Abstract

Neutrophils are thought to rely solely on nonspecific immune mechanisms. Here we provide molecular biological, immunological, ultrastructural, and functional evidence for the presence of a T cell receptor (TCR)-based variable immunoreceptor in a 5–8% subpopulation of human neutrophils. We demonstrate that these peripheral blood neutrophils express variable and individual-specific TCRαβ repertoires and the RAG1/RAG2 recombinase complex. The proinflammatory cytokine granulocyte colony-stimulating factor regulates expression of the neutrophil immunoreceptor and RAG1/RAG2 in vivo. Specific engagement of the neutrophil TCR complex protects from apoptosis and stimulates secretion of the neutrophil-activating chemokine IL-8. Our results, which also demonstrate the presence of the TCR in murine neutrophils, suggest the coexistence of a variable and an innate host defense system in mammalian neutrophils.

Keywords: innate immune system, neutrophil granulocyte, T cell receptor

Neutrophils are the first cells at sites of inflammation. They are recruited from circulation and bone marrow reserves in response to host and pathogen-derived stimuli and confer immunity by phagocytosis and by killing microorganisms (1). Neutrophil recruitment to inflammatory sites is mediated by chemoattractants such as IL-8 (2), and the proliferation and differentiation of neutrophil precursors in the bone marrow are largely controlled by the hematopoietic growth factor granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) (3). Based on their known biological properties, neutrophils have traditionally been assigned to the nonadaptive immune system, a concept that is supported by their ability to recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns through invariant receptors (4). Unlike neutrophils, T cells recognize antigens by an antigen-specific receptor, the T cell receptor (TCR). Since its identification in 1984, extensive study has established the central role of the TCR in T cell-mediated adaptive cellular immunity, and the concept has gained general acceptance that this immunoreceptor is exclusively present in cells of the T lymphocyte lineage (4).

We demonstrate the existence of a TCR-based variable immunoreceptor in a 5–8% subpopulation of mammalian neutrophils. Activation of the neutrophil immunoreceptor by known TCR agonists increases IL-8 secretion and inhibits neutrophil apoptosis. Furthermore, we demonstrate that expression of the neutrophil immunoreceptor machinery is modulated by G-CSF in vivo. Our findings reveal a molecular basis for variable and adaptive immunorecognition in neutrophils.

Results

The TCRαβ Complex Is Expressed by a Neutrophil Subpopulation.

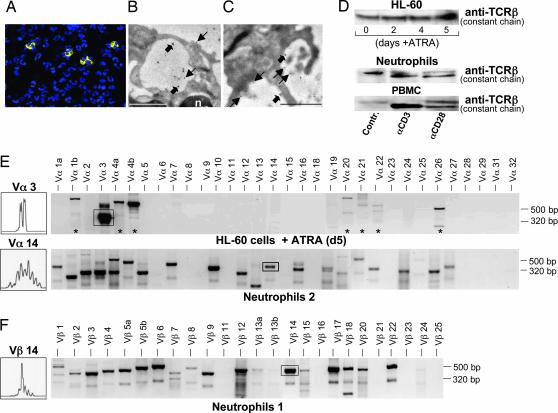

A series of control experiments prompted us to test the hypothesis that human neutrophils express components of the TCR machinery. To authenticate the presence of the TCRαβ complex in neutrophils in situ, we performed immunocytochemistry using monoclonal antibodies against the TCR α-subunit and β-subunit. We consistently found positive staining in a subset of freshly obtained peripheral blood neutrophils indicating that significant quantities of the TCRαβ complex are expressed by a distinct neutrophil subpopulation (Fig. 1A). No staining was observed in control experiments in the absence of primary or secondary antibodies (Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). A survey among healthy donors (n = 5) revealed that, on average, a 5–8% fraction of circulating neutrophils displayed TCRαβ expression (data not shown). To obtain detailed information on the subcellular localization of the TCRαβ complex in neutrophils we performed ImmunoGold electron microscopy. Double-labeling for simultaneous detection of the TCR α- and β-subunits revealed specific staining in circulating neutrophils (Fig. 1B) and also in infiltrating tissue neutrophils in a case of acute appendicitis (Fig. 1C). Comparable to Jurkat leukemic T cells (positive controls) (Fig. 8, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site), gold particles were frequently grouped in pairs or in larger clusters consistent with the presence of TCRαβ heterodimers and higher-order TCR complexes (5). TCRαβ expression was most abundant on the cell surface of TCR-expressing neutrophils but also detectable in vesicular compartments and in the perinuclear region. These sites are in agreement with the biosynthetic pathway and the intracellular recycling route of the TCR in T cells (6).

Fig. 1.

Presence of TCRαβ in circulating human neutrophils and promyelocytic HL-60 cells. (A) A subpopulation of normal neutrophils expresses TCRαβ-subunits. Shown are circulating neutrophils isolated from a healthy donor that were subjected to fluorescence immunocytochemistry using monoclonal antibodies to the TCR α-subunit and β-subunit. TCRαβ-positive cells show yellow fluorescence, and nuclei (blue) are DAPI-counterstained. (B and C) ImmunoGold electron microscopy demonstrating the presence and subcellular distribution of the TCRαβ complex in peripheral blood neutrophils (B) and neutrophils infiltrating the appendix in a case of acute appendicitis (C). Plain and bold arrows highlight gold particles grouped in pairs and clusters consistent with the presence of TCRαβ heterodimers and higher-order TCRαβ complexes, respectively. Note specific staining on the cell surface, in vesicular compartments, and in the perinuclear region of neutrophils. n, nucleus. (Scale bars: 1 μm.) (D Top) Constitutive expression of the TCRβ chain in native HL-60 cells and during ATRA-induced differentiation. (D Middle) Induction of TCRβ in neutrophils by monoclonal antibodies to CD3 and CD28, respectively. Aliquots of 2 × 106 cells were incubated for 1 min at 37°C in the presence or absence (control) of antibodies to CD3 and CD28 and analyzed by immunoblot using a monoclonal antibody specifically reacting with the TCRβ subunit. (D Bottom) Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from the same blood draw are shown as reference. The larger band in neutrophils and peripheral blood mononuclear cells represents a previously reported differently glycosylated TCRβ chain (8). (E Upper) RT-PCR expression profiling of 32 different TCR Vα chains (Vα1–32) demonstrating selective expression of Vα3 mRNA in HL-60 cells after 5 days of ATRA (5 μM)-induced differentiation [+ ATRA (d5)] (top). Asterisks denote nonspecific amplification products. (E Lower) Representative TCR Vα expression profiling in peripheral blood neutrophils from a healthy individual (Neutrophils 2). (F) Expression of complex Vβ repertoires in neutrophils in a different individual (Neutrophils 1). TCR CDR3 length spectratypes (Left) are shown for Vα3 (HL-60 cells) and, representatively, for Vα14 and Vβ14 (neutrophils). Boxed areas designate the amplification products for which spectratyping was performed. Specific PCR products range from 248 to 462 bp (Vα chains) and from 417 to 557 bp (Vβ chains), respectively.

The human leukemia cell line HL-60 can be induced to differentiate in vitro into neutrophil-like cells by all-transretinoic acid (ATRA) (7). Immunoblot demonstrated the presence of the TCRβ constant chain in native and differentiating HL-60 cells (Fig. 1D Top). In unstimulated neutrophils, a band was detected that was slightly larger than 47 kDa, consistent with the presence of a previously reported differentially glycosylated TCR variant (8) (Fig. 1D Bottom). Monoclonal antibodies to CD3 and CD28 (9) are commonly used to mimic activation of the TCR. Activation with CD3 and, to a lesser degree, CD28 antibodies triggered induction of TCRβ. These results are in line with the finding that human neutrophils express CD3ζ (Fig. 4 B and C) and CD28 (10).

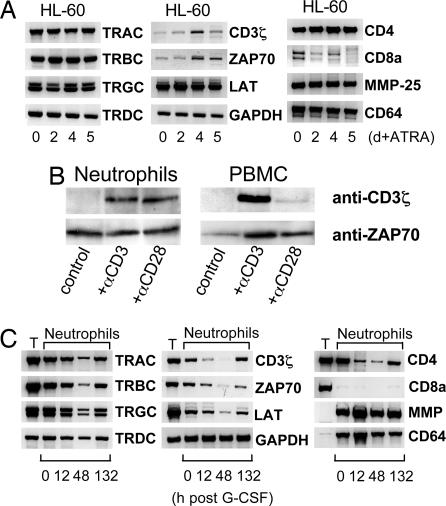

Fig. 4.

Expression and regulation of invariant components of the TCR complex in HL-60 cells and neutrophils. (A) mRNA expression of TCRα, β, γ, and δ constant chains (TRAC-TRDC), constituents of the TCR signaling complex (CD3ζ, ZAP70, and LAT), and various leukocyte-specific genes (CD4, CD8a, matrix metalloproteinase 25, and CD64) during ATRA-dependent differentiation of HL-60 cells. TRGC double bands represent the two known alternative splice variants. RT-PCR amplification of GAPDH is shown as a reference. (B) Induction of CD3ζ, but not ZAP70, by anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies in neutrophils. Aliquots of 2 × 106 freshly obtained cells were incubated for 1 min at 37°C in the presence or absence (control) of antibodies to CD3 and CD28, respectively, and analyzed by Western blot using the antibodies indicated. (C) G-CSF suppresses the expression of the neutrophil TCR complex in the circulation in vivo. RT-PCR expression profiling was performed in neutrophils at the indicated time points after G-CSF administration. Data are representatively shown for one proband. Expression of neutrophil (matrix metalloproteinase 25 and CD64) and T cell marker (CD8a) genes are shown as reference. T, T cells from the same individual; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase.

Circulating Human Neutrophils Express Individual-Specific TCR Vαβ mRNA Repertoires.

We next determined whether HL-60 cells and neutrophils exhibit TCR Vα and Vβ repertoire diversity. RT-PCR expression profiling of 32 TCR Vα mRNAs revealed isolated expression of TCR Vα3 mRNA in HL-60 cells (Fig. 1E Upper). Complementarity-determining region 3 (CDR3) spectratyping of the Vα3 chain revealed oligoclonality (11), consistent with the clonal nature of HL-60 cells (Fig. 1E Upper Left). To assess TCR Vα and Vβ repertoire diversity in neutrophils, TCR Vαβ mRNA expression profiling was performed on neutrophil and T cell fractions from healthy individuals (n = 6). We found expression of a multitude of TCR Vαβ chain mRNAs in the neutrophil fraction (Fig. 1 E and F). Control experiments to exclude contamination are shown in Fig. 9, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site. Significant differences of TCR Vαβ gene expression patterns between neutrophils and T cells from the same individuals were observed (Fig. 10, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Representative analysis of the Vα14 and Vβ14 CDR3 spectratypes revealed Gaussian and skewed (Vβ14 Neutrophils 1) CDR3 length distribution profiles indicative of complex Vαβ repertoires as they are observed in T cells (12). TCR Vαβ expression profiles in neutrophils differed interindividually (Fig. 1 E and F and Fig. 10). Together, these data indicate that peripheral blood neutrophils express complex and individual-specific TCR Vαβ repertoires.

We next characterized the TCRαβ-expressing neutrophil subpopulation by flow cytometry. Ethanol-fixed neutrophil CD16bright cells showed positive staining for TCRα for a subfraction of 5% cells (Fig. 2A). Neutrophils showed positive staining for CD16 but not for T cell markers (CD3, CD4, and CD8) (Fig. 11, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). We also observed positive staining for TCRα in HL-60 cells (Fig. 2B). The identification of a CD16bright TCRα+ subfraction by flow cytometry thus confirmed the presence of the TCR in neutrophils.

Fig. 2.

Flow cytometric analysis of TCRαβ expression in human neutrophils and HL-60 cells. (A) Double-staining of human neutrophils for CD16/TCRα and CD16/TCRβ, respectively. Note that a CD16bright subfraction of circulating neutrophils displays positive staining for TCRα. Peripheral blood neutrophils from a healthy individual were purified and stained with the indicated antibodies to the TCR and lineage surface markers, respectively. Staining for CD16 and TCRα/TCRβ was carried out in ethanol-fixed cells. Thin lines in the histograms represent staining with isotype controls. (B) HL-60 cells stain positively for TCRα. Positive staining for myeloid lineage markers (CD15 and CD33) and the absence of staining for the lymphoid marker CD3 are shown.

Murine Neutrophils Express TCR Vαβ Repertoires.

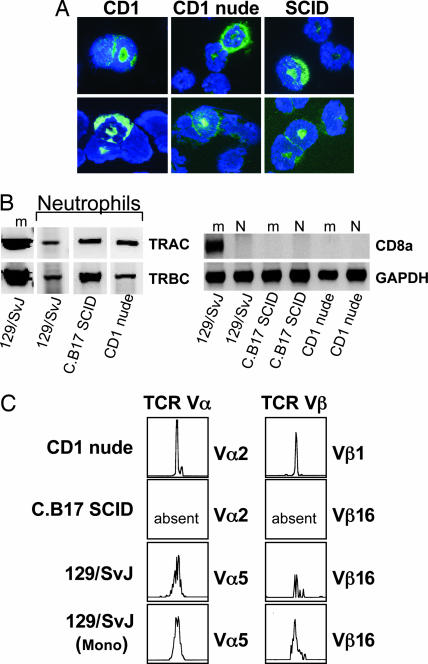

To test whether TCR expression in neutrophils is limited to the human immune system, purified splenic neutrophils from two normal mouse strains (CD1 and 129/SvJ) and two mutant strains lacking T cells (CD1 nude and C.B17 SCID) were analyzed for the presence of the TCRαβ. CD1 athymic mice have no T cells (13), and in C.B17 SCID mice the generation of TCRs is severely inhibited because of DNA repair defects, which leads to a failure of V(D)J recombination and combined T and B cell deficiency with minor “leakiness” (14). Immunocytochemistry showed positive staining of the TCRβ chain in a 5–7% subpopulation of neutrophils from three mouse strains investigated (Fig. 3A), and RT-PCR revealed mRNA expression of TCRα and TCRβ constant chains (Fig. 3B). TCR CDR3 spectratyping confirmed the presence of complex Vα5 and Vβ16 repertoires in the neutrophil fraction of normal 129/SvJ mice (Fig. 3C). Neutrophils from T cell-deficient CD1 nude mice also expressed TCR Vαβ repertoires, whereas no evidence for TCR Vαβ repertoire expression was found in neutrophils from recombination-defective C.B17 SCID mice.

Fig. 3.

Expression of the TCRαβ complex in murine neutrophils. (A) Immunocytochemistry demonstrating the presence of TCRβ-positive neutrophils (green fluorescence) in normal CD1 mice, T cell-deficient CD1 athymic nude mice, and lymphopenic C.B17 SCID mice, respectively. Neutrophils were isolated by MACS from spleens of each of the three strains using an antibody to Ly6-G (Gr1), and immunocytochemistry was performed by using an anti-mouse TCRβ monoclonal antibody recognizing a common epitope of the murine TCR complex. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Note the characteristic donut-shaped nucleus of murine neutrophils. (B) Expression of TCRαβ constant chain genes in purified spleen neutrophils (N) and the Ly6-G depleted mononuclear fraction (m) of normal 129/SvJ and T cell-deficient mice (CD1 nude and C.B17 SCID). Expression of the T cell marker gene CD8a and GAPDH is shown for the respective leukocyte preparations. The absence of CD8a mRNA expression in purified neutrophils demonstrates that the preparations were free of contaminating T cells. m, spleen mononuclear cells; N, spleen neutrophils. (C) Neutrophils from normal 129/SvJ and T cell-deficient CD1 nude mice express TCR Vαβ repertoires as evidenced by CDR3 spectratyping. Note the absence of TCR V chain repertoires in neutrophils from recombination-defective C.B17 SCID mice. Mono, mononuclear fraction (TCR-positive control).

To test whether and to which extent neutrophils express the TCR conditions of severe T cell deficiency, we assessed the expression of TCRαβ constant chains in peripheral blood neutrophils from an 8-week-old infant with X-linked SCID (X-SCID). X-SCID is a rare inherited immune system disorder with an incidence of 1:200,000 caused by mutations in the IL-2 receptor γ-chain (15). Affected individuals typically display dramatically reduced or absent T cells (T cell-negative/B cell-positive X-SCID) (16). At the time of blood draw the infant's WBC were as follows: 2,100 × 103 neutrophils per microliter, 1,380 × 103 lymphocytes per microliter, and 940 × 103 monocytes per microliter. Importantly, RT-PCR analysis of purified X-SCID neutrophils revealed expression of both the TCRα and the TCRβ constant genes, strongly suggesting that TCR expression in human X-SCID neutrophils occurs in the virtual absence of T cells (Fig. 12, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Consistent with these results, we also found that neutrophils from an adult patient with severe iatrogenic T cell deficiency (acute graft rejection) express the TCR (Fig. 12).

Neutrophils Express Essential Components of the TCR Signaling Complex.

We next investigated whether HL-60 and neutrophils express TCR constant chains and components of the TCR signaling complex. RT-PCR showed expression of each of the TCR α, β, γ, and δ constant chains (TRAC-TRDC) in HL-60 cells and neutrophils (Fig. 4A and C). Both cell types also express the CD3ζ chain (17), ζ-chain-associated protein kinase 70 (ZAP70) (18), and linker for activation of T cells (LAT) (19). ATRA-mediated differentiation induced up-regulation of CD3ζ and ZAP70 mRNA levels in HL-60 cells but had no effect on expression of LAT and TCR constant chains. Moreover, CD3- or CD28-activating antibodies resulted in increased CD3ζ but not ZAP70 expression (Fig. 4B).

TCR Expression in Neutrophils Is Modulated by G-CSF in Vivo.

We tested whether G-CSF impacts expression of the TCR machinery in circulating neutrophils in vivo. For this, a single dose (30 μg) of recombinant human G-CSF was administered s.c. to two healthy probands, and peripheral blood neutrophils were collected at various time points after injection (Fig. 13, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). G-CSF suppressed mRNA expression of all neutrophil TCR constant chains and components of the TCR signaling complex (CD4, CD3ζ, ZAP70, and LAT) during the first 48 h after injection (Fig. 4C). This effect was maximal at 12 h (individual 2; data not shown) and 48 h after injection (individual 1; Fig. 4C). Up-regulation of matrix metalloproteinase 25 (20) and CD64 indicated that the effect was not due to a global suppression of neutrophil gene expression. At 132 h after injection mRNA levels of all TCR constant chains and most signaling components had increased but were still below those levels found before G-CSF administration. These results suggest that G-CSF potently modulates gene expression of the neutrophil TCR complex in vivo.

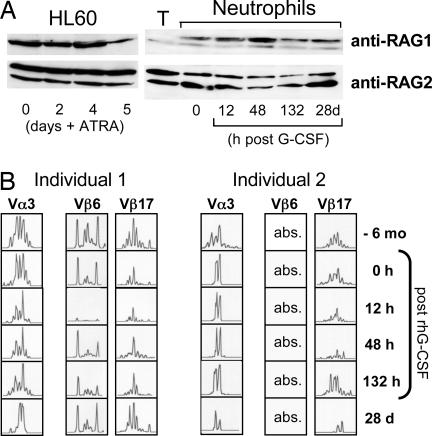

Neutrophils Express the RAG1/RAG2 Recombinase and Flexible TCR Vαβ Repertoires.

The recombination-activating gene proteins RAG1 and RAG2 initiate genomic V(D)J recombination. Western blot analysis showed constitutive expression of both proteins in HL-60 cells and circulating neutrophils (Fig. 5A). Constitutive expression of RAG1/RAG2 by neutrophils indicates that these cells possess the specific molecular equipment for generation of antigen receptor diversity. Time course analysis revealed that G-CSF induced up-regulation of RAG1 for a period of 48 h, which was paralleled by a moderate down-regulation of generally high RAG2 levels. To explore the dynamics of neutrophil TCRαβ repertoire diversity over time and its responsiveness to G-CSF we characterized the CDR3 spectratypes of selected V chains for the duration of 7 months in the two probands who were administered G-CSF. Some CDR3 spectratypes changed from Gaussian to oligoclonal profiles (Fig. 5B), whereas others remained constant, indicating that TCRαβ repertoires in neutrophils are variable. Clonal analysis of the CDR3 repertoire changes confirmed these results on the nucleotide sequence level (Fig. 14, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

Fig. 5.

Regulation of RAG1/RAG2 expression and TCR Vαβ CDR3 repertoire diversity in neutrophils by G-CSF in vivo. (A) Constitutive RAG1/RAG2 expression in HL-60 cells and neutrophils. Shown are transient up-regulation of RAG1 and down-regulation of RAG2 in circulating neutrophils in response to G-CSF. Note isolated RAG2 expression in peripheral blood T cells (T). The additional lower-molecular-mass RAG1 bands have been previously observed (25). Data are representatively shown for one proband. (B) Individual TCRαβ CDR3 repertoires change over time, and their expression is suppressed by G-CSF. TCR Vα3, Vβ6, and Vβ17 CDR3 length spectratypes are representatively shown for individuals 1 and 2 before (−6 mo and 0 h) and after (12 h, 48 h, 132 h, and 28 d) administration of G-CSF.

Stimulation of the TCR/CD3 Complex Induces Up-Regulation of bcl-xL Expression, Inhibits Apoptosis, and Enhances IL-8 Secretion.

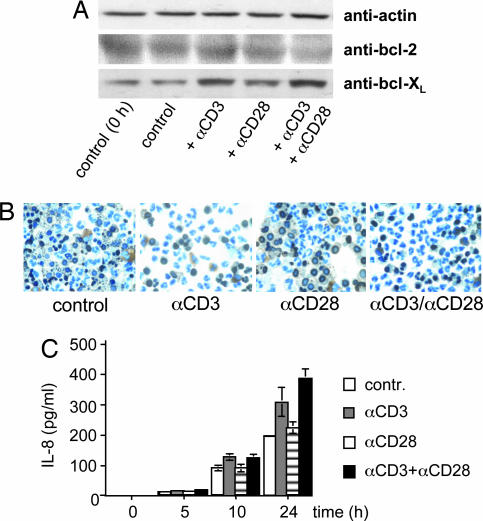

To explore a possible function of the neutrophil TCR in apoptosis, we determined the effect of the TCR agonists CD3 and CD28 on the expression of antiapoptotic factors and cell survival. Stimulation of neutrophils with both anti-CD3 and anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies induced up-regulation of bcl-xL starting at 3 h (Fig. 6A). CD28 stimulation alone did not alter bcl-xL expression. Engagement of CD3 had an antiapoptotic effect on neutrophils, as evidenced by TUNEL staining (Fig. 6B) and flow cytometry (data not shown). Furthermore, we examined whether CD3/CD28-mediated TCR engagement has an effect on neutrophil IL-8 secretion, an essential chemokine for early neutrophil recruitment. Indeed, time course analysis of CD3 and CD3/CD28 activation showed enhanced secretion of IL-8 by neutrophils within 24 h (Fig. 6C). This response was also observed when Fc γ-receptors were blocked by antibodies to CD16 and CD32 (Fig. 15, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site) or in the presence of autologous serum (data not shown), indicating that it is not mediated by nonspecific Fc receptor activation. Taken together, these data demonstrate that engagement of the CD3-dependent TCR signal transduction pathway inhibits apoptosis and triggers increased IL-8 secretion in neutrophils.

Fig. 6.

Induction of antiapoptotic responses and enhanced IL-8 secretion by CD3/CD28-mediated activation of neutrophils. (A) Activation of CD3 and CD3/CD28 costimulation (3 h) induce enhanced expression of bcl-XL but not bcl-2 in neutrophils. (B) Reduced percentages of TUNEL-positive neutrophils after 48 h of stimulation with anti-CD3 and anti-CD3/anti-CD28 antibodies. (C) Enhanced secretion of IL-8 by neutrophils during anti-CD3 or anti-CD3/anti-CD28-mediated TCR activation. Aliquots of 2 × 106 neutrophils were incubated in the presence of antibodies to CD3, CD28, or both for the indicated time points, and Western blot analyses and TUNEL assays were performed. IL-8 was determined in the neutrophil supernatant by ELISA.

Discussion

In this report several independent lines of evidence are presented for the existence of a TCR-based variable host defense system in human neutrophils. First, immunocytochemical analysis reveals that a subpopulation of human peripheral blood neutrophils expresses the TCRαβ complex, and ultrastructural data demonstrate its presence on the surface of both circulating and tissue neutrophils. Second, circulating neutrophils express individual-specific TCR Vαβ repertoires that display variation over time. Third, consistent with the variable nature of TCR Vαβ diversity, both recombinases, RAG1 and RAG2, the prerequisite for the generation of TCR repertoire diversity, are expressed by peripheral neutrophils. Finally, biochemical and molecular biological evidence indicates that neutrophils possess integral components of the TCR signaling machinery and that TCR engagement through the CD3/CD28 pathway enhances bcl-xL expression, protects neutrophils from apoptosis, and leads to increased IL-8 secretion. These results in humans are consistent with the finding that neutrophils from several mouse strains also express TCR Vαβ repertoires, suggesting that this may be a general feature of mammalian neutrophils. The presence of the TCR in circulating human neutrophils is also in agreement with our observation that promyelocytic HL-60 cells express major components of the TCR machinery. Of note, TCR expression in HL-60 cells is supported by two studies in the murine promyelocytic cell line MPRO that demonstrate expression of the TCRβ and TCRγ mRNAs and the Rag1 protein during MPRO differentiation into mature neutrophils (21, 22).

Our study establishes that athymic CD1 nude mice, which are completely deficient in T cells, express TCR Vαβ. In keeping with these observations in the mouse, the TCR was also expressed in neutrophils from two individuals with severe primary and secondary T cell deficiency syndromes (X-SCID and acute graft rejection), respectively. These findings indicate that expression of the TCR in neutrophils does not require the presence of the T cell system. Consistent evidence for TCR expression in neutrophils from T cell-deficient individuals and mouse strains lacking T lymphocytes dismisses the possibility that the presence of the TCR in neutrophils is the mere result of “passive receptor expression,” e.g., because of phagocytosis of TCR-bearing lymphocytes. This finding is also supported by the fact that we routinely detected RAG1 expression in human neutrophils, which cannot be attributed to ingestion of T cell material because RAG1 is absent from postthymic T cells.

Our findings come as a surprise considering that neutrophils are thought to rely solely on nonspecific host defense mechanisms (4). At this point, the exact biologic role of the TCR-based host defense system in neutrophils remains to be established. Also, it is presently unknown whether TCR-positive neutrophils display additional biological features that set them apart from the main neutrophil fraction. Neutrophils have a half-life of only 6–10 h in the circulation and a rapid turnover rate (23). Given these dynamic features, it is conceivable that the neutrophil TCR may represent a first line system of antigen-specific defense. Such a rapid and highly flexible immunological intervention system would make sense because it may complement the conventional T cell-based cellular host defense with its relatively slow temporal dynamics (24). The observed induction of IL-8 secretion after engagement of the neutrophil TCR raises the possibility that activation of TCR-positive neutrophils by specific antigens may potently and rapidly boost the recruitment of additional neutrophils to sites of inflammation where these antigens are present. Such a mechanism may efficiently facilitate the response to antigens during early phases of host defense.

In conclusion, we report the discovery of an as-yet-unrecognized TCR-based variable immunoreceptor in a subpopulation of human and murine neutrophils. This finding adds a novel aspect to the current understanding of the workings of neutrophils and the TCR in the mammalian immune system.

Materials and Methods

Cell Isolation and Cell Culture Experiments.

Neutrophils were isolated by dextrane sedimentation and density gradient centrifugation (FICOLL-Paque, Amersham Bioscience, Munich, Germany). Neutrophils were routinely >97% pure. T cells were enriched from peripheral blood mononuclear cells by positive selection using MACS CD3 MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch-Gladbach, Germany) (average yields >93%). Peripheral blood from an 8-week-old male infant with X-SCID was drawn before stem cell transplantation. Venous blood from a male kidney transplant patient (triple immunosuppressive therapy) (Fig. 12B) and from two healthy volunteers who were administered recombinant human G-CSF (Filgrastim, Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA) at a single dose of 30 μg s.c. was obtained at various time points. Written informed consent had been obtained from all individuals included in this study.

CD1-Foxn1nu mice, CB17/Icr-Prkdcscid/Crl mice (4 weeks old, male), and normal mice (129/SvJ and CD1) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) and maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions until the day they were killed. Neutrophils from pooled (n = 7) splenocyte cell suspensions were isolated by MACS using the Anti-Ly6G MicroBead kit (Miltenyi Biotec). The Ly6G negative mononuclear cell fraction was used as controls. Isolated neutrophils were 93% (129/SvJ and CD1 mice) and >98% pure (CD1 nude and C.B17 SCID mice), as assessed by flow cytometry (data not shown).

Promyelocytic HL-60 and Jurkat cells (DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany) were cultivated in RPMI medium 1640 (10% FCS/1% MEM). Detailed information on cell activation experiments is provided in Supporting Materials and Methods, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site.

Immunocytochemistry, Flow Cytometry, and ImmunoGold Electron Microscopy.

For immunocytochemistry and electron microscopy studies the cells were simultaneously stained with mouse anti-human monoclonal antibodies to TCRαF1 and TCRβF1 (Endogen, Bonn, Germany). Positive staining was visualized by using an Axio Imager ZI (Zeiss, Göttingen, Germany) and Axio Vision software. Flow cytometric analyses were performed on a FACSCalibur using CellQuest Pro software (Becton Dickinson Biosciences, San Jose, CA). For visualization of apoptotic neutrophils, TUNEL was performed on neutrophil cytospins using the In Situ Cell Death Detection POD Kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) followed by counterstaining with DAB (DakoCytomation, Hamburg, Germany). For ImmunoGold electron microscopy cells, human neutrophils, Jurkat cells, and sections of appendix tissue were examined in a LEO912AB electron microscope (Zeiss). For detailed description of immunocytochemistry, flow cytometry, and electron microscopy, see Supporting Materials and Methods.

RT-PCR, TCR CDR3 Size Spectratyping, and Assessment of CDR3 Sequence Diversity.

RNA from all cells was prepared with TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). cDNA was made by using the First Strand cDNA synthesis kit (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). mRNA expression levels were quantitated with the Fast Start cDNA SYBR Green Kit (Roche Diagnostics) on the Lightcycler. Data were normalized against GAPDH.

TCR Vα and Vβ mRNA expression profiling and size spectratyping of the antigen-binding Vα and Vβ CDR3 regions were performed as previously reported (11, 12). CDR3 spectratypes were assessed on an ABI 310 Genetic Analyzer capillary sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Toroed, Norway). The sequences of additional PCR primers can be requested from the authors. Authenticity of all relevant PCR products was confirmed by sequencing. PCR runs were repeated at least twice.

To assess neutrophil TCR Vα3 CDR3 sequence diversity specific RT-PCR amplification products were excised from agarose gels, purified (QIAEX II Gel Extraction Kit; Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and cloned into a TA vector (pCR-TOPO; Invitrogen, ABI 310 Genetic Analyzer) by using standard protocols. For each time point, cDNA sequences of the Vα3 CDR3 were analyzed for a total of 40 randomly picked clones.

Immunoblotting and ELISA.

Immunoblot analyses were performed with standard techniques using the following antibodies: TCRβ chain (Endogen), CD3ζ (Serotec, Oxford, U.K.), ZAP70 (Cell Signaling Technology, Boston, MA), actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), bcl-2 (DAKO, Hamburg, Germany), bcl-XL (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), RAG1 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), and RAG2 (BD Biosciences). Pilot immunoblotting experiments revealed that detection of RAG1 and RAG2 from peripheral blood leukocyte subpopulations was possible only when protein fractions were prepared with TRIzol reagent, which allows separation of cellular protein from DNA. Neutrophil IL-8 secretion was assessed by ELISA (Human IL-8 ELISA kit; Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank E. Lengyel and H. J. Schlitt for critical reading of the manuscript before submission, W. Friedrich (Children's Department, University of Ulm, Ulm, Germany) for kindly providing a peripheral blood sample from an individual with X-SCID, N. Jentsch and K. Hartmann for technical assistance, and H. Melzl for performing CDR3 spectratyping. B. K. Kraemer supplied technical and financial support.

Abbreviations

- TCR

T cell receptor

- ATRA

all-transretinoic acid

- CDR3

complementarity-determining region

- G-CSF

granulocyte colony-stimulating factor

- X-SCID

X-linked SCID

- ZAP70

ζ-chain-associated protein kinase 70

- LAT

linker for activation of T cells.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Nathan C. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:173–182. doi: 10.1038/nri1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luster AD. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:436–445. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199802123380706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welte K, Gabrilove J, Bronchud MH, Platzer E, Morstyn G. Blood. 1996;88:1907–1929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Janeway CA, Jr, Medzhitov R. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:197–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.083001.084359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fernandez-Miguel G, Alarcon B, Iglesias A, Bluethmann H, Alvarez-Mon M, Sanz E, de la Hera A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:1547–1552. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geisler C. Crit Rev Immunol. 2004;24:67–86. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v24.i1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breitman TR, Selonick SE, Collins SJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:2936–2940. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.5.2936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brenner MB, McLean J, Scheft H, Warnke RA, Jones N, Strominger JL. J Immunol. 1987;138:1502–1509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Acuto O, Michel F. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:939–951. doi: 10.1038/nri1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Venuprasad K, Parab P, Prasad DV, Sharma S, Banerjee PR, Deshpande M, Mitra DK, Pal S, Bhadra R, Mitra D, Saha B. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:1536–1543. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200105)31:5<1536::AID-IMMU1536>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pannetier C, Even J, Kourilsky P. Immunol Today. 1995;16:176–181. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80117-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Currier JR, Deulofeut H, Barron KS, Kehn PJ, Robinson MA. Hum Immunol. 1996;48:39–51. doi: 10.1016/0198-8859(96)00076-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flanagan SP. Genet Res. 1966;8:295–309. doi: 10.1017/s0016672300010168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bosma GC, Custer RP, Bosma MJ. Nature. 1983;301:527–530. doi: 10.1038/301527a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noguchi M, Yi H, Rosenblatt HM, Filipovich AH, Adelstein S, Modi WS, McBride OW, Leonard WJ. Cell. 1993;73:147–157. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90167-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gelfand EW, Dosch HM. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1983;19:65–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weissman AM, Baniyash M, Hou D, Samelson LE, Burgess WH, Klausner RD. Science. 1988;239:1018–1021. doi: 10.1126/science.3278377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan AC, Iwashima M, Turck CW, Weiss A. Cell. 1992;71:649–662. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90598-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang W, Sloan-Lancaster J, Kitchen J, Trible RP, Samelson LE. Cell. 1998;92:83–92. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80901-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang T, Yi J, Guo A, Wang X, Overall CM, Jiang W, Elde R, Borregaard N, Pei D. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:21960–21968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007997200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lian Z, Kluger Y, Greenbaum DS, Tuck D, Gerstein M, Berliner N, Weissman SM, Newburger PE. Blood. 2002;100:3209–3220. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lian Z, Wang L, Yamaga S, Bonds W, Beazer-Barclay Y, Kluger Y, Gerstein M, Newburger PE, Berliner N, Weissman SM. Blood. 2001;98:513–524. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.3.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Savill J, Haslett C. In: Immunopharmacology of Neutrophils. Hellewell PG, Williams TJ, editors. San Diego: Academic; 1994. pp. 295–314. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hellerstein M, Hanley MB, Cesar D, Siler S, Papageorgopoulos C, Wieder E, Schmidt D, Hoh R, Neese R, Macallan D, et al. Nat Med. 1999;5:83–89. doi: 10.1038/4772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leu TM, Schatz DG. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:5657–5670. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.10.5657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.