Abstract

Formin proteins, characterized by the presence of conserved formin homology (FH) domains, play important roles in cytoskeletal regulation via their abilities to nucleate actin filament formation and to interact with multiple other proteins involved in cytoskeletal regulation. The C-terminal FH2 domain of formins is key for actin filament interactions and has been implicated in playing a role in interactions with microtubules. Inverted formin 1 (INF1) is unusual among the formin family in having the conserved FH1 and FH2 domains in its N-terminal half, with its C-terminal half being composed of a unique polypeptide sequence. In this study, we have examined a potential role for INF1 in regulating microtubule structure. INF1 associates discretely with microtubules, and this association is dependent on a novel C-terminal microtubule-binding domain. INF1 expressed in fibroblast cells induced actin stress fiber formation, coalignment of microtubules with actin filaments, and the formation of bundled, acetylated microtubules. Endogenous INF1 showed an association with acetylated microtubules, and knockdown of INF1 resulted in decreased levels of acetylated microtubules. Our data suggests a role for INF1 in microtubule modification and potentially in coordinating microtubule and F-actin structure.

INTRODUCTION

Formins are a family of effector proteins that commonly act downstream of small Rho GTPase activation (reviewed in Faix and Grosse, 2006; Goode and Eck, 2007). They have been primarily associated with regulating actin filament formation, and do so within various structures of most cell types in eukaryotic organisms. The formin homology 1 and 2 (FH1 and FH2) domains are largely responsible for the regulation of actin filament nucleation and elongation by formins. The FH1 domain associates with the monomeric actin-binding protein, profilin, and the FH2 domain associates with nascent or mature actin filaments. Dimers of FH2 domains can nucleate actin filaments, aid in the addition of actin to the growing ends of filaments, protect the ends of actin filaments from associating with capping proteins, sever actin filaments, or cause actin filament depolymerization (Goode and Eck, 2007). The FH2 domain also regulates the expression of cytoskeletal proteins through the activation of MAL (MKL1/myocardin-related transcription factor A), which translocates to the nucleus to activate serum response factor (SRF; Sotiropoulos et al., 1999; Copeland and Treisman, 2002; Miralles et al., 2003; Copeland et al., 2004). Formin activation of MAL is dependent on actin monomer depletion caused by the FH2 domain. The subsequent SRF activation is an additional mechanism by which stress fiber formation can be stimulated by formins (Schratt et al., 2002 and Morita et al., 2007).

Along with actin filament regulation, various studies have suggested that formins can directly regulate microtubule organization and stability (Palazzo et al., 2001; Wen et al., 2004; Rosales-Nieves et al., 2006; Bartolini et al., 2008). The FH2 domain of the Drosophila formin Cappuccino has been demonstrated to interact directly with microtubules in vitro (Rosales-Nieves et al., 2006), with similar results being recently reported for the FH1/FH2 region of mDia2 (Bartolini et al., 2008). If generalized to other formin proteins, this would make the FH2 domain unique in being a single domain able to interact directly with two different types of cytoskeletal filaments.

Outside of the characteristic FH1/FH2 region, formin proteins can vary considerably (Higgs, 2005). Although several contain a diaphanous-related region of homology (FH3 domain) and a GTPase-binding domain in the N-terminal end, domains such as PDZ and WH2 are unique to particular formins (Miyagi et al., 2002; Chhabra and Higgs, 2006). These confer distinct localizations and functions upon these formins. For instance, the PDZ domain of delphilin mediates an interaction with a membrane protein, the glutamate receptor δ2, in neurons (Miyagi et al., 2002). This may provide a link between a postsynaptic density complex and the actin cytoskeleton. In mDia1, a dimerization motif/coiled coil region in its N-terminal half, confers membrane localization on the protein (Seth et al., 2006; Copeland et al., 2007). Although formin family members have been demonstrated to be essential regulators of cytoskeletal structure (Peng et al., 2007; Sakata et al., 2007; Ji et al., 2008), little is known about the diversity of functions performed by the individual family members.

In this study, we have assessed the potential function of a uniquely structured formin, INF1 (inverted formin 1; also known as FHDC1). INF1, originally identified in part from a brain cDNA library (Nagase et al., 2000), contains FH1 and FH2 domains that define it as a member of the formin family (Katoh and Katoh, 2004; Higgs and Peterson, 2005). Unlike other formins, however, the FH1 and FH2 domains of INF1 are at the N-terminus, whereas the C-terminal end consists of a unique polypeptide sequence. INF1 does not possess any other obvious region of homology with any other protein and lacks conserved regulatory domains. The high degree of conservation of several motifs within the C-terminal sequence of INF1 orthologues suggests that it may contain novel regulatory or functional domains. We have analyzed the expression and localization of INF1 protein in various cell lines and mouse tissues. We focus on a possible role for INF1 in regulating the structuring of microtubules. Our results demonstrate that INF1 is unique in being a primarily microtubule-associated formin, and may be involved in regulating structures where microtubule organization plays a prominent role.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Analysis of INF1 Evolutionary Relationships

The FH2 domains of INF1, INF2, nematode inft-1, and invertebrate FH2 sequences that were found to be most similar to the FH2 domains of INF1 and INF2 were compared with the FH2 domains of several other animal formins. The invertebrate formin proteins similar to INF1 and INF2 (named INFX in this study) were initially retrieved from GenBank using TBLASTN (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/Blast.cgi) with either the INF1 zebrafish or INF2 pufferfish sequence. The same invertebrate sequences were found when searching with either the INF1 or INF2 sequence. Specific sequences used are listed in Figure 1. The FH2 regions used from each formin were determined with SMART analysis (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/). A phylogenetic comparison was performed with ClustalX 2.0 run locally. We used a bootstrap analysis with 1000 replicates after initial alignment of the sequences. An unrooted tree based on this analysis was generated with NJplot, and redrawn in Adobe Illustrator (San Jose, CA). The overall domain structure of these proteins was then compared using SMART analysis.

Figure 1.

INF proteins in animals. (A) An unrooted phylogenetic tree based on a comparison of the FH2 domains of INF1, INF2, and other animal formins. Sequences used for this analysis (with GenBank accession numbers in brackets) came from human (H. sapiens) INF1 (NP_203751.2) and INF2 (NP_071934.3); monkey (M. mulatta) INF1 (XP_001085372.1); mouse (M. musculus) INF1 (NP_001028473.1), INF2 (ABI20145.1), mDia1 (O08808.1), mDia3 (AAH86779.1), DAAM1 (AAH76585.1), delphilin (NP_579933.1), and FHOD1 (NP_808367.1); rat (R. norvegicus) INF1 (NP_001099907.1); platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus) INF1 (XP_001511976.1); toad (X. tropicalis or X. laevis) INF1 (CR942785.2), INF2 (NP_001072591.1), and FHOD1 (AAH84291.1); zebrafish (D. rerio) INF1 (predicted from BAC clone CH211-62K15), DAAM1 (XP_707353.2), and delphilin (XP_689509.2); pufferfish (Tetraodon nigroviridis) INF2 (CAG10691.1); sea squirt (Ciona intestinalis) INF1 (translated from AK173884.1); fruit fly (D. melanogaster or D. pseudoobscura) INFX (XP_001353341.1), diaphanous (NP_476981.1), DAAM (AAF45601.2), cappuccino (NP_722951.1), and FHOD (NP_729410.1); sea urchin (S. purpuratus) INFX (XP_793426.2 and XP_785094.2); wasp (Nasonia vitripennis) INFX (XP_001600053.1); honey bee (A. mellifera) INFX (translated from XR_015075.1); flour beetle (Tribolium castaneum). INFX (XP_970252.1); mosquito (A. aegypti) INFX (XP_001660600.1); and nematode worm (C. elegans and C. briggsae) inft-1 (NP_497334.1 and XP_001666551.1, respectively). The novel INFX group contains FH2 domains most similar to both INF1 and INF2, as determined by both BLAST and ClustalW2 analysis. Branch lengths correspond to evolutionary distances. (B) Domain structures of representative animal formins. Delphilin, DAAM1, and diaphanous, as with most known formins, contain C-terminal FH1/FH2 regions. These formins also contain regulatory domains in the N-terminal half. Shown are the PDZ domain of delphilin, and the GTPase-binding domain (GBD) and diaphanous-related formin domain (DRF; diaphanous inhibitory domain region) of DAAM1 and diaphanous. INF2 and INFX proteins share the DRF domain in the N-terminal part of the protein. Each of the INF proteins has a C-terminal region downstream from the FH2 domain that is more extensive than in other formins. In INF1, and in the nematode worm inft-1 sequences, the region upstream from the FH1 domains is considerably shorter relative to other formins, thus placing the FH1/FH2 region in the N-terminal half. There are no obvious regulatory regions upstream of the INF1 FH1 region in the N-terminus. At the C-terminal end of INF1, we have mapped a novel microtubule-binding domain (MTBD), in this study. (C) A ClustalW2 alignment of part of the novel C-terminal MTBD of INF1 showing two well conserved regions, which we have labeled as MTB1 and MTB2. Asterisks denote identical amino acid residues in each sequence, two dots denote conserved amino acids, and one dot denotes semiconserved amino acids.

Plasmid Constructs

INF1 expression plasmids were generated using the pEYFPN1, pEGFPC3 (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA), pGex6p2 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ), and EFplink vectors with either myc or Flag epitope tags (Sotiropoulos et al., 1999). The full-length human INF1 open reading frame was generated using DNA from the KIAA1727 cDNA clone (obtained from the Kazusa DNA Research Institute), with missing 5′ sequence being added on using oligonucleotides encoding amino acids 1-25. C-terminal truncated INF1 fusions were made in pEYFP by removing sequence coding for the region downstream from amino acid 1055 (INF1ΔC1-YFP) or amino acid 959 (INF1ΔC2-YFP) using internal BglII or SacII sites, respectively. The INF1 C-terminal fusion, GFP-INF1C (codons 958-1143), was made by removing a SacII fragment from the full-length INF1FL-YFP plasmid to insert into the pEGFPC3 vector. This same SacII fragment was also used to generate a GST-INF1C fusion in pGex6p2. GFP-ΔMTB1 and GFP-ΔMTB2 plasmids were generated by removing codons 958-1001 or 1033-1042, respectively. Myc-NT plasmid encoded amino acids 1-485, myc-FH2 encoded amino acids 85-485, and myc-CT encoded amino acids 486-1143. Codon numbering is given for the human INF1 protein in GenBank accession number NP_203751. For mouse INF1, the full open reading frame was cloned using overlapping fragments generated with RT-PCR, shown in Supplemental Figure S1. The full insert was cloned as a BglII-SalI insert into pEGFPC1 (GFP-mINF1) using standard cloning techniques. Constructs used for SRF activation assays, 3DA.Luc and MLV-LacZ, have been described previously (Geneste et al., 2002 and Sotiropoulos et al., 1999, respectively). The inserts of all newly generated plasmids were sequenced to ensure their accuracy, and appropriate expression of the fusion proteins was confirmed by immunoblotting.

Cell Culture and Animals

The Cos-1 monkey kidney cell line, N2A mouse neuroblastoma cells, F11 rat/mouse sensory neuron cell line, H9C2 rat cardiomyocyte line, and HeLa human carcinoma line were each maintained in DMEM containing 10% FBS and 1% pen/strep in a 37°C incubator with 5% CO2. Subconfluent cells were passaged in 10-cm plastic dishes. For differentiation of the N2A cells, serum containing DMEM was replaced with DMEM containing 0.5 mM dibutyryl cAMP (Calbiochem, Mississauga, ON, Canada) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin for 24–48 h. Mouse NIH 3T3 fibroblast cells were maintained in DMEM containing 10% FBS and 1% pen/strep in a 37°C incubator with 10% CO2. Subconfluent cells were passaged in 10-cm plastic dishes for up to 13 passages.

Cos-1 cells were transfected with PEI (polyethyleneimine; Polysciences, Warrington, PA). This was done by mixing 5 μl of a 1 μg/μL PEI solution with 1.5 μg of plasmid DNA in 50 μl of OptiMEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 15–30 min. This was then added to one well of cells in a six-well plate in 1 ml of OptiMEM. After a 5- to 8-h incubation, the transfection medium was replaced with normal growth medium. NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with either PEI, or in the case of the SRF activation assays, Lipofectamine (Invitrogen). Drug treatments with nocodazole (Sigma, Oakville, Ontario, Canada) or latrunculin A (Sigma) were performed as indicated in Results. Both nocodazole and latrunculin A stock solutions were prepared in DMSO (Sigma); DMSO alone was used for control samples. For microscopy, all cells were plated on sterile glass coverslips.

Mouse tissues were collected from 5-d-old and 2-mo-old C57BL/6 mice. Tissues use for immunohistology were immersed in OCT compound (Sakura, Tokyo, Japan) in plastic molds, frozen using liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Frozen sections were cut in a cryostat at an 8-μm thickness and placed on gelatin-coated Superfrost Plus slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). The sections were air-dried and either stained immediately or stored at −20°C. Tissue used for immunoblotting were collected in lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA, and 1% Triton X-100. The protein content was determined by Bradford analysis, and samples were diluted in a standard SDS buffer for SDS-PAGE analysis.

INF1 Antibody Generation

INF1 antibody was generated against a protein corresponding to the human INF1 FH2 domain (amino acids 85–541). Briefly, protein expressed in BL21 bacteria was purified by PreScission Protease (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) cleavage of GST-INF1 FH2 protein bound to glutathione Sepharose 4B beads. The purified FH2 protein was dialyzed against phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and used for injection into New Zealand White rabbits (Cedarlane Laboratories, Burlington, ON, Canada). Antibody from the immune serum was affinity-purified against protein A, followed by purification against GST-INF1 FH2, using standard techniques. Antibody was eluted with a glycine buffer (pH 2.8) and then buffered with pH 9.0 Tris before dialysis into PBS.

Immunoblotting

Protein lysates were collected from cells grown in culture by two methods. Initially, equal numbers of cells were washed twice in PBS, scraped in Laemmli buffer, and boiled for 5 min before cooling on ice. As a second method, cells were washed twice in PBS and then scraped in a high salt lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 4% SDS, 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA) supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Indianapolis, IN), and dithiothreitol (5 mM) was added directly before use. These samples were immediately boiled for 5 min and then cooled in room temperature water for 1 min, before adding 50 μl of 300 mM iodoacetamide per 500 μl of sample. The samples were centrifuged and sheared through a 27-gauge needle. To load these samples on a gel, they were added to an equal volume of gel-loading buffer containing 100 mM Tris, pH 6.8, 4% SDS, 20% glycerol, 5% β-mercaptoethanol, 1 M NaCl, 4 M urea, and 0.1% bromophenol blue. Lysates were run on standard SDS-PAGE gels and transferred onto PVDF membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA). The blots were blocked with 5% nonfat dairy milk (NFDM) in Tris-buffered saline (TBS). Primary and secondary antibody incubations were performed in TBS containing 0.5% Tween 20 (TBST). All washings were performed using TBST. HRP-labeled secondary antibodies were detected with chemiluminescence reagent (Perkin Elmer-Cetus, Boston, MA) before blots being exposed to autoradiography film. Affinity-purified anti-INF1 antibody was incubated at 1:500 overnight at 4°C, anti-α-tubulin antibody was incubated at 1:5000 and anti-lamin B at 1:200 at room temperature for 1 h.

INF1 Small Interfering RNA

INF1 was knocked down in NIH 3T3 cells using an RNA oligonucleotide duplex (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA) with the following sequences: 5′-GCUAUAGCACCAAAGAGAAAUUCCT-3′ and 5′-AGGAAUUUCUCUUUGGUGCUAUAGCAU-3′. This duplex was found to reliably reduce GFP-mINF1 levels when cotransfected in Cos-1 cells (Supplemental Figure S2). NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with the small interfering RNA (siRNA) duplex using Dharmafect 1 (Dharmacon Research, Boulder, CO) following the manufacturer's instructions. We examined INF1 levels in cell lysates collected at 2, 3, 5, 7, and 10 d after transfection by immunoblotting. Lysates were collected in high-salt lysis buffer as described above. Antibodies to detect acetylated tubulin (Sigma), α-tubulin (Sigma), and lamin B (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) were used to probe the blots following stripping in a pH 2.5 glycine (0.1 M) and 0.5% SDS buffer between each probing.

Serum Response Factor Activation Assay

SRF activation assays were performed as described previously (Copeland et al., 2002). Briefly, NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with 50 ng of the reporter construct 3DA.Luc, along with 250 ng of the reference plasmid, MLV-LacZ, and the expression plasmid encoding the fusion protein to be tested. Empty pEF Flag was cotransfected to a total of 1.5 μg of DNA per well in six-well plates. After the transfection, cells were maintained in 0.5% FBS in DMEM with 1% penicillin/streptomycin. After 24 h, cells were harvested for a standard luciferase assay. Transfection efficiency was standardized by a β-galactosidase assay. Data are shown relative to reporter activation by the constitutively active SRF derivative, SRFVP16 (50 ng).

In Vitro Microtubule Association and Bundling Assays

GST-INF1C fusion protein was purified from BL21 bacteria induced with 0.2 mM IPTG at 37°C. Purified protein incubated on glutathione Sepharose 4B beads (GE Healthcare) was recovered by PreScission Protease (GE Healthcare) cleavage of the glutathione S-transferase (GST) moiety, followed by dialysis into PEM buffer (20 mM PIPES, pH 7, 20 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, and 5% glycerol). Microtubule spin-down assays were performed using a microtubule spin-down kit (Cytoskeleton, Denver, CO). Microtubules were assembled for 20 min at 35°C in a general tubulin buffer (80 mM PIPES, pH 7.0, 2 mM MgCl2, and 0.5 mM EGTA) in the presence of GTP and taxol. INF1C or control protein was incubated with 0.83 μM tubulin dimers for 30 min. Microtubules and associated proteins were then pelleted at 100,000 × g through a 50% glycerol cushion buffer. Supernatant and pellet were combined with Laemmli loading buffer, and equal amounts of sample were run on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel for analysis by Coomassie blue staining.

To examine microtubule bundling by immunofluorescence, INF1C or control protein was incubated with stabilized microtubules at room temperature for 30 min. Samples were then placed on gelatin-coated Superfrost Plus slides (Fisher) and incubated for 10 min before fixing with 4% paraformaldehyde. Microtubules were visualized with anti-α-tubulin antibody and an Alexa Fluor 594–labeled secondary antibody (Invitrogen). The preparations were photographed on an AxioImager microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) with a 63× Plan Apochromat objective.

Immunofluorescence

Tissue culture cells and mouse brain sections were stained using a basic immunofluorescence protocol. Briefly, cells or tissue sections were washed twice in PBS and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min. The cells or tissue sections were washed three times for 5 min in PBS and permeabilized and blocked with PBS containing 0.4% Triton X-100 and 10% FBS. Primary antibody diluted in PBS containing 0.04% Triton X-100, and 5% FBS was then incubated on the samples either overnight at 4°C or for 1 h at room temperature. The samples were washed three times for 5 min and then incubated for 1 h at room temperature with the appropriate secondary antibody. After a final wash of three times for 5 min in PBS, the samples were mounted using Vectashield with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Primary antibodies used included affinity-purified anti-INF1 polyclonal at 1:50, anti-α-tubulin monoclonal at 1:1000, anti-acetylated tubulin monoclonal at 1:1000 (Sigma), anti-detryrosinated tubulin at 1:250 (Chemicon, Temecula, CA), and anti-βIII-tubulin (tuj1) at 1:1000 (Covance Laboratories, Madison, WI). Phalloidin-rhodamine or phalloidin-Alexa Fluor 488 (1:20; Invitrogen), incubated with the secondary antibody, were used to detect F-actin.

Cells and tissues were imaged primarily with a Zeiss AxioImager equipped with an apotome. Apotome optical sections were imaged with a 63× Plan Apochromat objective producing 0.7-μm sections. Confocal imaging was done with a LSM 5 Pascal confocal system attached to an Axiovert 200M inverted microscope (Zeiss). Confocal sections of 1 μm were produced using a 63× Plan Apochromat objective with 488- and 543-nm laser lines being used for excitation. A bandpass 505–530-nm emission filter was used to collect the green emission and exclude nonspecific emission from the red fluorophore, and a long-pass 560 filter was used for the red emission.

RESULTS

INF1 Is a Unique Microtubule-associated Formin That Affects F-Actin Organization

To understand the origin of the unique INF1 domain structure, we analyzed the phylogenetic relationship between INF1 and other animal formins. The INF1 and INF2 proteins diverged in the early chordates from an ancestral form containing both a diaphanous-related region upstream from the FH1 and FH2 domains, and an extensive C-terminal end downstream. Related sequences for previously undescribed Animalia formins with this type of structure are found in various insect species, as well as the sea urchin, Strongylocentrotus purpuratus (Figure 1). We have named these the INFX proteins. These proteins resemble the INF2 protein (Higgs and Peterson, 2005), but have longer C-terminal regions downstream from the FH2 domain. The INFX FH2 domains are intermediate to INF1 and INF2 in their primary sequences. Regions coding for N-terminal diaphanous-related formin domains are absent 5′ to the FH1/FH2 coding region in the INF1 gene from human, mouse, and zebrafish (as assessed with MIT Genscan). Sequences resembling the diaphanous autoregulatory domain (DAD) and diaphanous inhibitory domain (DID) do not appear to be present in INF1. INF1 does contain several regions within its C-terminal end that are conserved between vertebrate orthologues (Katoh and Katoh, 2004), including regions we have labeled as MTB1 and MTB2 (Figure 1C). INF1 is therefore likely to be regulated in a manner fundamentally different from the better-characterized diaphanous-related formins and may contain novel functions conferred on it by its unique C-terminal end.

To examine if INF1 exhibited functions characteristic of other formins, we assessed whether expression of INF1 fusion proteins could induce the formation of stress fibers and induce SRF activation in serum-starved NIH 3T3 fibroblasts. Transfection of cells with plasmids encoding full-length and N-terminal INF1 fusion proteins could induce the formation of stress fibers in the 3T3 cells after 1 d of expression (Figure 2 and Supplemental Figure S3). Induction of stress fiber formation by full-length INF1 was similar to that of the isolated FH2 domain from mDia1 (Figure 1E). The N-terminal fusion proteins of INF1 were, however, less efficient at inducing thick stress fiber formation, producing mainly an increase in thin filaments. Interestingly, the full-length INF1 localized discretely with microtubules (insets in Figure 2, A and C).

Figure 2.

INF1 induces stress fiber formation and SRF activation in NIH 3T3 cells. (A–D) Full-length myc-INF1FL fusion protein induced the formation of actin filaments (B) in serum-starved 3T3 cells after 1 d of expression. (C) Microtubule staining in the transfected cells coaligned with the INF1 fusion protein. Coaligning INF1 and microtubules are indicated by arrows in the insets, which are enlarged from the boxed area of the transfected cell shown. Actin filaments also coaligned to a more limited extent (indicated by the arrow in the inset in B). The merged image is shown in D. (E) Schematics of the myc-INF1FL fusion protein, myc-INF1 truncation mutants, and myc-mDia1 full-length (FL) and FH2 domain fusion proteins used to examine stress fiber formation, along with quantifications of starved 3T3 cells expressing these proteins that displayed increased actin filament formation. Cells were scored as having an increase in thick filaments if the filaments displayed markedly brighter phalloidin labeling compared with untransfected cells (as in B) and as having an increase in thin filaments if there were more actin filaments compared with the untransfected cells, but with a similar intensity of phalloidin labeling. (F) Full-length (myc-INF1FL) and N-terminal (myc-Nterm and myc-FH2) INF1 fusion proteins induced SRF activation after 1 d of expression in serum-starved 3T3 cells. Plasmid, at 0.1, 0.3, and 1 μg, was transfected for each INF1 plasmid. Empty vector (EV) served as a negative control. Expression of a C-terminal INF1 fusion (myc-Cterm) did not induce SRF activation. Results are from three independent experiments, with SE of the mean shown. Scale bar, 20 μm in A and also the larger images in B–D.

Full-length and N-terminal INF1 fusion proteins also induced SRF activation in serum-starved NIH 3T3 cells (Figure 2F). Expression of the FH2 domain alone (myc-FH2) was sufficient to induce activation of the SRF reporter gene, consistent with our previous results obtained with mDia1 (Copeland et al., 2002). Also similar to mDia1, expression of protein with both the FH1 and FH2 domains (myc-Nterm and myc-INF1FL) induced an increased response in the SRF activation assay. Expression of the C-terminal end of INF1 had no effect on SRF activation. Of note is that the full-length INF1 fusion protein was constitutively active in the SRF and stress fiber formation assays. This is consistent with INF1 activity being regulated differently than the diaphanous-related formins.

Endogenous INF1 Is Predominantly Microtubule-associated

To examine expression of the INF1 protein, we produced affinity-purified polyclonal antibody against the human INF1 FH2 domain. This antibody recognized both mouse and human INF1 fusion proteins (Figure 3). By immunofluorescence, the INF1 antibody specifically recognized full-length INF1FL-YFP fusion protein expressed in Cos-1 cells (Figure 3A). Untransfected Cos-1 cells did not display any staining. By immunoblot analysis of NIH 3T3 lysates, we observed a prominent band of ∼125 kDa, which could be knocked down by transfecting cells with an siRNA duplex targeted to the INF1 transcript (Figure 3B). Unexpectedly, full-length INF1 fusion proteins ran appreciably higher than the 125-kDa mark on standard SDS-PAGE gels (Figure 3C). We were able to observe a band corresponding to the size of full-length INF1 fusion protein, present in several cell lines analyzed, though only with the use of cell lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors with a high salt concentration (see Materials and Methods), and longer exposures of the blots. Detection of this second band, as well as the other bands recognized by the antibody, was greatly reduced by preincubating the INF1 antibody with purified GST-INF1 (data not shown). These data suggest that the predominant lower molecular weight band may be due to protein modification of the endogenous INF1. Alternatively, rapid protein degradation or modification upon cell lysis may occur. No evidence of alternative splicing for mouse INF1 was found by RT-PCR analysis (Supplemental Figure S1).

Figure 3.

Endogenous INF1 protein is primarily associated with microtubules. (A) Full-length INF1FL-YFP expressed in Cos-1 cells was specifically detected using an affinity-purified INF1 pAb by immunofluorescence. Staining was not observed in untransfected cells. (B) Detection of endogenous INF1 by immunoblotting NIH 3T3 cell lysates. A band of ∼125 kDa was consistently the predominant band detected. Detection of this band was decreased by an average of 51% (three separate trials) using 1 nM INF1 siRNA duplex when compared with cells transfected with 1 nM control scrambled siRNA, in lysates collected 7 d after transfection. Mock-transfected cells displayed levels of INF1 similar to that of the control transfected cells. Lamin B is shown as a loading control. Lysates were collected with lysis buffer containing a high salt concentration and protease inhibitors, as described in Materials and Methods, though similar results were obtained with a standard SDS buffer in this case (data not shown). (C) Immunoblotting with INF1 pAb using protein lysates from Cos-1 cells expressing myc-INF1FL or GFP-mINF1, two neuronal cell lines (N2A and F11), NIH 3T3 fibroblast cells, a cardiomyoblast cell line (H9C2), and HeLa cells. Endogenous protein running at a molecular weight similar to myc-INF1 (∼160 kDa; marked with an arrow) was detected in undifferentiated and differentiated N2A cells (N2A and N2A diff, respectively), undifferentiated F11 cells, NIH 3T3 cells, and H9C2 cells, but not in HeLa or Cos-1 cells (note no band of this size in the GFP-mINF1 lane, with this fusion protein running higher because of the additional size of the GFP). In the N2A, F11, NIH 3T3, and H9C2 lysates, the lower molecular weight band of ∼125 kDa was detected much more prominently, and was overexposed in order to detect the higher molecular weight band. (D) INF1 localized in a filamentous pattern in NIH 3T3 cells. This pattern coaligned with a subset of microtubules (E). (F) F-actin staining was not consistently colocalized with the INF1 staining. (G) Merged image of D–G. The inset in G shows INF1 merged with microtubules alone from this cell, at a higher magnification. Scale bar, (F) 20 μm.

By immunofluorescence analysis of endogenous INF1 in NIH 3T3 cells, the INF1 antibody detected protein discretely coaligning with a subset of microtubules (Figure 3, D–G). Filamentous INF1 staining was present in a majority of cells, with some punctate staining also being commonly observed. Both punctate and filamentous INF1 staining was primarily microtubule-associated in all cells. The same was true in a second cell line with a fibroblast-like morphology, H9C2 cardiomyoblasts (Supplemental Figure S4). Because the INF1 FH2 domain may be involved in actin filament association and polymerization, we also investigated whether INF1 colocalized with F-actin staining. There was, however, no consistent pattern of INF1 localization with F-actin in NIH 3T3 (Figure 3) or H9C2 cells. Correspondingly, disruption of microtubule polymerization with nocodazole in NIH 3T3 cells resulted in the diffuse localization of the endogenous INF1 (Figure 4, E–H). The disruption of actin filament polymerization with latrunculin A had little effect on INF1 distribution (Figure 4, I–L). Endogenous INF1 is therefore a predominantly microtubule-associated protein in these cells.

Figure 4.

INF1 localization is microtubule-dependent in NIH 3T3 cells. (A–D) Control cells treated with a 1:500 DMSO dilution, stained for INF1 (A), microtubules (B), and F-actin (C). INF1 localized in a filamentous pattern along microtubules in these cells. The merged image is shown in D, with enlargement from the boxed area in the inset. (E–H) Cells treated with the microtubule depolymerizing drug nocodazole (500 nM, 15 min) had dispersed microtubules (F) and dispersed INF1 staining (E). F-actin staining is shown in G, and the merged image in H, with enlargement from the boxed area in the inset. (I–L) Cells treated with the actin depolymerizing drug latrunculin A (1 μm, 15 min) had dispersed actin filaments (K) but INF1 (I) remained localized along the microtubules (J). The merged image is shown in L, with enlargement from the boxed area in the inset. Scale bar, 20 μm and applies to all images.

INF1 Expression in Mouse

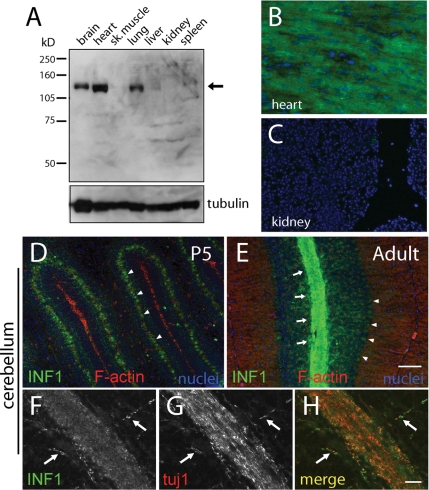

To gain some insight into the types of structures INF1 might normally associate with in animal tissues, we screened several mouse tissues for INF1 expression. By immunoblot analysis, we observed INF1 to be readily detectable in brain, heart, and lung tissues (Figure 5A). Correspondingly, INF1 was easily detected by immunofluorescence staining in ventricular muscle sections of the heart, but not in kidney sections (Figure 5, B and C). In the brain, we found INF1 to be most strongly expressed in Purkinje neurons of the cerebellum. In sections from 5-d-old animals, INF1 was predominantly found in the cell bodies of the immature Purkinje neurons (Figure 5D), which do not fully mature until the second week after birth (Millen et al., 1994). In the adult animal, INF1 staining was primarily found in the white matter of the cerebellum, with weak staining in projections from the Purkinje cell layer (Figure 5E). This staining appeared to be axonal and was localized in proximity to neuronal βIII-tubulin staining (Figure 5, F–H).

Figure 5.

Expression of INF1 in mouse tissues. (A) Immunoblot of mouse tissues showing expression of INF1 protein (arrow) in brain, heart, and lung. (B) By immunofluorescence analysis, INF1 was readily detectable in ventricular muscle of the heart. (C) At an identical exposure as in B, an immunofluorescence signal was barely detectable in kidney, corresponding to immunoblotting results shown in A. (D) INF1 (green) staining in a 5-d-old (P5) mouse cerebellum coronal section. The section was counterstained for F-actin (red) and chromatin (blue). INF1 staining in Purkinje neuron cell bodies is indicated by the arrowheads. (E) Sagittal brain section showing INF1 (green) staining with F-actin (red) labeling in the cerebellum of a 2-mo-old (adult) mouse. Arrows point to the white matter layer, and arrowheads to the Purkinje neuron cell bodies. (F–H) Higher magnification confocal images showing INF1 (F) with tuj1 (βIII-tubulin; G) in axons. The merged image is shown in E. Although INF1 was consistently associated with tuj1 staining, they did not necessarily colocalize. Scale bar, (D and E) 20 μm, (F–H) 10 μm.

The INF1 C-Terminus Contains a Microtubule-binding Domain and Is Required for INF1 Microtubule Association

To examine which domain of the INF1 protein might target INF1 to microtubules, we investigated whether the conserved regions in the C-terminal half may be necessary for proper localization. We initially examined the importance of the two conserved regions located toward the C-terminal end of the protein (labeled MTB1 and MTB2 in Figure 1). Full-length INF1FL-YFP fusion protein primarily coaligned with microtubules in Cos-1 cells (Figure 6, A–C). Transfection with a full-length mouse GFP-mINF1 construct additionally resulted in a noticeable bundling of the microtubules (Supplemental Figure S1). The INF1ΔC1-YFP fusion, which had sequence removed downstream of the MTB1 and MTB2 regions, also localized in a filamentous pattern along the length of the microtubules. This filamentous localization occurred in fewer than half of the cells compared with the full-length INF1 fusion protein, however, indicating a reduced ability to associate with microtubules (Figure 6, D–F). More cells expressing INF1ΔC1-YFP displayed puncta or diffusely localized fusion protein. The INF1ΔC2-YFP protein, which lacks the MTB1 and MTB2 regions, was primarily diffusely localized or localized in puncta (Figure 6, G–I). A C-terminal fusion protein containing MTB1 and MTB2, GFP-INF1C, localized discretely with bundled microtubules in Cos-1 cells (Figure 6, J–L). Prominent nuclear localization in most of the cells may have been an artifact of the high expression of this small fusion protein and was not observed with the full-length fusion protein. The failure of INF1ΔC2-YFP to associate with microtubules, as well as the association of GFP-INF1C with bundled microtubules, demonstrates that the C-terminal end of INF1 is both necessary and sufficient for the microtubule association of INF1.

Figure 6.

The C-terminus of INF1 is required for INF1 microtubule association. (A–C) Full-length INF1FL-YFP fusion protein expressed in Cos-1 cells. The fusion protein (A) primarily coaligned with microtubules (B) in 94% of the cells (n = 148 cells, two trials). The merged image is shown in C. Insets show an enlargement of the boxed region. (D–F) The truncated INF1ΔC1-YFP protein (D) was coaligned with microtubules in 38% of the cells expressing this fusion (n = 138 cells, two trials; E), though it was more commonly diffusely localized or was localized to puncta. The INF1ΔC2-YFP protein (G) was almost completely diffusely localized or localized to puncta and showed only a very limited association with microtubules (H). Microtubule coalignment was observed in just 2% of the INF1ΔC2-YFP–transfected cells (n = 169 cells, two trials). The merged image is shown in I. Insets, an enlarged image of the boxed region. (J–L) The C-terminal GFP-INF1C protein (J) localized with bundled microtubules (K) in the cytoplasm. This protein also localized to nuclei. The merged image is shown in L. Scale bar, 20 μm in L, and applies to all images.

To further define the regions in the C-terminal end of INF1 that are necessary for microtubule association, we generated fusion proteins lacking the conserved MTB1 (GFP-ΔMTB1) or MTB2 (GFP-ΔMTB2) regions. In Cos-1 cells, these proteins were diffusely localized, with limited microtubule association (Figure 7, C–F). Additionally, neither GFP-ΔMTB1 nor GFP-ΔMTB2 induced any microtubule bundling, whereas microtubule bundles were apparent in one-third of the Cos-1 cells expressing GFP-INF1C (Figure 7, A and B). Therefore, both the MTB1 and MTB2 regions play a role in the association of INF1 with microtubules.

Figure 7.

The INF1 C-terminus interacts with and bundles microtubules directly. Cos-1 cells transfected with GFP-INF1C showed the fusion protein (A) associated with bundled microtubules (B). Microtubule coalignment was observed in 62% of the transfected cells (n = 140 cells), with 33% of the cells displaying thicker, bundled microtubules. When the MTB1 region was removed (GFP-ΔMTB1), the fusion protein was primarily diffusely localized (C). Limited microtubule coalignment was observed in 15% of the GFP-ΔMTB1 transfected cells (n = 104 cells). Microtubules are shown in D. When the MTB2 region was removed (GFP-ΔMTB2), the fusion protein was again primarily diffusely localized (E). Limited microtubule coalignment was observed in 26% of the GFP-ΔMTB2 transfected cells (n = 98 cells). Microtubules are shown in F. (G) Purified INF1C protein was incubated with microtubules and centrifuged at 100,000 × g. The INF1C protein was found mostly in the pellet (P) fraction when incubated with microtubules, but remained in the supernatant (S) when incubated alone. GST incubated with or without microtubules remained in the supernatant. (H) Purified INF1C protein incubated with microtubules, but not GST (I), induced microtubule bundling, as observed by immunofluorescence microscopy. Scale bar, 20 μm in F and applies to all images of the cells.

To determine if the INF1 C-terminus is able to bind microtubules directly, we produced a GST-INF1C protein. The INF1 C-terminal end was purified by glutathione affinity chromatography and protease cleavage of the GST tag. The purified INF1C protein was then used in an in vitro microtubule spin-down assay and in a fluorescence-based microtubule-bundling assay. Proteins that are normally soluble will cosediment with the microtubules in the spin-down assay when centrifuged at 100,000 × g if they bind directly to the microtubules. In this assay, soluble INF1C incubated on its own remained in the supernatant after ultracentrifugation. In contrast, INF1C incubated with purified microtubules cosedimented with the microtubules and was found primarily in the pellet after the high-speed spin (Figure 7G). To assess the effect of INF1C on microtubule bundling, we incubated INF1C with purified microtubules that were then fixed and stained on microscope slides. Incubation with INF1, but not control GST protein, induced microtubule bundling in this assay (Figure 7, H and I). Thus, the INF1 C-terminus is able to bind and bundle microtubules directly.

INF1 Stabilizes Microtubules

The induction of bundled basket-like microtubules by INF1C is consistent with INF1 promoting microtubule stabilization. To test this, we treated Cos-1 cells with 1 or 10 μM nocodazole for 1 h. Treatment with 1 μM was sufficient to depolymerize most microtubules outside of the centrosomes and midbodies, whereas 10 μM nocodazole additionally caused centrosome and midbody depolymerization. Cells expressing the full-length INF1FL-YFP were able to retain an extensive microtubule network at 1 μM nocodazole as well as at the 10 μM concentration, albeit to a lesser extent (Figure 8, A, B, and G). Cells expressing the C-terminal GFP-INF1C protein also retained extensive microtubule networks, with the microtubules commonly retaining a bundled appearance (Figure 8, E and F). INF1ΔC2-YFP expressing cells contained primarily diffuse microtubule staining (Figure 8, C and D). A few cells expressing INF1ΔC2-YFP displayed a very limited number of microtubule filaments (Figure 8G), though at the 1 μM nocodazole concentration this was not significantly different from GFP expressing control cells (p = 0.34, two-tailed t test). There was, however, a marginally significant difference observed between INF1ΔC2-YFP and GFP expressing cells for the 10 μM concentration (p = 0.04).

Figure 8.

The INF1 C-terminus confers resistance against nocodazole-induced microtubule depolymerization. (A and B) Cos-1 cells expressing INF1FL-YFP were treated with 1 or 10 μM nocodazole for 1 h and then fixed and labeled with α-tubulin antibody. Cells expressing the full-length INF1 fusion still retained intact microtubules, though they were very limited at the 10 μM nocodazole concentration. Microtubules were scored as being extensive if there was more filamentous labeling than diffuse labeling within a cell and limited if the labeling was more diffuse than filamentous. (C and D) In cells expressing the C-terminal truncated INF1ΔC2-YFP fusion protein, very few cells had any filamentous tubulin labeling at either nocodazole concentration. In cells expressing the C-terminal fusion protein, GFP-INF1C, many cells were observed to have filamentous labeling, with this being primarily extensive at the lower nocodazole concentration and more limited at the higher concentration. (G) Quantification of the microtubule phenotypes from cells expressing INF1FL-YFP (n = 164 cells for 1 μM and 215 cells for 10 μM nocodazole), INF1ΔC2-YFP (n = 200 cells for 1 μM and 171 cells for 10 μM nocodazole), GFP-INF1C (n = 360 cells for 1 μM and 305 cells for 10 μM nocodazole), and GFP (n = 292 cells for 1 μM and 273 cells for 10 μM nocodazole) alone, observed from three separate trials. Error bars, SE of the mean. Scale bar, 20 μm in F and applies to all images.

INF1 Induces the Formation of Acetylated Microtubules

We next examined whether the expression of INF1 fusion proteins could be associated with the formation of acetylated microtubules, a marker for microtubule stabilization. We expressed INF1FL-YFP, INF1ΔC2-YFP, or GFP-INF1C in confluent NIH 3T3 cells. The confluent NIH 3T3 cells contained weak acetylated microtubule labeling, with strong labeling limited to the spindles of dividing cells and midbodies. As expected, expression of GFP-INF1C induced the robust formation of bundled, acetylated microtubules (Figure 9, E and F). The INF1FL-YFP protein also induced acetylated microtubule formation, though to a lesser extent than the isolated C-terminus (Figure 9, A and B). Surprisingly, expression of the INF1ΔC2-YFP protein, which did not obviously associate with microtubules, also induced the accumulation of acetylated microtubules in approximately one-third of cells (Figure 9, C and D). Unlike the full-length and C-terminal fusions, however, the INF1ΔC2-YFP did not necessarily colocalize with the acetylated microtubules. Transfection of a control GFP plasmid did not cause any increase in acetylated microtubule staining in the expressing cells. Thus the effect is specific to expression of INF1. The FH2 domain of other formins has been implicated in microtubule interactions (Ishizaki et al., 2001; Rosales-Nieves et al., 2006; Bartolini et al., 2008). Therefore, we tested the ability of the INF1 FH2 domain to induce formation of acetylated microtubules. Expression of a Flag-tagged derivative of the INF1 FH2 domain failed to induce the accumulation of acetylated microtubules (Figure 7, G and H).

Figure 9.

INF1 induces acetylated microtubule formation. Expression of INF1FL-YFP (B) in NIH 3T3 cells for 1 d induced an increase in labeling for acetylated microtubules (A) in 44% of the cells. Cells were counted as having increased labeling only when they showed a clearly stronger signal relative to all untransfected cells in the same field. (C) Acetylated microtubule formation was also induced in 28% of the cells expressing the INF1ΔC2-YFP fusion protein (D). Highly bundled acetylated microtubules (E) formed with the expression of the GFP-INF1C fusion protein (F) in 69% of the transfected cells. Expression of a Flag-FH2 protein (H) did not result in increased acetylated microtubule staining (G). Fusion protein expressing cells are marked with an asterisk in A, C, E, and G. The numbers of cells expressing each of these fusion proteins that displayed increased acetylated microtubule staining relative to the surrounding untransfected cells is quantified in I, along with data from cells transfected with GFP alone. Data are from four separate trials for the INF1FL-YFP (n = 189 cells total), INF1ΔC2-YFP (n = 172 cells total) and GFP-INF1C (n = 207 cells total) groups, and two trials for the Flag-FH2 (n = 166 cells total) or GFP (n = 176 cells total) groups, with SE of the mean shown. (J) The knockdown of INF1 using siRNA in NIH 3T3 cells resulted in a consistent reduction of acetylated tubulin levels. This did not involve a reduction in α-tubulin levels. Lamin B is also shown as a loading control. Scale bar, (A–H) 20 μm; (K and L) 20 μm.

Microtubule detyrosination is another marker of microtubule stability, and therefore we examined whether INF1 overexpression could be associated with an increase in detyrosinated microtubules. In contrast to microtubule acetylation, we were unable to detect an INF1FL-YFP–induced increase in detyrosinated microtubules (Supplemental Figure S5).

Because INF1 appeared to promote the formation of acetylated microtubules in NIH 3T3 cells, we next examined if the knockdown of INF1 in these cells would result in decreased levels of acetylated microtubules. As assessed by immunoblot analysis, we observed a decrease in acetylated tubulin levels in cells with reduced INF1 levels (Figure 9J). Expression of α-tubulin, which is the acetylated monomer (Eddé et al., 1991), was not decreased, indicating that it is only tubulin acetylation that is reduced and not tubulin expression levels. Finally, to determine if endogenous INF1 was targeted to acetylated microtubules in NIH 3T3 cells, we immunostained cells for both and looked at their colocalization. INF1 was found to be associated with acetylated microtubules (Figure 9K, L). Together these data show that INF1 is able to bind to microtubules and induce microtubule stabilization and acetylation.

DISCUSSION

Great progress has been made over the last 10 y in determining the function of the highly conserved domains found in the diaphanous-related formins (DRFs).

However, few studies have explored the function of more divergent members of the formin family. That formins can regulate the structure of both microfilaments and microtubules has been indicated by several studies (Ishizaki et al., 2001; Palazzo et al., 2001; Wen et al., 2004; Rosales-Nieves et al., 2006; Bartolini et al., 2008). How microtubule organization is coordinated by formins is still unclear, though the FH2 domain has been implicated as being important for mediating formin–microtubule interactions (Ishizaki et al., 2001; Rosales-Nieves et al., 2006; Bartolini et al., 2008). In this study, we show that the novel formin INF1 is unique in being discretely and is primarily associated with microtubules. The binding of INF1 to microtubules occurs directly via a novel C-terminal MTBD. INF1 is therefore the only formin family member identified to date that is likely to act primarily through direct effects on the microtubule cytoskeleton.

The unique structure of INF1, as well as the novel C-terminal polypeptide sequence downstream of its FH2 domain, appears to have arisen in the early chordates (Figure 1). The most closely related formins in nonchordate animals, which we have termed INFX proteins, are distinct in structure from INF1. They appear to be intermediate in structure to INF1 and INF2. INF1 and INF2 likely diverged from a common INFX-like ancestor, with the INF1 lineage losing sequence at the N-terminal end. Though the MTBD at the C-terminal end of INF1 contains sequence conserved in the vertebrates, no similar sequence was present in the INFX proteins. Our database searches have also found no similar MTBD in any other protein, indicating that this motif is unique to INF1.

The FH1/FH2 region of INF1 functions in a manner consistent with other formins in that it stimulates actin stress fiber formation and SRF activation (Figure 2). This activity is not autoregulated with INF1 overexpression, and INF1 does not possess any of the previously described formin autoregulatory domains. Within the INF1 C-terminal end, we have mapped a microtubule-binding domain. This MTBD was necessary and sufficient for proper localization of INF1 with microtubules. It is possible that endogenous INF1 FH1/FH2 activity may be regulated by its association with microtubules. This would be similar to the case of another actin regulator, GEF H1, which becomes active in stimulating RhoA after its release from microtubules (Chang et al., 2008). Future experiments will be needed to determine the impact of microtubule binding on INF1 regulation of actin filaments.

INF1 overexpression promoted the formation of acetylated microtubules in NIH 3T3 cells (Figure 9). Both the MTBD and a second region in the INF1 C-terminal end likely play roles in stimulating acetylated microtubule formation as INF1 fusion protein lacking the MTBD also induced an increase in acetylated microtubules, though to a reduced extent. Consistent with these results we find that siRNA-mediated knockdown of INF1 expression caused a significant reduction in the accumulation of acetylated tubulin (Figure 9J). The FH2 domain of INF1 did not induce accumulation of acetylated microtubules (Figure 9), nor did it associate discretely with microtubules or have any obvious affect on microtubule organization (data not shown). Thus, the N-terminal half of INF1 appears to primarily affect actin cytoskeleton structure and SRF activation, while the C-terminal half associates with, and promotes the modification of, the microtubule cytoskeleton.

Microtubule driven alterations to cell morphology are prominent in many cells types. One notable example is the necessary role that stable, acetylated microtubules play in the development of the neuronal axon (Witte et al., 2008). Acetylated microtubules establish polarity in neurons and are necessary for specifying axon formation. The association of INF1 with acetylated microtubules and its expression in neurons suggests that INF1 may play a modulatory role in the cytoskeletal organization of axons. It is of interest, then, that we observed INF1 to be an axonal protein in the cerebellum (Figure 5).

INF1 was also prominently expressed in ventricular muscle of the heart. In cardiomyocytes microtubules play a role in resisting shear stress (Nishimura et al., 2006) and are important in modulating the progression of cardiac hypertrophy (Cooper, 2006). Thus it is tempting to speculate that INF1 may also play a role in these processes.

With much of the formin protein family having been described only in recent years (Higgs and Peterson, 2005), the diversity of formin protein function remains to be demonstrated. INF1 is the first formin demonstrated to localize predominantly with microtubules and the first demonstrated to contain a MTBD that localizes discretely with microtubules. INF1 is involved in both F-actin and microtubule organization mediated through its N-terminal FH1/FH2 region and C-terminal MTBD and is unique among formins in being constitutively localized in a discrete manner along a cytoskeletal filament network. It will be of great interest to determine how the association of INF1 with microtubules is regulated and how microtubule binding may affect INF1-induced effects on actin dynamics.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Henry Higgs (Dartmouth Medical School, Hanover, NH) for providing the protein preparation protocol used in this study. We also thank Dr. Rashmi Kothary (Ottawa Health Research Institute, Ottawa, Canada) for commentary on the manuscript and for providing cell lines and mouse tissue samples. J.C. is supported by Grant NA 5762 from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario and Grant 68816 from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Abbreviations used:

- DAD

diaphanous autoregulatory domain

- DID

diaphanous inhibitory domain

- FH1 and FH2

formin homology 1 and 2 domains

- MTBD

microtubule-binding domain.

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E08-05-0469) on September 24, 2008.

REFERENCES

- Bartolini F., Moseley J. B., Schmoranzer J., Cassimeris L., Goode B. L., Gundersen G. G. The formin mDia2 stabilizes microtubules independently of its actin nucleation activity. J. Cell Biol. 2008;181:523–536. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200709029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y. C., Nalbant P., Birkenfeld J., Chang Z. F., Bokoch G. M. GEF-H1 couples nocodazole-induced microtubule disassembly to cell contractility via RhoA. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2008;19:2147–2153. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-12-1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chhabra E. S., Higgs H. N. INF2 Is a WASP homology 2 motif-containing formin that severs actin filaments and accelerates both polymerization and depolymerization. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;36:26754–26767. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604666200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper G. T. Cytoskeletal networks and the regulation of cardiac contractility: microtubules, hypertrophy, and cardiac dysfunction. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2006;291:H1003–H1014. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00132.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland J. W., Copeland S. J., Treisman R. Homo-oligomerization is essential for F-actin assembly by the formin family FH2 domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;48:50250–50256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404429200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland J. W., Treisman R. The diaphanous-related formin mDia1 controls serum response factor activity through its effects on actin polymerization. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2002;11:4088–4099. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02-06-0092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland S. J., Green B. J., Burchat S., Papalia G. A., Banner D., Copeland J. W. The diaphanous inhibitory domain/diaphanous autoregulatory domain interaction is able to mediate heterodimerization between mDia1 and mDia2. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;41:30120–30130. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703834200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddé B., Rossier J., Le Caer J. P., Berwald-Netter Y., Koulakoff A., Gros F., Denoulet P. A combination of posttranslational modifications is responsible for the production of neuronal alpha-tubulin heterogeneity. J. Cell. Biochem. 1991;46:134–142. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240460207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faix J., Grosse R. Staying in shape with formins. Dev. Cell. 2006;6:693–706. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geneste O., Copeland J. W., Treisman R. LIM kinase and Diaphanous cooperate to regulate serum response factor and actin dynamics. J. Cell Biol. 2002;5:831–838. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200203126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goode B. L., Eck M. J. Mechanism and function of formins in the control of actin assembly. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2007;76:593–627. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgs H. N. Formin proteins: a domain-based approach. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2005;6:342–353. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgs H. N., Peterson K. J. Phylogenetic analysis of the formin homology 2 domain. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;1:1–13. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-07-0565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizaki T., Morishima Y., Okamoto M., Furuyashiki T., Kato T., Narumiya S. Coordination of microtubules and the actin cytoskeleton by the Rho effector mDia1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;1:8–14. doi: 10.1038/35050598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji P., Jayapal S. R., Lodish H. F. Enucleation of cultured mouse fetal erythroblasts requires Rac GTPases and mDia2. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008;3:314–321. doi: 10.1038/ncb1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh M., Katoh M. Identification and characterization of human FHDC1, mouse Fhdc1 and zebrafish fhdc1 genes in silico. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2004;6:929–934. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millen K. J., Wurst W., Herrup K., Joyner A. L. Abnormal embryonic cerebellar development and patterning of postnatal foliation in two mouse Engrailed-2 mutants. Development. 1994;3:695–706. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.3.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miralles F., Posern G., Zaromytidou A. I., Treisman R. Actin dynamics control SRF activity by regulation of its coactivator MAL. Cell. 2003;3:329–342. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00278-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyagi Y., et al. Delphilin: a novel PDZ and formin homology domain-containing protein that synaptically colocalizes and interacts with glutamate receptor delta 2 subunit. J. Neurosci. 2002;3:803–814. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-03-00803.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita T., Mayanagi T., Sobue K. Reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton via transcriptional regulation of cytoskeletal/focal adhesion genes by myocardin-related transcription factors (MRTFs/MAL/MKLs) Exp. Cell Res. 2007;16:3432–3445. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagase T., Kikuno R., Hattori A., Kondo Y., Okumura K., Ohara O. Prediction of the coding sequences of unidentified human genes. XIX. The complete sequences of 100 new cDNA clones from brain which code for large proteins in vitro. DNA Res. 2000;6:347–355. doi: 10.1093/dnares/7.6.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura S., Nagai S., Katoh M., Yamashita H., Saeki Y., Okada J., Hisada T., Nagai R., Sugiura S. Microtubules modulate the stiffness of cardiomyocytes against shear stress. Circ. Res. 2006;98:81–87. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000197785.51819.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palazzo A. F., Cook T. A., Alberts A. S., Gundersen G. G. mDia mediates Rho-regulated formation and orientation of stable microtubules. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;8:723–729. doi: 10.1038/35087035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J., Kitchen S. M., West R. A., Sigler R., Eisenmann K. M., Alberts A. S. Myeloproliferative defects following targeting of the Drf1 gene encoding the mammalian diaphanous related formin mDia1. Cancer Res. 2007;16:7565–7571. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosales-Nieves A. E., Johndrow J. E., Keller L. C., Magie C. R., Pinto-Santini D. M., Parkhurst S. M. Coordination of microtubule and microfilament dynamics by Drosophila Rho1, Spire and Cappuccino. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006;4:367–376. doi: 10.1038/ncb1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakata D., Taniguchi H., Yasuda S., Adachi-Morishima A., Hamazaki Y., Nakayama R., Miki T., Minato N., Narumiya S. Impaired T lymphocyte trafficking in mice deficient in an actin-nucleating protein, mDia1. J. Exp. Med. 2007;9:2031–2038. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schratt G., Philippar U., Berger J., Schwarz H., Heidenreich O., Nordheim A. Serum response factor is crucial for actin cytoskeletal organization and focal adhesion assembly in embryonic stem cells. J. Cell Biol. 2002;4:737–750. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200106008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seth A., Otomo C., Rosen M. K. Autoinhibition regulates cellular localization and actin assembly activity of the diaphanous-related formins FRLalpha and mDia1. J. Cell Biol. 2006;5:701–713. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200605006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotiropoulos A., Gineitis D., Copeland J., Treisman R. Signal-regulated activation of serum response factor is mediated by changes in actin dynamics. Cell. 1999;2:159–169. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Y., Eng C. H., Schmoranzer J., Cabrera-Poch N., Morris E. J., Chen M., Wallar B. J., Alberts A. S., Gundersen G. G. EB1 and APC bind to mDia to stabilize microtubules downstream of Rho and promote cell migration. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004;9:820–830. doi: 10.1038/ncb1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte H., Neukirchen D., Bradke F. Microtubule stabilization specifies initial neuronal polarization. J. Cell Biol. 2008;3:619–632. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200707042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.