Abstract

Sir2 NAD+-dependent protein deacetylases are implicated in a variety of cellular processes such as apoptosis, gene silencing, life-span regulation, and fatty acid metabolism. In spite of this, there have been relatively few investigations into the detailed chemical mechanism. Sir2 proteins (sirtuins) catalyze the chemical conversion of NAD+ and acetylated-lysine to nicotinamide, deacetylated-lysine, and 2’-O-acetyl-ADP-ribose (OAADPr). In this study, Sir2-catalyzed reactions are shown to transfer an 18O-label from the peptide acetyl group to the ribose 1’-position of OAADPr, providing direct evidence for the formation of a covalent α-1’-O-alkylamidate, whose existence is further supported by the observed methanolysis of the α-1’-O-alkylamidate intermediate to yield β-1’-O-methyl-ADP-ribose in a Sir2 histidine-to-alanine mutant. This conserved histidine (His-135 in HST2) activates the ribose 2’-hydroxyl for attack on the α-1’-O-alkylamidate. The histidine mutant is stalled at the intermediate, allowing water and other alcohols to compete kinetically with the attacking 2’-hydroxyl. Measurement of the pH dependence of kcat and kcat/Km values for both wild-type and histidine-to-alanine mutant enzymes confirms roles of this residue in NAD+-binding and in general-base activation of the 2’-hydroxyl. Also, transfer of an 18O-label from water to the carbonyl oxygen of the acetyl group in OAADPr is consistent with water addition to the proposed 1’-2’cyclic intermediate formed after 2’-hydroxyl attack on the α-1’-O-alkylamidate. The effect of pH and of solvent viscosity on the kcat values suggests that final product release is rate-limiting in the wild-type enzyme. Implications of this new evidence on the mechanisms of deacetylation and possible ADP-ribosylation catalyzed by Sir2 deacetylases are discussed.

Keywords: SIR2, sirtuin, Deacetylation, NAD, Histone

The growing interest in the silent information regulator 2 (Sir2 or sirtuin) family of proteins lies in their involvement in a rapidly expanding list of cellular processes including gene silencing (1, 2), cell cycle regulation (3), fatty acid metabolism (4), apoptosis (5-7), and lifespan extension (8-10). Conserved among all forms of life with five homologs in yeast (ySir2 and HST1−4) and seven in humans (SIRT1−7) (11, 12), most sirtuins display NAD+-dependent protein deacetylase activity (13-16). SIRT1 has received the most attention and is reported to deacetylate a growing number of substrates including PGC-1α (17, 18), FOXO proteins (19-21), and HIV Tat protein (22) suggesting its involvement in a broad range of biological processes such as glucose homeostasis, cell survival under stress, and HIV transcription. In contrast to the primarily nuclear SIRT1, SIRT2 is localized to the cytoplasm where it can deacetylate α-tubulin (23), and SIRT3, SIRT4, and SIRT5 are located in the mitochondrial matrix (24-26), but knowledge of their cellular targets is uncertain. The other human homologs, SIRT6 and SIRT7, are found in the nucleus (24), where SIRT6 is reported to possess ADP-ribosyltransferase activity (27).

The majority of Sir2 homologs are protein deacetylases catalyzing the conversion of NAD+ and an acetylated-lysine residue to nicotinamide, the corresponding deacetylated-lysine residue, and 2’-O-acetyl-ADP-ribose (OAADPr) (Scheme 1) (28-30). This mechanism differs from that of class I and II histone deacetylases (HDACs), in which an active-site zinc directs hydrolysis of the acetylated-lysine residues to acetate and free lysine (31). This unusual consumption of NAD+ in sirtuins (class III HDACs) with linked generation of the novel product OAADPr, has led to the idea that OAADPr possesses unique biological properties and whose cellular levels may be tightly regulated (32). Indeed, OAADPr was shown to be metabolized by a variety of cell extracts (33, 34). In more recent evidence, OAADPr was shown to bind specifically to the histone splice variant macro H2A1.1 (35) and to induce formation of the yeast Sir2/Sir3/Sir4 complex in vitro (36).

Scheme 1.

General reaction catalyzed by Sir2 protein deacetylases.

The growing list of reported Sir2 substrates and the generation of the potential secondary messenger, OAADPr, has led to increased efforts to elucidate the molecular basis of Sir2 catalyzed deacetylation. Previously, kinetic analyses have shown that Sir2 deacetylases follow a sequential mechanism in which acetylated protein and then NAD+ bind to form a ternary complex before chemical catalysis occurs in two kinetically-distinct steps (37). In the initial chemical step, nicotinamide is released upon formation of an enzyme:ADP-ribose:acetylated protein intermediate, which has been postulated to be an α-1’-O-alkylamidate (Scheme 1) (28-30). One line of evidence for an α-1’-O-alkylamidate is the ability of nicotinamide, a potent product inhibitor (15, 16, 38-40), to rapidly react with the enzyme:ADP-ribose:acetylated protein intermediate, regenerating NAD+ and acetylated protein by a process dubbed the nicotinamide exchange (or transglycosidation) reaction (39, 40). In addition, the 2’-hydroxyl of NAD+ does not play a significant role in the first chemical step since replacement with fluorine results in only a slight decrease in the nicotinamide exchange rate (39). This suggested that the initial step occurs exclusively about the 1’-position and that the acetylated-lysine carbonyl oxygen acts as a nucleophile directly displacing nicotinamide. However, little evidence has been presented to support this hypothesis. In the second chemical step, the acetyl-group is transferred to the ADP-ribose portion of NAD+. It is believed that an active-site histidine acts as the general base, activating the 2’-hydroxyl for acetyl-transfer, but direct evidence for this is also lacking.

Here, we report direct evidence supporting the nucleophilic attack of the acetyl-lysine oxygen at the alpha face of the nicotinamide ribose to form a covalent α-1’-O-alkylamidate intermediate. In addition, we provide biochemical evidence for the role of the active-site histidine as a general base, and for the identity of the rate-limiting step in Sir2 catalysis. The implications of these findings on both the mechanism of deacetylation and the potential mechanism of ADP-ribosylation are discussed.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials and Methods

Synthetic 11-mer H3 peptide and acetylated H3 peptide (AcH3), corresponding to the 11 amino acids surrounding and including lysine-14 of the histone H3 N-terminal tail; H2N-KSTGGK(Ac)APRKQ-CONH2, were purchased from the University of Wisconsin-Madison peptide synthesis center, 3H-labeled Acetyl H3-peptide (3H-AcH3) was synthesized enzymatically from the 11-mer H3 peptide as previously reported (33). 18O-labelled water was purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc. (Andover, MA). All other chemicals used were of the highest purity commercially available and were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO), Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI), or Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). All mass spectral analysis was performed at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Biotechnology Center mass spectrometry facility.

Expression and Purification of His-Tagged HST2 WT and HST2 H135A

The expression and purification of histidine-tagged full-length HST2 WT and HST2 H135A was performed as previously reported (30), and the concentration of enzyme was determined using the method of Bradford (41). Enzyme aliquots were stored at −20 °C until ready for use.

Synthesis of 18O-AcH3

Synthetic 18O-labelled acetylated H3 peptide (18O-AcH3), H2N-KSTGGK(18O-Ac)APRKQ-CONH2, was synthesized using standard tBu/Fmoc solid-phase peptide synthesis techniques and HBTU/HOBt coupling conditions (42). The 18O-label was specifically incorporated at the desired lysine sidechain by using an ivDde protecting group that was orthogonally deprotected with 2% hydrazine in DMF. The liberated ε-amino group was then coupled to 18O-labelled acetic acid using HBTU/HOBt coupling conditions resulting in the full-length peptide, which was then deprotected and cleaved from the resin using TFA.

18O-labelling experiments

Experiments for HST2 WT were done in 60 μL reaction volumes containing 1 mM DTT, 200 μM 18O-AcH3, 185 μM NAD+, 10 μM HST2, in natural abundance water or 90% 18OH2 (98% 18O), and 20 mM pyridine buffer adjusted to pH 7 with formic acid, and were reacted for 30 minutes at 25 °C. Reactions were split into three 20 μL aliquots and flash frozen in dry ice. One aliquot was submitted directly for mass spectral analysis (ESI, (−)-ion mode, Applied Biosystems, MDS Sciex API 365, LC/MS/MS triple quadrupole). The other two aliquots were lyophilized and redissolved in 20 μL 10% formic acid and 90% natural abundance OH2 or 18OH2 (98% 18O) and incubated at room temperature for 2 hours. These were then flash frozen and kept at −20 °C until ready for mass spectral analysis and analyzed as above. The degree of 18O incorporation was determined by examining the relative peak heights at ∼600.5, ∼602.5, and ∼604.5 m/z corresponding to incorporation of zero, one, or two 18O atoms.

18O-labelling experiments for HST2 H135A were done in 80 μL reaction volumes containing 1 mM DTT, 400 μM AcH3 (11-mer), 500 μM NAD+, 50 μM HST2 H135A, in natural abundance water or 84% 18OH2 (98% 18O), and 20 mM pyridine buffer adjusted to pH 7 with formic acid, and were reacted for 30 minutes at 25 °C. Reactions were split into three aliquots and analyzed by ESI-MS as stated above for HST2 WT. The degree of 18O incorporation was determined by examining the relative peak heights at ∼558 and ∼560 m/z for ADPr and ∼600.5, ∼602.5, and ∼604.5 m/z for OAADPr.

Measurement of the rate of non-enzymatic 18O incorporation of OAADPr

OAADPr was synthesized and purified as previously reported (33). Solutions of 16.5 μM OAADPr, 20 mM pyridine buffer adjusted to pH 7 with formic acid, and 90% 18OH2 were made. Timepoints from 5 to 140 minutes were analyzed by ESI-MS without further processing. The fraction of 18O-incorporation was determined by the ratio of the peak height at ∼602.5 m/z corresponding to OAADPr with one 18O-label to the sum of the peak heights at ∼600.5 m/z and ∼602.5 m/z.

pH profile experiments

The effect of pH on the kinetic parameters of HST2 WT was determined over a pH range of 5.4 to 9.4. Reactions containing 150 μM 3H-AcH3, 1 mM DTT, 0.02−2 μM HST2 WT, and varying concentrations of NAD+ from 5−320 μM in TBA buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl, 50 mM BisTris-Cl, 100 mM sodium acetate) were analyzed by charcoal binding assay as published (43). To ensure initial rate conditions, the reactions were quenched before 10% of the substrate was converted to products. The effect of pH on HST2 H135A was determined over a pH range of 5.8 to 9.4 with 2−3 mM 3H-AcH3, 1 mM DTT, 2−5 μM HST2 H135A, and varying concentrations of NAD+ from 5−1280 μM in TBA buffer. Graphs of rate (s−1) versus NAD+ concentration were fitted to the Michaelis-Menten equation (equation 1) using Kaleidagraph (Synergy Software, Reading, PA) to obtain the kinetic parameters kcat and kcat/Km.

| (1) |

Plots of kcat or kcat/Km versus pH were fitted to equation 2 using KinetAsyst (IntelliKinetics, State College, PA), where C is the pH-independent value, and Ka is the ionization constant, and H is the proton concentration.

| (2) |

Solvent viscosity studies

The effect of viscosity on HST2 WT and HST2 H135A were determined using sucrose as a microviscogen. The steady-state parameters for HST2 WT were determined using the charcoal binding assay (43) and 80 μL reaction volumes with 500 μM NAD+, 2−64 μM AcH3 (11-mer), 1 mM DTT, 0−34% w/v sucrose, and 30−40 nM HST2 WT in TBA buffer at pH 8. The steady-state parameters for HST2 H135A were determined using the charcoal binding assay (43) and 80 μL reaction volumes with 2 mM NAD+, 150−2400 μM AcH3 (11-mer), 1 mM DTT, 0−34% w/v sucrose, and 30−40 nM HST2 WT in TBA buffer at pH 8. Graphs of rate (s−1) versus AcH3 concentration were fitted to the equation 1 to obtain the kinetic parameters kcat and kcat/Km in Kaleidagraph. The ratio of the kcat measured at 0% sucrose (kcat0) to the kcat at each concentration of sucrose was plotted versus the relative viscosity of each sucrose solution. The relative viscosities of the reaction solutions as a function of sucrose percentage were taken from those measured by Murray et al. (44).

Measurement of ADPr and OAADPr formation with HST2 H135A

ADPr and OAADPr formation over time was measuring using 20 μL reaction volumes with 400−600 μM AcH3 (11-mer), 1 mM DTT, 500−1000 μM 32P-NAD+, 20−200 μM HST2 H135A or 0.5−50 μM HST2 WT, and 20−50 mM Tris-Cl buffer at pH 7.5 at 25 °C. ADPr and OAADPr formation was measured using the previously described thin layer chromatography (TLC) assay (16, 43, 45) with the following modifications. Reactions were quenched by spotting 1 μL timepoints of the reactions directly onto the silica-gel TLC plates. The plates were then run in 70:30 ethanol:2.5 M ammonium acetate and quantitated by phosphorimaging. Under these conditions OAADPr, ADPr, and NAD+ ran with an average Rf of 0.53, 0.42, and 0.26, respectively.

Trapping of an enzyme:ADPr:acetyl-lysine intermediate in HST2 H135A with MeOH and EtOH

20 μL reaction volumes containing 1 mM DTT, 400 μM AcH3 (11-mer), 500 μM NAD+, 50 μM HST2 H135A, 20% alcohol by volume (4.93 M MeOH or 3.39 M EtOH), and 20 mM pyridine buffer adjusted to pH 7 with formic acid were reacted for 30 minutes at 25 °C. Reactions were flash frozen in dry ice and stored at −20 °C until ready for ESI-MS analysis as outlined above for the 18O-labelling experiments. A control reaction was run with the above conditions and 21 μM HST2 WT to determine if the methanolysis observed was specific to the mutant enzyme. A no enzyme control was run with 500 μM ADPr replacing NAD+ and the above conditions to measure the non-enzymatic methanol incorporation over 30 minutes.

Synthesis, Purification, and Characterization of 1’-O-methyl-ADPr

A 1 mL reaction containing 1.8 mM AcH3 (11-mer), 2 mM NAD+, 1 mM DTT, 100 μM HST2 H135A, 5 M methanol, and 50 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.5 was reacted for 2.5 hours at 25 °C and quenched with TFA to a final concentration of 1%. The 1’-O-methyl-ADPr formed during this reaction was purified on a reversed phase, small pore C18 column (Vydac, Hesperia, CA) eluting with 0−20% acetonitrile (with 0.02% TFA) in water (with 0.05% TFA) and further purified on a PolyHydroxyethyl Aspartamide column (The Nest Group, Inc., Southboro, MA) eluting with 30 mM ammonium acetate and a gradient of 0−100% water in 85% acetonitrile. Fractions containing the purified product were pooled and lyophilized twice from D2O, then dissolved in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer pD 7.1. 1H-NMR spectra were obtained at 500 MHz on a Varian INOVA-500 NMR spectrometer and compared to previously published spectra for stereochemical assignment (46).

Measurement of the relative formation of ADPr and 1’-O-methyl-ADPr by HST2 H135A

60 or 120 μL reactions containing 0.5−4 M methanol, 400 μM AcH3 (11-mer), 500 μM 32P-NAD+, 1mM DTT, 50 μM HST2 H135A, and 50 mM Tris-Cl buffer at pH 7.5 were reacted at 25 °C for 30 minutes. The reactions were analyzed by the previously described HPLC assay (43) and quantitated by UV absorbance of the adenine base at 260 nm or scintillation counting of the collected fractions. The product partitioning ratio, K, at each concentration of methanol was calculated from equation 3 assuming a water concentration of 55 M.

| (3) |

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Source of new oxygens in the product OAADPr

The Sir2 reaction incorporates two new oxygens into the product, OAADPr, one from the net hydrolysis of the glycosidic bond and one from acetyl group transfer to OAADPr. The source of these oxygens presumably is from water and the acetyl oxygen of the acetylated-lysine residue. Therefore, determining the precise fate (i.e. location about the ribose ring) of these oxygens as they are transferred to OAADPr is essential in support of the proposed α-1’-O-alkylamidate intermediate (Scheme 1). This was accomplished through specific 18O-labelling experiments followed by mass-spectral analysis.

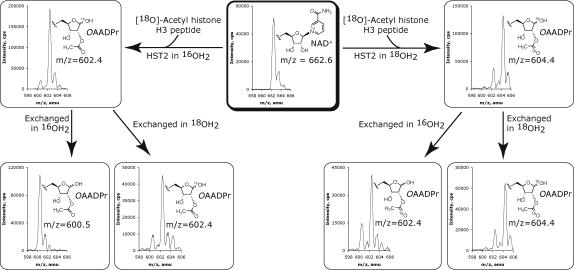

The yeast Sir2 homolog, HST2, was reacted with NAD+ and an 11-mer peptide based on the N-terminal tail of histone H3 (H2N-KSTGGK(18O-Ac)APRK-CONH2, 18O-AcH3) with a specific 18O-label at the sidechain corresponding to acetylated-lysine-14. This reaction revealed the incorporation of one 18O-label into OAADPr as seen by the major ESI-MS peak at 602.4 m/z (Figure 1A). Control experiments confirmed that this incorporation was enzymatic, instead of non-enzymatic incorporation over time (Figure 1B). Incubation of a lyophilized aliquot of the original reaction solution in 10% formic acid with 18O-water resulted in no change in mass (Figure 1A). However, the transferred 18O-label was completely washed out when a separate lyophilized aliquot was redissolved in 10% formic acid in natural abundance water, as shown by the major ESI-MS peak at 600.5 m/z (Figure 1A). This indicated that the 18O-label from 18O-AcH3 was specifically transferred to the 1’-hydroxyl of OAADPr since only the 1’-hydroxyl can exchange with bulk solvent under these acidified conditions. This result presents the first direct evidence for the attack of the acetylated-lysine oxygen at the 1’-position of the nicotinamide ribose to form the initial α-1’-O-alkylamidate intermediate.

Figure 1.

(A) 18O-labelling experiments with HST2 WT. Reactions contained 1 mM DTT, 200 μM18O-AcH3, 185 μM NAD+, 10 μM HST2, in natural abundance water or 90% 18OH2, and 20 mM pyridine buffer at pH 7. Each reaction was split into three aliquots, two of which were lyophilized and exchanged in 10% formic acid and 90% natural abundance OH2 or 18OH2. 18O incorporation was determined by examining the relative peak heights at ∼600.5, ∼602.5, and ∼604.5 m/z corresponding to zero, one, or two 18O atoms. (B) The rate of non-enzymatic exchange of an 18O-label from water into OAADPr. Purified OAADPr was diluted to 16.5 μM in 20 mM pyridine buffer and 90% 18OH2 at pH 7. Timepoints were injected directly into the mass spectrometer. The y-intercept, which represents the zero-timepoint before exposing OAADPr to 18O-water, was calculated as 13.3%, and is consistent with the natural distribution of heavy isotopes across the entire OAADPr molecule. A rate of non-enzymatic incorporation of 0.15% per minute was calculated, which corresponds to a maximum of 4.5% non-enzymatic incorporation for the 30-minute reaction time used in our assays.

Reactions of HST2 were then carried out with 18O-AcH3 peptide and 18O-water, resulting in the major mass spectral peak at 604.4 m/z, indicating incorporation of 18O labels at two separate positions (Figure 1A). Incorporation of two labels confirmed that water was the source of the other new oxygen in OAADPr. Subsequent acid exchange of OAADPr in natural abundance water showed a decrease of two mass units as seen by a peak at 602.4 m/z, indicating the label arising from water was in a non-exchangeable position (Figure 1A). The fact that the 18O-label from water could not be exchanged indicated its placement as the acetyl carbonyl oxygen in OAADPr, consistent with a previous report by Sauve and Schramm (29).

Effect of pH on the activity of HST2 WT and HST2 H135A

The active-site histidine corresponding to His-135 in HST2 is invariant among Sir2 enzymes. From the known crystal structures with either NAD+, ADPr, or OAADPr bound (47-52), the sidechain imidazole group of this histidine is generally positioned near the 3’-hydroxyl of the NAD+ nicotinamide ribose. This histidine has therefore been postulated to be the general base responsible for activating the 2’-hydroxyl for attack of the proposed α-1’-O-alkylamidate intermediate and subsequent acetyl transfer to the 2’-position.

To provide direct biochemical evidence for His-135 as a general base in the Sir2 deacetylation mechanism, the effect of pH on the kcat/Km and kcat of both HST2 and the corresponding histidine-to-alanine mutant enzyme, HST2 H135A, was determined. These experiments were performed by varying NAD+ at saturating AcH3 concentrations such that the pH dependency of kcat/Km would reflect ionizations critical for any steps from NAD+ binding to nicotinamide release. Determination of HST2 WT kcat/Km values over a pH range from 5.4 to 9.4 revealed a critical ionization with a pKa value of 6.77 ± 0.06 that must be unprotonated for activity (Figure 2A), consistent with the pKa expected for a histidine sidechain. Conversely, the kcat/Km profile for HST2 H135A exhibited no pH dependence over the range tested, with kcat/Km values two orders of magnitude lower than wild-type at high pH ([2.75 ± 0.22] × 104 M−1s−1 for HST2 WT versus [1.5 ± 0.2] × 102 M−1s−1 for HST2 H135A). It was previously shown that HST2 H135A exhibits only a three-fold lower nicotinamide exchange rate compared to HST2 WT, suggesting that His-135 does not participate significantly in the chemical steps involving nicotinamide cleavage and release (39). Therefore, the critical ionization seen in the wild-type kcat/Km pH profile is consistent with the His-135 sidechain binding and positioning NAD+ into its catalytically productive conformation.

Figure 2.

pH rate profiles. Reaction rates were determined based on OAADPr formation. Reactions for HST2 WT contained 150 μM 3H-AcH3, 1 mM DTT, 0.02−2 μM HST2 WT, and varying concentrations of NAD+ from 5−320 μM in TBA buffer. Reaction for HST2 H135A contained 2−3 mM 3H-AcH3, 1 mM DTT, 2−5 μM HST2 H135A, and varying concentrations of NAD+ from 5−1280 μM in TBA buffer. (A) Effect of pH on kcat/Km varying NAD+ for HST2 WT (squares) and HST2 H135A (circles). HST2 WT displayed a critical ionization with a pKa of 6.77 ± 0.06, while HST2 H135A exhibited no effect over the pH range tested. (B) Effect of pH on kcat for HST2 WT (squares) and HST2 H135A (circles). HST2 H135A displayed a critical ionization with a pKa of 7.43 ± 0.13 while HST2 WT showed no critical ionizations over the pH range tested.

Conversely, the kcat pH profile for HST2 WT showed no critical ionizations, but did show a slight pH dependence that varied only 3−4-fold (0.07 s−1 at low pH and 0.26 s−1 at high pH) across >4 pH units (Figure 2B). The lack of a critical ionization is consistent with a pH-independent product release step limiting turnover, as was previously suggested (37). In contrast, HST2 H135A exhibited kcat values one to two orders of magnitude lower than wild-type enzyme (0.26 ± 0.03 s−1 vs. 0.026 ± 0.005 s−1 at high pH), and a pH-dependency on kcat revealing an ionization (pKa 7.43 ± 0.13) that must be unprotonated for activity (Figure 2B). This decrease in reaction rate (10-fold at pH values >8), coupled with the alteration in the pH-dependency, indicates a change in the rate-limiting step from a pH-independent step (observed with wild-type) to a pH-dependent chemical step in HST2 H135A. The source of the ionization observed in the mutant kcat pH profile is unclear. It would be attractive to suggest that this group, which must be unprotonated, is the ribose 2’OH; however, with an apparent pKa of 7.4, this would be ∼5 pH units lower than that expected, making this possibility seem implausible. On the other hand, the flattening out of the curve above an apparent pKa of 7.4 may result from a downstream pH-independent step beginning to limit turnover at very high pH, whereas at low pH, the rate increases as a function of the 2’-OH ionization.

As mentioned earlier, the Sir2 chemical reaction can be kinetically resolved into two main steps: (1) attack of the acetyl-lysine oxygen to form the proposed α-1’-O-alkylamidate with nicotinamide release and (2) attack of the 2’-hydroxyl at the proposed α-1’-O-alkylamidate and subsequent acetyl-transfer to form OAADPr (28-30, 37, 39, 40). The small three-fold change in the nicotinamide exchange rate observed between HST2 WT and HST2 H135A (39) suggests that the slowed catalytic step seen in the HST2 H135A kcat pH profile (Figure 2B) occurs after nicotinamide cleavage and release, but before OAADPr and peptide release. By default, this affected step would be the 2’-hydroxyl attack of the α-1’-O-alkylamidate intermediate, which is expedited in wild-type by His-135 functioning as the general base, but is impaired in HST2 H135A. This possibility was explored further in subsequent experiments.

Effect of viscosity on the rate of deacetylation

The lack of pH-dependency on the kcat for the wild-type enzyme suggested that product release might be rate-limiting. To test this hypothesis, solvent viscosity studies were carried out. Since the diffusion rate of small molecules is inversely proportional to the viscosity of the solvent (53), the overall rate of enzymatic reactions in which product release or substrate association is rate-limiting can display a linear dependence on the viscosity of the solution (54-57). In the case of product release, this step could be either the dissociation of product from the enzyme or a conformational change allowing dissociation. Therefore, a slope equal to unity in a plot of the inverse of the relative rate constant (kcat0/kcat) versus the relative viscosity of the solution reflects a substrate association or product release as rate-limiting step, whereas a slope of zero reflects a non-diffusion-mediated step such as chemical catalysis. Indeed, using sucrose as a viscogen, we found that the kcat of HST2 WT varied linearly (slope = 1.15 ± 0.07) with the relative viscosity of the solution (Figure 3). In contrast, the kcat of HST2 H135A displayed no dependence on viscosity (Figure 3). The kcat/Km values with acetylated peptide displayed no viscosity dependence (data not shown). With overall turnover rate of ∼ 0.26 s−1 for HST2 WT, the viscosity dependence observed is likely due to a conformational change within the active-site allowing product (OAADPr and/or peptide) release, whereas the mutant enzyme rate appears to be restricted at the chemical step involving 2’-hydroxyl attack of the α-1’-O-alkylamidate intermediate.

Figure 3.

Effect of viscosity on kcat. Reaction rates were determined based on OAADPr formation. kcat0/kcat is the kcat the absence of sucrose divided by the kcat measured at each concentration of sucrose. HST2 WT (squares) reactions contained 500 μM NAD+, 2−64 μM AcH3 (11-mer) from, 1 mM DTT, 0−34% w/v sucrose, and 30−40 nM HST2 WT in TBA buffer at pH 8. HST2 H135A (circles) reactions contained 2 mM NAD+, 150−2400 μM AcH3 (11-mer), 1 mM DTT, 0−34% w/v sucrose, and 30−40 nM HST2 WT in TBA buffer at pH 8. Linear regression analysis showed a slope of 1.15 ± 0.07 for HST2 WT and 0.02 ± 0.12 for HST2 H135A.

Partitioning between ADPr and OAADPr in HST2 H135A

While analyzing the H135A mutant enzyme, we observed significant production of ADP-ribose (ADPr) during turnover that also yielded OAADPr (39). As OAADPr is susceptible to non-enzymatic hydrolysis to form ADPr and acetate, it was important to establish the source of observed ADPr. The relative amounts of ADPr and OAADPr formed in the enzyme reactions were measured as outlined under experimental procedures. From these assays, it was confirmed that ADPr formation observed with HST2 H135A was not from hydrolysis of OAADPr, but was due to inherent activity of HST2 H135A (Figure 4). The negligible ADPr detected for HST2 WT did not exceed background levels and did not increase over time (Figure 4). In addition, HST2 H135A formed products OAADPr:ADPr in a constant ratio of 25:14 over the entire time-course of this assay, suggesting partitioning of a common intermediate between attack of the 2’-hydroxyl to form OAADPr and hydrolysis to form ADPr (Scheme 2). With the H135A mutant, this partitioning is consistent with the lack of 2’-hydroxyl activation by His-135, resulting in the increased lifetime of the α-1’-O-alkylamidate intermediate such that hydrolysis to form ADPr now acts as a competing reaction with formation of OAADPr.

Figure 4.

The relative formation of ADPr and OAADPr. Reactions contained 400−600 μM AcH3 (11-mer), 1 mM DTT, 500−1000 μM 32P-NAD+, 20−200 μM HST2 H135A or 0.5−50 μM HST2 WT, and 20−50 mM Tris-Cl buffer at pH 7.5 and 25 °C. The ADPr observed from HST2 WT was at background levels and its formation did not increase over time. Each column was normalized to the total product formed a each timepoint. Error bars represent standard deviations.

Scheme 2.

Proposed mechanism of formation of both ADPr and OAADPr in HST2 H135A.

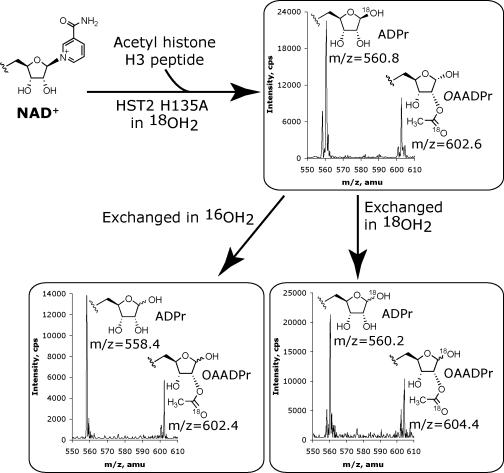

Hydrolysis of enzyme:ADPr:acetyl-lysine intermediate to ADP-ribose in HST2 H135A

To further characterize the mechanism by which HST2 H135A forms ADPr, 18O-labeling experiments similar to those outlined above for HST2 WT were performed. Both ADPr and OAADPr showed the incorporation of a single 18O-label (Figure 5). Subsequent acid exchange of the 1’-hydroxyl in natural abundance water decreased the mass of ADPr by two mass units indicating that the 18O-label from water was at the 1’-position in ADPr. The enzymatic formation of ADPr was completely dependent on the presence of the acetyl-lysine peptide, as control reactions lacking AcH3 showed no conversion of NAD+ by ESI-MS (data not shown) indicating that the enzyme must be able to form the proposed α-1’-O-alkylamidate intermediate in order for hydrolysis to ADPr to occur. Furthermore, AcH3 showed no incorporation of an 18O-label under the same reaction conditions by MALDI-MS (data not shown), adding to the evidence that hydrolysis to ADPr is due to the specific attack of water at the 1’-carbon of the nicotinamide ribose and not due to hydrolysis by attack of water at the imidate carbon of the α-1’-O-alkylamidate. In accordance with the previous 18O-labelling experiments using HST2 WT, the 18O-label from OAADPr was non-exchangeable, and therefore is located in the acetyl carbonyl oxygen indicating that OAADPr is formed by the same mechanism in the mutant enzyme as in wild-type. These HST2 H135A 18O-labelling experiments are consistent with the proposed mechanism in which the hydrolysis to ADPr is in direct competition with the attack of the 2’-hydroxyl to form a 1’-2’-cyclic intermediate that is attacked by water to form OAADPr (Scheme 2).

Figure 5.

18O-labelling experiments with HST2 H135A. Reactions contained 1 mM DTT, 400 μM AcH3 (11-mer), 500 μM NAD+, 50 μM HST2 H135A, 84% 18OH2, and 20 mM pyridine buffer adjusted at pH 7 were reacted for 30 minutes at 25 °C. Reactions were split into three aliquots, two of which were lyophilized and then exchanged in 10% formic acid and 90% natural abundance OH2 or 18OH2. 18O incorporation was determined by examining the relative peak heights at ∼600.5, ∼602.5, and ∼604.5 m/z corresponding to zero, one, or two 18O atoms.

Trapping of the intermediate with alcohol nucleophiles

In the H135A mutant, the observed hydrolysis of the α-1’-O-alkylamidate to form ADPr suggested that exogenous alcohols could also be reacted. If so, this could provide additional evidence for the suggested stereochemistry and covalent nature of the α-1’-O-alkylamidate intermediate, since the 1’-O-alkyl-ADPr product formed from alcoholysis would be unable to undergo mutarotation. Therefore, H135A mutant reactions containing 20% methanol or ethanol by volume were reacted for 30 minutes and analyzed by ESI-MS. The spectra displayed a new product with a mass of 572.4 m/z, consistent with 1’-O-methyl-ADPr for methanol containing reactions, and a mass of 586.4 m/z, consistent with 1’-O-ethyl-ADPr for ethanol containing reactions (Figure 6A). Control reactions utilizing HST2 WT showed no formation of 1’-O-methyl-ADPr (Figure 6B). In addition, a no enzyme control with ADPr, 20% methanol, and identical buffer conditions gave no detectable incorporation of methanol over 30 minutes (Figure 6C). Therefore, the formation of 1’-O-methyl-ADPr and 1’-O-ethyl-ADPr is specific to HST2 H135A and is the direct result of methanolysis or ethanolysis of an enzymatic intermediate.

Figure 6.

(A) ESI-MS of the 30 minute reaction of HST2 H135A with 1 mM DTT, 400 μM AcH3 (11-mer), 500 μM NAD+, 50 μM HST2 H135A, 20% v/v MeOH, and 20 mM pyridine buffer at pH 7 at 25 °C. HST2 H135A forms ADPr, 1’-O-methyl-ADPr, and OAADPr under these conditions. (B) ESI-MS of the 30 minute control reaction of HST2 WT with 1 mM DTT, 400 μM AcH3 (11-mer), 500 μM NAD+, 21 μM HST2 WT, 20% v/v MeOH, and 20 mM pyridine buffer at pH 7 at 25 °C. HST2 WT forms no detectable 1’-O-methyl-ADPr under these reaction conditions. (C) ESI-MS of the 30 minute non-enzymatic incorporation of 20% v/v MeOH into 500 μM ADPr with 1 mM DTT, 400 μM AcH3 (11-mer), and 20 mM pyridine buffer at pH 7 at 25 °C. There was no detectable 1’-O-methyl-ADPr in this control. Therefore, the 1’-O-methyl-ADPr observed with HST2 H135A was due to enzymatic activity inherent in the mutant enzyme only.

To determine the stereochemistry of the enzyme synthesized 1’-O-methyl-ADPr, this product was purified from the HST2 H135A reaction by reverse-phase and hydrophilic interaction HPLC and analyzed by NMR spectroscopy. The stereochemistry about the 1’-position was assigned as beta by comparison with previously published spectra of β-1’-O-methyl-ADPr (46). Because Sir2 enzymes are not expected to possess an alcohol binding site that would direct alcohol attack stereoselectively, the stereochemical assignment of β-1’-O-methyl-ADPr provides direct evidence for a covalent intermediate formed on the alpha face of the ribose ring such that the alcohol nucleophiles react by a double-displacement mechanism. Together this data strongly suggests the existence of a covalent α-1’-O-alkylamidate intermediate during Sir2 catalysis.

Methanolysis versus hydrolysis reactivity profile

Previous studies of NAD+ glycohydrolases have gained valuable insights into the reactivity of catalytic intermediates by measurement of the product-partitioning ratio, K, for methanolysis versus hydrolysis (58-65). Using 0.5 to 4 M methanol, we determined a product-partitioning ratio for HST2 H135A of 26.2 ± 3.3 compared to the range of values from 11 to 200 reported for other NAD+ glycohydrolases (58-65). In contrast, non-enzymatic hydrolysis of NAD+ shows no preference for methanol over water, as the product ratio simply reflects the molar ratio of methanol to water as well as the high reactivity of the oxocarbenium intermediate formed during solvolysis (58, 60). Therefore, the selectivity for methanolysis observed here reflects enzyme stabilization of the intermediate compared to an oxocarbenium and indicates that the intermediate has significant bond order towards the incoming nucleophile. In addition, the ratio of methanolysis to hydrolysis was found to increase linearly with increasing concentrations of methanol, indicating that methanol was not saturating the active-site and that the observed selectivity was due to the increased nucleophilicity of methanol towards the enzyme stabilized α-1’-O-alkylamidate intermediate.

Implications towards the mechanism of ADP-ribosylation as catalyzed by Sir2 homologs

Recently, several reports have suggested that some Sir2 homologs possess ADP-ribosyltransferase activity (11, 13, 27, 66, 67). These findings are still controversial as the ADP-ribosylation activity has not been demonstrated to be catalytic. The results presented here provide some additional insight into possible mechanisms of the observed ADP-ribosylation. In particular, the ability of HST2 H135A to react with exogenous alcohol nucleophiles suggests that the α-1’-O-alkylamidate intermediate may be able to accept other protein nucleophiles as well, as was recently hypothesized (68). Therefore, while the active-site histidine corresponding to His-135 in HST2 is conserved across all yeast and human Sir2 homologs, this histidine may not be poised to activate the 2’-hydroxyl in Sir2 homologs that lack deacetylase activity. The loss of general base activation of the 2’-hydroxyl could allow reaction of the stalled α-1’-O-alkylamidate with an incoming nucleophile resulting in ADP-ribosylation and regeneration of the acetylated residue. This nucleophile could be from either another protein, the acetylated protein that reacted to form the α-1’-O-alkylamidate, or the Sir2 protein itself (resulting in auto ADP-ribosylation) (68). Although the above ADP-ribosylation mechanism requires an acetylated substrate to initiate formation of the α-1’-O-alkylamidate, it is possible that a Sir2 active-site residue, such as an asparagine or glutamine, could replace the acetylated-lysine residue to react in a manner similar to some NAD+ modifying enzymes. For example, CD38 is suggested to go through a glutamate:ADP-ribose covalent intermediate at the 1’-position in its catalysis to form cyclic-ADP-ribose (69). Future studies are necessary to reveal the significance of ADP-ribosylation activity from the sirtuin family of proteins.

CONCLUSION

In this study, we have presented valuable new insights into the chemical mechanism of Sir2 enzymes, using a variety of approaches including 18O-labelling analysis, solvent perturbation, and mutant and wild-type pH rate analysis. We provided the first direct evidence for the attack of the acetylated-lysine oxygen at the 1’-position of the nicotinamide ribose of NAD+ to form an α-1’-O-alkylamidate intermediate. Measurement of the effect of pH on the kcat and kcat/Km values for both HST2 WT and HST2 H135A supported the involvement of His-135 in both NAD+ binding/positioning and activation of the 2’-hydroxyl for attack of the α-1’-O-alkylamidate intermediate. Lack of pH dependence on kcat for HST2 WT suggested that product release was rate-limiting, a hypothesis supported through solvent viscosity experiments. The production of both OAADPr and ADPr by HST2 H135A was consistent with partitioning of the α-1’-O-alkylamidate intermediate between water attack and the 2’-hydroxyl of ribose. Hydrolysis required the presence of peptide substrate and the intermediate exhibited a preference for methanolysis to give β-1’-O-methyl-ADPr.

Having established the existence of the α-1’-O-alkylamidate intermediate, future work will utilize these findings in the design of mechanism-based inhibitors and activators of Sir2 enzymes. The discovery of more potent and specific chemical regulators of Sir2 activity would permit more specific investigations of Sir2-dependent cellular pathways, as well as potential treatments of cancer, ageing, diabetes, and neurodegeneration.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank members of the Denu group, especially Margie Borra and Chris Berndsen, for valuable discussions. We thank Norman Oppenheimer for helpful discussions and Michael Jackson for suggestions with the 18O-labelling experiments. We also thank for Gary Case for peptide syntheses and Amy Harms for assistance with the mass spectrometry experiments.

The abbreviations used are

- Sir2

silent information regulator 2

- NAD+

Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide, oxidized form

- ADPr

Adenosine 5’-diphosphoribose

- OAADPr

O-Acetyl-ADP-ribose

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM065386 (to J.M.D.) and by National Institutes of Health Biotechnology Training Grant NIH 5 T32 GM08349 (to B.C.S.). This study was also supported by the National Science Foundation grant NSF CHE-9629688 for the NMR spectrometer used.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rusche LN, Kirchmaier AL, Rine J. The establishment, inheritance, and function of silenced chromatin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:481–516. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gasser SM, Cockell MM. The molecular biology of the SIR proteins. Gene. 2001;279:1–16. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00741-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dryden SC, Nahhas FA, Nowak JE, Goustin AS, Tainsky MA. Role for human SIRT2 NAD-dependent deacetylase activity in control of mitotic exit in the cell cycle. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:3173–3185. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.9.3173-3185.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Starai VJ, Celic I, Cole RN, Boeke JD, Escalante-Semerena JC. Sir2-dependent activation of acetyl-CoA synthetase by deacetylation of active lysine. Science. 2002;298:2390–2392. doi: 10.1126/science.1077650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vaziri H, Dessain SK, Ng Eaton E, Imai SI, Frye RA, Pandita TK, Guarente L, Weinberg RA. hSIR2(SIRT1) functions as an NAD-dependent p53 deacetylase. Cell. 2001;107:149–159. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00527-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luo J, Nikolaev AY, Imai S, Chen D, Su F, Shiloh A, Guarente L, Gu W. Negative control of p53 by Sir2alpha promotes cell survival under stress. Cell. 2001;107:137–148. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00524-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Langley E, Pearson M, Faretta M, Bauer UM, Frye RA, Minucci S, Pelicci PG, Kouzarides T. Human SIR2 deacetylates p53 and antagonizes PML/p53-induced cellular senescence. Embo J. 2002;21:2383–2396. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.10.2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaeberlein M, McVey M, Guarente L. The SIR2/3/4 complex and SIR2 alone promote longevity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by two different mechanisms. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2570–2580. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.19.2570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rogina B, Helfand SL. Sir2 mediates longevity in the fly through a pathway related to calorie restriction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:15998–16003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404184101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tissenbaum HA, Guarente L. Increased dosage of a sir-2 gene extends lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2001;410:227–230. doi: 10.1038/35065638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frye RA. Characterization of five human cDNAs with homology to the yeast SIR2 gene: Sir2-like proteins (sirtuins) metabolize NAD and may have protein ADP-ribosyltransferase activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;260:273–279. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frye RA. Phylogenetic classification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic Sir2-like proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;273:793–798. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Imai S, Armstrong CM, Kaeberlein M, Guarente L. Transcriptional silencing and longevity protein Sir2 is an NAD-dependent histone deacetylase. Nature. 2000;403:795–800. doi: 10.1038/35001622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith JS, Brachmann CB, Celic I, Kenna MA, Muhammad S, Starai VJ, Avalos JL, Escalante-Semerena JC, Grubmeyer C, Wolberger C, Boeke JD. A phylogenetically conserved NAD+-dependent protein deacetylase activity in the Sir2 protein family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:6658–6663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.12.6658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Landry J, Slama JT, Sternglanz R. Role of NAD(+) in the deacetylase activity of the SIR2-like proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;278:685–690. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Landry J, Sutton A, Tafrov ST, Heller RC, Stebbins J, Pillus L, Sternglanz R. The silencing protein SIR2 and its homologs are NAD-dependent protein deacetylases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:5807–5811. doi: 10.1073/pnas.110148297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodgers JT, Lerin C, Haas W, Gygi SP, Spiegelman BM, Puigserver P. Nutrient control of glucose homeostasis through a complex of PGC-1alpha and SIRT1. Nature. 2005;434:113–118. doi: 10.1038/nature03354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nemoto S, Fergusson MM, Finkel T. SIRT1 functionally interacts with the metabolic regulator and transcriptional coactivator PGC-1{alpha} J Biol Chem. 2005;280:16456–16460. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501485200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brunet A, Sweeney LB, Sturgill JF, Chua KF, Greer PL, Lin Y, Tran H, Ross SE, Mostoslavsky R, Cohen HY, Hu LS, Cheng HL, Jedrychowski MP, Gygi SP, Sinclair DA, Alt FW, Greenberg ME. Stress-dependent regulation of FOXO transcription factors by the SIRT1 deacetylase. Science. 2004;303:2011–2015. doi: 10.1126/science.1094637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Motta MC, Divecha N, Lemieux M, Kamel C, Chen D, Gu W, Bultsma Y, McBurney M, Guarente L. Mammalian SIRT1 represses forkhead transcription factors. Cell. 2004;116:551–563. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00126-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daitoku H, Hatta M, Matsuzaki H, Aratani S, Ohshima T, Miyagishi M, Nakajima T, Fukamizu A. Silent information regulator 2 potentiates Foxo1-mediated transcription through its deacetylase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10042–10047. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400593101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pagans S, Pedal A, North BJ, Kaehlcke K, Marshall BL, Dorr A, Hetzer-Egger C, Henklein P, Frye R, McBurney MW, Hruby H, Jung M, Verdin E, Ott M. SIRT1 regulates HIV transcription via Tat deacetylation. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e41. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.North BJ, Marshall BL, Borra MT, Denu JM, Verdin E. The human Sir2 ortholog, SIRT2, is an NAD+-dependent tubulin deacetylase. Mol Cell. 2003;11:437–444. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Michishita E, Park JY, Burneskis JM, Barrett JC, Horikawa I. Evolutionarily Conserved and Nonconserved Cellular Localizations and Functions of Human SIRT Proteins. Mol Biol Cell. 2005 doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-01-0033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Onyango P, Celic I, McCaffery JM, Boeke JD, Feinberg AP. SIRT3, a human SIR2 homologue, is an NAD-dependent deacetylase localized to mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13653–13658. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222538099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwer B, North BJ, Frye RA, Ott M, Verdin E. The human silent information regulator (Sir)2 homologue hSIRT3 is a mitochondrial nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide-dependent deacetylase. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:647–657. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200205057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liszt G, Ford E, Kurtev M, Guarente L. Mouse Sir2 homolog SIRT6 is a nuclear ADP-ribosyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:21313–21320. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413296200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanner KG, Landry J, Sternglanz R, Denu JM. Silent information regulator 2 family of NAD- dependent histone/protein deacetylases generates a unique product, 1-O-acetyl-ADP-ribose. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:14178–14182. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250422697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sauve AA, Celic I, Avalos J, Deng H, Boeke JD, Schramm VL. Chemistry of gene silencing: the mechanism of NAD+-dependent deacetylation reactions. Biochemistry. 2001;40:15456–15463. doi: 10.1021/bi011858j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jackson MD, Denu JM. Structural identification of 2'- and 3'-O-acetyl-ADP-ribose as novel metabolites derived from the Sir2 family of beta -NAD+-dependent histone/protein deacetylases. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:18535–18544. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200671200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gray SG, Ekstrom TJ. The human histone deacetylase family. Exp Cell Res. 2001;262:75–83. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Denu JM. Linking chromatin function with metabolic networks: Sir2 family of NAD(+)-dependent deacetylases. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:41–48. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)00005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Borra MT, O'Neill FJ, Jackson MD, Marshall B, Verdin E, Foltz KR, Denu JM. Conserved enzymatic production and biological effect of O-acetyl-ADP-ribose by silent information regulator 2-like NAD+-dependent deacetylases. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:12632–12641. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111830200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rafty LA, Schmidt MT, Perraud AL, Scharenberg AM, Denu JM. Analysis of O-acetyl-ADP-ribose as a target for Nudix ADP-ribose hydrolases. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:47114–47122. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208997200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kustatscher G, Hothorn M, Pugieux C, Scheffzek K, Ladurner AG. Splicing regulates NAD metabolite binding to histone macroH2A. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:624–625. doi: 10.1038/nsmb956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liou GG, Tanny JC, Kruger RG, Walz T, Moazed D. Assembly of the SIR complex and its regulation by O-acetyl-ADP-ribose, a product of NAD-dependent histone deacetylation. Cell. 2005;121:515–527. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borra MT, Langer MR, Slama JT, Denu JM. Substrate specificity and kinetic mechanism of the Sir2 family of NAD+-dependent histone/protein deacetylases. Biochemistry. 2004;43:9877–9887. doi: 10.1021/bi049592e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bitterman KJ, Anderson RM, Cohen HY, Latorre-Esteves M, Sinclair DA. Inhibition of silencing and accelerated aging by nicotinamide, a putative negative regulator of yeast sir2 and human SIRT1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:45099–45107. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205670200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jackson MD, Schmidt MT, Oppenheimer NJ, Denu JM. Mechanism of nicotinamide inhibition and transglycosidation by Sir2 histone/protein deacetylases. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:50985–50998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306552200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sauve AA, Schramm VL. Sir2 regulation by nicotinamide results from switching between base exchange and deacetylation chemistry. Biochemistry. 2003;42:9249–9256. doi: 10.1021/bi034959l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bodanszky M. Principles of Peptide Synthesis. 2nd ed. Springer-Verlag; Germany: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Borra MT, Denu JM. Quantitative assays for characterization of the Sir2 family of NAD(+)-dependent deacetylases. Methods Enzymol. 2004;376:171–187. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)76011-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murray BW, Padrique ES, Pinko C, McTigue MA. Mechanistic effects of autophosphorylation on receptor tyrosine kinase catalysis: enzymatic characterization of Tie2 and phospho-Tie2. Biochemistry. 2001;40:10243–10253. doi: 10.1021/bi010959e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tanny JC, Moazed D. Coupling of histone deacetylation to NAD breakdown by the yeast silencing protein Sir2: Evidence for acetyl transfer from substrate to an NAD breakdown product. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:415–420. doi: 10.1073/pnas.031563798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oppenheimer NJ. The stereospecificity of pig brain NAD-glycohydrolase-catalyzed methanolysis of NAD. FEBS Lett. 1978;94:368–370. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(78)80979-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Min J, Landry J, Sternglanz R, Xu RM. Crystal structure of a SIR2 homolog-NAD complex. Cell. 2001;105:269–279. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00317-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chang JH, Kim HC, Hwang KY, Lee JW, Jackson SP, Bell SD, Cho Y. Structural basis for the NAD-dependent deacetylase mechanism of Sir2. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:34489–34498. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205460200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhao K, Chai X, Marmorstein R. Structure of the yeast Hst2 protein deacetylase in ternary complex with 2'-O-acetyl ADP ribose and histone peptide. Structure (Camb) 2003;11:1403–1411. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2003.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao K, Harshaw R, Chai X, Marmorstein R. Structural basis for nicotinamide cleavage and ADP-ribose transfer by NAD(+)-dependent Sir2 histone/protein deacetylases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8563–8568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401057101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Avalos JL, Boeke JD, Wolberger C. Structural basis for the mechanism and regulation of Sir2 enzymes. Mol Cell. 2004;13:639–648. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00082-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Avalos JL, Bever KM, Wolberger C. Mechanism of sirtuin inhibition by nicotinamide: altering the NAD(+) cosubstrate specificity of a Sir2 enzyme. Mol Cell. 2005;17:855–868. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kramers HA. Brownian motion in a field of force and the diffusion model of chemical reactions. Physica (The Hague) 1940;7:284–304. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brouwer AC, Kirsch JF. Investigation of diffusion-limited rates of chymotrypsin reactions by viscosity variation. Biochemistry. 1982;21:1302–1307. doi: 10.1021/bi00535a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blacklow SC, Raines RT, Lim WA, Zamore PD, Knowles JR. Triosephosphate isomerase catalysis is diffusion controlled. Appendix: Analysis of triose phosphate equilibria in aqueous solution by 31P NMR. Biochemistry. 1988;27:1158–1167. doi: 10.1021/bi00404a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hardy LW, Kirsch JF. Diffusion-limited component of reactions catalyzed by Bacillus cereus beta-lactamase I. Biochemistry. 1984;23:1275–1282. doi: 10.1021/bi00301a040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kurz LC, Weitkamp E, Frieden C. Adenosine deaminase: viscosity studies and the mechanism of binding of substrate and of ground- and transition-state analogue inhibitors. Biochemistry. 1987;26:3027–3032. doi: 10.1021/bi00385a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tarnus C, Muller HM, Schuber F. Chemical evidence in favor of a stabilized oxocarbonium-ion intermediate in the NAD+ glycohydrolase-catalyzed reactions. Bioorganic Chemistry. 1988;16:38–51. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Berthelier V, Tixier JM, Muller-Steffner H, Schuber F, Deterre P. Human CD38 is an authentic NAD(P)+ glycohydrolase. Biochem J. 1998;330(Pt 3):1383–1390. doi: 10.1042/bj3301383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Johnson RW, Marschner TM, Oppenheimer NJ. Pyridine nucleotide chemistry. A new mechanism for the hydroxide-catalyzed hydrolysis of the nicotinamide-glycosyl bond. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:2257–2263. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cakir-Kiefer C, Muller-Steffner H, Schuber F. Unifying mechanism for Aplysia ADP-ribosyl cyclase and CD38/NAD(+) glycohydrolases. Biochem J. 2000;349:203–210. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3490203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pascal M, Schuber F. The stereochemistry of calf spleen NAD-glycohydrolase-catalyzed NAD methanolysis. FEBS Lett. 1976;66:107–109. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(76)80596-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Muller-Steffner HM, Augustin A, Schuber F. Mechanism of cyclization of pyridine nucleotides by bovine spleen NAD+ glycohydrolase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:23967–23972. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.39.23967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yost DA, Anderson BM. Adenosine diphosphoribose transfer reactions catalyzed by Bungarus fasciatus venom NAD glycohydrolase. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:3075–3080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sauve AA, Munshi C, Lee HC, Schramm VL. The reaction mechanism for CD38. A single intermediate is responsible for cyclization, hydrolysis, and base-exchange chemistries. Biochemistry. 1998;37:13239–13249. doi: 10.1021/bi981248s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tanny JC, Dowd GJ, Huang J, Hilz H, Moazed D. An enzymatic activity in the yeast Sir2 protein that is essential for gene silencing. Cell. 1999;99:735–745. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81671-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Garcia-Salcedo JA, Gijon P, Nolan DP, Tebabi P, Pays E. A chromosomal SIR2 homologue with both histone NAD-dependent ADP-ribosyltransferase and deacetylase activities is involved in DNA repair in Trypanosoma brucei. Embo J. 2003;22:5851–5862. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Denu JM. The Sir2 family of protein deacetylases. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2005;9:431–440. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sauve AA, Deng H, Angeletti RH, Schramm VL. A covalent intermediate in CD38 is responsible for ADP-ribosylation and cyclization reactions. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:7855–7859. [Google Scholar]