Abstract

It is well established that synaptic transmission declines at temperatures below physiological, but many in vitro studies are conducted at lower temperatures. Recent evidence suggests that temperature-dependent changes in presynaptic mechanisms remain in overall equilibrium and have little effect on transmitter release at low transmission frequencies. Our objective was to examine the postsynaptic effects of temperature. Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings from principal neurons in the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body showed that a rise from 25°C to 35°C increased miniature EPSC (mEPSC) amplitude from −33 ± 2.3 to −46 ± 5.7 pA (n = 6) and accelerated mEPSC kinetics. Evoked EPSC amplitude increased from −3.14 ± 0.59 to −4.15 ± 0.73 nA with the fast decay time constant accelerating from 0.75 ± 0.09 ms at 25°C to 0.56 ± 0.08 ms at 35°C. Direct application of glutamate produced currents which similarly increased in amplitude from −0.76 ± 0.10 nA at 25°C to −1.11 ± 0.19 nA 35°C. Kinetic modelling of fast AMPA receptors showed that a temperature-dependent scaling of all reaction rate constants by a single multiplicative factor (Q10 = 2.4) drives AMPA channels with multiple subconductances into the higher-conducting states at higher temperature. Furthermore, Monte Carlo simulation and deconvolution analysis of transmission at the calyx of Held showed that this acceleration of the receptor kinetics explained the temperature dependence of both the mEPSC and evoked EPSC. We propose that acceleration in postsynaptic AMPA receptor kinetics, rather than altered presynaptic release, is the primary mechanism by which temperature changes alter synaptic responses at low frequencies.

From a physiological perspective, control of mammalian body temperature in the range of 37–38°C is crucial for normal brain activity, with function becoming seriously impaired during hypothermia when core temperature drops below 32°C (Kumar & Clark, 2002). Synaptic transmission in mammals is adapted to 37°C and extrapolation of data from studies at low temperatures is problematic because of its multifactorial nature (Micheva & Smith, 2005). Many in vitro studies are conducted at lower temperatures to aid tissue survival and improve voltage clamp of conductances with rapid kinetics. Characterization of the temperature dependence of synaptic transmission will allow closer comparison of in vitro and in vivo data and give some insight into central mechanisms of hypothermia.

The calyx of Held synapse onto neurons of the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body (MNTB) has become an important model of central synaptic transmission (Schneggenburger & Forsythe, 2006). Located in the auditory pathway, it contributes to sound source localization (Grothe, 2003) involving interaural timing and level discrimination. Its large size and somatic location allow in vitro recording of fast AMPA receptor (AMPAR)-mediated glutamatergic EPSCs (Forsythe & Barnes-Davies, 1993b; Forsythe, 1994; Barnes-Davies & Forsythe, 1995; Borst et al. 1995; Taschenberger & von Gersdorff, 2000) and miniature EPSCs (mEPSCs) caused by the release of single quanta of glutamate (Sahara & Takahashi, 2001).

Presynaptic calyceal recordings show that raised temperature reduced presynaptic action potential amplitude and duration (Kushmerick et al. 2006) leading to reduced calcium influx (Borst & Sakmann, 1998). So although the readily releasable pool size and vesicle recycling rates are enhanced at physiological temperatures (Pyott & Rosenmund, 2002), thus reducing short-term depression (Taschenberger & von Gersdorff, 2000; Kushmerick et al. 2006), action potential-induced transmitter release is slightly reduced (Pyott & Rosenmund, 2002) or unchanged during single EPSCs (Kushmerick et al. 2006). There is evidence that temperature changes alter postsynaptic response (e.g. Asztely et al. 1997; Kidd & Isaac, 2001) however, relatively little information is available from CNS synapses.

The aim of the present study was to characterize the effect of temperature on synaptic AMPARs using spontaneous mEPSCs and evoked synaptic currents (EPSCs) at the calyx of Held. Computational modelling of AMPARs was employed to determine how temperature influenced mEPSCs. Monte Carlo techniques simulating mEPSCs at different temperatures support the hypothesis that acceleration of postsynaptic AMPAR reaction kinetics is the predominant factor in determining the temperature sensitivity of synaptic transmission. The results demonstrate that the increase in synaptic strength with raised temperature is a postsynaptic mechanism due to opening of AMPARs to higher conducting states.

Methods

Preparation of brain slices

Lister-Hooded rats (10–11 days old) were killed by decapitation in accordance with the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 and brainstem slices containing the superior olivary complex (SOC) were prepared as previously described (Wong et al. 2003). Briefly, 220 μm-thick transverse slices of SOC containing the MNTB were cut in a low-sodium artificial CSF (aCSF) at ∼0°C. Slices were then maintained in a normal aCSF at 37°C for 1 h, after which they were stored at room temperature (∼20°C). Composition of the normal aCSF was (mm): NaCl 125, KCl 2.5, NaHCO3 26, glucose 10, NaH2PO4 1.25, sodium pyruvate 2, myo-inositol 3, CaCl2 2, MgCl2 1 and ascorbic acid 0.5; pH was 7.4, bubbled with 95% O2–95% CO2. For the low-sodium aCSF, NaCl was replaced by 250 mm sucrose, and CaCl2 and MgCl2 concentrations were changed to 0.1 and 4 mm, respectively.

Electrophysiology and imaging

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were made from MNTB neurons (visualized at 40 × with a Zeiss Axioskop fitted with differential interference contrast optics) using a Multiclamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and pCLAMP9 software (Molecular Devices), sampling at 50 kHz and filtering at 10 kHz. Patch pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass capillaries containing an internal filament (GC150F-7.5, outer diameter, 1.5 mm; inner diameter, 0.86 mm; Harvard Apparatus, Edenbridge, UK) using a two-stage vertical puller (PC-10 Narishige, Tokyo, Japan). Pipettes had a final open-tip resistance of ∼3.5 MΩ when filled with a solution containing (mm): potassium gluconate 97.5, KCl 32.5, Hepes 10, EGTA 5, MgCl2 1 and QX-314 5; pH was adjusted to 7.3 with KOH. Whole-cell access resistance was < 20 MΩ and series resistance was routinely compensated by 70%. EPSCs were evoked by stimulation with a bipolar platinum electrode placed at the midline across the slice and using a DS2A isolated stimulator (∼8 V, 0.02 ms; Digitimer, Welwyn Garden City, UK).

Synaptic connections were detected using an imaging technique previously described (Billups et al. 2002). Briefly, cells were loaded with 7 μm acetoxymethyl ester form of Fura2 (Fura2-AM; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) for ∼4 min and then viewed using a Photometrics CoolSNAP-fx camera after a single 100 ms exposure to 380 nm (provided by a xenon arc lamp controlled by a Cairn Optoscan monochromater; Cairn Instruments, Faversham, UK). The fluorescent image was displayed using Metafluor imaging software (version 4.01, Molecular Devices) and regions of interest were drawn around visualized neurons. A stimulus train was delivered (200 Hz, 200 ms) and synaptically connected cells were identified by a decrease in the 380 nm signal brought about by the postsynaptic rise in calcium concentration. These cells were then located and patch clamped.

Recordings were taken at specified temperatures between 25°C and 38°C; the bath temperature was feedback controlled by a Peltier device warming the aCSF passing through a rapid-flow perfusion system. A small volume (∼800 μl) tissue bath was used to allow fast temperature equilibration, and a ceramic water-immersion objective coated with Sylgard was used to minimize local heat loss. Regular calibration of temperature was carried out, with the bath temperature stable within ±1°C. MNTB cells were voltage clamped at a holding potential of −60 mV. EPSCs were elicited at a frequency 0.2 Hz to minimize short-term depression and where possible, temperature was varied while maintaining patch recording from individual neurons so each cell acted as its own control. mEPSCs were extracted from traces using the ‘event detection’ tool in pClamp9 (Molecular Devices). All drugs were applied by bath perfusion in the aCSF. Drugs used were tetrodotoxin (TTX; Latoxan, Rosans, France), 6,7-dinitroquinoxaline-2, 3-dione (DNQX) and kynurenate (Tocris, UK).

Pressure application of glutamate

Puffing experiments were performed using a Picospritzer III (Intracel) connected to a 3.5 MΩ electrode filled with 5 mm glutamate in aCSF. The tip of the electrode was placed near a patch-clamped MNTB neuron and the maximal response to the agonist was optimized by mapping pipette positions. Pulses of 3 ms (10 PSI) were applied every 8 s in the presence of TTX and kynurenate at 25°C or 35°C as indicated.

Statistics

Data are presented as means ± s.e.m. and significance verified using a two-tailed paired t test or Wilcoxon signed rank test on raw data, with P < 0.05 being considered significant.

Modelling

Glutamate diffusion and binding to AMPARs at the calyx of Held was modelled using MCell version 2.76 (Stiles & Bartol, 2001; http://www.mcell.salk.edu/) which employs Monte Carlo algorithms to simulate the three-dimensional diffusion of individual ligand molecules and allows for the inclusion of effector sites to simulate ligand binding. All simulations were carried out with a time step of 1 μs. The MCell code is available for download at ModelDB: http://senselab.med.yale.edu/senselab/ModelDB/default.asp.

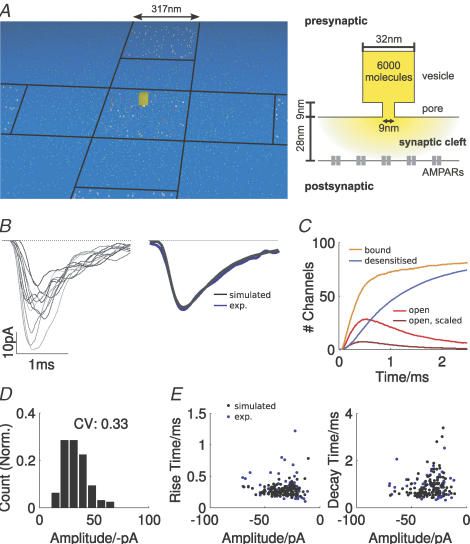

Synaptic geometry

The model consists of a single active zone (AZ) where glutamate is released from a vesicle; its associated postsynaptic density (PSD) and neighbouring PSDs were included. The geometry of a calyceal AZ was constructed according to morphological data given by Sätzler et al. (2002) (Fig. 3A). Quadratic sections of pre- and postsynaptic membrane were separated by a cleft of 28 nm. PSDs with an area of 0.32 μm × 0.32 μm and separated by 317 nm were populated with 80 AMPARs each. Glutamate was released from a single vesicle above the central PSD. The location of the vesicle relative to the PSD was variable, and for a given set of simulations the location was assumed to be randomly distributed above the area of the PSD in each trial (Franks et al. 2003). The case where the vesicle was not constrained to the area above the PSD was also considered.

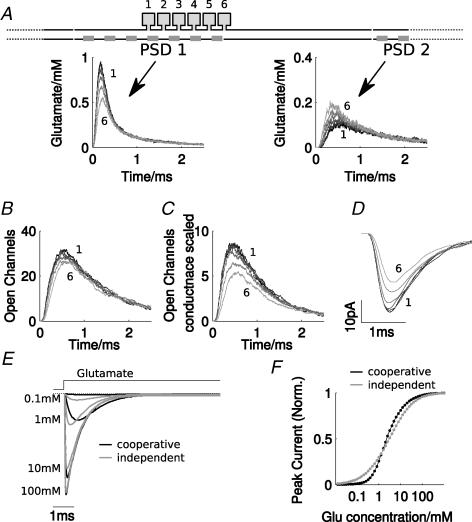

Figure 3. Site of exocytosis contributes to mEPSC variability.

A, location of exocytosis was progressively shifted from a central site (1) to the periphery (6) as shown in the upper schematic diagram. Time course of the glutamate concentration in the synaptic cleft above the central PSD was plotted (where vesicular release occurs, PSD 1, left) and a neighbouring PSD (PSD 2, right) for releases at six different locations relative to PSD 1. B, average number of open AMPAR channels during a release at the different locations shown in panel A. C, as B, but with the open channel count scaled by the respective unitary conductance value. D, the resulting average postsynaptic currents for each of the six cases. E, simulated current generated by AMPARs during sustained application of glutamate at different concentrations for the model implementing cooperative binding (black traces, see Methods), and a variant that assumes independent binding (grey traces), which also reproduces the average mEPSC time course (parameters used: kB= 8; kU= 4.3). F, dose–response relations for the cooperative and independent binding model. The simulations in E and F were carried out in NEURON (Hines & Carnevale, 1997) and did not include a stochastic component.

A vesicle was modelled as a cube with a side length of 32 nm, corresponding to a volume of 3.3 × 10−23 m3 (equivalent to a spherical vesicle with a diameter of 46 nm as given by Sätzler et al. (2002), which was corrected for a membrane thickness of 6 nm). The vesicle was connected to the synaptic cleft by a fusion pore, which was modelled as a box with a height of 9 nm (about 1.5-fold greater than the membrane thickness) and a variable diameter (Stiles et al. 1996; Franks et al. 2003). At the beginning of a release, the fusion pore was gradually opened according to dfp(t) = dmax (1−e−at), where t is the time in ms, a was 0.01 ms−1, the diameter dmax was taken as 9 nm, and a value of dmax of 11 nm was also investigated.

To reproduce the observed variability of mEPSCs (see Results; Franks et al. 2003; Raghavachari & Lisman, 2004), the precise location of the vesicle was assumed to be uniformly distributed over an area restricted to 200 nm relative to the centre of this PSD. This was approximated by running multiple simulations of releases at six different radii (see Fig. 3A, top). To account for the higher probability of observing a release further away from the centre of the PSD (because the circumference of the circles defined by each radius increases with distance, and a release can occur at any location on this circle), the number of individual releases at each radius contributing to the average mEPSC was then chosen such that a uniform coverage of the area was obtained.

Glutamate concentration and diffusion

The glutamate content of the vesicle was adjusted such that the peak glutamate concentration in the synaptic cleft did not exceed 1 mm during a release (Clements et al. 1992). The peak concentration was typically reached, depending on the diffusion coefficient (D) and fusion pore dynamics, at around 300–500 μs after the beginning of the fusion process. The vesicle contained 6000 glutamate molecules, which corresponds to a vesicular concentration of 302 mm. The diffusion coefficient for glutamate was set to D = 3 × 10−6 cm2 s−1, as it is likely to be lower than in aqueous solution (D = 7.5 × 10−6 cm2 s−1 for glutamine; Longsworth, 1953) as a result of increased viscosity of the intracellular medium and additional diffusion barriers (Rusakov & Kullmann, 1998). This value, however, was not critical for the results shown here, as it was possible to obtain precise fits of the miniature events with values in the range of D = 2−6 × 10−6 cm2 s−1 by adjusting the rate constants of the AMPAR model accordingly. To constrain the value of D, the AMPAR rate constants for channel opening and closing were initially set to the values reported by Robert & Howe (2003) for the GLUR4 AMPA receptor (see below), and then D was estimated to allow for best fits to the experimental data.

AMPAR model

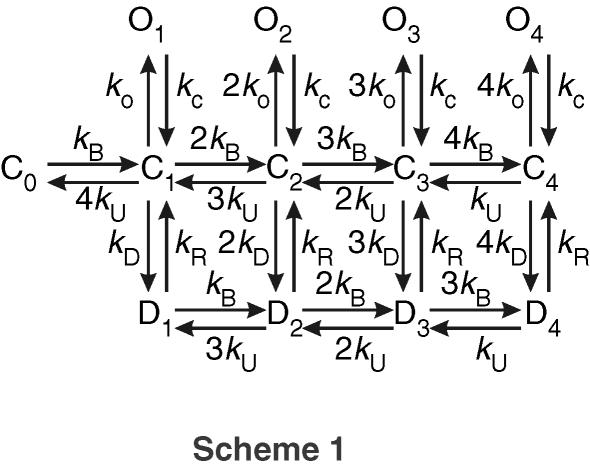

To simulate postsynaptic AMPAR gating, a kinetic model of the GluR4 channel was constructed based on earlier work by Robert & Howe (2003) as shown in Scheme 1. This model is based on the following experimental findings.

Scheme 1.

(1) AMPARs are tetramers (Rosenmund et al. 1998); each subunit binds one agonist molecule and from each of these closed bound states (C1–C4), a transition into an open (O1–O4) or desensitized (D1–D4) state is possible (Armstrong & Gouaux, 2000; Sun et al. 2002; Jin et al. 2003). Some earlier models assumed that desensitization can also occur from bound states where channel opening is not possible (Vyklicky et al. 1991; Raman & Trussell, 1995; Robert & Howe, 2003). This may, however, result from the low conductance associated with this state (see below) that cannot be resolved in noisy recordings (Clements et al. 1998; Smith et al. 2000; Sun et al. 2002). (2) Agonist binding and unbinding is assumed to take place from closed and desensitized states, with little or no contribution from open states (Armstrong & Gouaux, 2000). Hence receptor occupancy can change between closed and desensitized states in this model. (3) The conductance of AMPA channels depends on the occupancy by agonist molecules (Swanson et al. 1997; Rosenmund et al. 1998; Smith & Howe, 2000; Smith et al. 2000; Jin et al. 2003; Gebhardt & Cull-Candy, 2006). These experimental data suggest that successive binding to the four AMPAR subunits affects the channel conductance and the data of Smith et al. (2000) suggests that high-conductance channels, such as those found at the calyx of Held (Sahara & Takahashi, 2001), have four clearly resolvable conductances. The respective conductances were set as fractions of the peak conductance at the 4-fold bound state (O4; 0.1, 0.4 and 0.7). All simulation parameters are summarized in Table 1. (4) Glutamate binding was assumed to be cooperative, which is reflected by the increasing factors for kB. This departure from the model by Robert & Howe (2003) was motivated by comparison of simulations with experimental data (see Results; Fig. 3). A cooperative binding model was also proposed by Clements et al. (1998) and Raghavachari & Lisman (2004). (5) Assuming an acceleration of transition between different conformational states with increased temperature, the dependency of AMPAR kinetics on temperature was modelled by scaling the rate constants with a multiplicative factor. This assumption implies that all conformal changes in AMPARs may be accelerated uniformly with increased temperature. Other combinations were also investigated.

Table 1.

Parameters for the kinetic AMPA receptor model: see text

| Parameter | Description | Value |

|---|---|---|

| kB | Agonist binding rate | 10 × 106m−1 s−1 |

| kU | Agonist unbinding rate | 8 × 103 s−1 |

| kO | Channel opening rate | 20 × 103 s−1 |

| kC | Channel closing rate | 10 × 103 s−1 |

| kD | Desensitization rate | 4 s−1 |

| kR | Resensitization rate | 15 s−1 |

| gi | Channel conductances | 6, 24, 42, 60 pA |

AMPAR-mediated currents

During the MCell simulations, the occurrences of all AMPAR reaction intermediates were counted at each iteration. The postsynaptic current was then generated by assigning each open state the respective conductance and by simulating voltage clamp at −60 mV with a reversal potential of +7 mV. All currents were, as in the experiments, filtered at 10 kHz.

Fitting mEPSCs

A combination of simulations with MCell and NEURON (Hines & Carnevale, 1997) was used to produce the fits to the experimentally obtained miniature events (Hines & Carnevale, 1997). The AMPAR model was implemented using NMODL (Hines & Carnevale, 2000) and AMPAR rate constants were optimized by least-square fitting using the Praxis package. In this process, the rate constants for channel opening and closing were constrained to values close to those reported by Robert & Howe (2003) for GLUR4, which were experimentally estimated from open times and burst length distributions. A fit was first obtained for mEPSCs at 25°C and then a further fit to the same mEPSC at 35°C was achieved by fitting a single multiplicative factor.

Results

Temperature effects on mEPSCs at the calyx of Held

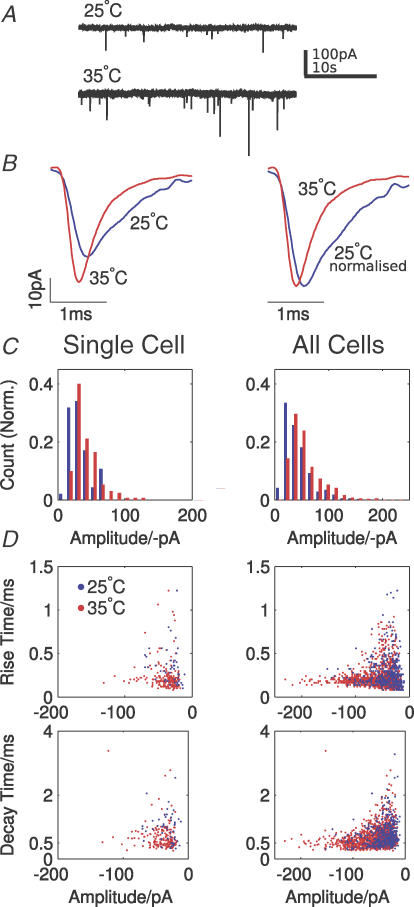

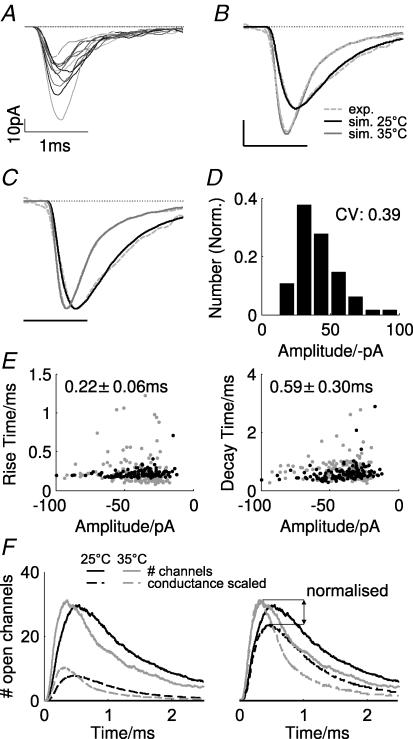

The temperature dependence of postsynaptic AMPARs was assessed using spontaneous mEPSCs recorded from MNTB principal neurons at 25°C and 35°C in the presence of TTX (0.5 μm) (Fig. 1A and B). Neurons were left for 10 min to allow for equilibration of temperature to the new value. Mean amplitude, decay time constants (single exponential) and frequencies of mEPSCs were calculated from averages of at least 40 events at each temperature in each of six neurons. In these cells, mEPSC mean amplitudes increased by 40 ± 14% (25°C, −33 ± 2.3 pA; 35°C, −46 ± 5.7 pA) and mean frequency increased by 440 ± 175% (25°C, 0.1 ± 0.02 Hz; 35°C, 0.47 ± 0.19 Hz). The mEPSCs also had a faster time course at higher temperature; with 10–90% rise time and decay time constant (single exponential) accelerating by 15 ± 8% (25°C, 0.25 ± 0.02 ms; 35°C, 0.21 ± 0.01 ms) and 34 ± 7% (25°C, 0.51 ± 0.06 ms; 35°C, 0.32 ± 0.02 ms), respectively (Fig. 1B). All changes in amplitude and decay time constant were significant (P < 0.05, paired t test); however, frequency distributions were not Gaussian (P < 0.05, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test) but a Wilcoxon signed rank non-parametric test showed that the increase in frequency with temperature was significant (P = 0.0313).

Figure 1. mEPSCs show changes in amplitude, time course and frequency on changing temperature from 25°C to 35°C.

mEPSCs were recorded from MNTB neurons under voltage clamp in the presence of TTX. A, representative traces showing raised mEPSC frequency at 35°C (traces taken from the same cell). B, averaged mEPSCs (left) and normalized mEPSCs (right) from one cell at 25°C (blue traces, average of 53 events) and 35°C (red traces, average of 312 events) showing a clear increase in amplitude after the 10°C temperature rise. A slower 10–90% rise time and decay time constant can clearly be seen at the lower temperature (note earlier peak amplitude in the normalized trace at 35°C). C, normalized amplitude histogram of mEPSCs recorded from one MNTB neuron at two temperatures (left histogram: 47 events at 25°C, blue bars; 170 events at 35°C, red bars) and of events pooled from six MNTB neurons (right histogram: 236 events at 25°C; 1266 events at 35°C). Both distributions exhibit more larger amplitude events and fewer undetectable small events at 35°C. The modal amplitude values in both plots are 25 pA at 25°C and 35 pA at 35°C. D, scatter plots of the 10–90% rise time (top) and decay time constant (single exponential, bottom) as a function of mEPSC amplitude. The left column shows data for the single cell (as in A,B,C, left) while the right shows pooled data from all cells (as in C, right) blue dots show values pooled from all neurons, and red dots show the subset for a single cell (same cell as in B and C, left).

Histograms of mEPSC amplitudes were constructed for events in a single cell and across the population of neurons (Fig. 1C). The amplitude distributions were similar and showed a rightward shift with increased temperature. Coefficients of variation (CV; after subtraction of recording noise) were similar for both temperatures. At 25°C, the histograms indicate some events smaller than −15 pA merging into noise, with fewer events being lost at higher temperatures. Distributions for 10–90% rise time and decay time constant significantly decreased with temperature (P < 0.002, paired t test; Fig. 1D). There was a strong tendency towards increasing variance of both these parameters with decreasing mEPSC amplitude, such that no apparent correlation existed between either 10–90% rise time or decay time constant and mEPSC amplitude.

Simulation of mEPSCs at 25°C

Monte Carlo simulation of vesicular glutamate release, diffusion and AMPAR gating was used to model mEPSCs at the calyx of Held. The geometric layout of the simulation is shown in Fig. 2A and kinetic parameters are summarized in Table 1. A vesicle is placed above the presynaptic membrane and release is initiated by opening of a pore that allows diffusion into the cleft. Diffusing glutamate binds to AMPARs embedded in the PSDs. The model included five PSDs, and the vesicle was placed at random locations within a radius of 200 nm relative to the central PSD (see Methods). Neighbouring PSDs were included to account for neurotransmitter spill-over (Neher & Sakaba, 2001); vesicle fusion never occurred at these locations.

Figure 2. Monte Carlo simulation reproduces time course and variability of mEPSCs at 25°C.

A, top view (left panel) and cross-section (right panel) of the three-dimensional synaptic geometry used in the simulations. The cross-section depicts the spatial relationships between pre- and postsynaptic membrane and a single vesicle fused to the presynaptic membrane. The right panel shows the arrangement of five postsynaptic densities (PSDs, dark grey regions), each containing 80 AMPARs (varied in some simulations). In all simulations, the vesicle was placed at different locations (semi-random in constant steps with equal probability across the whole area) over the central PSD. The yellow square illustrates the relative size of a vesicle. B, individual simulated mEPSCs (left panel) and the average of 155 individual realizations (right panel, blue trace shows the experimentally recorded mEPSC shown in Fig. 1B, left). C, average number of open channels (red trace), open channels scaled by conductance level (maroon trace), channels with bound agonist molecules (orange trace) and desensitized channels (blue trace) during a mEPSC (averages of 155 events). Total number of channels in the simulation was 400. D, normalized amplitude histogram of simulated mEPSCs. E, scatter plots of the 10–90% rise (left) and decay time (right, single exponential) as a function of mEPSC amplitude. Blue dots in panels show experimental data from the cell in the left panel in Fig. 1B, and mean values for rise and decay time are given in the respective plot.

We first fitted the time course of average mEPSCs to the recordings from a single cell at 25°C (cell shown in Fig. 1B). To prevent over-fitting due to the large number of states and transition rates in the kinetic scheme for AMPARs, the following constraints were imposed on the model. First, the rates into and out of desensitization were fixed such that a prolonged application of ligand molecules led to fast (see Fig. 3E) and near complete termination of the current (Sahara & Takahashi, 2001). Second, the channel opening and closing rates were fixed to those estimated by Robert & Howe (2003) for GLUR4 subunits. This left the binding and unbinding rates between closed and desensitized states as open parameters. Because mEPSCs are caused by rapid, short glutamate concentration transients, the effect of changing binding and unbinding rates between desensitized states had no influence on the response. Therefore, these rates were set equal to those for closed states.

Simulated mEPSCs were averages from at least 155 individual realizations of a single release process. The comparison between an averaged simulated and recorded mEPSC shows that this model can produce a very accurate fit of the time course of a typical mEPSC at the calyx of Held (Fig. 2B, right). The amplitude of the simulated mEPSC depends on the number of open channels, each weighted by the conductance state assigned to its respective agonist occupancy (calculated by weighting each open channel by its relative conductance level, compare Fig. 2C, red and purple trace). Consistent with experimental data (Ishikawa et al. 2002), the AMPAR population (a total of 400 channels) during a single simulated vesicle is not saturated (Fig. 2C, orange trace; a total of about 80/400 channels enter bound states, of these 40 channels are located in the central PSD). Desensitization occurs in approximately half of the available channels in the central PSD, and about 20% of the channels of the neighbouring PSDs (Fig. 2C, blue line).

Exploiting Monte Carlo simulation techniques, we also investigated the variability of postsynaptic responses due to the stochasticity of diffusion and channel gating. The peak amplitude of individual mEPSCs is highly variable (range, −11 to −69 pA; CV, 0.33; Fig. 2D), and is, as observed experimentally, strongly skewed (skewness, 0.71). The distribution of 10–90% rise and decay time constants closely matches the experimentally observed values and dependence of variance on peak amplitude (Fig. 2E). This indicates that the sources of variability included in these simulations (stochasticity of diffusion and ligand–receptor interactions and variable vesicle placement) can account for almost all of the variability in experimental single-cell data.

In addition randomly, varying the number of receptors at each PSD in each realization (drawn from a gaussian distribution with mean 80 receptors and S.D. 16 receptors) could fully reproduce the experimentally observed variability (CV, 0.39; skewness, 1.1; data not shown), as could keeping the number of receptors fixed while not restricting vesicle location to the area above the PSD (CV, 0.38; skewness, 0.8; data not shown).

Cooperative binding and variable vesicle location can explain mEPSC variability

As suggested by the results above, variability in the vesicle location may be the origin of the variability of mEPSCs recorded at the calyx of Held. The simulations show that the vesicle location relative to a PSD strongly influences the concentration of glutamate ‘seen’ by the AMPARs: moving the vesicle away from the centre of the PSD decreases the concentration significantly while increasing the amount of spill-over glutamate to neighbouring PSDs (Fig. 3A). However, the spill-over glutamate concentration peaks less rapidly compared to that at the central PSD (compare left and right panels in Fig. 3A), such that the rising phase of a mEPSC mainly depends on the time course of the glutamate concentration over the central PSD.

Vesicle location has a strong effect on the AMPAR response, while the number of channels with one or more bound glutamate molecules does not strongly depend on vesicle location (Fig. 3B). Release further from the PSD centre leads to fewer glutamate molecules binding and receptor opening to lower conducting states (Fig. 3C). This gives a substantial reduction (∼66%) of the average current from a release 200 nm away compared to a central release (Fig. 3D) and can explain the variability of mEPSC peak responses. Note that assuming a completely random vesicle location within a certain area makes releases at or near the centre of a PSD less likely than in the periphery, which in turn increases the likelihood of small amplitude mEPSCs. This could be a simple explanation for the strongly skewed amplitude histograms found experimentally (Fig. 1C).

The effect of vesicle location strongly depends on cooperative binding of glutamate in the AMPAR model, and is responsible for the steep dose–response relationship required for the variability caused by an approximately 10-fold agonist concentration difference (Fig. 3A). Simulating AMPAR currents generated by a constant concentration of glutamate shows that the peak amplitude varies more strongly for the cooperative binding model, compared to a model assuming independent binding (Fig. 3E and F). In both cases, rate constants for binding and unbinding were adjusted to fit the average mEPSC, subject to the constraints outlined above. It was noted that for the independent model, no alternatives could provide a similar fit while simultaneously producing a steeper dose–response relationship. We also note that in the cooperative binding model the 10–90% rise time varied more strongly in the range 0.1–1 mm (Fig. 3E), which explains the good fit of the mEPSC rise time distribution (Fig. 2E) and is consistent with experimental evidence obtained in CA1 pyramidal cells (Andrasfalvy & Magee, 2001). An independent binding model failed to reproduce the dependency of rise and decay time variability as a function of the mEPSC peak amplitude (data not shown). We conclude therefore that in the context of the assumptions made here, a cooperative binding model for AMPARs is necessary to explain the different aspects of mEPSC variability at the calyx of Held.

Acceleration of AMPAR kinetics underlies temperature dependency of mEPSCs

We next used Monte Carlo simulations to distinguish between three plausible mechanisms that could contribute to the larger and faster synaptic responses at increased temperature: (1) faster presynaptic vesicle fusion and neurotransmitter release; (2) faster glutamate diffusion in the synaptic cleft; or (3) accelerated molecular kinetics of postsynaptic AMPARs.

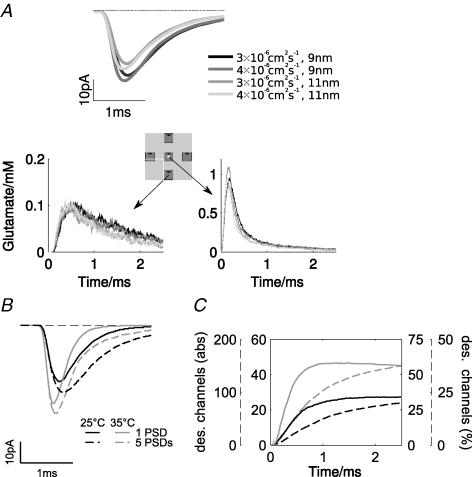

A temperature-dependent acceleration of AMPAR reaction kinetics was the only mechanism required for successful reproduction of the experimental data. Starting from the fit of mEPSCs at 25°C, a multiplication of all rate constants with a constant factor (Q10 = 2.4) was the only modification necessary to simulate faster mEPSCs with increased amplitude and to fit the average mEPSC successfully at 35°C from the same cell (Fig. 4A–C). Again assuming a variable number of receptors at each PSD (see Methods), the response variability is comparable to the experimental results for a single cell (Fig. 4D, compare with Fig. 1C). Both rise and decay time distributions are similar to those obtained experimentally and show the same trend of decreasing variability with increasing mEPSC peak amplitude (Fig. 4E).

Figure 4. Simulation of temperature effects on mEPSC kinetics at the calyx of Held model.

A, individual simulated mEPSCs at 35°C. B, simulated mEPSCs for 25°C (black trace) and 35°C (grey trace). Also shown are the experimental mEPSCs (mean from one cell) at both temperatures (dashed traces). C, the same data as in B, normalized to peak amplitude. D, amplitude histogram for simulated mEPSCs at 35°C. E, scatter plots of rise (left) and decay times (right) as a function of mEPSC peak amplitude. Grey dots in panels show experimental data from the cell in the left panel in Fig. 1B, and mean values for rise and decay time are given. F, number of open channels during a mEPSC at 25°C (black traces) and 35°C (grey traces). The left plot shows the absolute channel number (continuous lines) and the same scaled by their respective conductance (dashed lines, peak conductance set to unity). The right plot shows the same data with the conductance-scaled counts (dashed lines) rescaled to the peak of the absolute counts at 35°C. The arrow indicates the difference of the conductance-scaled counts at 25°C and 35°C.

AMPARs are driven into higher conducting states at physiological temperature

The kinetic AMPAR model was constructed to reflect the physical and physiological properties of neuronal AMPARs, including multiple subconductance states. This level of detail allowed us to assess the influence of the increased rate constants with temperature, and to refine and predict a more general model for temperature-related changes in synaptic transmission.

The continuous lines in the left panel of Fig. 4F show the average number of open channels during the mEPSC time course at 25°C and 35°C. The acceleration of receptor kinetics with temperature is indicated by the faster rise time of the grey (35°C) in comparison with the black (25°C) traces. The associated relative conductance generated by the open channels is shown by the dashed lines (open channels weighted by their relative conductance level). The small magnitude of this conductance indicates that many receptors are opening to low conductance states, therefore contributing little to the final current.

Although the total number of open channels is little affected by temperature (continuous lines in both panels of Fig. 4F), the relative conductances (dashed traces) differ substantially (i.e. the same number of receptors are open at both temperatures), but at 35°C a larger proportion are reaching a higher conductance state. This is clarified in the right panel of Fig. 4F, where conductance traces were re-scaled to the peak of the absolute number of open channels at 35°C. Hence the larger proportion of AMPARs driven to high conductance states generates more current at higher temperatures, as shown by the larger amplitude of the dashed grey trace (35°C) in comparison to the dashed black trace (25°C) (Fig. 4). The larger current is a sole consequence of faster binding at high temperature, as receptor affinity is unchanged and these open states are visited for shorter periods so generating rapid decays. Overall this suggests that at subphysiological temperatures a substantial population of AMPARs bind glutamate but remain ‘silent’, contributing little to the postsynaptic current. Note that this conclusion is not only valid for the specific set parameters considered here, as any increase in kB (required to account for faster rise times at higher temperature) will lead to a higher probability of entering higher conductance states.

The model predicts that the average channel conductance of AMPARs should change with temperature. This prediction was tested by investigating the relationship between the variance and mean of mEPSCs. For binomially distributed data, this relation is σ2 = Nq2p(1−p), where σ2 is the variance, N the number of channels, q the mean channel conductance and p its open probability. Using the relation I = Npq, where I is the mean current, we obtain σ2/I = q(1−p). Hence, if we assume a constant p (i.e. unaltered affinity of the AMPARs), an increase of σ2/I with temperature would indicate an increase in q.

This quantity can be measured directly for the experimental and simulated mEPSCs at the peak of the response. We did not pursue a full non-stationary variance-mean analysis (Sahara & Takahashi, 2001) because the simulations suggested that AMPARs desensitize during the course of a single mEPSC (see below) and therefore no reliable estimate of q is obtainable. For the cell shown in Fig. 3, we obtained σl2/Il = 6.53 × 10−12 pA (25°C) and σh2/Ih = 7.28 × 10−12 pA (35°C) giving a ratio (σh2Il)/(σl2Ih) = 1.23 (with the index l corresponding to 25°C, h to 35°C; variance due to recording noise was subtracted). The plausible explanation for this difference as predicted by the model is that mean unitary conductance of single AMPAR channels has increased with a rise in temperature. After pooling all mEPSCs recorded (389 events at 25°C and 1502 events at 35°C; paired recordings from six cells), we found σl2/Il = 1.35 × 10−12 pA, σh2/Ih = 1.69 × 10−12 pA giving a ratio (σh2Il)/(σl2Ih) = 1.25. For the simulated mEPSCs, the ratio was 1.25 (σl2/Il = 2.65 × 10−12 pA, σh2/Ih = 2.97 × 10−12 pA) without and 1.21 (σl2/Il = 4.53 × 10−12 pA, σh2/Ih = 5.47 × 10−12 pA) including variability in receptor number.

Hence in all three cases (single cell, pooled data and simulated responses), σ2/I increased when temperature was raised, confirming an increased unitary conductance of the AMPARs. Because not all sources of variability were considered, the absolute variance in the simulations is slightly lower than that found in experimental recordings. Nevertheless, the variance of the single-cell data and the simulated responses is in the same order of magnitude, indicating that the model contains the main sources of variability.

Influence of glutamate diffusion and spill-over on simulated mEPSCs

Using the model, we next examined temperature-dependent influences on glutamate release, diffusion and spill-over. With the Q10 of diffusion ∼1.3 in the synaptic cleft (Hille, 2001), only a small effect of temperature is expected. Temperature could also affect the vesicle fusion process. Therefore to assess the influence of these parameters in the model, the diffusion coefficient was increased by a factor of 1.33, and the maximal width of the pore from 9 to 11 nm (with a corresponding increase of 1.25 in opening velocity).

Increasing the diffusion coefficient leads to a slightly weaker glutamate transient (Fig. 5A) which decays faster, and this effect is also seen in the simulated mEPSC. A widening of the pore leads to a faster rise of the glutamate transient, which has a higher amplitude. Again, this behaviour is also visible in the simulated mEPSC (Fig. 5A). Combining both manipulations leads to a faster rise and decay, but also reduces the amplitude (Fig. 5A), which is not consistent with the experimental observation of faster rise and decay times and increased amplitude. Note also that all effects on the time course are much smaller than those observed experimentally with temperature. We therefore conclude that temperature-dependent changes in diffusion or exocytosis cannot account for the observed changes in experimental mEPSCs.

Figure 5. Influence of exocytosis and diffusion on transmission in the calyx of Held model.

A, (upper panel) simulated glutamate transients during release of the contents of a single vesicle, describing two different diffusion coefficients (3 × 10−6 and 4 × 10−6 cm2 s−1) and two maximal pore openings (9 and 11 nm). Lower panels show that cleft glutamate concentration time course is little influenced by vesicle location, in contrast to the receptor open probability (cf. Fig. 3A). Results are shown for a neighbouring PSD (left) and the central PSD (right). B, simulated mEPSCs at 25°C (black) and 35°C (grey) with (dashed lines) and without (solid lines) the influence of glutamate spill-over. C, numbers (left axes) and relative fractions (right axes) of AMPARs in a desensitized state at 25°C (black) and 35°C (grey), with (dashed lines, dashed axes) and without (continuous lines, continuous axes) the influence of glutamate spill-over.

Figure 5A also shows the glutamate spill-over transients at neighbouring PSDs, and the simulations suggest that the amplitude and rise of the spill-over transient is little affected by diffusion and exocytosis, while the decay shows a weak dependence on the diffusion coefficient (note that spill-over transients will be stronger for releases not centred above the PSD, see Fig. 3A). Thus spill-over will contribute both to the response and desensitization during an mEPSC. Comparing simulations where all PSDs were populated with AMPARs with those where only the central PSD was populated shows that glutamate spill-over contributes to the peak and decay phase of mEPSCs (Fig. 5B, compare solid and dashed traces). The relative influence of glutamate spill-over is similar at both 25°C and 35°C (Fig. 5B, compare continuous and dashed traces) reflecting some channel opening in neighbouring PSDs. However, the number of open channels remains similar at both temperatures, further implying little temperature-dependent spill-over (Fig. 4F).

In addition, spill-over leads to desensitization of AMPARs at neighbouring PSDs (Fig. 5C). At higher temperatures, more channels desensitize during a single mEPSC (Fig. 5C, compare black and grey traces), which results from an accelerated entry into desensitized states. The relative increase in the number of receptors entering desensitized states on raising temperature is, however, substantially smaller for the sites affected by spill-over transmitter than for the central PSD (compare the two continuous and dashed traces in Fig. 5C; note that a different scale applies to each pair). This suggests that at subphysiological temperatures, the relative contribution of spill-over to desensitization is stronger than at 37°C, as has been observed experimentally at the calyx of Held (Wong et al. 2003; Renden et al. 2005).

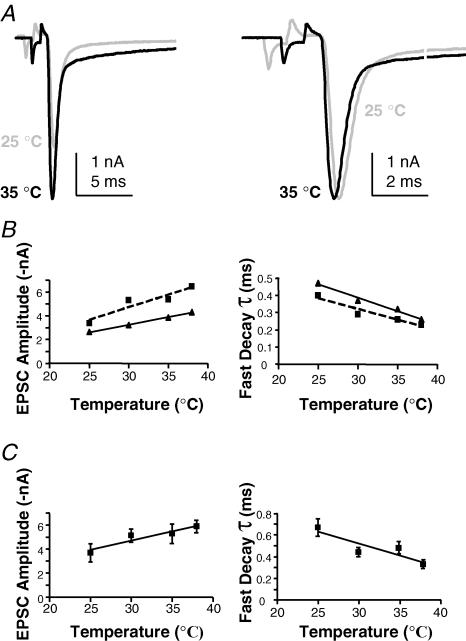

Effects of temperature on evoked EPSCs in the calyx of Held

The effect of changing temperature was measured on evoked EPSCs at a holding potential of −60 mV, by electrical stimulation of the trapezoid body fibres. Mean EPSC amplitude, decay time constants (fitted with fast and slow exponentials), 10–90% rise times and latency were calculated from averages of at least 10 events (evoked at 0.2 Hz). Two groups of recordings were obtained: data where the temperature was varied between 25°C and 35°C, or between 30°C and 38°C (allowing 10 min for the temperature to stabilize at the new value). Temperature changes caused considerable movement of the tissue, so multiple temperature changes in the same neuron were difficult to achieve routinely; nevertheless, data from two neurons included recordings from the full temperature range, as shown by the graphs in Fig. 6B. It should be noted that in both of these cells, temperature changes followed the sequence 30°C, 38°C, 35°C and down to 25°C, illustrating that the changes were reversible. For each of the parameters (amplitude, fast decay and latency), a linear trend was observed, similar to the averaged population data shown in Fig. 6C (n = 6–9). At 25°C, mean EPSC amplitude was −3.14 ± 0.59 nA, 10–90% rise time was 0.33 ± 0.002 ms, fast decay time constant was 0.75 ± 0.09 ms, slow decay time constant was 6.39 ± 0.85 ms (relative contribution, 15.3 ± 2.0%) with the EPSC having a latency (measured from stimulus artefact to EPSC onset) of 1.2 ± 0.21 ms (n = 6). On raising temperature to 35°C, EPSC amplitude increased by 34 ± 2.7% to −4.15 ± 0.73 nA, 10–90% rise time decreased by 23.1 ± 5.5% to 0.28 ± 0.02 ms, fast decay time constant accelerated by 26.5 ± 3.0% to 0.56 ± 0.08 ms, slow time constant accelerated by 24.0 ± 4.0% to 4.85 ± 0.71 ms and latency decreased by 38.7 ± 5.9% to 0.73 ± 0.07 ms. All changes were significant (P < 0.01, n = 6, paired t test) and reversible upon returning to 25°C. Changing from 30°C to 38°C also caused reversible and significant changes in the EPSC: amplitude (increased by 33.3 ± 12% from 4.56 ± 0.38 to −6.11 ± 0.51 nA), fast time constant (decreased by 22 ± 5.2% from 0.46 ± 0.06 to 0.32 ± 0.04 ms), 10–90% rise time (decreased by 13.1 ± 3.6% from 0.27 ± 0.03 to 0.23 ± 0.02 ms) and latency (decreased by 25.5 ± 3.6% from 0.81 ± 0.15 to 0.62 ± 0.15 ms; all P < 0.05 paired t test, n = 6). Slow decay time constant (representing 14.3 ± 1.3% of decay) decreased by 13.8 ± 4.4% from 4.74 ± 1.14 to 3.88 ± 0.74 ms, but this was not significant (P > 0.05 paired t test).

Figure 6. Evoked EPSCs show linear changes in amplitude, kinetics and latency with increasing temperature from 25°C to 38°C.

A, traces obtained from a single cell at both 25°C and 35°C. EPSC amplitude (average of 10 traces at 0.2 Hz) clearly increases with increasing temperature (left panel; note stimulus artifact preceeding the EPSC onset included to demonstrate latency change). EPSC traces were matched at the initiation point to demonstrate latency decreasing with temperature, and evoked EPSCs becoming faster. Right panel shows the traces with the EPSC at 25°C normalized to the amplitude of the higher temperature trace (again matched to initiation point). This clearly demonstrates the slower time course and delayed peak at the lower temperature. B, graphs depicting changes in EPSC amplitude and decay kinetics with increasing temperature for two individual neurons (values taken from average of 10 traces at 0.2 Hz). Left panel shows the linear trend of increasing amplitude with higher temperature (▴, cell 1, continuous line; ▪, cell 2, dashed line). In the same neurons (right panel) there was a linear decrease of EPSC fast decay time constant with increasing temperature. In both cells, temperature variation followed the pattern 30°C to 38°C, then to 35°C and finally 25°C, illustrating the reversibility of the temperature changes. C, pooled data from all neurons show similar trends with increasing temperatures measured at 25°C (n = 8), 30°C (n = 9), 35°C (n = 9) and 38°C (n = 6). EPSC amplitude (left panel) increases at higher temperatures while fast decay time constant (right panel) decreases in a linear fashion with increasing temperature.

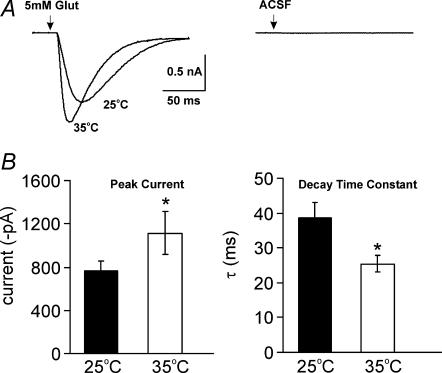

Temperature-dependent effects on glutamate-evoked currents

In order to confirm the postsynaptic site of action, we tested the AMPAR response to applied glutamate at different temperatures in the same cells. Glutamate was pressure ejected (5 mm, 3 ms) using a Picospritzer III onto individual neurons and the responses recorded at 25°C and 35°C, in the presence of 0.5 μm TTX and 2 mm kynurenate, to block voltage-gated sodium channels and minimize extra-synaptic receptor activation and AMPAR desensitization, respectively (Wong et al. 2003). Direct application of glutamate at 25°C gave a mean current of −0.76 ± 0.10 nA, increasing to −1.11 ± 0.19 nA at 35°C (Fig. 7B, left panel; P < 0.05, n = 7 paired t test). The decay time constant (single exponential) of the responses evoked by a single glutamate puff accelerated from 38.7 ± 4.3 ms at 25°C to 25.4 ± 2.4 ms at 35°C (Fig. 7B, right panel; P < 0.05, paired t test, n = 7). These AMPAR currents were blocked by bath application of 10 μm DNQX (n = 3) and application of aCSF alone induced no postsynaptic response (Fig. 7A, right panel; n = 3).

Figure 7. Postsynaptic AMPAR currents evoked by direct glutamate application also increase with raised temperature.

Pressure application of glutamate (5 mm) produced consistently large inward currents in MNTB neurons held at −60 mV (in the presence of 0.5 μm TTX and 2 mm kynurenate). A, representative traces for 25°C and 35°C showing increased current amplitude and faster kinetics at 35°C. B, pressure application of aCSF alone under the same conditions produced no response. C and D, summarize paired data from seven cells for peak amplitudes (C) and decay time constant (D) at 25°C and 35°C (*P < 0.05, paired t test).

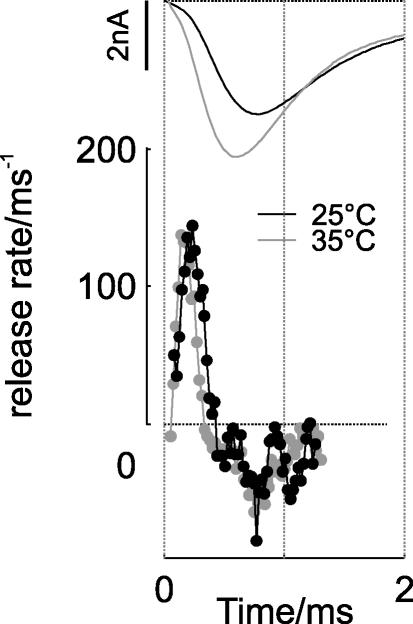

Temperature-dependent effects on evoked EPSCs are postsynaptic

It was previously demonstrated that temperature has little effect on quantal content of single evoked responses at the calyx of Held (Kushmerick et al. 2006). Our modelling studies indicate that temperature-dependent changes in mEPSCs are due to postsynaptic effects on receptor kinetics. Using a simple deconvolution analysis to estimate the quantal content of evoked EPSCs (e.g. Cohen et al. 1981; Borges et al. 1995), we confirm that temperature change has little influence on quantal content.

The deconvolution analysis was carried out using the averages of evoked responses and mEPSCs at 25°C and 35°C (upper traces in Fig. 8). The release rates obtained by deconvolution show a positive transient followed by negative undershoot (lower traces in Fig. 8). Negative release rates reflect the fact that the assumption of linear quantal summation is not sufficient for the calyx of Held, because desensitization and glutamate spillover both influence the late part of the response (Neher & Sakaba, 2001). The release rates at both temperatures show great similarity (lower traces in Fig. 8) with both cases exhibiting peak release rates of ∼140 ms−1. This is qualitatively consistent with earlier estimates at room temperature (Borst & Sakmann, 1996; Meyer et al. 2001). As expected, the release time course is slightly faster at 35°C, which may be a consequence of the faster presynatic Ca2+ currents at increased temperature (Helmchen et al. 1997; Borst & Sakmann, 1998).

Figure 8. Deconvolution analysis of evoked EPSCs at 25°C and 35°C indicates similar quantal content at each temperature.

The contribution of individual mEPSCs to the average shape of evoked EPSCs (top traces, six cells and 60 events each at 25°C (black) and at 35°C (grey)) was estimated by deconvolving them with the average, zero-padded mEPSCs at each temperature (six cells and 389 events at 25°C; six cells and 1502 events at 35°C). The resulting estimated release rate is shown in the bottom traces.

In conclusion, our combined experimental and modelling studies show that temperature-dependent changes in single evoked EPSCs are predominantly mediated by a postsynaptic mechanism, supporting the hypothesis that the influence of temperature on synaptic transmission is due to acceleration of AMPAR kinetics.

Discussion

In the present study, we examined the influence of temperature on synaptic transmission for miniature and evoked EPSCs at the calyx of Held. We found a systematic amplitude increase and acceleration of EPSC kinetics with raised temperature. These data were compared with Monte Carlo simulations and lead to the following conclusions. First, temperature-dependent changes in amplitude and mEPSC time course can be explained by accelerated agonist binding, unbinding and kinetics of AMPAR channel gating. It was sufficient to assume a single factor that equally affects all transition rates between different AMPAR states. Their accelerated kinetics drives AMPARs into higher conducting states while simultaneously speeding the response. Second, evoked responses exhibited very similar temperature-dependent behaviour to MEPSCs, while the glutamate puffing experiment and deconvolution analysis confirmed a postsynaptic site of action.

mEPSCs at the calyx of Held

Experimental mEPSCs showed variable amplitudes, with similar skewed amplitude distributions for both single cells and populations of neurons (Fig. 1). Averaged mEPSCs were similar in amplitude and time course to previous reports (Ishikawa et al. 2002; Habets & Borst, 2005) at room temperature. There was a significant increase in mean mEPSC amplitudes and acceleration in their time course with increasing temperature, in agreement with Kushmerick et al. (2006).

These changes could stem from multiple pre- or postsynaptic mechanisms. For instance, increased filling of vesicles at room temperature increases mEPSC amplitude (Ishikawa et al. 2002). Our simulations show that this increase only scales linearly with vesicle content, with no effect on rise or decay time (data not shown, see also Franks et al. 2003; Raghavachari & Lisman, 2004), but substantially increases the number of AMPAR channels entering desensitized states. Hence vesicle filling can be excluded as a major influence on synaptic time course, as it cannot explain the changed mEPSC kinetics, and as desensitization has been shown not to increase disproportionately with temperature (Kushmerick et al. 2006).

Other factors include the release mechanism (fusion pore formation and/or kinetics), glutamate diffusion across the cleft and postsynaptic AMPAR kinetics. The simulations demonstrate that increasing the diffusion coefficient led to faster but smaller responses, and that speeding exocytosis increases rise times and amplitudes (see also Stiles et al. 1996). These results illustrate that opening of the fusion pore (and not the reaction kinetics associated with state transitions in the AMPARs) limits the slope of the rise time of mEPSCs (Fig. 5A). When both velocity of diffusion and exocytosis are increased to reflect plausible temperature-dependent changes, the changes in mEPSC kinetics were far smaller than those observed experimentally, and when combined they lead to a decrease in amplitude (Fig. 5A). As this behaviour is inconsistent with the experimental results, we excluded an acceleration of diffusion and exocytosis as the primary cause of the temperature dependence of mEPSCs. It should be noted that the smallest rise times of simulated mEPSCs at 35°C are slightly larger than those obtained experimentally (Fig. 4D), indicating that exocytosis may indeed be accelerated, albeit with minor effects on mEPSC kinetics and amplitude.

Conversely, an acceleration of AMPAR reaction kinetics, leading to channel conductance changes (increased activation of higher-conducting open states) was sufficient to reproduce all temperature-dependent changes observed for mEPSCs (Fig. 4). This result is consistent with the glutamate puffing experiments demonstrating that robust changes in EPSC amplitude and kinetics can be observed even when all presynaptic release mechanisms are excluded (Fig. 7). In particular, scaling of all transition rate constants by a single factor could account for all observed mEPSC changes, with reaction rates of glutamate binding and unbinding (kB and kU) effectively adjusting kinetics and amplitude of the response. Scaling the other reaction rates (kO, kC and kD) by different amounts in a certain range also allowed successful fits, but only when the binding and unbinding rates were adjusted accordingly. It was not possible to distinguish between these different possibilities on the basis of the experimental data. A precise distinction between pre- and postsynaptic factors would then be possible by comparing Arrhenius plots for mEPSCs and glutamate puffing (cf. Stiles et al. 1999). These experiments are, however, impractical at the calyx of Held because of the limited available recording time.

Given that the multiple states in the kinetic scheme could have different activation energies, increasing all reaction rates by a single factor is just the simplest of many possible permutations which could explain the observed temperature-dependent changes. We tested whether modifying single rate constants or subgroups of rate constants could lead to similar effects. Changing only a single rate constant never accounted for the experimental data (i.e. it is possible to increase the current amplitude by increasing kB or kO), but this also increases rise or decay times, contrary to the mEPSC recordings. Changing both rates associated with channel opening and closing (kO and kC) allows for faster decay times, but with very little influence on either rise time or amplitude. Additionally, increasing entry into desensitization (kD) allows for either faster decay times or stronger currents, but they do not both change simultaneously (as in the experimental data).

Changing the rates associated only with glutamate binding (e.g. kB by a factor 4.7 and kU by 8.6) did allow fitting of both the larger amplitude and faster kinetics at high temperature. The importance of this is that mEPSC rise time essentially depends on the ratio of kB and kU (setting a lower boundary to the value of kB) and that these parameters strongly affect the current amplitude by determining which conductance levels are accessible. Hence different combinations of kB and kU allow for successful fits when the other rate constants were changed accordingly (with kO and kC being overall less sensitive to changes than kD). This simple case of scaling all rate constants with a single factor, whereby the rates of glutamate binding and unbinding, kB and kU, effectively adjust kinetics and amplitude of the response, represents a fair approximation of the experimental data. Thus the evidence strongly indicates that the increased mEPSC amplitude is mediated by increased occupancy of higher subconductance levels (which are more accessible at higher temperature) rather than a general increase in magnitude of the unitary conductance or subconductance levels. This is consistent with data showing that AMPAR channels have multiple conductance states, and that receptor occupancy determines the conductance (e.g. Swanson et al. 1997; Rosenmund et al. 1998; Smith & Howe, 2000; Smith et al. 2000; Morkve et al. 2002; Jin et al. 2003; Gebhardt & Cull-Candy, 2006). In contrast, attempts to reproduce the observed temperature-dependent effects on mEPSCs with models without multiple conductance levels (such as those derived by Raman & Trussell, 1992, 1995) consistently required adjustment of individual rate constants, as the affinity of open states (and hence the apparent affinity of the receptor) had to be strongly increased to account for the larger amplitudes at higher temperature. In testing the possibility that the increase in AMPAR conductance is due to changes in unitary conductance/subconductances, simulations indicate that even a modest (∼1.2-fold) uniform increase of the conductance would substantially increase the amplitude, but further modification of receptor gating would be required to achieve acceleration of the receptor kinetics. Indeed, increased mean channel conductance with temperature is also observed in nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) (Dilger et al. 1991) which (as for a number of other channel types such as potassium channels) also possess multiple conductance states (Colquhoun & Sakmann, 1985; Fox, 1987). Our results and modelling suggest that the observed conductance changes on raising temperature reflect the preferred opening of channels to higher conductance states. Thus, faster receptor kinetics is the primary effect of raising temperature (via increased agonist binding), pushing open channels into higher conductance levels.

Evoked EPSCs

In individual neurons where temperature was varied, evoked EPSCs varied in amplitude, 10–90% rise time, decay time constant (fast) and latency in linear fashions (Fig. 6). This pattern supports the idea that most of the temperature effects in this system are happening at the postsynaptic receptor level (because multifactorial mechanisms would be less likely to follow linear trends). Furthermore the current induced by direct application of glutamate (so bypassing the presynaptic release machinery) also increased in amplitude with increased temperature.

The latency decrease of evoked EPSCs indicated that presynaptic mechanisms are more efficient at higher temperatures. Change in stimulus-evoked synaptic responses with temperature using direct recordings from calyceal terminals is well documented, with the presynaptic action potential shortening (Borst et al. 1995) and calcium currents getting larger but quicker, leading to reduced calcium entry into the terminal during an action potential (Borst & Sakmann, 1998). Recently, Yang & Wang (2006) used the postsynaptic response as a measure of presynaptic transmitter release and interpreted the larger EPSC amplitude with temperature as indicating increased release. However, the maintained quantal content of evoked EPSCs observed by Kushmerick et al. (2006), combined with the postsynaptic changes in AMPARs with temperature (reported here), in fact supports a postsynaptic temperature-dependent mechanism. Further to this, the charge integral of evoked EPSCs remained relatively constant at the two temperatures, consistent with the interpretation that presynaptic changes (i.e. reduced calcium entry, but increased calcium coupling to release) mutually compensate during temperature changes so maintaining similar overall release probability for evoked events (Kushmerick et al. 2006). The increased mEPSC frequency observed with temperature could be consistent with increased presynaptic calcium coupling to exocytosis, but other evidence suggests that spontaneous and evoked release arise from different vesicle pools, such that mEPSC frequency can change without affecting evoked release (Sara et al. 2005).

Deconvolution indicated that the quantal content of an evoked EPSC remained similar at room or physiological temperature (Fig. 8). The experimental and modelling data in this study strongly suggest a mechanism where cooperative binding at the AMPAR is optimized at physiological temperatures and reduced at subphysiological temperatures, giving smaller and slower synaptic responses. This in turn is followed by less efficient unbinding, which accounts for the slower mEPSC decay at room temperature.

In the auditory brainstem, binaural comparison of microsecond timing differences carries information about sound localization (Grothe, 2003) and so requires extreme precision of action potential timing. It is clear that higher temperatures permit higher frequency transmission at the calyx of Held (Taschenberger & von Gersdorff, 2000) and other excitatory synapses (Saviane & Silver, 2006). The increased postsynaptic AMPAR response at higher temperatures makes synaptic transmission more secure with a higher safety factor, which in turn triggers a well-timed postsynaptic action potential. In a complimentary fashion, presynaptic increases in vesicle recycling reduce the impact of short-term depression during high-frequency stimulation (Pyott & Rosenmund, 2002; Kushmeric et al. 2006). A combination of these pre- and postsynaptic elements explains the underlying temperature dependence of synaptic transmission, and provides a theoretical basis for integrating experiments conducted at physiological and subphysiological temperatures.

Acknowledgments

Funded by the BBSRC and MRC.

References

- Andrasfalvy BK, Magee JC. Distance-dependent increase in AMPA receptor number in the dendrites of adult hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9151–9159. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-09151.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong N, Gouaux E. Mechanisms for activation and antagonism of an AMPA-sensitive glutamate receptor: crystal structures of the GluR2 ligand binding core. Neuron. 2000;28:165–181. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00094-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asztely F, Erdemli G, Kullmann DM. Extrasynaptic glutamate spillover in the hippocampus: dependence on temperature and the role of active glutamate uptake. Neuron. 1997;18:281–293. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80268-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes-Davies M, Forsythe ID. Pre- and postsynaptic glutamate receptors at a giant excitatory synapse in rat auditory brainstem slices. J Physiol. 1995;488:387–406. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billups B, Wong AC, Forsythe ID. Detecting synaptic connections in the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body using calcium imaging. Pflugers Arch. 2002;444:663–669. doi: 10.1007/s00424-002-0861-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges S, Gleason E, Turelli M, Wilson M. The kinetics of quantal transmitter release from retinal amacrine cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:6896–6900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.6896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borst JGG, Helmchen F, Sakmann B. Pre- and postsynaptic whole-cell recordings in the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body of the rat. J Physiol. 1995;489:825–840. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borst JGG, Sakmann B. Calcium influx and transmitter release in a fast CNS synapse. Nature. 1996;383:431–434. doi: 10.1038/383431a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borst JGG, Sakmann B. Calcium current during a single action potential in a large presynaptic terminal of the rat brainstem. J Physiol. 1998;506:143–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.143bx.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements J, Feltz A, Sahara Y, Westbrook G. Activation kinetics of AMPA receptor channels reveal the number of functional agonist binding sites. J Neurosci. 1998;18:119–127. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-01-00119.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements J, Lester R, Tong G, Jahr C, Westbrook G. The time course of glutamate in the synaptic cleft. Science. 1992;258:1498–1501. doi: 10.1126/science.1359647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen I, van der Kloot W, Attwell D. The timing of channel opening during miniature end-plate currents. Brain Res. 1981;223:185–189. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)90821-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun D, Sakmann B. Fast events in single-channel currents activated by acetylcholine and its analogues at the frog muscle end-plate. J Physiol. 1985;369:501–557. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilger JP, Brett RS, Poppers DM, Liu Y. The temperature dependence of some kinetic and conductance properties of acetylcholine receptor channels. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1063:253–258. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(91)90379-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe ID. Direct patch recording from identified presynaptic terminals mediating glutamatergic EPSCs in the rat CNS, in vitro. J Physiol. 1994;479:381–387. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe ID, Barnes-Davies M. The Binaural auditory pathway: excitatory amino acid receptors mediate dual timecourse excitatory postsynaptic currents in the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1993b;251:151–157. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1993.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox JA. Ion channel subconductance states. J Membr Biol. 1987;97:1–8. doi: 10.1007/BF01869609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks KM, Stevens CF, Sejnowski TJ. Independent sources of quantal variability at single glutamatergic synapses. J Neurosci. 2003;23:3186–3195. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03186.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebhardt C, Cull-Candy SG. Influence of agonist concentration on AMPA and kainite channels in CA1 pyramidal cells in rat hippocampal slices. J Physiol. 2006;573:371–394. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.102723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grothe B. New roles for synaptic inhibition in sound localization. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:1–11. doi: 10.1038/nrn1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habets RLP, Borst JGG. Post-tetanic potentiation in the rat calyx of Held synapse. J Physiol. 2005;564:173–187. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.079160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmchen F, Borst JGG, Sakmann B. Calcium dynamics associated with a single action potential in a CNS presynaptic terminal. Biophys J. 1997;72:1458–1471. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78792-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. Ionic Channels of Excitable Membranes. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hines M, Carnevale N. The NEURON simulation environment. Neural Comput. 1997;9:1179–1209. doi: 10.1162/neco.1997.9.6.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines M, Carnevale N. Expanding NEURON's repertoire of mechanisms with NMODL. Neural Comput. 2000;12:995–1007. doi: 10.1162/089976600300015475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa T, Sahara Y, Takahashi T. A single packet of transmitter does not saturate postsynaptic glutamate receptors. Neuron. 2002;34:613–621. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00692-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin R, Banke T, Mayer M, Traynelis S, Gouaux E. Structural basis for partial agonist action at ionotropic glutamate receptors. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:803–810. doi: 10.1038/nn1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd FL, Isaac JTR. Kinetics and activation of postsynaptic kainate receptors at thalamocortical synapses: role of glutamate clearance. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86:1139–1148. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.3.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar PK, Clark M. Clinical Medicine. 5. Edinburgh: W.B. Saunders; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kushmerick C, Renden R, von Gersdorff H. Physiological temperatures reduce the rate of vesicle pool depletion and short-term depression via an acceleration of vesicle recruitment. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1366–1377. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3889-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longsworth LG. Diffusion measurements at 25° of aqueous solutions of amino acids, peptides and sugars. J Am Chem Soc. 1953;75:5705–5709. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer AC, Neher E, Schneggenburger R. Estimation of quantal size and number of functional active zones at the calyx of held synapse by nonstationary EPSC variance analysis. J Neurosci. 2001;21:7889–7900. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-20-07889.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micheva KV, Smith SJ. Strong effects of subphysiological temperature on the function and plasticity of mammalian presynaptic terminals. J Neurosci. 2005;25:7481–7488. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1801-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morkve SH, Veruki ML, Hartveit E. Functional characteristics of non-NMDA-type ionotropic glutamate receptor channels in AII amacrine cells in rat retina. J Physiol. 2002;542:147–165. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.020305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E, Sakaba T. Combining deconvolution and noise analysis for the estimation of transmitter release rates at the calyx of held. J Neurosci. 2001;21:444–461. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-02-00444.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyott SJ, Rosenmund C. The effects of temperature on vesicular supply and release in autaptic cultures of rat and mouse hippocampal neurons. J Physiol. 2002;539:523–535. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavachari S, Lisman JE. Properties of quantal transmission at CA1 synapses. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:2456–2467. doi: 10.1152/jn.00258.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raman I, Trussell L. The kinetics of the response to glutamate and kainate in neurons of the avian cochlear nucleus. Neuron. 1992;9:173–186. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90232-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raman I, Trussell L. The mechanism of alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionate receptor desensitization after removal of glutamate. Biophys J. 1995;68:137–146. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80168-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renden R, Taschenberger H, Puente N, Rusakov DA, Duvoison R, Wang LY, Lehre KP, von Gersdorff H. Glutamate transporter studies reveal the pruning of metabotropic glutamate receptors and absence of AMPA receptor desensitization at mature calyx of Held synapses. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8482–8497. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1848-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert A, Howe J. How AMPA receptor desensitization depends on receptor occupancy. J Neurosci. 2003;23:847–858. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-03-00847.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenmund C, Stern-Bach Y, Stevens C. The tetrameric structure of a glutamate receptor channel. Science. 1998;280:1596–1599. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5369.1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusakov DA, Kullmann DM. Extrasynaptic glutamate diffusion in the hippocampus: ultrastructural constraints, uptake, and receptor activation. J Neurosci. 1998;18:3158–3170. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-09-03158.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahara Y, Takahashi T. Quantal components of the excitatory postsynaptic currents at a rat central auditory synapse. J Physiol. 2001;536:189–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00189.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sara Y, Virmani T, Deák F, Liu X, Kavalali ET. An isolated pool of vesicles recycles at rest and drives spontaneous neurotransmission. Neuron. 2005;45:563–573. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sätzler K, Söhl L, Bollmann J, Borst J, Frotscher M, Sakmann B, Lübke J. Three-dimensional reconstruction of a calyx of Held and its postsynaptic principal neuron in the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10567–10579. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-24-10567.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saviane C, Silver RA. Fast vesicle reloading and a large pool sustain high bandwidth transmission at a central synapse. Nature. 2006;439:983–987. doi: 10.1038/nature04509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneggenburger R, Forsythe ID. The calyx of Held. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;326:311–337. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0272-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T, Howe J. Concentration-dependent substate behaviour of native AMPA receptors. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:992–997. doi: 10.1038/79931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T, Wang L, Howe J. Heterogeneous conductance levels of native AMPA receptors. J Neurosci. 2000;20:2073–2085. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-06-02073.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiles JR, Bartol TM. Monte Carlo methods for simulating realistic synaptic microphysiology using MCell. In: DeSchutter E, editor. Computational Neuroscience: Realistic Modelling for Experimentalists. New York: CRC Press; 2001. pp. 87–128. [Google Scholar]

- Stiles JR, Kovyazina IV, Salpeter EE, Salpeter MM. The temperature sensitivity of miniature currents is mostly by channel gating: evidence from optimized recordings and Monte Carlo simulations. Biophys J. 1999;77:1177–1187. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)76969-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiles J, Van Helden D, Bartol T, Salpeter E, Salpeter M. Miniature endplate current rise times less than 100 microseconds from improved dual recordings can be modelled with passive acetylcholine diffusion from a synaptic vesicle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:5747–5752. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Olson R, Horning M, Armstrong N, Mayer M, Gouaux E. Mechanism of glutamate receptor desensitization. Nature. 2002;417:245–253. doi: 10.1038/417245a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson G, Kamboj S, Cull-Candy S. Single-channel properties of recombinant AMPA receptors depend on RNA editing, splice variation, and subunit composition. J Neurosci. 1997;17:58–69. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-01-00058.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taschenberger H, von Gersdorff H. Fine-tuning an auditory synapse for speed and fidelity: developmental changes in presynaptic waveform, EPSC kinetics, and synaptic plasticity. J Neurosci. 2000;20:9162–9173. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-24-09162.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyklicky L, Patneau D, Mayer M. Modulation of excitatory synaptic transmission by drugs that reduce desensitization at AMPA/kainate receptors. Neuron. 1991;7:971–984. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90342-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong AY, Graham BP, Billups B, Forsythe ID. Distinguishing between presynaptic and postsynaptic mechanisms of short-term depression during action potential trains. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4868–4877. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-12-04868.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YM, Wang LY. Amplitude and kinetics of action potential-evoked Ca2+ current and its efficacy in triggering transmitter release at the developing calyx of held synapse. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5698–5708. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4889-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]