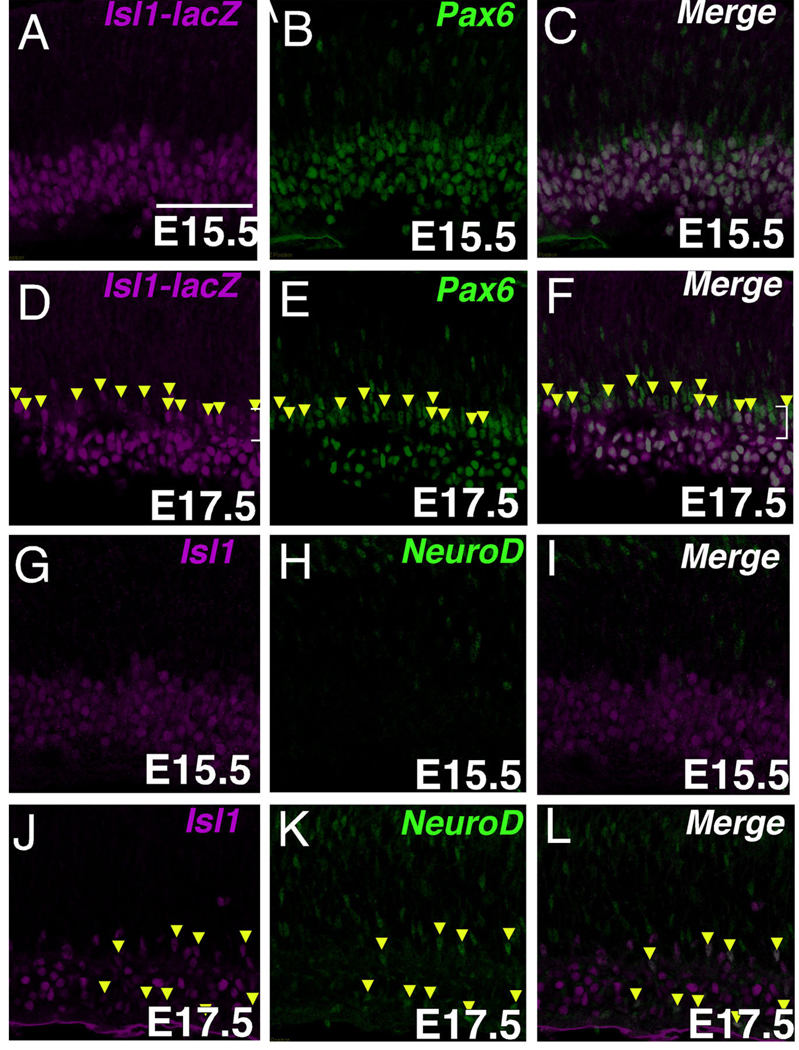

To determine whether expression of Isl1 found outside of the differentiating RGC pool represents expression within differentiating amacrine cells at embryonic stages, co-immunolabeling with anti-Isl1 and either anti-Pax6 or anti-NeuroD was carried out. Anti-Pax6 immunolabeling revealed the developing ACL, where the nascent ACL appears as a distinct layer of tightly packed, elongated nuclei positioned above the GCL at E17.5. Cells found within this nascent ACL layer that were immunopositive for Isl1 were uniformly immunopositive for Pax6 as well (Fig. 4D–F, arrowheads). Cells immunoreactive for both NeuroD and Isl1 were similarly observed at E17.5 but not during earlier timepoints (Fig. 4J–L, arrowheads, and G–I). Not all cells expressing Isl1 in the ACL expressed NeuroD (Fig. 4J – L). Taken together, prior to E15.5, Isl1 is predominantly an RGC marker and at E15.5 and later Isl1 is also expressed by non-RGCs.

Fig. 4.

The expression of Isl1 in developing amacrine cells. A–C: Confocal micrographs of a retinal section at E15.5 co-immunolabeled with Isl1-lacZ and Pax6. Cells double-immunopositive for Pax6 and Isl1 are within the ganglion cell layer. D–F: Confocal micrographs of mouse retina at E17.5 co-immunolabeled with Isl1-lacZ and Pax6. The nascent amacrine cell layer is visualized as a distinct lamina of Pax6-expressing cells slightly above the GCL. A proportion of these cells also express Isl1 (arrowheads). G–I: Confocal micrographs of a mouse retinal section at E15.5 co-immunolabeled with Isl1 and NeuroD. Isl1-immunoreactive cells are not colocalized with NeuroD. J–L: Confocal micrographs of a mouse retinal section at E17.5 co-immunolabeled with Isl1 and NeuroD. Several cells immunoreactive for NeuroD in the ganglion and amacrine cell layers (K, arrowheads), also express Isl1 (J,L arrowheads). Scale bar = 50 µm.

Isl1 as a pan-ON-center bipolar marker in mouse retina

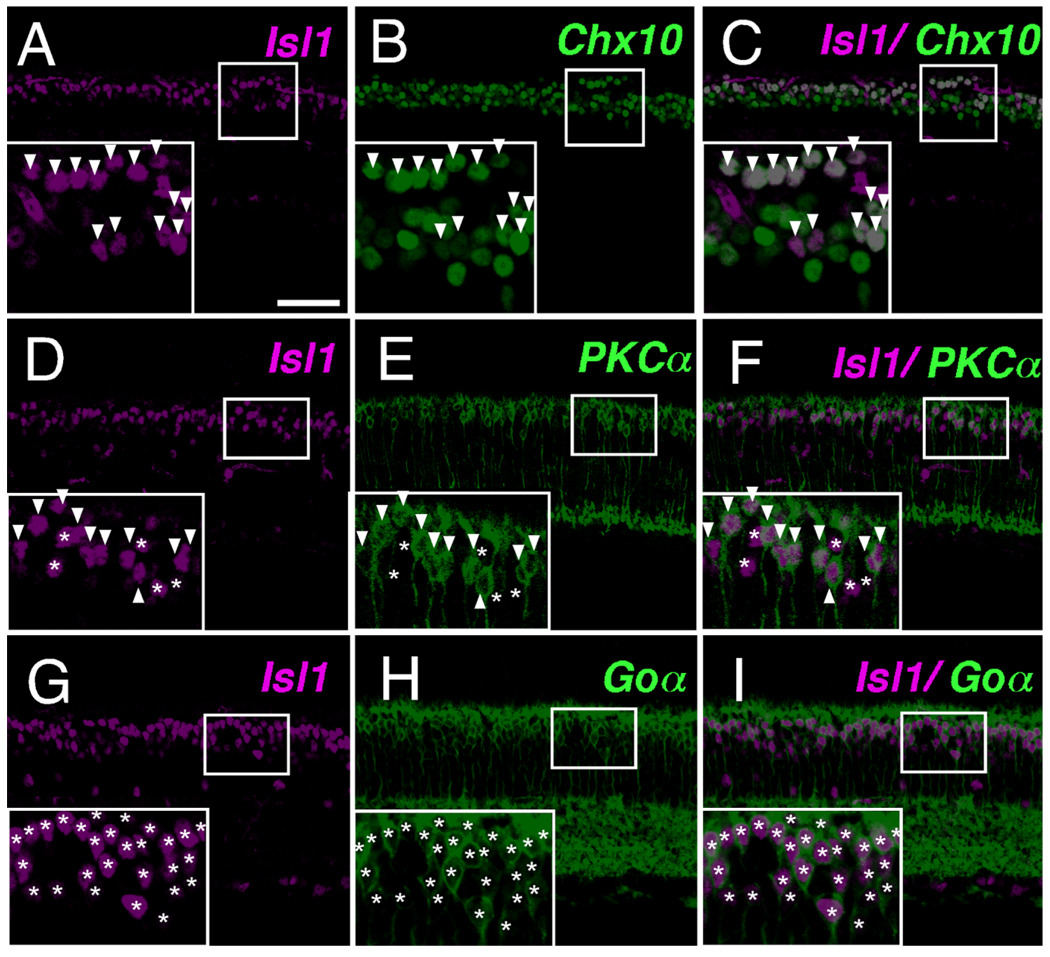

To establish the bipolar subtypes to which Isl1 expression is restricted in mouse retina, colocalization of Isl1 with known bipolar subtype markers was performed. Colocalization of Isl1 with Chx10, a pan-bipolar marker, demonstrated that Isl1-positive cells in the outermost portion of the INL were uniformly bipolar cells, as all Isl1 immunoreactive cells here were also Chx10-positive (Fig. 5A–C, arrowheads in inset). Colocalization of Isl1 with PKCα was subsequently undertaken. PKCα identifies rod bipolar cells (Cuenca et al., 1990; Haverkamp and Wassle, 2000; Haverkamp et al., 2003a). Isl1-expressing cells encompassed the PKCα pool of rod bipolar cells (Fig. 5D–F, arrowheads in inset). However, there existed Isl1-immunoreactive cells that were non-PKCα-immunoreactive (Fig. 5D–F, asterisks in inset). Goα identifies ON-bipolar cells, which include rod bipolars and ON-cone bipolar cells (Vardi et al., 1993; Vardi, 1998; Haverkamp and Wassle, 2000). When colocalized with Goα, there was a complete colocalization of Isl1 and Goα (Fig. 5G–I, asterisks in inset), indicating that all Isl1-positive bipolar cells are the ON type.

Fig. 5.

Isl1 expression in mature bipolar cells. A–C: Confocal micrographs of sections of adult mouse retina co-immunolabeled with Isl1 (A, arrowheads in inset) and the pan-bipolar marker Chx10 (B). Cells immunoreactive for Isl1 are colocalized with Chx10 (C, arrowheads in inset), and are skewed to the upper portion of Chx10-expressing bipolar cells. D–F: Confocal micrographs of sections of adult mouse retina co-immunolabeled with Isl1 and the rod bipolar cell marker PKCα. Cells expressing PKCα (E, arrowheads in inset) also express Isl1 (F, arrowheads in inset). There also exists cells that are PKCα-nonimmunoreactive (E, asterisks in inset) but are Isl1-immunoreactive (F, asterisks in inset). G–I: Confocal micrographs of sections of adult mouse retina co-immunolabeled with Isl1 and the pan-ON-bipolar cell marker Goα. Cells expressing Goα (H, asterisks in inset) also express Isl1 of varying intensities (G,I, asterisks in inset). No cell in this portion of the inner nuclear layer are found to express only Isl1 and not Goα. Scale bar = 50 µm.

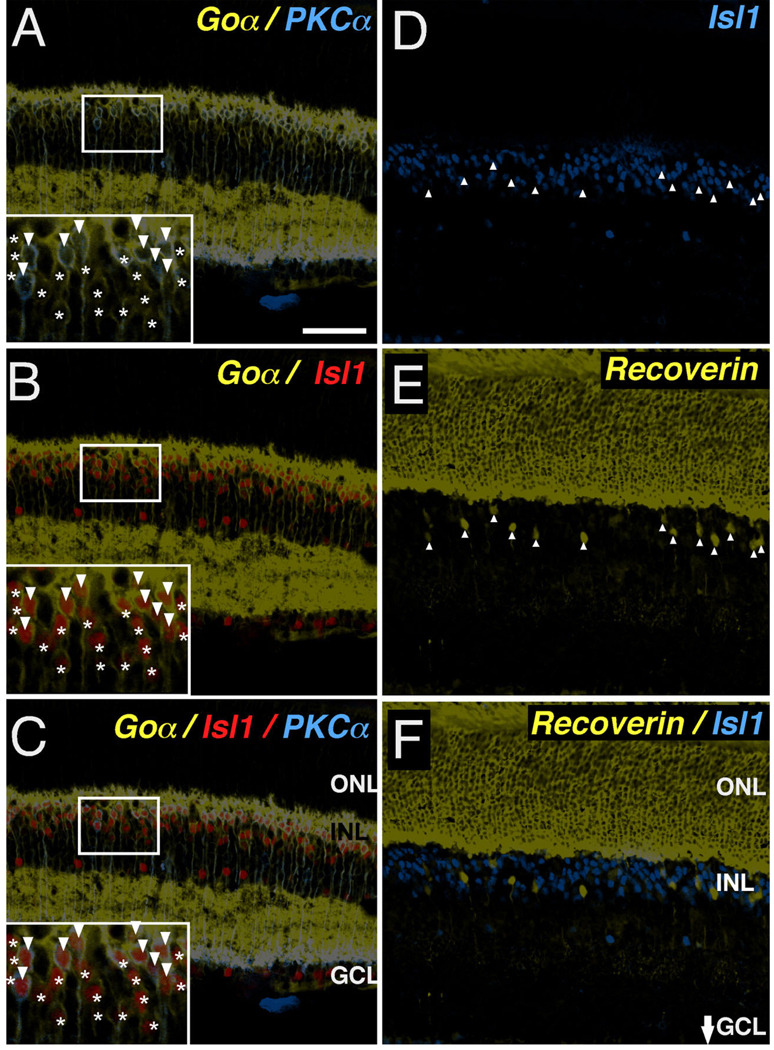

To test further whether Isl1 expression correlates with a particular functional categorization of bipolar neurons, such as cells with an ON-center physiology, further co-immunolabeling experiments were performed. The ON-center-responding cells are comprised of rod bipolar and ON-cone bipolar cells that are distinguished by immunolabeling using anti-PKCα and anti-Goα. While rod bipolar cells were double immunopositive for Goα and PKCα (Fig. 6A–C, arrowheads in inset), ON-cone bipolar cells were immunopositive for Goα only (Fig. 6A–C, asterisks in inset). The observation of Goα-positive/Isl1-positive/PKCα-negative cells confirmed that Isl1 is expressed in adult ON-cone bipolar cells in the mouse retina (Fig. 6C, asterisks in inset). Careful examination showed that the Isl1-expressing cells in the outermost INL either colocalized with Goα and PKCα, or Goα alone (Fig. 6C, inset). To exclude the possibility that Isl1 expression exceeds the ON-bipolar cell pool, we co-immunolabeled retina sections with anti-Isl1 and anti-recoverin. Anti-recoverin is a marker specific for OFF-cone bipolar cells (Cheng et al., 2005). No recoverin-positive cells expressed Isl1 (Fig. 6D – F). Hence, Isl1 expression in the adult mouse retina corresponds to bipolar cell types with ON-center physiologic responses, regardless of class of photoreceptor connectivity (i.e., rod vs. cone bipolar cells).

Fig. 6.

Subtype-specific expression of Isl1 in ON-bipolar cells of mature retina. A–C: Confocal micrographs of sections of adult mouse retina co-immunolabeled for Goα (A–C, asterisks and arrowheads in insets), PKCα (A,C, arrowheads in insets) and Isl1 (B,C, asterisks and arrowheads in insets). Isl1 expression is present in both rod bipolar cells expressing PKCα and Goα (A,C, arrowheads in insets) as well as ON-cone bipolar cells expressing Goα alone (C, asterisks in insets). D–F: Confocal micrographs of sections of adult mouse retina co-immunolabeled for an OFF-cone bipolar marker, recoverin (E,F) and Isl1 (D,F). There is no colocalization between recoverin and Isl1 (F). Scale bar = 50 µm.

High- and low-Isl1-expressing cells differentially colocalized with rod bipolar cells

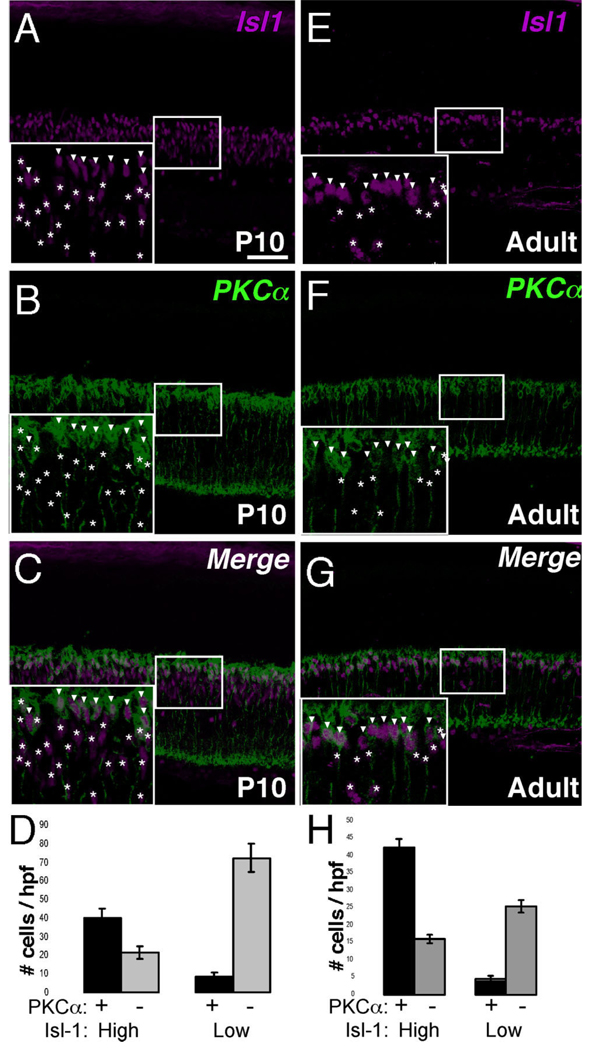

The polarization in Isl1 expression to the outermost region of the INL is consistent with a report demonstrating that Isl1 identifies ON-center bipolar cells in monkey and human retina. As in monkey and human retina, Isl1-expressing cells outnumber those of the PKCα pool (Haverkamp et al., 2003b). Further, it became clear that the intensity of Isl1 expression was not equal in all nuclei and that there existed Isl1-high (arrowheads) and Isl1-low-expressing (asterisks) cells (Fig. 7A,E, inserts). To evaluate whether rod bipolar cells are more likely to co-segregate with one versus the other subpopulation of Isl1-expressing cells, the degree of colocalization of PKCα with Isl1 low- and high-expressing cells was evaluated (Fig. 7D,H). Isl1-high cells were about four times more likely to colocalize with PKCα-positive cells than to not colocalize in P10 retina (Fig. 7C, insets), while Isl1-low cells were 3–4 times less likely to colocalize with PKCα in P10 retina (Fig. 7D). A similar observation was made in adult retina (Fig. 7G, H). Thus, despite extending beyond the PKCα-positive pool, cells expressing higher levels of Isl1 segregate more frequently with rod bipolar cells than Isl1-low cells.

Fig. 7.

Segregation of Isl1-high expressing bipolar cells with the PKCα-positive rod bipolar subtype. A–C: Confocal micrographs of sections of P10 retina co-immunolabeled for Isl1 and PKCα. Isl1-high expressing cells (A, arrowheads in inset) and Isl1-low expressing cells (A, asterisks in inset) are scored independently and the degree of colocalization of high and low cells with PKCα (B) is scored. PKCα-immunoreactive bipolar cells are more likely to colocalize with a cell expressing relatively higher levels of Isl1 (C, arrowheads vs. asterisks in inset; quantification in D). E–G: Confocal micrographs of sections of adult retina co-immunolabeled for Isl1 and PKCα. Isl1-high expressing cells (E, arrowheads in inset) and Isl1-low expressing cells (E, asterisks in inset) are scored independently, and the degree of colocalization of high and low cells with PKCα (F) is scored. PKCα-immunoreactive cells are more likely to colocalize with a cell expressing relatively higher levels of Isl1 (G, arrowheads vs. asterisks in inset; quantification in H). Scale bar = 50 µm.

Early expression of Isl1 in developing bipolar cells

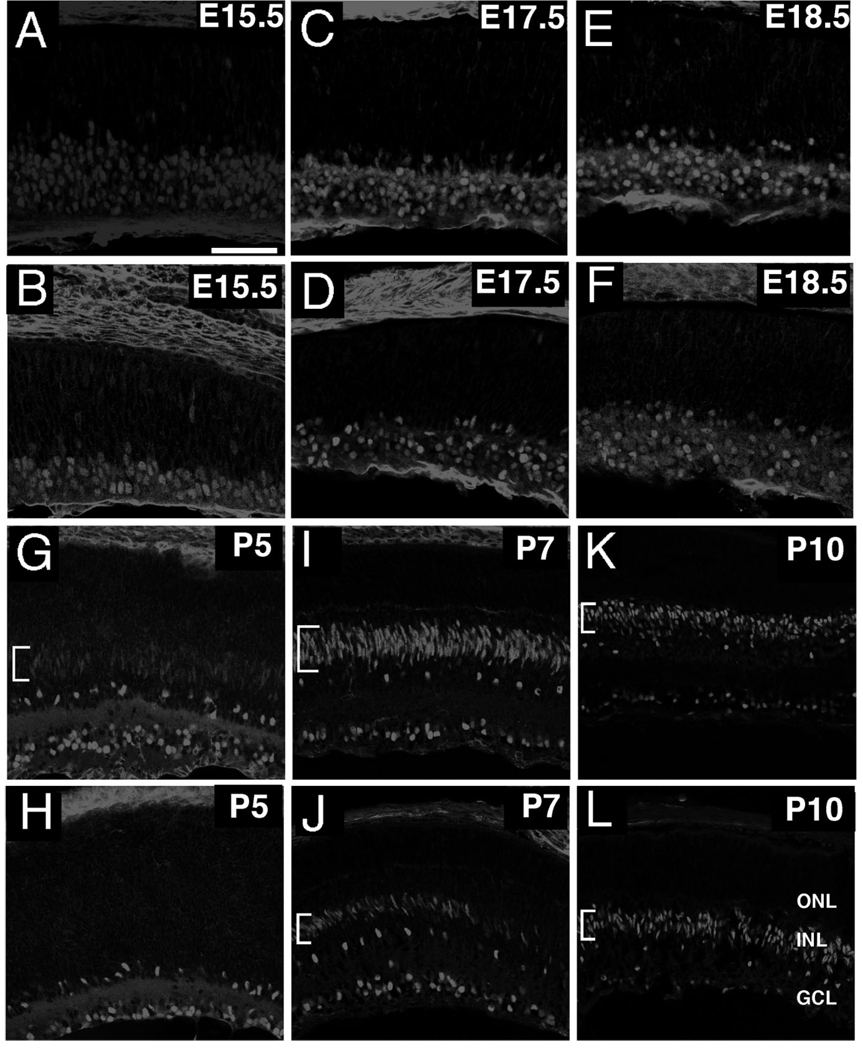

The restriction of Isl1 to subpopulations of bipolar interneurons raises the possibility that Isl1 is involved in specifying bipolar subtypes. To determine whether Isl1’s temporal expression profile is compatible with a role in bipolar differentiation, the expression of Isl1 was assessed in presumptive bipolar cells at timepoints spanning bipolar development, as judged by the laminar position of Isl1-immunoreactive cells. The peak incorporation of bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) in bipolar cell progenitors occurred at P3, with maturation occurring in the days thereafter (Young, 1985). The first detection of Isl1 signal in presumptive bipolar cells occurred at P5 in the spindle-shaped nuclei, indicative of recently migrated bipolar cells (Fig. 8G, bracket). At P5, Isl1 was undetectable in peripheral retina, which is consistent with the delay in differentiation observed in the peripheral retina compared to the central retina (Young, 1985). By P7, Isl1 signal was dramatically increased within central retina, where nuclei still display spindle-shaped morphologies, and the signal commenced in the peripheral retina in a central-to-peripheral gradient (Fig. 8I,J, brackets). At P10, Isl1 expression persisted in central retina, where Isl1-positive cells acquired a more rounded nuclear morphology, and expanded further in the peripheral retina (Fig. 8K,L, brackets).

Fig. 8.

Confocal micrographs of developing mouse retina immunolabeled for Isl1. A,B: Sections of E15.5 retina immunolabeled for Isl1 in central (A) and peripheral (B) retina. Expression of Isl1 is predominant in the developing GCL. C–F: Sections of E17.5 (C,D) and E18.5 (E,F) retina immunolabeled for Isl1 in central (C,E) and peripheral retina (D,F). Expression of Isl1 is maintained in the GCL, but expands into the nascent ACL. This layer corresponds to the distinct lamina of Isl1-expressing cells shown most clearly in central retina (C,E). G,H: Sections of P5 retina immunolabeled for Isl1 in central (G) and peripheral (H) retina. Expression of Isl1 in the presumptive bipolar region of the INL commences in central retina at this stage (G, bracket), while peripheral retina is devoid of Isl1 immunolabeling in this region. I–L: Sections of P7 (I–L) and P10 (K,L) retinas immunolabeled for Isl1 in central (I,K) and peripheral retina (J,L). The expression of Isl1 in the presumptive bipolar cell layer (I–L, brackets) continues to expand into peripheral retina (J,L, brackets). Note the elongated nuclei in recently migrated bipolar cells in central retina at P7 (I, brackets) and peripheral retina at P7 and P10 (J,L brackets; respectively). Scale bar = 50 µm.

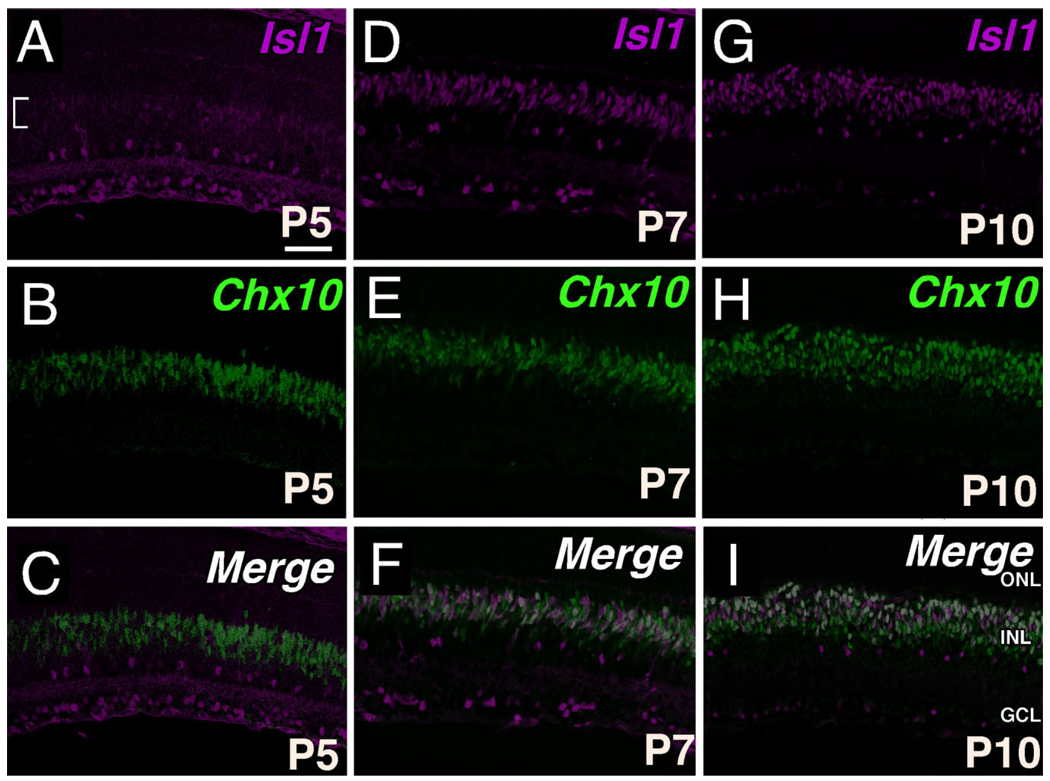

Evolving coexpression patterns of Isl1 and Chx10 in differentiating bipolar neurons

To evaluate the spatiotemporal relationship between Isl1 and the INL specifier, Chx10 (Hatakeyama et al., 2001), colocalization of Isl1 and Chx10 was undertaken. The nascent pattern of Isl1 expression at P5, although spatially overlapping with Chx10-expressing cells, was much less robust than the Chx10 signal, suggesting that Isl1 expression follows that of Chx10 (Fig. 9A–C, bracket in A). By P7, colocalization of Isl1 and Chx10 was more appreciable and revealed cells that coexpress Isl1 and Chx10 at high levels (white), or display either predominantly Isl1 expression (green) or Chx10 expression (magenta) (Fig. 9F). Further analysis at P10 indicated that cells displaying a high degree of coexpression of Isl1 and Chx10 consolidated to form a band of cells predominantly located along the outermost border of the INL, whereas this population of coexpressing cells had a more dispersed distribution at P7 (compare Fig. 9F,I). Despite the substantial proportion of Isl1 expression within differentiating bipolar neurons, Isl1 expression became restricted to the upper portion of Chx10-expressing cells (Fig. 9I), with this INL organization occurring sometime between P7 and P10.

Fig. 9.

Coexpression of Isl1 and Chx10 in developing bipolar cells. A–C: Confocal micrographs of sections of P5 central retina co-immunolabeled for Isl1 (A) and Chx10 (B). The nascent Isl1 expression in presumptive bipolar cells (A, bracket) spatially overlaps with the domain of Chx10 expression (C). D–F: Confocal micrographs of sections of P7 central retina co-immunolabeled for Isl1 (D) and Chx10 (E). Colocalization of Isl1 and Chx10 at this stage shows that double immunopositive cells (F, white) are randomly interspersed throughout the pool of developing bipolar cells. G–I: Confocal micrographs of sections of P10 central retina co-immunolabeled for Isl1 (G) and Chx10 (H). Colocalization of Isl1 and Chx10 is most notable at the upper boundary of Chx10 expression domain. Note the transition of coexpressing cells from a random assortment in P7 (F) to a lamina (I) of presumptive ON-bipolar cells. Scale bar = 50 µm.

DISCUSSION

The current study sought to first establish the precise cell types to which Isl1 is localized in the adult mouse retina, and work backwards to analyze Isl1’s expression developmentally in the corresponding cells of embryonic and early postnatal retinas. Its spatiotemporal expression pattern spans the differentiation of three major neuronal classes, bipolar, amacrine, and ganglion cells, in the developing retina. Our findings also identify Isl1 as a marker for ON-bipolar cells, a restricted bipolar cell type in the mouse retina, and demonstrate Isl1’s early expression in developing bipolar and amacrine cells. Within the ON-bipolar cells we identified Isl1-high and -low cells, and demonstrated that Isl1-high cells segregate more with rod bipolar cells.

Isl1 is expressed by developing amacrine cells

While the developing ACL is readily distinguishable using Pax6 immunolabeling, expression of Pax6 by differentiating RGCs obscures identification of differentiating amacrine cells within the GCL, the displaced amacrine cells. Co-immunolabeling with anti-NeuroD and anti-Isl1 avoids the difficulty in identifying displaced amacrine cells, as anti-NeuroD serves to label differentiating amacrine cells but not RGCs. As early as E15.5, expression of Isl1 exceeds that of the developing RGC pool. These cells likely represent presumptive cholinergic amacrine cells (Galli-Resta et al., 1997). Isl1 expression is shown to colocalize with ChAT in adult rat retina and is partially excluded from retrogradely labeled RGCs from early postnatal retinas (Galli-Resta et al., 1997; Gunhan et al., 2002). In the current work, we demonstrated the emergence of Isl1-positive cells outside of the pool of RGCs embryonically and confirmed their amacrine identity using Pax6 and NeuroD. Thus, Isl1 appears to mark presumptive cholinergic amacrines earlier than previously appreciated. The role of Isl1 in cholinergic amacrine cell differentiation is unknown, but may range from regulating marker gene expression (ChAT) to negatively regulating cell death. The proposed importance for Isl1 in other cholinergic interneuron populations suggests that Isl1’s potential role in cholinergic interneurons may have a common mechanism in disparate anatomical sites (Wang, 2001; Zhao et al., 2003).

In several species, including monkey, human, and zebrafish, Isl1 is expressed in horizontal cells (Haverkamp et al., 2003b; Shkumatava and Neumann, 2005). However, the absence of Isl1 and calbindin co-immunolabeling in our study shows that Isl1 is not expressed by horizontal cells in mouse retina. Consistently, analysis of horizontal cell types in rodent retina found that, unlike other species possessing two morphological classes of horizontal cells, the axonless Type A and the axon-bearing Type B, mouse retinas contain only the Type B class (Peichl and Gonzalez-Soriano, 1994). Perhaps Isl1 is expressed only by Type A horizontal cells in monkey, human, and zebrafish retinas, but not in the Type B horizontal cells that are found in mouse retina.

Isl1 as a pan-ON-bipolar cell marker

The restriction of Isl1 expression to the ON-bipolar cell pathway in the mouse retina implies its role in the establishment and maintenance of these ON-bipolar cells. Isl1 expression in bipolar cells has been explored in monkey and human retina and is shown in rod bipolar cells and ON-bipolar cells in general without a clear demonstration that Isl1 is expressed by ON-cone bipolars (Haverkamp et al., 2003b), as is conclusively demonstrated for mouse retina in the present study by labeling concurrently for Isl1, Goα, and PKCα (Fig. 6). Furthermore, because of the ease of assessing the spatiotemporal expression in mouse retina, we showed that Isl1 expression by ON-bipolar cells likely originated early during bipolar differentiation (Figs. 8, 9). Although recoverin does not encompass all OFF-cone bipolar cells in the mammalian retina, the restriction of Isl1-expressing bipolar cells to the pool of Goα-positive cells argues for its specificity for only ON-center cells in adult mouse retina. On the other hand, without analyzing the precise lineage of Isl1-expressing cells throughout bipolar development, such as by analyzing retinas in which the Isl1 lineage is identified in a reporter mouse line, we cannot conclude that Isl1 expression is never expressed in the OFF-type bipolar cell lineage. Other transcription factors specific to subtypes of developing bipolar cells have been identified, such as Vsx1 (Chow et al., 2004), Bhlhb4 (Bramblett et al., 2004), Irx5 (Cheng et al., 2005), and Bhlhb5 (Feng et al., 2006). Bhlhb4 encompasses a sub-population of ON-bipolar cells, the rod bipolars. Vsx1 is expressed in OFF bipolar cells and is required for the normal light-evoked responses of OFF ganglion cells, as well as the expression of several mature markers of OFF-cone bipolar cells (Chow et al., 2004). The expression of Irx5, an Iroquois homeodomain transcription factor, is restricted to a slightly different subset of OFF-cone bipolar cells, and is also important for the expression of several mature markers of OFF-cone bipolar cells (Cheng et al., 2005). Unlike Isl1, these factors do not seem to encompass the entire population of ON or OFF bipolar cells, although markers that identify the entire pool of OFF-bipolar cells do not seem to exist (Chow et al., 2004).

Segregation of ON-bipolar cells by the relative intensity of Isl1 expression

The relative intensity differences in Isl1 immunoreactivity was found to segregate the pool of ON-bipolar cells, where PKCα-immunopositive rod bipolar cells were found more likely to colocalize with Isl1-high cells than with Isl1-low cells (Fig. 7). Thus, despite Isl1 colocalizing with both rod bipolar cells and ON-cone bipolar cells, which collectively comprise the entire pool of ON bipolar cells, a further diversification of this pool may be based on the amount of Isl1 expressed. Similarly, Irx5 is expressed at different levels in different bipolar subtypes and is necessary for cone bipolar development (Cheng et al., 2005). Irx5-low cells colocalize with Type 2 OFF-cone bipolar cells while Irx5-high cells colocalize with Type 3 OFF-cone bipolar cells. The functional importance of different Isl1 expression levels in different bipolar subtypes is unknown. However, decreasing the levels of Isl1 expression in bipolar cells by generating hypomorphic alleles may shift the fates of ON-bipolar cells from rod bipolars to ON-cone bipolars, for example.

Isl1 and Chx10 spatiotemporal coexpression patterns depict bipolar subtype lamination

In mouse retinogenesis the transcription factors Chx10, Mash1, and Math3 have all been shown to be necessary for the development of bipolar cells, either singly (Chx10 and Mash1) or in combination with each other (Mash1 and Math3). Nevertheless, less is known about how different subtypes of bipolar cells are generated (Hatakeyama et al., 2001). Among candidate genes responsible for bipolar subtype specification are transcription factors such as Vsx1, Bhlhb5, Bhlhb4, and Irx5, which are expressed sufficiently early and in a restricted subset of bipolar interneurons. In this study we demonstrate that the onset of Isl1 expression at P5 in presumptive bipolar cells occurs prior to important differentiation and morphological milestones in bipolar cell maturation (Bramblett et al., 2004). A recent report demonstrating the early expression of Isl1 in the INL of chicken retina is consistent with our results (Edqvist et al., 2006). Furthermore, the Isl1+ ON-bipolar cell bodies are organized in sublaminae closer to horizontal cells, consistent with the previously identified sublaminar localization of ON-bipolar cells (Haverkamp et al., 2003b). The Isl1 and Chx10 coexpression domains exist before a clear organization of ON-bipolar cell bodies can be appreciated, and persists after such organization is established (Fig. 9). Thus, coexpression patterns of Isl1 and Chx10 may be useful in identifying subtle lamination defects within the inner nuclear layer.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank the members of the Gan Laboratory for helpful discussions and technical assistance.

Grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health (NIH); Grant number: EY013426 (to L.G.); Grant sponsor: Research to Prevent Blindness (medical student fellowship to Y.E.); Grant sponsor: NIH; Grant number: Training Grant NIH T32 NS07489 (to Y.E.); Grant sponsor: Research to Prevent Blindness challenge grant to the Department of Ophthalmology at the University of Rochester.

LITERATURE CITED

- Beleky-Adams T, Tomarev S, Li HS, Ploder L, McInnes RR, Sundin O, Adler R. Pax-6, Prox 1, and Chx10 homeobox gene expression correlates with phenotypic fate of retinal precursor cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997;38:1293–1303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramblett DE, Pennesi ME, Wu SM, Tsai MJ. The transcription factor Bhlhb4 is required for rod bipolar cell maturation. Neuron. 2004;43:779–793. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SP, Masland RH. Costratification of a population of bipolar cells with the direction-selective circuitry of the rabbit retina. J Comp Neurol. 1999;408:97–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunelli G, Spano P, Barlati S, Guarneri B, Barbon A, Bresciani R, Pizzi M. Glutamatergic reinnervation through peripheral nerve graft dictates assembly of glutamatergic synapses at rat skeletal muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:8752–8757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500530102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepko CL, Austin CP, Yang X, Alexiades M, Ezzeddine D. Cell fate determination in the vertebrate retina. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:589–595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.2.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng CW, Chow RL, Lebel M, Sakuma R, Cheung HO, Thanabalasing-ham V, Zhang X, Bruneau BG, Birch DG, Hui CC, McInnes RR, Cheng SH. The Iroquois homeobox gene, Irx5, is required for retinal cone bipolar cell development. Dev Biol. 2005;287:48–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow RL, Volgyi B, Szilard RK, Ng D, McKerlie C, Bloomfield SA, Birch DG, McInnes RR. Control of late off-center cone bipolar cell differentiation and visual signaling by the homeobox gene Vsx1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:1754–1759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306520101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuenca N, Fernandez E, Kolb H. Distribution of immunoreactivity to protein kinase C in the turtle retina. Brain Res. 1990;532:278–287. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91770-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer MA, Cepko CL. p27Kip1 and p57Kip2 regulate proliferation in distinct retinal progenitor cell populations. J Neurosci. 2001;21:4259–4271. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-12-04259.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer MA, Livesey FJ, Cepko CL, Oliver G. Prox1 function controls progenitor cell proliferation and horizontal cell genesis in the mammalian retina. Nat Genet. 2003;34:53–58. doi: 10.1038/ng1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edqvist PH, Myers SM, Hallbook F. Early identification of retinal subtypes in the developing, pre-laminated chick retina using the transcription factors Prox1, Lim1, Ap2alpha, Pax6, Isl1, Isl2, Lim3 and Chx10. Eur J Histochem. 2006;50:147–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Famiglietti EV. ‘Starburst’ amacrine cells and cholinergic neurons: mirror-symmetric ON and OFF amacrine cells of rabbit retina. Brain Res. 1983;261:138–144. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)91293-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng L, Xie X, Joshi P, Yang Z, Shibasaki K, Chow R. Requirement for Bhlhb5 in the specification of amacrine and cone bipolar subtypes in mouse retina. Development. 2006;133:4815–4825. doi: 10.1242/dev.02664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galli-Resta L, Resta G, Tan SS, Reese BE. Mosaics of islet-1-expressing amacrine cells assembled by short-range cellular interactions. J Neurosci. 1997;17:7831–7838. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-20-07831.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gargini C, Terzibasi E, Mazzoni F, Strettoi E. Retinal organization in the retinal degeneration 10 (rd10) mutant mouse: a morphological and ERG study. J Comp Neurol. 2007;500:222–238. doi: 10.1002/cne.21144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunhan E, Choudary PV, Landerholm TE, Chalupa LM. Depletion of cholinergic amacrine cells by a novel immunotoxin does not perturb the formation of segregated on and off cone bipolar cell projections. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2265–2273. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-06-02265.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatakeyama J, Tomita K, Inoue T, Kageyama R. Roles of homeobox and bHLH genes in specification of a retinal cell type. Development. 2001;128:1313–1322. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.8.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haverkamp S, Wassle H. Immunocytochemical analysis of the mouse retina. J Comp Neurol. 2000;424:1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haverkamp S, Ghosh KK, Hirano AA, Wassle H. Immunocytochemical description of five bipolar cell types of the mouse retina. J Comp Neurol. 2003a;455:463–476. doi: 10.1002/cne.10491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haverkamp S, Haeseleer F, Hendrickson A. A comparison of immunocytochemical markers to identify bipolar cell types in human and monkey retina. Vis Neurosci. 2003b;20:589–600. doi: 10.1017/s0952523803206015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobert O, Westphal H. Functions of LIM-homeobox genes. Trends Genet. 2000;16:75–83. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01883-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitabatake Y, Hikida T, Watanabe D, Pastan I, Nakanishi S. Impairment of reward-related learning by cholinergic cell ablation in the striatum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:7965–7970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1032899100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb H, Famiglietti EV. Rod and cone pathways in the inner plexiform layer of the cat retina. Science. 1974;186:47–49. doi: 10.1126/science.186.4158.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Mo Z, Yang X, Price SM, Shen MM, Xiang M. Foxn4 controls the genesis of amacrine and horizontal cells by retinal progenitors. Neuron. 2004;43:795–807. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu IS, Chen JD, Ploder L, Vidgen D, van der Kooy D, Kalnins VI, McInnes RR. Developmental expression of a novel murine homeobox gene (Chx10): evidence for roles in determination of the neuroretina and inner nuclear layer. Neuron. 1994;13:377–393. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90354-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquardt T, Ashery-Padan R, Andrejewski N, Scardigli R, Guillemot F, Gruss P. Pax6 is required for the multipotent state of retinal progenitor cells. Cell. 2001;105:43–55. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00295-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masland RH. Neuronal diversity in the retina. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2001;11:431–436. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00230-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masland RH. The many roles of the starburst amacrine cells. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:395–396. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milam AH, Dacey DM, Dizhoor AM. Recoverin immunoreactivity in mammalian cone bipolar cells. Vis Neurosci. 1993;10:1–12. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800003175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo Z, Li S, Yang X, Xiang M. Role of the Barhl2 homeobox gene in the specification of glycinergic amacrine cells. Development. 2004;131:1607–1618. doi: 10.1242/dev.01071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow EM, Furukawa T, Lee JE, Cepko CL. NeuroD regulates multiple functions in the developing neural retina in rodent. Development. 1999;126:23–26. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson R, Kolb H. Synaptic patterns and response properties of bipolar and ganglion cells in the cat retina. Vision Res. 1983;23:1183–1195. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(83)90032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson R, Famiglietti EV, Kolb H. Intracellular staining reveals different levels of stratification for on-center and off-center ganglion cells in the cat retina. J Neurophysiol. 1978;4:427–483. doi: 10.1152/jn.1978.41.2.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan L, Yang Z, Feng L, Gan L. Functional equivalence of Brn3 POU-domain transcription factors in mouse retinal neurogenesis. Development. 2005;132:703–712. doi: 10.1242/dev.01646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasteels B, Rogers J, Blachier F, Pochet R. Calbindin and calretinin localization in retina from different species. Vis Neurosci. 1990;5:1–16. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800000031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peichl L, Gonzalez-Soriano J. Morphological types of horizontal cell in rodent retinae: a comparison of rat, mouse, gerbil, and guinea pig. Vis Neurosci. 1994;11:501–517. doi: 10.1017/s095252380000242x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaff SL, Mendelsohn M, Stewart CL, Edlund T, Jessell TM. Requirement for LIM homeobox gene Isl1 in motor neuron generation reveals a motor neuron-dependent step in interneuron differentiation. Cell. 1996;84:309–320. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80985-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pochet R, Pasteels B, Seto-Ohshima A, Bastianelli E, Kitajima S, Van Eldik LJ. Calmodulin and calbindin localization in retina from six vertebrate species. J Comp Neurol. 1991;314:750–762. doi: 10.1002/cne.903140408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shkumatava A, Neumann CJ. Shh directs cell-cycle exit by activating p57Kip2 in the zebrafish retina. EMBO Rep. 2005;6:563–569. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strettoi E, Porciatti V, Falsini B, Pignatelli V, Rossi C. Morphological and functional abnormalities in the inner retina of the rd/rd mouse. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5492–5504. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05492.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thor S, Ericson J, Brannstrom T, Edlund T. The homeodomain LIM protein Isl-1 is expressed in subsets of neurons and endocrine cells in the adult rat. Neuron. 1991;7:881–889. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90334-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vardi N. Alpha subunit of Go localizes in the dendritic tips of ON bipolar cells. J Comp Neurol. 1998;395:43–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vardi N, Matesic DF, Manning DR, Liebman PA, Sterling P. Identification of a G-protein in depolarizing rod bipolar cells. Vis Neurosci. 1993;10:473–478. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800004697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HF, Liu FC. Developmental restriction of the LIM homeodomain transcription factor Islet-1 expression to cholinergic neurons in the rat striatum. Neuroscience. 2001;103:999–1016. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00590-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werblin FS, Dowling JE. Organization of the retina of the mudpuppy, Necturus maculosus. II. Intracellular recording. J Neurophysiol. 1969;32:339–355. doi: 10.1152/jn.1969.32.3.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida K, Watanabe D, Ishikane H, Tachibana M, Pastan I, Nakanishi S. A key role of starburst amacrine cells in originating retinal directional selectivity and optokinetic eye movement. Neuron. 2001;30:771–780. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00316-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young RW. Cell differentiation in the retina of the mouse. Anat Rec. 1985;212:199–205. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092120215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Marin O, Hermesz E, Powell A, Flames N, Palkovitz M, Ruben-stein JL. The LIM-homeobox gene Lhx8 is required for the development of many cholinergic neurons in the mouse forebrain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9005–9010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1537759100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J, Lee S, Zhou ZJ. A transient network of intrinsically bursting starburst cells underlies the generation of retinal waves. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:363–371. doi: 10.1038/nn1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]