Abstract

Endometriosis is a major cause of chronic pain, infertility, medical and surgical interventions, and health care expenditures. Tissue factor (TF), the primary initiator of coagulation and a modulator of angiogenesis, is not normally expressed by the endothelium; however, prior studies have demonstrated that both blood vessels in solid tumors and choroidal tissue in macular degeneration express endothelial TF. The present study describes the anomalous expression of TF by endothelial cells in endometriotic lesions. The immunoconjugate molecule (Icon), which binds with high affinity and specificity to this aberrant endothelial TF, has been shown to induce a cytolytic immune response that eradicates tumor and choroidal blood vessels. Using an athymic mouse model of endometriosis, we now report that Icon largely destroys endometriotic implants by vascular disruption without apparent toxicity, reduced fertility, or subsequent teratogenic effects. Unlike antiangiogenic treatments that can only target developing angiogenesis, Icon eliminates pre-existing pathological vessels. Thus, Icon could serve as a novel, nontoxic, fertility-preserving, and effective treatment for endometriosis.

Endometriosis is a gynecological disorder characterized by the presence of functional endometrial tissue outside of the uterus.1 The disease affects up to 10% of all reproductive-age women and up to 50% of infertile women.1,2,3 Endometriotic lesions are primarily located on the pelvic peritoneum and ovaries, but can also be found in the colon, pericardium, pleura, lung parenchyma, and brain.2 Implants can cause pelvic adhesions, chronic pelvic pain, bowel obstruction, and infertility requiring repetitive, extensive, and expensive medical and surgical treatments.1,4,5

The etiology of the disease has been ascribed to retrograde menstruation, coelomic metaplasia, or both.1,6,7,8,9 Although its pathogenesis involves a complex interplay of genetic, anatomical, environmental, and immunological factors, there is general agreement that it is associated with a local inflammatory response and that vascularization at the site of ectopic attachment of the lesions is a key determinant in its pathogenesis.1,10,11,12,13 Angiogenic agents such as vascular endothelial growth factor and the angiopoietins are likely mediators of endometriotic neovascularization.1,3,11,12,13

Tissue factor (TF), the transmembrane initiator of hemostasis, is not physiologically expressed by endothelial cells but plays a crucial role in embryonic and oncogenic angiogenesis.14,15,16,17 Recent studies indicate that the type-2 proteinase activated receptor (PAR-2) is intimately involved in TF-mediated signaling and angiogenesis.15,18,19 Tissue factor may initiate differential signaling pathways in physiological compared with pathological angiogenesis,20 to wit, the physiological pathway is mediated by TF–thrombin–PAR-1 and the pathological pathway by TF/factor FVIIa/PAR-2 signaling.20 These latter vessels display abnormal structure and function and are poorly associated with pericytes causing leakiness and edema.21,22

Our prior studies demonstrated that both TF and PAR-2 are up-regulated in endometria of women with endometriosis compared with unaffected women.23

In this report, we describe the anomalous endothelial expression of TF in ectopic endometrium derived from women with endometriosis. We posited that a novel chimeric immunoconjugate molecule (Icon) will specifically target endothelial TF in ectopic implants leading to their devascularization and atrophy. Icon is composed of a mutated low-coagulation–inducing factor VII (fVII) domain that binds to TF with high affinity and an IgG1 Fc (fVII/IgG1 Fc) effector domain that activates a natural killer cell cytolytic response against TF bearing endothelial cells.24,25,26,27 This report confirms our hypothesis by demonstrating that Icon largely destroys pre-established human endometriotic lesions in an athymic mouse model without untoward systemic effects, altered fertility, or subsequent teratogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Tissues

Control eutopic endometrial tissues were obtained from consenting fertile reproductive-age women free of clinical endometriosis undergoing endometrial sampling at the time of tubal ligation with five samples from the proliferative phase and five from the secretory phase. The age range was 29 to 38 years. Eutopic and ectopic endometria were obtained from women diagnosed with endometriosis at operative laparoscopy for chronic pelvic pain and/or infertility. In all subjects, endometriotic implants were resected and the diagnosis confirmed by histopathology (n = 6). Subjects were staged according to the revised American Fertility Society classification and were either in the mid to late proliferative phase.28 None of the subjects were treated with hormones in the two months preceding surgery. Patient age range was 27 to 49 years. All subjects provided informed consent, and this study was approved by the Yale University School of Medicine Human Investigation Committee as well as the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board and Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects.

Immunohistochemistry

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues were cut in 5-micron sections. Immunohistochemistry was performed as previously described.29,30 For confirmatory purposes, two antibodies to TF were used, a polyclonal antibody to human TF (hTF; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and a monoclonal antibody produced by one of the authors (W.K.). Both antibodies displayed identical staining patterns. The antibody to von Willebrand factor (vWF) Ab6994 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), an endothelial cell marker, recognized both human and mouse antigens. Specific staining of vessels for vWF was used to quantify vessel density by using Image J public domain software. Negative controls were conducted with an appropriate pre-immune serum. Detection of Icon used anti-human IgG (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) directed against the Fc potion of Icon. Sections were analyzed by digitally capturing a minimum of three fields per slide.

Icon

Mouse Icon protein was synthesized by stable transfection of Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells as previously described24,25,26 with modifications as follows. The transfected CHO cells were cultured in serum-free EXCELL 301 CHO medium (JRH Biosciences, Lenexa, KS) supplemented with a final concentration of 1 μg/ml of vitamin K1 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The Icon protein was purified from the culture medium by affinity chromatography on a HiTrap rProtein A FF 5 ml column (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ), dialyzed against 10 mmol/L HEPES pH 7.4, 150 mmol/L NaCl2, and 5 mmol/L CaCl2, and then concentrated with a Millipore filter with a cutoff molecular weight of 100,000 kDa (Millipore, Billerica, MA). The final concentration of the Icon was determined with the Bradford assay reagent (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The Icon is composed of two mature coagulation fVII peptides containing a mutation of Lys341 to Ala. Thus Icon is a natural ligand for TF, in which the mutated fVII is fused to the Fc domain of a human IgG1 antibody by recombinant DNA technology.25,26 The introduction of a mutation in the fVII portion of mouse and human Icon molecules was used to reduce their coagulation activity25 while retaining the binding activity to TF as previously reported.25,31

The Icon molecule is designed to bind to TF with far higher affinity and specificity than can be achieved with an anti-TF antibody. The Icon has several important advantages over monoclonal antibodies for targeting TF including: (1) The kDa for fVII binding to TF is up to 10−12 mol/L,32 whereas anti-TF antibodies have a kDa in the range of 10−8 to 10−9 mol/L33,34; (2) The Icon is produced by recombinant DNA technology, allowing for the generation mouse Icon (mouse fVII/human IgG1 Fc) for use in murine models of human diseases and human Icon (human fVII/human IgG1 Fc) for future clinical trials. Moreover, Icon obviates the necessity of generating humanized monoclonal antibodies. The basic principle of Icon therapy is that TF is inappropriately expressed by the endothelium of vessels in pathological tissues, and Icon targets this aberrant TF expression and induces an natural killer–mediated immune response that devascularizes the lesion.

Conjugation of Mouse Icon Protein with Fluorescein Isothiocyanate

Mouse Icon protein was conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) using the Pierce FITC antibody labeling kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) following the manufacturer’s instruction. Free dye was separated from the protein-conjugated FITC using resin and the conjugated FITC collected. The ratio of FITC to mouse Icon protein, calculated by measuring A280 nm for protein concentration and A495 nm for FITC concentration, was 3.5:1. Flow cytometry demonstrated that Icon–FITC conjugate bound a human melanoma TF2 cell line expressing high levels of TF.35 Immunofluorescent staining for CD31 and DAPI was conducted as previously described.36 The aim of Icon conjugation with FITC is to colocalize Icon binding to the CD31-positive endothelial cells.

In the colocalization study of Icon and CD31 expression, 10 μg of mouse FITC-conjugated Icon protein was injected into the peritoneal cavity (IP) of 12 athymic nude (ATN) mice, implanted with human endometrial tissues 12 days before FITC-Icon treatment. Controls were similarly injected IP with saline (n = 3). The endometrial lesions were removed from the FITC-Icon injected mice and from control mice at 4, 8, and 24 hours (n = 3) at each time point.

Athymic Nude Mouse Model

Endometrial tissues were acquired by Pipelle® biopsy (Unimar, Inc., Wilton, CT) from consenting healthy women during the proliferative phase (days 9 to 12) of the menstrual cycle (n = 5). The age range of the women spanned 36 to 41 years with a mean age of 38 years. All tissues were obtained from the mid to late proliferative phase of the menstrual cycle. An endometrial thickness ≥9 mm (confirmed by vaginal ultrasound) and a serum progesterone level of <1.5 ng/ml were required for inclusion in this study. Individuals with a history of hormone therapy (eg, gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist, oral contraceptives) within two months were excluded. Biopsies were washed in prewarmed phenol-red free Dulbecco’s Modified Eagles Medium/Ham’s F-12 Medium (DME/F-12; Sigma-Aldrich) to remove residual blood and mucous before culturing. Endometrial biopsies were dissected into small cubes (≈1 × 1 mm3) and 8 to 10 pieces of tissue per mouse were suspended in tissue culture inserts (Millipore, Bedford MA). Organ cultures were maintained for 18 to 24 hours before injection into mice under serum-free conditions in DME/F-12 supplemented with 1% Insulin-Transferrin-Selenium (ITS+; Collaborative Biomedical, Bedford MA), 0.1% Excyte (Miles Scientific, Kankakee IL), and 1 nmol/L 17β-estradiol (E2; Sigma-Aldrich). Cultures were incubated at 37°C in a humidified chamber with 5% CO2.

The model of endometriosis used in the current study has been previously described and validated.37 Briefly, six-week-old female ovariectomized ATN mice (Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN) were anesthetized with isoflurane (Henry Schein, Melville, NY) and subcutaneously implanted with a silastic capsule (Dow Corning Silastic Laboratory Tubing, 1/16 in. I.D.; 1/8 in. O.D.; Wall Thickness: 1/32 in.) containing 8 mg E2 in cholesterol (Sigma-Aldrich). The ends of the silastic tubes were sealed with Type A medical silicone adhesive (Factor II, Inc., Lakeside, AZ). Twenty-four hours after subcutaneous placement of the silastic capsules, mice received an IP injection of PBS containing a suspension of 8 to 10 human endometrial tissue fragments per mouse into the ventral midline just below the umbilicus. Treatment with Icon was initiated 10 to 12 days after the injection of tissue. Controls consisted of animals treated with saline or nonspecific murine IgG. After completion of the treatment regimen, mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation under anesthesia and direct examination of intraperitoneal lesion size and number were determined. Lesions were measured in two dimensions; the largest denoted “a” and the smallest denoted “b.” The total volume of lesions was calculated by standard methodology38 using the formula: V = a × 2b × 0.5. We conducted 5 separate studies using 5 endometrial biopsies. Each study used the biopsy from one patient. Because biopsies varied in size, the number of mice varied. Studies 1 to 5 used 10, 10, 12, 14, and 7 mice, respectively. We did not mix samples from different women. Residual lesions were removed and formalin-fixed/paraffin-embedded for analysis. Experiments described herein were approved by Vanderbilt University Instructional Animal Care and Use Committee in accordance with the Animal Welfare Act.

Toxicity, Fertility, and Teratogenicity Studies

Female ATN mice were treated IP with either Icon or vehicle control once a week for four weeks (n = 4 per group). Two weeks after the last injection, the mice were allowed to breed. Pregnancy was determined by a vaginal plug. For these experiments, adult and neonatal mice were euthanized by carbon dioxide inhalation. Mice were necropsied and tissues evaluated blinded to the experimental manipulation. All of the tissues were harvested from each adult mouse and fetus/neonate. Whole fetuses, pups, and adults, their respective sterna, one rear leg, and head with skull cap and skin removed were placed in Bouin’s Fixative (VWR International, Batavia IL). The remaining adult mouse tissues were placed in 10% Neutral Buffered Formalin (VWR International, Batavia IL). A routine selection of tissues from all organ systems in adult mice were chosen for histopathological examination. Two fetuses and two neonatal pups were selected from each litter for histopathological examination. All selected tissues were processed, embedded in paraffin, sectioned to 5 microns, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) (Sigma-Aldrich). All mice were examined visually at necropsy for macroscopic lesions and all tissue sections were examined using light microscopy for experimentally induced pathological changes.

Results

Immunohistochemistry

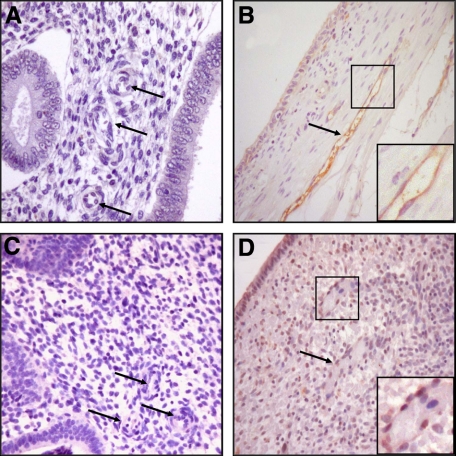

Figure 1, A–D demonstrates a failure to detect endothelial TF by immunostaining in proliferative eutopic endometrium (Figure 1, A and C), whereas ectopic endometrium from the same patient displays strong immunostaining for endothelial TF (Figure 1, B and D). This finding of high TF expression by endometrial ectopic endothelium led us to determine whether administration of the TF-targeting Icon molecule would eliminate such implants in a mouse model of endometriosis.

Figure 1.

Expression of TF in endothelial cells from human ectopic endometrium: Immunohistochemistry was performed as described in the Methods. Eutopic proliferative endometrium from patients with endometriosis showing low to no TF staining in glands or stromal cells; vessels walls and endothelial cells are unstained (arrows) (original magnification, ×100; A and C); ectopic endometriotic implants from the same patients, respectively, displaying strong TF immunostaining in endothelial cells (arrows) with moderate TF immunostaining of ectopic glands and stromal cells (original magnification, ×100; B and D). (n = 6).

Treatment of Endometriosis with Icon in a Murine Model

The ATN mice were injected with approximately 1.0 ml packed endometrial tissue and treated as described in Methods. On gross morphological examination, 11 of 15 treated mice had no sign of residual disease after 4 weekly 10-μg Icon treatments compared with 5 of 12 mice treated with a 5-μg Icon dose. By contrast, 12 of 13 mice treated with vehicle control had well-defined endometrial lesions (Table 1). Residual lesions in Icon-treated mice were significantly smaller than those found in control animals (Table 1), and it was difficult to observe any vascularization (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Effect of Icon Treatment on Mice with Endometriotic Lesions

| Mouse Tx | Avg. vessel size (arbitrary units) | P | No. of mice with disease per total number | % with disease | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 2.88 | 12/13 | 92% | ||

| Icon (5 μg) | 1.21 | <0.05 | 7/12 | 58% | NS |

| Icon (10 μg) | 1.50 | <0.05 | 4/15 | 27% | <0.05 |

All mice were treated as described in Methods. P refers to the level of significance.

Figure 2.

Gross morphological analysis: Representative lesions from placebo (left) or 10-μg Icon-treated (right) ATN mice with established human endometriotic lesions displaying obvious differences in gross surface vascularization (n = 15). Arrows point to the lesions.

To quantify the effects of 5- or 10-μg Icon treatments versus vehicle control on vessel morphology, lesions were removed, formalin-fixed, and paraffin-embedded as described in Methods. Immunohistochemistry with an antibody against vWF was used to detect vascular endothelium. As shown in Figure 3, treatment with 10 μg Icon resulted in vessels that were quantitatively smaller in caliber with an aberrant appearance compared with controls. Vessel number and size were then assessed by the public domain software Image J in mice treated with either vehicle control, or 5 or 10 μg of Icon. Treatment with 10 μg Icon resulted in a statistically significant decrease in vessel size compared with saline treated controls (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Microscopic endometriotic vessel analysis: Vessels in human peritoneal endometriotic implants present in ATN mice were visualized by immunohistochemical staining for vWF after treatment with vehicle control (A) or 10 μg Icon (B; n = 5, ×200). C: Morphometric analysis demonstrated that both 5 and 10 μg Icon resulted in a significant decrease in vessel size in mice with residual lesions. Vessel size is reported in arbitrary units. Statistical analysis was conducted by analysis of variance (n = 5, *P < 0.05).

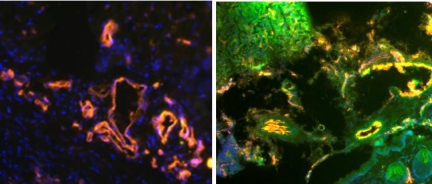

To confirm the tissue localization of Icon binding in the mouse endometriosis model, FITC-conjugated Icon (10 μg) or vehicle control was injected IP for 4, 8, and 24 hours (n = 6 at each time point). Figure 4 indicates that no FITC fluorescence was detected in control mice, whereas blood vessels stain red (mouse-CD31) and the nuclei stain blue (DAPI). By contrast, tissues extracted four hours after injection of FITC labeled Icon (green) show all three colors, colocalization of red and green dyes in endothelium is indicated by the color yellow, supporting the conclusion that Icon disrupts endometriotic lesions by targeting the vascular endothelium.

Figure 4.

Immunofluorescence for Icon: Human endometrium recovered from control treated mouse was immunostained consecutively for CD31 (detected with phycoerythrin) and DAPI (blue; left). Endometriotic lesion in an ATN mouse extracted four hours after injection with FITC-labeled Icon (green) were also stained with CD31 and DAPI (right). (×400, n = 3).

Toxicity, Fertility, and Teratogenicity Studies

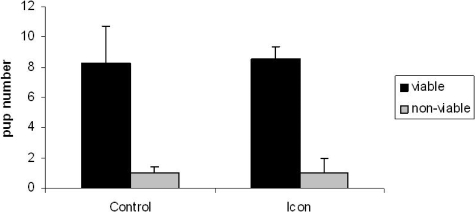

The systemic and reproductive effects of prior Icon treatment (10 μg) on fertility were conducted as described in Methods. We observed that ATN mice treated with Icon once a week for four weeks conceived normally and had the same pregnancy rates as control ATN mice. Figure 5 demonstrates that the average number of viable embryos/ live born pups was 8.25 per litter for control and 8.5 for mice previously treated with Icon; similar to the reported average litter size of seven for ATN (personal communication, March 25, 2009, Jay Aeyers Harlan Laboratories Technical Support). All pregnancies progressed normally. Histopathological examination of tissues from control and Icon-treated adult pregnant or postpartum female ATN mice showed no systemic or reproductive tract pathology. Specifically, heart, lung, brain, liver, kidney, spleen, bone, muscle, or GI tract displayed no pathological abnormalities in either treated or untreated animals. All embryos and postnatal day 1 mice collected at less than six hours after birth from control and Icon-treated mice appeared grossly and histologically normal with no evidence of teratogenic effects. All embryos and postnatal day 1 mice collected at less than six hours after birth from control and Icon-treated mice appeared grossly and histologically normal. All pups fed and milk contents were visible in their stomach.

Figure 5.

Fertility studies: ATN mice were treated with Icon or placebo once a week for four weeks. Two weeks after the last Icon treatment, mice were mated. All mice conceived. The average number of viable pups is shown in dark bars, whereas the number of nonviable pups is shown in light bars (n = 4 per group; *P < 0.05).

Discussion

Prior studies from our laboratory demonstrated that in normal endometrium, progestin markedly enhanced TF protein and mRNA expression in decidualized stromal cells during the luteal phase and in decidual cells through term.30,39,40,41 We have also shown that glandular epithelial cells display minimal TF expression throughout the menstrual cycle.30,39,40 The present study sought to determine the pattern and extent of TF expression in endometriosis and observed anomalous endothelial expression of TF in ectopic versus eutopic endometrium. This expression likely reflects the strong association of endometriosis with increased inflammatory cytokine production.3,42,43 Interleukin-1β and tumor necrosis factor-α acting via the NFκB transcription factor increase TF gene expression in endothelial cells from various tissues.44 Increased TF expression in endometrial endothelial cells may also reflect genetic polymorphisms in the promoter region of genes known to regulate TF expression as well as the TF promoter region.45,46,47

The aberrant expression of TF in ectopic endometrial endothelium suggested that this TF expression might be an ideal therapeutic target for endometriosis. Toward this end, we used the immunoconjugate molecule, Icon, in a mouse model of endometriosis. Previous studies demonstrated that Icon targeted TF that was aberrantly expressed by endothelial cells in malignant tumors.24,25,26 Icon also reduced the formation of pathological choroidal neovasculature associated with macular degeneration.48,49 Thus, Icon specifically targets endothelial TF expression in pathological vasculature while having no effects on normal vessels. In this study we demonstrate that Icon therapy largely destroys previously established and well-vascularized human endometriotic lesions in a mouse model of endometriosis. Because spontaneous endometriosis occurs only in women and in nonhuman primates, future studies will hopefully involve an animal model that mimics the human disease as described by D’Hooghe and coworkers.50

Importantly, because Icon targets not only neoangiogenesis, but pre-existing vessels aberrantly expressing TF in their endothelium, it is the only available agent with the potential to successfully treat pre-existent well-vascularized lesions. This is an important point, as women suffering from endometriosis are typically not diagnosed for several years51,52 and thus would already have established lesions. Although several treatments for endometriosis are available, they are associated with high recurrence rates and considerable side effects.53 Prior studies have confirmed that Icon treatment does not produce toxicity in various animal species,24,26,48,49,54 and we confirm no untoward effects on adult mice treated with Icon. In addition, we now report that Icon treatment does not interfere with subsequent fertility nor does it give rise to teratogenic effects. Hence, Icon may be an ideal drug of choice in the treatment of endometriosis and in particular for reproductive-age women suffering with this disease who desire subsequent fertility.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. Graciela Krikun or Dr. Zhiwei Hu, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences, Yale University, School of Medicine, 333 Cedar St., PO Box 208063, New Haven, CT 06520-8063. E-mail: graciela.krikun@yale.edu or zhiwei.hu@yale.edu.

Supported in part by grants from the NIH U54HD052668, and the Swebilius Translational Cancer Research Award from Yale Cancer Center (to Z.H.).

References

- Giudice LC, Kao LC. Endometriosis. Lancet. 2004;364:1789–1799. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17403-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe-Timms KL, Young SL. Understanding endometriosis is the key to successful therapeutic management. Fertil Steril. 2004;81:1201–1203. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.09.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RN, Lebovic DI, Mueller MD. Angiogenic factors in endometriosis. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2002;955:89–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb02769.x. discussion 118:396–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nezhat C, Crowgey SR, Garrison CP. Surgical treatment of endometriosis via laser laparoscopy and videolaseroscopy. Contrib Gynecol Obstet. 1987;16:303–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surrey ES, Schoolcraft WB. Management of endometriosis-associated infertility. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2003;30:193–208. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8545(02)00061-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazvani R, Templeton A. New considerations for the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2002;76:117–126. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(01)00577-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney AF. Etiology and histogenesis of endometriosis. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1990;323:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimura T, Masuzaki H. Peritoneal endometriosis: endometrial tissue implantation as its primary etiologic mechanism. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;165:210–214. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)90253-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oral E, Arici A. Pathogenesis of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1997;24:219–233. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8545(05)70301-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto J, Sakaguchi H, Hirose R, Wen H, Tamaya T. Angiogenesis in endometriosis and angiogenic factors. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1999;48:14–20. doi: 10.1159/000052864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XF, Charnock-Jones DS, Zhang E, Hiby S, Malik S, Day K, Licence D, Bowen JM, Gardner L, King A, Loke YW, Smith SK. Angiogenic growth factor messenger ribonucleic acids in uterine natural killer cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:1823–1834. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.4.7418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahnke JL, Dawood MY, Huang JC. Vascular endothelial growth factor and interleukin-6 in peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2000;73:166–170. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(99)00466-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaren J, Prentice A, Charnock-Jones DS, Millican SA, Muller KH, Sharkey AM, Smith SK. Vascular endothelial growth factor is produced by peritoneal fluid macrophages in endometriosis and is regulated by ovarian steroids. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:482–489. doi: 10.1172/JCI118815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P, Mackman N, Moons L, Luther T, Gressens P, Van Vlaenderen I, Demunck H, Kasper M, Breier G, Evrard P, Muller M, Risau W, Edgington T, Collen D. Role of tissue factor in embryonic blood vessel development. Nature. 1996;383:73–75. doi: 10.1038/383073a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Versteeg HH, Peppelenbosch MP, Spek CA. Tissue factor signal transduction in angiogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:1009–1013. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgg039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugge TH, Xiao Q, Kombrinck KW, Flick MJ, Holmback K, Danton MJ, Colbert MC, Witte DP, Fujikawa K, Davie EW, Degen JL. Fatal embryonic bleeding events in mice lacking tissue factor, the cell-associated initiator of blood coagulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6258–6263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey JR, Kratzer KE, Lasky NM, Stanton JJ, Broze GJ., Jr Targeted disruption of the murine tissue factor gene results in embryonic lethality. Blood. 1996;88:1583–1587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chand HS, Ness SA, Kisiel W. Identification of a novel human tissue factor splice variant that is upregulated in tumor cells. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1713–1720. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackman N. Gene targeting in hemostasis. tissue factor. Front Biosci. 2001;6:D208–D215. doi: 10.2741/mackman. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belting M, Dorrell MI, Sandgren S, Aguilar E, Ahamed J, Dorfleutner A, Carmeliet P, Mueller BM, Friedlander M, Ruf W. Regulation of angiogenesis by tissue factor cytoplasmic domain signaling. Nat Med. 2004;10:502–509. doi: 10.1038/nm1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joussen AM. Vascular plasticity–the role of the angiopoietins in modulating ocular angiogenesis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2001;239:972–975. doi: 10.1007/s004170100365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh K, Thodeti CK, Dudley AC, Mammoto A, Klagsbrun M, Ingber DE. Tumor-derived endothelial cells exhibit aberrant Rho-mediated mechanosensing and abnormal angiogenesis in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:11305–11310. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800835105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krikun G, Schatz F, Taylor H, Lockwood CJ. Endometriosis and tissue factor. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2008;1127:101–105. doi: 10.1196/annals.1434.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z, Garen A. Intratumoral injection of adenoviral vectors encoding tumor-targeted immunoconjugates for cancer immunotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:9221–9225. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.9221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z, Garen A. Targeting tissue factor on tumor vascular endothelial cells and tumor cells for immunotherapy in mouse models of prostatic cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:12180–12185. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201420298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z, Sun Y, Garen A. Targeting tumor vasculature endothelial cells and tumor cells for immunotherapy of human melanoma in a mouse xenograft model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8161–8166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.8161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osteen KG, Bruner-Tran KL, Ong D, Eisenberg E. Paracrine mediators of endometrial matrix metalloproteinase expression: potential targets for progestin-based treatment of endometriosis. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2002;955:139–146; discussion 157–158, 396–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb02774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1997. Revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine classification of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1996;67:817–821. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(97)81391-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krikun G, Critchley H, Schatz F, Wan L, Caze R, Baergen RN, Lockwood CJ. Abnormal uterine bleeding during progestin-only contraception may result from free radical-induced alterations in angiopoietin expression. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:979–986. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64258-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood CJ, Nemerson Y, Guller S, Krikun G, Alvarez M, Hausknecht V, Gurpide E, Schatz F. Progestational regulation of human endometrial stromal cell tissue factor expression during decidualization. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;76:231–236. doi: 10.1210/jcem.76.1.8421090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson CD, Kelly CR, Ruf W. Identification of surface residues mediating tissue factor binding and catalytic function of the serine protease factor VIIa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14379–14384. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waxman E, Ross JB, Laue TM, Guha A, Thiruvikraman SV, Lin TC, Konigsberg WH, Nemerson Y. Tissue factor and its extracellular soluble domain: the relationship between intermolecular association with factor VIIa and enzymatic activity of the complex. Biochemistry. 1992;31:3998–4003. doi: 10.1021/bi00131a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presta L, Sims P, Meng YG, Moran P, Bullens S, Bunting S, Schoenfeld J, Lowe D, Lai J, Rancatore P, Iverson M, Lim A, Chisholm V, Kelley RF, Riederer M, Kirchhofer D. Generation of a humanized, high affinity anti-tissue factor antibody for use as a novel antithrombotic therapeutic. Thromb Haemost. 2001;85:379–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchhofer D, Moran P, Chiang N, Kim J, Riederer MA, Eigenbrot C, Kelley RF. Epitope location on tissue factor determines the anticoagulant potency of monoclonal anti-tissue factor antibodies. Thromb Haemost. 2000;84:1072–1081. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromberg ME, Konigsberg WH, Madison JF, Pawashe A, Garen A. Tissue factor promotes melanoma metastasis by a pathway independent of blood coagulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8205–8209. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans AL, Bryant J, Skepper J, Smith SK, Print CG, Charnock-Jones DS. Vascular development in embryoid bodies: quantification of transgenic intervention and antiangiogenic treatment. Angiogenesis. 2007;10:217–226. doi: 10.1007/s10456-007-9076-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruner-Tran KL, Zhang Z, Eisenberg E, Winneker RC, Osteen KG. Down-regulation of endometrial matrix metalloproteinase-3 and -7 expression in vitro and therapeutic regression of experimental endometriosis in vivo by a novel nonsteroidal progesterone receptor agonist, tanaproget. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:1554–1560. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson G, Gullberg B, Hafstrom L. Estimation of liver tumor volume using different formulas - an experimental study in rats. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1983;105:20–23. doi: 10.1007/BF00391826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krikun G, Schatz F, Mackman N, Guller S, Demopoulos R, Lockwood CJ. Regulation of tissue factor gene expression in human endometrium by transcription factors Sp1 and Sp3. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:393–400. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.3.0430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood CJ, Nemerson Y, Krikun G, Hausknecht V, Markiewicz L, Alvarez M, Guller S, Schatz F. Steroid-modulated stromal cell tissue factor expression: a model for the regulation of endometrial hemostasis and menstruation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;77:1014–1019. doi: 10.1210/jcem.77.4.8408448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood CJ, Murk W, Kayisli UA, Buchwalder LF, Huang ST, Funai EF, Krikun G, Schatz F. Progestin and thrombin regulate tissue factor expression in human term decidual cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:2164–2170. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arici A, Seli E, Zeyneloglu HB, Senturk LM, Oral E, Olive DL. Interleukin-8 induces proliferation of endometrial stromal cells: a potential autocrine growth factor. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:1201–1205. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.4.4743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RN, Ryan IP, Moore ES, Hornung D, Shifren JL, Tseng JF. Angiogenesis and macrophage activation in endometriosis. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1997;828:194–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb48540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry GC, Mackman N. Transcriptional regulation of tissue factor expression in human endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995;15:612–621. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.15.5.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reny JL, Laurendeau I, Fontana P, Bieche I, Dupont A, Remones V, Emmerich J, Vidaud M, Aiach M, Gaussem P. The TF-603A/G gene promoter polymorphism and circulating monocyte tissue factor gene expression in healthy volunteers. Thromb Haemost. 2004;91:248–254. doi: 10.1160/TH03-09-0566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara Y, Iwasaki H, Ota N, Nakajima T, Kodaira M, Kajita M, Shiba T, Emi M. Novel single nucleotide polymorphisms of the human nuclear factor kappa-B 2 gene identified by sequencing the entire gene. J Hum Genet. 2001;46:50–51. doi: 10.1007/s100380170127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun XF, Zhang H. NFKB and NFKBI polymorphisms in relation to susceptibility of tumour and other diseases. Histol Histopathol. 2007;22:1387–1398. doi: 10.14670/HH-22.1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bora PS, Hu Z, Tezel TH, Sohn JH, Kang SG, Cruz JM, Bora NS, Garen A, Kaplan HJ. Immunotherapy for choroidal neovascularization in a laser-induced mouse model simulating exudative (wet) macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:2679–2684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0438014100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tezel TH, Bodek E, Sonmez K, Kaliappan S, Kaplan HJ, Hu Z, Garen A. Targeting tissue factor for immunotherapy of choroidal neovascularization by intravitreal delivery of factor VII-Fc chimeric antibody. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2007;15:3–10. doi: 10.1080/09273940601147760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Hooghe TM, Kyama CM, Chai D, Fassbender A, Vodolazkaia A, Bokor A, Mwenda JM. Nonhuman primate models for translational research in endometriosis. Reprod Sci. 2009;16:152–161. doi: 10.1177/1933719108322430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenken RS. Delayed diagnosis of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:1305–1306. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.07.1491. discussion 1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadfield R, Mardon H, Barlow D, Kennedy S. Delay in the diagnosis of endometriosis: a survey of women from the USA and the UK. Human Reprod. 1996;11:878–880. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a019270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihalyi A, Simsa P, Mutinda KC, Meuleman C, Mwenda JM, D'Hooghe TM. Emerging drugs in endometriosis. Expert Opin Emerging Drugs. 2006;11:503–524. doi: 10.1517/14728214.11.3.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y, Borgstrom P, Maynard J, Koziol J, Hu Z, Garen A, Deisseroth A. Mapping of angiogenic markers for targeting of vectors to tumor vascular endothelial cells. Cancer Gene Therapy. 2007;14:346–353. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7701030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]