Abstract

CFTR (cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator), a member of the ABC (ATP-binding cassette) superfamily of membrane proteins, possesses two NBDs (nucleotide-binding domains) in addition to two MSDs (membrane spanning domains) and the regulatory ‘R’ domain. The two NBDs of CFTR have been modelled as a heterodimer, stabilized by ATP binding at two sites in the NBD interface. It has been suggested that ATP hydrolysis occurs at only one of these sites as the putative catalytic base is only conserved in NBD2 of CFTR (Glu1371), but not in NBD1 where the corresponding residue is a serine, Ser573. Previously, we showed that fragments of CFTR corresponding to NBD1 and NBD2 can be purified and co-reconstituted to form a heterodimer capable of ATPase activity. In the present study, we show that the two NBD fragments form a complex in vivo, supporting the utility of this model system to evaluate the role of Glu1371 in ATP binding and hydrolysis. The present studies revealed that a mutant NBD2 (E1371Q) retains wild-type nucleotide binding affinity of NBD2. On the other hand, this substitution abolished the ATPase activity formed by the co-purified complex. Interestingly, introduction of a glutamate residue in place of the non-conserved Ser573 in NBD1 did not confer additional ATPase activity by the heterodimer, implicating a vital role for multiple residues in formation of the catalytic site. These findings provide the first biochemical evidence suggesting that the Walker B residue: Glu1371, plays a primary role in the ATPase activity conferred by the NBD1–NBD2 heterodimer.

Keywords: co-immunoprecipitation; cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR); nucleotide-binding domain (NBD); 2 (3)-O-(2,4,6-trinitrophenyl)adenosine 5-triphosphate (TNP-ATP) affinity; protein purification; Walker B motif

Abbreviations: ABC, ATP-binding cassette; CF, cystic fibrosis; CFTR, CF transmembrane conductance regulator; HA, haemagglutinin; NBD, nucleotide-binding domain; MSD, membrane spanning domain; PFO, pentadecafluorooctanoic acid; TNP-ATP, 2 (3)-O-(2,4,6-trinitrophenyl)adenosine 5-triphosphate

INTRODUCTION

The CFTR [CF (cystic fibrosis) transmembrane conductance regulator] is a member of the ABC (ATP-binding cassette) superfamily of membrane transport proteins [1,2]. Like other members of this family, it is a multi-domain protein that consists of two MSDs (membrane spanning domains) and two cytoplasmic NBDs (nucleotide-binding domains). In addition, it contains a distinct regulatory or ‘R’ domain, which is phosphorylated at multiple sites by protein kinase A and protein kinase C [3–8]. CFTR is a unique member of the ABC transporter family because it functions as a regulated chloride channel and naturally occurring mutations cause the disease CF (cystic fibrosis) [9,10].

CFTR channel gating is regulated by phosphorylation of the R domain and also by binding and hydrolysis of ATP at the NBDs [11–13]. Several studies have shown that dimeric assembly of NBDs is essential for ABC transporter ATPase function [14,15]. The crystal structure of the ATPase domain of Rad50 (radiation-dependent 50) in complex with ATP was the first to reveal a head to tail arrangement of two NBDs [16]. Since then, high-resolution crystal structures of full-length ABC transporters such as BtuCD have revealed a similar orientation for the NBDs. In the BtuD NBD dimer structure, two nucleotide-binding and catalytic sites are formed at the dimer interface by juxtaposition of the signature motif of one monomer with the Walker A and B motifs of the other monomer [17]. A recent study performed by our group provided direct empirical evidence suggesting that while each NBD of CFTR is capable of binding nucleotide, heterodimerization of the NBDs is necessary to confer optimal ATPase activity [14].

Unlike prokaryotic NBDs, the NBDs of CFTR are structurally asymmetric; NBD1 contains a conserved ABC signature motif and Walker A motif, yet lacks conservation of two residues implicated in interaction with hydrolytic water, a Walker B glutamate residue and a histidine residue. NBD2 possesses sequence conservation in Walker A and B and the switch motifs but lacks conservation in the ABC signature motif [16]. From the sequence alignments and molecular modelling of CFTR-NBDs using prokaryotic NBD dimers as templates, it is predicted that the NBDs of CFTR interact in a head to tail orientation, resulting in the formation of one rather than two catalytic sites. One site containing the Walker A and B from NBD1 and the signature motif from NBD2 would be non-conventional and exhibit little ATP hydrolysis [11,18]. The other site would comprise a conventional catalytic site containing the Walker A and B from NBD2 and the signature motif from NBD1. This prediction has been supported in direct biochemical assays of the relative ATPase activity of Walker A lysine mutants in NBD1 and NBD2 [19] as well as studies showing vanadate trapping of 8-azido-ATP in NBD2 [15].

Gadsby et al. [11,18] recently proposed a model of coupling between ATP hydrolysis and channel gating. In this model, ATP binding to both sites promotes dimerization and conformational changes leading to channel gating to the open state [11,18]. Subsequent hydrolysis of nucleotide at the one conventional site (comprising Walker A and B and switch from NBD2 and signature motif from NBD1) precedes channel closing. In support of this model, mutation of the Walker A lysine (K1250A) or the Walker B glutamate (E1371A/Q) in the conventional catalytic site leads to defective channel closure, resulting in prolonged channel open times [11,18]. However, a key aspect of this model has yet to be directly tested. Although the consequences of mutating the Walker A lysine of NBD2 (K1250A) on nucleotide binding and hydrolysis have been measured [19], to date there have been no direct measurements of the consequences of mutating the putative catalytic base, Glu1371, on nucleotide binding and hydrolysis. Further, it has yet to be determined whether conservation at this site is sufficient to confer catalytic activity.

In the present study, we determined the role of the Walker B glutamate residue directly by mutagenesis of NBD2, evaluation of nucleotide binding by purified NBD2 and measurement of the ATPase activity by the purified NBD1–NBD2E1371Q heterodimer. In order to determine whether conservation of the Walker B glutamate is sufficient to confer catalytic activity, we evaluated the consequences of mutating the non-conserved serine at position 573 in NBD1 to glutamate. Our findings support a model wherein the Walker B glutamate is required for, but not sufficient for, catalytic activity by the CFTR-NBD1–NBD2 heterodimeric complex.

METHODS

Generation of NBD1S573E and NBD2E1371Q constructs

Mutations were introduced into human NBD1 or human NBD2 cDNA in the pFastBac1 vector using the QuikChange® Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) and specifically designed primers. For S573E the following primers were used: reverse primer 5′-CTAGGTATCCAAAAGGCTCGTCTAATAAATACAAAT-3′ and forward primer 5′-ATTTGTATTTATTAGACGAGCCTTTTGGATACCTAG-3′. For E1371Q, the reverse primer 5′-CAAATGAGCACTGGGTTGATCAAGCAGC-3′ and the forward primer 5′-GCTGCTTGATCAACCCAGTGCTCATTTG-3′ were used.

Isolation and co-immunoprecipitation of soluble NBDs

Suspension cultures of Sf9 cells were co-infected with various combinations of wild-type and mutant NBD1 and NBD2 viruses for 40 h at 26 °C. Cells were then harvested in PBS (pH 8.0) and disrupted using a French press (1000 lbf/in2; 1 lbf/in2=6.9 kPa). After this cell lysates were centrifuged at 100000 g for 2 h at 4 °C. The supernatant containing the soluble NBDs was retained and a co-immunoprecipitation was performed using either the monoclonal antibody L12B4 directly against NBD1 (Chemicon) or using a monoclonal, anti-HA (haemagglutinin) antibody (Covance). These antibodies were also used for immunoblotting.

Purification and renaturation of co-expressed wild-type and mutant NBDs

Sf9 cell cultures grown in suspension (0.5–1 litre) were co-infected with one or two viruses containing wild-type or mutant CFTR-NBDs, each bearing polyhistidine tags for 40 h at 26 °C. Cells were harvested in PBS (pH 7.4), disrupted using a French press (1000 lbf/in2) and the fragments were centrifuged at 100000 g at 4 °C for 2 h. The pellet produced by the above centrifugation was solubilized for 4 h in 40 ml of 8% (w/v) PFO (pentadecafluoro-octanoic acid; Oakwood Products, West Columbia, SC, U.S.A.) and 25 mM phosphate (pH 8.0) at 25 °C. Detergent-solubilized His-tagged NBD protein was then filtered through a 0.2 μm syringe filter and applied to a freshly generated nickel column at a rate of 2 ml/min. A pH gradient (pH 8.0–6.0) in 2% PFO and 100 mM NaCl was then applied using FPLC, and 2 ml fractions were collected. The fractions eluted from the column were assessed for the presence of NBD protein by dot-blot analysis. The monoclonal antibodies L12B4 (Chemicon) and anti-HA (Covance) were used to detect NBD1 and NBD2 respectively. Immunopositive fractions were further analysed by SDS/PAGE and fractions containing pure protein (single silver-stained protein band on SDS/PAGE) were combined and dialysed in a Specta/Por dialysis membrane (cut-off, 12–14 kDa) overnight at 4 °C against 4 litres of a buffer containing 10% glycerol, 50 mM Tris/HCl, 50 mM NaCl, 25 μM DTT (dithiothreitol) and 50 μM EGTA at pH 7.4. Dialysis was continued in 10% glycerol, 50 mM Tris/HCl, 50 mM NaCl, 50 μM dodecyl maltoside and 50 μM MgCl2 at pH 7.4 (2×4 litres, 4 °C). Renatured protein samples were concentrated 4-fold in a Centricon YM-10 concentrator (Amico Ultra-15: molecular mass cut-off of 5 kDa; Amicon). In studies where NBD1 and NBD2 were refolded together, equal amounts of purified NBD1 and NBD2 in 2% PFO were mixed together in a Specta/Por dialysis membrane, and renaturation conducted as previously described [14].

TNP-ATP [2 (3)-O-(2,4,6-trinitrophenyl)adenosine 5-triphosphate] binding

Binding of TNP-ATP to wild-type and mutant NBD1 or NBD2 proteins was analysed by steady-state fluorescence measurements in a fluorescence spectrophotometer (Hitachi). Protein (20 μg) was prepared in 1 ml of a buffer containing: 10% glycerol, 50 mM Tris/HCl, 50 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2 and 0.1 μM dodecyl maltoside at pH 7.5 in 1 ml (1 cm×1 cm optical path) fluorescence cuvettes. TNP-ATP was added at various final concentrations. Experiments were performed at 25 °C with continuous stirring. The samples were excited at 410 nm and the emission intensity at 550 nm was recorded. A protein-less sample was used for subsequent correction of the inner filter effect on the fluorescence of TNP nucleotides as previously described [14]. Kd was calculated by fitting a single site binding curve using GraphPad Prism software.

ATPase measurements

ATPase activity was measured as the production of [α-32P]ADP from [α-32P]ATP by the NBDs as described previously [19,20]. The assay was carried out in a reaction mixture (50 μl) containing 1 μg of NBD1 or NBD2, 10% glycerol, 50 mM Tris/HCl, 50 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.1 μM dodecyl maltoside and 8 μCi of [α-32P]ATP (3000 Ci/mmol) and 1.0 mM unlabelled ATP (pH 7.5). ATPase activity was also measured as the production of [γ-32]Pi from [γ-32P]ATP. Pi and ADP were separated from ATP by TLC using the same elution conditions as described by Gross et al. [21].

ATP depletion experiments

Infected Sf9 cells expressing NBD1 and NBD2 (wild-type or E1371Q) were washed with PBS and collected by centrifugation. Cellular ATP was manipulated by replacing extracellular glucose [22]. The cells were incubated with 5 ml of control solution (143 mM NaCl, 10 mM glucose, 1 mM MgATP, 20 mM Mes and 0.5 mM CaCl2, pH 6.5) or ATP depletion solution (143 mM NaCl, 5 μM rotenone, 5 mM deoxyglucose, 20 mM Mes and 0.5 mM CaCl2, pH 6.5) at room temperature (22 °C) for 1 h with mixing. The cells were collected by centrifugation at 110 g for 5 min at room temperature and washed with PBS, and resuspended in 2 ml of PBS with protease inhibitors. The cells were lysed by French pressing and the samples were centrifuged at 690 g for 1 min. The supernatants were used in co-immunoprecipitation procedure using anti-HA antibody.

Analyses

The ATP dose–response curves for the ATPase activities by NBD2 and NBD1–NBD2 were fit with the Michaelis–Menten equation using the curve-fitting program Prism (GraphPad). The dose–response of TNP-ATP binding to the mutant NBDs: S573E and E1371Q was analysed using a single site binding algorithm and curve fitting by GraphPad Prism to determine Kd values.

RESULTS

Walker B mutations do not alter nucleotide binding to isolated NBD1 or NBD2

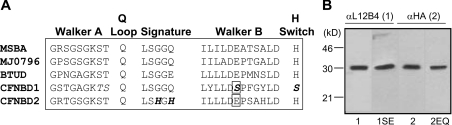

As previously discussed, the Walker B glutamate residue thought to act as the catalytic base in ABC NBDs is only conserved in NBD2 of CFTR (Figure 1A). In order to evaluate the role of this conserved glutamate (Glu1371), the mutant E1371QNBD2 was generated. Conversely, the corresponding, non-conserved residue in NBD1, Ser573, was mutated to glutamate (S573ENBD1) to determine if this substitution is sufficient to confer a change in ATP interaction. The consequences of these mutations were investigated in the context of proteins corresponding to NBD1 and NBD2. In our previous studies, we described the methods for expressing proteins corresponding to NBD1 (residues: 380–660) and NBD2 (residues: 1201–1446) of CFTR using the Sf9-baculovirus expression system [14]. Each of these proteins were engineered to possess a polyhistidine tag on their C-terminus and an HA tag was attached to the N-terminus of NBD2 [14]. Similarly, the Walker B mutant proteins (S573E) and (E1371Q) bearing polyhistidine tags and an HA tag, in the case of E1371Q, were expressed in Sf9 cells using the baculovirus system (Figure 1B). Each mutant was purified and renatured as described in our previous studies of the wild-type domains: NBD1 and NBD2 [14].

Figure 1. Expression of Walker B mutants of NBD1 and NBD2.

(A) Alignment of sequence motifs that contribute to nucleotide binding and hydrolysis by ABC NBDs [16]. Those residues that lack conservation in CF-NBD1 or CF-NBD2 are indicated in boldface and italics. The residues that have been mutated in the present paper are enclosed in a box. (B) Western blots of Sf9 cells lysates expressing NBD1 (1), NBD1S573E (1SE), NBD2 (2) or NBD2E1371Q (2EQ). Western blots were probed using either the anti-L12B4 antibody (NBD1 and NBD1S573E), or the anti-HA antibody (NBD2 and NBD2E1371Q).

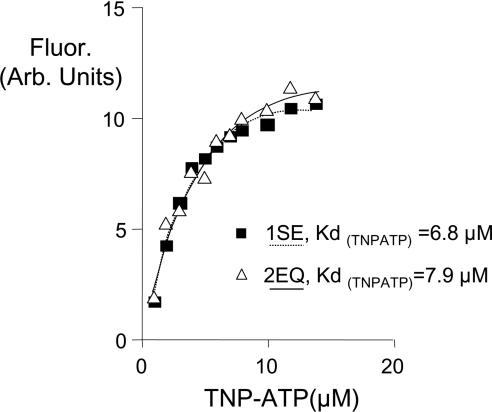

Both the purified NBD1 mutant (S573E) and purified NBD2 mutant (E1371Q) bind the ATP analogue, TNP-ATP, with low micromolar affinities (Figure 2), similar to the affinities previously reported for wild-type NBD1 (11.6 μM) and NBD2 (10.6 μM) [14]. These findings support the claim that these proteins have been functionally renatured as NBDs and that these mutations have not disrupted this particular function.

Figure 2. Walker B mutants of NBD1 and NBD2 exhibit normal nucleotide binding.

The fluorescence increase of TNP-ATP upon binding to NBD1S573E (1SE, solid square) and NBD2E1371Q (2EQ, open triangle) was measured at a λex of 410 nm and a λem of 550 nm at varying TNP-ATP concentrations. Data were fitted using a single site binding algorithm equation (Prism software) to yield Kd values. r2>0.95 for both data sets. r, correlation coefficient.

Walker B mutant of NBD2 (E1371Q) inhibits normal ATPase activity conferred by heterodimerization with NBD1

The ATPase activity of CFTR is conferred by heterodimerization of NBD1 and NBD2. We showed in our previous studies that purified, reconstituted CFTR-NBD1 and CFTR-NBD2 proteins are capable of functionally interacting to mediate ATPase activity [14]. Therefore, in order to evaluate the consequences of mutations in single NBDs on ATPase activity, each mutant must be co-expressed with a wild-type NBD partner. Co-infection of Sf9 cells with baculovirus containing NBD1S573E (1SE) and baculo-virus containing wild-type NBD2 (2) led to the expression of both proteins (results not shown). Similarly, co-infection of Sf9 cells with baculovirus containing NBD2E1371Q (2EQ) and wild-type NBD1 (1) led to the expression of both proteins. Each of the above combinations of co-expressed proteins was purified by metal affinity and renatured as described in our previous work [14].

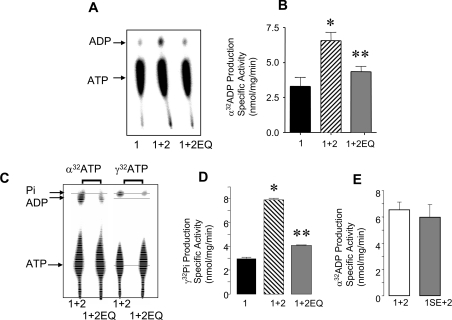

In order to evaluate the consequences of mutating the putative catalytic base, Glu1371, on the activity of the NBD heterodimer, we compared the ATPase activity of co-purified NBD2EQ and NBD1 with the activity of co-expressed wild-type NBD1 plus NBD2 or NBD1 alone. ATPase activity was measured as the production of [α-32P]ADP from [α-32P]ATP by purified NBDs in the presence of 1 mM ATP. As shown in Figures 3(A) and 3(B), the NBD1 protein alone exhibits low levels of specific activity (n=3). Copurified and renatured NBD1 plus NBD2 (1+2) exhibits significantly increased specific activity relative to NBD1 (*P<0.0025, n=5). These findings confirm our previous observations and suggest that NBD1 and NBD2 associate to confer enhanced ATPase activity [14]. On the other hand, the specific activity of co-purified NBD1 plus NBD2E1371Q (1+2EQ) is not significantly different from isolated NBD1 alone (P>0.05, n=3) and is significantly reduced relative to the activity conferred by the copurified wild-type proteins (1+2) (P<0.01). Similarly, the specific activity of the 1+2EQ NBD combination is significantly less than that of the 1+2 combination (P<0.001), if ATPase activity is measured as the production of [γ-32P]Pi from [γ-32P]ATP using TLC (Figures 3C and 3D). Together, these findings suggest that Glu1371 normally plays an essential role in mediating ATPase activity conferred by the functional complex of NBD1 plus NBD2. Furthermore, we did not detect the production of [γ-32P]ADP for either the wild-type or 1+2EQ mutant pair, confirming that the NBD heterodimer is functional as an ATPase rather than a kinase, a possibility raised in recent studies by Gross et al. [21]. In Figure 3(E), we show the results of comparative studies of the specific ATPase activity of NBD2, co-purified wild-type NBD1 (1+2, n=5) and co-purified NBD1S573E and NBD2 (1SE+2, n=3). In this case, there was no significant difference (P<0.05) between the co-purified mutant (1SE+2) and the wild-type combination. These results suggest that the introduction of a glutamate residue into the non-conserved Walker B motif of NBD1 does not confer an additional active site.

Figure 3. Walker B mutant in NBD2 inhibits ATPase activity of NBD1–NBD2 heterodimer.

(A) Phosphoimages showing separation of radiolabelled ADP ([α-32P]ADP) from [α-32P]ATP or ATPase activity by TLC. ATPase activity is greater by purified NBD1–NBD2 than by isolated NBD1 and NBD1–NBD2E1371Q. (B) The histogram shows the means±S.E.M. of the ATPase activity of NBD1 (solid black bar), NBD1–NBD2 (hatched bar), and NBD1–NBD2E1371Q (grey bar). NBD1 was purified from three different reconstitutions, NBD1–NBD2 from five reconstitutions, and NBD1–NBD2E1371Q from three reconstitutions. ATPase activities (duplicates for each preparation), conferred by 1 μg of total NBD protein, were determined in the presence of 1 mM ATP, 2 h after initiation of the reaction. These values were corrected for background, by subtraction of activity determined in reaction mixtures containing 1 μg of BSA instead of the CFTR NBDs. The activity conferred by the NBD1–NBD2 was significantly greater than that measured for either NBD1 (*P=0.0023) or NBD1–NBD2E1371Q (**P=0.0073). (C) Phosphoimages showing comparative measurement of ATPase activity as the generation of radiolabelled ADP ([α-32]ADP) from [α-32P]ATP or as the generation of radiolabelled Pi [γ-32P]Pi from [γ-32P]ATP. (D) The histogram shows that the ATPase activity (measured as [γ-32P]Pi production) is decreased in the heterodimer containing the 2EQ mutant (grey bar, with mean and S.E.M.) relative to the wild-type heterodimer (hatched bar) in three paired studies (P<0.001). (E) The histogram shows that the ATPase activity conferred by NBD1S573E–NBD2 (grey bar) is similar to that conferred by NBD1–NBD2 (white bar) (P>0.05, n=3).

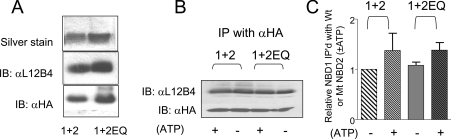

It is possible that the inability of co-purified NBD1 plus NBD2E1371Q to reconstitute the ATPase activity normally conferred by the 1+2 NBD heterodimer reflects a defect in the association of the mutant NBD2 with NBD1 rather than loss of an active site. In Figure 4(A), we show that NBD2E1371Q can be co-purified with NBD1. The top panel shows the abundance of total NBD protein purified from each co-expression. Each silver stain band reports the purification of both NBD1 and NBD2 (mutant or wild-type) as their masses cannot be effectively resolved by SDS/PAGE. Western-blot analysis of purified proteins using the NBD1-specific antibody (L12B4, middle panel) or an anti-HA antibody directed against the tag inserted before NBD2 (lower panel), revealed that both NBDs are present in the purification. These findings support the idea that these proteins form a complex in vitro.

Figure 4. Walker B-NBD2 mutant associates with NBD1.

(A) NBD1 (1) co-expressed in Sf9 cells with NBD2 (2) or NBD2E1371Q (1+2EQ). The top panel shows silver-stained purified NBDs analysed by SDS/PAGE. The different domains cannot be distinguished on the basis of migration. The middle panel shows expression of NBD1 in this purified protein by immunoblotting with NBD1-specific antibody (L12B4). The bottom panel shows the expression of NBD2NBD2EQ by immunoblotting using an anti-HA antibody. (B) NBD1 can be co-immunoprecipitated with NBD2 or NBD2EQ using an anti-HA antibody directed against the engineered tag in NBD2. Cellular ATP concentration was reduced in vivo (−) by replacing glucose in the medium with deoxyglucose and treating the cells with rotenone as described in the Methods section. NBDs harvested from Sf9 cells grown in glucose-replete medium were incubated with 1 mM MgATP prior to immunoprecipitation to optimize nucleotide interaction with these proteins. (C) The ratio of NBD1 immunoprecipitated with NBD2 was determined for three independent trials. The histogram shows the mean±S.E.M. of ratios normalized relative to the ratio determined for wild-type NBDs (1+2) in ATP-depleted cells. There was no significant difference between any of these groups.

In order to determine whether both the NBD2E1371Q and NBD2 are capable of associating with NBD1 in vivo, we evaluated the co-immunoprecipitation of either protein with NBD1 from the supernatant of freshly disrupted Sf9 cells. The NBD1-specific antibody, L12B4, is effective in immunoprecipitating soluble NBD1 and co-immunoprecipitating either soluble NBD2 or NBD2E1371Q (results not shown).

Conversely, we immunoprecipitated HA-tagged NBD2 proteins from the supernatant of freshly dissociated Sf9 cells using an anti-HA tag antibody and probed for the co-precipitation of NBD1 using the NBD1-specific antibody L12B4 (Figure 4B). The association of NBD2 proteins with NBD1 was measured as the ratio of the L12B4 and anti-HA immunoreactive protein. As shown in the histogram in Figure 4(C), there was no significant difference between the association between NBD1 and NBD2 and the association between NBD1 and NBD2E1371Q. These results suggest that the decrease in ATPase activity by the wild-type NBD heterodimer and the mutant (EQ) NBD heterodimer likely reflects a critical role for Glu1371 in this activity rather than the alteration in domain–domain interaction.

Interestingly, there was no significant effect of ATP depletion on the association of NBD1 with either NBD2 or NBD2E1371Q. Based on previous biochemical and structural studies of prokaryotic ABC NBDs, we predicted that a relatively tight ATP sandwich would be formed by the catalytically impaired NBD1–NBD2E1371Q heterodimer [23,24]. However, using two different approaches, i.e. supplementing the soluble domains in freshly prepared Sf9 supernatant with 1 mM MgATP (results not shown) or by inducing ATP depletion in Sf9 cells prior to lysis, we failed to detect an effect of modifying ATP levels on the abundance of NBD1 co-immunoprecipitated with either NBD2 or NBD2E1371Q. The lack of a significant effect of ATP depletion on NBD co-precipitation is shown in Figures 4(B) and 4(C). These results suggest that heterodimerization of the NBDs of CFTR may not require ATP binding.

DISCUSSION

These findings provide direct evidence supporting a key role for the Walker B glutamate residue, Glu1371 in NBD2 in mediating ATPase activity by the NBD heterodimer of CFTR. Further, as the mutation of this residue abrogates ATPase activity conferred by the heterodimer, our results support the model wherein there is only one catalytic site formed by the functional complex. According to molecular modelling [25,26], electrophysiological evaluations of nucleotide-dependent gating [11,18,27] and biochemical work [15,19] including the present study, this active site is likely comprised of the Walker A and B motifs of NBD2, the H switch of NBD2 and the signature motif of NBD1 (Figure 1).

The other nucleotide-binding site in the heterodimer is comprised of the Walker A and B of NBD1, the ‘H-switch’ of NBD1 and the signature motif of NBD2. This site not only lacks the conserved glutamate residue in Walker B, but also lacks conservation in the signature motif and the histidine normally conserved in the ‘H’ switch (Figure 1). Our finding that introduction of the canonical glutamate residue into Walker B of NBD1 fails to confer additional ATPase activity, suggests that this glutamate substitution is not sufficient to rescue catalytic activity at this site. Future studies will evaluate the relative consequences of rescuing conservation in the signature sequence in NBD2 as well as the ‘H-switch’ motif in NBD1 on ATPase activity by the heterodimer [26,28,29].

In the present studies, we detected ATPase activity by the NBD heterodimer using two methods, evaluation of the production of radiolabelled ADP ([α-32P]ADP from [α-32P]ATP) as well as the evaluation of radiolabelled Pi [γ-32P]Pi from [γ-32P]ATP. In both cases, we measured comparable levels of ATPase activity (Figure 3), confirming our previous enzymatic studies of these proteins [14]. A recent report by Gross et al. [21] used the second method to assess the ATPase activities of the heterodimer of NBD1 plus NBD2 of CFTR. Interestingly, they could not detect ATPase activity in their preparation. Therefore it is likely essential that the two domains be either co-expressed or co-reconstituted in order to form a functional complex as in our previous work [14] and the present study, rather than added to one another as separately folded domains as in the Gross paper [21].

As previously mentioned there is compelling evidence from electrophysiological and biochemical studies supporting the idea that the NBDs of CFTR interact in the context of the full-length protein [15,18,19,30,31]. Previously, we showed that NBD1 and NBD2, expressed and purified singly, could be combined and functionally reconstituted as a heterodimer [14]. However, the present studies are the first to show that isolated NBD1 and NBD2 domains interact in vivo following their co-expression, in the absence of the ‘R’ domain and the MSDs. Specifically, we found that soluble NBD1 and NBD2 can be co-immunoprecipitated from freshly disrupted Sf9 cells. Interestingly, we could not detect a significant difference in the association between wild-type NBD1 and NBD2 and the association between NBD1 and NBD2(E1371Q) following ATP depletion in cell culture prior to cell lysis (with the removal of extracellular glucose, and the addition of deoxyglucose and rotenone). In light of the recent studies by Vergani et al. [30] showing that ATP binding induced hydrogen bond formation between NBD1 and NBD2 in the vicinity of the ‘catalytic site’, we predicted that the most stable interaction may have occurred between NBD1 and NBD2-(E1371Q) in ATP-replete cells. We suggest therefore that the above methods for ATP depletion may have been ineffective in removing ATP from its binding site(s). This is not surprising given the high concentrations of intracellular ATP of 4–5 mM. Further, we suggest that the NBDs of CFTR (even the isolated domains) may interact regardless of the level of catalytic activity. Alternatively, the immunoprecipitation methods employed in the current studies fail to report subtle changes in the stability of this interaction.

The functional interaction between the NBDs is likely to be affected by modifications in other regions of the protein. Biochemical studies of full-length CFTR and other ABC proteins [32,33] as well as its related proteins, MRP (multidrug-resistance protein) [34] and P-glycoprotein [35–38], reveal that there is cross-talk between the MSDs and the NBDs. For example, the specific activity of the full-length CFTR protein is approx. 3–5-fold higher than that exhibited by the NBD1–NBD2 heterodimer alone [14,19,20]. Conversely, pore blockers of CFTR, which bind to regions in the membrane domain have been shown to inhibit ATPase activity of the full-length protein [32]. It has been well documented that the substrates of the multidrug resistance proteins P-glycoprotein and MRP (multidrug-resistance protein), which interact with the membrane domain modify the ATPase activity of these proteins. Therefore the challenge for future work is to understand the molecular basis for modification of the ATPase activity by the NBD heterodimer and by other regions of the protein, i.e. the R domain and possibly the intracellular loops connecting the transmembrane helices of CFTR.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an operating grant awarded to C. E. B. by the Canadian Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. F. L. L. S. was the recipient of a CIHR (Canadian Institutes of Health Research) Fellowship Award (Strategic Training Program for the Study of Membrane Proteins and Disease). J. C. C. is a recipient of a Restracomp (Hospital for Sick Children, Research Training Competition) Fellowship Award.

References

- 1.Higgins C. F. ABC transporters: physiology, structure and mechanism – an overview. Res. Microbiol. 2001;152:205–210. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(01)01193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Higgins C. F., Linton K. J. Structural biology. The xyz of ABC transporters. Science. 2001;293:1782–1784. doi: 10.1126/science.1065588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Csanady L., Seto-Young D., Chan K. W., Cenciarelli C., Angel B. B., Qin J., McLachlin D. T., Krutchinsky A. N., Chait B. T., Nairn A. C., et al. Preferential phosphorylation of R-domain serine 768 dampens activation of CFTR channels by PKA. J. Gen. Physiol. 2005;125:171–186. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200409076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ostedgaard L. S., Baldursson O., Welsh M. J. Regulation of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator Cl− channel by its R domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:7689–7692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100001200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chappe V., Irvine T., Liao J., Evagelidis A., Hanrahan J. W. Phosphorylation of CFTR by PKA promotes binding of the regulatory domain. EMBO J. 2005;24:2730–2740. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chappe V., Hinkson D. A., Howell L. D., Evagelidis A., Liao J., Chang X. B., Riordan J. R., Hanrahan J. W. Stimulatory and inhibitory protein kinase C consensus sequences regulate the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:390–395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0303411101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang X. B., Tabcharani J. A., Hou Y. X., Jensen T. J., Kartner N., Alon N., Hanrahan J. W., Riordan J. R. Protein kinase A (PKA) still activates CFTR chloride channel after mutagenesis of all 10 PKA consensus phosphorylation sites. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:11304–11311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seibert F. S., Chang X. B., Aleksandrov A. A., Clarke D. M., Hanrahan J. W., Riordan J. R. Influence of phosphorylation by protein kinase A on CFTR at the cell surface and endoplasmic reticulum. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1461:275–283. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(99)00163-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riordan J. R., Rommens J. M., Kerem B., Alon N., Rozmahel R., Grzelczak Z., Zielenski J., Lok S., Plavsic N., Chou J. L., et al. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: cloning and characterization of complementary DNA. Science. 1989;245:1066–1073. doi: 10.1126/science.2475911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rowe S. M., Miller S., Sorscher E. J. Cystic fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:1992–2001. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gadsby D. C., Vergani P., Csanady L. The ABC protein turned chloride channel whose failure causes cystic fibrosis. Nature. 2006;440:477–483. doi: 10.1038/nature04712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kidd J. F., Kogan I., Bear C. E. Molecular basis for the chloride channel activity of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator and the consequences of disease-causing mutations. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2004;60:215–249. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(04)60007-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riordan J. R. Assembly of functional CFTR chloride channels. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2005;67:701–718. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.032003.154107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kidd J. F., Ramjeesingh M., Stratford F., Huan L. J., Bear C. E. A heteromeric complex of the two nucleotide binding domains of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) mediates ATPase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:41664–41669. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407666200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aleksandrov L., Mengos A., Chang X., Aleksandrov A., Riordan J. R. Differential interactions of nucleotides at the two nucleotide binding domains of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:12918–12923. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100515200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hopfner K. P., Karcher A., Shin D. S., Craig L., Arthur L. M., Carney J. P., Tainer J. A. Structural biology of Rad50 ATPase: ATP-driven conformational control in DNA double-strand break repair and the ABC-ATPase superfamily. Cell. 2000;101:789–800. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80890-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Locher K. P., Lee A. T., Rees D. C. The E. coli BtuCD structure: a framework for ABC transporter architecture and mechanism. Science. 2002;296:1091–1098. doi: 10.1126/science.1071142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vergani P., Basso C., Mense M., Nairn A. C., Gadsby D. C. Control of the CFTR channel's gates. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2005;33:1003–1007. doi: 10.1042/BST20051003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramjeesingh M., Li C., Garami E., Huan L. J., Galley K., Wang Y., Bear C. E. Walker mutations reveal loose relationship between catalytic and channel-gating activities of purified CFTR (cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator) Biochemistry. 1999;38:1463–1468. doi: 10.1021/bi982243y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li C., Ramjeesingh M., Wang W., Garami E., Hewryk M., Lee D., Rommens J. M., Galley K., Bear C. E. ATPase activity of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:28463–28468. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.45.28463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gross C. H., Abdul-Manan N., Fulghum J., Lippke J., Liu X., Prabhakar P., Brennan D., Willis M. S., Faerman C., Connelly P., et al. Nucleotide-binding domains of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator, an ABC transporter, catalyze adenylate kinase activity but not ATP hydrolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:4058–4068. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511113200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Srinivasan G., Post J. F., Thompson E. B. Optimal ligand binding by the recombinant human glucocorticoid receptor and assembly of the receptor complex with heat shock protein 90 correlate with high intracellular ATP levels in Spodoptera frugiperda cells. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1997;60:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(96)00182-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moody J. E., Millen L., Binns D., Hunt J. F., Thomas P. J. Cooperative, ATP-dependent association of the nucleotide binding cassettes during the catalytic cycle of ATP-binding cassette transporters. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:21111–21114. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200228200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu G., Westbrooks J. M., Davidson A. L., Chen J. ATP hydrolysis is required to reset the ATP-binding cassette dimer into the resting-state conformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:17969–17974. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506039102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Callebaut I., Eudes R., Mornon J. P., Lehn P. Nucleotide-binding domains of human cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator: detailed sequence analysis and three-dimensional modeling of the heterodimer. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2004;61:230–242. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3386-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eudes R., Lehn P., Ferec C., Mornon J. P., Callebaut I. Nucleotide binding domains of human CFTR: a structural classification of critical residues and disease-causing mutations. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2005;62:2112–2123. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5224-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berger A. L., Ikuma M., Welsh M. J. Normal gating of CFTR requires ATP binding to both nucleotide-binding domains and hydrolysis at the second nucleotide-binding domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:455–460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408575102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zaitseva J., Jenewein S., Jumpertz T., Holland I. B., Schmitt L. H662 is the linchpin of ATP hydrolysis in the nucleotide-binding domain of the ABC transporter HlyB. EMBO J. 2005;24:1901–1910. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zaitseva J., Jenewein S., Wiedenmann A., Benabdelhak H., Holland I. B., Schmitt L. Functional characterization and ATP-induced dimerization of the isolated ABC-domain of the haemolysin B transporter. Biochemistry. 2005;44:9680–9690. doi: 10.1021/bi0506122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vergani P., Lockless S. W., Nairn A. C., Gadsby D. C. CFTR channel opening by ATP-driven tight dimerization of its nucleotide-binding domains. Nature. 2005;433:876–880. doi: 10.1038/nature03313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Powe A. C., Jr, Al-Nakkash L., Li M., Hwang T. C. Mutation of Walker-A lysine 464 in cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator reveals functional interaction between its nucleotide-binding domains. J. Physiol. 2002;539:333–346. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kogan I., Ramjeesingh M., Huan L. J., Wang Y., Bear C. E. Perturbation of the pore of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) inhibits its ATPase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:11575–11581. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010403200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kogan I., Ramjeesingh M., Li C., Kidd J. F., Wang Y., Leslie E. M., Cole S. P., Bear C. E. CFTR directly mediates nucleotide-regulated glutathione flux. EMBO J. 2003;22:1981–1989. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deeley R. G., Cole S. P. Substrate recognition and transport by multidrug resistance protein 1 (ABCC1) FEBS Lett. 2006;580:1103–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharom F. J., Lugo M. R., Eckford P. D. New insights into the drug binding, transport and lipid flippase activities of the p-glycoprotein multidrug transporter. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2005;37:481–487. doi: 10.1007/s10863-005-9496-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qu Q., Chu J. W., Sharom F. J. Transition state P-glycoprotein binds drugs and modulators with unchanged affinity, suggesting a concerted transport mechanism. Biochemistry. 2003;42:1345–1353. doi: 10.1021/bi0267745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Callaghan R., Ford R. C., Kerr I. D. The translocation mechanism of P-glycoprotein. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:1056–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.11.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rothnie A., Storm J., McMahon R., Taylor A., Kerr I. D., Callaghan R. The coupling mechanism of P-glycoprotein involves residue L339 in the sixth membrane spanning segment. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:3984–3990. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]