Abstract

A recent genomewide screen identified 13 transposable elements that are likely to have been adaptive during or after the spread of Drosophila melanogaster out of Africa. One of these insertions, Bari-Juvenile hormone epoxy hydrolase (Bari-Jheh), was associated with the selective sweep of its flanking neutral variation and with reduction of expression of one of its neighboring genes: Jheh3. Here, we provide further evidence that Bari-Jheh insertion is adaptive. We delimit the extent of the selective sweep and show that Bari-Jheh is the only mutation linked to the sweep. Bari-Jheh also lowers the expression of its other flanking gene, Jheh2. Subtle consequences of Bari-Jheh insertion on life-history traits are consistent with the effects of reduced expression of the Jheh genes. Finally, we analyze molecular evolution of Jheh genes in both the long- and the short-term and conclude that Bari-Jheh appears to be a very rare adaptive event in the history of these genes. We discuss the implications of these findings for the detection and understanding of adaptation.

Keywords: adaptation, transposable elements, Drosophila, purifying selection, life-history traits

Introduction

Transposable elements (TEs) were once considered to be intragenomic parasites leading to almost exclusively detrimental effects to the host genome (Doolittle and Sapienza 1980; Orgel and Crick 1980; Charlesworth et al. 1994). However, there is growing evidence that TEs sometimes contribute positively to the function and evolution of genes and genomes (Kidwell and Lisch 2001; Daborn et al. 2002; Kazazian 2004; Aminetzach et al. 2005; Biemont and Vieira 2006; Jurka et al. 2007). For example, TEs have contributed to the regulatory and/or coding sequences of a large number of genes (van de Lagemaat et al. 2003; Marino-Ramirez et al. 2005; Piriyapongsa et al. 2007; Feschotte 2008). Recently, the first comprehensive genomewide screen for recent adaptive TE insertions in the Drosophila melanogaster genome revealed that TEs are a considerable source of adaptive mutations in this species (González et al. 2008).

González et al. (2008) identified a set of 13 TEs that are likely to have contributed to the adaptation of D. melanogaster during its expansion out of Africa (David and Capy 1988; Lachaise et al. 1988). Two lines of evidence pointed to the adaptive roles of these 13 TEs: 1) the flanking regions of all of the investigated TEs (5 of 13) showed signatures of partial selective sweeps (Smith and Haigh 1974; Kaplan et al. 1988, 1989) and 2) eight of the 13 TEs showed higher frequency in a more temperate compared with a more tropical Australian subpopulation consistent with these TEs playing a role in adaptation to temperate climates. These 13 TEs represent a rich collection for follow-up investigations of adaptive processes in D. melanogaster.

The high rate of TE-induced adaptive changes reported by González et al. (2008) appeared to be incompatible with the low number of fixed TEs present in the D. melanogaster euchromatic genome. The authors suggested that most of these TEs represented local and ephemeral adaptations that were destined to be lost over long periods of time. It is possible then that the loci that are underlying much of the local adaptation over short periods of time would appear conserved when compared across species. If true, this would severely complicate the study of adaptation given that statistical inference of positive selection is often based on the assumption that adaptation is recurring at the same loci or even at the same sites (McDonald and Kreitman 1991; Jensen et al. 2007; Macpherson et al. 2007; Yang 2007). The adaptive TEs identified by González et al. (2008) constitute a good starting point to test whether recent adaptation takes place at loci that have shown historically high rate of adaptive divergence.

In this work, we analyzed one of these 13 TEs: FBti0018880, a full-length (1.7-kb) copy of a Tc1-like transposon that belongs to the Bari1 family (Caizzi et al. 1993). FBti0018880 is inserted in the 0.7-kb intergenic region between Juvenile hormone epoxy hydrolase 2 (Jheh2) and Jheh3 genes. Accordingly, we will refer to this insertion as Bari-Jheh for the remainder of this paper. Because these two genes have known functions, we can construct a plausible hypothesis about the possible phenotypic consequences of the insertion. Both genes code for enzymes involved in the degradation of Juvenile Hormone (JH). JH is a regulator of development, life history, and fitness trade-offs in insects (Flatt et al. 2005; Riddiford 2008). The multiplicity of biological effects of JH requires specific titers of the hormone during different times of the Drosophila development. The regulation of the JH titer is achieved by a balance between biosynthesis and degradation (de Kort and Granger 1996). Changes in the expression of Jheh genes are likely to affect JH titer and consequently any of the processes in which this hormone is involved. In Drosophila, these processes include metamorphosis, behavior, reproduction, diapause, stress resistance, and aging (Flatt et al. 2005).

We previously showed that the polymorphism pattern in the 2-kb region flanking Bari-Jheh is consistent with the expectations of a partial selective sweep and that Bari-Jheh affects the expression of Jheh3 (González et al. 2008). In this work, we expanded the analysis of the flanking region to include the whole coding sequence of the neighboring genes and performed additional allele-specific expression and phenotypic analyses. Altogether, we demonstrate that Bari-Jheh insertion is very likely to be an adaptive mutation. We also provide evidence suggesting that the adaptive insertion of Bari-Jheh is an extremely unusual event in the history of Jheh loci. We discuss the implications of these findings for the understanding of the adaptive process in Drosophila and the challenges that remain to associate Bari-Jheh insertion with the adaptively significant phenotype(s).

Materials and Methods

Drosophila Strains

Table S1 (Supplementary Material online) describes the D. melanogaster, Drosophila simulans, and Drosophila yakuba stocks used in this work.

Sequencing and Sequence Analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted using the DNeasy Tissue kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Based on the genome sequence of D. melanogaster, D. simulans, and D. yakuba (http://flybase.org), we designed primers in an overlapping fashion to amplify and sequence Jheh1, Jheh2, and Jheh3 genes. In D. simulans, the intergenic regions between these genes were also sequenced. The specific primers used for each species are given in supplementary table S2 (Supplementary Material online). Only D. melanogaster populations from Davis and Raleigh proved isogenic. For the rest of the strains, DNA was amplified using a proofreading DNA polymerase (Platinum Pfx; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and cloned into the Zero Blunt TOPO polymerase chain reaction (PCR) cloning kit (Invitrogen) before sequencing. All the sequences have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers GQ169144–GQ169226.

Drosophila melanogaster, D. simulans, and D. yakuba sequences available at http://flybase.org were also included in the analysis. For D. simulans, the genome sequence of six additional strains is available (Begun et al. 2007). However, most of the sequences had a poor quality and only North American (NA) strain w501 could be included in our analysis of the coding regions of Jheh1 and Jheh2 genes. Sequences were assembled using Sequencher 4.7 software (Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, MI), aligned with ClustalW (Thompson et al. 1994) and edited in MacClade (Maddison and Maddison 1989). Drosophila simulans intergenic regions were aligned using DIALIGN (Morgenstern 2004). The repetitive content of the intergenic regions was analyzed using RepeatMasker (available at http://www.repeatmasker.org).

We analyzed the polymorphism pattern of the 5-kb region flanking Bari-Jheh insertion in D. melanogaster by comparing several summary statistics calculated over the data sets to the distributions of these statistics obtained by neutral coalescent simulations as described in González et al. (2008). The demographic model specified in Thornton and Andolfatto (2006) was incorporated into the simulations. The population was partitioned into two subpopulations, the NA and the African (AF), and the sample was partitioned into two subsamples defined by the presence/absence of Bari-Jheh. We computed the pairwise nucleotide diversity (π) (Tajima 1983), the integrated haplotype score (iHS) (Voight et al. 2006) and the proportion of nucleotide diversity within the haplotypes linked to the TE to the total nucleotide diversity in the sample fTE = πTE/(πTE + πnon-TE) (Macpherson et al. 2007). Polymorphism data for D. simulans were analyzed using DnaSP 4.0 (Rozas et al. 2003).

Detecting Presence or Absence of Bari-Jheh

The presence/absence of Bari-Jheh in The Netherlands population was determined by PCR as described in González et al. (2008). The following primers were used: L: 5′-AGGGAGCCATCATTGTAATAGCG-3′, R: 5′-TTGTTGGCTTGTGGATTTCAAGT-3′, and FL: 5′-CCTACACGGCGAGAAGAGAAAAT-3′.

Analysis of the Molecular Evolution of Jheh Genes Using PAML Software

Sequences of the three Jheh genes in the 12 Drosophila species were provided by S. Chatterji (personal communication). For each gene, sequences were aligned using ClustalW (Thompson et al. 1994) and manually edited when necessary. We checked for duplications of these genes in each of the 12 Drosophila species using TblastX (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi).

We used PAML to estimate the degree of selective constraint (model M0) and to search for evidence of positive selection in the evolution of Jheh genes (models M7 and M8; Yang 2007). We first checked the congruence of the topologies of the gene and species tree. Phylogenetic trees for each of the three genes were built using MEGA 4 (Tamura et al. 2007). Although the topology for the species of the melanogaster and obscura group was the same, differences in the topology for the other branches of the tree were found between each of the three Jheh genes trees and the species tree. This result could be due to the saturation of substitutions at synonymous sites (Bergman et al. 2002). Consequently, we ran PAML using both the 12 species tree and the tree that included only the 6 species in the melanogaster group.

Reverse Transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) Analysis

A total of 50 4-day-old female adult flies, 50 third-instar larvae, and 0- to 18-h-old embryos were collected from one strain with the insertion (Wi3) and one strain without the insertion (Wi1). Total RNA from the three stages was isolated using the TRIzol protocol (Invitrogen). RNA was then treated with DNase and purified using RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen). First-Strand cDNA was synthesized using SuperScriptIII First-Strand synthesis system for RT-PCR (Invitrogen). To check for genomic contamination, RT-PCR reactions without retrotranscriptase were performed.

Specific primers for each of the three Jheh genes were designed and are given in supplementary table S3 (Supplementary Material online). For Jheh2 gene, three different sets of primers were designed. Primers Jheh2F and Jheh2R were designed in different exons to check for both genomic contamination and the presence of the two alternative transcripts described for this gene. Primers Jheh2-PA_F and Jheh2-PA_R specifically amplified transcript Jheh2-PA and primers Jheh2-PB_F and Jheh2-PB_R specifically amplified transcript Jheh2-PB. PCRs were run using Pfx polymerase (Invitrogen) and the following conditions: 94 °C for 4 min, 30 cycles of 94 °C 1 min, 55 °C 0.5 min, 68 °C 1 min, and one last extension step of 10 min at 68 °C.

Allele-Specific Expression Analysis

We looked for differences in expression between a Jheh2 allele carrying Bari-Jheh and a Jheh2 allele lacking Bari-Jheh in F1 heterozygous hybrids. We established two different crosses between one strain homozygous for the presence of Bari-Jheh (Wi3) and one strain homozygous for its absence (Wi1). In cross 1, the mother was homozygous for the presence of Bari-Jheh, and in cross 2, the father was homozygous for the presence of Bari-Jheh. These two reciprocal crosses allowed us to check for parental effects on the allele expression.

To check for differences in the level of expression between the alleles with and without Bari-Jheh, we identified a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the coding region of Jheh2 (position 1756; fig. 1) that is perfectly linked with Bari-Jheh (the allele carrying Bari-Jheh insertion has a C and the allele lacking Bari-Jheh insertion has a T). We used this SNP as the marker for allele-specific expression. Differences in expression between the two alleles were assayed in 3- to 5-day-old adults because the activity of JHEH increases during the first days after eclosion (Khlebodarova et al. 1996). For each cross, we collected males and females separately that were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until use. We have therefore a total of four samples: males and females progeny from cross 1 and males and females progeny from cross 2. We extracted RNA and synthesized cDNA from each of the four samples as explained above. We then used the cDNA as a template to amplify the diagnostic SNP using primers Jheh2F: 5′-TCGATAAGTTTCTGGTGCAGG-3′ and Jheh2R: 5′-CCGGAAAAAGTGAGGCTACAT-3′. A universal sequence was appended to Jheh2R primer for the subsequent pyrosequencing reaction. PCR was done in the presence of 2.5-μM tailed primer, 10-μM nontailed primer, and 10-μM universal biotin-labeled primer. We analyzed each sample in triplicate. The PCR product was then pyrosequenced to quantify the relative amount of C versus T in the cDNA (EpigenDx, Worcester, MA) using primers Jheh2R and Jheh2FS (TGGCGATTGGGGTTC).

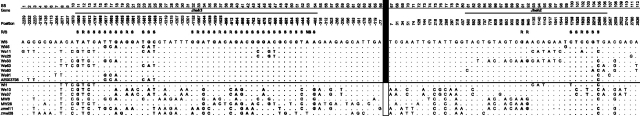

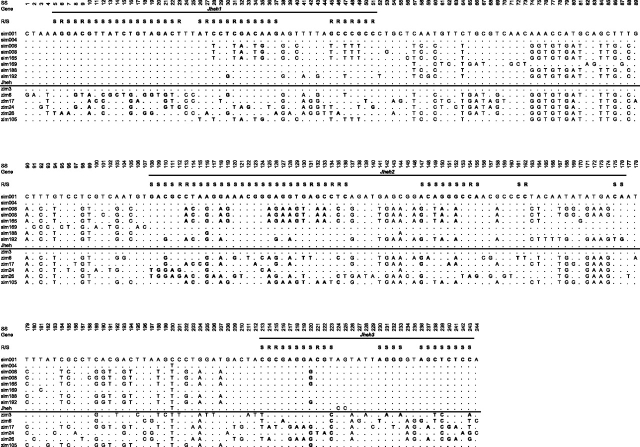

FIG. 1.—

Sequence of the 5-kb region flanking Bari-Jheh in Drosophila melanogaster (GQ169183--GQ169212). The figure shows the segregating sites number (SS), the genes associated with the insertion (Gene), and the distance from the insertion (Position). The SS within coding regions are in bold and are identified as replacement (R), synonymous (S), or nonsense (NS) polymorphisms. The TE is shown as a black rectangle; the absence of the TE is shown as an empty rectangle. A horizontal line separates the strains with the insertion from the strains without the insertion.

To correct for unequal amplification of the SNP not related to unequal transcription, we used the same primers to amplify genomic DNA of the F1 adults where the ratio is 50:50 (Wang and Elbein 2007). Before testing for statistically significant differences in the expression of the alleles with and without Bari-Jheh, data were transformed to fit a normal distribution using the arcsin transformation. Significance was then tested by an unpaired t-test because genomic DNA and cDNA come from different individuals

Phenotypic Assays

Introgressed Strains

We introgressed Bari-Jheh from two different NA strains, Wi3 and We33, into Wi1 strain. These three strains are isofemale strains that had been further put through 30–60 generations of brother–sister matings. In the first generation, we mated virgin females from Wi3 or We33 with Wi1 males. In the second generation, we backcrossed virgin F1 females with Wi1 males. In the subsequent generations, we individually mated 10 females with Wi1 males (one male and one female per vial). We identified the crosses that involved introgressed strains carrying Bari-Jheh by PCR using the primers L/R and FL/R described previously. After 8 generations for Wi3 stock and 11 generations for We33 stock, we carried out brother–sister matings and identified one strain that was homozygous for the presence of Bari-Jheh and one strain homozygous for the absence. We named the different lines as follows: Wi3/Bari+ and We33/Bari+ are both lines homozygous for the presence of the element and Wi3/Bari- and We33/Bari- are homozygous for the absence of the element.

We tested the isogenicity of the four introgressed strains through the analysis of TEs known to differ in their presence–absence pattern between the two parental strains. We tested 13 TEs for Wi3 introgression and 14 TEs for We33 introgression. The four introgressed stocks have the same presence–absence pattern for these TEs as the parental Wi1 strain suggesting that the genetic backgrounds of the four strains are very similar with the exception of the presence/absence of Bari-Jheh.

Egg-to-Adult Viability and Developmental Time (DT) Assays

We measured egg-to-adult viability and DT on normal food and on food containing a JH syntethic analog (JHa): methoprene (Sigma–Aldrich, St Louis, MO; 1 μg/μl in 95% ethanol). This JHa is widely used in insect physiology because it mimics JH action (Wilson and Fabian 1986; Riddiford and Ashburner 1991; Flatt and Kawecki 2007). First, we established Lethal Dose50 using six different concentrations of JHa: 0, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, and 3.5 μg/μl. JHa dissolved in ethanol was added to the still liquid, warm food medium to the desired final concentration. An equivalent volume of ethanol was added to the food without JHa. To set up the assay, we placed 100 adult flies (50 males and 50 females) of Wi1 strain into egg laying chambers overnight. The next day, eggs were allocated into 6 vials with normal food and 6 vials with food containing the different JHa concentrations, each vial with 50 eggs on 10 ml food (1 line × 6 conditions × 6 replicas = 36 vials). Vials were checked every 12 h for eclosing adults until all flies had emerged. The JHa concentration that gave approximately 50% mortality of the parental strain Wi1 was 2.5 μg/μl. For the subsequent assays, we used the parental strain Wi1 and the four introgressed strains. The experimental design followed was the same as explained before using normal food and food with three different concentrations of JHa: 0, 2.5, and 5 μg/μl (5 lines × 3 conditions × 6 replicates = 90 vials).

To estimate the egg-to-adult viability (proportion surviving), vials were checked every 12 h for eclosing adults until all flies had emerged. Average DT was estimated over the midpoint of each successive interval. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed using a nested model. We considered the identity of the introgressed strain as a nested factor and investigated the effect of the presence/absence of Bari-Jheh and the JHa concentration plus the interaction between these two factors. We tested whether strains with Bari-Jheh were significantly different from strains without Bari-Jheh by a Mann–Whitney test in the case of the viability experiments because the results were expressed in proportions and by a t-test for the DT results.

Results

Bari-Jheh Insertion is the Mutation Causing the Selective Sweep

We previously analyzed the haplotype configuration of the 2-kb region flanking Bari-Jheh insertion and found signatures of a partial selective sweep (González et al. 2008). Bari-Jheh was located in the center of the sweep and the analysis of 500-bp regions located approximately 10 kb away from Bari-Jheh showed that the haplotype structure was decaying on both sides of the insertion suggesting that Bari-Jheh was likely to be the causative mutation (González et al. 2008). However, it is theoretically possible that Bari-Jheh is in perfect linkage with a causative polymorphism located farther away from the 2-kb sequenced region. Furthermore, this region only included partial coding regions of Jheh2 and Jheh3 such that mutations in these genes could not be completely discounted as being the cause of the selective sweep. To test this possibility, we further sequenced the flanking region around Bari-Jheh to include the complete coding sequence of these two genes. As can be seen in figure 1, the TE appears to be completely linked to the partial sweep and the sweep decays on both sides of the TE further suggesting that the sweep has its focal point in or close to the element insertion. We estimated several statistical measures of polymorphism and compared them with the distributions obtained by coalescent simulations under the null model specified in González et al. (2008). This null model incorporates the demographic scenario based on the analysis of a European population described in Thornton and Andolfatto (2006). There is uncertainty about the appropriate demographic model both for European (Li and Stephan 2006; Thornton and Andolfatto 2006) and for NA populations (David and Capy 1988; Caracristi and Schlotterer 2003; Baudry et al. 2004). However, our aim in this work was to delimit the extent of the sweep, and to do this, we compared the significance of the statistics in the 5-kb region with the results previously obtained for the 2-kb region. Therefore, we used the same null model for both simulations (González et al. 2008). Results are shown in table 1. The proportion of nucleotide diversity within the haplotypes linked to the TE to the total nucleotide diversity in the sample, fTE, is not significant for the 2-kb region and as expected is not significant for the 5-kb region. On the other hand, the iHS statistic, which is expected to be the most powerful indicator of a partial selective sweep (Voight et al. 2006), is significant when we consider the 2 kb but not the 5-kb region immediately adjacent to Bari-Jheh. This result suggested that the mutation causing the sweep was included in this 5-kb region.

Table 1.

Neutrality Tests for the 5-kb Region Flanking Bari-Jheh Insertion

| Region Analyzed | fTE = πTE/π | iHS | πNA | πAF | πNA-TE | πNA-non TE |

| Bari-Jheh (5 kb) | 0.47 | 0.19 | 42.91 | 72.27 | 27.56 | 52.8 |

| 0.45 (0.22, 0.68) | −0.02 (−0.43, 0.38) | 28 (13, 43.9) | 85.5 (74.2, 96) | 25.3 (10.7, 41.1) | 26 (9.11, 48.2) | |

| 0.12 | 0.22 | 7.87 | 5.66 | 8 | 10.2 | |

| Bari-Jheh (2 kb)a | 0.12 | −1.79 | 24.24 | 103.2 | 8.7 | 63.19 |

| 0.31 (0.05, 0.61) | −0.21 (−0.86, 0.41) | 29.9 (7.85, 57.9) | 100 (84.8, 110) | 23.8 (3.62, 52.9) | 28.6 (3.16, 69.5) | |

| 0.15 | 0.33 | 12.8 | 7.66 | 12.8 | 18 |

NOTE.—Within a cell, the upper number is the observed value of the statistics. The middle number is the mean and the 2.5% and 97.5% confidence interval limits obtained by coalescent simulations. The lower number is the standard deviation. Data for the 2-kb region flanking the same insertion studied previously is shown for comparison.

We searched for mutations other than Bari-Jheh that could have been the target of selection. Besides Jheh2 and Jheh3 genes, we analyzed Jheh1. This gene belongs to the same gene family and is located only 0.6 kb downstream of gene Jheh2 and therefore approximately 3 kb away from Bari-Jheh (fig. 2). As can be seen in figures 1 and 2, the haplotype of one of the strains without Bari-Jheh (strain Wi1) is similar to that of the strains with Bari-Jheh and could represent the ancestral haplotype in which Bari-Jheh inserted. We conclude that Bari-Jheh is likely to be the causative mutation generating the partial selective sweep haplotype structure.

FIG. 2.—

Sequence of Jheh1 gene in Drosophila melanogaster (GQ169168–GQ169182). See figure 1 for details.

Bari-Jheh is present at high frequencies in both NA (93%) and Australian (55%) populations, whereas it is absent in the sampled sub-Saharan AF strains (González et al. 2008). Here, we further show that Bari-Jheh is present at high frequencies in Europe as well—we found that it is present in 11 of 12 strains from one population in The Netherlands. This result confirms that Bari-Jheh is present at high frequencies in geographically distant non-AF populations and is consistent with its adaptive role outside of Africa.

Bari-Jheh Affects the Expression of Its Neighboring Genes

We tested whether the presence of Bari-Jheh insertion is associated with the loss of expression of any of the three Jheh genes. We analyzed one strain with the insertion (Wi3) and one strain without the insertion (Wi1) in embryo, larvae, and adult. RT-PCR experiments revealed that the three genes are expressed in the three developmental stages in both the strains with and without the insertion. We could not detect one of the two predicted transcripts encoded by Jheh2 gene (Jheh2-PB) in any of the strains. However, the last release of Flybase (r5.13; www.flybase.org) eliminates this transcript and annotates a new one Jheh2-PC, which revealed that primers were designed in a noncoding region.

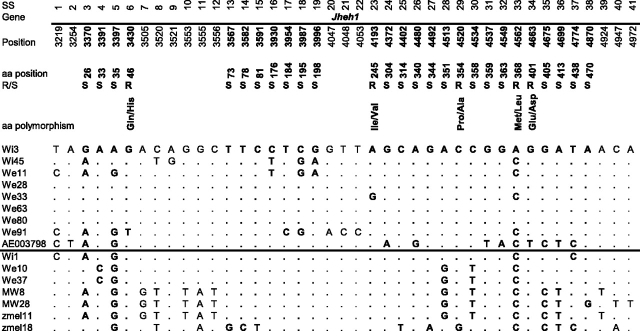

We further investigated whether Bari-Jheh affects expression of Jheh genes more qualitatively. We focused on the genes that are more closely linked to Bari-Jheh: Jheh2 and Jheh3. Previously, we used allele-specific expression analysis in F1 heterozygous hybrids adults (Wittkopp et al. 2004) to demonstrate that Bari-Jheh leads to reduced expression of the linked Jheh3 alleles (González et al. 2008). Here, we further analyzed the allele-specific expression of Jheh2 as a function of the presence or absence of Bari-Jheh (see Materials and Methods). Differences in the expression level between the two alleles under the same cellular conditions, as it is the case for F1 hybrids, indicate a difference in cis-regulatory activity (Wittkopp et al. 2004). Similarly to Jheh3, the expression of the Jheh2 allele linked to Bari-Jheh is downregulated (fig. 3). There is no evidence either for a parental effect or for a sex-specific effect on the expression of these alleles. The results were significant for the female progeny of the two crosses (t-test P value = 0.0031 and P value = 0.0002 for crosses 1 and 2, respectively) and for the male progeny of cross 2 (t-test P value = 0.024). Although results were not significant for the male progeny of cross 1 (t-test P value: 0.2680), the level of expression is similar to the male progeny of cross 2 (fig. 3).

FIG. 3.—

Normalized allelic ratios (allele carrying Bari-Jheh/allele lacking Bari-Jheh) for Jheh2 gene. Ratios for Jheh3 gene previously published are shown for comparison (González et al. 2008). The bars represent the mean of the ratios for the three replicas and the standard deviation. For each gene, the first two bars correspond to the F1 progeny (male and female, respectively) of cross 1 and the last two bars correspond to the progeny of cross 2. The horizontal line is the ratio expected if there are no differences in the level of expression of the two alleles. Significant ratios are represented in gray.

Phenotypic Effect of the Insertion

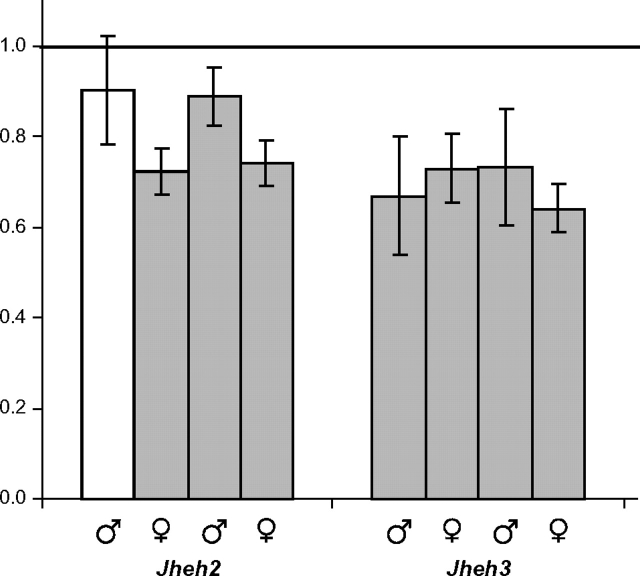

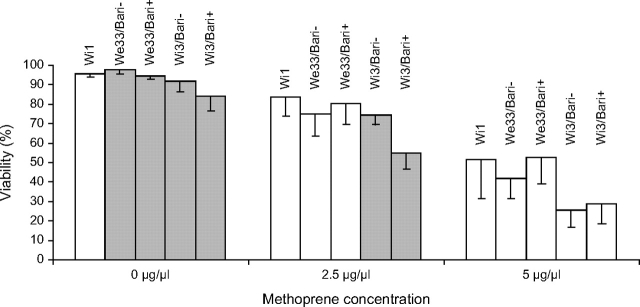

As mentioned above, biological effects of JH are often sensitive to the level of this hormone. Application of exogenous JH or JHas, such as methoprene, during larval development results in late pupal inviability, increased DT and increased fecundity (Flatt et al. 2005; Flatt and Kawecki 2007). Because flies carrying Bari-Jheh insertion showed reduced levels of expression of Jheh2 and Jheh3 genes, both involved in JH degradation, these flies are likely to have elevated JH titers and could show the same effects. The presence of JHa in the food may therefore enhance the expected effects of Bari-Jheh (Wilson and Fabian 1986; Riddiford and Ashburner 1991; Flatt and Kawecki 2007; see Materials and Methods). In this work, we focused on the analysis of viability and DT; results are shown in figures 4 and 5, respectively. Results for the parental strain Wi1 are shown for comparison because the genetic background of this strain should be similar to the background of the introgressed strains and therefore constitutes the baseline of the experiment (see Materials and Methods).

FIG. 4.—

Egg-to-adult viability (proportion surviving) of the parental strain Wi1 lacking Bari-Jheh insertion and introgressed strains Wi3/Bari and We33/Bari as a function of the JHa concentration in the food used to raise the flies. Data shown are means and standard errors of replicate lines within a JHa concentration. Significant comparisons are represented in gray.

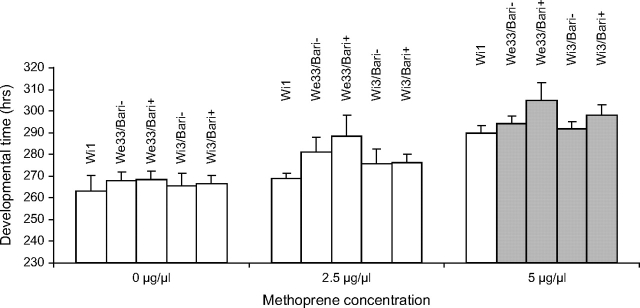

FIG. 5.—

DT (in hours) of the parental strain Wi1 lacking Bari-Jheh insertion and introgressed strains Wi3/Bari and We33/Bari as a function of the JHa concentration in the food used to raise the flies. Data shown are means and standard errors of replicate lines within a JHa concentration. Significant comparisons are represented in gray.

For both viability and DT assays, the data for all the strains analyzed follows a normal distribution (χ2 P value = 0.769 and P value = 1 for viability and DT, respectively). We found a strong negative correlation between viability and JHa concentration (Pearson's correlation: −0.911, P value = 1.17 × 10−6) and a strong positive correlation between DT and JHa concentration (Pearson's correlation: 0.917, P value = 7.56 × 10−7) as expected.

Because two different Bari-Jheh alleles were introgressed into the same genetic background, we considered the identity of the introgressed strain as the nested factor in an ANOVA analysis that considers the effects of the presence/absence of Bari-Jheh, the concentration of JHa in the food, and the interaction between these two factors. Both the presence of Bari-Jheh (ANOVA P value = 0.0158) and the concentration of JHa (ANOVA P value = 0) have an effect on viability in the expected direction (fig. 4; supplementary table S4, Supplementary Material online). The interaction between these two factors is also significant (ANOVA P value = 0.0137). When no JHa was added to the food, both introgressed strains carrying Bari-Jheh showed reduced viability compared with the strains lacking Bari-Jheh, as expected if the downregulation of Jheh genes is increasing JH titer (Mann–Whitney test P value = 0.028 and P value = 0.048 for introgressed strains We33/Bari+ and Wi3/Bari+, respectively). When the food was supplemented with 2.5 μg/μl of JHa, Wi3/Bari+ strain showed reduced viability compared with Wi3/Bari- (Mann–Whitney test P value = 0.0022). As can be seen in figure 4, the viability differences between Wi3/Bari+ and Wi3/Bari− were more significant when JHa was added to the food suggesting that JHa enhances the effect of Bari-Jheh. On the other hand, no significant differences were obtained for We33/Bari introgressed strains (Mann–Whitney test P value = 0.27) suggesting that the genetic background differences can mitigate the effects of Bari-Jheh. Finally, when the food was supplemented with 5 μg/μl of JHa, there were no significant differences between the stocks with and without the insertion for any of the two introgressed strains (Mann–Whitney test P value = 0.12 and P value = 0.29 for We33/Bari and Wi3/Bari, respectively).

The same ANOVA model was used to test the effects of the different factors on DT. Both the presence/absence of Bari-Jheh (ANOVA P value = 0.0005) and the JHa concentration (ANOVA P value = 0) affects the DT significantly, whereas the interaction between these two factors is not significant (ANOVA P value = 0.18). The effect of the presence of Bari-Jheh on the DT is only significant when 5 μg/μl of JHa was added to the food and as expected the strains carrying Bari-Jheh insertion showed an increased DT compared with strains lacking Bari-Jheh (t-test P value = 0.0061 and P value = 0.014 for We33/Bari and Wi3/Bari strains, respectively) (fig. 5; supplementary table S5, Supplementary Material online).

In summary, although not all comparisons between the strains carrying and lacking Bari-Jheh were significant, when they were, the results were consistent with the effects of the reduced expression of Jheh genes, that is, reduced viability and extended DT. This result suggested that Bari-Jheh is not only affecting transcription of the neighboring genes, as previously shown, but that it may also have an effect on some fitness components.

Bari-Jheh Is Inserted Close to Highly Conserved Genes

We analyzed the evolution of the Jheh gene family in the 12 Drosophila species sequenced (Clark et al. 2007). The three genes are closely linked in all the species suggesting that they originated from ancient tandem duplication events. Although only two orthologous genes have been identified in Anopheles gambiae (AGAP008684 and AGAP008686; Hubbard et al. 2007) gene AGAP008685 located between them also shows homology with Jheh genes suggesting that the tandem duplications took place before the divergence between Drosophila and Anopheles about 250 Ma (Zdobnov et al. 2002).

The number of genes in the Jheh family has been conserved along the evolution of the genus Drosophila. Only one species, Drosophila ananassae, has four Jheh genes instead of three: It has a tandem duplication of Jheh2 gene. According to its phylogenetic distribution and to its sequence divergence (Ks = 1.2843; Powell 1997) this duplication took place in the lineage leading to D. ananassae. Therefore, the only exception to the conservation of the gene number in the Jheh family is confined to the ananassae subgroup. Both paralogs of Jheh2 in D. ananassae are likely to be functional because no premature stop codon or frameshift mutations were identified in their coding sequence. They show a high level of amino acid identity (78%) and half of the amino acid changes are conservative (supplementary fig. S1, Supplementary Material online). The estimate of Ka/Ks is low (Ka/Ks = 0.1056) indicating that both genes are highly constrained and suggesting that both retained their original function.

Jheh1, Jheh2, and Jheh3 genes appear to be functional in the 12 Drosophila species (supplementary fig. S2, Supplementary Material online). Jheh2 is predicted to encode two alternative transcripts: Jheh2-PA and Jheh2-PC. The length of the corresponding four proteins is highly conserved across the 12 species and the amino acid identity is high (53–65%). Seven amino acids previously identified as being functional in epoxy hydrolase enzymes (Barth et al. 2004) are conserved in the 12 species consistent with the functionality of these genes (supplementary fig. S2, Supplementary Material online). One of these functional residues is spliced out in transcript Jheh2-PC; however, according to Flybase, this transcript may or may not produce a functional polypeptide.

We estimated ω (the ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous divergence) for each Jheh gene using PAML (Yang 2007). We did the analysis including either the six species of the melanogaster group or the 12 Drosophila species sequenced. Estimates of ds for all the different branches were ≤1 suggesting that synonymous sites are not saturated and therefore the alignments including the 12 Drosophila species can be used to estimate the rate of evolution of Jheh genes (Heger and Ponting 2007). For each Jheh gene, the estimate of ω was <0.1 suggesting that Jheh genes are evolving under strong purifying selection (table 2). Similar results were obtained when the analysis was restricted to the six species in the melanogaster group (table 2).

Table 2.

Ratio of Nonsynonymous to Synonymous Substitutions (ω) Considering the 12 Drosophila Species Sequenced and Only the Six Species in the melanogaster Group

| Gene | ω (12 Species) | ω (6 Species) |

| Jheh1 | 0.06623 | 0.06413 |

| Jheh2 | 0.09615 | 0.10795 |

| Jheh3 | 0.07432 | 0.05723 |

We also tested for evidence of positive selection by comparing models that allowed heterogeneous ω ratios among sites (see Materials and Methods). No evidence for positive selection was found for any of the three genes either when the six melanogaster group species or the 12 Drosophila species were analyzed (P value > 0.05).

Finally, we analyzed if TEs were likely to have played a role in the evolution of Jheh genes in the 12 Drosophila species. We did not find any TE insertion in the intergenic region between Jheh1 and Jheh2 genes. In the intergenic region between Jheh2 and Jheh3 genes, besides the Bari-Jheh insertion in D. melanogaster, we found small fragments (84–137 bp) that showed similarity with Penelope TE in D. yakuba and Drosophila erecta (supplementary table S6, Supplementary Material online). Overall, there is no evidence for a recurrent role of TEs in the evolution of Jheh genes.

Evidence of Constant Purifying Selection in the Recent Evolution of Jheh Genes

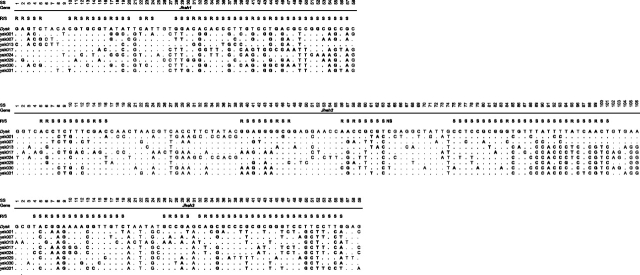

We analyzed the evolution of Jheh genes in the species of the melanogaster subgroup in greater detail. Besides D. melanogaster (figs. 1 and 2), we collected polymorphism data for D. simulans (fig. 6), a cosmopolitan species that diverged from D. melanogaster approximately 5.4 Ma (Tamura et al. 2004). We also collected polymorphism data for the coding regions of the three Jheh genes in D. yakuba (fig. 7), which is an endemic AF species that shared a common ancestor with the other two species 12.8 Ma (Tamura et al. 2007).

FIG. 6.—

Sequence of the 6.8-kb region including Jheh1, Jheh2, and Jheh3 genes in Drosophila simulans (GQ169213–GQ169226). The black line separates the non-AF from the AF strains. See figure 1 for details.

FIG. 7.—

Sequence of Jheh1, Jheh2, and Jheh3 coding regions in Drosophila yakuba (GQ169144–GQ169167). See figure 1 for details.

We first looked for evidence of selective constraint in the coding, noncoding (untranslated regions [UTRs] and introns), and intergenic regions of Jheh genes in the three species. The ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous polymorphisms in the coding regions of the three genes (table 3), the ratio of polymorphisms in noncoding regions to synonymous polymorphism in the coding region of the same gene (table 3), and the ratio of polymorphism in intergenic regions to synonymous polymorphisms in the two flanking genes (table 4) were smaller than 1. These results suggested that coding, noncoding and intergenic regions have been evolving under purifying selection. We only found one exception; Drosophila melanogaster Jheh2 noncoding regions had a higher number of polymorphisms compared with the synonymous polymorphisms within the gene (table 3). This result is likely explained by the selective sweep associated with the insertion of Bari-Jheh in this particular region of the genome (fig. 1).

Table 3.

Ratio of non-synonymous to synonymous polymorphisms (Pn/Ps) and of non-coding to synonymous polymorphisms (Pnc/Ps) for Jheh genes in D. melanogaster (Dmel), D. simulans (Dsim) and D. yakuba (Dyak).

| Coding |

Noncoding (UTR + Introns) |

|||||

| Species | Na | Lb | Pn/Ps | N | L | Pnc/Ps |

| Jheh1_Dmel | 16 | 1425 | 5/22 (1/11) | 16 | 257 | 11/22 (6/11) |

| Jheh1_Dsim | 15 | 1425 | 9/29 (3/14) | 15 | 200 | 12/29 (8/14) |

| Jheh1_Dyak | 9 | 1425 | 12/37 (6/26) | 9 | 225 | 9/37 (6/26) |

| χ2 P-value | 0.828 (0.698) | 0.354 (0.278) | ||||

| Jheh2_Dmel | 16 | 1392 | 3/5 (2/3) | 16 | 706 | 18/5 (12/3) |

| Jheh2_Dsim | 15 | 1392 | 7/35 (3/22) | 15 | 568 | 35/35 (25/22) |

| Jheh2_Dyak | 9 | 1377 | 11/42 (5/23) | 9 | 573 | 45/48 (23/26) |

| χ2 P-value | 0.405 (0.316) | 0.034 (0.079) | ||||

| Jheh3_Dmel | 16 | 1404 | 5/30 (4/24) | 16 | 296 | 10/30 (10/24) |

| Jheh3_Dsim | 14 | 1404 | 3/19 (1/11) | 14 | 200 | 9/22 (4/13) |

| Jheh3_Dyak | 9 | 1404 | 4/41 (3/17) | 9 | 203 | 14/24 (3/11) |

| χ2 P-value | 0.724 (0.848) | 0.515 (0.815) | ||||

NOTE.—Values excluding singletons are given in parentheses.

N: number of strains analyzed.

L: lenght of the sequence analyzed.

Table 4.

Ratio of Noncoding to Synonymous Polymorphisms (Pnc/Ps) in the Intergenic Regions of Jheh Genes

| Species | Intergenic Regions |

||

| Na | Lb | Pnc/Ps | |

| Dsim Jheh1–Jheh2 | 15 | 635 | 53/64 (33/36) |

| Dmel Jheh2–Jheh3 | 16 | 607 | 23/35 (14/27) |

| Dsim Jheh2–Jheh3 | 14 | 835 | 29/57(16/35) |

| χ2P value | 0.467 (0.778) | ||

NOTE.—Values excluding singletons are given in parentheses.

N: number of strains analyzed.

L: length of the sequence analyzed.

The ratios of nonneutral to neutral polymorphism for each of the three analyzed regions—coding, noncoding (UTR and introns), and intergenic—are not statistically different between species. This suggests that this region of the genome has been subject to fairly constant levels of purifying selection in the three species (tables 3 and 4).

We further analyzed the intergenic region where Bari-Jheh is inserted in 34 D. melanogaster strains that we sequenced previously (González et al. 2008). Other than Bari-Jheh, only a single 43-bp (TA) repeat was found. This simple repeat is flanking the insertion and is also present in the strains without Bari-Jheh where its length varies between 6 and 61 bp. This repetitive sequence is not characteristic of Bari1 insertions because it is not present in the flanking regions of the other five Bari1 insertions described in the genome (FBti0019419, FBti0019499, FBti0019099, FBti0064232, and FBti0019400). In summary, although Bari-Jheh is inserted in an intergenic region likely to be evolving under purifying selection, the exact position where Bari-Jheh is inserted is not conserved. Furthermore, the VISTA browser alignment between D. melanogaster and D. simulans shows that sequence conservation drops in the region immediately adjacent to Bari-Jheh (http://genome.lbl.gov/vista/index.shtml; supplementary fig. S3, Supplementary Material online). This result suggests that Bari-Jheh may be affecting the expression of its neighboring genes by altering the physical distance between regulatory elements and the transcriptional start site or by adding regulatory elements itself rather than by disrupting existing regulatory elements.

No Evidence of Recurrent Adaptive Evolution in the Recent History of Jheh Genes

We did not find evidence for recurrent adaptive evolution acting on Jheh genes across the phylogeny of the 12 Drosophila species. However, it could be that positive selection has been restricted to the recent history of these species. Bari-Jheh insertion most likely played a role in the adaptation to the new environments faced by D. melanogaster in its expansion out of Africa (González et al. 2008). Because D. simulans has independently undergone a similar migration out of sub-Saharan Africa (Hamblin and Veuille 1999; Baudry et al. 2006), we explored the possibility of a parallel adaptive event in this region of the genome in D. simulans. As can be seen in figure 6, the sequence of each D. simulans strain represents a different haplotype. Tajima's D and Fu and Li's D and F are not significantly different from the neutral expectations (table 5). These neutrality tests assume that the population is at equilibrium and as mentioned before, the out-of-Africa D. simulans populations are likely to be out of equilibrium (Hamblin and Veuille 1999; Baudry et al. 2006). Not taking into account the demographic history of the species may result in spurious inference of positive selection (Orengo and Aguade 2004; Ometto et al. 2005; Teshima et al. 2006; Thornton et al. 2007; Macpherson et al. 2008). However, an expansion of D. simulans out of Africa is unlikely to mask a true selective sweep if it was in fact there.

Table 5.

Polymorphism and Neutrality Tests for the 6.8-kb Region of Drosophila simulans Including the Three Jheh Genes

| Strains | Na | SSb | Hc | hdd | π(JC)e | θwf | Neutrality Tests |

||

| Dg | FL-Dh | FL-Fi | |||||||

| All | 14 | 242 | 14 | 1 | 0.01095 | 0.01120 | −0.17373 | −0.48561 | −0.45946 |

| Non-AF | 8 | 117 | 8 | 1 | 0.00776 | 0.00664 | 0.87383 | 0.50397 | 0.65968 |

| AF | 6 | 217 | 6 | 1 | 0.01354 | 0.01399 | −0.26671 | −0.27782 | −0.30303 |

N: number of strains analyzed.

SS: number of segregating sites.

H: number of haplotypes.

hd: haplotype diversity.

π(JC): average pairwise diversity with Jukes and Cantor correction.

θw: Watterson's estimator of nucleotide diversity.

D: Tajima's D statistic.

FL-D: Fu and Li D statistic.

FL-F: Fu and Li F statistic.

We performed McDonald–Kreitman test to further look for evidence of positive selection in the recent evolution of this genomic region (McDonald and Kreitman 1991; Andolfatto 2005; Egea et al. 2008). First, we searched for evidence of positive selection in the D. melanogaster and D. simulans lineages. We performed the analysis both considering all the positions and excluding variants that are present in only one of the strains analyzed (singletons). We did not find any evidence of positive selection in coding, noncoding or intergenic regions (tables 6 and 7). For coding regions, we also considered the polymorphism data collected for D. yakuba and looked for evidence of positive selection during the evolution of these three species. Marginally significant results were obtained for Jheh2 gene when singletons were excluded from the analysis (table 6); however, this result is not significant after correcting for multiple tests. Altogether, these results suggest that Jheh genes have not been subject to recurrent and pervasive adaptive evolution in the recent past.

Table 6.

McDonald Kreitman test for the coding and non-coding regions of Jheh genes.

| Species | Coding |

|||

| Dmel+Dsim | La | Pn/Psb | Dn/Dsc | P-value |

| Jheh1 | 1416 | 14/48 (4/23) | 10/29 (10/34) | 0.691 (0.416) |

| Jheh2 | 1386 | 10/38 (5/24) | 3/30 (3/32) | 0.162 (0.297) |

| Jheh3 | 1398 | 8/47 (5/33) | 9/30 (9/32) | 0.276 (0.300) |

| Noncoding |

||||

| Dmel+Dsim | L | Pnc/Psd | Dnc/Dse | P-value |

| Jheh1 | 198 | 21/48 (13/23) | 12/29 (14/34) | 0.998 (0.454) |

| Jheh2 | 502 | 44/38 (30/25) | 49/30 (50/34) | 0.268 (0.567) |

| Jheh3 | 197 | 14/27 (9/19) | 15/14 (15/16) | 0.137 (0.209) |

| Coding |

||||

| Dmel+Dsim vs Dyak | L | Pn/Ps | Dn/Ds | P-value |

| Jheh1 | 1401 | 23/70 (14/50) | 18/51 (18/52) | 0.816 (0.588) |

| Jheh2 | 1344 | 12/57 (8/47) | 22/51 (23/52) | 0.079 (0.031) |

| Jheh3 | 1380 | 17/69 (14/59) | 13/41 (13/42) | 0.542 (0.544) |

NOTE.—Values excluding singletons are given in parentheses.

L: length of the sequence analyzed.

Ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous polymorphisms.

Ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous divergence corrected by Jukes and Cantor (1969).

Ratio of noncoding to synonymous polymorphisms.

Ratio of noncoding to synonymous divergence corrected by Jukes and Cantor (1969).

Table 7.

McDonald and Kreitman Tests for the Intergenic Regions of Jheh Genes

| Intergenic Regions |

||||

| La | Pnc/Psb | Dnc/Dsc | P Value | |

| Dsim versus Dmel: Jheh1–Jheh2 | 600 | 47/86 (28/47) | 17/58 (19/66) | 0.061 (0.042) |

| Dmel + Dsim: Jheh2–Jheh3 | 329 | 22/85 (14/57) | 17/59 (17/64) | 0.842 (0.898) |

NOTE.—Values excluding singletons are given in parentheses.

Length of the sequence analyzed.

Ratio of noncoding to synonymous polymorphisms per site.

Ratio of noncoding to synonymous divergence.

Discussion

Bari-Jheh Insertion Is Adaptive

Bari-Jheh insertion was recently identified as being putatively adaptive in a genomewide screen for recent TE-induced adaptations (González et al. 2008). Here, we provided additional evidence that this insertion was indeed adaptive. By further sequencing the region flanking the insertion, we delimited the extent of the selective sweep and showed that Bari-Jheh is the only mutation linked to the sweep (Smith and Haigh 1974; Kaplan et al. 1988, 1989). Consequently, Bari-Jheh appears to be the causative mutation of the sweep (fig. 1). Furthermore, Bari-Jheh is associated with changes in the transcription of its flanking genes: It downregulates the expression of both Jheh2 and Jheh3 (fig. 3). Because both genes are involved in the degradation of JH, a plausible consequence of the reduced expression of Jheh genes is an increased JH titer. Increased JH titer is expected to lead to reduced viability and extended DT among many other phenotypic effects (Flatt et al. 2005; Flatt and Kawecki 2007). Although we did not always find significant differences between the strains carrying and lacking Bari-Jheh, when we did, the results were consistent with the expectations, suggesting that Bari-Jheh has subtle phenotypic consequences (figs. 4 and 5). These two phenotypic effects imply a reduced fitness for the flies carrying the insertion. Interestingly, Bari-Jheh is present at high frequency in all the derived non-AF populations analyzed, NA, Australian, and European; however, it is not fixed in any of them (González et al. 2008). A plausible explanation for these results is that the reduced viability and increased DT could represent the associated cost of selection for Bari-Jheh insertion, which would explain why Bari-Jheh is not fixed in the derived non-AF populations.

What is the adaptive effect of Bari-Jheh? Previous results showed that the frequency of Bari-Jheh did not vary between a temperate and a more tropical out-of-Africa population suggesting that the adaptive effect of this insertion was not related to climatic adaptation (González et al. 2008). However, JH is a regulator of development, life history, and fitness trade-offs (Flatt et al. 2005; Riddiford 2008). Any of the large number of traits and processes in Drosophila development and life history affected by JH could have been affected by Bari-Jheh insertion. In order to understand the adaptive consequences of this insertion a thorough phenotypic analysis will be required. The challenge will be to determine which phenotype or phenotypes to study and under what ecological conditions they should be examined (Jensen et al. 2007). The availability of 192 wild-derived inbred lines that are currently being phenotyped and sequenced will facilitate the understanding of the functional impact of this and other putatively adaptive TEs (Ayroles et al. 2009).

A Unique Adaptive Event Near Highly Constrained Loci

Bari-Jheh is inserted near highly constrained genes. The number of genes in the Jheh gene family has been conserved for the last 80–124 My (Tamura et al. 2004). These genes appear to be functional in the 12 Drosophila species sequenced and encode proteins of similar length (Clark et al. 2007). Furthermore, coding, noncoding, and intergenic regions seem to have been evolving under purifying selection both in the long term, when the 12 Drosophila species sequenced were analyzed, and short term, when only the species of the melanogaster subgroup were analyzed. In addition, the strength of purifying selection appeared to have been constant at least for the last 12.8 My (tables 3 and 4). Overall, we can conclude that Jheh genes have been evolving under purifying selection for long periods of time and that the strength of purifying selection acting on these genes has not changed in the recent past.

We looked for evidence of parallel adaptive events during the evolution of this gene family. We explored different possibilities; in the long-term evolution, 1) we looked for evidence of parallel adaptive TE insertions in the intergenic regions and 2) we tested whether a subset of codons in these genes showed evidence for replacement mutations fixing more frequently than silent mutations (Yang 2007). In the short-term evolution, 3) we looked for evidence of parallel selective sweeps in the orthologous sequence of D. simulans, and 4) we tested whether the ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous divergence was higher than the ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous polymorphism in coding, noncoding and intergenic regions of D. melanogaster, D. simulans, and D. yakuba (McDonald and Kreitman 1991; Andolfatto 2005). Overall, we did not find evidence for recurrent and pervasive adaptive evolution acting on Jheh genes in the long-term or short-term evolution of this gene family. In conclusion, Bari-Jheh appears to be either unique or at least a very rare adaptive event in the history of Jheh genes. No current analysis would suggest that these highly constrained and conserved genes are likely targets of adaptation.

Implications for the Study of Adaptation

Here, we showed that adaptive variation within species might be found in genes that do not undergo frequent adaptation. These genes would be overlooked by the most widely used approaches to look for positive selection, such as McDonald and Kreitmant test or codon-based tests such as those implemented in PAML, because these approaches are based on the assumption that adaptation is recurring at the same loci or even at the same sites (McDonald and Kreitman 1991; Hughes 2007; Jensen et al. 2007; Macpherson et al. 2007; Yang 2007). It is not clear how frequently selection favors repeated amino acid changes at a limited set of sites within a given gene and therefore these type of studies may only give a partial view of the genetics underlying adaptation (Fay et al. 2002; Smith and Eyre-Walker 2002; Andolfatto 2005; Bustamante et al. 2005; Macpherson et al. 2007; Sawyer et al. 2007; Shapiro et al. 2007). In addition, adaptations might be local and ephemeral and therefore destined to be lost over long periods of time (González et al. 2008). This suggests that functional genetic variation within species might at times be due to different mutations than mutations leading to functional divergence between species. This functional variation will only be identified by approaches that identified mutations that have recently swept through the population such as genomewide scans for positive selection (see Pavlidis et al. 2008 for a review) or the approach described in González et al. (2008). In conclusion, population genetics methods that are capable of detecting selection on a single recent adaptive mutation and divergence based methods that rely on the repeated selective fixation of amino acid changes followed by appropriate functional studies should be combined in order to get a fuller picture of adaptation.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary table S1–S6 and supplementary figures S1–S3 are available at Molecular Biology and Evolution online (http://www.mbe.oxfordjournals.org/).

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Chatterji for providing the Jheh gene sequences for the 12 Drosophila species; D. Chung and S. Tran for technical assistance with the generation of the introgressed strains, T. Flatt for helpful advice on the life-history phenotypic assays, R. Hershberg and P. Markova-Raina for help with the PAML analysis, and N. Petit and all members of Petrov lab for comments on the manuscript. J.G. was a Fulbright/Secretaria de Estado de Universidades e Investigacion, MEC postdoctoral fellow. J.M.M. was an HHMI Predoctoral Fellow. This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (GM077368) and the National Science Foundation (0317171) to DAP.

References

- Aminetzach YT, Macpherson JM, Petrov DA. Pesticide resistance via transposition-mediated adaptive gene truncation in Drosophila. Science. 2005;309:764–767. doi: 10.1126/science.1112699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andolfatto P. Adaptive evolution of non-coding DNA in Drosophila. Nature. 2005;437:1149–1152. doi: 10.1038/nature04107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayroles JF, Carbone MA, Stone EA, et al. (11 co-authors) Systems genetics of complex traits in Drosophila melanogaster. Nat Genet. 2009;41:299–307. doi: 10.1038/ng.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth S, Fischer M, Schmid RD, Pleiss J. Sequence and structure of epoxide hydrolases: a systematic analysis. Proteins. 2004;55:846–855. doi: 10.1002/prot.20013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudry E, Derome N, Huet M, Veuille M. Contrasted polymorphism patterns in a large sample of populations from the evolutionary genetics model Drosophila simulans. Genetics. 2006;173:759–767. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.046250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudry E, Viginier B, Veuille M. Non-African populations of Drosophila melanogaster have a unique origin. Mol Biol Evol. 2004;21:1482–1491. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begun DJ, Holloway AK, Stevens K, et al. (13 co-authors) Population genomics: whole-genome analysis of polymorphism and divergence in Drosophila simulans. PLoS Biol. 2007;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050310. e310. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman CM, Pfeiffer BD, Rincón-Limas DE, et al. (17 co-authors) Assessing the impact of comparative genomic sequence data on the functional annotation of the Drosophila genome. Genome Biol. 2002;3 doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-12-research0086. RESEARCH0086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biemont C, Vieira C. Genetics: junk DNA as an evolutionary force. Nature. 2006;443:521–524. doi: 10.1038/443521a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante CD, Fledel-Alon A, Williamson S, et al. (14 co-authors) Natural selection on protein-coding genes in the human genome. Nature. 2005;437:1153–1157. doi: 10.1038/nature04240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caizzi R, Caggese C, Pimpinelli S. Bari-1, a new transposon-like family in Drosophila melanogaster with a unique heterochromatic organization. Genetics. 1993;133:335–345. doi: 10.1093/genetics/133.2.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caracristi G, Schlotterer C. Genetic differentiation between American and European Drosophila melanogaster populations could be attributed to admixture of African alleles. Mol Biol Evol. 2003;20:792–799. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth B, Sniegowski P, Stephan W. The evolutionary dynamics of repetitive DNA in eukaryotes. Nature. 1994;371:215–220. doi: 10.1038/371215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark AG, Eisen MB, Smith DR, et al. (244 co-authors) Evolution of genes and genomes on the Drosophila phylogeny. Nature. 2007;450:203–218. doi: 10.1038/nature06341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daborn PJ, Yen JL, Bogwitz MR, et al. (13 co-authors) A single p450 allele associated with insecticide resistance in Drosophila. Science. 2002;297:2253–2256. doi: 10.1126/science.1074170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David JR, Capy P. Genetic variation of Drosophila melanogaster natural populations. Trends Genet. 1988;4:106–111. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(88)90098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kort CAD, Granger NA. Regulation of JH titers: the relevance of degradative enzymes and binding proteins. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol. 1996;33:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Doolittle WF, Sapienza C. Selfish genes, the phenotype paradigm and genome evolution. Nature. 1980;284:601–603. doi: 10.1038/284601a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egea R, Casillas S, Barbadilla A. Standard and generalized McDonald–Kreitman test: a website to detect selection by comparing different classes of DNA sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:W157–W162. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fay JC, Wyckoff GJ, Wu CI. Testing the neutral theory of molecular evolution with genomic data from Drosophila. Nature. 2002;415:1024–1026. doi: 10.1038/4151024a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feschotte C. Transposable elements and the evolution of regulatory networks. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:397–405. doi: 10.1038/nrg2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flatt T, Kawecki TJ. Juvenile hormone as a regulator of the trade-off between reproduction and life span in Drosophila melanogaster. Evolution. 2007;61:1980–1991. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flatt T, Tu MP, Tatar M. Hormonal pleiotropy and the juvenile hormone regulation of Drosophila development and life history. Bioessays. 2005;27:999–1010. doi: 10.1002/bies.20290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González J, Lenkov K, Lipatov M, Macpherson JM, Petrov DA. High rate of recent transposable element-induced adaptation in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e251. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamblin MT, Veuille M. Population structure among African and derived populations of Drosophila simulans: evidence for ancient subdivision and recent admixture. Genetics. 1999;153:305–317. doi: 10.1093/genetics/153.1.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heger A, Ponting CP. Evolutionary rate analyses of orthologs and paralogs from 12 Drosophila genomes. Genome Res. 2007;17:1837–1849. doi: 10.1101/gr.6249707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard TJ, Aken BL, Beal K, et al. (58 co-authors) Ensembl 2007. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D610–D617. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes AL. Looking for Darwin in all the wrong places: the misguided quest for positive selection at the nucleotide sequence level. Heredity. 2007;99:364–373. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6801031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen JD, Wong A, Aquadro CF. Approaches for identifying targets of positive selection. Trends Genet. 2007;23:568–577. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurka J, Kapitonov VV, Kohany O, Jurka MV. Repetitive sequences in complex genomes: structure and evolution. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2007;8:241–259. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.8.080706.092416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan NL, Darden T, Hudson RR. The coalescent process in models with selection. Genetics. 1988;120:819–829. doi: 10.1093/genetics/120.3.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan NL, Hudson RR, Langley CH. The “hitchhiking effect” revisited. Genetics. 1989;123:887–899. doi: 10.1093/genetics/123.4.887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazazian HH., Jr Mobile elements: drivers of genome evolution. Science. 2004;303:1626–1632. doi: 10.1126/science.1089670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khlebodarova TM, Gruntenko NE, Grenback LG, Sukhanova MZ, Mazurov MM, Rauschenbach IY, Tomas BA, Hammock BD. A comparative analysis of juvenile hormone metabolyzing enzymes in two species of Drosophila during development. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1996;26:829–835. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(96)00043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidwell MG, Lisch DR. Perspective: transposable elements, parasitic DNA, and genome evolution. Evolution. 2001;55:1–24. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2001.tb01268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachaise D, Cariou ML, David JR, Lemeunier F, Tsacas F, Ashburner M. Historical biogeography of the Drosophila melanogaster species subgroup. Evol Biol. 1988;22:159–225. [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Stephan W. Inferring the demographic history and rate of adaptive substitution in Drosophila. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e166. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macpherson JM, Gonzalez J, Witten DM, Davis JC, Rosenberg NA, Hirsh AE, Petrov DA. Nonadaptive explanations for signatures of partial selective sweeps in Drosophila. Mol Biol Evol. 2008;25:1025–1042. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macpherson JM, Sella G, Davis JC, Petrov DA. Genomewide spatial correspondence between nonsynonymous divergence and neutral polymorphism reveals extensive adaptation in Drosophila. Genetics. 2007;177:2083–2099. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.080226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddison WP, Maddison DR. Interactive analysis of phylogeny and character evolution using the computer program MacClade. Folia Primatol (Basel) 1989;53:190–202. doi: 10.1159/000156416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino-Ramirez L, Lewis KC, Landsman D, Jordan IK. Transposable elements donate lineage-specific regulatory sequences to host genomes. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2005;110:333–341. doi: 10.1159/000084965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald JH, Kreitman M. Adaptive protein evolution at the Adh locus in Drosophila. Nature. 1991;351:652–654. doi: 10.1038/351652a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern B. DIALIGN: multiple DNA and protein sequence alignment at BiBiServ. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W33–W36. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ometto L, Glinka S, De Lorenzo D, Stephan W. Inferring the effects of demography and selection on Drosophila melanogaster populations from a chromosome-wide scan of DNA variation. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:2119–2130. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orengo DJ, Aguade M. Detecting the footprint of positive selection in a European population of Drosophila melanogaster: multilocus pattern of variation and distance to coding regions. Genetics. 2004;167:1759–1766. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.028969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orgel LE, Crick FH. Selfish DNA: the ultimate parasite. Nature. 1980;284:604–607. doi: 10.1038/284604a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlidis P, Hutter S, Stephan W. A population genomic approach to map recent positive selection in model species. Mol Ecol. 2008;17:3585–3598. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piriyapongsa J, Rutledge MT, Patel S, Borodovsky M, Jordan IK. Evaluating the protein coding potential of exonized transposable element sequences. Biol Direct. 2007;2:31. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-2-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell JR. Progress and prospects in evolutionary biology. The Drosophila model. New York: Oxford University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Riddiford LM. Juvenile hormone action: a 2007 perspective. J Insect Physiol. 2008;54:895–901. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2008.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddiford LM, Ashburner M. Effects of juvenile hormone mimics on larval development and metamorphosis of Drosophila melanogaster. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 1991;82:172–183. doi: 10.1016/0016-6480(91)90181-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozas J, Sanchez-DelBarrio JC, Messeguer X, Rozas R. DnaSP, DNA polymorphism analyses by the coalescent and other methods. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:2496–2497. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer SA, Parsch J, Zhang Z, Hartl DL. Prevalence of positive selection among nearly neutral amino acid replacements in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:6504–6510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701572104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro JA, Huang W, Stone C, et al. (12 co-authors) Adaptive genic evolution in the Drosophila genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:2271–2276. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610385104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JM, Haigh J. The hitch-hiking effect of a favourable gene. Genet Res. 1974;23:23–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith NG, Eyre-Walker A. Adaptive protein evolution in Drosophila. Nature. 2002;415:1022–1024. doi: 10.1038/4151022a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajima F. Evolutionary relationship of DNA sequences in finite populations. Genetics. 1983;105:437–460. doi: 10.1093/genetics/105.2.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Subramanian S, Kumar S. Temporal patterns of fruit fly (Drosophila) evolution revealed by mutation clocks. Mol Biol Evol. 2004;21:36–44. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teshima KM, Coop G, Przeworski M. How reliable are empirical genomic scans for selective sweeps? Genome Res. 2006;16:702–712. doi: 10.1101/gr.5105206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton K, Andolfatto P. Approximate Bayesian inference reveals evidence for a recent, severe bottleneck in a Netherlands population of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2006;172:1607–1619. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.048223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton KR, Jensen JD, Becquet C, Andolfatto P. Progress and prospects in mapping recent selection in the genome. Heredity. 2007;98:340–348. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Lagemaat LN, Landry JR, Mager DL, Medstrand P. Transposable elements in mammals promote regulatory variation and diversification of genes with specialized functions. Trends Genet. 2003;19:530–536. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voight BF, Kudaravalli S, Wen X, Pritchard JK. A map of recent positive selection in the human genome. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e72. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Elbein SC. Detection of allelic imbalance in gene expression using pyrosequencing. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;373:157–176. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-377-3:157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson TG, Fabian J. A Drosophila melanogaster mutant resistant to a chemical analog of juvenile hormone. Dev Biol. 1986;118:190–201. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90087-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittkopp PJ, Haerum BK, Clark AG. Evolutionary changes in cis and trans gene regulation. Nature. 2004;430:85–88. doi: 10.1038/nature02698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1586–1591. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zdobnov EM, von Mering C, Letunic I, et al. (36 co-authors) Comparative genome and proteome analysis of Anopheles gambiae and Drosophila melanogaster. Science. 2002;298:149–159. doi: 10.1126/science.1077061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.