Abstract

With the available eukaryotic genome sequences, there are predictions of thousands of previously uncharacterized genes without known function or available mutational variant. Thus, there is an urgent need for efficient genetic tools for genomewide phenotypic analysis. Here we describe such a tool: a deletion-generator technology that exploits properties of a double transposable element to produce molecularly defined deletions at high density and with high efficiency. This double element, called P{wHy}, is composed of a “deleter” element hobo, bracketed by two genetic markers and inserted into a “carrier” P element. We have used this P{wHy} element in Drosophila melanogaster to generate sets of nested deletions of sufficient coverage to discriminate among every transcription unit within 60 kb of the starting insertion site. Because these two types of mobile elements, carrier and deleter, can be found in other species, our strategy should be applicable to phenotypic analysis in a variety of model organisms.

A major challenge in the model higher eukaryotes (1–5) is to understand the biological contributions of each gene product. Insights from sequence comparisons, structural analysis, mRNA predictions and microarray expressions studies (6) must be complemented by phenotypic analysis through gene-disruption strategies that can be applied effectively on a global basis.

Several basic strategies for gene-disruption and phenotypic analysis are now available; in this report we will focus on a technique that can be applied globally in Drosophila melanogaster. In addition to conventional random-mutagenesis techniques, targeted approaches such as RNA interference (7) and targeted gene knockouts (8) are available in D. melanogaster. These techniques have the advantage that individual genes can be focused on; they have the disadvantage that individual constructs, injection series, and for some approaches stable transgenic lines need to be produced. These disadvantages make the techniques better suited to individual applications than to global approaches, at least as far as disruptions of gene activity in intact animals are concerned. Another approach is to use mobile elements as mutagens, a strategy better suited to global application, because an individual stable transgenic construct can be transposed to many sites in the genome by a simple series of genetic crosses. Problems with this approach are that as much as half the genome is refractory to P element insertion at usable rates, and that many mutations are leaky because of insertion-site preference 5′ to the transcription start site (9).

An alternative approach is to inactivate gene function with deletions by exploiting the intrinsic property of certain mobile elements (such as the hobo or H element) to undergo homologous recombination with one another in the presence of a source of transposase (10, 11). If the two mobile elements are in the vicinity of one another, the recombination event resolves as a deletion of the intervening genomic material. This recombinogenic property has led to the suggestion that deletions can be generated throughout the genome by appropriate selection of pairs of P elements spanning a gene of interest (12, 13). Although this approach is effective on an individual basis, it generally depends on the identification of marker genes in a particular interval and is limited by the availability of P element insertion sites.

Here we report an approach for deletion generation that can be applied more readily to the genome as a whole, because the deletion-detection system is contained entirely within the transgenic construct. Our example of this approach, using the P{wHy} element in D. melanogaster, generates deletions as large as 400 kb and with a fine-grained distribution of nested deletions within 60 kb on either side of a single insertional starting point in the genome. This deletion-generator system exploits the local transpositional and recombinational properties of the hobo mobile element. Analogous components of P{wHy} are available in other model organisms. Hence, we believe that this approach will be applicable to genomewide phenotypic analysis in several model systems.

Methods

Genetic Scheme for hobo-Mediated Deletions.

All initial D. melanogaster strains used for deletion generation had genetic backgrounds devoid of hobo elements (E lines) as determined by Southern analysis (10). hobo-mediated deletions were generated by using two P{wHy} insertions on chromosome 2. G0 crosses were matings of Df (1)w67c23, y1 w67c23; P{wHy,w+y+} with Df (1)w67c23, y1 w67c23; In (2LR)Gla, wgGla-1/CyO P{hsH\T-2}. P{hsH\T-2} contains the hobo transposase gene placed under a heat-shock promoter. Crosses were brooded three times every other day. The progeny were heat-shocked three times during development for 30 min at 37°C at 2-day intervals to elevate the expression of the hobo transposase. Each G1 cross consisted of two males of the genotype y1 w67c23; P{wHy}/CyO, P{hsH\T-2} and virgin females of the genotype y1 w67c23; In (2LR)Gla, wgGla-1/SM6a. G2 matings consisted of one y1 w67c23; P{5′wHy,w+y−} or P{3′wHy,w−y+}/SM6a male crossed to virgin y1 w67c23; In (2LR)Gla, wgGla-1/SM6a females. From these latter crosses, stocks of the P{5′wHy} or P{3′wHy} derivatives were established, balanced with SM6a.

Distinction Between P{wHy}-Confined Events and Genomic Events by PCR.

A single PCR test was used to identify deletion events confined to the P{wHy} element based on the retention of both P element ends. The derivatives that failed to amplify a PCR product by using the primers were classified as genomic events and retained for further analysis. PCR tests were performed in 96-well plates by using single-fly DNA extracts. 5′ and 3′ reactions were run simultaneously to provide internal controls. The primers were: P element, CGACGGGACCACCTTATGTT; P{wHy}01D01 5′ primer, TGTTCGCTAATGCTGAACC; P{wHy}01D01 3′ primer, CCGGCGAGGAATTTGTACAT; P{wHy}01D09 5′ primer, CACTCAGCTGGTTGATTTCG; and P{wHy}01D09 3′ primer, TGAGTAAGACTGAGCCCACT.

Deletion Mapping.

The inverse PCR protocol of J. Rehm of the Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project for determining flanking sequence is available at www.fruitfly.org/about/methods/inverse.pcr.html. The protocol was followed except for the use of the restriction enzyme and the primers. The restriction enzyme was AluI, and the primers were: hobo 5′-end reaction primers, ACGCAAAACACCGTATTGATTCGG and CGTAGGTAGTCGAGTCAAATGGC; 5′-sequencing primer, GATGTGCGTGGCGAGTAGCACCC, hobo 3′-end reaction primers, AGGAGGCTATCTACAGATTTTGG and GATCGTTGACTGTGCGTCCACTCA; and 3′-sequencing primer, GAGTACCGAGTGTTTATCGGGTGG.

The universal fast-walking method, developed in our laboratory during the course of this project, is a more effective alternative to inverse PCR for primer-based amplification of sequences adjacent to the P element or hobo-element termini (14). For hobo the 5′-flanks universal fast-walking primers, listed in their order of use, were: h5-1, ACTACCTACGAGACCACTCG; h5-2, TTTAGGCACTGTGTGAGCGGNNNNNNNNNN; h5-3, TAACGGTATACCCACAAGTG; h5-4, ACGCAAACACCTATTGATTCGG; and h5-5, GATGTGCGTGGCGAGTAGCACCC. For hobo the 3′-flanks universal fast-walking primers were: h3-1, CCGAATCAATACGGTGTTTTGCGT; h3-2, CGAGTGGTCTCGTAGGTACTNNNNNNNNNN; h3-3, CACTTGTGGGTATACCGTTA; h3-4, GATCGTTGACTGTGCGTCCACTCA; and h3-5, ACACAACGTCGGTAAAACACTCGA. The first-strand/final extension-time combination was 15/90 s for all 5′ flanks and the 3′ flanks, 70/150 s for some samples, and 15/40 s for others.

Complementation Tests.

The lethality of the P insertions dap04454 (15), dve01738 (16), EP(2)2600 (17), and Uab1s3484 (9) were verified with independent deletions, all of which were obtained from the Bloomington Stock Center (Bloomington, IN). The complementation crosses were performed by using males carrying the hobo-induced deletions with female testers. All the progeny were scored, and crosses producing fewer than 100 progeny were repeated.

GenBank Accessions.

The sequences described here are available from GenBank as follows: the P{wHy} transgene structure, accession no. AF516513; the original P{wHy}01D01 insertion site, accession no. BH772818; the derivative 01D01W deletion endpoints, accession nos. BH770109–BH770205; the original P{wHy}01D09 insertion site, accession no. BH772819; and the derivative 01D09Y deletion endpoints, accession nos. BH770206–BH770318. Three 01D01W deletion endpoint sequences were below the acceptable limit for GenBank: 01D01W-L204, GCCAGAGCGATCCTTAATTGCGTAAGAAACGAGAAAACATTAAGCT; 01D01W-L205, GGTCTGGAGCTGCGCCTTCATCTCGACTCACTTCATGTCAAGCGCATTTAA; and 01D01W-L206, CCCTAAAGTGCTGAGATCACCTGTGCAAATGTTTATTCCAGCT.

Results and Discussion

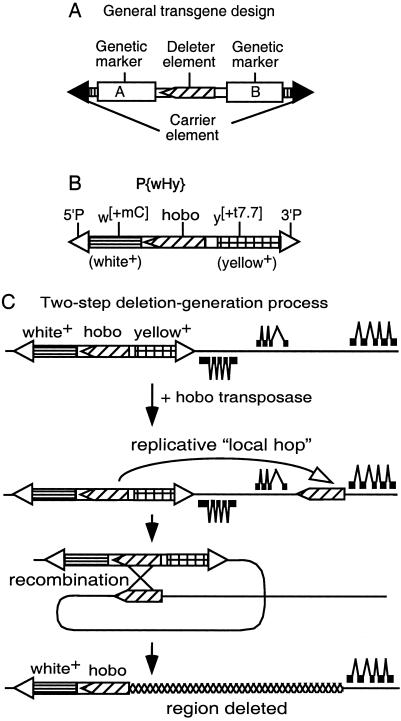

We have developed a technology (Fig. 1) that can rapidly generate nested deletion arrays starting with the insertion of a single-copy transgenic construct at any location in the genome. The general features of this system (Fig. 1A) are that it contains two independent mobile-element systems that are incapable of cross-mobilization. The outer “carrier” element contributes mobile-element termini sufficient to transport the entire transgenic construct to alternative genomic locations in the presence of the enzymes necessary to catalyze its mobilization. The inner “deleter” mobile element is one that has a high frequency of replicative mobilizations to nearby genomic sites (hereafter referred to as “local hops”) catalyzed by its mobilization enzymes. Further, when a local hop inserts in the same 5′-to-3′ orientation as the starting deleter element, then there is a high probability of recombination between the two copies of the element, leading to the production of genomic-deletion and tandem-duplication events. The genetic markers A and B bracketing the deleter element allow directional detection of the deletion events through the loss of one of the two genetic markers.

Figure 1.

The hybrid transposon P{wHy} and its use for generating unidirectional deletions. (A) Scheme for a general compound mobile element containing two markers and a deleter inserted into a carrier element. (B) P{wHy} consists of P5′-w[+mC]-hobo-y[+t7.7]-P3′ (hobo, oriented 5′ to 3′, and the flanking white and yellow markers reside within P element ends). (C) General scheme for P{wHy}-generated unidirectional deletions. A single P{wHy} insertion is adjacent to genes transcribed from both strands of DNA (thick line). After local hobo hopping followed by intrachromosomal recombination between the directly oriented hobo elements, one marker (in this case yellow) along with two proximal genes is excised. The deletion is selected on the basis of the expression of the remaining marker. If the orientation of the second hobo were reversed, an inversion would occur (10).

We have implemented this general strategy in D. melanogaster by constructing an element that we term P{wHy} (Fig. 1B) in which the P element serves as the carrier, the hobo element serves as the deleter, and the genetic markers w+ (the engineered derivative of a wild-type allele of the white eye-color gene) and y+ (the wild-type allele of the yellow body-color gene) provide the detection system for the directional detection of deletion events. The carrier P element can be mobilized only in the presence of a source of P transposase within the genome, and similarly, the deleter hobo element can be mobilized only in the presence of a source of hobo transposase. Based on work we carried out on hobo transposase-mediated mobilizations of a preexisting single defective hobo element located within the decapentaplegic (dpp) locus in Drosophila (ref. 10 and L.R.B., M.A.C., and W.M.G., unpublished data), deletion events in which one endpoint of the deletion falls exactly at the end of a hobo element can be obtained readily through introduction of a source of hobo transposase. The interpretation of the origin of these events is a two-step process that occurs at sequential times within the divisions of a single germ line: (i) local hops of hobo are generated at a high rate after exposure to hobo transposase followed by (ii) transposase-mediated intrachromosomal recombination between the original hobo and the transposed copy residing nearby in the same orientation (10, 18, 19). By bracketing the hobo element in P{wHy} with functional transgenes for w+ and y+, recombinational events following local hop of hobo in the same orientation into a nearby genomic location result not only in the loss of the intervening genomic material but also of the w+ or y+ marker gene on that side of the P{wHy} element (Fig. 1C). Thus, deletions can be detected purely on the basis of the markers internal to P{wHy} without regard to the extent of the genomic deletion.

For the P{wHy} system to be useful for global deletion analysis, three criteria need to be met: (i) distribution (deletions must occur over a broad size range), (ii) granularity (deletions typically must have different end points, reflecting a broad distribution of insertion sites produced by local hopping), and (iii) frequency (the system must be efficient enough to produce a large number of deletions with reasonable effort).

To investigate the ability of this system to meet these criteria, we have generated several single-copy P{wHy} autosomal insert lines. Of these, we chose for intensive analysis the first two lines we encountered that, at that time, were inserted into a large contiguous block of finished genomic sequence deposited in GenBank. Flies from these lines, P{wHy} CG1293001D09 and P{wHy} 01D01, were crossed to a source of hobo transposase as described in Methods. The progeny of this cross containing P{wHy} and hobo transposase were test-crossed to y1 w67c23 flies. Their progeny were scored for the two phenotypic classes, w+y− and w−y+, expected for deletion events. For each line, we recovered these two phenotypic classes. We will focus on the characterization of the two nested deletion series for which we have the most extensive data sets (Table 1). The hobo mobilization frequencies encountered in the two cases, 404/1,539 (26%) and 363/1,870 (19%), respectively, of the male germ lines tested (Table 1) are typical for other P{wHy} lines (ref. 21 and F.H., J.T.L., T. Martin, M.A.C., and W.M.G., unpublished data).

Table 1.

Isolation and characterization efficiency for two P{wHy} deletion sets

| Characterization steps | 01D09Y* | 01D01W† |

|---|---|---|

| Fertile G1 crosses | 1,539 | 1,870 |

| hobo mobilization derivatives | 404 | 363 |

| Viable fertile derivatives | 354 | 351 |

| Genomic events | 233 | 215 |

| Genomic events mapped | 153 | 164 |

| Candidate deletions | 127 | 119 |

| Nonredundant deletions | 114 | 105 |

| Validated deletions | 113 | 100 |

| Deletions <60 kb | 78 | 74 |

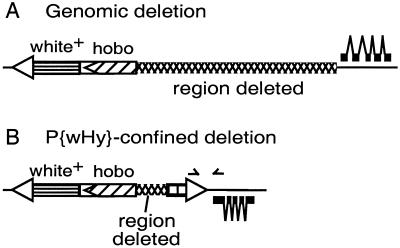

The recovered hobo mobilization derivatives were subjected to a three-step characterization procedure. The first step culled the hobo mobilization events in which the white or yellow marker genes are inactivated or deleted by events occurring solely within the P{wHy} element (Fig. 2B). Derivatives that pass this first step are classified as “genomic events” (Fig. 2A). Although the occurrences of P{wHy}-confined events are substantial (≈1/3 of the total transmitted events), they are detected readily and eliminated at an early stage of analysis and thus do not detract from the overall efficacy of the system.

Figure 2.

Distinguishing between mobilization events confined to the P{wHy} transgene and deletion events extending into the adjacent genomic region. (A) A genomic event extends from one end of the hobo element, removes one of the marker genes, one P element terminus, and some adjacent genomic material (indicated with crosshatching). (B) An event confined to the P{wHy} transgene: a small deletion extending from one end of the hobo element and removing part of the yellow transgene, thereby inactivating it. The approximate positions of the two PCR primers that are used to screen for a PCR product diagnostic of P{wHy}-confined events are indicated by the two arrowheads.

The second step of characterization of the genomic events consisted of sequence mapping of the DNA adjacent to the relevant hobo terminus. By means of two primed genomic sequencing techniques (inverse PCR and universal fast walking; see Methods), the sequence flanking the terminus of the hobo adjacent to the genomic event was obtained for ≈70% of the genomic events (Table 1). Each flanking sequence then was aligned to the Drosophila genomic sequence (1) by using BLAST (20). “Candidate deletions” were selected on the basis of the following criteria: (i) the hobo-flanking genomic sequence is located in the vicinity of the original insertion site, (ii) the flanking sequence is on the expected side of the original insertion relative to the phenotypic marker lost, (iii) the flanking sequence is in the proper orientation relative to the hobo end, (iv) hobo is detected in only one copy, and (v) hobo is not flanking a transposon or repetitive sequence. Candidate deletions turned out to be the bulk of genomic events: 83% for P{3′wHy,w−y+}01D09Y (hereafter termed 01D09Y) deletions and 72% for P{5′wHy,w+y−}01D01W (hereafter termed 01D01W). The loss of one of the two phenotypic markers thus is an excellent predictor of deletions among genomic events.

Very few of the candidate deletion endpoints are identical in extent. Only 14/127 and 14/119 endpoints occur more than once in the 01D09Y and 01D01W series, respectively (Table 1). We conclude that multiple occurrences of the same deletion endpoints arise with a sufficiently low frequency that they do not hinder implementation of this system. In other words, local hopping produces many different hobo insertion sites and leads to a broad series of nested deletions.

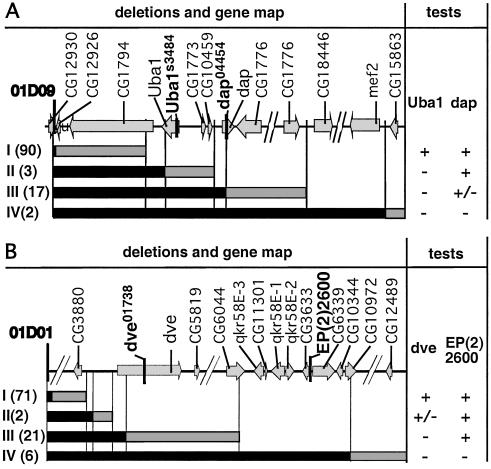

If the candidates identified by these molecular analyses are true deletions and are of sufficient extent, they should uncover genetic markers within the deleted regions. Therefore, for the third step of characterization, complementation tests with molecularly localized recessive mutations were performed. Four recessive lethal P element insertion mutations were used: Uba1s3484 and dap04454 for the 01D09Y deletion set (Fig. 3A) and dev01738 and EP(2)2600 for the 01D01W deletion set (Fig. 3B). As expected, candidate deletions predicted to uncover these mutant transcription units fail to complement these mutants (Fig. 3). Only 1 exception of 114 01D09Y deletions and 5 exceptions of 105 01D01W deletions were encountered (Table 1). These exceptions may have been generated by a double event, a small deletion confined to the P{wHy} transgene, and a secondary local hobo insertion. We conclude that for the two sets of deletions, the vast majority of the candidate deletions behave as expected in the complementation tests and thus are validated deletions.

Figure 3.

Diagrammatic representation of deletion complementation results. Molecularly mapped genes within the 350–400-kb regions subject to analysis are shown at the top of A and B. Tester mutations used for lethal complementation analysis are shown in boldface. The maps are not to scale; discontinuities are indicated by diagonal breaks. Deletions were grouped according to complementation behavior into subsets I–IV for each deletion series. Results of the complementation tests are shown at the right as + (viable), +/− (semilethal), or − (lethal). Vertical lines relate the complementation groups to the molecular map. (A) Complementation tests with P{3′wHy} 01D09Y deletions. The two lethal P insertions are Uba1s3484 and dap04454. Relative to the insertion site, the second deletion endpoints map as follows: subset I from 455 to 78,060 bp, subset II from 82,399 to 101,979 bp, subset III from 103,627 to 263,393 bp, and subset IV from 329,337 to 353,318. The semilethality phenotype of l(2) dap04454 null allele is confirmed (15). A total of 114 nonredundant deletions have been assayed, and 113 are classified as validated. One exception, an endpoint that maps with subset III, is viable over dap04454. (B) Complementation tests with P{5′wHy}01D01W deletions. The two P lethal insertions are dve01738 and EP(2)2600 (inserted between the predicted genes CG3633 and CG6339). Relative to the insertion site, the second deletion endpoints map as follows: subset I, from 216 to 42,756 bp, subset II from 46,123 to 46,658 bp, subset III from 53,165 to 211,901 bp, and subset IV from 247,344 to 398,322. A total of 105 nonredundant deletions have been assayed, and of these, 100 deletions are classified as validated deletions. Five exceptions that are viable over both dve01732 and EP (2)2600 have been found. These exceptional cases may represent complex mobilization events.

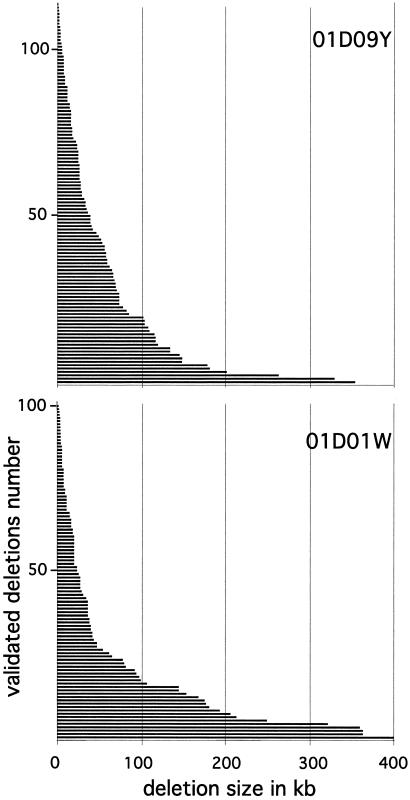

One of our key objectives was to assess the ability of this system to achieve “nested deletion saturation,” which produces deletion sets with endpoints staggered such that the transcription units in the flanking region are separable genetically. The molecular extent of recovered deletions ranges from 216 bp to 400 kb of adjacent genomic DNA. The overall size distribution (Fig. 4) of the validated deletions is consistent between the two reported sets (and among other less extensive sets, data not shown). The density of deletions falls off with distance, resulting in a higher number of deletions in the vicinity of the insertion site.

Figure 4.

Distribution of the extents of the validated and nonredundant deletions of P{3′wHy}01D09Y (113 deletions) and P{5′wHy}01D01W (100 deletions). The solid bars represent deletions (length in kb). (See Methods for GenBank accession nos. of the deletion endpoints.)

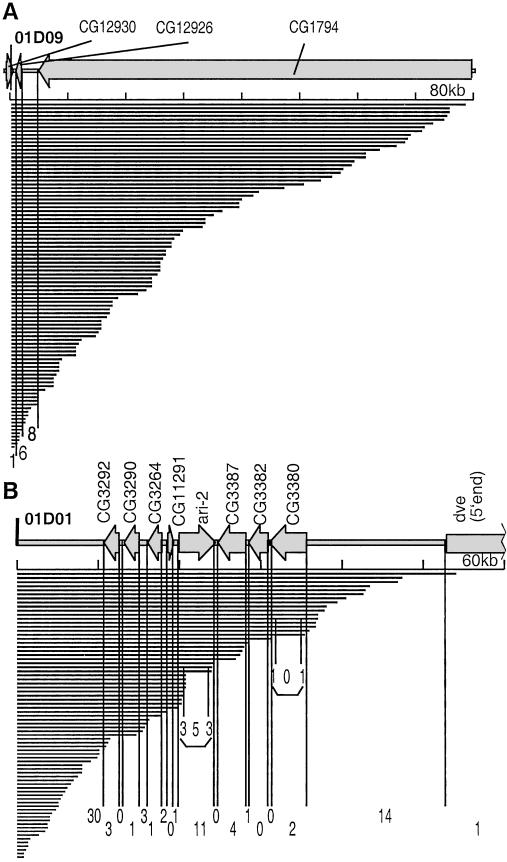

To define the region within which nested deletion saturation can be achieved, we compared the deletion boundary distribution and transcription unit locations in the vicinity of the two P{wHy} insertions. For the two sets of 100 and 113 validated deletions, it seems that ≈60 kb represents a reasonable range within which a high density of deletions is recovered (Fig. 5). The 01D09Y 60-kb region has only three putative genes in 60 kb (low gene density; ref. 1; Fig. 5A). All three transcription units in the 01D09Y 60-kb region are separated by deletion breakpoints. In the 01D01W 60-kb region, each transcription unit is separated by at least one deletion boundary from the neighboring transcription unit, which is true even within a genetically dense 23-kb subregion containing eight transcription units (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Deletions within 60 kb of the P{wHy} CG1293001D09 and P{wHy} 01D01 insertions discriminate among all transcription units. This diagram zooms in on Fig. 4. The distribution of deletion endpoints (solid bars) and mRNAs (arrows) are compared. The thick line denotes the DNA. The vertical divisions are provided to indicate the number of endpoints falling within (and between) mRNAs based on current knowledge of gene boundaries in the region. The horizontal axis is calibrated every 10 kb. The diagram was made by using GenBank annotation and the Vector NTI Suite program. The intron-exon structure is not shown. (A) Diagram of a gene-poor region near P{wHy} CG1293001D09. The 80-kb map fully spans CG1794. (B) A gene-rich region near P{wHy} 01D01. Endpoints located in the untranslated terminal regions of the ari-2 and CG3380 transcripts are indicated also.

Conclusions

The P{wHy} technique should make significant contributions to the phenotypic annotation of the Drosophila genome. In the two regions that we investigated in detail here, we see features that are very encouraging regarding the general application of this methodology. Specifically, we find that hobo transposase-mediated P{wHy} deletions are recovered at sufficient frequencies to enable the detailed dissection of the molecular vicinity of an insertion. Within 60 kb of an insertion site, a collection of 100 deletions (a reasonable collection that could be generated from ≈1,000–2,000 initial mobilization crosses) would produce a nested deletion series in which endpoints would be staggered every 1–3 kb. Beyond this 60-kb distance, there would be occasional deletions as well, but the distances between adjacent endpoints would be considerably larger. Thus, for most regions of the genome, we would expect deletions to separate transcription units reliably within ≈60 kb on either side of the initial P{wHy} insertion site.

There are two obvious applications of P{wHy} deletions for phenotypic annotation of the genome. In one, nested deletions can be used for complementation of known recessive mutations that have been localized to a specific cytogenetic (or molecular) region. In the other, nested deletions from P{wHy} inserts in the vicinity of one another are generated, and through inter se crosses transheterozygous pairs of deletions are produced that remove both allelic copies of one or a cluster of transcription units. This approach would allow the association of phenotype with elimination of a specific genomic region in a systematic way. The same set of nested deletions could be used to assess the null phenotypes produced by loss of many transcription units in a given region, independent of the existence of other genetic reagents in that region. We have established that both the complementation test and overlapping deletion assay systems can be exploited effectively with the P{wHy} system (21).

The P{wHy} system has the additional feature that phenotypes are associated with the deletion of a specific set of base-pair locations in the genome; thus, even if the transcription unit models in a given genomic region are revised (as many inevitably will be over the next several years), these genomically defined phenotypic data will migrate easily forward to the new annotations. Further, this technique will allow the discovery of important functions in noncoding sequences in general and, in particular, noncoding transcripts and small transcripts such as micro-RNAs (22). Gene clusters of related function (23) can be eliminated, allowing studies of their aggregate contributions to phenotype.

Given the ability to recover finely staggered deletion endpoints within 60 kb of an insertion site, ≈2,000 P{wHy} insertions regularly spaced over the genome would be sufficient to produce a comprehensive set of deletions covering the entire euchromatic genome.

Finally, this technology should be applicable to a broad set of eukaryotic genomes for which carrier and deleter elements are already available. The carrier element that can be moved in single copy to many integration sites throughout the genome can be the Mos element in Caenorhabditis elegans (24), Minos and piggyBac in a variety of dipterans and other insects (25), Minos in human cells (26), transfer DNA in plants (27), gene-trap vectors (28) and the transposon Sleeping Beauty (29, 30) in mouse, and several retroviruses and transposons in zebrafish (31). The second essential component, the deleter hobo-like element, belongs to the hAT superfamily of transposable elements (18, 32) found in plants (Ac and Tam3), fungi (Tfo1), fish (Tol2), and mammals (Tramp). Ac is known to undergo mainly local transposition in Arabidopsis (33) and tobacco (34). Offset recombinational events were described first in maize as triggering the classical breakage–fusion–bridge cycles (35) and also have been illustrated in bacteria (36). All these data suggest that hobo or other hAT members can be used as deleter elements in non-Drosophila eukaryotes. Overall, because of the existence of comparable deleter and carrier elements, we anticipate that the deletion-generator strategy will have applications in many model organisms.

Acknowledgments

We thank Todd M. Martin and Genya Kraytsberg for technical assistance and Heather B. Adkins for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by a Public Health Services (National Institutes of Health) Grant 5 R37 GM28669 (to W.M.G.).

Footnotes

Data deposition: The sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in the GenBank database (P{wHy} transgene structure, accession no. AF516513; original P{wHy}01D01 insertion site, accession no. BH772818; derivative 01D01W deletion endpoints, accession nos. BH770109–BH770205; original P{wHy}01D09 insertion site, accession no. BH772819; derivative 01D09Y deletion endpoints, accession nos. BH770206–BH770318).

See commentary on page 9607.

References

- 1.Adams M D, Celniker S E, Holt R A, Evans C A, Gocayne J D, Amanatides P G, Scherer S E, Li P W, Hoskins R A, Galle R F, et al. Science. 2000;287:2185–2195. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Caenorhabditis elegans Sequencing Consortium. Science. 1998;282:2012–2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Arabidopsis Genome Initiative. Nature (London) 2000;408:796–812. doi: 10.1038/35048692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium. Nature (London) 2001;409:860–921. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Venter J C, Adams M D, Myers E W, Li P W, Mural R J, Sutton G G, Smith H O, Yandell M, Evans C A, Holt R A, et al. Science. 2001;291:1304–1351. doi: 10.1126/science.1058040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vukmirovic O G, Tilghman S M. Nature (London) 2000;405:820–822. doi: 10.1038/35015690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kennerdell J R, Carthew R W. Cell. 1998;95:1017–1026. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81725-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rong Y S, Golic K G. Science. 2000;288:2013–2018. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5473.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spradling A C, Stern D, Beaton A, Rhem E J, Laverty T, Mozden N, Misra S, Rusin G M. Genetics. 1999;153:135–177. doi: 10.1093/genetics/153.1.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blackman R K, Grimaila R, Koehler M M D, Gelbart W M. Cell. 1987;49:497–505. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90452-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lim J K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;85:9153–9157. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.23.9153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooley L, Thompson D, Spradling A C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:3170–3173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.8.3170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Preston C R, Sved J A, Engels W R. Genetics. 1996;144:1623–1638. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.4.1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Myrick K V, Gelbart W M. Gene. 2002;284:125–131. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)00384-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Nooij J C, Letendre M A, Hariharan I K. Cell. 1996;87:1237–1247. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81819-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fusse B, Hoch M. Mech Dev. 1998;79:83–97. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00172-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liao G-C, Rehm E J, Rubin G M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:3347–3351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050017397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calvi B R, Hong T J, Findley S D, Gelbart W M. Cell. 1991;66:465–471. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lim J K, Simmons M J. BioEssays. 1994;16:269–275. doi: 10.1002/bies.950160410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schaffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mohr, S. E. & Gelbart, W. M. (2002) Genetics, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Ambros V. Cell. 2001;107:823–826. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00616-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rubin G, M, Yandell M D, Wortman J R, Gabor Miklos G L, Nelson C R, Hariharan I K, Fortini M E, Li P W, Apweiler R, Fleischmann W, et al. Science. 2000;287:2204–2215. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bessereau J L, Wright A, Williams D C, Schuske K, Davis M W, Jorgensen E M. Nature (London) 2001;413:70–74. doi: 10.1038/35092567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Brochta D A, Atkinson P W. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1996;26:739–753. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(96)00022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klinakis A G, Zagoraiou L, Vassilatis D K, Savakis C. EMBO Rep. 2000;1:416–421. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krysan P J, Young J C, Sussman M R. Plant Cell. 1999;11:2283–2290. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.12.2283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stanford W L, Cohn J B, Cordes S P. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:756–768. doi: 10.1038/35093548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horie K, Kuroiwa A, Ikawa M, Okabe M, Kondoh G, Matsuda Y, Takeda J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:9191–9196. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161071798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fischer S E J, Wienholds E, Plasterk R H A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:6759–6764. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121569298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patton E E, Zon L I. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:956–966. doi: 10.1038/35103567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rubin E, Lithwick G, Levy A A. Genetics. 2001;158:949–957. doi: 10.1093/genetics/158.3.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Machida C, Onouchi H, Koizumi J, Hamada S, Semiarti E, Torikai S, Machida Y. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:8675–8680. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Semiarti E, Onouchi H, Torikai S, Ishikawa T, Machida Y, Machida C. Genes Genet Syst. 2001;76:131–139. doi: 10.1266/ggs.76.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McClintock B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1950;36:344–355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.36.6.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kleckner N, Roth J, Botstein D. J Mol Biol. 1977;116:125–159. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(77)90123-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]