Abstract

The eIF4E and eIF(iso)4E cDNAs from several genotypes of lettuce (Lactuca sativa) that are susceptible, tolerant, or resistant to infection by Lettuce mosaic virus (LMV; genus Potyvirus) were cloned and sequenced. Although Ls-eIF(iso)4E was monomorphic in sequence, three types of Ls-eIF4E differed by point sequence variations, and a short in-frame deletion in one of them. The amino acid variations specific to Ls-eIF4E1 and Ls-eIF4E2 were predicted to be located near the cap recognition pocket in a homology-based tridimensional protein model. In 19 lettuce genotypes, including two near-isogenic pairs, there was a strict correlation between these three allelic types and the presence or absence of the recessive LMV resistance genes mo11 and mo12. Ls-eIF4E1 and mo11 cosegregated in the progeny of two separate crosses between susceptible genotypes and an mo11 genotype. Finally, transient ectopic expression of Ls-eIF4E restored systemic accumulation of a green fluorescent protein-tagged LMV in LMV-resistant mo12 plants and a recombinant LMV expressing Ls-eIF4E° from its genome, but not Ls-eIF4E1 or Ls-eIF(iso)4E, accumulated and produced symptoms in mo11 or mo12 genotypes. Therefore, sequence correlation, tight genetic linkage, and functional complementation strongly suggest that eIF4E plays a role in the LMV cycle in lettuce and that mo11 and mo12 are alleles coding for forms of eIF4E unable or less effective to fulfill this role. More generally, the isoforms of eIF4E appear to be host factors involved in the cycle of potyviruses in plants, probably through a general mechanism yet to be clarified.

Disease is a remarkable but exceptional outcome of the interaction between a plant and a microorganism: In most cases, microorganisms are excluded by active or passive host defenses. Two well-known active defense mechanisms of plants against pathogen attack are the hypersensitive reaction (Pontier et al., 1998) and, in the case of viruses, RNA-mediated defense (Ratcliff et al., 1997; Voinnet, 2001). However, in the most common situation, a given plant is simply not a suitable biological substrate for the multiplication of a given microorganism, resulting in passive resistance. In the case of obligatory parasites such as viruses, absence or inadequacy of a single host factor may lead to the inability for the pathogen to multiply in the host or to systemically invade it (Ishikawa et al., 1997; Yamanaka et al., 2000). Such a mechanism implies that the dominant alleles of the host genes involved would be associated with susceptibility and the recessive alleles encoding nonfunctional versions of this host factor with resistance. Identification of recessive genes implicated in plant resistance to viruses, therefore, should provide a better knowledge of the molecular mechanisms involved in compatible interactions between a host plant and a virus.

There are many instances where recessive resistance genes are used to control agronomically important pathogens, especially potyviruses for which they have even been estimated to represent about 40% of the known resistance genes (Provvidenti and Hampton, 1992). Potyvirus is the largest and most diverse genus of plant viruses and causes severe losses to many crops, particularly to vegetables (Shukla et al., 1994). Potyviruses are efficiently transmitted by aphids, and some of them are also seed borne. Their flexuous particles contain a single genomic RNA molecule of about 10,000 nucleotides, encoding a polyprotein that is processed by three virus-encoded proteinases (Reichmann et al., 1992). The viral RNA is polyadenylated at its 3′ end, and its 5′ end is not capped but covalently linked to a virus-encoded protein of about 25 kD, named VPg (Murphy et al., 1990).

In several potyviruses, the central domain of the VPg is involved in the ability to overcome resistances associated with recessive genes. However, the phenotypes of the corresponding resistances differ depending on the host and potyvirus partners. For instance, the central domain of VPg has been shown to be involved in the control of Pea seedborne mosaic virus accumulation in single cells by the pea (Pisum sativum) sbm-1 gene (Keller et al., 1998), in the prevention of Tobacco vein mottling virus cell-to-cell movement by the tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) va gene (Gibb et al., 1989), and in the block of Tobacco etch virus (TEV) long-distance movement by two recessive genes present in the tobacco genotype V20 (Schaad and Carrington, 1996; Schaad et al., 1996).

Whatever the mechanism(s) involved in these different resistance phenotypes, it has been speculated that VPg carries out some of its functions in the viral cycle by interacting with host factors. In the yeast two-hybrid system and in other in vitro assays, the VPg of Turnip mosaic virus (TuMV) and of TEV interact with the eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIF4E and its isoform eIF(iso)4E from Arabidopsis, tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum), and tobacco (Wittmann et al., 1997; Léonard et al., 2000; Schaad et al., 2000). eIF4E is a cap-binding protein, and its main role in eukaryotic mRNA translation is to recruit the eIF4F complex near the 5′ cap structure and allow additional translation factors to be recruited, resulting in mRNA circularization and translation initiation (Pestova et al., 2001). In Arabidopsis, eIF4E is 52% identical in amino acid sequence to eIF(iso)4E, and both are about 70% identical to their respective wheat (Triticum aestivum) homologs (Rodriguez et al., 1998). Differences in transcription patterns (Rodriguez et al., 1998) and in binding affinities (Carberry et al., 1991) suggest that these isoforms might have complementary biological roles.

Conceptually, as it does for cellular mRNAs, eIF4E could participate in potyvirus RNA translation by interacting with the 5′ VPg that replaces a 5′ cap structure in these RNAs. A point mutation in the TuMV VPg that abolishes its interaction with eIF(iso)4E is associated with a loss of viral infectivity (Léonard et al., 2000). Furthermore, it has been shown recently that disruption of the eIF(iso)4E gene of Arabidopsis results in resistance to three potyviruses (TEV, TuMV, and LMV; Duprat et al., 2002; Lellis et al., 2002) and that the natural recessive resistance to TEV and Potato virus Y (PVY) in pepper (Capsicum annuum) conferred by the recessive gene pvr2 is associated with sequence variation in eIF4E (Ruffel et al., 2002).

In lettuce (Lactuca sativa), the recessive mo11 and mo12 genes are associated with reduced accumulation and lack of symptoms (tolerance) or absence of accumulation (resistance) of common isolates of the potyvirus Lettuce mosaic virus (LMV; Ryder, 1970; Dinant and Lot, 1992). The issue of the interaction, resistance or tolerance, depends on the virus isolate and genetic background (Pink et al., 1992; Revers et al., 1997), but mo11 is generally associated with resistance and mo12 with tolerance (Bos et al., 1994; Revers et al., 1997). The genes mo11 and mo12 are tightly linked and probably alleles (Ryder, 1970; Pink et al., 1992). The ability of some LMV isolates to successfully infect and produce symptoms in lettuce genotypes with mo11 or mo12 is associated to a central region of the viral genome encoding the C terminus of the CI protein, VPg, and the N terminus of the NIa proteinase (Redondo et al., 2001).

We have investigated the possible role of eIF4E and eIF(iso)4E in the compatibility between lettuce and LMV. For this purpose, eIF4E and eIF(iso)4E cDNAs were sequenced from a set of susceptible, tolerant, or resistant lettuce genotypes, the genetic cosegregation between mo11 and eIF4E was tested, and the ability of ectopically expressed eIF4E to functionally restore full LMV susceptibility in tolerant or resistant lettuce genotypes was evaluated.

RESULTS

Cloning and Sequence Analysis of the Lettuce eIF4E and eIF(iso)4E cDNAs

A multiple alignment of the nucleotide sequences of the eIF4E coding regions from different plant species and of their human (Homo sapiens) and murine (Mus musculus) counterparts revealed a higher degree of conservation in the central domain of each of these proteins than in the N- and C-terminal regions (data not shown). The central region of the eIF4E cDNA from the susceptible lettuce genotype Salinas was PCR amplified using oligonucleotides 4E193f and 4E408r (all oligonucleotide sequences are given in the “Materials and Methods” section), designed in reference to seven plant eIF4E sequences, including three sequences in Arabidopsis. This product was cloned, and all of the eight clones sequenced yielded the same 169-bp sequence. This sequence information was used to design the oligonucleotides Ls4E250f and Ls4E255r for 3′- and 5′-RACE amplification of the cDNA ends, respectively. Finally, the oligonucleotides Ls4E3f and Ls4E813r were used to PCR amplify the nearly full-length eIF4E cDNA, including the entire coding region, before cloning in pGEM-T Easy and sequencing. The assembled eIF4E cDNA nucleotide sequence was determined from at least five independent clones at each position. No variability was observed between the cDNA clones sequenced. The full-length sequence (GenBank accession no. AF530162) was 1,032 nucleotides in length, with a single open reading frame from positions 21 to 710, encoding a protein with a calculated molecular mass of 26.1 kD (Fig. 1). The closest matches obtained after a BLAST search in GenBank with the full-length nucleotide sequence were the eIF4E cDNAs from tomato (accession no. AF259801, E = 5.10–27), rice (Oryza sativa; U34597, E = 5.10–27) and Arabidopsis (Y10548, E = 8.10–26), and the closest matches with the predicted translation product were the eIF4E amino acid sequences from Arabidopsis (E = 3.10–81), tomato (E = 3.10–80), and maize (Zea mays; AF076954, E = 4.10–78), confirming that the cDNA cloned was the eIF4E cDNA. The identity between the predicted amino acid sequence and 11 eIF4E sequences from plants, vertebrates, and insects ranged between 40% and 70% (data not shown).

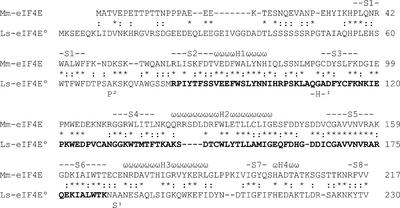

Figure 1.

Amino acid sequence alignment of murine and lettuce eIF4E. The amino acid sequence of the eIF4E proteins from mouse (Mm-eIF4E) and the lettuce genotype Salinas (Ls-eIF4E) were aligned using ClustalW (Thompson et al., 1994). Asterisks, Identical amino acids; semicolons, similar amino acids; hyphens, deletions in one sequence compared with the other. The structural elements of Mm-eIF4E, as determined by x-ray crystallography (Marcotrigiano et al., 1997), are indicated: S1 to S8, eight beta-sheets (delineated with hyphens); and H1 to H4, four alpha-helices (delineated with omegas). The amino acids differing in Ls-eIF4E1 (1) and Ls-eIF4E2 (2) are shown below the Ls-eIF4E° sequence. The central domain of Ls-eIF4E, sequenced for 11 additional genotypes as described in the text, is shown in bold font. Amino acids are numbered on the right.

Similarly, a near full-length eIF(iso)4E cDNA was obtained from the susceptible genotype Salinas by a combination of 3′- and 5′-RACE PCR. The 3′ region of the cDNA was amplified by PCR using an oligo(dT)-containing primer and the degenerate oligonucleotide 4E198f, designed from a conserved central region of the eIF4E genes from tomato, tobacco, and Arabidopsis. The oligonucleotide Ls(iso)4E680r was designed from the sequence of the 3′-RACE product and used in the 5′-RACE system (Invitrogen) to amplify the complete cDNA lacking the 3′ non-coding region. The 5′RACE products were cloned into pGEM-T Easy and sequenced. The assembled sequence (GenBank accession no. AF530163) contained a single open reading frame encoding a protein of 193 amino acids with a calculated molecular mass of 22.0 kD. The closest matches obtained after a BLAST search in GenBank with the full-length nucleotide sequence were the eIF(iso)4E cDNAs from wheat (accession no. M95819, E = 6.10–20), Arabidopsis (Y10547, E = 2.10–13), and maize (AF076955, E = 5.10–8), and the closest matches with the predicted translation product were the eIF(iso)4E amino acid sequences from wheat (M95819, E = 7.10–77), rice (AAK27811, E = 8.10–70), and maize (AF076955, E = 1.10–69), confirming that the cDNA cloned was the eIF(iso)4E cDNA.

The eIF4E and eIF(iso)4E coding regions were 55.3% identical in nucleotide sequence and 46.8% identical in amino acid sequence. Similar levels of identity in nucleotide and amino acid sequences between the isoforms of eIF4E were found in Arabidopsis (53.9% and 41.2%, respectively), maize (62.9% and 48.9%), rice (59.9% and 46.5%), and wheat (60.2% and 47.7%).

Correlation between Sequence Variations in the eIF4E cDNA and the Presence of mo11 or mo12

The region encompassing nucleotide positions 20 to 787, which includes the entire coding region of the eIF4E cDNA, was PCR amplified as described above, cloned, and sequenced for the seven additional lettuce genotypes Floribibb (mo11), Mantilia (mo11), Malika (mo11), Salinas 88 (mo12), Vanguard (susceptible), Vanguard 75 (mo12), and 87-20M (susceptible). All sequences were highly conserved, but some of them contained mutations when compared with the sequence from Salinas (Table I; Fig. 1). On the basis of their patterns of variation, the sequences were classified into three types. Type 0 sequences (Vanguard and 87-20M) have coding regions identical to that found in Salinas. Type 1 sequences (Floribibb, Malika, and Mantilia) have a silent C to T substitution at position 299, a deletion of nucleotides 344 to 349, and a non-silent G to T substitution at position 576. Type 2 sequences (Salinas 88 and Vanguard 75) have a non-silent G to C substitution at position 228 and a C to T substitution at position 730 in the 3′-non-coding region. This last sequence variation was also found in the susceptible genotype 87-20M. Types 0, 1, and 2 of lettuce eIF4E were named Ls-eIF4E°, Ls-eIF4E1, and Ls-eIF4E2, respectively.

Table I.

Sequence differences in the eIF4E cDNAs of 19 lettuce genotypes

For each genotype, the nucleotides that differed from the sequence of eIF4E of the genotype Salinas (as a reference: GenBank accession no. AF530162) are indicated with the corresponding amino acid changes. Nucleotides and amino acids identical to those of genotype Salinas at a given position are shown with hyphens. For the genotypes labeled with an asterisk, the nucleotide sequence was determined only between positions 109 and 412 and, therefore, not at the positions marked with two asterisks. Nucleotide 730 is in the 3′-non-coding region; therefore, designation of the corresponding amino acid does not apply (n.a.). On the basis of these amino acid differences, the sequences were classified in three types as indicated on the left.

| Genotypes

|

Nucleotide/Amino Acid Positions

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 228/70

|

299/93

|

344-349/108-110

|

576**/186

|

730**/n.a.

|

||||||

| Nucleotides | Amino acids | Nucleotides | Amino acids | Nucleotides | Amino acids | Nucleotides | Amino acids | Nucleotides | Amino acids | |

| Type 0 | ||||||||||

| Salinas, Fiona*, Girelle*, Jessy*, Mariska*, Trocadéro*, Vanguard | G | Ala | C | Phe | AGGAGC | QGA | G | Ala | C | n.a. |

| 87-20M | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | T | - |

| Type 1 | ||||||||||

| Alizé*, Classic*, Floribibb, Malika, Mantilia, Oriana*, Presidio* | - | - | T | Phe | (Deletion) | His | T | Ser | - | - |

| Type 2 | ||||||||||

| Autumn Gold*, Desert Storm*, Salinas 88, Vanguard 75 | C | Pro | - | - | - | - | - | - | T | - |

Therefore, within this limited set of eight lettuce genotypes, there was a strict correlation between Ls-eIF4E1 and the presence of mo11 and between Ls-eIF4E2 and the presence of mo12, whereas the susceptible genotypes all had Ls-eIF4E°. This correlation was maintained even in the case of two independent pairs of genotypes nearly isogenic for mo12, Salinas, and Salinas 88 on one hand, and Vanguard and Vanguard 75 on the other hand. To confirm and extend this correlation, the central domain of the Ls-eIF4E cDNA from 11 additional lettuce genotypes was PCR amplified using oligonucleotides Ls4E83f and Ls4E442r and sequenced (Table I). Again, a complete correlation was observed in this central region between the type of Ls-eIF4E and the presence of mo11 or mo12 in the following genotypes: Fiona, Girelle, Jessy, and Mariska (Ls-eIF4E°, susceptible), Alizé, Classic, Oriana, and Presidio (Ls-eIF4E1 and mo11), and Autumn Gold and Desert Storm (Ls-eIF4E2 and mo12).

The sequence of the eIF(iso)4E coding region from the susceptible genotypes Salinas and Vanguard and from their nearly isogenic mo12 genotypes Salinas 88 and Vanguard 75 was also determined. No difference was detected between the eIF(iso)4E coding sequences from these four genotypes. An identical sequence was also found in the mo11 genotype Mantilia. This suggests that eIF(iso)4E sequence variations are not directly correlated with the mo1-related phenotypes.

Predicted Three-Dimensional (3D) Structure of the Ls-eIF4E Protein

A 3D model of the Ls-eIF4E protein was predicted based on the known 3D structures of human (Hs-eIF4E) and murine (Mm-eIF4E) cap-bound eIF4E molecules (Marcotrigiano et al., 1999; Tomoo et al., 2002). The central domain of Ls-eIF4E°, from beta-sheet 2 to beta-sheet 6 (Fig. 1), was 50% identical in sequence to that of Mm-eIF4E (Fig. 1) and Hs-eIF4E (data not shown), suggesting that a homology-based model of the Ls-eIF4E folding would be valid within the range of 1 Å (Chothia and Lesk, 1986). Two independent algorithms (Guex and Peitsch, 1997; Bates et al., 2001) yielded structurally similar predictions (data not shown). Using Swiss-model and Mm-eIF4E as a template, the Ls-eIF4E° central domain tightly matched that of Mm-eIF4E (root mean square [RMS] deviation = 0.74 Å) and Hs-eIF4E (RMS = 1.4 Å). When Hs-eIF4E was used as the modeling template, RMS deviation values obtained with Ls-eIF4E were 1.23 Å for Hs-eIF4E and 1.35 Å for Mm-eIF4E, respectively. Using the same procedure to predict the folding of Hs-eIF4E based on its homology with Mm-eIF4E yielded a model with a 0.96-Å RMS deviation compared with its actual x-ray diffraction structure, providing a landmark for comparison of RMS deviation values.

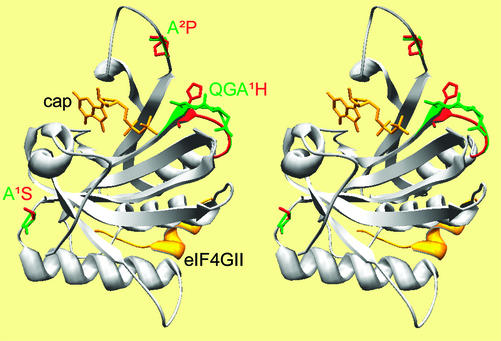

Figure 2 shows the predicted 3D structure of Ls-eIF4E° and, superimposed to visualize the predicted structural differences, those of Ls-eIF4E1 and Ls-eIF4E2. According to this model, the amino acids that differ between the three Ls-eIF4E types were all predicted to be at or near the surface of the protein. All mapped near the cap recognition pocket, on the face of eIF4E opposite to the eIF4G-binding site (Fig. 2). Ala-70-Pro, the only amino acid different between Ls-eIF4E° and Ls-eIF4E2, was predicted to be part of the loop between beta-sheets 1 and 2 (Marcotrigiano et al., 1997), which protrudes at the rim of the cap-recognition pocket itself (Fig. 2). The three amino acids Gln-108-Gly-109-Ala-110, replaced by a single His in Ls-eIF4E1, are located in the neighboring loop (Figs. 1 and 2), between alpha-helix 1 and beta-sheet 3. Although the replacement of three amino acids by a single one in Ls-eIF4E1 was predicted to have a strong effect on the folding of this loop (Fig. 2), the Ala-70-Pro replacement in Ls-eIF4E2 was only predicted to have a minor impact because of the already existing sterical constraints on the chain in this region (Fig. 2). Similarly, the Ala-186-Ser replacement in the loop between beta-sheet 6 and alpha-helix 3 in Ls-eIF4E1 was predicted to cause no detectable effect on the predicted folding (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Stereo view of the predicted 3D structure of Ls-eIF4E. The structure of Ls-eIF4E° was predicted based on its homology with Mm-eIF4E, using Swiss-model (Guex and Peitsch, 1997) and shown in a ribbon representation. The positions of the cap analog 7-methyl-GDP (cap, yellow) and an eIF4G-derived peptide (eIF4GII, yellow) are derived from those observed in a cocrystal of these molecules with the murine eIF4E (Marcotrigiano et al., 1999). At variable positions, the side chains of the amino acid present in Ls-eIF4E° are displayed in green, and those in Ls-eIF4E1 or Ls-eIF4E2 are in red (labeled X1Y and X2Y, respectively, where X is the residue in Ls-eIF4E° and Y in Ls-eIF4E1 or Ls-eIF4E2). At the variable positions, the ribbon is colored using the same code.

Genetic Cosegregation between the mo11 and Ls-eIF4E1 Loci

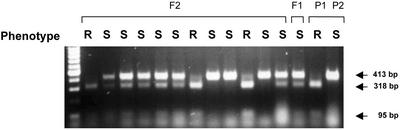

With the objective to strengthen the correlation between sequence variation in the eIF4E cDNA and LMV resistance controlled by mo11, the genetic linkage between mo11 and the six-nucleotide deletion found at positions 344 to 349 in Ls-eIF4E1 was studied in two F2 progenies Mariska (susceptible) × Mantilia (mo11) and Girelle (susceptible) × Mantilia (mo11). A cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence (CAPS) marker, eIF4E-PagI, was defined on the Ls-eIF4E cDNA in relation with the presence of a PagI restriction site generated by the six-nucleotide deletion in the Ls-eIF4E1 cDNA. Ten to 15 d after inoculation of 36 F2 plants with LMV-0, 10 plants showed no symptoms, whereas the remaining 26 presented typical mosaic symptoms caused by LMV. This ratio, 10 resistant to 26 susceptible, is consistent with the segregation of a single recessive gene coding for LMV resistance (χ2 = 0.15, P = 70%). Twenty-five of these F2 plants, eight without symptoms and 17 with typical LMV symptoms, were further analyzed for segregation of the CAPS marker eIF4E-PagI. A cDNA fragment of 442 to 448 bp was PCR generated using oligonucleotides Ls4E250f and Ls4E697r, designed on both sides of the six-nucleotide deletion present in Ls-eIF4E1. Electrophoretic analysis of PagI-digested PCR products revealed three distinct restriction patterns (Fig. 3; data not shown). All eight resistant plants showed a complete digestion of the PCR product, as in the Mantilia parent, and, thus, were determined to be homozygous for the presence of eIF4E-PagI. The five susceptible plants showed no detectable PagI digestion, as in the Mariska and Girelle parents, and, thus, were homozygous for the absence of eIF4E-PagI. Finally, the remaining 12 susceptible plants showed a partial digestion, as in the F1 plant, which was characteristic of individual plants heterozygous for eIF4E-PagI. Thus, a complete map cosegregation was observed between mo11-associated LMV resistance and the CAPS marker eIF4E-PagI.

Figure 3.

Cosegregation of the LMV resistance phenotype and Ls-eIF4E1 in the F2 progeny from a cross between Mantilia (mo11) and Mariska (susceptible). PCR products of 448 bp (442 bp for Ls-eIF4E1) were generated by reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR from RNAs isolated from leaves of the F2, F1, and the parental lines Mantilia (P1) and Mariska (P2) using oligonucleotides Ls4E250f and Ls4E697r. These cDNA fragments were digested by PagI and resolved in a 1.5% (w/v) agarose gel. Arrows indicate the molecular weights of the various fragments. The resistant (R) or susceptible (S) phenotype of each individual plant was scored in parallel 10 to 15 d after inoculation with LMV-0.

Agro-Infiltration of Ls-eIF4E Restores LMV Systemic Accumulation in mo12 Plants

Leaf infiltration with a suspension of Agrobacterium tumefaciens transformed with a binary plasmid containing an expression cassette between T-DNA borders (agro-infiltration) allows localized, transient expression of a foreign protein in plant tissues (Bechtold et al., 1993; Schöb et al., 1997). This strategy was used to evaluate the ability of Ls-eIF4E to restore LMV susceptibility in mo12 plants.

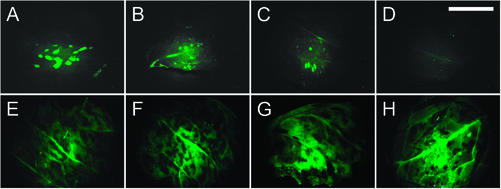

We have shown previously that mo12 prevents systemic accumulation of LMV-0-GFP, a green fluorescent protein-tagged LMV-0 (German-Retana et al., 2000; Candresse et al., 2002), but, unlike mo11, does not completely block replication in the inoculated leaf (German-Retana et al., 2000) and phloem loading (S. German-Retana, unpublished data). In our assay, lettuce plants were inoculated with LMV-0-GFP, and a few days later, their apical noninoculated leaves were agro-infiltrated with constructs designed to locally express Ls-eIF4E°, Ls-eIF4E1, or Ls-eIF4E2. A construct allowing the expression of the β-glucuronidase (GUS) was co-agro-infiltrated as an internal control. Six days after agro-infiltration, systemic accumulation of LMV-0-GFP, i.e. GFP accumulation in the noninoculated agro-infiltrated areas, was scored under UV light (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Functional complementation of the systemic accumulation of LMV-0-GFP in mo12 plants by transient Ls-eIF4E expression. GFP fluorescence stereomicroscopy was visualized in leaf areas of an mo12 (Salinas 88, A–D) and a susceptible (Salinas, E–H) genotype after co-agro-infiltration with constructs allowing expression of the GUS and Ls-eIF4E. A and E, Areas agro-infiltrated with a construct allowing expression of Ls-eIF4E°. B and F, Areas agro-infiltrated with a construct allowing expression of Ls-eIF4E1. C and G, Areas agro-infiltrated with a construct allowing expression of Ls-eIF4E2. D and H, Areas agro-infiltrated with the GUS construct only. Bar = 1 cm.

The pattern and timing of viral accumulation were not detectably changed in susceptible plants of the genotype Salinas in leaf areas upon agro-infiltration with any of the three types of Ls-eIF4E. Stereomicroscopic observation under UV light showed comparable GFP fluorescence intensity in Salinas leaves agro-infiltrated with the Ls-eIF4E°, Ls-eIF4E1, or Ls-eIF4E2 constructs (Fig. 4, E–G). GUS activity was readily detected in all infiltrated areas (data not shown), confirming the success of agro-infiltration for foreign protein expression.

In Salinas 88 (mo12), no systemic spread of GFP-tagged LMV-0 was observed up to 2 weeks after inoculation, as expected from previous results (Candresse et al., 2002). However, GFP fluorescence was observed in leaves distant from the inoculation sites that had been agro-infiltrated with any of the three forms of Ls-eIF4E (Fig. 4, A–C). The GUS construct alone did not restore the ability of LMV-0-GFP to infect these leaves (Fig. 4D). The size difference of the GFP spots that is apparent in Figure 4, A to C, was not considered significant because it was not reproduced from one leaf to another.

All three forms of Ls-eIF4E restored to some extent the ability of LMV-0-GFP to spread into agro-infiltrated areas distant from the inoculation site. To determine whether the Ls-eIF4E alleles differed quantitatively in this ability, we counted the GFP spots in each agro-infiltrated area (Table II). The analysis of the number of fluorescent spots confirmed the visual observation that all three types of Ls-eIF4E resulted in complementation for LMV-0-GFP systemic accumulation, both when the numbers of spots per agro-infiltrated area and the number of areas containing fluorescent spots were considered. For these two parameters, the χ2 probability for the random hypothesis was lower than 0.01%. However, the Ls-eIF4E types differed quantitatively in their abilities to restore the systemic accumulation of LMV-0-GFP. Although GFP accumulation was overall less efficient in agro-infiltrated areas of Salinas 88 leaves than in Salinas (Fig. 4), the number of GFP spots was higher after agro-infiltration with Ls-eIF4E° than it was with Ls-eIF4E1 or Ls-eIF4E2 (Table II). More areas were GFP positive after agro-infiltration with Ls-eIF4E° than with Ls-eIF4E1 (P = 3.05% for the random hypothesis) or Ls-eIF4E2 (P = 6.06%), and a significantly higher total number of spots was counted with Ls-eIF4E° than with Ls-eIF4E1 (P = 0.04%) or Ls-eIF4E2 (P = 2.91%). The apparent differences in efficiency of Ls-eIF4E1 and Ls-eIF4E2 to restore systemic viral accumulation (Table II) were not statistically supported (P = 75% for the number of GFP-positive areas and P = 21% for the number of spots). In summary, agro-infiltration of all three forms of Ls-eIF4E restored the LMV-0-GFP systemic accumulation in the mo12 genotype Salinas 88, and Ls-eIF4E° appeared to be more efficient than Ls-eIF4E1 and Ls-eIF4E2.

Table II.

Ls-eIF4E ectopic expression complements LMV-0-GFP accumulation in a mo12 context

After LMV-0-GFP inoculation, noninoculated upper leaves were agro-infiltrated with the constructs indicated on the left in addition to a GUS construct used as an internal control. The no. of areas containing GFP spots and the no. of GFP spots in each agro-infiltrated area, both reflecting LMV-0-GFP systemic accumulation, were counted using fluorescence stereomicroscopy. The results of three independent experiments were pooled.

| Construct

|

Agro-Infiltrated Areas

|

GFP Spots

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | No. containing GFP spots | Percent containing GFP spots | Total no. | Per agro-infiltrated area | |

| % | |||||

| pGreenII | 48 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0.02 |

| Ls-eIF4E0 | 67 | 35 | 52 | 136 | 2.0 |

| Ls-eIF4E1 | 55 | 18 | 33 | 33 | 0.6 |

| Ls-eIF4E2 | 59 | 21 | 36 | 51 | 0.9 |

Expression of Ls-eIF4E°, But Not Ls-eIF4E1, Restores the Infectivity of a Recombinant LMV in mo11 or mo12 Plants

To test the ability of Ls-eIF4E to restore LMV susceptibility in mo11 genotypes of lettuce, the infectivity of LMV-0-4E° was evaluated. This viral construct is derived from the nonresistance breaking isolate LMV-0 and contains the Ls-eIF4E° coding region as a translational fusion between the viral P1 and Hc-Pro domains that is proteolytically processed in vivo to yield the free proteins. Similarly, LMV-0-4E1 and LMV-0-iso4E contain the Ls-eIF4E1 and the Ls-eIF(iso)4E coding regions, respectively.

LMV-0-4E°, LMV-0-4E1, and LMV-0-iso4E were inoculated to three susceptible genotypes (Trocadéro, Salinas, and Vanguard), three mo11 genotypes (Floribibb, Malika, and Mantilia) and two mo12 genotypes (Salinas 88 and Vanguard 75), and symptoms were scored visually (Fig. 5; data not shown). As expected, LMV-0 caused symptoms only in the susceptible varieties. This was also the case of LMV-0-4E1 and LMV-0-iso4E. However, symptoms appeared in all plants inoculated with LMV-0-4E°. The timing of symptoms appearance in mo11 and mo12 genotypes inoculated with LMV-0-4E° was similar to that in susceptible plants infected with LMV-0: A faint vein clearing became evident in emerging leaves 10 to 12 d after inoculation, followed by mosaic symptoms 2 to 3 d later (data not shown).

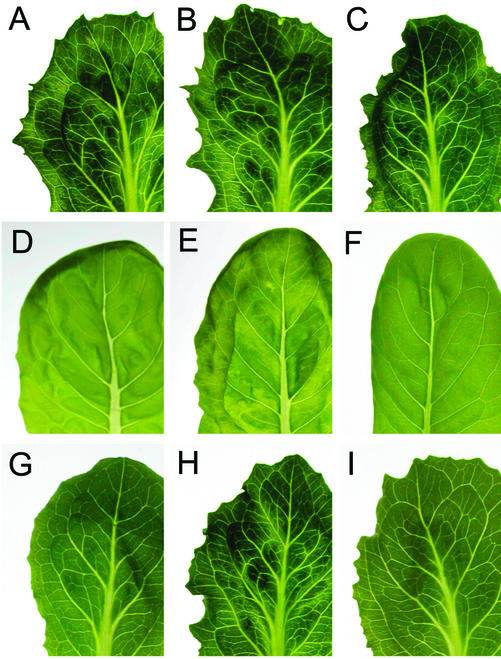

Figure 5.

LMV-0-4E° and LMV-0-4E1 symptoms in lettuce mo11 or mo12 genotypes. Lettuce seedlings were rub inoculated with LMV-0, LMV-0-4E°, or LMV-0-4E1, and detached leaves were photographed 3 weeks later. Lettuce genotypes are: A to C, Salinas (susceptible); D to F, Mantilia (mo11); and G to I, Salinas 88 (mo12). LMV constructs are: A, D, and G: LMV-0; B, E, and H: LMV-0-4E°; and C, F, and I: LMV-0-4E1.

Accumulation of LMV-0-4E°, LMV-0-4E1, and LMV-0-iso4E was assayed by ELISA (Table III; data not shown). The accumulation of nonrecombinant LMV was not detected in mo11 genotypes and was strongly reduced in mo12 genotypes compared with susceptible genotypes, consistent with the general idea that mo11 is associated with stronger LMV resistance than mo12. The same situation was observed for LMV-0-4E1 and LMV-iso4E, except no virus accumulation was detected in mo12 genotypes. On the other hand, LMV-0-4E° accumulated in all three categories of genotypes. These results, and the persistence of the Ls-eIF4E insert in the replicating virus during the course of the experiments, were confirmed by back inoculation and by RT-PCR (data not shown). LMV-0-4E° had a similar or slightly decreased accumulation in susceptible plants compared with nonrecombinant LMV, indicating that its ability to infect mo11 and mo12 plants was probably not due to a nonspecific enhancement of virus accumulation by the Ls-eIF4E° insert.

Table III.

Expression of Ls-eIF4E°, but not Ls-eIF4E1, restores LMV accumulation in mo11 or mo12 plants

Virus accumulation was assayed by ELISA 3 weeks after inoculation with LMV-0 containing the Ls-eIF4E°, Ls-eIF4E1, or Ls-eIF(is)4E coding sequence. Results not shown, obtained after serial dilutions indicated that in this particular experiment, the relationship between antigen concentration and OD405 was linear for OD values below 0.6.

| Genotype | LMV-0-clv | LMV-0-4E° | LMV-0-4E1 | LMV-0-iso4E |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salinas (susceptible) | 0.856 ± 0.052 | 0.800 ± 0.074 | 0.840 ± 0.118 | 0.783 ± 0.098 |

| Mantilia (mo11) | 0.019 ± 0.003 | 1.017 ± 0.092 | 0.017 ± 0.005 | 0.014 ± 0.002 |

| Salinas 88 (mo12) | 0.274 ± 0.122 | 0.707 ± 0.064 | 0.017 ± 0.015 | 0.010 ± 0.002 |

Together, these results indicate that expression of Ls-eIF4E° rendered LMV able to accumulate and produce symptoms in mo11 and mo12 genotypes, unlike that of Ls-eIF4E1 or Ls-eIF(iso)4E.

DISCUSSION

In this paper, we report the isolation of three alleles of the lettuce translation initiation factor eIF4E in their cDNA form. Sequence covariation, genetic cosegregation of one of these alleles, and functional complementation using two independent assays make evidence that two of these alleles correspond to the recessive LMV resistance genes mo11 and mo12, respectively. A direct role of Ls-eIF(iso)4E sequence variations in lettuce mo1-regulated response to LMV was ruled out because no variation in sequence could be observed in this gene when lettuce genotypes differing in their behaviors against LMV where examined, and Ls-eIF(iso)4E ectopic expression did not restore LMV susceptibility. The immediate consequence of this conclusion is to confirm that mo11 and mo12 are alleles of a single gene as it has been suggested (Ryder, 1970; Dinant and Lot, 1992).

The involvement of eIF4E in the ability of LMV to successfully infect and produce symptoms in lettuce is reminiscent to the recent demonstration that the homologous protein is involved in recessive PVY resistance in pepper (Ruffel et al., 2002). In Arabidopsis, disruption of eIF(iso)4E either by point mutations (Lellis et al., 2002) or by T-DNA insertion (Duprat et al., 2002) was associated with resistance to three different potyviruses (TEV, TuMV, and LMV). Therefore, according to the plant-potyvirus pair considered, one or another eIF4E isoform appears to be involved in virus resistance.

The translation initiation factor 4E is an essential component of the eukaryotic mRNA translation machinery and possibly also has a role in other processes of the cell cycle (Strudwick and Borden, 2002). Therefore, the viability of any eIF4E mutant must be associated either with a lack of deleterious functional effects or in functional takeover by other proteins, chiefly eIF4E isoforms. The domains of eIF4E involved in cap binding and VPg binding are probably close but distinct because binding of TuMV VPg to the Arabidopsis eIF4E competes with, but does not completely block, that of a cap analog (Léonard et al., 2000). Ls-eIF4E1 and Ls-eIF4E2 differed from Ls-eIF4E° in two different loops contiguous in the 3D structure of eIF4E at the rim of the cap-binding pocket. The Gln-108-Gly-109-Ala-110 triplet substituted by a His in Ls-eIF4E1 is located next to Asp-111, an amino acid involved in structural stabilization of the cap-binding pocket in the murine protein (Marcotrigiano et al., 1997). Our homology-based model of the lettuce eIF4E, although not confirmed experimentally, suggests that the position of the side chain of this Asp is not significantly affected by the deletion observed in Ls-eIF4E1 (Fig. 2; data not shown). Interestingly, the sequence variations in the pepper eIF4E gene found to be related with PVY resistance mapped to amino acids in these same two loops (Ruffel et al., 2002).

Although in Arabidopsis eIF(iso)4E defects block several potyviruses (Lellis et al., 2002) including LMV (Duprat et al., 2002), apparently no other potyviruses than LMV are controlled by mo11 or mo12 in lettuce (Provvidenti and Hampton, 1992; Montesclaros et al., 1997). This difference may be related to the fact that the eIF(iso)4E defects associated with potyvirus resistance in Arabidopsis are the result of large truncations of the gene product by premature translation termination (Lellis et al., 2002). Such C-terminally truncated proteins are likely to be more broadly affected than point sequence variants such as Ls-eIF4E1 or Ls-eIF4E2 for any function played in the viral cycle, therefore providing a base for a plurispecific antiviral effect. Conceptually, other sequence variations could also result in a plurispecific effect, as in the case of the PVY (Ruffel et al., 2002) and TEV (S. Ruffel, unpublished data) resistance gene pvr2 in pepper.

Functional complementation for systemic accumulation of LMV-0-GFP in mo12 plants was readily observed after agro-infiltration of each of the three Ls-eIF4E allelic types. However, Ls-eIF4E°, the allele found in susceptible lettuce genotypes, was more efficient in that than were Ls-eIF4E1 or Ls-eIF4E2. The ability of Ls-eIF4E1 to complement for LMV susceptibility in mo12 plants when expressed by agro-infiltration but not from the viral genome may reflect essential differences in the two expression systems used (agro-infiltration allows expression before virus replication) and properties assayed (systemic down-load versus the whole process of infection).

The ability of Ls-eIF4E2 to complement systemic LMV accumulation upon agro-infiltration in an mo12 background suggests that quantitative expression can at least partially overcome the qualitative effect of mutations. A quantitative effect of Ls-eIF4E sequence variations in the LMV cycle can be related to the tolerance rather than resistance phenotype observed against LMV-0 in mo12 plants (Dinant and Lot, 1992; Revers et al., 1997). Similarly, in at least one of the Arabidopsis loss-of-susceptibility eIF(iso)4E mutants, rare infection foci were sometimes observed (Lellis et al., 2002), indicating that resistance is strong but not absolute even in the presence of an eIF(iso)4E protein completely lacking its C-terminal half. The quantitative stimulatory effect of eIF4E expression from the TEV genome in protoplasts prepared from a susceptible host (Schaad et al., 2000) also suggests a quantitative role of eIF4E in the potyvirus cycle. The ability of Ls-eIF4E°, upon expression from the viral genome, to restore not only systemic LMV accumulation in normally resistant mo11 plants, but also symptom expression in normally tolerant mo12 plants, suggests a functional link between tolerance (symptom-less virus multiplication) and resistance. Therefore, at least in the lettuce/LMV system, these two distinct phenotypes might represent two outcomes of a same mechanism playing at quantitatively different intensities.

How eIF4E and/or its isoform are involved in the cycle of potyviruses in plants is not understood currently. Candidate pathways include initiation of viral RNA translation, circularization of viral RNA before replication, or eIF4E sequestration related to host gene shut off (Aranda and Maule, 1998). In addition, because a significant fraction of both VPg and eIF4E is nuclear (Shukla et al., 1994; Strudwick and Borden, 2002), it is also possible that the VPg-eIF4E interaction takes place in the nucleus and disturbs one of the increasingly better known functions of eIF4E within this cell compartment, such as mRNA processing or even nuclear translation (Strudwick and Borden, 2002). Finally, eIF4E could be involved, through its interaction with VPg, in the control of the successive fates encountered by the viral RNA (translation, replication, intracellular and cell-to-cell transport, encapsidation, etc).

In conclusion, although an increasing number of resistance genes against plant pathogens are being cloned and characterized, most of them are dominant and related to the hypersensitive reaction or to extreme resistance, a phenotype related to the hypersensitive reaction and leading to virtual immunity to viruses in plants (Bendahmane et al., 1999). Host genes whose mutations impair the cycle of plant viruses have been identified, and some of them have even been isolated (Diez et al., 2000; Yamanaka et al., 2000; Lellis et al., 2002). However eIF4E is the first natural recessive virus resistance gene that has been isolated in plants: pepper (Ruffel et al., 2002) and now lettuce (this study). The function of eIF4E and/or eIF(iso)4E in the potyvirus cycle is largely unknown, but the negative effect of sequence variations in these factors on the accumulation of various potyviruses in various host plants indicates that it is probably a conserved one. It is tempting to speculate that some of the mechanisms involved may even be shared with other viral genera having a VPg at the 5′ end of their genome; for instance, nepoviruses, for which interaction of the VPg-Pro proteolytic precursor with eIF(iso)4E has been described recently (Léonard et al., 2002).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material and Viral Constructs

All plants were grown under greenhouse conditions. The LMV-susceptible lettuce (Lactuca sativa) genotypes Fiona, Girelle, Jessy, Mariska, Salinas, Vanguard, Trocadéro, and the early flowering accession 87-20M (Ryder, 1996), the mo11 genotypes Alizé, Classic, Floribibb, Malika, Mantilia, Oriana, and Presidio, and the mo12 genotypes Autumn Gold, Desert Storm, Vanguard 75, and Salinas 88 (Candresse et al., 2002) were used. The susceptible genotype Trocadéro was routinely used to propagate LMV. Two independent pairs of lettuce genotypes included in this analysis, namely Salinas/Salinas 88 and Vanguard/Vanguard 75, are nearly isogenic for mo12 (Ryder, 1979, 1991). The use of genetic markers showed that the region introgressed around mo12 in the genome of Salinas 88 and Vanguard 75 is small (Irwin et al., 1999).

All experiments were made with LMV-0, an LMV isolate unable to produce symptoms in mo11 and mo12 plants (Revers et al., 1997). The recombinant construct LMV-0-GFP carries an insertion of the Aequorea victoria gfp gene between the regions coding for P1 and Hc-Pro of the viral genome, with an engineered NIa-Pro cleavage site, so that the GFP protein is processed from Hc-Pro in vivo (S. German-Retana, unpublished data). LMV-0-4E°, LMV-0-4E1, and LMV-0-iso4E were constructed similarly by inserting the Ls-eIF4E°, Ls-eIF4E1, and Ls-eIF(iso)4E coding regions, respectively, in frame between the P1 and Hc-Pro domains of LMV, with an NIa-Pro cleavage site resulting in the addition of eight amino acids (PGDEVYHQ) at the C terminus of the eIF4E sequence and five amino acids (SDVPG) at its N terminus. LMV-0-clv is an empty viral vector with only these additional amino acids but no eIF4E or other gene inserted. Lettuce plants primarily inoculated by biolistics (Helios Gene-Gun, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) were homogenized in 25 mm Na2HPO4 containing 2% (w/v) diethyldithiocarbamate and used to rub inoculate plants as described previously (Revers et al., 1997). Detection of the viral progeny by RT-PCR was performed as described previously (Krause-Sakate et al., 2002). Double-antibody sandwich ELISA was performed as described after homogenization of plant tissues in 4 volumes of extraction buffer (Revers et al., 1997).

F1 hybrids between Mantilia (mo11/mo11) and the susceptible genotypes Mariska and Girelle were self-pollinated to obtain F2 progenies. The parental lines, the F1 hybrids, and the F2 individuals were evaluated under greenhouse conditions for LMV resistance. Plants were rub inoculated 3 weeks after sowing at the five- to six-leaves stage. Symptoms were recorded 10 to 15 d after inoculation. These conditions ensured symptom appearance in 100% of Mariska and Girelle, whereas no symptoms were visible in Mantilia.

RT-PCR Amplification, Cloning, and Sequencing of cDNAs

Total RNA was extracted from 100 to 200 mg of leaf tissues using TRI Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis). Total cDNA was synthesized from 5 μg of total RNA using 15 units of AMV RT (Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala) and 1 μm oligo(dT) in a total volume of 50 μL, incubated for 1 h at 42°C.

PCR amplification was routinely performed using 1 μL of the total cDNAs in 50-μL reactions containing 0.5 units of Extra-Pol I Taq DNA polymerase (Eurobio, Les Ulis, France) or Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase High Fidelity (Invitrogen), using 1 μm oligonucleotide primers. For these reactions, 40 cycles (30 s of denaturation at 95°C, 30 s of annealing at different temperatures according to the primers used, and 1 min of elongation at 72°C) were performed in a thermal cycler (iCycler, Bio-Rad) after an initial denaturation of the RNA-cDNA duplex at 95°C for 2 min. The SMART RACE cDNA amplification kit (CLONTECH) was used according to the recommendations provided by the supplier to amplify the cDNA 5′ and 3′ ends of eIF4E, and, similarly, the 3′- and 5′-RACE Systems (Invitrogen) were used to amplify the 5′ and 3′ ends of eIF(iso)4E cDNA. The oligonucleotides used are listed in Table IV.

Table IV.

Oligonucleotides used in this work

The name of each oligonucleotide is given, with “f” as a suffix for forward oligonucleotides with respect to the mRNA polarity and “r” for reverse oligonucleotides. In the name of each oligonucleotide, the no. before the suffix indicates the position of the 5′-most nucleotide along the Ls-eIF4E sequence. Oligonucleotides provided with the RACE kits (CLONTECH, Palo Alto, CA; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) are not shown.

| Name | Sequence (5′ → 3′) |

|---|---|

| Ls4E3f | GGGGGGGTGGAAGAAATA |

| Ls4E83f | GGAGAAGAAGATGAACAACTGGAAGAGG |

| 4E198f | TCATGGACWTTYTGGTTYGATAAY |

| 4E193f | CCAGAATTCCTGGACCTTYTGGTTCGA |

| Ls4E250f | TTGGGGTAGTTCCATGCGCCCTA |

| Ls4E255r | CCCCAAGCGACTTGCTTGGACTTAGCAGAGGG |

| 4E408r | GCACAGATAGGGTCYTCCCA |

| Ls4E442r | TTTGGTAAAGGTCATAGTCCACTTTCCA |

| Ls4E697r | TTTAGCACTTCTATCAAGAG |

| Ls4E813r | GCAGAATTGTAGCATAAATCGGG |

| Ls(iso)4E680r | GCTGCAAATTGTTCTAGG |

The pGEM-T Easy vector system (Promega, Madison, WI) was used to clone cDNAs after PCR amplification. Automated DNA sequencing of cloned fragments or PCR products was performed at Genaxis (St-Cloud, France) or Genome Express (Grenoble, France), using ABI PRISM 373XL or 377 sequencers (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Generation of the CAPS Marker eIF4E-PagI

Total RNA was extracted from leaves of genotypes Mantilia, Mariska, and from the F1 hybrids and the F2 progenies as described above. From each RNA preparation, an eIF4E cDNA fragment of about 442 to 448 bp was amplified by RT-PCR using the oligonucleotides Ls4E250f and Ls4E697r (Table IV). The amplified cDNAs were subjected to digestion by the PagI endonuclease (Fermentas, Vilnius, Lithuania). The digestion products were resolved by electrophoresis in a 1.5% (w/v) agarose gel. Digestion at an additional PagI site present in all three types of Ls-eIF4E sequences provided an internal control for PagI activity by generating a 35-bp fragment not visualized in this electrophoresis system and a 407- to 413-bp fragment further digested in Ls-eIF4E1 to yield two fragments of 312 and 95 bp.

Functional Complementation Assay Using Agro-Infiltration

For transient expression in planta by agro-infiltration (Bechtold et al., 1993; Schöb et al., 1997), cDNAs were inserted in a 35S-nos expression cassette in the binary vector pGreenII (Hellens et al., 2000). Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58C1 was transformed by electroporation and grown overnight at 28°C in Luria-Bertani medium containing 5 μg mL–1 tetracycline, 50 μg mL–1 kanamycine, 10 mm MES, and 20 μm acetosyringone. The bacteria were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in 10 mm MES and 10 mm MgCl2 containing 150 μm acetosyringone to an OD600 of 0.6. They were then incubated at room temperature for 4 h and infiltrated using a syringe in apical leaves of plants that had been inoculated 5 to 6 d earlier with LMV-0-GFP on their lower leaves. Agro-infiltration took place when GFP fluorescence began to be visible under UV light near the veins in upper noninoculated leaves in the susceptible genotypes. Four to 6 d after infiltration, GFP expression was monitored as described by German-Retana et al. (2000) and using a fluorescence stereomicroscope (MZ FLIII, Leica Microsystems, Heerburg, Switzerland) equipped with a filter with an excitation window at 470 ± 20 nm and an arrest window at 525 ± 25 nm.

Sequence Analysis

The following eIF4E cDNA and protein sequences were retrieved from GenBank: human (Homo sapiens; NM_004846, XM_017925), mouse (Mus musculus) (M61731), Spodoptera frugiperda (AF281654), rice (Oryza sativa; U34597), maize (Zea mays; AF076954), wheat (Triticum aestivum; Z12616), tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum; AF259801), and Arabidopsis (Y10548, NM_102695 and NM_102699). The eIF(iso)4E sequences were: rice (U34598), maize (AF076955), and Arabidopsis (Y10547). Homology-based database searches were made in GenBank using the program BLAST (Altschul et al., 1990). The nucleotide and amino acid sequences were aligned using ClustalW (Thompson et al., 1994), which generates and uses a distance dendrogram (Saitou and Nei, 1987) to construct multiple sequence alignments, or with Align (Myers and Miller, 1988) for pair-wise alignments.

The 3D structures of cap-bound eIF4E of human (Hs-eIF4E) and mouse (Mm-eIF4E) were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb) with the codes 1IPB and 1EJH, respectively. Comparative protein modeling was elaborated online using Swiss-model and Swiss-PdbViewer (Guex and Peitsch, 1997) and 3D-Jigsaw (Bates et al., 2001). The fit between 3D structure models was evaluated in Swiss-PdbViewer by calculating the RMS deviation (Chothia and Lesk, 1986) after iterative fitting.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the excellence of Thierry Mauduit for plant care, to Kathryn Mayo for improving the English of the manuscript, and to Sandrine Ruffel and Drs. Thierry Delaunay, Thierry Michon, Frédéric Revers, and Christophe Robaglia for their stimulating comments and discussions.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at http://www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.102.017855.

This work was partially supported by the Etablissement Public Régional Aquitaine (ref. no. 20000307004).

References

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ (1990) Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 215: 403–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aranda M, Maule AJ (1998) Virus-induced host gene shutoff in animals and plants. Virology 243: 261–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates PA, Kelley LA, MacCallum RM, Sternberg MJ (2001) Enhancement of protein modeling by human intervention in applying the automatic programs 3D-JIGSAW and 3D-PSSM. Proteins Suppl 5: 39–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechtold N, Ellis J, Pelletier G (1993) In planta Agrobacterium mediated gene transfer by infiltration of adult Arabidopsis thaliana plants. C R Acad Sci Ser III Sci Vie 316: 1194–1199 [Google Scholar]

- Bendahmane A, Kanyuka K, Baulcombe DC (1999) The Rx gene from potato controls separate virus resistance and cell death responses. Plant Cell 11: 781–792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos L, Huijberts N, Cuperus C (1994) Further observations on variation of lettuce mosaic virus in relation to lettuce (Lactuca sativa), and a discussion of resistance terminology. Eur J Plant Pathol 100: 293–314 [Google Scholar]

- Candresse T, Le Gall O, Maisonneuve B, German-Retana S, Redondo E (2002) The use of green fluorescent protein-tagged recombinant viruses greatly simplifies Lettuce mosaic virus resistance testing in lettuce. Phytopathology 92: 169–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carberry SE, Darzynkiewicz E, Goss DJ (1991) A comparison of the binding of methylated cap analogues to wheat germ protein synthesis initiation factors 4F and (iso)4F. Biochemistry 30: 1624–1627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chothia C, Lesk AM (1986) The relation between the divergence of sequence and structure in proteins. EMBO J 5: 823–826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez J, Ishikawa M, Kaido M, Ahlquist P (2000) Identification and characterization of a host protein required for efficient template selection in viral RNA replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 3913–3918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinant S, Lot H (1992) Lettuce mosaic virus. Plant Pathol 41: 528–542 [Google Scholar]

- Duprat A, Caranta C, Revers F, Menand B, Browning KS, Robaglia C (2002) The Arabidopsis eukaryotic initiation factor (iso)4E is dispensable for plant growth but required for susceptibility to potyviruses. Plant J 32: 927–934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German-Retana S, Candresse T, Alias E, Delbos R, Le Gall O (2000) Effects of GFP or GUS tagging on the accumulation and pathogenicity of a resistance breaking LMV isolate in susceptible and resistant lettuce cultivars. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact 13: 316–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb KS, Hellmann GM, Pirone TP (1989) Nature of resistance of a tobacco cultivar to tobacco vein mottling virus. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact 2: 232–339 [Google Scholar]

- Guex N, Peitsch MC (1997) SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis 18: 2714–2723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellens RP, Edwards EA, Leyland NR, Bean S, Mullineaux PM (2000) pGreen: a versatile and flexible binary Ti vector for Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation. Plant Mol Biol 42: 819–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin SV, Kesseli RV, Waycott W, Ryder EJ, Cho JJ, Michelmore RW (1999) Identification of PCR-based markers flanking the recessive LMV resistance gene mo1 in an intraspecific cross in lettuce. Genome 42: 982–986 [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa M, Diez J, Restrepo-Hartwig M, Ahlquist P (1997) Yeast mutations in multiple complementation groups inhibit brome mosaic virus RNA replication and transcription and perturb regulated expression of the viral polymerase-like gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 13810–13815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller KE, Johansen IE, Martin RR, Hampton RO (1998) Potyvirus genome-linked protein (VPg) determines Pea seed-borne mosaic virus pathotype-specific virulence in Pisum sativum. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact 11: 124–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause-Sakate R, Le Gall O, Fakhfakh H, Peypelut M, Marrakchi M, Varveri C, Pavan MA, Souche S, Lot H, Zerbini FM et al. (2002) Molecular characterization of Lettuce mosaic virus field isolates reveals a distinct and widespread type of resistance-breaking isolate: LMV-Most. Phytopathology 92: 563–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lellis AD, Kasschau KD, Whitham SA, Carrington JC (2002) Loss-of-susceptibility mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana reveal an essential role for eIF(iso)4E during potyvirus infection. Curr Biol 12: 1046–1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Léonard S, Chisholm J, Laliberté JF, Sanfaçon H (2002) Interaction in vitro between the proteinase of Tomato ringspot virus (genus Nepovirus) and the eukaryotic translation initiation factor iso4E from Arabidopsis thaliana. J Gen Virol 83: 2085–2089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Léonard S, Plante D, Wittmann S, Daigneault N, Fortin MG, Laliberté JF (2000) Complex formation between potyvirus VPg and translation eukaryotic initiation factor 4E correlates with virus infectivity. J Virol 74: 7730–7737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcotrigiano J, Gingras AC, Sonenberg N, Burley SK (1997) Cocrystal structure of the messenger RNA 5′ cap-binding protein (eIF4E) bound to 7-methyl-GDP. Cell 89: 951–961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcotrigiano J, Gingras AC, Sonenberg N, Burley SK (1999) Cap-dependent translation initiation in eukaryotes is regulated by a molecular mimic of eIF4G. Mol Cell 3: 707–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montesclaros L, Nicol N, Ubalijoro E, Leclerc-Potvin C, Ganivet L, Laliberté JF, Fortin MG (1997) Response to potyvirus infection and genetic mapping of resistance loci to potyvirus infection in Lactuca. Theor Appl Genet 94: 941–946 [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JF, Rhoads RE, Hunt AG, Shaw JG (1990) The VPg of tobacco etch virus RNA is the 49-kDa proteinase or the N-terminal 24-kDa part of the proteinase. Virology 178: 285–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers EW, Miller W (1988) Optimal alignments in linear space. Comput Appl Biosci 4: 11–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pestova TV, Kolupaeva VG, Lomakin IB, Pilipenko EV, Shatsky IN, Agol VI, Hellen CU (2001) Molecular mechanisms of translation initiation in eukaryotes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 7029–7036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pink DAC, Lot H, Johnson R (1992) Novel pathotypes of lettuce mosaic virus: breakdown of a durable resistance? Euphytica 63: 169–174 [Google Scholar]

- Pontier D, Balague C, Roby D (1998) The hypersensitive response. A programmed cell death associated with plant resistance. C R Acad Sci Ser III Sci Vie 321: 721–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provvidenti R, Hampton RO (1992) Sources of resistance to viruses in the Potyviridae. Arch Virol Suppl 5: 189–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff F, Harrison BD, Baulcombe DC (1997) A similarity between viral defense and gene silencing in plants. Science 276: 1558–1560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redondo E, Krause-Sakate R, Yang SJ, Lot H, Le Gall O, Candresse T (2001) Lettuce mosaic virus (LMV) pathogenicity determinants in susceptible and tolerant lettuce varieties map to different regions of the viral genome. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact 14: 804–810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichmann JL, Lain S, Garcia JA (1992) Highlights and prospects of potyvirus molecular biology. J Gen Virol 73: 1–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revers F, Lot H, Souche S, Le Gall O, Candresse T, Dunez J (1997) Biological and molecular variability of Lettuce mosaic virus isolates. Phytopathology 87: 397–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez CM, Freire MA, Camilleri C, Robaglia C (1998) The Arabidopsis thaliana cDNAs coding for eIF4E and eIF(iso)4E are not functionally equivalent for yeast complementation and are differentially expressed during plant development. Plant J 13: 465–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruffel S, Dussault MH, Palloix A, Moury B, Bendahmane A, Robaglia C, Caranta C (2002) A natural recessive resistance gene against potato virus Y in pepper corresponds to the eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E). Plant J 32: 1067–1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryder EJ (1970) Inheritance of resistance to common lettuce mosaic. J Am Soc Hortic Sci 95: 378–379 [Google Scholar]

- Ryder EJ (1979) Vanguard 75 lettuce. Hortscience 14: 284–286 [Google Scholar]

- Ryder EJ (1991) Salinas 88 lettuce. Hortscience 26: 439–440 [Google Scholar]

- Ryder EJ (1996) Ten lettuce genetic stocks with early flowering genes Ef-1ef-1 and Ef-2ef-2. Hortscience 31: 473–475 [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N, Nei M (1987) The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol 4: 406–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaad MC, Anderberg RJ, Carrington JC (2000) Strain-specific interaction of the Tobacco etch virus NIa protein with the translation initiation factor eIF4E in the yeast two-hybrid system. Virology 273: 300–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaad MC, Carrington JC (1996) Suppression of long-distance movement of tobacco etch virus in a nonsusceptible host. J Virol 70: 2556–2561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaad MC, Haldeman-Cahill R, Cronin S, Carrington JC (1996) Analysis of the VPg-proteinase (NIa) encoded by tobacco etch potyvirus: effects of mutations on subcellular transport, proteolytic processing, and genome amplification. J Virol 70: 7039–7048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schöb H, Kunz C, Meins F Jr (1997) Silencing of transgenes introduced into leaves by agroinfiltration: a simple, rapid method for investigating sequence requirements for gene silencing. Mol Gen Genet 256: 581–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla DD, Ward CW, Brunt AA (1994) The Potyviridae. CAB International, Wallingford, UK

- Strudwick S, Borden KL (2002) The emerging roles of translation factor eIF4E in the nucleus. Differentiation 70: 10–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ (1994) CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, positions-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res 22: 4673–4680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomoo K, Shen X, Okabe K, Nozoe Y, Fukuhara S, Morino S, Ishida T, Taniguchi T, Hasegawa H, Terashima A et al. (2002) Crystal structures of 7-methylguanosine 5′-triphosphate (m(7) GTP)- and P(1)-7-methylguanosine-P(3)-adenosine-5′,5′-triphosphate (m(7) GpppA)-bound human full-length eukaryotic initiation factor 4E: biological importance of the C-terminal flexible region. Biochem J 362: 539–544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voinnet O (2001) RNA silencing as a plant immune system against viruses. Trends Genet 17: 449–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann S, Chatel H, Fortin MG, Laliberté JF (1997) Interaction of the viral protein genome linked of Turnip mosaic potyvirus with the translational eukaryotic initiation factor (iso) 4E of Arabidopsis thaliana using the yeast two-hybrid system. Virology 234: 84–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka T, Ohta T, Takahashi M, Meshi T, Schmidt R, Dean C, Naito S, Ishikawa M (2000) TOM1, an Arabidopsis gene required for efficient multiplication of a tobamovirus, encodes a putative transmembrane protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 10107–10112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]