Abstract

Current therapies for epilepsy are largely symptomatic and do not affect the underlying mechanisms of disease progression, i.e. epileptogenesis. Given the large percentage of pharmacoresistant chronic epilepsies, novel approaches are needed to understand and modify the underlying pathogenetic mechanisms. Although different types of brain injury (e.g. status epilepticus, traumatic brain injury, stroke) can trigger epileptogenesis, astrogliosis appears to be a homotypic response and hallmark of epilepsy. Indeed, recent findings indicate that epilepsy might be a disease of astrocyte dysfunction. This review focuses on the inhibitory neuromodulator and endogenous anticonvulsant adenosine, which is largely regulated by astrocytes and its key metabolic enzyme adenosine kinase (ADK). Recent findings support the “ADK hypothesis of epileptogenesis”: (i) Mouse models of epileptogenesis suggest a sequence of events leading from initial downregulation of ADK and elevation of ambient adenosine as an acute protective response, to changes in astrocytic adenosine receptor expression, to astrocyte proliferation and hypertrophy (i.e. astrogliosis), to consequential overexpression of ADK, reduced adenosine and – finally – to spontaneous focal seizure activity restricted to regions of astrogliotic overexpression of ADK. (ii) Transgenic mice overexpressing ADK display increased sensitivity to brain injury and seizures. (iii) Inhibition of ADK prevents seizures in a mouse model of pharmacoresistant epilepsy. (iv) Intrahippocampal implants of stem cells engineered to lack ADK prevent epileptogenesis. Thus, ADK emerges both as a diagnostic marker to predict, as well as a prime therapeutic target to prevent, epileptogenesis.

Keywords: adenosine, adenosine kinase, adenosine receptors, hippocampus, astrogliosis, status epilepticus, epileptogenesis, seizures, cell transplantation, transgenic mice

1. Introduction

Epilepsy is characterized by spontaneous recurrent seizures and represents one of the most frequent neurological diseases affecting about 60 million people worldwide (McNamara, 1999). It is estimated that up to 50% of all cases are triggered by “initial precipitating injuries”, such as status epilepticus (SE), stroke, and traumatic brain injury (TBI) (DeLorenzo et al., 2005; Hauser and Annegers, 1991; Hauser et al., 1991). The underlying pathophysiological process that is triggered by these and other initiating events and that transforms a healthy brain into an epileptic brain is termed epileptogenesis. This process involves changes in the equilibrium between excitatory and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) –ergic inhibitory neurotransmission, changes in ionotropic receptor function, alterations in calcium-homeostasis, or dysfunction of endogenous anticonvulsant or neuroprotective regulatory systems (DeLorenzo et al., 2007; Kohling, 2006). Consequently, currently used antiepileptic drugs largely act on neuronal and postsynaptic targets involved in the regulation of neurotransmission. This is also true for newer antiepileptic drugs, such as gabapentin and pregabalin, which have recently been demonstrated to act on the α2–δ subunit of a voltage-gated calcium channel, thus attenuating the calcium flux into neurons (Davies et al., 2007; Field et al., 2007; Taylor et al., 2007). Apart from dysfunction of neuronal networks (Holmes and Ben-Ari, 2003), dysfunction of astrocytes has recently emerged as a critical component of epileptogenesis adding an additional layer of complexity to the underlying disease process (Borges et al., 2006; Tian et al., 2005).

Current epilepsy therapies largely rely on pharmacotherapy or surgical intervention, both symptomatic strategies aimed at the suppression of seizures but not at the suppression of epileptogenesis (Loscher and Schmidt, 2004). Thus, to date no effective prophylaxis or true pharmacotherapeutic cure is available. In addition, the progression of epileptogenesis to chronic epilepsy often leads to pharmacoresistance and intractable seizures, which afflict up to 30% of all patients with epilepsy in particular those with temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE), the most prevalent form of refractory symptomatic epilepsy (Engel, 2001; Jallon, 1997). These patients are often severely disabled by their condition, have an unsatisfactory quality of life, and are at increased risk of sudden unexpected death. Thus, therapeutic strategies, which prevent or retard epileptogenesis and disease progression, would constitute a major therapeutic advance (Pitkanen and Halonen, 1998) with the goal to achieve seizure control without side effects. A prerequisite for the development of rational antiepileptogenic therapies is the understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying epileptogenesis. Based on rational consideration of these mechanisms several gene and cell therapies have been proposed making use of endogenous antiepileptic and antiepileptogenic compounds of the brain (Boison, 2007b; Noe et al., 2007). This review will critically evaluate dysfunction of the adenosine-based endogenous seizure control system (i) as a key component of epileptogenesis and (ii) as a rational target for therapeutic intervention aimed at the prevention of epilepsy.

2. Epileptogenesis

Whether hippocampal neuronal cell loss and/or hippocampal sclerosis is the cause or consequence of seizures has been a recurring question in human epilepsy research for more than a century. According to the current understanding of epileptogenesis three major phases are involved (Pitkanen, 2002; Pitkanen and Sutula, 2002): (i) the acute injury (e.g. status epilepticus, prolonged febrile seizures, stroke, or traumatic brain injury); (ii) a latent phase of epileptogenesis; and (iii) chronic epilepsy with spontaneous recurrent seizures. A major challenge in epilepsy research is to understand how the initial injury involved in the induction of epileptogenesis can produce long-term changes in neuronal excitability. Although different types of injuries may lead to epileptogenesis, some of the underlying mechanisms may still be the same. The search for such common pathways of epileptogenesis may thus provide the foundation for the development of novel antiepileptogenic and thus preventive therapies. A common consequence of brain injury is the development of an astrogliotic scar. Thus, reactive astrogliosis is the most prominent macroglial response to diverse forms of CNS injury (Pekny and Nilsson, 2005). In addition, astrogliosis is known to be a prominent feature of epileptic foci being evident in up to 90% of surgically resected epileptic hippocampi (Thom et al., 2002), and may play a causal role in the development of seizures and the persistence of seizure disorders (Khurgel and Ivy, 1996). Astrogliosis as seen in hippocampal sclerosis in TLE is considered to be a hallmark of epileptogenesis. Hippocampal sclerosis is characterized by intensive gliosis combined with a selective loss of neurons in the hippocampal formation. This includes loss of glutamatergic neurons in the granular and pyramidal cell layers of the hippocampal formation and the loss of inhibitory interneurons in the dentate hilus and the CA1 region. Neuronal cell loss and gliosis can spread to other components of the limbic system, such as amygdala or the entorhinal or perirhinal cortex (Wieser, 2004); in particular the loss of GABAergic interneurons is thought to contribute to the increased excitability of the epileptic hippocampus (Thompson et al., 1998).

Although the role of mossy fiber sprouting in epileptogenesis has been challenged (Elmer et al., 1997; Nissinen et al., 2001), in addition to astrogliosis, mossy fiber sprouting is one of the characteristic histopathological findings in TLE (Kharatishvili et al., 2006; Pitkanen et al., 2007; Represa et al., 1993; Sloviter et al., 2006; Sutula et al., 1988). The loss of normal postsynaptic targets of granule neurons may be the cause for mossy fiber sprouting, an hypothesis supported by findings that the degree of mossy fiber sprouting is correlated to the degree of neuronal cell loss (Cavazos and Cross, 2006). However, seizure-induced plasticity shows a different pattern of reorganization in the immature brain (Cross and Cavazos, 2007). In adult brain, sprouting mossy fibers grow aberrant collaterals into the inner molecular layer of the dentate gyrus, where they preferentially make synaptic contacts with dendrites of other granule neurons, leading to the formation of excitatory feedback circuits (Buckmaster et al., 2002; Scharfman et al., 2003).

2.1. The acute brain injury

Most experimental data regarding the pathophysiology of epileptogenesis have been obtained from studies, in which epileptogenesis was induced by status epilepticus (SE), which will be discussed in the following. It remains to be determined whether these mechanisms can be extrapolated to other triggers of epileptogenesis, such as stroke or traumatic brain injury. According to several studies, SE, induced by kainic acid (KA), pilocarpine, or electrical stimulation, is associated with hippocampal cell loss, particularly in the dentate hilus (Dudek et al., 2002; Pitkanen et al., 2002; Sutula, 2004). In a rat model of SE, evoked by electrical stimulation of the amygdala, hilar cell loss correlated positively with duration between SE and time point of analysis, but not with the number of spontaneous seizures occurring after SE (Pitkanen et al., 2002). Similar results were obtained in a related study on parahippocampal neuronal damage (Gorter et al., 2002). Most importantly, however, mossy fiber spouting does not appear to be necessary for spontaneous seizures to occur (Longo and Mello, 1998) and no correlation was found between mossy fiber sprouting and the quantity of seizures in a chronic seizure model of pilocarpine-induced SE (Longo and Mello, 1999). These experimental data have been confirmed in an analysis of 572 human resected MTLE specimens (Mathern et al., 2002). According to these studies an initial epileptogenesis precipitating injury was principally responsible for hippocampal neuronal loss, while late occurring recurrent limbic seizures may further damage the hippocampus. In addition, hippocampal sclerosis, the neuropathological hallmark of MTLE, was commonly (87%) preceded by an initial precipitating injury (Mathern et al., 2002). In summary, these studies suggest that an initial precipitating injury (e.g. SE) causes both acute neuronal cell loss and hippocampal sclerosis (i.e. astrogliosis).

2.2. Astrogliosis

Astrogliosis is a hallmark of the epileptic brain. Autopsy and surgical resection specimens have suggested that chronic temporal lobe epilepsy and post-traumatic seizures may originate from gliotic scars (Duffy and MacVicar, 1999; Rothstein et al., 1996; Tashiro et al., 2002). The involvement of astrocytes in the pathogenesis of epileptogenesis can no longer be ignored since recent findings that astrocytes control synaptic transmission by the vesicular release of glutamate, ATP, and by the release of the NMDA receptor co-agonist D-serine (Haydon and Carmignoto, 2006). The concept of the tripartite synapse (Araque et al., 1999; Halassa et al., 2007a) is based on findings showing that glia respond to neuronal activity with an elevation of their internal Ca2+ concentration, which in turn triggers the release of chemical transmitters from glia and thus causes feedback regulation of neuronal activity and synaptic strength. This is even more important, since one cortical astrocyte contacts approximately 300 to 600 neuronal dendrites, leading to “functional islands of synapses” in which a given set of synapses can be controlled by gliotransmitter release from one single astrocyte (Halassa et al., 2007b). These “local modules” appear to be integrated by neurotransmitter receptor crosstalk including receptor heteromerization (Ferre et al., 2007). Thus, enhanced or reduced gliotransmission might directly translate into neurological disease. Recently, it was demonstrated that prolonged episodes of neuronal depolarization evoked by astrocytic release of glutamate contributed to epileptiform discharges (Tian et al., 2005). This study provided support for the concept that astrocytes are involved in the initiation, maintenance and spread of seizures.

2.3. Chronic epilepsy

Among other histopathological changes, chronic epilepsy is largely characterized by selective neuronal cell loss, mossy fiber sprouting, and astrogliotic scar formation. This constellation obviously raises the chicken-and-egg-question, i.e. what is cause or consequence of chronic seizures, and challenges the traditional oversimplified concept, that chronic epilepsy is merely due to an imbalance of excitation and inhibition. Rather, the recruitment and synchronization of oscillatory networks is considered to be an emergent property of epileptic activity (Javitt and Coyle, 2004), which leaves open the question whether there might be a key regulator or endogenous inhibitor for the synchronization of neuronal networks. The concept of heterosynaptic depression was established 30 years ago by findings that high frequency stimulation of a particular excitatory pathway caused a depression of nearby pathways (Lynch et al., 1977). This could indeed be an endogenous mechanism to prevent synchronization of neuronal networks. Today it is well recognized that the purine ribonucleoside adenosine is the main messenger mediating heterosynaptic depression (Manzoni et al., 1994).

3. Neuromodulation by adenosine

Adenosine is an ubiquitous modulator of synaptic transmission and neuronal activity, exerting most of its functions via activation of the high-affinity inhibitory adenosine A1 and excitatory A2A receptors, while the low-affinity or low-abundance A2B and A3 receptors provide an additional layer of modulatory receptor crosstalk (Dunwiddie and Masino, 2001; Fredholm et al., 2005a; Fredholm et al., 2005b; Fredholm et al., 2001). Different affinities of these receptors for adenosine and highly specific spatial distribution patterns within the brain allow a high degree of complexity in the effects of adenosine and modulation of the action of other neurotransmitters or modulators (Cunha-Reis et al., 2007; Sebastiao and Ribeiro, 2000). Thus, adenosine controls many brain functions in physiological and pathophysiological conditions (Fredholm et al., 2005a; Fredholm et al., 2005b) and has potent anticonvulsant (Boison, 2005; Dragunow, 1986; Dunwiddie, 1999) and neuroprotective (Cunha, 2005; Dragunow and Faull, 1988; Ribeiro, 2005) properties. Due to these properties of adenosine, an adenosine-based pharmacopoeia has been established for a variety of conditions (Jacobson and Gao, 2006) including the development of adenosine-based cell therapies for the treatment of focal epilepsies (Boison, 2007a; 2007b).

3.1. Adenosine A1 receptors

Inhibitory neuromodulation by adenosine is largely mediated by activation of A1 receptors that are coupled to inhibitory Gi or Go containing G-proteins. These inhibit adenylyl cyclase, activate inwardly rectifying K+ channels, inhibit Ca2+ channels and activate phospholipase C. As a net result, the release of various neurotransmitters, in particular glutamate is inhibited by presynaptic A1 receptors. Consequently, adenosine and A1-selective receptor agonists are effective in seizure suppression (Boison, 2007a) and neuroprotection (Cunha, 2005). In addition to these synaptic effects, A1 receptors are believed to provide beneficial extra synaptic effects, which are based on a decrease in brain metabolism (Haberg et al., 2000) and the control of astrocyte function (van Calker and Biber, 2005). Tonic activation of A1 receptors by an endogenous tone of adenosine is believed to lead to long-distance A1 receptor mediated inhibition and thus to mediate heterosynaptic depression (Manzoni et al., 1994). In regard to epilepsy, A1 receptors, which have high expression levels in epilepsy-prone regions such as hippocampus (Fredholm et al., 2001), would thus be uniquely positioned to convey paracrine anticonvulsant functions of adenosine (Güttinger et al., 2005a; Güttinger et al., 2005b) and to prevent the spread of epileptogenic activity (Fedele et al., 2006; Kochanek et al., 2006).

3.2. Adenosine A2A receptors

In contrast to A1 receptors, A2A receptors are coupled to stimulatory Gs or Golf proteins (Dunwiddie and Masino, 2001) and both inhibitory as well as excitatory responses mediated via A2A receptors have been described in discrete brain areas (Fredholm et al., 2001). Inhibitors of the A2AR have profound neuroprotective functions (Cunha, 2005) and the capability to prevent apoptosis (Silva et al., 2007). In addition to regulating neuronal vulnerability, these receptors play a key role in modulating the action of other neurotransmitters and neuromodulators (Sebastiao and Ribeiro, 2000). In contrast to the global action of inhibitory A1 receptors the activity of A2A receptors appears to be locally restricted to active synapses (Ferre et al., 2005). Thus, stimulated nerve terminals can synaptically release ATP. This occurs preferentially at high frequency stimulation (Cunha et al., 1996b), and extracellular degradation of synaptically released ATP to adenosine is not associated with the activation of inhibitory A1, but with activation of facilitatory A2A receptors (Cunha et al., 1996a). Synaptic activation of A2A receptors can subsequently downregulate A1 receptors or its responses (Ciruela et al., 2006; Lopes et al., 1999). Thus, synaptic stimulation of A2A receptors under high frequency conditions in epileptic circuits could lead to downregulation of A1 receptors, a finding confirmed in chronic epilepsy (Ekonomou et al., 2000; Glass et al., 1996; Rebola et al., 2003). An additional layer of complexity in adenosine receptor function is created by heteromerization with each other (e.g. A1/A2A heteromers) and with other neurotransmitter receptors (e.g. A2A/D2 heteromers) (Fuxe et al., 2007). In summary, a shift in the A1 / A2A receptor ratio in chronic epilepsy, may reinforce the epileptic state and limit the therapeutic efficacy of adenosine-augmenting therapies. Nevertheless, augmentation of adenosine with an ADK inhibitor is very effective in preventing pharmacoresistant seizures in a mouse model of chronic MTLE (Gouder et al., 2004). These powerful therapeutic effects may be due to a global increase in adenosine, which is not restricted to the synapse, but able to exert predominantly inhibitory effects by activation of extra-synaptic A1Rs. Eventually, the combination of adenosine-augmentation with A2AR antagonism might be a preferable strategy for therapeutic intervention. In this regard, it needs to be mentioned that a safe A2AR antagonist KW-6002 is available and already in phase III clinical trials in patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease (Bara-Jimenez et al., 2003; Hauser et al., 2003).

3.3. Adenosine A2B and A3 receptors

Less is known about the contribution of the low-affinity A2B and the low-density A3 receptors to the regulation of epileptic circuits. While A1 and A2A receptors have important functions under physiological conditions, A2B and A3 receptors may be of relevance under pathological conditions. As an example, traumatic brain injury or cerebral ischemia lead to a massive surge in adenosine, elevating ambient levels of adenosine more than tenfold to levels sufficient to activate A2B and A3 receptors (Clark et al., 1997; Pearson et al., 2006). Recent findings suggest that the physiological consequences of A3 receptor activation show dose-dependent effects: While CA1 hippocampal A3 receptors stimulated by adenosine released during brief ischemia might exert A1 receptor-like protective effects on neurotransmission, severe ischemia (i.e. higher dose of adenosine) would transform the A3 receptor-mediated effects from protective to injurious (Maria Pugliese et al., 2007). In line with this notion, activation of A3 receptors led to heterologous desensitization of A1 receptors (Dunwiddie et al., 1997), and activation of A2A and A3 receptors by endogenous adenosine aggravated epileptic activity in slice cultures (Etherington and Frenguelli, 2004).

3.4. Pharmacological approaches for seizure suppression

Due to the widespread systemic distribution of adenosine receptors pharmacological approaches to antiepileptic therapy are limited by widespread systemic side effects including suppression of cardiovascular functions (Dunwiddie and Masino, 2001; Monopoli et al., 1994). While A1 receptor-selective antagonists exacerbate convulsions indicating that endogenous adenosine modulates epileptiform activity via the A1 receptor (Etherington and Frenguelli, 2004), A1 selective agents such as 2-chloro-N6-cyclopentyladenosine (CCPA) have previously been used to suppress seizures in various models of epilepsy (Huber et al., 2002; Monopoli et al., 1994). In addition, A1R agonists were shown to be effective in a mouse model of pharmacoresistant epilepsy, in which seizures could not be suppressed by conventional antiepileptic drugs (Gouder et al., 2003). The latter finding implies that augmentation of the adenosine system might be a general strategy for the treatment of otherwise refractory epilepsy. The potential of A2A receptor activation for seizure suppression has been investigated in only few studies and the results are partly controversial and seem to depend on the animal models and drugs used (De Sarro et al., 1999; Huber et al., 2002; Malhotra and Gupta, 1997; Zhang et al., 1994).

In addition, approaches involving the chronic activation of adenosine receptors by selective ligands may lead to rapid adaptive changes, thus limiting their clinical potential (Jacobson et al., 1996). The low blood brain barrier permeability and pronounced peripheral side effects of adenosine receptor agents (Malhotra and Gupta, 1997) constitute a significant limitation to their therapeutic use. Even the combination of the non-brain permeable non-selective adenosine receptor antagonist 8-sulfophenytheophylline with brain permeable selective adenosine receptor agonists failed to abolish centrally mediated sedative side effects in a rat model of audiogenic brain stem epilepsy (Huber et al., 2002). Therapeutically, it thus appears to be more reasonable to increase the extracellular level of adenosine by controlling its clearance or metabolism.

4. Regulation of endogenous adenosine

Due to the widespread distribution of adenosine receptors a tight regulation of endogenous levels of adenosine becomes a necessity. Extracellular and synaptic levels of adenosine are a function of adenosine formation, clearance and metabolism. As detailed below, recent evidence suggests that astrocytes play a key role in regulating the levels of endogenous extracellular adenosine (Boison, 2006; Haydon and Carmignoto, 2006), possibly by an adenosine cycle involving the vesicular release of ATP, extracellular degradation of ATP to adenosine, uptake of adenosine via nucleoside transporters and intracellular phosphorylation of adenosine to AMP.

4.1. Presynaptic vesicular release of ATP

Most cells in the brain, including neurons and astrocytes, can release ATP via regulated vesicular transport (Fields and Burnstock, 2006). Extracellular ATP is then cleaved into adenosine by a cascade of ectonucleotidases (Cunha, 2001; Zimmermann, 2000). The presynaptic release of ATP and its extracellular conversion to adenosine has important consequences for the modulation of synaptic transmission. Thus, ATP was preferentially released (and subsequently degraded to adenosine) upon high-frequency stimulation of hippocampal slices (Cunha et al., 1996b) leading to the preferential activation of excitatory A2A receptors (Cunha et al., 1996a); this mechanism allows the selective potentiation of high frequency bursts within a tonically inhibited network.

4.2. Astrocytic vesicular release of ATP

The elegant work of Phil Haydon’s group has recently identified vesicular release of ATP from astrocytes as a major source of extracellular adenosine under physiological conditions (Pascual et al., 2005). Transgenic overexpression of a dominant-negative form of synaptobrevin-2 selectively in astrocytes disrupted the vesicular release of ATP from astrocytes (Zhang et al., 2004). This manipulation led to the loss of the A1R mediated tonic inhibition in hippocampal slices (Pascual et al., 2005) indicating that under physiological conditions astrocytic release of ATP (and subsequent cleavage by ectonucleotidases) is a major source of extracellular adenosine. Since each astrocyte contacts thousands of synapses (Ventura and Harris, 1999), it is conceivable that astrocytic release of ATP has the function to set a global adenosine-mediated inhibitory tone within a neuronal network, while presynaptic release of ATP from neurons (see above) and its conversion to adenosine may have the function to selectively potentiate individual synaptic transmission within a globally inhibited network.

4.3. Nucleoside transporters

Since most nucleosides and their analogues are relatively hydrophilic and thus cannot readily pass the plasma membrane, nucleoside transporters are essential in adjusting extra- and intracellular adenosine levels (Cass et al., 1999). In addition, nucleoside transporters play an important role in the transport of antiviral nucleoside derivatives (Yamamoto et al., 2007). Human nucleoside transporters are classified into three known isoforms of concentrative nucleoside transporters (CNT) that are coupled to a Na+ gradient (Gray et al., 2004; Smith et al., 2007) and into four known isoforms of equilibrative nucleoside transporters (ENT), which rapidly equilibrate pools of extra- and intracellular adenosine (Baldwin et al., 2004). Under physiological conditions ENTs appear to play the predominant role in adjusting extra- and intracellular pools of adenosine in the brain, since the extracellular concentration of adenosine can be enhanced by inhibition of ENTs with dipyridamole, dilazep, nitrobenzylthioinosine, or cannabidiol (Carrier et al., 2006; Kong et al., 2004).

4.4. Control of extracellular adenosine by intracellular metabolism via adenosine kinase

As outlined above, under physiological conditions, astrocytic release of ATP and its extracellular degradation to adenosine appears to be the major source of extracellular synaptic adenosine, which is then rapidly equilibrated with the adenosine pool of intracellular compartments due to the ubiquitous expression of nucleoside transporters. Thus, intracellular metabolism of adenosine is uniquely suited to control the influx of adenosine into the cell and thus the levels of extracellular adenosine. Adenosine kinase (ADK, EC 2.7.1.20), which phosphorylates adenosine to 5’-AMP is considered to be the key metabolic enzyme for the regulation of extracellular adenosine levels in brain (Boison, 2006). Thus, inhibition, or genetic disruption, of ADK leads to rapid increases in extracellular adenosine (Fedele et al., 2004; Güttinger et al., 2005b; Huber et al., 2002), while overexpression of ADK leads to a reduction of the synaptic adenosine tone (Fedele et al., 2005). Alternative adenosine metabolizing enzymes such as adenosine deaminase or S-adenosyl-homocysteine hydrolase appear to play minor roles in the regulation of brain adenosine (Boison, 2006). Given the existence of an equilibrative transport system for adenosine, ADK fulfills the role of a metabolic reuptake system for adenosine, being the motor driving the influx of adenosine into the cell. The existence of a highly active substrate cycle between adenosine and AMP involving ADK and 5’-nucleotidase in brain allows minor changes in the activity of ADK to be translated rapidly into major changes in ambient adenosine (Arch and Newsholme, 1978; Bontemps et al., 1983). Thus, hypoxia-induced inhibition of ADK potentiated cardiac adenosine release (Decking et al., 1997), and pharmacological inhibition of ADK increased endogenous adenosine and depressed neuronal activity in hippocampal slices (Pak et al., 1994). Since intracellular ATP levels are about 100,000 times higher than respective adenosine levels (Fredholm et al., 2005a), modulation of ADK activity will translate rapidly into changes in adenosine, but will not influence levels of ATP. Likewise, ADK will not influence the de novo synthesis of purines, which is dependent on the formation of IMP as a common precursor of AMP and GMP.

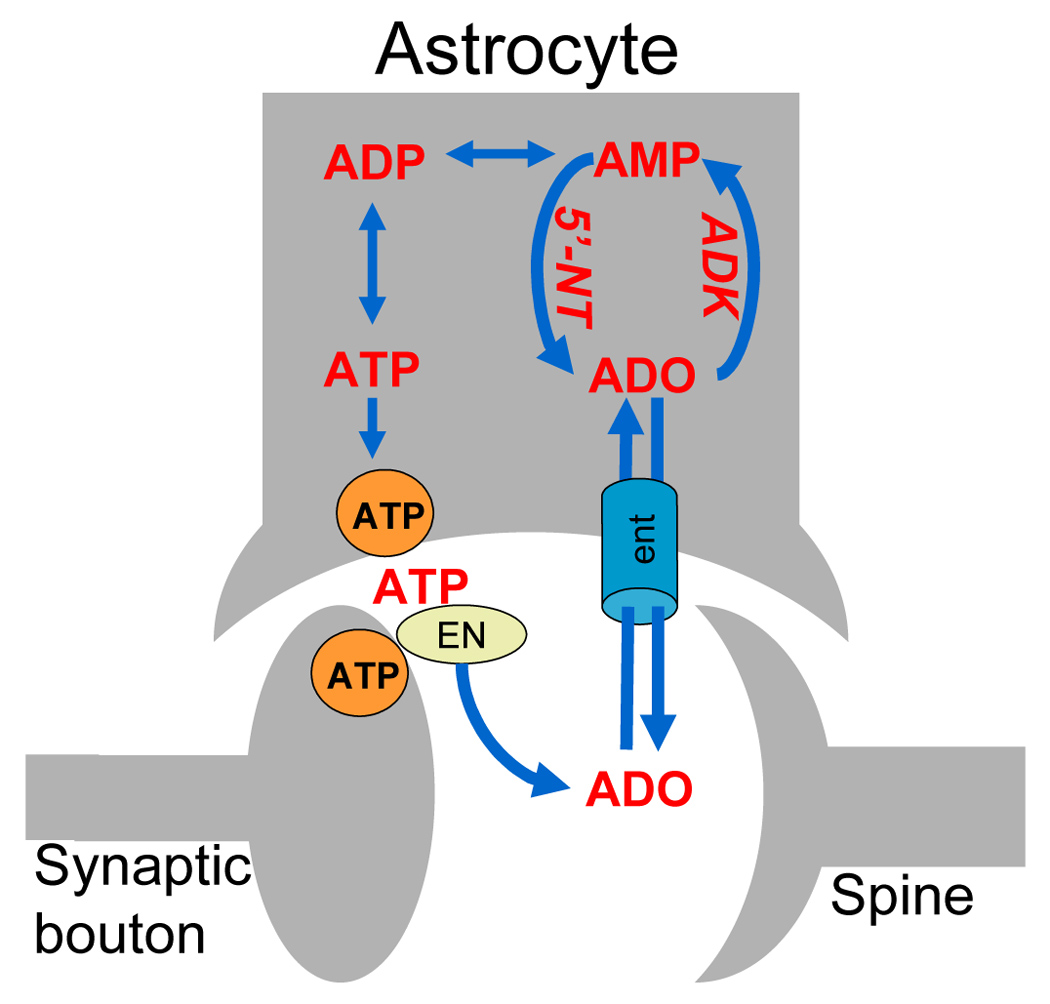

Most importantly, in adult brain, ADK is almost exclusively expressed in astrocytes (Studer et al., 2006). Given the astrocytic synaptic release of ATP as a major source of adenosine, an astrocyte-based adenosine-cycle becomes plausible (Fig. 1). Thus synaptic concentrations of adenosine are dependent on astrocytic release of ATP, extracellular cleavage by ectonucleotidases into adenosine, and ADK-driven reuptake via nucleoside transporters. This implies that astrocytes play a prominent role in setting the inhibitory adenosine tone, which is of importance in setting the thresholds for seizure susceptibility.

Fig. 1.

Components of the astrocyte-based adenosine cycle. Under physiological conditions a major source of synaptic adenosine is vesicular release of ATP (orange circle) from astrocytes followed by its extracellular degradation to adenosine (ADO) by a cascade of ectonucleotidase (EN). Under conditions of high-frequency stimulations neurons contribute to synaptic ATP release. Extra- and intracellular levels of adenosine are rapidly equilibrated, mainly by equilibrative nucleoside transporters (ent). Thus, synaptic concentrations of adenosine are largely dependent on its intracellular metabolism as the driving force for the influx of adenosine into the cell. Intracellular metabolism of adenosine (ADO) is depends on the activity of the astrocytic enzyme adenosine kinase (ADK), which, together with 5’-nucleotidase (5’-NT), forms a substrate cycle between AMP and adenosine. This substrate cycle is directly linked to the energy pool of the brain involving ADP and ATP. Under conditions of astrogliosis, ADK is overexpressed leading to an increased influx of adenosine into the astrocyte and therefore to reduced levels of synaptic adenosine favoring the development of spontaneous seizures. Conversely, inhibition of ADK or inhibition of nucleoside transporters can be used to increase synaptic adenosine and thus to suppress seizures.

5. Insights from mouse models of epileptogenesis

The expression of ADK is characterized by striking plasticity. Remarkably, enzyme expression undergoes a coordinated switch from neuronal to astrocytic expression during the early postnatal development of the mouse brain (Studer et al., 2006); thus high neuronal ADK expression in the developing brain may explain the heightened seizure susceptibility of infants (Studer et al., 2006). Most importantly, ADK expression undergoes acute and chronic changes in response to various stress factors.

5.1. Biphasic regulation of adenosine kinase expression

As an acute response to stress (e.g. SE, ischemia, brain injury) ADK is rapidly downregulated leading to elevated levels of adenosine, thus enhancing the protective functions of the adenosine system via increased activation of A1Rs. Thus, the induction of ischemia in hippocampal slices led to the rapid increase in extracellular adenosine within 10 min to levels >20 µM above baseline (Pearson et al., 2006). This rapid rise of adenosine was demonstrated to be due to the release of adenosine as such and was not dependent on extracellular cleavage of ATP (Frenguelli et al., 2007). In line with these findings, oxygen-glucose deprivation in cultured cortical neurons led to downregulation of ADK and rapid rise in extracellular adenosine, which was maintained for at least one hour (Lynch et al., 1998). In vivo, ADK was downregulated within 2 hours after SE in mice (Gouder et al., 2004) and within 3 hours after middle cerebral artery occlusion in a mouse model of stroke (Pignataro et al., 2007a). In these in vivo models downregulation of ADK was transient, reaching back to normal levels within 24 hours (Gouder et al., 2004; Pignataro et al., 2007a). Downregulation of ADK was also demonstrated as a consequence of seizure preconditioning in a recent gene expression study (Borges et al., 2007). Thus, acute downregulation of ADK and the resulting increase in extracellular adenosine might be a general astrocyte-based protective mechanism of the brain.

Conversely, under conditions of chronic epilepsy, ADK was found to be upregulated. Thus, kainic acid-induced SE led to a 1.8 fold increase in hippocampal ADK activity and spontaneous seizures within a time frame of four weeks (Gouder et al., 2004). Otherwise pharmacoresistant seizures in this mouse model (Gouder et al., 2003) could be suppressed by application of the ADK inhibitor 5-iodotubercidin (3.1 mg/kg, i.p.); 5-iodotubercidin-mediated seizure suppression was abolished by co-application of the A1R antagonist DPCPX. These findings demonstrate that upregulation of ADK in chronic epilepsy is implicated in epileptogenesis by reducing the adenosine tone at the A1R. Upregulation of ADK was also found in chronically kindled rats and in the rat pilocarpine model of epilepsy (D. Boison, unpublished observations). Upregulation of ADK in chronic epilepsy is paralleled by changes in G-protein coupled receptor expression such as downregulation of A1Rs (Ekonomou et al., 2000; Rebola et al., 2003; Rebola et al., 2005), reorganization of cannabinoid type 1 receptors (Falenski et al., 2007), or increases in GABAB receptor expression (Kokaia et al., 2001; Morimoto et al., 2004).

In summary, ADK expression undergoes a biphasic regulation during epileptogenesis, with acute downregulation after injury (e.g. after SE) but upregulation in chronic epilepsy. Since in adult brain ADK is primarily an astrocytic enzyme, astrogliosis is likely the culprit for enhanced ADK expression in chronic epilepsy. How does the biphasic regulation of ADK expression relate to astrogliosis during epileptogenesis?

5.2. Astrogliosis

Several lines of evidence indicate that increased levels of adenosine may promote or trigger astrogliosis, an effect that appears to be largely mediated by A2ARs. Thus, activation of the A2AR potentiates synaptic actions of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in the hippocampus (Diogenes et al., 2007), stimulates glutamate outflow and leads to excessive glial activation (Popoli et al., 2007). In rat cortex, micro-infusion of the potent A2AR agonist 5′-(N-cyclopropyl)-carboxamidoadenosine (CPCA) increased astrogliosis, an effect that was abolished by co-infusion of the adenosine A2AR antagonist 1,3-dipropyl-7-methylxanthine (DPMX) (Hindley et al., 1994). Likewise, A2AR blockade abolished basic fibroblast growth factor-induced reactive gliosis in rat striatal primary astrocytes (Brambilla et al., 2003). These findings nicely demonstrate that A2AR stimulation promotes astrogliosis. Thus, it is compelling to conclude that under conditions of brain injury, hypoxia, or inflammation, which all cause both upregulation of A2ARs (Cunha, 2005) as well as acute increase in adenosine (Dunwiddie and Masino, 2001), an adenosine-based mechanism contributes to astrogliosis. This notion is further supported by findings that stimulation of A1Rs, which are downregulated during epileptogenesis (Ekonomou et al., 2000; Rebola et al., 2003; Rebola et al., 2005), leads to a reduction of astrocyte proliferation (Rathbone et al., 1991).

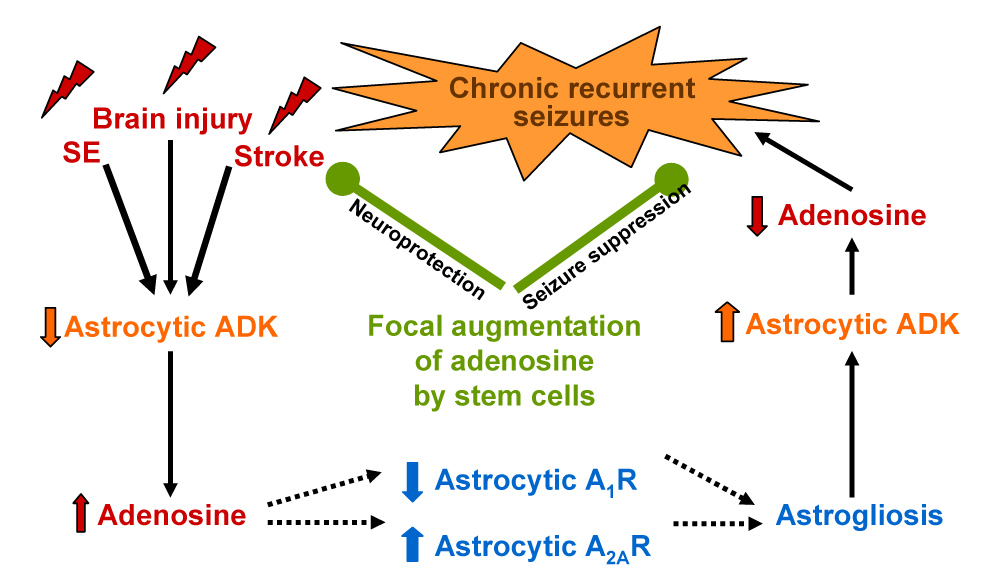

5.3. Hippocampal upregulation of adenosine kinase and hippocampal seizures

The arguments described above thus support the ADK hypothesis of epileptogenesis (Fig. 2): A variety of acute insults to the brain including brain injury, SE, and ischemic stroke lead to a homotypic brain response consisting of acute downregulation of ADK, rapid increase in extracellular adenosine, downregulation of A1Rs and upregulation of A2ARs, which in turn regulate astrocyte proliferation. Thus, as a consequence of acute downregulation of ADK, astrogliosis results. As described above, astrogliosis in a mouse model of kainic acid induced hippocampal epileptogenesis correlated with a 1.8-fold upregulation of ADK activity and spontaneous non-convulsive intrahippocampal partial seizures (Gouder et al., 2004). Importantly, spontaneous seizures were restricted to the kainic-acid injured astrogliotic hippocampus displaying upregulation of ADK, while generalized seizures were not detected using cortical electrodes (Gouder et al., 2004). These findings imply that spontaneous seizures “co-localized” to upregulated ADK, but also that seizures did not spread to other brain regions. It is important to note that activation of A1Rs by ambient adenosine prevents the spread of seizures (Fedele et al., 2006); thus, normal adenosine levels in non-astrogliotic brain regions are expected to prevent the spread of focal seizures, which are possible only within the context of upregulated ADK (Fig. 3) (= reduced adenosine). The experiments described above suffered somewhat from the rather diffuse hippocampal upregulation of ADK in this model (Gouder et al., 2004).

Fig. 2.

The adenosine kinase hypothesis of epileptogenesis. Downregulation of adenosine kinase (ADK) within 2 to 3 hours results as a homotypic response to various types of brain injury including status epilepticus and stroke. Reduced ADK leads to an increase of extracellular adenosine (see Fig. 1). Under conditions of elevated adenosine, astrocytic A1Rs are downregulated, whereas upregulation of astrocytic A2ARs occurs. Since astrocyte proliferation is in part dependent on the relative expression levels of A1Rs (inhibition of cell proliferation) and A2ARs (promotion of cell proliferation), the adenosine-induced shift of the A1/A2A-equilibrium may cause astrogliosis. Astrogliosis in turn leads to upregulation of ADK, and thus results in a decrease of the endogenous anticonvulsant adenosine: spontaneous recurrent seizures result. Potential therapeutic effects of adenosine-releasing stem cell derived brain implants are shown in green. Focal augmentation of adenosine by these implants may prevent epileptogenesis based on the potent neuroprotective and anticonvulsant properties of adenosine.

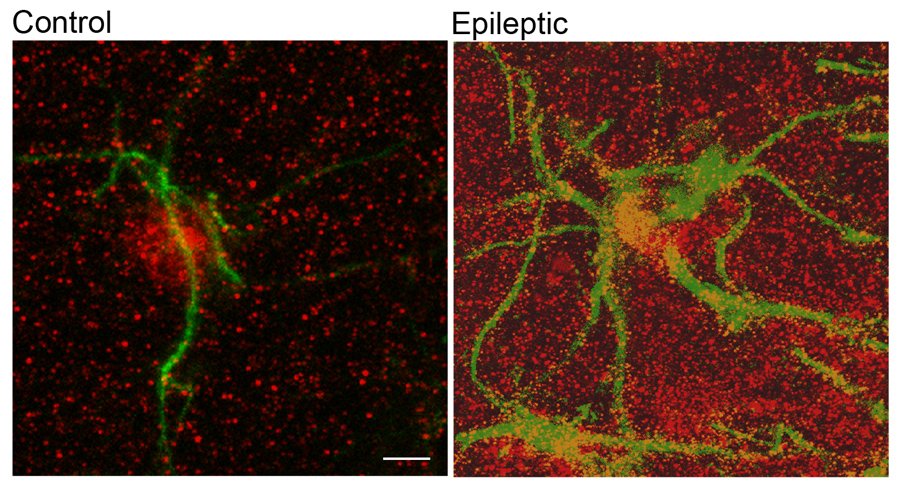

Fig. 3.

Astrogliosis and upregulation of ADK in epilepsy. Left panel: Confocal image taken from untreated mouse (control) hippocampus showing the fine processes of a single astrocyte stained for GFAP immunoreactivity in green. ADK immunoreactivity in red shows a predominant location of ADK in the nucleus and cell body of this astrocyte. Right panel: In contrast, the epileptic mouse hippocampus, when analyzed three weeks after status epilepticus, is characterized by astrogliosis as seen by the hypertrophied and enlarged processes of several astrocytes (GFAP in green) and profound increase and redistribution of ADK immunoreactivity (in red).Scale bar: 5µm.

More recently a co-localization of astrogliosis, upregulation of ADK and spontaneous electrographic seizures were described at high spatial resolution in a novel mouse model of CA3-restricted epileptogenesis (Li et al., 2007a): C57BL/6 wild-type mice received intraamygdaloid injections of kainic acid (KA), which triggered SE (terminated after 30 min with lorazepam) and subsequent neuronal cell loss restricted to the ipsilateral CA3 region. During a time span of 3 weeks astrogliosis developed together with upregulation of ADK, all restricted to the ipsilateral CA3. Most importantly, spontaneous electrographic seizures at a frequency of around 4 seizures per hour developed exclusively within the ipsilateral CA3, but were not recorded elsewhere (CA1, dentate gyrus, cortex). This experiment demonstrates high special colocalization of spontaneous electrographic seizures with astrogliosis and upregulated ADK, and suggests that astrogliosis and/or upregulation of ADK contribute to epileptogenesis.

6. Seizure susceptibility in adenosine kinase transgenic mice

To answer the question whether astrogliosis or upregulation of ADK is the primary cause for epileptogenesis, transgenic mice were created with altered levels of ambient adenosine due to either reduction or overexpression of ADK. Global genetic disruption of ADK led to hepatic steatosis and perinatal lethality (Boison et al., 2002b) precluding any further studies of epileptogenesis. However, mutant mice overexpressing transgenic ADK in an ADK-deficient background (Adk-tg) have been generated recently (Fedele et al., 2005). Due to the lack of endogenous ADK, adenosine levels in these mice are exclusively under the control of a loxP flanked transgenic ADK, which is overexpressed in brain and exhibits a novel expression of ADK in neurons, particularly in the hippocampal CA3 region (Fedele et al., 2005). A reduced tone of ambient adenosine was demonstrated in brain slices derived from Adk-tg mice. Thus, increased pictrotoxin-induced seizure activity, as well as the lack of changes in the EPSP response after pharmacological blockade of the A1R in mossy fiber CA3 synapses, was consistent with a reduction in hippocampal adenosine levels. Concordantly, A1R dependent adenosine-mediated inhibition of the EPSP amplitude could be restored by inhibition of ADK (Fedele et al., 2005). As a result of the mutation and reduced levels of protective adenosine, the animals exhibit aggravated cell death in ischemia (Pignataro et al., 2007b). Most notably, transgenic overexpression of ADK in CA3 was associated with spontaneous electrographic CA3 seizures – and this in the absence of astrogliosis – at a frequency of 4.8 ± 1.5 seizures per hour with each seizure lasting 26.7 ± 13.2 seconds. Remarkably, CA3 seizures in Adk-tg mice were highly similar to CA3 seizures in KA treated epileptic mice (4.3 ± 1.5 seizures per hour, each lasting 17.5 ± 5.8 seconds (Li et al., 2007a). It is important to note that in mutant animals only modest increases in forebrain ADK (147% of normal) were sufficient to elicit spontaneous seizures (Li et al., 2007a). This correlates well with the 1.8-fold increase of ADK activity in hippocampi of kainic acid treated epileptic mice (Gouder et al., 2004). These findings imply that tight regulation of adenosine levels by ADK is a necessity and that moderate overexpression of ADK is sufficient to induce seizures.

If overexpression of ADK is sufficient to induce spontaneous seizures, then reduction of ADK in engineered mice should prevent epileptogenesis. The generation of mice with moderately reduced levels of ADK in brain rather than complete ADK deficiency seems to be essential, since several lines of evidence suggest that only small changes in ADK levels are permissible: (i) The homozygous disruption of ADK is lethal (Boison et al., 2002b); (ii) ADK is highly conserved in evolution (Spychala et al., 1996), suggesting that mutations are not easily tolerated; (iii) No mutations of human ADK are known in man (OMIM, Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man, Victor A. McKusick et al., Johns Hopkins University) indicating that most mutations are lethal; (iv) Excessive levels of ADK lead to severe deficits in A1R activation and to lethal status epilepticus or cell death after otherwise non-lethal triggers (Fedele et al., 2006; Kochanek et al., 2006; Li et al., 2007a; Pignataro et al., 2007b); (v) Inadequate levels of ADK in brain are expected to lead to a rise in adenosine to unacceptably high levels, with likely lethal consequences, e.g. central apnea and perinatal mortality induced by elevated adenosine (Montandon et al., 2006). Therefore a new mouse line (fb-Adk-def) was generated with a moderate reduction of ADK (62% of normal) restricted to the forebrain (Li et al., 2007a). This was achieved by breeding Adk-tg mice, which contain a loxP-flanked ubiquitously expressed Adk transgene, with Emx1-Cre-tg3 mice (Iwasato et al., 2004), yielding a forebrain selective excision of the transgene in most cells (except GABAergic interneurons). As expected, fb-Adk-def mice were resistant to KA-induced SE and subsequent neuronal cell loss (Li et al., 2007a). However, when intraamygdaloid injection of KA was paired with the A1 receptor antagonist DPCPX, wild-type like SE and corresponding CA3 selective neuronal cell loss (i.e. trigger for subsequent epileptogenesis) could be restored. However, despite the presence of the epileptogenesis triggering acute injury DPCPX-treated fb-Adk-def mice were resistant to subsequent epileptogenesis. Neither astrogliosis, nor upregulation of ADK, nor spontaneous seizures were found three weeks after CA3 injury (Li et al., 2007b). These studies demonstrate that epileptogenesis was prevented by reduced levels of ADK.

7. Adenosine-releasing stem cell-derived brain implants prevent epileptogenesis

As outlined above, seizure susceptibility is increased under conditions of elevated ADK and reduced adenosine (either in the context of astrogliosis or via transgenic ADK). Conversely, reconstitution of the adenosine system should suppress seizures in established epilepsy but should also prevent epileptogenesis. Ample evidence has been provided for the seizure suppressive potential of adenosine releasing cell transplants (Boison, 2007a; 2007b). In these studies, kindled seizures in the rat could be suppressed by intraventricular implants of encapsulated fibroblasts, myoblasts or stem cells engineered to release adenosine based on disruption of the Adk gene (Boison et al., 2002a; Güttinger et al., 2005a; Güttinger et al., 2005b; Huber et al., 2001). These studies demonstrated that the focal paracrine release of adenosine is sufficient to suppress seizures (Güttinger et al., 2005a), that implant efficacy is not compromised by receptor desensitization (Güttinger et al., 2005b), and that focal delivery of adenosine in contrast to systemic activation of A1Rs or systemic inhibition of ADK is not accompanied by sedative side effects (Güttinger et al., 2005b). These studies also demonstrated that rather small doses of adenosine in the nanomolar range, when delivered locally, are sufficient to suppress seizures (Huber et al., 2001). However, cell encapsulation limited the long-term viability of this first generation of adenosine-releasing therapeutic cells (Boison, 2007a).

A more versatile cellular delivery system for adenosine was generated by engineering mouse embryonic stem cells to lack both alleles of Adk (Fedele et al., 2004). Using a step-wise differentiation protocol (Okabe et al., 1996) Adk−/− ES cells were differentiated into transplantable adenosine releasing neural precursor cells. These cells were highly effective in reducing stroke-induced brain injury in a mouse model of middle cerebral artery occlusion (Pignataro et al., 2007c). In a more recent approach Adk−/− ES cell derived neural precursor cells were transplanted into the infrahippocampal cleft of rats one week prior to the onset of hippocampal kindling (Li et al., 2007b). In contrast to wild-type graft recipients and sham-treated control animals, Adk−/− graft recipients were characterized by a profound reduction of kindling induced epileptogenesis (Li et al., 2007b). Even after 48 kindling stimulations, recipients of adenosine releasing cells did not develop generalized stage 4 and 5 seizures, while generalized seizures in control animals first occurred around the 30th stimulation. These results, obtained in the rat hippocampal-kindling model, suggest a powerful antiepileptogenic effect achieved by focal augmentation of the adenosine system. The rat kindling model is widely considered to be a model of epileptogenesis, and therapies, which suppress kindling-development, have predictive value for antiepileptogenic effects (Lothman and Williamson, 1994; McNamara et al., 1985; Racine, 1978). On the other hand the kindling model is a simplified model of epileptogenesis and does not reflect all histopathological changes observed in human TLE, which develop over months to years, while kindling epileptogenesis develops over weeks.

The potential of Adk−/− ES cell derived neural precursors (NPs) to prevent epileptogenesis has recently been further substantiated in the mouse model of CA3 selective epileptogenesis (Li et al., 2007a). Adk−/− ES derived NPs were transplanted into the infrahippocampal cleft of mice 24 hours after intraamygdaloid KA-injection. At this time point the animals already had the epileptogenesis triggering CA3 selective injury. However, in contrast to wild-type graft recipients or sham-treated control animals Adk−/− NP recipients did not develop spontaneous seizures. Remarkably, when analyzed 3 weeks after transplantation, astrogliosis was significantly reduced, but most importantly ADK expression levels were close to normal (Li et al., 2007a). These data further support the conclusion that ADK deficient brain implants have the potential to prevent epileptogenesis.

In an effort to engineer human stem cells for therapeutic adenosine release, human mesenchymal stem cells were engineered to release adenosine based on lentiviral expression of an miRNA directed against ADK. Human mesenchymal stem cell grafts with a knockdown of ADK significantly reduced acute brain injury and duration of SE in a mouse model of KA-induced epileptogenesis (Ren et al., 2007). Since epileptogenesis in patients is not a completed pathophysiological state, but rather a dynamic process leading to progressively increasing frequency and severity of seizures, to pharmacoresistance and eventually to cognitive deficits (Blumcke et al., 2002; Elger et al., 2004; Engel, 2002), the time course of disease progression might provide a sufficient time window for therapeutic augmentation of the adenosine system to prevent the progression of the disease.

8. Adenosine in human epilepsy

The ADK hypothesis of epileptogenesis presented here is largely based on rodent models of ictogenesis and epileptogenesis. Clinical data in support of this hypothesis are still limited though several studies are worth mentioning. Microdialysis studies performed in patients with intractable complex partial epilepsy have demonstrated that following a seizure, extracellular adenosine levels increased 6- to 31-fold with the increase significantly greater in the epileptogenic hippocampus (During and Spencer, 1992). Likewise, adenosine metabolites were increased in cerebrospinal fluid following SE (Chin et al., 1995). These findings led to the concept that adenosine is an endogenous mediator of seizure arrest and postictal refractoriness (During and Spencer, 1992). Remarkably, and in agreement with upregulated ADK in epileptogenic hippocampus, in these studies basal adenosine levels sampled before the onset of seizures were lower in the epileptogenic hippocampus compared to the non-epileptic hippocampus (During and Spencer, 1992). Findings on A1R expression in human temporal lobe epilepsy are controversial; both down- and upregulation of A1R have been described (Angelatou et al., 1993; Glass et al., 1996). More recent findings from human studies suggest energetic dysfunction and mitochondrial dysfunction to be implicated in epileptogenesis (Kunz, 2002; Pan et al., 2005; Williamson et al., 2005). Although not further addressed in these studies, energetic and mitochondrial dysfunction may be directly linked to adenosine, which has been described as a retaliatory metabolite adjusting energy consumption to energy supplies (Newby et al., 1985). A recent study used the purinergic drug allopurinol as adjunctive therapy in a double-blind and placebo-controlled trial in intractable epilepsy (Togha et al., 2007). This study demonstrated increased seizure reduction in the allopurinol group compared to control; however data were statistically significant only after 4 months of treatment, and allopurinol-induced side effects were common. Despite these caveats this study demonstrates that modulation of the purinergic system might be beneficial in intractable epilepsy.

9. Conclusions

Several lines of evidence have been established, which support the adenosine kinase hypothesis of epileptogenesis, which is based on a sequence of events leading from acute brain injury to initial downregulation of ADK, rise in extracellular adenosine, changes in astrocytic adenosine receptor expression, increased proliferation and hypertrophy of astrocytes (i.e. astrogliosis), astrogliotic upregulation of ADK, reduction of the endogenous anticonvulsant adenosine, and finally to the generation of spontaneous seizures: (i) ADK is the key enzyme for regulation of the endogenous anticonvulsant adenosine (Boison, 2006). (ii) In adult brain ADK is predominantly expressed in astrocytes (Studer et al., 2006). (iii) Astrogliosis is a hallmark of epilepsy (Duffy and MacVicar, 1999; Rothstein et al., 1996; Tashiro et al., 2002). (iv) ADK is upregulated in astrogliotic hippocampus, contributing to spontaneous seizures via reduction of the adenosine tone (Gouder et al., 2004). (v) Transgenic overexpression of ADK leads to spontaneous seizures (Fedele et al., 2005) and increased neuronal vulnerability (Pignataro et al., 2007b). (vi) Pharmacological inhibition of ADK prevents otherwise pharmacoresistant seizures in mice (Gouder et al., 2003; Gouder et al., 2004). (vii) Mice with a forebrain selective reduction of Adk are resistant to epileptogenesis (Li et al., 2007a) (viii) Augmentation of the adenosine system by brain implants of stem cells engineered to release adenosine has the potential to prevent epileptogenesis in at least two animal models (rat kindling model and mouse intraamygdaloid KA model).

In conclusion, ADK has emerged as a novel target to predict and to prevent epileptogenesis. Thus, high levels of ADK expression (e.g. as a long-term consequence of traumatic brain injury) are expected to be predictive for subsequent epileptogenesis. This means that the determination of ADK expression levels in brain, e.g. by using ADK-selective PET or SPECT ligands, has high diagnostic value. On the other hand, prevention of epileptogenesis by focal reconstitution of the adenosine system is an important therapeutic goal. This could be achieved by focal brain implants of adenosine releasing cells or by RNAi- based gene therapies aimed at downregulating the astrogliotic overexpression of ADK during disease progression.

Acknowledgments

The work of the author was supported by grant R01 NS047622-01 from the NIH, by the Good Samaritan Hospital Foundation and by the Epilepsy Research Foundation through the generous support of Arlene & Arnold Goldstein Family Foundation.

Abbreviations

- ADK

adenosine kinase

- AR

adenosine receptor

- CNT

concentrative nucleoside transporters

- ENT

equilibrative nucleoside transporters

- GABA

γ-aminobutyric acid

- KA

kainic acid

- MTLE

mesial temporal lobe epilepsy

- SE

status epilepticus

- TBI

traumatic brain injury

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Angelatou F, Pagonopoulou O, Maraziotis T, Olivier A, Villemeure JG, Avoli M, Kostopoulos G. Upregulation of A1 adenosine receptors in human temporal lobe epilepsy: a quantitative autoradiographic study. Neurosci Lett. 1993;163:11–14. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90217-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araque A, Parpura V, Sanzgiri RP, Haydon PG. Tripartite synapses: glia, the unacknowledged partner. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:208–215. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01349-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arch JR, Newsholme EA. Activities and some properties of 5′-nucleotidase, adenosine kinase and adenosine deaminase in tissues from vertebrates and invertebrates in relation to the control of the concentration and the physiological role of adenosine. Biochem J. 1978;174:965–977. doi: 10.1042/bj1740965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin SA, Beal PR, Yao SY, King AE, Cass CE, Young JD. The equilibrative nucleoside transporter family, SLC29. Pflugers Arch. 2004;447:735–743. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1103-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bara-Jimenez W, Sherzai A, Dimitrova T, Favit A, Bibbiani F, Gillespie M, Morris MJ, Mouradian MM, Chase TN. Adenosine A(2A) receptor antagonist treatment of Parkinson's disease. Neurology. 2003;61:293–296. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000073136.00548.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumcke I, Thom M, Wiestler OD. Ammon's horn sclerosis: a maldevelopmental disorder associated with temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain Pathol. 2002;12:199–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2002.tb00436.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boison D. Adenosine and epilepsy: from therapeutic rationale to new therapeutic strategies. Neuroscientist. 2005;11:25–36. doi: 10.1177/1073858404269112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boison D. Adenosine kinase, epilepsy and stroke: mechanisms and therapies. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:652–658. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boison D. Adenosine-based cell therapy approaches for pharmacoresistant epilepsies. Neurodegener Dis. 2007a;4:28–33. doi: 10.1159/000100356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boison D. Cell and gene therapies for refractory epilepsy. Current Neuropharmacology. 2007b;5:115–125. doi: 10.2174/157015907780866938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boison D, Huber A, Padrun V, Deglon N, Aebischer P, Mohler H. Seizure suppression by adenosine-releasing cells is independent of seizure frequency. Epilepsia. 2002a;43:788–796. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.33001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boison D, Scheurer L, Zumsteg V, Rülicke T, Litynski P, Fowler B, Brandner S, Mohler H. Neonatal hepatic steatosis by disruption of the adenosine kinase gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002b;99:6985–6990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092642899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bontemps F, Van den Berghe G, Hers HG. Evidence for a substrate cycle between AMP and adenosine in isolated hepatocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80:2829–2833. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.10.2829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges K, McDermott D, Irier H, Smith Y, Dingledine R. Degeneration and proliferation of astrocytes in the mouse dentate gyrus after pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus. Experimental Neurology. 2006;201:416–427. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges K, Shaw R, Dingledine R. Gene expression changes after seizure preconditioning in the three major hippocampal cell layers. Neurobiol Dis. 2007;26:66–77. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brambilla R, Cottini L, Fumagalli M, Ceruti S, Abbracchio MP. Blockade of A2A adenosine receptors prevents basic fibroblast growth factor-induced reactive astrogliosis in rat striatal primary astrocytes. Glia. 2003;43:190–194. doi: 10.1002/glia.10243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckmaster PS, Zhang GF, Yamawaki R. Axon sprouting in a model of temporal lobe epilepsy creates a predominantly excitatory feedback circuit. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6650–6658. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06650.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrier EJ, Auchampach JA, Hillard CJ. Inhibition of an equilibrative nucleoside transporter by cannabidiol: A mechanism of cannabinoid immunosuppression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:7895–7900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511232103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cass CE, Young JD, Baldwin SA, Cabrita MA, Graham KA, Griffiths M, Jennings LL, Mackey JR, Ng AM, Ritzel MW, Vickers MF, Yao SY. Nucleoside transporters of mammalian cells. Pharm Biotechnol. 1999;12:313–352. doi: 10.1007/0-306-46812-3_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavazos JE, Cross DJ. The role of synaptic reorganization in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2006;8:483–493. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin JH, Wiesner JB, Fujitaki J. Increase in adenosine metabolites in human cerebrospinal fluid after status epilepticus. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1995;58:513–514. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.58.4.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciruela F, Casado V, Rodrigues RJ, Lujan R, Burgueno J, Canals M, Borycz J, Rebola N, Goldberg SR, Mallol J, Cortes A, Canela EI, Lopez-Gimenez JF, Milligan G, Lluis C, Cunha RA, Ferre S, Franco R. Presynaptic control of striatal glutamatergic neurotransmission by adenosine A1-A2A receptor heteromers. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2080–2087. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3574-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark RS, Carcillo JA, Kochanek PM, Obrist WD, Jackson EK, Mi Z, Wisneiwski SR, Bell MJ, Marion DW. Cerebrospinal fluid adenosine concentration and uncoupling of cerebral blood flow and oxidative metabolism after severe head injury in humans. Neurosurgery. 1997;41:1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199712000-00010. discussion 1292-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross DJ, Cavazos JE. Synaptic reorganization in subiculum and CA3 after early-life status epilepticus in the kainic acid rat model. Epilepsy Res. 2007;73:156–165. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha-Reis D, Fontinha BM, Ribeiro JA, Sebastiao AM. Tonic adenosine A1 and A2A receptor activation is required for the excitatory action of VIP on synaptic transmission in the CA1 area of the hippocampus. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52:313–320. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha RA. Regulation of the ecto-nucleotidase pathway in rat hippocampal nerve terminals. Neurochem Res. 2001;26:979–991. doi: 10.1023/a:1012392719601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha RA. Neuroprotection by adenosine in the brain: from A1 receptor activation to A2A receptor blockade. Purinergic Signaling. 2005;1:111–134. doi: 10.1007/s11302-005-0649-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha RA, Correia-de-Sa P, Sebastiao AM, Ribeiro JA. Preferential activation of excitatory adenosine receptors at rat hippocampal and neuromuscular synapses by adenosine formed from released adenine nucleotides. Br J Pharmacol. 1996a;119:253–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15979.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha RA, Vizi ES, Ribeiro JA, Sebastiao AM. Preferential release of ATP and its extracellular catabolism as a source of adenosine upon high- but not low-frequency stimulation of rat hippocampal slices. J Neurochem. 1996b;67:2180–2187. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67052180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies A, Hendrich J, Van Minh AT, Wratten J, Douglas L, Dolphin AC. Functional biology of the alpha(2)delta subunits of voltage-gated calcium channels. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2007;28:220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Sarro G, De Sarro A, Di Paola ED, Bertorelli R. Effects of adenosine receptor agonists and antagonists on audiogenic seizure-sensible DBA/2 mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;371:137–145. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00132-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decking UK, Schlieper G, Kroll K, Schrader J. Hypoxia-induced inhibition of adenosine kinase potentiates cardiac adenosine release. Circ Res. 1997;81:154–164. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.2.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLorenzo RJ, Sun DA, Blair RE, Sombati S. An in vitro model of stroke-induced epilepsy: elucidation of the roles of glutamate and calcium in the induction and maintenance of stroke-induced epileptogenesis. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2007;81:59–84. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(06)81005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLorenzo RJ, Sun DA, Deshpande LS. Cellular mechanisms underlying acquired epilepsy: The calcium hypothesis of the induction and maintainance of epilepsy. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2005;105:229–266. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diogenes MJ, Assaife-Lopes N, Pinto-Duarte A, Ribeiro JA, Sebastiao AM. Influence of age on BDNF modulation of hippocampal synaptic transmission: Interplay with adenosine A(2A) receptors. Hippocampus. 2007;17:577–585. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragunow M. Adenosine: the brain's natural anticonvulsant? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1986;7:128. [Google Scholar]

- Dragunow M, Faull RLM. Neuroprotective effects of adenosine. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1988;9:193–194. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(88)90079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudek FE, Hellier JL, Williams PA, Ferraro DJ, Staley KJ. The course of cellular alterations associated with the development of spontaneous seizures after status epilepticus. Prog Brain Res. 2002;135:53–65. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(02)35007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy S, MacVicar BA. Modulation of neuronal excitability by astrocytes. Adv Neurol. 1999;79:573–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunwiddie TV. Adenosine and suppression of seizures. Adv Neurol. 1999;79:1001–1010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunwiddie TV, Diao L, Kim HO, Jiang JL, Jacobson KA. Activation of hippocampal adenosine A3 receptors produces a desensitization of A1 receptor-mediated responses in rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1997;17:607–614. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-02-00607.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunwiddie TV, Masino SA. The role and regulation of adenosine in the central nervous system. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:31–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- During MJ, Spencer DD. Adenosine: a potential mediator of seizure arrest and postictal refractoriness. Ann Neurol. 1992;32:618–624. doi: 10.1002/ana.410320504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekonomou A, Sperk G, Kostopoulos G, Angelatou F. Reduction of A1 adenosine receptors in rat hippocampus after kainic acid-induced limbic seizures. Neurosci Lett. 2000;284:49–52. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)00954-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elger CE, Helmstaedter C, Kurthen M. Chronic epilepsy and cognition. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:663–672. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00906-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmer E, Kokaia Z, Kokaia M, Lindvall O, McIntyre DC. Mossy fibre sprouting: evidence against a facilitatory role in epileptogenesis. Neuroreport. 1997;8:1193–1196. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199703240-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel J., Jr Mesial temporal lobe epilepsy: what have we learned? Neuroscientist. 2001;7:340–352. doi: 10.1177/107385840100700410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel J., Jr So what can we conclude--do seizures damage the brain? Prog Brain Res. 2002;135:509–512. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(02)35048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etherington LA, Frenguelli BG. Endogenous adenosine modulates epileptiform activity in rat hippocampus in a receptor subtype-dependent manner. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:2539–2550. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816X.2004.03355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falenski KW, Blair RE, Sim-Selley LJ, Martin BR, DeLorenzo RJ. Status epilepticus causes a long-lasting redistribution of hippocampal cannabinoid type 1 receptor expression and function in the rat pilocarpine model of acquired epilepsy. Neuroscience. 2007;146:1232–1244. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.01.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedele DE, Gouder N, Güttinger M, Gabernet L, Scheurer L, Rulicke T, Crestani F, Boison D. Astrogliosis in epilepsy leads to overexpression of adenosine kinase resulting in seizure aggravation. Brain. 2005;128:2383–2395. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedele DE, Koch P, Brüstle O, Scheurer L, Simpson EM, Mohler H, Boison D. Engineering embryonic stem cell derived glia for adenosine delivery. Neurosci Lett. 2004;370:160–165. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedele DE, Li T, Lan JQ, Fredholm BB, Boison D. Adenosine A1 receptors are crucial in keeping an epileptic focus localized. Exp Neurol. 2006;200:184–190. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.02.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferre S, Agnati LF, Ciruela F, Lluis C, Woods AS, Fuxe K, Franco R. Neurotransmitter receptor heteromers and their integrative role in 'local modules': The striatal spine module. Brain Res Rev. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferre S, Borycz J, Goldberg SR, Hope BT, Morales M, Lluis C, Franco R, Ciruela F, Cunha R. Role of adenosine in the control of homosynaptic plasticity in striatal excitatory synapses. J Integr Neurosci. 2005;4:445–464. doi: 10.1142/s0219635205000987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field MJ, Li Z, Schwarz JB. Ca2+ channel alpha(2)-delta ligands for the treatment of neuropathic pain. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2007;50:2569–2575. doi: 10.1021/jm060650z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields RD, Burnstock G. Purinergic signalling in neuron-glia interactions. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:423–436. doi: 10.1038/nrn1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm BB, Chen JF, Cunha RA, Svenningsson P, Vaugeois JM. Adenosine and brain function. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2005a;63:191–270. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(05)63007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm BB, Chen JF, Masino SA, Vaugeois JM. Actions of adenosine at its receptors in the CNS: Insights from knockouts and drugs. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005b;45:385–412. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.095731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm BB, Ijzerman AP, Jacobson KA, Klotz KN, Linden J. International Union of Pharmacology. XXV. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53:527–552. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenguelli BG, Wigmore G, Llaudet E, Dale N. Temporal and mechanistic dissociation of ATP and adenosine release during ischaemia in the mammalian hippocampus. J Neurochem. 2007;101:1400–1413. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04425.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuxe K, Ferre S, Genedani S, Franco R, Agnati LF. Adenosine receptor-dopamine receptor interactions in the basal ganglia and their relevance for brain function. Physiol Behav. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass M, Faull RL, Bullock JY, Jansen K, Mee EW, Walker EB, Synek BJ, Dragunow M. Loss of A1 adenosine receptors in human temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain Res. 1996;710:56–68. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01313-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorter JA, van Vliet EA, Lopes da Silva FH, Isom LL, Aronica E. Sodium channel beta1-subunit expression is increased in reactive astrocytes in a rat model for mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:360–364. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouder N, Fritschy JM, Boison D. Seizure suppression by adenosine A1 receptor activation in a mouse model of pharmacoresistant epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2003;44:877–885. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2003.03603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouder N, Scheurer L, Fritschy J-M, Boison D. Overexpression of adenosine kinase in epileptic hippocampus contributes to epileptogenesis. J Neurosci. 2004;24:692–701. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4781-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JH, Owen RP, Giacomini KM. The concentrative nucleoside transporter family, SLC28. Pflugers Arch. 2004;447:728–734. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1107-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Güttinger M, Fedele DE, Koch P, Padrun V, Pralong W, Brüstle O, Boison D. Suppression of kindled seizures by paracrine adenosine release from stem cell derived brain implants. Epilepsia. 2005a;46:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.61804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Güttinger M, Padrun V, Pralong W, Boison D. Seizure suppression and lack of adenosine A1 receptor desensitization after focal long-term delivery of adenosine by encapsulated myoblasts. Exp Neurol. 2005b;193:53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberg A, Qu H, Haraldseth O, Unsgard G, Sonnewald U. In vivo effects of adenosine A1 receptor agonist and antagonist on neuronal and astrocytic intermediary metabolism studied with ex vivo 13C NMR spectroscopy. J Neurochem. 2000;74:327–333. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0740327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halassa MM, Fellin T, Haydon PG. The tripartite synapse: roles for gliotransmission in health and disease. Trends Mol Med. 2007a;13:54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halassa MM, Fellin T, Takano H, Dong JH, Haydon PG. Synaptic islands defined by the territory of a single astrocyte. J Neurosci. 2007b;27:6473–6477. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1419-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser RA, Hubble JP, Truong DD. Randomized trial of the adenosine A(2A) receptor antagonist istradefylline in advanced PD. Neurology. 2003;61:297–303. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000081227.84197.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser WA, Annegers JF. Risk factors for epilepsy. Epilepsy Res Suppl. 1991;4:45–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser WA, Annegers JF, Kurland LT. Prevalence of epilepsy in Rochester, Minnesota: 1940–1980. Epilepsia. 1991;32:429–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1991.tb04675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haydon PG, Carmignoto G. Astrocyte control of synaptic transmission and neurovascular coupling. Physiological Reviews. 2006;86:1009–1031. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00049.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindley S, Herman MA, Rathbone MP. Stimulation of reactive astrogliosis in vivo by extracellular adenosine diphosphate or an adenosine A2 receptor agonist. J Neurosci Res. 1994;38:399–406. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490380405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes GL, Ben-Ari Y. Seizing hold of seizures. Nat Med. 2003;9:994–996. doi: 10.1038/nm0803-994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber A, Güttinger M, Möhler H, Boison D. Seizure suppression by adenosine A2A receptor activation in a rat model of audiogenic brainstem epilepsy. Neurosci Lett. 2002;329:289–292. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00684-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber A, Padrun V, Deglon N, Aebischer P, Mohler H, Boison D. Grafts of adenosine-releasing cells suppress seizures in kindling epilepsy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:7611–7616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.131102898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasato T, Nomura R, Ando R, Ikeda T, Tanaka M, Itohara S. Dorsal telencephalon-specific expression of Cre recombinase in PAC transgenic mice. Genesis. 2004;38:130–138. doi: 10.1002/gene.20009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson KA, Gao ZG. Adenosine receptors as therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:247–264. doi: 10.1038/nrd1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson KA, von Lubitz DKJE, Daly JW, Fredholm BB. Adenosine receptor ligands: differences with acute versus chronic treatment. TiPS. 1996;17:108–113. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(96)10002-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jallon P. The problem of intractability - the continuing need for new medical therapies in epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1997;38:S 37–S 42. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1997.tb05203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javitt DC, Coyle JT. Decoding schizophrenia. Sci Am. 2004;290:48–55. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0104-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharatishvili I, Nissinen JP, McIntosh TK, Pitkanen A. A model of posttraumatic epilepsy induced by lateral fluid-percussion brain injury in rats. Neuroscience. 2006;140:685–697. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khurgel M, Ivy GO. Astrocytes in kindling: relevance to epileptogenesis. Epilepsy Res. 1996;26:163–175. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(96)00051-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanek PM, Vagni VA, Janesko KL, Washington CB, Crumrine PK, Garman RH, Jenkins LW, Clark RS, Homanics GE, Dixon CE, Schnermann J, Jackson EK. Adenosine A1 receptor knockout mice develop lethal status epilepticus after experimental traumatic brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:565–575. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohling R. Pathophysiology of epilepsy. Klinische Neurophysiologie. 2006;37:216–224. [Google Scholar]

- Kokaia M, Holmberg K, Nanobashvili A, Xu ZQ, Kokaia Z, Lendahl U, Hilke S, Theodorsson E, Kahl U, Bartfai T, Lindvall O, Hokfelt T. Suppressed kindling epileptogenesis in mice with ectopic overexpression of galanin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:14006–14011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231496298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong W, Engel K, Wang J. Mammalian nucleoside transporters. Curr Drug Metab. 2004;5:63–84. doi: 10.2174/1389200043489162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunz WS. The role of mitochondria in epileptogenesis. Curr Opin Neurol. 2002;15:179–184. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200204000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Ren G, Lusardi T, Wilz A, Lan JQ, Iwasato T, Itohara S, Simon RP, Boison D. Adenosine kinase, a target for the prediction and prevention of epileptogenesis. J Clin Inv. 2007a doi: 10.1172/JCI33737. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Steinbeck JA, Lusardi T, Koch P, Lan JQ, Wilz A, Segschneider M, Simon RP, Brustle O, Boison D. Suppression of kindling epileptogenesis by adenosine releasing stem cellderived brain implants. Brain. 2007b;130:1276–1288. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longo BM, Mello LE. Supragranular mossy fiber sprouting is not necessary for spontaneous seizures in the intrahippocampal kainate model of epilepsy in the rat. Epilepsy Res. 1998;32:172–182. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(98)00049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longo BM, Mello LE. Effect of long-term spontaneous recurrent seizures or reinduction of status epilepticus on the development of supragranular mossy fiber sprouting. Epilepsy Res. 1999;36:233–241. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(99)00054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]