Abstract

Histone variants play an important role in numerous biological processes through changes in nucleosome structure and stability and possibly through mechanisms influenced by posttranslational modifications unique to a histone variant. The family of histone H2A variants includes members such as H2A.Z, the DNA damage-associated H2A.X, macroH2A (mH2A), and H2ABbd (Barr body-deficient). Here, we have undertaken the challenge to decipher the posttranslational modification-mediated “histone code” of mH2A, a variant generally associated with certain forms of condensed chromatin such as the inactive X chromosome in female mammals. By using female human cells as a source of mH2A, endogenous mH2A was purified and analyzed by mass spectrometry. Although mH2A is in low abundance compared with conventional histones, we identified a phosphorylation site, S137ph, which resides within the “hinge” region of mH2A. This lysine-rich hinge is an ≈30-aa stretch between the H2A and macro domains, proposed to bind nucleic acids. A specific antibody to S137ph was raised; by using this reagent, S137 phosphorylation was found to be present in both male and female cells and on both splice variants of the mH2A1 gene. Although mH2A is generally enriched on the inactive X chromosome in female cells, mH2AS137ph is excluded from this heterochromatic structure. Thus, a phosphorylated subpopulation of mH2A appears to play a unique role in chromatin regulation beyond X inactivation. We provide evidence that S137ph is enriched in mitosis, suggestive of a role in the regulation of mH2A posttranslational modifications throughout the cell cycle.

Keywords: macroH2A, histone modifications, phosphorylation

Histone variant proteins replace their conventional histone counterparts within the chromatin template at specific genomic locations or during particular nuclear processes (1–4). When incorporated into chromatin, histone variants participate in diverse nuclear functions, including centromeric regulation, sensing DNA damage, and transcriptional activation and repression, and they potentially play a role in epigenetic inheritance of chromatin states (1–4). Histone variants also play an important role in changing the structure and stability of the nucleosome (cis mechanisms) and provide the cell with the potential to change its posttranslational modification (PTM) profile caused by amino acid sequence variations (4). In turn, differences in PTM-based signatures of variants may lead to the differential engagement of downstream binding effectors (trans mechanisms), significantly affecting the biological readout of particular genomic regions (4).

Histone variants have been identified primarily from the H2A and H3 families, although H2B variants also exist in mammals (3, 4). Variants often differ from conventional histones by subtle amino acid changes. However, one histone variant in particular, macroH2A (hereafter mH2A), contains a large non-histone domain (the macro domain) on its C terminus, resulting in a histone approximately three times the size of conventional H2A (5). Importantly, and unlike most other well studied variants, mH2A is vertebrate-specific, consistent with the general view that evolutionary expansion may correlate with increased needs for functional specialization (6). Three isoforms exist in mammals: mH2A1.1, mH2A1.2, and mH2A2. The former two are alternatively spliced from the mH2A1 gene and differ only by one exon in the macro domain, whereas a second gene encodes mH2A2 (6, 7). All isoforms contain an N-terminal H2A-like region (65% homologous to H2A), a C-terminal macro domain, and a short lysine-rich hinge region that connects the two (5). The functional differences between mH2A1.1 and 1.2 are unclear; however, only the macro domain of mH2A1.1 can bind ADP-ribose (8). The in vivo consequences of this activity have yet to be determined.

mH2A has been shown to associate with different forms of condensed chromatin. In female mammals, for example, mH2A is preferentially concentrated on the inactive X chromosome (Xi), suggestive of a role in transcriptionally repressed chromatin (9). During early mammalian development, one of two X chromosomes is silenced in females to achieve dosage compensation for X-linked gene products, and once inactivated, the heterochromatic nature of the Xi is stably maintained (10). Senescence-associated heterochromatin foci, specialized domains of transcriptional repression, also contain mH2A (11). Furthermore, mH2A has been associated with loci that are CpG-methylated, including imprinted loci and LTRs of Intracisternal A-particle retrotransposons (12, 13). Reconstituted mH2A-containing nucleosomes are resistant to ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling and transcription factor binding in vitro (14), and mH2A has recently been shown to repress RNA polymerase II-driven transcription at the level of transcriptional initiation (15).

Histone tails and histone fold domains are rich in PTMs, including but not limited to phosphorylation, methylation, ubiquitylation, acetylation, and ADP-ribosylation. The “histone code” hypothesis has been proposed to help explain the intricate patterns of PTMs and their biological outcomes (16–19). Phosphorylation of proteins, in general, is thought to be important for regulatory control of signaling networks and docking sites for binding proteins (20, 21). Histone phosphorylation, in particular, has long been believed to play a direct role in mitotic chromatin compaction or chromosome condensation (e.g., H1 linker phosphorylation; H3S10ph and H3S28ph), although causality relationships remain unclear (22–24). Connection of histone phosphorylation to other physiologically relevant processes that lie outside of mitosis, such as apoptosis (H2BS14), DNA damage and repair (γH2A.X), and inducible gene activation (H3S10), are also well documented (25–27).

Histone variants allow variation in the composition of individual nucleosomes and also allow the cell to expand its PTM profile (4). Although histone variants play significant roles in chromatin regulation, little is known about the PTMs that associate with them. To begin to decipher the PTM signature of the mH2A, a combination of purification, mass spectrometry (MS), and immunological approaches was taken. Here, we report the identification of two phosphorylation sites on endogenously purified mH2A, both of which lie within the basic hinge region of mH2A: T128ph and S137ph, and we discuss the biological implications of this phosphorylation, in particular, S137ph.

Results

mH2A Is Phosphorylated in Its Basic Hinge Domain.

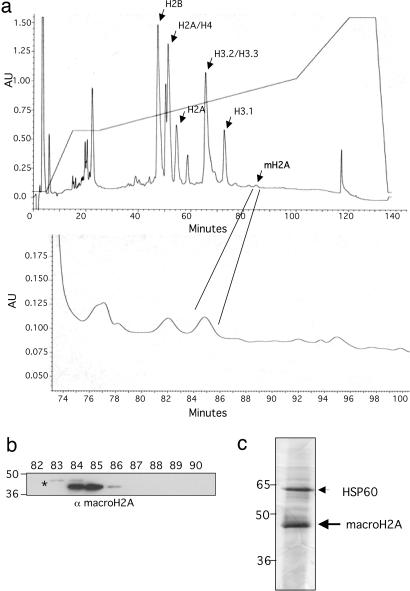

To enrich for endogenous mH2A, we used HEK293 cells, a female cell line that contains multiple inactive X chromosomes as a result of aneuploidy. Because mH2A is enriched on the Xi, we rationalized that this cell line would be a potentially enriched source of this minor variant. Isolation of histone variants from endogenous, nonoverexpressed sources can be challenging because of their low quantity in chromatin (<10% of total histone pool). To this end, mH2A was acid-extracted along with other core histones from HEK293 cells under asynchronous growth conditions. Total acid-extracted histones were fractionated by reverse-phase HPLC (Fig. 1a), and fractions containing mH2A were determined by using an antibody against mH2A1, which recognizes both mH2A1.1 and mH2A1.2 (Fig. 1b). mH2A1 elutes late in the HPLC chromatogram and is significantly less abundant than conventional histones (Fig. 1a). A slower-migrating, cross-reacting band above the mH2A1 signal was repeatedly observed by immunoblotting (IB) and is consistent with the monoubiquitylated form of mH2A given its size (an ≈8-kDa shift; Fig. 1b, asterisk) (28, 29). Multiple HPLC runs were carried out, and peak fractions from all runs were pooled for MS; a small portion of the total pool was examined by SDS/PAGE to determine the major constituents of this sample (Fig. 1c). MS analysis identified mH2A as the major component, and HSP60 as a likely contaminant (Fig. 1c). Both in-gel and in-solution enzymatic digestion was performed for MS to identify PTMs of mH2A1 [see supporting information (SI) Materials and Methods].

Fig. 1.

Purification of mH2A for PTM analysis. (a) Reverse-phase HPLC chromatogram of acid-extracted histones purified from HEK293 cells. Core conventional histone and mH2A peaks are labeled. Below is a blowup of the mH2A-containing fractions. The y axis is UV214 absorbance, the x axis is minutes of collection, and the acetonitrile gradient is depicted across the top. (b) HPLC fractions were screened by using an mH2A antibody that recognizes mH2A1.1 and 1.2 (not mH2A2). Fractions at 83–86 min contained mH2A1 (see mH2A peak in a, and compare peak size with core histones, e.g., H3 for relative abundance). Asterisk denotes a possible monoubiquitylated form of mH2A, which elutes slightly earlier than nonubiquitylated mH2A. Size markers are denoted on the left. (c) mH2A-containing fractions from multiple HPLC runs were pooled, and 1/50th was examined by SDS/PAGE (silver stain). The remainder was analyzed by both in-gel and in-solution MS methods for PTMs. mH2A was the major constituent of the pooled fractions (Hsp60 is a likely contaminant). Size markers are denoted on the left.

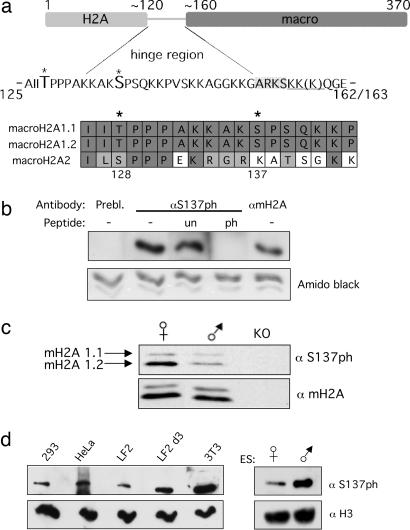

In the present work, particular attention was paid to the hinge region of mH2A1, a very basic stretch of amino acids that contains multiple potential phosphate acceptor residues (Fig. 2a, Upper). Because this region is lysine-rich, it is not amenable to enzymatic digestion with trypsin and therefore was targeted with endoproteinase GluC, generating a peptide of ≈40 aa (Fig. 2a, Upper and SI Fig. 5 a and b). Through our MS analysis, two phosphorylation sites were detected within the hinge of endogenous mH2A1: T128ph and S137ph, the latter of which is a previously unidentified modification of mH2A (for spectra, see SI Fig. 5 a and b). Intriguingly, a significant fraction (≈5%) of mH2A was phosphorylated at S137 in asynchronous cultures, a considerable amount given that there was no prior enrichment for phosphopeptides. Of note, S137ph was detected on peptides that contained either KK or KKK C-terminal to S137, which are forms of alternate splice selection (Fig. 2a, underlined) (6). The significance of this splice selection is unknown.

Fig. 2.

mH2A1 is phosphorylated in the hinge region on S137. (a) MS analysis identified two phosphorylation sites in the basic hinge region of mH2A1, T128 and S137 (asterisks). Sequence shown represents the peptide generated by GluC endopeptidase digestion. Peptides with both forms of alternate splice selection containing either KK or KKK were identified (underlined). The ARKS motif conserved in H3 is shaded. ClustalW alignment of the phosphorylated residues of mH2A 1.1, 1.2, and 2 is shown below. Note that phosphorylation potential exists for all three isoforms in the case of T128 but only for mH2A1.1 and 1.2 at S137. (b) mH2AS137ph antibody is specific as demonstrated by peptide competitions. HEK293 histones were used for peptide competitions with S137ph antibody. Membrane was cut into strips, probed with the antibodies indicated, and reassembled; Prebl., prebleed serum; un, unmodified peptide; and ph, phosphorylated peptide. mH2A IB was used as a control for size (last lane). Amido black staining of histones is used as a loading control. (c) Separation of mH2A isoforms demonstrates that both mH2A1 splice isoforms, mH2A 1.1 and 1.2, are phosphorylated at S137 in adult female and male mouse liver. (d) (Left) mH2AS137ph is found in all cell types examined: HEK293, HeLa, LF2 ES cells, 3-day retinoic acid-differentiated LF2 cells, and mouse 3T3 cells. (Right) Both male and female ES cells contain this PTM.

To investigate the biological implications of mH2AS137ph, a highly specific affinity-purified polyclonal antibody was generated. Peptide competitions demonstrated that a peptide phosphorylated at S137 could compete antibody reactivity when HEK293 histones were analyzed by IB, whereas the unmodified peptide could not (Fig. 2b). Furthermore, peptide competitions with various phosphorylated peptides from other histones such as H3S10ph, H3S28ph, and H3.3S31ph (SI Fig. 5c) and peptide dot blots and Luminex assays (data not shown) demonstrated specificity for mH2A phosphorylation.

mH2AS137ph Is a Prevalent PTM.

The hinge region of mH1A1.1 and 1.2 is identical, and we questioned whether both splice forms are phosphorylated on S137. However, because our MS analyses generated an identical peptide from mH2A1.1 and 1.2, we were unable to confirm whether the phosphorylation is present on one or both splice variants. Thus, we used SDS/PAGE to separate mH2A1 isoforms from adult mouse liver nuclei, a rich source of mH2A. Interestingly, both mH2A1.1 and 1.2 are phosphorylated at S137 in male and female liver (Fig. 2c). Adult mouse liver is largely devoid of dividing cells, and the presence of S137ph in this tissue may represent a potential role of mH2A in senescence because mH2A is also enriched in senescence-associated heterochromatin foci (11). Of note, S137ph signal is absent from mH2A knockout liver in IB, again demonstrating specificity of this antibody (Fig. 2c).

Although mH2A2 is not highly conserved with mH2A1 in the hinge region, it is also lysine-rich. Sequence alignments of the three mammalian mH2A isoforms show that T128 is replaced by a serine in mH2A2, a potentially phosphorylated residue (Fig. 2a, Lower). However, in the case of S137, mH2A2 contains a lysine residue (Fig. 2a, Lower). Thus, the ability of only mH2A1 to be phosphorylated at S137 may provide a unique role to this variant.

We next used the S137ph antibody to screen cell lines of different origin for its presence, and all cells tested contain this PTM (Fig. 2d). Interestingly, differentiated mouse ES cells (and 3T3s) contain more mH2AS137ph than undifferentiated ES cells, suggesting a potential role for this modification in chromatin changes throughout differentiation. S137ph is not exclusive to female cells because male ES cells also have significant amounts this modification (Fig. 2d, Right); it is also observed in male mouse liver (Fig. 2c). We note that although female liver has higher levels of S137ph than males, and the opposite trend occurs in ES cells, this difference may reflect variation in cell/tissue types. Taken together, these data suggested that the subpopulation of mH2A containing S137ph was not exclusive to the Xi, but rather that this modified form of mH2A has a distinct function within the chromatin template (see below).

mH2AS137ph Is Excluded from the Xi.

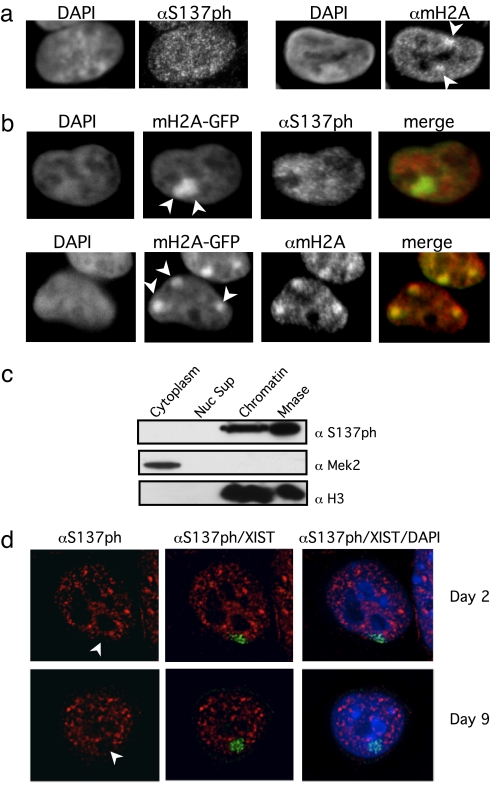

To test the above hypothesis directly, we performed immunofluorescence (IF) analyses in HEK293 cells with antibodies against S137ph and mH2A (Fig. 3a). Although mH2A staining showed two or three intensely stained foci (Xis), S137ph staining did not produce similar results. We next generated a HEK293 cell line stably expressing mH2A1.2 fused to GFP, allowing direct visualization of Xis. Again, IF analysis, by using antibodies in direct comparison with the mH2A-GFP fusion, showed that, whereas mH2A was enriched on the Xi, the phosphorylated form was not (Fig. 3b). This lack of enrichment is not caused by the inability of the GFP fusion protein to be phosphorylated on S137 (SI Fig. 5d). Although the localization of S137ph is not completely excluded from the Xi in all cases (≈75% Xis show no enrichment, with 148 Xis counted), this modification is not enriched on the Xi as seen for general mH2A antibody (Fig. 3b). Furthermore, S137ph is predominantly chromatin-associated as demonstrated by a chromatin fractionation assay and is released from chromatin by micrococcal nuclease digestion (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3.

mH2AS137ph is absent from the inactive X chromosome. (a) HEK293 cells were stained with antibodies to S137ph and mH2A. Arrows depict Xi chromosomes. DAPI stains are shown to the left of each staining. Note that HEK293 cells have multiple Xis. (b) S137ph is not enriched on the Xi in HEK293 cells. HEK293 cell lines containing stably expressed mH2A1.2-EGFP to mark the Xi (green) were stained with S137ph and mH2A antibodies (red). DAPI and merged images are shown; arrows depict Xis. (c) Chromatin fractionation and micrococcal nuclease (Mnase) digestion of chromatin in HEK293 cells. Antibodies to Mek2 (microtubule-associated kinase) and H3 are used as cytoplasmic and nuclear fractionation controls, respectively. (d) Female mouse ES cells display exclusion of S137ph from the Xi. ES cells were stained on day 2 and day 9 of retinoic acid-induced differentiation (before and after mH2A association with the Xi, respectively) for S137ph (red) and Xist RNA (by RNA FISH, green). Arrows depict Xis; DAPI (blue) merged images are shown.

To test the localization of S137ph mH2A during ES cell differentiation, we used a female mouse ES cell line (LF2) that inactivates one of its X chromosomes upon retinoic acid treatment (30). Because mH2A associates with the Xi late in the differentiation process [≈day 5 or 6 in LF2 cells (31)], we examined S137ph localization before (day 2) and after (day 9) mH2A associates with the Xi (Fig. 3d). In both cases, mH2AS137ph is absent from the Xi (marked by Xist RNA FISH; Fig. 3d), indicating that a unique pool of phosphorylated mH2A is excluded from this important epigenetically regulated heterochromatic structure. Interestingly, S137ph stains interphase nuclei in a highly punctate pattern, the significance of which is unclear; however, we observed some overlap with regions of active transcription in LF2 cells (visualized by RNA polymerase II staining; SI Fig. 6).

S137 Phosphorylation of mH2A Is Enriched During Mitosis.

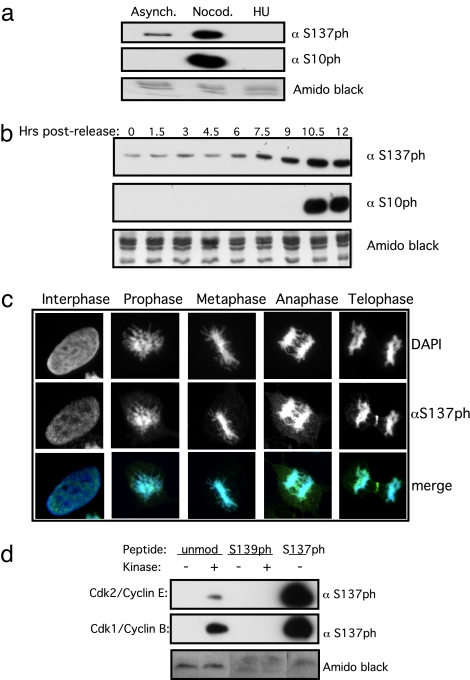

The absence of S137ph on the Xi raises the possibility that phosphorylation of mH2A in the hinge region might prevent its association with the Xi or certain forms of heterochromatin. To dissect the role of this PTM further, we examined three key cellular mechanisms linked to phosphorylation of other histones: (i) DNA damage response, S139ph on H2A.X; (ii) apoptotic chromatin, H2BS14ph; and (iii) chromatin condensation during mitosis, S10ph and S28ph on H3 (22–26, 32). We examined the levels of S137ph after induction of apoptosis by etoposide treatment and DNA damage induced by ionizing irradiation, and we observed no change in S137ph levels after either treatment (SI Fig. 7 a and b). We did, however, observe a consistent change in the levels of S137ph during cell cycle progression. Although asynchronous cell populations contain S137ph (Fig. 2d), the levels increase significantly upon nocodazole treatment, whereas an S phase block with hydroxyurea results in very low levels (Fig. 4a). Analyses of synchronized HeLa cells induced by a double thymidine block procedure confirmed that the levels of mH2AS137ph increase during mitosis (Fig. 4b). These IB results were confirmed by IF studies, which showed strong staining of mitotic chromosomes in U2OS cells compared with interphase nuclei (Fig. 4c); similar results were seen with HeLa cells (SI Fig. 7c).

Fig. 4.

mH2AS137ph is enriched during mitosis. (a) Asynchronous HeLa cells contain mH2AS137ph, and its levels increase after nocodazole treatment (mitotic cells). Comparably lower levels are seen after hydroxyurea (HU) treatment (S phase). H3S10ph is used as a mitotic marker. Amido black staining of histones is used as a loading control. (b) A double-thymidine block and subsequent release of synchronized HeLa cells throughout the cell cycle demonstrate an increase in S137ph levels during mitosis (see mitotic marker H3S10ph). Amido black staining of histones is used as a loading control. (c) IF of U2OS cells shows staining of S137ph throughout interphase and different stages of mitosis. (Top) DAPI stains. (Middle) S137ph. (Bottom) Merges. (d) In vitro kinase assays demonstrate Cdk2/cyclin E and Cdk1/cyclin B kinase activity toward an unmodified mH2A1 peptide containing S137. Peptides with the same backbone phosphorylated at S139 prevent S137 phosphorylation. An S137ph peptide was used as a positive control for S137ph antibody signal. Amido black staining of peptides is used as a loading control.

Phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of many substrates are well documented to mediate large-scale changes in cellular organization during the cell cycle. Because mH2AS137ph is observed by IB throughout the cell cycle and in IF staining during interphase, we suggest that the role of this mark is not limited to mitosis. In keeping, other well characterized histone phosphorylation events exhibit complex relationships during the cell cycle. For example, H3S10 and S28 are phosphorylated during periods of immediate–early gene induction or mitosis (23, 27). The timing of mH2AS137 phosphorylation resembles that of linker histone H1, which is present during interphase and becomes hyperphosphorylated during mitosis (22). Because S137ph is next to a proline residue (Fig. 2a) and appears similar in timing to cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk)-mediated H1 phosphorylation, we suspected that S137 phosphorylation is also catalyzed by Cdks. In vitro kinase assays demonstrate that recombinant Cdk complexes, including Cdk2/cyclin E and Cdk1/cyclin B (S phase and mitotic regulators, respectively) can phosphorylate an mH2A peptide containing an unmodified S137 residue (Fig. 4d). Interestingly, phosphorylation of nearby S139 (a currently unidentified mH2A PTM) prevents S137 phosphorylation (Fig. 4d) and may represent a switching mechanism for potential binding effectors. This effect is not caused by epitope occlusion by S139ph because S137 phosphorylation is also reduced on this peptide in radioactive kinase assays (data not shown). Other Cdk/cyclin combinations can also phosphorylate the unmodified peptide, whereas S/T kinases such as casein kinase II and tyrosine kinases such as Wee1 are incapable of phosphorylating the same peptide in parallel assays (data not shown). Because Cdks can compensate for the loss of other Cdks during the cell cycle, it has been difficult to assess which Cdk is responsible for S137 phosphorylation in vivo, and it remains an important challenge for the future.

Discussion

Histone variants have great potential to alter the nucleosome in what has recently been described as a potential “nucleosome code” (4). Such changes can be structural and/or charge-related in nature and derived from unique sequence elements in the variants themselves and/or effects of their PTMs. PTMs of certain histone variants have been well documented, such as phosphorylation of H2A.X in response to DNA damage (26). Nevertheless, PTMs of other H2A variants, such as mH2A, are just beginning to be uncovered. For example, MS approaches have recently uncovered monoubiquitylation of K115 on overexpressed mH2A1.2, a site analogous to K119ub of histone H2A (28, 29). Methylation of K17, K122, and K238 has been reported, and so has phosphorylation of T128, a site verified by us in this work (29). mH2A is also ADP-ribosylated, as demonstrated by immunological approaches (33). However, it now remains a challenge to understand the biological roles of these mH2A PTMs and those of other histones, variant or nonvariant.

Although a role for mH2A in transcriptional repression and X inactivation has been well documented, recent studies suggest that mH2A has roles beyond these processes. Although mH2A is concentrated on the Xi, it is also widely distributed throughout chromatin and localizes to other nuclear domains, exists in vertebrate species that do not undergo X inactivation, and is expressed to similar degrees in males and females (9, 33, 34). Moreover, whereas mH2A1 knockout mice are viable, fertile, and do not display X inactivation defects (mH2A2 is still present), a set of genes does exhibit increased expression levels during the transition from newborn to young-adult animals (35). This finding suggests that mH2A1 is not restricted to large-scale gene silencing and chromosome inactivation, but it also fine tunes expression levels of specific genes through development. One way in which these diverse roles of mH2A might be orchestrated is through its PTMs.

Here, we report the identification of mH2A phosphorylation sites. S137ph appears to contribute to Xi-independent chromatin changes, such as chromatin condensation during mitosis. Another intriguing possibility is that phosphorylation of mH2A regulates RNA binding. S137ph is found in the hinge region of mH2A, which has been suggested to bind nucleic acids (6). Interestingly, heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) also has a lysine-rich hinge domain (between its chromo- and chromoshadow domains) that is phosphorylated in vivo (36). The HP1 hinge domain has been shown to bind RNA in vitro, and RNase treatment of mammalian cells releases HP1 from chromatin (37, 38). In keeping, we propose that mH2A may bind RNA through its hinge domain, and the resulting negative charge caused by phosphorylation (T128ph, S137ph, and/or yet unidentified sites) might abrogate its ability to bind RNA, consistent with its exclusion from the Xi. Although the ability of mH2A (and its hinge domain) to bind RNA is unclear, several studies have shown that its localization to the Xi depends on the Xist RNA: conditional deletion of Xist during X inactivation or abolishing the ability of Xist to bind the Xi prevent mH2A association with the Xi, and ectopic expression of Xist on autosomes results in the recruitment of mH2A to these ectopic sites (39–41).

Intriguingly, we also recognized a motif within the hinge of mH2A1 that is similar to the H3 tail, a conserved “ARKS” cassette in which H3K9/S10 and H3K27/S28 residues reside (Fig. 2a, shaded). If modified by methylation (K156) and/or phosphorylation (S157), respectively, the mH2A ARKS motif might be analogous to the well studied modifications on histone H3 that mediate HP1 (K9me3) and Polycomb (K27me3) binding, with phosphorylation at adjacent serines (S10 and S28) playing a role in mitosis (23, 24, 42). To date, we have not detected these modifications by MS analysis, but we cannot exclude the possibility that these PTMs exist in low abundance (<0.1% of total mH2A) or take place only during certain cell cycle phases. Interestingly, a “methyl/phos histone mimic” corresponding to the above motif has recently been identified in the histone methyltransferase G9a, suggesting a broader role for this motif (43).

Our principal interest in mH2A stems from the fact that in mammals, it is preferentially concentrated on the Xi in females, suggestive of a role in transcriptionally repressed chromatin (9). However, the studies reported here point to a potential role of mH2A and its hinge-directed phosphorylation in a role(s) outside Xi biology. Based on the emerging literature, we favor the view that mH2AS137ph and potentially other hinge-based phosphorylation sites regulate critical interactions with effector molecules that, in turn, govern the association of mH2A with key genetic elements like the Xi. A stated prediction of the histone code hypothesis is that effector-binding proteins engage the appropriately modified histone tails (18). The incorporation or removal of histone variants, each potentially decorated with its own PTM signature, might greatly increase the regulatory options of the epigenome, and we look forward to experimental tests of this hypothesis in the future.

Materials and Methods

Histone Isolation and Purification.

Histone isolation was performed essentially as described in ref. 44 and SI Materials and Methods. Histones were purified by RP-HPLC and screened for mH2A by IB, and positive fractions were pooled for MS analysis (see SI Materials and Methods).

IB and IF.

For antibodies used in this work, see SI Materials and Methods. Peptide competitions for IB were performed by incubating S137ph antibody with each peptide at 2 μg/ml for 2 h at room temperature before overnight incubation with the membrane. IF analysis on HEK293 cells was carried out by using poly-l-lysine (Sigma)-covered slips, fixed in 2% formaldehyde, permeabilized, and stained. Cells were analyzed on Axioskop 2 plus and Axioplan 2 microscopes (Zeiss). IF and RNA FISH on female ES cells (LF2) were performed as described in ref. 31, and cells were analyzed on a Deltavision microscopy system (Applied Precision).

Chromatin Fractionation and Separation of mH2A Isoforms.

Chromatin fractionation was performed as described in ref. 45. Mouse liver mH2A isoforms were separated as described in ref. 35.

Cell Culture and Cell Cycle Arrest.

Cell lines were grown under standard conditions (SI Materials and Methods). Rat mH2A1.2 (95% similar to human; GenBank accession no. U79139) was cloned into EGFP-N1 (Clontech), generating a C-terminal EGFP tag. Stable HEK293 cell lines were created by neomycin selection. Nocodazole-arrested HeLa cells were treated with 200 ng/ml inocodazol (Sigma) for 16 h and harvested by mitotic shake off. HeLa cells were arrested in G1/S by double-thymidine block with 2 mM thymidine for 16 h, released for 9 h, and blocked for 16 h. Hydroxyurea block was used to synchronize cells in S phase by treating for 20 h with 2 mM hydroxyurea.

Kinase Assays.

Unmodified and phosphorylated mH2A peptides (amino acid 132–142) were incubated with 10–40 ng of recombinant Cdk/cyclin complexes (Millipore) and ATP (500 μM) for 1 h at 30°C. Recombinant H1 was used as a positive control for Cdk reactions (data not shown). Detailed reaction conditions can be found at the distributor's website.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.

We thank David Shechter, Andrew Xiao, Sandra Hake, Elizabeth Duncan, Ping Chi, and Monika Kauer (all presently or previously at The Rockefeller University) for advice and reagents; Holger Dormann and Sandra Hake for critical reading of the manuscript; The Rockefeller University Bio-Imaging Facility for microscopy assistance and Proteomics Resource Center for peptide synthesis; Weronika Prusisz for technical assistance; and Millipore antibody development scientists for generation of αmH2AS137ph (catalog no. 09-018). This work was funded by High-Throughput Epigenetic Regulatory Organization in Chromatin (HEROIC), an integrated project funded by the European Union under Framework Program LSHG-CT-2005-018883 (J.C.C. and E.H.), by a Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale fellowship (to J.C.C.) and Equipe Fondation pour la Recherche program (E.H.), and by National Insitututes of Health Grants GM49351 (to J.R.P), GM37537 (to D.F.H), and GM40922 (to C.D.A).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0711632105/DC1.

References

- 1.Sarma K, Reinberg D. Histone variants meet their match. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:139–149. doi: 10.1038/nrm1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pusarla RH, Bhargava P. Histones in functional diversification: Core histone variants. FEBS J. 2005;272:5149–5168. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamakaka RT, Biggins S. Histone variants: Deviants? Genes Dev. 2005;19:295–310. doi: 10.1101/gad.1272805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernstein E, Hake SB. The nucleosome: A little variation goes a long way. Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;84:505–517. doi: 10.1139/o06-085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pehrson JR, Fried VA. MacroH2A, a core histone containing a large nonhistone region. Science. 1992;257:1398–1400. doi: 10.1126/science.1529340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costanzi C, Pehrson JR. MacroH2A2, a new member of the macroH2A core histone family. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:21776–21784. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010919200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chadwick BP, Willard HF. Histone H2A variants and the inactive X chromosome: Identification of a second macroH2A variant. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:1101–1113. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.10.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kustatscher G, Hothorn M, Pugieux C, Scheffzek K, Ladurner AG. Splicing regulates NAD metabolite binding to histone macroH2A. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:624–625. doi: 10.1038/nsmb956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costanzi C, Pehrson JR. Histone macroH2A1 is concentrated in the inactive X chromosome of female mammals. Nature. 1998;393:599–601. doi: 10.1038/31275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heard E, Disteche CM. Dosage compensation in mammals: Fine-tuning the expression of the X chromosome. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1848–1867. doi: 10.1101/gad.1422906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang R, et al. Formation of macroH2A-containing senescence-associated heterochromatin foci and senescence driven by ASF1a and HIRA. Dev Cell. 2005;8:19–30. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choo JH, Kim JD, Chung JH, Stubbs L, Kim J. Allele-specific deposition of macroH2A1 in imprinting control regions. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:717–724. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Damelin M, Bestor TH. Biological functions of DNA methyltransferase 1 require its methyltransferase activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:3891–3899. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00036-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Angelov D, et al. The histone variant macroH2A interferes with transcription factor binding and SWI/SNF nucleosome remodeling. Mol Cell. 2003;11:1033–1041. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00100-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doyen CM, et al. Mechanism of polymerase II transcription repression by the histone variant macroH2A. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:1156–1164. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.3.1156-1164.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turner BM. Decoding the nucleosome. Cell. 1993;75:5–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turner BM. Histone acetylation and an epigenetic code. BioEssays. 2000;22:836–845. doi: 10.1002/1521-1878(200009)22:9<836::AID-BIES9>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strahl BD, Allis CD. The language of covalent histone modifications. Nature. 2000;403:41–45. doi: 10.1038/47412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jenuwein T, Allis CD. Translating the histone code. Science. 2001;293:1074–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1063127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graves JD, Krebs EG. Protein phosphorylation and signal transduction. Pharmacol Ther. 1999;82:111–121. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(98)00056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seet BT, Dikic I, Zhou MM, Pawson T. Reading protein modifications with interaction domains. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:473–483. doi: 10.1038/nrm1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Holde KE. In: Chromatin. Rich A, editor. New York: Springer; 1988. pp. 125–136. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prigent C, Dimitrov S. Phosphorylation of serine 10 in histone H3, what for? J Cell Sci. 2003;116:3677–3685. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goto H, Yasui Y, Nigg EA, Inagaki M. Aurora-B phosphorylates histone H3 at serine 28 with regard to the mitotic chromosome condensation. Genes Cells. 2002;7:11–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1356-9597.2001.00498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheung WL, et al. Apoptotic phosphorylation of histone H2B is mediated by mammalian sterile twenty kinase. Cell. 2003;113:507–517. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00355-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Redon C, et al. Histone H2A variants H2AX and H2AZ. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2002;12:162–169. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(02)00282-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clayton AL, Mahadevan LC. MAP kinase-mediated phosphoacetylation of histone H3 and inducible gene regulation. FEBS Lett. 2003;546:51–58. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00451-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ogawa Y, et al. Histone variant macroH2A1.2 is monoubiquitinated at its histone domain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;336:204–209. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chu F, et al. Mapping post-translational modifications of the histone variant macroH2A1 using tandem mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteom. 2006;5:194–203. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500285-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rougeulle C, et al. Differential histone H3 Lys-9 and Lys-27 methylation profiles on the X chromosome. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5475–5484. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.12.5475-5484.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chaumeil J, Okamoto I, Guggiari M, Heard E. Integrated kinetics of X chromosome inactivation in differentiating embryonic stem cells. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2002;99:75–84. doi: 10.1159/000071577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crosio C, et al. Mitotic phosphorylation of histone H3: Spatio-temporal regulation by mammalian Aurora kinases. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:874–885. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.3.874-885.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abbott DW, Chadwick BP, Thambirajah AA, Ausio J. Beyond the Xi: MacroH2A chromatin distribution and post-translational modification in an avian system. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:16437–16445. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500170200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rasmussen TP, et al. Messenger RNAs encoding mouse histone macroH2A1 isoforms are expressed at similar levels in male and female cells and result from alternative splicing. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:3685–3689. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.18.3685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Changolkar LN, et al. Developmental changes in histone macroH2A1-mediated gene regulation. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:2758–2764. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02334-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lomberk G, Bensi D, Fernandez-Zapico ME, Urrutia R. Evidence for the existence of an HP1-mediated subcode within the histone code. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:407–415. doi: 10.1038/ncb1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muchardt C, et al. Coordinated methyl and RNA binding is required for heterochromatin localization of mammalian HP1α. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:975–981. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maison C, et al. Higher-order structure in pericentric heterochromatin involves a distinct pattern of histone modification and an RNA component. Nat Genet. 2002;30:329–334. doi: 10.1038/ng843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Csankovszki G, Panning B, Bates B, Pehrson JR, Jaenisch R. Conditional deletion of Xist disrupts histone macroH2A localization but not maintenance of X inactivation. Nat Genet. 1999;22:323–324. doi: 10.1038/11887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rasmussen TP, Wutz AP, Pehrson JR, Jaenisch RR. Expression of Xist RNA is sufficient to initiate macrochromatin body formation. Chromosoma. 2001;110:411–420. doi: 10.1007/s004120100158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beletskii A, Hong YK, Pehrson J, Egholm M, Strauss WM. PNA interference mapping demonstrates functional domains in the noncoding RNA Xist. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:9215–9220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161173098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fischle W, et al. Molecular basis for the discrimination of repressive methyllysine marks in histone H3 by Polycomb and HP1 chromodomains. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1870–1881. doi: 10.1101/gad.1110503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sampath SC, et al. Methylation of a histone mimic within the histone methyltransferase G9a regulates protein complex assembly. Mol Cell. 2007;27:596–608. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shechter D, Dormann HL, Allis CD, Hake SB. Extraction, purification and analysis of histones. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:1445–1457. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bernstein E, et al. Mouse Polycomb proteins bind differentially to methylated histone H3 and RNA, are enriched in facultative heterochromatin. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:2560–2569. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.7.2560-2569.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.