Abstract

CD38 controls the chemotaxis of leukocytes to some, but not all, chemokines, suggesting that chemokine receptor signaling in leukocytes is more diverse than previously appreciated. To determine the basis for this signaling heterogeneity, we examined the chemokine receptors that signal in a CD38-dependent manner and identified a novel “alternative” chemokine receptor signaling pathway. Similar to the “classical” signaling pathway, the alternative chemokine receptor pathway is activated by Gαi2-containing Gi proteins. However, unlike the classical pathway, the alternative pathway is also dependent on the Gq class of G proteins. We show that Gαq-deficient neutrophils and dendritic cells (DCs) make defective calcium and chemotactic responses upon stimulation with N-formyl methionyl leucyl phenylalanine and CC chemokine ligand (CCL) 3 (neutrophils), or upon stimulation with CCL2, CCL19, CCL21, and CXC chemokine ligand (CXCL) 12 (DCs). In contrast, Gαq-deficient T cell responses to CXCL12 and CCL19 remain intact. Thus, the alternative chemokine receptor pathway controls the migration of only a subset of cells. Regardless, the novel alternative chemokine receptor signaling pathway appears to be critically important for the initiation of inflammatory responses, as Gαq is required for the migration of DCs from the skin to draining lymph nodes after fluorescein isothiocyanate sensitization and the emigration of monocytes from the bone marrow into inflamed skin after contact sensitization.

Over the last 15 yr, many of the key intracellular proteins and second messengers that control cell migration have been identified, and a consensus chemokine receptor signal transduction model has been proposed (1). One of the critical components of this chemokine receptor signaling model is the trimeric G protein complex that directly associates with chemokine receptors and transduces signals from these receptors to other key intracellular signaling molecules (2–5). The G proteins associated with chemokine receptors contains three subunits: Gαi, β, and γ. The activation of G proteins is induced by the binding of GTP to Gαi and the release of free βγ. This initiates the chemokine receptor signaling cascade, with the free βγ subunits activating downstream effectors (6, 7) like phosphoinositide 3-kinase that control cytoskeletal changes necessary for chemotaxis (8–10). In addition, the βγ subunits released from chemokine receptor–associated G proteins are capable of activating phospholipase (PLC) β2 and PLCβ3 (11, 12), the enzymes responsible for inositol trisphosphate (IP3) production and intracellular calcium release from IP3-gated stores (13). Inhibitors of Gi, such as pertussis toxin (PTx), block all of these downstream signaling events (14–16) and inhibit the in vitro and in vivo migration of effectively all leukocyte populations (for review see reference 17). Thus, G proteins are of central importance in leukocyte trafficking.

Recently, we identified the ectoenzyme CD38 as another important signaling protein in the chemokine receptor signaling pathway (18). CD38, a nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) glycohydrolase and ADP-ribosyl cyclase (19), is expressed by many leukocyte populations, including neutrophils, monocytes, DCs, and lymphocytes (20, 21). The extracellular enzymatic domain of CD38 catalyzes the formation of cyclic adenosine diphosphoribose (cADPR), ADPR, and nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide from its substrates NAD+ and NADP+ (22). All three products of the CD38 enzyme reaction function as signaling molecules either by mobilizing calcium from intracellular stores (23) or by activating calcium entry from the extracellular space (24–27). We showed that at least one of the metabolites made by CD38, cADPR, controls calcium influx in chemokine-stimulated cells, and that this CD38- and cADPR-dependent calcium response is required for neutrophil and DC migration both in vitro and in vivo (28, 29). Furthermore, loss of CD38-dependent chemokine receptor signals has important immunological consequences, as mice deficient in CD38 (Cd38−/−) are more susceptible to bacterial infections (28) and make attenuated innate and adaptive immune responses to inflammatory agents and immunogens (29, 30).

Based on these data, we concluded that CD38 is a critical regulator of cell migration. However, unlike Gαi-containing G proteins, which are required for the chemotaxis of virtually all hematopoietic cells to all chemoattractants (17), CD38 is not universally required for cell migration. Instead, we found that CD38 is required for leukocyte chemotaxis to some, but not all, chemokines (28, 31). These data suggested that the signals required to induce chemotaxis have to be more diverse than previously appreciated, and we hypothesized that assessing CD38-dependent pathways would allow us to identify new proteins involved in cell migration. In this study, we directly tested this hypothesis and discovered a novel “alternative” chemokine receptor signaling pathway that is required for cell chemotaxis. Similar to the “classical” chemokine receptor signaling pathway, the alternative chemokine receptor signaling pathway is dependent on Gαi. However, unlike the classical chemokine receptor signaling pathway, the alternative pathway is also dependent on Gαq-containing G proteins. Despite the ability of Gαq proteins to directly activate several isoforms of PLCβ (32, 33), Gαq is not required for chemokine-induced IP3-mediated intracellular calcium release. Instead, Gαq, like CD38, regulates extracellular calcium entry in chemokine-stimulated cells. Importantly, we found that Gαq-deficient (Gnaq−/−) DCs and monocytes are unable to migrate to inflammatory sites and LNs in vivo, demonstrating that this alternative Gαq-coupled chemokine receptor signaling pathway is critically important for the initiation of immune responses. The implications of these unexpected findings for chemokine receptor biology and inflammation are discussed.

RESULTS

Chemokine receptors can be divided into CD38-dependent and -independent subclasses

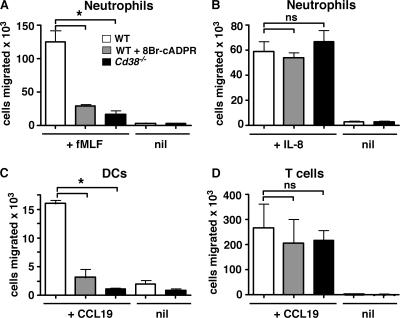

We previously showed that the in vitro chemotaxis of mouse formyl peptide receptor (mFPR) 1–expressing mouse bone marrow neutrophils to the chemoattractant N-formyl methionyl leucyl phenylalanine (fMLF) is dependent on CD38 and at least one of its enzymatically generated products, cADPR (28, 31). Indeed, neither WT neutrophils pretreated with the membrane-permeant cADPR antagonist 8Br-cADPR nor Cd38−/− neutrophils migrate in transwell chambers in response to an optimal concentration of fMLF (Fig. 1 A). In contrast, chemotaxis of Cd38−/− neutrophils and 8Br-cADPR–treated WT neutrophils to the CXC chemokine receptor (CXCR) 1/CXCR2 ligand IL-8 (Fig. 1 B) is equivalent to chemotaxis of normal WT neutrophils, indicating that there must be at least two subclasses of chemokine receptors that can be distinguished from one another based on their requirement for CD38.

Figure 1.

Differential control of leukocyte chemotaxis by the CD38/cADPR signaling pathway. (A and B) Bone marrow neutrophils from C57BL/6J (WT and WT + 8Br-cADPR) and Cd38−/− mice were preincubated for 20 min in media (white and black bars) or 100 μM 8Br-cADPR (gray bars) and placed in transwell chambers containing media (nil), or 1 μM fMLF (A) or 100 nM IL-8 (B) in the bottom chamber. The cells that migrated to the bottom chamber in response to the chemokine gradient were collected after 1 h and enumerated by FACS. (C and D) Splenic and LN CD11c+ DCs and splenic CD4+ T cells were purified from WT and Cd38−/− mice. The DCs (C) and T cells (D) were preincubated for 20 min in media or 8Br-cADPR (as described for A and B) and placed in transwell chambers containing media or CCL19 (50 ng/ml for DCs and 300 ng/ml for T cells). The number of cells that migrated to the bottom chamber after 2 h was determined by FACS. The results are expressed as the mean ± SD of triplicate cultures. The data shown are representative of four or more independent experiments. *, P ≤ 0.0007 between WT cells and the indicated groups. ns, not significant.

In subsequent analyses of mouse and human leukocytes, we found additional examples of chemokine receptors that signal in either a CD38/cADPR-dependent or -independent manner (28, 29, 31). However, when we compared the chemotactic response of peripheral (isolated from spleen and LNs) mouse DCs and T cells with the same CC chemokine receptor (CCR) 7 ligand, CCL19, we found that the peripheral Cd38−/− DCs were unable to migrate in response to the CCL19 gradient (Fig. 1 C), whereas CD4 T cells purified from the same tissues of the same Cd38−/− mice migrated normally in response to CCL19 (Fig. 1 D). Likewise, peripheral WT DCs pretreated with the cADPR antagonist 8Br-cADPR made a defective chemotactic response to CCL19 (Fig. 1 C), whereas the chemotactic response of WT T cells pretreated with 8Br-cADPR was equivalent to that observed for the untreated WT T cells (Fig. 1 D). Collectively, these data showed that chemokine receptors can be divided into different subclasses and that the subclass of the chemokine receptor is variable and dependent on the cell type expressing the chemokine receptor.

CD38-dependent chemokine receptors couple to Gαq

Our data suggested that there was considerably more diversity or heterogeneity in the molecular signals that regulate chemotaxis than previously appreciated. To better understand the diversity between chemokine receptors, we examined the response of WT and Cd38−/− neutrophils to platelet-activating factor (PAF), a ligand of the PAFR. We chose to analyze signaling through this receptor, as it is one of the few known chemoattractant receptors that can induce calcium release in a PTx-independent fashion, indicating that it must functionally couple to other G proteins in addition to those containing Gαi (34–36). Therefore, we loaded bone marrow WT and Cd38−/− neutrophils with calcium-sensing fluorescent dyes, stimulated the cells with PAF, and measured accumulation of intracellular free calcium by FACS. As previously reported for human neutrophils (34), PAF-stimulated WT bone marrow neutrophils made a bimodal calcium response with a rapid rise in intracellular free calcium levels that was followed by a second phase of sustained calcium mobilization (Fig. 2 A). The first phase of calcium release was largely caused by calcium release from intracellular stores, as it was not blocked in the presence of EGTA, whereas the second phase was caused by calcium entry, as it was inhibited when EGTA was added to the external medium (unpublished data). Interestingly, the first calcium release from intracellular stores was intact in the PAF-activated Cd38−/− neutrophils; however, minimal calcium entry was observed during the second sustained phase of the response (Fig. 2 A). Similar results were observed with 8Br-cADPR–treated WT neutrophils and with PAF-stimulated bone marrow–derived Cd38−/− DCs (unpublished data). Thus, calcium signaling through the PAFR appears to be regulated by CD38 and cADPR.

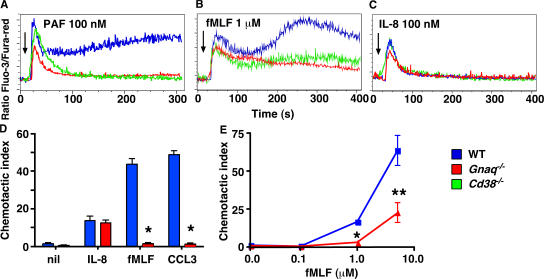

Figure 2.

Signaling through CD38-dependent chemokine receptors also requires Gαq. (A–C) Bone marrow neutrophils from WT (blue), Cd38−/− (green), and Gnaq−/− (red) mice were loaded with the calcium-detecting dyes Fluo-3 and Fura-red and stimulated with 100 nM PAF (A), 1 μM fMLF (B), or 100 nM IL-8 (C). Relative intracellular calcium levels were measured by FACS and are reported as the ratio of Fluo-3/Fura-red. Arrows indicate when the stimulus was added to the cells. (D and E) Bone marrow neutrophils from WT and Gnaq−/− mice were placed in transwells containing media (nil), fMLF (D, 1 μM; E, 0.1–5 μM), 100 nM IL-8, or 50 ng/ml CCL3. The cells that migrated to the bottom chamber in response to the chemokine gradient were collected after 1 h and enumerated by FACS. The results are expressed as the mean ± SD of the CI (see Materials and methods for description) of triplicate cultures. The data shown are representative of four or more independent experiments. *, P ≤ 0.0001; or **, P < 0.03 between WT and Gnaq−/− neutrophils.

It has been previously demonstrated that PTx-treated PAF-activated cells produce IP3 (34–36), indicating that the PAFR must couple to one or more members of the Gq family of G proteins that are capable of activating PLCβ and inducing IP3 formation (32, 33). To assess whether the PAFR couples to Gαq, we purified bone marrow neutrophils from chimeric mice that lacked Gαq (Gnaq−/−) expression in the bone marrow–derived hematopoietic cells. We then stimulated the cells with PAF and measured intracellular calcium accumulation. Similar to the previous experiments that used PTx-treated human neutrophils (34), the immediate calcium release from IP3-gated intracellular stores was reduced, although not absent, in the PAF-stimulated Gnaq−/− neutrophils relative to WT neutrophils (Fig. 2 A). Furthermore, in a manner identical to what we observed with Cd38−/− neutrophils, the PAF-induced calcium response was not sustained in the Gnaq−/− neutrophils (Fig. 2 A), suggesting that Gαq regulates both intracellular calcium release and calcium influx in these cells.

These results suggested that CD38 and Gαq might both be involved in activating calcium influx in chemokine-stimulated cells. If this conclusion is correct, then we postulated that Gαq, like CD38, might also regulate calcium influx in fMLF-stimulated neutrophils. To test this hypothesis, we measured the calcium response of fMLF-activated bone marrow neutrophils isolated from WT, Cd38−/−, and Gnaq−/− mice. As shown earlier (28, 31), we observed a bimodal calcium response in the fMLF-activated WT neutrophils and a significantly reduced calcium response in the fMLF-stimulated Cd38−/− neutrophils (Fig. 2 B). Interestingly, the calcium response of the fMLF-activated Gnaq−/− neutrophils was very similar to that of the Cd38−/− neutrophils and significantly reduced relative to the WT neutrophils (Fig. 2 B). We observed the most pronounced reduction in the calcium response of the fMLF-activated Gnaq−/− neutrophils during the second calcium influx phase of the response (28), suggesting a prominent role for Gαq in regulating calcium entry rather than intracellular calcium release in this response. To bolster this conclusion, we next examined the calcium response of IL-8–activated Gnaq−/− neutrophils, as the calcium response to IL-8 in mouse bone marrow neutrophils is almost entirely caused by IP3-induced intracellular calcium release (28). In agreement with our hypothesis, the calcium response of IL-8–stimulated neutrophils was largely unaffected by the loss of Gαq (Fig. 2 C), again very similar to what we observed with the Cd38−/− neutrophils (Fig. 2 C).

Collectively, these data suggested a strong positive correlation between CD38 and Gαq, at least with respect to calcium influx in response to chemokine receptor ligation. Given the requirement for both CD38 and calcium influx in neutrophil chemotactic responses to chemoattractants such as fMLF (28), we postulated that Gαq was also likely to be required for chemotaxis to chemokines that signal in a CD38-dependent fashion. To test this possibility, we examined the in vitro chemotaxis of Gnaq−/− bone marrow neutrophils to chemokines that signal in a CD38- and calcium influx–independent (IL-8) or a CD38- and calcium influx–dependent (fMLF and CCL3) fashion (28). As shown in Fig. 2 D, in vitro chemotaxis of the Gnaq−/− neutrophils to IL-8 was completely normal. However the Gnaq−/− cells were unable to migrate in response to either fMLF or CCL3 (Fig. 2 D). This impaired chemotactic response was not caused by an altered responsiveness to the chemoattractants, as the Gnaq−/− neutrophils made a defective chemotactic response at all doses of fMLF (see Fig. 3 E) or CCL3 (not depicted) tested. Instead, the data demonstrate the existence of a novel Gαq- and CD38-dependent chemokine receptor signaling pathway that is engaged by some, but not all, chemokine receptors.

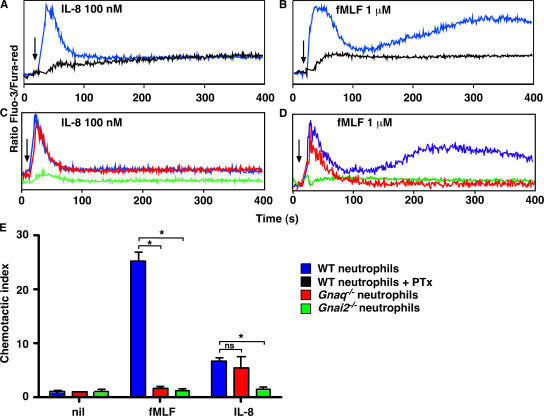

Figure 3.

Signaling through a subset of chemokine receptors is dependent on Gαi2 and Gαq. (A–D) Bone marrow neutrophils from WT (blue or black), Gnaq−/− (red), or Gnai2−/− (green) mice were preincubated in media or 500 ng/ml PTx (black) for 4 h. The cells were loaded with Fluo-3 and Fura-red and stimulated with 100 nM IL-8 (A and C) or 1 μM fMLF (B and D). Relative intracellular calcium levels were measured by FACS and are reported as the ratio of Fluo-3/Fura-red. Arrows indicate when the stimulus was added to the cells. (E) Bone marrow neutrophils from WT, Gnaq−/−, or Gnai2−/− mice were placed in transwells containing media (nil), 1 μM fMLF, or 100 nM IL-8. The cells that migrated to the bottom chamber in response to the chemokine gradient were collected after 1 h and enumerated by FACS. The results are expressed as the mean ± SD of the CI of triplicate cultures. The data shown are representative of four or more independent experiments. *, P ≤ 0.0001 between WT neutrophils and the indicated groups. ns, not significant.

Signaling through a subset of chemokine receptors requires both Gαi and Gαq

The results showing that chemotaxis of neutrophils to mFPR1 and CCR1 ligands is Gαq dependent were surprising, as the Gi inhibitor PTx is known to block chemotaxis of essentially all leukocytes (17). Because we could not find any reports testing the effect of PTx on mouse bone marrow–derived neutrophils, we thought it important to test this assumption experimentally. Therefore, we treated WT neutrophils with PTx and then measured the calcium response to IL-8 and fMLF. Similar to published data (37), the calcium responses were largely, although not entirely, ablated in the PTx-treated bone marrow neutrophils stimulated with either IL-8 (Fig. 3 A) or fMLF (Fig. 3 B). To confirm the PTx results, we also measured intracellular calcium levels and chemotaxis in WT, Gαi2-deficient (Gnai2−/−), and Gnaq−/− neutrophils that were activated with either IL-8 or fMLF. Similar to the PTx-treated cells, Gnai2−/− neutrophils made a very reduced calcium response after exposure to either IL-8 or fMLF (Fig. 3, C and D). However, the calcium response of the Gnaq−/− neutrophils to IL-8 was normal (Fig. 3 C), and the calcium response of the Gnaq−/− cells to fMLF was only partially impaired (Fig. 3 D). Not surprisingly, Gnai2−/− neutrophils were unresponsive to both IL-8 and fMLF in the in vitro chemotaxis assay (Fig. 3 E). In contrast, the chemotactic response of Gnaq−/− neutrophils to fMLF was ablated, whereas the response to IL-8 was completely intact (Fig. 3 E). Collectively, the data indicate that some chemokine receptors expressed by mouse bone marrow neutrophils, such as CXCR1/2, couple to G proteins containing Gαi2 but not Gαq. However other receptors, such as mFPR1 and CCR1, couple to two different classes of G proteins, Gαi2 and Gαq.

Gαq regulates calcium influx in chemokine-stimulated neutrophils

The “signature” activity of the Gq class of G proteins is to activate one or more PLCβ isoforms, which catalyze production of IP3 and promote intracellular calcium release (32, 33). This activity is performed by the α subunit of the trimeric Gαq-containing proteins (32, 33). Therefore, it was surprising to find that the largest alteration in the calcium response of the fMLF-stimulated Gnaq−/− neutrophils appeared during the later calcium entry phase of the response rather than during the initiation of the calcium response. To better understand how Gαq regulates chemokine receptor signal transduction, we examined the calcium response of chemokine-stimulated Gnaq−/− mouse bone marrow neutrophils in more detail. Initially, we stimulated Gnaq−/− neutrophils with fMLF in the presence or absence of EGTA (to chelate the extracellular calcium) so that we could assess the relative contribution of Gαq to intracellular calcium release and extracellular calcium influx. Identical to our earlier results, the calcium response of fMLF-stimulated Gnaq−/− neutrophils initiated apparently normally but was not sustained and rapidly dropped to background levels (Fig. 4 A). Indeed, as shown in Fig. 4 B, the calcium response of the EGTA-treated fMLF-activated Gnaq−/− neutrophils was very similar to that seen in equivalently treated WT neutrophils, indicating that Gαq is not obligatorily required for intracellular calcium release, at least in this cell type. Because intracellular calcium release in chemokine receptor–stimulated leukocytes is IP3 dependent, we asked whether we could block the remaining calcium response in Gnaq−/− neutrophils by treating the fMLF-activated Gnaq−/− cells with the IP3 inhibitor 2-aminoethoxydiphenylborate (2-APB). As shown in Fig. 4 C, the calcium response was ablated in the 2-APB–treated Gnaq−/− neutrophils, similar to that observed with fMLF-activated Gnai2−/− neutrophils (Fig. 3).

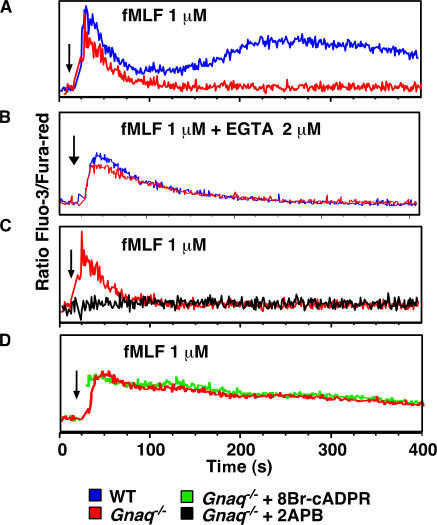

Figure 4.

Gαq and cADPR coregulate calcium influx in fMLF-stimulated neutrophils. (A–D) Bone marrow neutrophils from WT (blue) or Gnaq−/− (red, green, and black) mice were preincubated in media (Gnaq−/−, red; WT, blue), 100 μM 8Br-cADPR (green), or 100 μM 2-APB (black) for 20 min. The cells were loaded with Fluo-3 and Fura-red and stimulated with 1 μM fMLF. Relative intracellular calcium levels were measured by FACS and are reported as the ratio of Fluo-3/Fura-red. In B, the extracellular calcium was chelated with 2 mM EGTA immediately before stimulation. Arrows indicate when the stimulus was added to the cells. The data shown are representative of at least three independent experiments.

The calcium responses of the Gnaq−/− neutrophils were very similar to our previous findings using Cd38−/− neutrophils (28, 31), suggesting to us that Gαq and CD38 likely coregulate the same calcium entry pathway in the fMLF-activated neutrophils. To test this possibility, we stimulated Gnaq−/− neutrophils with fMLF in the presence or absence of the cADPR antagonist 8Br-cADPR and measured the calcium response. As predicted, the calcium signaling profiles were identical between the untreated and 8Br-cADPR–treated Gnaq−/− cells (Fig. 4 D). Collectively, the data indicate that Gαi2 controls the IP3-gated calcium release, and that Gαq and CD38 coordinately sustain the calcium response by activating calcium entry in fMLF-activated mouse bone marrow neutrophils. The data further suggest that the Gαi2-dependent calcium release is necessary for the initiation of the sustained calcium response in the fMLF-activated bone marrow neutrophils. However, it is also possible that Gαi2 additionally regulates the CD38- and Gαq-dependent calcium influx response by other mechanisms unrelated to intracellular calcium release.

Gαq differentially regulates chemokine receptor signaling in DCs and T lymphocytes

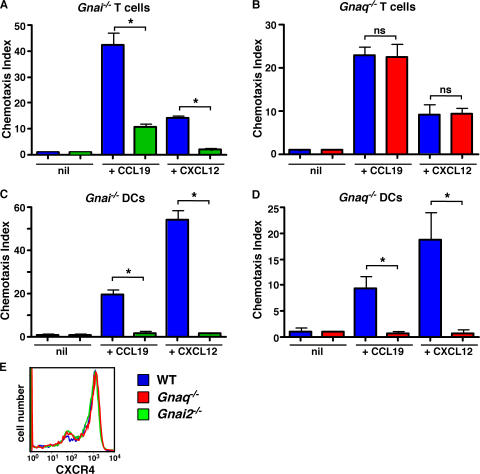

Because Gαq and CD38 are both required for productive mFPR1 and CCR1 signaling in mouse neutrophils, we postulated that Gαq would also be required for chemotaxis of DCs to CXCR4 and CCR7 ligands, as signaling through these receptors is CD38 and cADPR dependent (Fig. 1). Furthermore, we predicted that signaling through CXCR4 and CCR7 in T cells would not be Gαq dependent, as CD38 is not required for the chemotaxis of these cells to the CXCR4 and CCR7 ligands CXCL12 and CCL19 (Fig. 1). Instead, we predicted that T cell chemotaxis to these ligands would require Gαi2. To test these predictions, we measured the in vitro chemotaxis of DCs and T cells from WT, Gnaq−/−, and Gnai2−/− mice to CCL19 and CXCL12. As expected based on previously published experiments using the Gi inhibitor PTx (38–40), the chemotaxis of T cells and DCs to both chemokines requires Gαi2 (Fig. 5, A and C). However, chemotaxis of Gnaq−/− T cells to the same two chemokines was completely normal (Fig. 5 B), indicating that CCR7 and CXCR4 signaling is Gαi2, but not Gαq, dependent in T cells. In striking contrast, the chemotaxis of Gnaq−/− DCs to CXCL12 and CCL19 was ablated (Fig. 5 D). The impaired chemotaxis of the Gnaq−/− DCs was not caused by defective chemokine receptor expression, at least for CXCR4, as this receptor was expressed at equivalent levels in the WT, Gnai2−/−, and Gnaq−/− DCs (Fig. 5 E). Thus, Gαq, like CD38, regulates CCR7 and CXCR4 signaling in DCs but not in T cells. Collectively, these data indicate that the same chemokine receptor can couple to the Gαq/CD38-dependent signaling pathway in one cell type but not necessarily in all cell types.

Figure 5.

DC migration to CCR7 and CXCR4 ligands is regulated by both Gαq and Gαi2, but only Gαi2 is necessary for the migration of T cells to the same ligands. (A and B) Spleen cells were isolated from WT (blue), Gnai2−/− (green), and Gnaq−/− (red) mice and placed in transwell chambers containing media (nil), 300 ng/ml CCL19, or 300 ng/ml CXCL12. The number of CD4+ T cells placed in the top chamber and the number of CD4+ T cells that migrated to the bottom chamber after 2 h were determined by FACS. The percentage of CD4+ T cells that migrated in response to the chemokine gradient was calculated, and the CI was determined. The data are shown as the mean ± SD of the CI of triplicate cultures. (C–E) CD11c+ cells were purified from collagenase-digested spleens and LNs of WT, Gnai2−/−, and Gnaq−/− mice and placed in transwell chambers containing media (nil), 50 ng/ml CCL19, or 100 ng/ml CXCL12. After 2 h, the cells that migrated to the bottom chamber in response to the chemokine gradient were collected and enumerated by FACS. The results are expressed as the mean ± SD of the CI of triplicate cultures. (E) CXCR4 expression levels on purified CD11c+ cells were determined by FACS. *, P ≤ 0.004 between WT cells and the indicated groups. The data shown are representative of at least three independent experiments. ns, not significant.

Inflammation-induced migration of DCs and monocytes requires Gαq

Previous results showed that Gαq regulates the in vitro chemotaxis of DCs but not B cells (not depicted) and T cells (Fig. 5). Based on these data, we predicted that Gαq would also be required for the in vivo migration of DCs to secondary lymphoid organs. To test this hypothesis, we first examined the composition and cellularity of the skin, LNs, and spleens of Gnaq−/− chimeras. As shown in Table I, the total cellularity of the various LNs (axillary and mesenteric), spleen, and skin epidermis was similar between WT and Gnaq−/− mice. Likewise, the numbers of T cells present in these tissues were indistinguishable between WT and Gnaq−/− bone marrow chimeras (Table I). Finally, we did not observe any reductions in the numbers of DCs present in the LNs and spleens of the Gnaq−/− mice (Table I). Indeed, if anything, some DC populations were elevated in the spleen and mesenteric LNs of the Gnaq−/− mice. Therefore, these data indicate that Gαq is not required for the migration of DCs or T cells to secondary lymphoid organs under homeostatic conditions.

Table I.

Lymphoid and DC subsets in Gnaq−/− tissues

| Populationsa | Spleen

|

Axillary LN

|

Mesenteric LN

|

Epidermis

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | Gnaq−/− | WT | Gnaq−/− | WT | Gnaq−/− | WT | Gnaq−/− | |

| Total cells (×106) | 102.2 ± 2.81 | 158.6 ± 9.8* | 7.5 ± 0.5 | 6.5 ± 0.5 | 13.3 ± 0.5 | 18 ± 0.7* | ND | ND |

| B cells (×105) (CD19+) |

594.2 ± 67.4 | 788.6 ± 50.5* | 22.8 ± 4.7 | 20.8 ± 3 | 65.6 ± 3.9 | 89.2 ± 12.7 | ND | ND |

| T cells (×105) (CD3+) |

243.4 ± 53.8 | 258.9 ± 21.1 | 18.3 ± 1.6 | 17.9 ± 2.3 | 35.4 ± 1.2 | 33.6 ± 7.6 | ND | ND |

| CD4+ T (×105) (CD3+CD4+) |

200.4 ± 36.6 | 226.6 ± 17.7 | 15.9 ± 1.4 | 14.9 ± 2 | 30.6 ± 1.2 | 28.9 ± 6 | ND | ND |

| CD8+ T (×105) (CD3+CD8+) |

37.9 ± 16.1 | 27.8 ± 3.7 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 4.4 ± 1.5 | ND | ND |

| DCs (×104) (CD11c+) |

525.9 ± 37.9 | 923.1 ± 95.7* | 23.1 ± 4.7 | 24.3 ± 4 | 87.6 ± 3.7 | 146.1 ± 26.2* | ND | ND |

| Myeloid DCs (×104) (CD11c+CD11b+CD8α−) |

159.4 ± 13.8 | 230.1 ± 35.8 | 16.5 ± 4 | 16.5 ± 3.5 | 20.1 ± 1 | 39.2 ± 4.7* | ND | ND |

| Lymphoid DCs (×104) (CD11c+CD11b−CD8α+) |

41.7 ± 3.7 | 81.3 ± 15.1* | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 1 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 3.7± 1 | ND | ND |

| Plasmacytoid DCs (×104) (CD11cintGR1+ B220int) |

28.8 ± 7.7 | 27.7 ± 3.6 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 3.9 ± 1.1 | ND | ND |

| LCs (×103) (CD11c+ClassII+Langerin+) |

ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 13.7 ± 2.9 | 13 ± 1.8 |

Cells were isolated from various WT and Gnaq−/− lymphoid tissues (n = 5 mice per group), counted, and stained with the antibodies indicated, and the total number of each leukocyte population was determined. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM of each group. *, P < 0.05 as determined by an unpaired Student's t test analysis. ND, not done.

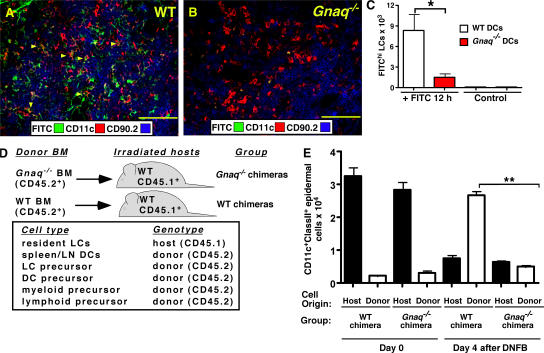

Next, to test whether Gαq regulates DC migration to LNs in response to inflammatory stimuli, we sensitized the skin of WT and Gnaq−/− mice with FITC in acetone/dibutyl phthalate and prepared frozen tissue sections of the draining LNs 18 h after sensitization. The sections were stained with CD11c and CD90.2 to identify DCs within the T cell zone of the LNs. As shown in Fig. 6 A, the FITC-bearing DCs were easily detected in the T zone of WT LNs but were largely absent from the T cell area of Gnaq−/− LNs (Fig. 6 B). To determine whether this was caused by the inappropriate localization of the Gnaq−/− DCs to other regions within the LN, we used FACS analysis to enumerate the total number of FITChiCD11c+ClassII+ DCs present in the draining LNs of the FITC-sensitized WT and Gnaq−/− mice. The number of FITC-labeled DCs present in the Gnaq−/− LN was reduced by >90% (Fig. 6 C), indicating that the DCs present in the skin of Gnaq−/− mice did not accumulate in secondary lymphoid tissues in response to inflammatory challenge. This was not caused by a deficit of DCs in the epidermis of Gnaq−/− mice, as the cells were present in equal numbers in the epidermis before stimulation (Table I). Nor did it appear that the Gnaq−/− DCs were unable to mature in response to inflammatory stimuli, as bone marrow–derived Gnaq−/− DCs matured equivalently to WT DCs in vitro in response to TNF-α (unpublished data). Thus, the data strongly suggest that Gnaq−/− DCs are unable to migrate to LNs in response to inflammatory challenge.

Figure 6.

The in vivo migration of DCs and monocytes is dependent on Gαq. (A and B) The abdominal skin of WT (A) or Gnaq−/− (B) mice was shaved and painted with FITC. The draining inguinal LNs were removed 18 h after sensitization, and frozen sections were prepared for immunohistology. The sections were stained with anti-CD11c and anti-CD90.2 to identify DCs and T cells, respectively. FITC+ cells and cells that were FITC+ and expressed CD11c (orange cells, indicated with yellow arrowheads) were found primarily within the T cell zone of the LN. Bar, 100 μm. (C) The inguinal LNs were isolated 20 h after sensitization with FITC, collagenase digested, counted, stained with antibodies to CD11c and MHCII I-Ab, and analyzed by FACS. The number of FITChiCD11c+ClassII+ DCs is indicated. n = 3 mice per group. *, P ≤ 0.008 between WT and Gnaq−/− mice. The data are representative of three independent experiments with at least three mice per group. (D) Lethally irradiated CD45.1+ C57BL/6J hosts were reconstituted with either CD45.2+ WT bone marrow (WT chimeras) or CD45.2+ Gnaq−/− bone marrow (Gnaq−/− chimeras). Resident LCs are radiation resistant and remain of host origin (reference 41). All other hematopoietic cells, including DCs and monocytes, are replaced by the donor bone marrow (reference 41). (E) 8 wk after reconstitution, the epidermal surface of the ears of the chimeric mice were either sensitized with DNFB (day 4 after DNFB) or left untouched (day 0). The number and origin (either host derived [CD45.1] or donor derived [CD45.2]) of the CD11c+ClassII+ cells in the epidermal sheet isolated from the ears of the chimeric mice were determined by cell counting and FACs analysis. The mean ± SD is shown (n = 3 mice per group per time point). **, P < 0.0001 between the number of donor-derived WT CD11c+ClassII+ cells and donor-derived Gnaq−/− CD11c+ClassII+ cells in the inflamed skin. There was no statistical difference in the number of host-derived WT resident LCs in the epidermis of either group at either time point. The data are representative of two independent experiments.

We previously demonstrated that CD38 and cADPR regulate the trafficking of CCR2-expressing monocytes both in vitro and in vivo (29). Given that CD38 is expressed on monocytes (not depicted) and that CD38 and Gαq each regulate the migration of mature DCs to draining LNs in response to inflammatory stimuli (Fig. 6 A) (29), we hypothesized that Gαq would also be required for the migration of CCR2+ monocytes to the inflamed skin. To test this hypothesis, we took advantage of a previously described model to monitor the migration of monocytes to inflamed skin (41). In brief, we lethally irradiated WT CD45.1+ B6 mice and reconstituted the mice with congenic CD45.2+ WT (WT chimeras) or CD45.2+ Gnaq−/− bone marrow (Gnaq−/− chimeras; Fig. 6 D). 8 wk after reconstitution, we isolated cells from skin epidermal sheets (isolated from the ear) of the WT and Gnaq−/− chimeras and stained the cells with antibodies to CD45.1, CD45.2, CD11c, and MHCII I-Ab. As previously reported for this model (41), the resident Langerhans cells (LCs; CD11c+ClassII+) in the skin were radiation resistant. Thus, the vast majority of LCs in the skin of both groups of chimeras were of host origin and expressed the CD45.1 allele (Fig. 6 E, day 0). In contrast, the hematopoietic cells isolated from all other sites (i.e., bone marrow, blood, and secondary lymphoid tissues) expressed the CD45.2 allele (unpublished data), indicating that these populations were radiation sensitive and had been replaced by cells derived from the donor (either WT or Gnaq−/−) bone marrow.

Next, we treated the epidermis of the chimeric animals with the inflammatory agent dinitrofluorobenzene (DNFB), as we previously showed that this contact stimulant activates LCs to migrate to LNs and induces the subsequent influx of bone marrow– or blood-derived monocytes to the inflamed epidermis, where the cells up-regulate MHCII and CD11c (29). 4 d after DNFB exposure, we isolated cells from the inflamed epidermis and again stained the cells with antibodies to CD45.1, CD45.2, CD11c, and MHCII I-Ab. As expected (29), DNFB exposure promoted the egress of the host-derived resident WT CD45.1+ LCs from the skin, resulting in a large decrease in this population in the epidermis of both WT and Gnaq−/− chimeras (Fig. 6 E, day 4). In the WT chimeras, the epidermis was largely repopulated with CD11c+ClassII+ cells that expressed the CD45.2 allele (Fig. 6 E, day 4), indicating that WT donor–derived monocytes were recruited to the inflamed skin. In striking contrast, the epidermis of the Gnaq−/− chimeras was very deficient in CD11c+ClassII+ cells, and only a small number of CD45.2-expressing (Gnaq−/−) CD11c+ClassII+ cells were detected (Fig. 6 E, day 4). These data therefore indicate that Gnaq−/− monocytes were not efficiently recruited to the inflamed epidermis, despite the fact that the inflamed skin and initial resident LCs were of WT origin. Collectively, these data show that the alternative Gαq-dependent chemokine receptor signaling pathway is critical for the in vivo trafficking of DCs and monocytes in response to inflammatory signals and indicates that this signaling pathway regulates innate immune responses and the cellular processes associated with inflammation.

DISCUSSION

Immune responses are coordinated by the migration of leukocytes between the blood, secondary lymphoid organs, and inflamed tissues (42). This well-orchestrated migration of hematopoietic cells is complex, but it is clear that chemokine receptors and the signaling molecules that reside downstream of these receptors are exceedingly important (43). Indeed, in vitro experiments using chemokine receptor–transfected cell lines revealed that chemokine receptors couple to Gi-containing G proteins and that activation of Gi, with the subsequent release of free βγ subunits, is required for chemotaxis (6). Likewise, experiments using the Gi inhibitor PTx (for review see reference 17) and our own experiments using Gαi2-deficient cells (Table II) demonstrate that Gαi-containing G proteins are crucial for the migration of primary hematopoietic cells to most of the known chemoattractants. Thus, the generally accepted classical chemokine receptor signaling model (1) correctly postulates a central role for Gαi2 in leukocyte chemotaxis.

Table II.

Signaling requirements for chemotaxis

| Receptor | Cell type (mouse) |

Gαi2

dependent |

Gαq

dependent |

CD38 dependent |

Classical or alternative pathway |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCR1 | BM neutrophil |

Y | Y | Y | Alternative |

| CCR2 | Immature DC |

Y | ? | Y | Alternative? |

| CCR7 | DC | Y | Y | Y | Alternative |

| CCR7 | T cell | Y | N | N | Classical |

| CXCR1/2 | BM neutrophil |

Y | N | N | Classical |

| CXCR4 | DC | Y | Y | Y | Alternative |

| CXCR4 | T cell | Y | N | N | Classical |

| CXCR4 | B cell | Y | N | N | Classical |

| CXCR5 | B cell | Y | N | N | Classical |

| mFPR1 | BM neutrophil |

Y | Y | Y | Alternative |

| mFPR1 | Inflam. neutrophil |

Y | N | N | Classical |

| mFPR2 | BM neutrophil |

Y | Y | Y | Alternative |

Inflam., inflammatory; N, no; Y, yes.

Despite the critical importance of Gi in chemokine-induced cell trafficking, it has been known for many years that chemokine receptors can also couple to other G proteins (for review see reference 44), including Gq family members (35, 45-47). Emerging data have revealed that these additional classes of G proteins regulate chemokine receptor–mediated functions such as IP3 generation and calcium release (35, 47-49), activation of NF-κB (50, 51), activation of tyrosine kinases (52, 53), receptor internalization (54, 55), and exocytosis (36). However, there was only sporadic evidence (56–59) to suggest that these other G proteins might also regulate the chemotactic response of the chemoattractant-stimulated leukocytes. Thus, the experiments presented in this paper are novel in that they reveal that Gαi2, although necessary, is not sufficient to induce chemotaxis of primary leukocytes to a large array of chemoattractants. Instead, an additional, alternative Gαq-coupled pathway must be engaged before primary neutrophils and DCs can migrate (Table II), and this second, alternative Gαq-dependent pathway is critically important for cell trafficking in vitro and, more importantly, in vivo, at least in response to inflammatory stimuli.

Although our data clearly document the existence of a second, alternative Gαq-dependent chemokine receptor signaling pathway, the pathway appears to have been largely overlooked in previous chemokine receptor signaling studies. This was initially surprising to us, particularly given that Gαq is widely expressed in myeloid cells and DCs (60, 61) and that there is strong evidence that other Gq family members, such as Gα15/16, can mediate chemokine-induced IP3 induction (45, 49, 62). However, there are several reasons that can explain the apparent discrepancy between the older studies and the current study. First, given the critical importance of Gi in both the classical and alternative chemokine receptor signaling pathways, it is not possible to visualize the alternative signaling pathway unless Gαq is selectively targeted in a Gαi2-sufficient cell and, to our knowledge, only a single study examining Gαq-deficient leukocytes has been published (63). Second, many of the previous biochemical studies analyzed signaling through CXCR1/CXCR2, the receptors for IL-8 and Mip2 (5–7, 48). As we now know, these receptors are activated via the classical pathway, at least in bone marrow neutrophils. Third, although the alternative signaling pathway regulates chemotaxis, it does not modulate all chemokine receptor–induced activities (i.e., chemokinesis) (28), and studies that examined an inappropriate functional readout would not be expected to identify the alternative pathway. Finally, the choice of cell type examined is critical. For example, many previous biochemical studies used transfected cell lines (i.e., HEK293 and COS-7 cells) that do not express CD38 (unpublished data), which is an important component of the alternative signaling pathway (Table II) (28–30). In addition, in primary T cells and B cells, chemokine receptors such as CXCR4 and CCR7 signal via the classical pathway, but in DCs these same receptors signal via the alternative pathway (Table II). Thus, the alternative signaling pathway is difficult to visualize unless the correct primary cells are used, and these cells then need to be interrogated with the appropriate chemokines and functional analyses.

In addition to demonstrating that Gαq is required for leukocyte chemotaxis to a subset of different chemokines, we also found that Gαq plays a previously unappreciated role in regulating calcium mobilization after chemokine receptor ligation. It is well known that four of the PLCβ isoforms can be directly activated by active GTP-bound Gαq, and that activation of these PLCβ isoforms by Gαq leads to IP3 generation and diacylglycerol production (64). However, it appears that the IP3 response in fMLF- or IL-8–stimulated primary mouse bone marrow neutrophils is mediated largely, if not exclusively, by Gαi2-containing G proteins, presumably through free βγ-mediated activation of one or more PLCβ isoforms. In fact, Gαq is not obligatorily required for the chemokine-induced early IP3-dependent calcium response of neutrophils activated with either IL-8 (a ligand of the classical pathway) or fMLF (a ligand of the alternative pathway). Instead, Gαq appears to play a critical role in activating calcium influx through a plasma membrane channel. Although we do not yet know the identity of the Gαq-activated calcium/cation channel, it has been previously reported that calcium influx in fMLF-activated human neutrophils is linked, at least in part, to nonselective cation channels (46). We also know that calcium influx in response to chemokine receptor ligation is activated by CD38 and the calcium-mobilizing metabolites generated by CD38 (Table II). Finally, our data show that the calcium response to fMLF is indistinguishable in neutrophils that are deficient in Gαq alone or that lack both Gαq and cADPR, suggesting that Gαq and CD38 are coregulators of the same cation/calcium channel.

We previously showed that extracellular calcium influx is required for the chemotaxis of mouse bone marrow neutrophils to fMLF (28) and is also necessary for the chemotaxis of DCs to CCL19, CCL21, and CXCL12 (29). Although we cannot exclude the possibility that Gαq regulates neutrophil chemotaxis by calcium-independent mechanisms, our data strongly suggest that a major mechanism by which Gαq regulates chemotaxis is by controlling the sustained calcium entry response. Our data also show that Gαq-mediated calcium influx in response to fMLF stimulation is dependent on an initial intracellular calcium release controlled by Gαi2. These results suggest that IP3, generated by Gi-activated PLCβ, sparks the global calcium response and, therefore, must be needed for calcium-dependent chemotaxis. However, published experiments showed that even when IP3 induction was completely abrogated in chemokine-stimulated neutrophils from PLCβ2 and PLCβ3 double-deficient mice, the chemotactic response of these PLCβ-deficient cells remained intact (10). Thus, these published experiments suggest that neither IP3-mediated intracellular calcium release nor calcium-dependent calcium influx are needed for neutrophil chemotaxis. Interestingly, the previously published experiments used “primed” PLCβ-deficient neutrophils isolated from inflammatory sites (10), and we used bone marrow “naive” neutrophils in all of our experiments. As shown in Table II, neutrophils isolated from inflammatory sites respond to fMLF via the classical pathway and do not require CD38 or calcium influx for chemotaxis, whereas neutrophils isolated from the bone marrow of unmanipulated normal mice respond to fMLF via the alternative pathway. Again, it appears that context is critical when examining chemotaxis, and that the requirements for calcium mobilization (from either intracellular or extracellular stores) will vary depending on many factors, including cell type, the activation state of the cell, and which chemokine receptors are examined.

Although the discovery of the Gαq-dependent alternative chemokine receptor signaling pathway begins to delineate some of the complexity of chemokine receptor signal transduction, it also leaves a whole range of new questions that will need to be addressed. For example, it is unclear why calcium mobilization is required for the chemotaxis of cells activated by the alternative chemokine receptor signaling pathway but is not required for cells activated via the classical pathway. We hypothesize that this is likely an issue of signaling thresholds and that in certain cells, synergy between the Gi- and Gq-coupled pathways is needed to optimally activate key downstream players involved in cytoskeletal rearrangements. Indeed, there is emerging data demonstrating that simultaneous activation of the Gi and Gq pathways can lead to enhanced calcium responses (65), but to date the physiologic relevance of this finding has not been appreciated. We believe that chemotaxis represents one out of perhaps multiple examples of physiologic functions that make use of this synergy.

We are also left with the questions of why some receptors like CXCR4 and CCR7 signal via the classical pathway in one cell type and via the alternative pathway in another cell type, and why mFPR1 signals via the classical pathway in inflammatory neutrophils and via the alternative pathway in bone marrow neutrophils. It is possible that there are simply more alternative pathways that are yet to be discovered and that these alternative pathways are also masked when the master regulator Gi is missing or inhibited. Indeed, there is data to suggest that the G12/G13 class of G proteins can also play a role in regulating the trafficking of some lymphocyte populations (66–68), and in HL-60 cells, G12/G13 was demonstrated to play a crucial role in cell polarity (69). Thus, it is likely that chemokine receptor signaling will be found to be even more heterogeneous, and that the simple generic chemokine receptor signaling model will need to be abandoned in favor of more complex models that illustrate how simple modifications of the signal transduction circuitry can generate different downstream physiologic consequences.

Finally, regardless of whether there are more alternative chemokine receptor signaling pathways awaiting discovery, our data illuminate a novel Gαq-coupled signaling pathway that regulates chemokine receptor signal transduction and chemotaxis. Most importantly, our data show that this novel Gαq-dependent pathway plays a critical and nonredundant role in cell migration. However, although the Gαq-dependent chemokine receptor signaling pathway is required for the migration of DCs and monocytes in vivo in response to inflammatory stimuli, it does not appear to be required for the in vivo immigration of leukocytes to secondary lymphoid organs and peripheral tissues under homeostatic conditions. Thus, further study of the Gαq-coupled chemokine receptor signaling pathway should allow us to identify other additional key signaling molecules that may be targets of drugs that can be used to inhibit chronic inflammation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and bone marrow reconstitutions.

C57BL/6J (B6), CD45.1+ congenic B6, C57BL/6J.129 Cd38−/− (N12 backcross to C57BL/6J) (28), Gnaq−/− (N>5 backcross to C57BL/6J) (70), and Gnai2−/− (N>5 backcross to C57BL/6J) (70) mice were bred and maintained in the Trudeau Institute breeding facility. Gnaq−/− mice are born runted and often do not live to adulthood (71). Therefore, all in vitro chemotaxis and calcium signaling assays were routinely performed using cells isolated from lethally irradiated B6 recipients that were reconstituted with B6, Gnaq−/−, or Gnai2−/− bone marrow 8 wk previously. This approach allowed us to examine the impact of Gαq protein deficiency specifically within hematopoietic lineage cells and permitted us to obtain cells from larger numbers of adult animals for the analyses. Bone marrow chimeric mice were generated by reconstituting lethally irradiated recipients (950 cGy from a 137Cs source) with 107 total bone marrow cells isolated from appropriate donor mice. Mice were allowed to reconstitute for 8 wk before experiments. The Trudeau Institute Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all procedures involving animals.

Reagents.

Reagents were obtained from R&D Systems (CXCL12, CCL3, and CCL19), Sigma-Aldrich (PAF, IL-8, fMLF, PTx, and DNFB), Calbiochem (2-APB), and BD Biosystems (all antibodies). 8Br-cADPR (provided by T. Walseth, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN) was prepared as previously described (72). All reagents were used at the concentrations indicated in the text and figure legends.

Cell subset quantification, cell purification, and chemotaxis assays.

Cells were isolated from the spleen, LNs (axillary and mesenteric), and skin epidermis of either WT or Gnaq−/− chimeric mice. The total number of viable cells was determined, the cells were stained with fluorochrome-labeled antibodies, and the total number of B cells (CD19+), T cells (CD3+ and CD4+ or CD8+), myeloid DCs (CD11c+CD11b+CD8α−), lymphoid DCs (CD11c+CD11b−CD8α+), plasmacytoid DCs (CD11cintGR1+B220int), and LCs (CD11c+I-Ab+Langerin+) was determined.

To purify bone marrow neutrophils, bone marrow cells were first stained with biotinylated anti-GR1 antibody and MACS streptavidin microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) and then positively selected on a MACS midi column. CD4 T cells were purified using CD4 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec). To isolate DCs, single-cell suspensions were prepared from pooled spleens and mesenteric, inguinal, and axillary LNs that were perfused with collagenase D and incubated for 60 min at 37°C. The cells were purified by two rounds of positive selection using biotinylated anti-CD11c antibody and streptavidin microbeads. The purity of all cell populations was routinely >90%. In vitro chemotaxis assays were performed using 24-well transwell plates (Costar) with either a 3-μm (for neutrophils) or 5-μm (DCs and T cells) pore size polycarbonate filter. In some experiments, the isolated cells were first pretreated for 20 min with 100 μM 8Br-cADPR. After any pretreatments, the cells were added to the top chamber of the transwell (105 DCs and 106 T cells or neutrophils per well, respectively). Transwell plates were incubated for 45 min (neutrophils) or 2 h (DCs and T cells). The transmigrated cells were collected from the lower chamber, fixed, and counted on a flow cytometer. The absolute number of cells in each sample was determined by spiking each sample with a known number of 20-μm fluorescent microbeads that were simultaneously counted on the flow cytometer. In some cases, the results are expressed as the mean ± SD of the chemotactic index (CI). The CI represents the fold increase in the number of migrated cells in response to chemoattractants over the spontaneous cell migration (to control medium).

Calcium mobilization assays.

107 bone marrow neutrophils and 106 DCs per milliliter were loaded with a mixture of Fluo-3 AM and Fura-red AM, as previously described (28, 29). In some experiments, the cells were preincubated for 20 min in 8Br-cADPR or 2-APB. In other experiments, cells were pretreated with 500 ng/ml PTx for 4 h, washed, and stimulated with chemokines. The accumulation of intracellular free calcium was assessed by flow cytometry by measuring the fluorescence emission of Fluo-3 in the FL-1 channel and Fura-red in the FL-3 channel over time. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (version 3.0; TreeStar, Inc.). Relative intracellular free calcium levels are expressed as the ratio between Fluo-3 and Fura-red mean fluorescence intensity.

In vivo DC activation and migration assays.

To measure the migration of monocytes to the skin, we followed the protocol described by Merad et al. (41). In brief, CD45.1+ B6 recipient mice were lethally irradiated and reconstituted with either CD45.2+ B6 bone marrow or with CD45.2+ Gnaq−/− bone marrow. 8 wk after reconstitution, cells from skin epidermal sheets were isolated (73) and stained with antibodies to CD45.1, CD45.2, CD11c, and ClassII to determine whether the LCs (CD11c+ClassII+) were of donor (CD45.2+) or host (CD45.1+) origin. The remaining mice were then exposed to DNFB (0.5% applied to the ear). On day 4 after DNFB application, cells were isolated from skin epidermal sheets and stained with the same panel of antibodies. The number of donor (CD45.2+) and host-derived (CD45.1+) LCs (CD11c+ClassII+) present in the skin samples was then determined by cell counting and FACS.

To track DC migration from inflamed skin to LNs, 25 μl FITC (8 mg/ml in 1:1 acetone/dibutylphthalate) was applied to two shaved abdominal areas of B6 or Gnaq−/− (nonchimeric) animals. Inguinal LNs were removed after 18–24 h, counted, stained with antibodies to class II and CD11c, and analyzed by flow cytometry. The total number of migrated FITChiCD11c+classII+ DCs was determined.

Immunohistology.

5-μm frozen sections were prepared from inguinal LNs isolated from FITC-sensitized mice at 18 h after exposure. Sections were stained with antibodies to CD11c (conjugated to Alexa Fluor 594; Invitrogen) and CD90.2 (conjugated to Alexa Fluor 350; Invitrogen). Slides were viewed at 200× magnification using a microscope (Axiophot 2; Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.), and images were captured with a digital camera (AxioCam; Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.) using Axiovision software (version 3.0; Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.). Images were cropped and scaled using Canvas software (version 9.0; ACD Systems).

Statistical analysis.

Datasets were analyzed using Prism software (version 4.0 for Macintosh; GraphPad Software). Student's t tests were applied to the datasets, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data are shown as the mean ± SD.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Troy Randall for critically evaluating this manuscript and Dr. Tim Walseth for providing us with the 8Br-cADPR used in this study.

This work was supported by the Trudeau Institute and National Institutes of Health grant AI-057996.

The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

Abbreviations used: 2-APB, 2-aminoethoxydiphenylborate; ADPR, adenosine diphosphoribose; cADPR, cyclic ADPR; CCL and CCR, CC chemokine ligand and receptor, respectively; CI, chemotactic index; CXCL and CXCR, CXC chemokine ligand and receptor, respectively; DNFB, dinitrofluorobenzene; fMLF, N-formyl methionyl leucyl phenylalanine; IP3, inositol trisphosphate; LC, Langerhans cell; mFPR, mouse formyl peptide receptor; NAD+, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; PAF, platelet-activating factor; PLC, phospholipase; PTx, pertussis toxin.

G. Shi and S. Partida-Sánchez contributed equally to this work.

S. Partida-Sánchez's present address is Dept. of Pediatrics, Columbus Children's Research Institute, Columbus, OH 43205.

References

- 1.Wettschureck, N., and S. Offermanns. 2005. Mammalian G proteins and their cell type specific functions. Physiol. Rev. 85:1159–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polakis, P.G., R.J. Uhing, and R. Snyderman. 1988. The formylpeptide chemoattractant receptor copurifies with a GTP-binding protein containing a distinct 40-kDa pertussis toxin substrate. J. Biol. Chem. 263:4969–4976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ye, R.D., O. Quehenberger, K.M. Thomas, J. Navarro, S.L. Cavanagh, E.R. Prossnitz, and C.G. Cochrane. 1993. The rabbit neutrophil N-formyl peptide receptor. cDNA cloning, expression, and structure/function implications. J. Immunol. 150:1383–1394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schreiber, R.E., E.R. Prossnitz, R.D. Ye, C.G. Cochrane, A.J. Jesaitis, and G.M. Bokoch. 1993. Reconstitution of recombinant N-formyl chemotactic peptide receptor with G protein. J. Leukoc. Biol. 53:470–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Damaj, B.B., S.R. McColl, W. Mahana, M.F. Crouch, and P.H. Naccache. 1996. Physical association of Gi2alpha with interleukin-8 receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 271:12783–12789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neptune, E.R., and H.R. Bourne. 1997. Receptors induce chemotaxis by releasing the betagamma subunit of Gi, not by activating Gq or Gs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94:14489–14494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neptune, E.R., T. Iiri, and H.R. Bourne. 1999. Galphai is not required for chemotaxis mediated by Gi-coupled receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 274:2824–2828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirsch, E., V.L. Katanaev, C. Garlanda, O. Azzolino, L. Pirola, L. Silengo, S. Sozzani, A. Mantovani, F. Altruda, and M.P. Wymann. 2000. Central role for G protein-coupled phosphoinositide 3-kinase γ in inflammation. Science. 287:1049–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sasaki, T., J. Sasaki-Irie, R.G. Jones, A.J. Oliveira-dos-Santos, W.L. Stanford, B. Bolon, A. Wakeham, A. Itie, D. Bouchard, I. Kozieradzki, et al. 2000. Function of P13Kγ in thymocyte development, T cell activation, and neutrophil migration. Science. 287:1040–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li, Z., H. Jiang, W. Xie, Z. Zhang, A.V. Smrcka, and D. Wu. 2000. Roles of PLC-β2 and -β3 and PI3Kγ in chemoattractant mediated signal transduction. Science. 287:1046–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Camps, M., C.F. Hou, K.H. Jakobs, and P. Gierschik. 1990. Guanosine 5′-[gamma-thio]triphosphate-stimulated hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate in HL-60 granulocytes. Evidence that the guanine nucleotide acts by relieving phospholipase C from an inhibitory constraint. Biochem. J. 271:743–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Camps, M., C. Hou, D. Sidiropoulos, J.B. Stock, K.H. Jakobs, and P. Gierschik. 1992. Stimulation of phospholipase C by guanine-nucleotide-binding protein beta gamma subunits. Eur. J. Biochem. 206:821–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berridge, M.J. 2005. Unlocking the secrets of cell signaling. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 67:1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brandt, S.J., R.W. Dougherty, E.G. Lapetina, and J.E. Niedel. 1985. Pertussis toxin inhibits chemotactic peptide-stimulated generation of inositol phosphates and lysosomal enzyme secretion in human leukemic (HL-60) cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 82:3277–3280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Becker, E.L., J.C. Kermode, P.H. Naccache, R. Yassin, M.L. Marsh, J.J. Munoz, and R.I. Sha'afi. 1985. The inhibition of neutrophil granule enzyme secretion and chemotaxis by pertussis toxin. J. Cell Biol. 100:1641–1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldman, D.W., F.H. Chang, L.A. Gifford, E.J. Goetzl, and H.R. Bourne. 1985. Pertussis toxin inhibition of chemotactic factor–induced calcium mobilization and function in human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J. Exp. Med. 162:145–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thelen, M. 2001. Dancing to the tune of chemokines. Nat. Immunol. 2:129–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Partida-Sanchez, S., L. Rivero-Nava, G. Shi, and F.E. Lund. 2007. CD38: an ecto-enzyme at the crossroads of innate and adaptive immune responses. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 590:171–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howard, M., J.C. Grimaldi, J.F. Bazan, F.E. Lund, L. Santos-Argumedo, R.M.E. Parkhouse, T.F. Walseth, and H.C. Lee. 1993. Formation and hydrolysis of cyclic ADP-ribose catalyzed by lymphocyte antigen CD38. Science. 262:1056–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deaglio, S., and F. Malavasi. 2002. Human CD38: a receptor, an (ecto) enzyme, a disease marker and lots more. Mod. Asp. Immunobiol. 2:121–125. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lund, F.E., D.A. Cockayne, T.D. Randall, N. Solvason, F. Schuber, and M.C. Howard. 1998. CD38: a new paradigm in lymphocyte activation and signal transduction. Immunol. Rev. 161:79–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schuber, F., and F.E. Lund. 2004. Structure and enzymology of ADP-ribosyl cyclases: conserved enzymes that produce multiple calcium mobilizing metabolites. Curr. Mol. Med. 4:249–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee, H.C. 2006. Structure and enzymatic functions of human CD38. Mol. Med. 12:317–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuhn, F.J., I. Heiner, and A. Luckhoff. 2005. TRPM2: a calcium influx pathway regulated by oxidative stress and the novel second messenger ADP-ribose. Pflugers Arch. 451:212–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kolisek, M., A. Beck, A. Fleig, and R. Penner. 2005. Cyclic ADP-ribose and hydrogen peroxide synergize with ADP-ribose in the activation of TRPM2 channels. Mol. Cell. 18:61–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gasser, A., G. Glassmeier, R. Fliegert, M.F. Langhorst, S. Meinke, D. Hein, S. Kruger, K. Weber, I. Heiner, N. Oppenheimer, et al. 2006. Activation of T cell calcium influx by the second messenger ADP-ribose. J. Biol. Chem. 281:2489–2496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beck, A., M. Kolisek, L.A. Bagley, A. Fleig, and R. Penner. 2006. Nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate and cyclic ADP-ribose regulate TRPM2 channels in T lymphocytes. FASEB J. 20:962–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Partida-Sanchez, S., D.A. Cockayne, S. Monard, E.L. Jacobson, N. Oppenheimer, B. Garvy, K. Kusser, S. Goodrich, M. Howard, A. Harmsen, et al. 2001. Cyclic ADP-ribose production by CD38 regulates intracellular calcium release, extracellular calcium influx and chemotaxis in neutrophils and is required for bacterial clearance in vivo. Nat. Med. 7:1209–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Partida-Sanchez, S., S. Goodrich, K. Kusser, N. Oppenheimer, T.D. Randall, and F.E. Lund. 2004. Regulation of dendritic cell trafficking by the ADP-ribosyl cyclase CD38: impact on the development of humoral immunity. Immunity. 20:279–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Partida-Sanchez, S., T.D. Randall, and F.E. Lund. 2003. Innate immunity is regulated by CD38, an ecto-enzyme with ADP-ribosyl cyclase activity. Microbes Infect. 5:49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Partida-Sanchez, S., P. Iribarren, M.E. Moreno-Garcia, J.-L. Gao, P.M. Murphy, N. Oppenheimer, J.M. Wang, and F.E. Lund. 2004. Chemotaxis and calcium responses of phagocytes to formyl-peptide receptor ligands is differentially regulated by cyclic ADP-ribose. J. Immunol. 172:1896–1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu, D.Q., C.H. Lee, S.G. Rhee, and M.I. Simon. 1992. Activation of phospholipase C by the alpha subunits of the Gq and G11 proteins in transfected Cos-7 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 267:1811–1817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee, C.H., D. Park, D. Wu, S.G. Rhee, and M.I. Simon. 1992. Members of the Gq alpha subunit gene family activate phospholipase C beta isozymes. J. Biol. Chem. 267:16044–16047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Verghese, M.W., L. Charles, L. Jakoi, S.B. Dillon, and R. Snyderman. 1987. Role of a guanine nucleotide regulatory protein in the activation of phospholipase C by different chemoattractants. J. Immunol. 138:4374–4380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Amatruda, T.T., III, N.P. Gerard, C. Gerard, and M.I. Simon. 1993. Specific interactions of chemoattractant factor receptors with G-proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 268:10139–10144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haribabu, B., D.V. Zhelev, B.C. Pridgen, R.M. Richardson, H. Ali, and R. Snyderman. 1999. Chemoattractant receptors activate distinct pathways for chemotaxis and secretion. Role of G-protein usage. J. Biol. Chem. 274:37087–37092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang, H., Y. Kuang, Y. Wu, W. Xie, M.I. Simon, and D. Wu. 1997. Roles of phospholipase C beta2 in chemoattractant-elicited responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94:7971–7975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cyster, J.G., and C.C. Goodnow. 1995. Pertussis toxin inhibits migration of B and T lymphocytes into splenic white pulp cords. J. Exp. Med. 182:581–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mathew, A., B.D. Medoff, A.D. Carafone, and A.D. Luster. 2002. Cutting edge: Th2 cell trafficking into the allergic lung is dependent on chemoattractant receptor signaling. J. Immunol. 169:651–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bonasio, R., M.L. Scimone, P. Schaerli, N. Grabie, A.H. Lichtman, and U.H. von Andrian. 2006. Clonal deletion of thymocytes by circulating dendritic cells homing to the thymus. Nat. Immunol. 7:1092–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Merad, M., M.G. Manz, H. Karsunky, A. Wagers, W. Peters, I. Charo, I.L. Weissman, J.G. Cyster, and E.G. Engleman. 2002. Langerhans cells renew in the skin throughout life under steady-state conditions. Nat. Immunol. 3:1135–1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luster, A.D., R. Alon, and U.H. von Andrian. 2005. Immune cell migration in inflammation: present and future therapeutic targets. Nat. Immunol. 6:1182–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kehrl, J.H. 2006. Chemoattractant receptor signaling and the control of lymphocyte migration. Immunol. Res. 34:211–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gerard, C., and N.P. Gerard. 1994. The pro-inflammatory seven-transmembrane segment receptors of the leukocyte. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 6:140–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Amatruda, T.T., III, S. Dragas-Graonic, R. Holmes, and H.D. Perez. 1995. Signal transduction by the formyl peptide receptor. Studies using chimeric receptors and site-directed mutagenesis define a novel domain for interaction with G-proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 270:28010–28013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wittmann, S., D. Frohlich, and S. Daniels. 2002. Characterization of the human fMLP receptor in neutrophils and in Xenopus oocytes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 135:1375–1382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arai, H., and I.F. Charo. 1996. Differential regulation of G-protein-mediated signaling by chemokine receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 271:21814–21819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu, D., G.J. LaRosa, and M.I. Simon. 1993. G protein-coupled signal transduction pathways for interleukin-8. Science. 261:101–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Offermanns, S., and M.I. Simon. 1995. G alpha 15 and G alpha 16 couple a wide variety of receptors to phospholipase C. J. Biol. Chem. 270:15175–15180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang, M., H. Sang, A. Rahman, D. Wu, A.B. Malik, and R.D. Ye. 2001. Ga16 couples chemoattractant receptors to NF-κB activation. J. Immunol. 166:6885–6892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shahrestanifar, M., X. Fan, and D.R. Manning. 1999. Lysophosphatidic acid activates NF-kappaB in fibroblasts. A requirement for multiple inputs. J. Biol. Chem. 274:3828–3833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bacon, K.B., B.A. Premack, P. Gardner, and T.J. Schall. 1995. Activation of dual T cell signaling pathways by the chemokine RANTES. Science. 269:1727–1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Giannini, E., and F. Boulay. 1995. Phosphorylation, dephosphorylation, and recycling of the C5a receptor in differentiated HL60 cells. J. Immunol. 154:4055–4064. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Amara, A., S.L. Gall, O. Schwartz, J. Salamero, M. Montes, P. Loetscher, M. Baggiolini, J.L. Virelizier, and F. Arenzana-Seisdedos. 1997. HIV coreceptor downregulation as antiviral principle: SDF-1α–dependent internalization of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 contributes to inhibition of HIV replication. J. Exp. Med. 186:139–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Feniger-Barish, R., D. Belkin, A. Zaslaver, S. Gal, M. Dori, M. Ran, and A. Ben-Baruch. 2000. GCP-2-induced internalization of IL-8 receptors: hierarchical relationships between GCP-2 and other ELR(+)-CXC chemokines and mechanisms regulating CXCR2 internalization and recycling. Blood. 95:1551–1559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sozzani, S., D. Zhou, M. Locati, M. Rieppi, P. Proost, M. Magazin, N. Vita, J. van Damme, and A. Mantovani. 1994. Receptors and transduction pathways for monocyte chemotactic protein-2 and monocyte chemotactic protein-3. Similarities and differences with MCP-1. J. Immunol. 152:3615–3622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maghazachi, A.A., A. al-Aoukaty, and T.J. Schall. 1994. C-C chemokines induce the chemotaxis of NK and IL-2-activated NK cells. Role for G proteins. J. Immunol. 153:4969–4977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maghazachi, A.A., B.S. Skalhegg, B. Rolstad, and A. Al-Aoukaty. 1997. Interferon-inducible protein-10 and lymphotactin induce the chemotaxis and mobilization of intracellular calcium in natural killer cells through pertussis toxin-sensitive and -insensitive heterotrimeric G-proteins. FASEB J. 11:765–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang, L.V., C.G. Radu, L. Wang, M. Riedinger, and O.N. Witte. 2005. Gi-independent macrophage chemotaxis to lysophosphatidylcholine via the immunoregulatory GPCR G2A. Blood. 105:1127–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wilkie, T.M., P.A. Scherle, M.P. Strathmann, V.Z. Slepak, and M.I. Simon. 1991. Characterization of G-protein alpha subunits in the Gq class: expression in murine tissues and in stromal and hematopoietic cell lines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 88:10049–10053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shi, G.X., K. Harrison, S.B. Han, C. Moratz, and J.H. Kehrl. 2004. Toll-like receptor signaling alters the expression of regulator of G protein signaling proteins in dendritic cells: implications for G protein-coupled receptor signaling. J. Immunol. 172:5175–5184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kuang, Y., Y. Wu, H. Jiang, and D. Wu. 1996. Selective G protein coupling by C-C chemokine receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 271:3975–3978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Borchers, M.T., P.J. Justice, T. Ansay, V. Mancino, M.P. McGarry, J. Crosby, M.I. Simon, N.A. Lee, and J.J. Lee. 2002. Gq signaling is required for allergen-induced pulmonary eosinophilia. J. Immunol. 168:3543–3549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hubbard, K.B., and J.R. Hepler. 2006. Cell signalling diversity of the Gqalpha family of heterotrimeric G proteins. Cell. Signal. 18:135–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Werry, T.D., G.F. Wilkinson, and G.B. Willars. 2003. Mechanisms of cross-talk between G-protein-coupled receptors resulting in enhanced release of intracellular Ca2+. Biochem. J. 374:281–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Girkontaite, I., K. Missy, V. Sakk, A. Harenberg, K. Tedford, T. Potzel, K. Pfeffer, and K.D. Fischer. 2001. Lsc is required for marginal zone B cells, regulation of lymphocyte motility and immune responses. Nat. Immunol. 2:855–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sugimoto, N., N. Takuwa, H. Okamoto, S. Sakurada, and Y. Takuwa. 2003. Inhibitory and stimulatory regulation of Rac and cell motility by the G12/13-Rho and Gi pathways integrated downstream of a single G protein-coupled sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor isoform. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:1534–1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rubtsov, A., P. Strauch, A. Digiacomo, J. Hu, R. Pelanda, and R.M. Torres. 2005. Lsc regulates marginal-zone B cell migration and adhesion and is required for the IgM T-dependent antibody response. Immunity. 23:527–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xu, J., F. Wang, A. Van Keymeulen, P. Herzmark, A. Straight, K. Kelly, Y. Takuwa, N. Sugimoto, T. Mitchison, and H.R. Bourne. 2003. Divergent signals and cytoskeletal assemblies regulate self-organizing polarity in neutrophils. Cell. 114:201–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pero, R.S., M.T. Borchers, K. Spicher, S.I. Ochkur, L. Sikora, S.P. Rao, H. Abdala-Valencia, K.R. O'Neill, H. Shen, M.P. McGarry, et al. 2007. Galphai2-mediated signaling events in the endothelium are involved in controlling leukocyte extravasation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104:4371–4376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Offermanns, S., K. Hashimoto, M. Watanabe, W. Sun, H. Kurihara, R.F. Thompson, Y. Inoue, M. Kano, and M.I. Simon. 1997. Impaired motor coordination and persistent multiple climbing fiber innervation of cerebellar Purkinje cells in mice lacking Galphaq. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94:14089–14094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Walseth, T.F., and H.C. Lee. 2002. Pharmacology of cyclic ADP-ribose and NAADP: synthesis and properties of analogues. In Cyclic ADP-Ribose and NAADP. Structures, Metabolism and Functions. H.C. Lee, editor. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Boston. 121–142.

- 73.Koch, F., E. Kampgen, G. Schuler, and N. Romani. 2001. Isolation, enrichment and culture of murine epidermal Langerhans cells. In Methods in Molecular Medicine. S.P. Robinson and A.J. Stagg, editors. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ. 43–62. [DOI] [PubMed]