Abstract

Frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) is the second most common cause of presenile dementia. The predominant neuropathology is FTLD with TAR DNA binding protein (TDP-43) inclusions (FTLD-TDP)1. FTLD-TDP is frequently familial resulting from progranulin (GRN) mutations. We assembled an international collaboration to identify susceptibility loci for FTLD-TDP, using genome-wide association (GWA). We found that FTLD-TDP associates with multiple SNPs mapping to a single linkage disequilibrium (LD) block on 7p21 that contains TMEM106B in a GWA study (GWAS) on 515 FTLD-TDP cases. Three SNPs retained genome-wide significance following Bonferroni correction; top SNP rs1990622 (P=1.08×10−11; odds ratio (OR) minor allele (C) 0.61, 95% CI 0.53-0.71). The association replicated in 89 FTLD-TDP cases (rs1990622; P=2×10−4). TMEM106B variants may confer risk by increasing TMEM106B expression. TMEM106B variants also contribute to genetic risk for FTLD-TDP in patients with GRN mutations. Our data implicate TMEM106B as a strong risk factor for FTLD-TDP suggesting an underlying pathogenic mechanism.

FTLD manifests clinically with progressive behavioral and/or language deficits with a prevalence of 3.5-15/100,000 in 45 to 64 year olds2-5. The clinical presentation of cases with FTLD pathology varies depending on the referral base6 and among these cases, ~50% are diagnosed as FTLD-TDP1. A family history of a similar neurodegenerative disease may be present in up to 50% of FTLD cases, supporting the existence of a genetic predisposition7. Autosomal dominant GRN mutations occur in ~20% of FTLD-TDP cases8-11. GRN mutations are loss-of-function mutations with most resulting in premature termination of the mutant transcript invoking nonsense-mediated RNA decay and with the ensuing haploinsufficiency causing disease11,12. However, a substantial number of familial FTLD-TDP cases are not explained by GRN mutations. Further, patients with the same GRN mutation show variable clinical phenotypes or ages of disease onset which likely reflect additional genetic and environmental factors13.

The GWA phase of the study included 515 cases of FTLD-TDP and 2509 disease-free population controls genotyped on the Illumina HH550 or 610-Quad BeadChips as described14 (Table 1). A large population control cohort was acceptable since the general population incidence of FTLD is low4,5,15. Cases were obtained under institutional review board approval by members of the International FTLD Collaboration consisting of investigators from 45 clinical centers and brain banks representing 11 countries (United States, Canada, United Kingdom, The Netherlands, Belgium, Spain, Germany, Australia, Finland, France, and Sweden). All cases met either pathological (n=499) or genetic (n=16) criteria for FTLD-TDP which was confirmed by detecting TDP-43 inclusions using immunohistochemistry (IHC)1,16. A genetic criterion for inclusion (i.e. presence of a known pathogenic GRN mutation) was used since GRN mutation cases are always diagnosed as FTLD-TDP 8,9,17,18. All cases were checked for relatedness using identity by state (IBS). The results confirmed that although some GRN-associated FTLD-TDP cases share the same mutation on chromosome 17 with similarity in the immediate vicinity of GRN, they are no more related in the remainder of the genome than individuals without GRN mutations. Detailed inclusion criteria are provided in Methods; cohort features are in Supplementary Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of samples and controls used for GWA and replication phases

| Phase | Case Numbers |

Case Study Source |

Control Numbers |

Control Study Source | Method of Testing |

λ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GWA | 515 | International FTLD Consortium |

2509 | 1297 CHOP European- Caucasian, 1212 WTCCC |

Illumina HH550 or 610-Quad BeadChips |

1.05 |

| Replication | 89 | International FTLD Consortium |

553 | Penn Autopsy, Penn ADC, Coriell Neurologically Normal panel, CHOP European-Caucasian |

TaqMan genotyping of 2 SNPs |

CHOP, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia; Penn ADC, University of Pennsylvania Alzheimer's Disease Center; WTCCC, Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium; λ, genomic control inflation factor.

Cochran-Armitage trend test statistics were calculated at all markers following quality control filtering. In addition to self-reported ancestry, all cases and controls were initially screened at ancestry informative markers (AIM) using the STRUCTURE software package19 to reduce the risk of population stratification from self-reported ancestry alone. Each case was subsequently matched to four controls by ‘genetic matching’ by smartPCA20 as previously described21. The genomic inflation factor (λ) for this study was 1.05 indicating that background stratification was minimal as demonstrated in the quantile-quantile (Q-Q) plots (Supplementary Fig. 1).

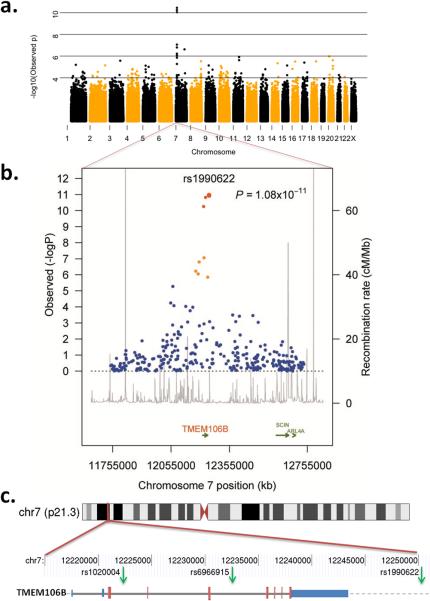

Three SNPs reached genome-wide significance following Bonferroni correction (Figures 1a and b). All three SNPs (rs6966915, rs1020004, and rs1990622) mapped to a 68 kb interval (Supplementary Fig. 2) on 7p21.3 (top marker, rs1990622, minor allele frequency (MAF) 32.1% in cases and 43.6% in controls, OR = 0.61, [95% CI 0.53 – 0.71], P=1.08×10−11). For rs1990622, the more common (T) allele confers risk with an OR of 1.64 [95% CI 1.34-2.00]. The interval contained nine additional markers in strong LD (r2 >0.45) that were also associated with FTLD-TDP (P-value range = 8.9×10−3 - 7.5×10−7; OR range 0.63-0.77) (Table 2). All 12 associated SNPs map to a single LD block spanning TMEM106B, which encodes an uncharacterized transmembrane protein of 274 amino acids (Figures 1b and c). SNPs rs1020004 and rs6966915 lie within introns 3 and 5, respectively, of TMEM106B, while rs1990622 is 6.9 kb downstream of the gene. These findings argue strongly for the association of the 7p21 locus, and the gene TMEM106B, with FTLD-TDP.

Figure 1. Region of genome-wide association at 7p21.

a. Manhattan plot of −log10(observed P-value) across genome demonstrating region of genome-wide significant association on chromosome 7; b. Regional plot of the TMEM106B associated interval. Foreground plot: Scatter plot of the −log10 P-values plotted against physical position (NCBI build 36). Background Plot: Estimated recombination rates (from phase 2 of the HapMap) plotted to reflect the local LD structure. The color of the dots represents the strength of LD between the top SNP rs1990622, and its proxies (red: r2 ≥ 0.8; orange 0.8 < r2 ≥ 0.4; blue < 0.4). Gene annotations were obtained from assembly 18 of the UCSC genome browser; c. Location of 3 highest associated SNPs (green arrows) relative to the gene structure of TMEM106B (blue bars, 3′ and 5′-untranslated regions; larger red bars, coding exons; thick gray line, intronic regions; gray dashed line, downstream chromosome sequence) and chromosome 7 location.

Table 2.

SNPs on chromosome 7 in region with highest association in the GWAS

| SNP rs ID | BP | Minor Allele |

MAF case |

MAF cont |

CA P-val | OR | Lower 95% CI |

Upper 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs1006869 | 12071795 | G | 0.148 | 0.184 | 5.82×10−3 | 0.77 | 0.64 | 0.92 |

| rs1990602 | 12088321 | G | 0.133 | 0.166 | 8.97×10−3 | 0.77 | 0.64 | 0.94 |

| rs10226395 | 12101859 | C | 0.154 | 0.191 | 4.90×10−3 | 0.77 | 0.64 | 0.93 |

| rs1003433 | 12130625 | G | 0.287 | 0.351 | 9.45×10−5 | 0.75 | 0.64 | 0.86 |

| rs6952272 | 12166585 | T | 0.154 | 0.207 | 9.88×10−5 | 0.70 | 0.58 | 0.84 |

| rs12671332 | 12182087 | C | 0.173 | 0.245 | 7.50×10−7 | 0.64 | 0.54 | 0.77 |

| rs1468915 | 12194417 | C | 0.171 | 0.242 | 9.49×10−7 | 0.65 | 0.54 | 0.77 |

| rs1020004 | 12222303 | G | 0.233 | 0.338 | 5.00×10−11 | 0.60 | 0.51 | 0.70 |

| rs6966915 | 12232513 | T | 0.321 | 0.435 | 1.63×10−11 | 0.61 | 0.53 | 0.71 |

| rs10488192 | 12243606 | T | 0.139 | 0.204 | 1.46×10−6 | 0.63 | 0.52 | 0.76 |

| rs1990622 | 12250312 | C | 0.321 | 0.436 | 1.08×10−11 | 0.61 | 0.53 | 0.71 |

| rs6945902 | 12252934 | A | 0.183 | 0.230 | 7.17×10−4 | 0.75 | 0.63 | 0.89 |

SNPs are listed in genomic order based on location on chromosome 7. SNPs in bold text have the lowest P-values.

Chr, chromosome; BP, base pairs (NCBI build 36); MAF, minor allele frequency; cont, controls; CA P-val, Cochrane-Armitage P-value; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

The association with FTLD-TDP in the GWA was replicated by TaqMan SNP genotyping in 89 independent FTLD-TDP cases and 553 Caucasian control samples at two of the genome-wide significant SNPs (rs1020004 and rs1990622) (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1). A polymorphic variation adjacent to rs6966915 interfered with interpretation of TaqMan genotyping therefore precluding its use in the replication. The replication set was selected based on the same pathological criteria and had similar characteristics as the GWA phase cohort (Supplementary Table 1). In this replication cohort, the top SNPs again showed significant association (P=0.004 for rs1020004 and P=0.0002 for rs1990622) with the same directions of association as those found in the GWA phase (Supplementary Table 1). These results suggest that in the 7p21 locus, encompassing the gene TMEM106B, we have identified a common genetic susceptibility factor for FTLD-TDP. Of interest, this association was not confirmed in a cohort of 192 living patients with unselected FTLD (Supplementary Table 2). This likely reflects heterogeneity in neuropathological substrates underlying FTLD, with only ~50% of unselected clinical FTLD cases expected to have FTLD-TDP. Assuming that TMEM106B genetic variants confer risk of FTLD-TDP specifically, the power to detect this association in 192 clinical FTLD cases and 553 controls is ~30% for an alpha-value of 0.05. To have >90% power to detect this association, a clinical FTLD cohort would require more than 1400 clinical FTLD cases and an equal number of controls.

We next evaluated TMEM106B gene expression in different human tissues to identify phenotype-associated differential expression and also any potential genetic regulators of expression. We queried the mRNA-by-SNP browser (http://www.sph.umich.edu/csg/liang/asthma/, last accessed June 6, 2009), for genetic regulators of TMEM106B expression (eSNPs) in lymphoblastoid cell lines22. The top SNP, rs1990622, was significantly correlated with TMEM106B average expression levels (LOD 6.32; P=6.9×10−8), as was SNP rs1020004 (LOD 5.16, P=1.10×10−6). The risk allele (T) of rs1990622 was associated with a higher level of mRNA expression, indicating that TMEM106B may be under cis-acting regulation by either the FTLD-TDP associated SNPs or another SNP(s) in LD with the associated variants. As the expression data in the publicly available database is derived from lymphoblastoid cell lines from normal individuals22, and the diseased organ in FTLD-TDP is brain, we asked if a similar correlation between genotype and expression phenotype for TMEM106B is also present in tissue types affected by disease, and in diseased individuals themselves. Accordingly, we used total RNA isolated from FTLD-TDP postmortem brains (n=18) and neurologically normal control brains (n=7) to evaluate TMEM106B expression in frontal cortex, which is severely affected in FTLD-TDP, by quantitative reverse-transcription PCR (QRT-PCR). All RNA samples used were confirmed to be of equivalent high quality as described23 (Supplementary Table 3). For the same individuals for which we obtained expression data, we genotyped SNPs rs1020004 and rs1990622 using allelic discrimination assays.

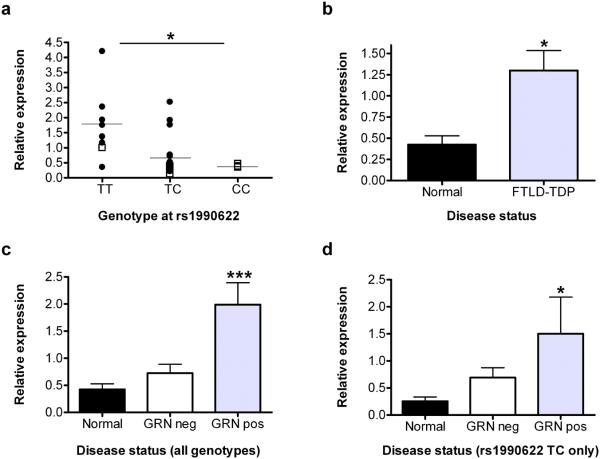

Corroborating results from the cell lines, expression of TMEM106B was significantly correlated with TMEM106B genotype, with risk allele carriers showing higher expression (overall P=0.027, TT vs. TC P=0.017, TT vs. CC P=0.03, for rs1990622, Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 3a). Strikingly, however, expression of TMEM106B was >2.5 times higher in FTLD-TDP cases compared to normal controls (P=0.045, Fig. 2b). In addition, the effects of genotype and TMEM106B expression on risk of developing disease are at least partly independent, as are the effects of genotype and disease status on TMEM106B expression (Supplementary Table 4a and b). Thus, these data suggest that increased TMEM106B brain expression might be linked to mechanisms of disease in FTLD-TDP, and that risk alleles at TMEM106B confer genetic susceptibility by increasing gene expression.

Figure 2. TMEM106B expression variation by genotype and disease state.

a. TMEM106B mRNA expression by QRT-PCR in frontal cortex differed significantly by genotype at rs1990622 (overall P=0.027, genotype TT vs. TC P=0.017, TT vs. CC P=0.03). Black circles, FTLD-TDP (n=18); open squares, normal (n=7); horizontal lines, group mean. Significance of P-values are denoted by the numbers of asterisks. b. TMEM106B mRNA expression in frontal cortex was significantly higher in samples from FTLD-TDP patients compared to normal controls (P=0.045). c. TMEM106B expression in frontal cortex samples in FTLD-TDP with (GRN pos, n=8) or without (GRN neg, n=10) GRN mutations compared to normals (n=7). GRN mutation carriers had significantly higher levels of TMEM106B expression (overall P =0.0009, GRN pos vs. controls P =0.0005, GRN pos vs. GRN neg P =0.002). d. When only cases heterozygous at rs1990622 (n=14) were evaluated, GRN mutations remained significantly associated with a higher level of TMEM106B expression (P =0.039) in frontal cortex. QRT-PCR was performed in triplicate for all expression studies. Expression values were normalized to the geometric mean of two housekeeping genes and are shown relative to a single reference normal control sample23. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Normalized gene expression data and sample genotype and gender data used for these analyses are provided online in Supplementary Material.

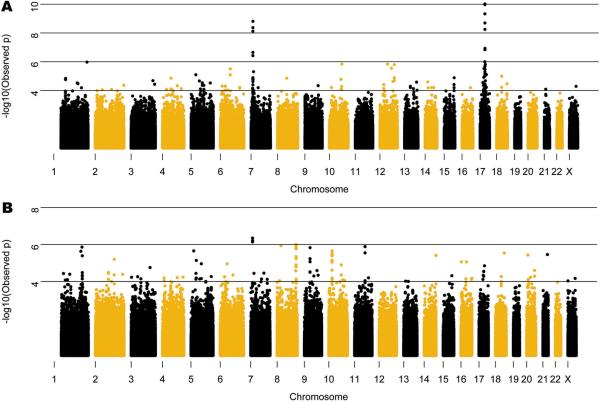

The primary criterion for inclusion in the GWAS was a neuropathological diagnosis of FTLD-TDP; therefore we studied all cases together regardless of GRN mutation status. Nevertheless, a priori it was difficult to predict whether additional genetic susceptibility loci would be identified in a group with Mendelian inheritance of highly penetrant mutations. We therefore separately evaluated FTLD-TDP cases with (n=89) and without (n=426) GRN mutations. Association to the 7p21 locus persisted in both the GRN negative and positive clusters and there was no significant heterogeneity in the ORs for the disease/SNP association between the clusters (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Tables 2 and 5). Using family history status as a covariate in a logistic regression showed that the 7p21 association is independent of family history (Supplementary Table 6). Thus, TMEM106B variants may act as a modifier locus in the presence of GRN mutations, as the APOE locus has been shown to modify age of onset in patients with PSEN124 or PSEN225 mutations.

Figure 3. Manhattan plot in cases with and without GRN mutations.

Manhattan plot of −log10(observed P-value) across genome in cases with (a) and without (b) GRN mutations. The subset of cases with GRN mutations demonstrates regions of genome-wide significant association on chromosomes 7 and 17. The chr 17 association is confirmed to be driven by a shared haplotype in c.1477C>T (p.R493X) GRN mutation carriers representing ~20% of mutation positive cases, however the chromosome 7 association is not related to any single GRN mutation and remains when the cases with c.1477C>T are removed (P=1.446×10−10). The same locus on chr 7 identified in the GRN mutation cases is also the strongest signal in the GRN negative cases, although it does not reach genome-wide significance. A list of the SNPs with the highest signals in b is given in Supplementary Table 8.

Additionally, in the whole GWA cohort, we observed a correlation between rs1020004 genotype and disease duration (P=0.03) with homozygotes for the risk allele (AA, wild-type) having shorter duration of disease (i.e. more severe disease) than individuals homozygous for the minor allele (GG, Supplementary Figure 4). These results provide strong confirmatory evidence for association of the 7p21 locus with increased risk for FTLD-TDP in both GRN positive and negative cases.

In addition to the 7p21 locus, analysis of the GRN cases alone showed highly significant association with SNPs near the GRN locus on 17q21 (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 7). Not unexpectedly, haplotype analysis of the cases indicated that the chromosome 17 association was driven by a shared haplotype among the p.R493X (NM_002087.2:c.1477C>T) mutation carriers which represented 20.2% (18/89) of the GRN mutation cases. To determine if the observed association at the GRN locus was dependent on the association at the TMEM106B locus we carried out a logistic regression analysis conditioning on the most significantly associated SNP at the 7p21 locus, rs1990622, in the patients with GRN mutations. The conditional analysis had no effect on the association at the GRN locus suggesting that the associations with 17q21 and 7p21 are independent. IBS analysis confirms that these individuals are unrelated and therefore the identified association on chromosome 7 cannot be discounted in GRN mutation carriers. Indeed, conditioning on the top SNP at the GRN locus, rs8079488, also had no effect on the TMEM106B association (results not shown). In addition to the 7p21 locus, the GWAS of GRN negative cases showed a trend for association at five other loci (Supplementary Table 8) including a locus on chromosome 9p21.2 that falls within a 7.7 Mb critical interval defined from five previous linkage studies, representing a potential refinement of that region26. We observed no association at the GRN locus in the cases without GRN mutations.

We then evaluated mRNA expression of TMEM106B in FTLD-TDP with and without GRN mutations separately, and the GRN mutants showed increased expression (overall P=0.0009), compared to controls (P=0.0005) and FTLD-TDP without GRN mutations (P=0.002) (Figure 2c). Furthermore, controlling for rs1990622 genotype and focusing on heterozygotes (n=14), the presence of a GRN mutation remained significantly associated with increased TMEM106B expression (P=0.039, Fig. 2d) compared to normal controls. These results are compatible with a model in which mutations in GRN are upstream of increased TMEM106B expression in increasing risk for FTLD-TDP.

A mechanistic understanding of the pathogenesis of FTLD has been hampered the heterogeneity in clinical and pathological features. With the discovery of TDP-43 as a major FTLD disease protein, the pathologically-defined entity of FTLD-TDP emerged16. Identification of GRN mutations as a major genetic cause of FTLD-TDP, led to definition of a genetic subgroup of FTLD-TDP. This study identifies TMEM106B as a genetic risk factor for FTLD-TDP. We speculate that the homogeneous pathologically-defined study population used here enabled us to detect a robust signal with relatively small case numbers.

Our data suggest a potential disease mechanism in which risk-associated polymorphisms at 7p21 increase TMEM106B expression, and elevated TMEM106B expression increases risk for FTLD-TDP. Additionally, we show that TMEM106B genotypes are a significant risk factor for FTLD-TDP even in GRN mutation carriers implying that GRN mutations may act upstream of TMEM106B in a pathogenic cascade. Future directions of research on this novel genetic risk factor will include a detailed evaluation of the TMEM106B locus by sequencing, collection of more pathologically-defined FTLD-TDP cases for a genome-wide replication, and studies of expression profiles in additional tissues and brain regions. A better understanding of this gene may in turn provide an opportunity to intervene in an otherwise fatal and devastating neurodegenerative disease.

METHODS

Inclusion criteria

Individuals of European descent with dementia clinically +/− motor neuron disease (MND) and an autopsy diagnosis of FTLD-TDP confirmed by TDP-43 IHC were included. Mixed pathologies were not excluded. Living individuals with a pathogenic GRN mutation were also included18. Only a single proband per family was permitted. Appropriate informed consent was obtained. 598 unique FTLD-TDP cases met inclusion criteria; 515 were used for the GWAS after PCA matching to controls. Characteristics described in Supplementary Table 1. Whole genome amplification (WGA), performed in duplicate and pooled, was used for 15 (Repli-g Mini, Qiagen), but only 6 cases ultimately passed quality control parameters for the GWAS. The replication, using SNP genotyping, included cases of insufficient quality or quantity for the GWA phase (n=27), cases available only as formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue (n=6), and cases randomly not used for GWA phase (n=56). Three FTLD-TDP cases with mutations in valosin-containing protein (VCP) gene were included (two in GWA and one in replication)18.

Controls

GWAS controls consisted of 2509 samples, including 1297 self-reported Caucasian children of European ancestry recruited from CHOP Health Care Network and 1212 samples from the 1958 birth cohort genotyped by the WTCCC27. Although the controls were not selected for absence of neurodegenerative disease, the large size of the cohort relative to the low population frequency of FTLD overrides this potential concern. Furthermore, the minor allele frequencies at the 7p21 loci are very similar (<1-2% variation) between CHOP and WTCCC cohorts suggesting they accurately reflect the control allelic frequencies in the general population (Supplementary Table 9). To reduce the risk of population stratification all internal controls were screened using the STRUCTURE package19 at 220 AIMs. To improve clustering the samples were spiked with 90 CEPH, Yoruban and Chinese/Japanese individuals genotyped as part of the HapMap project. Cases were excluded if their inferred proportion of ancestry was less than 90% that of the CEU cluster.

For the replication 553 controls were as follows: 275 from Coriell Institute (Neurologically Normal Caucasian control panels, Camden, NJ), 155 clinical controls from neurology clinics at University of Pennsylvania (UPenn), 28 brain samples of neurologically normal individuals > 60 years from the UPenn Center for Neurodegenerative Disease Research (CNDR), and 95 population controls from CHOP.

DNA extraction and quality assessment

Samples sent as DNA from external sites were extracted using different methods. Remaining samples (376) were extracted at UPenn from frozen brain tissue or blood. Genomic DNA was extracted from frozen brain tissue (50 mg) by the Qiagen MagAttract DNA Mini M48 Kit on the M48 BioRobot. Genomic DNA was purified from whole blood using FlexiGene kit (Qiagen). High quality DNA was required for the Illumina genotyping. All DNA samples were evaluated for purity by spectrophotometric analysis (Nanodrop) and for degradation by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis (Invitrogen).

TDP-43 IHC

Autopsy cases were confirmed to have TDP-43 pathology by IHC performed by the sending institution or at UPenn CNDR as previously described16. TDP-43 negative cases were excluded.

GRN sequencing

To stratify the analysis according to GRN mutation status, exons 1-13 (with exon 1 representing exon 0 in Gass et al.10) and adjacent intronic regions were sequenced as described13 in cases not previously evaluated. GRN sequencing was not possible due to limited sample quantity in a few cases (n=13 in GWA, n=15 in replication). Novel variants identified in this study not predicted to cause a frameshift or premature termination and previously described variants of uncertain significance were grouped with GRN mutation negative cases. The most common mutations identified are given in Supplementary Table 1.

Illumina genotyping and quality control

The FTLD-TDP cases and CHOP control samples were genotyped on either the Illumina HH550 BeadChip or the Illumina human610-quad BeadChip at the Center for Applied Genomics at CHOP as previously described14. The 1958 birth cohort samples were genotyped on the HH550 BeadChip by the WTCCC27. Sixteen individuals, 13 cases and 3 controls, were excluded from GWA phase for low genotyping (<98% chip-wide genotyping success). We further rejected 13,316 SNPs with call rates <95%, 23,552 SNPs with MAF < 1% and 1,940 SNPs with Hardy Weinberg equilibrium P<10−5 in the controls samples; the λ was 1.05. Cases and controls were screened for relatedness using the IBS estimations in plink (http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/~purcell/plink/index.shtml) on 100,000 randomly distributed markers throughout the genome. Pairwise Pi-hat values in excess of 0.01 were indicative of relatedness.

Following the quality control measures cases were matched to controls by ‘genetic matching’ as previously described21. We computed principal components for our dataset by running smartpca, a part of the EIGENSTRAT package, on 100,000 random autosomal SNPs and applied a matching algorithm implemented in MATLAB to the output. The matching algorithm assigns each sample a coordinate based on k eigenvalue-scaled principal components. It then matches each case to m unique controls within a distance d, keeping only cases that match exactly m controls. The distance thresholds were manually optimized to minimize λ and maximize power (i.e. number of cases). We matched each case to four controls, using the first three principal components and a distance threshold of 0.025.

Statistical Analysis for Association

Statistical tests for association were performed using plink. Single marker analyses for the genome-wide data were done using the Cochran-Armitage trend test. The genomic inflation factors were 1.05 for the complete case set and 1.03 for the GRN mutation carriers, indicating only minor background stratification. The Breslow-Day test within plink was used to test for heterogeneity of odds ratio for the disease/SNP association between GRN mutation carriers and non-carriers. Conditional SNP regression analyses were completed in plink, the allele dosages of the conditioning SNP were included as covariates in the logistic regression models. To determine if the association at the TMEM106B locus was dependent on family history we included family history status as a covariate in a logistic regression model using plink. Haplotypes were reconstructed and population frequencies estimated using the EM algorithm implemented in the program fastPHASE28. For the age of onset and disease duration analyses we performed an analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the general linear models procedure in R (www.r-project.org). Independent variables for each ANOVA were the log transformed age of onset or disease duration in years and the individual SNP genotype with additive encoding (ie three categories where 0 is homozygous for the ancestral allele, 1 is heterozygous and 2 is homozygous for the minor allele). Power calculations were based on the rs1990622 allele frequencies observed for cases and controls in the GWAS, using a two-tailed test. We assumed that clinical FTLD cases without TDP-43 pathology as the neuropathological substrate would have allele frequencies similar to controls.

SNP Genotyping for Replication

For the replication, genotyping was performed using TaqMan chemistry-based allelic discrimination assays (Applied Biosystems (ABI), Foster City, CA) on the ABI 7500 Fast Real-Time System followed by analysis with SDS 7500 software v2.0.1. The ABI assays used were: rs1020004, C_7604953_10 and rs1990622, C_11171598_10. A nearby novel genetic variation (possible deletion) was found to interfere with correct genotyping of the T allele of SNP rs6966915 using ABI reagents C_31573289_10 (as well as by DNA sequencing), thus this SNP was not used further.

Human samples for expression analysis

Frontal cortex human brain samples from the CNDR Brain Bank characterized following consensus criteria1,3 were dissected as previously described23. Neurologically normal controls (n=7), FTLD-TDP cases with (n=8), and without (n=10) GRN mutations were sampled (Supplementary Table 10). GRN mutations were confirmed to be absent from control cases. RNA quality was verified using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (RIN>6 for inclusion) as previously described23. mRNA expression was quantified by QRT-PCR on the ABI7500 using the delta-delta CT method, and the geometric mean of two housekeeping genes (β-actin and Cyclophilin A), shown to have stable expression in frontal cortex samples from FTLD-TDP and normal individuals23. Detailed information on primers is available on request.

Statistical analyses of expression data and replication cohort

For all brain expression and replication cohort analyses, statistical tests were performed using open source R software packages. R-scripts are available upon request. For evaluations of the effect of disease status, SNP genotype, and gender on TMEM106B expression, linear regressions were used to compute p-values in univariate models. We evaluated assumptions of linearity by checking QQ plots (observed vs. predicted under normal distribution). For pairwise comparisons within the linear models, risk allele homozygotes and GRN mutants, respectively, were designated the reference group for marginal t-tests evaluating genotype effects and the effects of GRN mutations on expression. Normalized gene expression sample genotype and gender data are provided in Supplementary Data 1 and 2. For evaluations of the independent contributory effects of SNP genotype and TMEM106B expression on disease state, logistic regressions were used to compute AIC values in multivariate vs. univariate models (Supplementary Table 4a). For evaluations of the independent contributory effects of SNP genotype and disease state on TMEM106B expression, linear regressions were used in multivariate vs. univariate models (Supplementary Table 4b). For analyses of association of SNP genotypes with disease in our TaqMan replication cohort, Cochran-Armitage trend tests were used to compute P-values under a codominant model.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This project was enabled by the contributions and efforts of many individuals in several supportive capacities. Most importantly, we extend our appreciation to the patients and families who made this research possible. Extensive technical assistance was provided by R. Greene, T. Unger, and C. Kim and study coordination by E. McCarty Wood. The following individuals contributed through sample ascertainment, epidemiology, coordination, and/or clinical evaluation of cases: R.C. Petersen, D.S. Knopman, K.A. Josephs, D. Neary, J. Snowden, J. Heidebrink, N. Barbas, R. Reñe, J.R. Burke, K. Hayden, J. Browndyke, P. Gaskell, M. Szymanski, J.D. Glass, M. Rossor, F. Moreno, B. Indakoetxea, M. Barandiaran, S. Engelborghs, P.P. De Deyn, W.S Brooks, T. Chow, V. Meininger, L. Lacomblez, E. Gruenblatt. The following individuals contributed through pathological characterization and evaluation of cases: L. Kwong, J.E. Parisi, W. Kamphorst, I. Ruiz, T. Revesz, J.-J.Martin, R. Highley, C. Duyckaerts. The following individuals contributed through general technical assistance and/or genetic studies: E. Moore, M. Baker, R. Crook, S. Rollinson, N. Halliwell, S. Usher, R.M. Richardson, M. Mishra, C. Foong, J. Ervin, K. Price Bryan, J. Ervin, C. Kubilus, A. Gorostidi, M. Cruts, I. Gijselinck, H. McCann, P.R. Schofield, G. Forster, K. Firch, J. Pomaician, I. Leber, V. Sazdovitch, I. Volkmann. The following individuals also contributed: D. Clark, S. Weintraub, N. Johnson, A. King, I. Bodi, C. Shaw, J. Kirby, V. Haroutunian, D. Purohit. We also thank the Brain Bank of University of Barcelona/Hospital Clinic, Clinic for Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders University of British Columbia, Australian Brain Donor Programs supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, Biobank at the Institute Born-Bunge, and the French clinical and genetic research network on FTD/FTD-MND. Many grant funding agencies provided financial support for this study, including the National Institutes of Health (AG10124, AG17586, AG16574, AG03949, AG17586, NS44266, AG15116, NS53488, AG10124, AG 010133, AG08671, NS044233, NS15655, AG008017, AG13854, P3AG12300, AG028377, AG 019724, AG13846, AG025688, AG05133, AG08702, AG05146, AG005136, AG005681, AG03991, AG010129, AG05134, NS038372, AG02219, AG05138, AG10161, AG19610, AG19610, AG16570, AG 16570, AG05142, AG005131, AG5131, AG18440, AG16582, AG 16573, and NIH Intramural Program). Additional funds were provided by: Robert and Clarice Smith and Abigail Van Buren Alzheimer's Disease Research Program, the Pacific Alzheimer's disease Research Foundation (PARF) grant #C06-01, the Alzheimer's Research Trust, Alzheimer's Society, Medical Research Council (Programme Grant and Returning Scientist Award), Stichting Dioraphte(07010500), Hersenstichting (15F07.2.34), Prinses Beatrix Fonds (006-0204), Winspear Family Center for Research on the Neuropathology of Alzheimer Disease, the McCune Foundation, Instituto Carlos III, Federal Ministry of Education and Research (01GI0505), SAIOTEK Program (Basque Government), Department of Innovation, Diputación Foral de Gipúzkoa (DFG 0876/08), ILUNDAIN Fundazioa, CIBERNED, Wellcome Trust, Canadian Institutes of Health Research (75480), Fund for Scientific Research Flanders (FWO-V), IAP P6/43 network of the Belgian Science Policy Office (BELSPO), the Joseph Iseman Fund, the Louis and Rachel Rudin Foundation, National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, Veteran's Affairs Research Funds, Arizona Department of Health Services (contract 211002, Arizona Alzheimer's Research Center), the Arizona Biomedical Research Commission (contracts 4001, 0011 and 05-901 to the Arizona Parkinson's Disease Consortium), the Prescott Family Initiative of the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson's Research, the Daljits and Elaine Sarkara Chair in Diagnostic Medicine, BrainNet Europe II, and MMCYT Ref SAF 2001-4888.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information is available online

Competing Financial Interest

A patent application on TMEM106B has been submitted. Dr. James Lah is currently involved in clinical trials involving: Elan, Janssen, Medivation, and Ceregene. Dr. Howard Feldman has been a full time employee in Neuroscience Global Clinical Research and Development at Briston-Myers Squibb.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cairns NJ, et al. Neuropathologic diagnostic and nosologic criteria for frontotemporal lobar degeneration: consensus of the Consortium for Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:5–22. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0237-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neary D, et al. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 1998;51:1546–54. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.6.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKhann GM, et al. Clinical and pathological diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia: report of the Work Group on Frontotemporal Dementia and Pick's Disease. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:1803–9. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.11.1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mercy L, Hodges JR, Dawson K, Barker RA, Brayne C. Incidence of early-onset dementias in Cambridgeshire, United Kingdom. Neurology. 2008;71:1496–9. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000334277.16896.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ratnavalli E, Brayne C, Dawson K, Hodges JR. The prevalence of frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2002;58:1615–21. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.11.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forman MS, et al. Frontotemporal dementia: clinicopathological correlations. Ann Neurol. 2006;59:952–62. doi: 10.1002/ana.20873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldman JS, et al. Frontotemporal Dementia: Genetics and Genetic Counseling Dilemmas. Neurologist. 2004;10:227–234. doi: 10.1097/01.nrl.0000138735.48533.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker M, et al. Mutations in progranulin cause tau-negative frontotemporal dementia linked to chromosome 17. Nature. 2006;442:916–9. doi: 10.1038/nature05016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cruts M, et al. Null mutations in progranulin cause ubiquitin-positive frontotemporal dementia linked to chromosome 17q21. Nature. 2006;442:920–4. doi: 10.1038/nature05017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gass J, et al. Mutations in progranulin are a major cause of ubiquitin-positive frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:2988–3001. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gijselinck I, Van Broeckhoven C, Cruts M. Granulin mutations associated with frontotemporal lobar degeneration and related disorders: an update. Hum Mutat. 2008;29:1373–86. doi: 10.1002/humu.20785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cruts M, Van Broeckhoven C. Loss of progranulin function in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Trends Genet. 2008;24:186–94. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Deerlin VM, et al. Clinical, genetic, and pathologic characteristics of patients with frontotemporal dementia and progranulin mutations. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:1148–53. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.8.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hakonarson H, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies KIAA0350 as a type 1 diabetes gene. Nature. 2007;448:591–4. doi: 10.1038/nature06010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCarthy MI, et al. Genome-wide association studies for complex traits: consensus, uncertainty and challenges. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:356–69. doi: 10.1038/nrg2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neumann M, et al. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2006;314:130–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1134108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cairns NJ, et al. TDP-43 in familial and sporadic frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin inclusions. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:227–40. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mackenzie IR, et al. Nomenclature for neuropathologic subtypes of frontotemporal lobar degeneration: consensus recommendations. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;117:15–8. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0460-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Falush D, Stephens M, Pritchard JK. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: linked loci and correlated allele frequencies. Genetics. 2003;164:1567–87. doi: 10.1093/genetics/164.4.1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patterson N, Price AL, Reich D. Population structure and eigenanalysis. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e190. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luca D, et al. On the use of general control samples for genome-wide association studies: genetic matching highlights causal variants. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:453–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dixon AL, et al. A genome-wide association study of global gene expression. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1202–7. doi: 10.1038/ng2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen-Plotkin AS, et al. Variations in the progranulin gene affect global gene expression in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:1349–62. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pastor P, et al. Apolipoprotein Eepsilon4 modifies Alzheimer's disease onset in an E280A PS1 kindred. Ann Neurol. 2003;54:163–9. doi: 10.1002/ana.10636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wijsman EM, et al. APOE and other loci affect age-at-onset in Alzheimer's disease families with PS2 mutation. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2005;132B:14–20. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Le Ber I, et al. Chromosome 9p-linked families with frontotemporal dementia associated with motor neuron disease. Neurology. 2009;72:1669–76. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a55f1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature. 2007;447:661–78. doi: 10.1038/nature05911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scheet P, Stephens M. A fast and flexible statistical model for large-scale population genotype data: applications to inferring missing genotypes and haplotypic phase. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78:629–44. doi: 10.1086/502802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.