Abstract

The persistence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis despite prolonged chemotherapy represents a major obstacle for the control of tuberculosis. The mechanisms used by Mtb to persist in a quiescent state are largely unknown. Chemical genetic and genetic approaches were used here to study the physiology of hypoxic nonreplicating mycobacteria. We found that the intracellular concentration of ATP is five to six times lower in hypoxic nonreplicating Mtb cells compared with aerobic replicating bacteria, making them exquisitely sensitive to any further depletion. We show that de novo ATP synthesis is essential for the viability of hypoxic nonreplicating mycobacteria, requiring the cytoplasmic membrane to be fully energized. In addition, the anaerobic electron transport chain was demonstrated to be necessary for the generation of the protonmotive force. Surprisingly, the alternate ndh-2, but not -1, was shown to be the electron donor to the electron transport chain and to be essential to replenish the [NAD+] pool in hypoxic nonreplicating Mtb. Finally, we describe here the high bactericidal activity of the F0F1 ATP synthase inhibitor R207910 on hypoxic nonreplicating bacteria, supporting the potential of this drug candidate for shortening the time of tuberculosis therapy.

Keywords: anaerobic respiration, dormancy, ATP synthase, NADH dehydrogenase, Diarylquinoline

The main objective in antituberculosis drug discovery is to develop compounds that have a new mode of action and the potential to shorten the treatment of tuberculosis (TB) to ≤2 mo (1). These new drugs would revolutionize the TB chemotherapy and greatly contribute to the control of the disease. Indeed, long-term therapies increase the chances of treatment failure, TB relapse, and emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) strains (2). The unique long-term TB therapy is due to the presence of a subpopulation of hypoxic bacilli that are able to persist in a slow- or nongrowing state for extended period and are recalcitrant to killing by existing TB drugs (3–5). Despite being an obligate aerobe, Mtb is able to adapt to hypoxia by exiting the cell cycle and entering a quiescent state (3, 4, 6). Wayne and Hayes (6) have conducted pioneering studies of the dormant state of Mtb that culminated in the development of the in vitro Wayne model of persistence. In this model, Mtb cultures are subjected to self-generated oxygen depletion in sealed containers. Growth under such conditions leads to a physiologically well defined anaerobic nonreplicating synchronized state of the bacilli. When the oxygen tension in the sealed tubes is reduced to 0.06%, Mtb enters in a nonreplicating persistence phase (NRP) where it can survive for extended period without a significant drop in viability (6). Synchronized replication can be resumed upon reintroduction of oxygen (6, 7). Previous work suggested that in vitro-grown nonreplicating tubercle bacilli have a reduced susceptibility to the cidal activity of TB drugs (6). This physiological state of the bacillus is being referred to as “drug tolerant” or “phenotypically drug resistant” (3–5). One of the major obstacles in finding and developing drugs that are active against hypoxic nonreplicating bacilli is the poor understanding of the mechanisms used by Mtb to persist in the total absence of visible growth. Recent work has begun to shed light on the mechanisms involved in Mtb persistence. These studies consistently show the up-regulation of the dosR regulon (8–12). The DosR/DosS two-component system regulates a set of 50 genes under oxygen-limited conditions (9). In addition, a Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette–Guérin strain deficient for the expression of dosR is not able to survive under hypoxic conditions (13). However, these studies failed to give a clear understanding of the mechanisms underlying persistence and the physiological state in which hypoxic nonreplicating Mtb exists. In particular, the energetic requirements and mechanisms used by Mtb to replenish the [NAD+] pool under hypoxia are largely unknown (4). In the current study, we have used chemical genetic and genetic approaches to investigate the membrane bioenergetics in hypoxic nonreplicating mycobacteria and the mechanisms underlying ATP production, with the idea that this may contribute to the identification of novel targets and new levels of intervention to shorten the time of TB chemotherapy.

Results

Respiratory Functions Are Essential for Maintaining the Viability of Hypoxic Nongrowing Mycobacteria.

Previous work suggested that in vitro grown nonreplicating tubercle bacilli have a reduced susceptibility to the current anti-TB drugs (6). However, a systematic comparison of the cidal activity of anti-TB drugs against exponentially growing vs. quiescent bacilli has never been carried out. The minimum bactericidal concentration 90% (MBC90s; concentrations that kill 90% of an exponentially growing population) and the Wayne Cidal Concentration 90% (WCC90s; concentrations that kill 90% of a quiescent population) were then determined for the major first- and second-line anti-TB drugs. Table 1 shows that all anti-TB drugs tested were indeed much less active against hypoxic nonreplicating Mtb cells, compared with replicating bacteria. Rifampicin and moxifloxacin were 50-fold less cidal, whereas isoniazid (INH) and ethionamide were totally inactive against nonreplicating Mtb. The observed drastic loss in cidal activities against quiescent bacilli is consistent with the concept that the macromolecular synthesis pathways targeted by the current TB drugs are not essential in the nongrowing form of the bacilli (6).

Table 1.

MBC90 and WCC90 of some antimycobacterial agents against Mtb H37Rv

| Antibiotics | MBC90, μM | WCC90, μM | WCC90/MBC90 ratio | Mode of action/target |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rifampicin | 0.01 | 0.5 | 50 | RNA polymerase |

| Streptomycin | 0.125 | 5 | 40 | Protein synthesis |

| Isoniazid | 0.40 | >200 | >500 | Cell wall synthesis |

| Ethionamide | 3.5 | >200 | >57 | Cell wall synthesis |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.125 | 6 | 48 | DNA gyrase |

| Nigericin | 1.25 | 0.5 | 0.4 | ΔpH |

| Valinomycin | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | ΔΨ |

| R207910 | 5 | 2.5 | 0.5 | F0F1 ATP synthase |

| DCCD | >500 | 80 | <0.16 | F0F1 ATP synthase |

| Thioridazine | 40 | 20 | 0.5 | ndh-2 |

| Rotenone | >160 | >160 | - | ndh-1 |

| Metronidazole | <500 | 100 | <0.2 | Hypoxia control (3, 4, 6) |

The MBC90 and the WCC90 were determined for known anti-TB agents and for some respiratory inhibitors. The ratio between the WCC90 and the MBC90 is shown. The experiment was carried out at least three times in triplicate.

Recent microarray studies showed that key complexes of the electron transport chain (ETC) are down-regulated in nongrowing hypoxic or nutrient-starved Mtb (8, 9, 12, 14). We reasoned that, because the respiratory functions and the factors involved in energy production are maintained at a low level, they may represent a point of metabolic vulnerability in nonreplicating Mtb cells. Using various inhibitors, we have addressed the requirement of the protonmotive force (PMF), the F0F1 ATP synthase, and the electron donors NADH-dehydrogenase (ndh)-1 and -2 in quiescent hypoxic Mtb. The MBC90s and WCC90s were determined for the recently described F0F1 ATP synthase inhibitors R207910 (15) and N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCCD), for the ionophores valinomycin and nigericin, which cause dissipation of membrane potential (ΔΨ) and proton gradient (ΔpH), respectively, and for rotenone and thioridazine, which inhibit ndh-1 and -2, respectively (16–19). Table 1 shows that all of the compounds but rotenone, killed quiescent Mtb. Similar results were obtained by using M. bovis bacillus Calmette–Guérin (data not shown). More importantly, the cidal activities of these compounds were found to be higher against quiescent bacilli than against growing organisms (Table 1). These observations indicate that the respiratory functions and the mechanisms involved in ATP production represent a point of metabolic vulnerability in nongrowing mycobacteria.

De Novo ATP Synthesis Is Essential for Survival of Hypoxic Nongrowing Mtb.

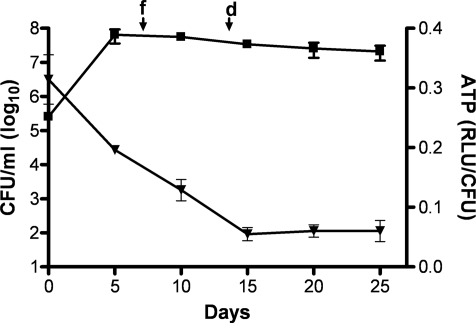

To address directly the energetic status of hypoxic nongrowing mycobacteria, the intracellular ATP concentration was measured and compared with growing aerobic mycobacteria. The ATP content was found to be 5-fold lower in hypoxic nonreplicating mycobacteria (0.44 ± 0.22 attomoles/cfu and 2.50 ± 0.40 attomoles/cfu, respectively). To gain further insight into the maintenance of the ATP homeostasis in hypoxic nonreplicating Mtb, we monitored the ATP concentration over a 25-day period in the Wayne dormancy model. The intracellular ATP concentration progressively reduced as the oxygen tension dropped (Fig. 1). The ATP content was at a minimum in early NRP phase (15 days of the Wayne model) and then remained constant throughout the stationary phase (Fig. 1). To determine whether the respiratory F0F1 ATP synthase is required to maintain this reduced ATP level, the intracellular ATP content was measured in quiescent mycobacteria exposed to the F0F1 ATP synthase inhibitor R207910 (15, 20). We found that R207910 reduced the ATP level in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A), and that this decrease in intracellular ATP level correlated with an increased killing activity (Fig. 2B). A similar effect was observed when hypoxic nongrowing Mtb was incubated with DCCD, another respiratory ATP synthase inhibitor (Fig. 2). The drop in ATP observed with R207910 and DCCD was specific, because none of the first- and second-line TB drugs tested in this model had any significant effect on the ATP level [Fig. 2A and supporting information (SI) Table S1, SI Text]. These results show that a reduced ATP level is maintained in hypoxic nonreplicating mycobacteria, and that de novo ATP synthesis is required for the maintenance of Mtb survival.

Fig. 1.

ATP level is low and stable in hypoxic nongrowing mycobacteria. Dynamics of ATP concentration (filled triangles) and cfu (filled squares) during Wayne dormancy in Mtb H37Rv monitored over a period of 25 days. Mtb H37Rv cells were grown in closed test tubes with head space ratio of 0.5 and incubated at 37°C on magnetic stir platform, as described (6, 7). The times when the methylene blue (oxygen consumption indicator) exhibited noticeable fading (f) and complete decolorization (d) are shown.

Fig. 2.

F0F1 ATP synthase inhibitors decrease ATP concentration and viability of hypoxic nongrowing Mtb H37Rv. Hypoxic nongrowing Mtb cells were incubated with varying concentration of R207910 and DCCD over a period of 5 days at 37°C under anaerobic conditions. The ATP levels (A) and viability (B) are shown. Rifampicin (Rif) at 1 μM and metronidazole (MTZ) at 200 μM were used as controls. The experiments were carried out three times in triplicate and results are given as the mean values and standard deviations.

Hypoxic Nongrowing Bacilli Maintain Their Membrane Energized.

The F0F1 ATP synthase utilizes the PMF to drive ATP production. The two components contributing to the PMF are the membrane potential (ΔΨ) and the transmembrane proton concentration gradient (ΔpH). The chemical probing shown in Table 1 demonstrated that the ionophores dissipating the ΔΨ (valinomycin) and ΔpH (nigericin) are cidal on quiescent bacilli, suggesting that the membrane of nonreplicating bacilli is energized and that this potential energy (the PMF) is required for ATP production and survival of the bacilli. To confirm the membrane energization, the actual ΔΨ and ΔpH were measured in growing and quiescent organisms.

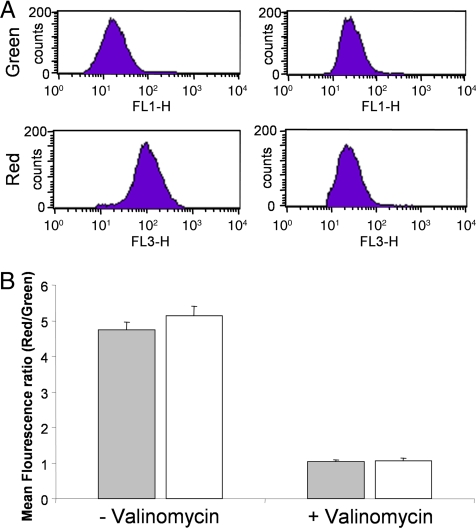

The ΔΨ was first detected by using the cationic fluorescent dye DiOC2 (3, 21) in aerobic replicating and hypoxic nongrowing Mtb. Results showed that ΔΨ was similar in intensity in both cell populations (Fig. 3). To confirm this result, the ΔΨ was then measured with [3H]tetraphenylphosphonium bromide (TPP+), as described (22–24). Results showed that ΔΨ in growing and nonreplicating hypoxic cells was identical (Table 2), confirming that quiescent Mtb are able to maintain their membranes polarized to the same extent as growing cells. In addition, it was possible to depolarize the membranes of hypoxic nongrowing cells by using the ionophore valinomycin (known to dissipate the ΔΨ but not ΔpH), suggesting that the maintenance of the ΔΨ is an active process (Fig. 2A and Table 2). Results obtained with valinomycin were specific, because the ionophore nigericin (dissipates the ΔpH but not the ΔΨ) or rifampicin did not affect the ΔΨ value of the cells.

Fig. 3.

Aerobically growing and hypoxic nongrowing Mtb H37Rv cells have a similar membrane potential. (A) FACS analysis of DiOC2 (3) stained hypoxic nongrowing Mtb H37Rv with or without prior treatment using 5 μM valinomycin. Shown are the mean red and green fluorescence intensities. (B) The mean fluorescence intensity ratio (red/green) of the aerobically growing (filled box) and hypoxic nongrowing (empty box) Mtb H37Rv, incubated with 30 μM DiOC2 (3) for 15 min in either the presence or absence of 5 μM valinomycin are shown.

Table 2.

PMF in aerobically growing and hypoxic nongrowing Mtb H37Rv

| Drugs (μM) | Δψ, mV | ΔpH, mV | PMF, mV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aerobic growing mycobacteria | No drug | 66.2 ± 4.4 | 45.3 ± 5.5 | 111.5 ± 9.9 |

| Valinomycin (5) | – | 35.8 ± 2.3 | 35.8 ± 2.3 | |

| Nigericin (5) | 63.1 ± 4.0 | – | 63.1 ± 4.0 | |

| Rifampicin (1) | 62.7 ± 3.2 | 50.6 ± 3.2 | 113.3 ± 6.4 | |

| Hypoxic nongrowing mycobacteria | No drug | 73.1 ± 4.2 | 40.6 ± 9.2 | 113.7 ± 13.4 |

| Valinomycin (5) | – | 31.9 ± 5.3 | 31.9 ± 5.3 | |

| Nigericin (5) | 69.2 ± 10.8 | – | 69.2 ± 10.8 | |

| Rifampicin (1) | 65.1 ± 9.3 | 42.3 ± 8.6 | 107.4 ± 17.9 |

The ΔΨ, ΔpH, and PMF were measured in aerobic growing and hypoxic nonreplicating Mtb maintained in Dubos medium (pH of 6.6). The experiment was carried out three times in triplicate; one of the representative experiment is shown.

The ΔpH was measured by using [14C]benzoic acid as a pH probe (23, 24). We found a comparable ΔpH in replicating and hypoxic nongrowing bacilli (Table 2). The dissipation of the ΔpH was observed when the cells were exposed to nigericin but not to rifampicin or valinomycin (Table 2). Because the PMF is usually used by the F0F1 ATP synthase for ATP production, the ATP level was measured in hypoxic nonreplicating Mtb in the presence of nigericin or valinomycin. The results show a reduction of ATP level in a dose-dependent manner that was associated with a loss of viability (Fig. S1). Altogether, our observations demonstrated that the membrane of hypoxic nonreplicating Mtb is fully energized and that both components of the PMF, ΔΨ and ΔpH, are required for ATP synthesis.

ndh-2 Acts as an Electron Donor for the Anaerobic ETC and Is Essential for the Maintenance of the PMF.

The PMF is usually generated and maintained by the ETC. The ndh is described as one of the electron donors to initiate ETC through NADH oxidation (25). We have observed that the ndh-2 inhibitor thioridazine displayed a significant cidal activity against quiescent bacilli, whereas the ndh-1 inhibitor rotenone was not active (Fig. 4B). The ATP level was also significantly reduced upon thioridazine treatment whereas rotenone had no effect (Fig. 4A and Table S1). These results suggested that ndh-2, but not -1, acts as the electron donor for the anaerobic ETC in Mtb. The essentiality of ndh-2 in hypoxic nonreplicating Mtb was confirmed by using trifluoperazine, another ndh-2-specific inhibitor (17). As observed for thioridazine, trifluoperazine was cidal for quiescent bacilli, with a WCC90 of 20 μM (data not shown). In contrast, exposure of nongrowing bacilli to another ndh-1 inhibitor, Piericidin A, did not show any effect on intracellular ATP level and viability (data not shown). To rule out the possibility that Rotenone and Piericidin A were not active because of a limited cellular penetration, a Mtb strain deficient for the expression of ndh-1 activity was constructed in which the entire nuoA-N operon was deleted. No survival defect was observed for this mutant when grown in hypoxic conditions, demonstrating that ndh-1 is not essential in quiescent mycobacteria (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

ndh-2 is essential for survival of hypoxic nongrowing Mtb H37Rv. Varying concentrations of rotenone (ndh-1 inhibitor, 80 μM) and thioridazine (ndh-2 inhibitor) were incubated with nongrowing Mtb cells over a period of 5 days at 37°C under anaerobic conditions. The ATP levels (A) and viability (B) of nonreplicating/hypoxic Mtb H37Rv are shown. Rifampicin (Rif) at 1 μM, MTZ at 200 μM and INH at 25 μM were used as controls. The experiments were carried out three times in triplicate, and results are given as the mean values and standard deviations.

We further tested the role of ndh-2 in the generation of the PMF. We showed that inhibition of ndh-2 with thioridazine resulted in a dose-dependent dissipation of the ΔΨ, therefore linking the ndh-2 activity to the generation of the PMF (Fig. 5). When tested under similar experimental conditions, rifampicin and the R207910 compound had no effect on the PMF (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

ndh-2 inhibitor reduces the membrane potential (Δψ) of hypoxic nongrowing Mtb cells. Effect of various antimycobacterial agents on the Δψ of hypoxic nongrowing Mtb H37Rv. FACS analysis showing the mean fluorescence intensity ratio (red/green) of DiOC2 (3) stained hypoxic Mtb incubated with various drugs over a period of 5 days at 37°C under anaerobic conditions. The experiments were carried out three times in triplicate and results are given as the mean values and standard deviations.

ndh-2 Is Required to Replenish the [NAD+] Pool in Hypoxic Nonreplicating Mtb.

Because [NAD+] is the main cellular oxidant, the restoration of the [NAD+] pool is essential for the maintenance of cellular functions. The mechanisms by which hypoxic nonreplicating mycobacteria replenish their [NAD+] pool are still unknown. The involvement of isocitrate dehydrogenase and a putative glycine dehydrogenase has been proposed (3) but not yet demonstrated. Because ndh-2 initiates the anaerobic ETC, we hypothesized this dehydrogenase might be involved in the restoration of the [NAD+] pool in hypoxic quiescent mycobacteria. [NAD+] and [NADH] concentrations were measured in hypoxic nongrowing mycobacteria 3 h after addition of the ndh-2 inhibitor thioridazine. Results show that, compared with the control group, the [NAD+] concentration significantly decreased, whereas the [NADH] concentration increased in thioridazine-treated mycobacteria (Table 3), resulting in a [NADH]/[NAD+] ratio 2.65-fold higher than that measured in the nontreated group (Table 3). The effect was specific to ndh-2-inhibitors because treatment with rifampicin or with R207910 compound did not change the [NADH]/[NAD+] ratio significantly (Table 3). These results therefore demonstrate the importance of ndh-2 in replenishing the pool of [NAD+] in hypoxic nonreplicating mycobacteria.

Table 3.

Redox status of [NADH/[NAD+] in hypoxic nonreplicating Mtb H37Rv

| Drug treatment (μM) | NAD+, μM | NADH, μM | NADH/NAD+ ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| No drug | 0.95 ± 0.11 | 0.3 ± 0.03 | 0.32 ± 0.01 |

| Thioridazine (40) | 0.72 ± 0.08 | 0.39 ± 0.04 | 0.54 ± 0.11* |

| Thioridazine (80) | 0.66 ± 0.04* | 0.56 ± 0.11* | 0.85 ± 0.22* |

| Rifampicin (1) | 0.90 ± 0.03 | 0.37 ± 0.03 | 0.41 ± 0.05 |

| R207910 (5) | 0.99 ± 0.03 | 0.38 ± 0.04 | 0.38 ± 0.05 |

| R207910 (10) | 1.16 ± 0.02 | 0.37 ± 0.02 | 0.31 ± 0.02 |

Hypoxic nonreplicating Mtb H37Rv was incubated with the ndh-2 inhibitor thioridazine for 3 h under anaerobic conditions before quantification of the [NADH]/[NAD+] ratio. The compounds were used at 2- and 4-fold of the WCC90 concentration for thioridazine and R207910 and at 2-fold the WCC90 concentration for rifampicin. The experiments were carried out three times in triplicate; one of the representative experiments is shown with means and standard deviations.

*Mean values are statistically different (P < 0.05) compared with the mean values of the no-drug-treated Mtb cells.

Discussion

Early research on mycobacteria respiration led to the perception that Mtb is a strict aerobe. Lawrence Wayne challenged this concept 30 years ago as he started to study the physiology of hypoxic Mtb cells (3, 26). Mtb survives in the absence of replication upon gradual oxygen depletion and becomes phenotypically drug-resistant (6). The concept that hypoxic nonreplicating mycobacteria are responsible for the length of the treatment and for latent TB infection is now well accepted as a working model. The Wayne model of in vitro persistence has become a valuable tool to study the molecular mechanism of persistence and to predict the sterilizing activity of new anti-TB drugs against hypoxic nonreplicating mycobacteria (3, 4). However, the physiology, including the metabolic and energetic status of quiescent bacilli, has been poorly studied.

In this work, we have investigated the energetic status of hypoxic nonreplicating mycobacteria. We found that hypoxic nongrowing Mtb displays a reduced but sustained pool of ATP when compared with growing Mtb, making them exquisitely sensitive to any further ATP depletion, with a 3- to 4-fold ATP depletion resulting in >90% cell death. In contrast, aerobic growing Mtb is more robust, because a depletion of at least 90% of the pool of ATP was necessary to observe a cidal effect. Moreover, we show here that a collapse of the PMF (ΔΨ or ΔpH) led to the reduction of ATP level and to viability loss, indicating that (i) de novo ATP synthesis is required to maintain the low ATP level in hypoxic nonreplicating mycobacteria, and (ii) a fully energized status of the cytoplasmic membrane is necessary to produce ATP. These observations therefore point to the respiratory functions as potential drug targets in hypoxic nonreplicating mycobacteria. Maintenance of ATP homeostasis represents the first point of metabolic vulnerability described in quiescent mycobacteria. Moreover, the greater potency of the respiratory inhibitors observed against quiescent mycobacteria compared with growing aerobic mycobacteria suggests that quiescent bacilli are not intrinsically phenotypically drug-resistant but are sensitive to killing when a proper pathway is targeted.

The R207910 inhibitor was shown to be highly active on hypoxic nonreplicating mycobacteria. This compound targets the F0F1 ATP synthase and is the most promising anti-TB drug candidate currently under investigation (15, 20, 27). R207910 reduces the time of therapy in animal models (15, 28) and shows superior sterilization activity compared with standard anti-TB drugs.¶. In addition, it was shown to be safe when given to humans (15), demonstrating that energy depletion can be specifically achieved in Mtb without affecting mammalian mitochondria. The administration of R207910 to MDR TB patients and patients with persistent TB may further demonstrate the high curative potential of this drug.

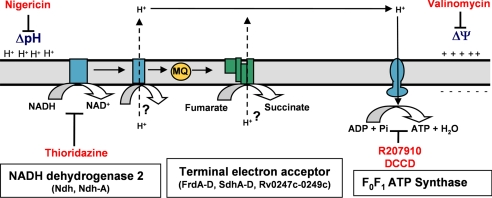

We further characterized the anaerobic ETC in hypoxic mycobacteria and showed that ndh-2 but not -1 contributes to generating the PMF. We showed that the Mtb ndh-2-specific inhibitors thioridazine and trifluoperazine (17, 19) block the initiation of the anaerobic ETC and dissipate the PMF in hypoxic quiescent mycobacteria, whereas ndh-1 does not contribute to anaerobic survival. These results are surprising because, in Escherichia coli, for example, ndh-2 is not a coupling enzyme, i.e., it does not contribute directly to the generation of the PMF (29) and is not required for anaerobic growth (29, 30). Instead, the E. coli ndh-1 is the dehydrogenase responsible for the oxidization of [NADH] and the initiation of the ETC in anaerobiosis (30). The ndh-2-initiated ETC produces less ATP compared with ndh-1 for a comparable amount of [NADH] (29). Because [NAD+] is the main cellular oxidant, the restoration of the [NAD+] pool makes [NADH] turnover a top priority over ATP synthesis (29). Additional mechanisms involved in energy production and/or maintenance of [NAD+] pool have been suggested (4, 31–33). However, these attractive hypotheses await further experimental evidence. These findings therefore support the development of new phenothiazine analogues as a new class of anti-TB drugs (17, 19, 27, 34).

The ETC-generated ATP synthesis depends on the presence of a terminal electron acceptor. In facultative anaerobes, anaerobic respiration is observed only when an anaerobic terminal electron acceptor is provided exogenously (35). Interestingly, we found that in hypoxic nonreplicating Mtb, the presence of an exogenous terminal electron acceptor is dispensable for ATP synthesis through the F0F1 ATP synthase. We propose that Mtb might use endogenously produced fumarate as a terminal electron acceptor for energy production in hypoxic nongrowing Mtb. Efforts are being pursued in our laboratory to address the role of the fumarate reductase activity in the survival of and ATP production in hypoxic nonreplicating mycobacteria.

The identity of the coupling complex in the mycobacterial anaerobic ETC has yet to be determined. As proposed by Boshoff and Barry, the F420 oxido-reductase might be involved in the generation of the PMF in an anaerobic ETC initiated by ndh-2 and with fumarate as the terminal electron acceptor (4). It is also conceivable that, similarly to what has been described in Bacillus subtilis, the succinate dehydrogenase SdhCDAB operating in the reverse direction contributes to the generation of the PMF (36) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Model of the anaerobic electron transport chain in hypoxic nonreplicating Mtb H37Rv.

In conclusion, the respiratory functions leading to de novo ATP synthesis and [NAD+] regeneration might represent the Achilles' heel of hypoxic nonreplicating mycobacteria (Fig. 6), opening new avenues for the development of new anti-TB drugs possibly allowing a shorter and more effective therapy in MDR and persistent TB patients.

Methods

Chemicals.

Moxifloxacin was obtained from Chempacific. All other compounds were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. The compound R207910 was synthesized as described earlier (15).

[3H]water, [3H]tetra phenyl phosphonium (TPP+), [14C]benzoic acid, and [14C]sucrose were obtained from GE Healthcare radiochemicals division.

Strains and Media.

Mtb H37Rv (ATCC #27294) was maintained in Dubos liquid medium. Hypoxic nonreplicating Mtb were generated under conditions of slow stirring in sealed tubes, as described (6, 7).

Determination of Bactericidal Concentrations.

The MBC90 was defined as the minimal concentration of antibiotics that killed 90% of the initial inoculum in 5 days. Approximately 1 × 106 cfu/ml were exposed to varying concentrations of chemicals in sterile 96-well flat bottom plates for 5 days aerobically. cfu was estimated on days 0 and 5 of drug exposure by plating the bacteria on 7H11-agar plates. A 90% reduction in cfu on day 5 compared with day 0 was the MBC90.

The WCC90 was defined as the concentration of antibiotics that killed 90% of hypoxic nonreplicating Mtb in 5 days. Hypoxic nonreplicating mycobacteria were exposed to varying concentration of antibiotics in sterile 96-well flat bottom plates for 5 days under anaerobic conditions. cfu were enumerated at days 0 and 5. Metronidazole (MTZ) at 400 μM and INH at 25 μM were used in all experiments as positive and negative controls, respectively. A 90% reduction in cfu on day 5 of drug exposure compared with day 0 was the WCC90.

Quantification of Intracellular ATP.

Intracellular ATP was quantified by using the BacTiter-Glo Microbial Cell Viability Assay Kit (Promega). Aliquots of 100 μl of bacteria were collected at various time points and immediately heat-inactivated. Twenty-five microliters of cell lysates were transferred into 96-well white plates, mixed with an equal volume of the BacTiter-Glo reagent and incubated for 5 min in the dark. The emitted luminescence was detected by using a luminometer (Safire2, Tecan Instruments) and was expressed as relative luminescence units. ATP standards ranging from 0.1 to 100 nM were also included in all of the experiments as internal control.

Detection and Measurement of the Membrane Potential.

The ΔΨ was detected by using BacLight bacterial membrane potential kit (Invitrogen). Briefly, Mtb cells were diluted to an OD600 of ≈0.005 (≈106 cfu/ml) in fresh Dubos liquid medium. Hypoxic nonreplicating Mtb were diluted in degazed Dubos liquid medium to maintain anaerobiosis. One milliliter of diluted cells was stained with 10 μl of 3 mM DiOC2 (3) (3,3′-diethyloxa-carbocyanine iodine, fluorescent dye) for 15–30 min at 37°C. After staining, the cells were centrifuged and resuspended with an equal volume of 2% paraformaldehyde. The stained cells were analyzed by FACS by using 488-nm excitation and emission filters suitable for fluorescein and Texas red dye (21).

The ΔΨ was measured as described (22–24). Briefly, similar concentrations of aerobic and hypoxic Mtb cells (≈1 × 109 cfu/ml) were incubated with 10 μM [3H]TPP+ (380 mCi/mmol) for 30 min at 37°C. The bacteria were then centrifuged at 9,300 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was transferred to an Eppendorf tube and the pellet resuspended in 100-μl aliquot of perchloric acid 20% (vol/vol). Aliquots of 100 μl of both cell pellet and supernatant were added with equal volume of scintillation mixture and the radioactivity was measured with a scintillation counter (GE Healthcare). The membrane potential was calculated according to the method of Rottenberg (23).

Measurement of the Intracellular pH.

Mtb cells were centrifuged and resuspended in Dubos liquid medium with varying pH to a cell density of ≈1 × 109 cfu/ml. [14C]benzoic acid was used as a pH probe, [3H] water and [14C] sucrose were used to calculate the internal cell volume. Mycobacteria were incubated with 1 μCi/ml [14C] benzoic acid for 30 min at 37°C. The cells were centrifuged, and the radioactivity in pellet and supernatant was measured as described above. The internal pH was calculated as described (23, 24).

Determination of [NADH] and [NAD+] Concentrations.

[NADH] and [NAD+] were extracted and quantified as described (37). Mtb cells were preincubated either with or without compounds for 3 h before extraction of [NAD+] and [NADH] under anaerobic conditions.

The intracellular [NADH] and [NAD+] concentrations were measured with a cycling assay, as described (38, 39).

Genetic Deletion Mycobacteria.

The nuoA-N gene was disrupted by allelic exchange method by using the pYUB854 plasmid (40). A sacB-lacZ cassette was excised from the pGOAL17 (41) and ligated into the PacI site of pYUB854 containing 5′ and 3′ flank of the nuoA-N locus. The final plasmids were UV-irradiated (42) before electroporation into Mtb.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We acknowledge Helena Boshoff and Cliff Barry (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda) and Sabine Ehrt and Dirk Schnappinger (Weill Cornell Medical College, New York) for stimulating discussions during the course of this study. We acknowledge Melvin Au, Lay Har Lim, and Seow Hwee Ng (Novartis Institute for Tropical Diseases, Singapore) for technical assistance, William Jacobs (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York) for the gift of the pYUB854 plasmid, and Tanya Parish (Barts and the London, London) for the gift of the pGOAL17 plasmid.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0711697105/DCSupplemental.

Veziris N, Ibrahim M, Truffot-Pernot C, Andries K, Jarlier V, 47th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, September 18, 2007, Chicago, p. 53.

References

- 1.GATB. Scientific blueprint for tuberculosis drug development. Tuberculosis. 2001;81:1–52. doi: 10.1054/tube.2001.0288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitchison DA. Shortening the treatment of tuberculosis. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:187–188. doi: 10.1038/nbt0205-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wayne LG, Sohaskey CD. Nonreplicating persistence of. Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Ann Rev Microbiol. 2001;55:139–163. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boshoff HI, Barry CE. Tuberculosis: Metabolism and respiration in the absence of growth. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:70–80. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dick T. Dormant tubercle bacilli: The key to more effective TB chemotherapy? J Antimicrob Chemother. 2001;47:117–118. doi: 10.1093/jac/47.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wayne LG, Hayes LG. An in vitro model for sequential study of shiftdown of. Mycobacterium tuberculosis through two stages of nonreplicating persistence. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2062–2069. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.2062-2069.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim A, Eleuterio M, Hutter B, Murugasu-Oei B, Dick T. Oxygen depletion-induced dormancy in Mycobacterium bovis BCG. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2252–2256. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.7.2252-2256.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muttucumaru DG, Roberts G, Hinds J, Stabler RA, Parish T. Gene expression profile of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a non-replicating state. Tuberculosis. 2004;84:239–246. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park HD, et al. Rv3133c/dosR is a transcription factor that mediates the hypoxic response of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol. 2003;48:833–843. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03474.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sherman DR, et al. Regulation of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis hypoxic response gene encoding alpha-rystallin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:7534–7539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121172498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Voskuil MI, Visconti KC, Schoolnik GK. Mycobacterium tuberculosis gene expression during adaptation to stationary phase and low-oxygen dormancy. Tuberculosis. 2004;84:218–227. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schnappinger D, et al. Transcriptional adaptation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis within macrophages: Insights into the phagosomal environment. J Exp Med. 2003;198:693–704. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boon C, Dick T. Mycobacterium bovis BCG response regulator essential for hypoxic dormancy. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:6760–6767. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.24.6760-6767.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts DM, Liao RP, Wisedchaisri G, Hol WG, Sherman DR. Two sensor kinases contribute to the hypoxic response of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:23082–23087. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401230200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andries K, et al. A diarylquinoline drug active on the ATP synthase of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science. 2005;307:223–227. doi: 10.1126/science.1106753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gutman M, Singer TP, Beinert H, Casida JE. Reaction sites of rotenone, piericidin A, and amytal in relation to the nonheme iron components of NADH dehydrogenase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1970;65:763–770. doi: 10.1073/pnas.65.3.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weinstein EA, et al. Inhibitors of type II NADH:menaquinone oxidoreductase represent a class of antitubercular drugs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:4548–4553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500469102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yano T, Li L-S, Weinstein E, Teh J-S, Rubin H. Steady-state kinetics and inhibitory action of antitubercular phenothiazines on Mycobacterium tuberculosis type-II NADH-menaquinone oxidoreductase (NDH-2) J Biol Chem. 2006;281:11456–11463. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508844200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teh JS, Yano T, Rubin H. Type II NADH:menaquinone oxidoreductase of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2007;7:169–181. doi: 10.2174/187152607781001781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koul A, et al. Diarylquinolines target subunit c of mycobacterial ATP synthase. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:323–324. doi: 10.1038/nchembio884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Novo D, Perlmutter NG, Hunt RH, Shapiro HM. Accurate flow cytometric membrane potential measurement in bacteria using diethyloxacarbocyanine and a ratiometric technique. Cytometry. 1999;35:55–63. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0320(19990101)35:1<55::aid-cyto8>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Y, Zhang H, Sun Z. Susceptibility of. Mycobacterium tuberculosis to weak acids. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;52:56–60. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rottenberg H. The measurement of membrane potential and deltapH in cells, organelles, and vesicles. Methods Enzymol. 1979;55:547–569. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(79)55066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rao M, Streur TL, Aldwell FE, Cook GM. Intracellular pH regulation by Mycobacterium smegmatis and Mycobacterium bovi. BCG. Microbiology. 2001;147 doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-4-1017. 017–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.White D. The Physiology and Biochemistry of Prokaryotes. New York: Oxford Univ Press; 2000. pp. 103–131. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wayne LG. Dynamics of submerged growth of. Mycobacterium tuberculosis under aerobic and microaerophilic conditions. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1976;114:807–811. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1976.114.4.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cox RA, Cook GM. Growth regulation in the mycobacterial cell. Curr Mol Med. 2007;7:231–245. doi: 10.2174/156652407780598584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ibrahim M, et al. Synergistic activity of R207910 combined with pyrazinamide against murine tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:1011–1015. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00898-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Melo AMP, Bandeiras TM, Teixeira M. New insights into type II NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductases. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2004;68:603–616. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.4.603-616.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tran QH, Bongaerts J, Vlad D, Unden G. Requirement for the proton-pumping NADH dehydrogenase I of Escherichia coli in respiration of NADH to fumarate and its bioenergetic implications. Eur J Biochem. 1997;244:155–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wayne LG, Lin KY. Glyoxylate metabolism and adaptation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to survival under anaerobic conditions. Infect Immun. 1982;37:1042–1049. doi: 10.1128/iai.37.3.1042-1049.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hutter B, Singh M. Properties of the 40 kDa antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a functional l-alanine dehydrogenase. Biochem J. 1999;343:669–672. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldman DS. Enzyme systems in the mycobacteria. VII. Purification, properties and mechanism of action of the alanine dehydrogenase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1959;34:527–539. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(59)90305-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xie Z, Siddiqi N, Rubin EJ. Differential antibiotic susceptibilities of starved Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:4778–4780. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.11.4778-4780.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singleton P. Bacteria in Biology, Biotechnology and Medicine. New York: Wiley; 2004. pp. 81–116. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schnorpfeil M, Janausch IG, Biel S, Kroger A, Unden G. Generation of a proton potential by succinate dehydrogenase of. Bacillus subtilis functioning as a fumarate reductase. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:3069–3074. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vilcheze C, et al. Altered NADH/NAD+ ratio mediates coresistance to isoniazid and ethionamide in mycobacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:708–720. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.2.708-720.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bernofsky C, Swan M. An improved cycling assay for nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide. Anal Biochem. 1973;53:452–458. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(73)90094-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leonardo MR, Dailly Y, Clark DP. Role of NAD in regulating the adhE gene of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6013–6018. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.20.6013-6018.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bardarov S, et al. Specialized transduction: An efficient method for generating marked and unmarked targeted gene disruptions in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, M bovis BCG, and M smegmatis. Microbiology. 2002;148:3007–3017. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-10-3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parish T, Stoker NG. Use of a flexible cassette method to generate a double unmarked Mycobacterium tuberculosis tlyA plcABC mutant by gene replacement. Microbiology. 2000;146:1969–1975. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-8-1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hinds J, et al. Enhanced gene replacement in mycobacteria. Microbiology. 1999;145:519–527. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-3-519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.