Abstract

The formation of germinal centers (GCs) represents a crucial step in the humoral immune response. Recent studies using gene-targeted mice have revealed that the cytokines tumor necrosis factor (TNF), lymphotoxin (LT) α, and LTβ, as well as their receptors TNF receptor p55 (TNFRp55) and LTβR play essential roles in the development of GCs. To establish in which cell types expression of LTβR, LTβ, and TNF is required for GC formation, LTβR−/−, LTβ−/−, TNF−/−, B cell–deficient (BCR−/−), and wild-type mice were used to generate reciprocal or mixed bone marrow (BM) chimeric mice. GCs, herein defined as peanut agglutinin–binding (PNA+) clusters of centroblasts/centrocytes in association with follicular dendritic cell (FDC) networks, were not detectable in LTβR−/− hosts after transfer of wild-type BM. In contrast, the GC reaction was restored in LTβ−/− hosts reconstituted with either wild-type or LTβR−/− BM. In BCR−/− recipients reconstituted with compound LTβ−/−/BCR−/− or TNF−/−/BCR−/− BM grafts, PNA+ cell clusters formed in splenic follicles, but associated FDC networks were strongly reduced or absent. Thus, development of splenic FDC networks depends on expression of LTβ and TNF by B lymphocytes and LTβR by radioresistant stromal cells.

Keywords: lymphotoxin, tumor necrosis factor, bone marrow transfer, follicular dendritic cell, germinal center

In the course of a humoral immune response, germinal centers (GCs)1 represent the microenvironment where antigen-specific B cells efficiently undergo clonal expansion, diversification of their Ig genes, selection for clones bearing B cell receptors (BCRs) of high affinity to the antigen, and differentiation into memory or plasma cells (for reviews, see references 1–3). To support the GC reaction, B cells, T cells, and follicular dendritic cells (FDCs), the three major cellular constituents of GCs, have to interact in an intricate way. In brief, FDCs trap and retain native antigen complexed with antibody and complement, and also provide contact-dependent antigen-nonspecific costimulatory signals that facilitate chemotaxis and proliferation of B cells (4, 5). It is believed that the trapped antigen can be best endocytosed by B cells with increased affinity of their BCRs to the antigen (4, 5). These B cells then present the processed antigen to CD4+ T cells, which on their part, together with FDCs, support further proliferation and differentiation of the selected B cells towards preplasma cells or memory B cells (4, 5).

Over the past few years, several members of the TNF/ lymphotoxin (LT) receptor and ligand families have been shown to play essential roles in the induction of GCs. Prominent members mediating this function are the TNFRp55, the LTβR, and their ligands TNF, LTα, and LTβ. Both LTα and TNF form homotrimers (6, 7) which signal via TNFRp55 and TNFRp75 (8, 9). LTα3 is only secreted by activated lymphocytes and NK cells (7), whereas TNF3 exists both in a membrane-bound and soluble form (10) and can be produced by many different cell types, including macrophages, T, and B cells (11–13). LTα can also associate with LTβ, a membrane-bound type II protein (14, 15). The LTα1β2 heterotrimer engages the LTβR, which is expressed on macrophages and in lymphoid and visceral tissues, but not on T or B lymphocytes (16–18). Mice deficient in TNFRp55, LTβR, TNF, or LTα all lack GCs, as defined by the absence of both peanut agglutinin–binding (PNA+) clusters of centroblasts/centrocytes and associated FDC networks in B cell areas (19–21). LTβ−/− mice differ in their phenotype in that some small PNA+ clusters are detectable in the B cell areas, but associated FDC networks are absent or strongly reduced (22–24). Expression of LTα and TNFRp55 by B cells and radioresistant stromal cells, respectively, was shown to be required for GC formation (25–29). However, no data concerning the cell lineages required to express LTβR, LTβ, and TNF for GC development are available.

This study demonstrates that engagement of the LTβR on radioresistant stromal cells is mandatory for creating an intact splenic microarchitecture, allowing T–B cell segregation and establishment of GCs. Moreover, for full development of splenic FDC networks, B lymphocytes are required to produce both LTβ and TNF.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

LTβ- and LTβR-deficient mice were generated as described previously (21, 22). BCR-deficient mice (30) and TCR β/δ–deficient mice (31) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Ly5.1+ C57BL/6 mice were supplied by Dr. H.R. Rodewald (Basel Institute for Immunology, Basel, Switzerland). TNF-deficient mice (19) were provided by Dr. G. Kollias (Hellenic Pasteur Institute, Athens, Greece). Mice were maintained and bred in a conventional mouse facility in isolated cages according to German guidelines for animal care. 8–12-wk-old mice were taken for experiments.

Bone Marrow Transfer.

Bone marrow (BM) cells were harvested by flushing femurs and tibias of donor mice with cold RPMI 1640 medium (Seromed) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FCS (Seromed), 2 mM l-glutamine (Seromed), 50 μM 2-ME (GIBCO BRL), 50 μg/ml streptomycin (Seromed), and 100 U/ml penicillin. Cells were washed and depleted of mature T cells using magnetic beads coated with anti-Thy1.2 mAb (Dynal) according to the manufacturer's protocol. After the depletion, cells were counted, washed, and resuspended in PBS. Recipient mice were irradiated with 9.5 Gy using a 137Cs irradiator (Buchler) and injected intravenously with 2 × 106 BM cells in 0.2 ml PBS. For mixed BM transfer, 1.5 × 106 cells of each genotype were injected in a total volume of 0.2 ml PBS.

Immunization.

6–8 wk after the BM transfer, the mice received an intraperitoneal injection of 5 μg of alum-precipitated (4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenyl-acetyl)-chicken gamma globulin (molar ratio 19:1; NP19-CG) in 0.2 ml PBS.

Evaluation of Chimerism.

10 d after immunization, mixed BM chimeric mice were killed, and BM, spleens, lymph nodes, and sera were collected. One half of each spleen was frozen for immunohistology, and the other half and all lymph nodes were used to purify B lymphocytes. Single cell suspensions were prepared using nylon cell strainers (Becton Dickinson). Cells were washed and incubated in Tris-buffered ammonium chloride solution to lyse erythrocytes. Cells were then washed in RPMI 1640 medium and in PBS containing 0.5% BSA. At this stage, chimerism of some mice was determined by flow cytometry on a FACScan®, using mAbs directed against the Ly5.1 (CD45.1) and Ly5.2 (CD45.2) isoforms conjugated to FITC or PE (PharMingen). B cells were purified by magnetic cell sorting using mouse CD45R (B220) microbeads, MACS® VS+ separation columns and a MACS® magnet (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer. The selected fractions were additionally depleted of remaining T cells by magnetic cell sorting using anti-Thy1.2–coated Dynabeads (Dynal). BM cells were depleted of T cells and of IgM+/IgG+ cells using a cocktail of Dynabeads coated with anti-Thy1.2 or anti-IgM/IgG antibodies (Dynal). The purity of cell populations was confirmed by flow cytometry. The percentage of LTβ−/− cells in the purified populations was determined by Southern blot hybridization of BamHI-digested genomic DNA using an SphI-PstI fragment of the murine LTβ promoter (nucleotides 2977–3411, sequence data available from EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ under accession no. U06950) as a probe. Similarly, the percentage of TNF−/− cells was determined by Southern blot hybridization of EcoRI- digested genomic DNA using a PCR-generated fragment of exon 4 of the TNF gene (PCR primers 5′-AGGTCACTGTCCCAGCATCT and 5′-GTCAGCCGATTTGCTATCTCA) as a probe. Quantifications of chimerism were performed by densitometry using a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics).

Immunohistochemistry.

Tissue samples were embedded in tissue-freezing medium (Leica) and snap-frozen in 2-methylbutane (Merck) prechilled by liquid nitrogen. Cryostat sections (7 μm) were fixed for 8 min in acetone (Merck), dried, and preincubated for 30 min with PBS containing 5% (vol/vol) goat serum, 1% (wt/vol) BSA, and 0.15% (vol/vol) hydrogen peroxide (Sigma). Blocking of endogenous biotin was performed using an avidin-biotin blocking kit (Vector) according to the manufacturer's protocol. For double labeling, sections were incubated for 30 min with (a) biotinylated PNA diluted 1:500 (Vector) and rat anti– mouse CR1 (CD35) diluted 1:100 (clone 8C12; PharMingen); (b) biotinylated PNA diluted 1:500 (Vector) and rat anti–mouse B220 diluted 1:100 (clone RA3-6B2; PharMingen); and (c) biotinylated mouse anti–mouse IgD diluted 1:50 (clone 1.3-5), rat anti–mouse CD4 diluted 1:100 (GK1.5; PharMingen), and rat anti–mouse CD8 used as a 1:2 diluted hybridoma supernatant (clone 53.6-72; American Type Culture Collection). Rat IgG2a and IgG2b (PharMingen) were used as isotype controls. Single labeling was performed with FDC-M1 mAb (clone 4C11). After washing, alkaline phosphatase (AP)-conjugated streptavidin (Sigma) and/or horseradish peroxidase–coupled mouse anti–rat IgG (Dianova) were added. After 30 min incubation and washing, color development for bound AP and horseradish peroxidase was consecutively performed with an AP reaction kit (Vector) according to the manufacturer's instructions and with 3-aminoethyl-carbazole (Sigma) as described (32). In addition, fluorescent microscopy was used for analysis of sections labeled with PNA and FDC-M2 mAb (clone 209) as described previously (25).

Measurement of Antigen-specific IgG.

10 d after immunization, NP-specific IgG antibodies were detected using sandwich ELISAs with NP12-BSA– or NP5-BSA–conjugated ELISA plates (10 μg/ml in carbonate buffer [pH 9.5]). Murine NP-specific IgG antibodies were detected with an AP-conjugated goat anti– mouse IgG antiserum (Dianova). The substrate used was p-nitrophenyl phosphate (Sigma). For calculation of arbitrary binding units of NP-specific IgG antibodies, the standard NP-reactive mAb, N1G9 (33), was included on each ELISA plate.

Results

GC Formation and Intact Splenic Architecture Require Expression of LTβR on Radioresistant Cells.

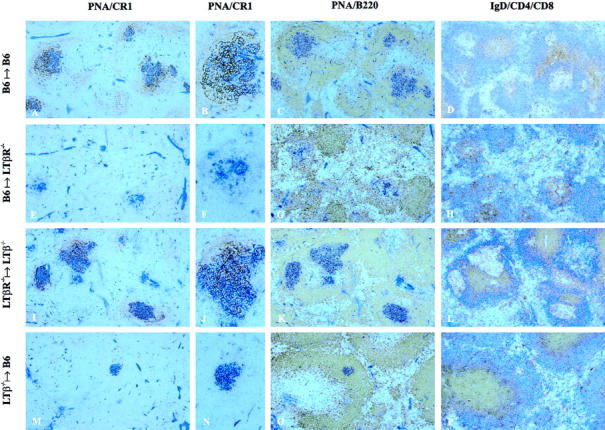

To address which cell types have to express LTβ or LTβR to initiate and maintain GC reactions, a reciprocal BM transplantation approach was used. BM from C57BL/6 wild-type donors was transferred into myeloablatively irradiated LTβR−/− recipients (B6 → LTβR−/−) and vice versa (LTβR−/− → B6). In the same manner, LTβR−/− → LTβ−/−, B6 → LTβ−/−, and LTβ−/− → B6 chimeric mice were generated. As a control, BM from C57BL/6 wild-type donors was taken to repopulate irradiated C57BL/6 wild-type recipients (B6 → B6). After 8 wk, mice were immunized intraperitoneally with 5 μg NP19-CG adsorbed to alum, and 10 d later spleens and sera were taken for analysis. For detection of GCs, a double labeling of spleen sections was performed using the plant lectin PNA and the mAb 8C12. PNA binds to centroblasts/centrocytes, whereas the mAb 8C12 is directed against the murine complement receptor CR1, which is highly expressed on FDCs and at lower levels by B lymphocytes (34). As shown in Fig. 1, E–H, in the spleens of B6 → LTβR−/− animals only a few, small PNA+ cell aggregates were observed, and FDC networks were completely absent. A similar phenotype was found in immunized LTβR−/− mice (21). An aliquot of the wild-type BM used to reconstitute the LTβR−/− recipients was also transferred into LTβ−/− recipients. In these mice, the wild-type BM-derived cells were capable of restoring GC formation, proving the intrinsic competence of the donor BM cells (data not shown). Morphologically intact GCs, i.e., PNA+ cell clusters in association with FDC networks, were also detectable in spleens from LTβR−/− → LTβ−/− (Fig. 1, I and J), LTβR−/− → B6 (data not shown), and B6 → B6 (Fig. 1, A and B) chimeras. In contrast, wild-type mice reconstituted with LTβ−/− BM had fewer and smaller PNA+ cell clusters with almost undetectable FDC networks (Fig. 1, M and N). Presence or absence of FDC networks in association with PNA+ cell clusters was confirmed by double labeling with PNA and FDC-M2 mAbs or by single labeling with FDC-M1 mAbs (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Splenic GC development in reciprocal BM chimeric mice. Irradiated recipients (n = 3–5 per group) were reconstituted with BM from donors as indicated. After 8 wk, chimeras were immunized intraperitoneally with 5 μg NP19-CG adsorbed to alum. 10 d later, chimeras were killed and splenic cryosections were labeled with anti-CR1 (brown) and PNA (blue); anti-B220 (brown) and PNA (blue); or anti-CD4 (brown), anti-CD8 (brown), and anti-IgD (blue).

The anatomical localization of GCs was determined by labeling splenic sections with either PNA and anti-B220 mAbs or anti-IgD, anti-CD4, and anti-CD8 mAbs. Downregulation of IgD on most GC B cells and relatively low numbers of T cells scattered in GCs compared with compact T cell areas in periarteriolar lymphoid sheaths served as criteria for the identification of GCs. In LTβR−/− → LTβ−/− (Fig. 1, K and L), LTβR−/− → B6 (data not shown), and B6 → B6 (Fig. 1, C and D) chimeric mice, all GCs were correctly localized in the B cell areas. Conversely, in spleens of LTβR−/− mice reconstituted with wild-type BM, PNA+ cell aggregates were found around central arterioles (Fig. 1, G and H). T and B cells segregated normally in LTβR−/− → LTβ−/− (Fig. 1 L), LTβR−/− → B6 (data not shown), and B6 → B6 (Fig. 1 D) chimeric mice, forming distinct periarteriolar lymphoid sheaths and B cell follicles. In contrast, in B6 → LTβR−/− mice, T and B cells were mixed despite the presence of hematopoietically derived LTβR+/+ donor cells (Fig. 1 H). Taken together, the failure of LTβR+/+ BM-derived cells to restore GCs and an intact splenic architecture in LTβR−/− recipients provides evidence that LTβR on radioresistant stromal cells is required for these functions. However, LTβR−/− BM-derived cells were capable of establishing GCs in LTβ−/− recipients. This shows that for GC development in adult mice the presence of LTβR on radiosensitive BM-derived cells is dispensable, whereas the presence of LTβ on these cells is necessary. The latter conclusion is further supported by the finding that transfer of LTβ−/− BM into wild-type C57BL/6 recipients severely impaired GC formation.

LTβ and TNF from B Cells Are Required for Formation of Mature FDC Networks.

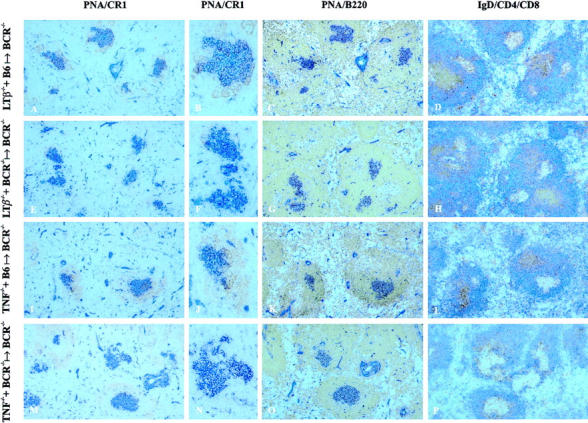

Expression of LTβ and TNF by hematopoietic cell lineages is required for GC formation (results above, and reference 35). Yet it is unclear whether a single hematopoietic lineage is necessary and, perhaps, sufficient for the production of LTβ and/or TNF, or whether different cellular sources can redundantly provide these ligands in GC reactions. In particular for TNF, the latter appears to be possible, since a great variety of cell types (e.g., macrophages, granulocytes, T cells, B cells, dendritic cells) can produce both soluble and membrane-bound TNF. Similarly, LTβ can be synthesized by three distinct cell types, namely T, B, and NK cells (15, 16, 36). Thus, to address the question of which cell type is required to express LTβ and TNF for GC establishment, compound BM chimeric mice were made. BM cells from BCR-deficient donors were mixed in a 1:1 ratio with BM cells from TNF−/− or LTβ−/− donors and transferred into myeloablatively irradiated BCR−/− recipients (LTβ−/− + BCR−/− → BCR−/−; TNF−/− + BCR−/− → BCR−/−). Control groups were established by reconstituting myeloablatively irradiated BCR−/− recipients with mixed BM from Ly5.1+ C57BL/6 wild-type donors and LTβ−/− or TNF−/− donors (LTβ−/− + B6 → BCR−/−; TNF−/− + B6 → BCR−/−). Since BCR−/− BM cannot give rise to mature B cells, peripheral B cells in the LTβ−/− + BCR−/− → BCR−/− and TNF−/− + BCR−/− → BCR−/− chimeras were genetically deficient in LTβ and TNF, respectively. All other radiosensitive BM-derived cell populations consisted of a mixture of wild-type and gene-targeted cells. In control groups (LTβ−/− + B6 → BCR−/−; TNF−/− + B6 → BCR−/−), all BM-derived cell populations—including B cells—were composed of wild-type and genetically deficient cells. After 6–7 wk, mice were immunized intraperitoneally with 5 μg of alum-precipitated NP19-CG, and 10 d later BM, spleen, lymph nodes, and serum were taken for analysis. BM chimerism and B cell chimerism were determined by Southern blotting and/or flow cytometric analysis of the CD45 isoforms Ly5.1 and Ly5.2 (see Materials and Methods, and Table I). BM chimerism was found to be comparable between experimental and control groups (Table I). Immunohistochemical analysis of splenic sections from LTβ−/− + BCR−/− → BCR−/− chimeras revealed the presence of few PNA+ cell clusters. Associated FDC networks were absent or significantly reduced in size (Fig. 2, E and F). Most of the PNA+ cell clusters were localized within B cell areas (Fig. 2, E–H). Albeit segregated from the T cell areas, the B cell areas did not represent well-defined B cell follicles. Spleens of LTβ−/− + B6 → BCR−/− control mice showed numerous PNA+ cell clusters in association with large FDC networks, most of them correctly localized within B cell follicles (Fig. 2, A–D). With regard to FDC network formation, the absence of TNF production by B cells in TNF−/− + BCR−/− → BCR−/− chimeras resulted in a phenotype similar to the one found in LTβ−/− + BCR−/− → BCR−/− chimeras: few PNA+ cell clusters contained considerably underdeveloped FDC networks, and most clusters lacked immunohistochemically detectable networks altogether (Fig. 2, M and N). However, in these mice, approximately two thirds of the PNA+ cell clusters were located around central arterioles in T cell areas (Fig. 2, O and P) and only one third was found in B cell areas (not shown). B cells segregated from T cells and some B cell follicles were observed (not shown). In TNF−/− + B6 → BCR−/− control chimeras, most PNA+ cell clusters associated with FDC networks were readily detectable in distinct B cell follicles (Fig. 2, I–L). All results regarding splenic FDC network formation in compound BM chimeras were confirmed by double labeling with PNA and FDC-M2 mAbs (data not shown). Taken together, the results demonstrate that expression of both LTβ and TNF by B cells is required for the development of mature splenic FDC networks, but not for the formation of PNA+ cell clusters.

Table I.

Degree of Chimerism in Compound BM Chimeras

| Donor BM | Recipient | Mouse no. | Chimerism | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BM | B cells | |||||||

| % | ||||||||

| LTβ−/− + B6 | BCR−/− | 1 | 75 (s) | 79 (f) | ||||

| 2 | 70 (s) | 79 (f) | ||||||

| 3 | 64 (s) | 82 (f) | ||||||

| 4 | 79 (s) | 79 (f) | ||||||

| LTβ−/− + BCR−/− | BCR−/− | 1 | 67 (s) | 98 (s) | ||||

| 2 | 70 (s) | 96 (s) | ||||||

| 3 | 86 (s) | ND | ||||||

| TNF−/− + B6 | BCR−/− | 1 | 54 (s) | 67 (f) | ||||

| 2 | 81 (s) | 69 (f) | ||||||

| 3 | 66 (s) | 76 (f) | ||||||

| 4 | ND | 62 (f) | ||||||

| TNF−/− + BCR−/− | BCR−/− | 1 | 64 (s) | 97 (s) | ||||

| 2 | 57 (s) | 97 (s) | ||||||

| 3 | 61 (s) | ND | ||||||

| 4 | 68 (s) | ND | ||||||

BM cells and peripheral B cells were purified as described in Materials and Methods. Chimerism was determined by Southern blotting (s) and/or by flow cytometric separation (f) of Ly5.1+ and Ly5.2+ cells and given as percentage of LTβ−/− or TNF−/− cells. The isolated peripheral B cells were 94–98% pure.

Figure 2.

Splenic GC development in compound BM chimeric mice. Irradiated recipients (n = 4 per group) were reconstituted with a 1:1 mixture of BM cells originating from the two donors indicated. After 6–7 wk, the mixed BM chimeras were immunized intraperitoneally with 5 μg NP19-CG adsorbed to alum. 10 d later, chimeras were killed and splenic cryosections were labeled with anti-CR1 (brown) and PNA (blue); anti-B220 (brown) and PNA (blue); or anti-CD4 (brown), anti-CD8 (brown), and anti-IgD (blue).

Specific Primary IgG Responses.

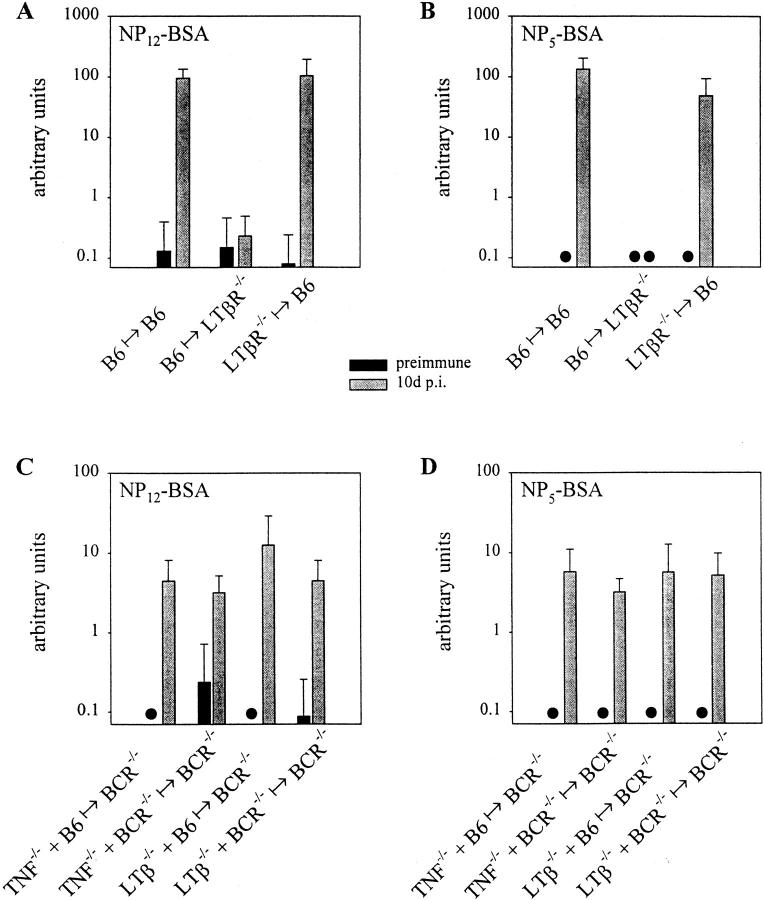

To investigate whether the observed abnormal GC reactions correlated with impaired specific IgG responses, NP-specific IgG titers were quantified in the sera of animals 10 d after immunization. Densely or sparsely haptenated BSA (NP12-BSA or NP5-BSA) was used for coating of ELISA plates, allowing detection of both low and high affinity NP-specific IgG. B6 → B6 and LTβR−/− → B6 chimeras responded to immunization with a comparable production of specific IgG, whereas B6 → LTβR−/− animals did not mount a significant primary IgG response (Fig. 3, A and B). Moreover, significant defects were not observed in B6 → LTβ−/−, LTβ−/− → B6, or LTβR−/− → LTβ−/− chimeras (data not shown). In B6 → LTβR−/− chimeras, the impaired primary IgG response correlated with multiple defects in the organization of peripheral lymphoid tissues such as lack of lymph nodes and Peyer's patches, disruption of T–B cell segregation, and aberrant PNA+ cell clusters without FDC networks in the spleen (macroscopic examination, and Fig. 1, E–H). In contrast, LTβ−/− + BCR−/− → BCR−/− and TNF−/− + BCR−/− → BCR−/− mice contained lymph nodes, PNA+ cell clusters, and distinct T and B cell areas, yet differed from their control groups regarding splenic FDC network formation (Fig. 2). Here, differences in NP-specific IgG titers between experimental and control groups were not statistically significant (Fig. 3, C and D), implying that a lack or strong reduction of splenic FDC networks does not necessarily lead to impaired specific primary IgG responses.

Figure 3.

NP-specific IgG titers in the sera of reciprocal (A and B) and mixed BM chimeras (C and D). Chimeric mice were made and immunized as described in the legends to Figs. 1 and 2 (n = 3–5 per group). Sera were taken before and 10 d after immunization. The amounts of anti-NP antibodies were determined as described in Materials and Methods. Note that two different batches of NP19-CG adsorbed to alum were used for immunization, precluding a direct comparison of values from A and B with those from C and D. •, All values were below the detection limit.

Discussion

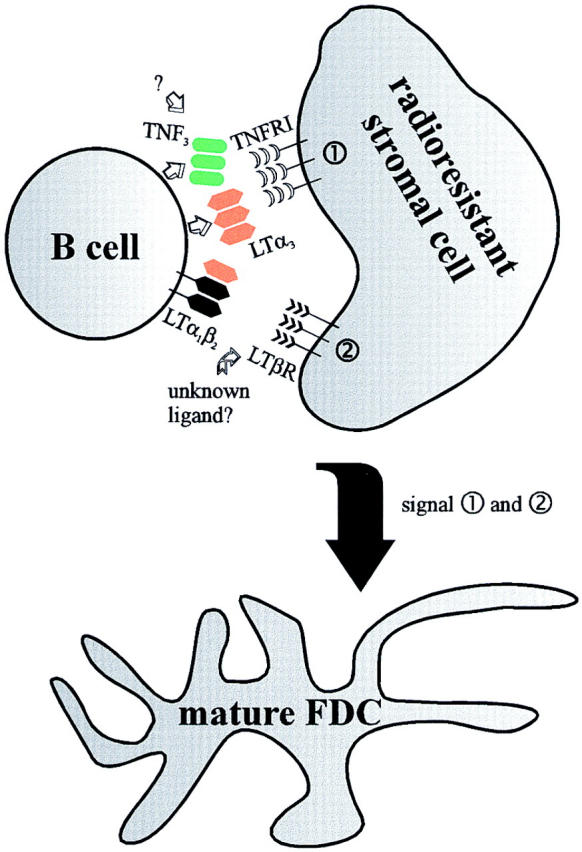

Mice deficient for the TNFRp55 or the LTβR lack FDC networks and correctly localized PNA+ cell clusters, demonstrating the requirement of signals from these receptors for GC formation (20, 21). Development of PNA+ cell clusters and FDC networks in TNFRp55−/− mice is not rescued by transplantation of wild-type BM (25, 26), whereas TNFRp55−/− BM is as efficient as wild-type BM in reconstituting these structures in LTα−/− mice (26). These data indicate that for establishment of GCs, TNFRp55 is required on radioresistant stromal cells and not on radiosensitive BM-derived cells (25, 26). In the present study, LTβR−/− → LTβ−/−, LTβR−/− → B6, and B6 → LTβR−/− BM chimeric mice were used for the analysis of GC development, and evidence is provided that for formation of FDC networks expression of LTβR, like TNFRp55, is required on radioresistant cells, but not on BM-derived radiosensitive cells. Since FDCs are known to withstand high doses of irradiation (37), it is likely that putative FDC precursors are radioresistant cells that depend on signals from the TNFRp55 (25, 26) and the LTβR (this study) for differentiation to mature FDCs (Fig. 4). Alternatively, it is conceivable that radioresistant stromal cells different from FDC precursors exist that provide molecules needed for FDC maturation and depend on signals from the TNFRp55 and/or the LTβR in order to fulfill this function.

Figure 4.

Model of the molecular interactions essential for the establishment of splenic FDC networks associated with PNA+ cell clusters. B cells provide the ligands LTα (references 28, 29), TNF, and LTβ required for an effective engagement of the TNFRp55 (references 25, 26) and the LTβR on specific radioresistant cells, which most likely represent FDC precursors. In this cell population, both signaling pathways have to be functional for mature splenic FDC networks to form. Note that the present data do not elucidate whether signaling from the TNFRp55 and the LTβR has to occur simultaneously or consecutively in the putative FDC precursors. TNFRI, TNFRp55.

Comparable to LTβR−/− mice, mice with a disrupted LTα gene are devoid of marginal zones, proper T–B cell segregation, correctly localized PNA+ cell clusters, and FDC networks (20, 38, 39). Recently, experiments by Fu et al. (28) and Gonzalez et al. (29) led to the identification of the cellular source of LTα needed for the establishment of FDC networks and correctly localized PNA+ cell clusters in the spleen. The first group used BM from LTα−/− mice mixed together with BM from TCR−/− or BCR−/− mice to reconstitute LTα−/− mice. In chimeric mice, all T or B lymphocytes were deficient in LTα, whereas the other cells of hematopoietic origin consisted of a mixture of LTα−/− and LTα+/+ genotypes. The formation of PNA+ cell clusters and FDC networks was precluded only in BM chimeras in which B cells were deficient for LTα, indicating that LTα-producing B cells are essential for the establishment of GCs (28). Gonzalez et al. (29) adoptively transferred purified lymphocytes into SCID mice and also showed the dependence of the FDC network on LTα-producing B lymphocytes. Since LTα together with LTβ can form ligands specific for LTβR (16–18), it was suggested that LTα1β2 heterotrimers on B cells are required for FDC development. In line with this hypothesis, wild-type B cells transferred into SCID mice that were simultaneously treated with LTβR–Fc fusion protein did not induce FDC networks (29). In our study, a mixture of BM cells from BCR−/− and LTβ−/− mice were transferred into irradiated BCR−/− recipients. In the absence of LTβ-producing B cells, but not of LTβ-producing T cells (Endres, R., M.B. Alimzhanov, and K. Pfeffer, unpublished results), FDC networks were strongly reduced or absent. However, PNA+ cell clusters in B cell areas were observed. These results are in contrast to the findings of Fu and colleagues, who did not detect any correctly localized PNA+ cell clusters and FDC-specific labeling in BCR−/− + LTα−/− → LTα−/− compound BM chimeras (28). This discrepancy may be explained by different experimental conditions, i.e., Fu et al. reconstituted LTα−/− mice, which show a severely disorganized splenic architecture (20, 38), whereas here B cell–deficient mice are reconstituted, which apart from missing B cells and FDC networks appear to have a conserved splenic architecture (Endres, R., M.B. Alimzhanov, and K. Pfeffer, unpublished results). Alternatively, it is conceivable that LTβ−/− B cells still produce LTα homotrimers which engage the TNFRp55 and thereby induce GC formation, although much less efficiently than wild-type B cells. However, since signaling via the LTβR appears indispensable for FDC development (this study, and reference 21), in order to explain the appearance of few underdeveloped FDC clusters in LTβ−/− + BCR−/− → BCR−/− chimeras and in LTβ−/− mice (this study, and references 22, 24), one has to assume that ligands other than LTα1β2 can engage the LTβR on radioresistant cells at least to some extent. A recently identified member of the TNF ligand family, LIGHT, may serve this function, since it was shown to bind to the LTβR (40).

Besides LTα3 homotrimers, soluble and membrane-bound forms of TNF3 signal via the TNFRp55. TNF−/− and TNFRp55−/− mice have comparable phenotypes in that they lack B cell follicles, FDC networks, and correctly localized PNA+ cell clusters (19, 20). Since TNF is known to be produced by many cell types (11–13), we asked whether B cell–derived TNF is required for the induction of splenic FDC networks by generating compound TNF−/− + BCR−/− → BCR−/− BM chimeras. Surprisingly, these chimeras did not contain mature splenic FDC networks, showing a phenotype similar to the one observed in chimeras devoid of LTβ-producing B cells. Thus, TNF is yet another mediator in B cell–pre-FDC interactions which lead to FDC network development. In contrast to TNF−/− mice (19), TNF−/− + BCR−/− → BCR−/− chimeras have few underdeveloped FDC networks associated with PNA+ cell clusters. This indicates that, in the absence of B cell– derived TNF, TNF from cells other than B cells can provide signals for FDC network development albeit to a limited extent. It is noteworthy that Alexopoulou et al. observed a reduced production of TNF in LTα−/− mice after LPS treatment (24). The authors suggested that in the LTα−/− mouse strain (38), TNF gene expression is altered by the neor cassette used to inactivate the LTα gene (24). The mutation introduced in the LTβ gene (22) presumably does not interfere with the expression of the neighboring TNF and LTα genes. Therefore, differences in GC formation between chimeras devoid of LTα-producing B cells versus LTβ-producing B cells could result from different amounts of TNF produced by LTα−/− and LTβ−/− B cells, respectively. LTα−/− B cells, but not LTβ−/− B cells, might fail to provide local TNF concentrations high enough to allow formation of few underdeveloped GCs.

One simple model of splenic FDC network maturation, which accommodates data from several groups (25, 26, 28, 29, and this study), is depicted in Fig. 4. Radioresistant stromal cells have to receive at least two different signals, one via the LTβR (this study) and the other via the TNFRp55 (25, 26), in order to give rise to a local FDC network. Most likely, these radioresistant cells represent hitherto unidentified FDC precursors, either residing at the site of B cell accumulation or attracted to this location by the B cells. Alternatively, the radioresistant cells are not FDC precursors, but serve as inducible sources of unknown factors required for differentiation of FDC precursors to mature local FDC networks. The cytokines required for FDC network development, TNF3, LTα3 and LTα1β2, are provided by B lymphocytes (28, 29, and this study). To date, the temporal and spatial interrelations of TNFRp55 and LTβR transduced signals remain unclear. It is possible that these two signals act during distinct stages of FDC differentiation.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant Pf 259/2-4) and the Sonderforschungsbereich 391 and 243, Klinische Forschergruppe Postoperative Immunparalyse und Sepsis (grant Si208/5-1). M.B. Alimzhanov was supported by a fellowship from the European Molecular Biology Organization. S.A. Nedospasov is an international research scholar of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- AP

alkaline phosphatase

- FDC

follicular dendritic cell

- GC

germinal center

- LT

lymphotoxin

- BCR

B cell receptor

- PNA

peanut agglutinin

Footnotes

The continuous and generous support of H. Wagner is greatly appreciated. The authors thank E. Schaller, U. Huffstadt, S. Weiss, and K. Mink for expert technical assistance. The authors are also grateful to H.R. Rodewald and G. Kollias for providing Ly5.1+ C57BL/6 and TNF−/− mice, respectively, and thank H. Neubauer, T. Novobrantseva, S. Scheu, and H. Häcker for critical reading of the manuscript and for scientific advice.

R. Endres and M.B. Alimzhanov contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Kosco-Vilbois MH, Bonnefoy JY, Chvatchko Y. The physiology of murine germinal center reactions. Immunol Rev. 1997;156:127–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb00964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelsoe G, Zheng B. Sites of B-cell activation in vivo. Curr Opin Immunol. 1993;5:418–422. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(93)90062-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacLennan IC. Germinal centers. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:117–139. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tew JG, Wu J, Qin D, Helm S, Burton GF, Szakal AK. Follicular dendritic cells and presentation of antigen and costimulatory signals to B cells. Immunol Rev. 1997;156:39–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb00957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu YJ, Arpin C. Germinal center development. Immunol Rev. 1997;156:111–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb00963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ware CF, VanArsdale TL, Crowe PD, Browning JL. The ligands and receptors of the lymphotoxin system. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1995;198:175–218. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-79414-8_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruddle NH. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF-alpha) and lymphotoxin (TNF-beta) Curr Opin Immunol. 1992;4:327–332. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(92)90084-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tartaglia LA, Goeddel DV. Two TNF receptors. Immunol Today. 1992;13:151–153. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90116-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Banner DW, D'Arcy A, Janes W, Gentz R, Schoenfeld HJ, Broger C, Loetscher H, Lesslauer W. Crystal structure of the soluble human 55 kd TNF receptor- human TNF beta complex: implications for TNF receptor activation. Cell. 1993;73:431–445. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90132-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kriegler M, Perez C, DeFay K, Albert I, Lu SD. A novel form of TNF/cachectin is a cell surface cytotoxic transmembrane protein: ramifications for the complex physiology of TNF. Cell. 1988;53:45–53. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90486-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Garra A, Stapleton G, Dhar V, Pearce M, Schumacher J, Rugo H, Barbis D, Stall A, Cupp J, Moore K. Production of cytokines by mouse B cells: B lymphomas and normal B cells produce interleukin 10. Int Immunol. 1990;2:821–832. doi: 10.1093/intimm/2.9.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vassalli P. The pathophysiology of tumor necrosis factors. Annu Rev Immunol. 1992;10:411–452. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.10.040192.002211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pistoia V, Corcione A. Relationships between B cell cytokine production in secondary lymphoid follicles and apoptosis of germinal center B lymphocytes. Stem Cells (Dayton) 1995;13:487–500. doi: 10.1002/stem.5530130506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Browning JL, Dougas I, Ngam-ek A, Bourdon PR, Ehrenfels BN, Miatkowski K, Zafari M, Yampaglia AM, Lawton P, Meier W, et al. Characterization of surface lymphotoxin forms. Use of specific monoclonal antibodies and soluble receptors. J Immunol. 1995;154:33–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Browning JL, Ngam-ek A, Lawton P, DeMarinis J, Tizard R, Chow EP, Hession C, O'Brine-Greco B, Foley SF, Ware CF. Lymphotoxin beta, a novel member of the TNF family that forms a heteromeric complex with lymphotoxin on the cell surface. Cell. 1993;72:847–856. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90574-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Browning JL, Sizing ID, Lawton P, Bourdon PR, Rennert PD, Majeau GR, Ambrose CM, Hession C, Miatkowski K, Griffiths DA, et al. Characterization of lymphotoxin-alpha beta complexes on the surface of mouse lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1997;159:3288–3298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crowe PD, VanArsdale TL, Walter BN, Ware CF, Hession C, Ehrenfels B, Browning JL, Din WS, Goodwin RG, Smith CA. A lymphotoxin-beta-specific receptor. Science. 1994;264:707–710. doi: 10.1126/science.8171323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Force WR, Walter BN, Hession C, Tizard R, Kozak CA, Browning JL, Ware CF. Mouse lymphotoxin-beta receptor. Molecular genetics, ligand binding, and expression. J Immunol. 1995;155:5280–5288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pasparakis M, Alexopoulou L, Episkopou V, Kollias G. Immune and inflammatory responses in TNF-α–deficient mice: a critical requirement for TNF-α in the formation of primary B cell follicles, follicular dendritic cell networks and germinal centers, and in the maturation of the humoral immune response. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1397–1411. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsumoto M, Mariathasan S, Nahm MH, Baranyay F, Peschon JJ, Chaplin DD. Role of lymphotoxin and the type I TNF receptor in the formation of germinal centers. Science. 1996;271:1289–1291. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5253.1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fütterer A, Mink K, Luz A, Kosco-Vilbois MH, Pfeffer K. The lymphotoxin β receptor controls organogenesis and affinity maturation in peripheral lymphoid tissues. Immunity. 1998;9:59–70. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80588-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alimzhanov MB, Kuprash DV, Kosco-Vilbois MH, Luz A, Turetskaya RL, Tarakhovsky A, Rajewsky K, Nedospasov SA, Pfeffer K. Abnormal development of secondary lymphoid tissues in lymphotoxin beta-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9302–9307. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koni PA, Sacca R, Lawton P, Browning JL, Ruddle NH, Flavell RA. Distinct roles in lymphoid organogenesis for lymphotoxins alpha and beta revealed in lymphotoxin beta-deficient mice. Immunity. 1997;6:491–500. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80292-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alexopoulou L, Pasparakis M, Kollias G. Complementation of lymphotoxin-α knockout mice with tumor necrosis factor–expressing transgenes rectifies defective splenic structure and function. J Exp Med. 1998;188:745–754. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.4.745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tkachuk M, Bolliger S, Ryffel B, Pluschke G, Banks TA, Herren S, Gisler RH, Kosco-Vilbois MH. Crucial role of tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 expression on nonhematopoietic cells for B cell localization within the splenic white pulp. J Exp Med. 1998;187:469–477. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.4.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsumoto M, Fu YX, Molina H, Huang G, Kim J, Thomas DA, Nahm MH, Chaplin DD. Distinct roles of lymphotoxin α and the type I tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor in the establishment of follicular dendritic cells from non-bone marrow–derived cells. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1997–2004. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.12.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsumoto M, Fu YX, Molina H, Chaplin DD. Lymphotoxin-alpha-deficient and TNF receptor-I-deficient mice define developmental and functional characteristics of germinal centers. Immunol Rev. 1997;156:137–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb00965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fu YX, Huang G, Wang Y, Chaplin DD. B lymphocytes induce the formation of follicular dendritic cell clusters in a lymphotoxin α–dependent fashion. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1009–1018. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.7.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gonzalez M, Mackay F, Browning JL, Kosco-Vilbois MH, Noelle RJ. The sequential role of lymphotoxin and B cells in the development of splenic follicles. J Exp Med. 1998;187:997–1007. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.7.997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kitamura D, Rajewsky K. Targeted disruption of mu chain membrane exon causes loss of heavy-chain allelic exclusion. Nature. 1992;356:154–156. doi: 10.1038/356154a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mombaerts P, Mizoguchi E, Grusby MJ, Glimcher LH, Bhan AK, Tonegawa S. Spontaneous development of inflammatory bowel disease in T cell receptor mutant mice. Cell. 1993;75:274–282. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80069-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Endres R, Luz A, Schulze H, Neubauer H, Fütterer A, Holland SM, Wagner H, Pfeffer K. Listeriosis in p47phox−/− and TRp55−/−mice: protection despite absence of ROI and susceptibility despite presence of RNI. Immunity. 1997;7:419–432. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80363-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cumano A, Rajewsky K. Structure of primary anti-(4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenyl)acetyl (NP) antibodies in normal and idiotypically suppressed C57BL/6 mice. Eur J Immunol. 1985;15:512–520. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830150517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kinoshita, T., T. Fujita, and R. Tsunoda. 1991. Expression of complement receptors CR1 and CR2 on murine follicular dendritic cells and B lymphocytes. In Dendritic Cells in Lymphoid Tissues. Y. Imai, J.G. Tew, and E.C.M. Hoefsmit, editors. Elsevier Science B.V., Amsterdam. p. 271.

- 35.Ryffel B, Di Padova F, Schreier MH, Le Hir M, Eugster HP, Quesniaux VF. Lack of type 2 T cell- independent B cell responses and defect in isotype switching in TNF-lymphotoxin alpha-deficient mice. J Immunol. 1997;158:2126–2133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ware CF, Crowe PD, Grayson MH, Androlewicz MJ, Browning JL. Expression of surface lymphotoxin and tumor necrosis factor on activated T, B, and natural killer cells. J Immunol. 1992;149:3881–3888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Humphrey JH, Grennan D, Sundaram V. The origin of follicular dendritic cells in the mouse and the mechanism of trapping of immune complexes on them. Eur J Immunol. 1984;14:859–864. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830140916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Togni P, Goellner J, Ruddle NH, Streeter PR, Fick A, Mariathasan S, Smith SC, Carlson R, Shornick LP, Strauss-Schoenberger J, Chaplin DD. Abnormal development of peripheral lymphoid organs in mice deficient in lymphotoxin. Science. 1994;264:703–707. doi: 10.1126/science.8171322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Banks TA, Rouse BT, Kerley MK, Blair PJ, Godfrey VL, Kuklin NA, Bouley DM, Thomas J, Kanangat S, Mucenski ML. Lymphotoxin-alpha-deficient mice. Effects on secondary lymphoid organ development and humoral immune responsiveness. J Immunol. 1995;155:1685–1693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mauri DN, Ebner R, Montgomery RI, Kochel KD, Cheung TC, Yu GL, Ruben S, Murphy M, Eisenberg RJ, Cohen GH, et al. LIGHT, a new member of the TNF superfamily, and lymphotoxin alpha are ligands for herpesvirus entry mediator. Immunity. 1998;8:21–30. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80455-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]