Abstract

The sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectins (siglecs) comprise a family of receptors that are differentially expressed on leukocytes and other immune cells. The restricted expression of several siglecs to one or a few cell types makes them attractive targets for cell-directed therapies. The anti-CD33 (Siglec-3) antibody Gemtuzumab (Mylotarg™) is approved for treatment of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and antibodies targeting CD22 (Siglec-2) are currently in clinical trials for treatment of B cell non-Hodgkins lymphomas and autoimmune diseases. Because siglecs are endocytic receptors, they are well suited for a ‘Trojan horse’ strategy, whereby therapeutic agents conjugated to an antibody, or multimeric glycan ligand, bind to the siglec and are efficiently carried into the cell. Although the rapid internalization of unmodified siglec antibodies reduces their utility for induction of antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) or complement-mediated cytotoxicity (CDC), antibody binding of Siglec-8, Siglec-9, and CD22 have been demonstrated to induce apoptosis of eosinophils, neutrophils, and depletion of B cells, respectively. Here we review the properties of siglecs that make them attractive for cell-targeted therapies.

Introduction

In the mid-1980s, CD33 and CD22 were identified as markers of myeloid leukemias1, 2 and B cell lymphomas3-6, respectively. Nearly a decade later, the two markers were designated members of a homologous family of sialic-acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectins7-9, now called siglecs. There are currently 14 known siglecs in humans, and 9 in mouse, which are predominantly expressed on myeloid and lymphoid cells (Table 1)10-12. Four of the siglecs are highly conserved in all mammalian species: sialoadhesin (Siglec-1), CD22 (Siglec-2), myelin associated glycoprotein (MAG, Siglec-4) and Siglec-15. The rest are classified as CD33 (Siglec-3) related siglecs, which comprise a rapidly evolving sub-family. With the anti-CD33 immunotoxin Gemtuzumab™ approved for treatment of AML, and several CD22 antibodies in clinical trials for treatment of B cell NHL (non-Hodgkins lymphoma), siglecs are gaining increasing attention as targets for cell-directed immunotherapy12, 13. This review will describe the properties of siglecs that make them attractive targets, and the strategies being taken to develop siglec-based therapeutics.

Table 1.

Summary of structural and functional properties of the siglec family

| Siglec (other names) |

Murine ortholog or paralog |

Structure | Sialoside Preference* |

Cell type Expression** |

Disease relevance | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # Ig domains |

Tyrosine motifs |

DAP-12 Binding |

||||||

| Sialoadh esin (SAD, Sn, Siglec-1) |

Sialoadhesin (mSiglec-1, mSn) |

17 | None | No |  |

tissu macrophages (Activated monocytes) |

HIV-1 infection, Trypanosoma cruzi internalization |

11, 24, 71, 92- 94 |

| CD22 (Siglec-2) |

mCD22 (mSiglec-2) |

7 | ITIM ITIM-like Grb2 |

No |  |

B cells | Lymphoma, leukemia, SLE, Rheumatoid arthritis |

11, 47, 53, 55- 57, 95 |

| CD33 (Siglec-3) |

mCD33 (mSiglec-3) |

2 | ITIM ITIM-like |

Yes for mCD33? |

|

Monocytes, basophils, CD34+ cells, dendritic cells, macrophages, mast cells, neutrophils (granulocytes, myeloid progenitors) |

Acute Myelogenouse Leukemia (AML) |

11, 37, 38, 93, 94, 96, 97 |

| MAG (Siglec-4) |

mMAG (mSiglec-4) |

5 | FYN- kinase site |

No |  |

oligodendrocytes, Schwann cells |

93, 94, 98 |

|

| Siglec-5 | - | 4 | ITIM ITIM-like |

No |  |

neutrophils, monocytes, basophils, CD34+ cells, macrophages, mast cells (B cells) |

Rheumatoid arthritis, N. maningitides infection |

11, 93, 97, 99 |

| Siglec-6 | - | 3 | ITIM ITIM-like |

No |  |

Basophils, mast cells, placental trophoblasts (B cells) |

11, 94, 100 |

|

| Siglec-7 | - | 3 | ITIM ITIM-like |

No | NK cells, dendritic cells, monocytes, CD8+ T cells (monocytes) |

C. jejuni infection Cancer |

11, 40, 101 |

|

| Siglec-8 | Siglec-F | 3 | ITIM ITIM-like |

No |  |

eosinophils, mast cells (basophils) |

Eosinophilia, allergy | 11, 68 |

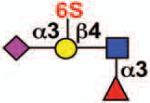

| Siglec-9 | - | 3 | ITIM ITIM-like |

No |  |

monocytes, neutrophils, dendritic cells, CD34+ cells, CD8+ T cells (NK cells) |

Rheumatoid arthritis |

11, 76, 97 |

| Siglec-10 | Siglec-G | 5 | ITIM ITIM-like Grb2 |

No |  |

B cells, CD34+ cells, dendritic cells, monocytes, NK cells (eosinophils) |

Lymphoma, leukemia, SLE, Rheumatoid arthritis, eosinophilia, allergy |

11, 93, 97, 102 |

| Siglec-11 | - | 5 | ITIM ITIM-like |

No |  |

Monocytes, macrophages, brain microglia |

103 | |

| Siglec-14 | - | 3 | None | Yes |  |

Not determined, but expected to be similar to Siglec-5 based on sequence homology |

99 | |

| Siglec-15 | mSiglec-15 | 2 | None | Yes |  |

macrophages, monocytes, dendritic cells |

104 | |

| Siglec-16 | - | 2 | None | Yes |  |

macrophages (brain microglia) |

10 | |

| - | Siglec-E | 3 | ITIM ITIM-like |

- |  |

neutrophils, monocytes, dendritic cells |

11 | |

| - | Siglec-H | 2 | None | Yes | plasmatoid dendritic cells (macrophages) |

11 | ||

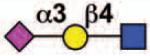

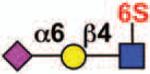

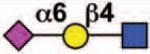

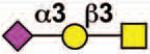

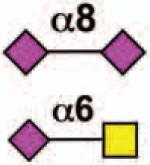

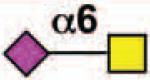

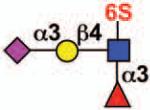

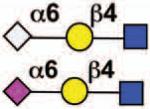

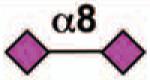

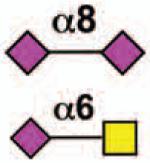

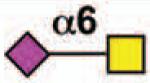

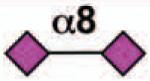

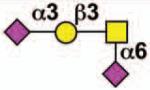

Key:  NeuAc

NeuAc  NeuGc

NeuGc  Gal

Gal  GalNAc

GalNAc  GlcNAc

GlcNAc  Fuc

Fuc  Sulfate

Sulfate

Sialoside preferences are taken from references cited, data from the Consortium for Functional Glycomics http://www.functionalglycomics.org, or inferred from the binding preferences of highly homologous siglecs. Carbohydrate sequences shown refer to preferences of the human counterparts, with the expection of Siglec-E.

The siglec family

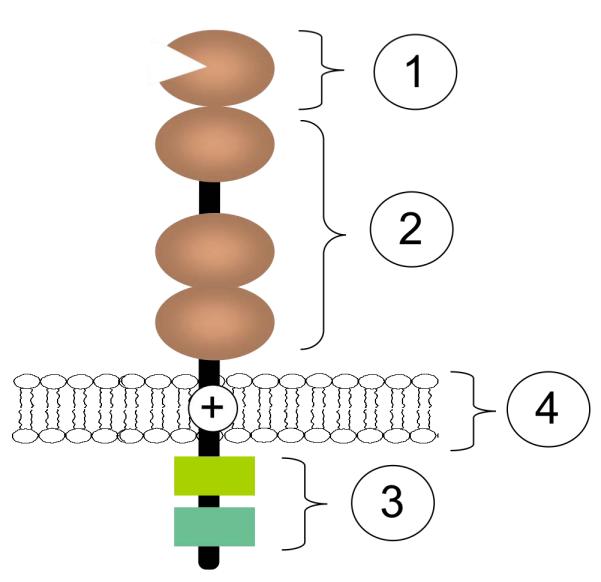

Structural features of the siglecs relevant to their function are illustrated in Figure 1. Each siglec contains an N-terminal ‘V-set’ Ig domain that binds sialic acid-containing ligands, followed by a variable number (1-16) of ‘C2-set’ Ig domains that extend the ligand binding site away from the membrane surface (See Table 1). Each siglec exhibits distinct and varied specificity for sialoside sequences on glycoprotein and glycolipid glycans that are expressed on the same cell (in cis) or on adjacent cells (in trans)11. The cytoplasmic domains of CD22 and most CD33-related siglecs contain ITIM (immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif) and ITIM-like motifs involved in regulation of cell signaling. Several other siglecs (Siglecs-14-16 and murine Siglec-H) have no tyrosine motifs, but contain a positively charged trans-membrane spanning region. A charged residue permits association with the adapter protein DAP12 (12 kDa DNAX-activating protein), which bears a cytoplasmic ITAM (immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif) that imparts both positive and negative signals11, 12.

Figure 1. Common structural features of siglecs.

The N-terminal ‘V-set’ Ig domain (1) contains a conserved arginine residue that confers sialic acid-binding ability. This domain is followed by a variable number (1-16) of ‘C2-set’ Ig domains (2). In the cytosolic domain, most siglecs contain some combination of tyrosine motifs, including ITIM, ITIM-like, Grb2-binding, and Fyn kinase sites (3). Siglecs-14, -15, and -16 contain a positively charged residue in the transmembrane spanning region (4) that enables association with the ITAM-bearing adaptor protein, DAP-12. It is speculated that these may have evolved to counteract ITIM-bearing siglecs.11 With 99% sequence identity in the two first N-terminal Ig domains, Siglecs-5 and -14 are believed to be such paired receptors.

As a family, the siglecs are most commonly known as regulators of immune cell signaling11, 12, 14, 15. Best understood is CD22, which is expressed predominantly on B cells. CD22 regulates B cell receptor (BCR) signaling through the ITIM, ITIM-like and Grb2 tyrosine motifs in its cytoplasmic domain14, 15. CD22 is localized in clathrin-coated pits, and undergoes constitutive endocytosis through a clathrin-dependent mechanism that requires cytoplasmic ITIM motifs16-20. Following antibody binding to BCR, a membrane activation complex is formed that moves to clathrin-rich domains prior to endocytosis21, 22, bringing it into close proximity with CD22 16, 17, 22. These observations suggest that the endocytic function of CD22 is related to its activity in BCR signaling.

The majority of CD33-related siglecs have also been implicated in regulation of cell signaling of leukocytes through cytoplasmic ITIM, ITIM-like and ITAM motifs11, 12. Sialoadhesin and the majority of the CD33-related siglecs also exhibit endocytic activity. Siglecs on macrophages, dendritic cells and other myeloid cells are believed to function as endocytic receptors in innate immune recognition of sialylated pathogens, including both bacteria (e.g. N. meningitidis) and viruses (e.g. HIV)23-25. Endocytosis of CD33-related siglecs can be regulated by phosphorylation of their ITIM and ITIM-like motifs 20, 26-28. However, in contrast to CD22, murine Siglec-F and CD33 undergo endocytosis by a clathrin-independent mechanism that traffics to endosomes and lysosomes20, 27. Recent evidence suggests that endocytosis of CD33 is regulated by ubiquitination following ITIM phosphorylation28. Studies with Siglec-H show that its endocytosis and cell surface expression are also regulated through association with DAP-1229, suggesting another mechanism of endocytosis for siglecs that interact with this adapter protein. Although sialoadhesin is devoid of tyrosine motifs and does not associate with DAP-12, it has been demonstrated to mediate endocytosis of sialylated bacterial and viral pathogens through a clathrin-mediated mechanism23, 25. Elucidating the detailed mechanisms of endocytosis of the siglecs will undoubtedly shed further light on their functions in regulation of cell signaling and innate immunity, as well as their suitability as targets for cell-directed therapeutics.

Perspectives on targeting siglecs for cell-directed therapies

The potential of CD33 and CD22 as targets for immunotherapy was recognized soon after their identification as markers of acute myeloid leukemia and B cell lymphoma and leukemias, respectively. Initial efforts focused on development of immunotoxins using anti-CD33 or anti-CD22 antibodies conjugated to the ricin B chain or saporin toxin1, 30, 31. The restricted expression of CD33 on myeloid cells, and CD22 on B lymphocytes, was a primary consideration, since the toxins would be targeted to these cells, thereby reducing toxicity to other cells and tissues. In hindsight, these siglecs are also well suited for an immunotoxin approach, since antibody binding induces their internalization19, 32-35, carrying the toxin into the cell. Ultimately, this was a critical factor in the success of the approved drug Gemtuzumab for treatment of AML, since it is an anti-CD33-calicheamycin immunotoxin that requires endocytosis for cell killing.

In addition to the treatment of lymphomas and leukemia, siglecs are also viewed as targets for development of cell-directed therapies against leukocytes that mediate inflammatory, autoimmune, allergic and infectious diseases. Various approaches currently being considered and employed for targeting siglec-bearing cells are illustrated in Box 1. While anti-siglec antibodies continue to be the primary focus for pursuing cell-directed therapies, the mechanisms of cell killing vary. Naked antibodies can, in principle, activate effector cell-mediated antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) or complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC). However, as described above, siglecs as endocytic receptors are well suited for delivery of toxins or chemotherapeutics. Antibodies to some siglecs have been found to induce apoptosis, providing an opportunity to develop antibody therapeutics that kill the target cell directly. While still at an early stage, synthetic glycan ligands show promise as an alternative to antibodies for targeting siglecs and delivering therapeutic cargo to cells that express them. The sections that follow focus on the status of, and prospects for, development of siglec-based therapeutics for treating malignant leukocytes (lymphomas and leukemias), and treating diseases mediated by normal immune cells.

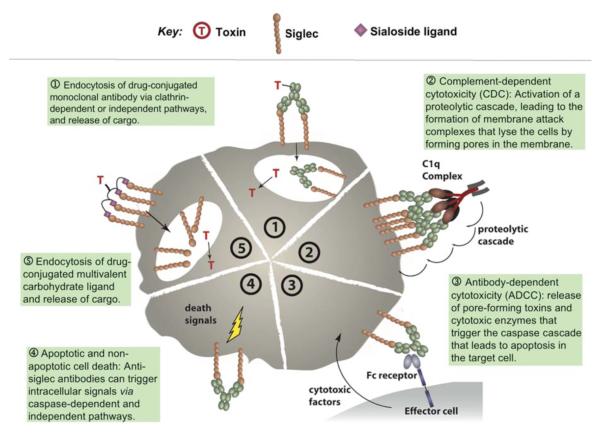

Box 1. Mechanisms of Siglec-targeting therapy for immune cell diseases.

Efforts to target siglecs for therapeutic purposes take advantage of cytotoxic mechanisms depicted here. Immunotoxins (1) are currently been used to target both CD22 (Siglec-2) and CD33 (Siglec-3) for the treatment of certain hematological malignancies. Due to rapid internalization of siglecs, CDC (2) is not likely to play a dominant role, although it has not been ruled out, since it is a common and potent antibody-mediated mode of cell killing. The mechanism of the naked anti-CD22 antibody Epratuzumab is still unclear, although significant ADCC (3) is induced upon binding. Antibodies directed to Siglec-8 or Siglec-9 induce apoptosis (4) of eosinophils or neutrophils, respectively. Carbohydrate-based delivery of toxic cargo (5) has been demonstrated in vitro with B cells using a high-affinity CD22 ligand, and further application of this strategy is underway.

Siglecs as targets for therapy of immune cell-based diseases

Acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) depletion therapy: targeting CD33

The primary goal for treatment of AML is to deplete the tumor cells without killing the host. CD33 was identified as a target for immunotherapy upon the demonstration that the receptor was expressed on myeloblasts of 90% of all patients suffering from AML. Gemtuzumab ozogamicin (GO, Mylotarg™), a calicheamicin-conjugated humanized murine anti-CD33, was approved for cell depletion therapy in AML patients in 2000 (Table 2)36, 37. Binding and endocytosis of GO by AML cells is followed by intracellular release of calicheamycin and disruption of DNA synthesis causing cell death. It has been recently reported that anti-CD45 enhances the in vitro, efficacy of GO, but not calicheamicin alone, and significantly extends survival rates in murine models of human AML compared to treatment with either anti-CD45 or GO alone.38 This effect may be explained by enhanced uptake of GO considering the observation of anti-CD45 dependent increased internalization of an unconjugated anti-CD33, but additional contributions from CD45 signaling or activation of Fc receptor signaling have not been ruled out. CD33 is expressed on many myeloid cells (e.g. monocytes, neutrophils, other granulocytes and myeloid precursors), resulting in severe myelosuppression and neutropenia in all patients. However, since CD33 is not expressed on pluripotent hematopoietic stem cells,39 these cells replenish the myeloid cell compartment over time. Thus, despite the rather broad cell type expression of CD33, the side effects resulting from temporary depletion of normal CD33-expressing myeloid cells are manageable.

Table 2.

Siglec-targeted antibodies in clinical development for treatment of immune cell diseases

| Antibody | Target | Construct | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg™) |

CD33 | Humanized murine IgG conjugated to calicheamicin |

Approved for AML |

| CMC-544 | CD22 | IgG4 conjugated to calecheamicin |

Phase II/III for NHL |

| BL22 | CD22 | Recombinant Ig- pseudomonas toxin conjugate |

Phase II for hairy cell leukemia |

| Epratuzumab | CD22 | Humanized IgG1 | Phase III |

Although Siglec-9 exhibits a similar expression profile to CD33, there is no evidence at present to suggest that it would be a better target for cell depletion therapy26. Siglec-7 is also expressed on AML cells. As a proof of principle for Siglec-7 directed immunotherapy, fluorescent dye-loaded immunocolloidal particles bearing anti-Siglec-7 antibodies conjugated to the surface have been constructed. These nanoparticles bound to and were taken up by Siglec-7 expressing mouse embryonic fibroblasts in a Siglec-7 dependent manner, suggesting another drug targeting approach.40 In an alternative CD33-targeting approach, natural killer cells bearing a recombinant chimeric anti-CD33 bearing T cell receptor was able to elicit specific lysis of an AML cell line41. However, this interesting approach does not readily translate to a clinical path for treatment of AML since it involves recombinant proteins in NK cells.

B cell depletion therapy targeting CD22 (Siglec-2)

CD22 (Siglec-2) has restricted expression on mature B cells, which lose CD22 expression upon differentiation to plasma cells.15 Since its identification as a marker for B cell malignancies3, 4, 6, CD22 has been pursued as a target for cell depletion therapy, with ongoing clinical trials for three anti-CD22 antibodies currently in clinical development (Table 2). In the meantime, B cell depletion therapy has become a well-established treatment for NHL as a result of the clinical success of Rituxan, an anti-CD20 B cell-specific antibody, approved by the FDA in 1997. Rituxan is a native antibody that relies on CDC and ADCC-mediated immune responses to ablate NHL cells. Despite the success of Rituxan, there is ample room for improvement. While first-time treatment of NHL patients with Rituxan plus standard chemotherapy (CHOP) achieves 90% response rates, and 4 year survival of >80% of the patients, most patients eventually relapse, and 50-60% of relapsed patients do not respond to Rituxan42-45. Consequently, there is a need for improved methods of treatment of NHL patients, particularly for agents that can work synergistically with Rituxan. Currently there are three anti-CD22 antibodies in clinical trials for treatment of B cell malignancies, two that are immunotoxins (BL22 and CMC-544) and one that is a native antibody (Epratuzumab).

BL22 is an anti-CD22 conjugated to a Pseudomonas exotoxin. In phase I/II clinical trials investigating the efficacy of BL22 against refractory hairy cell leukemia, 80% of patients showed complete or partial remission46. Recently, BL22 cytotoxicity was compared with a similar anti-CD19 immunotoxin in a panel of human lymphoma cell lines, and shown to have 10-100-fold lower IC50 values, despite 4-9-fold lower levels of CD22 expression compared to CD19.47 Although both conjugates were endocytosed, the improved cytotoxicity of BL22 correlated with efficient endocytosis by CD22, aided by rapid replenishment of cell surface CD22 from intracellular pools.47 These results underscore the utility of CD22 as a target that can carry toxic cargo into the cell.

CMC-544 is a humanized IgG4 anti-CD22 antibody conjugated to the chemotoxin calicheamicin. Its construction is analogous to the anti-CD33 based Mylotarg™ approved for the treatment of AML, where calicheamycin is conjugated to the antibody via an acid-labile bond, requiring endocytosis into acidic compartments of the cell to release the active agent. Thus, like BL22, it has been designed to optimally use the endocytic activity of CD22. CMC-544 has demonstrated dramatic efficacy in murine models of human NHL48, 49 and ALL50. It shows strong synergy with Rituxan in a disseminated model of NHL48, and shows superior activity to Rituxan in regression of established subcutaneous ALL tumors50. CMC-544 is currently in Phase II/III trials for treatment of NHL and diffuse large B cell lymphoma.

Epratuzumab is a humanized IgG1 anti-CD22 antibody that is being pursed in clinical trials for treatment of NHL and Systemic lupus erythamatosis (SLE)51. As a single agent, Epratuzumab produces only a modest reduction of B cells52, 53, perhaps not surprising since it is a native antibody that is rapidly taken up by B cells54. In SLE patients, Epratuzumab was found to deplete CD27− B cells, which represent naïve and transitional B cells, as opposed to memory B cells and plasmablasts55, although the mechanism is not known. Combination therapy with Rituxin and Epratuzumab have been ongoing, and favorable results from an international, multicenter phase 2 study of patients with follicular NHL or small lymphocytic lymphoma were reported recently.52 This study included patients with relapsed/refractory, indolent NHL, following previous chemotherapy; the majority of patients achieved at least an objective response, with many of these also achieving durable, complete responses. A recent study describes treatment of a B lymphoma xenograft in mice with an 90Y-conjugated Epratuzumab in combination with the unconjugated anti-CD20 Veltuzumab.53 While 90Y-Epratuzumab alone demonstrated efficacy, the therapy was greatly improved by the inclusion of Veltuzumab. The mechanism of action and possible synergism of this treatment has not been fully elucidated, although it is expected that the Epratuzumab is efficiently endocytosed by CD22, causing an accumulation of radioisotope in the cell. In an antibody-tethered combination therapy approach, the Fab fragments of anti-CD22 and whole CD20 antibodies were covalently linked56. Interestingly, this conjugate does not undergo endocytosis, despite engaging CD22. Presumably the retention of CD20 on the cell surface is dominant over the endocytic behavior of CD22. This phenomenon suggests a different mode of action from treating with the two antibodies separately, which is supported by the more potent inhibition of cell proliferation by the covalent conjugate compared to administration of Epratuzumab and Veltuzumab as separate entities.

Although Epratuzumab is not efficient at depletion of normal B cells, a panel of antibodies that bind to different CD22 epitopes have recently been evaluated, revealing that antibodies that block ligand binding cause dramatic depletion of both normal B cells and B lymphoma cells57. Since the antibodies do not cause apoptosis of B cells in vitro, it is postulated that blocking ligand binding affects the half-life and turnover of the cells. The results suggest a novel approach to B cell depletion using antibodies that block the ligand-binding site of CD22.

In recent years B cells have been increasingly appreciated for their role in initiation and maintenance of autoimmune disease, suggesting the potential for B cell depletion therapy in breaking the inflammatory cycle in these diseases58-61. Approval of Rituxan for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in combination with methotrexate has had a major impact on treatment of the disease and stimulated investigation on the role of B cells in various autoimmune diseases. Epratuzumab is currently under investigation for treatment of SLE55, and it is likely that other CD22-targeted therapeutics will be investigated in autoimmune disease as they progress in clinical trials.

Targeting Siglec-8 on eosinophils

Eosinophils express Siglec-8 in a highly cell-type restricted manner, with basophils showing only weak expression (Table 1). While there is no murine ortholog, Siglec-F has been documented as a functional paralog, due to its restricted expression on eosinophils, and the unique specificity of both Siglec-8 and Siglec-F for a sulfated-sialylated glycan ligand (6-sulfo-sialyl Lewis X)62, 63. Genetic ablation of Siglec-F in mice results in lung, blood and bone marrow eosinophilia when challenged with an allergen, which is consistent with the observed upregulation of Siglec-F and its ligands upon allergen challenge in wild-type mice.64 Above-normal concentrations of eosinophils and enhanced eosinophil responses in the knock-out mice established Siglec-F as a negative regulator of eosinophil activation in vivo. Anti-Siglec-8 antibodies, in the presence of secondary antibodies, induce apoptosis of eosinophils by triggering signaling through a caspase-dependent pathway65. Interestingly, it was shown that eosinophil sensitivity to apoptosis was increased by cytokines such as IL-5, which normally promote eosinophil survival. It is significant that this mechanism involves the cell signaling function of Siglec-8, suggesting that native antibodies could be used for eosinophil depletion in vivo by a mechanism that does not involve CDC or ADCC. Antibodies to murine Siglec-F similarly cause apoptosis of murine eosinophils, and in vivo can induce a marked depletion of eosinophils from the peripheral blood of mice with eosinophilia66. The treatment has no significant effect on other leukocytes. Siglec-F antibodies were also used to successfully treat eosinophilic inflammation in a mouse model of oral egg ovalbumin-induced inflammation in the gastro-intestinal mucosa.67 Both eosinophil numbers and gastro-intenstinal mucosal damage were significantly reduced in anti-Siglec-F treated mice. Thus, Siglec-8 may represent an attractive target for the treatment of hypereosinophilia, as well as allergic disorders involving eosinophils. Considering the routine use of intravenously-administered immunoglobulins (IVIg) to treat inflammation, it is noteworthy that autoantibodies including anti-Siglec-8 are found in these preparations, suggesting therapeutic relevance for autoimmune and allergic disorders such as Churg-Strauss syndrome.68 There is also evidence for the use of anti-Siglec-8 antibodies to target mast cells for the inhibition of FcεRI-dependent mediator release. While anti-Siglec-8 does not induce apoptosis of mast cells, it was shown to inhibit calcium flux, release of histamine and prostaglandin-D2, and bronchial smooth muscle contraction upon stimulation with anti- FcεRI.69 Interestingly, this inhibition was found to be dependent on the ITIM of Siglec-8.

Restricted expression of sialoadhesin on tissue macrophages

Sialoadhesin (Siglec-1) exhibits highly restricted expression on subsets of resident tissue and inflammatory macrophages and activated monocytes24, 70, 71. While there has been little attempt to date to directly target sialoadhesin, this siglec has been implicated for its potential to target these cells. Macrophages are believed to be critical effector cells in the inflammation associated with autoimmune disease, and the efficacy of Rituxan in rheumatoid arthritis is believed to result from the ablation of B cells, which are responsible for activation of these macrophages59. Similarly, the secretion of a macrophage-activating factor, versican, from tumor cells promotes an inflammatory microenvironment that aids in tumor metastasis.72 Thus, targeting sialoadhesin-bearing macrophages might have impact in the treatment of inflammatory responses that promote rheumatoid arthritis and tumor metastasis.

Sialoadhesin is also gaining interest for its role in viral infections24, 25, 71. An increase in Sialoadhesin expression on CD14+ monocytes has been shown to correlate with HIV-1 viral load in humans, both by RT-PCR analysis and flow cytometry. Sialoadhesin binds HIV-1 directly, and is responsible for trans-infection of other cells24, 71. One recent report suggests targeting of sialoadhesin as a vaccine strategy to deliver antigens for presentation to T cells, taking advantage of the localization of macrophages on spleen and lymph nodes, and the rapid endocytic activity of sialoadhesin73.

Targeting Siglec-9 for inflammatory disorders

Siglec-9 is primarily expressed on monocytes, neutrophils, and dendritic cells. It was recently found that anti-Siglec-9 antibodies induce apoptosis in neutrophils,74 and that this cytotoxicity is enhanced in the presence of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as GM-CSF.75 While in the absence of cytokines the effect is caspase-dependent, the cytokine-enhanced effect is caspase-independent, but involves reactive oxygen species (ROS). These results suggest that in vivo, the cell-killing effect may be more potent in hyperinflammatory microenvironments. This phenomenon may already play a role in the routine treatment of autoimmune diseases with IVIg. Autoantibodies, including anti-Siglec-9, have been identified in IVIg, and intact, but not anti-Siglec-9-depleted, IVIg was shown to induce neutrophil cytotoxicity in vitro.76 Consistent with the previous study using anti-Siglec-9, IVIg-induced neutrophil cytotoxicity was enhanced in the presence of pro-inflammatory cytokines.76 These findings have important implications for the clinical use of IVIg, by providing a deeper understanding of the mechanisms of action, and for the potential of targeting Siglec-9 specifically in the treatment of hyperinflammation.

Targeting siglecs with glycan ligands

The majority of the studies described above involve targeting of siglecs using anti-Siglec antibodies. Yet another emerging alternative is to target siglecs using synthetic glycan ligands. Initial attempts to bind synthetic multivalent ligands of CD22 to B cells revealed that CD22 constitutively binds to glycoproteins on the same cell (in cis), thereby masking exogenous ligand binding unless the cells are first treated with sialidase or periodate to destroy cell surface sialic acids77. Similar observations were made for other siglecs, and for a time it was believed that cis masking would preclude binding of synthetic ligands to siglecs on native cells78. However, it was subsequently found that synthetic glycan ligands of sufficient avidity could compete with cis ligands of CD22 on native B cells79-83. Polyacrylamide polymers containing pendent high-affinity ligands of CD22 or Siglec-F are bound and rapidly endocytosed by B cells and Siglec-F bearing cells, respectively20, 80. Conjugation of the endotoxin saporin to the CD22 ligand resulted in endocytosis and subsequent cell death by the Daudi, Raji and BJAB-K20 B cell lymphoma lines80. High valency of the polyacrylamide polymers is not necessarily required for ligand binding. Monovalent heterobifunctional ligands comprising a glycan ligand of CD22 covalently linked to an antigen (nitrophenol) are capable of assembling a complex on B cells between CD22 and a deca-, tetra-, or bi-valent anti-nitrophenol antibody (IgM, IgA or IgG, respectively), effectively producing an immune complex on the surface of the cell83. These early results are encouraging for the development of ligand-based approaches for targeting siglecs on myeloid and lymphoid cells. Particularly attractive from a pharmaceutical standpoint would be nanoparticles bearing siglec ligands. Ample precedence for this approach comes from well documented successes in the in vivo targeting of glycan-decorated liposomes and other nanoparticles to mannose-specific receptors on macrophages84-87, and sialyl-Lewis X-specific receptors (e.g. E-selectin) expressed on endothelial cells at sites of inflammation88-91.

Summary

The restricted expression of siglecs on myeloid and lymphoid cells, and rapid progress in understanding their roles as cell signaling and endocytic receptors have made them attractive targets for cell-directed therapeutics. Siglec-specific antibodies have been the primary tool for targeting siglecs in vivo, but glycan-based probes of siglecs show promise as an alternative method for targeting these receptors. Success with ongoing clinical trials and animal models will likely spur increased interest in development of therapeutics targeting this class of receptors.

Acknowledgment

This work was funded in part by NIH grants GM060938 & AI050143 (J.C.P.) and M.K.O. is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the American Cancer Society.

Footnotes

Competing interest statement. The authors declare they have no competing financial interests

References cited

- 1.Ball ED. In vitro purging of bone marrow for autologous marrow transplantation in acute myelogenous leukemia using myeloid-specific monoclonal antibodies. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1988;3:387–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drexler HG. Classification of acute myeloid leukemias--a comparison of FAB and immunophenotyping. Leukemia. 1987;1:697–705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen Z, et al. Immunological typing of acute lymphoblastic leukemia: concurrent analysis by flow cytofluorometry and immunocytology. Leuk Res. 1986;10:1411–1417. doi: 10.1016/0145-2126(86)90007-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mason DY, et al. Value of monoclonal anti-CD22 (p135) antibodies for the detection of normal and neoplastic B lymphoid cells. Blood. 1987;69:836–840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.May RD, et al. Selective killing of normal and neoplastic human B cells with anti-CD19- and anti-CD22-ricin A chain immunotoxins. Cancer Drug Deliv. 1986;3:261–272. doi: 10.1089/cdd.1986.3.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ziegler-Heitbrock HW, et al. Induction of features characteristic of hairy cell leukemia in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and prolymphocytic leukemia cells. Cancer Res. 1986;46:2172–2178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freeman SD, et al. Characterization of CD33 as a new member of the sialoadhesin family of cellular interaction molecules. Blood. 1995;85:2005–2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelm S, et al. Sialoadhesin, myelin-associated glycoprotein and CD22 define a new family of sialic acid-dependent adhesion molecules of the immunoglobulin superfamily. Curr Biol. 1994;4:965–972. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00220-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sgroi D, et al. CD22, a B cell-specific immunoglobulin superfamily member, is a sialic acid-binding lectin. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:7011–7018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cao H, et al. SIGLEC16 encodes a DAP12-associated receptor expressed in macrophages that evolved from its inhibitory counterpart SIGLEC11 and has functional and non-functional alleles in humans. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:2303–2315. doi: 10.1002/eji.200738078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crocker PR, et al. Siglecs and their roles in the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:255–266. doi: 10.1038/nri2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crocker PR, Redelinghuys P. Siglecs as positive and negative regulators of the immune system. Biochem Soc Trans. 2008;36:1467–1471. doi: 10.1042/BST0361467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.von Gunten S, Bochner BS. Basic and clinical immunology of Siglecs. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1143:61–82. doi: 10.1196/annals.1443.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walker JA, Smith KG. CD22: an inhibitory enigma. Immunology. 2008;123:314–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02752.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tedder TF, et al. CD22: A Multifunctional Receptor That Regulates B Lymphocyte Survival and Signal Transduction. Adv Immunol. 2005;88:1–50. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(05)88001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collins BE, et al. Ablation of CD22 in ligand-deficient mice restores B cell receptor signaling. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:199–206. doi: 10.1038/ni1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grewal PK, et al. ST6Gal-I restrains CD22-dependent antigen receptor endocytosis and Shp-1 recruitment in normal and pathogenic immune signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:4970–4981. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00308-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.John B, et al. The B cell coreceptor CD22 associates with AP50, a clathrin-coated pit adapter protein, via tyrosine-dependent interaction. J Immunol. 2003;170:3534–3543. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shan D, Press OW. Constitutive endocytosis and degradation of CD22 by human B cells. J Immunol. 1995;154:4466–4475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tateno H, et al. Distinct endocytic mechanisms of CD22 (Siglec-2) and Siglec-F reflect roles in cell signaling and innate immunity. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:5699–5710. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00383-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stoddart A, et al. Lipid rafts unite signaling cascades with clathrin to regulate BCR internalization. Immunity. 2002;17:451–462. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00416-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stoddart A, et al. Plasticity of B cell receptor internalization upon conditional depletion of clathrin. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:2339–2348. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-01-0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones C, et al. Recognition of sialylated meningococcal lipopolysaccharide by siglecs expressed on myeloid cells leads to enhanced bacterial uptake. Mol Microbiol. 2003;49:1213–1225. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rempel H, et al. Sialoadhesin expressed on IFN-induced monocytes binds HIV-1 and enhances infectivity. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1967. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vanderheijden N, et al. Involvement of sialoadhesin in entry of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus into porcine alveolar macrophages. J Virol. 2003;77:8207–8215. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.15.8207-8215.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Biedermann B, et al. Analysis of the CD33-related siglec family reveals that Siglec-9 is an endocytic receptor expressed on subsets of acute myeloid leukemia cells and absent from normal hematopoietic progenitors. Leuk Res. 2007;31:211–220. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2006.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walter RB, et al. ITIM-dependent endocytosis of CD33-related Siglecs: role of intracellular domain, tyrosine phosphorylation, and the tyrosine phosphatases, Shp1 and Shp2. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:200–211. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0607388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walter RB, et al. Phosphorylated ITIMs enable ubiquitylation of an inhibitory cell surface receptor. Traffic. 2008;9:267–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang J, et al. Characterization of Siglec-H as a novel endocytic receptor expressed on murine plasmacytoid dendritic cell precursors. Blood. 2006;107:3600–3608. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bregni M, et al. B-cell restricted saporin immunotoxins: activity against B-cell lines and chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells. Blood. 1989;73:753–762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ghetie MA, et al. Evaluation of ricin A chain-containing immunotoxins directed against CD19 and CD22 antigens on normal and malignant human B-cells as potential reagents for in vivo therapy. Cancer Res. 1988;48:2610–2617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Audran R, et al. Internalization of human macrophage surface antigens induced by monoclonal antibodies. J Immunol Methods. 1995;188:147–154. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(95)00213-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Engert A, et al. Resistance of myeloid leukaemia cell lines to ricin A-chain immunotoxins. Leuk Res. 1991;15:1079–1086. doi: 10.1016/0145-2126(91)90115-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Press OW, et al. Endocytosis and degradation of monoclonal antibodies targeting human B-cell malignancies. Cancer Res. 1989;49:4906–4912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Der Velden VH, et al. Targeting of the CD33-calicheamicin immunoconjugate Mylotarg (CMA-676) in acute myeloid leukemia: in vivo and in vitro saturation and internalization by leukemic and normal myeloid cells. Blood. 2001;97:3197–3204. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.10.3197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bross PF, et al. Approval summary: gemtuzumab ozogamicin in relapsed acute myeloid leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:1490–1496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pagano L, et al. The role of Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin in the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia patients. Oncogene. 2007;26:3679–3690. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walter RB, et al. Simultaneously targeting CD45 significantly increases cytotoxicity of the anti-CD33 immunoconjugate, gemtuzumab ozogamicin, against acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells and improves survival of mice bearing human AML xenografts. Blood. 2008;111:4813–4816. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-133785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.La Russa VF, et al. Effects of anti-CD33 blocked ricin immunotoxin on the capacity of CD34+ human marrow cells to establish in vitro hematopoiesis in long-term marrow cultures. Exp Hematol. 1992;20:442–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scott CJ, et al. Immunocolloidal targeting of the endocytotic siglec-7 receptor using peripheral attachment of siglec-7 antibodies to poly(lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles. Pharm Res. 2008;25:135–146. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9400-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Biagi E, et al. Chimeric T-cell receptors: new challenges for targeted immunotherapy in hematologic malignancies. Haematologica. 2007;92:381–388. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davis TA, et al. Rituximab anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: safety and efficacy of re-treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3135–3143. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.17.3135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Feuring-Buske M, et al. IDEC-C2B8 (Rituximab) anti-CD20 antibody treatment in relapsed advanced-stage follicular lymphomas: results of a phase-II study of the German Low-Grade Lymphoma Study Group. Ann Hematol. 2000;79:493–500. doi: 10.1007/s002770000163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Foran JM, et al. A UK multicentre phase II study of rituximab (chimaeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody) in patients with follicular lymphoma, with PCR monitoring of molecular response. Br J Haematol. 2000;109:81–88. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.01965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McLaughlin P, et al. Rituximab chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy for relapsed indolent lymphoma: half of patients respond to a four-dose treatment program. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:2825–2833. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.8.2825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kreitman RJ, et al. Efficacy of the anti-CD22 recombinant immunotoxin BL22 in chemotherapy-resistant hairy-cell leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:241–247. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107263450402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Du X, et al. Differential cellular internalization of anti-CD19 and -CD22 immunotoxins results in different cytotoxic activity. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6300–6305. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.DiJoseph JF, et al. Antitumor efficacy of a combination of CMC-544 (inotuzumab ozogamicin), a CD22-targeted cytotoxic immunoconjugate of calicheamicin, and rituximab against non-Hodgkin’s B-cell lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:242–249. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.DiJoseph JF, et al. Antibody-targeted chemotherapy of B-cell lymphoma using calicheamicin conjugated to murine or humanized antibody against CD22. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2005;54:11–24. doi: 10.1007/s00262-004-0572-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dijoseph JF, et al. Therapeutic potential of CD22-specific antibody-targeted chemotherapy using inotuzumab ozogamicin (CMC-544) for the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2007;21:2240–2245. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Castillo J, et al. Newer monoclonal antibodies for hematological malignancies. Exp Hematol. 2008;36:755–768. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Leonard JP, et al. Durable complete responses from therapy with combined epratuzumab and rituximab: final results from an international multicenter, phase 2 study in recurrent, indolent, non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer. 2008;113:2714–2723. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mattes MJ, et al. Therapy of Advanced B-Lymphoma Xenografts with a Combination of 90Y-anti-CD22 IgG (Epratuzumab) and Unlabeled Anti-CD20 IgG (Veltuzumab) Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6154–6160. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Leonard JP, Link BK. Immunotherapy of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma with hLL2 (epratuzumab, an anti-CD22 monoclonal antibody) and Hu1D10 (apolizumab) Semin Oncol. 2002;29:81–86. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2002.30149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jacobi AM, et al. Differential effects of epratuzumab on peripheral blood B cells of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus versus normal controls. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:450–457. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.075762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Qu Z, et al. Bispecific anti-CD20/22 antibodies inhibit B-cell lymphoma proliferation by a unique mechanism of action. Blood. 2008;111:2211–2219. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-110072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Haas KM, et al. CD22 ligand binding regulates normal and malignant B lymphocyte survival in vivo. J Immunol. 2006;177:3063–3073. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.3063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Levesque MC, St Clair EW. B cell-directed therapies for autoimmune disease and correlates of disease response and relapse. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.11.030. quiz 22-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Silverman GJ, Boyle DL. Understanding the mechanistic basis in rheumatoid arthritis for clinical response to anti-CD20 therapy: the B-cell roadblock hypothesis. Immunol Rev. 2008;223:175–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Matthews R. Autoimmune diseases. The B cell slayer. Science. 2007;318:1232–1233. doi: 10.1126/science.318.5854.1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lopez-Diego RS, Weiner HL. Novel therapeutic strategies for multiple sclerosis--a multifaceted adversary. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:909–925. doi: 10.1038/nrd2358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bochner BS, et al. Glycan array screening reveals a candidate ligand for Siglec-8. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:4307–4312. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412378200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tateno H, et al. Mouse Siglec-F and human Siglec-8 are functionally convergent paralogs that are selectively expressed on eosinophils and recognize 6′-sulfo-sialyl Lewis X as a preferred glycan ligand. Glycobiology. 2005;15:1125–1135. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwi097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang M, et al. Defining the in vivo function of Siglec-F, a CD33-related Siglec expressed on mouse eosinophils. Blood. 2007;109:4280–4287. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-039255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nutku E, et al. Ligation of Siglec-8: a selective mechanism for induction of human eosinophil apoptosis. Blood. 2003;101:5014–5020. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zimmermann N, et al. Siglec-F antibody administration to mice selectively reduces blood and tissue eosinophils. Allergy. 2008;63:1156–1163. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01709.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Song DJ, et al. Anti-Siglec-F antibody inhibits oral egg allergen induced intestinal eosinophilic inflammation in a mouse model. Clin Immunol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.von Gunten S, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin preparations contain anti-Siglec-8 autoantibodies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:1005–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yokoi H, et al. Inhibition of FcepsilonRI-dependent mediator release and calcium flux from human mast cells by sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectin 8 engagement. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:499–505. e491. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hartnell A, et al. Characterization of human sialoadhesin, a sialic acid binding receptor expressed by resident and inflammatory macrophage populations. Blood. 2001;97:288–296. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.1.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.van der Kuyl AC, et al. Sialoadhesin (CD169) expression in CD14+ cells is upregulated early after HIV-1 infection and increases during disease progression. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e257. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kim S, et al. Carcinoma-produced factors activate myeloid cells through TLR2 to stimulate metastasis. Nature. 2009;457:102–106. doi: 10.1038/nature07623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Revilla C, et al. Targeting to porcine sialoadhesin receptor improves antigen presentation to T cells. Vet Res. 2008;40:14. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2008052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.von Gunten S, Simon HU. Natural anti-Siglec autoantibodies mediate potential immunoregulatory mechanisms: implications for the clinical use of intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIg) Autoimmun Rev. 2008;7:453–456. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2008.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.von Gunten S, et al. Siglec-9 transduces apoptotic and nonapoptotic death signals into neutrophils depending on the proinflammatory cytokine environment. Blood. 2005;106:1423–1431. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-4112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.von Gunten S, et al. Immunologic and functional evidence for anti-Siglec-9 autoantibodies in intravenous immunoglobulin preparations. Blood. 2006;108:4255–4259. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-021568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Razi N, Varki A. Masking and unmasking of the sialic acid-binding lectin activity of CD22 (Siglec-2) on B lymphocytes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:7469–7474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Crocker PR, Varki A. Siglecs, sialic acids and innate immunity. Trends in immunology. 2001;22:337–342. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)01930-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Abdu-Allah HH, et al. Design, synthesis, and structure-affinity relationships of novel series of sialosides as CD22-specific inhibitors. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2008;51:6665–6681. doi: 10.1021/jm8000696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Collins BE, et al. High-affinity ligand probes of CD22 overcome the threshold set by cis ligands to allow for binding, endocytosis, and killing of B cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:2994–3003. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.2994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kaltgrad E, et al. On-virus construction of polyvalent glycan ligands for cell-surface receptors. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:4578–4579. doi: 10.1021/ja077801n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kelm S, et al. The ligand-binding domain of CD22 is needed for inhibition of the B cell receptor signal, as demonstrated by a novel human CD22-specific inhibitor compound. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2002;195:1207–1213. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.O’Reilly MK, et al. Bifunctional CD22 ligands use multimeric immunoglobulins as protein scaffolds in assembly of immune complexes on B cells. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:7736–7745. doi: 10.1021/ja802008q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hattori Y, et al. Efficient gene transfer into macrophages and dendritic cells by in vivo gene delivery with mannosylated lipoplex via the intraperitoneal route. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 2006;318:828–834. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.105098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ikehara Y, Kojima N. Development of a novel oligomannose-coated liposome-based anticancer drug-delivery system for intraperitoneal cancer. Current opinion in molecular therapeutics. 2007;9:53–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Irache JM, et al. Mannose-targeted systems for the delivery of therapeutics. Expert opinion on drug delivery. 2008;5:703–724. doi: 10.1517/17425247.5.6.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kuramoto Y, et al. Use of mannosylated cationic liposomes/ immunostimulatory CpG DNA complex for effective inhibition of peritoneal dissemination in mice. The journal of gene medicine. 2008;10:392–399. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Arakawa Y, et al. Eye-concentrated distribution of dexamethasone carried by sugar-chain modified liposome in experimental autoimmune uveoretinitis mice. Biomedical research (Tokyo, Japan) 2007;28:331–334. doi: 10.2220/biomedres.28.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hashida N, et al. High-efficacy site-directed drug delivery system using sialyl-Lewis X conjugated liposome. Experimental eye research. 2008;86:138–149. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hirai M, et al. Accumulation of liposome with Sialyl Lewis X to inflammation and tumor region: application to in vivo bio-imaging. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2007;353:553–558. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.12.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tsuruta W, et al. Application of liposomes incorporating doxorubicin with sialyl Lewis X to prevent stenosis after rat carotid artery injury. Biomaterials. 2008;30:118–125. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Monteiro VG, et al. Increased association of Trypanosoma cruzi with sialoadhesin positive mice macrophages. Parasitol Res. 2005;97:380–385. doi: 10.1007/s00436-005-1460-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Blixt O, et al. Sialoside specificity of the siglec family assessed using novel multivalent probes: identification of potent inhibitors of myelin-associated glycoprotein. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:31007–31019. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304331200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Brinkman-Van der Linden EC, Varki A. New aspects of siglec binding specificities, including the significance of fucosylation and of the sialyl-Tn epitope. Sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin superfamily lectins. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8625–8632. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kimura N, et al. Human B-lymphocytes express alpha2-6-sialylated 6-sulfo-N-acetyllactosamine serving as a preferred ligand for CD22/Siglec-2. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:32200–32207. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702341200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Terstappen LW, et al. Quantitative comparison of myeloid antigens on five lineages of mature peripheral blood cells. J Leukoc Biol. 1990;48:138–148. doi: 10.1002/jlb.48.2.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yokoi H, et al. Alteration and acquisition of Siglecs during in vitro maturation of CD34+ progenitors into human mast cells. Allergy. 2006;61:769–776. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2006.01133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pedraza L, et al. Differential expression of MAG isoforms during development. J Neurosci Res. 1991;29:141–148. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490290202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Angata T, et al. Discovery of Siglec-14, a novel sialic acid receptor undergoing concerted evolution with Siglec-5 in primates. Faseb J. 2006;20:1964–1973. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-5800com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Brinkman-Van der Linden EC, et al. Human-specific expression of Siglec-6 in the placenta. Glycobiology. 2007;17:922–931. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwm065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Avril T, et al. Sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectin 7 mediates selective recognition of sialylated glycans expressed on Campylobacter jejuni lipooligosaccharides. Infect Immun. 2006;74:4133–4141. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02094-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Munday J, et al. Identification, characterization and leucocyte expression of Siglec-10, a novel human sialic acid-binding receptor. Biochem J. 2001;355:489–497. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3550489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Angata T, et al. Cloning and characterization of human Siglec-11. A recently evolved signaling that can interact with SHP-1 and SHP-2 and is expressed by tissue macrophages, including brain microglia. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:24466–24474. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202833200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Angata T, et al. Siglec-15: an immune system Siglec conserved throughout vertebrate evolution. Glycobiology. 2007;17:838–846. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwm049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]