Abstract

The liver is the first organ infected by Plasmodium sporozoites during malaria infection. In the infected hepatocytes, sporozoites undergo a complex developmental program to eventually generate hepatic merozoites that are released into the bloodstream in membrane-bound vesicles termed merosomes. Parasites blocked at an early developmental stage inside hepatocytes elicit a protective host immune response, making them attractive targets in the effort to develop a pre-erythrocytic stage vaccine. Here, we generated parasites blocked at a late developmental stage inside hepatocytes by conditionally disrupting the Plasmodium berghei cGMP-dependent protein kinase in sporozoites. Mutant sporozoites are able to invade hepatocytes and undergo intracellular development. However, they remain blocked as late liver stages that do not release merosomes into the medium. These late arrested liver stages induce protection in immunized animals. This suggests that, similar to the well studied early liver stages, late stage liver stages too can confer protection from sporozoite challenge.

Keywords: Genetics, Immunology, Organisms/Parasite, Organisms/Protozoan, Gene Knockout, Plasmodium, Development, Kinase, Liver Stage

Introduction

Malaria is among the deadliest infectious diseases in the world. It is caused by protozoan parasites of the genus Plasmodium that undergo a complex life cycle in the mammalian host and the mosquito vector. A human malaria infection begins when a Plasmodium sporozoite delivered through the bite of an infected mosquito infects a hepatocyte in the host liver. Within an intrahepatic membrane-bound vacuole the sporozoite undergoes extensive physical transformation followed by nuclear divisions, cytoplasmic segmentation, and eventually the formation of thousands of merozoites (1). Merozoites exit the infected hepatocyte by budding off in membrane-bound vesicles termed merosomes (2). Merosomes extrude from the infected hepatocyte through the endothelial cell layer and are released into the neighboring sinusoids. Thus, hepatic merozoites are delivered directly into the blood stream where they initiate invasion of erythrocytes and the symptomatic phase of a malaria infection (2). Unlike other stages of the Plasmodium life cycle, the stages that develop inside the hepatocytes, called “liver stages” (LSs),3 are relatively poorly understood. Although the execution of the LS developmental program must require a large repertoire of molecules, only a few have been functionally identified so far (3–10).

LS are of significant clinical and biological interest. Inhibiting the growth of LS could prevent the pathology associated with the erythrocytic stages of a malaria infection. The morbidity associated with Plasmodium vivax, the major human species in South America and South Asia, partly results from its ability to form dormant liver stages, termed hypnozoites, against which there are few effective treatment options (11). Reactivated hypnozoites can cause disease relapse up to a year after initial infection. Finally, LS have long been recognized to be ideal targets for developing a pre-erythrocytic stage malaria vaccine. Animals immunized with irradiated or genetically attenuated sporozoites, which develop only into early LS, display long term protection from a future sporozoite challenge (12). Thus, a better understanding of LS development would inform both drug discovery and vaccine development efforts.

Little is known of signaling pathways that operate during LS development. Parasite kinases are likely to play an important role during this process. Plasmodium cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG) is likely to be a key mediator of cGMP signaling in the parasite (13). It is a serine-threonine kinase that transfers the γ-phosphate of ATP in a cGMP-dependent manner to a variety of substrate proteins. Previously, it was shown to be essential for parasite gametogenesis in the mosquito (14). Homologs are present in the rodent and human Plasmodium species and in other Apicomplexan parasites, Toxoplasma and Eimeria (15). Key biochemical differences between mammalian and Plasmodium PKG can be exploited for the development of specific inhibitors (15), indicating the potential utility of the protein as a drug target.

In the current study, we investigate the role of PbPKG in Plasmodium LS development. We demonstrate that Plasmodium berghei PKG (PbPKG) is expressed during the parasite's LS development and is required at a late step of LS development. Using a newly described conditional mutagenesis system (16), we generated parasites in which the PbPKG locus is intact during erythrocytic development but is disrupted in sporozoites. The conditional knock-out (cKO) sporozoites are capable of infecting HepG2 cells in tissue culture and mouse livers in vivo. In HepG2 cells they form equal numbers of LS at 40 h post-infection. However, at 65 h post-infection, at a time when hepatic merozoites are normally released into the medium as merosomes, the PbPKG cKO parasites do not generate extracellular merosomes. Importantly, we show that these PbPKG cKO parasites, which are arrested late during LS development, elicit a protective immune response.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Parasite Transfection

The cKO targeting vector was constructed by cloning three PCR products into a vector that carries the two Flp recognition target sequences (FRT) sites and the human dihydrofolate reductase expression cassette (16). Primer sequences 5′-GCGGCCGCCACCAAGAGAGTAAACAC and 5′-GCGGCCGCCGAGCCCCAAAACATTAT were used to amplify a 2.0-kb fragment encompassing the 5′-untranslated reginon region and exons 1–3 of PbPKG. The product was cloned into the vector using NotI (underlined). Primer sequences 5′-CTCGAGAAAAAGGCACACATGTTTGC and 5′-CTCGAGAAGTAAAGAATAGCGAAAT were used to amplify a 3.0-kb fragment encompassing exons 4–5 and the 3′-untranslated reginon region of PbPKG. It was inserted into the previously generated plasmid using XhoI (underlined). Primer sequences 5′-GGTACCACAAATATTGTTTTTTCTTTTA and 5′-GAATTCGATATGTATGTCGGGGATTA were used to amplify a 0.5-kb fragment that was inserted into the previously derived plasmid using KpnI (underlined) and EcoRI (underlined). The final insert was released from the targeting construct using EcoRI. Transfections of the targeting plasmid into TRAP/FlpL(−) parasites were carried out using standard methodology (17). Transfected parasites were selected using pyrimethamine and cloned by limiting dilution.

Mosquito Cycles

Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes were fed on infected Swiss Webster mice. Mosquitoes were maintained at 20 °C until day 14 post-bloodmeal and then transferred to 25 °C. Sporozoites were dissected from their salivary glands at days 18–21 post-feeding. Infectivity of salivary glands was similar for cKO and control parasites at ∼8,000–10,000 sporozoites/mosquito.

Southern Hybridization and Diagnostic PCR

Parasite genomic DNA was digested with BamHI and SpeI before transfer to a nylon membrane. The membrane was probed with dioxygenin-labeled exon 5 (DIG High Prime DNA labeling and detection kit, Roche Applied Sciences). DNA hybridization was visualized using a chemiluminescent substrate following the manufacturer's instructions. PCR was performed using genomic DNA extracted from either erythrocytic stage parasites or sporozoites (QIAamp Blood and Tissue DNA kit, Qiagen). Sequences of PCR oligos 1 and 2 are as follows: 5′-GGAGGTATTTCAAAATTGTA and 5′-CCATATGATACTTCGTTTG. PCR was performed using the Expand High Fidelity PCR system (Roche Applied Sciences) with 1 cycle at 95 °C for 5 min followed by 35 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 48 °C for 30 s, and 68 °C for 10 min.

Reverse Transcriptase (RT)-PCR

RNA was extracted from HepG2 cells infected with P. berghei sporozoites using the Qiagen RNeasy kit, Qiagen. RNA was reverse-transcribed in the presence or absence of RT using the RETROscript kit, Ambion. The RT reaction was used as template in PCR reactions to amplify PbPKG and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase messages. PCR primers used to amplify PbPKG were 5′-CCATTTAGAATTGAGGGATAA and 5′-CACTATTTATAATGAAAAAGT. PCR primers used to amplify glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase were 5′-ATGGCAATAACAAAAGTCGG and 5′-CCCCATGGAATTTGAGCT.

Infection of HepG2 Cells and Merosome Assay

Sporozoites were obtained at days 18–21, post-bloodmeal, from infected mosquitoes maintained as described above. They were added to HepG2 cells grown on collagen-coated coverslips. Cells were incubated for 40 or 65 h before fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min followed by permeabilization with cold methanol for 10 min. Cells were stained with an anti-LS monoclonal antibody that recognizes parasite heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) (18). The anti-Hsp70 antibody was diluted to 10 μg/ml in phosphate-buffered saline containing 1% bovine serum albumin and incubated with cells for 1 h at 37 °C. After washes with phosphate-buffered saline, the cells with treated with an anti-mouse fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated secondary antibody. Merosomes were obtained from infected cultures by collecting the medium 65 h post-infection. Merosomes were pelleted by a brief centrifugation, resuspended in a small volume of phosphate-buffered saline, and added to a coverslip. After paraformaldehyde fixation and methanol permeabilization, merosomes were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole and examined using a fluorescent microscope.

Mouse Infections and Immunization Studies

Sporozoites were obtained at days 18–21, post-bloodmeal, from infected mosquitoes maintained as described above. They were injected intravenously into C57Bl/6 mice (6–8 weeks, females). To determine the pre-patent period of infection, injected mice were monitored daily through microscopic examination of Giemsa-stained thick blood smears. The first day post-infection, on which blood-stage parasites were detected, was determined to be the pre-patent period for that animal. For immunization studies, immunized and age-matched control animals were challenged with P. berghei NK65 sporozoites. The pre-patent period of infection in each animal was determined as described above.

Detection of Infectivity in Vivo Using Real Time PCR

The in vivo infectivity of CON and cKO sporozoites in the liver was determined as follows. Mice were infected by intravenous injection of 10,000 sporozoites of each parasite into groups of five C57Bl/6 animals. The parasite load within each mouse liver was determined 40 h post-infection by real time PCR (19). The standard curve was obtained using serial dilutions of a plasmid carrying the P. berghei 18 S rRNA gene. The parasite load of each sample was expressed as the plasmid DNA equivalent The primers used for amplification of P. berghei 18S rRNA were 5′-AAGCATTAAATAAAGCGAATACATCCTTC and 5′- GGAGATTGGTTTTGACGTTTATGT.

RESULTS

PbPKG Is Expressed during Liver Stage Development

PKG (PfPKG) is expressed during erythrocytic stages, primarily in rings, and in gametocytes (20, 21). Here, we investigated PbPKG expression in liver stages. PbPKG transcripts were clearly detected in early and late LSs developing in tissue-culture cells (Fig. 1). These results are consistent with microarray studies that found Plasmodium yoelii PKG expression during LS development in vivo (22). The temporal expression pattern of PbPKG, thus, suggested a possible role for PbPKG in liver stages. We examined its functional role in LS biology by producing loss-of-function mutants. However, as was reported earlier for PfPKG (14), PbPKG proved to be refractory to gene disruption, suggesting that it is essential for the erythrocytic cycle of the parasite. Therefore, we utilized a conditional mutagenesis approach for disrupting the PbPKG gene in the pre-erythrocytic stages of the parasite.

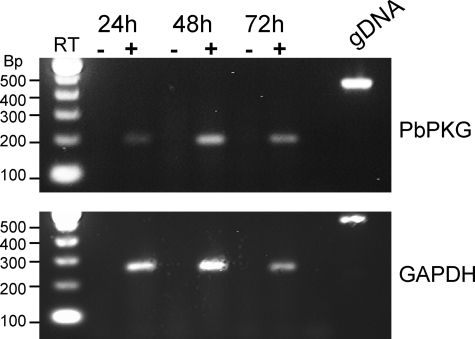

FIGURE 1.

RT-PCR detection of PbPKG expression in infected HepG2 cells. mRNAs of PbPKG (top panel) and mammalian glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were detected in HepG2 cells infected with P. berghei sporozoites 24, 48, and 72 h post-infection. Reverse transcription reactions were carried in the presence (+) or absence (−) of RT. P. berghei genomic DNA (gDNA) was used as a positive control.

Conditional Mutagenesis of PbPKG Using the TRAP/FlpL System

We utilized a recently developed P. berghei conditional mutagenesis approach that uses stage-specific expression of a temperature-sensitive variant of the yeast recombinase, flippase (FlpL), to catalyze the excision of DNA placed between two FRT (16). FlpL catalyzes site-specific DNA recombination at a temperature range of 25–30 °C.

The PbPKG open reading frame consists of five exons, with exons 4 and 5 encoding four cGMP binding sites and a kinase domain (Fig. 2A). We modified the locus by inserting two FRT sites carried on a double crossover targeting plasmid called pKO. Homologous integration of the pKO plasmid would place one FRT site in the intron separating exon 3 and exon 4 and a second FRT site downstream of the 3′ expression sequence of the gene. The plasmid was transfected into parasites that express FlpL under the control of the sporozoite-specific promoter of the Thrombospondin-related anonymous protein gene (TRAP/FlpL), causing the excision of the FRT-flanked sequence specifically in sporozoites (Fig. 2A). Recombinant parasites were readily selected (Fig. 2C), showing that the 5′-FRT site located between exons 3 and 4 does not impair normal expression of PKG. A recombinant clone named “cKO” was isolated by limiting dilution for further analysis. A control clone named “CON” was selected after transfection of a derivative plasmid called pCON, which lacks the 5′-FRT site, into the same TRAP/FlpL parasite clone (Fig. 2B).

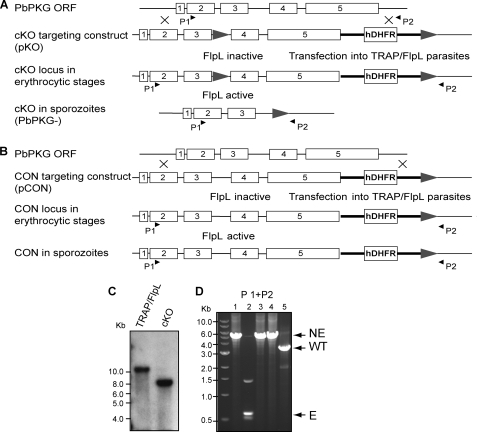

FIGURE 2.

Conditional mutagenesis of PbPKG. The PbPKG open reading frame (ORF) consists of 5 exons (open rectangles). A, the targeting plasmid for generating the conditional knock-out (pKO) parasites contains two FRT sites (gray arrowheads) flanking exons 4–5 and an expression cassette for human dihydrofolate reductase (hDHFR). Activation of the FlpL activity in sporozoites leads to the loss of exons 4–5 in cKO parasites. Black arrowheads indicate the position of primers used in diagnostic PCRs. B, the targeting plasmid for generating the control (pCON) parasites contains a single FRT site. pKO and pCON were transfected into TRAP/FlpL erythrocytic stage parasites. C, a Southern hybridization is shown to confirm integration of pKO into the PbPKG locus. SpeI-digested genomic DNA from parental TRAP/FlpL parasites and the cKO clone was probed with labeled exon 5. Integration of the construct at the wild type locus is revealed by the presence of a 7.8-kb fragment. D, shown is PCR amplification using primers 1 and 2 to probe the PbPKG locus in cKO erythrocytic stages (lane 1), cKO sporozoites (lane 2), CON erythrocytic stages (lane 3), CON sporozoites (lane 4), and wild type (WT) erythrocytic stages (lane 5). Excision (E) of exons 4–5 in cKO sporozoites generated a 0.6-kb product. The 1.5-kb product is a result of nonspecific amplification. The non-excised (NE) locus generated a 5.5-kb product in cKO erythrocytic stages, CON erythrocytic stages, and CON sporozoites and a 3.5-kb product in wild type parasites.

The cKO and CON clones were passaged into mosquitoes maintained at 20 °C until day 14 post-bloodmeal. On day 14, infected mosquitoes were transferred to 25 °C to increase the activity of FlpL and, hence, the efficiency of DNA excision at the PbPKG locus. Sporozoites that developed from the cKO and CON parasite populations were collected from mosquito salivary glands on days 18–21, post-bloodmeal. As shown in Fig. 2C, excision at the PbPKG locus was undetectable in the erythrocytic stages but was readily detected in the sporozoite population of the cKO clone. In contrast, the PbPKG locus was intact in both the erythrocytic stages and the sporozoite population of the CON clone, which lacks the 5′-FRT site. Henceforth, cKO parasites with a disrupted PbPKG locus are referred to as “PbPKG−,” and those with the intact locus are referred to as “PbPKG+.”

PbPKG Sporozoites Do Not Lead to a Blood Stage Infection but Develop into Late Liver Stages

To study the function of PbPKG in the parasite mammalian host, cKO and CON sporozoites were injected intravenously into mice. Excision of PbPKG in the cKO sporozoite population would generate parasites lacking PbPKG function (PbPKG−), whereas lack of excision would generate parasites in which PbPKG function was normal (PbPKG+). Although all animals infected with CON sporozoites became patent, i.e. displayed detectable blood-stage infection (p > 0.01%), by day 7, none of the animals infected with cKO population were patent at day 7 (Fig. 3, A and B). Four of the five mice infected with the cKO population stayed negative for the course of the experiment (animals were sacrificed at day 15).

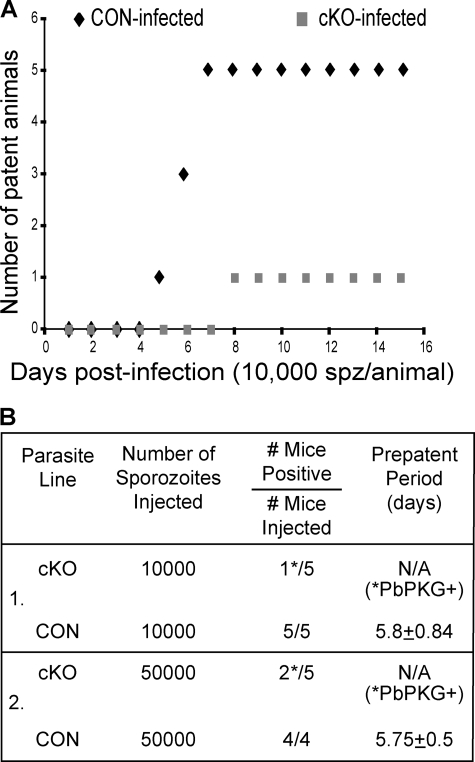

FIGURE 3.

Infectivity of the cKO sporozoite population as determined by pre-patent period. A, groups of 5 animals were infected with cKO or CON sporozoites (10,000 sporozoites/animal). Animals were checked daily for the appearance of erythrocytic stages. The number of animals patent on each day post-infection is shown. B, groups of C57Bl/6 mice were infected with different doses of cKO or CON sporozoites via intravenous injection to determine the pre-patent period of infection (±S.D.). The number of animals in each group that were positive for erythrocytic stages is shown. Asterisks indicate that analysis of genomic DNA from parasites obtained from these animals revealed the presence only PbPKG+ parasites, which develop when cKO sporozoites do not undergo the expected DNA excision (Fig. 4).

One of the five animals infected with the cKO population became patent on day 8. PCR analysis of the genomic DNA of parasites collected from this animal detected only a ∼5.2-kb fragment corresponding to the non-excised version of the PbPKG cKO locus (Fig. 4). Therefore, this animal had been infected by the small fraction of the cKO sporozoite population that escaped DNA excision and carried an intact PbPKG locus (PbPKG+). The delayed patency displayed by the infected animal (day 8 versus day 5.8 on average for CON-infected animals) suggests that the percentage of sporozoites that escape excision, is small because a 10-fold decrease in sporozoite number generally leads to a delay of 1 day in the pre-patent period. In an independent experiment a higher infectious dose of the cKO sporozoite population also did not result in blood-stage infection by PbPKG− parasites (Fig. 3B). As before, the two animals that developed blood stage infections were infected only with PbPKG+ parasites (data not shown). These data confirm that PbPKG− sporozoites do not develop into erythrocytic stage parasites.

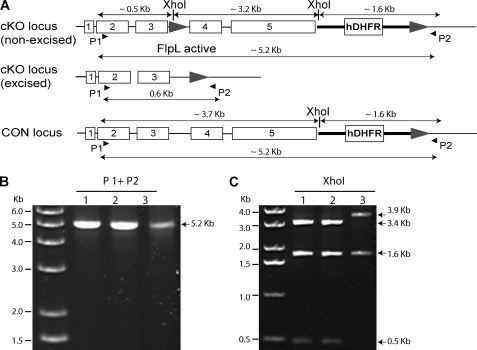

FIGURE 4.

Analysis of erythrocytic stage parasites obtained after infection by the cKO sporozoite population. A, the PbPKG loci in cKO parasites before DNA excision and CON parasites are differentiated by the presence of an XhoI site in the 5′ FRT site of cKO parasites. Amplification of the PbPKG locus using primers 1 (P1) and 2 (P2) (arrowheads) generates a product of ∼5.2 kb from the non-excised cKO and the CON loci and 0.6 kb from the excised cKO locus. Digestion of the ∼ 5.2-kb product (P1+P2) with XhoI produces 3 fragments in cKO and 2 fragments in CON parasites. B, shown is a PCR analysis of the PbPKG locus present in parasites recovered from the mouse made patent by an infection with the cKO sporozoite population (lane 1), the cKO clone used for mosquito feeding (lane 2), and the CON clone (lane 3). PCR detected the presence only of non-excised PbPKG loci (PbPKG+) in lane 1. C, the PCR products (P1+P2) were digested with XhoI to confirm that the amplified product in lane 1 was from the cKO non-excised locus.

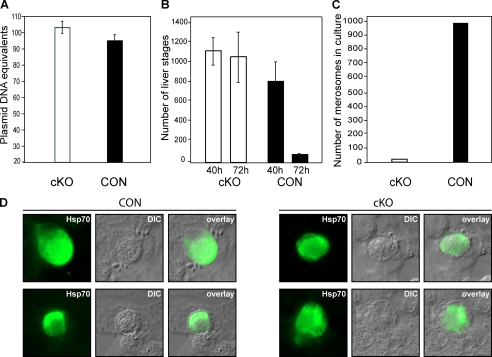

Next we examined if the lack of blood-stage infection by PbPKG− parasites was a result of impaired liver stage development. Using real-time PCR, we quantified liver infection in vivo 40 h post-infection of mice by cKO and CON sporozoites (Fig. 5A). We did not find a significant difference in parasite burden in the two groups of infected animals. These data suggested that cKO sporozoites are competent to initiate hepatocyte infection and undergo intrahepatic development. To examine liver stage development in greater detail, we used the cultured hepatoma cell line, HepG2. Development of cKO and CON parasites in HepG2 cells was followed by immunostaining of the cells with a parasite-specific antibody against Hsp70 (18). We observed that PbPKG cKO and CON sporozoites formed similar numbers of LSs at 40 h post-infection, consistent with the in vivo results (Fig. 5B). There were no significant morphological differences between cKO and CON LSs. However, at 72 h post-infection, the number of LSs in CON-infected cells declined significantly (Fig. 5B), and merosomes were released into the medium (65–72 h post-infection) (Fig. 5C). In contrast, in cKO-infected cells, the number of LSs remained high, and few merosomes were observed in the medium (Fig. 5C). These data suggest that cKO parasites are blocked at a late step in LS development.

FIGURE 5.

Liver stage development in cKO parasites. A, real-time PCR was used to quantify the infectivity of cKO sporozoites in vivo. The average parasite load (±S.D.) in the livers of cKO or CON-infected mice is expressed as equivalent to plasmid copies of the P. berghei 18S rRNA gene. B, LS that developed 40 and 72 h post-infection of HepG2 cells with either cKO or CON sporozoites were detected using immunofluorescence assays (n = 2 or 3). C, merosomes released into the medium of cKO or CON-infected HepG2 cells were collected 65 h post-infection and quantified. Results from a typical experiment are shown. D, shown are representative images of CON and cKO LS in HepG2 cells, 65 h post-infection. LSs were stained with an anti-parasite Hsp70 antibody. Cells were examined at 100× magnification using fluorescence and differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy.

Immunization with PbPKG cKO Sporozoites Protects from Malaria

Although early LS parasites are known to elicit a protective host response (4, 5, 23), the ability of late liver stages to elicit such immunity is unknown. We tested if immunization with cKO sporozoites would confer protection to immunized animals from a sporozoite challenge. Groups of C57Bl/6 mice, a mouse strain susceptible to P. berghei infection, were immunized and boosted with cKO sporozoites before infection with wild type sporozoites. We observed that whereas control non-immunized animals became patent, the immunized animals remained negative for the duration of the experiment (Table 1). These results suggest that the developmentally arrested LSs of cKO parasites are capable of eliciting a protective immune response from the host. That cKO LSs arrest later than previously identified LS mutants that induce immunity (3, 5, 7) implies that antigens present in late LSs, similar to those present in early LSs, might elicit a protective host immune response.

TABLE 1.

Protection after immunization with the cKO sporozoite population

In two independent experiments, C57Bl/6 mice were immunized and boosted twice (at days 14 and 21 post-immunization) with PbPKG cKO sporozoite population. They were challenged with wild type P. berghei sporozoites at day 28 post-immunization. As a control, age-matched non-immunized mice were challenged identically. The appearance of blood-stage parasites in both groups of animals was monitored daily through examination of Giemsa-stained blood smears. The number of challenged animals that were patent at day 21 post-challenge in both groups is displayed. The pre-patent period of infection in both groups of animals was determined.

| Immunization PbPKG cKO | Boosts PbPKG cKO | Challenge wild type | No. of patent animals/no. of challenged animals (pre-patency ± S.D.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 50,000 | 25,000 (day 14) | 10,000 (day 28) | 0/10 (day 21) |

| 25,000 (day 21) | |||

| None | None | 10,000 | 10/10 |

| (5.8 ± 0.42) | |||

| 50,000 | 25,000 (day 14) | 10,000 (day 28) | 0/6 (day 21) |

| 25,000 (day 21) | |||

| None | None | 10,000 | 6/6 |

| (3.7 ± 0.52) |

DISCUSSION

Our work demonstrates for the first time that late LSs might elicit a protective immune response from the host against future sporozoite challenge. It has been well appreciated that early LSs elicit such protection, stimulating efforts to identify antigens present in these stages. These attempts have been hampered by the difficulty in obtaining sufficient early LSs for analysis. The possibility that late LSs might elicit a protective host-response was suggested by the immunity elicited in rodents and humans after vaccination by live sporozoites and treatment with chloroquine (24, 25). These studies demonstrated that such immunization leads to protection against a future sporozoite challenge. However, these studies could not distinguish between immunity elicited by late LS and the erthrocytic stages because even under chloroquine cover, parasite development proceeds until at least the first round of erythrocytic development. Our study demonstrates that late LSs do elicit a protective immune response and implies that the search for protective antigens can be expanded to include antigens expressed in late LSs. It is highly likely that late LSs share antigens with erythrocytic stages, as a proteome analysis of liver stages demonstrated a large overlap with proteins expressed in intraerythorcytic stages (22). Therefore, immunization with late LS antigens might provide protection against erythrocytic stage parasites in addition to the currently demonstrated protection against sporozoites. It is also possible that protective antigens present in early LS persist in late LS and induce protection. It will be interesting to test if late LSs can elicit protection in mice tolerant for the major early LS antigen, the circumsporozoite protein. Future work will compare the protection induced by late LSs versus early LS that form from radiation or genetically attenuated sporozoites and their respective mechanisms of protection (26, 27).

The multiple essential roles of PKG make it a potential drug target. Despite the presence of mammalian homologs, the possibility of specific inhibition is suggested by the presence of a small molecule inhibitor Compound 1 that demonstrates potency against Apicomplexan PKGs, including P. falciparum PKG, but not against the mammalian enzyme (15). An inhibitor of parasite PKG would block the parasite life cycle at multiple steps, making it a valuable addition to malaria chemotherapy. It could be used prophylactically to prevent the development of the symptomatic erythrocytic cycle and therapeutically to treat blood-stage infection.

Our work sheds light on the signaling pathways that function during LS development. The late developmental arrest of PbPKG cKO parasites suggests a role for PbPKG in either the formation of hepatic merozoites or their exit from hepatocytes via merosome formation. Further analysis using green fluorescent protein-positive cKO parasites will help in determining the exact defect in these parasites. Our work also reveals the multiple roles played by PKG in the Plasmodium life cycle during the erythrocytic cycle, gametogenesis, and liver stage development. It points to the importance of cGMP-based signaling in the parasite life-cycle, particularly at transitional points. Identification of PKG cellular targets and regulators is key to understanding the signaling cascade used to translate changes in cGMP levels into physiological effects.

During parasite gametogenesis, PKG is posited to function upstream of a Ca2+-sensitive pathway that is required for exflagellation in male gametes. Although its exact role in LSs remains unclear, it is interesting to note that merozoites developing in infected hepatocytes appear to sequester Ca2+ relative to the host cytoplasm, possibly to prevent the display of a phagocytic signal, phosphatidylserine, on the outer leaflet of the hepatocyte plasma membrane. The presence of Ca2+-sensitive pathways during both gametogenesis and liver stage development might suggest a common mechanism of action of PKG at these two stages.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank Dr. P. Sinnis and Dr. J. Raper for helpful comments on the manuscript and Dr. J. Hahn for help with microscopy.

This work was supported by American Heart Association Grant 0735036N (to P. B.).

- LS

- liver stage(s)

- FRT

- Flp recognition target sequences

- RT

- reverse transcriptase

- Hsp70

- heat shock protein 70

- TRAP

- thrombospondin-related anonymous protein

- PKG

- cGMP-dependent protein kinase

- PbPKG

- P. berghei PKG

- cKO

- conditional knock-out

- CON

- control.

REFERENCES

- 1.Prudêncio M., Rodriguez A., Mota M. M. (2006) Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4, 849–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sturm A., Amino R., van de Sand C., Regen T., Retzlaff S., Rennenberg A., Krueger A., Pollok J. M., Menard R., Heussler V. T. (2006) Science 313, 1287–1290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aly A. S., Mikolajczak S. A., Rivera H. S., Camargo N., Jacobs-Lorena V., Labaied M., Coppens I., Kappe S. H. (2008) Mol. Microbiol. 69, 152–163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mueller A. K., Camargo N., Kaiser K., Andorfer C., Frevert U., Matuschewski K., Kappe S. H. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 3022–3027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mueller A. K., Labaied M., Kappe S. H., Matuschewski K. (2005) Nature 433, 164–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silvie O., Goetz K., Matuschewski K. (2008) PLoS Pathog. 4, e1000086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Dijk M. R., Douradinha B., Franke-Fayard B., Heussler V., van Dooren M. W., van Schaijk B., van Gemert G. J., Sauerwein R. W., Mota M. M., Waters A. P., Janse C. J. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 12194–12199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaughan A. M., O'Neill M. T., Tarun A. S., Camargo N., Phuong T. M., Aly A. S., Cowman A. F., Kappe S. H. (2009) Cell. Microbiol. 11, 506–520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu M., Kumar T. R., Nkrumah L. J., Coppi A., Retzlaff S., Li C. D., Kelly B. J., Moura P. A., Lakshmanan V., Freundlich J. S., Valderramos J. C., Vilcheze C., Siedner M., Tsai J. H., Falkard B., Sidhu A. B., Purcell L. A., Gratraud P., Kremer L., Waters A. P., Schiehser G., Jacobus D. P., Janse C. J., Ager A., Jacobs W. R., Jr., Sacchettini J. C., Heussler V., Sinnis P., Fidock D. A. (2008) Cell Host Microbe 4, 567–578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishino T., Boisson B., Orito Y., Lacroix C., Bischoff E., Loussert C., Janse C., Ménard R., Yuda M., Baldacci P. (2009) Cell. Microbiol. 11, 1329–1339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galinski M. R., Barnwell J. W. (2008) Malar. J. 7, Suppl 1, S9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rénia L. (2008) Parasite 15, 379–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baker D. A., Kelly J. M. (2004) Trends Parasitol. 20, 227–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McRobert L., Taylor C. J., Deng W., Fivelman Q. L., Cummings R. M., Polley S. D., Billker O., Baker D. A. (2008) PLoS Biol. 6, e139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gurnett A. M., Liberator P. A., Dulski P. M., Salowe S. P., Donald R. G., Anderson J. W., Wiltsie J., Diaz C. A., Harris G., Chang B., Darkin-Rattray S. J., Nare B., Crumley T., Blum P. S., Misura A. S., Tamas T., Sardana M. K., Yuan J., Biftu T., Schmatz D. M. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 15913–15922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Combe A., Giovannini D., Carvalho T. G., Spath S., Boisson B., Loussert C., Thiberge S., Lacroix C., Gueirard P., Ménard R. (2009) Cell Host Microbe 5, 386–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janse C. J., Ramesar J., Waters A. P. (2006) Nat. Protoc. 1, 346–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsuji M., Mattei D., Nussenzweig R. S., Eichinger D., Zavala F. (1994) Parasitol. Res. 80, 16–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhanot P., Schauer K., Coppens I., Nussenzweig V. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 6752–6760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deng W., Baker D. A. (2002) Mol. Microbiol. 44, 1141–1151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diaz C. A., Allocco J., Powles M. A., Yeung L., Donald R. G., Anderson J. W., Liberator P. A. (2006) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 146, 78–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tarun A. S., Peng X., Dumpit R. F., Ogata Y., Silva-Rivera H., Camargo N., Daly T. M., Bergman L. W., Kappe S. H. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 305–310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Douradinha B., van Dijk M. R., Ataide R., van Gemert G. J., Thompson J., Franetich J. F., Mazier D., Luty A. J., Sauerwein R., Janse C. J., Waters A. P., Mota M. M. (2007) Int. J. Parasitol. 37, 1511–1519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Belnoue E., Costa F. T., Frankenberg T., Vigário A. M., Voza T., Leroy N., Rodrigues M. M., Landau I., Snounou G., Rénia L. (2004) J. Immunol. 172, 2487–2495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roestenberg M., McCall M., Hopman J., Wiersma J., Luty A. J., van Gemert G. J., van de Vegte-Bolmer M., van Schaijk B., Teelen K., Arens T., Spaarman L., de Mast Q., Roeffen W., Snounou G., Rénia L., van der Ven A., Hermsen C. C., Sauerwein R. (2009) N. Engl. J. Med. 361, 468–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar K. A., Baxter P., Tarun A. S., Kappe S. H., Nussenzweig V. (2009) PLoS One 4, e4480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar K. A., Sano G., Boscardin S., Nussenzweig R. S., Nussenzweig M. C., Zavala F., Nussenzweig V. (2006) Nature 444, 937–940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]