Summary

Navigating axons respond to environmental guidance signals, but can also follow axons that have gone before—pioneer axons. Pioneers have been studied extensively in simple systems, but the role of axon-axon interactions remains largely unexplored in large vertebrate axon tracts, where cohorts of identical axons could potentially use isotypic interactions to guide each other through multiple choice points. Furthermore, the relative importance of axon-axon interactions compared to axon-autonomous receptor function has not been assessed. Here we test the role of axon-axon interactions in retinotectal development, by devising a technique to selectively remove or replace early-born retinal ganglion cells (RGCs). We find that early RGCs are both necessary and sufficient for later axons to exit the eye. Furthermore, introducing misrouted axons by transplantation reveals that guidance from eye to tectum relies heavily on interactions between axons, including both pioneer-follower and community effects. We conclude that axon-axon interactions and ligand-receptor signaling have coequal roles, cooperating to ensure the fidelity of axon guidance in developing vertebrate tracts.

Keywords: Robo2, astray, ath5, atoh7, morpholino, fasciculation, transplant, cell-autonomy, zebrafish

Introduction

To generate a functional nervous system, widely-separated groups of neurons must form appropriate connections. Each newborn neuron extends an axon tipped by a motile growth cone, which navigates through sequential “choice points” to eventually reach its target (Dickson, 2002; Guan and Rao, 2003; Tessier-Lavigne and Goodman, 1996). The growth cone has two potential sources of guidance information. First, it may fasciculate with “pioneer” axons—defined here as earlier-born axons that share its path—using cell-adhesion molecules. Second, it may sense secreted or cell-surface guidance ligands produced by other cells in the brain, acting at long or short range, respectively. Most recent work has focused on guidance ligands; genetic screens and biochemical purification strategies have identified many ligand/receptor pairs used by navigating growth cones (Dickson, 2002; Guan and Rao, 2003; Tessier-Lavigne and Goodman, 1996).

There is long-standing evidence, however, that pioneer-follower interactions can play necessary roles in guidance (Lopresti et al., 1973; Bate, 1976; Raper et al., 1983; Raper et al., 1984; Kuwada, 1986; Klose and Bentley, 1989; Ghosh et al., 1990; Pike et al., 1992; Hidalgo and Brand, 1997; Jhaveri and Rodrigues, 2002; Williams and Shepherd, 2002). In other cases, pioneers are not required (Keshishian and Bentley, 1983; Holt, 1984; Eisen et al., 1989; Cornel and Holt, 1992), or only facilitate followers’ guidance (Chitnis and Kuwada, 1991; Pike et al., 1992; Bak and Fraser, 2003). Nearly all of these studies were done in simple systems where a few pioneer axons could be identified, and where required roles for pioneers were tested by ablation. Furthermore, these pioneers were usually heterotypic: of a different neuronal type than the followers, with different origins and targets, so that they could only guide the followers through one leg of their journey. Thus it is not clear (1) whether the role of pioneers is generalizable to more complex systems; (2) what are the sufficient functions of pioneers, for instance if they take abnormal paths; or (3) what roles are usually played by isotypic interactions (between axons from the same neuronal type).

In vertebrates, most axon tracts are built on a large scale. They typically comprise thousands of axons, all with the same origin and target, and often develop over an extended period as new neurons are added. This raises the possibility that vertebrate axons could be guided by isotypic interactions, either between earlier and later axons (pioneer-follower interactions), or between axons that grow at the same time (community interactions). Since axons in the same tract share both origin and target, isotypic interactions could act at multiple choice points throughout their pathway. While there is often an unspoken assumption that vertebrate axons indeed use pioneers for guidance, there have been only a few direct experimental tests of this hypothesis (Holt, 1984; Eisen et al., 1989; Ghosh et al., 1990; Cornel and Holt, 1992; Bak and Fraser, 2003). Here we use the zebrafish retinotectal system to study this fundamental cellular mechanism in axon guidance. We first ask if isotypic pioneer-follower and community interactions are important in the development of a large vertebrate axon tract. We next use a pioneer replacement strategy to test whether pioneers are sufficient to affect followers, and to assess the relative importance of axon-axon interactions compared to guidance receptor signaling.

The retinotectal projection is one of the best-studied vertebrate tracts, whose formation has been studied extensively (Erskine and Herrera, 2007). Retinal ganglion cell (RGC) axons must navigate out of the eye, across the optic chiasm, and dorsally through the optic tract to reach the optic tectum. While retinal axons parallel the tract of the postoptic commissure (tPOC) after crossing the optic chiasm, they make at most fleeting contacts with tPOC axons (Burrill and Easter, 1995), and embryological manipulations that remove tPOC axons do not affect retinal axon guidance (Cornel and Holt, 1992). Thus, retinal axons do not require heterotypic pioneers. Despite the extensive retinotectal literature, there has been only one functional test of whether retinal pioneer axons might guide later retinal axons (i.e., through an isotypic interaction). In Xenopus, dorsocentral RGCs are the first to send out their axons. There was no effect on the guidance of later retinal axons when heterochronic transplants were used to delay the outgrowth of dorsocentral RGCs (Holt, 1984), suggesting that retinal pioneers are not required. Here we reexamine the role of retinal pioneers in guidance both within the eye and after exiting it. We use genetic and embryological manipulations both to remove early RGCs, and to replace them with cells lacking the Robo2 guidance receptor. We find that isotypic pioneers in fact play multiple roles during the formation of this archetypal vertebrate tract.

Materials and Methods

Transgenics

All fish were of the Tü or TL strains. The transgenic lines and mutant alleles used were: Tg(isl2b:GFP)zc7, Tg(isl2b:mCherry-CAAX)zc23 or Tg(isl2b:mCherry-CAAX)zc25 (both of similar brightness), Tg(brn3c:gap43-GFP)s356t (Xiao et al., 2005), and the null ast allele astti272z (Fricke et al., 2001). Since ast is homozygous adult viable, ast embryos were generated by incrossing homozygote parents. Embryos were raised at 28.5°C in 0.1 mM phenylthiourea and staged according to time postfertilization and morphology (Kimmel et al., 1995). Experimental procedures followed NIH guidelines and were approved by the University of Utah Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Morpholino injections

Lyophilized ath5MO (5′-TTCATGGCTCTTCAAAAAAGTCTCC-3′; antisense start codon underlined; Open Biosystems/Gene Tools) was solubilized in 1x Danieau’s buffer, and aliquotted at −20°C. Embryos from either isl2b:GFP/+ or isl2b:mCherry-CAAX/+ incrosses were collected at the one-cell stage, and a nominal volume of 1 nl MO was pressure-injected at the yolk/cell interface using a Picospritzer (Parker). MO was diluted to working concentrations with 0.1% phenol red as a marker dye, and the injected bolus measured using an eyepiece micrometer. All embryos for the dose response experiment of Figs. 1 and 2 were injected in the same session with a single pipette, counting pressure pulses to deliver different doses. Individual live embryos were repeatedly assayed for GFP expression in the retina using a fluorescent dissecting microscope, every 3 hours from 33–57 hpf. Repeating this experiment yielded essentially the same results, except for a shift attributable to different bolus size (data not shown).

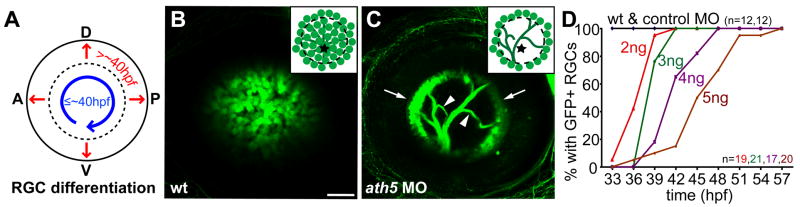

Figure 1.

ath5 MO blocks differentiation of early- but not late-born RGCs (A) Normally, early RGCs differentiate in a wave across central retina (blue arrow); late RGCs are then added centrifugally (red arrows). (B, C) 6 dpf isl2b:GFP, lateral views, anterior to left. Insets schematize cell bodies, axons, and optic nerve head (star). (B) WT eye shows GFP+ RGCs throughout central retina; axons are obscured by cell bodies. (C) A high dose of ath5MO blocks differentiation of early RGCs, but late RGCs still form (arrows). Without central RGCs, peripheral axons are visible (arrowheads). (D) Dose-response curve showing timing of RGC formation with different doses of ath5MO. In WT and with 3ng control MO, GFP+ RGCs appear by 33hpf. Increasing concentrations of ath5MO increasingly delay the appearance of the first RGCs. A, anterior; D, dorsal; P, posterior; V, ventral. Scale bar=50μm.

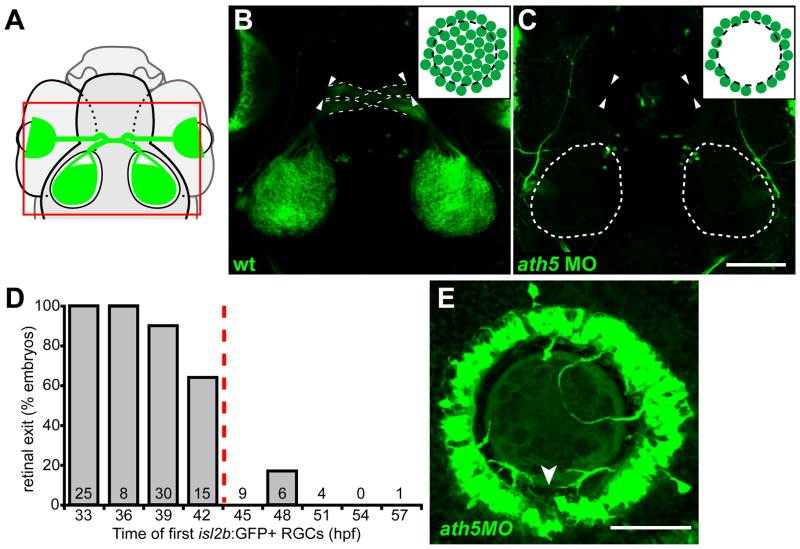

Figure 2.

Early RGCs are necessary for axons to exit eye. (A) Diagram showing field of view for B, C. (B, C) 5 dpf isl2b:GFP, confocal z-projections; dorsal views, anterior up. Insets diagram cell bodies in eye. (B) WT axons exit eye (arrowheads), project through the optic chiasm (dashed lines), and to the optic tecta. (C) With high dose of ath5 MO, axons do not exit eye (arrowheads) or innervate tectum (dotted outlines). (D) Retinal exit in dose-response experiment of Fig. 1D, plotting percentage of embryos in which axons exit the eye against the time at which their first isl2b:gfp-positive RGCs were born. When RGCs are born by 42hpf, axons usually exit the eye; when delayed after 42hpf, axons rarely exit. Number of embryos is indicated at base of each bar. (E) 72 hpf isl2b:GFP, confocal z-projection; dorsal up. In a high-dose ath5 morphant, axons from peripheral RGCs remain trapped in the RGC layer without entering the optic nerve. To better appreciate 3D structure, see volume reconstruction in Supplementary Movie 1. Arrowhead indicates the optic nerve head, stained by anti-Pax2 (not shown). Scale bar=100μm (A, B); 50 μm (D).

Cell transplants

Transplants were performed as described by Ho and Kane (1990). Briefly, 1-cell donor embryos were injected with 5% rhodamine dextran (10,000 MW) as a lineage marker; at 4 hpf, 20–50 cells were transplanted to the animal pole of host embryos, which were raised to 5 dpf at 28.5°C. For Fig. 4, donors were from an isl2b:mCherryCAAX/+ incross, while hosts were isl2b:GFP embryos injected with 5ng ath5MO.

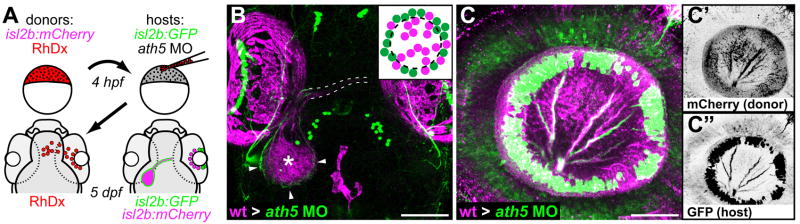

Figure 4.

Transplanted WT central RGCs rescue retinal exit in ath5 morphants. (A) Blastula transplants from isl2b:mCherry donors resupply ath5 morphant hosts, labeled with isl2b:gfp, with early RGCs. RhDx, rhodamine-dextran cell lineage marker. (B) Resupplied WT RGCs and axons (magenta) are sufficient to rescue host axons in morphants (green). Pigment cell autofluorescence is seen around eyes and at dorsal midline (magenta). Retinal axons project across chiasm (dashed lines); donor axons terminate in central tectum (asterisk), while host axons terminate in peripheral tectum (arrowheads). Dorsal view, 5 dpf. (C) Lateral view of 5 dpf eye showing peripheral host axons (green) fasciculating with resupplied WT axons (magenta). (C′) donor and (C″) host axons, reverse contrast. Scale bar=100μm (B); 50μm (C).

In addition to RGCs, isl2b:gfp labels small clusters of neurons in the forebrain and dorsal diencephalon that make it difficult to unambiguously identify misrouted retinal axons. Therefore, axon-axon interaction experiments used the Tg(brn3c:gap43-GFP)s356t transgene, which labels a subpopulation of ~50% of RGCs without confounding brain expression (Xiao et al., 2005). For Fig. 5, donors were from a brn3c:GFP/+ or ast; brn3c:GFP/+ incross, while hosts were WT or ast. For Fig. 6, donors were nontransgenic, while hosts were brn3c:GFP embryos injected with 5ng ath5MO.

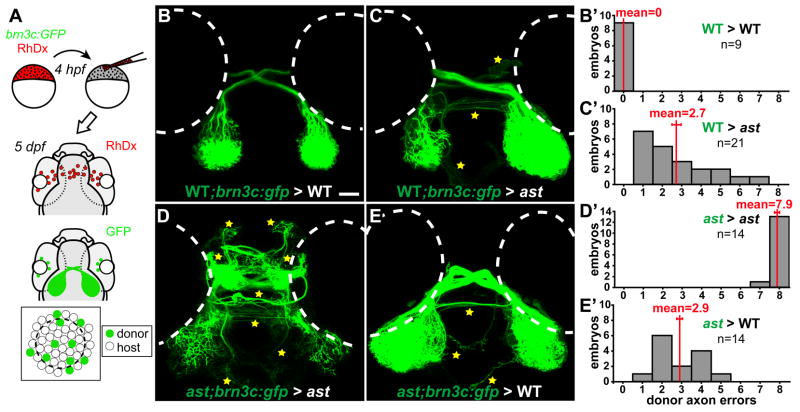

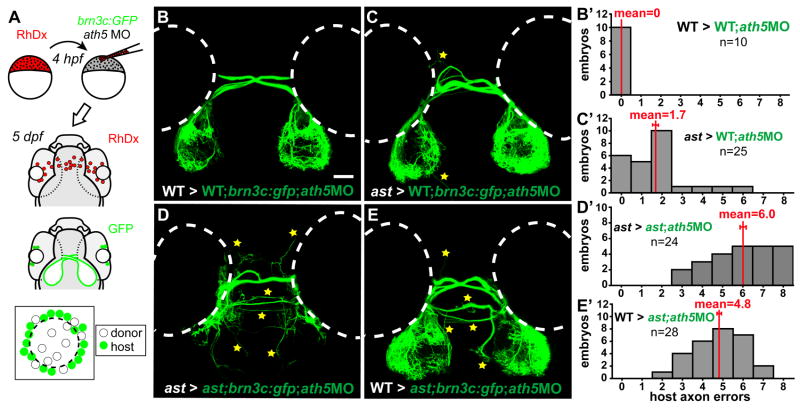

Figure 5.

Axon-axon interactions strongly influence retinotectal pathfinding. (A) Transplants yield GFP-expressing donor RGCs in host eyes. (B–E) Dorsal views, 5dpf, rostral up. Donor axons labeled with brn3c:GFP; pathfinding errors indicated by yellow stars. (B′–E′) Error quantitation. (B, B′) In WT>WT transplants, donor axons pathfind perfectly. (C, C′) In contrast, when transplanted into ast hosts, WT axons make significantly more errors. (D, D′) As expected, ast donor axons make many errors in ast hosts. (E, E′) However, when transplanted into WT hosts, ast axons make significantly fewer errors. Scale bar=50 μm.

Figure 6.

Pioneer axons influence pathfinding of follower axons. (A) Transplants resupply early RGCs to brn3c:GFP hosts injected with ath5 MO. (B–E) Dorsal views at 5dpf, rostral up. Host axons terminate peripherally on the tectum; errors indicated by stars. (B′–E′) Error quantitation. (B, B′) In WT>WT;ath5 MO transplants, host follower axons pathfind normally. (C, C′) When pioneers are replaced with ast cells, WT follower axons make significantly more mistakes. (D, D′) In ast > ast;ath5MO transplants, host follower axons make many errors. (E, E′) When pioneers are replaced with WT cells, follower ast axons make fewer errors but are not completely rescued. Scale bar=50 μm.

Immunofluorescence and staining

For whole-mount immunostaining, isl2b:GFP-positive larvae were fixed at 5 or 6dpf in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS overnight at 4°C, washed in PBST (PBS with 0.1% Tween-20), dehydrated through an MeOH series, stored at −20°C for >12 hours, rehydrated, washed in PBST, permeabilized with 0.1% collagenase for 1 hour at room temperature, then incubated in the following primary antibodies overnight at 4°C: rabbit anti-GFP (1:400; Invitrogen A11122), mouse anti-GFP (1:200; Chemicon MAB3580), rabbit anti-DsRed (1:200; Clontech 632496), mouse anti-parvalbumin (1:400; Chemicon MAB1572) or affinity-purified rabbit anti-Pax2a (1:300; gift of A. Picker). Larvae were then washed in PBST, incubated in goat anti-rabbit Alexa 488 (1:200; Invitrogen A11008), goat anti-mouse Cy3 (1:200; Jackson Immunoresearch 115-165-003) goat anti-mouse Alexa 488 (1:200; Molecular Probes A-11029), or goat anti-rabbit Cy3 (1:200; Jackson Immunoresearch 111-165-003), then stained in Hoechst 33342 (1:15,000; Molecular Probes H-3570) or ToPro-3 (1:1000; Molecular Probes T3605) for 30 min at room temperature. Wholemount in situ hybridization for netrin1a was performed as described previously (Wilson et al., 2006). For sectioning, embryos were dehydrated in MeOH, infiltrated at 4°C in 1:1 Immuno-Bed:MeOH for 30 min then 100% Immuno-Bed overnight, oriented and embedded in 20:1 Immuno-Bed:Immuno-Bed Solution B (EMS 14260-04), and sectioned at 8rm on a Reichert-Jung 2050 Supercut microtome with a glass knife.

Fluorescent microscopy

GFP expression was initially assayed using an Olympus SZX-12 fluorescent dissecting microscope with a 1.6X objective. For more detailed analysis of GFP expression and the retinotectal projection, live 5dpf larvae were mounted in 1.5% low-melt agarose with tricaine and imaged with an Olympus confocal microscope. Images were processed using Adobe Photoshop CS2. The relatively small number of GFP+ axons in cell transplant experiments are obscured by skin autofluorescence when viewed as confocal projections. Therefore, for Figures 6 and 7, we used ImageJ (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij; developed by Wayne Rasband, NIH) and Photoshop to manually edit each z-slice and remove autofluorescence and background fluorescence, taking care always to spare nearby axons (Supplementary Figure 3). Raw confocal stack data is available upon request. For cell counting, 42 hpf isl2b:gfp eyes were fixed, labeled with ToPro-3, dissected, mounted in 80% glycerol and imaged with an Olympus confocal microscope. ToPro3+, GFP+ nuclei were counted by manual inspection of each z-slice in the stack, and movies were made with Volocity software.

Phenotype Quantification

In ast, eight retinal pathfinding errors are commonly seen: midline crossing in the habenular and posterior commissures, and left- and right-sided projections to the telencephalon, diencephalon, and ventral hindbrain (Supplementary Figure 2). For each chimeric larva, the presence (1 or more axons) or absence of each error was scored at 5–6 dpf by an observer blinded to genotypes, using ImageJ to examine the entire (unedited) confocal z-stack. Scores were compared by the Mann-Whitney U test using Instat 3 (GraphPad).

Results

To test the role of pioneer neurons, we devised a method to selectively remove early-born RGCs. These cells’ differentiation starts ventroanteriorly at 27–28 hours postfertilization (hpf), spreading circumferentially to fill the central retina by ~40 hpf (Hu and Easter, 1999; Masai et al., 2005). After this, new RGCs are added in successive peripheral rings (Fig. 1A). The RGC-specific transgene Tg(isl2b:GFP)zc7 turns on by 30hpf in ventroanterior retina, reliably labeling all or the vast majority of RGCs (Fig. 1B; Pittman & Chien, in preparation). To remove early RGCs, we used a translation-blocking antisense morpholino oligonucleotide (ath5MO) to knock down function of ath5 (formally, atoh7—Zebrafish Information Network), a bHLH transcription factor expressed specifically in the eye and required cell-autonomously for RGC differentiation (Kay et al., 2005). ath5 mutants completely lack RGCs (Brown et al., 2001; Kay et al., 2001), and their RGC progenitors seem instead to take on primarily bipolar cell fates (Kay et al., 2001). We reasoned that ath5MO should have a similar, but transient, effect since morpholinos’ efficacy wanes as their concentration is diluted by embryonic growth (Nasevicius & Ekker, 2000). Indeed, we found that ath5MO causes a loss of early-born central RGCs, but allows later-born peripheral RGCs to differentiate (Fig. 1C). In isl2b:GFP embryos injected with high-dose (5 ng) ath5MO (Fig. 1C; Fig. 2E; Supplementary Figure 1), RGCs were found exclusively in peripheral retina at 6 days postfertilization (dpf)—over 4 days after central RGCs normally form—showing that differentiation is prevented rather than merely delayed. We next injected an ath5MO dose series, monitoring RGC differentiation in live embryos from 33 to 57 hpf. In control embryos, GFP+ RGCs were always present by 33hpf. With successively higher doses, the first RGCs appeared successively later, until with 5ng ath5MO, RGCs did not appear until ≥42hpf in 90% of embryos (Fig. 1D). Thus, varying the dose of ath5MO controls the time at which the first RGCs differentiate.

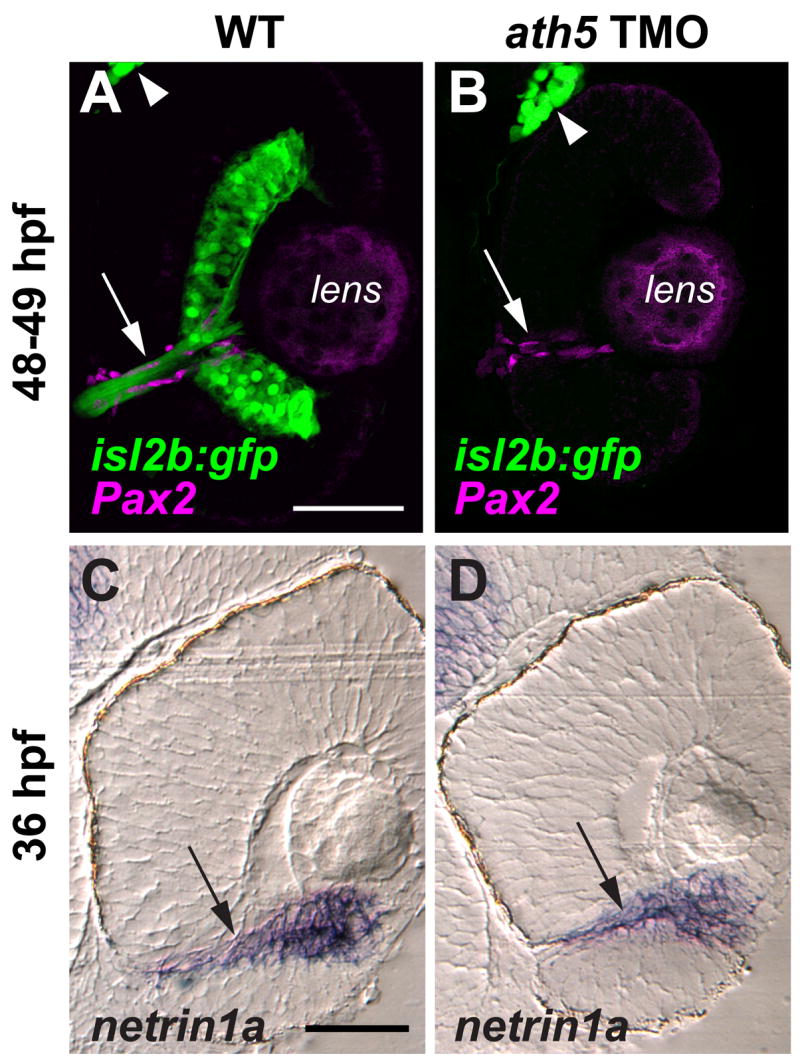

We then tested whether removing early-born RGCs affects the pathfinding of later axons (Fig. 2). In uninjected controls, the retinotectal projection is mature at 5 dpf, with both optic tecta strongly innervated (Fig. 2B; n=12/12). However, when central RGCs were removed by injecting 5ng ath5MO, axons of late-born RGCs failed to exit from the eye into the brain (Fig. 2C; n=19/20). We hypothesized that this failure might be related to the time of first RGC differentiation. Therefore we injected isl2b:GFP embryos with 2–5 ng ath5MO (Fig. 1D), plotting retinal exit at 5 dpf against the time of first RGC differentiation (Fig. 2D). Axons projected from eye to tectum in 100% of control larvae (uninjected, n=12; 3 ng control MO, n=12) and in 83% (45/54) of those morphants (MO-injected embryos) whose first RGCs were born by 42hpf. In contrast, axons exited the eye in only 5% (1/20) of morphants whose first RGCs were born after 42hpf. Instead, axons from peripheral RGCs grew within the RGC layer of the eye without entering the intraretinal portion of the optic nerve (Fig. 2E, Supplemental Movie 1, Supplemental Figure 1). A physical barrier is not likely the cause: ath5 morphants have normal retinal lamination, and the presumptive optic nerve can still be distinguished (Supplementary Figure 1). To test for changes in the environment of the presumptive optic nerve, we stained for Pax2, which labels the surrounding primitive glia (Macdonald et al., 1997), and for netrin1a, a marker of the optic nerve and optic nerve head (Fig. 3). Both markers appeared normal in ath5 morphants. Taken together, these results strongly suggest that an isotypic pioneer-follower interaction is required for later RGCs’ axons to exit the eye, and further that there is a critical period before 42 hpf.

Figure 3.

ath5 MO does not appear to affect the molecular and cellular environment of the optic nerve head or the intraretinal optic nerve. Coronal sections through 48–49 hpf isl2b:GFP (A, B) and 36 hpf non-transgenic (C, D) eyes, from either uninjected embryos (A, C) or embryos injected with high dose ath5 TMO (B, D). (A, B) Pax2a antibody staining (magenta) labels presumptive glial cells which line the intraretinal portion of the optic nerve (arrows) in both WT (A) and ath5 morphants (B). RGCs and their axons (green) are present in WT (A), but not in ath5 morphants (B). The trigeminal ganglion (arrowheads) is also labeled by isl2b:gfp and serves as a staining control. (C, D) In situ hybridization shows that netrin1a expression (arrows) surrounds the optic nerve and optic nerve head in WT (C), and is unchanged in ath5 morphants (D). Scale bars, 50 μm.

We next tested whether this pioneer-follower interaction is sufficient as well as necessary, by resupplying RGCs to ath5 morphants. We targeted the presumptive eye field in blastula-stage transplants from isl2b:mCherry-CAAX donors into isl2b:GFP hosts injected with high-dose ath5MO (Fig. 4A). Since ath5 acts cell-autonomously (Kay et al., 2005), we expected that donor (non-morphant) RGCs would differentiate without affecting host cells. Indeed, while host RGCs were still restricted to peripheral retina, donor RGCs were found in central retina, and usually sent axons out of the eye to the tectum (Fig. 4B, C). Of 32 eyes with mCherry+ donor axons reaching the tectum, 24 (75%) showed rescue of retinal exit, with GFP+ host axons reaching the tectum (Fig. 4B). Retinotectal topography appeared unaffected: donor axons from central retina projected to central tectum, and host axons from peripheral retina projected to peripheral tectum (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, imaging within chimeric eyes showed that late-born host axons appeared to fasciculate with donor axons (Fig. 4C–C″). Therefore, early RGCs are both necessary and sufficient to guide later axons out of the eye.

In a second series of experiments, we tested whether, after retinal axons exit the eye, interactions between them might affect guidance to the tectum. To do this, we used cell transplants to mix retinal axons of different intrinsic pathfinding potential. In astray (ast) mutants, retinal axons make drastic pathfinding errors because they lack the Slit receptor, Robo2 (Fricke et al., 2001). Transplantation of eye primordia yields strictly eye-autonomous pathfinding defects, showing that Robo2 is required in the eye and not the brain (Fricke et al., 2001). Here, we performed cell transplants from WT or ast donors labeled with the RGC-specific transgene brn3c:GFP (Xiao et al., 2005) into nontransgenic WT or ast hosts (Fig. 5A). We then assayed the pathfinding of GFP-positive axons (which bear the donor genotype), quantitating the results by counting the number of classes of pathfinding errors made by GFP-positive donor retinal axons, yielding a score for each host from 0 for WT to 8 for strong ast (Supplementary Figure 2; see Materials and Methods).

As expected, WT donor axons in WT hosts made no pathfinding errors (Fig. 5B, B′; 0.0±0.0 errors, mean ± s.e.m.). Surprisingly, WT axons transplanted to ast hosts always made errors, which occurred at several different positions (Fig. 5C, C′; 2.71±0.40 errors, p<0.0001). Presumably, despite expressing functional Robo2, they were misguided by neighbors that lacked Robo2. Donor ast axons made many errors in ast hosts (Fig. 5D, D′; 7.93±0.07 errors), similar to axons in nontransplanted ast embryos (Supplementary Figure 2). In contrast, ast axons transplanted into WT embryos navigated far better (Fig. 5E, E′; 2.86±0.31 errors, p<0.0001). Thus, even lacking functional Robo2, their pathfinding behavior was significantly rescued by WT neighbors. These effects are not transgene-dependent: using isl2b:GFP instead of brn3c:GFP yielded qualitatively similar results (data not shown). Strikingly, then, Robo2 acts nonautonomously in cell transplants, unlike its autonomous behavior in eye transplants (Fricke et al., 2001). As a receptor, Robo2’s direct effects must take place in the growth cone that expresses it, but this does not mean that indirect effects cannot affect other axons. The strong effect of the host axons’ genotype on donor axon behavior shows that despite the clear importance of Slit-Robo signaling, its role in individual axons can be overridden by axon-axon interactions.

Is this a pioneer-follower effect? Since these chimerae contained far more host than donor cells, the host genotype could be affecting donor axon behavior because most pioneer axons are likely to be host-derived. If so, replacing pioneer RGCs with cells of a different genotype should alter pathfinding by later axons. We tested this prediction by injecting high-dose ath5MO into brn3c:GFP hosts to remove all early RGCs, replacing the pioneer RGCs using transplants from nontransgenic donor embryos, then at 5 dpf assaying the pathfinding of GFP-positive axons, which are host-derived and therefore “follower” axons (Fig. 6A). WT followers made no errors when transplanted pioneers were WT (Fig. 6B, B′; 0.0±0.0 errors). However, when pioneers were replaced with ast cells, WT followers made more errors (Fig. 6C, C′; 1.72±0.31 errors, p<.002). Thus, misguided pioneers indeed influence WT followers. As expected, ast followers made many errors when pioneers were ast (Fig. 6D, D′; 5.96±0.33 errors). When pioneers were replaced with WT cells, ast follower axons made fewer errors (Fig. 6E, E′; 4.79±0.24 errors, p<0.01). Thus, follower axons’ pathfinding is partially influenced by the pioneers’ genotype, although clearly the followers’ genotype remains the predominant influence.

Discussion

We have shown that early-born RGCs are both necessary and sufficient for retinal axons to exit the eye. This is a somewhat surprising result in light of an elegant study in Xenopus (Holt, 1984), which did not find an important role for retinal pioneers. We believe the difference derives from our ability to use ath5MO injection to completely prevent the development of all central RGCs. In contrast, the heterochronic transplants used in the Xenopus study only affected the dorsal half of central retina (the source of pioneers in Xenopus), and furthermore only delayed the development of retinal pioneers by 9–20 hours, rather than removing them entirely. A previous study in zebrafish had proposed that a small group (<10) of early retinal growth cones were pioneers based on their significant separation from the next growth cones to follow (Stuermer, 1988). It is clear from our ath5 morpholino injections that these few growth cones are not functionally pioneers, in the sense of being necessary for later axons’ guidance. Instead, we find that far more cells must be removed to prevent retinal exit: the RGCs born by 42 hpf, the critical stage (Fig. 1), number about 600 (Supplemental Movies 2, 3). This is strikingly different from invertebrate systems where ablation of a few pioneers is sufficient to perturb follower axons.

After retinal exit, our transplant experiments show that isotypic interactions between retinal axons are important for three further choice points that require Robo2 function (Fricke et al., 2001; Hutson and Chien, 2002; M. Hardy and C.-B.C., unpublished data). Misrouting in the optic chiasm leads to chiasm defasciculation (Fig. 6C); misrouting in the ventral optic tract leads to telencephalic or ventral hindbrain projections (Figs. 5C and 6C); and misrouting in the dorsal optic tract leads to aberrant crossing in the habenular or posterior commissures (Fig. 5C). At all three choice points, mutant axons can lead wildtype neighbors into error. Thus, axon-axon interactions function throughout the entire course of the retinotectal projection.

Several questions remain for future studies on axon-axon interactions. What distinguishes pioneers from followers? We know of no molecular markers that distinguish these RGC populations—for instance, they both express robo2 (Campbell et al., 2007), so the only difference may be the time and position of their birth. How do pioneers interact with followers within the eye? Most simply, later axons may fasciculate with early axons, as seen in Fig. 4C–C′; future experiments will test whether disrupting cell adhesion molecules leads to axon guidance errors within the retina, as in other vertebrates (Brittis et al., 1995; Leppert et al., 1999; Ott et al., 1998; Zelina et al., 2005). However, we cannot formally exclude other possibilities. For instance, early RGC cell bodies might secrete an attractant that draws later axons to the optic nerve head. Interestingly, WT>ath5 morphant transplants in which host axons remained trapped within the eye tended to have fewer donor axons on the tectum (data not shown), presumably reflecting fewer donor RGCs, which might provide an insufficient level of attraction. What underlies the apparent critical period before 42 hpf? Both timing and spacing are possible explanations. Ligands implicated in retinal exit (Birgbauer et al., 2000; Deiner et al., 1997; Kay et al., 2005; Kolpak et al., 2005; Li et al., 2005; Thompson et al., 2006) or their receptors, might be expressed only transiently during this period, so that RGCs born after 42 hpf would lack appropriate exit signals. Alternately, early-born RGCs may be close enough to find the optic nerve head, while later RGCs are simply too far away to sense it.

While most pioneer experiments have studied heterotypic axon interactions, there have been a few studies of isotypic interactions. In grasshopper, Myers and Bastiani (1993) found that the growth cone of the identified Q1 neuron interacts strongly with its contralateral homolog, and that ablation of one Q1 often leads to midline stalling of the other Q1’s growth cone. In the zebrafish, Bak and Fraser (2003) found that pioneer and follower growth cones in the postoptic commissure (POC) display characteristic morphology and kinetics (spread/slow and narrow/fast, respectively). After laser ablation of pioneer growth cones, followers appeared to take their place and behave like pioneers. However, POC pioneer ablation did not have any effect on the pathfinding of follower axons, and indeed we do not know of previous studies in vertebrates showing guidance by isotypic pioneers.

Here, we found that isotypic interactions after retinal exit help to guide retinal axons to the tectum. We were able to test the role of axon-axon interactions in a new way: by replacing rather than ablating RGCs, we tested sufficiency rather than necessity. Previous studies on pioneers found that their ablation prevents normal pathfinding by followers (e.g., Raper et al., 1983; Klose and Bentley, 1989; Pike et al., 1992; Whitlock & Westerfield, 1998); here, we used zebrafish transplants to test how misrouted mutant axons affect WT axons, and vice versa. We found that ast host axons can misroute WT donor axons, while WT host axons rescue ast donors to a large degree. This allowed us to compare the relative importance of different guidance mechanisms; we conclude that axon-axon interactions can be just as important as cell-autonomous Slit-Robo signaling. As well as showing a significant role for pioneer-follower interactions, our data suggest an even more important role for peer interactions between late retinal axons. An ast host axon in a WT>ast;ath5MO transplant (Fig. 6E, E′) misroutes more often than an ast donor axon in an ast>WT transplant (Fig. 5E, E′), perhaps because a larger fraction of RGCs are ast in the former case. What might distinguish pioneer-follower from peer-peer interactions? We do not necessarily expect different molecular interactions, but instead, differences in temporal and spatial proximity. Peers grow out at the same time, while peripheral followers grow out significantly later than pioneers. New retinal axons grow at the surface of the brain, so that pioneers are gradually buried underneath. Thus, while peers can interact directly, late followers will contact pioneers only indirectly, with several degrees of separation.

Our results are complemented by a recent study (Gosse et al., 2008) which showed that even a single RGC transplanted into lakritz/ath5 mutant hosts can sometimes navigate successfully to the tectum. Successful cases of tectal innervation showed a bias for central RGCs; furthermore, axons of single RGCs transplanted to peripheral retina often remained trapped within the eye. Tectal innervation appeared to be a rare event, as a large number (~5000) of transplants had to be performed; in similar experiments transplanting a few RGCs into lakritz or ath5 morphants, we also find that axons rarely reach the tectum (AJP and CBC, unpublished data). Overall, these data are consistent with our model that a large population of central RGCs are required for peripheral axons to exit the retina.

Our transplant paradigms create artificial situations in which axon-axon interactions are at war with ligand-receptor signals. For instance, a WT axon surrounded by ast axons may be shown the correct path by signals from the brain, but tugged off-course by its neighbors. During normal retinotectal development, in contrast, all axons are WT. Not only does every axon recognize the correct path to its target, but so do all its predecessors and neighbors. Therefore, signals from both outside the tract (guidance ligands) and within (axon-axon interactions) should act in coordination to produce the highly stereotyped, precise formation of this vertebrate axon tract. Since interaction (fasciculation) between isotypic axons is widely observed, we propose that this coordinated strategy is likely used throughout the development of complex vertebrate nervous systems.

Finally, we point out significant implications for the interpretation of mutant axon guidance phenotypes. For instance, imagine a tract that uses two guidance receptors, A and B, to sense partially redundant sets of guidance signals. Suppose that in the absence of fasciculation, knockout of A would cause 30% of the axons to misroute, while knockout of B would cause 10% errors. Since most axons still navigate correctly, axon-axon interactions might in fact reduce the A mutant phenotype to 10%, and the B mutant phenotype to undetectable levels. Thus, genetic redundancy may act not only at the level of single axons, but also at the level of entire tracts.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. ath5 MO does not grossly affect the lamination, position of presumptive optic nerve, or neurogenesis of non-RGCs in the retina. Coronal sections through 6dpf isl2b:GFP eyes after double-staining for GFP (B, E, H) and parvalbumin (Pv; C, F, I). (AC) Uninjected WT; (D–F) larva injected with control MO; (G–I) larva injected with high dose of ath5 TMO. (A′–I′) High-power views of A–I (see boxed areas in A, D, G). (A, D, G) DIC images show that retinal lamination is not affected in ath5 morphants, with the exception of a severely reduced RGC layer. (A′, D′, G′) The location of the presumptive optic nerve (on) and optic nerve head (onh, arrows), as well as a break in the RPE that represents the normal exit point for retinal axons, are clearly identifiable in ath5 morphants. (B, E, H) In controls, isl2b:GFP staining shows RGCs throughout the entire RGC layer (rgc, arrows) and their axons exiting the eye in the optic nerve (on, arrowhead). However, in ath5 morphants (H), central RGCs do not differentiate, although later-born RGCs in the periphery differentiate normally (arrow). In addition, no axons exit the eye (open arrowhead). Staining in central retina represents axons from peripheral RGCs (open arrow). GFP+ photoreceptors labeled by isl2b:gfp differentiate normally in ath5 morphants (B, E, H; small arrows). (C, F, I) Differentiation of Pv+ amacrine cells in the inner nuclear layer (a, arrows) and displaced amacrine cells in the RGC layer (da, arrowheads) appears unaffected in ath5 morphants. Scale bar, 100μm.

Supplementary Figure 2. Eight-point scoring system used to quantify retinal axon errors. Dorsal views of retinotectal projection of 5dpf isl2b:gfp WT and ast larvae. (A) In WT embryos, retinal axons always pathfind to the tectum, and errors are almost never seen. (B) In ast null mutants, eight classes of errors are commonly seen, including midline crossing at the habenular and posterior commissures, and projections to the left and right telencephalon, diencephalon, ventral hindbrain (stars). Counting the classes of errors made by misguided axons in each larva yields an error score between 0 and 8.

Supplementary Figure 3. Background removal procedure used for transplant images. Dorsal views of projections made by donor axons in 5 dpf host larvae, control transplants. (A, B) Maximum-intensity z-projections of unedited confocal stack in WT>WT (A) and ast>ast (B) transplants. Autofluorescence in skin, superficial to axons, partially obscures the retinal projection. (A′, B′) Confocal projections shown after removing autofluorescence slice-by-slice by manual editing in ImageJ and Adobe Photoshop. Retinal axons are unaffected, but can be seen more clearly in the absence of skin fluorescence. stars indicate errors (always counted in unedited confocal stacks); dotted outlines show eye positions. All transplant images in Figs. 5 and 6 were processed in this manner.

Supplementary Movie 1. Volume reconstruction of Figure 2E’s 72 hpf isl2b:gfp ath5 morphant eye. GFP (green) labels RGCs; lens autofluorescence has been removed by manual editing of the confocal stack. In the initial frame, dorsal is up, anterior right, medial (i.e., the back of the eye) towards the viewer. The reconstruction is rotated first around the dorsoventral axis, then the anteroposterior axis. Axons are seen within the RGC layer, but do not exit the eye. See Fig. 2E for scale bar and other annotation.

Supplementary Movie 2. Confocal imaging of a 42 hpf isl2b:gfp eye, stained with ToPro3 to label nuclei and dissected away from the embryo. GFP (green) labels RGCs, while ToPro3 (magenta) labels all nuclei. Dorsal is up, anterior is right. The movie starts medially and progresses laterally. The optic nerve is seen exiting the eye, and can be traced back to the RGCs. At ~40% through the movie, a single nonretinal GFP+ neuron (presumably from the trigeminal ganglion) can be seen at the upper right. 97 serial sections spaced 1.6 μm apart; voxel size 0.5 × 0.5 × 1.6 μm. This eye had 553 RGCs (GFP+, ToPro3+ nuclei); 3 eyes from different 42 hpf embryos gave a mean of 625±92 (s.d.) RGCs.

Supplementary Movie 3. Volume reconstruction of the 42 hpf isl2b:gfp eye, stained with ToPro3, from Supplementary Movie 2. GFP (green) labels RGCs, while ToPro3 (magenta) labels all nuclei. Orientation of initial frame: dorsal up, anterior left (reversed left-right from Supplementary Movie 2). A single nonretinal GFP+ neuron (presumably from the trigeminal ganglion) can be seen.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Chien lab for discussions, Jude Rosenthal for technical assistance, Michael Bastiani and Richard Dorsky for comments on the manuscript, Tong Xiao and Herwig Baier for the brn3c:gfp line, Alexander Picker for anti-Pax2, and Hideo Otsuna for help with cell counts and 3D visualization. This work was supported by grants from the NIH/NEI and the University of Utah Research Foundation to C.-B.C.

References

- Bak M, Fraser SE. Axon fasciculation and differences in midline kinetics between pioneer and follower axons within commissural fascicles. Development. 2003;130:4999–5008. doi: 10.1242/dev.00713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bate CM. Pioneer neurones in an insect embryo. Nature. 1976;260:54–6. doi: 10.1038/260054a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birgbauer E, Cowan CA, Sretavan DW, Henkemeyer M. Kinase independent function of EphB receptors in retinal axon pathfinding to the optic disc from dorsal but not ventral retina. Development. 2000;127:1231–41. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.6.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brittis PA, Lemmon V, Rutishauser U, Silver J. Unique changes of ganglion cell growth cone behavior following cell adhesion molecule perturbations: a time-lapse study of the living retina. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1995;6:433–49. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1995.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown NL, Patel S, Brzezinski J, Glaser T. Math5 is required for retinal ganglion cell and optic nerve formation. Development. 2001;128:2497–508. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.13.2497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrill JD, Easter SS., Jr The first retinal axons and their microenvironment in zebrafish: cryptic pioneers and the pretract. J Neurosci. 1995;15:2935–47. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-04-02935.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DS, Stringham SA, Timm A, Xiao T, Law MY, Baier H, Nonet ML, Chien CB. Slit1a inhibits retinal ganglion cell arborization and synaptogenesis via Robo2-dependent and -independent pathways. Neuron. 2007;55:231–45. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitnis AB, Kuwada JY. Elimination of a brain tract increases errors in pathfinding by follower growth cones in the zebrafish embryo. Neuron. 1991;7:277–85. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90266-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornel E, Holt C. Precocious pathfinding: retinal axons can navigate in an axonless brain. Neuron. 1992;9:1001–11. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90061-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deiner MS, Kennedy TE, Fazeli A, Serafini T, Tessier-Lavigne M, Sretavan DW. Netrin-1 and DCC mediate axon guidance locally at the optic disc: loss of function leads to optic nerve hypoplasia. Neuron. 1997;19:575–89. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80373-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson BJ. Molecular mechanisms of axon guidance. Science. 2002;298:1959–64. doi: 10.1126/science.1072165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen JS, Pike SH, Debu B. The growth cones of identified motoneurons in embryonic zebrafish select appropriate pathways in the absence of specific cellular interactions. Neuron. 1989;2:1097–104. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90234-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erskine L, Herrera E. The retinal ganglion cell axon’s journey: insights into molecular mechanisms of axon guidance. Dev Biol. 2007;308:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricke C, Lee JS, Geiger-Rudolph S, Bonhoeffer F, Chien CB. astray, a zebrafish roundabout homolog required for retinal axon guidance. Science. 2001;292:507–10. doi: 10.1126/science.1059496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A, Antonini A, McConnell SK, Shatz CJ. Requirement for subplate neurons in the formation of thalamocortical connections. Nature. 1990;347:179–81. doi: 10.1038/347179a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosse NJ, Nevin LM, Baier H. Retinotopic order in the absence of axon competition. Nature. 2008;452:892–5. doi: 10.1038/nature06816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan KL, Rao Y. Signalling mechanisms mediating neuronal responses to guidance cues. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:941–56. doi: 10.1038/nrn1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo A, Brand AH. Targeted neuronal ablation: the role of pioneer neurons in guidance and fasciculation in the CNS of Drosophila. Development. 1997;124:3253–62. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.17.3253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho RK, Kane DA. Cell-autonomous action of zebrafish spt-1 mutation in specific mesodermal precursors. Nature. 1990;348:728–30. doi: 10.1038/348728a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt CE. Does timing of axon outgrowth influence initial retinotectal topography in Xenopus? J Neurosci. 1984;4:1130–52. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-04-01130.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu M, Easter SS. Retinal neurogenesis: the formation of the initial central patch of postmitotic cells. Dev Biol. 1999;207:309–21. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutson LD, Chien CB. astray/robo2 is required for guidance and error correction in zebrafish retinal axons. Neuron. 2002;33:205–217. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00579-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jhaveri D, Rodrigues V. Sensory neurons of the Atonal lineage pioneer the formation of glomeruli within the adult Drosophila olfactory lobe. Development. 2002;129:1251–60. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.5.1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay JN, Finger-Baier KC, Roeser T, Staub W, Baier H. Retinal ganglion cell genesis requires lakritz, a Zebrafish atonal Homolog. Neuron. 2001;30:725–36. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00312-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay JN, Link BA, Baier H. Staggered cell-intrinsic timing of ath5 expression underlies the wave of ganglion cell neurogenesis in the zebrafish retina. Development. 2005;132:2573–85. doi: 10.1242/dev.01831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshishian H, Bentley D. Embryogenesis of peripheral nerve pathways in grasshopper legs. III. Development without pioneer neurons. Dev Biol. 1983;96:116–24. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90316-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel CB, Ballard WW, Kimmel SR, Ullmann B, Schilling TF. Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 1995;203:253–310. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klose M, Bentley D. Transient pioneer neurons are essential for formation of an embryonic peripheral nerve. Science. 1989;245:982–4. doi: 10.1126/science.2772651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolpak A, Zhang J, Bao ZZ. Sonic hedgehog has a dual effect on the growth of retinal ganglion axons depending on its concentration. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3432–41. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4938-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwada JY. Cell recognition by neuronal growth cones in a simple vertebrate embryo. Science. 1986;233:740–6. doi: 10.1126/science.3738507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppert CA, Diekmann H, Paul C, Laessing U, Marx M, Bastmeyer M, Stuermer CA. Neurolin Ig domain 2 participates in retinal axon guidance and Ig domains 1 and 3 in fasciculation. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:339–49. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.2.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Shirabe K, Thisse C, Thisse B, Okamoto H, Masai I, Kuwada JY. Chemokine signaling guides axons within the retina in zebrafish. J Neurosci. 2005;25:1711–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4393-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopresti V, Macagno ER, Levinthal C. Structure and development of neuronal connections in isogenic organisms: cellular interactions in the development of the optic lamina of Daphnia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1973;70:433–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.2.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald R, Scholes J, Strahle U, Brennan C, Holder N, Brand M, Wilson SW. The Pax protein Noi is required for commissural axon pathway formation in the rostral forebrain. Development. 1997;124:2397–408. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.12.2397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masai I, Yamaguchi M, Tonou-Fujimori N, Komori A, Okamoto H. The hedgehog-PKA pathway regulates two distinct steps of the differentiation of retinal ganglion cells: the cell-cycle exit of retinoblasts and their neuronal maturation. Development. 2005;132:1539–53. doi: 10.1242/dev.01714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers PZ, Bastiani MJ. Growth cone dynamics during the migration of an identified commissural growth cone. J Neurosci. 1993;13:127–43. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-01-00127.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasevicius A, Ekker SC. Effective targeted gene ‘knockdown’ in zebrafish. Nat Genet. 2000;26:216–20. doi: 10.1038/79951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott H, Bastmeyer M, Stuermer CA. Neurolin, the goldfish homolog of DM-GRASP, is involved in retinal axon pathfinding to the optic disk. J Neurosci. 1998;18:3363–72. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-09-03363.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike SH, Melancon EF, Eisen JS. Pathfinding by zebrafish motoneurons in the absence of normal pioneer axons. Development. 1992;114:825–31. doi: 10.1242/dev.114.4.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raper JA, Bastiani M, Goodman CS. Pathfinding by neuronal growth cones in grasshopper embryos. II. Selective fasciculation onto specific axonal pathways. J Neurosci. 1983;3:31–41. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-01-00031.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raper JA, Bastiani MJ, Goodman CS. Pathfinding by neuronal growth cones in grasshopper embryos. IV. The effects of ablating the A and P axons upon the behavior of the G growth cone. J Neurosci. 1984;4:2329–45. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-09-02329.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuermer CA. Retinotopic organization of the developing retinotectal projection in the zebrafish embryo. J Neurosci. 1988;8:4513–30. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-12-04513.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tessier-Lavigne M, Goodman CS. The molecular biology of axon guidance. Science. 1996;274:1123–33. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5290.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson H, Camand O, Barker D, Erskine L. Slit proteins regulate distinct aspects of retinal ganglion cell axon guidance within dorsal and ventral retina. J Neurosci. 2006;26:8082–91. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1342-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlock KE, Westerfield M. A transient population of neurons pioneers the olfactory pathway in the zebrafish. J Neurosci. 1998;18:8919–27. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-21-08919.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DW, Shepherd D. Persistent larval sensory neurones are required for the normal development of the adult sensory afferent projections in Drosophila. Development. 2002;129:617–24. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.3.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson BD, Ii M, Park KW, Suli A, Sorensen LK, Larrieu-Lahargue F, Urness LD, Suh W, Asai J, Kock GA, et al. Netrins promote developmental and therapeutic angiogenesis. Science. 2006;313:640–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1124704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao T, Roeser T, Staub W, Baier H. A GFP-based genetic screen reveals mutations that disrupt the architecture of the zebrafish retinotectal projection. Development. 2005;132:2955–67. doi: 10.1242/dev.01861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelina P, Avci HX, Thelen K, Pollerberg GE. The cell adhesion molecule NrCAM is crucial for growth cone behaviour and pathfinding of retinal ganglion cell axons. Development. 2005;132:3609–18. doi: 10.1242/dev.01934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. ath5 MO does not grossly affect the lamination, position of presumptive optic nerve, or neurogenesis of non-RGCs in the retina. Coronal sections through 6dpf isl2b:GFP eyes after double-staining for GFP (B, E, H) and parvalbumin (Pv; C, F, I). (AC) Uninjected WT; (D–F) larva injected with control MO; (G–I) larva injected with high dose of ath5 TMO. (A′–I′) High-power views of A–I (see boxed areas in A, D, G). (A, D, G) DIC images show that retinal lamination is not affected in ath5 morphants, with the exception of a severely reduced RGC layer. (A′, D′, G′) The location of the presumptive optic nerve (on) and optic nerve head (onh, arrows), as well as a break in the RPE that represents the normal exit point for retinal axons, are clearly identifiable in ath5 morphants. (B, E, H) In controls, isl2b:GFP staining shows RGCs throughout the entire RGC layer (rgc, arrows) and their axons exiting the eye in the optic nerve (on, arrowhead). However, in ath5 morphants (H), central RGCs do not differentiate, although later-born RGCs in the periphery differentiate normally (arrow). In addition, no axons exit the eye (open arrowhead). Staining in central retina represents axons from peripheral RGCs (open arrow). GFP+ photoreceptors labeled by isl2b:gfp differentiate normally in ath5 morphants (B, E, H; small arrows). (C, F, I) Differentiation of Pv+ amacrine cells in the inner nuclear layer (a, arrows) and displaced amacrine cells in the RGC layer (da, arrowheads) appears unaffected in ath5 morphants. Scale bar, 100μm.

Supplementary Figure 2. Eight-point scoring system used to quantify retinal axon errors. Dorsal views of retinotectal projection of 5dpf isl2b:gfp WT and ast larvae. (A) In WT embryos, retinal axons always pathfind to the tectum, and errors are almost never seen. (B) In ast null mutants, eight classes of errors are commonly seen, including midline crossing at the habenular and posterior commissures, and projections to the left and right telencephalon, diencephalon, ventral hindbrain (stars). Counting the classes of errors made by misguided axons in each larva yields an error score between 0 and 8.

Supplementary Figure 3. Background removal procedure used for transplant images. Dorsal views of projections made by donor axons in 5 dpf host larvae, control transplants. (A, B) Maximum-intensity z-projections of unedited confocal stack in WT>WT (A) and ast>ast (B) transplants. Autofluorescence in skin, superficial to axons, partially obscures the retinal projection. (A′, B′) Confocal projections shown after removing autofluorescence slice-by-slice by manual editing in ImageJ and Adobe Photoshop. Retinal axons are unaffected, but can be seen more clearly in the absence of skin fluorescence. stars indicate errors (always counted in unedited confocal stacks); dotted outlines show eye positions. All transplant images in Figs. 5 and 6 were processed in this manner.

Supplementary Movie 1. Volume reconstruction of Figure 2E’s 72 hpf isl2b:gfp ath5 morphant eye. GFP (green) labels RGCs; lens autofluorescence has been removed by manual editing of the confocal stack. In the initial frame, dorsal is up, anterior right, medial (i.e., the back of the eye) towards the viewer. The reconstruction is rotated first around the dorsoventral axis, then the anteroposterior axis. Axons are seen within the RGC layer, but do not exit the eye. See Fig. 2E for scale bar and other annotation.

Supplementary Movie 2. Confocal imaging of a 42 hpf isl2b:gfp eye, stained with ToPro3 to label nuclei and dissected away from the embryo. GFP (green) labels RGCs, while ToPro3 (magenta) labels all nuclei. Dorsal is up, anterior is right. The movie starts medially and progresses laterally. The optic nerve is seen exiting the eye, and can be traced back to the RGCs. At ~40% through the movie, a single nonretinal GFP+ neuron (presumably from the trigeminal ganglion) can be seen at the upper right. 97 serial sections spaced 1.6 μm apart; voxel size 0.5 × 0.5 × 1.6 μm. This eye had 553 RGCs (GFP+, ToPro3+ nuclei); 3 eyes from different 42 hpf embryos gave a mean of 625±92 (s.d.) RGCs.

Supplementary Movie 3. Volume reconstruction of the 42 hpf isl2b:gfp eye, stained with ToPro3, from Supplementary Movie 2. GFP (green) labels RGCs, while ToPro3 (magenta) labels all nuclei. Orientation of initial frame: dorsal up, anterior left (reversed left-right from Supplementary Movie 2). A single nonretinal GFP+ neuron (presumably from the trigeminal ganglion) can be seen.