Abstract

The mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of epilepsy, a chronic neurological disorder that affects approximately 1 percent of the world population, are not well understood1–3. Using a mouse model of epilepsy, we show that seizures induce elevated expression of vascular cell adhesion molecules and enhanced leukocyte rolling and arrest in brain vessels mediated by the leukocyte mucin P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1) and leukocyte integrins α4β1 and αLβ2. Inhibition of leukocyte-vascular interactions either with blocking antibodies, or in mice genetically deficient in functional PSGL-1, dramatically reduced seizures. Treatment with blocking antibodies following acute seizures prevented the development of epilepsy. Neutrophil depletion also inhibited acute seizure induction and chronic spontaneous recurrent seizures. Blood-brain barrier (BBB) leakage, which is known to enhance neuronal excitability, was induced by acute seizure activity but was prevented by blockade of leukocyte-vascular adhesion, suggesting a pathogenetic link between leukocyte-vascular interactions, BBB damage and seizure generation. Consistent with potential leukocyte involvement in the human, leukocytes were more abundant in brains of epileptics than of controls. Our results suggest leukocyte-endothelial interaction as a potential target for the prevention and treatment of epilepsy.

Experimental data from animal models as well as human evidence indicate that seizures can lead to neuronal damage and cognitive impairement2, 3. However, the molecular mechanisms leading to seizures and epilepsy are not well understood. Recent data suggests that inflammation may play a role in the pathogenesis of epilepsy4, 5. For instance, elevation in inflammatory cytokines are seen in the central nervous system (CNS) and plasma in experimental models of seizures and in clinical cases of epilepsy4, 5. Moreover, CNS inflammation is associated with breakdown in the blood-brain barrier (BBB), and BBB leakage has been implicated both in the induction of seizures and in the progression to epilepsy6–9. Leukocyte recruitment is a hallmark of and a point of therapeutic intervention in tissue inflammation10,11, but a role for leukocyte-endothelial interactions in seizure pathogenesis has not been explored. Here we have employed an established mouse model of epilepsy to ask whether leukocyte-endothelial interactions can also contribute to seizure pathogenesis.

Systemic administration of pilocarpine induces status epilepticus (SE) in mice typically lasting a few hours12, 13. After a latent (seizure-free) phase, mice that experienced SE go on to develop epilepsy characterized by spontaneous recurrent seizures (SRS)12, 13. In addition to hippocampal damage, pilocarpine-induced seizures in rodents also cause widespread cortical and subcortical lesions14.

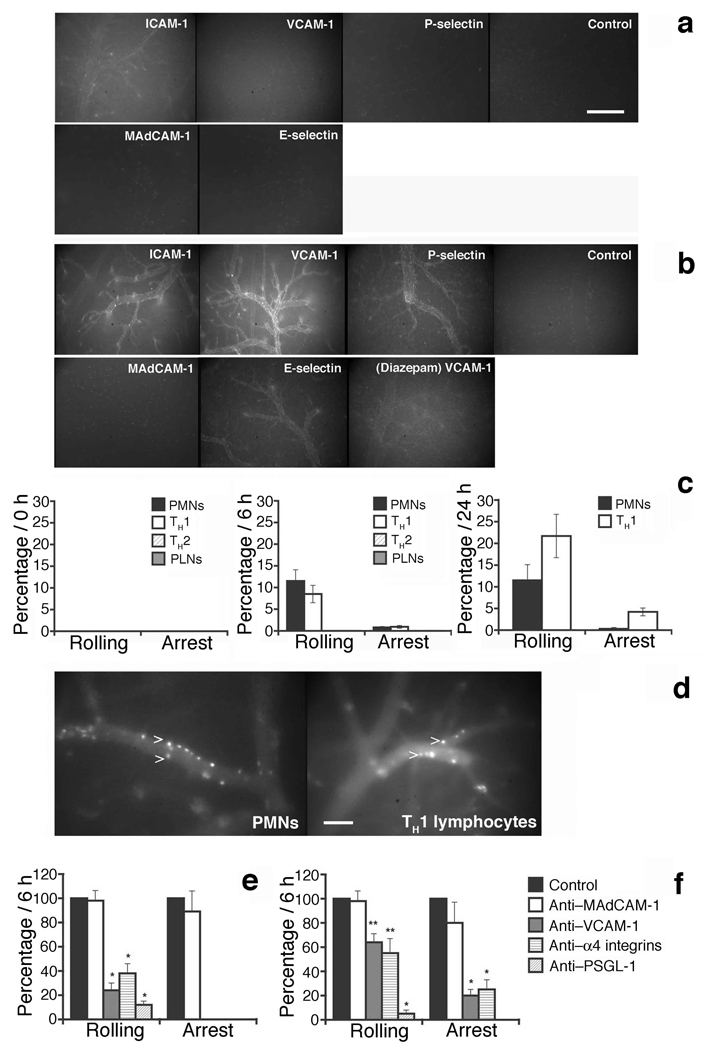

Seizure activity in this model led to induction of vascular adhesion molecules for leukocytes. Vessels in control brains expressed low amounts of ICAM-1 (intercellular adhesion molecule-1), but VCAM-1 (vascular cell adhesion molecule-1), E-selectin and P-selectin were below the limits of detectability (Fig. 1a). As shown in Figure 1a, b ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 were dramatically upregulated following seizure induction, with the highest levels observed 24 h and 7 d post-SE (Fig 1a, b, Supplementary Table 1a). Pharmacologic suppression of SE with Diazepam, a benzodiazepine with CNS depressant properties, prior to pilocarpine injection substantially but not completely prevented the upregulation of VCAM-1 (Fig. 1b), suggesting that electrical hyperactivity contributes to high VCAM-1 expression in brain vessels potentially in combination with a direct vascular effect of pilocarpine itself9. P-selectin and E-selectin were also induced on venular endothelium after seizures (Fig. 1a, b and Supplementary Table 1a). Thus elicited seizure activity is associated with inflammatory changes in the CNS vasculature, changes that could support enhanced adhesion of circulating leukocytes and consequent amplification of vascular damage.

Figure 1. Alpha4 integrin, VCAM-1 and PSGL-1 dependence of PMN and TH1 cell interactions with brain endothelium after SE.

a, b. Expression of adhesion molecules in cortical vessels was evaluated by in vivo staining and fluorescence microscopy before (Baseline) (a) and 6 h after the onset of seizure activity induced by pilocarpine (b). Isotype-matched mAb served as a control. Suppression of SE was achieved by administration of 3 mg/Kg Diazepam i.p. 20 min before pilocarpine injection (Diazepam) (b). Scale bar: 200 µm.

c, e, f. The frequency of rolling interactions or sticking behavior of fluorescently labeled PMNs and lymphocyte subpopulations in cortical venules was studied before pilocarpine injection (0 h) and at 6 h and 24 h after SE onset by in situ videomicroscopy15. The percentage of total cells shown on Y axis was calculated as described in Supplementary methods. The number of venules and animals per group analyzed are provided in Supplementary Table 1b, c. Mean ± SEM are shown. PLNs, freshly isolated peripheral lymph node cells (resting lymphocytes).

d. Adherent PMNs 6 h post-SE and TH1 cells at 24 h post SE are shown in cerebral vessels (arrows). Scale bar: 100 µm.

e, f. Anti-adhesion molecule mAbs were used to block leukocyte or endothelial adhesion molecules at 6 h after SE as described at Supplementary methods (Intravital microscopy subsection). PMNs are shown in e and TH1 cells are shown in f. Groups were compared with control using Kruskall-Wallis test followed by Bonferoni correction of P. **P<0.01; *P<0.001.

Direct pilocarpine treatment of leukocytes does not render them hyperadhesive (Supplementary Fig. 1a), but pilocarpine induction of seizures dramatically enhanced leukocyte adhesion to CNS vessels in vivo (Fig. 1c, d). Intravital microscopy studies performed in cortical venules15 showed that PMN (polymorphonuclear leukocytes) displayed efficient rolling and arrest after SE onset (Fig. 1c, d). Resting lymphocytes did not interact, (Fig. 1c), while TH (T helper)1, polarized cells rolled and stuck efficiently after seizures (Fig. 1c, d). PMN arrest was consistently higher at 6 h, while TH1 cells interacted more efficiently at 24 h than at 6 h after seizures, consistent with progression from acute to subacute inflammation during the 24 h period after SE-induced damage (Fig. 1c). Rolling velocities (Vroll) and the frequency distribution of Vroll in velocity classes are provided at Supplementary Fig. 1b and Supplementary Table 1. Interestingly, in vitro polarized TH2 cells, known to lack functional P-selectin ligand, did not roll or stick in brain vessels (Fig. 1c).

Rolling interactions and arrest of PMN cells after SE were dramatically inhibited by antibody blockade of α4 integrin or its vascular counter ligand VCAM-1, or by blockade of P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1) or its principal vascular ligand P-selectin (Fig. 1e; Supplementary Fig. 1c and d, Supplementary Discussion [1]). Rolling and arrest of TH1 cells were also reduced by α4 or VCAM-1 blockade after SE (Fig. 1f), and were almost completely blocked by antibodies to PSGL-1 and P-selectin, as well (Fig. 1f and data not shown). MAb (monoclonal antibody) to MAdCAM-1 (mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1) had no significant effect, excluding a role for the intestinal trafficking receptor α4β7 integrin (Fig. 1e, f and Supplementary Figs. 1c). These results demonstrate that the integrin α4β1 and the selectin ligand PSGL-1 mediate vascular-leukocyte adhesive interactions in cerebral vessels following SE. We therefore set out to ask whether these leukocyte adhesion mechanisms might contribute to seizure induction and/or epileptogenesis in this model.

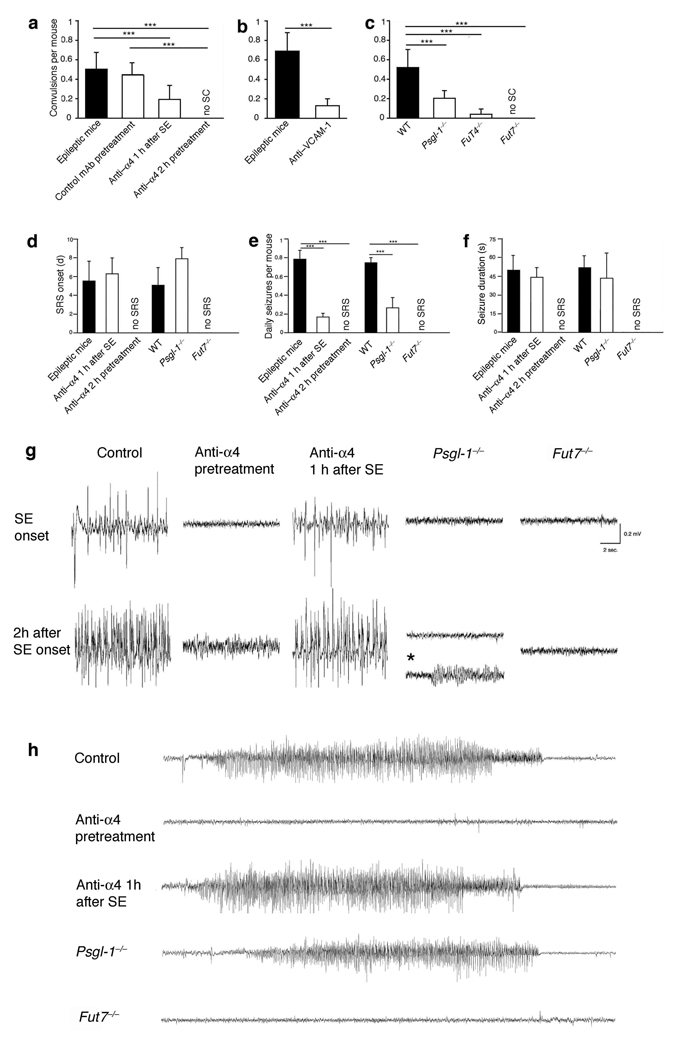

To mimic therapeutic intervention in response to severe acute seizures, we initially evaluated the effect of adhesion blockade after SE on the subsequent development of recurrent seizures. One hour of SE is sufficient to lead to chronic spontaneous seizures in the pilocarpine model in mouse and rat13, 16, 17 (supplementary Discussion [2]). Therefore, pilocarpine-injected C57Bl/6 mice were allowed to convulse for one hour (stage 5 of Racine’s Scale18), and then were treated with α4 integrin-specific mAb i.p (Fig. 2). Mice also received α4 integrin-specific mAb every other day for 20 days. As expected, treatment with antibody to α4 integrin after SE onset had no effect on the character and duration of ongoing SE as assessed visually or by EEG analysis after pilocarpine treatment (Fig. 2g, Supplementary Fig. 2b and data not shown). However, video monitoring revealed a dramatic reduction of spontaneous convulsions during the chronic period (from day 5 to 20 after pilocarpine injection) in mice treated with α4 integrin-specific antibody (Fig. 2a). EEG telemetry confirmed a consistent reduction in frequency of spontaneous recurrent seizures (SRS) during the chronic phase in the treated mice (Fig. 2e). The latency of the first SRS, and the duration of individual seizure events when they occurred, was similar in the treatment and control groups (Fig. 2d, f, h). Neuropathological findings showed post-SE alterations including increased ventricle volume and hippocampal shrinkage, but there was a statistically significant decrease in neuronal cell loss in somatosensory cortex and hippocampus subfields (Figure 3). In addition, 30 days after SE, animals treated with antibody to α4 integrin exhibited a slight reduction of exploration behavior compared to normal animals, but a significant preservation of the behavior compared to epileptic mice (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 2a). Post-SE antibody against the α4β1 ligand VCAM-1 was also effective in preventing spontaneous convulsions during the chronic phase (Fig. 2b). Thus our data suggest that α4 and its ligand VCAM-1 contribute to pathogenic events required for epileptogenesis in this model.

Figure 2. Effect of blockade or deficiency in leukocyte adhesion mechanisms on convulsions and seizures.

In a-c visual monitoring of mean number of daily spontaneous convulsions (SC) per mouse was performed from day 5–20 after pilocarpine administration. Pilocarpine treated WT mice received no treatment (“epileptic mice”), or were injected i.p. either 1 h after SE-onset with 400 µg α4 integrin-specific mAb or with 150 µg VCAM-1-specific mAb, to model therapy; or 2 h prior to pilocarpine injection with 400 µg α4 integrin-specific mAb (pre-treatment regimen). In both instances treated mice also received antibody (200 µg anti-α4 or control mAb and 150 µg anti-VCAM-1) every other day for 20 days. An isotype-matched control antibody was used as control (a). 10–12 animals/group were monitored for SC for 6 h/day between day 5 and 20 after SE. One representative experiment from a series of 4 (a), 2 (b) and 3 (c) with similar results is shown.

In d–f EEGs for each animal were acquired 24 h/day from day 0–20 after pilocarpine administration. Behaviorally, SRS were characterized in our mice by head nodding, forelimb clonus, rearing, and falling. d, days, s, seconds (g) Twenty-sec EEG recordings early after initial seizures and at the end of the second h are shown. Theta activity was occasionally observed in Psgl-1−/− animals (asterisk, fourth column, second line). (h) Recordings of representative SRS are shown. For d–h data are representative from one experiment with 3 mice/group from two experiments with similar results. ***P<0.001.

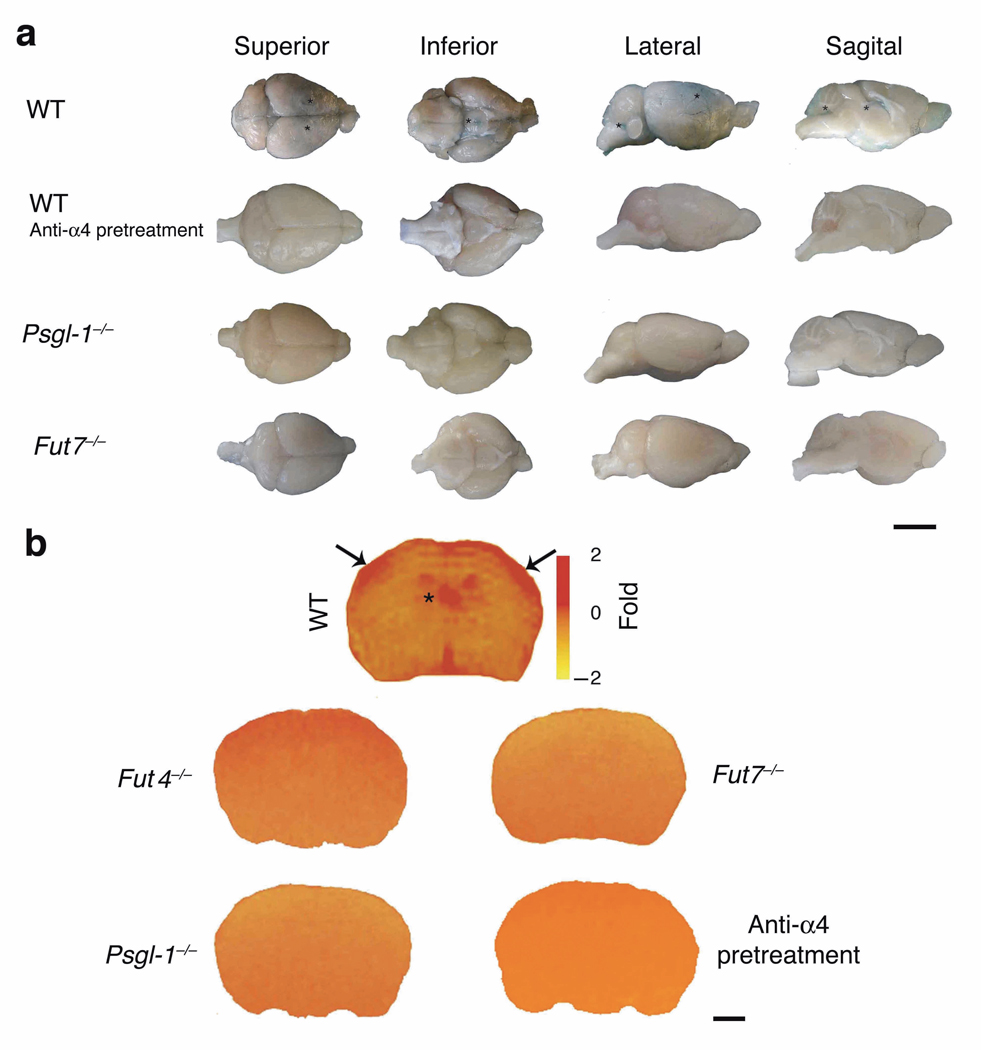

Figure 3. Effect of blockade or deficiency in leukocyte adhesion mechanisms on CNS histopathology.

Epilepsy-induced structural changes and effects on neuronal cell density alterations were analyzed at 30 days after SE in healthy animals and in mice injected with pilocarpine: control (C57Bl/6, WT) mice, anti-α4 treated animals and Psgl-1−/− and Fut7−/− mice. For quantitative evaluation, the number of Nissl stained cell bodies was counted in four sections/animal (3 animals/group) using regions of interest (ROI) sampling. The ROI was delimited by a rectangular frame which was placed within the sampled cortical and hippocampal areas, using upper-left exclusion lines. In the somatosensory (SS) cortex, the rectangular frame was placed vertically throughout the cortical thickness, superficial (II-III) (SS1) and deep (V-VI) layers (SS2) of the cortex. See also the Supplementary Methods for details. Mean ± SEM are shown for stereological counts. Statistical comparison of anti-α4-treated groups or Psgl-1−/− and Fut7−/− groups with Control/WT epileptic condition was performed using a two-tail t-test. *P<0.04. CA, corpus ammonis. Scale bar corresponds to 30 µm.

Surprisingly, when antibody to α4 integrin was given 2 h before injection of pilocarpine, it completely prevented convulsions (Fig. 2a). In the first hour after pilocarpine injection, anti-α4 integrin pretreated mice displayed sporadic tremors and oral mastication (stage 2 of the Racine’s Scale18), but no further tremors or SE developed, and no delayed spontaneous convulsions were detected from day 5 through day 20 (mice also received 200 µg mAb to α4 integrin every other day for 20 days, to mimic a therapeutic regimen) (Figure 2a). Moreover, pre-treated mice displayed no EEG alterations indicative of SE or SRS following pilocarpine-injection (Figure 2d–h, Supplementary Fig. 2a). Predictably, initiation of anti-α4 integrin treatment prior to pilocarpine led to a significant decrease of neuronal cell loss in somatosensory cortex and hippocampus and prevented delayed cognitive impairment (Figure 3, Supplementary Fig. 2e, Supplementary Table 2a). In support of these results, blockade of αL integrin, or of its endothelial ligand ICAM-1 consistently reduced leukocyte-endothelial interactions and prevented convulsions (Supplementary Figure 1d, e). In contrast, control anti-CD45 mAb or anti-α4β7 or anti-CD4 mAbs had no effect on SE induction, chronic disease, or cognitive deterioration (Figure 2a, Supplementary Fig. 2e and Supplementary Table 2b for anti-CD45 mAb and data not shown).

Intravenously administered antibody should be largely excluded from the CNS by the BBB prior to SE, but we could not formally exclude an effect of leaked anti-α4 or anti-VCAM-1 mAbs on nervous tissue. To address this issue as well as to assess the role of selectin-mediated interactions, we took advantage of genetically modified mice deficient in PSGL-1 (Psgl-1−/− mice) or in α-1,3-fucosyltransferases (FucTs), FucT-VII and FucT-IV, enzymes required to generate functional selectin-binding carbohydrates (Fut4−/− and Fut7−/− mice)19. Consistent with the inhibitory effects of anti-α4 treatment we observed a dramatic reduction in the incidence of SE and of subsequent spontaneous convulsions and of SRS as monitored visually or electroencephalographically in Psgl-1−/− and Fut−/− mice (Figure 2c and Fig 2d–h, and Supplementary Figure 2c, d, Supplementary movie). Psgl-1−/− and Fut7−/− animals also showed a significant reduction of neuronal damage and a considerable preservation of the behavior compared to epileptic mice (Figure 3, Supplementary Fig. 2e, Supplementary Table 2c). Since PSGL-1 is selectively expressed on leukocytes and endothelium20, inhibition of seizures in Psgl-1−/− mice further supports a direct or indirect role for leukocyte adhesion in seizure generation in this model, and rules out primary neuronal or glial effects of anti-adhesion treatments. To further confirm the role of leukocytes, we used a granulocyte-specific antibody to deplete neutrophils before pilocarpine administration. Neutrophil depletion caused a significant reduction of SE and spontaneous recurrent convulsions (Supplementary Fig. 2f), confirming that leukocytes contribute to seizure pathogenesis.

Recent studies have shown that BBB breakdown induces epileptiform activity6–9, 21. Moreover, pilocarpine induced seizure activity is not only associated with BBB leakage in vivo, but may in fact require leakage of serum components: pilocarpine induces neuronal hyperactivity in ex vivo brain slices, but only in the context of elevated K+ levels mimicking plasma leakage into the CNS9. BBB leakage could also enhance access of pilocarpine itself to the extravascular compartment, although this is unlikely to be sufficient for epileptogenesis in the absence of plasma leakage9 (Supplementary discussion [3]). We therefore evaluated BBB leakage in our model. Pilocarpine-induced BBB opening was largely prevented in mice with leukocyte adhesion blockade, whether by antibody or by genetic interference with leukocyte adhesion pathways (Fig. 4a, b).

Figure 4. Inhibition or deficiency of leukocyte adhesion pathways maintains the integrity of the BBB.

(a) Evans Blue (EB) extravasation was evaluated 18–24 h after pilocarpine injection. In WT (control) mice, EB leakage (asterisks) was observed macroscopically in brains, after removal of the meninges, in the parietal cortex and in particular in the territories relative to the medial cerebral artery (black asterisks) in the superior and lateral views; in the pituitary gland pedunculus (where the BBB is more permeable) in the inferior view; and, finally, in the choroid plexus of the lateral ventricles and in the fourth ventricle as in the sagittal view. WT animals injected only with methylscopolamine did not show any leakage (data not shown). Anti-α4 pretreatment as well as PSGL1- or FucT-VII deficiency (Psgl-1−/− and Fut7−/− mice) prevented BBB leakage. Representative brains are shown from one of 2 experiments, 3 mice/condition, with similar results. Scale bar: 4 mm. (b) BBB alterations post-SE were studied in control (C57Bl/6/, WT mice), and anti-α4 treated animals and in Psgl-1−/− and Fut−/− mice at 24 h after pilocarpine injection. BBB permeability was studied by the mean of intravenously administered Magnevist® (Nmethylglucamine salt of gadolinium complex of diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid) a paramagnetic iron oxide contrast agent in MRI. Pseudo-color maps evidencing contrast agent spreading are shown. Representative brains are shown from one of two experiments (3mice/condition) with similar results. Scale bar: 2 mm.

Taken together, the demonstrated elicitation of neuronal hyperactivity by BBB leakage6–9, 21 and the inhibition of BBB breakdown by blockade of leukocyte-endothelial interaction, shown here, suggest a mechanism for synergistic and potentially self-reinforcing interactions between endothelial activation, leukocyte adhesion, BBB opening and seizure generation. A cycle of seizure-induced inflammation and inflammation-mediated stimulation may amplify the initial effects, leading to chronic changes and recurrent seizure activity (Supplementary Fig. 3a, Supplementary Discussion [4]). The general relevance of our findings remains to be determined in other models of epilepsy.

We evaluated human cortical CNS tissue from subjects with epilepsy and found elevated brain leukocyte numbers compared to non-epileptic controls, suggesting a possible role for leukocyte adhesion in humans as well (Supplementary Figure 4 and Supplementary Table 3). Current pharmacological treatments for epilepsy inhibit neuronal excitability but do not address the inflammatory component of pathogenesis. Anti-adhesion therapies based on humanized antibodies10, 22,23 or other available approaches would allow clinical evaluation of adhesion pathways as targets for preventing epilepsy, particularly following inflammatory inciting events such as stroke or traumatic brain injury.

In conclusion, our results suggest that vascular inflammatory mechanisms and leukocyte-endothelial adhesion can contribute to the pathogenesis of seizures and epilepsy, and show that inhibition of leukocyte-vascular interactions can have preventive as well as therapeutic effects in a mouse model of this debilitating disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

MAbs anti-α4 integrin PS/2, anti-VCAM-1 MK 2.7, anti-ICAM-1 YN 1.1.7.4, anti-LFA-1 TJB 213, anti-MAdCAM-1 MECA 367, anti-CD45 30G12 were from American Type Culture Collection or were produced in our labs. Anti-PSGL-1 (4RA10) was kindly provided by Dr. D. Vestweber, Max Plank Institute, Muenster, Germany.

Mice

C57Bl/6 young males were obtained from Charles River, Italy. Fut4−/− and Fut7−/− mice were obtained as previously described24, 25. Psgl-1−/− mice were prepared as described26. Psgl-1−/− and Fut7−/− mice were on a C57Bl/6 genetic background (backcrossed for at least 9 generations). Mice were housed and used according to current European Community rules. Experiments on mice were approved by the research committees from the University of Verona and Italian National Institute of Health.

Induction of seizures and epilepsy

We employed young male C57BL/6 mice (30–50 days of age, weight range: 19–23 gr) were obtained from Harlan and maintained on a 12 h light/dark inverted schedule, with access to food and water ad libitum, and habituated to the experimenters for at least two weeks prior to the procedures employed in the present study. The experiments received authorization from the Italian Ministry of Health, and were conducted following the principles of the NIH Guide for the Use and Care of Laboratory Animals, and the European Community Council (86/609/EEC) directive. All animals injected with pilocarpine were pretreated with methyl-scopolamine (1 mg/kg, i.p., Sigma, Germany) to minimize peripheral muscarinic effects. Thirty minutes later, mice received 300 mg/kg pilocarpine (Sigma, Germany) i.p. diluted in 0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4 (PBS). Systemic administration of pilocarpine induced status epilepticus (SE) in mice with continuous seizure activity usually lasting 1–2 h. Behavioral observations of pilocarpine-induce seizures during SE were evaluated according to a modified version of Racine scale using categories 1–5, with 5 being the most severe12, 18. Then after a latent (seizure-free) phase of 1–2 weeks, mice go on to develop chronic epilepsy characterized by spontaneous convulsions (SC)12, 13. All mice that developed SE also developed spontaneous seizures as previously shown in C57Bl/6 mice12. Experiments in which more that 30% of the control animals died or did not develop SE after pilocarpine injection were not considered in this study. For in vivo staining studies of endothelial adhesion molecules, some mice were injected with Diazepam i.p. (3 mg/Kg) 20 min before pilocarpine administration to prevent SE. Mice with convulsions at 2 h after SE onset were injected with Diazepam to uniform SE duration to 2 h in all experimental groups.

Determination of BBB permeability by MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) analysis27

MRI experiments were performed using a Bruker Biospec Tomograph equipped with an Oxford, 33-cm-bore. Animals were anaesthetized and placed in prone position into a 7.2 cm transmitter birdcage coil. The signal was acquired by a 1.5 cm actively decoupled surface coil. The tail vein was cannulated for injection of contrast agent (Magnevist, Schering 100 micromol/kg). Multislice, T1-weighted Spin Echo images were acquired before and up to 24 min after injection of Magnevist. The acquisition parameters were: TR=350 ms; TE=14.4 ms; matrix size=128×128;FOV=3×3cm2. Twelve contiguous, 1 mm-thick slices were acquired to cover the whole-brain.

Determination of BBB permeability by Evans blue staining8

Evans Blue (EB) was intravenously (i.v.) administered via the tail vein (100 mg/kg i.v., Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) in awake, restrained animals (anesthesia was avoided in order to exclude artifact due to the direct effect of the anesthetic itself on the endothelium and blood flow). EB injection was performed 18–24 h after pilocarpine injection. Briefly, 30 min after the i.v. EB injection, animals were perfused by a solution of mixed aldehydes containing 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 (PBS). Brains were then removed excluding meninges and photographed on a stereo-microscope.

PMN preparation

Mouse bone marrow PMNs were isolated from femurs and tibias as previously described28. Briefly marrow cells were flushed from the bones using Hank’s balanced salt solution without Ca2+ and Mg2+ . After hypotonic lysis of erythrocytes cells were loaded on top of a Percoll discontinuous density gradient and, after centrifugation cells were harvested and washed before use. >80% of the isolated cells were Gr-1 positive cells in flow cytometry (data not shown).

Intravital microscopy15, 29

C56Bl/6 young males were purchased from Harlan-Nossan (Udine, Italy). At 6 h and 24 h after the onset of status epilepticus, mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection (10 ml/kg) of physiologic saline containing with ketamine (5 mg/ml) and xylazine (1 mg/ml). The recipient was maintained at 37 °C by a stage mounted strip heater Linkam CO102 (Olympus). A heparinized PE-10 polyethylene catheter was inserted into the right common carotid artery toward the brain. In order to exclude from the analysis the non cerebral vessels, the right external carotid artery and pterygopalatine artery, a branch from the internal carotid, were ligated. The scalp was reflected and the skull was bathed with sterile saline, and a 24 mm × 24mm coverslip was applied and fixed with silicon grease. A round chamber with 11 mm internal diameter was attached on the cover slip and filled with water.

The preparation was placed on a Olympus BX50WI microscope and a water immersion objective with long focal distance (Olympus Achroplan, focal distance 3.3 mm, NA 0.5 ∞) was used. More details regarding intravital microscopy studies are provided at Supplementary methods.

Statistics

Statistical analysis of the results, was performed by using Prism software. A two-tailed Student's t test was employed for statistical comparison of two samples. Multiple comparisons were performed employing Kruskall-Wallis test with the Bonferroni correction of P or by using ANOVA. Velocity histograms were compared using Man-Whitney U-test and Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Differences were regarded significant with a value of P<0.05.

The following methods are provided at Supplementary information: in vivo staining of endothelial adhesion molecules, in vitro adhesion assays, telemetry EEG, behavioral assessment, production of murine TH1 and TH2 cells, immunohistochemistry and human samples.

A scheme of the experimental procedures performed in mice is provided in Supplementary Fig. 3b.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank C. Laudanna for critically discussing the manuscript. This work was supported in part by grants from the Fondazione Cariverona; Italian Ministry of Education and Research (MIUR, PRIN), National Multiple Sclerosis Society, New York, NY, USA, Fondo Incentivazione Ricerca di Base (FIRB), Italy Italian Ministry of Health, Fondazione Italiana Sclerosi Multipla (FISM), University of Verona ex-60% MIUR (to G.C.); European Community [EU Research Grants LSH-CT-2006-037315 (EPICURE), thematic priority LIFESCIHEALTH; University of Verona ex-60% MIUR (to P.F.F.) and by National Institutes of Health grants (to E.C.B, L.X, R.P.M., J.B.L). L.O. was in part supported by a fellowship from FISM. The Authors are grateful to Silvia Fiorini, Ida Cwojdzinski, Paolo Bernardi, Michele Pellitteri, Serena Becchi, Luisa Andrello and Andrea Calbi for their invaluable help in the experimental procedures.

References

- 1.Strzelczyk A, Reese JP, Dodel R, Hamer HM. Cost of epilepsy: a systematic review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26:463–476. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200826060-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holmes GL. Seizure-induced neuronal injury: animal data. Neurology. 2002;59:S3–S6. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.9_suppl_5.s3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duncan JS. Seizure-induced neuronal injury: human data. Neurology. 2002;59:S15–S20. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.9_suppl_5.s15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vezzani A. Inflammation and epilepsy. Epilepsy Curr. 2005;5:1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1535-7597.2005.05101.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vezzani A, Granata T. Brain inflammation in epilepsy: experimental and clinical evidence. Epilepsia. 2005;46:1724–1743. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seiffert E, et al. Lasting blood-brain barrier disruption induces epileptic focus in the rat somatosensory cortex. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7829–7836. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1751-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ivens S, et al. TGF-beta receptor-mediated albumin uptake into astrocytes is involved in neocortical epileptogenesis. Brain. 2007;130:535–547. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Vliet EA, et al. Blood-brain barrier leakage may lead to progression of temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain. 2007;130:521–534. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marchi N, et al. In vivo and in vitro effects of pilocarpine: Relevance to Ictogenesis. Epilepsia. 2007;48:1934–1946. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01185.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luster AD, Alon R, von Andrian UH. Immune cell migration in inflammation: present and future therapeutic targets. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1182–1190. doi: 10.1038/ni1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ransohoff RM, Kivisakk P, Kidd G. Three or more routes for leukocyte migration into the central nervous system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2003;3:569–581. doi: 10.1038/nri1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shibley H, Smith BN. Pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus results in mossy fiber sprouting and spontaneous seizures in C57BL/6 and CD-1 mice. Epilepsy Res. 2002;49:109–120. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(02)00012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gröticke I, Hoffmann K, Löscher W. Behavioral alterations in the pilocarpine model of temporal lobe epilepsy in mice. Exp Neurol. 2007;207:329–349. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fabene PF, Marzola P, Sbarbati A, Bentivoglio M. Magnetic resonance imaging of changes elicited by status epilepticus in the rat brain: diffusion-weighted and T2-weighted images, regional blood volume maps, and direct correlation with tissue and cell damage. Neuroimage. 2003;18:375–389. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(02)00025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piccio L, et al. Molecular mechanisms involved in lymphocyte recruitment in brain microcirculation: critical roles for PSGL-1 and trimeric Galphai linked receptors. J. Immunol. 2002;168:,1940–1949. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.4.1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glien M, et al. Repeated low-dose treatment of rats with pilocarpine: low mortality but high proportion of rats developing epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2001;46:111–119. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(01)00272-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klitgaard H, Matagne A, Veneste-Goemaere J, Margineanu DG. Pilocarpine-induced epileptogenesis in the rat: impact of initial duration of status epilepticus on electrophysiological and neuropathological alterations. Epilepsy Res. 2002;51:93–107. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(02)00099-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Racine RJ. Modification of seizure activity by electrical stimulation. II. Motor seizure. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1972;32:281–294. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(72)90177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ley, Kansas G. Selectins in T-cell recruitment to non-lymphoid tissues and sites of inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:325–335. doi: 10.1038/nri1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ley K, Laudanna C, Cybulsky MI, Nourshargh S. Getting to the site of inflammation: the leukocyte adhesion cascade updated. Nat. Rev Immunol. 2007;7:678–689. doi: 10.1038/nri2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oby E, Janigro D. The blood-brain barrier and epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2006;47:1761–1774. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lebwohl M, et al. A novel targeted T-cell modulator, efalizumab, for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2004–2013. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Polman CH, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of natalizumab for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;354:899–910. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maly P, et al. The alpha(1,3)fucosyltransferase Fuc-TVII controls leukocyte trafficking through an essential role in L-, E-, and P-selectin ligand biosynthesis. Cell. 1996;86:643–653. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80137-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Homeister JW, et al. The alpha(1,3)fucosyltransferases FucT-IV and FucT-VII exert collaborative control over selectin-dependent leukocyte recruitment and lymphocyte homing. Immunity. 2001;15:115–126. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00166-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xia L, et al. P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1-deficient mice have impaired leukocyte tethering to E-selectin under flow. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:939–950. doi: 10.1172/JCI14151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Runge VM, et al. The use of Gd DTPA as a perfusion agent and marker of blood-brain barrier disruption. Magn Reson. Imaging. 1985;3:43–55. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(85)90008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lowell CA, Fumagalli L, Berton G. Deficiency of Src family kinases p59/61hck and p58c-fgr results in defective adhesion-dependent neutrophil functions. J. Cell Biol. 1996;133:895–910. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.4.895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Battistini L, et al. CD8± T cells from patients with acute multiple sclerosis display selective increase of adhesiveness in brain venules: a critical role for P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1. Blood. 2003;101:4775–4782. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Constantin G, et al. Chemokines trigger immediate beta2 integrin affinity and mobility changes: differential regulation and roles in lymphocyte arrest under flow. Immunity. 2000;13:759–769. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00074-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.