Abstract

Laser capture microdissection (LCM) is used extensively for genome and transcriptome profiling. Traditionally, however, DNA and RNA are purified from separate populations of LCM-harvested cells, limiting the strength of inferences about the relationship between gene expression and gene sequence variation. There have been no published protocols for the simultaneous isolation of DNA and RNA from the same cells that are obtained by LCM of patient tissue specimens. Here we report an adaptation of the Qiagen AllPrep method that allows the purification of DNA and RNA from the same LCM-harvested cells. We compared DNA and RNA purified by the QIAamp DNA Micro kit and the PicoPure RNA Isolation kit, respectively, from LCM-collected cells from adjacent tissue sections of the same specimen. The adapted method yields 90% of DNA and 38% of RNA compared with the individual methods. When tested with the GeneChip 250K Nsp Array, the concordance rate of the single nucleotide polymorphism heterozygosity calls was 98%. When tested with the GeneChip U133 Plus 2.0 Array, the correlation coefficient of the raw gene expression was 97%. Thus, we developed a method to obtain both DNA and RNA material from a single population of LCM-harvested cells and herein discuss the strengths and limitations of this methodology.

Cancer is a complex and heterogeneous disease. Comprehensive characterization of the cancer genome, transcriptome, and proteome expands our knowledge of the carcinogenic process and strengthens our power to find new biomarkers and drug targets. Tissue specimens typically resected from cancer patients are composed of complex cell types including normal and malignant epithelial cells, fibroblasts, immune cells, and endothelial cells. Given the potential contributions of each cell type to tumor progression, it is necessary to characterize cell-specific changes at the DNA, RNA, and protein level. Laser capture microdissection (LCM) allows one to capture a population of homogeneous target cells from a heterogeneous tissue section.1 The method thus significantly improves the accuracy of the cell-specific molecular profiling, as it eliminates noise derived from bystander cell contamination. Currently, LCM-harvested tissues are widely used for cancer genotyping,2,3 loss of heterozygosity/copy number variation (LOH/CNV) analysis,4,5 and gene expression profiling.6,7

Despite the fact that LCM reduces the heterogeneity of tumor tissues, it remains a tedious process. Both optimal cutting temperature compound (OCT)-embedded fresh-frozen tissues and formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues are used for LCM. However, DNA and RNA extracted from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues are highly fragmented because of the formalin-induced cross-linking. Thus, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues are not ideal starting materials for genome-wide molecular profiling.8,9 Ideally, fresh tissue specimens for LCM should be embedded in OCT on surgical removal. However, this requires carrying cumbersome laboratory supplies close to the location of surgery and processing the specimen almost immediately. Snap-freezing and preserving the tissue specimen in liquid nitrogen is an alternative for cryoprotection of clinical samples. For this reason, we optimized our methods to allow for this simple specimen collection protocol.

Currently, different methods have been developed for extracting DNA and RNA from LCM-harvested cells. However, we were unable to find a published method that allows isolation of DNA and RNA so that the same LCM-harvested cells can be assayed for genome and transcriptome profiling, respectively. Instead, DNA and RNA are usually isolated from the same cell type but from adjacent tissue sections, thus potentially introducing errors if one is interested in assessing how genomic changes (CNV/LOH) correlate with gene expression changes. A method allowing simultaneous DNA and RNA extraction from the same population of cells would overcome such a limitation, as well as address two additional issues: 1) it is often the situation that a limited amount of tissue is available for research purposes; and 2) LCM time is costly. Methods for simultaneous extraction of DNA and RNA have been developed using TRIzol10 or guanidinium-based reagent.11,12 But to our knowledge, these methods have not been tested at the microscopic scale, eg, LCM-harvested cells. Here we describe our experience in extracting both DNA and RNA from laser capture microdissected tissue and present an option for extracting both DNA and RNA from the same cells for genome and transcriptome profiling. In addition, we characterized tissue specimen integrity and cell quantities needed for molecular profiling using this method, and we compared those results with results obtained when DNA and RNA were obtained from separate cell populations following conventional methods.

Materials and Methods

Tissue Preparation and LCM

Oral cancer specimens obtained with consent from three patients undergoing surgical treatment were snap-frozen and stored in liquid nitrogen until use. The use of clinical materials was approved by the institutional review office at the University of Washington and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. The specimens were embedded using Tissue-Tek OCT compound (Sakura Fineteck USA, Torrance, CA). To optimize the quality of RNA, we tested solidifying the OCT blocks under three conditions: in a cryostat chamber at –20°C, in 2-methylbutane on dry ice, and in liquid nitrogen. Solidification in 2-methylbutane on dry ice was chosen for OCT embedment and OCT blocks were stored at −80°C. Tissue sectioning and staining were performed as previously described.6 Stained tissue slides were stored in xylene at 4°C for up to 2 hours until ready for LCM. LCM was performed using the Veritas laser capture microdissection system (Molecular Devices, Union City, CA). Depending on the specimen size and tumor contents, two to six 8-μm sections were used in each capture of about 50,000 cancer cells (about 4 mm2), an amount expected to generate sufficient DNA (250 ng) for the genome profiling. The time from taking the tissue sections out of xylene to finishing LCM and starting DNA/RNA extraction was limited to less than 45 minutes to protect sample integrity. RNA was also extracted from tissues scraped from adjacent tissue sections for sample integrity assessment.

Purification of DNA and RNA

Isolation of DNA and RNA from LCM-harvested cancer cells was performed using the AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini kit and the RNeasy Micro kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the AllPrep DNA/RNA protocol with certain modifications. Briefly, the cancer cells were incubated in 50 μl of RLT Plus buffer with rotation (200 rpm) on a Lab Line orbit shaker 3520 (Barnstead International, Dubuque, IA) at room temperature for 4 hours. Extracts from the same specimen were combined and loaded onto an AllPrep DNA spin column for DNA to bind to the column. The column was centrifuged at 8000 × g for 1 minute to collect the flow-through RNA-containing fraction. The column was then washed by adding 100 μl of RLT Plus buffer and centrifugation at 8000 × g for 1 minute. Both flow-through RNA-containing fractions were combined and mixed with an equal volume of 70% ethanol. The mixture was then transferred to an RNeasy MinElute spin column from the RNeasy Micro kit for RNA to bind to the column. RNA purification included an on-column DNase I treatment according to the RNeasy Micro kit protocol. The DNA bound to the AllPrep DNA spin column was then purified according to the AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini kit protocol except that the DNA was eluted with 2 × 50 μl of H2O so that the DNA could be concentrated and used for genome profiling. To increase the elution efficiency, the H2O was adjusted to pH 8 with 8 mmol/L NaOH before elution. Quantity and quality of purified RNA and DNA was determined by ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE) and Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). RNA was stored in −80°C. DNA was dried on a Savant DNA Speed Vac 110 (Global Medical Instrumentation, Ramsey, MN) and re-dissolved as 50 ng/μl in 10 mmol/L Tris-HCl pH 8, 0.1 mmol/L EDTA and stored at −20°C. For comparison, DNA and RNA were purified separately from LCM-harvested cancer cells from adjacent sections of the same tissue specimen using QIAamp DNA Micro kit (Qiagen) and PicoPure RNA Isolation kit (Molecular Devices), respectively, following the manufacturer's protocols. Purification of both DNA and RNA from a single population of LCM-harvested cancer cells was also performed using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, the LCM-harvested cells were incubated with 50 μl of TRIzol reagent at room temperature for 15 minutes to extract DNA and RNA. After phenol-chloroform separation, RNA in the upper aqueous phase was precipitated. The RNA was cleaned and treated with DNase I using the RNeasy Micro kit according to the manufacturer's protocol. DNA was then extracted from the interphase by an extraction buffer per the manufacturer's protocol. The extracted DNA was precipitated and then cleaned with the QIAamp DNA Micro kit according to the manufacturer's protocol. Genomic DNA was extracted from buffy coat cells isolated from the patients' peripheral blood and used as reference in genome profiling. We followed the salting out method of Miller et al13 but with the proteinase K incubation step performed at 65°C rather than the reported 37°C.

Genome Profiling with the Purified DNA

Both DNA (250 ng) purified by the adapted AllPrep method and the QIAamp DNA purification method were tested in parallel using GeneChip Human Mapping 250K Nsp Array (Affymetrix Inc., Santa Clara, CA) following the manufacturer's protocol. Hybridized raw feature intensity was acquired with Affymetrix GCOS version 1.4 software and processed with Affymetrix GTYPE version 4.1 software. The single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotype calls were generated with the Dynamic Modeling mapping algorithm. Copy number and LOH were predicted with Affymetrix CNAT version 4.0.1 software using the Affymetrix 48 HapMap normal reference samples for generating the global reference.

Transcriptome Profiling with the Purified RNA

Both RNA purified by the adapted AllPrep method and the PicoPure RNA purification method were tested in parallel on GeneChip Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array (Affymetrix Inc.). Linear RNA amplification, target preparation, and gene expression profiling were performed as previously described6 except that GeneChip IVT labeling kit (Affymetrix Inc.) was used, instead of the Enzo BioArray high yield RNA transcript labeling system. Hybridized raw feature intensity was acquired and analyzed with GCOS. For genes present on both profiles generated with RNA purified by the adapted AllPrep method and the PicoPure method, the Pearson correlation coefficient of the measured gene expression value was calculated using Microsoft Excel 2007.

Results

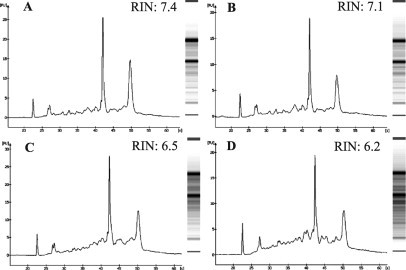

Given that RNA is much less stable than DNA, we assessed the tissue quality by monitoring the RNA integrity after each major process using an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer. In early studies, solidification of the OCT blocks was performed under different temperature settings including at –20°C, on dry ice, and in liquid nitrogen. In this study, we found OCT blocks solidified at –20°C in the cryostat chamber were the easiest to section, but more severe RNA degradation was occasionally observed. On the other hand, OCT blocks solidified in liquid nitrogen best protected RNA integrity but the blocks were brittle and difficult to section. OCT blocks solidified in 2-methylbutane on dry ice produced reasonable quality OCT blocks for sectioning with minimal RNA degradation (Figure 1A). The tissue section stored in a slide box at −80°C for 48 hours awaiting the pathological review of an adjacent section stained with hematoxylin and eosin did not show significant change in RNA integrity (Figure 1B). RNA degradation was mainly observed during the HistoGene staining process (Figure 1C). All RNA purified from LCM-harvested cells had an integrity number14 equal to 5.9 or higher (Figure 1D) and were suitable for amplification and gene expression profiling.

Figure 1.

A representative tissue specimen quality assessment result. After OCT embedment, the tissue was collected by scraping from slides after sectioning (A), after storage at −80°C for 48 hours (B), after HistoGene staining (C), and after LCM (D); tissue sectioning and staining were performed as previously described.6 RNA was extracted from the scraped tissues, and the integrity of the purified RNA was assessed by an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer. The x axis indicates the relative migration or size of the nucleic acid and the y axis displays the fluorescence or quantity. At right is the virtual gel of the sample generated by the bioanalyzer. RIN, RNA integrity number.

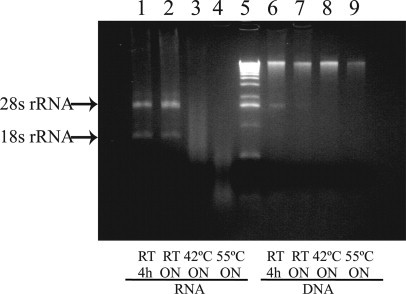

In general, DNA and RNA are extracted from the LCM-harvested cells by incubating the cap adhering cells in the DNA or RNA extraction buffer. When we incubated the LCM-captured cells with the guanidinium-based extraction buffer RLT Plus for 30 minutes and purified the DNA and RNA following the AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini kit protocol, less than 40% of DNA was extracted as compared to the QIAamp DNA purification method (data not shown). We therefore tested extending the extraction times and increasing the extraction temperature to improve the extraction efficiency. RNA integrity was not affected by either 4-hour or overnight incubations of the LCM-harvested cells with the extraction buffer RLT Plus at room temperature (Figure 2, panels 1 and 2). But raising the extraction temperature to 42°C or 55°C caused severe RNA degradation (Figure 2, panels 3 and 4). DNA integrity was less affected in these extraction conditions (Figure 2, lanes 6–9). On the agarose gel of some purified DNA samples, a band of the size of the 28S ribosomal RNA was observed (eg, Figure 2, panel 6), which indicated potential RNA contamination. This band was also shown on the agarose gel of the purified DNA samples on the manufacturer's website for the AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini kit. To avoid RNA contamination, we added an additional wash step with extraction buffer RLT Plus in our final adapted AllPrep DNA/RNA protocol.

Figure 2.

Comparison of different extraction conditions. LCM-harvested cells were incubated with AllPrep RLT Plus extraction buffer at room temperature for 4 hours (lane 1: RNA; lane 6: DNA); at room temperature overnight (lane 2: RNA; lane 7: DNA); at 42°C overnight (lane 3: RNA; lane 8: DNA); and at 55°C overnight (lane 4: RNA; lane 9: DNA). Purified DNA and RNA were revealed on a 1% agarose gel. Lane 5 shows the 1-kb DNA size ladder.

On average, 250 to 270 ng of DNA and 130 to 160 ng of RNA were purified from the 50,000 LCM-harvested cancer cells by the adapted AllPrep DNA/RNA method. Compared with the QIAamp DNA purification method and the PicoPure RNA purification method, the adapted AllPrep DNA/RNA method yielded 90.3 ± 22.3% DNA and 38.3 ± 17.7% RNA.

All amplified DNA fragments were in the expected size range of 200 to 1100 bp. No significant differences were observed on the amplified DNA fragments between the DNA purified by the adapted AllPrep DNA/RNA method and by the QIAamp DNA purification method (Figure 3A). Copy number variations as detected by the SNP array using DNA purified by both methods were highly consistent (Figure 3C). For example, one CNV gain on chromosome 11 of patients 2 and 3 and four CNV gain on chromosome 20 of patient 2 were detected by both profiles with DNA from the adapted AllPrep DNA/RNA method and from the QIAamp method (Figure 3D). All arrays tested passed the Affymetrix 93% minimum SNP call rate criterion. The average SNP call rate was 95.6% for DNA isolated by the adapted AllPrep method, and 95.2% for DNA isolated by the QIAamp method. On average, 98% of the heterozygosity SNPs called on the profiles generated using DNA from the adapted AllPrep method were also called on the profiles using QIAamp DNA (Table 1).

Figure 3.

Using the DNA purified by the adapted AllPrep DNA/RNA method for genome profiling. A: Amplified tumor DNA fragments from DNA purified by the adapted AllPrep DNA/RNA method and by the QIAamp DNA purification method as revealed on a 2% agarose gel. Each DNA sample was amplified in three independent polymerase chain reaction amplifications as shown in three lanes. DirectLoad wide range DNA marker was used on both sides as size ladder. B: Amplified tumor DNA fragments from DNA purified by the TRIzol method and by the QIAamp DNA purification method as revealed on a 2% agarose gel. Size marker is the same as in A. C: Whole genome CNV measured on the Affymetrix GeneChip Human Mapping 250K Nsp Array using DNA purified by the adapted AllPrep DNA/RNA method (AllPrep) and by the QIAamp DNA purification method (QIAamp). CNV of buffy coat DNA from each patient (1–3) was also presented as reference. x axis, SNP locations; y axis, log_2 signal intensity ratios; the gray horizontal line is for y = 0. D: Details of CNV on chromosome 11 (left) and chromosome 20 (right).

Table 1.

Comparison of SNP Calls Generated Using DNA from the Adapted AllPrep Method to DNA from the QIAamp Method

| Heterozygosity calls |

Homozygosity calls |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specimen no. | Total calls | Match* | Mismatch† | Missing‡ | Concordance§ | Total calls | Match* | Mismatch† | Missing‡ | Concordance§ |

| 1 | 49,366 | 44,473 | 1067 | 3826 | 97.7% | 198,199 | 188,322 | 2398 | 7479 | 98.7% |

| 2 | 65,836 | 56,344 | 1615 | 7877 | 97.2% | 188,024 | 182,217 | 761 | 5046 | 99.6% |

| 3 | 62,875 | 60,641 | 435 | 1799 | 99.3% | 187,518 | 183,811 | 1154 | 2553 | 99.4% |

Match: the SNP call is identical.

Mismatch: the SNP call is different.

Missing: the SNP call is not made in the profile of QIAamp method.

Concordance: match SNP calls/(match + mismatch SNP calls).

We have also tested using DNA and RNA purified by the TRIzol method for genome and transcriptome profiling. However, amplified DNA fragments using DNA purified by the TRIzol method were significantly larger than fragments of DNA purified by the QIAamp DNA purification method (Figure 3B). In two of the three purified DNA samples tested, the polymerase chain reaction-amplified DNA fragments comprised less than 90 μg and thus were not sufficient for the 250K Nsp array profiling. The amplified DNA fragments of the third sample just met the 90 μg criterion and thus were used for genome profiling. However, the SNP call rate of the 250K Nsp array profile was only 87%, which was a failure according to the Affymetrix standard. In addition, the array profiles using DNA purified by the TRIzol method and by the QIAamp DNA purification method of the same specimen were highly inconsistent (data not shown).

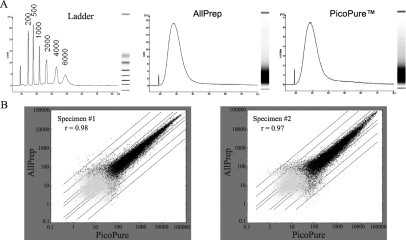

To see if the purified RNA was suitable for transcriptome profiling, we isolated RNA by the adapted AllPrep DNA/RNA method and by the PicoPure RNA purification method from LCM-harvested cells on adjacent tissue sections of the same specimens. In the process, RNA from both the adapted AllPrep DNA/RNA method and the PicoPure method were put through two rounds of linear amplification. No significant differences were detected between the generated cRNA spectra as revealed by the Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer (Figure 4A). We observed close similarity between the expression profiles generated using RNA purified by both methods; the Pearson correlation coefficient was 0.975 ± 0.01 (average ± SD of the two patient specimens) (Figure 4B). The background levels of all four arrays met the Affymetrix standard. The 3′/5′ ratios of the glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase and β-actin genes and the percentages of present calls of the gene expression profiles generated by the two methods were similar (Table 2).

Figure 4.

Using the RNA purified by the adapted AllPrep DNA/RNA method for expression profiling. A: Representative spectra of cRNA after two-round linear amplification, as revealed by the Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer from RNA purified by the adapted AllPrep DNA/RNA method (middle) and by the PicoPure method (right). Left panel shows the RNA size ladder. B: Scatter plots showing the correlation of gene expression measured on Affymetrix GeneChip HG-U133 Plus 2.0 Array using RNA purified by the adapted AllPrep DNA/RNA method (y axis) and by the PicoPure method (x axis). The Pearson correlation coefficient (r) for each test pair is as presented.

Table 2.

Comparison of U133 Plus 2.0 Array Profiles Generated Using RNA Purified by the Adapted AllPrep Method and by the PicoPure Method

| Adapted AllPrep | PicoPure | |

|---|---|---|

| Average background | 55.4 ± 1.4 | 60.0 ± 1.3 |

| Probe present (%) | 42.3 ± 2.0 | 44.3 ± 1.1 |

| 3′/5′ ratio of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 7.7 ± 1.3 | 9.0 ± 1.1 |

| 3′/5′ ratio of β-actin | 47.9 ± 15.1 | 59.5 ± 38.2 |

*Measurements are average ± SD of two tissue specimens.

Discussion

We have developed a method that allows efficient purification of both DNA and RNA from a single population of LCM-harvested cells. The purified DNA and RNA samples were found to be useful for genome and transcriptome profiling as judged by interrogation with the Affymetrix GeneChip Human Mapping 250K Nsp Array and the Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array. We demonstrated that DNA and RNA obtained by this method yielded comparable results compared to DNA and RNA prepared separately using conventional protocols. The method not only presents a more efficient and cost-effective way to use precious LCM-harvested patient tissue samples, but it also provides an approach for providing for stronger inferences about the relationship between genomic alterations and gene expression for cancer research. To our knowledge, this is the first report providing information to meet the technical challenge of obtaining DNA and RNA from the same cells obtained by LCM, yielding samples that are suitable for downstream array analyses.

Joint profiling of the genome and transcriptome of the same tumor can also be achieved by obtaining DNA and RNA from LCM-harvested cells of adjacent tissue sections. However, cancer tissues are highly heterogeneous and there may be some inherent differences between adjacent sections that could introduce errors when comparing genome changes, such as CNV/LOH events, with gene expression.15,16 A recent study of chromosome regions 9p21 and 17p13 in oral squamous cell carcinoma detected more LOH events in the invasive tumor front than in the center of the tumor.4 In addition, two dissections may not match in cellular composition to each other perfectly, especially when large dissections are performed over a wide range of the tissue field. The efficiency of harvesting target cells by LCM is also affected by many factors, including the quality of the tissue section, the slide, the LCM cap, the staining, and the setting and position of the laser beam. Thus, even if the quantity of tissue specimen is enough to support separate extraction of DNA and RNA, LCM of the same region of tissue but on two adjacent tissue sections may introduce processing bias. The method described here obtained DNA and RNA from the same population of cells. Thus, the relationship between genome and transcriptome profiles could be better approximated than if separate samples were interrogated. In addition, the method saves LCM time and cost when compared with using traditional methods to obtain DNA and RNA from separate tissue sections by LCM.

Snap-freezing and preserving the tissue specimens in liquid nitrogen is a practical and convenient method for clinical sample collection and storage. This method of specimen preservation allows tissue embedding under more controlled settings, without having to disrupt the operating room workflow and personnel. In this study, we embedded the fresh frozen tissues in OCT on dry ice, which ensures both quality of the OCT block and quality of the RNA/DNA contents. Although some degree of RNA degradation is observed, especially during the staining process, the quality of the purified DNA and RNA allows for genome and transcriptome profiling. Additional steps for protecting the DNA/RNA integrity, such as shortening the processing time, prefixation, or adding protection reagents did not seem necessary.17,18,19

Quality and quantity of DNA and RNA are key elements for successful genome and transcriptome profiling. In this regard, we have also tested DNA and RNA isolated from LCM-harvested cells using TRIzol reagent. Although the purified RNA is good for gene expression profiling, the purified DNA appears to be resistant to NspI digestion. This is consistent with observations reported by the inventor of the TRIzol method that the digestion efficiency by restriction enzymes is reduced in DNA extracted by this method.10 Thus, although the TRIzol reagent can be used for simultaneous extraction of DNA and RNA from the same cell population, we found that the quality of the DNA is not good enough for genome profiling. On the other hand, methods using guanidinium-based reagent produce good quality DNA and RNA.20 One limitation of our adapted AllPrep method is that, although it recovers most of the DNA compared to the control method, it only recovers 38% of the RNA compared to the PicoPure method. However, the yield of the RNA (130–160 ng) was more than sufficient for gene expression profiling as only 5 to 30 ng total RNA was needed. Because of the reduced DNA and RNA yields, it will require capturing more cells if the same quantities of DNA and RNA are desired. Therefore, this method will be more efficient and cost-effective if both DNA and RNA from the same cells will be used in downstream applications. In summary, we have demonstrated that, with certain modifications, the guanidinium-based Qiagen AllPrep method can be used for simultaneous extraction of DNA and RNA from LCM-captured cells for genome and transcriptome profiling.

Footnotes

Supported by the National Institutes of Health Roadmap for Medical Research, 5 K12 RR023265-04; The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation through the Amos Medical Faculty Development Program Award; and grant R01 CA 095419 from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD.

References

- 1.Simone NL, Bonner RF, Gillespie JW, Emmert-Buck MR, Liotta LA. Laser-capture microdissection: opening the microscopic frontier to molecular analysis. Trends Genet. 1998;14:272–276. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(98)01489-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rook MS, Delach SM, Deyneko G, Worlock A, Wolfe JL. Whole genome amplification of DNA from laser capture-microdissected tissue for high-throughput single nucleotide polymorphism and short tandem repeat genotyping. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:23–33. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63092-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dillon D, Zheng K, Costa J. Rapid, efficient genotyping of clinical tumor samples by laser-capture microdissection/PCR/SSCP. Exp Mol Pathol. 2001;70:195–200. doi: 10.1006/exmp.2001.2362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang X, Fan M, Chen X, Wang S, Alsharif MJ, Wang L, Liu L, Deng H. Intratumor genomic heterogeneity correlates with histological grade of advanced oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2006;42:740–744. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2005.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takeshima Y, Amatya VJ, Daimaru Y, Nakayori F, Nakano T, Inai K. Heterogeneous genetic alterations in ovarian mucinous tumors: application and usefulness of laser capture microdissection. Hum Pathol. 2001;32:1203–1208. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2001.28956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mendez E, Fan W, Choi P, Agoff SN, Whipple M, Farwell DG, Futran ND, Weymuller EA, Zhao LP, Chen C. Tumor-specific genetic expression profiles of metastatic oral squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2007;29:803–814. doi: 10.1002/hed.20598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu MS, Lin YS, Chang YT, Shun CT, Lin MT, Lin JT. Gene expression profiling of gastric cancer by microarray combined with laser capture microdissection. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:7405–7412. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i47.7405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coudry RA, Meireles SI, Stoyanova R, Cooper HS, Carpino A, Wang X, Engstrom PF, Clapper ML. Successful application of microarray technology to microdissected formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue. J Mol Diagn. 2007;9:70–79. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2007.060004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hood BL, Darfler MM, Guiel TG, Furusato B, Lucas DA, Ringeisen BR, Sesterhenn IA, Conrads TP, Veenstra TD, Krizman DB. Proteomic analysis of formalin-fixed prostate cancer tissue. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:1741–1753. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500102-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chomczynski P. A reagent for the single-step simultaneous isolation of RNA, DNA and proteins from cell and tissue samples. Biotechniques. 1993;15:532–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jenner MW, Leone PE, Walker BA, Ross FM, Johnson DC, Gonzalez D, Chiecchio L, Dachs Cabanas E, Dagrada GP, Nightingale M, Protheroe RK, Stockley D, Else M, Dickens NJ, Cross NC, Davies FE, Morgan GJ. Gene mapping and expression analysis of 16q loss of heterozygosity identifies WWOX and CYLD as being important in determining clinical outcome in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2007;110:3291–3300. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-075069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walker BA, Leone PE, Jenner MW, Li C, Gonzalez D, Johnson DC, Ross FM, Davies FE, Morgan GJ. Integration of global SNP-based mapping and expression arrays reveals key regions, mechanisms, and genes important in the pathogenesis of multiple myeloma. Blood. 2006;108:1733–1743. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-005496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller SA, Dykes DD, Polesky HF. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:1215. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.3.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schroeder A, Mueller O, Stocker S, Salowsky R, Leiber M, Gassmann M, Lightfoot S, Menzel W, Granzow M, Ragg T. The RIN: an RNA integrity number for assigning integrity values to RNA measurements. BMC Mol Biol. 2006;7:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-7-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Torres L, Ribeiro FR, Pandis N, Andersen JA, Heim S, Teixeira MR. Intratumor genomic heterogeneity in breast cancer with clonal divergence between primary carcinomas and lymph node metastases. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;102:143–155. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9317-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andersen CL, Wiuf C, Kruhoffer M, Korsgaard M, Laurberg S, Orntoft TF. Frequent occurrence of uniparental disomy in colorectal cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:38–48. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kube DM, Savci-Heijink CD, Lamblin AF, Kosari F, Vasmatzis G, Cheville JC, Connelly DP, Klee GG. Optimization of laser capture microdissection and RNA amplification for gene expression profiling of prostate cancer. BMC Mol Biol. 2007;8:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-8-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kihara AH, Moriscot AS, Ferreira PJ, Hamassaki DE. Protecting RNA in fixed tissue: an alternative method for LCM users. J Neurosci Methods. 2005;148:103–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2005.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiang CC, Mezey E, Chen M, Key S, Ma L, Brownstein MJ. Using DSP, a reversible cross-linker, to fix tissue sections for immunostaining, microdissection and expression profiling. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:e185. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coombs LM, Pigott D, Proctor A, Eydmann M, Denner J, Knowles MA. Simultaneous isolation of DNA. RNA, and antigenic protein exhibiting kinase activity from small tumor samples using guanidine isothiocyanate. Anal Biochem. 1990;188:338–343. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(90)90617-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]