Abstract

Background

Testing technologies are increasingly used to target cancer therapies. Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) testing to target trastuzumab for patients with breast cancer provides insights into the evidence needed for emerging testing technologies.

Methods

We reviewed literature on HER2 test utilization and cost-effectiveness of HER2 testing for patients with breast cancer. We examined available evidence on: percentage of eligible patients tested for HER2; test methods used; concordance of test results between community and central/reference laboratories; use of trastuzumab by HER2 test result; and cost-effectiveness of testing strategies.

Results

Little evidence is available to determine whether all eligible patients are tested; how many are retested to confirm results; and how many with negative HER2 test results still receive trastuzumab. Studies suggest that up to 66% of eligible patients had no documentation of testing in claims records; up to 20% of patients receiving trastuzumab were not tested or had no documentation of a positive test; and 20% of HER2 results may be incorrect. Few cost-effectiveness analyses of trastuzumab explicitly considered the economic implications of various testing strategies.

Conclusions

There is little information about the actual use of HER2 testing in clinical practice, but evidence suggests important variations in testing practices and key gaps in knowledge exist. Given the increasing use of targeted therapies, it is critical to build an evidence base that supports informed decision-making on emerging testing technologies in cancer care.

Keywords: personalized medicine, targeted therapies, genomics, HER2, trastuzumab, breast cancer, utilization, cost-effectiveness, clinical practice patterns

Introduction

Testing technologies have emerged as important components of healthcare and are accelerating rapidly for cancer therapies. There are already several well known examples of the use of testing and molecular targeted therapies with more such therapeutics in the pipeline.1 These new testing technologies are essential ingredients in a shift towards personalized medicine (healthcare targeting medical interventions to patients based on their individual characteristics, particularly their genetics) and there is hope that they can improve health outcomes and reduce expenditures. A critical challenge to the implementation of targeted therapies in oncology is determining whether and how they will be provided to the individuals who will benefit most from them.

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) testing to target trastuzumab treatment (Herceptin®, Genentech, Inc., South San Francisco, CA) for patients with breast cancer provides an instructive case study to inform discussion of the use of emerging testing technologies in clinical practice. HER2 testing was developed to determine which patients have breast cancers that overexpress the gene HER2; and for those 20%–30% of patients, treatment with trastuzumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody, proved to be highly effective. Without the ability to target the drug to this specific population, the drug would not have been approved.2 HER2 testing is a well-known example of the successful use of testing to target cancer treatment that has been used in clinical practice for over 10 years. Trastuzumab and an accompanying test were approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1998 for use in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Their use was expanded to patients with early-stage breast cancer after 2005 and testing is now recommended for all patients with invasive breast cancer.

Our objective was to examine what is known about the utilization and cost-effectiveness of HER2 testing in clinical practice in the United States (US). We restricted our examination to testing practices in the US because practice patterns are likely influenced by healthcare coverage and reimbursement policies, which vary substantially across countries.3

Despite the clinical success of trastuzumab, there is growing debate among patients, providers, and payers regarding the best methods for selecting patients for treatment based on HER2 test results. In particular, there is uncertainty regarding the most appropriate and efficient testing strategy and concerns about the reliability and interpretation of test results. This study provides an in-depth analysis and illustration of the broader issue of evidence gaps for new testing technologies 4 and the issues emerging because of an increased emphasis on the need to translate basic science findings into clinical therapies and health benefits.5, 6

Description of HER2 Testing

The FDA has approved three types of tests to assess HER2 status in breast tissue: immunohistochemistry (IHC), fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and most recently chromogenic in situ hybridization (CISH). There are several commercially available test kits for both the IHC and FISH tests with different performance characteristics, and there is no consensus about what are the optimal methods. Current guidelines from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and the College of American Pathologists (CAP) 7 and from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) 8 recommend using either IHC (with confirmation of indeterminate results by FISH) or FISH to determine HER2 status. Although FISH has been shown to be a better predictor of response to treatment, IHC is approximately one quarter to one third the cost of FISH and is more easily performed in community laboratories.7 Current guidelines state that a tumor with an IHC score of 3+, an average HER2 gene:chromosome 17 ratio of greater than 2.2 by FISH, or an average number of HER2 gene copies per cell of 6 or greater is considered HER2 positive. A tumor with an IHC score of 2+ should be further tested using FISH, with HER2 status determined by the FISH result, although there is debate over the benefit of trastuzumab in patients with indeterminate FISH results.7 Testing decisions have recently become even more complex because of preliminary reports that women with test results that are negative based on recommended thresholds may actually benefit from trastuzumab.9 Thus, methods of evaluating eligibility for trastuzumab are still in flux.

Framework for Evaluating the Use and Cost-Effectiveness of Testing

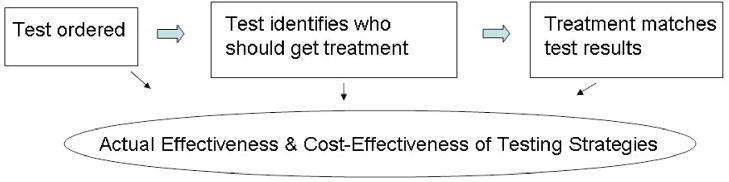

The effectiveness and efficiency of diagnostic testing in actual practice is based on a sequence of events: (1) a test is ordered; (2) test results are reviewed and interpreted to assess whether a patient is likely to benefit from a specific therapy; and (3) treatment is offered and accepted or declined in accordance with test results (Figure 1). Variation in these factors influences the actual effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of testing and treatment.

Figure 1.

Sequence of Events for Diagnostic Testing.

Research Questions

1. Percentage of eligible patients tested for HER2 and methods used

Although there is clinical consensus that all patients with invasive breast cancer should be tested, some patients may not receive testing. In some cases patients may be tested, but their test results may not be properly documented.

We examined available evidence addressing the following questions:

Do all patients with invasive breast cancer receive HER2 testing?

Does test utilization vary according to personal characteristics, such as insurance status, socioeconomic status, and race/ethnicity, or by physician, health plan, or geographic characteristics?

We considered that patients may be tested by using IHC, FISH, or both methods but did not examine CISH because it has only recently been an FDA-approved option for clinical practice. Although there is no consensus about whether IHC or FISH should be used for initial testing, there is agreement that patients with indeterminate IHC results (approximately 15% of patients 7) should have a FISH test. However, some patients with indeterminate IHC results may not get confirmatory testing and there is continuing debate over the cut-off used. We examined available evidence addressing the following questions:

What percentage of patients receives IHC, FISH, or both tests?

Do patients with indeterminate IHC results get confirmatory FISH testing?

Does the use of IHC or FISH vary by personal characteristics, such as insurance status, socioeconomic status, and race/ethnicity, or by physician, health plan, or geographic characteristics?

2. Percentage of tests with concordant results between community and central or reference laboratories

Even if positivity criteria can be determined so that only patients defined as having positive HER2 results are those who will benefit from trastuzumab, HER2 test performance in actual practice will be influenced by variability in laboratory procedures. Because the purpose of this study is to examine actual testing practices, our literature review focused on laboratory concordance rather than predetermined thresholds for determining positive results. We examined available evidence addressing the following question:

What is the concordance between HER2 tests performed in community laboratories as compared to central or reference laboratories?

3. Percentage of patients who receive trastuzumab

Although clinical guidelines state that only patients testing HER2 positive according to established algorithms should receive trastuzumab, patients who either are not tested or have negative results may still receive trastuzumab because of doubts about test accuracy, clinical factors, personal or healthcare system factors, or human error. Patients with positive HER2 test results may not receive trastuzumab because of the same factors. We examined available evidence addressing the following questions:

What is the percentage of patients with positive, negative, or no test results who receive trastuzumab?

Does the use of trastuzumab (conditional on test results) vary by personal characteristics such as insurance status, socioeconomic status, and race/ethnicity, or by physician, health plan, or geographic characteristics?

4. Cost-effectiveness of HER2 testing in clinical practice

Studies that have examined the cost-effectiveness of trastuzumab in a population of patients already identified as HER2 positive have found that adding it to chemotherapy is relatively cost-effective.10–12. These studies, however, do not address the cost-effectiveness of different HER2 testing strategies in the adjuvant setting. For example, if patients who would benefit from treatment are not tested, if the most efficient testing algorithm is not used, if tests are inaccurate, or if patients receive treatment that is inappropriate based on their test results, then the cost-effectiveness of testing and treatment in actual practice will be lower than the estimated cost-effectiveness. We examined the available evidence on the following question:

What is the cost-effectiveness of HER2 testing strategies?

Literature Review

We conducted an extensive search to identify evidence on the HER2 testing practice patterns just described. To obtain data on actual use, we searched electronic databases, performed hand searches of relevant publications, did Internet searches, and reviewed key guidelines. Because much of this evidence is not in peer-reviewed publications due to its recency, we also included newspaper articles, abstracts, guidelines, and industry reports. To obtain data on cost-effectiveness, we conducted a systematic search for cost-effectiveness analyses of HER2 testing by using electronic databases and hand searching of relevant publications. For all searches, we included English-language publications through May 2008. Details of the search are provided in the Appendix.

Results

Evidence regarding testing practice patterns is summarized in Table 1 and described below.

Table 1.

HER2 Testing Practice Patterns*

| Research Questions | Summary of Evidence |

|---|---|

| Percentage of patients tested for HER2 |

|

| Percentage of patients tested by using IHC and/or FISH methods |

|

| Percentage of tests with concordant results between community and central or reference labs |

|

| Percentage of patients testing positive or negative who received trastuzumab |

|

Abbreviations to the table: HER2: human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; IHC: immunohistochemistry; FISH: fluorescence in situ hybridization

Percentage of eligible patients tested for HER2

Stark et al (2004), in a study of patients with metastatic breast cancer in the Henry Ford Health Care System (MI) shortly after the FDA approval of trastuzumab for patients with metastatic breast cancer (1999–2000), found that 52% were tested for HER2.13 Women with an absence of estrogen receptors, those with physicians in the surgery specialties, and those who had capitated insurance were more likely to be tested. A study of a 5% sample of Medicare enrollees in 2005 (N=6588) – reported only in abstract form – showed that 32% of patients newly diagnosed with invasive breast cancer had documentation in claims data of having undergone a HER2 test.14 Of those with documentation of having received trastuzumab, 68% had documentation of having had a HER2 test. Among those receiving trastuzumab, older women and white women were more likely to have been tested.

Percentage of patients tested using IHC and/or FISH methods

The study noted above in the Medicare population also showed that 93% of the women tested received only IHC, 0.3% received only FISH, and 6% received both tests – although it is not known whether FISH was used for initial or confirmatory testing.14

Percentage of tests with concordant results between community and central or reference laboratories

We found no studies of laboratory concordance in routine practice, although several studies have examined concordance in conjunction with enrollment into clinical trials and they can be presumed to reflect routine practice in general.15–18 The ASCO/CAP guidelines reviewed such studies and found that approximately 20% of IHC tests done by local, community-based laboratories are inaccurate when compared to central or reference laboratory results.7

Percentage of patients testing positive or negative who received trastuzumab

One study of patients with early-stage or metastatic breast cancer in a privately insured population was conducted by using 2005 United HealthCare data (personal communication, Lee Newcomer, 7/18/08).19, 20 They found that at least 12% and “probably” 20% of women receiving trastuzumab either did not have a HER2 test or had a test that showed no conclusive evidence of HER2 overexpression. More specifically, it was estimated that 8% were underexpressed, 4% had not been tested, and 8% were unknown because the physician did not provide the record. Details of this study have not been published in the peer-reviewed literature.

Cost-effectiveness of HER2 testing in clinical practice

Of 621 studies screened, we found four cost-effectiveness analyses of HER2 testing or trastuzumab treatment in US populations.10–12, 21 Two of these studies did not consider HER2 testing and examined only treatment strategies, assuming that the patients had already been tested.11, 12 Another study included testing in their model but did not compare different testing strategies.10 One study examined HER2 testing strategies in a US population by analyzing seven possible test-treat strategies for patients with metastatic breast cancer.21 We did not find any analyses that examined testing strategies in the adjuvant setting.

Discussion

Summary and Implications for HER2 Testing

There is little evidence about the use of HER2 testing in routine clinical practice that can inform the current debate about selection of patients for treatment or the relative advantages and disadvantages of alternative testing strategies. The limited evidence available suggests that there are important variations in testing practices and key gaps in knowledge about those practices.

This study illustrates the gaps in what is known and the weaknesses in available evidence. Studies are generally of selected populations, use outdated data, and often are not published in peer-reviewed journals.

Understanding the use of HER2 testing in cancer care is important because of its critical role in targeting therapy. Withholding trastuzumab from a patient with HER2-positive breast cancer (underuse) or giving trastuzumab to a patient with HER2-negative breast cancer (overuse) will result in suboptimal outcomes. In the former situation, patients may not benefit from the substantial reduction in the risk of death from breast cancer conferred by trastuzumab.22 In the latter situation, patients who will not benefit from treatment are exposed to an unnecessary risk of heart failure and the healthcare system incurs unnecessary costs of about $100,000 annually for trastuzumab.7

Our results do not challenge the efficacy of HER2 testing and trastuzumab treatment – rather, they suggest a need to collect data on the utilization of tests and treatment, and incorporate this information into rigorous analyses of best testing practices. It appears that some clinicians and payers assume that all eligible patients are being tested, that tests are accurate, and only patients with positive test results are receiving trastuzumab. Our review suggests that gaps in the literature are substantial, and that these important assumptions cannot yet be verified. Although it is likely that testing has improved over time, this study demonstrates that even if one assumes that these problems are no longer issues, the paradigm outlined by HER2 and trastuzumab is likely to be repeated over and over as new targeted therapies are developed. If we don’t understand the mistakes that were made as this test/treatment combination were introduced then we are likely to repeat them.

Testing is now recommended for all invasive breast cancers, but no studies examine how utilization has changed since 2005, when testing indications were expanded to include women with early-stage breast cancers. It is particularly concerning that there are no studies of testing among typically underserved patients, including the uninsured, Medicaid insured, and minorities.

Little is known about how many patients receive one or both of the tests currently recommended and to what extent those patients are retested to confirm the results. As guidelines recommend using either IHC or FISH, it is important to know which method is used and how that usage varies by patient, provider, and healthcare system factors. In addition, considering the substantial percentage of patients who have indeterminate IHC results that require FISH testing for confirmation, it is important to know whether those patients actually get confirmatory testing. It is not known how the introduction of a third FDA-approved test (CISH) will improve or further widen the gap of evidence on tests used.

In contrast to the lack of evidence for our other research questions, there is more solid evidence to suggest that a substantial percentage of HER2 tests performed by community laboratories are inaccurate, based on comparisons with higher-volume central or reference laboratories. The available studies may not be representative of routine practice, however, because they were conducted as a part of clinical trials and may therefore underestimate the extent of problems with test accuracy. Although there may be times when community labs have more accurate results, e.g. if the lesional tissue is small it may no longer be present on samples submitted to the reference lab or if the reference lab mistake DCIS for invasive carcinoma. However, we do not know of any studies that suggest the likelihood a patient will respond to the drug is more consistent with data from community vs. central labs.

Reasons for discordance between laboratory results are complex and include differences in how laboratories perform and interpret tests as well as the lack of consensus about accepted procedures. Several initiatives are being pursued to resolve these issues and standardize laboratory performance and there is increasing scrutiny of in house laboratory (“home brew”) tests; for example, recently developed guidelines recommend that HER2 testing be done in a CAP-accredited laboratory.7 Considering the serious implications of inaccurate tests for patients’ lives and the impact on the healthcare system, it is essential to have more data on test quality and interpretation. As one industry observer noted, “We need more rigorous validation processes. It has been like the wild, wild West out there.” 23

It is also important to note that one study found that up to 20% of women receiving trastuzumab have no documentation of a positive HER2 test and one study found that up to 66% of eligible patients had no documentation of testing in claims records. However, these findings have not been published in detail, are not based on recent data, and do not distinguish between women who were not tested and those who had been tested but were missing documentation of testing or results in claims records. We found similar results in a pilot study of one health plan, and we have a larger and more recent study underway. 24 These findings argue for more standardized test reporting practices, with requirements such as the inclusion of both quantitative and qualitative assessments from pathology reports.

Actual practice patterns may have a substantial impact on the costs and effectiveness of testing and treatment in the adjuvant setting, yet such analyses have not been conducted. Analyses examining the costs and effectiveness of current testing guidelines and how they might vary in actual practice are sorely needed.

Implications

Our findings regarding HER2 testing illustrate both the challenges and opportunities in building an evidence base to support effective and efficient decision-making about emerging testing technologies in cancer care. HER2 testing provides an example of a test that is clinically beneficial but that faces quality and implementation challenges – and such challenges will increasingly become relevant as more new testing technologies and targeted therapies emerge.25, 26 The underlying science and associated guidelines for testing technologies are evolving quickly, and the different new technologies make it harder to ensure that testing is done correctly and the results are interpreted appropriately. HER2 testing, as with many diagnostic tests, does not provide a black and white answer about treatment decisions.

With complex testing scenarios, there is ample room for mistakes and misinterpretation along the entire testing sequence.23 Thus, one solution is greater standardization of test procedures and processes. Communication between the laboratory and the clinician may be of particular importance; for example, in the case of HER2 testing, the speculation is that patients with indeterminate scores are being treated as positive results.23 Decision analytic tools for clinicians could facilitate improved interpretations and communications.

Another solution is increasing the amount of data available on testing technologies. Historically, there have been less data available on diagnostics than on other interventions, such as pharmaceuticals or surgical procedures – a gap that has taken on greater significance as the use of diagnostics to target therapies has accelerated. One major gap is the lack of administrative databases linking testing, test results, treatment, and outcomes. In the case of HER2 testing, claims databases do not typically include information on test results. Moreover, it is often impossible to identify the use of testing in administrative databases because of a lack of billing codes specific to each test or type of test received by a patient. In health insurance claims, the use of IHC and FISH tests for HER2 detection cannot be reliably distinguished from the same types of assays performed for other indications. Although Current Procedural Terminology code modifiers have been developed by the American Medical Association to differentiate specific tests, these modifiers are not commonly used in clinical practice. In addition, test codes may be bundled into a common pathology code that does not permit the identification of individual tests.

Conclusions

The trend toward greater use of testing to target healthcare is inevitable and has the potential to improve the quality and efficiency of healthcare. Our findings should not be construed as reasons for attempting to slow the diffusion of new testing technologies into clinical practice and cancer care or as a critique on oncologists’ treatment decisions. Rather, this case study highlights how and what evidence might be improved to help guide decisions regarding emerging tests and associated therapies in cancer care. Given the rapid growth in this area – for example, there are more than 6,000 articles on gene-disease associations each year and more than 1,300 genetic tests making their way to market – evidence-based information will become a necessity if these new technologies are to be used wisely.27

It is critical to build an evidence base that can support effective and efficient decision-making in regard to emerging testing technologies in clinical practice, considering their impact on clinical care and the healthcare system.28 A comprehensive agenda for translational research is needed to move new discoveries – such as those in human genomics – into health practice in a manner that maximizes health benefits and minimizes harm to individual people and populations.6, 27 This agenda will require increased attention not only to the translation of basic research findings into new therapeutic options, but also to the translation of research into actual practice.5 By examining translational issues, we can improve the effectiveness and efficiency of care, reduce disparities, and ensure that the patients who will most benefit from treatment will get it.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Support/Acknowledgments:

This study was funded by two grants to Dr. Phillips from the National Cancer Institute (R01CA101849 and P01CA130818) and a grant from the Blue Shield Foundation of California (unrestricted). Funding agencies had no review of any portion of this work.

Drs. Phillips and Haas have an unrestricted grant from the Aetna Foundation to examine the utilization of HER2 testing and gene expression profiling for breast cancer.

Dr. Haas has a research grant from Pfizer for unrelated work (on adverse drug event reporting).

We thank i3 innovus, as well as Julia Trosman and the Center for Business Models in Healthcare, for their commissioned reports developed for the Department of Clinical Pharmacy at the University of California-San Francisco. We also thank Mr. Kuo Tong, president and founder of Quorum Consulting in San Francisco, California, for the use of results from his poster presentation given at the 2007 Breast Cancer Symposium.

Appendix: Literature Review Methods

HER2 Testing Practice Patterns

Because information and studies on HER2 testing practice patterns are widely dispersed, we used a wide range of search strategies, including:

Electronic databases: (1) PubMed using combinations of the following MeSH headings: “trastuzumab,” “HER2,” “Immunohistochemistry,” “In Situ Hybridization, Fluorescence,” “Genes, erbB-2,” “Receptor, erbB-2,” “receptor, epidermal growth factor,” “Breast Neoplasms/drug therapy,” “Breast Neoplasms/genetics,” “Antibodies, Monoclonal/therapeutic use” and using the following keywords in varying combinations: HER2, erbB2, trastuzumab, Herceptin, use or utilization. (2) the BIOSIS Previews database using HER2/neu in the chemical/biochemical box and combining the relevant keywords noted above; (3) the International Pharmaceutical Abstracts database using relevant key words, such as trastuzumab and HER2, and (4) the National Cancer Institute Web site (http://www.cancer.gov/cancer_information) using the Web site search box and entering the relevant key words noted above.

Internet searches using the Google Search Engine

Hand searches of widely circulated journals (JAMA, New England Journal of Medicine, Health Services Research, Health Affairs, and Science), abstracts presented at ASCO meetings, and relevant reports

ASCO/CAP and NCCN guidelines

We also reviewed datasets that may contain relevant information in order to assess whether they have been used or could be used to address our research questions. These included administrative claims databases (e.g., Medicare, Medicaid, private payers), health survey databases (e.g., Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, National Health Interview Survey, National Health Care Survey), cancer registries/databases (e.g., Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER), National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Cancer Research Network), and industry information (e.g., Genentech, LabCorp).

Cost-Effectiveness Analyses of HER2 Testing or Treatment

We conducted a systematic search of cost-effectiveness analyses of HER2 testing or treatment by using standard procedures for searching, inclusion, and coding (http://www.cochrane.org/resources/handbook/Handbook4.2.6Sep2006.pdf). We searched the following electronic databases: PubMed, Biosis, Cochrane, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD), EconLit, EMBASE, and Health Economic Evaluations Database (HEED). The search strategy utilized three filters composed of MeSH terms and key words: (1) economic (cost and cost-analysis, health economics, economic evaluation, pharmacoeconomics, cost-effectiveness analysis, cost-benefit analysis, cost-utility analysis), (2) breast cancer (breast tumor, breast carcinoma, breast neoplasm, mammary or breast and [tumor or carcinoma or neoplasm or cancer]), and (3) trastuzumab or HER2 (ERB2 receptor, epidermal growth factor receptor, Herceptin, trastuzumab, HER2/neu) to identify relevant publications. Abstracts from the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium published between 2004 and 2006, as well as technology appraisals produced by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), were searched manually. The reference lists of key topical reviews and retrieved articles were hand searched.

We included all publications that met the following criteria:

The paper detailed original research.

The study was a cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA).29

The analysis evaluated either HER2 testing strategies or trastuzumab treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer (early-stage or metastatic).

The analysis was of a US population.

We excluded abstracts and reports because these provided insufficient information for analysis.

Footnotes

Author Contributions:

Dr. Phillips obtained funding, drafted and revised the manuscript, and provided leadership and supervision in conceptualization and design of the study, acquisition of data, and analysis and interpretation of data.

Drs. Liang and Marshall participated in conceptualization and design of the study, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, supervision, and revisions to the manuscript.

Dr. Haas participated in conceptualization and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of the data, and revisions to the manuscript.

Drs. Elkin, Hassett, and Brock and Ms. Van Bebber participated in design of the study, analysis and interpretation of the data and revisions to the manuscript.

Ms Ferrusi participated in design of the study, acquisition of the data, analysis and interpretation of the data, and revisions to the manuscript.

References

- 1.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [Accessed August 22, 2006];Genetic Tests for Cancer. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/ta/gentests/gentests.pdf#search=%22horizon%20scanning%20genetic%20tests%22.

- 2.Bazell R. Her-2 The Making of Herceptin, a Revolutionary Treatment for Breast Cancer. New York: Random House; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bilous M, Dowsett M, Hanna W, et al. Current perspectives on HER2 testing: a review of national testing guidelines. Mod Pathol. 2003 Feb;16(2):173–182. doi: 10.1097/01.MP.0000052102.90815.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phillips KA. Closing the evidence gap in the use of emerging testing technologies in clinical practice. JAMA. 2008 Dec 3;300(21):2542–2544. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woolf SH. The meaning of translational research and why it matters. JAMA. 2008 Jan 9;299(2):211–213. doi: 10.1001/jama.2007.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guttmacher AE, Collins FS. Realizing the promise of genomics in biomedical research. JAMA. 2005 Sep 21;294(11):1399–1402. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.11.1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolff AC, Hammond ME, Schwartz JN, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(1):118–145. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carlson RW, Moench SJ, Hammond ME, et al. HER2 testing in breast cancer: NCCN Task Force report and recommendations. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2006 Jul;4 Suppl 3:S1–22. quiz S23–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paik S, Kim C, Jeong J. Benefit from adjuvant trastuzumab may not be confined to patients with IHC 3+ and/or FISH-positive tumors: central testing results from NSABP B-31. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2007;25(5s) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garrison LP, Perez EA, Dueck A, Lalla D, Paton V, Lubeck D. Cost-effectiveness analysis of trastuzumab in the adjuvant setting for treatment of HER2+ breast cancer. Cancer. 2007;110(3):489–498. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liberato NL, Marchetti M, Barosi G. Cost effectiveness of adjuvant trastuzumab in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(6):625–633. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.4220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurian AW, Thompson RN, Gaw AF, Arai S, Ortiz R, Garber AM. A cost-effectiveness analysis of adjuvant trastuzumab regimens in early HER2/neu-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(6):634–641. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.3081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stark A, Kucera G, Lu M, Claud S, Griggs J. Influence of health insurance status on inclusion of HER-2/neu testing in the diagnostic workup of breast cancer patients. Int J Qual Health Care. 2004;16(6):517–521. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzh085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tong KB, Chen E, Gregory C, Kim D. HER-2 Testing and Trastuzumab Use in the Medicare Population [abstract #141]. Paper presented at: In: Book and abstracts of the 2007 Breast Cancer Symposium; September 7–8, 2007; San Francisco, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paik S, Bryant J, Tan-Chiu E, et al. Real-world performance of HER2 testing--National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project experience. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002 Jun 5;94(11):852–854. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.11.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roche PC, Suman VJ, Jenkins RB, et al. Concordance between local and central laboratory HER2 testing in the breast intergroup trial N9831. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002 Jun 5;94(11):855–857. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.11.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dressler LG, Berry DA, Broadwater G, et al. Comparison of HER2 status by fluorescence in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry to predict benefit from dose escalation of adjuvant doxorubicin-based therapy in node-positive breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005 Jul 1;23(19):4287–4297. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reddy JC, Reimann JD, Anderson SM, Klein PM. Concordance between central and local laboratory HER2 testing from a community-based clinical study. Clin Breast Cancer. 2006 Jun;7(2):153–157. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2006.n.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Renshaw RN. Outcomes-based Access: What Will it Means for Biologics? Biotechnology Healthcare. 2006 June;:39–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Culliton BJ. Insurers And ‘Targeted Biologics’ For Cancer: A Conversation With Lee N. Newcomer. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008 January 1;27(1):w41–51. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.1.w41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elkin EB, Weinstein MC, Winer EP, Kuntz KM, Schnitt SJ, Weeks JC. HER-2 testing and trastuzumab therapy for metastatic breast cancer: a cost-effectiveness analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(5):854–863. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perez EA, Romond EH, Suman VJ. Updated results of the combined analysis of NCCTG N9831 and NSABP B-31 adjuvant chemotherapy with/without trastuzumab in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2007;25(6s) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allison M. Is personalized medicine finally arriving? Nat Biotechnol. 2008 May;26(5):509–517. doi: 10.1038/nbt0508-509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.i3 innovus. Variation in the Use of HER2 Testing and Herceptin Among Women with Breast Cancer: A Pilot Proposal. 2007 February 23; Unpublished report prepared for UCSF 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Billings PR. Three barriers to innovative diagnostics. Nat Biotechnol. 2006 Aug;24(8):917–918. doi: 10.1038/nbt0806-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garrison LP, Jr, Carlson RJ, Carlson JJ, Kuszler PC, Meckley LM, Veenstra DL. A review of public policy issues in promoting the development and commercialization of pharmacogenomic applications: challenges and implications. Drug Metab Rev. 2008;40(2):377–401. doi: 10.1080/03602530801952500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khoury MJ, Gwinn M, Yoon PW, Dowling N, Moore CA, Bradley L. The continuum of translation research in genomic medicine: how can we accelerate the appropriate integration of human genome discoveries into health care and disease prevention? Genet Med. 2007;9(10):665–674. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31815699d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Teutsch SM, Berger ML, Weinstein MC. Comparative effectiveness: asking the right questions, choosing the right method. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005 Jan-Feb;24(1):128–132. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Drummond M, O’Brien B, Stoddart G, Torrance G. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes. New York: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]