Abstract

DrugBank is a unique bioinformatics/cheminformatics resource that combines detailed drug (i.e. chemical) data with comprehensive drug target (i.e. protein) information. The database contains >4100 drug entries including >800 FDA approved small molecule and biotech drugs as well as >3200 experimental drugs. Additionally, >14 000 protein or drug target sequences are linked to these drug entries. Each DrugCard entry contains >80 data fields with half of the information being devoted to drug/chemical data and the other half devoted to drug target or protein data. Many data fields are hyperlinked to other databases (KEGG, PubChem, ChEBI, PDB, Swiss-Prot and GenBank) and a variety of structure viewing applets. The database is fully searchable supporting extensive text, sequence, chemical structure and relational query searches. Potential applications of DrugBank include in silico drug target discovery, drug design, drug docking or screening, drug metabolism prediction, drug interaction prediction and general pharmaceutical education. DrugBank is available at http://redpoll.pharmacy.ualberta.ca/drugbank/.

INTRODUCTION

Until the 1980s, most of our knowledge about drugs, drug mechanisms and drug receptors could fit in a few encyclopedic books and a couple dozen schematic figures. However, with the recent explosion in biological and chemical knowledge, this is no longer the case. There is simply too much data (images, models, structures and sequences) from too many sources. Unfortunately, most of this information still resides in textbooks or print journals. The limited drug or drug receptor data that is electronically available is either inaccessible (except through expensive subscriptions), inadequate or widely scattered among many different public databases. This state of affairs largely reflects the ‘two solitudes’ of cheminformatics and bioinformatics. Neither discipline has really tried to integrate with the other. As a consequence, the wealth of electronic sequence/structure data that exists today has never been well linked to the enormous body of drug or chemical knowledge that has accumulated over the past half century.

Recently, some notable efforts have been made to partially overcome this ‘informatics gap’. The Therapeutic Target Database or TTD is one such example (1). This very useful web-based resource contains linked lists of names for >1100 small molecule drugs and drug targets (i.e. proteins). In addition to the TTD, a number of more comprehensive small molecule databases have also emerged including KEGG (2), ChEBI (3) and PubChem (http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Each contains tens of thousands of chemical entries—including hundreds of small molecule drugs. All three databases provide names, synonyms, images, structure files and hyperlinks to other databases. Furthermore, both KEGG and PubChem support structure similarity searches. Unfortunately, these databases were not specifically designed to be drug databases, and so they do not provide specific pharmaceutical information or links to specific drug targets (i.e. sequences). Furthermore, because these databases were designed to be synoptic (containing <15 fields per compound entry) they do not provide a comprehensive molecular summary of any given drug or its corresponding protein target. More specialized drug databases such as PharmGKB (4) or on-line pharmaceutical encyclopedias such as RxList (5) tend to offer much more detailed clinical information about many drugs (their pharmacology, metabolism and indications) but they were not designed to contain structural, chemical or physico-chemical information. Instead their data content is targeted more towards pharmacists, physicians or consumers.

Ideally, what is needed is something that combines the strengths of, say, PharmGKB, PubChem and Swiss-Prot to create a single, fully searchable in silico drug resource that links sequence, structure and mechanistic data about drug molecules (including biotech drugs) with sequence, structure and mechanistic data about their drug targets. Beyond its obvious educational value, this kind of database could potentially allow researchers to easily visualize and explore 3D drug interactions, compare drug similarities or perform in silico drug (or drug target) discovery. Here, we wish to describe just such a database—called DrugBank.

DATABASE DESCRIPTION

Fundamentally, DrugBank is a dual purpose bioinformatics–cheminformatics database with a strong focus on quantitative, analytic or molecular-scale information about both drugs and drug targets. In many respects it combines the data-rich molecular biology content normally found in curated sequence databases such as Swiss-Prot and UniProt (6) with the equally rich data found in medicinal chemistry textbooks and chemical reference handbooks. By bringing these two disparate types of information together into one unified and freely available resource, we wanted to allow educators and researchers from diverse disciplines and backgrounds (academic, industrial, clinical, non-clinical) to conduct the type of in silico learning and discovery that is now routine in the world of genomics and proteomics.

The diversity of data types and the required breadth of domain knowledge, combined with the fact that the data were mostly ‘paper-bound’ made the assembly of DrugBank both difficult and time-consuming. To compile, confirm and validate this comprehensive collection of data, more than a dozen textbooks, several hundred journal articles, nearly 30 different electronic databases, and at least 20 in-house or web-based programs were individually searched, accessed, compared, written or run over the course of four years. The team of DrugBank archivists and annotators included two accredited pharmacists, a physician and three bioinformaticians with dual training in computing science and molecular biology/chemistry.

DrugBank currently contains >4100 drug entries, corresponding to >12 000 different trade names and synonyms. These drug entries were chosen according to the following rules: the molecule must contain more than one type of atom, be non-redundant, have a known chemical structure and be identified as a drug or drug-like molecule by at least one reputable data source. To facilitate more targeted research and exploration, DrugBank is divided into four major categories: (i) FDA-approved small molecule drugs (>700 entries), (ii) FDA-approved biotech (protein/peptide) drugs (>100 entries), (iii) nutraceuticals or micronutrients such as vitamins and metabolites (>60 entries) and (iv) experimental drugs, including unapproved drugs, de-listed drugs, illicit drugs, enzyme inhibitors and potential toxins (3200 entries). These individual ‘Drug Types’ are also bundled into two larger categories including all FDA drugs (Approved Drugs) and All Compounds (Experimental + FDA + nutraceuticals). DrugBank's coverage for non-trivial FDA-approved drugs is ∼80% complete. In addition, >14 000 protein (i.e. drug target) sequences are linked to these drug entries. More complete information about the numbers of drugs, drug targets and non-redundant drug targets (including their sequences) is available in the DrugBank ‘download’ page. The entire database, including text, sequence, structure and image data occupies nearly 16 gigabytes of data—most of which can be freely downloaded.

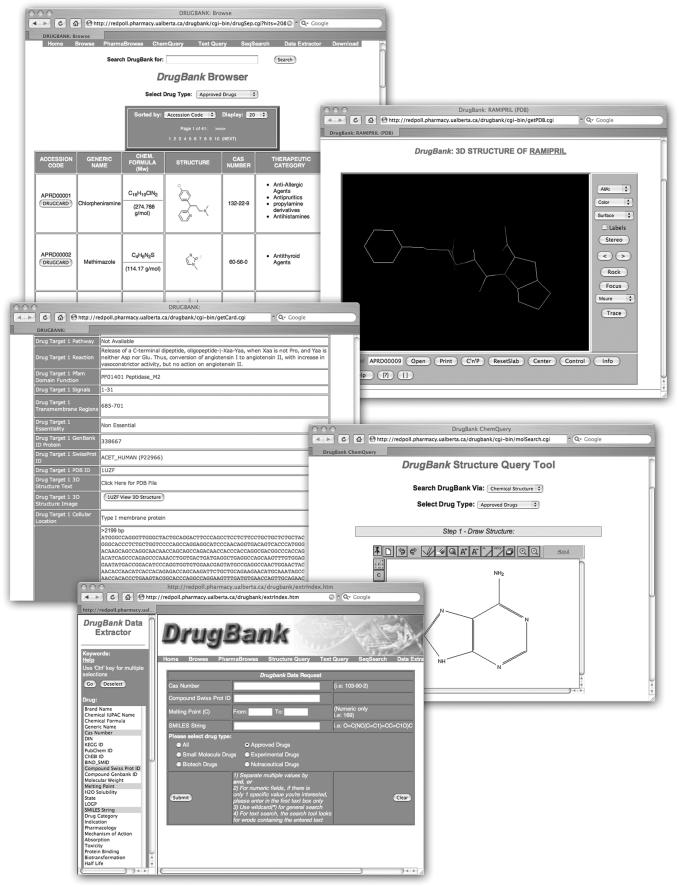

DrugBank is a fully searchable web-enabled resource with many built-in tools and features for viewing, sorting and extracting drug or drug target data. Detailed instructions on where to locate and how to use these browsing/search tools are provided on the DrugBank homepage. As with any web-enabled database, DrugBank supports standard text queries (through the text search box located on the home page). It also offers general database browsing using the ‘Browse’ and ‘PharmaBrowse’ buttons located at the top of each DrugBank page. To facilitate general browsing, DrugBank is divided into synoptic summary tables which, in turn, are linked to more detailed ‘DrugCards’—in analogy to the very successful GeneCards concept (7). All of DrugBank's summary tables can be rapidly browsed, sorted or reformatted (using up to six different criteria) in a manner similar to the way PubMed abstracts may be viewed. Clicking on the DrugCard button found in the leftmost column of any given DrugBank summary table opens a webpage describing the drug of interest in much greater detail. Each DrugCard entry contains >80 data fields with half of the information being devoted to drug/chemical data and the other half devoted to drug target or protein data (see Table 1). In addition to providing comprehensive numeric, sequence and textual data, each DrugCard also contains hyperlinks to other databases, abstracts, digital images and interactive applets for viewing molecular structures (Figure 1). In addition to the general browsing features, DrugBank also provides a more specialized ‘PharmBrowse’ feature. This is designed for pharmacists, physicians and medicinal chemists who tend to think of drugs in clusters of indications or drug classes. This particular browsing tool provides navigation hyperlinks to >70 drug classes, which in turn list the FDA-approved drugs associated with the drugs. Each drug name is then linked to its respective DrugCard.

Table 1.

Summary of the data fields or data types found in each DrugCard

| Drug or compound information | Drug target or receptor information |

|---|---|

| Generic name | Target name |

| Brand name(s)/synonyms | Target synonyms |

| IUPAC name | Target protein sequence |

| Chemical structure/sequence | Target no. of residues |

| Chemical formula | Target molecular weight |

| PubChem/KEGG/ChEBI Links | Target pI |

| Swiss-Prot/GenBank Links | Target gene ontology |

| FDA/MSDS/RxList Links | Target general function |

| Molecular weight | Target specific function |

| Melting point | Target pathways |

| Water solubility | Target reactions |

| pKa or pI | Target Pfam domains |

| LogP or hydrophobicity | Target signal sequences |

| NMR/MS spectra | Target transmembrane regions |

| MOL/SDF/PDF text files | Target essentiality |

| MOL/PDB image files | Target GenBank protein ID |

| SMILES string | Target Swiss-Prot ID |

| Indication | Target PDB ID |

| Pharmacology | Target cellular location |

| Mechanism of action | Target DNA sequence |

| Biotransformation/absorption | Target chromosome location |

| Patient/physician information | Target locus |

| Metabolizing enzymes | Target SNPs/mutations |

A more complete listing is provided on the DrugBank home page.

Figure 1.

A screenshot montage of the DrugBank Database showing several possible views of information describing the drug Ramipril. Not all fields are shown.

A key distinguishing feature of DrugBank from other on-line drug resources is its extensive support for higher level database searching and selecting functions. In addition to the data viewing and sorting features already described, DrugBank also offers a local BLAST (8) search that supports both single and multiple sequence queries, a boolean text search [using GLIMPSE; (9)], a chemical structure search utility and a relational data extraction tool (10). These can all be accessed via the database navigation bar located at the top of every DrugBank page.

The BLAST search (SeqSearch) is particularly useful as it can potentially allow users to quickly and simply identify drug leads from newly sequenced pathogens. Specifically, a new sequence, a group of sequences or even an entire proteome can be searched against DrugBank's database of known drug target sequences by pasting the FASTA formatted sequence (or sequences) into the SeqSearch query box and pressing the ‘submit’ button. A significant hit reveals, through the associated DrugCard hyperlink, the name(s) or chemical structure(s) of potential drug leads that may act on that query protein (or proteome).

DrugBank's structure similarity search tool (ChemQuery) can be used in a similar manner to its sequence search tools. Users may sketch (through ACD's freely available chemical sketching applet) or paste a SMILES string (11) of a possible lead compound into the ChemQuery window. Submitting the query launches a structure similarity search tool that looks for common substructures from the query compound that match DrugBank's database of known drug or drug-like compounds. High scoring hits are presented in a tabular format with hyperlinks to the corresponding DrugCards (which in turn links to the protein target). The ChemQuery tool allows users to quickly determine whether their compound of interest acts on the desired protein target. This kind of chemical structure search may also reveal whether the compound of interest may unexpectedly interact with unintended protein targets. In addition to these structure similarity searches, the ChemQuery utility also supports compound searches on the basis of chemical formula and molecular weight ranges.

DrugBank's data extraction utility (Data Extractor) employs a simple relational database system that allows users to select one or more data fields and to search for ranges, occurrences or partial occurrences of words, strings or numbers. The data extractor uses clickable web forms so that users may intuitively construct SQL-like queries. Using a few mouse clicks, it is relatively simple to construct very complex queries (‘find all drugs less than 600 daltons with LogPs less than 3.2 that are antihistamines’) or to build a series of highly customized tables. The output from these queries is provided as an HTML format with hyperlinks to all associated DrugCards.

QUALITY ASSURANCE, COMPLETENESS AND CURATION

Every effort is made to ensure that DrugBank is as complete, correct and current as possible. Each DrugCard is entered or prepared by one member of the curation team and separately validated by second member of the curation team. Additional spot checks are routinely performed on each entry by senior members of the curation group, including a physician, an accredited pharmacist and two PhD-level biochemists. Several software packages including text mining tools, chemical parameter calculators and protein annotation tools (10) have been modified or specifically developed to aid in DrugBank's data entry and data validation. These tools collate and display text (and images) from multiple sources allowing the curators to compare, assess, enter and correct drug or drug target information. In addition to using a CVS (Current Versioning System), all changes and edits to the central database are monitored, dated and displayed on the DrugBank ‘download’ page using a specially developed text tracking system. A second text tracking system has been implemented to monitor the completeness (0–100%) of each field (for all approved drugs) and to display up-to-date statistics on the number of drugs, drug targets and non-redundant sequences in various drug categories. This information is also displayed in the ‘download’ page. To ensure DrugBank is current, new drugs (approved and experimental) are identified using continuously running screen-scraping tools linked to the FDA, the PDB and RxList websites. Backfilling of older, more obscure and orphan drugs is ongoing and done manually. Drug targets are identified and confirmed using multiple sources (PubMed, TTD, FDA labels, RxList, PharmGKB, textbooks) as are all drug structures (KEGG, PubChem, images from FDA labels).

CONCLUSION

In summary, DrugBank is a comprehensive, web-accessible database that brings together quantitative chemical, physical, pharmaceutical and biological data about thousands of well-studied drugs and drug targets. DrugBank is primarily focused on providing the kind of detailed molecular data needed to facilitate drug discovery and drug development. This includes physical property data, structure and image files, pharmacological and physiological data about thousands of drug products as well as extensive molecular biological information about their corresponding drug targets. DrugBank is unique, not only in the type of data it provides but also in the level of integration and depth of coverage it achieves. In addition to its extensive small molecule drug coverage, DrugBank is certainly the only public database we are aware of that provides any significant information about the 110+ approved biotech drugs. DrugBank also supports an extensive array of visualizing, querying and search options including a structure similarity search tool and an easy-to-use relational data extraction system. It is hoped that DrugBank will serve as a useful resource to not only members of the pharmaceutical research community but to educators, students, clinicians and the general public.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Genome Prairie, a division of Genome Canada for financial support. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by Genome Canada.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chen X., Ji Z.L., Chen Y.Z. TTD: therapeutic target database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:412–415. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanehisa M., Goto S., Kawashima S., Okuno Y., Hattori M. The KEGG resource for deciphering the genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D277–D280. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brooksbank C., Cameron G., Thornton J. The European Bioinformatics Institute's data resources: towards systems biology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D46–D53. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hewett M., Oliver D.E., Rubin D.L., Easton K.L., Stuart J.M., Altman R.B., Klein T.E. PharmGKB: the Pharmacogenetics Knowledge Base. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:163–165. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hatfield C.L., May S.K., Markoff J.S. Quality of consumer drug information provided by four web sites. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 1999;56:2308–2311. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/56.22.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bairoch A., Apweiler R., Wu C.H., Barker W.C., Boeckmann B., Ferro S., Gasteiger E., Huang H., Lopez R., Magrane M., et al. The Universal Protein Resource (UniProt) Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D154–D159. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rebhan M., Chalifa-Caspi V., Prilusky J., Lancet D. GeneCards: a novel functional genomics compendium with automated data mining and query reformulation support. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:656–664. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.8.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Altschul S.F., Madden T.L., Schaffer A.A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W., Lipman D.J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manber U., Bigot P. USENIX Symposium on Internet Technologies and Systems (NSITS'97) Monterey, CA: 1997. pp. 231–239. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sundararaj S., Guo A., Habibi-Nazhad B., Rouani M., Stothard P., Ellison M., Wishart D.S. The CyberCell Database (CCDB): a comprehensive, self-updating, relational database to coordinate and facilitate in silico modeling of Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D293–D295. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weininger D. SMILES 1. Introduction and encoding rules. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 1988;28:31–38. [Google Scholar]