Abstract

Translational fidelity, essential for protein and cell function, requires accurate tRNA aminoacylation. Purified aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases exhibit a fidelity of 1 error per 10,000 to 100,000 couplings 1, 2. The accuracy of tRNA aminoacylation in vivo is uncertain, however, and might be considerably lower 3–6. Here, we show that in mammalian cells, approximately 1% of methionine (Met) residues used in protein synthesis are aminoacylated to non-methionyl-tRNAs. Remarkably, Met-misacylation increases up to 10-fold upon exposing cells to live or non-infectious viruses, toll-like receptor ligands, or chemically induced oxidative stress. Met is misacylated to specific non-methionyl-tRNA families, and these Met-misacylated tRNAs are used in translation. Met-misacylation is blocked by an inhibitor of cellular oxidases, implicating reactive oxygen species (ROS) as the misacylation trigger. Among six amino acids tested, tRNA misacylation occurs exclusively with Met. As Met residues are known to protect proteins against ROS-mediated damage 7, we propose that Met-misacylation functions adaptively to increase Met incorporation into proteins to protect cells against oxidative stress. In demonstrating an unexpected conditional aspect of decoding mRNA, our findings illustrate the importance of considering alternative iterations of the genetic code.

Due to the central importance of tRNA aminoacylation and translational accuracy in understanding the biology of mammalian cells under normal and pathological conditions, we devised a method to measure tRNA misacylation in cells. Our method combines pulse radiolabeling of cells with [35S]-Met with microarrays developed for measuring tRNA abundance 8 (Figs. 1A, S1, S2). We hybridized total tRNA to arrays that detect the 274 distinct chromosomal human tRNA species as closely related members of 42 families and all 22 mitochondrial tRNAs, and phosphorimaged to visualize and quantitate 35S-Met-tRNAs hybridized to the array.

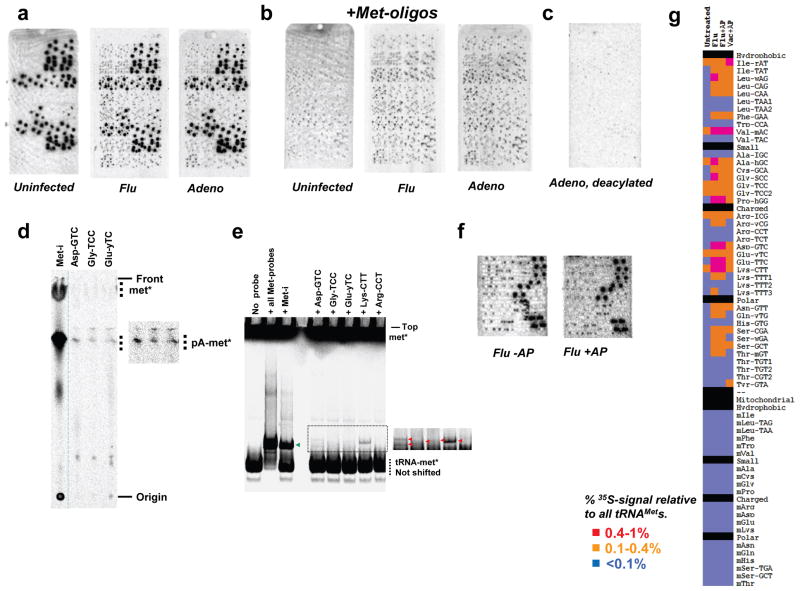

Fig. 1. Induction of tRNA misacylation by viruses.

(a) Microarrays showing total tRNAs isolated from uninfected, flu and Adeno virus infected HeLa cells. (b) Large excess of oligonucleotides complementary to tRNAMets was included in array hybridization. (c) The Adeno-infected sample was deacylated before array hybridization. (d) Thin-layer chromatography of the Flu-infected sample using biotinylated oligonucleotide probes (longer exposure in inset). (e) Non-denaturing acid gel detection of misacylated tRNAs in the Flu-infected sample. (f) Flu-infected sample plus/minus aminopeptidase. (g) Quantitative comparison of uninfected and virus-infected samples. tRNAs are grouped according to amino acid properties. The detection limit of misacylation was ~0.1% for each probe.

For HeLa cells, we detected intense radioactive spots representing five different methionyl-tRNA (tRNAMet) probes, as expected. Unexpectedly, we easily detected less intense radioactive spots representing several non-tRNAMet probes. Further, when we infected HeLa cells with influenza A virus (“Flu”) or adenovirus 5 (“Adeno”) prior to pulse radiolabeling, the level of radioactive signals from non-tRNAMet probes greatly increased (Fig. 1A), and could be exclusively detected by adding excess Met-oligo probes to block hybridization of tRNAMet (Figs. 1B, S3). We employed multiple approaches to conclusively establish that radioactivity emanating from non-cognate tRNA probes derives from aminoacylated [35S]-Met and not other [35S]-containing material (detailed in Methods and Supplemental Information). We ruled out radiolabeling of tRNAs with thio-modifications via catabolism of [35S]-Met (Figs. 1C, S4). We validated [35S]-Met-misacylation using two non-array based methods for several tRNA species (Figs. 1D,E, S5). To distinguish aminoacyl- from peptidyl-tRNAs, we treated total RNA with aminopeptidase M prior to array hybridization to remove N-terminal 35S-Met residues from peptidyl-tRNAs (Figs. 1F, S6). We also ruled out misacylation resulting from contaminants in the 35S-Met preparation (Fig. S7).

In uninfected cells, the 8 cytosolic misacylated tRNA families totaled ~1.5% of the cumulative radioactivity of all five tRNAMet families. Upon Flu infection, misacylation increased in 3 of the 8 species and appeared in 18 new tRNA families. Remarkably, the cumulative radioactivity on non-tRNAMet species totaled ~13% of that of all tRNAMet families (Figs. 1G, S8). Cells infected with Adeno or vaccinia virus (Vac) demonstrated a similar pattern and degree of misacylation. Increased Met-misacylation in virus-infected cells is not an artifact of increased tRNA expression, as increased misacylation does not correlate with the minor changes in tRNA abundance induced by viral infection (Fig. S9). Under all conditions tested, we failed to detect misacylation of any mitochondrial tRNA, demonstrating the selectivity of misacylation for cytosolic tRNAs (Fig. 1).

We next demonstrated tRNA-Met-misacylation in vitro (Figs. S10, S11). HeLa cell derived-methionyl-tRNA synthetase (MetRS) migrates in two major sucrose gradient fractions; one containing the 11-protein multisynthetase complex, the other containing the multi-synthetase complex associated with polysomes 9. Each sedimenting form of the multisynthetase complex demonstrated similar acylation activity with [35S]-Met. The polysome-associated form clearly mediated misacylation among a subset of the misacylated tRNA families identified in vivo. The free form of the multisynthetase complex exhibited less misacylation activity, demonstrating that the fidelity of tRNA synthetases can depend on the higher order structure of the AARS. Further, we showed that while the multisynthetase complex misacylated tRNALys isoacceptors, free LysRS did not (Fig. S11). This is consistent with misacylation being performed by MetRS within the multi-RS complex.

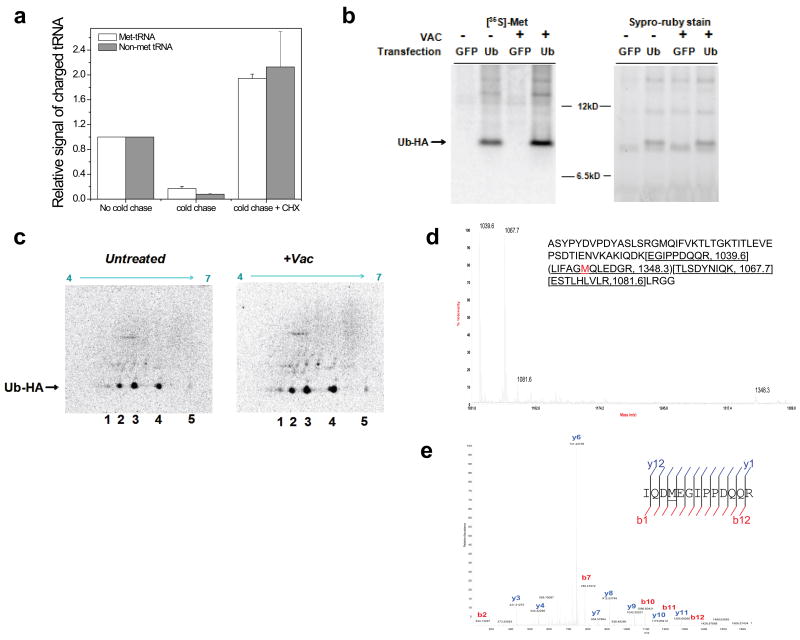

Since aminoacylated tRNAs can be used for non-translation functions 10, 11, it was critical to establish whether Met-misacylated tRNAs are used in translation. A pulse-chase experiment revealed that cognate and non-cognate tRNAs demonstrate a similar off-rate for [35S]-Met after a 3 min chase period with excess unlabelled Met (Fig. 2A). Blocking translation by incubating cells with cycloheximide during the cold Met chase prevented the loss of [35S]-Met from cognate and non-cognate tRNAs in parallel (Figs. 2A, S12A,B). These findings strongly support global use of misacylated tRNAs in protein synthesis. Next, we quantitated the incorporation of [35S]-Met into HA-epitope tagged ubiquitin (Ub-HA), selected as a reporter because it possesses a single Met residue. Infecting cells with Vac increased the specific activity of Ub (dpm/μg protein) by ~1.8 fold, consistent with Vac induced increase in tRNA misacylation (Fig. 2B). 2D gel electrophoresis demonstrated Vac induced alterations consistent with translational utilization of misacylated tRNAs (Fig. 2C). Mass spectrometry detected Ub peptides containing Lys-to-Met substitutions, confirming the translation of misacylated tRNALys(CTT) as predicted from the array data (Fig. 2D,E).

Fig. 2. Misacylated tRNAs are used in translation.

(a) Correctly acylated and misacylated tRNAs have the same kinetic properties plus/minus cycloheximide (CHX). Error bars represent s.d. (n=4). (b) 1D SDS-PAGE showing an increase in specific activity of [35S]-Met incorporation upon Vac infection. (c) 2D SDS-PAGE of uninfected and Vac-infected samples. Spot 3 (55–62% of all radioactivity) matches the expected pI of wild-type Ub-HA. Spots 1 and 5 correspond to Lys/Arg-to-Met and Glu/Asp-to-Met substitution, respectively. (d) MALDI-TOF of tryptic digested Ub-HA. Peaks are labeled with their m/z values from the Ub-HA sequence. (e) MS-MS sequencing of 763.87 (m/2z) mass peak by LC-FTMS of tryptic digested Ub-HA.

We detected virus-induced increases in misacylation (Fig. S13) and global utilization of Met-misacylated tRNAs in protein synthesis (Fig. S14) even when viral infectivity was inactivated by UV irradiation. Exposing HeLa cells, which express all human TLRs 12, to the TLR3 ligand poly-inosine-cytosine (poly-IC, which mimics double stranded viral RNA), or the TLR4 ligand lipopolysaccharide (LPS, derived from bacterial cell walls) also increased tRNA misacylation (Figs. 3A, S15A). LPS- and poly-IC-induced misacylation patterns overlapped significantly with each other and with virus-induced misacylation. We obtained similar results with CpG oligonucleotides, a TLR9 ligand (data not shown). Not all immune signaling events increase [35S]-Met-misacylation in HeLa cells, however. Exposing cells to interferon-β or interferon-γ did not increase misacylation, although each cytokine altered the expression of cytoplasmic and mitochondrial tRNAs within 24h of initial exposure (data not shown).

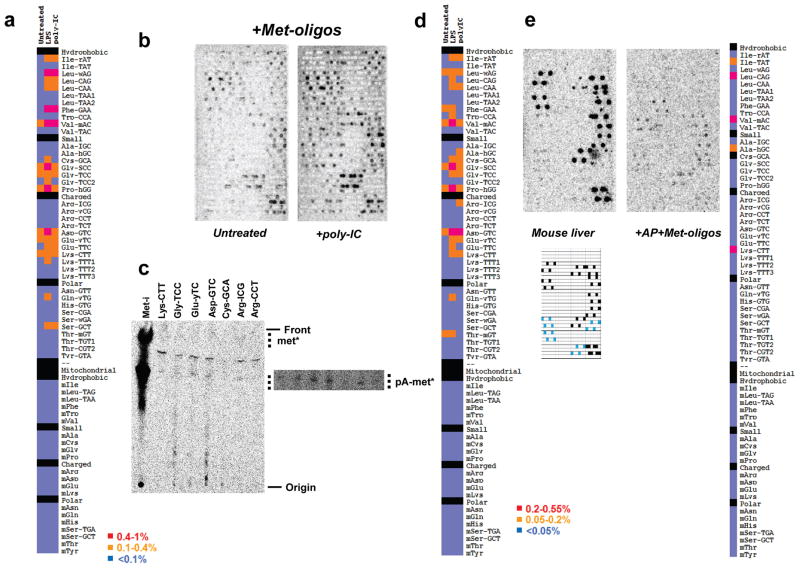

Fig. 3. tRNA misacylation induced by TLR ligands.

(a) Comparison of untreated and LPS, poly-IC-treated HeLa samples. (b) Comparison of immature and poly-IC-matured Bone Marrow Dentritic Cells (DC) including complementary Met-oligos in array hybridization. (c) Thin-layer chromatography of the poly-IC matured sample using biotinylated probes. (d) Quantitative comparison of untreated, LPS and poly-IC-matured DC samples, all AP-treated. The detection limit of tRNA misacylation for these samples was ~0.05% for each probe. (e) Misacylation occurs in vivo. Misacylation for total charged tRNA isolated from mouse liver after 1 min pulse with 35S-Met. Array key shows probe locations for Met-tRNAs (black) and Cys-tRNAs (blue).

We extended these findings to mouse bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (DCs, Figs. 3B-D, S15B), and liver cells in a living mouse by injecting [35S]-Met into the portal vein (Fig. 3E). Both cell types demonstrated a level and pattern of tRNA misacylation similar to HeLa cells, firmly establishing the in vivo relevance of misacylation. We failed to detect misacylation after labeling cells with either [35S]-Cys or 3H-labeled Ile, Phe, Val, or Tyr (Fig. S16, note that specific activities of other commercially available amino acids are too low to detect misacylation at greater than 0.5%). Thus, misacylation could well be limited to Met.

As viral and bacterial infections activate myriad stress response pathways in cells, we examined the ability of chemical or physical stressors to modulate misacylation. We incubated HeLa cells at 42°C, or exposed them to the Asn-linked glycosylation inhibitor tunicamycin or the proteasome inhibitor MG132, treatments that induce an unfolded protein response via distinct pathways 13. While tunicamycin and MG132 increased tRNA misacylation by ~2-fold, heat shock decreased tRNA misacylation by ~2-fold (Fig. S17). The pattern of misacylation induced by tunicamycin and MG132 was limited to subset of RNA families seen in response to viruses and TLR ligands. Allowing HeLa cells to grow past confluence, a condition known to induce stress related genes 14, also induced misacylation (Fig. S16B).

Heightened generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by activation of NADPH oxidases is a common downstream effect of many cellular stressors 13. It is well established that genetically encoded Met residues can act in cis to protect enzyme active sites against ROS-mediated damage 15, and Met protects E. coli against oxidative damage-induced death 7. ROS oxidize the highly reactive sulfur in Met which is restored to its reduced state by Met-sulfoxide reductases through NADPH oxidation 16. We hypothesized that tRNA Met-misacylation protects cells against oxidative stress by replacing the amino acids we identify in the arrays with Met. Because tRNA misacylation is induced rapidly, this mechanism allows immediate extra-genetic incorporation of Met residues in newly synthesized proteins that provide protection against increased ROS levels.

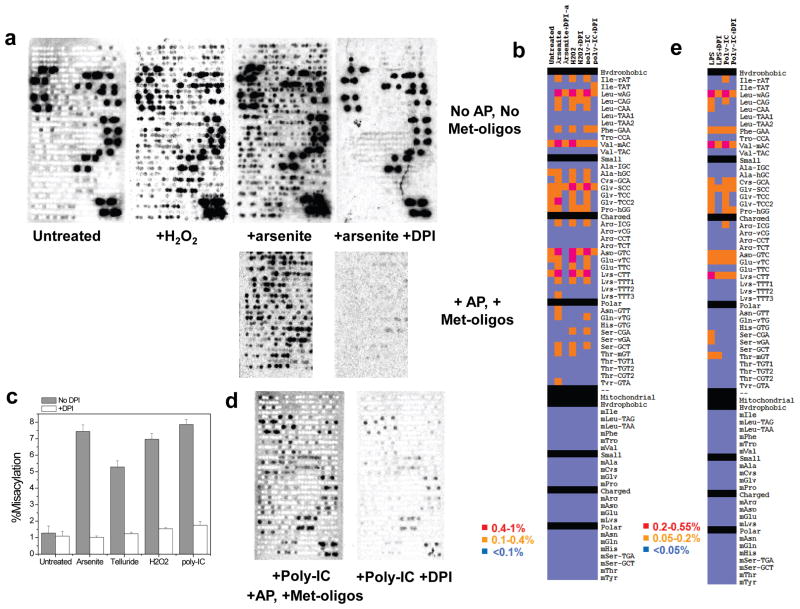

As predicted by this hypothesis, exposing HeLa cells to ROS-inducing agents (arsenite, telluride, or H2O2) induces Met-misacylation at high levels (Figs. 4A,B, S18A,B). Arsenite-induced misacylation did not require protein synthesis, as it was unaffected by the addition of CHX at the time of arsenite exposure (Fig. S12C). Oxidizing agents act at least in part by increasing cellular NADPH oxidase activity 17, and in each case, misacylation was significantly reduced by diphenyleneiodonium (DPI), a broad inhibitor of these oxidases. TLR activation is known to induce ROS in neutrophils and DCs 18. Remarkably, treating HeLa cells with DPI inhibited poly-IC induced misacylation, implicating ROS as the trigger for TLR-induced misacylation (Figs. 4B,C, S18C). DPI also inhibited LPS and poly-IC induced misacylation in DCs (Fig. 4D,E).

Fig. 4. Oxidative stress induces NADPH oxidase (NOX)-dependent RNA misacylation.

(a) tRNA misacylation in HeLa cells induced by oxidizing agents H2O2 (1h) or arsenite (4h). DPI inhibits aresenite-induced misacylation. (b) Quantitative comparison of tRNA misacylation under oxidative stresses (Arsenite and H2O2) and TLR ligand (poly-IC) plus/minus DPI. (c) Percent of all misacylated tRNAs plus/minus DPI when cells were treated under four conditions (100% = all Met-tRNAs). Error bars represent s.d. (n=2). (d) poly-IC induces NOX-dependent RNA misacylation in DC cells. (e) Quantitative comparison of tRNA misacylation in DC cells plus/minus DPI.

We propose that Met-misacylation is a protective response to cellular stressors that increase levels of ROS. This is consistent with the recent proposal that the ROS scavenging capacity of Met selects for mitochondrial genetic recoding of AUA from Ile to Met 19. Alternative explanations for Met-misacylation include the possibilities that Met-misacylation is a non-productive byproduct of oxidative stress that exacerbates stress by decreasing translational fidelity (particularly since replacement of charged surface residues with Met would be predicted to increase protein aggregation), and that misacylated Met tRNAs function in cellular methylation or amino acid transport pathways 20.

It has been demonstrated that upon mutating aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases or introducing exogenous misacylating tRNAs, E. coli, yeast, and mice tolerate and adapt to increased errors in tRNA aminoacylation 3, 21, 22. Theoretical considerations 23 support higher error thresholds for translational fidelity than those observed for tRNA aminoacylation in vitro. We demonstrate that mammalian cells have an intrinsic ability to modify tRNA misacylation and translational fidelity. The extent to which this ability, currently limited to Met, extends to any of the 14 amino acids yet to be examined, is an open question.

In summary, we have shown that tRNA misacylation with Met is a common and regulated event in mammalian cells. Although the full implications of this phenomenon remain to be explored, there is a practical bottom line: decoding mRNA into protein in living cells is not as simple as generally believed. tRNA misacylation-based protein sequence diversity, like RNA splicing and post-translational modifications, may represent an evolutionary strategy for expanding and manipulating the information encoded by nucleic acids 24.

Methods summary

Detailed methods section includes cell growth, cell treatment and stress conditions, misacylation in vivo, immune-precipitation of Ub-HA, 2D PAGE and mass spectrometry; detection of tRNA misacylation by TLC and native acid gels, pH 9 deacylation, nuclease treatment of arrays, in vitro aminoacylation and acylated tRNA extraction for microarrays.

Microarray

The basic features of the tRNA microarray have been described previously to determine tissue-specific differences in human tRNA expression 8. Both array versions contain ~50 probes (42 unique) for chromosomal human and mouse tRNAs, 22 probes for human mitochondrial tRNAs, and 18 probes for mouse mitochondrial tRNAs. The first array version contains 20 repeats for each probe, and over 50 hybridization control probes for tRNAs from bacteria, yeast, Drosophila and C. elegans. The second array version contains 8 repeats for each probe and 6 hybridization controls for tRNAs from bacteria and yeast. The second version contains fewer repeats per probe but has higher sensitivity due to improved array printing techniques. Both versions contain 4 probes for chromosomal initiator and elongator tRNAMet and one for mitochondrial tRNAMet.

Array hybridization was performed on a Genomic Solutions Hyb4 station with 10μg total RNA in 2xSSC, pH4.8 at 60°C for 50min. This short hybridization time was the same as the half-life of [35S]-Met labeled aminoacylated tRNAs (Fig. S19) and was necessary to minimize the amount of hydrolysis of aminoacylated tRNA during hybridization. After hybridization, arrays were washed twice each, first in 2xSSC, pH4.8, 0.1%SDS, then in 0.1xSSC, pH4.8, spun dry, and exposed to phosphorimaging plates (Fuji Medicals) for up to 14 (35S-labels) or 34 days (3H-labels using 3H-plates). Spot intensity was quantified using the Fuji Imager software.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dennis Klinman (NCI, Frederick, MD) for his generous gift of CpG oligonucleotides and advice, Alex Schilling (UIC, Chicago, IL) for supervision and advice on mass spectrometry experiments, Chris Nicchitta (Duke University, Durham, NC), Theodore Pierson (NIAID, Bethesda, MD) and Philippe Cluzel (Harvard University, Cambridge, MA) for insight and advice. This work was supported by the Division of Intramural Research, NIAID and by NIH extramural pilot projects.

References

- 1.Ibba M, Soll D. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthesis. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:617–650. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cochella L, Green R. Fidelity in protein synthesis. Curr Biol. 2005;15:R536–540. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee JW, et al. Editing-defective tRNA synthetase causes protein misfolding and neurodegeneration. Nature. 2006;443:50–55. doi: 10.1038/nature05096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miranda I, Silva R, Santos MA. Evolution of the genetic code in yeasts. Yeast. 2006;23:203–213. doi: 10.1002/yea.1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silva RM, et al. Critical roles for a genetic code alteration in the evolution of the genus Candida. EMBO J. 2007;26:4555–4565. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahel I, Korencic D, Ibba M, Soll D. Trans-editing of mischarged tRNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:15422–15427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2136934100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luo S, Levine RL. Methionine in proteins defends against oxidative stress. FASEB J. 2009;23:464–472. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-118414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dittmar KA, Goodenbour JM, Pan T. Tissue-specific differences in human transfer RNA expression. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e221. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ussery MA, Tanaka WK, Hardesty B. Subcellular distribution of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases in various eukaryotic cells. Eur J Biochem. 1977;72:491–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1977.tb11272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Varshavsky A. Regulated protein degradation. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:283–286. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ibba M, Soll D. Quality control mechanisms during translation. Science. 1999;286:1893–1897. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5446.1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nishimura M, Naito S. Tissue-specific mRNA expression profiles of human toll-like receptors and related genes. Biol Pharm Bull. 2005;28:886–892. doi: 10.1248/bpb.28.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malhotra JD, et al. Antioxidants reduce endoplasmic reticulum stress and improve protein secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:18525–18530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809677105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murray JI, et al. Diverse and specific gene expression responses to stresses in cultured human cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:2361–2374. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-11-0799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levine RL, Mosoni L, Berlett BS, Stadtman ER. Methionine residues as endogenous antioxidants in proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:15036–15040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oien DB, Moskovitz J. Substrates of the methionine sulfoxide reductase system and their physiological relevance. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2008;80:93–133. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(07)80003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chernyak BV, et al. Production of reactive oxygen species in mitochondria of HeLa cells under oxidative stress. BBA- Bioenergetics. 2006;1757:525–534. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Savina A, et al. NOX2 controls phagosomal pH to regulate antigen processing during crosspresentation by dendritic cells. Cell. 2006;126:205–218. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bender A, Hajieva P, Moosmann B. Adaptive antioxidant methionine accumulation in respiratory chain complexes explains the use of a deviant genetic code in mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:16496–16501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802779105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finkelstein JD. Metabolic regulatory properties of S-adenosylmethionine and S-adenosylhomocysteine. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2007;45:1694–1699. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2007.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruan B, et al. Quality control despite mistranslation caused by an ambiguous genetic code. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:16502–16507. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809179105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santos MA, Cheesman C, Costa V, Moradas-Ferreira P, Tuite MF. Selective advantages created by codon ambiguity allowed for the evolution of an alternative genetic code in Candida spp. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:937–947. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoffmann GW. On the origin of the genetic code and the stability of the translation apparatus. J Mol Biol. 1974;86:349–362. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(74)90024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freist W, Sternbach H, Pardowitz I, Cramer F. Accuracy of protein biosynthesis: quasi-species nature of proteins and possibility of error catastrophes. J Theor Biol. 1998;193:19–38. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.1998.0672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.