Abstract

Y-box protein (YB)-1 of the cold-shock protein family functions in gene transcription and RNA processing. Extracellular functions have not been reported, but the YB-1 staining pattern in inflammatory glomerular diseases, without adherence to cell boundaries, suggests an extracellular occurrence. Here, we show the secretion of YB-1 by mesangial and monocytic cells after inflammatory challenges. It should be noted that YB-1 was secreted through a non-classical mode resembling that of the macrophage migration inhibitory factor. YB-1 release requires ATP-binding cassette transporters, and microvesicles protect YB-1 from protease degradation. Two lysine residues in the YB-1 carboxy-terminal domain are crucial for its release, probably because of post-translational modifications. The addition of purified recombinant YB-1 protein to different cell types results in increased DNA synthesis, cell proliferation and migration. Thus, the non-classically secreted YB-1 has extracellular functions and exerts mitogenic as well as promigratory effects in inflammation.

Keywords: cold shock protein, YB-1, non-classical secretion, inflammation, microvesicles

Introduction

For several protein families involved in nucleotide processing, an extraordinary level of evolutionary conservation has been described. Their nuclear functions relate to the orchestration of transcription and modulation of DNA structures. For some of these proteins, extracellular occurrence and functions were identified; for example, heat-shock and high-mobility-group box (HMGB) proteins are secreted in inflammatory diseases (Bianchi & Manfredi, 2007). A pathophysiological relevance of extracellular HMGB1 in inflammatory diseases has been shown in sepsis, ischaemia reperfusion damage and atherosclerosis, with antibody-mediated HMGB1 neutralization having a protective role (Bianchi & Manfredi, 2007).

Y-box protein (YB)-1 is prototypic for the highly conserved, so-called, cold-shock protein family. It regulates gene transcription and RNA processing/translation together with other factors (Kohno et al, 2003; Raffetseder et al, 2003; Evdokimova et al, 2006). YB-1 protein attracted our interest because of its pro- as well as anti-inflammatory functions (Inagaki et al, 2005; Dooley et al, 2006). In experimental mesangioproliferative nephritis, YB-1 localization changes from nuclear to cytoplasmic in diseased animals, with the YB-1 staining pattern exceeding cellular boundaries (van Roeyen et al, 2005). This led us to propose an extracellular occurrence for YB-1 under inflammatory conditions.

Results And Discussion

Monocytic cells secrete YB-1 on LPS incubation

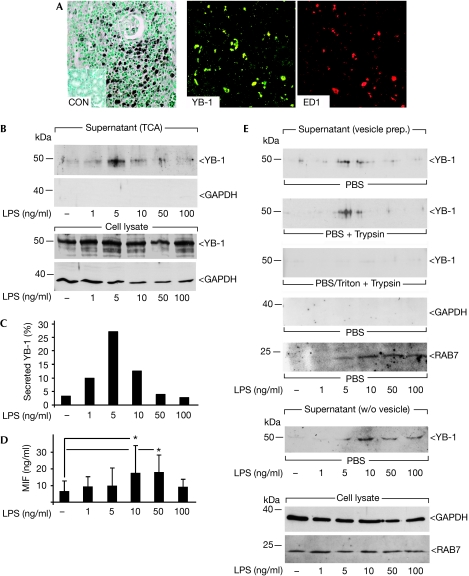

In an experimental model of acute kidney-transplant rejection (Kunter et al, 2003), ED1-positive monocytes and macrophages showed a high level of YB-1 expression (Fig 1A). Given the missing confinement of YB-1 to cell boundaries in mesangioproliferative disease (van Roeyen et al, 2005) and its strong expression by mononuclear cells, we suggested that YB-1 secretion might have occurred. Secretion of a nuclear protein seems unexpected at first; however, such a process is not unprecedented, given the secretion of transcription factor HMGB1 in inflammation, a protein with similar evolutionary conservation.

Figure 1.

Lipopolysaccharide induces YB-1 secretion in primary monocytic cells. (A) In acute kidney-transplant rejection, infiltrating monocytes are double immunopositive for YB-1 and ED1. The inset (left panel) shows immunohistochemical analyses carried out with healthy kidney. (B) LPS stimulation of primary monocytes leads to a concentration-dependent release of YB-1 into the supernatant. Detection was carried out with TCA-precipitated conditioned medium, (C) and quantified to 25% of the total cellular YB-1 content at maximum. (D) Macrophage migration inhibitory factor concentration in the supernatant is increased in a similar LPS concentration range. (E) LPS stimulation of monocytes with subsequent vesicle preparation (see supplementary Fig 2 online) enriches YB-1 protein. Vesicles successfully protect YB-1 against protease activity (trypsin, second panel). Detergent pretreatment (Triton X-100, third panel) disrupts vesicles and trypsin degrades YB-1. Spill-over of cytoplasmic protein is excluded by glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase detection (fourth panel) and proper vesicle preparation is verified by the presence of RAB7 (fifth panel). YB-1 was also detected in TCA-precipitated medium after removal of vesicular structures by centrifugation (sixth panel). Control for total cellular protein and intracellular RAB7 content is given in the lowest panel. CON, control; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MIF, macrophage migration inhibitory factor; TCA, trichloroacetic acid; w/o, without; YB, Y-box protein.

Primary human monocytes were exposed to increasing lipopolysaccharide (LPS) concentrations for 4 h and the supernatants were trichloroacetic acid (TCA)-precipitated. Immunoblotting showed dose-dependent secretion of YB-1, which peaked at a concentration of 5 ng/ml LPS (Fig 1B), whereas no non-specific cytosolic protein release, for example that of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase, was observed. A Trypan-blue exclusion assay confirmed that protein release was not due to a lack of cell integrity (viability >95%). By contrast, intracellular YB-1 protein levels essentially did not change after LPS exposure (Fig 2B, lower panel). Calculation of protein loading and band intensities indicated that approximately 25% of total YB-1 protein was secreted by primary monocytes on stimulation, using 5 ng/ml LPS (Fig 1C). Quantification of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF; Kleemann et al, 2000) in the same supernatant by ELISA indicated a similar dose response to LPS (Fig 1D). LPS-induced secretion of both YB-1 and MIF was also observed in MonoMac-6 (MM6) cells (supplementary Fig 1B–D online), underpinning the above findings. MM6 cells are well-characterized LPS-responsive monocytic cells. In this system, YB-1 secretion was also apparent in a narrow LPS concentration range between 1 and 7.5 ng/ml, which paralleled MIF secretion (supplementary Fig 1B,C online). Kinetic studies carried out at the peak LPS concentration of 5 ng/ml showed low-level baseline secretion of YB-1 up to 2 h, followed by an apparent marked LPS effect after 4 h (supplementary Fig 1D online).

Figure 2.

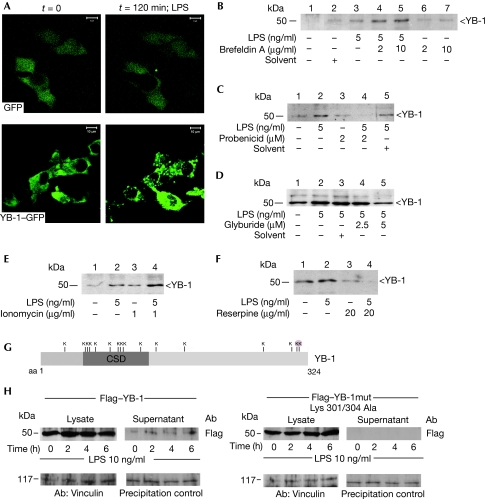

YB-1 is secreted through a non-classical, vesicle-mediated pathway by LPS-stimulated cells. (A) Confocal laser-scanning microscopy visualized formation of YB-1–GFP-enriched vesicles in 2 h after LPS stimulation of rMCs, however, this was not found for GFP-stimulation alone. Time-lapse live-cell microscopy was carried out for over 120 min with images taken every 2 min (supplementary videos 1 and 2 online). (B) Biochemical characterization of the YB-1 export mechanism was carried out with LPS-stimulated MM6 monocytic cells. Preincubation with brefeldin A as an inhibitor of the classical export pathway enhances YB-1 secretion. Preincubation with inhibitors of ATP-binding cassette transporters (C) probenicid and (D) glyburide reduces the release of YB-1. (E) The ionophore ionomycin superinduces LPS-dependent YB-1 secretion. (F) Disruption of the electrochemical gradient by reserpine successfully blocks the LPS effect on YB-1 secretion. (G) Schematic drawing of the YB-1 domains and distribution of 16 lysines (Ks) in the protein. (H) Expression plasmids for Flag–YB-1 and double-mutated Flag–YB-1 Lys301/304Ala proteins were introduced into rMCs and equal expression levels were determined by Flag antibody. After LPS stimulation a time-dependent release of Flag–YB-1, but not of mutated Flag–YB-1 (Lys301/304Ala), is detected with the supernatant (upper panels). Controls for cellular protein and precipitation efficiency are provided in the lower panels. CSD, cold shock domain; GFP, green fluorescent protein; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; mm6, MonoMac-6; rMCs, rat mesangial cells; YB, Y-box protein.

On the basis of earlier observations made for HMGB1 (Gardella et al, 2002), we addressed the possibility whether vesicles are involved in YB-1 release. Vesicles were prepared from supernatants on cell stimulation with LPS (supplementary Fig 2A online). Indeed, vesicle-enriched fractions contained YB-1 (Fig 1E), and intravesicular YB-1 was protected from protease digestion (trypsin), unless vesicles were solubilized by detergent (Triton X-100) preincubation (Fig 1E). Contamination with other cytosolic proteins was excluded, given the negative glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase immunoblot. Furthermore, successful vesicle enrichment was confirmed by anti-RAB7 western blot (Fig 1E). After the removal of vesicles by centrifugation, supernatants were analysed for YB-1 protein content. In fact, TCA precipitation showed the presence of YB-1 in these supernatants, indicating that after secretion vesicles disintegrate and YB-1 becomes freely available in the extracellular milieu (Fig 1E, sixth panel). Thus, monocytes stimulated by LPS release YB-1 within vesicles. Trypsin-digest experiments ruled out that YB-1 might have adhered non-specifically to the cytosolic side of the vesicular membrane. Importantly, YB-1 secretion, stimulated in a similar manner, was also observed in rat mesangial cells (rMCs). Mesangial cells share phenotypic and functional characteristics with monocytes (Mené et al, 1989) and have been shown to upregulate YB-1 under inflammatory conditions (van Roeyen et al, 2005). Consequently, we observed that the inflammation-related stimuli transforming growth factor-β and hydrogen peroxide also resulted in vesicular secretion of haemagglutinin-tagged YB-1 stably expressed in rMCs in a time- and dose-dependent manner (supplementary Fig 2B–D online). As, in this cell model, YB-1 was specifically detected through its haemagglutinin tag, any cross-reactivity with other cold-shock proteins could be excluded. Next, endogenous YB-1 release from rMCs was tested. Both LPS and platelet-derived growth factor-BB provoked a substantial release of YB-1 over a time range of 1–4 h (supplementary Fig 1A online).

YB-1 is secreted by an alternative secretion mode

Using confocal laser-scanning microscopy, intracellular vesicle formation with enriched levels of fluorescent YB-1–GFP (green fluorescent protein) fusion protein was detected within 2 h, but not in control cells expressing GFP alone (Fig 2A; see also live cell imaging in supplementary video online). These data hint at a non-classical secretion mode for YB-1, bypassing the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus, as first described by Rubartelli et al (1990) for interleukin-1β (IL-1β). For several inflammatory mediators (IL-1β, MIF, HMGB1, thioredoxin 1 and fibroblast growth factor 2), non-classical secretion has now been verified (reviewed by Nickel, 2003). All these proteins lack an amino-terminal signal-peptide sequence, which is required for endoplasmic reticulum/Golgi targeting. In fact, computer-based algorithms predict non-classical secretion of YB-1 and indicate the absence of a canonical N-terminal signal peptide motif. To investigate further the secretion mode of YB-1, we applied several biochemical approaches. We first noticed that preincubation with brefeldin A, which interferes with the classical secretion pathway, did not reduce, but instead, increased, the secretion of YB-1 (Fig 2B), as shown earlier for other leaderless proteins such as MIF and IL-1β (Rubartelli et al, 1990; Flieger et al, 2003). For non-classically secreted proteins, different export machineries have been described. For example, IL-1β and MIF secretion depends on ABC transporters, as indicated by an inhibition of the secretion of these mediators by glyburide or probenicid (Andrei et al, 1999; Flieger et al, 2003). We tested whether glyburide and probenicid would interfere with the secretion of YB-1. MM6 cells were incubated with these agents before LPS stimulation. Both glyburide and probenicid treatment resulted in a marked reduction of YB-1 secretion (Fig 2C,D). Protein exclusion of leaderless proteins has been described to occur through vesicle formation; for example, through exosomes, endolysosomes or microvesicle shedding (Andrei et al, 1999; Gardella et al, 2002). To confirm this question with respect to YB-1 secretion, we pursued two pharmacological approaches: one using ionomycin, which is a potent ionophore that induces degranulation in some cell types, and the other using reserpine, which can disrupt secretion by acting as an inhibitor of the ATP-dependent uptake of bioamines into vesicles. Ionomycin was found to have a stimulatory effect on the LPS-induced secretion of YB-1 (Fig 2E), whereas preincubation of MM6 cells with reserpine strongly reduced YB-1 secretion (Fig 2F), mirroring observations made earlier for IL-1β using similar drugs (Andrei et al, 1999). It should be noted that non-specific YB-1 release due to cell death was excluded in all experiments, as indicated by the lack of measurable lactate dehydrogenase release. Together, these results are in line with vesicle-mediated YB-1 secretion. We next coexpressed GFP–RAB7 and dsRed–YB-1 in mesangial cells. Whereas in non-stimulated cells dsRed–YB-1 is diffusely distributed throughout the cytosolic compartment, LPS stimulation led to intravesicular accumulation of YB-1 and to a notably partial, yet substantial, colocalization with GFP–RAB7 (supplementary Fig 3 online). This indicated that YB-1 secretion occurred through the endolysosomal compartment.

Acetylation of HMGB1 is an essential step for protein redistribution and its secretion (Bonaldi et al, 2003). YB-1 contains 16 lysine residues (Fig 2G). Two lysines at positions 301 and 304 at the carboxy-terminus of the protein are subject to acetylation (data not shown). Exchange of these lysines by alanines by using site-directed mutagenesis fully abrogates the secretion of Flag-tagged YB-1, which is otherwise seen at 2 h after LPS addition (Fig 2H).

In summary, these results unanimously show that YB-1 is secreted through an alternative secretion mode similar to that observed for other leaderless proteins such as HMGB1, IL-1β or MIF.

Extracellular YB-1 stimulates migration and proliferation

Extracellular occurrence of YB-1 raises the question of its functional relevance. YB-1 orchestrates proliferation, for example through DNA polymerase-α expression (Kohno et al, 2003; En-Nia et al, 2005). Therefore, we studied the proliferative response of different cell lines on stimulation with extracellular YB-1. rMCs as well as human kidney 2 (HK-2) cells were assayed for their DNA synthesis rates by using 5-bromodeoxyuridine incorporation. Synchronized serum-depleted cells were stimulated with purified rYB-1 (0.1 μg/ml and 1 μg/ml) or FCS (10% vol/vol, as a positive control). Addition of rYB-1 increased the DNA synthesis rate of both cell lines in a dose-dependent manner (supplementary Fig 3A,B online). rYB-1 at 1 μg/ml had a stimulatory effect of 90% (HK-2) and 40% (rMC), and the results were 35% and 60%, respectively, with FCS. Specificity of the pro-proliferative effect of rYB-1 was underscored by blockade of the YB-1 effect with a monoclonal YB-1 antibody (van Roeyen et al, 2005). Similar results were obtained with breast epithelial cells of cancerous (BT20) and non-cancerous (MCF12A) origin (data not shown). Addition of YB-1 for 24 h increased the proliferation rate of both cell lines to a similar degree as that achieved by the addition of epidermal growth factor (EGF; positive control). Denatured YB-1 had only a marginal influence on proliferation, ruling out any effect because of endotoxin contamination of the YB-1 preparation.

Besides mitotic events, cell motility is an important function that relates to inflammatory processes with a turnover of matrix and alterations of tissue architecture. Changes in proliferation as well as motility were assessed in scratch-wound assays, in which the cell monolayer is ‘injured'. Closure of this scratch was significantly and dose-dependently inhibited by the addition of monoclonal YB-1 antibody (supplementary Fig 3C online) compared with isotype-matched control antibody, showing that wound closure was dependent on YB-1.

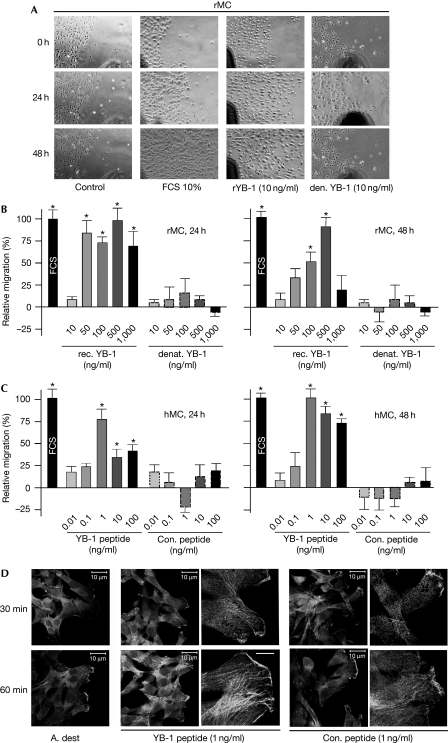

In a reciprocal approach, mesangial cells were grown to confluency and a scratch was introduced using a rubber policeman. Mesangial cell migration was monitored by light microscopy for 48 h under non-stimulated conditions and after the addition of rYB-1. Here, cell proliferation was blocked by the addition of mitomycin C before cell stimulation to monitor cell migration exclusively. rYB-1 markedly increased cell migration compared with the basal migration rate under unstimulated conditions, to a similar extent as observed with FCS (Fig 3A). This effect was absent when denatured rYB-1 protein was used, excluding the effects by LPS contaminants (Fig 3B). These results are reminiscent of the findings using HMGB1, which induces cell migration in a similar manner (Degryse et al, 2001). To address the question whether full-length YB-1 or the subdomains confer them the extracellular functions, oligopeptides (20 amino acids in length) corresponding to various YB-1 epitopes were tested in similar experiments. The biological activities of such short oligopeptides have been shown before using fragments of amino-acyl transfer RNA synthetases (Wakasugi & Schimmel, 1999). A peptide corresponding to epitopes in the cold-shock domain significantly induced cell migration in human mesangial cells (Fig 3C), whereas a control peptide had no effect. Furthermore, the YB-1 peptide induced cytoskeletal changes of human mesangial cell intracellular stress fibres. These findings are also in line with observations made using HMGB1, which can induce stress fibres in cells (Degryse et al, 2001).

Figure 3.

Extracellular YB-1 stimulates cell migration. (A) Rat mesangial cells grown to confluency and arrested by use of mitomycin C are assessed for cell migration under different conditions for 48 h. Increased migration in the scratched region is observed for cells stimulated with rYB-1 and FCS (10%, positive control), whereas denatured YB-1 has no effect. (B) Quantification was carried out at four regions of the migration front in three independent experiments. (C) Similarly, human mesangial cells (hMCs) show increased migration on stimulation with synthetic oligopeptides corresponding to a YB-1 cold-shock domain motif compared with unstimulated cells, whereas the control peptide does not have any influence. (D) These findings correlate to cytoskeletal changes in mesangial cells induced by YB-1 peptides, with a marked upregulation of actin stress fibres within 1 h, as detected by phalloidin staining. A. dest, Aqua dest; rMCs, rat mesangial cells; YB, Y-box protein.

In summary, extracellular YB-1 exerts a potent proliferative response in different cell types and promotes cell migration. Domains in the cold-shock protein probably mediate the effects, as synthetic peptides mimic such functions. This raises the question whether the observed protein fragments (compare supplementary Figs 1 and 2 online) are functionally active.

Given the striking similarities between YB-1 secretion and other non-classically secreted proteins of the nucleus (HMGB1 and heat-shock proteins), one might speculate that secretion of highly conserved nuclear proteins reflects an evolutionarily conserved mechanism to induce inflammation and cell activation.

Methods

Cell culture systems and YB-1 secretion assay. The mesangial cell YB-1 Tet-off system was established as described earlier (Dooley et al, 2006). Peripheral blood monocytic cells (PBMCs) were isolated by endotoxin-free Ficoll–Paque PLUS centrifugation (Amersham) from healthy blood-donor buffy coats. Adherent PBMCs cultured for 48 h were used for the secretion assays.

Mesangial and MM6 cells were seeded at 3 × 105 cells per well in six-well plates and the complete medium was replaced 12 h later with a serum-free RPMI medium supplemented with 10% lipumine (PAA Laboratories). Stimulation was carried out, and the conditioned medium was removed at the indicated time points. Cells and debris were pelleted by centrifugation at 300g for 5 min at 37°C. PBMC stimulation was carried out in RPMI medium containing 0.5% FCS.

TCA precipitation and microvesicle preparation. Proteins were precipitated by addition of TCA, (10% v/v, Sigma). Proteins were precipitated by centrifugation at 20,000g for 45 min at 4°C, washed twice with ice-cold 70% ethanol, air-dried and resuspended in 25 μl distilled water.

Microvesicles were enriched by sequential centrifugation steps, as depicted in supplementary Fig 2A online. Filters with 0.2 μm pore size (Nalgene) were used, followed by centrifugation at 100,000g. The resultant pellet (P2) was analysed for YB-1 content. For the protease protection assay, the P2 fraction was resolved in 100 μl PBS, 100 μl PBS-CM with 0.1 mg per 100 ml trypsin or 100 μl PBS-CM with 0.1 mg per 100 ml trypsin and 0.1% Triton X-100, and was incubated for 60 min.

Cell migration assay. The proliferative capacity of confluently grown mesangial cells was blocked by mitomycin C (10 μg/ml, Sigma). A scratch was introduced on the cell layer and the migratory front was assessed at four locations by using light microscopy for 48 h. Cells were incubated with full-length native and denatured rYB-1 at the indicated concentrations for peptides (see supplementary information online) or 10% FCS as positive control. Supplementary information is available at EMBO reports online (http://www.emboreports.org).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Movie 1

supplementary Movie 2

supplementary Materials and Methods

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the expert technical assistance provided by M. Wolf, B. Lennartz, H. Lue and Y. Marquardt. This work was funded by SFB 542 projects A11, C4, C12 (P.R.M.), A7 (J.B.) and C11 (J.M.B.) and DO373/8-1 of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, as well as the ‘START- and Rotations-Program' (Faculty of Medicine, Rheinisch–Westfälische Technische Hochschule, Aachen).

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Andrei C, Dazzi C, Lotti L, Torrisi MR, Chimini G, Rubartelli A (1999) The secretory route of the leaderless protein interleukin 1beta involves exocytosis of endolysosome-related vesicles. Mol Biol Cell 10: 1463–1475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi ME, Manfredi AA (2007) High-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) protein at the crossroads between innate and adaptive immunity. Immunol Rev 220: 35–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonaldi T, Talamo F, Scaffidi P, Ferrera D, Porto A, Bachi A, Rubartelli A, Agresti A, Bianchi ME (2003) Monocytic cells hyperacetylate chromatin protein HMGB1 to redirect it towards secretion. EMBO J 22: 5551–5560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degryse B, Bonaldi T, Scaffidi P, Muller S, Resnati M, Sanvito F, Arrigoni G, Bianchi ME (2001) The high mobility group (HMG) boxes of the nuclear protein HMG1 induce chemotaxis and cytoskeleton reorganization in rat smooth muscle cells. J Cell Biol 152: 1197–1206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooley S, Said HM, Gressner AM, Floege J, En-Nia A, Mertens PR (2006) Y-box protein-1 is the crucial mediator of antifibrotic interferon-gamma effects. J Biol Chem 281: 1784–1795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- En-Nia A, Yilmaz E, Klinge U, Lovett DH, Stefanidis I, Mertens PR (2005) Transcription factor YB-1 mediates DNA polymerase alpha gene expression. J Biol Chem 280: 7702–7711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evdokimova V, Ruzanov P, Anglesio MS, Sorokin AV, Ovchinnikov LP, Buckley J, Triche TJ, Sonenberg N, Sorensen PH (2006) Akt-mediated YB-1 phosphorylation activates translation of silent mRNA species. Mol Cell Biol 26: 277–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flieger O, Engling A, Bucala R, Lue H, Nickel W, Bernhagen J (2003) Regulated secretion of macrophage migration inhibitory factor is mediated by a non-classical pathway involving an ABC transporter. FEBS Lett 551: 78–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardella S, Andrei C, Ferrera D, Lotti LV, Torrisi MR, Bianchi ME, Rubartelli A (2002) The nuclear protein HMGB1 is secreted by monocytes via a non-classical, vesicle-mediated secretory pathway. EMBO Rep 3: 995–1001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki Y et al. (2005) Cell type-specific intervention of transforming growth factor beta/Smad signaling suppresses collagen gene expression and hepatic fibrosis in mice. Gastroenterology 129: 259–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleemann R et al. (2000) Intracellular action of the cytokine MIF to modulate AP-1 activity and the cell cycle through Jab1. Nature 408: 211–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohno K, Izumi H, Uchiumi T, Ashizuka M, Kuwano M (2003) The pleiotropic functions of the Y-box-binding protein, YB-1. Bioessays 25: 691–698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunter U, Floege J, von Jurgensonn AS, Stojanovic T, Merkel S, Grone HJ, Ferran C (2003) Expression of A20 in the vessel wall of rat-kidney allografts correlates with protection from transplant arteriosclerosis. Transplantation 75: 3–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mené P, Simonson MS, Dunn MJ (1989) Physiology of the mesangial cell. Physiol Rev 69: 1347–1424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickel W (2003) The mystery of nonclassical protein secretion. A current view on cargo proteins and potential export routes. Eur J Biochem 270: 2109–2119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffetseder U, Frye B, Rauen T, Jurchott K, Royer HD, Jansen PL, Mertens PR (2003) Splicing factor SRp30c interaction with Y-box protein-1 confers nuclear YB-1 shuttling and alternative splice site selection. J Biol Chem 278: 18241–18248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubartelli A, Cozzolino F, Talio M, Sitia R (1990) A novel secretory pathway for interleukin-1 beta, a protein lacking a signal sequence. EMBO J 9: 1503–1510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Roeyen CR, Eitner F, Martinkus S, Thieltges SR, Ostendorf T, Bokemeyer D, Luscher B, Luscher-Firzlaff JM, Floege J, Mertens PR (2005) Y-box protein 1 mediates PDGF-B effects in mesangioproliferative glomerular disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 2985–2996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakasugi K, Schimmel P (1999) Two distinct cytokines released from a human aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase. Science 284: 147–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Movie 1

supplementary Movie 2

supplementary Materials and Methods