Abstract

The coculture of cells expressing the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein complex (Env) with cells expressing CD4 results into cell fusion, deregulated mitosis, and subsequent cell death. Here, we show that NF-κB, p53, and AP1 are activated in Env-elicited apoptosis. The nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) super repressor had an antimitotic and antiapoptotic effect and prevented the Env-elicited phosphorylation of p53 on serine 15 and 46, as well as the activation of AP1. Transfection with dominant-negative p53 abolished apoptosis and AP1 activation. Signs of NF-κB and p53 activation were also detected in lymph node biopsies from HIV-1–infected individuals. Microarrays revealed that most (85%) of the transcriptional effects of HIV-1 Env were blocked by the p53 inhibitor pifithrin-α. Macroarrays led to the identification of several Env-elicited, p53-dependent proapoptotic transcripts, in particular Puma, a proapoptotic “BH3-only” protein from the Bcl-2 family known to activate Bax/Bak. Down modulation of Puma by antisense oligonucleotides, as well as RNA interference of Bax and Bak, prevented Env-induced apoptosis. HIV-1–infected primary lymphoblasts up-regulated Puma in vitro. Moreover, circulating CD4+ lymphocytes from untreated, HIV-1–infected donors contained enhanced amounts of Puma protein, and these elevated Puma levels dropped upon antiretroviral therapy. Altogether, these data indicate that NF-κB and p53 cooperate as the dominant proapoptotic transcription factors participating in HIV-1 infection.

Keywords: Bax, mitochondria, NF-κB, Puma, Bak

Introduction

AIDS caused by HIV-1 involves the apoptotic destruction of lymphocytes (1–3). The envelope glycoprotein complex (Env) constitutes one of the major apoptosis inducers encoded by the HIV-1. The soluble Env derivative gp120 can induce apoptosis through interactions with suitable surface receptors (3, 4). HIV-1–infected cells that express mature Env (the gp120/gp41 complex) on the surface can also kill uninfected cells expressing the receptor (CD4) and the coreceptor (CXCR4 for lymphotropic Env variants, CCR5 for monocytotropic Env variants). This type of bystander killing is obtained by at least two distinct mechanisms. First, the two interacting cells (one that expresses Env and the other that expresses CD4 plus the coreceptor) may not fuse entirely and simply exchange plasma membrane lipids, after a sort of hemi-fusion process, followed by caspase-independent death (5). Second, the two cells can undergo cytoplasmic fusion (cytogamy), thus forming a syncytium, and undergo nuclear fusion (karyogamy) and apoptosis (6). In syncytia, the cyclin B1–dependent kinase 1 (Cdk1) is activated, a process that is required for karyogamy and that culminates in the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)–mediated phosphorylation of p53 on serine 15. The transcriptional activation of p53 results in the expression of proapoptotic proteins, including Bax and cell death (7, 8). p53 and Bax have also been found to participate in the death of HIV-1–infected primary lymphoblasts (9, 10). Both the syncytium-dependent and -independent Env-induced apoptosis are suppressed by inhibitors of the gp41- and gp120-mediated coreceptor interactions (5, 6). Moreover, both are reduced by transfection with the Bax antagonist Bcl-2 (5, 6). In contrast, only the syncytium-dependent cell death can be blocked by inhibitors of Cdk1 (e.g., roscovitine), mTOR (e.g., rapamycin), or p53 (e.g., cyclic pifithrin-α; references 7, 8).

Some of the characteristics of syncytium-induced apoptosis, namely aberrant cyclin B expression (11), overexpression/activation of mTOR (7), phosphorylation of p53 on serine 15 (7, 11), and destabilization of mitochondrial membranes (6), also affect a subset of lymph node and peripheral blood lymphocytes from HIV-1–infected donors, correlating with viral load (7, 11–13). This suggests that the proapoptotic signal transduction pathway, which can be studied in Env-elicited syncytia, reflects, to some extent, the HIV-1–stimulated cell death, as observable among circulating lymphocytes. Based on this premise, we decided to further explore the proapoptotic signal transduction pathway participating in Env-induced syncytium-dependent cell killing. Therefore, we analyzed Env-elicited changes in the transcriptome and established the preponderant role of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) as well as of p53 as proapoptotic transcription factors in HIV-1–induced cell death. Moreover, we identified Puma as a proapoptotic, p53-inducible protein that is critical for in Env-induced apoptosis. The induction of Puma was not restricted to Env-elicited syncytia but was also found in Env-triggered syncytium-independent cell death in vitro. In addition, Puma expression was induced in HIV-1–infected patients.

Materials and Methods

Cells and Culture Conditions for Apoptosis Induction.

HeLa cells stably transfected with the Env gene of HIV-1 LAI (HeLa Env) and HeLa cells transfected with CD4 (HeLa CD4) were cocultured at a 1:1 ratio (6) in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, l-glutamine, in the absence or presence of 1 μM roscovitin, 1 μM rapamycin (Sigma-Aldrich), 10 μM cyclic pifithrin-α, 5 μM MG132 (Calbiochem), the NF-κB inhibitory peptide SN50, or its negative control SN50M (20 μM; BIOMOL Research Laboratories, Inc.). HeLa/U937 cell cocultures were performed at different ratios (6). U937 or Jurkat cells were cultured with 500 ng/ml recombinant gp120 protein.

Plasmids, Transfection, and Transcription Factor Profiling.

For transcription factor profiling, HeLa CD4 cells were transfected with different luciferase constructs (Mercury™ pathway profiling system from CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc.; 2 μg DNA) using Lipofectamine 2000™ (2 μl; Invitrogen) 24 h before fusion with HeLa Env cells (25 × 104 in 2 ml), and the luciferase activity was measured 24 h later using the luciferase reporter assay kit from CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc. Transfection with pcDNA3.1 vector only, WT, dominant-negative (DN) Cdk1 mutant (14), the IκB super-repressor (IKSR; a gift from L. Schmitz, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland), p53 DN plasmids (p53H273; a gift from T. Soussi, Institut Curie, Paris, France), or a p53-responsive enhanced green fluorescent protein (GFP) plasmid (a gift from K. Wiman, Karolinska Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden) was performed 24 h before coculture of HeLa CD4 and HeLa Env cells. The frequency of GFP-expressing cells was assessed by cytofluorometry on a FACSVantage™ (Becton Dickinson) equipped with a 100-μm nozzle, allowing for the analysis of relatively large cells. Afterwards, cells were counterstained with 10 μg/ml Hoechst 33324 (15 min), and the FACS® gates were set on syncytia (i.e., cells with a DNA content >4 n) (11).

Immunofluorescence and Cytofluorometry.

Rabbit antisera specific for p53S15P, p53S46P (Cell Signaling Technology), or the NH2 terminus of Bax (N20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) were used on paraformaldehyde (4% wt:vol) and picric acid–fixed (0.19% vol:vol) cells (15) and revealed with a goat anti–rabbit IgG conjugated to Alexa 568 (red) or Alexa 488 (green) fluorochromes obtained from Molecular Probes. Cells were also stained for the detection of the NH2 terminus of Bak (Ab1; Oncogene Research Products), p53S15P (mAb), cyclin B1 (mAb; BD Transduction Laboratories), and IκBαS32/36P (mAb; Cell Signaling Technology) revealed by anti–mouse IgG Alexa conjugates. Cells were counterstained with Hoechst 33324, which allows discernment of karyogamy and apoptotic chromatin condensation (11).

Immunoblots.

Samples were prepared from HeLa Env and HeLa CD4 single cells mixed at a 1:1 ratio in lysis buffer (single cells control) or from HeLa Env/CD4 syncytia. Protein samples from HeLa Env and U937 mixed at different ratios were also prepared and subjected to immunoblot analysis. Aliquots of protein extracts (40 μg) were subjected to immunoblots using antibodies specific for IκBαS32/36P, p53S15P, p53S46P, p53 (Cell Signaling Technology), Puma (rabbit anti–human Puma antisera; United States Biological or Orbigen; and mouse anti–human Puma antibody; Upstate Biotechnology; all gave similar results), β-tubulin (mAb; Sigma-Aldrich), or glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH, mAb; Chemicon).

Microarrays, Macroarrays, and Quantitative RT-PCR.

HeLa CD4 and HeLa Env cells were labeled with CellTracker™ red or CellTracker™ green (15 μM, 30 min at 37°C), respectively, and washed extensively before coculture. After 18 or 36 h of coculture, in the presence or absence of 10 μM cyclic pifithrin-α (readded once upon 24 h), the cells were subjected to FACS® purification of syncytia (which are double positive) or single cells, as described previously (11). mRNA preparations were obtained with the RNeasy Mini kit (QIAGEN), quality-controlled with a bioanalyzer (model 2100; Agilent Technologies), alternatively labeled with Cy3/Cy5 fluorochromes, mixed for pairwise comparisons, and hybridized to 19-k human arrays. Arrays were scanned with a confocal laser scanner (ScanArray model 4000; PerkinElmer), quantified with software (QuantArray; PerkinElmer) at the Ontario Cancer Institute Microarray Center (http://www.microarrays.ca), and analyzed with GeneTraffic software (Iobion Informatics). All experiments were performed in triplicates, while switching the Cy3/Cy5 labeling (six data points for each pair-wise comparison) and up-regulations by 50% or down-regulations by 30% were listed. Data showing the transcriptional modification of genes with unknown function are listed in Table SI (available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20031216/DC1). Macroarrays were performed using a TranSignal™ p53 target gene array (Panomics) and quantified using the National Institutes of Health image software. For quantitative RT-PCR, cDNAs were synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA with reverse transcriptase MuLV (Roche). The TaqMan universal PCR was performed on an ABI PRISM® 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems) following the manufacturer's instructions. The following primer sequences were used: bcl-2, forward, 5′-CATGTGTGTGGAGAGCGTCAA-3′, reverse, 5′-CAGGTGTGCAGGTGCCG-3′; bax α, forward, 5′-CCAAGGTGCCGGAACTGAT-3′, reverse, 5′-AAGTAGGAGAGGAGGCCGTCC-3′; bax β, forward, 5′-CCAAGGTGCCGGAACTGAT-3′, reverse, 5′-GAGGAGGCTTGAGGAGTCTCA-3′; bak, forward, 5′-ACCGACGCKATGACTCAGAGTTC-3′, reverse, 5′-ACACGGCACCAATTGATG-3′; and puma (predeveloped Taqman Assays Reagents; www.appliedbiosystems.com).

Antisense Constructs and RNA Interference.

HPLC-purified antisense phosphorothioate oligonucleotides (antisense Puma, 5′-CATCCTTCTCATACTTTC-3′; and control, CTTTCATACTCTTCCTAC-3′; GeneSet Oligos) (100 nM) were transfected with Oligofectamine (Invitrogen) into HeLa CD4 cells 24 h before coculture with HeLa Env cells. RNA interference of Bax and Bak expression was obtained by means of double-stranded morpholino oligonucleotides (GeneSet Oligos) specific for Bax (sense strand, 5′-rCUrgrgrArCrArgUrArArCrAUrgrgrArgrCTT-3′) or Bak (sense strand, 5′-UrgrgUrCrCrCrAUrCrCUrgrArArCrgUrgTT-3′), transfected into both HeLa CD4 and HeLa Env cells 48 h before coculture.

Patients' Samples and In Vitro Infection with HIV-1.

Axillary lymph node biopsies or peripheral blood samples were obtained from healthy and HIV-1–infected individuals (all males, mean age = 36 yr), who were naive for highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) with a plasma viral load >20,000 copies/ml or were receiving HAART with a viral load <5,000 copies/ml. Plasma HIV-1 RNA levels were determined by the bDNA procedure (Versant HIV RNA 3.0) according to the manufacturer's instructions (Bayer). None among the HIV-1+ patients received interferons, glucocorticoids, was positive for hepatitis B or C, or exhibited signs of autoimmunity. PBMCs were isolated by Ficoll/Hypaque (Amersham Biosciences) centrifugation of heparinized blood from either healthy donors and HIV-seropositive individuals and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, pH 7.2. Biopsies were fixed with 10% formalin, dehydrated, and paraffin embedded. Deparaffinized tissue sections and PBMCs were subjected to immunocytochemistry with antibodies specific for p53S46P, IκBαS32/36P, or PUMA and counterstained with hematoxylin. PBMCs were treated with TRIzol (Invitrogen) to extract total proteins, followed by immunoblot analysis. Alternatively, freshly purified PBMCs were stained with anti-CD4 antibody (FITC-labeled OKT3) and FACS® sorted, followed by protein extraction. Primary CD4+ lymphoblasts (10 × 106) cells (7) were incubated with the HIV-1LAI/IIIB strain or different clinical HIV-1 isolates (500 ng of p24; reference 16) for 4 h at 37°C. After washing out unabsorbed virus, cells (106 cells/ml) were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 20% FCS and 10 U/ml IL-2.

Online Supplemental Material.

The transcripts with unknown function that are modulated by Env-dependent syncytium formation, as compared with control HeLa cells, are listed in Table SI available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20031216/DC1.

Results

Transcription Factor Profiling of HIV-1 Env-elicited Apoptosis.

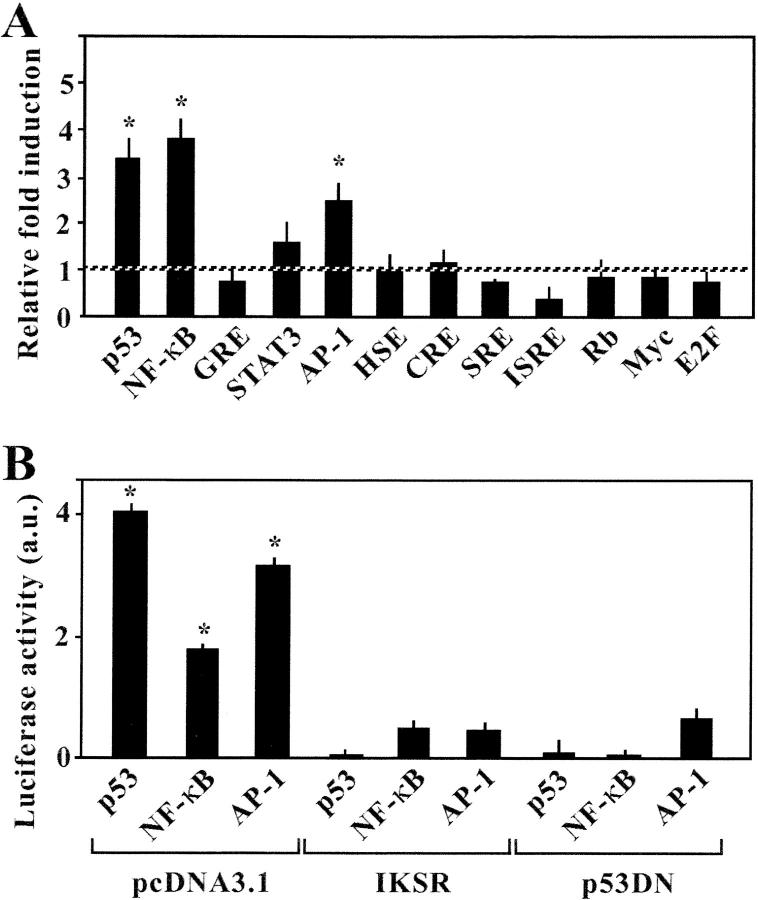

In a model culture system of syncytium-dependent cell death, HeLa cells stably transfected with the Env gene from HIV-1LAI/IIIb (HeLa Env) were fused by coculture with CD4/CXCR4-expressing HeLa cells (HeLa CD4; references 6, 7, 17, 18). Syncytium-induced transcriptional effects were monitored by transfecting each of the two cell lines with a series of luciferase reporter gene constructs containing promoter elements responsive to a series of different transcription factors. This approach revealed that, among a panel of 12 different transcription factors, only NF-κB, p53, and AP1 were activated by the Env-dependent syncytium formation (Fig. 1 A). To determine the hierarchy among these transcription factors, cells were cotransfected with the aforementioned luciferase reporter constructs as well as a nonphosphorylable mutant of IκB (IKSR; reference 19) or with a DN mutant of p53 (p53H273; reference 20). Both IKSR and p53H2731 abrogated the increase of NF-κB, p53, and AP1-dependent transcription found in syncytia (Fig. 1 B). These data point to an obligate cooperation between NF-κB and p53, upstream of AP1, in Env-elicited syncytia.

Figure 1.

Transcription factor profiling of syncytia elicited by HIV-Env. (A) Systematic analysis of transcription factors activated in syncytia. HeLa CD4 cells were transfected with luciferase constructs placed under the control of the indicated transcription factor. 24 h after transfection, cells were cultured alone (100% control value) or in the presence of HeLa Env cells, and the expression of luciferase was monitored 24 h later. Asterisks indicate a significant (P < 0.01; Student's t test) increase in the luciferase activity (mean ± SD; n = 3). (B) Mutual relationship among p53 and NF-κB. Cells were cotransfected with luciferase expression plasmids controlled by p53, NF-κB, or AP1 plus empty vector (pcDNA3.1) or the IκB super-repressor (IKSR) or a DN p53 (p53H273), and the increase in luciferase activities in syncytia (vs. single cells) was quantified. Results are representative of three independent experiments. Asterisks indicate significant induction of luciferase constructs.

NF-κB Is Required for Env-elicited Mitosis and p53 Activation.

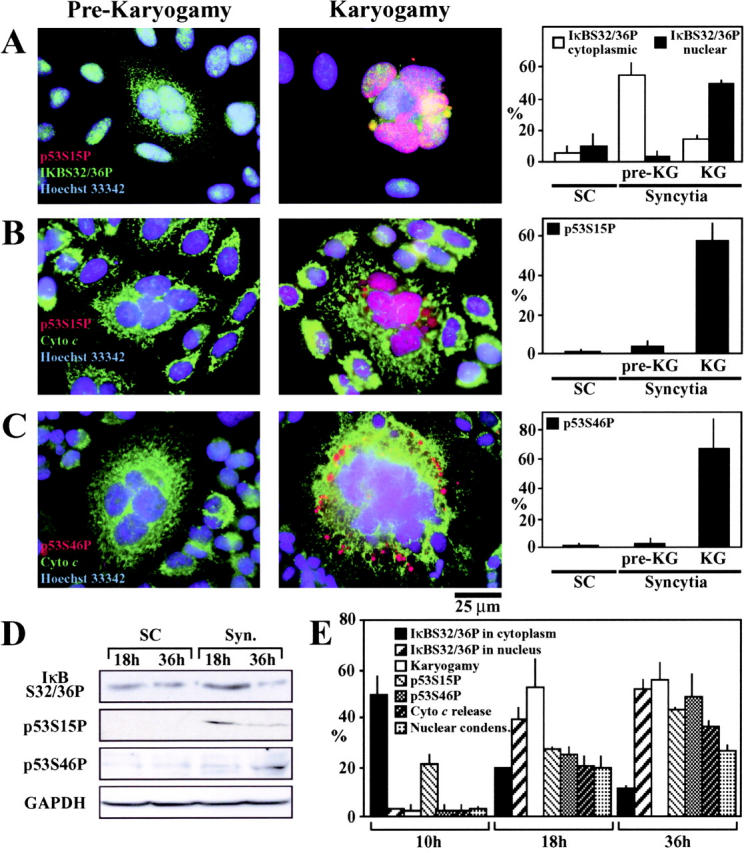

NF-κB is usually considered as an antiapoptotic transcription factor (21, 22). Intrigued by its putative implication in syncytial apoptosis, we further investigated the possible implication of NF-κB in syncytial apoptosis. Cytoplasmic fusion is followed by nuclear fusion (karyogamy) accompanying an aberrant, cyclin B1-dependent entry into mitosis (11, 18). This allows for the distinction of early (prekaryogamic) and late (karyogamic) syncytia. A significant fraction of prekaryogamic syncytia exhibited the phosphorylation of IκB on serine residues 32 and 36 (IκBS32/36P), as detectable with a phosphoneoepitope-specific antibody. IκBS32/36P was found in the cytoplasm of prekaryogamic syncytia. In karyogamic syncytia, IκBS32/36P was confined to the nucleus (Fig. 2 A). p53 was found to exhibit an activation-associated phosphorylation pattern, both on serine 15 (Fig. 2 B, p53S15P) and serine 46 (Fig. 2 C, p53S46P), only in karyogamic syncytia. Immunoblot analysis confirmed the phosphorylation of IκB and p53 (Fig. 2 D). Kinetic analysis confirmed a precise order of phosphorylation events (IκBS32/36P → p53S15P → p53S46P) (Fig. 2 E).

Figure 2.

Phosphorylation of IκBα and p53 in Env-elicited syncytia. (A–C) Representative immunofluorescence microphotographs of prekaryogamic and karyogamic syncytia (36 h) with antibodies specific for IκBαS32/36P (A), p53S15P (A and B), p53S46P (C), or cytochrome c (B and C). The frequency of the indicated phosphorylation events was determined both among single cells (SCs) and karyogamic (KG) or prekaryogamic syncytia. (D) Immunoblot confirmation of the phosphorylation of IκBαS32/36P, p53S15P, and p53S46P in syncytia. The immunodetection of GAPDH was performed to control equal loading. (E) Kinetic analysis of phosphorylation events. Syncytia (obtained by coculture of HeLa Env and HeLa CD4 cells during the indicated interval) were subjected to immunostainings as aforementioned, and the percentage of cells exhibiting the indicated parameters was quantified among the total population of syncytia.

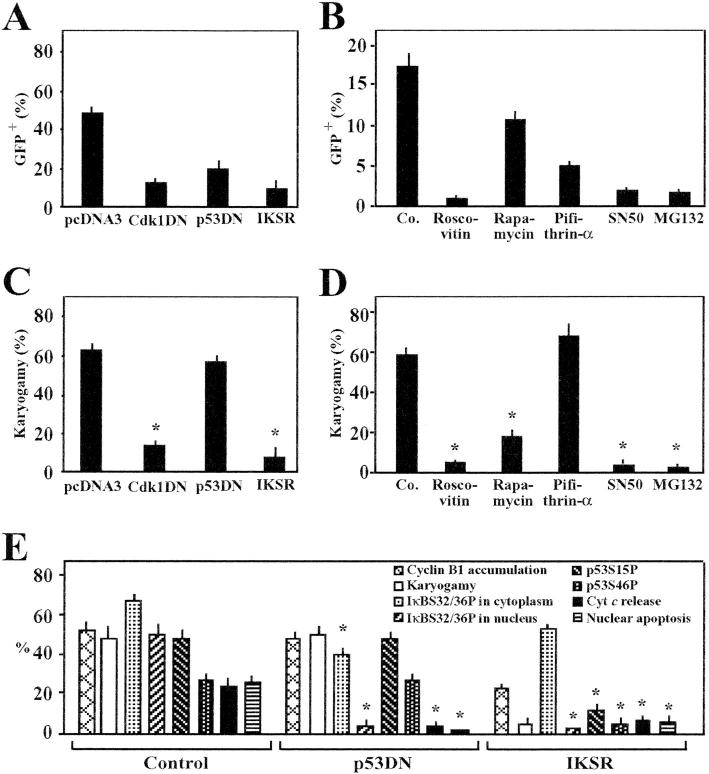

Transfection of HeLa CD4 and HeLa Env cells with a p53-inducible GFP construct allowed for the quantitative assessment of p53-dependent transcriptional effects within syncytia. p53-dependent transcription was strongly inhibited by transfection with IKSR (Fig. 3 A), as well as by pharmacological inhibition of the NF-κB translocation with SN50 (Fig. 3 B). Simultaneously, both IKSR (Fig. 3 C) and SN50 (Fig. 3 D) inhibited the emergence of karyogamic syncytia, suggesting that NF-κB is required for mitotic progression of syncytia. Indeed, NF-κB inhibition fully prevented the syncytial accumulation of cyclin B1, as determined by quantitative immunofluorescence analysis (Fig. 3 E). Inhibition of the Cdk1 by DN Cdk1 (Fig. 3 A) or roscovitine (Fig. 3 B) inhibited the p53-dependent transcription, while inhibiting karyogamy (Fig. 3, C and D). Altogether, these findings indicate that NF-κB is essential for the aberrant, cyclin B1/Cdk1-mediated entry into karyogamy that occurs upstream of p53 activation. The repression of NF-κB reduced the karyogamy-associated phosphorylation of p53 (both p53S15P and p53S46P). Moreover, transfection with DN p53 partially inhibited the phosphorylation of IκB and totally blocked its translocation into the nucleus (Fig. 3 E). These findings point again to an obligate cross-talk between p53 and NF-κB.

Figure 3.

Rules governing the activation of p53 in Env-elicited syncytia. (A) Genetic inhibition of p53-dependent transcription. HeLa CD4 cells were cotransfected with a p53-inducible GFP construct, together with vector only (pcDNA3.1), a dominant-negative (DN) Cdk1 mutant, DN p53 (p53H273), or IKSR. After 24 h, the cells were either left alone (single cells) or cocultured with HeLa Env cells for 36 h, followed by cytofluorometric determination of GFP. (B) Pharmacological inhibition of p53-dependent transcription. HeLa CD4 cells were transfected with a p53-inducible GFP construct. After 24 h, cells were cultured in the presence of the indicated agents, in the presence or absence of HeLa Env cells for 24 h, followed by determination of the frequency of GFP-expression single cells or syncytia. (C) Inhibition of karyogamy by IKSR. HeLa CD4 cells were transfected with the indicated constructs as in A, and the frequency of cells exhibiting nuclear fusion was scored upon coculture with HeLa Env cells. (D) Inhibition of karyogamy by NF-κB inhibitors. Syncytia were treated with various drugs as in B, and the frequency of karyogamic cells was scored. (E) Effect of IKSR and DN p53 on cyclin B1, karyogamy, phosphorylation of IκB or p53, and apoptotic parameters. Syncytia were generated as in A, after transfection with pcDNA3.1 (Control), IKSR, or DN p53, followed by immunofluorescence detection of cyclin B1. The frequency of syncytia exhibiting an increase in cyclin B immunostaining was determined in three independent experiments after 24 h of coculture. Moreover, the frequency of syncytia exhibiting positive cytoplasmic or nuclear IκBS32/36P staining, p53S15P or p53S46P, mitochondrial cytochrome c release, or nuclear apoptosis was determined. Asterisks indicate significant inhibitory effects (P < 0.01; paired Student's t test; mean ± SD; n = 3).

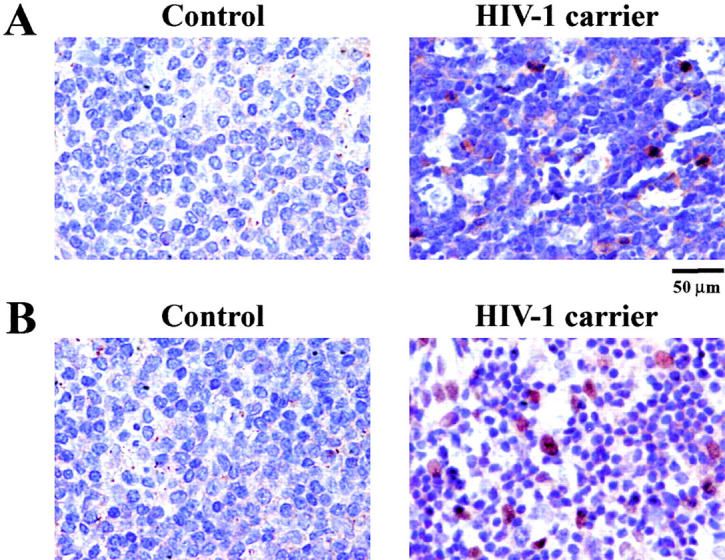

IκB phosphorylation was also detectable in lymph nodes from HIV-1 carriers (but not in those from uninfected controls), mainly among mitotic cells (Fig. 4 B). Moreover, the phosphorylation of p53S46P was induced by HIV-1 infection of primary CD4+ lymphoblasts (see below) and was detectable in lymph node biopsies from HIV-1 carriers (Fig. 4 A). Altogether, these data extend the notion of HIV-1–induced NF-κB activation and p53 activation.

Figure 4.

Phosphorylation of IκBα and p53 in lymph nodes from HIV-1 carriers. Lymph nodes from age- and sex-matched controls or untreated HIV-1 carriers were stained for the immunocytochemical detection (red) of IκBα (S32/36)P (A) and p53S46P (B). Nuclei are counterstained in blue. Similar results indicating a scattered p53S46 staining and staining of mitotic cells with IκBα(S32/36)P were found in three independent asymptomatic, untreated HIV-1–infected donors with a viremia of >105 copies/ml.

HIV-1 Env-elicited Transcriptional Effects Involve p53 and Lead to Puma Overexpression.

To further explore the implication of transcription factors in Env-induced syncytial apoptosis, microarrays were performed on HeLa Env/CD4 cocultures maintained for 18 or 36 h in the presence or absence of cyclic pifithrin-α, a chemical inhibitor of p53. 40 genes of known function (Table I) and 42 genes with unknown function (Table SI) were found to be significantly (by a factor of ≥1.5 or ≤0.67) induced or inhibited in syncytia, as compared with control cells cultured separately. The chemical inhibitor of p53 transactivation, cyclic pifithrin-α, was found to prevent these changes in transcription either at 18 or 36 h for 85% among these genes, indicating that p53 is indeed the principal transcription factor, whose activation directly or indirectly (via effects on other transcription factors) determines the pathophysiology of syncytial apoptosis.

Table I.

Classification of Modulated Genes with Known Function in Env-induced Syncytia

| Time after fusion

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 h | 36 h | ||||||

| Accessionno. | Symbol | Gene function | − | + | − | + | |

| Cell cycle | |||||||

| W69443 | HMG14 | high-mobility group (nonhistone chromosomal) protein 14 | <1.5 | 1.54 ± 0.06 | 1.73 ± 0.11 | <1.5 | |

| AA1475 | GAPCENA | rab6 GTPase activating protein (GAP and centrosome associated) | >0.67 | >0.67 | 0.61 ± 0.01 | >0.67 | |

| W90163 | RAMP | RA-regulated nuclear matrix-associated protein | >0.67 | >0.67 | 0.45 ± 0.14 | >0.67 | |

| R10158 | LOC51185 | protein × 0001/member of the ATP-dependent serine protease (LON) family |

1.58 ± 0.08 | <1.5 | <1.5 | <1.5 | |

| H66120 | CENPE | centromere protein E (312 kD) | 3.07 ± 0.78 | 3.55 ± 0.43 | 7.39 ± 2.39 | 7.01 ± 0.27 | |

| DNA repair | |||||||

| W37869 | EZH1 | enhancer of zeste (Drosophila melanogaster) homologue 1 | 0.55 ± 0.10 | >0.67 | >0.67 | >0.67 | |

| Tumor suppressor/apoptosis | |||||||

| R19586 | PLP15 | proteolipid protein 1 (Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease) | 1.736 ± 60.26 | <1.5 | 2.42 ± 0.15 | 3.84 ± 1.57 | |

| R80461 | PDCD5 | programmed cell death 5 | <1.5 | <1.5 | 1.82 ± 0.13 | 2.53 ± 0.8 | |

| H28623 | CREG | cellular repressor of E1A-stimulated genes | >0.67 | >0.67 | 0.51 ± 0.23 | >0.67 | |

| N28014 | BRAP | BRCA1-associated protein | 0.54 ± 0.1 | >0.67 | >0.67 | >0.67 | |

| R77391 | RECK | reversion-inducing cysteine-rich protein with kazal motifs | 0.44 ± 0.04 | >0.67 | >0.67 | >0.67 | |

| Receptor/growth factor regulator |

|||||||

| AA088248 | FGFR1 | fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 | <1.5 | <1.5 | 1.62 ± 0.03 | <1.5 | |

| W38478 | IGFBP7 | insulin-like growth factor binding protein 7 | <1.5 | <1.5 | 1.6 ± 0.07 | <1.5 | |

| AA046598 | IGFBP1 | insulin-like growth factor binding protein 1 | >0.67 | >0.67 | 0.63 ± 0.05 | >0.67 | |

| T39448 | ADRA2C | adrenergic α-2C receptor | 1.90 ± 0.31 | 1.77 ± 0.28 | 3.24 ± 0.56 | 3.95 ± 1.24 | |

| N30625 | CORT | cortistatin | >0.67 | >0.67 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | >0.67 | |

| AA151595 | IFNAR2 | interferon (α, β, and ζ) receptor 2 | 1.78 ± 0.28 | <1.5 | <1.5 | <1.5 | |

| Signaling | |||||||

| H77460 | LNK | lymphocyte adaptor protein | <1.5 | <1.5 | 2.46 ± 0.56 | <1.5 | |

| R14326 | HERC1 | hect domain and RCC1 (CHC1)-like domain (RLD) 1 | <1.5 | <1.5 | 2.78 ± 0.43 | 4.46 ± 1.82 | |

| H18190 | JAK1 | Janus kinase 1 | <1.5 | <1.5 | 1.79 ± 0.19 | 2.57 ± 0.86 | |

| AA037843 | NET-7 | transmembrane 4 superfamily member (tetraspan NET-7) | >0.67 | >0.67 | 0.52 ± 0.08 | >0.67 | |

| H56674 | CC1.3 | splicing factor, coactivator of activating protein-1, and estrogen receptors |

2.13 ± 0.3 | 2.08 ± 0.64 | 2.86 ± 0.15 | 3.23 ± 0.82 | |

| R17538 | PABPC4 | poly(A)-binding protein, cytoplasmic 4 (inducible form) | 1.88 ± 0.25 | 1.91 ± 0.19 | 2.08 ± 0.43 | 2.45 ± 0.78 | |

| R44875 | ARIP1 | atrophin-1 interacting protein 1 | 1.99 ± 0.33 | 2.34 ± 0.4 | 4.58 ± 1.19 | 4.99 ±0.56 | |

| AA044097 | ZFHX1B | zinc finger homeobox 1B/encoding Smad-interacting protein 1 | >0.67 | >0.67 | 0.48 ±0.16 | >0.67 | |

| H62028 | DYRK3 | dual-specificity tyrosine-(Y)-phosphorylation regulated kinase 3 | >0.67 | >0.67 | 0.40 ± 0.35 | >0.67 | |

| N45598 | AKAP6 | A kinase (PRKA) anchor protein 6 | >0.67 | >0.67 | 0.60 ± 0.03 | >0.67 | |

| AA135745 | CAMK2G | calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaM kinase) II γ | 0.5 ± 0.1 | >0.67 | >0.67 | >0.67 | |

| Metabolism/protein degradation |

|||||||

| H47026 | MGAT3 | mannosyl (β-1,4-)-glycoprotein β-1,4-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase | <1.5 | 2.32 ± 0.17 | 2.31 ± 0.43 | <1.5 | |

| H60458 | ACOX2 | acyl-coenzyme A oxidase 2, branched chain | <1.5 | 1.62 ± 0.03 | 1.63 ± 0.07 | <1.5 | |

| T91335 | LUC7L | LUC7 (Saccharomyces cerevisiae)-like | 1.72 ± 0.05 | <1.5 | 2.43 ± 0.31 | 2.67 ± 0.55 | |

| AA099341 | GBF1 | Golgi-specific brefeldin A resistance factor 1 | 0.54 ± 0.05 | >0.67 | >0.67 | >0.67 | |

| W17311 | SDHB | succinate dehydrogenase complex, subunit B, iron sulfur (Ip) | 1.99 ± 0.4 | 2.48 ± 0.80 | 4.41 ± 0.67 | <1.5 | |

| AA115737 | SLC2A10 | solute carrier family 2 (facilitated glucose transporter), member 10 | 0.56 ± 0.13 | >0.67 | >0.67 | >0.67 | |

| N48749 | FACL3 | fatty-acid-coenzyme A ligase, long-chain 3 | 0.61 ± 0.04 | >0.67 | >0.67 | >0.67 | |

| W95228 | CTSG | cathepsin G | <1.5 | <1.5 | 4.2 ± 1.57 | 5.06 ± 0.47 | |

| W19301 | GCSH | glycine cleavage system protein H (aminomethyl carrier) | 0.61 ± 0.04 | >0.67 | >0.67 | >0.67 | |

| W79562 | ATE1 | arginyltransferase 1 | 1.72 ± 0.33 | 2.08 ± 0.22 | 2.36 ± 0.21 | 2.79 ± 1.03 | |

| H98809 | PABPC1 | poly(A)-binding protein cytoplasmic 1 | >0.67 | >0.67 | 0.58 ± 0.04 | >0.67 | |

| R81846 | FTL | ferritin, light polypeptide | >0.67 | >0.67 | 0.60 ± 0.05 | >0.67 | |

The list contains genes of known function from syncytia obtained after 18 or 36 h of coculture, in the presence or absence of 10 μM cyclic pifithrin-α. Compared with single cells, only genes that showed an induction or inhibition of mRNA expression (by a factor of ≥1.5 or ≤0.67, respectively) were considered. Changes in mRNA expression were determined by microarrays as described in Materials and Methods.

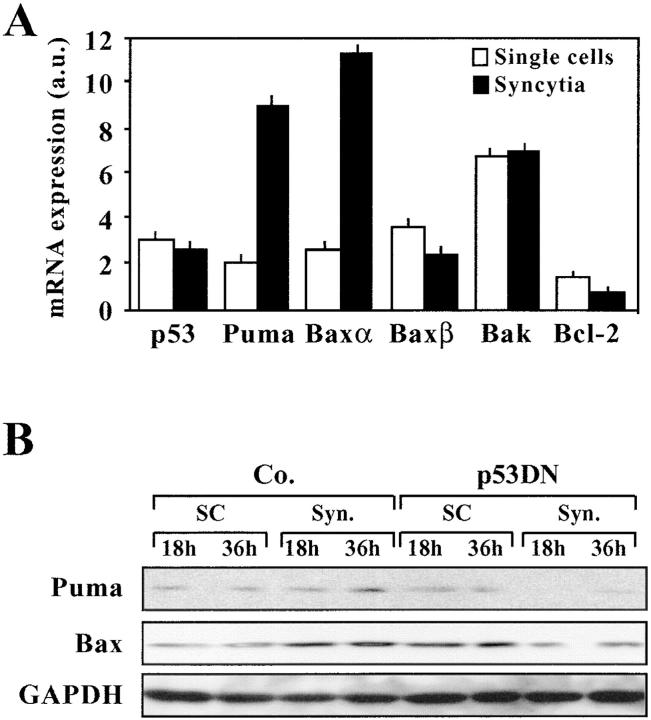

Based on the fact that the microarrays used in this study do not cover the entire transcriptome, we used a p53-specific macroarray for the identification of genes specifically associated with syncytial apoptosis. Using this technique, we found that p53 itself, c-Jun (whose gene product, together with c-Fos, forms AP1), the proapoptotic gene PIG8 (also known as ei24), the proapoptotic Bcl-2 family member Bax, as well as the proapoptotic BH3-only Bcl-2 family member Puma were up-regulated in syncytia by a factor ≥2 (Fig. 5, A and B). Quantitative RT-PCR confirmed the induction of Puma and Bax (and in particular the dominant Bax-α splice variant) transcripts (Fig. 6 A), which is consistent with the fact that syncytia overexpress Bax (7) and Puma (Fig. 6 B) at the protein level.

Figure 5.

Identification of p53 target genes by macroarray. Labeled cDNA from single cells or syncytia was hybridized to filters containing p53 target genes. The signal/background ratio was determined for all spots (A, with β-actin as an internal control) and the change in mRNA expression was determined as described in Materials and Methods (B).

Figure 6.

Up-regulation of Puma at the mRNA and protein levels. (A) Quantitative RT-PCR was used to determine the relative abundance of the indicated transcripts. (B) Protein blot detection of Puma expression. Syncytia of different ages (18 or 36 h of coculture), generated after transfection with vector only or a p53 DN construct, were subjected the immunodetection of Puma (∼21 kD), Bax, and GAPDH as a loading control.

Up-regulation of Puma Is Required for Syncytial Apoptosis.

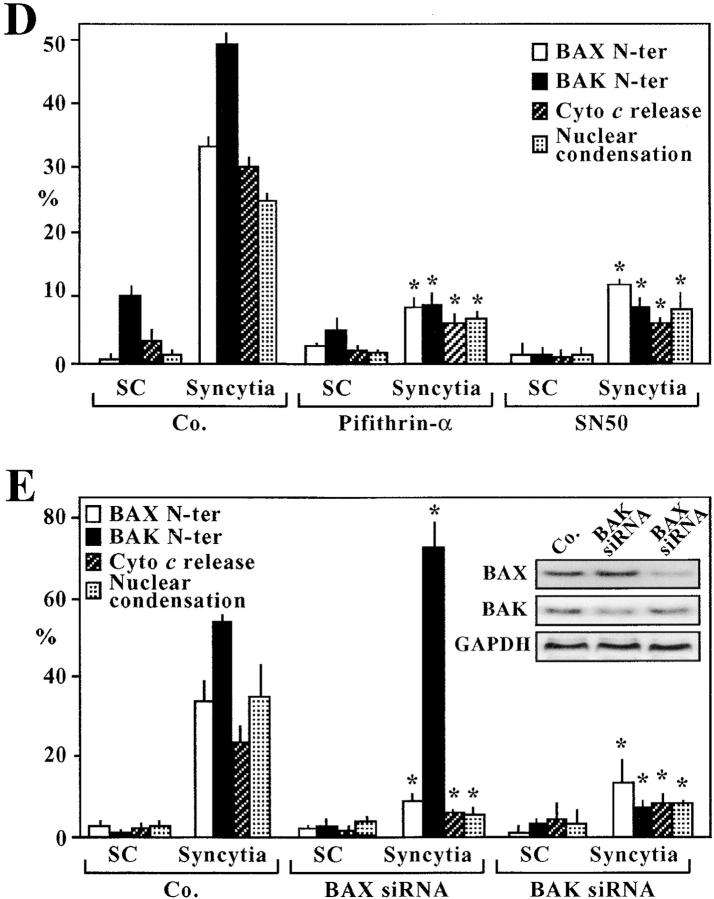

Puma has been identified recently as a p53-inducible “BH3-only” protein that can activate the proteins Bax and Bak to adopt a proapoptotic conformation (with exposure of the NH2 terminus), to insert into the outer mitochondrial membrane and to stimulate the release of cytochrome c, leading to subsequent caspase activation and apoptosis (23–25). Accordingly, transfection with antisense oligonucleotides designed to down-regulate the expression of Puma (Fig. 7 B, inset; reference 24) inhibited the exposure of the NH2-termini of Bax and Bak (as detected with conformation-specific antibodies), the release of cytochrome c from syncytial mitochondria (as detected by immunofluorescence staining), and the apoptosis-associated chromatin condensation (Fig. 7, A and B). Inhibition of NF-κB with IKSR (Fig. 7 C) or SN50, as well as inhibition of p53 with cyclic pifithrin-α (Fig. 7 D) all inhibited the activation of Bax and Bak. RNA interference of Bax or Bak, the two Puma receptors, significantly reduced syncytial apoptosis, as indicated by suppression of the nuclear chromatin condensation and the mitochondrial cytochrome c release (Fig. 7 E). As a side observation, we found that RNA interference of Bak prevented the exposure of the NH2 terminus of Bax but not vice versa, suggesting a hitherto unsuspected hierarchy among these proapoptotic proteins. Altogether, the data suggest that Puma acts on Bax and/or Bak to kill syncytia in a p53-dependent fashion.

Figure 7.

Functional impact of Puma on the Bax/Bak-mediated mitochondrial membrane permeabilization. (A) Effect of the Puma antisense oligonucleotide on the conformational change of Bax and Bak. Untreated control syncytia or syncytia generated in the presence of a Puma-specific antisense thiorate oligonucleotide were stained with antibodies specific for the NH2 terminus of Bax (red) or Bak (green) and counterstained with Hoechst 33324. Note that these antibodies only recognize the active, apoptotic conformation of Bax and Bak. (B) Quantitation of the effect of the Puma antisense oligonucleotide, as compared with a scrambled control oligonucleotide, determined 36 h after syncytium formation. The insert confirms effective down-regulation of Puma as determined by immunoblot. (C) Effect of IKSR on the activation of Bax. Cells were either transfected with vector only (pcDNA3.1) or with IKSR, 24 h before the generation of syncytia, and the indicated parameters were assessed in triplicate. (D) Effect of SN50 and cyclic pifithrin-α as compared with its control (SN50M). The indicated agents were added to HeLa Env and HeLa CD4 at the beginning of coculture, and the frequency of cells exhibiting activation of Bax or Bak, cytochrome c release and nuclear apoptosis was assessed. (E) Effect of Bax and Bak small interfering RNA (siRNA) on the apoptosis of Env-elicited syncytia. Cells were transfected with small interfering RNA oligonucleotides 24 h before fusion, and the indicated parameters were assessed. The inset demonstrates the impact of siRNA on Bax and Bak expression, as determined by immunoblot. This experiment was repeated three times with similar results.

Induction of Puma in Several Models of HIV-1 and Env-induced Apoptosis In Vitro.

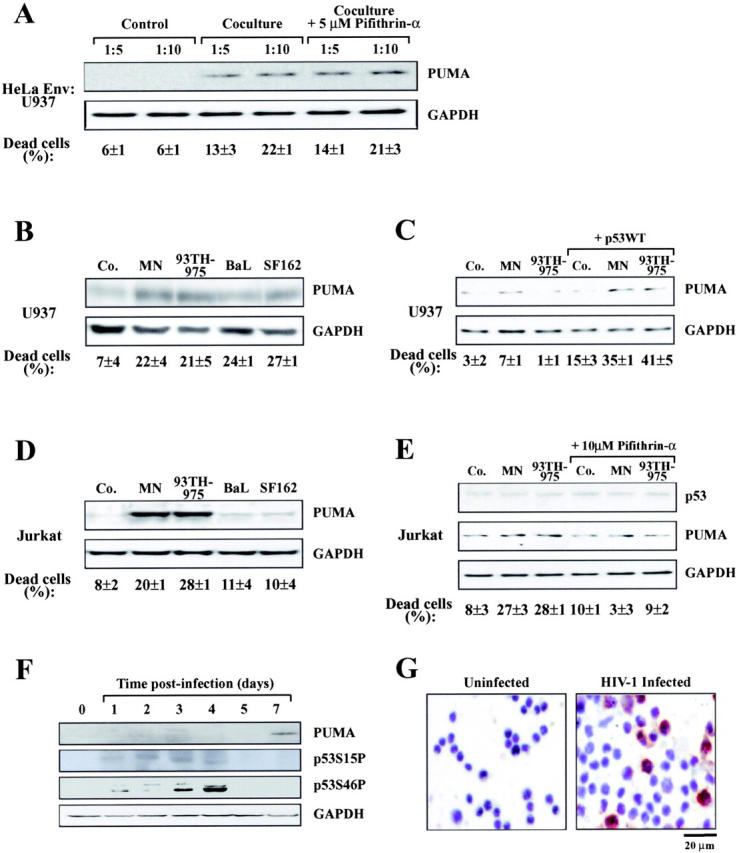

When cocultured with HeLa Env cells, U937 cells (which lack functional p53; reference 26) do not form heterokarya, but rather undergo apoptosis after a transient cell-to-cell interaction (5, 6). As shown in Fig. 8 A, apoptosis correlates with the induction of Puma, and the up-regulation of Puma is not inhibited by cyclic pifithrin-α, underscoring that Puma can be induced in a p53-independent fashion. Similarly, different recombinant gp120 variants (MN and 93TH975 with preference for CXCR4; BaL and SF162 with preference for CCR5) induced cell death and Puma protein expression in U937 cells (which express both CXCR4 and CCR5), correlating with the induction of PUMA (Fig. 8 B). Transfection of U937 cells with p53 accelerated the kinetics of gp120-induced Puma induction at early time points when gp120 alone still had no Puma-inducing effect (Fig. 8 C). Thus, p53-independent and -dependent pathways can cooperate to cause Puma induction. In p53-sufficient Jurkat cells (27), which only express CXCR4, only the R4-tropic gp120 variants induced apoptosis and Puma expression (Fig. 8 D). This effect was strongly inhibited by cyclic pifithrin-α (Fig. 8 E). Primary CD4+ lymphoblasts from healthy donors infected with HIV-1LAI/IIIb also manifested the induction of Puma, at the protein level, well after the phosphorylation of p53 (Fig. 8 F). CD4+ lymphoblasts infected with clinical HIV-1 isolates (16) manifested the induction of Puma, which could be detected in yet viable syncytia (Fig. 8 G). Thus, Env and HIV-1 infection induce Puma expression in a variety of experimental systems.

Figure 8.

Induction of Puma by Env and HIV-1 in vitro. (A) Induction of Puma in U937 cells cocultured with HeLa Env cells. U937 cells were mixed at different ratios with HeLa Env cells just before the preparation of cell lysates for immunoblot detection of Puma (Control) or coculture for 36 h in the absence or presence of the p53 inhibitor cyclic pifithrin-α (5 μM). The percentage of dead U937 cells was determined by trypan blue exclusion. (B) Induction of Puma by recombinant gp120 protein in U937 cells. U937 were exposed to the indicated gp120 protein (at 500 ng/ml) and cell death, Puma, and GAPDH expression were determined after 4 d. (C) Cooperation between gp120 and p53 to induce Puma in U937 cells. Cells were mock transfected or transfected with wild-type p53. 1 d later, the indicated gp120 proteins were added, and the expression of 53 and Puma were determined 48 h later. (D) Induction of Puma by recombinant gp120 protein in Jurkat cells as in B. (E) Effect of cyclic pifithrin-α. Jurkat cells were treated for 4 d with 500 ng/ml gp120 protein and/or 10 μM cyclic pifithrin-α, followed by determination of Puma expression. (F) Induction of Puma by infection of primary lymphoblasts in vitro. CD4+ lymphoblasts from a healthy donor were infected with HIV-1LAI/IIIb for the indicated period, and proteins (40 μg/lane) were subjected to immunoblot determination of p53 phosphorylation and Puma expression. (G) Puma induction in CD4+ lymphoblasts from a healthy donor infected with a clinical HIV-1 isolate. 5 d after infection, cells were subjected to immunohistochemical detection of Puma. Uninfected cells served as a negative control. Results typical for five independent experiments are shown.

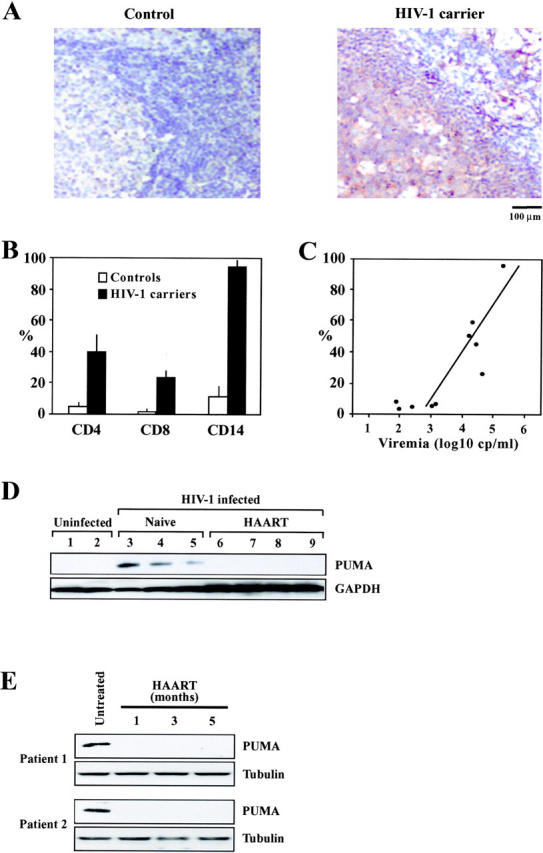

Enhanced Puma Expression in HIV-1–infected Patients.

Lymph nodes from untreated HIV-1 patients with high HIV-1 titers (>20,000 copies/ml) stained more positively for Puma than did biopsies from uninfected controls (Fig. 9 A). Using immunocytochemical methods, Puma+ cells were found among all relevant (CD4+, CD8+, and CD14+) cells from HIV-1–infected donors with such high HIV-1 titers, with a preference for CD4+ and CD14+ cells (Fig. 9 B). Puma expression levels among the PBMCs correlated positively with HIV-1 titers (Fig. 9 C). The enhanced Puma expression could also be detected by immunoblotting among circulating CD4+ cells from naive (nontreated) HIV-1 patients as compared with healthy controls or HAART-treated individuals (Fig. 9 D). Moreover, longitudinal studies revealed that Puma levels were reduced to normal levels when patients were undergoing successful antiretroviral therapy (Fig. 9 C), in line with the well-established fact that antiretroviral therapy reduces the increased spontaneous apoptosis of circulating CD4+ lymphocytes from HIV-1 carriers (28, 29). These data establish that productive HIV infection is associated with the overexpression of the apoptotic effector Puma.

Figure 9.

Induction of Puma in HIV-1–infected patients. (A) Immunocytochemical localization of Puma in lymph node biopsies of HIV-1–infected donors as compared with a healthy control. Similar results were obtained with three pairs of uninfected and HIV-1–infected donors (>105 copies/ml). (B) Frequency of PUMA+ cells among defined subsets of mononuclear cells. Patients (n = 4) and controls (n = 4) with the same clinical characteristics as in A were subjected to two-color immunofluorescence stainings, allowing for the determination of the percentage (mean ± SD) of cells expressing Puma among CD4+ or CD8+ lymphocytes, as well as among CD14+ monocytes. (C) Correlation between PUMA expression and viral titers. The frequency of PUMA+ cells was determined among total PBMCs of 10 untreated HIV-1+ patients. Each dot represents one patient. Calculations were performed following the Pearson method. (D) Expression of Puma in purified circulating CD4+ lymphocytes from uninfected control donors, naive HIV-1–infected donors, and HIV-1 carriers undergoing successful HAART. (E) Longitudinal study of individual patients. Whole PBMCs were drawn from freshly diagnosed (untreated) patients with viral titers >105 copies/ml, as well as several months after HAART. In these patients, HAART led to a reduction of retroviral titers to levels <5,000 within 4 wk. Immunoblot detection of Puma and β-tubulin (loading control) is shown.

Discussion

Our data strongly indicate that one of the dominant transcription factors activated in Env-elicited syncytia is p53. More than 80% of the genes whose expression level changed did so via a p53-dependent mechanism, as indicated by the fact that chemical p53 inhibition abolished this change. Inhibition of p53 prevented the expression of several proapoptotic genes and disabled the death program. p53 appears to be activated through at least two phosphorylation events, which are both detectable in HIV-1 carriers. One affects serine 15 and is mediated by mTOR, whereas the other affects serine 46. This latter phosphorylation event is well known to enhance the apoptogenic potential of p53 and to relay to mitochondrial apoptosis (30, 31). Although the nature of the kinase acting on serine 46 (which is not mTOR; not depicted) remains to be determined, it appears clear that this phosphorylation event occurs downstream of the Cdk1-dependent karyogamy. Genetic or pharmacological inhibition of NF-κB prevented the cyclin B-dependent Cdk1 activation, as well as the phosphorylation of p53 on both serine 15 and 46. Thus, the proapoptotic cooperation between NF-κB and p53 observed in this particular model is likely to be indirect, via a cell cycle–related effect of NF-κB. This would be consistent with the fact that NF-κB is mostly viewed as an apoptosis-inhibiting transcription factor (21). NF-κB activation would be necessary for the advancement in cell cycle, which enables p53-dependent transcription and apoptosis, yet would have no direct proapoptotic transcriptional effects. Indeed, there is no indication for the induction of antiapoptotic NF-κB target genes in our system (Tables I and Table S1). In contrast, the p53-mediated expression of Puma appears to be direct, at least in Env-induced syncytia (Fig. 1–6). It is important to note that Puma expression is not under the exclusive control of p53, at least in transgenic mice (32), and that p53-independent pathways may contribute to the Env-elicited Puma expression (Fig. 8 A–C) and actually cooperate with the p53-dependent ones (Fig. 8 C). Thus, different pathways (p53-dependent or -independent) may contribute to the induction of Puma, in vivo, in the HIV-1–infected patient. That at least part of this Puma-inducing effect involves p53 is suggested by the fact that p53 does manifest proapoptotic posttranscriptional modifications (in particular, the phosphorylation of serine 46), which are detectable in resident and circulating immune cells from HIV-1 carriers.

A cornucopia of mechanisms contribute to the enhanced apoptotic decay of T lymphocytes in HIV-1 infection. Rather than viewing the virus-mediated and host-dependent contribution to lymphodepletion in an exclusive fashion, it is conceivable that proapoptotic mechanisms actually cooperate in the patient (1–3). As shown here, both soluble and membrane-bound Env can induce the expression of the proapoptotic protein Puma, a protein that acts on mitochondria to trigger apoptosis (23–25). Recently, it has also been shown that a mutation in Vpr that reduces its apoptogenic potential (R77Q) is found in ∼80% of long-term nonprogressors; that is, patients with high HIV-1 titers yet normal CD4 counts and normal levels of spontaneous apoptosis (33, 34). Vpr directly acts on mitochondria, on a molecular complex formed by Bax, and on the adenine nucleotide translocase (33, 35), and can also elicit p53-dependent transcriptional effects (36). Although the in vitro systems characterized here were devoid of Vpr, these findings illustrate that the Env- and Vpr-elicited apoptotic pathways could cooperate in stimulating p53- and mitochondrion-mediated cell death. Such cooperative effects would be compatible with previous observations indicating a reduced expression of Bcl-2 in rarified CD4+ cells (37) and an enhanced level of Bax protein in those CD8+ cells that are undergoing apoptosis (38). Indeed, Bcl-2 is known to be down-regulated by p53 (39), whereas Bax is up-regulated (40). The p53-induced imbalance in the precarious equilibrium of pro- and antiapoptotic Bcl-2 relatives (which includes Puma and Bak, as shown in Figs. 7–9) would favor the spontaneous or activation-induced apoptosis of T lymphocytes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. L. Finnie (Ontario Cancer Institute) for microarray analysis, L. Schmitz (University of Bern), T. Soussi (Institut Curie), and K. Wiman (Karolinska Hospital) for cDNA constructs; D. Métivier (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique) for assistance, and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Research and Reagents Program for cell lines and gp120 protein, Mr. S. Showalter and Ms. M. Garcia-Moll (BioMolecular Technology) for gp120 from HIV-193TH975.

This work has been supported by a special grant from Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer, as well as grants from ANRS, FRM, the European Commission (QLG1-CT-1999-00739 and contract no. QLK3-CT-20002-01956 to G. Kroemer) and Ricerca Corrente e e Finalizzate from Ministry of Health (to M. Piacentini).

The online version of this article includes supplemental material.

Abbreviations used in this paper: Cdk1, cyclin B1–dependent kinase 1; DN, dominant-negative; Env, envelope glycoprotein complex; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GFP, green fluorescent protein; HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy; IKSR, IκB super-repressor; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; NF-κB, nuclear factor κB.

References

- 1.Pantaleo, G., and A. Fauci. 1995. Apoptosis in HIV infection. Nat. Med. 1:118–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Badley, A.D., A.A. Pilon, A. Landay, and D.H. Lynch. 2000. Mechanisms of HIV-associated lymphocyte apoptosis. Blood. 96:2951–2964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gougeon, M. 2003. Cell death and immunity: apoptosis as an HIV strategy to escape immune attack. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3:392–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alimonti, J.B., T.B. Ball, and K.R. Fowke. 2003. Mechanisms of CD4+ T lymphocyte cell death in human immunodeficiency virus infection and AIDS. J. Gen. Virol. 84:1649–1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanco, J., J. Barretina, K.F. Ferri, E. Jacotot, A. Gutierrez, C. Cabrera, G. Kroemer, B. Clotet, and J.A. Este. 2003. Cell-surface-expressed HIV-1 envelope induces the death of CD4 T cells during GP41-mediated hemifusion-like events. Virology. 305:318–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferri, K.F., E. Jacotot, J. Blanco, J.A. Esté, A. Zamzami, S.A. Susin, G. Brothers, J.C. Reed, J.M. Penninger, and G. Kroemer. 2000. Apoptosis control in syncytia induced by the HIV-1–envelope glycoprotein complex. Role of mitochondria and caspases. J. Exp. Med. 192:1081–1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castedo, M., K.F. Ferri, J. Blanco, T. Roumier, N. Larochette, J. Barretina, A. Amendola, R. Nardacci, D. Metivier, J.A. Este, et al. 2001. Human immunodeficiency virus 1 envelope glycoprotein complex–induced apoptosis involves mammalian target of rapamycin/FKBP12-rapamycin–associated protein-mediated p53 phosphorylation. J. Exp. Med. 194:1097–1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castedo, M., J.-L. Perfettini, T. Roumier, and G. Kroemer. 2002. Cyclin-dependent kinase-1: linking apoptosis to cell cycle and mitotic catastrophe. Cell Death Differ. 9:1287–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Genini, D., D. Sheeter, S. Rought, J.J. Zaunders, S.A. Susin, G. Kroemer, D.D. Richman, D.A. Carson, J. Corbeil, and L.M. Leoni. 2001. HIV induced lymphocyte apoptosis by a p53-initiated, mitochondrion-mediated mechanism. FASEB J. 15:5–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petit, F., D. Arnoult, J.D. Lelievre, L.M. Parseval, A.J. Hance, P. Schneider, J. Corbeil, J.C. Ameisen, and J. Estaquier. 2002. Productive HIV-1 infection of primary CD4+ T cells induces mitochondrial membrane permeabilization leading to caspase-independent cell death. J. Biol. Chem. 277:1477–1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castedo, M., T. Roumier, J. Blanco, K.F. Ferri, J. Barretina, K. Andreau, J.-L. Perfettini, A. Armendola, R. Nardacci, P. LeDuc, et al. 2002. Sequential involvement of Cdk1, mTOR and p53 in apoptosis induced by the human immunodeficiency virus-1 envelope. EMBO J. 21:4070–4080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piedimonte, G., D. Corsi, M. Paiardini, G. Cannavo, R. Ientile, I. Picerno, M. Montroni, G. Silvestri, and M. Magnani. 1999. Unscheduled cyclin B expression and p34 cdc2 activation in T lymphocytes from HIV-infected patients. AIDS. 13:1159–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moretti, S., S. Marcellini, S. Boschini, G. Famularo, G. Santini, E. Alesse, S.M. Steinberg, M.G. Cifone, G. Kroemer, and C. de Simone. 2000. Apoptosis and apoptosis-associated perturbations of peripheral blood lymphocytes during HIV infection: comparision between AIDS patients and asymptomatic long-term non-progressors. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 122:364–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van den Heuvel, S., and E. Harlow. 1993. Distinct roles for cyclin dependent kinases in cell cycle control. Science. 262:2050–2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daugas, E., S.A. Susin, N. Zamzami, K. Ferri, T. Irinopoulos, N. Larochette, M.C. Prevost, B. Leber, D. Andrews, J. Penninger, and G. Kroemer. 2000. Mitochondrio-nuclear redistribution of AIF in apoptosis and necrosis. FASEB J. 14:729–739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bartolini, B., A. Di Caro, R.A. Cavallaro, L. Liverani, G. Mascellani, G. La Rosa, C. Marianelli, M. Muscillo, A. Benedetto, and L. Cellai. 2003. Susceptibility to highly sulphated glycosaminoglycans of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication in peripheral blood lymphocytes and monocyte-derived macrophages cell cultures. Antiviral Res. 58:139–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferri, K.F., E. Jacotot, P. LeDuc, M. Geuskens, D.E. Ingber, and G. Kroemer. 2000. Apoptosis of syncytia induced by HIV-1-envelope glycoprotein complex. Influence of cell shape and size. Exp. Cell Sci. 261:119–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferri, K.F., E. Jacotot, M. Geuskens, and G. Kroemer. 2000. Apoptosis and karyogamy in syncytia induced by HIV-1-ENV/CD4 interaction. Cell Death Differ. 7:1137–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaltschmidt, B., C. Kaltschmidt, S.P. Hehner, W. Droge, and M.L. Schmitz. 1999. Repression of NF-kappaB impairs HeLa cell proliferation by functional interference with cell cycle checkpoint regulators. Oncogene. 18:3213–3225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hollstein, M., D. Sidransky, B. Vogelstein, and C. Harris. 1991. p53 mutations in human cancers. Science. 253:49–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smahi, A., G. Courtois, S.H. Rabia, R. Doffinger, C. Bodemer, A. Munnich, J.L. Casanova, and A. Israel. 2002. The NF-kappaB signalling pathway in human diseases: from incontinentia pigmenti to ectodermal dysplasias and immune-deficiency syndromes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 11:2371–2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karin, M., Y. Cao, F.R. Greten, and Z.W. Li. 2002. NF-kappaB in cancer: from innocent bystander to major culprit. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2:301–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu, J., L. Zhang, P.M. Hwang, J.W. Kinzler, and B. Vogelstein. 2001. PUMA induces the rapid apoptosis of colorectal cancer cells. Mol. Cell. 7:673–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakano, K., and K.H. Vousden. 2001. PUMA, a novel proapoptotic gene, is induced by p53. Mol. Cell. 7:683–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu, J., Z. Wang, K.W. Kinzler, B. Vogelstein, and L. Zhang. 2003. PUMA mediates the apoptotic response to p53 in colorectal cancer cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:1931–1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stiewe, T., and B.M. Putzer. 2000. Role of the p53-homologue p73 in E2F1-induced apoptosis. Nat. Genet. 26:464–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gualberto, A., G. Marquez, M. Carballo, G.L. Youngblood, S.W. Hunt III, A.S. Baldwin, and F. 1998. p53 transactivation of the HIV-1 long terminal repeat is blocked by PD 144795, a calcineurin-inhibitor with anti-HIV properties. J. Biol. Chem. 273:7088–7093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Autran, B., G. Carcelain, T.S. Li, C. Blanc, D. Mathez, R. Tubiana, C. Katlama, P. Debre, and J. Leibowitch. 1997. Positive effects of combined antiretroviral therapy on CD4+ T cell homeostasis and function in advanced HIV disease. Science. 277:112–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grelli, S., S. Campagna, M. Lichtner, G. Ricci, S. Vella, V. Vullo, F. Montella, S. Di Fabio, C. Favalli, A. Mastino, and B. Macchi. 2000. Spontaneous and anti-Fas-induced apoptosis in lymphocytes from HIV-infected patients undergoing highly active anti-retroviral therapy. AIDS. 14:939–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oda, K., H. Arakawa, T. Tanak, K. Matsuda, C. Tanikawa, T. Mori, H. Nishimori, K. Tamai, T. Tokino, Y. Nakamura, and Y. Taya. 2000. p53AIP1, a potential mediator of p53-dependent apoptosis, and its regulation by Ser-46-phosphorylated p53. Cell. 102:849–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vousden, K.H., and X. Lu. 2002. Live or let die: the cell's response to p53. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2:594–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Villunger, A., E.M. Michalak, L. Coultas, F. Mullauer, G. Bock, M.J. Ausserlechner, J.M. Adams, and A. Strasser. 2003. p53- and drug-induced apoptotic responses mediated by BH3-only proteins Puma and nNoxa. Science. 302:1036–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lum, J.J., O.J. Cohen, Z. Nie, J.G. Weaver, T.S. Gomez, X.J. Yao, D. Lynch, A.A. Pilon, N. Hawley, J.E. Kim, et al. 2003. Vpr R77Q is associated with long-term nonprogressive HIV infection and impaired induction of apoptosis. J. Clin. Invest. 111:1547–1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brenner, C., and G. Kroemer. 2003. The mitochondriotoxic domain of Vpr determines HIV-1 virulence. J. Clin. Invest. 111:1455–1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jacotot, E., K.F. Ferri, C. El Hamel, C. Brenner, S. Druillenec, J. Hoebeke, P. Rustin, D. Métivier, C. Lenoir, M. Geuskens, et al. 2001. Control of mitochondrial membrane permeabilization by adenine nucleotide translocator interacting with HIV-1 Vpr and Bcl-2. J. Exp. Med. 193:509–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chowdhury, I.H., X.F. Wang, N.R. Landau, M.L. Robb, V.R. Polonis, D.L. Birx, and J.H. Kim. 2003. HIV-1 Vpr activates cell cycle inhibitor p21/Waf1/Cip1: a potential mechanism of G2/M cell cycle arrest. Virology. 305:371–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.David, D., H. Keller, L. Nait-Ighil, M.P. Treilhou, M. Joussemet, B. Dupont, B. Gachot, J. Maral, and J. Theze. 2002. Involvement of Bcl-2 and IL-2R in HIV-positive patients whose CD4 cell counts fail to increase rapidly with highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 16:1093–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ledru, E., H. Lecouer, S. Garcia, T. Debord, and M.L. Gougeon. 1998. Differential susceptibility to activation-induced apoptosis among peripheral Th1 subsets: Correlation with AIDS pathogenesis and consequences for AIDS pathogenesis. J. Immunol. 160:3194–3206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miyashita, T., M. Harigai, M. Hanada, and J.C. Reed. 1994. Identification of a p53-dependent negative response element in the bcl-2 gene. Cancer Res. 54:3131–3135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miyashita, T., and J.C. Reed. 1995. Tumor suppressor p53 is a direct transcriptional activator of the human bax gene. Cell. 80:293–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]