Abstract

Latent cytomegalovirus (CMV) is frequently transmitted by organ transplantation, and its reactivation under conditions of immunosuppressive prophylaxis against graft rejection by host-versus-graft disease bears a risk of graft failure due to viral pathogenesis. CMV is the most common cause of infection following liver transplantation. Although hematopoietic cells of the myeloid lineage are a recognized source of latent CMV, the cellular sites of latency in the liver are not comprehensively typed. Here we have used the BALB/c mouse model of murine CMV infection to identify latently infected hepatic cell types. We performed sex-mismatched bone marrow transplantation with male donors and female recipients to generate latently infected sex chromosome chimeras, allowing us to distinguish between Y-chromosome (gene sry or tdy)-positive donor-derived hematopoietic descendants and Y-chromosome-negative cells of recipients' tissues. The viral genome was found to localize primarily to sry-negative CD11b− CD11c− CD31+ CD146+ cells lacking major histocompatibility complex class II antigen (MHC-II) but expressing murine L-SIGN. This cell surface phenotype is typical of liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs). Notably, sry-positive CD146+ cells were distinguished by the expression of MHC-II and did not harbor latent viral DNA. In this model, the frequency of latently infected cells was found to be 1 to 2 per 104 LSECs, with an average copy number of 9 (range, 4 to 17) viral genomes. Ex vivo-isolated, latently infected LSECs expressed the viral genes m123/ie1 and M122/ie3 but not M112-M113/e1, M55/gB, or M86/MCP. Importantly, in an LSEC transfer model, infectious virus reactivated from recipients' tissue explants with an incidence of one reactivation per 1,000 viral-genome-carrying LSECs. These findings identified LSECs as the main cellular site of murine CMV latency and reactivation in the liver.

In human cytomegalovirus (hCMV) infection, hematopoietic progenitor cells of the myeloid differentiation lineage are a recognized cellular site of virus latency (for more-recent reviews, see references 75 and 94), and cell differentiation-dependent as well as cytokine-mediated viral gene desilencing by chromatin remodeling is discussed as the triggering event leading to virus reactivation (for a review, see reference 7). Although hematopoietic stem cell or bone marrow transplantation (BMT) is frequently associated with hCMV reactivation and recurrence in recipients after hematoablative leukemia/lymphoma therapy, the incidence of virus recurrence and disease is highest in the combination of an hCMV-negative donor (D−) and an hCMV-positive recipient (R+) (D−R+ > D+R+ > D+R−), indicating that donor hematopoietic cells are not the only source of latent hCMV and actually not the predominant source (34). Rather, the recipients experience reactivation of their own virus. Just the opposite is true in the case of solid organ transplantation, where the reactivating virus is mostly transmitted with the transplanted organ (D+R− > D+R+ > D−R+) (34). Collectively, these risk assessments support the suggestion that reactivation, in both instances, occurs in latently infected tissue cells, that is, within the recipient's organs and the transplanted donor organ, respectively. Although tissue-resident cells of hematopoietic origin remain candidates, stromal and parenchymal tissue cells come into consideration as additional sites of CMV latency.

Longitudinal analysis of viral genome load in the latency models of murine CMV (mCMV) infection of neonatal mice (9, 91) as well as of adult mice after experimental BMT (8, 62, 64) has demonstrated a high viral latency burden in multiple organs long after clearance of viral DNA from bone marrow and blood (reviewed in reference 92). These findings support the suggestion that there exist two types of latency, namely, a temporary latency in hematopoietic cells and a latency in tissue cells that lasts through life. Accordingly, both types of latency may coexist early after primary infection, while “late latency” is restricted to organ sites. As we have shown previously in a sex-mismatched murine BMT model, bone marrow cells (BMCs) derived from latently infected donors in the phase of organ-restricted “late latency” cannot transmit latent or reactivated infection to naïve recipients upon intravenous cell transfer (99).

A first hint for mCMV latency in stromal or reticular cells was presented long ago by Mercer and colleagues (73), who showed that infected cells during acute infection of the spleen are predominantly sinusoidal lining cells and that latent mCMV can be recovered from a major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II) antigen-negative and Thy-1 (CD90)-negative “stromal” cell fraction, which includes endothelial cells (ECs). These findings strongly argued against T and B lymphocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells (DCs) being major reservoirs of latent mCMV in the spleen, a conclusion supported by later work of Pomeroy and colleagues (86). Similarly, Klotman and colleagues (54) as well as Hamilton and Seaworth (44) concluded that in kidney transplantation, donor kidney is the source of latent mCMV and that the latent viral genome is harbored by renal peritubular epithelial cells (53). A first hint for mCMV latency in ECs within the liver was provided by in situ PCR images presented by Koffron and colleagues (59) showing nuclear staining in cells with a microanatomical localization suspicious of liver sinusoidal ECs (LSECs). For hCMV, ECs, in particular those in arterial vessel walls, are regarded as a site of latency on the basis of the presence of viral DNA in cells expressing an EC marker (81; for a review, see reference 48), although other authors did not detect viral DNA in venous vessel walls (95). As discussed by Jarvis and Nelson (48), these data are not necessarily conflicting but may rather reflect the diversity of EC subsets at different anatomical locations (21, 27). As far as we know, and reactivation of productive infection from ECs that carry latent viral DNA is not yet formally proven for any type of EC.

Hepatitis is a relevant organ manifestation of CMV disease in immunocompromised hosts (65), and hCMV reactivation has been reported to be the most common cause of infection following liver transplantation, in particular in a D+R− combination (34, 76). In the murine model of immunocompromised hosts, viral histopathology in the liver is dominated by the cytopathogenic infection of hepatocytes, leading to extended plaque-like tissue lesions (41, 84; reviewed in reference 45). Occasionally, however, in these studies, infected hepatic ECs as well as Kupffer macrophages were detected by virus-specific immunohistology or by in situ virus-specific DNA hybridization.

Using cell-type-specific conditional recombination of a fluorescence-tagged reporter virus in Cre-transgenic mice expressing Cre selectively in hepatocytes under the control of the albumin promoter, hepatocytes were recently identified as the main virus-producing cell type during mCMV infection. In Cre-transgenic mice expressing Cre selectively in vascular ECs under the control of the Tie2 promoter, the reporter virus was found to recombine also in LSECs, which released an amount of virus sufficient for virus spread to neighboring hepatocytes, although the virus productivity of LSECs was low and contributed little to the overall virus load in the liver (97).

LSECs represent a unique liver-resident population of antigen-presenting cells that bear the capacity to cross-present antigens to naïve CD8 T cells (68, 69; reviewed in reference 57). They constitute the fenestrated endothelial lining of the hepatic sinusoids (15). By separating the sinusoidal compartment of the liver from the space of Disse and the liver parenchyma, LSECs form a boundary surface for sensing of pathogens and interaction with passenger lymphocytes. They perform a scavenger function contributing to hepatic clearance of bacterial degradation products derived from the gastrointestinal tract (103; reviewed in reference 57). According to this physiological role, antigen presentation by LSECs is associated with tolerance induction rather than with triggering an inflammatory immune response (29, 56, 68, 104).

Here we provide evidence to support the suggestion that mCMV has chosen the tolerogenic and long-lived LSECs as an immunoprivileged niche for establishing viral latency in the liver.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental BMT and establishment of latent mCMV infection.

Sex-mismatched but otherwise syngeneic BMT with male BALB/c mice as BMC donors and female BALB/c mice as BMC recipients was performed as described previously (83). In brief, hematoablative conditioning of 8- to 10-week-old recipients was achieved by total-body gamma irradiation with a single dose of 6.5 Gy. BMT was performed 6 h later by infusion of 5 × 106 femoral and tibial donor BMCs into the tail veins of the recipients. At ca. 2 h after BMT, recipients were infected with 105 PFU of mCMV (strain Smith ATCC VR-194, purchased in 1981; the stock virus has been passaged only four times since then) in the left hind footpad. Criteria for the definition of latency were specified previously (for a review, see reference 92) and include the absence of infectivity in key organs of CMV tropism (liver, spleen, lungs, and salivary glands) as well as reduction of viral DNA load in tail vein blood to less than one copy per 104 leukocytes in a longitudinal analysis using M55/gB-specific real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) (99). Clearance of viral DNA from blood is the criterion that takes longest to be fulfilled in the BMT model, usually ∼8 months (62, 99). Animals were bred and housed under specified-pathogen-free conditions in the Central Laboratory Animal Facility (CLAF) of the Johannes Gutenberg University. Animal experiments were approved by the Landesuntersuchungsamt Rheinland-Pfalz according to German federal law § 8 Abs. 1 TierSchG under permission number 177-07/021-28.

Quantitation of viral and cellular genomes by qPCR.

Quantitation of the viral gene M55/gB, the diploid cellular gene pthrp (71), and the (male) sex-determining region on chromosome Y, gene sry (60), formerly known as the testis-determining gene on chromosome Y, gene tdy (42), was performed by qPCR with primers and probes specified in the following sections.

(i) M55/gB.

For M55/gB-specific qPCR, oligonucleotide 5′-TGCTCGGTGTAGGTCCTCTCCAAGCC-3′ (nucleotides [nt] 83,175 to 83,200) (89) (GenBank accession no. U68299; complete genome) was used as probe gB_Taq_Probe2, oligonucleotide 5′-CTAGCTGTTTTAACGCGCGG-3′ (nt 83,137 to 83,156) served as forward primer gB_Taq_For2, and oligonucleotide 5′-GGTAAGGCGTGGACTAGCGAT-3′ (nt 83,227 to 83,207) served as reverse primer gB_Taq_Rev2, yielding an amplification product of 91 bp.

(ii) pthrp.

For pthrp-specific qPCR, oligonucleotide 5′-TTGCGCCGCCGTTTCTTCCTC-3′ (nt 177 to 197) (71) (GenBank accession no. M60056) was used as probe PTHrP_Taq_Probe1, oligonucleotide 5′-CAAGGGCAAGTCCATCCAAG-3′ (nt 155 to 174) served as forward primer PTHrP_Taq_For1, and oligonucleotide 5′-GGGACACCTCCGAGGTAGCT-3′ (nt 255 to 236) served as reverse primer PTHrP_Taq_Rev1, yielding an amplification product of 101 bp.

(iii) sry.

For sry-specific PCR, oligonucleotide 5′-AGTTGGCCCAGCAGAATCCCAGC-3′ (nt 162 to 184) (42) (GenBank accession no. X55491) was used as probe Tdy_Taq_Probe1, oligonucleotide 5′-AAGCGCCCCATGAATGC-3′ (nt 113 to 129) served as forward primer Tdy_Taq_For1, and oligonucleotide 5′-CCCAGCTGCTTGCTGATCTC-3′ (nt 216 to 197) served as reverse primer Tdy_Taq_Rev1, yielding an amplification product of 104 bp.

Quantitation was performed on the model 7500 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) by using dually labeled probes containing a fluorescent reporter at the 5′ end, a quencher at the 3′ end (6-carboxyfluorescein reporter and 6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine quencher system; Operon Biotechnologies, Cologne, Germany), and the TaqMan universal PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems). All reactions were performed in a total volume of 20 μl, containing 10 μl of 2× TaqMan universal master mix, a 1 μM concentration of each primer, and a 0.25 μM concentration of the probe. Two-step PCR was performed with the following cycler conditions: an initial step for 10 min at 95°C to activate DNA polymerase followed by 50 cycles of 15 s at 95°C and a combined primer annealing/extension step for 1 min at 60°C, during which time data were collected. Standard curves for quantitation were established by using graded numbers of linearized plasmid pDrive_gB_PTHrP_Tdy (101) as the template.

DNA isolation from host tissues and cells. (i) Isolation of DNA from latently infected liver tissue.

To remove circulating intravascular leukocytes, livers from latently infected mice were perfused by standard procedures with Gey's balanced salt solution (GBSS; 137 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1.6 mM CaCl2·2H2O, 0.9 mM MgCl2·6H2O, 0.3 mM MgSO4·7H2O, 0.2 mM KH2PO4, 1.7 mM Na2HPO4·2H2O, 2.7 mM NaHCO3, 5.5 mM glucose, 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) and were then homogenized in a model MM300 mixer mill (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) with a steel ball (0.118 in.) at 30 Hz for 3 min. Twenty-five milligrams of liver homogenate was used for DNA isolation with the DNeasy blood and tissue kit (catalog no. 69506; Qiagen) as described previously (113).

(ii) Isolation of DNA from MACS-enriched cells.

Cells of defined cell surface marker phenotypes were enriched by positive (immuno)magnetic cell sorting (MACS) as described below, and DNA was then extracted with the DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen) as outlined previously (113), according to the manufacturer's spin column protocol from step 1c onward (87).

(iii) Isolation of DNA from MACS-enriched LSECs for limiting dilution analysis.

The DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen) was used for DNA extraction (see above), except that 500 ng of double-stranded poly(dA-dT) carrier DNA (catalog no. 27-7870; Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) was added to each LSEC preparation sample. DNA was eluted in 200 μl elution buffer. The isolated DNA was precipitated with 500 μl of absolute ethanol and 20 μl of 3 M sodium acetate, pH 4.5, overnight at −20°C. Finally, precipitated DNA was dissolved in 5 μl Tris buffer, pH 8.0, and the entire sample was used for M55/gB-specific real-time quantitation.

Virus reactivation in liver tissue explants from latently infected mice.

Livers were perfused as described above and were transferred into minimal essential medium plus GlutaMAX (Invitrogen, Paisley, United Kingdom) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (PAA, Pasching, Austria) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen). They were then immediately cut into pieces with an edge length of 2 to 4 mm, and these were plated separately into 24-well plates (catalog no. 353047; BD Biosciences) with 1 ml medium per well. At defined intervals, 300 μl of cell culture supernatant was transferred onto semiconfluent mouse embryo fibroblasts for viral plaque assay (PFU assay) by the technique of centrifugal enhancement of infectivity as described in greater detail elsewhere (references 64 and 83 and references therein). In all explant cultures, the sampled medium was replaced with 300 μl of fresh medium.

Preparation of hepatocyte suspensions.

Hepatocytes were isolated from mouse livers as described previously (113), except that the collagenase buffer was supplemented with 0.05% NB 4 standard-grade collagenase (Serva, Heidelberg, Germany).

Preparation of nonparenchymal liver cell suspensions.

Nonparenchymal but liver-resident cells (NPLCs), which account for about 35% to 40% of total liver cells (31, 112) and for about 6% of the total liver mass (13), were isolated from mouse livers as described previously (50, 58) with the following modifications. Briefly, mice were euthanized, and the portal vein was dissected and cannulated with a 26-gauge needle. Thereafter, the posterior vena cava was opened to allow outflow of the perfusion solution. Perfusion was performed for 10 s with 0.05% collagenase A (Roche, Mannheim) in GBSS solution with a flow rate of 5 ml/min. The liver was then excised, and connective tissue and the gallbladder were removed. The organ was mechanically separated using forceps, followed by a 45-min incubation in GBSS buffer supplemented with 0.05% collagenase A and 2,000 U DNase I (Roche, Mannheim) in a rotary water bath at 37°C and 200 rpm. The resulting cell suspension was then passed first through a sterile steel mesh and thereafter through a sterile 100-μm nylon cell strainer (BD Biosciences) and was washed two times with GBSS at 400 × g for 10 min. For density gradient separation, the pellet containing the NPLCs was resuspended in 3 ml GBSS and added to a working solution of 30% [wt/vol] iodixanol (Optiprep; Axis-Shield, Norway) for a final concentration of 17% iodixanol (final density, 1.096 g/ml) to remove debris and enrich the NPLCs. To avoid exsiccation of the cells, the suspension was overlaid with 2 ml GBSS and centrifuged at 400 × g for 15 min with the brake turned off. The layer of low-density cells at the interface was harvested, and the NPLCs were washed with GBSS at 400 × g for 10 min. After being washed, the pellet was resuspended in 10 ml GBSS for cell counting.

Separation and phenotype analysis of NPLCs.

The following MicroBeads and antibodies were used for MACS and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS): anti-fluorescein MicroBeads (catalog no. 130-048-701; Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), rat anti-mouse CD146 (LSEC-antigen) MicroBeads (catalog no. 130-092-007; Miltenyi Biotec), rat anti-mouse CD4 (L3T4) MicroBeads (catalog no. 130-049-201; Miltenyi Biotec), rat anti-mouse CD11b MicroBeads (catalog no. 130-049-601; Miltenyi Biotec), hamster anti-mouse CD11c MicroBeads (catalog no. 130-052-001; Miltenyi Biotec), rat anti-mouse CD45R MicroBeads (catalog no. 130-049-501; Miltenyi Biotec), allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated rat anti-mouse MHC-II antibody (Ab) (clone M5/114, catalog no. 130-091-806; Miltenyi Biotec), rat anti-mouse CD16/CD32 Ab (anti-Fcγ III/II receptor, clone 2.4G2, catalog no. 553142; BD Biosciences), fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated rat anti-mouse CD31 Ab (clone 390, catalog no. 558738; BD Biosciences), FITC-conjugated rat anti-mouse CD106 Ab (clone 429, catalog no. 553332; BD Biosciences), rat anti-mouse LSEC-antigen CD146 Ab (clone ME-9F1, catalog no. 130-092-026; Miltenyi Biotec), R-phycoerythrin (R-PE)-conjugated rat anti-mouse CD31 Ab (clone 390, catalog no. MCA1364PE; AbD Serotec, Kidlington, United Kingdom), Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated rat anti-mouse-specific ICAM-3-grabbing nonintegrin-related protein R1 (anti-mSIGN-R1) Ab (clone ER-TR9, catalog no. MCA2394A647; AbD Serotec), and acetylated low-density lipoprotein labeled with Dil dye (Dil-AcLDL; catalog no. L3484; Molecular Probes, Leiden, The Netherlands). LSEC-specific Abs ME-9F1-FITC and ME-9F1-biotin, used earlier in this study, were a generous gift from A. Hamann, Berlin, Germany.

(i) Immunomagnetic cell sorting.

NPLC subpopulations expressing the cell surface markers CD4, CD31, CD106, CD11b, CD11c, CD45R, and CD146 were enriched from total NPLCs by two sequential runs of automated MACS with the autoMACS system (Miltenyi Biotec) or, in the case of sterile isolation of cells, by one run of manual magnetic cell sorting. In brief, up to 107 cells were resuspended in 90 μl MACS buffer (2 mM EDTA in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS] containing 0.5% [wt/vol] bovine serum albumin) and mixed with 10 μl of the corresponding MicroBeads. For separation of more than 107 cells, MACS buffer and MicroBeads were adjusted accordingly. After 15 min of incubation in the dark at 4°C, followed by washing and resuspension of the respective cells in MACS buffer, immunomagnetic sorting was performed by using the Posseld separation program (Miltenyi Biotec) for automatic two-column separation or by using LS columns for manual separation.

(ii) Two-color cytofluorometric analysis.

To determine the purity of isolated LSECs, the cells were incubated with Dil-conjugated AcLDL for 1 h at 37°C. After incubation, the cells were washed and saturated with 1 μg CD16/CD32 monoclonal Ab per million cells to block Fc receptor binding sites. After a washing step, cells were labeled with the FITC-conjugated Ab anti-LSEC antigen CD146. Stainings were carried out in FACS buffer (10 mM EDTA and 20 mM HEPES in PBS containing 0.4% [wt/vol] bovine serum albumin and 0.003% [wt/vol] NaN3). All labeling procedures were performed on ice to minimize receptor capping or receptor internalization. The analysis was performed with a FACSort (BD Biosciences) using CellQuest 3.3 software for data processing. Fluorescence channel 1 (FL-1) represents fluorescein fluorescence (green), and FL-2 represents Dil fluorescence (red).

(iii) Cytofluorometric cell sorting.

For the cytofluorometric purification of CD31+ CD146+ cells, density gradient-enriched NPLCs (see above) were saturated with 1 μg CD16/CD32 monoclonal Ab per million cells to block Fc receptor binding sites and were labeled in the combination CD31-R-PE and CD146-FITC. For the cytofluorometric separation of MHC-II+ CD146+ and MHC-II− CD146+ cells, MACS-enriched LSECs were likewise blocked against Fc receptor binding and were labeled in the combination MHC-II-APC and CD146-FITC. Cytofluorometric separation of SIGN-R1+ CD146+ cells from density gradient-enriched NPLCs (see above) was performed after blocking of Fc receptor binding and labeling of the NPLCs in the combination CD146-FITC and SIGN-R1-Alexa Fluor 647. All stainings were carried out in FACS buffer. The cell sorter used was a FACSVantage cell sorter (BD Biosciences). The excitation wavelengths were 488 and 633 nm. Band pass filters for 525, 575, and 660 nm were used to measure FITC, PE, and both APC and Alexa Fluor 647 fluorescence, respectively. Sort gates were set on living cells in the forward-versus-side scatter plot as well as on positive FL-1 (FITC) and FL-2 (R-PE) or positive FL-1 (FITC) and FL-4 (APC, Alexa Fluor 647), respectively. Recovered cells were collected in polystyrene tubes.

Cultivation of MACS-enriched LSECs.

MACS-purified LSECs were resuspended in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium plus GlutaMAX (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (PAA, Pasching, Austria) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco), and were incubated for 24 h in collagen-coated six-well plates at a density of 3 × 106 LSECs per six-well culture. For collagen coating of six-well plates, collagen R solution (Serva, Heidelberg, Germany) was diluted 1:10 with sterile water, and 2 ml of the solution was placed into each six-well vial, followed by drying at 25°C.

Immunofluorescence analysis of MACS-enriched LSECs.

MACS-purified LSECs were cultivated for 24 h on fibronectin-coated coverslips in 24-well plates at a density of 8 × 105 cells per well in the presence of 1.5 μg BODIPY FL-conjugated AcLDL (catalog no. L3485; Molecular Probes) per ml. After three washes with PBS, cell nuclei were stained by incubation of the coverslips for 5 min with the DNA-binding, blue-fluorescing dye Hoechst 33342 (catalog no. H3570; Molecular Probes) (1:5,000 in PBS). Finally, cells were washed three times in PBS, and the coverslips were mounted with GelMount 295 aqueous mounting medium (catalog no. G0918; Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany).

Construction of plasmids.

Recombinant plasmids were constructed according to established procedures, and enzyme reactions were performed as recommended by the manufacturers. Synthetic transcripts were prepared according to the instructions given in the MEGAscript SP6 kit (Ambion, Austin, TX) technical manual (3).

(i) Plasmid pDrive_M86 for the synthesis of M86 in vitro transcripts.

A DNA fragment of M86/MCP (19, 89) was amplified by PCR from DNA derived from a virus stock of mCMV-BAC (bacterial artificial chromosome-cloned mCMV MW97.01) (111). Oligonucleotides M86_For1 (5′-AGGACACGCTGCTGGACAAG-3′), representing map positions 126,827 to 126,808, and M86_Rev1 (5′-TACTCGTGCGCGAAGATGGG-3′), representing map positions 124,361 to 124,380 (GenBank accession no. U68299; complete genome) (89), served as forward and reverse primers, respectively. The 2,467-bp amplification product containing an M86 sequence fragment from map positions 124,361 to 126,827 was inserted into the pDrive cloning vector (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) by means of UA-based ligation to generate the 6,320-bp plasmid pDrive_M86. For use as a template in the in vitro transcription, plasmid pDrive_M86 was linearized by digestion with SphI.

(ii) Plasmid pSP64_IE1_IE3_poly(A) for the synthesis of immediate early 1 (IE1)-IE3 duplex in vitro transcripts.

Plasmid pSP64_IE3_poly(A) was generated by subcloning the HindIII/XbaI restriction fragment of plasmid pBlue-ie3 (62) in the vector plasmid pSP64_poly(A) (Promega, Madison, WI). An 831-bp ie3 fragment consisting of a part of exon 2, intron 2, exon 3, and a part of exon 5 was amplified from plasmid pSP64_IE3_poly(A) with primers IE3-SalI_For (5′-AAAGTCGACCGGCCGTCACTTGG-3′), representing map positions 5,876 to 5,889 (GenBank accession no. 330543), and IE3-BamHI_Rev (5′-AAAGGATCCCGTGTGGCCTGTACC-3′), representing map positions 8,529 to 8,543. The SalI and BamHI restriction sites are underlined. After digestion of the amplificate with BamHI and SalI, plasmid pSP64_IE1_IE3_poly(A) was generated by cloning of the restriction fragment into the BamHI- and SalI-digested plasmid pSP64_IE1_poly(A) (62).

Isolation of total RNA from LSECs of latently infected mice.

RNA was isolated using the RNeasy minikit (catalog no. 74106; Qiagen) as described in the manufacturer's animal cell protocol (88). Cultivated LSECs were lysed directly in the cell culture well by adding lysis buffer. Lysates were collected with a cell scraper and homogenized by using QIAshredder spin columns (catalog no. 79656; Qiagen). Freshly isolated LSECs were pelletized, resuspended in 350 μl of lysis buffer, and homogenized by using QIAshredder spin columns. RNA was bound to the RNeasy Mini spin column, followed by digestion of contaminating DNA with DNase using the RNase-free DNase set (catalog no. 79254; Qiagen). After two washing steps, bound RNA was eluted twice in 45 μl of RNase-free water. To ensure that all contaminating DNA was removed, a second DNase digestion was performed. The RNA was cleaned by using the RNeasy minikit according to the RNA cleanup protocol (Qiagen) (88). Finally, the RNA was eluted in 50 μl RNase-free water.

Analysis and quantitation of viral transcripts.

Quantitation of viral transcripts from genes m123 (ie1), M122 (ie3), M112-M113 (e1), and M55 (gB) was performed by one-step reverse transcriptase (RT) qPCRs (RT-qPCRs) with primers and probes specified previously (100). For the IE1-IE3 duplex RT-qPCR, the dually labeled probe ie1-taq1 consisted of a 6-carboxyfluorescein reporter at the 5′ end and a Black Hole Quencher (BHQ1a) at the 3′ end. Probe ie3-taq1 consisted of a Cy5 reporter at the 5′ end and a Black Hole Quencher (BHQ3a) at the 3′ end. For quantitation of viral transcript M86, which codes for the major capsid protein (MCP), oligonucleotide 5′-TCGGCCGTGTCCACCAGTTTGATCT-3′ (nt 125,996 to 126,020; GenBank accession no. U68299; complete genome) (89) was used as probe M86_Taq_Probe1. Oligonucleotide 5′-GGTCGTGGGCAGCTGGTT-3′ (nt 125,977 to 125,994) served as forward primer M86_Taq_For1, and oligonucleotide 5′-CCTACAGCACGGCGGAGAA-3′ (nt 126,041 to 126,023) served as reverse primer M86_Taq_Rev1, yielding an amplification product of 65 bp.

Quantitations were performed on a model 7500 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) by using dually labeled probes containing a fluorescent reporter at the 5′ end and a quencher at the 3′ end (Operon Biotechnologies). The corresponding in vitro transcripts IE1, IE3, early 1 (E1), gB, and MCP were generated as outlined above and described previously (62, 100) and were used as standards for quantitation. Standard titrations ranged from 106 to 10 in vitro transcripts, with 100 and 10 transcripts being measured in duplicate and triplicate, respectively. IE1 plus IE3 (duplex RT-qPCR), E1, gB, and MCP transcripts in LSECs from latently infected mice were quantified from triplicate 1/25 (4%) aliquots of the yield of total RNA from each sample, and the number of transcripts in 500 ng of total RNA was extrapolated. Reactions for gB and MCP transcripts were performed in a total volume of 25 μl, containing 5 μl of 5× Qiagen OneStep RT-PCR buffer, 1 μl of Qiagen OneStep RT-PCR enzyme mix, 668 μM of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 0.76 μM of each primer, 0.26 μM probe, an additional 1.5 mM concentration of MgCl2, and 0.132 μM ROX (5-carboxy-X-rhodamine) as the passive reference. The reaction mixtures for IE1 plus IE3 transcripts in the duplex RT-qPCR and for E1 transcripts in the singleplex RT-qPCR were modified in that the primer concentrations were 0.4 μM and 1 μM, respectively. Reverse transcription was performed for 30 min at 50°C. The cycle protocol for cDNA amplification started with an activation step for 15 min at 95°C and was followed by 50 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 15 s and a combined primer annealing/extension step at 60°C for 1 min. The efficacy of the RT-qPCRs was >90% throughout. In the case of unspliced gB and MCP transcripts, the reaction was also performed in the absence of RT to exclude amplification from template DNA instead of RNA.

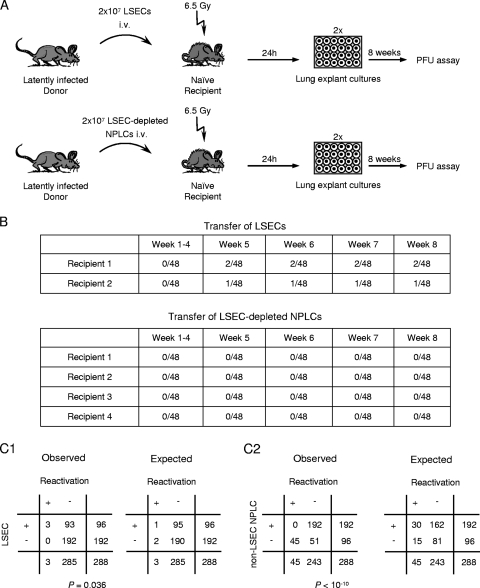

Virus reactivation from latently infected cells.

For identifying cell types capable of virus reactivation, LSEC-enriched (positive MACS) and LSEC-depleted (MACS flowthrough) NPLCs derived from three latently infected XY-XX chimeras were transplanted into naïve female recipients that were immunocompromised (by 6.5 Gy of total-body gamma irradiation 24 h prior to transfer). One aliquot from each donor cell fraction was used to determine viral DNA load and the proportion of donor-derived sry-positive cells. Both fractions were adjusted in PBS to 2 × 107 cells/ml, and 1 ml of the respective cell suspension was administered intravenously to each recipient in two rounds at 500 μl. One day after transplantation, the lungs were excised and cut into pieces with an edge length of around 2 to 4 mm. The lung explants were placed into 24-well culture plates with no feeder cells and were kept in culture for up to 8 weeks. At weekly intervals, 300 μl of cell culture supernatant was replaced with fresh culture medium and was transferred onto semiconfluent mouse embryo fibroblasts for a virus plaque assay (PFU assay) by the technique of centrifugal enhancement of infectivity (see above).

Mathematical calculations and statistical analysis. (i) Calculation of mean values and their 95% confidence limits.

Mean values and standard deviations were calculated by using the standard deviation calculator provided on the website http://invsee.asu.edu/srinivas/stdev.html. On the basis of the so-determined mean value, the standard deviation, and the number of samples, the 95% confidence intervals (CI) of the mean were calculated by a program provided on the website http://glass.ed.asu.edu/stats/analysis/mci.html.

(ii) Limiting dilution analysis.

The frequency (reciprocal of the most probable number [MPN]) of cells carrying latent viral DNA and the corresponding 95% CI of the MPN were estimated by limiting dilution analysis (66) using the maximum-likelihood method for calculation (35). The calculation is based on the Poisson distribution equation λ = −ln f(0), where λ is the Poisson distribution parameter lambda and f(0) is the experimentally determined fraction of negative samples/replicates, that is, in this specific case, samples negative for viral DNA in the qPCR for graded numbers of cells seeded. By definition, λ is 1 for an f(0) of 1/e. Accordingly, in a semilogarithmic plot of cell numbers seeded (abscissa) and −ln f(0) (ordinate), the MPN is revealed as the abscissa coordinate of the point of intersection between 1/e and the calculated regression line.

(iii) Calculation of positive samples at a given Poisson distribution parameter lambda.

If a number of events (n), that is, the number of viruses that reactivated in this specific case, occurs in a total number of samples (N), that is, in plated lung tissue pieces in this specific case, then the Poisson distribution parameter is calculated by λ = n/N. Since each positive sample may comprise one event or more than one event, the number of positive samples is actually less than the number of events. The fraction of negative samples [F(0)] can be calculated according to the Poisson distribution equation as F(0) = e−λ. Accordingly, the fraction of positive samples can be calculated by the equation F(>0) = 1 − F(0). In turn, the number of events can be higher than the number of positive samples. So, if the fraction of negative samples [F(0)] is known, the Poisson distribution parameter can be calculated as λ = −ln F(0). The fractions of positive samples containing n events [F(n)] can be calculated by the formula F(n) = λ/n × F(n − 1) for all n > 0. The total number of events is then the sum of all F(n) multiplied by the total number of samples.

(iv) Significance analysis with two-by-two contingency tables.

Two-sided P values from observed two-by-two contingency tables were calculated by using Fisher's exact test (method of the sum of small P values) provided for online calculation on the website http://www.quantitativeskills.com/sisa/statistics/fisher.htm, according to the recommendations of SISA (Simple Interactive Statistical Analysis) (1, 110). Groups are regarded as being significantly different for the test parameter, virus reactivation in LSEC-enriched and LSEC-depleted cells in this specific case, if P is <0.05.

RESULTS

Establishment of reactivatable viral latency in the livers of sex-mismatched bone marrow chimeras.

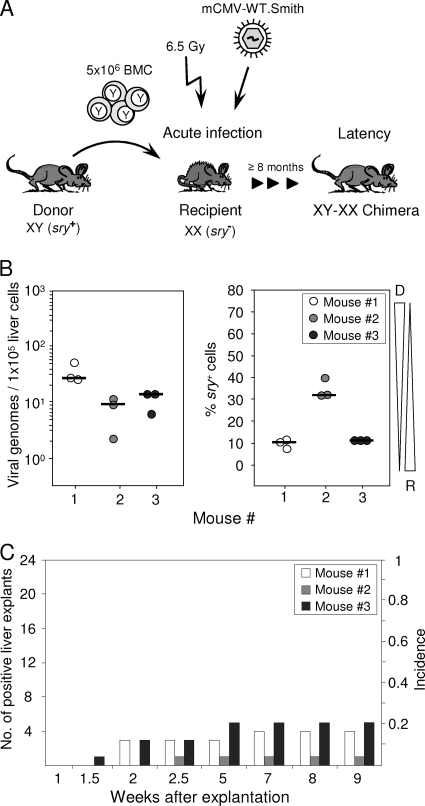

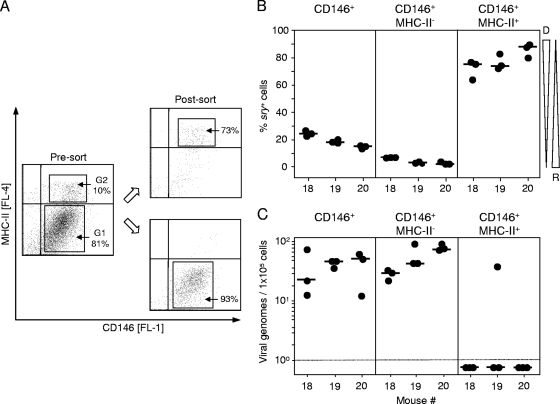

BMT leads to a mixed chimerism in transplantation recipients with cells of hematopoietic lineages being donor derived and repopulating the recipients' bone marrow stroma and lymphoid tissues. Using male donors and female recipients, the Y chromosome, represented by the sry/tdy gene (42, 60), which is detectable by qPCR, can thus serve as a molecular marker to identify and quantitate donor-derived cells in organs of the XY-XX chimeras (Fig. 1A). Viral pathogenesis and immune system reconstitution in this model have been studied in great detail previously (for a review, see reference 45). Notably, mCMV infection of BMT recipients was found to inhibit the engraftment of hematopoietic donor-derived stem and progenitor cells in the recipients' bone marrow stroma by nonproductive infection of stromal cells associated with a deficient expression of hemopoietins (72, 105). Whereas this can result in a lethal bone marrow aplasia under conditions of low-dose BMT, a high-dose syngeneic or even MHC-I-disparate BMT facilitates timely immune reconstitution and control of productive infection in host organs by CD8 T cells (2, 46, 84), leading to viral latency (64). Here we have chosen the high-dose BMT protocol to control acute infection and establish latency in the XY-XX chimeras. As shown in Fig. 1B for three individual chimeras after clearance of productive infection as well as qPCR-controlled clearance of the viral genome from vascular compartment passenger leukocytes (99; data not shown), resident cells in perfused liver tissue harbored latent viral genomes at a load that did not apparently correlate with the proportion of donor-derived sry+ cells of hematopoietic origin. Variance in the proportion of sry+ cells likely reflects variable lymphoid cell infiltration of the liver, but this was not investigated further here. The definition of latency implies that viral genomes are not replication defective but can be reactivated to productive infection (96). This was verified by liver tissue explant cultures (Fig. 1C). Whereas absolutely no virus was recovered from homogenized tissue material derived from the same livers (negative data not shown), recurrence occurred from the explanted tissue pieces with an incidence of ∼20%.

FIG. 1.

Reactivation of mCMV from liver explants of latently infected bone marrow chimeras. (A) Experimental regimen. Sex-mismatched allogeneic BMT was performed with male BALB/c mice (XY; sry+) as BMC donors and female BALB/c mice (XX; sry−) as BMC recipients that were immunocompromised by total-body gamma irradiation with a single dose of 6.5 Gy and infected with wild-type (WT) mCMV, strain Smith. Viral latency and reactivation were usually studied at a minimum of 8 months after acute infection, when the viral genome was naturally cleared from circulating leukocytes. Note that throughout this paper, individually tested bone marrow chimeras are numbered consecutively. (B) Quantitation of latent viral genomes and of donor-derived cells in the livers of three individual bone marrow chimeras (mice 1 to 3) at 9 months after BMT and infection. M55/gB- and sry-specific qPCRs were performed with DNA isolated from 25-mg pieces of the livers. Circles represent triplicate measurements of each sample DNA (see inset legend). Median values are marked. The viral genome load is shown normalized to 1 × 105 liver cells. Tapered wedges symbolize the proportions of donor (D)- and recipient (R)-derived cells. (C) Reactivation of infectious mCMV in 24 liver explant cultures from each of the same three individual mice for which latent viral DNA load and chimerism are shown in panel B. Bars represent numbers of positive liver explant cultures (left ordinate scale) and incidences of reactivation (right ordinate scale).

The latent viral genome localizes to nonparenchymal liver cells.

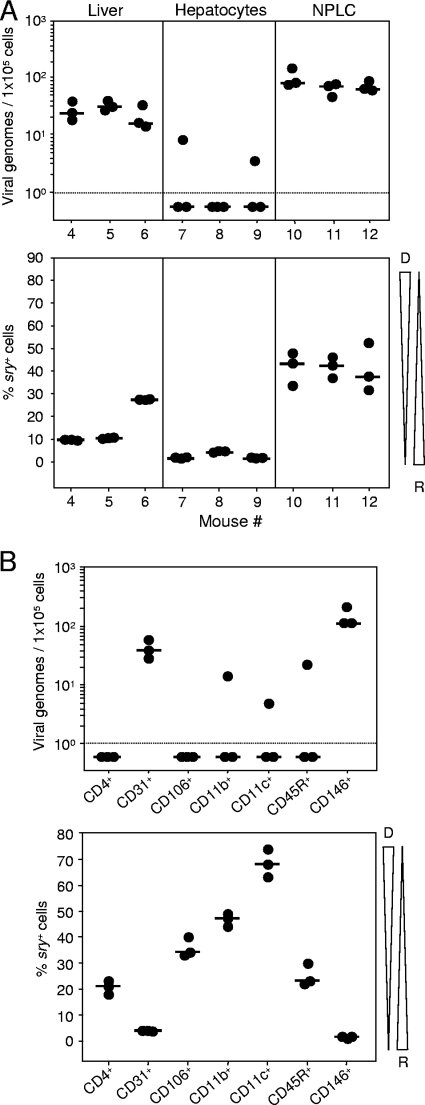

Liver tissue can roughly be subdivided into liver parenchymal cells, namely, the hepatocytes, and NPLCs, which include LSECs, Kupffer-type macrophages, liver-specific natural killer (NK) or pit cells, and hepatic stellate cells, formerly known as fat-storing and vitamin A-rich perisinusoidal Ito cells (55). Separating liver tissue into hepatocyte and NPLC fractions revealed an enrichment of latent mCMV DNA in the NPLC fraction (Fig. 2A, top panel), which accounts for only ∼6.5% of the liver volume but ∼40% of the total number of hepatic cells. This finding excludes the main virus producer in acute infection, the hepatocyte (97), from the candidate list of latently infected liver cell types. In agreement with the fact that NPLCs comprise long-lived liver-resident cells and short-lived repopulating cells of hematopoietic origin, ∼40 to 50% of the cells in the NPLC fraction were of the sry+ genotype (Fig. 2A, bottom panel). The NPLC fraction was then further subdivided by positive immunomagnetic cell sorting specific for a panel of cell surface marker molecules for phenotype screening (Fig. 2B). This localized latent viral DNA to two cell surface marker-defined cell populations, namely, to CD31+ NPLCs and to CD146+ NPLCs (Fig. 2B, top panel), the two cell populations with the lowest proportion of cells of donor genotype (Fig. 2B, bottom panel). This excludes a major contribution of donor-derived hematopoietic lineage NPLCs, including Kupffer cells, liver NK cells, and also hepatic stellate cells (6), to the load of the latent viral genome in the liver. Recipient origin combined with expression of CD146, also known as the LSEC antigen that is expressed on vascular but not on lymphoid ECs (98), pointed to LSECs as the predominant cellular site of hepatic mCMV latency.

FIG. 2.

Phenotyping of liver cells that carry latent viral DNA. (A) The latent viral genome localizes to nonparenchymal liver cells. At 9.5 months after sex-mismatched BMT and infection, DNA was prepared from 25 mg of unseparated liver tissue from three individual bone marrow chimeras (mice 4 to 6), from 5 × 106 isolated hepatocytes (chimeras 7 to 9), and from NPLCs (chimeras 10 to 12). Note that techniques for optimizing the purity of hepatocytes and NPLCs are mutually exclusive. Latent viral DNA loads and chimerism were determined by qPCRs specific for the viral gene M55/gB and the allosomal cellular gene sry. (B) DNA load and chimerism in subsets of NPLCs. NPLCs were isolated from a pool of five livers, and CD4+, CD31+, CD106+, CD11b+, CD11c+, CD45R+, and CD146+ subsets thereof were purified by immunomagnetic cell sorting (MACS). DNA was prepared from 5 × 106 cells of each sorted subset, and genes M55/gB and sry were quantitated by qPCR for determining viral DNA load and chimerism. Throughout, dot symbols represent triplicate measurements from each sample and the short horizontal bars mark the median values. Negative data are indicated below the dotted line. Tapered wedges symbolize the proportions of donor (D)- and recipient (R)-derived cells.

Identification of CD31+ CD146+ LSECs as a cellular site of hepatic mCMV latency.

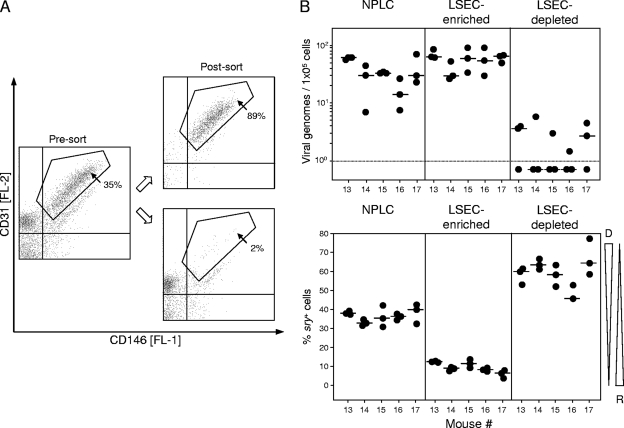

Since CD31 is a known marker for ECs, although not expressed exclusively by ECs (32, 78), it was at hand to suggest that the viral-genome-carrying, recipient-derived CD31+ NPLCs and CD146+ NPLCs defined above may actually be one and the same cell population, specifically, the LSECs. We therefore performed two-color cytofluorometric staining of NPLCs for the expression of CD31 and CD146, followed by cell sorting of a coexpressing CD31+ CD146+ population (Fig. 3). Besides this LSEC population, presort analysis also revealed NPLC subpopulations characterized by the phenotypes CD31+ CD146− and CD31− CD146−, which include CD31− stellate cells (116) and most leukocytes, as well as a minor subpopulation with the phenotype CD31− CD146low, which includes a subpopulation of CD49b+ NK cells (reference 98 and our own data not shown). The latent viral genome clearly copurified with the sorted CD31+ CD146+ population predominantly of the sry-negative genotype, whereas the different quantities of cells located outside the sorting gate and originating primarily from the donor collectively contained only trace amounts of viral genomes detected in some but not all replicate qPCRs of a sample. Since no physical separation method gives an absolute purity, the low numbers of viral genomes detected in the LSEC-depleted cell fraction may rather represent a contaminant of LSECs, which contain ∼100-fold-higher numbers of viral genomes. These findings were reproduced in five independent cell sorts performed with NPLCs derived individually from five latently infected mice (Fig. 3), and they confirmed a preceding sort experiment performed with NPLCs pooled from livers of three latently infected mice (data not shown). Finally, immunomagnetically purified CD146+ cells, which did not contain numerable numbers of CD11c+ DCs or CD11b+ macrophages (negative data not shown), were classified as LSECs functionally by their high endocytotic capacity to take up AcLDL (10, 12, 77, 82) ex vivo (Fig. 4A) as well as after a 24-h period in cell culture (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 3.

Purification of CD31+ CD146+ LSECs by two-color cytofluorometric cell sorting. (A) At 10 months after sex-mismatched BMT and infection, density gradient-enriched NPLCs derived from livers of five individual mice were separated by cytofluorometric cell sorting into CD146+ CD31+ LSECs and all remaining non-LSEC NPLCs. Shown are two-dimensional dot plots of CD31-stained and CD146-stained NPLCs of one representative mouse out of five mice tested, before (Pre-sort) and after (Post-sort) cell sorting. The presort dot plot represents a total of 6,676 cells, with 2,345 cells (35%) contained within the indicated sort gate and 4,331 cells outside of the sort gate. Postsort dot plots reveal the enrichment (upper plot) and the depletion (lower plot) of CD31+ CD146+ LSECs, respectively. Percentages indicate the proportions of cells within the indicated electronic gates. (B) For the five individually tested mice (mice 13 to 17), latent viral DNA loads and chimerism were determined by qPCRs specific for M55/gB and sry, respectively, in all NPLCs before cell sorting (NPLC fraction), in CD31+ CD146+ LSECs (LSEC-enriched fraction within the electronic gate), and in non-LSEC NPLCs (LSEC-depleted fraction outside the electronic gate). For the meaning of symbols, see the legend for Fig. 2.

FIG. 4.

Functional analysis of LSECs. (A) Immunomagnetically enriched ex vivo LSECs, with no prior cultivation, were incubated for 30 min with Dil-conjugated AcLDL and counterstained with FITC-conjugated anti-LSEC (anti-CD146) Ab. Cells were analyzed by two-color flow cytometry for endocytotic uptake of AcLDL (FL-2, carbocyanine dye Dil) and expression of CD146 (FL-1, FITC). (Left panel) Physical properties of LSECs as defined by size (forward scatter [FSC]) and granularity (sideward scatter [SSC]). The live gate for excluding dead cells and debris is indicated. (Right panel) Two-dimensional dot plot of AcLDL and CD146 staining of 30,000 cells analyzed, with 4,600 cells displayed as dots. Percentages of cells located in the four quadrants are indicated and reveal the purity of the LSEC preparation in the upper right quadrant. (B) Immunomagnetically enriched CD146+ LSECs were cultured for 24 h in the presence of 1.5 μg BODIPY FL-labeled AcLDL. The endocytotic activity of LSECs was determined by the uptake of AcLDL visualized by fluorescence microscopy with green cytoplasmic staining for AcLDL and blue staining of cell nuclei by Hoechst dye 33342. The bar marker represents 20 μm.

Donor-derived MHC-II+ cells expressing the LSEC antigen CD146 do not harbor the latent viral genome.

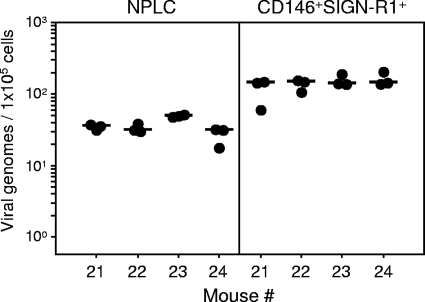

The cell surface marker phenotype of LSECs is debated in the literature (for a review, see reference 33). Whereas LSECs were reported to constitutively express MHC-II as well as CD11c, sharing these markers with DCs (reviewed in references 57 and 67), Katz and colleagues presented conflicting results showing low or absent expression of both MHC-II and CD11c by LSECs (50). To make confusion perfect, Onoe and colleagues (79) concluded that murine LSECs express MHC-II but not CD11c. Importantly, as shown above (Fig. 2), in our model, CD11c+ cells were primarily donor derived and did not carry latent viral DNA, which excludes DCs as well as putative CD11c+ LSECs from the list of candidates. In our hands, and in agreement with Katz and colleagues (50), immunomagnetically purified CD146+ cells all coexpressed high levels of CD31 but failed to coexpress CD4, CD45R, and CD11c (negative data not shown); yet, a small subset of the cells indeed expressed MHC-II (Fig. 5A), in accordance with the work of Onoe et al. (79). Since various MHC-II-negative cell types conditionally express MHC-II upon activation by cytokines, by gamma interferon in particular (106), we surmised that the MHC-II+ CD146+ cells may not represent an independent cell population but rather LSECs in a state of activity, which might in part explain the different findings in the literature. This assumption, however, proved to be wrong. Cytofluorometric cell sorting of immunomagnetically enriched CD146+ cells into MHC-II+ and MHC-II− subsets (Fig. 5A) revealed a clear-cut distinction in that the MHC-II− cells were in the majority sry negative and thus recipient derived, whereas the MHC-II+ cells were for the most part of the sry+ genotype and thus donor derived (Fig. 5B). Importantly, the latent viral DNA localized primarily to the recipient-derived MHC-II− population of LSECs (Fig. 5C). Since our interest was focused on the cellular site of mCMV latency in the liver, we did not here further investigate the precise nature of the donor-derived MHC-II+ CD146+ population.

FIG. 5.

The latent viral genome localizes to CD146+ MHC-II− cells of recipient origin. (A) Immunomagnetically enriched CD146+ cells derived from livers of latently infected bone marrow chimeras at 11 months after sex-mismatched BMT and infection were separated into CD146+ MHC-II− and CD146+ MHC-II+ subsets by two-color cytofluorometric cell sorting. Shown are two-dimensional dot plots of MHC-II-stained and CD146-stained LSECs of one representative mouse out of three mice tested, before (Pre-sort) and after (Post-sort) cell sorting. The presort dot plot represents a total of 7,524 cells, with 6,089 cells (81%) within gate 1 (G1) representing CD146+ MHC-II− cells and 752 cells (10%) within gate 2 (G2) representing CD146+ MHC-II+ cells. Postsort dot plots reveal the purity of the sorted subsets. Percentages reveal the proportions of cells contained within the indicated electronic gates. (B and C) Chimerism (B) and latent viral DNA loads (C) determined for three individually tested mice (mice 18 to 20) by qPCRs specific for sry and M55/gB, respectively, in all immunomagnetically enriched cells before cytofluorometric cell sorting (CD146+ fraction) as well as in sorted cells of G1 (CD146+ MHC-II− fraction) and G2 (CD146+ MHC-II+ fraction). For the meaning of symbols, see the legend for Fig. 2.

The latent viral genome localizes to CD146+ cells coexpressing the murine homolog of L-SIGN.

Whereas LSECs quantitatively dominate the hepatic EC population, most cell surface markers are shared between microvascular LSECs and conventional ECs of the liver macrovasculature. As discussed in the critical review article by Elvevold and colleagues on the controversial identity of LSECs (33), the human C-type lectin L-SIGN, a homolog of DC-SIGN also known as DC-SIGN-related molecule DC-SIGNR, is strongly and constitutively expressed on LSECs and lymph node endothelium but not on DCs, other hepatic cells, or other endothelia. As shown by Geijtenbeek and colleagues (38), the murine DC-SIGN homolog mSIGN-R1 is more closely related to L-SIGN than to DC-SIGN itself because it is specifically expressed by LSECs and not by DCs and may thus be referred to as murine L-SIGN (mL-SIGN).

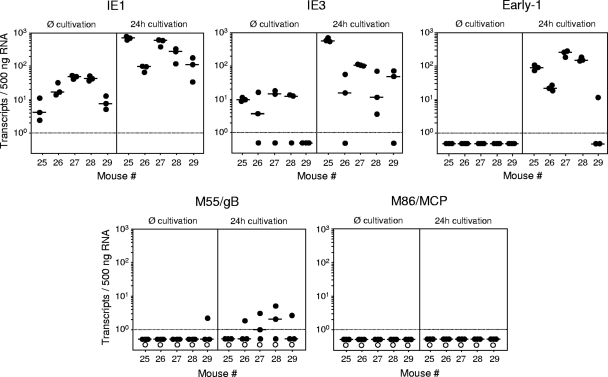

It was therefore of interest to use ml-SIGN (mSIGN-R1) in combination with the LSEC antigen CD146 to distinguish between LSECs and conventional ECs. It is instructive to recall that, unlike mL-SIGN, CD146 is not expressed on lymph node endothelium (98), so that coexpression of these two markers simultaneously excludes lymphoid ECs and conventional ECs. As shown in Fig. 6, by M55/gB-specific qPCR after two-color cytofluorometric cell sorting, the latent viral genomes localize to mL-SIGN+ CD146+ cells, which further supports the conclusion that LSECs harbor the latent viral DNA. It should be noted that these cells were genotyped as sry−, that is, as recipient derived (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Detection of latent viral genomes in LSECs coexpressing CD146 and the murine homolog of L-SIGN. CD146+ SIGN-R1+ LSECs were purified from density gradient-enriched NPLCs, followed by two-color cytofluorometric cell sorting. NPLCs were derived from mouse livers at 12 months after sex-mismatched BMT, and cell sortings were performed individually for four latently infected chimeras (mice 21 to 24). Viral genomes were quantitated by M55/gB-specific qPCR in NPLCs prior to cell sorting (left panel) as well as in sorted CD146+ SIGN-R1+ LSECs derived thereof (right panel). Note that sorted cells were mostly of the sry− genotype and thus recipient derived (data not shown). Filled circles represent triplicate qPCR data for each sample DNA preparation normalized to 1 × 105 cells. Median values are indicated by short horizontal bars.

In summary of the series of phenotyping studies, mCMV latency is established primarily in the recipient-derived population of MHC-II− CD11b− CD11c− CD31+ mL-SIGN+ CD146+ LSECs.

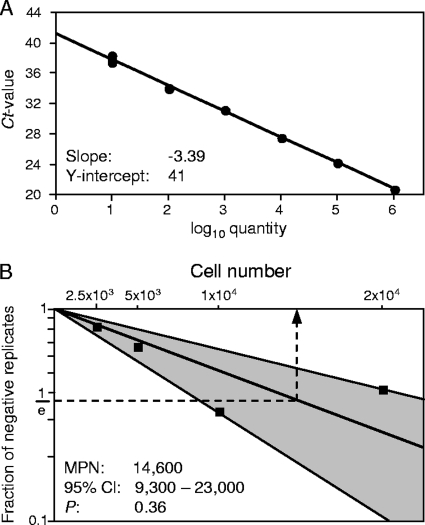

Viral gene expression in latently infected LSECs is limited to IE genes.

By definition, viral latency implies the absence of virus production (96) but does not exclude limited transcriptional activity by temporary desilencing of certain viral genes. As shown previously for mCMV latency in the lungs, the major IE (MIE) locus is sporadically active during latency without further progression in the productive transcriptional program (40, 62; reviewed in reference 93). Since such a transcriptional activity is relevant to immune control of latency by peptide-specific CD8 T cells (100), we tested transcription in purified CD146+ LSECs derived from five latently infected XY-XX chimeras individually either directly after the ex vivo purification or after a 24-h period in cell culture (Fig. 7). In the ex vivo samples, IE1 and IE3 transcripts, which are generated from a common precursor transcript by differential splicing (51, 52, 74), were detected in various quantities in LSEC preparations from all five and from four out of five mice, respectively. Despite the presence of IE3 transcripts encoding the essential transactivator of early (E)-phase gene expression (4, 74), the transcriptional program did not proceed to the E1/M112-M113 transcript (17, 24), and accordingly, the E-phase M55/gB and the late-phase M86 transcripts were undetectable.

FIG. 7.

Viral gene expression in latently infected LSECs ex vivo and after cultivation. Immunomagnetically enriched CD146+ LSECs were separately prepared from livers of five latently infected mice (mice 25 to 29) at 11 months after sex-mismatched BMT and infection and were tested for viral transcripts either directly ex vivo (Ø cultivation) or after a 24-h period of cultivation (24h cultivation). Highly purified, DNA-free total RNA was prepared from 4 × 106 LSECs, and triplicate 1/25 aliquots of each sample were used for the absolute quantitation of IE1, IE3, E1, M55/gB, and M86/MCP transcripts by the respective gene-specific RT-qPCRs using corresponding synthetic transcripts as standards. The experimentally determined numbers of transcripts were normalized to 500 ng of total RNA. Dot symbols represent triplicate measurements for each sample, with the median values marked by short horizontal bars. Negative data are indicated below the dotted line. Since genes M55/gB and M86/MCP have no exon-intron structure, PCRs were performed also with no RT (open circles) to control for amplification from contaminating DNA and were found to be negative throughout.

Latently infected LSECs proceed to E-phase gene expression upon cultivation.

A 24-h period in cell culture enhanced IE transcription and induced a progression to E1 transcription in LSECs from four out of five mice tested, and threshold amounts of the M55/gB transcripts were detected in the cell cultures occasionally (Fig. 7). In contrast, true late M86 transcripts encoding the essential MCP (107) remained absent throughout, so that virus capsid assembly could not take place. Consequently, complete reactivation to infectious virions did not occur in cell cultures of latently infected LSECs (negative data not shown).

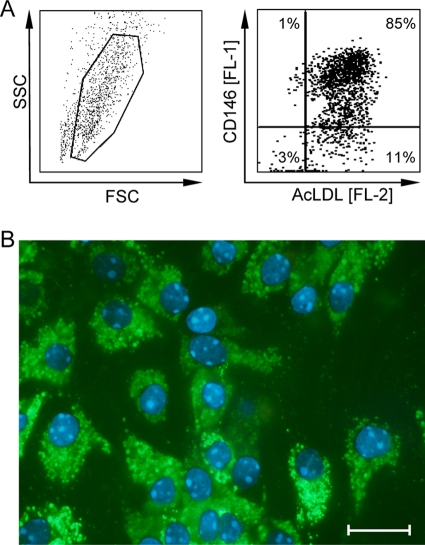

Frequency of latently infected LSECs and copy number of the latent viral genome.

A limiting dilution approach was used to determine the frequency (minimum estimate) of viral-genome-carrying, latently infected cells present in a population of purified CD146+ LSECs. Graded numbers of cells in 12 replicates were subjected to M55/gB-specific qPCR using plasmid pDrive_gB_PTHrP_Tdy as the standard (101). The cutoff cycle threshold value for distinguishing between viral-DNA-negative and -positive samples was defined by extrapolation of the standard curve to one template and was found to be 41 (Fig. 8A). Accordingly, samples were classified as negative samples when no signal was obtained after 41 amplification cycles. The frequency estimate (MPN for a λ of 1) was then obtained from the proportions of negative samples according to the Poisson distribution equation and was found to be 1 latently infected cell in 14,600 (95% CI, 9,300 to 23,000) LSECs (Fig. 8B).

FIG. 8.

Frequency of LSECs carrying latent viral genomes. Limiting dilution analysis of immunomagnetically enriched CD146+ LSECs by M55/gB-specific qPCR was used to estimate the frequency of LSECs that carry latent viral DNA. (A) Standard curve for the quantitation of M55/gB by qPCR using log10-graded numbers of linearized plasmid pDrive_gB_PTHrP_Tdy as templates. The y-axis interception (one DNA molecule) of the extrapolated regression line reveals a cutoff cycle threshold (Ct) value of 41 cycles. Accordingly, experimental samples are classified as samples negative for viral DNA when no signal was obtained after 41 amplification cycles in the qPCR. (B) Graded numbers of LSECs derived from a pool of livers of three latently infected BALB/c mice at 8 months after sex-mismatched BMT and infection were tested in 12 replicates for the presence of viral DNA. The frequency estimate is based on the experimentally determined fractions of negative replicates. The log-linear plot shows the Poisson distribution graph and its 95% CI (shaded area) calculated by the maximum-likelihood method. The MPN, which is the reciprocal of the frequency, is revealed as the abscissa coordinate (dashed arrow) of the point of intersection between 1/e and the calculated regression line. It gives us the number of cells containing, on average, one latently infected cell. P, probability value indicating the goodness of fit.

With this information and based on the latent viral genome load determined by qPCR for the very same LSEC preparation (mean, 593; 95% CI, 427 to 760 genomes per 106 cells; six test samples), it became possible to calculate the average number of viral genomes per latently infected LSEC as 9 (range, 4 to 17).

Virus can reactivate in lung explant cultures after LSEC transfer.

As shown in Fig. 1C, latent mCMV can reactivate in liver explant cultures, and in general, tissue explants have long been known to provide a supporting microenvironment for efficient virus reactivation (20, 49, 114). Although we have so far demonstrated the presence of latent viral DNA in LSECs, there remained the question of whether these genomes were fully intact and accounted for the reactivation observed in unseparated liver explants, as only this fulfills the definition of latency in LSECs.

We approached this problem by intravenous adoptive transfer of purified CD146+ LSECs, which were derived from latently infected BALB/c mice after sex-mismatched BMT, into immunocompromised and uninfected female BALB/c recipients (Fig. 9). Since transferred LSECs are mostly trapped in the vascular bed of the lungs at 24 h after transfer, as revealed with normal, male LSEC donors by sry-specific qPCR in female recipients (data not shown), virus reactivation was studied in lung explant cultures with the hope that the heterologous environment of lung tissue would also support virus reactivation in LSECs. Specifically, two indicator recipients each received 2 × 107 purified LSECs, the highest feasible cell dose for transfer, whereas four control recipients each received 2 × 107 NPLCs depleted of LSECs from the very same latently infected donors. At 24 h after the cell transfer, lungs of the recipients were each subdivided into 48 tissue pieces and plated into two 24-culture plates (Fig. 9A). It was not before week 5 after explantation that infectious virus became detectable in a total of 3 out of 96 cultures in the LSEC group, whereas during the observation period of 8 weeks, no reactivation was observed in the total of 192 explant cultures of the LSEC-depleted NPLC control group. Importantly, whereas reactivation was observed in explants from both recipients of LSEC-enriched NPLCs, no reactivation was observed in explants from four recipients of LSEC-depleted NPLCs (Fig. 9B). According to Fisher's exact probability test (Fig. 9C1), the difference between the two groups is significant, with a P value of 0.036 (two-sided). This means that reactivation occurred more frequently from purified LSECs than from all the remaining NPLCs in an LSEC-depleted population.

FIG. 9.

Virus reactivation from latently infected LSECs by cell transfer and tissue explantation. (A) Experimental regimen. Immunomagnetically LSEC (CD146+)-enriched and LSEC (CD146+)-depleted NPLCs derived from pooled livers of three latently infected BALB/c donor mice at 8 months after sex-mismatched BMT and infection were transferred intravenously (i.v.) into CMV-naïve, immunocompromised (6.5 Gy of gamma irradiation 24 h before cell transfer) female BALB/c recipients. Of each population, 2 × 107 cells were transferred per recipient mouse. At 24 h after cell transfer, recipients' lungs were each cut into 48 pieces and the explants were kept in culture for 8 weeks, with weekly monitoring for the occurrence of infectious virus in the culture supernatants. (B) Reactivation incidences in 96 and 192 explant cultures from two and four recipients of LSEC-enriched and LSEC-depleted NPLCs, respectively. (C1) Two-by-two contingency tables (observed-value table and table of values expected according to the null hypothesis of random distribution) for significance analysis using Fisher's exact test. (C2) Two-by-two contingency tables (observed and expected values) under the rebuttable presumption that reactivation in the LSEC-enriched fraction resulted exclusively from contaminating 5% (worst-case assumption) of non-LSEC NPLCs. Differences between observed- and expected-value tables are considered significant for a P of <0.05 (two-sided).

The LSEC preparations regularly contained <5% non-LSEC NPLCs. So, if one argues as a counterhypothesis that the three observed reactivation-positive lung pieces in the LSEC transfer group, which according to the Poisson distribution equals three reactivation events, rather came from 5% contaminating non-LSEC NPLCs, which is a worst-case assumption, an extrapolated number of 60 reactivations should have occurred in 96 explants from an LSEC-depleted NPLC preparation. Since, according to the Poisson distribution, more than one reactivation could occur from any of the plated lung pieces, 60 postulated reactivations should have led to 45 virus-positive lung explant cultures out of 96 cultures tested, instead of none in 192 cultures, as was actually observed. The probability for observing such a difference by chance (null hypothesis) is zero (Fisher's test, P < 10−10, two-sided) (Fig. 9C2). These findings and statistical considerations strongly support the conclusion that reactivation originated from LSECs.

These data also allow us for the first time to give a minimal estimate of the frequency of reactivations. According to the measured frequency of viral-genome-carrying LSECs (Fig. 8), a total of 4 × 107 transferred LSECs contained 2,740 (95% CI, 1,740 to 4,300) latently infected cells, which led to three reactivations. Thus, the frequency of latently infected LSECs in which virus reactivated was in the region of 1 in 1,000, that is f is approximately 10−3, under the specific conditions of the experimental model studied here.

Altogether, these data have identified LSECs as the main cellular site of reactivatable mCMV latency in the liver.

DISCUSSION

LSECs are a highly interesting cell population constituting the interface between the microvascular sinusoidal compartment of the liver and the liver parenchyma. LSECs sense pathogens through Toll-like receptors and interact with passenger lymphocytes. Notably, they can act as antigen-presenting cells but induce tolerance of T cells instead of effector functions to avoid immunopathological inflammation that would interfere with their physiological scavenger function (reviewed in reference 57).

The fact that mCMV targets LSECs during an acute infection in vivo was shown recently by cell-type-specific recombination of a fluorescence (enhanced-green fluorescence protein [EGFP])-tagged reporter virus expressing EGFP upon removal of a loxP-flanked transcriptional stop sequence in Cre-transgenic mice expressing Cre under the control of a cell-type-selective promoter (97). Specifically, recombination in Tie2-cre or Tek-cre mice, which express Cre selectively in vascular but not in lymphoid ECs (26), led to the coexpression of EGFP and intranuclear viral IE1 protein in cells of EC morphology, identified as LSECs by their expression of CD31 and LYVE-1 combined with their localization in sinusoids distant from macrovascular vessels. Although virus recombined in LSECs of Tie2-cre mice was in principle able to spread to neighboring hepatocytes, the amount of virus released by LSECs was very low and contributed little to the overall virus production in the liver. In contrast, reporter virus that recombined selectively in hepatocytes of Alb-Cre mice accounted for almost all of the virus production in the liver (97). Importantly, LSECs have no effective barrier function against mCMV infection of the liver, and a replication passage through LSECs is not required (97) since the virus can reach the hepatocytes directly, probably via the fenestrae in the discontinuous sinusoidal endothelium (15). Transcytosis of LSECs (109), as suggested for other hepatotropic viruses (16, 28), does not appear to be a relevant mechanism for mCMV since, in most organs, floxed reporter virus failed to traverse endothelia of Tie2-cre mice without being recombined (97).

As we have shown here, LSECs are a site of mCMV latency, whereas hepatocytes are not. In agreement with previous conclusions (8, 11), this shows clearly that establishment of latency is not positively correlated with virus productivity in a certain cell type, although the overall virus production in the host is likely of importance for efficient virus dissemination to the cellular sites of latency and thus determines the gross load of latent viral genomes in host tissues (25, 91). That latency is not established in hepatocytes may relate to the fact that the infection is highly cytopathogenic in this cell type, leading to cell destruction and large plaque-like lesions in the liver parenchyma (45). LSECs, in contrast, are ideal candidates for latency due to their very limited virus productivity (97). This reduces cytopathogenicity but, unlike with nonproductive infection of nonpermissive cell types, maintains the potential for reactivation to a low-level productive infection, in accordance with the classical definition of herpesviral latency given by Roizman and Sears (96).

Another feature of ECs that favors them for latency is their very low turnover, although to our knowledge there exist no data specifically for the microvascular LSECs. As far as macrovascular ECs are concerned, they are among those cells exhibiting the lowest proliferation level in the body, with only 0.01% of cells engaged in cell division at any time (80). Using hematopoietic chimeras, Crosby and colleagues (30) have determined that only 0.2% to 1.4% of the vascular ECs were derived from donor hematopoietic progenitors within 4 months after irradiation and hematopoietic recovery. This may explain also why we observed that MHC-II− CD146+ LSECs in the latently infected XY-XX chimeras at 12 months after BMT were primarily recipient derived, although the literature provides reasonable evidence to suggest that ECs, including LSECs, are descendants of bone marrow-derived hemangioblastic endothelial progenitor cells involved in maintenance angiogenesis and liver regeneration (5, 22, 36, 37, 43, 108). As additional evidence for a hematopoietic origin of LSECs, the murine hematopoietic stem cell marker Sca-1 (Ly-6A/E) was found to be constitutively expressed on murine LSECs (70). In accordance with a low rate of LSEC replacement after BMT, our data also show a low but nonnegligible proportion (up to 10%) of donor-derived sry+ LSECs, with some variance between individual mice (Fig. 3B and 5B). Alternatively, predominance of the recipient genotype in LSECs of BMT chimeras may reflect endogenous regeneration from a liver-resident endothelial progenitor cell, an argument that is supported by the fact that the liver has a hematopoietic function in ontogenesis and establishes microchimerism after transplantation (discussed in reference 57). Whatever mechanism applies, our data have shown that more than 90% of MHC-II− CD146+ LSECs are recipient derived during mCMV latency many months after BMT, so that replacement with the progeny of donor-derived endothelial progenitor cells must be a very slow process. Since the frequency of latently infected LSECs is rather low, however, we cannot formally exclude the possibility that the latent viral genome resides in the minor fraction of donor-derived LSECs, although we currently see no rationale for the speculation that only donor-derived and not recipient-derived LSECs support latent infection, in particular since liver-resident LSECs are rapidly targeted by mCMV during acute infection before hematopoietic reconstitution can replace recipient-derived LSECs with donor-derived LSECs.

Isolation of LSECs gave us for the first time an opportunity to estimate the frequency of latently infected tissue-resident host cells and to determine the latent viral genome copy number per latently infected cell. The frequency of latently infected LSECs among total LSECs was found to be in the region of 10−4 (0.01%) under the conditions of the model studied here. It is important to emphasize that the precise number is not a fixed value but certainly depends on the degree of virus dissemination during acute infection, which determines the overall load of latent viral DNA in host tissues (91). Nevertheless, the order of magnitude was found to be the same for hCMV latency in hemopoietin-mobilized mononuclear cells from healthy individuals undergoing natural latent infection, namely, 0.004 to 0.01% (102). Based on the latent viral DNA load determined here for the liver, the average copy number of latent viral genomes per latently infected LSEC was in the region of 10 copies, specifically 9 and ranging from 4 to 17. This appears to be a more or less fixed value for latent CMVs, because similar copy numbers of latent viral episomes (14) were estimated for hCMV latency in hemopoietin-mobilized mononuclear cells ex vivo and in cultured granulocyte-macrophage progenitors, namely, 2 to 13 genomes and 1 to 8 genomes, respectively (102). Similarly, Pollock and colleagues found that peritoneal-exudate macrophages can harbor latent mCMV with a frequency of ∼1 in 50,000 cells (0.002%) and a copy number of 1 to 10 per cell (85). Thus, strikingly, both the frequency of latently infected cells and the copy numbers of latent viral genomes were in comparable ranges in such different cell types and across CMV and host species.

These copy numbers in latency are actually astoundingly high, since at least during acute infection in vivo, the probability for ∼10 virus hits per latently infected cell is very low, in particular if we consider the low prevalence of latently infected cells. Why should a latent viral genome accumulate in so few cells of a certain cell type by random hits? Although we do not know how many viral genomes reach the cell nucleus during acute infection of a cell in vivo, there is evidence to suggest that productive infection usually initiates monoclonally from a single successful viral genome. Specifically, two-color in situ viral DNA hybridization of liver tissue sections after intravenous coinfection of mice with equal doses of different mCMV variants, for instance, wild-type or revertant virus and a replication-competent mutant virus, almost exclusively revealed distinct foci of infection of either color (41). In hepatocytes, lack of cytokinesis after mitosis can lead to cells with two nuclei. Most impressively, cases in which wild-type virus replicated in one nucleus and mutant virus in the second nucleus of such binuclear hepatocytes were occasionally observed (90). Only after coinfection of mice with wild-type virus and a replication- or dissemination-deficient mutant virus was an increased incidence of cellular coinfection observed due to the selective force on the mutant (23). Coinfection indicates that oligoclonal virus replication can indeed occur in individual cell nuclei, but apparently this is the exception rather than the rule.

We can discuss two possibilities. One is that viral genomes enter the cell nucleus by random hits and remain silenced during acute infection. The problem is that we currently cannot explain the relatively high average copy numbers. Alternatively, and actually more likely, latent viral genomes might be derived from a single hit or a few hits by amplification through DNA replication, as proposed already by Roizman and Sears for herpes simplex virus latency in neurons (96). The question remains, however, why this postulated amplification leads to only about 10 and not many more copies, as would be the case in productive infection.

As we have documented previously for the model of mCMV latency in the lungs (reviewed in reference 93), not all latent mCMV genomes are transcriptionally silent at any time. Instead, a few viral genomes are desilenced at the MIE locus and generate spliced MIE transcripts IE1 and IE2, but not usually IE3 (40, 62). Notably, whereas recent work has shown that the IE1 protein is dispensable for the reactivation of latent mCMV (18), the IE3 transcript encodes a transactivator protein that is essential for downstream E-phase gene expression and thus for viral replication (4, 74). Upon stimulation of the MIE enhancer by tumor necrosis factor alpha, however, alternative splicing of the IE1-IE3 precursor transcript to IE3 mRNA was induced; nevertheless, viral gene expression did not advance to the expression of the essential M55/gB transcript, and consequently, latency was maintained (101). From this, it was proposed that multiple molecular checkpoints control latency. This situation is precisely what was found here for ex vivo-purified LSECs. Although IE1 and IE3 transcripts were present, viral gene expression did not proceed to the generation of M112-M113 (E1), M55 (gB), and M86 (MCP) mRNA, so that infectious virions could not be produced. Interestingly, although a 24-h cultivation of LSECs advanced reactivated viral gene expression to E1 and gB mRNA, the replicative cycle could not be completed because MCP was not expressed, so that viral nucleocapsids could not assemble. It should be noted that attempts to enforce virus reactivation in cultured LSECs by treatment with gene-desilencing drugs such as the histone deacetylase inhibitors trichostatin A (115), sodium butyrate (61), and valproic acid (39) all failed (data not shown). The identification of a further, so-far-unknown, checkpoint between gB and MCP provides additional evidence in support of the multiple-checkpoint model of latency and reactivation (63; reviewed in reference 93).

There remained the question of whether full reactivation to virus recurrence can occur at all from LSECs, a question that is crucial for defining LSECs as a cellular site of latency and reactivation rather than as nonproductive, viral-DNA-harboring cells. In fact, to our knowledge, previous work documenting the presence of viral DNA in ECs (see the introduction) has not documented productive virus reactivation specifically from ECs. Indeed, this is not at all trivial to prove, since the usual regimes for inducing virus recurrence, namely, in vivo immunodepletion or tissue explantation (for reviews, see references 47 and 92) can, obviously, not identify the cell type. Furthermore, although infectious virus could be recovered from latently infected host tissues by these reactivation protocols, the actual frequency of cells in which virus reactivated necessarily remained unknown. As suggested by the model of mCMV reactivation in the lungs following total-body gamma irradiation, the strongest in vivo inducer known so far, most transcriptional reactivations still stop at downstream checkpoints, and only few reactivation events progress to the release of infectious virus (63).

We approached this problem by intravenous adoptive transfer of purified LSECs, which were derived from latently infected donor mice, into CMV-naïve recipient mice, so that reactivation could originate only from the transferred cells. As every physical purification of cells includes contaminating other cell types, it was decisive to transfer LSEC-depleted NPLCs as a control. While no reactivation was observed from non-LSEC NPLCs, the frequency of reactivation in the transferred LSEC population was found to be in the range of 10−7 relative to all LSECs and 10−3 relative to the fraction of LSECs harboring latent viral DNA. This is a minimum estimate, since not all transferred LSECs are trapped in the lungs and since no one can know if explanted lung tissue provides the optimal microenvironment for virus reactivation from trapped LSECs. In any case, these data have shown with statistical significance that virus reactivates more frequently from an LSEC-enriched NPLC population than from an LSEC-depleted NPLC population. These functional reactivation data, combined with the localization of the viral DNA, identified LSECs as a cellular site of reactivatable mCMV latency in the liver.

Conclusion.

Like in the cell-type-specific Cre-inducible reporter virus recombination (97) discussed above, small amounts of LSEC-derived reactivated virus associated with little-to-no cytopathogenicity might spread to more productive neighboring cell types, which then account for bulk virus recurrence. Thus, in liver transplantation, reactivation may be initiated in the sinusoidal endothelium, from which the virus can spread to hepatocytes, leading to cytopathogenic parenchymal infection and ultimately to graft failure.

Acknowledgments

We thank Steffen Schmitt and Julia Altmaier (FACS Core Facility) for performing cytofluorometric cell sorting and the CLAF team for animal care. In the beginning of the project, the LSEC-specific Ab ME-9F1 was generously supplied by Alf Hamann, Charité University Medicine, Berlin, Germany.

Extramural support was provided by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, SFB 490, individual project E2. Special thanks go to the Dr. Hans-Joachim and Ilse Brede Stiftung for a generous donation.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 17 June 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agresti, A. 1992. A survey of exact inference for contingency tables. Stat. Sci. 7131-177. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alterio de Goss, M., R. Holtappels, H.-P. Steffens, J. Podlech, P. Angele, L. Dreher, D. Thomas, and M. J. Reddehase. 1998. Control of cytomegalovirus in bone marrow transplantation chimeras lacking the prevailing antigen-presenting molecule in recipient tissues rests primarily on recipient-derived CD8 T cells. J. Virol. 727733-7744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ambion. 2009. MEGAscript™ high yield transcription kit instruction manual (manual version 0209). Ambion, Austin, TX.

- 4.Angulo, A., P. Ghazal, and M. Messerle. 2000. The major immediate-early gene ie3 of mouse cytomegalovirus is essential for viral growth. J. Virol. 7411129-11136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asahara, T., H. Masuda, T. Takahashi, C. Kalka, C. Pastore, M. Silver, M. Kearne, M. Magner, and J. M. Isner. 1999. Bone marrow origin of endothelial progenitor cells responsible for postnatal vasculogenesis in physiological and pathological neovascularization. Circ. Res. 85221-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]