Abstract

O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) is a sugar attachment to serine or threonine hydroxyl moieties on nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins. In many ways, O-GlcNAcylation is similar to phosphorylation since both post-translational modifications cycle rapidly in response to internal or environmental cues. O-GlcNAcylated proteins are involved in transcription, translation, cytoskeletal assembly, signal transduction, and many other cellular functions. O-GlcNAc signaling is intertwined with cellular metabolism; indeed, the donor sugar for O-GlcNAcylation (UDP-GlcNAc) is synthesized from glucose, glutamine, and UTP via the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway. Emerging research indicates that O-GlcNAc signaling and its crosstalk with phosphorylation are altered in metabolic diseases, such as diabetes and cancer.

O-GlcNAc: A metabolic Signaling Molecule

One of the most pressing medical issues facing industrialized countries is the rapid rise of type 2 diabetes, a metabolic disorder characterized by severely elevated blood glucose and insensitivity to insulin. In the United States alone, 7.8% of the population is diagnosed with diabetes, and up to 57 million Americans have pre-diabetes. The cost for treating type 2 diabetes was $174 billion in 2007, and consumed 32% of Medicare spending (http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/pdf/ndfs_2007.pdf). Furthermore, diabetes is a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease, cardiovascular disease, and cancer, but the underlying mechanisms remain poorly understood1. Both diabetes and cancer show cellular alterations in energy metabolism, stress responsiveness, and signaling. Multiple biochemical processes are involved; however, one potential link in all of these diseases is disrupted O-GlcNAc signaling.

O-GlcNAc is a post-translational protein modification consisting of a single N-acetylglucosamine moiety attached via an O-β-glycosidic linkage to serine and threonine residues2–4. O-GlcNAc modified proteins are generally either cytoplasmic or nuclear proteins, and unlike asparagine-linked or mucin-type O-glycosylation, O-GlcNAc is not further processed into a complex oligosaccharide2, 3. In many ways, O-GlcNAc is similar to protein phosphorylation; for example the sugar can be attached or removed dynamically in response to changes in the cellular environment triggered by stress, hormones, or nutrients [5,6]. Because O-GlcNAc is attached to serine/threonine residues, the sugar is in direct competition with phosphorylation (eg. c-myc7). Furthermore, O-GlcNAcylated or phosphorylated residues can be in close proximity to each other and sterically impair the attachment of the other modification5. O-GlcNAcylation is catalyzed by a highly-conserved and unique enzyme, uridine diphospho-N-acetylglucosamine:polypeptide β-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase (O-GlcNAc transferase, OGT). In cells, the OGT catalytic subunit dynamically forms many specific holoenzyme protein complexes that regulate its specific activity toward its myriad of target protein substrates. By contrast, phosphorylation involves hundreds of individual kinases, each with their own unique activity5. Similarly, whereas there exist several protein phosphatases that remove phosphorylation, there is only a single cytosolic or nuclear β-N-acetylglucosaminidase (O-GlcNAcase, OGA) that is also targeted to substrates by forming many transient holoenzyme complexes to remove the sugar moiety5.

ATP, the donor substrate for kinases, is present at high cellular concentrations (approximately 100 nmol/g)8, 9. Although ATP is mostly used to provide energy for cellular processes, it also directly links energy metabolism to signaling. Uridine diphosphate N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc), the high energy donor substrate for OGT, sits at the nexus of glucose, nitrogen, fatty acid and nucleic acid metabolic pathways (Figure 1), all of which dynamically influence its cellular concentration. Just like ATP, UDP-GlcNAc is often found at relatively high cellular concentrations (approximately 40 nmol/g in tissue)9, and is used not only for O-GlcNAcylation, but also for the biosynthesis of complex extracellular glycans10. In this review, we highlight the underlying mechanisms behind altered O-GlcNAc signaling in diabetes and cancer, and discuss the latest research linking glucose metabolism to modulation of signaling cascades by O-GlcNAc.

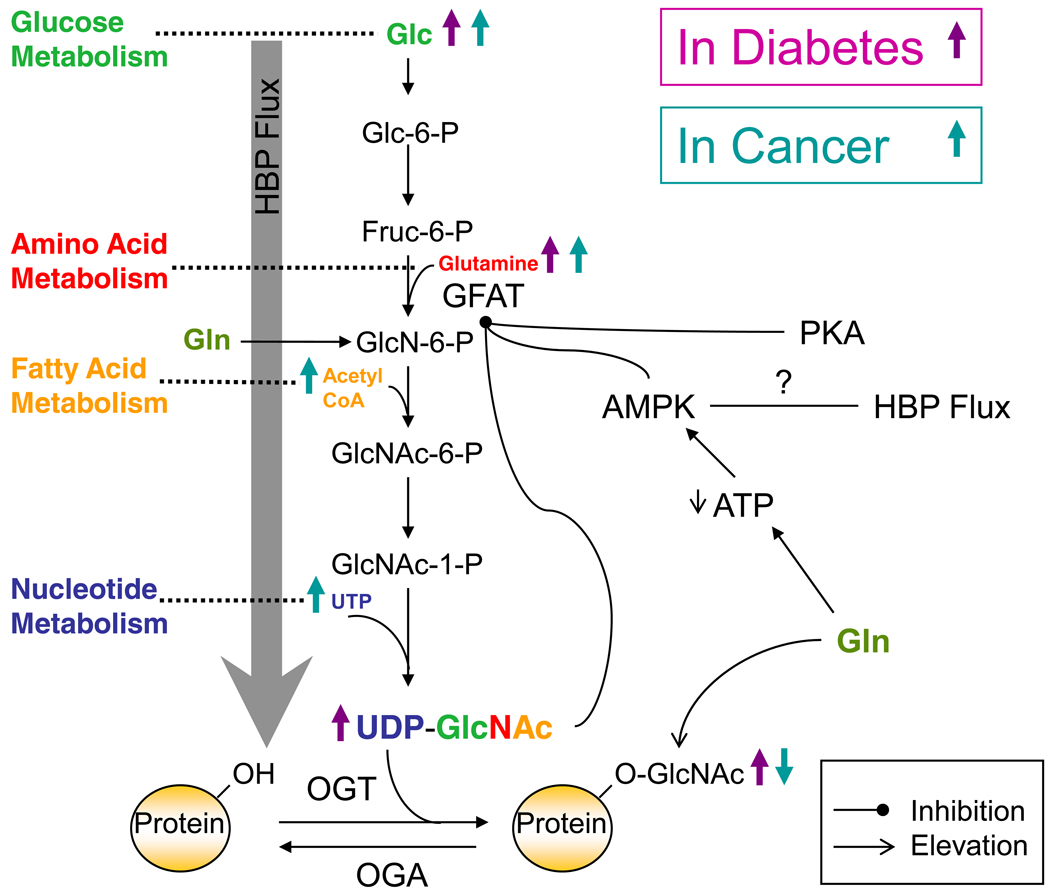

Figure 1. Diabetes and Cancer Influence O-GlcNAc Through the Hexosamine Biosynthetic Pathway (HBP).

The HBP combines various metabolic inputs to ultimately serve in the synthesis of UDP-GlcNAc, the donor substrate for OGT. Approximately 2–3% of cellular glucose (Glc) is funneled into the HBP. Glucose is first phosphorylated by hexokinase to produce glucose-6-phosphate (Glc-6-P) which is then converted into fructose-6-phosphate (Fruc-6-P) by phosphoglucose isomerase. Next during the rate-limiting step of the pathway, glutamine:fructose-6-phosphate (GFAT) converts Fruc-6-P into glucosamine-6-phosphate (GlcN-6-P). Then a series of enzymatic steps leads to the production of UDP-GlcNAc, which can serve as a negative feedback inhibitor of GFAT. OGT is the enzyme responsible for the addition of a single N-acetylglucosamine residue (GlcNAc) to the hydroxyl groups of serine and/or threonine residues of target proteins, while OGA serves to remove the modification. Flux through the HBP and thus the production of UDP-GlcNAc and O-GlcNAcylation are influenced by various disease states including diabetes and cancer (purple arrows and teal arrows respectively) via their effects on metabolism (glucose “green”, amino acid “red”, fatty acid “orange”, and nucleotide “blue”). Insulin resistance resulting in an increase in glucose levels classically marks the diabetic condition. This increase in glucose can be funneled into the HBP causing an increase in HBP flux and consequently increasing O-GlcNAcylation. Due to cancer cells need for energy, a number of metabolites are often in excess and can be funneled in the HBP causing flux as well, namely glucose, glutamine, acetyl-CoA, and UTP.

Glucosamine (Gln) treatment can bypass GFAT and result in an increase in O-GlcNAcylation. The HBP can by inhibited or slowed down by a couple mechanisms in addition to its negative feedback inhibition by UDP-GlcNAc. Gln treatment can also serve to decrease ATP levels thereby activating AMPK, which in turn can inhibit GFAT. Additionally, GFAT has two cyclic AMP dependent protein kinase (PKA) sites at serines 205 and 235. Phosphorylation at serine 205 decreases GFAT activity while phosphorylation at serine 235 has no effect.

Nutrient Flux through the Hexosamine Biosynthetic Pathway (HBP)

The HBP integrates a variety of metabolic inputs in the synthesis of UDP-GlcNAc (Figure 1). First, approximately 2–3% of total cellular glucose is funneled into the HBP5, 10, 11, although the glucose flux is potentially different in various cell types and we know little about the regulation of the flux of glucose into the HBP. The HBP shares its first two steps with glycolysis; first, hexokinase phosphorylates glucose to produce glucose-6-phosphate, which is then converted into fructose-6-phospate by phosphoglucose isomerase. At this point the pathways diverge, fructose-6-phosphate is converted by the HBP rate-limiting enzyme glutamine: fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase (GFAT1) into glucosamine-6-phosphate. GFAT1 catalyzes the irreversible transfer of the amino group from glutamine and the isomerization of fructose-6-phosphate into glucosamine-6-phosphate and glutamate12. Not only is GFAT1 dependent on glucose flux into the cell, it also must integrate signals from amino acid metabolism.

GFAT1 is the rate-limiting step of the HBP due to feedback inhibition by both the enzymatic product glucosamine-6-phosphate and the final product UDP-GlcNAc12. Intuitively, increased cellular glucose and flux through the HBP would only increase UDP-GlcNAc levels to a specific concentration and no higher. For example, adipocytes exposed to increasing amounts of glucose in the presence of insulin show a 30% increase in UDP-GlcNAc concentration compared to a 365% increase in glucose uptake13. Is this slight increase in UDP-GlcNAc concentration enough to allow O-GlcNAc to act as a nutrient sensor? Potentially, the answer is yes because of the unique ability of O-GlcNAc transferase to respond to UDP-GlcNAc concentrations. OGT purifies as a multimer with a low apparent Km for UDP-GlcNAc (545 nM) allowing the enzyme to be active in times of low UDP-GlcNAc concentrations, and allowing the enzyme to out-compete nucleotide transporters in the Golgi and endoplasmic reticulum (ER)14. However, in vitro, the rate of OGT’s transfer of O-GlcNAc to peptides is directly responsive to an extraordinary range of UDP-GlcNAc concentrations, from low nanomolar to above fifty millimolar. Furthermore, increasing UDP-GlcNAc concentrations change OGT’s apparent Km for peptide substrates, with most peptides becoming better substrates as UDP-GlcNAc increases15. Even a slight increase in UDP-GlcNAc concentration, due to nutrient excess, causes different proteins to become more extensively O-GlcNAcylated.

Regulation of GFAT1 also occurs at the translational and posttranslational level. Diabetic patients exposed to chronic nutrient excess demonstrate increased GFAT1 activity correlated with increased GFAT1 mRNA levels in lymphocytes16 and skeletal muscle17. However, it is not clear if the increase in GFAT1 activity is an adaptive response of the cells caused directly by the nutrient overload, or alternatively if the hyperglycemic environment increases GFAT1 mRNA levels through altered regulation of a signaling pathway. In skeletal and heart muscle, a GFAT1 splice variant, termed GFAT1-L, is expressed18. GFAT1-L retains full enzymatic activity and has a 54 base pair insertion compared to GFAT1; little is known about its regulation. Additionally, a highly homologous GFAT2 isoform is expressed in heart and nervous tissue19.

Both GFAT1 and GFAT2 are targets for protein phosphorylation. GFAT1 has two cyclic AMP dependent protein kinase (PKA) sites at serines 205 and 235. Whereas phosphorylation of S205 decreases cellular enzymatic activity, S235 phosphorylation does not affect activity20, 21. GFAT2 has a PKA site at serine 202 homologous to S205 of GFAT1, but PKA phosphorylation of this site increases its cellular activity22. Thus, GFAT2 appears to be regulated differently than GFAT1, possibly mediated via interactions with different proteins. Owing to the different tissue expression of these isoforms, the HBP in these tissues could be regulated differentially by hormonal signals.

GFAT1 activity is directly linked to changes in cellular energy. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is regulated by the cellular ATP:AMP ratio23; it is allosterically activated by AMP, which is normally present at low concentrations, although stress, hormones, or energy imbalance can increase AMP concentrations dramatically23. Upon AMPK activation, GFAT1 and GFAT2 are phosphorylated at S24324, 25. Much like S205 phosphorylation, GFAT1 phosphorylated at S243 in vivo is less active25. Furthermore, activation of AMPK causes an increase in OGT mRNA levels and protein expression26, and AMPK appears to either be O-GlcNAc modified or associated with an O-GlcNAcylated protein27. When GFAT1 is bypassed by glucosamine treatment, which elevates O-GlcNAc levels28, AMPK activity is higher; by contrast, hexosaminidase treatment of AMPK lowers its activity27. Therefore, O-GlcNAcylation of AMPK or an interacting partner potentially increases AMPK activity leading to GFAT1 inhibition and paradoxically stimulating OGT expression. The regulation of the HBP is complex and is sensitive to both nutrient alteration and phosphorylation, ultimately impinging upon O-GlcNAc signaling (Figure 1).

O-GlcNAc Signaling in a Diabetic Background

In normal liver cells exposed to insulin, a complex signal transduction cascade is initiated resulting in altered gene expression and the translocation of the insulin responsive glucose transporter GLUT4 to the plasma membrane29. Insulin binds to the insulin receptor causing the receptor to autophosphorylate, which recruits the insulin receptor substrate (IRS1 or IRS2)29. IRS is phosphorylated at multiple tyrosine residues, activating the docking of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) regulatory subunit, p85, to IRS29. Once docked, PI3K catalyzes the production of phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-triphosphate (PIP3) at the plasma membrane29. PIP3 recruits PIP3-dependent kinase (PDK1) and AKT (protein kinase B)29. PDK1 subsequently activates AKT via phosphorylation at threonine 308. AKT then phosphorylates numerous substrates, including Rab-GTPase activating proteins, which leads to GLUT4 translocation to the membrane29; Forkhead (FOXO) family transcription factors, which become excluded from the nucleus and can no longer activate gluconeogenic genes (Box 1); and glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β), which in turn signals for increased glycogen production (Figure 2, Panel A).

TEXT BOX 1: The Paradox of Gluconeogenic Gene Transcription in Diabetes

One of the many conundrums associated with diabetes is an increase in gluconeogenic gene transcription and gluconeogenesis in insulin-resistant liver tissue30 most likely through dysregulation of the signaling cascades that control this process. Upon hepatic over-expression of OGT, gluconeogenic genes are up-regulated38, likely from altered phosphorylation and O-GlcNAcylation of the FOXO transcription factors30. Under normal insulin signaling conditions, activated AKT phosphorylates FOXO1, causing exclusion from the nucleus and decreased transcription of gluconeogenic genes; however, impaired insulin signaling and AKT activation reduces these critical FOXO1 phosphorylations. Furthermore, FOXO1 is increasingly modified by O-GlcNAc under hyperglycemic conditions30. The FOXO transcriptional co-activator PGC1α, which interacts with and targets OGT to FOXO1, promotes increased FOXO1 O-GlcNAcylation77. Activation of FOXO target genes is also amplified under hyperglycemic conditions by cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element-binding protein (CREB)-regulated transcription coactivator 2 (CRTC2). CRTC2 becomes O-GlcNAcylated and binds OGT under hyperglycemic conditions in liver tissue45. O-GlcNAcylated CRTC2 can no longer bind 14-3-3 proteins in the cytoplasm and translocates to the nucleus, where it promotes gluconeogenic gene transcription45. CRTC2 associates with CREB and promotes CREB target gene expression (e.g., PGC1α), which in turn targets OGT to FOXO1 and further up-regulates gluconeogenic gene transcription77.

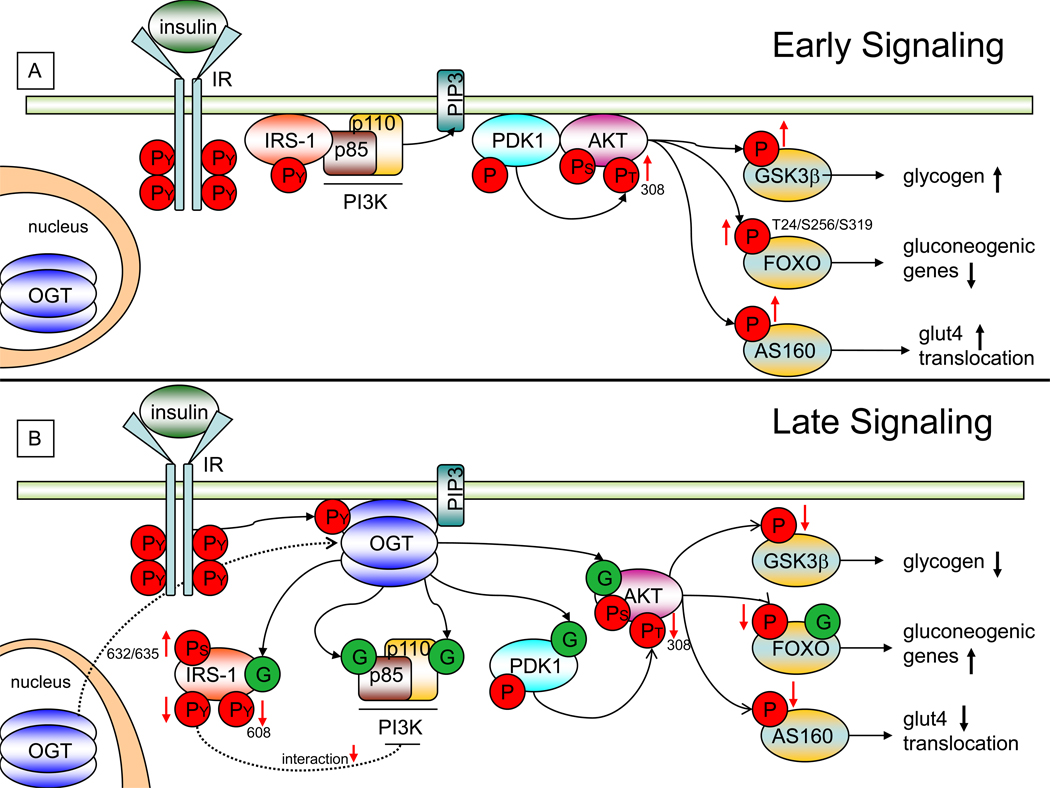

Figure 2. OGT and O-GlcNAc Regulate Insulin Signaling.

During prolonged insulin signaling O-GlcNAcylation of key molecules have an affect on the attenuation of the insulin signaling cascade. As with any signaling cascade, there must be a mechanism in place to down-regulate the cascade after a prolonged period of activation. O-GlcNAcylation of key molecules can achieve this via the translocation of OGT in response to insulin.

A) During normal cellular conditions and early insulin mediated signaling, OGT (blue) is localized within the nucleus. Upon insulin stimulation, insulin (light green) binds the insulin receptor (IR, light blue) causing its autophosphorylation at tyrosine residues (PY, red circles). Phosphorylation of the IR recruits IRS-1 (light red) to the membrane. IRS-1 is phosphorylated at multiple tyrosine residues, resulting in its binding to the p85 regulatory subunit (brown) of PI3K. PI3K then catalyzes the production of PIP3 (light blue) at the plasma membrane. PIP3 recruits PDK-1which increases the phosphorylation of AKT at threonine-308 (PT, red circle) causing its activation. Activated AKT then phosphorylates various substrates. Phosphorylation of GSK3β results in an increase in glycogen production. Phosphorylation of FOXO results in a decrease in transcription of gluconeogenic genes. Phosphorylation of AS160 results in increased GLUT4 translocation.

B) As a response to prolonged insulin signaling, a subset of OGT translocates from the nucleus to the plasma membrane and binds PIP3 through a PIP3 binding domain at its C-terminus. At the membrane, OGT is tyrosine phosphorylated by the IR leading to an increase in OGT’s activity. Active OGT can O-GlcNAcylate key molecules namely p85/p110, PDK1, AKT, and FOXO to alter insulin signaling. O-GlcNAcylation (green circles) of IRS-1 can decrease its interaction with p85, decrease its activating phosphorylation at tyrosine-608 (thereby reducing its activity), while increasing its phosphorylation at serines-632 and 635. O-GlcNAcylation of AKT, results in a decrease in its activating phosphorylation of threonine-308. This causes a decrease in phosphorylation of GSK3β, FOXO, and AS160. Decreasing phosphorylation of GSK3β results in decreased glycogen production. Decreasing phosphorylation of FOXO (along with increasing its O-GlcNAcylation) results in an increase in gluconeogenic genes. Decreasing phosphorylation of AS160 results in a decrease in GLUT4 translocation. Taken together O-GlcNAcylation of specific proteins within the insulin signaling pathway can result in a “dampening” effect of the insulin mediated signal.

Not surprisingly, increased flux though the HBP causes insulin resistance. Following a switch from normal to extremely high glucose concentrations, cultured cells show a slight increase in O-GlcNAcylation with some signs of altered insulin signaling30. Glucosamine treatment causes insulin resistance10. Of course, a major outcome of glucosamine treatment is elevated O-GlcNAc levels31. However, exogenous glucosamine impinges on many pathways. Therefore linking glucosamine-induced insulin resistance directly to O-GlcNAc signaling is difficult. One way to avoid the myriad effects of glucosamine or even high glucose is to instead treat cells with pharmacological inhibitors of O-GlcNAcase to increase cellular O-GlcNAcylation. Treating adipocytes in culture with PUGNAc, an O-GlcNAcase inhibitor, increases O-GlcNAc levels and impairs insulin signaling31. In the presence of PUGNAc, the activating AKT phosphorylation on Thr308 is reduced, downstream signaling through GSK3β is impaired, and glucose uptake is less efficient31, 32.

Conversely, when adipocytes are treated with a more selective O-GlcNAcase inhibitor, they show no signs of insulin resistance33. PUGNAc inhibits other hexosaminidases, through off-target effects, potentially altering oligosaccharide structures at the plasma membrane33. These oligosaccharide structures are critical in transducing extracellular signals. A major caveat in studies using O-GlcNAcase inhibitors to elevate O-GlcNAc is that cells rapidly respond to elevated O-GlcNAc by increasing the expression of O-GlcNAcase. Furthermore, reduction of O-GlcNAc rapidly results in the upregulation of OGT expression34. Cells attempt to maintain normal O-GlcNAc function, but not necessarily the absolute stoichiometry. One way of circumventing the problem of the lack of specificity of pharmacological agents is with genetic manipulation. Transgenic mice over-expressing human OGT in their adipocytes and skeletal/cardiac muscles35 appear to have normal weight, fat pad and muscle histology, as well as fasting glucose levels, but the animals suffer from hyperinsulinemia, lower glucose disposal rates, and a reduction in serum leptin levels35. However, over-expression of O-GlcNAcase or knockdown of OGT did not impair insulin signaling in adipocytes36. Although this study is in contradiction to several other genetic studies, no measurement of OGT protein levels was performed when OGA was over-expressed; likewise OGA levels were not examined when OGT was knocked down. Again, alterations in OGT or OGA protein levels cause a reciprocal change in the other’s expression34, which might partially explain this discrepancy. Current data suggest that altered O-GlcNAcylation per se might not be sufficient to induce profound insulin resistance, and that other unknown factors are involved.

O-GlcNAc Transferase Regulates Insulin Signaling

Studies from several laboratories suggest that O-GlcNAcylation plays a direct role in insulin signaling (for reviews1,3,10). Under normal cellular conditions, OGT is localized to the nucleus and the perinuclear region with only moderate staining observed in the cytoplasm37. However, upon insulin stimulation a subset of OGT translocates to the plasma membrane38, 39, mediated by a non-canonical PIP3 binding domain on the OGT carboxy-terminus 38. At the membrane, OGT associates with the insulin receptor39 and undergoes tyrosine phosphorylation, thus leading to an increase in activity39. OGT then O-GlcNAcylates several components of the signaling pathway38, including IRS138, 40. IRS1 is O-GlcNAcylated in a time-dependent manner with maximum O-GlcNAcylation occurring approximately 30 minutes after insulin stimulation. Thereafter, O-GlcNAcylation of IRS1 rapidly declines38.

Mass spectrometry based site-mapping approaches have determined at least 3 O-GlcNAc sites on the IRS1 C-terminus, one of which is close to a putative Src homology domain 2 (SH2) binding domain for the PI3K p85 subunit 41, 42. Increased O-GlcNAc on IRS1 potentially causes a reduction in its interaction with p85 and a dampening of the activating tyrosine phosphorylation at Y608 of IRS143. O-GlcNAcylation of IRS1 reduces Y608 phosphorylation, and concomitantly promotes IRS1 Ser632 and Ser635 phosphorylation, resulting in attenuated insulin signaling38, 43. OGT trafficking to the plasma membrane requires its PIP3 binding domain and occurs upon PI3K activation38. Mice injected with adenovirus expressing OGT bearing a mutated PIP3-binding domain do not show hepatic insulin resistance. Clearly, IRS1 O-GlcNAcylation plays a role in the normal attenuation of insulin signaling, and might also play a direct role in insulin resistance during nutrient excess, which promotes hyper-O-GlcNAcylation (Figure 2, Panel B).

Other components of the insulin signaling pathway are modified by O-GlcNAc. OGT in vitro O-GlcNAcylates IRS2, PI3K, and PDK43, and AKT is O-GlcNAcylated in vivo after insulin stimulation (Figure 2 Panel B)38, 44. O-GlcNAcylation of AKT lowers phosphorylation on Thr308 and alters downstream signaling31, 38. For example, GLUT4-mediated glucose uptake would decrease; this is part of the normal insulin attenuation process in healthy individuals, but premature dampening of the insulin signal or excessive O-GlcNAcylation could keep blood glucose high and put more stress on the pancreas to produce even more insulin31, 38. How then would chronic hyperglycemia elevate O-GlcNAc levels if GLUT4-mediated glucose uptake is impaired? Passive glucose uptake by the ubiquitous GLUT1 transporter might provide an explanation; however, the mechanism remains unclear.

If too much O-GlcNAc and OGT disrupts insulin signaling, then would the converse of reduced O-GlcNAcylation and/or more O-GlcNAcase promote proper insulin signaling? At least under diabetic conditions, reduced O-GlcNAcylation is beneficial. O-GlcNAcase over-expression relieves hepatic insulin resistance45, and rescues the function of diabetic cardiomyocytes46. Mexican Americans with a single nucleotide polymorphism within the O-GlcNAcase gene (MGEA5) are at higher risk for diabetes47.

Cancer’s Influence on the Hexosamine Biosynthetic Pathway

A physiological hallmark of tumors is the use of aerobic glycolysis (also known as the Warburg effect) instead of oxidative phosphorylation to produce ATP48. Aerobic glycolysis is a normal function of rapidly proliferating cells which provides both bioenergetic and biosynthetic needs49, 50. Herein, we will discuss aerobic glycolysis and how it influences the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway, and how disruption of the HBP alters O-GlcNAcylation. Aerobic glycolysis is characterized by the conversion of glucose into pyruvate, which is further metabolized into lactate, generating 2 net molecules of ATP, lactate, which is excreted, and NAD+, which feeds back into glycolysis51. Although aerobic glycolysis is an inefficient process, in a nutrient rich environment, efficient energy production is less important than biosynthesis48. Cancerous cells are programmed to rapidly proliferate; therefore, the cell must consume carbon and nitrogen rich nutrients to biosynthesize metabolites needed for cell proliferation. Aerobic glycolysis generates pyruvate, which in turn is used for energy or is fed into the citric acid cycle where the metabolites are used in cataplerotic reactions (those that replenish intermediates of the citric acid cycle)48.

Diabetes provides at least some additional mortality risk for all cancers due to the hyperinsulinemic and hyperglycemic state feeding a tumor by promoting insulin and insulin-like growth factor signaling and by providing excessive amounts of glucose1. This excess glucose can be shunted into the HBP as well as into excess metabolites, such as acetyl-CoA and ribonucleotides (Figure 1). The other major metabolite funneling into the HBP is glutamine. Cancer cells are addicted to glutamine; the rate of glutamine consumption in tumors is 10 fold higher then normal cells52, 53. Glutamine is the main energy source in many cancer cells: first by its conversion to glutamate by glutaminase then into α-ketoglutarate in the mitochondria53; the excess ammonia generated by the reaction is excreted54. RNAi-mediated knockdown of glutaminase decreases GFAT1 activity, and the cells experience a slight reduction in O-GlcNAc levels and in OGT O-GlcNAcylation55. The loss of glutaminase function dramatically reduces the flux of glutamine to α-ketoglutarate, severely depleting energy and reducing flow into the HBP.

It is unclear if UDP-GlcNAc concentrations are higher in cancer cells. However, N-linked glycosylation, which uses UDP-GlcNAc as a donor substrate, generates larger, more highly branched oligosaccharides in tumor cells, suggesting an increased need for the metabolite56. The amount of O-GlcNAc modified protein is lower and O-GlcNAcase activity is higher in solid tumors from breast cancer patients, especially in more aggressive tumors; however, the data set is relatively small, so statistically it is unclear if elevated O-GlcNAcase activity is a marker for metastatic potential57. By contrast, tumor cell lines that mimic metastatic tumors show an increase in OGT protein expression and O-GlcNAc suggesting that an increase in O-GlcNAcylation might be beneficial to cancer cells58.

O-GlcNAcylation of Oncogenes and Tumor Suppressors

c-Myc is a transcription factor whose expression increases in proliferative cells and regulates genes involved in glycolysis, purine/pryimidine, and lipid metabolism59, 60, as well as genes involved in glutamine metabolism, mitochondria biosynthesis, cell cycle control, and HBP genes 60, 61. C-Myc is O-GlcNAcylated62 at threonine 58, which is also a GSK3β phosphorylation site7. GSK3β requires a priming phosphorylation site before it can actively phosphorylate most substrates; in the case of c-Myc the priming site is at serine 62 (a proline-directed phosphorylation site often targeted by mitogen-activated protein kinase; MAPK)63. Inhibition of GSK3β by lithium chloride or a substitution of the priming Ser62 to alanine elevates O-GlcNAcylation on Thr58. By contrast, serum stimulation increases phosphorylation at Thr5864, an event which promotes c-Myc degradation63. Notably, in Burkett lymphoma the most common mutations in MYC affect Thr58 63, suggesting that phosphorylation of this site reduces protein stability and leads to c-Myc degradation and a reduction in c-Myc target gene expression63. By contrast, an O-GlcNAc residue at Thr58 would block phosphorylation and potentially stabilize the protein. This mechanism is seen in other transcription factors: the C/EBPβ transcription factor is also O-GlcNAcyalted adjacent to a MAPK priming phosphorylation site. O-GlcNAcylation severely reduces MAPK ability to phosphorylate C/EBPβ and in turn GSK3β’s ability to phosphorylate C/EBPβ65. By blocking the phosphorylation on C/EBPβ, transactivation and DNA binding are also reduced causing delays in adipocyte differentiation65. O-GlcNAc acts antagonistically to phosphorylation, changing the activity and function of the protein. Potentially, c-Myc O-GlcNAcylation might alter the activity of c-Myc in two ways, either by blocking the Thr58 phosphorylation or by interfering with the priming phosphorylation at Ser62. Clearly, a sophisticated interplay of phosphorylation and O-GlcNAcylation occurs at serine/threonine residues on proteins, but teasing out this relationship is challenging. For example, simply making alanine substitutions at these sites in order to determine phosphate or O-GlcNAc function is not sufficient, because this mutation will directly prevent both modifications. The availability of phosphate mimetics helps to elucidate phosphate functions; unfortunately, there are no amino acid substitutions that can mimic the actions of O-GlcNAc.

This type of interplay occurs with another transcription factor-tumor suppressor protein, p5366. The stability of p53 is tightly regulated by phosphorylation. Normally, p53 is kept at low levels in the cells by phosphorylation at Thr155 targeting the protein for proteasomal degradation. However, when Ser149 of p53 is O-GlcNAcylated, the protein is stabilized, while Thr155 phosphorylation is decreased66.

Several studies indicate that O-GlcNAcylation regulates the cell cycle. Because Ogt is an essential gene, mouse knockouts are lethal67; however, conditional Ogt knockout mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cells show cell cycle defects leading to an increase cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27Kip1 and subsequent senescence68. Additionally, OGT siRNA-mediated knockdown in breast cancer cells recapitulates the data seen in the knockout MEFs58. In HeLa (cervical carcinoma) cells synchronized at the G1/S transition then released into serum, over-expression of either OGT or OGA causes mitotic exit defects34. Interestingly, decreases in O-GlcNAc either from OGA over-expression or inhibition of GFAT1 accelerated S-phase transitions in these cells whereas OGA inhibitor treatment slowed S-phase completion34. These results suggest that O-GlcNAc is required for cell cycle progression, whereas high levels or the complete lack of O-GlcNAcylation activates stress response pathways that arrest the cell cycle checkpoint (Box 3). By example, one clinical manifestation of diabetes is nephropathy. Kidney glomerular mesangial cells respond to chronic hyperglycemia by entering the cell cycle69. The cells proliferate quickly through a few cell divisions and then become arrested at G1/S, an event characterized by hypertrophy and increased expression p27Kip1 69. Eventually the cells lose function and undergo cell death. This same phenotype can be replicated with the use of glucosamine, suggesting that HSP flux leading to O-GlcNAcylation is involved in regulating transitions throughout the cell cycle69.

Text Box 3: Stress Activation of O-GlcNAcylation

Checkpoint arrest occurs under cell stress, and one mechanism cells use to manage cellular stress is to rapidly elevate O-GlcNAc80. Increased O-GlcNAcylation of many pro-survival proteins is observed in response to numerous forms of stress (heat shock, oxidative, osmotic, ER, glucose, etc.) 26, 80–82. This response is, in part, mediated by an increase in OGT activity. Ogt knockout MEFs are severely compromised by stress80, pointing to a critical role for OGT as an effector of stress responses. Increased O-GlcNAc levels promote heat shock factor 1 (HSF1) nuclear translocation and transcription of heat shock protein 70 (HSP70)80. HSP70 binds to and stabilizes proteins during diverse stress responses, and it appears to act as an O-GlcNAc lectin. Therefore, elevated O-GlcNAc might be a signal for HSP70 protein binding83.

Altered O-GlcNAcylation in response to stress probably has a role in the progression of diabetes and cancer. For instance, increased production, by the mitochondria, of reactive oxygen species (ROS) is a hallmark of both hyperglycemia and the tumor microenvironment. Cells adapt to this cellular stress by rapidly raising O-GlcNAc levels and increasing the activity of the HBP84. However, long term increased O-GlcNAcylation in response to chronic stress potentially could affect signaling pathways, such as by down regulating insulin signaling (Figure 2 Panel B). Impaired insulin signaling occurs in mouse models of chronic renal failure. These mice produce large amounts of ROS, elevating IRS1 O-GlcNAcylation in adipocytes and reducing insulin sensitivity85. Clearly, stress-induced increases in O-GlcNAc are pro-survival in the short-term; however, chronic stress and prolonged elevated O-GlcNAcylation impairs signaling networks and alters cellular physiology.

Promoting Aneuploidy Through O-GlcNAc

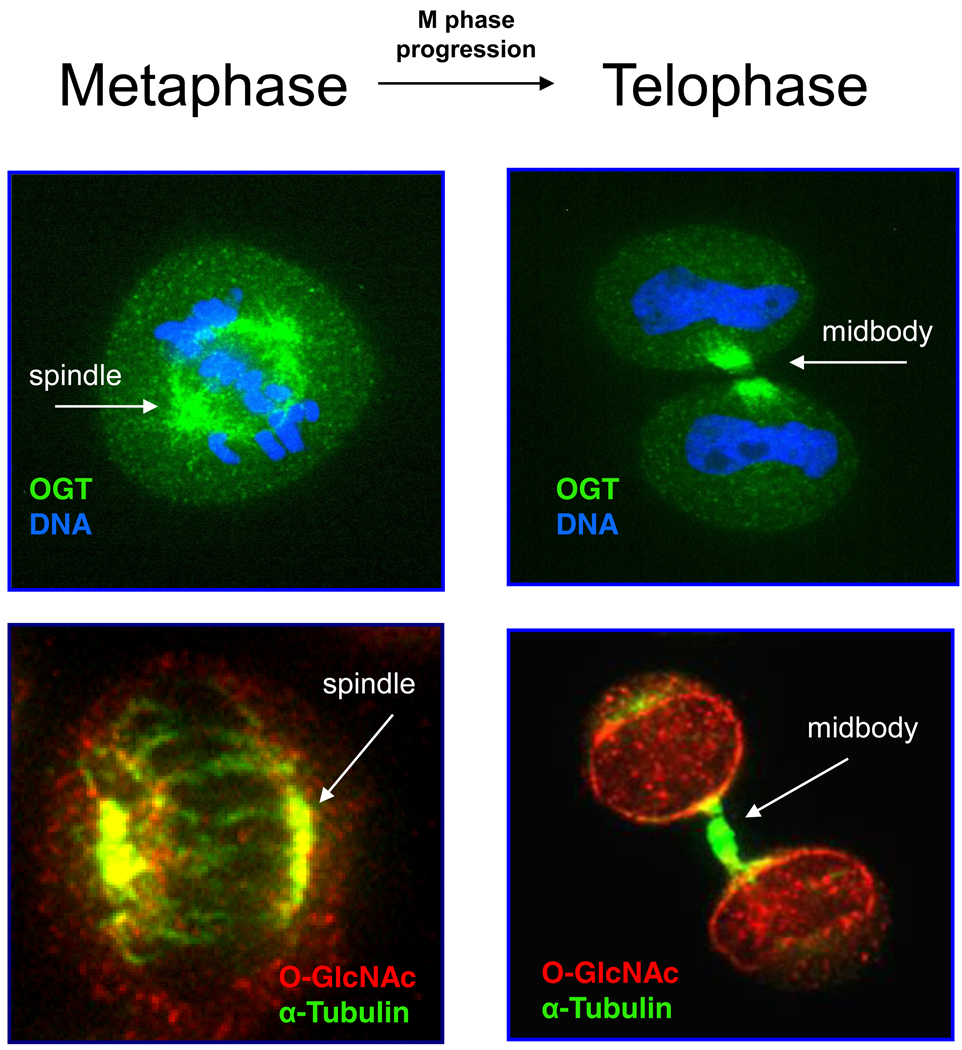

A common phenotype in cancer cells is aneuploidy (abnormal number of chromosomes), which promotes tumorigenesis70. Whereas partial loss of mitotic checkpoint control causes low levels of aneuploidy, complete loss of checkpoint control causes massive aneuploidy and cell death70. Over-expression of OGT by only two-fold promotes aneuplody through disruptions in mitotic progression34. Normally, during M phase, a subset of OGT localizes to the mitotic spindle, which then moves through the cleavage furrow into the midbody (Figure 3)34, 71. OGT probably performs multiple functions at the spindle: i) OGT O-GlcNAcylates numerous proteins associated with spindles and midbodies regulating their function (Figure 3); and ii) OGT, probably via its tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) domains, provides a scaffold to facilitate protein–protein interactions34, 72.

Figure 3. OGT O-GlcNAcylates Many Mitotic Spindle and Midbody Proteins.

Previous studies have demonstrated that O-GlcNAc plays roles in cell cycle regulation. Cancer cells have misregulated progression through the cell cycle constituting abnormal cell growth. Given the established link between O-GlcNAc and cell cycle progression, researchers have used immunoflurosecene to visualize OGT and protein O-GlcNAcylation during M-phase progression.

During metaphase, OGT (green) localizes to the spindle pole of the mitotic spindle (DNA in blue). O-GlcNAc proteins can be found ringing the spindle (red) and concentrated at the poles and with the centrioles (α-tubulin in green and co-staining is yellow). As M phase progresses, OGT moves through the spindle midzone and concentrates at the midbody, whereas O-GlcNAc modified proteins increase at the midbody and at the nasent nuclear membrane. OGT probably performs multiple functions at the midbody, including O-GlcNAcylation of various proteins thereby regulating their functions and also possibly acting as a scaffold to facilitate a number of protein-protein interactions via OGT’s TPRs.

Using a novel mass spectrometric approach to identify O-GlcNAc modified proteins73, over 150 O-GlcNAc sites were found on numerous spindle-midbody proteins from a biochemical preparation of spindle-midbodies. This method, based on affinity enrichment of O-GlcNAc with a photocleavable tag and ETD (Electron Transfer Disassociation) mass spectrometry, mitigates many of the problems found with collision induced dissociation (CID)-based mass spectrometry site mapping. O-GlcNAc sites are difficult to map by CID due to ion suppression by unmodified peptides, preferential loss of O-GlcNAc upon ionization, and low mass to charge ratio73. Upon OGT over-expression, most all O-GlcNAcylation sites identified were increased.

Cyclin-dependent protein kinase 1 (CDK1) is the master regulatory kinase for M phase progression. At M phase, CDK1 binds cyclin B and is dephosphorylated, and therefore activated, at Thr14 and Tyr15 by the duel-specificity phosphatase Cdc25C74. CDK1 promotes M phase progression by phosphorylating numerous target substrates74. OGT over-expression significantly elevates phosphorylation at Thr14 and Tyr15 and greatly reduces CDK1 activity as judged by downstream phosphorylation events72. Moreover, other mitotic kinases interact with OGT. The early M phase kinase polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) and the late M phase kinase Aurora kinase B interact with OGT; potentially, OGT targets these complexes to specific M phase substrates72, 75. PLK1 phosphorylates and inactivates MYT1, the kinase responsible for the inhibitory CDK1 phosphorylations. OGT over-expression reduces MYT1 phosphorylation, suggesting that OGT regulates PLK1 activity 72. These and other studies lead us to conclude that O-GlcNAc is a key regulator of multiple pathways involved in the proper function of M phase progression and that disruption of this pathway might lead to aberrant phenotypes associated with cancer.

Concluding remarks and future perspectives

Obviously, diseases such as diabetes and cancer are increasingly becoming major health risks to industrialized countries. Both diseases present major alterations in metabolism, which will impinge upon and alter O-GlcNAcylation. These alterations to O-GlcNAcylation disrupt cellular signaling cascades and potentially promote the disease state. Understanding the molecular mechanisms in common between these two diseases will provide opportunities for improved treatment. Because aberrant O-GlcNAc signaling is an underlying phenotype shared between these two diseases, a better understanding of O-GlcNAc signaling is critically important. Many questions still remain such as how OGT and OGA target their substrates. Recent work suggests that many proteins can target OGT to specific substrates under different signaling conditions26, 76. How OGT and OGA are targeted to their substrates and what proteins are involved in targeting during diabetes and cancer will provide insights into the molecular mechanism of disease progression and potentially new therapeutic targets.

TEXT BOX 2: Regulation of Phosphorylation by O-GlcNAc

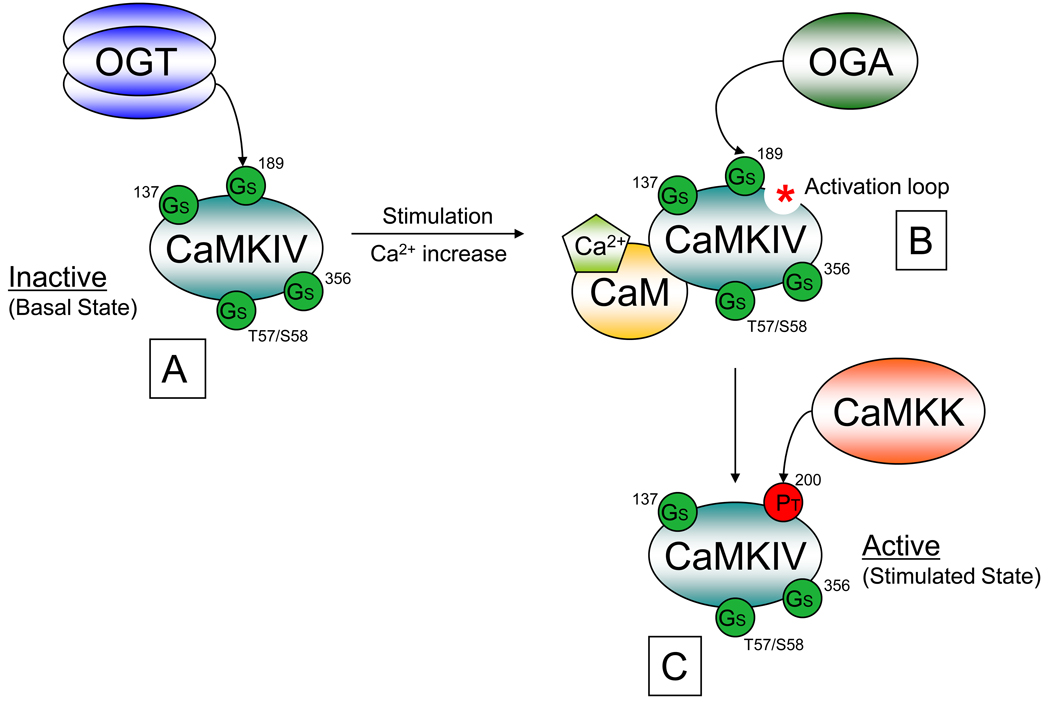

As we have seen with insulin signaling, phosphorylation cascades can be regulated by O-GlcNAc. Pharmacological inhibition of O-GlcNAcase reduces phosphorylation on many proteins, as determined by proteomic based techniques78. However, increased O-GlcNAcylation does not simply dampen phosphorylation because for many proteins, their phosphorylation increases upon globally increasing O-GlcNAcylation, suggesting that O-GlcNAc is a regulator of both increased and decreased site-specific phosphorylation events 78. Several kinases are targeted by O-GlcNAcylation38, 43. For example, Calcium/Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV (CaMKIV) contains multiple O-GlcNAcylation sites79. The major site of O-GlcNAcylation on CaMKIV is Ser189, which is very close to Thr200 a major activating phosphorylation site79. During the basal state, CaMKIV is O-GlcNAcylated with high stoichiometry at Ser189, but upon ionomycin stimulation, Ser189 O-GlcNAc is dramatically reduced whereas Thr200 phosphorylation is significantly elevated (Figure I)79. The removal of O-GlcNAc is mediated by the recruitment of OGA to CaMKIV after activation79. Substitution of serine 189 to an alanine promotes Thr200 phosphorylation resulting in significantly higher activity then wildtype79. This study directly shows that O-GlcNAcylation of kinases can alter enzymatic activity causing dramatic effects on downstream signaling events, which could lead to aberrant phenotypes.

Box 2, Figure I. O-GlcNAc and Phosphorylation Regulate Calcium Calmodulin Kinase IV (CAMKIV) activity.

Globally elevating O-GlcNAcylation levels can both decrease and increase site-specific phosphorylation sites of many proteins. These finding suggest that O-GlcNAc can serve as a regulator of site-specific phosphorylation to modulate a protein’s function.

An example of phosphorylation site-specific regulation by O-GlcNAc is observed during calcium dependent CaMKIV activation. A) Under basal conditions CaMKIV (teal) is O-GlcNAcylated by OGT (blue) at multiple sites including Ser137, Ser189, Ser356, and either Thr57 or Ser58 and has little activity. B) Stimulation resulting in an increase in intercellular calcium (Ca2+, light green pentagon), results in CaM (gold, Calmodulin) binding to CaMKIV exposing its activation loop (red asterisk). Stimulation also results in CaMKIV binding to OGA to subsequently remove the O-GlcNAcylation at Ser189. C) The removal of the O-GlcNAcylation at Ser189 results in a contaminant increase in its site-specific phosphorylation at Thr200 by CaMKK (light red, Calcuim/Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase) causing CaMKIV to become activated. O-GlcNAcylation sites are indicated by green circles. Phosphorylation sites are indicated by red circles. Amino acid positions are indicated by numbers.

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the Hart laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript. Research is supported by the National Institutes of Health [R01 DK61671 and R01 CA42486 to G.W.H].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference Cited

- 1.Barone BB, et al. Long-term all-cause mortality in cancer patients with preexisting diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300:2754–2764. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hart GW, et al. Cycling of O-linked beta-N-acetylglucosamine on nucleocytoplasmic proteins. Nature. 2007;446:1017–1022. doi: 10.1038/nature05815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Torres CR, Hart GW. Topography and polypeptide distribution of terminal N-acetylglucosamine residues on the surfaces of intact lymphocytes. Evidence for O-linked GlcNAc. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:3308–3317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Love DC, Hanover JA. The hexosamine signaling pathway: deciphering the "O-GlcNAc code". Sci STKE. 2005;2005:re13. doi: 10.1126/stke.3122005re13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zeidan Q, Hart GW. The intersections between O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation: implications for multiple signaling pathways. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:13–22. doi: 10.1242/jcs.053678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanover JA, et al. The hexosamine signaling pathway: O-GlcNAc cycling in feast or famine. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chou TY, et al. c-Myc is glycosylated at threonine 58, a known phosphorylation site and a mutational hot spot in lymphomas. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:18961–18965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.32.18961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beis I, Newsholme EA. The contents of adenine nucleotides, phosphagens and some glycolytic intermediates in resting muscles from vertebrates and invertebrates. Biochem J. 1975;152:23–32. doi: 10.1042/bj1520023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marshall S, et al. Dynamic actions of glucose and glucosamine on hexosamine biosynthesis in isolated adipocytes: differential effects on glucosamine 6-phosphate, UDP-N-acetylglucosamine, and ATP levels. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:35313–35319. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404133200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marshall S, et al. Discovery of a metabolic pathway mediating glucose-induced desensitization of the glucose transport system. Role of hexosamine biosynthesis in the induction of insulin resistance. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:4706–4712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Copeland RJ, et al. Cross-talk between GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation: roles in insulin resistance and glucose toxicity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;295:E17–E28. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90281.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Broschat KO, et al. Kinetic characterization of human glutamine-fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase I: potent feedback inhibition by glucosamine 6-phosphate. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:14764–14770. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201056200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bosch RR, et al. Hexosamines are unlikely to function as a nutrient-sensor in 3T3-L1 adipocytes: a comparison of UDP-hexosamine levels after increased glucose flux and glucosamine treatment. Endocrine. 2004;23:17–24. doi: 10.1385/endo:23:1:17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haltiwanger RS, et al. Glycosylation of nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins. Purification and characterization of a uridine diphospho-N-acetylglucosamine: polypeptide beta-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:9005–9013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kreppel LK, Hart GW. Regulation of a cytosolic and nuclear O-GlcNAc transferase. Role of the tetratricopeptide repeats. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:32015–32022. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.45.32015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Srinivasan V, et al. Glutamine fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase (GFAT) gene expression and activity in patients with type 2 diabetes: inter-relationships with hyperglycaemia and oxidative stress. Clin Biochem. 2007;40:952–957. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yki-Jarvinen H, et al. Increased glutamine:fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase activity in skeletal muscle of patients with NIDDM. Diabetes. 1996;45:302–307. doi: 10.2337/diab.45.3.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niimi M, et al. Identification of GFAT1-L, a novel splice variant of human glutamine: fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase (GFAT1) that is expressed abundantly in skeletal muscle. J Hum Genet. 2001;46:566–571. doi: 10.1007/s100380170022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oki T, et al. cDNA cloning and mapping of a novel subtype of glutamine:fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase (GFAT2) in human and mouse. Genomics. 1999;57:227–234. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang Q, et al. Phosphorylation of human glutamine:fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase by cAMP-dependent protein kinase at serine 205 blocks the enzyme activity. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21981–21987. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001049200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olchowyz J, et al. Functional domains and interdomain communication in Candida albicans glucosamine-6-phosphate synthase. Biochem J. 2007;404:121–130. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu Y, et al. Phosphorylation of mouse glutamine-fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase 2 (GFAT2) by cAMP-dependent protein kinase increases the enzyme activity. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:29988–29993. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401547200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hardie DG. Role of AMP-activated protein kinase in the metabolic syndrome and in heart disease. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Y, et al. Identification of a novel serine phosphorylation site in human glutamine:fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase isoform 1. Biochemistry. 2007;46:13163–13169. doi: 10.1021/bi700694c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eguchi S, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase phosphorylates glutamine : fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase 1 at Ser243 to modulate its enzymatic activity. Genes Cells. 2009;14:179–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2008.01260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheung WD, Hart GW. AMP-activated protein kinase and p38 MAPK activate O-GlcNAcylation of neuronal proteins during glucose deprivation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:13009–13020. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801222200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luo B, et al. Chronic hexosamine flux stimulates fatty acid oxidation by activating AMP-activated protein kinase in adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:7172–7180. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607362200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hresko RC, et al. Glucosamine-induced insulin resistance in 3T3-L1 adipocytes is caused by depletion of intracellular ATP. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:20658–20668. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.20658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin Y, Sun Z. Current views on type 2 diabetes. J Endocrinol. 2010;204:1–11. doi: 10.1677/JOE-09-0260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Housley MP, et al. O-GlcNAc regulates FoxO activation in response to glucose. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:16283–16292. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802240200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vosseller K, et al. Elevated nucleocytoplasmic glycosylation by O-GlcNAc results in insulin resistance associated with defects in Akt activation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:5313–5318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072072399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park SY, et al. O-GlcNAc modification on IRS-1 and Akt2 by PUGNAc inhibits their phosphorylation and induces insulin resistance in rat primary adipocytes. Exp Mol Med. 2005;37:220–229. doi: 10.1038/emm.2005.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Macauley MS, et al. Elevation of global O-GlcNAc levels in 3T3-L1 adipocytes by selective inhibition of O-GlcNAcase does not induce insulin resistance. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:34687–34695. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804525200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Slawson C, et al. Perturbations in O-linked beta-N-acetylglucosamine protein modification cause severe defects in mitotic progression and cytokinesis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:32944–32956. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503396200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McClain DA, et al. Altered glycan-dependent signaling induces insulin resistance and hyperleptinemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:10695–10699. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152346899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robinson KA, et al. Reduction of O-GlcNAc protein modification does not prevent insulin resistance in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292:E884–E890. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00569.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kreppel LK, et al. Dynamic glycosylation of nuclear and cytosolic proteins. Cloning and characterization of a unique O-GlcNAc transferase with multiple tetratricopeptide repeats. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:9308–9315. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.14.9308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang X, et al. Phosphoinositide signalling links O-GlcNAc transferase to insulin resistance. Nature. 2008;451:964–969. doi: 10.1038/nature06668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Whelan SA, et al. Regulation of the O-linked beta-N-acetylglucosamine transferase by insulin signaling. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:21411–21417. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800677200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Federici M, et al. Insulin-dependent activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase is impaired by O-linked glycosylation modification of signaling proteins in human coronary endothelial cells. Circulation. 2002;106:466–472. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000023043.02648.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ball LE, et al. Identification of the major site of O-linked beta-N-acetylglucosamine modification in the C terminus of insulin receptor substrate-1. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:313–323. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500314-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Klein AL, et al. O-linked N-acetylglucosamine modification of insulin receptor substrate-1 occurs in close proximity to multiple SH2 domain binding motifs. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:2733–2745. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900207-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Whelan SA, et al. Regulation of Insulin Receptor 1 (IRS-1)/AKT Kinase Mediated Insulin Signaling by O-linked {beta}-N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) in 3T3-L1 Adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2009 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.077818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gandy JC, et al. Akt1 is dynamically modified with O-GlcNAc following treatments with PUGNAc and insulin-like growth factor-1. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:3051–3058. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.04.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dentin R, et al. Hepatic glucose sensing via the CREB coactivator CRTC2. Science. 2008;319:1402–1405. doi: 10.1126/science.1151363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clark RJ, et al. Diabetes and the accompanying hyperglycemia impairs cardiomyocyte calcium cycling through increased nuclear O-GlcNAcylation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:44230–44237. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303810200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lehman DM, et al. A single nucleotide polymorphism in MGEA5 encoding O-GlcNAc-selective N-acetyl-beta-D glucosaminidase is associated with type 2 diabetes in Mexican Americans. Diabetes. 2005;54:1214–1221. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.4.1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.DeBerardinis RJ. Is cancer a disease of abnormal cellular metabolism? New angles on an old idea. Genet Med. 2008;10:767–777. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31818b0d9b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang T, et al. Aerobic glycolysis during lymphocyte proliferation. Nature. 1976;261:702–705. doi: 10.1038/261702a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vander Heiden MG, et al. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009;324:1029–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yeluri S, et al. Cancer's craving for sugar: an opportunity for clinical exploitation. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2009;135:867–877. doi: 10.1007/s00432-009-0590-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eagle H, et al. The growth response of mammalian cells in tissue culture to L-glutamine and L-glutamic acid. J Biol Chem. 1956;218:607–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Deberardinis RJ, et al. Brick by brick: metabolism and tumor cell growth. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2008;18:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Matsuzaki H, et al. Hyperammonemia in multiple myeloma. Acta Haematol. 1990;84:130–134. doi: 10.1159/000205049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Donadio AC, et al. Antisense glutaminase inhibition modifies the O-GlcNAc pattern and flux through the hexosamine pathway in breast cancer cells. J Cell Biochem. 2008;103:800–811. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yousefi S, et al. Increased UDP-GlcNAc:Gal beta 1–3GaLNAc-R (GlcNAc to GaLNAc) beta-1, 6-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase activity in metastatic murine tumor cell lines. Control of polylactosamine synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:1772–1782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Slawson C, et al. Increased N-acetyl-beta-glucosaminidase activity in primary breast carcinomas corresponds to a decrease in N-acetylglucosamine containing proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1537:147–157. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(01)00067-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Caldwell SA, et al. Nutrient sensor O-GlcNAc transferase regulates breast cancer tumorigenesis through targeting of the oncogenic transcription factor FoxM1. Oncogene. 2010 doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dang CV. Rethinking the Warburg Effect with Myc Micromanaging Glutamine Metabolism. Cancer Res. 2010 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim J, et al. Global identification of Myc target genes reveals its direct role in mitochondrial biogenesis and its E-box usage in vivo. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1798. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Morrish F, et al. c-Myc activates multiple metabolic networks to generate substrates for cell-cycle entry. Oncogene. 2009;28:2485–2491. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chou TY, et al. Glycosylation of the c-Myc transactivation domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:4417–4421. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vervoorts J, et al. The ins and outs of MYC regulation by posttranslational mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:34725–34729. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600017200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kamemura K, et al. Dynamic interplay between O-glycosylation and O-phosphorylation of nucleocytoplasmic proteins: alternative glycosylation/phosphorylation of THR-58, a known mutational hot spot of c-Myc in lymphomas, is regulated by mitogens. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:19229–19235. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201729200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li X, et al. O-linked N-acetylglucosamine modification on CCAAT enhancer-binding protein beta: role during adipocyte differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:19248–19254. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.005678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yang WH, et al. Modification of p53 with O-linked Nacetylglucosamine regulates p53 activity and stability. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1074–1083. doi: 10.1038/ncb1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shafi R, et al. The O-GlcNAc transferase gene resides on the X chromosome and is essential for embryonic stem cell viability and mouse ontogeny. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:5735–5739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100471497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.O'Donnell N, et al. Ogt-dependent X-chromosome-linked protein glycosylation is a requisite modification in somatic cell function and embryo viability. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:1680–1690. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.4.1680-1690.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Masson E, et al. Hyperglycemia and glucosamine-induced mesangial cell cycle arrest and hypertrophy: Common or independent mechanisms? IUBMB Life. 2006;58:381–388. doi: 10.1080/15216540600755980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bannon JH, Mc Gee MM. Understanding the role of aneuploidy in tumorigenesis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2009;37:910–913. doi: 10.1042/BST0370910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dehennaut V, et al. Identification of structural and functional O-linked N-acetylglucosamine-bearing proteins in Xenopus laevis oocyte. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:2229–2245. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700494-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang Z, et al. Extensive crosstalk between O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation regulates cytokinesis. Sci Signal. 2010;3:ra2. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang Z, et al. Enrichment and site mapping of O-linked Nacetylglucosamine by a combination of chemical/enzymatic tagging, photochemical cleavage, and electron transfer dissociation mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:153–160. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900268-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ferrari S. Protein kinases controlling the onset of mitosis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:781–795. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5515-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Slawson C, et al. A mitotic GlcNAcylation/phosphorylation signaling complex alters the posttranslational state of the cytoskeletal protein vimentin. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:4130–4140. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-11-1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cheung WD, et al. O-linked beta-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase substrate specificity is regulated by myosin phosphatase targeting and other interacting proteins. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:33935–33941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806199200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Housley MP, et al. A PGC-1alpha-O-GlcNAc transferase complex regulates FoxO transcription factor activity in response to glucose. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:5148–5157. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808890200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wang Z, et al. Cross-talk between GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation: site-specific phosphorylation dynamics in response to globally elevated O-GlcNAc. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:13793–13798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806216105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dias WB, et al. Regulation of calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase IV by O-GlcNAc modification. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:21327–21337. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.007310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zachara NE, et al. Dynamic O-GlcNAc modification of nucleocytoplasmic proteins in response to stress. A survival response of mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:30133–30142. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403773200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Matthews JA, et al. Glucosamine-induced increase in Akt phosphorylation corresponds to increased endoplasmic reticulum stress in astroglial cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2007;298:109–123. doi: 10.1007/s11010-006-9358-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kang JG, et al. O-GlcNAc protein modification in cancer cells increases in response to glucose deprivation through glycogen degradation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:34777–34784. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.026351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Guinez C, et al. 70-kDa-heat shock protein presents an adjustable lectinic activity towards O-linked N-acetylglucosamine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;319:21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.04.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Du XL, et al. Hyperglycemia-induced mitochondrial superoxide overproduction activates the hexosamine pathway and induces plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 expression by increasing Sp1 glycosylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:12222–12226. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.22.12222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.D'Apolito M, et al. Urea-induced ROS generation causes insulin resistance in mice with chronic renal failure. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:203–213. doi: 10.1172/JCI37672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]