Abstract

During positive selection, developing thymocytes are rescued from programmed cell death by T-cell receptor (TCR)-mediated recognition of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules1–3. MHC-bound peptides contribute to this process4–8. Recently we identified individual MHC-binding peptides which can induce positive selection of a single TCR9. Here we examine peptide fine specificity in positive selection. These data suggest that a direct TCR–peptide interaction occurs during this event, and strengthens the correlation between selecting peptides and TCR antagonists9,10. Certain positively selecting peptides are weakly antigenic9. We demonstrate that thymocytes ‘educated’ on such a peptide are specifically non-responsive to it and have decreased CD8 expression levels. Similar reduction of CD8 expression on mature T cells converts a TCR agonist into a TCR antagonist. These data indicate that thymocytes may maintain self-tolerance towards a positively selecting ligand by regulating co-receptor expression.

Positive selection of T cells occurs at the CD4+8+ stage of development and results in phenotypic changes (including downregulation of CD4 or CD8) and functional maturation2,3,11,12. We previously described a TCR-transgenic mouse (OVA-tcr-1) with a receptor specific for ovalbumin residues 257–264 (OVAp) plus H–2Kb. Thymocytes bearing this receptor are positively selected in fetal thymic organ cultures (FTOCs) expressing Kb (Fig. 1a, d) (ref. 9) but maturation is impaired in FTOCs from β2M−/− mice (Fig. 1b, e), where class I expression is drastically reduced7,13 15. Selection is restored by addition of exogenous β2-microglobulin (β2M) and certain variants of OVAp, exemplified by peptides E1 (Fig. 1c, f) and R4 (Fig. 1g) (ref. 9). This process shows exquisite peptide fine specificity; neither E1R4 (which combines both the E1 and R4 substitutions) nor K4 (which is chemically very similar to R4) are capable of positively selecting the OVA-tcr-1 receptor (Fig. 1h, i). Two theories have been pro-posed to explain peptide specificity in positive selection8,9,16. The TCR may interact directly with both MHC and peptide residues (‘peptide interaction’ model), or it may only recognize MHC residues, in which case the peptide's role is merely to avoid impeding the TCR–MHC interaction (‘peptide avoidance’ model). Our results are hard to reconcile with the latter model; thus if both E1 and R4 simply keep out of the TCR's way, it is likely that E1R4 would do so too, and hence should positively select. Therefore, our data support a peptide interaction model.

FIG. 1.

Flow cytometric analysis of thymocytes from fetal thymic organ cultures of H–2b OVA-tcr-1 mice. Thymi from β2M−/− (a, d) or β2M−/− fetuses (b, c, e–i) were cultured with the indicated peptides. Thymocytes were stained for expression of CD4, CD8 and the transgenic V-alpha region (Vα2). CD4 versus CD8 staining is shown for all live gated cells (a–c) or Vα2hi cells (d–i).

METHODS. FTOC conditions were essentially as described9. Thymus lobes were recovered from fetuses at day 16 of gestation, and cultured in RP10 media containing human β2M (CalBiochem) (5 μg ml−1) and the indicated peptides (at 20 μM), with daily replenishment for 7 days. Peptide names refer to the amino-acid substitutions in OVAp (sequence SIINFEKL). Thus, E1 has a Ser→Glu substitution at position 1. All peptides were synthesized on a Synergy peptide synthesizer (Applied Bio-systems). β2M+/− and −/− lobes were distinguished by staining with Y3 (anti-Kb). Anti-CD4-PE and anti-CD8-FITC were obtained from Becton Dickinson and used directly. The anti-Vα2 antibody B20 (ref. 25) was conjugated to biotin and staining revealed with Tri-colour-streptavidin (Caltag). Analysis was done on a FACScan (Becton-Dickinson) on 20,000 live grated cells.

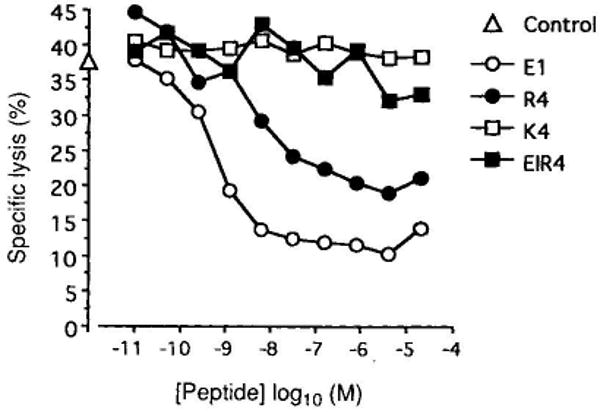

We previously showed that peptides that induce positive selection, including E1 and R4, also act as TCR antagonists9,10 (Fig. 2). K4 and E1R4 did not behave as antagonists (Fig. 2), demonstrating similar fine specificity for positive selection and TCR antagonism. This suggests that the two phenomena may have a similar mechanistic basis, possibly based on TCR affinity for the peptide–MHC ligand9,10,17,18. However, some peptides that are weak agonists induce positive selection at low concentrations and negative selection at higher concentrations (refs 9, 19, 20 and K.A.H. et al., manuscript in preparation). Thus, positive selection is conditioned by both qualitative (perhaps affinity) and quantitative (ligand density) aspects of the TCR interaction.

FIG. 2.

TCR antagonist properties of OVAp analogues used in FTOC. The CTL line TG-O is derived from an OVA-tcr-1 mouse and has been described before9. Lysis of EL4 target cells pre-pulsed with 2 pM OVAp was assayed in the presence or absence of the indicated peptide variants in a 4-h 51Cr-release assay. All four variant peptides bind Kb to a similar extent9 (data not shown). Specific lysis in the absence of variants was 37% and is shown on the abscissa.

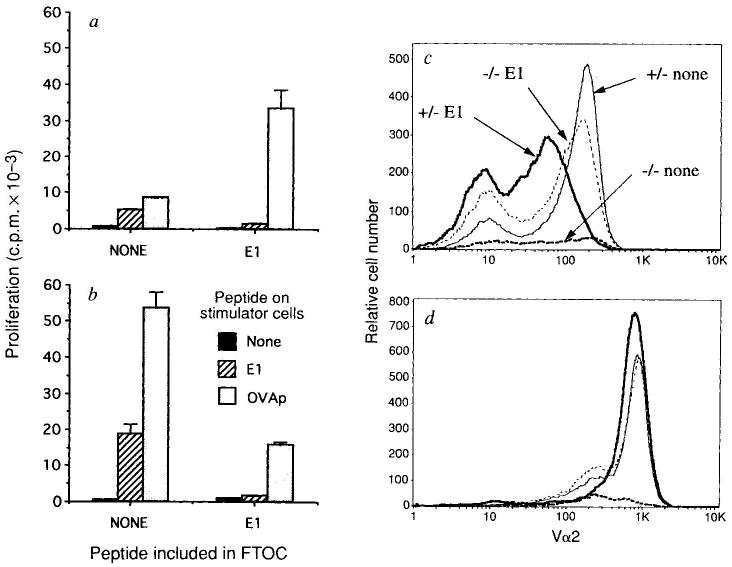

E1 not only antagonizes OVA-tcr-1 T-cell responses (Fig. 2), but is also a weak agonist, stimulating mature transgenic cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs)9 and deleting immature thymocytes in suspension culture (data not shown). We investigated how the presence of E1 during development alters the reactivity of mature OVA-tcr-1 thymocytes (Fig. 3a, b). Thymocytes from TCR-transgenic β2M−/− FTOCs made a very weak response to both OVAp and E1. Addition of E1 during FTOC increased the absolute numbers of CD8+ T cells per lobe and thus the response to OVAp. But these cells were virtually non-responsive to E1 (Fig. 3a). This lack of E1 reactivity is all the more remarkable as the antigen-presenting cells used are β2M+/+ and so present peptides 50–100-fold better than β2M−/− cells7,9. Similarly, inclusion of E1 in OVA-tcr-1 β2M+/− FTOC ablated the E1 response but only partially reduced proliferation to OVAp (Fig. 3b).

FIG. 3.

Functional and phenotypic analysis of OVA-tcr-1 FTOCs cultured with and without peptide E1. β2M−/− (a) and β2M+/− (b) OVA-tcr-1 FTOCs were cultured with or without E1 at 20 μM as indicated. Thymocytes were recovered (four lobes pooled in each group). Numbers (×105) of Vα2hi CD4−8+ cells from each group were β2M+/−, 1.50; β2M+/− plus E1, 0.75; β2M−/−, 0.16; and β2M−/− plus E1, 1.19. a, b, The proliferative response of FTOC thymocytes to EL4 cells, with or without E1 (20 μM) or OVAp (10 nM) pre-coating was determined by 3H-thymidine incorporation. Data show average of triplicate cultures with standard deviation. c, d, An aliquot of the cells recovered from each FTOC was analysed by FACS for expression of Vα2, CD4 and CD8; 10,000 live thymocytes were analysed. After gating for CD4− cells, CD8 (c) and Vα2 (d) expression was determined. The same symbols are used in c and d. The average (n = 4) mean channel fluorescence for CD8 expression on CD8 single positive cells in this experiment was β2M+/−, 154 (±8); β2M+/− plus E1, 74 (±6) (P ≪ 0.001 versus β2M+/−) and β2M−/− plus E1, 120 (±23) (P < 0.05 versus β2M+/−). In an independent experiment the values were β2M+/−, 142 (±3); β2M+/− plus E1, 60 (±6) (P ≪ 0.001 versus β2M+/−) and β2M−/− Plus E1, 115 (±9) (P < 0.002 versus β2M+/−).

METHODS. As for Fig. 1 except for the proliferation assay which was as in ref. 9. Briefly, irradiated EL4 stimulator cells were pulsed with peptide for 1 h and washed. One-twelfth of the pooled thymocytes in each group was incubated with 104 stimulator cells in triplicate cultures. 3H-thymidine was added at 48 h and the culture collected 6 h later.

What is the basis of this selective non-reactivity to E1? We investigated whether thymocyte TCR and/or CD8 expression levels were affected. TCR-α-chain expression was essentially equivalent in all the populations (Fig. 3d), but CD8 expression was significantly lowered on thymocytes from FTOCs in which E1 was included (Fig. 3c). This is seen most dramatically in the β2M+/− FTOC, but is also apparent in cells from β2M−/− lobes in which E1 is the positively selecting ligand. These data suggest that thymocytes can regulate co-receptor expression levels to avoid overt reactivity to the positively selecting ligand. Mature cells bearing low levels of CD8 (CD8lo) could arise from selective survival of CD8lo precursors or by CD8 downregulation on CD8hi precursors. Relative to β2M+/− FTOC we observed a decrease in the number of TCRhi CD8+ cells in β2M−/− plus E1 (∼20%) or β2M+/− plus E1 (∼50%) cultures (see Fig. 3 legend), which supports the former model but does not exclude the latter.

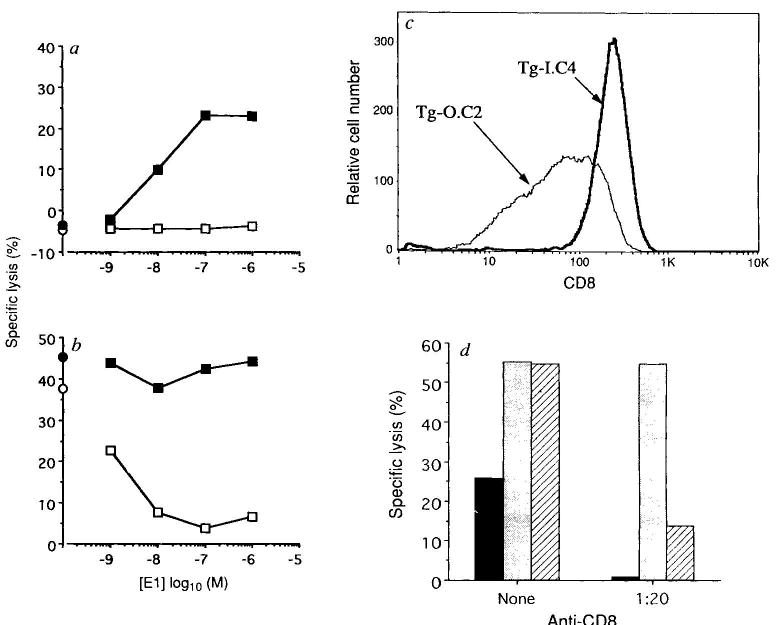

To test whether CD8 expression levels alone could explain the differential response to E1 and OVAp, we analysed mature T-cell clones from OVA-tcr-1 animals (Fig. 4a, b). TG-O.C2 is typical of most clones in that it responded to E1 as an antagonist. However, TG-I.C4 responded to E1 as a weak agonist. This response is completely blocked by an antibody to the transgenic α-chain (data not shown), suggesting that E1 reactivity is not due to expression of an endogenous TCR α-chain. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis indicated that CD8 (Fig. 4c) and TCR (data not shown) expression was higher on TG-I.C4 than TG-O.C2. To assess CD8 contribution in E1 reactivity, we tested the effects of anti-CD8 antibody. Partial CD8 blocking dramatically inhibited the TG-1.C4 response to E1 but, at this dose, did not inhibit OVAp reactivity (Fig. 4d). Interestingly, this treatment resulted in E1 now acting as a potent antagonist for TG-1.C4. Thus, the CD8 interaction can apparently determine whether a ligand is perceived as an agonist or an antagonist.

Fig. 4.

Functional and phenotypic analysis of OVA-tcr-1-derived CTL clones. The clones TG-O.C2 and TG-I.C4 were obtained by limiting dilution from OVA-tcr-1-derived CTL lines. Reactivity of TG-O.C2 (open symbols) and TG-I.C4 (filled symbols) toward E1 was measured on a, EL4 (agonist assay) or b, EL4 prepulsed with 6 pM OVAp (antagonist assay) in a 4-h 51Cr-release experiment. Symbols on the abscissa represent the lysis in the absence of added E1 peptide. c, CD8 expression levels on TG-O.C2 and TG-I.C4 (methods as in Fig. 1). d, Effect of anti-CD8 antibody on the specificity of TG-I.C4. Target cells were EL4 cells plus 1 μM E1 (solid bars), pre-pulsed with 6 pM OVAp (stippled bars) or pre-pulsed with 6 pM OVAp and then coated with 1 μM E1 (hatched bars). The lgG anti-CD8 antibody 53-6 was added (1/20 dilution of tissue culture supernatant) for the duration of the assay where indicated. TG-I.C4 was added at an effector:target ratio of 5:1 and lysis measured after 4 h. Inhibition of the responses by addition of anti-CD8 are: EL4-E1, 98%; EL4-OVAp, 1%; EL4-OVAp-E1, 75%.

During positive selection, a T cell must interact with self MHC while avoiding negative selection on one hand and autoreactivity on the other. This could be achieved by regulation of receptor expression levels and/or signal transduction machinery. Our data suggest that flexibility in CD8 expression levels is one way for thymocytes to fine-tune the efficacy of their interaction with MHC–peptide ligands present in the thymus and achieve positive selection while maintaining self tolerance. In what may be an analogous situation, lowering CD8 expression on mature T cells converts TCR agonists into antagonists. We note that selection by agonist ligands in a different TCR transgenic model yields CD8lo single positive thymocytes also, although the functional potential of these cells was not addressed19,20. In keeping with our observations, CD8 overexpression apparently converts a positively selecting environment into a negatively selecting one21,22. Also, CD8 and/or TCR downregulation in peripheral T cells allows survival in the face of potentially tolerizing antigens23,24.

Acknowledgments

We thank F. Carbone and B. Heath for supplying the TCR transgenic mice and conversation and M. Zollman and K. McConnell for technical assistance. This work was supported by NIAID and HHMI. S.C.J. is a Special Fellow of the Leukemia Society of America.

References

- 1.Bevan M. J Nature. 1977;269:417–418. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sprent J, Webb SR. Adv Immun. 1987;41:39–133. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rothenberg EV. Adv Immun. 1992;51:85–214. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60487-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nikolíc Zugíc J, Bevan MJ. Nature. 1990;344:65–67. doi: 10.1038/344065a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sha WC, et al. Proc natn Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6186–6190. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berg LJ, Frank GD, Davis MM. Cell. 1990;60:1043–1053. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90352-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hogquist KA, Gavin MA, Bevan MJ. J exp Med. 1993;177:1469–1473. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.5.1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ashton-Rickardt PG, Van Kaer L, Schumacher TNM, Ploegh HL, Tonegawa S. Cell. 1993;73:1041–1049. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90281-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hogquist KA, et al. Cell. 1993;76:17–28. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jameson SC, Carbone FR, Bevan MJ. J exp Med. 1993;177:1541–1550. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.6.1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blackman M, Kappler J, Marrack P. Science. 1990;248:1335–1341. doi: 10.1126/science.1972592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.von Boehmer H. A Rev Immun. 1990;8:531–556. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.08.040190.002531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zijlstra M, et al. Nature. 1990;344:742–746. doi: 10.1038/344742a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koller BH, Marrack P, Kappler JW, Smithies O. Science. 1990;248:1227–1230. doi: 10.1126/science.2112266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vitiello A, Potter TA, Sherman LA. Science. 1990;250:1423–1426. doi: 10.1126/science.2124002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moller G, editor. Immun Rev. Vol. 135. 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alexander J, et al. J Immun. 1993;150:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evavold BD, Sloan-Lancaster J, Allen PM. Immun Today. 1993;14:602–609. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90200-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ashton-Rickardt PG, et al. Cell. 1994;76:651–663. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90505-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sebzda E, et al. Science. 1994;263:1615–1618. doi: 10.1126/science.8128249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee NA, Loh DY, Lacy E. J exp Med. 1992;175:1013–1025. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.4.1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robey EA, et al. Cell. 1992;69:1089–1096. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90631-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hammerling G, et al. Immun Rev. 1991;122:47–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1991.tb00596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Auphan N, et al. Int Immun. 1992;4:1419–1428. doi: 10.1093/intimm/4.12.1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grégoire C, et al. Proc natn Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:8077–8081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.18.8077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]