Abstract

The efficiency of cross-presentation of exogenous antigens by dendritic cells (DCs) would seem to be related to the level of antigen escape from massive degradation mediated by lysosomal proteases in an acidic environment. Here, we demonstrate that a short course of treatment with chloroquine in mice during primary immunization with soluble antigens improved the cross-priming of naïve CD8+ T lymphocytes in vivo. More specifically, priming of chloroquine-treated mice with soluble ovalbumin (OVA), OVA associated with alum, or OVA pulsed on DCs was more effective in inducing OVA-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes than was priming of untreated mice. We conclude that chloroquine treatment improves the cross-presentation capacity of DCs and thus the size of effector and memory CD8+ T cells during vaccination.

Cross-presentation refers to the ability of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) to present exogenous antigens to CD8+ T cells. This process has been shown to play a crucial role in priming CD8+ T-cell-dependent responses against soluble, cell-associated, or pathogen-derived antigens which are not directly expressed by APCs (5, 7, 25, 55, 57). Among APCs, dendritic cells (DCs) are the most efficient at inducing antigen-specific immune responses and the only cells adept in cross-priming (3, 13, 41). They use receptor-independent pinocytosis, macropinocytosis, and phagocytosis as well as a range of receptor-mediated mechanisms to acquire and cross-present antigens (37, 52). The intracellular pathways for exogenous antigen presentation are strictly regulated in DCs, and several studies have been aimed at dissecting these processes and characterizing factors and potential modulatory mechanisms affecting cross-presentation (2, 11, 12, 17, 18, 22, 24).

It has recently been demonstrated that cross-presentation of soluble antigens to CD8+ T cells was effectively improved by inhibiting the endosomal acidification of DCs with NH4Cl or chloroquine in vitro (1, 22). Both chloroquine and NH4Cl are lysosomotropic agents, which diffuse across the membrane and inhibit intravesicular acidification, which is critical to activating several acid proteases that induce proteolysis of antigens in the endocytic compartments (52, 58). Chloroquine has long been used to increase the efficiency of DNA transfection by inhibiting degradation of DNA absorbed by the cells (31) and has been further reported to cause direct lysosomal membrane permeabilization (6). Accapezzato et al. (1) have recently shown that the administration of a booster dose of anti-hepatitis B virus vaccine, associated with a short course of chloroquine treatment in vivo, significantly enhanced the recall of antigen-specific memory CD8+ T cells in healthy individuals compared to the group not treated with chloroquine. Altogether, these data highlighted that the efficiency of cross-presentation would seem to be directly related to the level of antigen escape from destruction by endosomal/lysosomal proteolysis and to the ensuing export of the appropriate proteasome substrates into the class I processing pathway (1, 2, 12, 22, 39, 46, 56). However, the correlation of the antigen escape from degradation mediated by drugs with the efficiency of cross-priming of naïve T cells remains to be assessed.

Here, we have evaluated the efficacy of chloroquine treatment in inducing a primary immune response in mice upon injection of soluble chicken ovalbumin (OVA) alone, OVA associated with alum, or OVA pulsed on DCs. Overall, our results clearly indicate for the first time that short-course treatment of mice with drugs such as chloroquine, aimed at reducing antigen degradation in the endocytic compartments of DCs, improves the priming of naïve CD8+ T-cell responses against soluble antigens in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Female C57BL/6J mice (H-2b) were obtained from Charles River, Calco, Italy, and maintained at the Istituto Superiore di Sanità according to the institutional guidelines. The T-cell-receptor-transgenic mouse line OT-I, expressing a T-cell receptor recognizing an H-2b-restricted OVA257-264 epitope, SIINFEKL, was kindly supplied by M. Bellone (San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan, Italy). For all experiments, mice between the ages of 6 and 12 weeks were used.

DCs.

DCs from spleens of naïve mice were purified as described previously (51). Briefly, spleen fragments were digested for 25 min at room temperature with collagenase and DNase (Sigma). EDTA (5 mM, pH 7.2; Sigma) was added for an additional 5 min to allow disruption of DC-T-cell complexes. After 2 h of incubation at 37°C in tissue culture-treated dishes, nonadherent cells were removed by gentle pipetting and the adherent cells were cultured overnight in DC medium (RPMI 1640 containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 4 mM l-glutamine, 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 10 ng/ml of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor) (Peprotech, United Kingdom). DCs were purified by immunomagnetic bead cell sorting using anti-CD11c-conjugated magnetic beads (N418 clone; Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The purity of the enriched CD11c+ cell preparations was usually in the range between 85 and 90%.

Mouse immunization. (i) With free soluble protein.

Mice were injected intravenously (i.v.) with different concentrations of soluble OVA and treated subcutaneously (s.c.) with 800 μg of chloroquine 2 h before and 6 h after priming.

(ii) With alum-OVA.

Mice were immunized once by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 200 μg of OVA protein adsorbed onto aluminum hydroxide adjuvant (Alum; Sigma). These mice were treated s.c. with 800 μg of chloroquine 2 h before and 6 h after priming.

(iii) With OVA-loaded DCs (OVA-DCs).

Splenic DCs (5 × 106/ml) were pretreated with 20 μM of chloroquine (Sigma Chemical Co.) for 30 min or medium alone, followed by the addition of soluble OVA (3 to 5 mg/ml; grade V; Sigma) or 1 μg/ml of SIINFEKL peptide. Alternatively, DCs were pretreated with chloroquine, with 30 ng/ml of phorbol myristate acetate (PMA), or with both chloroquine and PMA, followed by the addition of soluble OVA. After 1 h of incubation at 37°C, extensive washes, and a 2-h chase, in the continuous presence or absence of chloroquine, 5 × 105 cells were used to immunize mice i.v. Mice receiving chloroquine-treated OVA-DCs were treated s.c. with 800 μg of chloroquine 2 h before and 6 h after priming.

Cross-presentation assays in vitro.

OT-I cells were isolated from the spleen and lymph nodes of OT-I mice and further enriched for CD8+ T cells by treatment with monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) to CD4 (GK1.5) and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II (TIB120), followed by sheep anti-mouse and sheep anti-rat Dynabeads (Dynal A.S., Oslo, Norway). The final preparations from the lymphoid organs contained 75 to 85% CD8+ T cells. For presentation of soluble OVA, purified DCs were suspended in serum-free RPMI at a concentration of 4 × 106 cells/ml and preincubated for 30 min at 37°C with or without different concentrations of chloroquine (2 μM, 6.5 μM, and 20 μM), followed by the addition of OVA (0.5 mg/ml) or 1 μg/ml of SIINFEKL peptide. After 1 h of incubation at 37°C, the cells were washed, added to microtiter plates, and coincubated with 105 OT-I cells, in the continued presence or absence of chloroquine. The cells were incubated for 72 h, and 1 μCi/well [3H]thymidine (Amersham Biosciences, United Kingdom) was added 12 to 15 h before harvesting. Data are shown as mean cpm of triplicate wells minus mean cpm of corresponding control wells in the absence of antigen.

In vivo proliferation assays.

For analysis of in vivo proliferation, the enriched OT-I cells were labeled with 5- (and 6-)carboxyfluorescein diacetate, succinimidyl ester (CFSE), as previously described (32). Briefly, semipurified OT-I cells, as described above, were resuspended in PBS containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (Sigma) at 107 cells/ml and incubated with CFSE (Molecular Probes) at 5 μM for 10 min at 37°C. Cells were subsequently washed in PBS and then transferred via tail vein injection to C57BL/6 mice (2 × 106 cells/mouse) that were subsequently primed 1 day later with different concentrations of soluble OVA or OVA-DCs. Three days after priming, these mice were euthanized and cells from pooled axillary, mediastinal, and inguinal lymph nodes were isolated and stained with anti-CD8-phycoerythrin (PE) for flow cytometry analysis.

In vitro cytotoxic assays.

Spleens were removed surgically 9 days after priming and prepared as a single-cell suspension. Splenocytes were stimulated in vitro for 5 days with a 2:1 ratio of splenic APCs taken from naïve mice that were pulsed for 90 min with 0.1 mM SIINFEKL peptide and then washed and gamma irradiated. Effector cells were then assayed for cytotoxic activity on 51Cr-labeled EL4 target cells pulsed or not with SIINFEKL peptide at the indicated effector/target ratios. The amount of 51Cr released was determined by gamma counting, and the percent specific lysis was calculated from triplicate samples as follows: [(experimental cpm − spontaneous cpm)/(maximal cpm − spontaneous cpm)] × 100. Spontaneous release was determined from target cells incubated in the absence of effector cells and was <5% in all experiments.

Detection of OVA-specific antibodies.

Serum was collected from individual mice on day 14 after immunization with alum-OVA, and anti-OVA antibody titers were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Briefly, 96-well plates (Nunc-Immuno) were coated by overnight incubation at 4°C with 100 μl of PBS containing OVA at 40 μg/ml. Plates were blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin in PBS for 2 h, and serial twofold dilutions of serum samples in PBS were added to the wells. After a 2-h incubation, plates were then washed with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG), IgG1, or IgG2a antibodies (Southern Biotechnology Associates). After three additional washes, the plates were then incubated with p-nitrophenyl phosphate (Sigma) for 1 h at room temperature. Absorbance was read at 405 nm with a microplate reader (Bio-Rad).

Virus challenge.

The recombinant influenza A virus WSN/OVA-I, which expresses the SIINFEKL epitope, was previously generated by reverse genetics (50) and grown on Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. Mice were anesthetized with 2,2,2-tribromomethanol (Avertin) before intranasal challenge with 8 × 105 PFU of WSN/OVA-I virus and euthanized 7 days postinfection.

Intracellular IFN-γ staining.

Cells derived from spleens and pooled mediastinal lymph nodes (MLN) of infected mice were cultured for 2 h in 96-well U-bottomed plates at 37°C in the presence or absence of 10 μM OVA257-264 peptide (20). Brefeldin A (10 μg/ml) was added to each well, and the cells were incubated for an additional 4 h. The responder cells were then washed twice in brefeldin A-containing PBS (PBS-brefeldin A), treated with MAb to the Fc-γIII/II receptor to block nonspecific antibodies, and stained with a rat anti-mouse CD8-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) MAb (Pharmingen). The cells were then washed again with PBS-brefeldin A, fixed in 1% formaldehyde in PBS for 20 min., washed in PBS, placed in 0.5% saponin (Sigma) in PBS for 20 min, and incubated with a rat anti-mouse IFN-γ-PE MAb (Pharmingen) or a rat IgG1-PE control MAb. Samples were then examined by FACSCalibur flow cytometry.

Tetramer staining.

The MHC class I peptide tetramer, SIINFEKL/Kb, conjugated to PE, was synthesized by Proimmune Limited (Oxford, United Kingdom). Bulk splenocytes (∼5 × 106) were stained with PE-conjugated SIINFEKL/Kb tetramer, an FITC-conjugated anti-CD62L antibody (Pharmingen), and a tricolor-labeled anti-CD8 antibody (Caltag) for 30 min on ice (20). Samples were examined by FACSCalibur flow cytometry, and in the analysis CD8+ T cells were selected and the data plotted as tetramer (PE) versus CD62L (FITC), as indicated.

Statistical analysis.

Comparisons between experimental groups were made by using the two-tailed Student t test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Chloroquine improves cross-presentation of soluble OVA to naïve OT-I cells in vitro and in vivo.

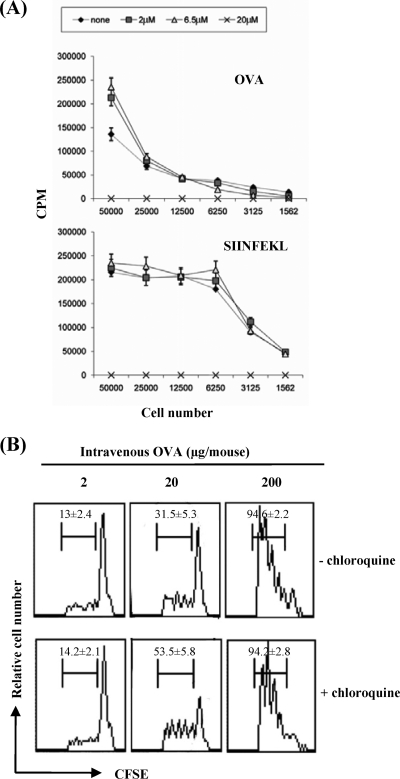

Freshly isolated spleen DCs are induced to mature through overnight culture in vitro, so that they acquire the capacity to process and present newly encountered antigens (54). Chloroquine and NH4Cl have been shown to inhibit the intravesicular acidification and marked proteolysis that occur in partially and fully mature DCs (1, 22) and also in nonprofessional APCs (i.e., T2 cells deficient in transporter associated with antigen processing) (40). Here, we first assessed the effect of chloroquine treatment on the capacity of splenic DCs to process and present exogenous soluble OVA by using an in vitro proliferation assay of OVA-specific transgenic CD8+ T cells (OT-I cells). The presence of low concentrations of chloroquine, 6.5 μM and 2 μM, throughout the duration of the proliferative assay improved the cross-presentation to naïve T cells (Fig. 1A). Chloroquine treatment did not affect the peptide presentation of splenic DCs loaded with the SIINFEKL peptide (OVA257-264) to CD8+ T cells at these low concentrations. By contrast, the highest dose of chloroquine (20 μM) showed an inhibitory effect on T-cell proliferation in both systems, as cell numbers similar to those of the non-chloroquine-treated cells in the absence of antigen were observed. Thus, chloroquine treatment improved the cross-presentation of antigens in maturing DCs, otherwise susceptible to rapid endosomal protease degradation, sustained by the acidic pH (1).

FIG. 1.

Effect of chloroquine on cross-presentation of soluble OVA in vitro and cross-priming of OT-I cells in vivo. (A) OVA- or SIINFEKL-DCs were incubated with OT-I cells in the absence or presence of different concentrations of chloroquine. T-cell proliferation was measured by [3H]thymidine incorporation and expressed as mean (± standard deviation) cpm of triplicate cultures. (B) CFSE-labeled OT-I cells were adoptively transferred into naïve mice that were subsequently primed 1 day later with different concentrations of soluble OVA. Lymph nodes were analyzed 3 days later. All profiles obtained were gated on CD8+ T cells, and the frequencies of cells that had undergone one or more divisions are indicated (average of n = 6 mice/group; data are represented as means ± standard deviations).

We then examined the efficiency of cross-presentation of soluble OVA in vivo in the presence of chloroquine. In vivo cross-presentation of a soluble antigen that is not cell associated is more strictly dose related (35). It has been reported that very small amounts of cell-associated OVA are able to stimulate OT-I cells in vivo (29). On the other hand, free soluble OVA is presented much less efficiently than cell-associated OVA to OT-I cells. In our system, CFSE-labeled OT-I cells were transferred into recipient mice treated 1 day later with a single i.v. injection of various concentrations of OVA diluted in PBS and in the presence or absence of chloroquine. The proliferative responses of these cells derived from the lymph nodes were analyzed 3 days after adoptive transfer by flow cytometry (Fig. 1B). An evident in vivo OT-I proliferative response was seen in the lymphoid organs of mice given 200 μg of OVA, whereas low levels of proliferation were seen in mice given the lowest concentration (2 μg of OVA), independently from the chloroquine treatment. In mice given an intermediate dose (20 μg OVA), those receiving chloroquine during priming showed a higher proliferation of CFSE-labeled OT-I cells than did the untreated mice (P < 0.05), thus confirming the ability of chloroquine treatment to improve cross-presentation of soluble antigens to naïve CD8+ T cells in vivo.

Chloroquine improves induction of OVA-specific CTLs upon alum-OVA immunization in vivo.

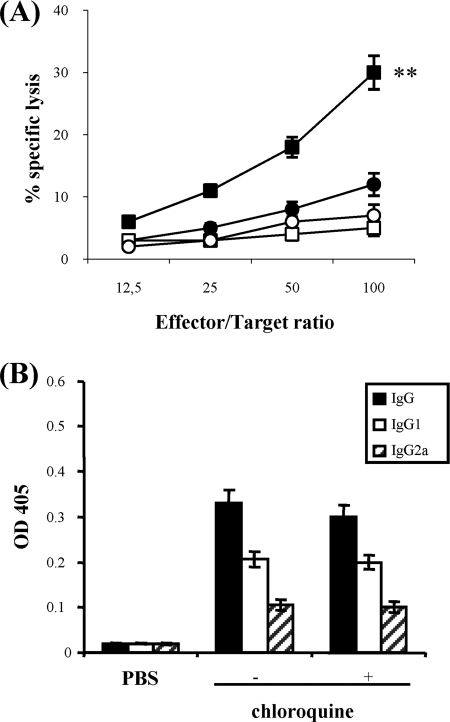

Then we wondered whether chloroquine was capable of improving cross-priming of not only an enriched population of transferred OT-I cells but also naïve OVA-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) precursors in vivo. It has been previously shown that adjuvants are required for priming CTLs with native OVA and some particulate forms of OVA. In particular, OVA in complete Freund's adjuvant (27), OVA incorporated into immunostimulating complex adjuvant (21) or into liposomes (10), or OVA adsorbed onto alum and mixed with a saponin surfactant (QS-21) (36) primed CTLs in vivo. There is very little evidence that aluminum adjuvants generate MHC class I cytotoxic T cells (30). Alum alone is a poor inducer of Th1 cellular immune responses and stimulates the production of IgE and IgG1 antibodies in mice, which is consistent with a dominant profile of Th2 lymphocyte immune response (19). Here, we examined if chloroquine treatment could improve the induction of CTLs specific for the immunodominant epitope SIINFEKL, by a single inoculation of mice with alum-OVA. To this end, spleen cells from mice primed with alum-OVA 9 days earlier were cultured with irradiated peptide-loaded syngeneic cells for 5 days and then assayed for cytolytic activity. As shown in Fig. 2A, only mice immunized in the presence of chloroquine generated detectable OVA-specific CTLs, whereas those immunized in the absence of the drug did not (P < 0.01 at the effector/target ratio of 100:1). Although the increase in antigen-specific CTL activity was not substantially high, it was nonetheless relevant, considering the poor induction of CTLs by alum-based adjuvants. We also tested the primed mice for the presence of OVA-specific IgG antibodies: in both treated and untreated groups, the antibody levels were comparable (P > 0.05), and IgG1 was the dominant isotype, independently of the chloroquine treatment (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Effect of chloroquine treatment during immunization of mice with a single dose of alum-OVA. (A) Induction of CTL responses in mice. Groups of chloroquine-treated (squares) and untreated (circles) mice (n = 4) were immunized i.p. with 200 μg of alum-OVA, as described in Materials and Methods. Nine days later, spleens were removed and stimulated in vitro with SIINFEKL-loaded, irradiated splenocytes. After 5 days, a 51Cr release assay using SIINFEKL-pulsed EL4 (closed symbols) and EL4 (open symbols) targets was performed. The results are expressed as the means ± standard deviations. **, P < 0.01 in comparison of untreated with chloroquine-treated mice. (B) Humoral immune responses. Sera from mice (n = 5) were obtained 2 weeks after immunization, and OVA-specific IgG isotypes in the samples of individual mice were detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, as described in Materials and Methods. The values shown represent the means (± standard deviations) of 1:100-diluted sera.

Chloroquine treatment during priming with alum-OVA improves the induction of memory CD8+ T cells.

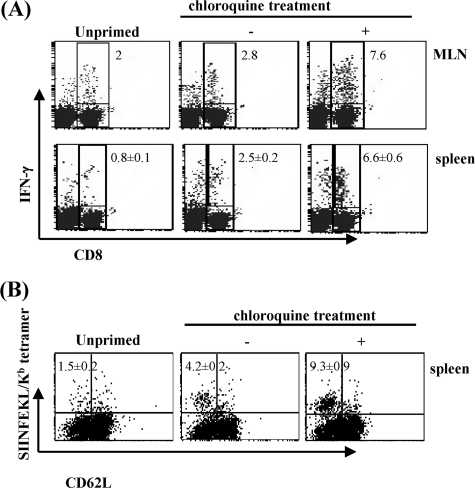

It was necessary to determine whether the increased numbers of primed CTLs due to the combination of a single dose of alum-OVA and chloroquine treatment have the capacity to develop effective long-term memory T cells. The magnitude of a secondary immune response correlates with the size of memory T cells induced by the cross-presented antigen during priming (28, 34). To this end, mice were vaccinated with alum-OVA in the presence or absence of chloroquine and 8 weeks later we elicited a recall response by boosting them with WSN/OVA-I virus bearing the T-cell epitope SIINFEKL in the stalk region of the viral neuraminidase (50). Seven days after the boost, we determined the proportion of OVA-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes in the pooled MLN and the spleens that were functional by intracellular IFN-γ staining. Approximately 7.6% and 6.6% of CD8+ T cells in MLN and bulk splenocytes, respectively, of chloroquine-treated mice produced IFN-γ after stimulation with OVA peptide, versus approximately 2.8% and 2.5% of CD8+ T cells from the untreated mice (P < 0.01) (Fig. 3A). Lower levels of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells were found at this time of infection in the unprimed mice. Moreover, lymphocytes that were not stimulated with peptide showed background staining similar to that of the isotype control immunoglobulin (<1%; data not shown). The higher proportion of CD8+ T cells in bulk splenocytes of chloroquine-treated mice that showed as MHC class I-SIINFEKL tetramer positive and CD62LLo (Fig. 3B) further indicates that priming of mice in the presence of this drug induces larger CD8+ T-cell memory responses.

FIG. 3.

CD8+ T-cell recall responses in mice primed with alum-OVA. Groups of five mice were primed i.p. with 200 μg of alum-OVA, in the presence or absence of chloroquine. Eight weeks later, they were intranasally infected with 8 × 105 PFU of WSN/OVA-I virus. Seven days postchallenge pooled MLN and spleen cells from individual mice were tested for IFN-γ production (A). The values shown are percentages (± standard deviations) of CD8+ T cells that were IFN-γ positive. Splenocytes were also stained with SIINFEKL/Kb tetramer and antibodies to CD8 and CD62L (B). Only CD8+ T cells are included in the plots. The values shown are percentages (± standard deviations) of CD8+ T cells that were SIINFEKL/Kb tetramer positive and activated (CD62L). The results from one out of three experiments with similar outcomes are shown.

Overall, these results show that concurrent immunization of mice with alum-OVA and chloroquine treatment supports higher CD8+ T-cell expansion of primary effectors and thus a large population of memory CD8+ T cells that undergo a rapid expansion and recruitment following pulmonary infection with the recombinant influenza virus.

Chloroquine improves cross-priming via its effect on DCs.

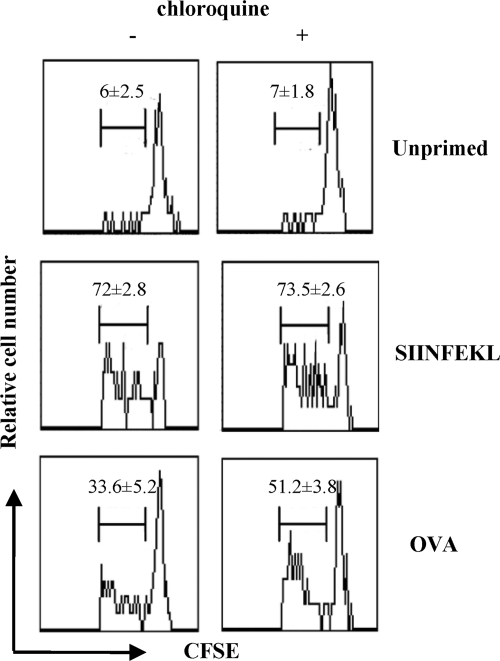

To ascertain that the improvement in cross-priming through chloroquine in vivo was related to chloroquine's capacity to increase cross-presentation by DCs, as observed in our studies in vitro (Fig. 1A), CFSE-labeled transgenic OT-I cells were transferred into C57BL/6 mice primed 1 day later with OVA-DCs, which had been treated with chloroquine. In particular, splenic DCs cultured overnight were pretreated in vitro with chloroquine or medium alone for 30 min followed by the addition of 3 mg of soluble OVA or 1 μg of SIINFEKL peptide for 1 h and extensively washed. After a 2-hour chase, chloroquine-treated OVA-DCs were injected into mice, who received chloroquine s.c. (in order to guarantee a continuous presence of chloroquine during antigen processing in vivo), whereas the untreated OVA-DCs were injected into chloroquine-untreated mice. Three days after priming, recipients were euthanized and the lymphoid organs were analyzed by flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 4, OT-I cells proliferated more in the lymphoid organs of chloroquine-treated mice than in untreated mice which had received OVA-DCs (P < 0.05), thus confirming that chloroquine treatment improves in vivo cross-priming of naïve CD8+ T cells by maturing DCs. It is improbable that cross-priming was due to contaminating soluble OVA, because OVA-DCs were extensively washed and chased before the immunization procedures and because cross-priming by soluble antigens (including OVA) generally requires high antigen concentrations (Fig. 1B) (29). Similar percentages of proliferating OT-I cells induced upon immunization with SIINFEKL-DCs were measured independently of the chloroquine treatment.

FIG. 4.

Effect of chloroquine on cross-priming in vivo by OVA-DCs. CFSE-labeled OT-I cells were adoptively transferred into mice, which were inoculated 1 day later with OVA-DCs or SIINFEKL-DCs, in the presence or absence of chloroquine, as described in Materials and Methods. Lymph nodes were analyzed 3 days later. All profiles obtained were gated on CD8+ T cells, and the frequencies of cells that have undergone one or more divisions are indicated (average of n = 6 mice/group; data are represented as means ± standard deviations).

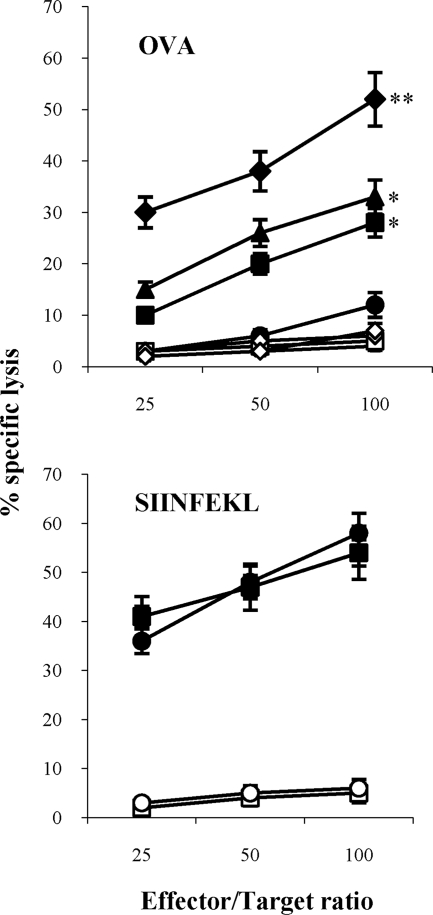

To further corroborate the finding that chloroquine was capable of improving the primary antigen-specific response of CTL precursors in vivo by boosting the cross-presentation capacity of DCs (Fig. 1A), we tested the additive effect of PMA and chloroquine because the former has already been demonstrated to improve cross-presentation (37, 38) and to function as a nonspecific Rho GTPase activator capable of promoting endocytosis and antigen presentation by murine DCs (47). The presence of OVA-specific CTL effector cells in the spleens was determined on day 9 by 51Cr release assay, after one round of restimulation in vitro in the presence of peptide-loaded syngeneic cells (Fig. 5). Groups of mice injected with SIINFEKL-pulsed DCs were used in these assays to make sure that the chloroquine treatment in vivo did not affect the ability of DCs to present the synthetic peptide. Mice treated with chloroquine and receiving chloroquine-treated OVA-DCs efficiently induced SIINFEKL-specific CTLs, whereas the untreated group of mice did not. Furthermore, the combined use of chloroquine and PMA in vitro and subsequent injection in chloroquine-treated mice determined an additive effect that more closely correlates the functional role of the chloroquine with the reduced antigen proteolysis and enhanced cross-presentation which occurs in maturing DCs. As expected, the injection of splenic DCs stimulated with PMA alone in the presence of OVA gave lower levels of antigen-specific CTL induction than those obtained with the combined use of both the drugs, thus being similar to levels obtained by the use of chloroquine alone (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Induction of OVA-specific CTLs by DCs. DCs were incubated with soluble OVA in the absence (circles) or presence of chloroquine (squares), PMA (triangles), or both chloroquine and PMA (diamonds). Alternatively, DCs were loaded with the SIINFEKL peptide in the absence (circles) or presence of chloroquine (squares) and injected into groups of four mice, as described in Materials and Methods. Nine days later, spleens were removed and stimulated in vitro with SIINFEKL-loaded, irradiated splenocytes. After 5 days, a 51Cr release assay using SIINFEKL-pulsed EL4 (closed symbols) and EL4 (open symbols) targets was performed. The results are expressed as the means ± standard deviations. *, P < 0.05, or **, P < 0.01, versus untreated mice.

DISCUSSION

To investigate whether chloroquine treatment had some effect on cross-priming CD8+ T-cell-mediated responses in vivo, we explored vaccination strategies based on OVA as soluble protein, alum-adsorbed OVA, or OVA pulsed on DCs in C57BL/6 mice. Our data demonstrate that in all these cases, and independently of the presence of adjuvants, concurrent chloroquine treatment improved the priming provided by these immunogens. These results further corroborate the previous evidence that chloroquine enhanced human CD8+ T-cell recall responses against viral antigens (1). Here, we used overnight cultured murine splenic DCs, which showed higher cross-presentation of the immunodominant CTL epitope of OVA to OT-I cells in the presence of chloroquine, in both in vitro and in vivo proliferative assays. Although our studies do not provide direct evidence on the mechanisms responsible for an enhanced CD8+ T-cell response, this effect can probably be explained by the chloroquine-mediated rescue of OVA protein from the endocytic degradation that occurs in maturing DCs, as well as facilitating export of the antigen to the cytosol for proteasome-dependent processing (1).

The additive effect of inducing antigen-specific CTLs in vivo following immunization with OVA-DCs treated with chloroquine combined with PMA further supports this evidence. PMA has been shown to promote antigen presentation of murine DCs through enhanced endocytosis mediated by Rho family GTPases (38, 47). In addition, PMA stimulates a NOX2-mediated production of reactive oxygen species which results in proton consumption in DC phagosomes, reduced antigen degradation, and ultimately improved cross-presentation (43). Thus, it may be speculated that the observed additive effect of chloroquine in conjunction with PMA may be explained by increased cytosolic availability of antigen mediated by a more efficient uptake, reduced endosomal degradation, and facilitated export of the endocytosed soluble OVA to the cytosol. Recent findings highlight several questions concerning the relative contributions of endocytosis and DC subpopulations in determining the ability for cross-presentation (13-15, 44). In this context, Burgdorf et al. (8) described in CD8α+ DCs a mannose receptor-mediated internalization of soluble OVA into a stable early endosomal compartment for subsequent cross-presentation through a proteasome-dependent mechanism, whereas the constitutively pinocytosed antigen was exclusively transported into lysosomes for MHC II-restricted presentation. Thus, it would be of interest to determine whether chloroquine improves cross-presentation of soluble OVA sampled by receptor-mediated endocytosis, constitutive pinocytosis, or both.

The magnitude of the primary immune response, as well as the extent of memory T-cell populations, is dependent on the dose of antigen used for immunization (28, 34, 35, 53). It has also been demonstrated that the size of the memory T-cell pool is the major determinant for the magnitude of secondary immune responses, in addition to the effective antigen dose during challenge (23, 28, 34). In this study, mice were immunized only with a single dose of antigen, in the presence or absence of chloroquine. Then, we boosted them with WSN/OVA-I virus to fully establish a secondary SIINFEKL-specific T-cell stimulation. By this means, we could clearly show a higher recall response in mice that were primed in the presence of chloroquine. Although our analysis was exclusively focused on numbers and functions of CD8+ T cells specific to the immunodominant epitope OVA257-264, it may be envisioned that these results could also be extended to subdominant epitopes of OVA protein (48).

Chloroquine is known to block MHC class II-dependent antigen processing and presentation by affecting lysosomal acidification and invariant chain dissociation from the MHC class II molecules (42). Continuous treatment with high doses of chloroquine in vivo is an established immunosuppressive therapy for autoimmune diseases (16). In our proliferative assay in vitro, we found an inhibitory effect by using 20 μM, and some concerns may arise about the dosage of chloroquine that we used in our experiments in vivo for priming mice. Indeed, mice treated with the drug did not show any distress or change in animal behavior. The improved CD8+ T-cell responses observed in all experiments in chloroquine-treated mice provide evidence that both a short course treatment of chloroquine during priming and the rapid clearance of the drug in normal mice (9) may account for the beneficial effects in vivo. This immunization setting implies that chloroquine favorably affects antigen uptake and processing, whereas maintaining high levels of the drug throughout the proliferative and CTL assays in vitro could negatively affect priming and effector function activities (33, 45). It has been reported that OVA-specific CD8+ T-cell responses are dependent on CD4+ T cells (4) and that generating stable and functional CD8+ T-cell memory relies critically on the help of CD4+ T cells at priming (26, 49). In this context, the improved antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell response associated with established long-term T-cell memory in chloroquine-treated mice indicates that T-cell helper functions were preserved and effective during immunization. Additionally, the levels of OVA-specific antibodies measured in chloroquine-treated and untreated mice after a single injection of antigen were comparable, as also reported for the antigen-specific antibody response measured in immune healthy individuals boosted with the hepatitis B virus vaccine (1).

In summary, our data provide further evidence that drugs capable of inhibiting endosomal acidification of DCs could improve the cross-presentation of exogenous soluble antigens to specific CD8+ T cells in vivo. Improving cross-presentation in generating immune responses after prophylactic or immunotherapeutic immunization is of significant interest for the development of optimal vaccination strategies. In this context, our results encourage further studies to evaluate the possible use of drugs combined with a variety of soluble antigens in the attempt to inhibit excessive antigen degradation and thus facilitate the induction of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells by these immunogens.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Giuliana Verrone and Monica Gabrielli for assistance with the animal experiments and Roberto Gilardi and Sabrina Tocchio for help with the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the Istituto Superiore di Sanità; from the Italian Concerted Action on HIV-AIDS Vaccine Development (ICAV); from Ministero dell'Istruzione, dell'Università e della Ricerca Project 2006; and from Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro 2004-2007.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 27 August 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Accapezzato, D., V. Visco, V. Francavilla, C. Molette, T. Donato, M. Paroli, M. U. Mondelli, M. Doria, M. R. Torrisi, and V. Barnaba. 2005. Chloroquine enhances human CD8+ T cell responses against soluble antigens in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 202:817-828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ackerman, A. L., A. Giodini, and P. Cresswell. 2006. A role for the endoplasmic reticulum protein retrotranslocation machinery during crosspresentation by dendritic cells. Immunity 25:607-617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banchereau, J., and R. M. Steinman. 1998. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature 392:245-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennett, S. R. M., F. R. Carbone, F. Karamalis, J. F. A. P. Miller, and W. R. Heath. 1997. Induction of CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte response by cross-priming requires cognate CD4+ T cell help. J. Exp. Med. 186:65-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bevan, M. J. 1976. Cross-priming for a secondary cytotoxic response to minor H antigens with H-2 congenic cells which do not cross-react in the cytotoxic assay. J. Exp. Med. 143:1283-1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boya, P., R. A. Gonzales-Polo, D. Poncet, K. Andreau, H. La Vieira, T. Roumier, J.-L. Perfettini, and G. Kroemer. 2003. Mitochondrial membrane permeabilization is a critical step of lysosome-initiated apoptosis induced by hydroxychloroquine. Oncogene 22:3927-3936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brossart, P., and M. J. Bevan. 1997. Presentation of exogenous protein antigens on major histocompatibility complex class I molecules by dendritic cells: pathway of presentation and regulation by cytokines. Blood 90:1594-1599. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burgdorf, S., A. Kautz, V. Bohnert, P. A. Knolle, and C. Kurts. 2007. Distinct pathways of antigen uptake and intracellular routing in CD4 and CD8 T cell activation. Science 316:612-616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cambie, G., F. Verdier, C. Gaudebout, F. Clavier, and H. Ginsburg. 1994. The pharmacokinetics of chloroquine in healthy and Plasmodium chabaudi-infected mice: implications for chronotherapy. Parasite 1:219-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collins, D., K. Findlay, and C. V. Harding. 1992. Processing of exogenous liposome-encapsulated antigens in vivo generates class I MHC-restricted T cell responses. J. Immunol. 148:3336-3341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delamarre, L., H. Holcombe, and I. Mellman. 2003. Presentation of exogenous antigens on major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and MHC class II molecules is differentially regulated during dendritic cell maturation. J. Exp. Med. 198:111-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delamarre, L., R. Couture, I. Mellman, and E. S. Trombetta. 2006. Enhancing immunogenicity by limiting susceptibility to lysosomal proteolysis. J. Exp. Med. 203:2049-2055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Den Haan, J. M., S. M. Lehar, and M. J. Bevan. 2000. CD8+ but not CD8- dendritic cells cross-prime cytotoxic T cells in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 192:1685-1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Den Haan, J. M., and M. J. Bevan. 2002. Constitutive versus activation-dependent cross-presentation of immune complexes by CD8+ and CD8− dendritic cells in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 196:817-827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dudziak, D., A. O. Kamphorst, G. F. Heidkamp, V. R. Buchholz, C. Trumpheller, S. Yamazaki, C. Cheong, K. Liu, H-W. Lee, C. G. Park, R. Steinman, and M. C. Nussenzweig. 2007. Differential antigen processing by dendritic cell subsets in vivo. Science 315:107-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fox, R. I. 1993. Mechanism of action of hydroxychloroquine as an antirheumatic drug. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 23:82-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gil-Torregrosa, B. C., A. M. Lennon-Dumenil, B. Kessler, P. Guermonprez, H. L. Ploegh, D. Fruci, P. van Endert, and S. Amigorena. 2004. Control of cross-presentation during dendritic cell maturation. Eur. J. Immunol. 34:398-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guermonprez, P., L. Saveanu, M. Kleijmeer, J. Davoust, P. van Endert, and S. Amigorena. 2003. ER-phagosome fusion defines an MHC class I cross-presentation compartment in dendritic cells. Nature 25:397-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gupta, R. K., and G. R. Siber. 1995. Adjuvants for human vaccine-current status, problems and future prospects. Vaccine 13:1263-1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haglund, K., I. Leiner, K. Kerksiek, L. Buonocore, E. Pamer, and J. K. Rose. 2002. Robust recall and long-term memory T-cell responses induced by prime-boost regimens with heterologous live viral vectors expressing human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag and Env proteins. J. Virol. 76:7506-7517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heeg, K., W. Kuon, and H. Wagner. 1991. Vaccination of class I major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-restricted murine CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes towards soluble antigens: immunostimulating-ovalbumin complexes enter the class I MHC-restricted antigen pathway and allow sensitization against the immunodominant peptide. Eur. J. Immunol. 21:1523-1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hotta, C., H. Fujimaki, M. Yoshinari, M. Nakazawa, and M. Minami. 2006. The delivery of an antigen from the endocytic compartment into the cytosol from cross-presentation is restricted to early immature dendritic cells. Immunology 117:97-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hou, S., L. Hyland, K. W. Ryan, A. Portner, and P. C. Doherty. 1994. Virus-specific CD8+ T cell memory determined by clonal burst size. Nature 369:652-654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Houde, M., S. Bertholet, E. Gagnon, S. Brunet, G. Goyette, A. Laplante, M. F. Princiotta, P. Thibault, D. Sacks, and M. Desjardins. 2003. Phagosomes are competent organelles for antigen cross-presentation. Nature 425:402-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang, A. Y., P. Golumbeck, M. Ahmadzadeh, E. Jaffee, D. Pardoll, and H. Levitsky. 1994. Role of bone marrow derived cells in presenting MHC class I-restricted tumor antigens. Science 264:961-965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Janssen, E. M., E. E. Lemmens, T. Wolfe, U. Christen, M. G. von Herrath, and S. P. Schoenberger. 2003. CD4+ T cells are required for secondary expansion and memory in CD8+ T lymphocytes. Nature 421:852-856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ke, Y., Y. Li, and J. A. Kapp. 1995. Ovalbumin injected with complete Freund's adjuvant stimulates cytolytic responses. Eur. J. Immunol. 25:549-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.La Gruta, N. L., K. Kedzierska, K. Pang, R. Webby, M. Davenport, W. Chen, S. J. Turner, and P. C. Doherty. 2006. A virus-specific CD8+ T cells immunodominance hierarchy determined by antigen dose and precursor frequencies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:994-999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li, M., G. M. Davey, R. M. Sutherland, C. Kurts, A. M. Lew, C. Hirst, F. R. Carbone, and W. R. Heath. 2001. Cell-associated ovalbumin is cross-presented much more efficiently than soluble ovalbumin in vivo. J. Immunol. 166:6099-6103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lindblad, E. B. 2004. Aluminium adjuvants—in retrospect and prospect. Vaccine 22:3658-3668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luthman, H., and G. Magnusson. 1983. High efficiency polyoma DNA transfection of chloroquine treated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 11:1295-1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lyons, A. B., and C. R. Parish. 1994. Determination of lymphocyte division by flow cytometry. J. Immunol. Methods 171:131-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morrison, L. A., A. E. Lukacher, V. L. Braciale, D. P. Fan, and T. J. Braciale. 1986. Differences in antigen presentation to MHC class I- and class II-restricted influenza virus-specific cytolytic T lymphocyte clones. J. Exp. Med. 163:903-921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murali-Krishna, K., J. D. Altman, M. Suresh, D. J. D. Sourdive, A. J. Zajac, J. D. Miller, J. Slansky, and R. Ahmed. 1998. Counting antigen-specific CD8 T cells: a reevaluation of bystander activation during viral infection. Immunity 8:177-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nelson, D., C. Bundell, and B. Robinson. 2000. In vivo cross-presentation of a soluble protein antigen: kinetics, distribution, and generation of effector CTL recognizing dominant and subdominant epitopes. J. Immunol. 165:6123-6132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Newman, M. J., J. Y. Wu, B. H. Gardner, K. J. Munroe, D. Leombruno, C. R. Kensil, and R. T. Coughlin. 1992. Saponin adjuvant induction of ovalbumin-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses. J. Immunol. 148:2357-2362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Norbury, C. C., L. J. Hewlett, A. R. Prescott, N. Shastri, and C. Watts. 1995. Class I MHC presentation of exogenous soluble antigen via macropinocytosis in bone marrow macrophages. Immunity 3:783-791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Norbury, C. C., B. J. Chambers, A. R. Prescott, H. G. Ljunggren, and C. Watts. 1997. Constitutive macropinocytosis allows TAP-dependent major histocompatibility complex class I presentation of exogenous soluble antigen by bone marrow-derived dendritic cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 27:280-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Norbury, C. C., S. Basta, K. B. Donohue, D. C. Tscharke, M. F. Princiotta, P. Berglund, J. Gibbs, J. R. Bennink, and J. W. Yewdell. 2004. CD8+ T cell cross-priming via transfer of proteasome substrates. Science 304:1318-1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prato, S., J. Fleming, C. W. Schmidt, G. Corradin, and J. A. Lopez. 2006. Cross-presentation of a human malaria CTL epitope is conformation dependent. Mol. Immunol. 43:2031-2036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodriguez, A., A. Regnault, M. Kleijmeer, P. Ricciardi-Castagnoli, and S. Amigorena. 1999. Selective transport of internalized antigens to the cytosol for MHC class I presentation in dendritic cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 1:362-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sant, A. J., and J. Miller. 1994. MHC class II antigen processing: biology of invariant chain. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 6:57-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Savina, A., C. Jancic, S. Hugues, P. Guermonprez, P. Vargas, I. Cruz Moura, A. M. Lennon-Dumenil, M. C. Seabra, G. Raposo, and S. Amigorena. 2006. NOX2 controls phagosomal pH to regulate antigen processing during cross presentation by dendritic cells. Cell 126:205-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schnorrer, P., G. M. N. Behrens, N. S. Wilson, J. L. Pooley, C. M. Smith, D. El-Sukkary, G. Davey, F. Kupresanin, M. Li, E. Maraskovsky, G. T. Belz, F. R. Carbone, K. Shortman, W. R. Heath, and J. A. Villadangos. 2006. The dominant role of CD8+ dendritic cells in cross-presentation is not dictated by antigen capture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:10729-10734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schultz, K. R., S. Bader, J. Paquet, and W. Li. 1995. Chloroquine treatment affects T-cell priming to minor histocompatibility antigens and graft-versus-host disease. Blood 86:4344-4352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shen, L., and K. L. Rock. 2004. Cellular protein is the source of cross-priming antigen in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:3035-3040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shurin, G. V., I. L. Tourkova, G. S. Chatta, G. Schmidt, S. Wei, J. Y. Djeu, and M. R. Shurin. 2005. Small Rho GTPases regulate antigen presentation in dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 174:3394-3400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sourdive, D. J. D., K. Murali-Krishna, J. D. Altman, A. J. Zajac, J. K. Whitmire, C. Pannetier, P. Kourilsky, B. Evavold, A. Sette, and R. Ahmed. 1998. Conserved T cell receptor repertoire in primary and memory CD8 T cell responses to an acute viral infection. J. Exp. Med. 188:71-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sun, J. C., and M. J. Bevan. 2003. Defective CD8 T cell memory following acute infection without CD4 T cell help. Science 300:339-342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Topham, D. T., M. R. Castrucci, F. S. Wingo, G. T. Belz, and P. C. Doherty. 2001. The role of antigen in the localization of naïve, acutely activated, and memory CD8+ T cells to the lung during influenza pneumonia. J. Immunol. 167:6983-6990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vremec, D., J. Pooley, H. Hochrein, L. Wu, and K. Shortman. 2000. CD4 and CD8 expression by dendritic cell subtypes in mouse thymus and spleen. J. Immunol. 164:2978-2986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Watts, C. 1997. Capture and processing of exogenous antigens for presentation on MHC molecules. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 15:821-850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wherry, E. J., V. Teichgraber, T. C. Becker, D. Masopust, S. M. Kaech, R. Antia, U. H. von Andrian, and R. Ahmed. 2003. Lineage relationship and protective immunity of memory CD8 T cell subsets. Nat. Immunol. 4:225-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wilson, N. S., D. El-Sukkary, G. T. Belz, C. M. Smith, R. J. Steptoe, W. R. Heath, K. Shortman, and J. A. Villadangos. 2003. Most lymphoid organ dendritic cell types are phenotypically and functionally immature. Blood 102:2187-2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wilson, N. S., G. M. N. Behrens, R. J. Lundie, C. M. Smith, J. Waithman, L. Young, S. P. Forehan, A. Mount, R. J. Steptoe, K. D. Shortman, T. F. de Koning-Ward, G. T. Belz, F. R. Carbone, B. S. Crabb, W. R. Heath, and J. A. Villadangos. 2006. Systemic activation of dendritic cells by Toll-like receptor ligands or malaria infection impairs cross-presentation and antiviral immunity. Nat. Immunol. 7:165-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wolkers, M. C., N. Brouwenstijn, A. H. Bakker, M. Toebes, and T. N. M. Schumacher. 2004. Antigen bias in T cell cross-priming. Science 304:1314-1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.York, I. A., and K. L. Rock. 1996. Antigen processing and presentation by class I major histocompatibility complex. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 14:369-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ziegler, H. K., and E. R. Unanue. 1982. Decrease in macrophage antigen catabolism caused by ammonia and chloroquine is associated with inhibition of antigen presentation to T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 79:175-178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]