Abstract

Acute kidney injury stimulates renal production of inflammatory mediators, including TNF-α and monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1). These responses reflect, in part, injury-induced transcription of proinflammatory genes by proximal tubule cells. Because of the compact structure of chromatin, a series of events at specified loci remodel chromatin to provide access for transcription factors and RNA polymerase II (Pol II). Here, we examined the role of Brahma-related gene-1 (BRG1), a chromatin remodeling enzyme, in the transcription of TNF-α and MCP-1 in response to renal ischemia. Two hours after renal ischemic injury in mice, renal TNF-α and MCP-1 mRNA increased and remained elevated for at least 1 wk. Matrix chromatin immunoprecipitation assays revealed sustained increases in Pol II at these genes, suggesting that the elevated mRNA levels were, at least in part, transcriptionally mediated. The profile of BGR1 binding to the genes encoding TNF-α and MCP-1 resembled Pol II recruitment. Knockdown of BRG1 by small interfering RNA blocked an ATP depletion–induced increase in TNF-α and MCP-1 transcription in a human proximal tubule cell line; this effect was associated with decreased recruitment of BRG1 and Pol II to these genes. In conclusion, BRG1 promotes increased transcription of TNF-α and MCP-1 by the proximal tubule in response to renal ischemia.

It has been well documented that diverse forms of acute renal failure (ARF) evoke cytokine (e.g., TNF-α) and chemokine (e.g., monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 [MCP-1]) production by the kidney.1–4 Together with the potential involvement of resident lymphocytes, neutrophils, and monocytes/macrophages, these and other kidney cell–derived mediators cause intrarenal inflammation.5–7 These inflammatory changes have a number of potentially important clinical consequences: (1) Renal inflammation can exacerbate the severity of renal failure7,8; (2) renal cytokines and chemokines can be released into the systemic circulation, where they may evoke extrarenal tissue injury and contribute to multiorgan failure6,9; and (3) secondary inflammatory responses may postpone renal functional recovery and potentially promote ESRD. Given the importance of TNF-α, MCP-1, and other proinflammatory mediators in kidney disease, it is surprising how little is known about their regulation in response to kidney injury.

ARF-mediated intrarenal synthesis of inflammatory mediators cells may reflect increased transcription and changes in chromatin dynamics along target loci.10 The compact structure of chromatin, composed of proteins, DNA, and RNA, represents a physical obstacle to molecular interactions that mediate transcription.11,12 Multiple processes exist to open up, or relax, chromatin structure, thereby exposing docking sites for the binding of transcription factors and providing polymerase II (Pol II) access to the DNA template. The dynamics of chromatin structure are regulated by diverse processes, such as DNA methylation, covalent histone modifications, chromatin remodeling, histone eviction, and deposition of histone variants.11,12 The term “chromatin remodeling” refers to processes by which the energy derived from ATP hydrolysis is used to loosen histone–DNA contacts, thereby allowing the sliding of nucleosomes along DNA. This renders the promoter, enhancer, and transcribed regions more accessible to transcription factor and Pol II binding.

There are several highly conserved multiprotein chromatin remodeling complexes, which include SWItch/Sucrose NonFermentable (SWI/SNF), Nucleosome remodeling factor (NURF), Nucleosome remodeling and histone deacetylation (NuRD) (classified into SWItch2 (Swi2)-, Imitation switch (ISWI)-, Chromodomain helicase DNA-binding (Chd)-, or INO80-containing complexes).13–17 These chromatin remodelers have different subunit compositions; however, all depend on helicase-like ATPase activity that regulates chromatin structure in a similar manner. The general view is that the ATPases of these complexes act as molecular motors that facilitate dynamic changes in chromatin structure at both active and inactive genes. The human SWI/SNF complex contains either the Brahma-related gene 1 (BRG1) or Brahma (BRM) ATPase catalytic chromatin remodeler subunit. In the mouse, BRG1 but not BRM is essential in vivo,18 suggesting that BRG1-containing SWI/SNF nucleosomal remodeling complexes are critical in mammalian organisms. The functional importance of BRG1 is further underscored by the observation that this protein alone is capable of inducing chromatin remodeling in vitro.19 Because BRG1 regulates chromatin structure in response to stress,20,21 we explored its role in transcription of TNF-α and MCP-1 genes in an in vivo and in vitro model of ischemic renal injury.

Results

Ischemia-Reperfusion Induces Increasingly Sustained Expression of TNF-α and MCP-1 mRNA in Renal Cortex

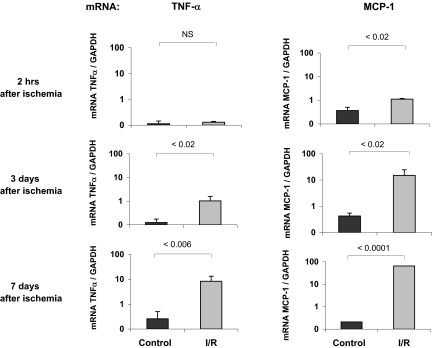

Acute kidney injury increases expression of TNF-α and MCP-1 mRNA in the kidney.4,10,22,23 We used reverse transcriptase–PCR (RT-PCR) to follow renal cortical TNF-α and MCP-1 mRNA levels soon after that injury and during the subsequent week. By 2 h of reperfusion, there was an increase in the MCP-1 mRNA levels, whereas TNF-α was not yet significantly increased, but at both 3 and 7 d after ischemia, marked elevations of both mRNAs were observed (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Expression of TNF-α and MCP-1 genes after I/R. RNA was extracted from mouse cortical samples at 2 h, 3 d, or 7 d after 30 min of I/R ( ). The contralateral kidneys, not subjected to I/R, served as time-matched controls (■). The mRNA levels of TNF-α and MCP-1 were assessed by competitive PCR and are expressed as a ratio to the simultaneously obtained glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) transcript. Data are means ± 1 SD (n = 4 mice).

). The contralateral kidneys, not subjected to I/R, served as time-matched controls (■). The mRNA levels of TNF-α and MCP-1 were assessed by competitive PCR and are expressed as a ratio to the simultaneously obtained glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) transcript. Data are means ± 1 SD (n = 4 mice).

Ischemia-Reperfusion Induces Sustained Chromatin Changes and Co-recruitment of BRG1 and Pol II along the TNF-α and MCP-1 Genes in Renal Cortex

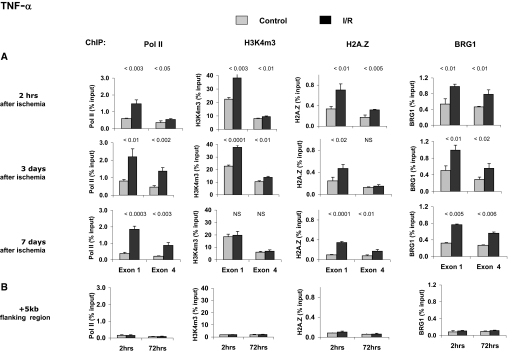

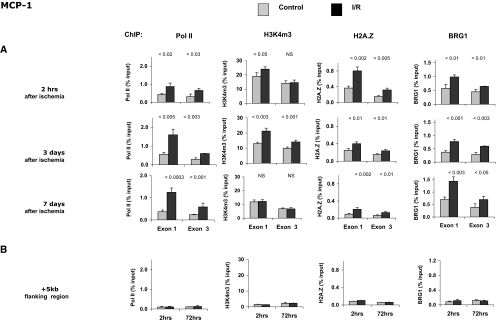

The aforementioned ischemia-reperfusion (I/R)-induced increases in renal cortical TNF-α and MCP-1 mRNA levels could reflect enhanced Pol II recruitment to these loci, leading to increased transcription rates.10 We used the matrix chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) platform24,25 to profile Pol II levels along these genes (Figures 2 and 3). At 2 h after acute injury, the levels of Pol II at the start (P < 0.003) and end exon (P < 0.05) of TNF-α (Figure 2A) were higher in postischemic kidneys, compared with contralateral controls. Like the mRNA levels (Figure 1), the I/R-induced Pol II changes persisted for at least 1 wk after the injury. The levels of Pol II at a 3′ flanking region 5 kb from the end of the TNF-α gene were low and not different between injured and contralateral kidneys (Figure 2B), indicating the specificity of the ChIP assay. Similar results were obtained along the MCP-1 gene locus (Figure 3). The ChIP analysis of Pol II density along these genes suggests that the I/R-induced TNF-α and MCP-1 mRNA increases reflected, at least in part, increased transcription.

Figure 2.

Profiles of Pol II, H3K4m3, H2AZ, and BRG1 after I/R along the TNF-α gene. Renal cortical chromatin was prepared from mice subjected to unilateral I/R (■). Renal cortical chromatin from the contralateral kidney of the same mouse was used as control ( ). (A) Levels at the TNF-α first (exon 1) and last (exon 4) exons were assessed using matrix ChIP assays.24,25 (B) Levels measured in an intergenic region 5 kb downstream of the end of the TNF-α gene served as a control. Data are percentage of input DNA, mean ± 1 SD (n = 3 mice).

). (A) Levels at the TNF-α first (exon 1) and last (exon 4) exons were assessed using matrix ChIP assays.24,25 (B) Levels measured in an intergenic region 5 kb downstream of the end of the TNF-α gene served as a control. Data are percentage of input DNA, mean ± 1 SD (n = 3 mice).

Figure 3.

Profiles of Pol II, H3K4m3, H2A.Z, and BRG1 after I/R along the MCP-1 gene. Renal cortical chromatin was prepared from mice subjected to unilateral I/R (■). Renal cortical chromatin from contralateral kidney of the same mouse was used as control ( ). (A) Levels at the MCP-1 first (exon 1) and last (exon 3) exons were assessed using matrix ChIP assays. (B) Levels measured in an intergenic region 5 kb downstream of the end of the MCP-1 gene served as a control. Data are percentage of input DNA, mean ± 1 SD (n = 3 mice).

). (A) Levels at the MCP-1 first (exon 1) and last (exon 3) exons were assessed using matrix ChIP assays. (B) Levels measured in an intergenic region 5 kb downstream of the end of the MCP-1 gene served as a control. Data are percentage of input DNA, mean ± 1 SD (n = 3 mice).

Activation of gene expression is often associated with specific changes in chromatin structure that are important for induction of transcription.12,26–29 Trimethylation of lysine 4 of histone H3, H3K4m3, is one of the best studied covalent modifications that mark an open chromatin.30 Like Pol II, H3K4m3 levels are highest near the transcription start sites.12,28,31 We previously described increased H3K4m3 levels along several genes in renal cortex from different mouse models of ARF.10,25 Recently, an increase in H3K4m3 was also reported in response to hypoxia in hepatocytes.32 In this study, H3K4m3 levels at the first and last exons of the TNF-α gene were higher in postischemic kidneys, compared with contralateral controls (P < 0.003 and P < 0.01; respectively; Figure 2A). Furthermore, H3K4m3 in the intergenic 3′ 5-kb flanking region was very low and not different between the clamped and contralateral kidneys (Figure 2B), serving as a negative internal control. Interestingly, the differences between the injured and control kidneys remained at 3 but not 7 d after I/R. Similar results were obtained along the MCP-1 gene locus (Figure 3). These results suggest that whereas transcription of TNF-α and MCP-1 genes remains enhanced in the injured kidney, the classical H3K4m3 mark of open chromatin does not remain higher. This observation suggests that there is evolution of epigenetic processes to maintain genomic access after injury.

The H2A.Z histone variant is highly enriched at sites of active transcription,33 and the substitution of H2A.Z for the canonical H2A histone is increased with stimulation of transcription.29 At transcribed loci, the H2A.Z levels are highest at the transcription start site.33 Two hours after I/R, H2A.Z levels at the TNF-α gene were higher in the I/R kidneys versus their contralateral controls (Figure 2A). Unlike H3K4m3, these differences were sustained for 7 d. The H2A.Z density in the intergenic 3′ 5-kb flanking region were low and not different between the clamped and control contralateral kidneys (Figure 2B; negative internal control). Similar results were obtained along the MCP-1 gene locus (Figure 3). These results provide further evidence that (1) in response to I/R, the chromatin environments encompassing the TNF-α and MCP-1 genes are altered and (2) these differences persist for some (H2A.Z) but not all (H3K4m4) epigenetic marks for at least 1 wk after injury induction.

The ATP-dependent SWI/SNF multisubunit chromatin remodeling complexes are important in the regulation of transcription.13,29 With respect to our results (Figures 2 and 3) and those obtained from yeast14,34 to mammals,29,35 SWI/SNF complexes play a role in the replacement of H2A with H2A.Z. SWI/SNF complexes contain either the BRG1- or the BRM-ATPase catalytic subunit and several BRG-associated factors.13 The induction of the erythropoietin gene in response to hypoxia depends on BRG1 recruitment to this locus.21 Recruitment of BRG1 is also required for the induction of heme oxygenase 1 gene transcription in response to oxidative stress.20 BRG1 recruitment also plays a role in the transcriptional regulation of inflammatory mediators, including TNF-α36,37; therefore, we next assessed BRG1 levels along the TNF-α locus in response to I/R. These studies revealed higher levels of BRG1 at the first and last TNF-α exons in injured kidneys, compared with contralateral controls. These effects were observed as early as 2 h after I/R and were sustained for 1 wk. The BRG1 levels in the intergenic 3′ 5-kb flanking region were low and not different between the clamped and contralateral kidneys (Figure 2B). Similar results were obtained along the MCP-1 gene locus (Figure 3). Thus, the time course of increased levels of BRG1 along the TNF-α and MCP-1 loci is similar to that observed for Pol II and H2A.Z. Matrix ChIP observations suggest that similar epigenetic mechanisms underlie the increased transcription of TNF-α and MCP-1 genes in response to renal ischemia (Figure 1). These observations also suggest that the inducible recruitment of BRG1 plays a role in the induction of these genes in response to renal ischemia.

Simulated I/R in Cultured Proximal Tubule Cells Alters Chromatin and Enhances Recruitment of Pol II and BRG1 along TNF-α and MCP-1 Genes

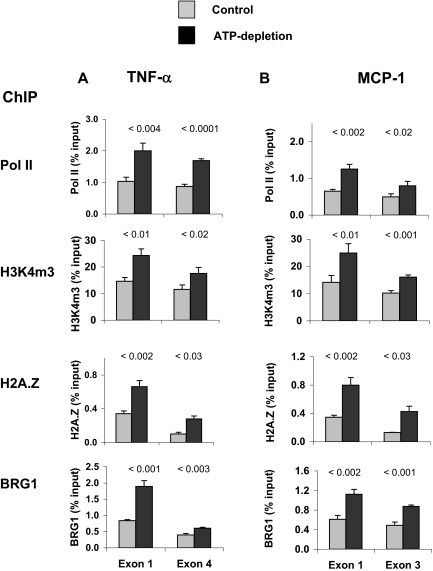

The combination of antimycin A (AA) and 2-deoxyglucose (DOG) depletes intracellular ATP, and this has been used to simulate oxygen deprivation in cultured cells.23,38 For example, AA treatment stimulates TNF-α mRNA and protein synthesis in HK-2 cells,23 recapitulating the in vivo proinflammatory mediator expression in response to ischemia. Thus, this system is a potentially useful model to define epigenetic and transcriptional mechanisms that promote cytokine/chemokine expression in response to hypoxic stress. We used matrix ChIP assay24,25 to compare Pol II, BRG1, and chromatin profiles along TNF-α and MCP-1 genes in untreated and in reversibly ATP-depleted HK-2 cells (AA + DOG for 4 h, followed by 2 h of ATP recovery [AA + DOG washout]; Figure 4). As in the case of renal ischemia (Figures 2 and 3), ATP depletion in HK-2 cells increased Pol II density along both the TNF-α (Figure 4A) and MCP-1 (Figure 4B) genes. This observation suggests that the reversible ATP depletion–induced cytokine/chemokine mRNA increases in HK-2 cells (Figure 5) is, at least in part, transcription dependent. As in the case of in vivo I/R (Figures 2 and 3), the ATP-mediated increase in Pol II density along TNF-α and MCP-1 genes was associated with higher levels of H3K4m3 and H2A.Z at these loci. In addition, there was an injury-mediated recruitment of BRG1 to these genes, which may play a role in the increased expression of TNF-α and MCP-1 in response to ATP depletion. This possibility was tested in the next series of experiments.

Figure 4.

(A and B) Effects of ATP depletion on density profiles of BRG1, Pol II, H3K4m3, and H2A.Z at the TNF-α (A) and MCP-1 (B) genes in proximal tubule HK-2 culture. Cells were subjected to 4 h of ATP depletion and 2 h of recovery (ATP depletion; see the Concise Methods section) (). Simultaneously treated cells, subjected to the same experimental protocol but without a previous ATP depletion (AA + DOG exposure), served as controls (Control). Chromatin was isolated and sheared. Density of given factors and marks at the first and the last exons of TNF-α and MCP-1 genes were assessed using matrix ChIP assays. Data are percentage of input DNA, mean ± 1 SD (n = 3 experiments).

Figure 5.

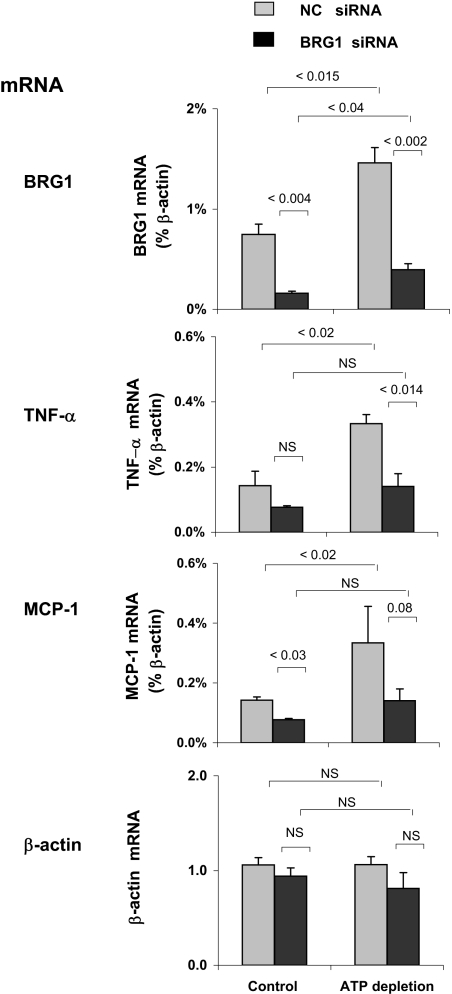

Effects of siRNA BGR1 knockdown on the ATP depletion–induced expression of TNF-α and MCP-1 genes in proximal tubule HK-2 cell culture. After transfection with either BRG1 siRNA (■) or noncomplementary (NC) siRNA ( ), HK-2 cells were treated either without (Control) or with (ATP depletion AA + DOG). Total RNA was extracted and reverse-transcribed, and transcript levels were assessed by real-time PCR done in triplicate using specific primers. mRNA levels are expressed as percentage of β-actin transcript. Data are means ± 1 SD (n = 3 experiments).

), HK-2 cells were treated either without (Control) or with (ATP depletion AA + DOG). Total RNA was extracted and reverse-transcribed, and transcript levels were assessed by real-time PCR done in triplicate using specific primers. mRNA levels are expressed as percentage of β-actin transcript. Data are means ± 1 SD (n = 3 experiments).

Knockdown of BRG1 Attenuates Injury-Induced TNF-α and MCP-1 mRNA Expression in Proximal Tubule HK-2 Cells

We used small interfering RNA (siRNA) knockdown to examine the role of BRG1 in the aforementioned changes (Figure 5). ATP depletion increased BRG-1 mRNA expression. Transfection of cells with BRG1 siRNA decreased BRG1 mRNA levels by approximately 75% in both control (P < 0.004) and ATP-depleted (P < 0.002) cells (Figure 5). In response to ATP depletion, there was a >2× increase in TNF-α (P < 0.02) and MCP-1 (P < 0.02) mRNAs in cells transfected with noncomplementary (NC) siRNA. In cells transfected with siRNA BRG1 for 24 h, the constitutive and inducible levels of both TNF-α and MCP-1 mRNAs were greatly decreased. In contrast, there was no change in β-actin mRNA expression in response to injury, and the levels of β-actin transcripts were not different between NC and BRG1 siRNA-transfected cells. Consistent with previous studies,20,29,36,37,39 these results suggest that the BRG1 chromatin remodeler regulates expression of inducible subsets of genes. The increased expression of TNF-α and MCP-1 genes in response to renal ischemia (Figure 1) that is associated with increased co-recruitment of Pol II and BRG1 to these loci (Figures 2 and 3) suggests that BRG1 plays a role in injury-induced transcription. This point was addressed next.

Knockdown of BRG1 Attenuates Injury-Induced Recruitment of Pol II to TNF-α and MCP-1 Genes in Proximal Tubule HK-2 Cells

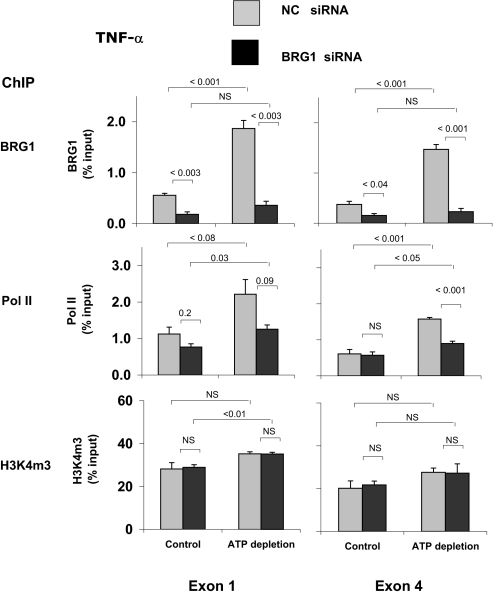

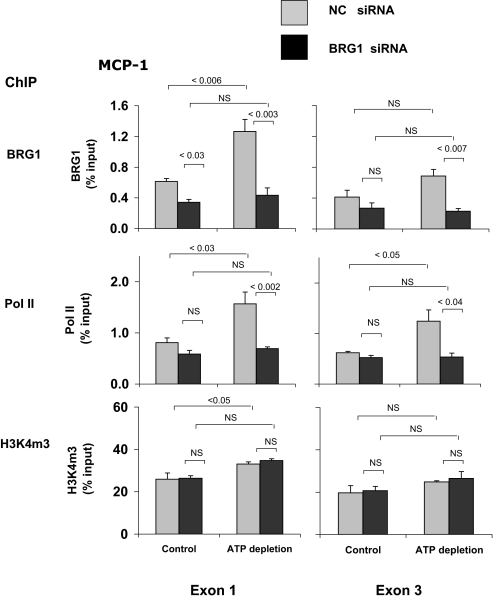

Reversible ATP depletion caused a more than three-fold increase in the density of BRG1 at the first and last exons of the TNF-α gene (P < 0.001 and P < 0.001, respectively; Figure 6). There was 40 to 80% decrease in BRG1 density at the TNF-α locus in cells transfected with BRG siRNA under baseline conditions. Furthermore, the ATP depletion–mediated BRG1 increase was prevented. Similar effects of BRG1 siRNA were seen at the MCP-1 gene (Figure 7). Together with the renal I/R data (Figures 2 and 3), this experiment indicates that ischemia increases recruitment of the BRG1 chromatin remodeler to the TFN-α and MCP-1 genes in proximal tubule cells.

Figure 6.

Effects of siRNA-induced BGR1 knockdown on the ATP depletion–induced co-recruitment of Pol II and BRG1 to the TNF-α gene in HK-2 cells. Cells were transfected with either BRG1 siRNA (■) specific or NC siRNA ( ). After transfection, HK-2 cells were treated either without (Control) or with (ATP depletion) AA + DOG; chromatin was extracted and sheared. Density at the TNF-α first (exon 1) and last (exon 4) exons were assessed using matrix ChIP assay. Data are percentage of input DNA, mean ± 1 SD (n = 3 experiments).

). After transfection, HK-2 cells were treated either without (Control) or with (ATP depletion) AA + DOG; chromatin was extracted and sheared. Density at the TNF-α first (exon 1) and last (exon 4) exons were assessed using matrix ChIP assay. Data are percentage of input DNA, mean ± 1 SD (n = 3 experiments).

Figure 7.

Effects of siRNA BGR1 knockdown on the ATP depletion–induced co-recruitment of Pol II and BRG1 to the MCP-1 gene in HK-2 cells. Cells were transfected with either BRG1 siRNA (■) specific or NC siRNA ( ). After transfection, HK-2 cells were treated either without (Control) or with (ATP depletion) AA + DOG; chromatin was extracted and sheared. Density at the MCP-1 first (exon 1) and last (exon 3) exons were assessed using matrix ChIP assay. Data are percentage of input DNA, mean ± 1 SD (n = 3 experiments).

). After transfection, HK-2 cells were treated either without (Control) or with (ATP depletion) AA + DOG; chromatin was extracted and sheared. Density at the MCP-1 first (exon 1) and last (exon 3) exons were assessed using matrix ChIP assay. Data are percentage of input DNA, mean ± 1 SD (n = 3 experiments).

In agreement with the ChIP results from postischemic kidneys (Figure 2), reversible ATP depletion increased Pol II density at the first (P < 0.08) and last (P < 0.001) exons of the TNF-α gene (Figure 6). BRG1 knockdown reduced both the constitutive and the inducible recruitment of Pol II to the TNF-α gene. Similar results were obtained along the MCP-1 gene (Figure 7). In sum, these results suggest that the increased expression of TNF-α and MCP-1 transcripts in response to reversible ATP depletion in HK-2 cells (Figure 5) is, at least in part, transcriptionally mediated and that this effect depends on the recruitment of BRG1 to these genes. That BRG1 is also recruited to TNF-α and MCP-1 genes in vivo (Figures 2 and 3) suggests that BRG1 plays a role in expression of TNF-α and MCP-1 genes after in vivo renal I/R (Figure 1). Unlike the effects on Pol II, changes in the levels of BRG1 recruitment to the TNF-α (Figure 6) and MCP-1 (Figure 7) genes had no effects on H3K4m3. This suggests a hierarchically ordered series of epigenetic events that enhance chromatin access to transcribing Pol II, as suggested in other studies.12,14,17,40 The lack of BRG1 effect on the level of H3K4m3 suggests that in this chain of events, H3K4m3 changes may operate upstream and are independent of BRG1.17

Discussion

Here, we show that 30 min of renal ischemia increases the expression of TNF-α and MCP-1 mRNAs and that these changes persist for up to 1 wk (Figure 1). The prolonged duration of these mRNA changes was associated with comparably long-lasting increases in Pol II and BRG1 recruitment to these proinflammatory genes (Figures 2 and 3). In our in vitro model of reversible proximal tubule ATP depletion (Figure 4), siRNA knockdown of BRG1 blocked injury-induced expression of TNF-α and MCP-1 mRNAs (Figure 5) and decreased Pol II and BRG1 recruitment to these genes (Figures 6 and 7). These results provide evidence for the role of BRG1 in the sustained transcription of TNF-α and MCP-1 genes in the kidney in the aftermath of renal ischemia.

Given the complexity of epigenetic mechanisms,27,41 it seems plausible that multiple chromatin alterations could account for sustained increases in TNF-α and MCP-1 gene transcription that follows renal ischemia (Figures 1 through 3). In this (Figures 2 and 3) and in previous studies,10,25 we found changes in histone marks and the deposition of H2A.Z histone variant along ARF-induced genes, thereby supporting this hypothesis. Others have reported that renal I/R demethylates 5-methylcytosine in the cytosine phosphoguanine (5mCpG) dinucleotides within the NF-κB–binding sites contained in the complement C3 promoter, a process that coincides with a rapid increase in renal C3 synthesis.42 Presumably, this epigenetic modification exposes docking sites for NF-κB binding. Induction of 5mCpG demethylation of a subset of genes could be one of the epigenetic changes that follow hypoxia.43 Although not examined here, DNA methylation/demethylation could also be involved in the regulation of TNF-α and MCP-1 gene expression after ischemia. We found that, unlike the sustained increase in the H2A.Z levels, the H3K4m3 mark returned to control levels by 7 d after I/R (Figures 2 and 3). This observation may indicate that whereas a subset of epigenetic processes initiates chromatin changes, different sets of events maintain the open chromatin state. If so, then the persistently higher BRG1 levels along the TNF-α and MCP-1 genes suggest that BRG1 could be involved in both the initiation and the maintenance of Pol II access and elongation. BRG1 is a component of numerous chromatin-modifying complexes.13,44 These observations are consistent with the suggestion that BRG1 is involved in multiple epigenetic events.

BRG1 is a large protein (predicted molecular weight 185 kD). In addition to its evolutionarily conserved ATPase domain, BRG1 contains domains that mediate multiple interactions with components of SWI/SNF complexes as well as a host of other proteins.13,44 BRG1 does not directly bind to DNA. Instead, BRG1 recruitment to target loci is indirect and mediated through the association of BRG1 and/or other SWI/SNF components with DNA-binding proteins, such as transcription factors, co-activators, and histone tails. Transcription factors, such as nuclear receptors, are thought to play a role in the recruitment of BRG1 to promoters of genes.20,29,37,45 BRG1 is also found at enhancer sites.46 At the promoter and enhancer regions, BRG1 likely serves to open access to DNA-binding transcription factors. These results expand on our understanding of this issue, because we found that BRG1 also binds along the entire transcribed regions of TNF-α and MCP-1 genes. Indeed, this achieved a pattern that was similar to that observed for Pol II (Figures 2 through 4, 6, and 7). This new insight could potentially have mechanistic relevance for Pol II binding and, hence, gene transcription rates. Elongating Pol II carries a large molecular cargo, but, thus far, there is no evidence that BRG1-SWI/SNF travels with the polymerase. Instead, upon induction and before Pol II binding, SWI/SNF complexes are recruited to histone tails along transcribed regions17 to remove the nucleosomal barrier, allowing efficient polymerase elongation.47,48 Future studies will address such a possibility and search for BRG1 docking sites along the proinflammatory genes in response to acute kidney injury and how BRG1 recruitment to these genes may affect cell phenotype in response to injury.

In conclusion, this study has presented new evidence that I/R-mediated TNF-α and MCP-1 gene induction is associated with changes in the histone profiles along these genes (most notably, increases in H2A.Z and H3K4m3). Furthermore, there is a parallel recruitment of both BRG1 and Pol II to these sites. Because BRG1 knockdown in HK-2 cells reduced Pol II binding, as well as TNF-α and MCP-1 mRNAs, a mechanistic link between BRG1, Pol II binding, and, ultimately, gene transcription seems to exist. This suggests a novel pathway by which I/R elicits an inflammatory response. It also allows new potential therapeutic approaches (e.g., interruption of BRG1 enzymatic activity) to mitigate postischemic renal injury, potentially circulating cytokine levels, and multiorgan failure. The technological and computational advances that are currently being made in this area provide exciting new opportunities to explore fully such issues.

Concise Methods

In Vivo I/R Protocol

Male CD 1 mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA; 30 to 35 g), maintained under routine vivarium conditions and subjected to institutional animal care and use committee–approved protocols, were used for all experiments. In brief, mice were anesthetized and subjected to a midline abdominal incision under sterile conditions. Left renal ischemia was induced with an atraumatic microvascular clamp applied to the renal pedicle. After 30 min of vascular occlusion, the clamp was released and reperfusion of the entire kidney was assessed visually (by loss of global cyanosis). A 30-min ischemic insult was selected for study because it induces moderately severe but reversible ischemic kidney damage. At variable times after ischemia, the mice were re-anesthetized and the kidneys were resected and processed for analyses. With the unilateral ischemia protocol, azotemia is not predicted. As previously documented,23 the right nonischemic, contralateral (control) kidney recapitulates what is seen in sham-operated kidneys and, hence, served as an internal control.

In Vitro “Chemical Ischemia” (ATP depletion) Experimental Protocol

The HK-2 immortalized proximal tubule cell culture maintained in keratinocyte serum-free medium was seeded into T75 flasks, as described previously.38 Culture conditions included 100 U/ml penicillin plus 25 μg/ml streptomycin. For experimentation, the cells were seeded into six-well Costar plates and then studied approximately 18 h later.

To assess the effects of reversible ATP depletion in HK-2 cells, we used AA-induced mitochondrial inhibition (7.5 μM) + DOG-induced (20 mM) inhibition of glycolysis, as described previously.23,38 After 4 h of AA + DOG exposure, ATP depletion was reversed by removal of the cell culture medium, washing with fresh medium, and then allowing a 2-h recovery period.

siRNA Knockdown Experiments

siRNA knockdowns were done using siRNA Gene Silencing Santa Cruz Protocol (http://www.scbt.com/protocols.html). Briefly, cells were grown in six-well plates to 30 to 50% confluence. Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and either BRG1 siRNA (sc-29827; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) or NC siRNA (sc-37007; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) Transfection Reagents was diluted separately with siRNA Transfection Medium (Opti-MEM I; Invitrogen). After 5 min of incubation, the diluted siRNA and Lipofectamine 2000 were combined and the mixture was incubated for another 30 min at room temperature. The mixture was then overlain onto the medium bathing cells in the wells. After 12 to 24 h, the overlay was aspirated and replaced with fresh culture medium for additional 24 to 48 h before mRNA and ChIP experiments.

RNA Extraction

TRIzol was used to purify RNA according to the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen). Excess TRIzol was used to separate clearly the RNA and DNA phases. Total extracted RNA was dissolved in 20 μl of sterile water and stored at −80°C. RNA concentrations were measured with a spectrophotometer (Bio Mate3; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and the 260/280 ratio of RNA was >1.7.

RT-PCR

First-strand cDNA was synthesized by priming 1 μg of total RNA with 10 μM random hexamers (Promega, Madison, WI) by heating at 65°C for 10 min and snap-cooling on ice. Reverse transcription (37°C for 1 h) was performed in the presence of 10 mM each of dATP, dCTP, dTTP, and dGTP (Invitrogen), 4 μl of 5× first-strand buffer (Invitrogen), 0.1 M dithiothreitol (Invitrogen), 200 U of Maloney-murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen), and 20 U of RNase inhibitor (Invitrogen). After the reaction, the sample was heated at 94°C for 5 min and cooled on ice; after addition of 180 μl of water, samples were stored at −80°C. RT cDNA samples were measured either with competitive (Figure 1) or real-time PCR (Figure 5). List of RT-PCR primers is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

List and sequences of RT-PCR primers

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| Human | |

| TNF-α exon 4 (ID 7124) | |

| left | 5′-TAGATGGGCTCATACCAGGG-3′ |

| right | 5′-CCGTCTCCTACCAGACCAAG-3′ |

| MCP-1 exon 3 (ID 6347) | |

| left | 5′-AGCTGCAGATTCTTGGGTTG-3′ |

| right | 5′-AAGGAGATCTGTGCTGACCC-3′ |

| BRG1 exon 2/3 (ID 6597) | |

| left | 5′-CCCATTCCTTTCATCTGGTTG-3′ |

| right | 5′-ACCCTCAGGACAACATGCAC-3′ |

| β-actin exon 4/5 (ID 60) | |

| left | 5′-AGAGCTACGAGCTGCCTGAC-3′ |

| right | 5′-AAGGTAGTTTCGTGGATGCC-3′ |

| Mouse | |

| TNF-α exon 1 (ID 21926) | |

| left | 5′-ACCGTCAGCCGATTTGCTATCTCA-3′ |

| right | 5′-TGTAGGGCAATTACAGTCACGGCT-3′ |

| MCP-1 exon 1/2 (ID 20296) | |

| left | 5′-TCACCTGCTGCTACTCATTCACCA-3′ |

| right | 5′-AAAGGTGCTGAAGACCCTAGGGCA-3′ |

| GAPDH (ID 14433) | |

| left | 5′-CTGCCATTTGCAGTGGCAAAGTGG-3′ |

| right | 5′-TTGTCATGGATGACCTTGGCCAGG-3′ |

Sonication of Renal Cortex Chromatin

Approximately 25 mg of minced renal cortex was fixed with formaldehyde (final concentration 1.42% in PBS for 15 min; 22°C) and then quenched with 125 mmol/L glycine (5 min, 22°C). The cross-linked tissues were then extensively washed with PBS (4°C). For shearing the chromatin, the washed cross-linked tissue pellets were resuspended in IP buffer.49 The shearing was done using either Masonic 3000 microprobe (1 ml of IP buffer, six rounds of sonication power 5, 15 s, on ice)49,50 or Diagenode Bioruptor (100 μl of IP buffer, 30 rounds for 30 s on/30 s off, high power, 4°C). The suspension was cleared by centrifugation at 12,000 × g (10 min at 4°C), and the supernatant, representing sheared chromatin, was aliquotted and stored at −80°C.

Microplate-Based Matrix ChIP Platform

ChIP assays were done using the Matrix ChIP platform in 96-well polystyrene high-binding capacity microplates as described previously.24,25,49 ChIP DNA samples were assayed by quantitative PCR. All PCR reactions were run in triplicate. PCR primers were designed using the Primer3 software (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/). At least four samples were run for each determination. PCR calibration curves were generated for each primer pair from a dilution series of total mouse or human sheared genomic DNA. The PCR primer efficiency curve was fit to cycle threshold versus log (genomic DNA dilutions) using an r2 best fit. DNA concentration values for each ChIP and input DNA samples were calculated from their respective average cycle threshold values. Final results are expressed as percentage input DNA.24 Matrix ChIP PCR primers are shown in Table 2 and the list of antibodies in Table 3.

Table 2.

List and sequences of matrix ChIP PCR primers

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| Human | |

| TNF-α (ID 7124) | |

| exon 1 | |

| right | 5′-CCACGATCAGGAAGGAGAAG-3′ |

| left | 5′-CCTGGAAAGGACACCATGAG-3′ |

| exon 4 | |

| right | 5′-TAGATGGGCTCATACCAGGG-3′ |

| left | 5′-CCGTCTCCTACCAGACCAAG-3′ |

| MCP-1 (ID 6347) | |

| exon 1 | |

| right | 5′-GAATGAAGGTGGCTGCTATG-3′ |

| left | 5′-AACCCAGAAACATCCAATTCTC-3′ |

| exon 3 | |

| right | 5′-AGCTGCAGATTCTTGGGTTG-3′ |

| left | 5′-AAGGAGATCTGTGCTGACCC-3′ |

| Mouse | |

| TNF-α (ID 21926) | |

| exon 1 | |

| right | 5′-GCAGGTTCTGTCCCTTTCAC-3′ |

| left | 5′-AGTGCCTCTTCTGCCAGTTC-3′ |

| exon 4 | |

| right | 5′-TATGGCTCAGGGTCCAACTC-3′ |

| left | 5′-GCTCCAGTGAATTCGGAAAG-3′ |

| intergenic 3′ 5 kb | |

| right | 5′-CCAGACTCAGAACTAGGACCG-3′ |

| left | 5′-GGTAAACAGGAAGCTGGGTG-3′ |

| MCP-1 (ID 20296) | |

| exon 1 | |

| right | 5′-GCCAACACGTGGATGCTC-3′ |

| left | 5′-AGCCAACTCTCACTGAAGCC-3′ |

| exon 3 | |

| right | 5′-TTAAGGCATCACAGTCCGAG-3′ |

| left | 5′-TTGAATGTGAAGTTGACCCG-3′ |

| intergenic 3′ 5 kb | |

| right | 5′-TTTCATCATGGCAGGGAAAC-3′ |

| left | 5′-GCTGCTATCTTGGACTATGCG-3′ |

Table 3.

List of antibodies used in matrix ChIP

| Antibody | Type | Source | Catalog | Amount/ChIP (μg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pol II CTD (4H8) | Monoclonal | Gene Tex | GTX25408 | 0.25 |

| H2A.Z | Rabbit polyclonal | Abcam | ab4174 | 0.50 |

| H3K4m3 | Rabbit polyclonal | Abcam | ab8580 | 0.50 |

| BRG1 | Rabbit polyclonal | Upstate | 07-478 | 0.50 |

Statistical Analysis

All results are presented as means ± 1 SD. Statistical comparisons were made by unpaired t test (significance judged by P < 0.05). When multiple statistical comparisons were made, the Bonferroni correction was applied.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by research grants from the National Institutes of Health (DK-R37-45978 and GM45134 [K.B.] and DK-R37-38431 and DK-68520 [R.Z.]).

We thank Ali Johnson for expert technical support on this project.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

References

- 1.Zager RA, Johnson AC, Lund S: ‘Endotoxin tolerance’: TNF-alpha hyper-reactivity and tubular cytoresistance in a renal cholesterol loading state. Kidney Int 71: 496–503, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zager RA, Johnson AC, Hanson SY, Lund S: Acute nephrotoxic and obstructive injury primes the kidney to endotoxin-driven cytokine/chemokine production. Kidney Int 69: 1181–1188, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zager RA, Johnson AC, Lund S, Hanson S: Acute renal failure: Determinants and characteristics of the injury-induced hyperinflammatory response. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 291: F546–F556, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramesh G, Zhang B, Uematsu S, Akira S, Reeves WB: Endotoxin and cisplatin synergistically induce renal dysfunction and cytokine production in mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F325–F332, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leemans JC, Stokman G, Claessen N, Rouschop KM, Teske GJ, Kirschning CJ, Akira S, van der Poll T, Weening JJ, Florquin S: Renal-associated TLR2 mediates ischemia/reperfusion injury in the kidney. J Clin Invest 115: 2894–2903, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grigoryev DN, Liu M, Hassoun HT, Cheadle C, Barnes KC, Rabb H: The local and systemic inflammatory transcriptome after acute kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 547–558, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramesh G, Reeves WB: Inflammatory cytokines in acute renal failure. Kidney Int Suppl S56–S61, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelly KJ: Acute renal failure: Much more than a kidney disease. Semin Nephrol 26: 105–113, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dear JW, Yasuda H, Hu X, Hieny S, Yuen PS, Hewitt SM, Sher A, Star RA: Sepsis-induced organ failure is mediated by different pathways in the kidney and liver: Acute renal failure is dependent on MyD88 but not renal cell apoptosis. Kidney Int 69: 832–836, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naito M, Bomsztyk K, Zager RA: Endotoxin mediates recruitment of RNA polymerase II to target genes in acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 1321–1330, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dressler GR: Epigenetics, development, and the kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 2060–2067, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li B, Carey M, Workman JL: The role of chromatin during transcription. Cell 128: 707–719, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberts CW, Orkin SH: The SWI/SNF complex: Chromatin and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 4: 133–142, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mizuguchi G, Shen X, Landry J, Wu WH, Sen S, Wu C: ATP-driven exchange of histone H2AZ variant catalyzed by SWR1 chromatin remodeling complex. Science 303: 343–348, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morillon A, Karabetsou N, Nair A, Mellor J: Dynamic lysine methylation on histone H3 defines the regulatory phase of gene transcription. Mol Cell 18: 723–734, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mellor J: Dynamic nucleosomes and gene transcription. Trends Genet 22: 320–329, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wysocka J, Swigut T, Xiao H, Milne TA, Kwon SY, Landry J, Kauer M, Tackett AJ, Chait BT, Badenhorst P, Wu C, Allis CD: A PHD finger of NURF couples histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation with chromatin remodelling. Nature 442: 86–90, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bultman S, Gebuhr T, Yee D, La Mantia C, Nicholson J, Gilliam A, Randazzo F, Metzger D, Chambon P, Crabtree G, Magnuson T: A Brg1 null mutation in the mouse reveals functional differences among mammalian SWI/SNF complexes. Mol Cell 6: 1287–1295, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phelan ML, Sif S, Narlikar GJ, Kingston RE: Reconstitution of a core chromatin remodeling complex from SWI/SNF subunits. Mol Cell 3: 247–253, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang J, Ohta T, Maruyama A, Hosoya T, Nishikawa K, Maher JM, Shibahara S, Itoh K, Yamamoto M: BRG1 interacts with Nrf2 to selectively mediate HO-1 induction in response to oxidative stress. Mol Cell Biol 26: 7942–7952, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang F, Zhang R, Beischlag TV, Muchardt C, Yaniv M, Hankinson O: Roles of Brahma and Brahma/-related gene 1 in hypoxic induction of the erythropoietin gene. J Biol Chem 279: 46733–46741, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cao CC, Ding XQ, Ou ZL, Liu CF, Li P, Wang L, Zhu CF: In vivo transfection of NF-kappaB decoy oligodeoxynucleotides attenuate renal ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. Kidney Int 65: 834–845, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zager RA, Johnson AC, Hanson SY, Lund S: Ischemic proximal tubular injury primes mice to endotoxin-induced TNF-alpha generation and systemic release. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 289: F289–F297, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flanagin S, Nelson JD, Castner DG, Denisenko O, Bomsztyk K: Microplate-based chromatin immunoprecipitation method, Matrix ChIP: A platform to study signaling of complex genomic events. Nucleic Acids Res 36: e17, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Naito M, Bomsztyk K, Zager RA: Renal ischemia-induced cholesterol loading: Transcription factor recruitment and chromatin remodeling along the HMG CoA reductase gene. Am J Pathol 174: 54–62, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boyle AP, Davis S, Shulha HP, Meltzer P, Margulies EH, Weng Z, Furey TS, Crawford GE: High-resolution mapping and characterization of open chromatin across the genome. Cell 132: 311–322, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kouzarides T: Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell 128: 693–705, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nelson JD, Flanagin S, Kawata Y, Denisenko O, Bomsztyk K: Transcription of laminin γ1 chain gene in rat mesangial cells: Constitutive and inducible RNA polymerase II recruitment and chromatin states. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294: F525–F533, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.John S, Sabo PJ, Johnson TA, Sung MH, Biddie SC, Lightman SL, Voss TC, Davis SR, Meltzer PS, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Hager GL: Interaction of the glucocorticoid receptor with the chromatin landscape. Mol Cell 29: 611–624, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bernstein BE, Kamal M, Lindblad-Toh K, Bekiranov S, Bailey DK, Huebert DJ, McMahon S, Karlsson EK, Kulbokas EJ, 3rd, Gingeras TR, Schreiber SL, Lander ES: Genomic maps and comparative analysis of histone modifications in human and mouse. Cell 120: 169–181, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heintzman ND, Stuart RK, Hon G, Fu Y, Ching CW, Hawkins RD, Barrera LO, Van Calcar S, Qu C, Ching KA, Wang W, Weng Z, Green RD, Crawford GE, Ren B: Distinct and predictive chromatin signatures of transcriptional promoters and enhancers in the human genome. Nat Genet 39: 311–318, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson AB, Denko N, Barton MC: Hypoxia induces a novel signature of chromatin modifications and global repression of transcription. Mutat Res 640: 174–179, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barski A, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Roh TY, Schones DE, Wang Z, Wei G, Chepelev I, Zhao K: High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell 129: 823–837, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luk E, Vu ND, Patteson K, Mizuguchi G, Wu WH, Ranjan A, Backus J, Sen S, Lewis M, Bai Y, Wu C: Chz1, a nuclear chaperone for histone H2AZ. Mol Cell 25: 357–368, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wong MM, Cox LK, Chrivia JC: The chromatin remodeling protein, SRCAP, is critical for deposition of the histone variant H2AZ at promoters. J Biol Chem 282: 26132–26139, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramirez-Carrozzi VR, Nazarian AA, Li CC, Gore SL, Sridharan R, Imbalzano AN, Smale ST: Selective and antagonistic functions of SWI/SNF and Mi-2beta nucleosome remodeling complexes during an inflammatory response. Genes Dev 20: 282–296, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang M, Qian F, Hu Y, Ang C, Li Z, Wen Z: Chromatin-remodelling factor BRG1 selectively activates a subset of interferon-alpha-inducible genes. Nat Cell Biol 4: 774–781, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ryan MJ, Johnson G, Kirk J, Fuerstenberg SM, Zager RA, Torok-Storb B: HK-2: An immortalized proximal tubule epithelial cell line from normal adult human kidney. Kidney Int 45: 48–57, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vicent GP, Ballare C, Nacht AS, Clausell J, Subtil-Rodriguez A, Quiles I, Jordan A, Beato M: Induction of progesterone target genes requires activation of Erk and Msk kinases and phosphorylation of histone H3. Mol Cell 24: 367–381, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wysocka J, Swigut T, Milne TA, Dou Y, Zhang X, Burlingame AL, Roeder RG, Brivanlou AH, Allis CD: WDR5 associates with histone H3 methylated at K4 and is essential for H3 K4 methylation and vertebrate development. Cell 121: 859–872, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bernstein BE, Meissner A, Lander ES: The mammalian epigenome. Cell 128: 669–681, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parker MD, Chambers PA, Lodge JP, Pratt JR: Ischemia-reperfusion injury and its influence on the epigenetic modification of the donor kidney genome. Transplantation 86: 1818–1823, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shahrzad S, Bertrand K, Minhas K, Coomber BL: Induction of DNA hypomethylation by tumor hypoxia. Epigenetics 2: 119–125, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trotter KW, Archer TK: The BRG1 transcriptional coregulator. Nucl Recept Signal 6: e004, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ni Z, Karaskov E, Yu T, Callaghan SM, Der S, Park DS, Xu Z, Pattenden SG, Bremner R: Apical role for BRG1 in cytokine-induced promoter assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102: 14611–14616, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ni Z, Abou El, Hassan M, Xu Z, Yu T, Bremner R: The chromatin-remodeling enzyme BRG1 coordinates CIITA induction through many interdependent distal enhancers. Nat Immunol 9: 785–793, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao J, Herrera-Diaz J, Gross DS: Domain-wide displacement of histones by activated heat shock factor occurs independently of Swi/Snf and is not correlated with RNA polymerase II density. Mol Cell Biol 25: 8985–8999, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Petesch SJ, Lis JT: Rapid, transcription-independent loss of nucleosomes over a large chromatin domain at Hsp70 loci. Cell 134: 74–84, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nelson JD, Denisenko O, Bomsztyk K: Protocol for the fast chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) method. Nat Protoc 1: 179–185, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nelson JD, Denisenko O, Sova P, Bomsztyk K: Fast chromatin immunoprecipitation assay. Nucleic Acids Res 34: e2, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]