Abstract

UvrB, the ultimate damage-recognizing component of bacterial nucleotide excision repair, contains a flexible β-hairpin rich in hydrophobic residues. We describe the properties of UvrB mutants in which these residues have been mutated. The results show that Y101 and F108 in the tip of the hairpin are important for the strand-separating activity of UvrB, supporting the model that the β-hairpin inserts between the two DNA strands during the search for DNA damage. Residues Y95 and Y96 at the base of the hairpin have a direct role in damage recognition and are positioned close to the damage in the UvrB–DNA complex. Strikingly, substituting Y92 and Y93 results in a protein that is lethal to the cell. The mutant protein forms pre- incision complexes on non-damaged DNA, indicating that Y92 and Y93 function in damage recognition by preventing UvrB binding to non-damaged sites. We propose a model for damage recognition by UvrB in which, stabilized by the four tyrosines at the base of the hairpin, the damaged nucleotide is flipped out of the DNA helix.

Keywords: damage recognition/DNA repair/nucleotide flipping/UvrB

Introduction

One of the most intriguing aspects of nucleotide excision repair (NER) is its capacity to recognize and repair a large variety of structurally unrelated DNA damage. Damage recognition during bacterial NER is a multistep process, involving both the UvrA and UvrB proteins. The UvrA protein on its own binds preferentially to damaged DNA (Seeberg and Steinum, 1982; Mazur and Grossman, 1991; Thiagalingam and Grossman, 1991) via an as yet unknown mechanism, indicating that this protein must contain damage-recognizing determinants. It is generally thought that during the repair reaction, UvrA initially recognizes damage as part of the UvrA2B complex. This complex binds to the DNA at a random site and wraps the DNA around the UvrB protein (Verhoeven et al., 2001). When no damage is detected at or near this site, the protein complex dissociates from the DNA, most probably as a result of ATPase-driven conformational changes in the UvrA protein (Oh et al., 1989; Orren and Sancar, 1989; Mazur and Grossman, 1991). When, however, an abnormality in the DNA structure is detected, the DNA is probed again by the UvrB protein. This requires the ATPase and helicase activities of UvrB (Moolenaar et al., 1994) and, when damage is detected, the pre-incision complex is formed where UvrB is stably bound to the damaged site and UvrA is released. UvrC binds to the pre-incision complex and incises the DNA, first on the 3′ side of the damage, followed by incision on the 5′ side (Lin and Sancar, 1992; Verhoeven et al., 2001). The 5′ incision is usually followed by an additional 5′ incision, seven nucleotides further away. This additional incision has been shown to be UvrA and damage independent, since non-damaged DNA substrates carrying a single-stranded nick are also incised seven nucleotides from the nick by UvrBC (Moolenaar et al., 1998).

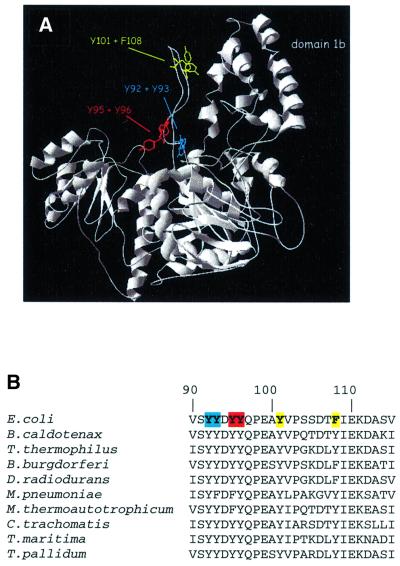

Damage recognition by UvrB per se does not require the presence of the UvrA protein. This has been shown by the damage-specific binding of the UvrB protein alone to substrates that contain the damage close to the end of a DNA fragment (Moolenaar et al., 2000a). The crystal structures of the UvrB proteins from Bacillus caldotenax (Theis et al., 1999) and Thermus thermophilus (Machius et al., 1999; Nakagawa et al., 1999) have been determined. The fold of the protein shows similarities to that of the helicases NS3 (Kim et al., 1998), PcrA (Velankar et al., 1999) and Rep (Korolev et al., 1997), in particular with respect to the ATP-binding domains. Most probably, ATP hydrolysis by UvrB is coupled to domain motion, which eventually leads to formation of the pre-incision complex. A striking feature of the structure of the UvrB protein is the presence of a flexible β-hairpin that is rich in conserved hydrophobic residues (Figure 1B). It has been proposed that this β-hairpin is important for the stable binding of UvrB to DNA (Machius et al., 1999; Nakagawa et al., 1999; Theis et al., 1999). Possibly, the β-hairpin inserts between the two strands of the DNA helix, thereby locking one single strand between the β-hairpin and the adjacent domain 1b (Figure 1A). It has been shown that the UvrB binding to DNA is salt resistant, suggesting hydrophobic interactions between UvrB and the DNA (Yeung et al., 1986; Orren and Sancar, 1989). The hydrophobic residues in the β-hairpin might be involved in such hydrophobic interactions, via stacking between the bases.

Fig. 1. (A) Crystal structure of the UvrB protein from B.caldotenax (Theis et al., 1999). The residues in the β-hairpin that have been substituted in E.coli UvrB are indicated. Note that F108 of E.coli UvrB corresponds to a tyrosine in the B.caldotenax protein. (B) Alignment of sequences of the β-hairpin from UvrB proteins from a number of bacteria, showing the conserved nature of the hydrophobic residues.

In this study, we have substituted several hydrophobic residues of the β-hairpin for alanine residues and tested the mutant proteins for activity on damaged and undamaged substrates. The results show that the hydrophobic residues at the base of the β-hairpin have an important function in damage recognition. In particular, we have identified residues that prevent binding of UvrB to non-damaged DNA by clashing with the non-damaged nucleotide. When damage is present, clashing does not occur, strongly suggesting that the damaged nucleotide is flipped out of the DNA helix.

Results

Construction of the hairpin mutants

The crystal structures of the UvrB proteins from B.caldotenax and T.thermophilus (Machius et al., 1999; Nakagawa et al., 1999; Theis et al., 1999) revealed the presence of a β-hairpin with two conserved sets of tandem hydrophobic residues (Escherichia coli positions 92 + 93 and 95 + 96, Figure 1B). In addition, the tip of the hairpin contains two hydrophobic residues (E.coli positions 101 and 108) that are separated by six residues, but which are close together in the three-dimensional structure (Figure 1A). To test whether these tyrosine and phenylalanine residues play a role in the damage-specific binding of UvrB, we have substituted these residues in pairs by alanines, resulting in the mutant proteins UvrBY92+Y93, UvrBY95+Y96 and UvrBY101+F108.

First, the mutant proteins were tested for their in vivo activity in a complementation assay. For this purpose, the mutated genes were inserted into the low copy number plasmid pSC101. Figure 2A shows that strains expressing UvrBY95+Y96 or UvrBY101+F108 are as sensitive to UV as a strain lacking the UvrB protein. The UV sensitivity of mutant UvrBY92+Y93 could not be tested, since, to our surprise, the plasmid expressing this mutant protein did not give viable transformants in CS5017. Transformants could only be obtained in a strain lacking the uvrA gene, but not in the wild-type strain or strains lacking uvrB or uvrC. This lethal phenotype of the mutant protein in the presence of UvrA was observed with both the overproduction plasmid (pBR322 derivative) and the low copy number plasmid (pSC101 derivative), indicating that it is not replication of the plasmid itself that is impaired by the UvrB mutant. Most probably the UvrA protein loads the UvrB mutant onto as yet undefined sites in the DNA and, as a result of the amino acid substitutions in UvrBY92+Y93, the protein remains very stably bound to the DNA, thereby interfering with processes such as transcription and/or replication.

Fig. 2. UV survival of strains harbouring plasmids that express the (mutant) UvrB protein. Small droplets of the different strains were deposited on agar plates, after which they were irradiated with the indicated dose of UV light. (A) The repair activity of the mutant UvrB proteins was determined in a strain lacking the chromosomal uvrB gene (complementation assay). (B) The ability of the mutant UvrB proteins to compete with wild-type UvrB for binding of UvrA was determined in a strain expressing wild-type UvrB from the chromosome (dominance assay).

Expression of UvrBY95+Y96 and UvrBY101+F108 in a wild-type strain shows these mutants to be dominant over the wild-type protein (Figure 2B), indicating that they are at least capable of carrying out the first step in the repair reaction, i.e. the binding of UvrA.

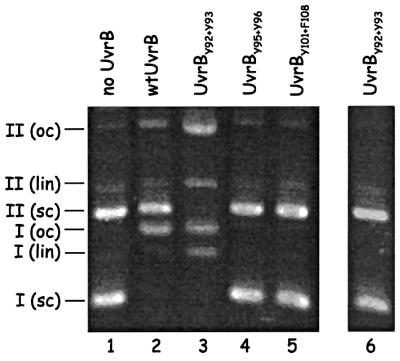

Effect of the UvrB mutants on (damage-dependent) incision by UvrABC

First we assayed the effect of the substitutions on the UvrABC-mediated incision of (UV-irradiated) supercoiled plasmids. Figure 3 shows that in the presence of the wild-type UvrB protein, the UV-irradiated plasmid is incised, resulting in the relaxed form of the plasmid, whereas the non-irradiated control that is present in the same incubation mixture remains intact (lane 2). In the presence of UvrBY95+Y96 or UvrBY101+F108, no incision is obtained (lanes 4 and 5), which is in agreement with their UV-sensitive phenotype in vivo. Strikingly, in the presence of UvrBY92+Y93, not only the UV-irradiated plasmid, but also the non-damaged control plasmid, is incised (lane 3). Incision is very efficient, resulting not only in relaxed, but also in linear DNA, which must be the result of two nearby incisions in opposing strands. In the absence of UvrC, no nicking of supercoiled DNA is observed (lane 6), showing that the observed incisions are not due to a contaminat ing nuclease activity in our UvrBY92+Y93 preparation. Apparently, as a result of the amino acid substitutions, the mutant UvrB protein not only stably binds to non-damaged DNA, as was suggested by the in vivo results, but proficient UvrB–DNA pre-incision complexes are formed, which subsequently can be incised by UvrC.

Fig. 3. Incision of (UV-irradiated) supercoiled DNA in the presence of the (mutant) UvrB proteins. A mixture of supercoiled DNA of UV-irradiated pUC19 (I, 2686 bp) and non-irradiated pNP81 (II, 4362 bp) was incubated with UvrA, UvrC and the indicated UvrB mutant. The positions of the supercoiled (sc), open circle (oc) and linear (lin) forms of the plasmids are indicated. Lanes 1–5 show the results after incubation with (mutant) UvrB, UvrA and UvrC. Lane 6 shows the result after incubation with UvrA and UvrBY92+Y93 in the absence of UvrC.

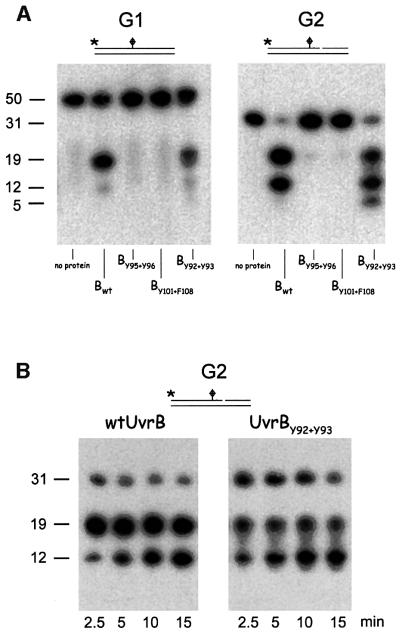

The incision in the presence of the mutant UvrB proteins was also determined on a double-stranded substrate with specific damage (G1) and on a similar substrate that is pre-nicked at the 3′ incision position (G2). Again UvrBY95+Y96 and UvrBY101+F108 appeared to be completely defective for both 3′ and 5′ incisions (Figure 4A). Mutant UvrBY92+Y93, however, did give rise to 3′ and 5′ incisions, albeit that these were somewhat reduced compared with the wild-type protein (Figure 4A). These incisions are not observed when UvrA is omitted from the incubation mixture (not shown). It seems that, despite its stable binding to non-damaged sites, the mutant protein is still capable of recognizing and of specific binding to a damaged site. Strikingly, although the overall incision in the presence of UvrBY92+Y93 is reduced compared with wild type, the additional 5′ incision reaction (resulting in a 12 nucleotide fragment) is more efficient with the mutant. This is especially clear in a kinetic experiment, which shows that already after 5 min, >50% of the 5′ incision product contains the additional incision (Figure 4B). After 30 min, even a second additional incision is made in the presence of the mutant (resulting in a five nucleotide fragment), which does not occur with the wild-type protein (Figure 4A). The additional 5′ incision has been shown to be the result of a damage-independent incision activity of UvrBC on DNA substrates with a single-stranded nick (Moolenaar et al., 1998). This damage-independent incision activity appears to be more efficient with UvrBY92+Y93 than with wild-type UvrB (see also below).

Fig. 4. Incision of the 50 bp fragment containing a cholesterol lesion (G1) and the same substrate that is pre-nicked at the 3′-incision position (G2). The substrate used is indicated above each panel. The 5′ end-labelled DNA substrates were incubated with UvrA, UvrC and the indicated (mutant) UvrB. DNA fragments of 50 and 31 nucleotides correspond to the non-incised substrates G1 and G2, respectively. Fragments of 19 nucleotides correspond to incision at the 5′ site. Fragments of 12 nucleotides are the result of the additional 5′ incision by UvrBC, and the fragment of five nucleotides represents a second additional UvrBC incision event. (A) Incision activity determined after incubation for 30 min. (B) Incision activity determined after the indicated incubation times.

DNA binding of the UvrB mutants

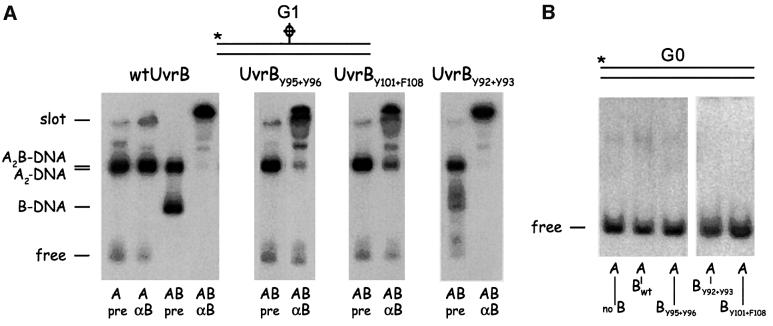

We tested the capacity of the mutant UvrB proteins to bind damaged and non-damaged DNA in a gel retardation assay (with ATP in the gel and running buffer). Incubation of substrate G1 with UvrA and wild-type UvrB results in two retarded bands, the UvrA2B–DNA complex and the UvrB–DNA pre-incision complex, both of which shift to the slot after addition of anti-UvrB antibodies (Figure 5A, panel 1). With mutants UvrBY95+Y96 and UvrBY101+F108, the UvrA2B–DNA complex is still observed, but no UvrB–DNA complexes can be detected (Figure 5A, panels 2 and 3). As expected from the incision results, the UvrBY92+Y93 mutant does result in the UvrB–DNA complex on G1, but the ‘smearing’ in the gel indicates that the mutant complex is somewhat less stable than that of wild-type UvrB (panel 4). Next we tested complex formation on substrate G0, which is the same DNA fragment as G1 but without damage. No complex formation was observed with any of the UvrB proteins. Although UvrA does load UvrBY92+Y93 onto non-damaged sites both in vivo (as shown by the lethality of the mutant in the presence of UvrA) and in vitro (as shown in the incision assay on supercoiled DNA), the UvrB–DNA complexes formed by the mutant apparently are not stable enough to survive a retardation assay. We therefore tested the DNA binding of the (mutant) UvrB proteins in another assay, by measuring the amount of salt sodium citrate (SSC)-resistant protein–DNA complexes retained on a filter using linearized pBR322 as a DNA substrate (Table I). As described previously (Yeung et al., 1986), with UvrA alone, the amount of the resulting complexes on either damaged or non-damaged DNA after challenging with high salt is very low. The (mutant) UvrB proteins on their own did not show any detectable binding. In the presence of UvrA and wild-type UvrB, clearly more complexes are obtained on UV-irradiated DNA than on non-damaged DNA. These complexes must therefore be the result of the loading of the UvrB protein onto the damaged site by UvrA. With mutants UvrBY95+Y96 and UvrBY101+F108, hardly any SSC-resistant complexes are observed, confirming the results of the gel retardation assay that these mutants are severely disturbed in formation of the UvrB–DNA complex. With mutant UvrBY92+Y93, a significant amount of SSC-resistant complexes on non-damaged DNA is obtained, showing that the mutant protein is indeed loaded onto non-damaged sites by UvrA. The amount of the complexes on damaged DNA is even higher, which must be the result of a combination of damage-specific and non-specific binding, confirming that UvrBY92+Y93 is still capable of recognizing DNA lesions.

Fig. 5. Complex formation of substrates G1 and G0 with UvrA and the different UvrB mutants. Substrate G1 is a 50 bp fragment with a cholesterol lesion. Substrate G0 is the same fragment without the lesion. (A) The 5′ end-labelled G1 substrate was incubated with UvrA or UvrAB, after which antibodies against UvrB (αB) or pre-serum (pre) were added when indicated. The position of the different Uvr–DNA complexes is shown. Binding of the UvrB antibody to a UvrB-containing complex retains this complex in the slot. (B) The 5′ end-labelled G0 substrate was incubated with UvrA or UvrAB, after which pre-serum was added.

Table I. Filter binding of salt-resistant complexes on (damaged) DNA.

| Protein | Undamaged DNA | UV-damaged DNA |

|---|---|---|

| UvrA | 1.2 | 3.4 |

| Wild-type UvrB | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| UvrBY95+Y96 | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| UvrBY101+Y108 | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| UvrBY92+Y93 | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| UvrA + wild-type UvrB | 11.3 | 36.7 |

| UvrA + UvrBY95+Y96 | 1.6 | 2.6 |

| UvrA + UvrBY101+Y108 | 1.2 | 2.9 |

| UvrA + UvrBY92+Y93 | 34.0 | 42.0 |

The DNA binding is expressed as a percentage of input DNA retained on the filter by the proteins.

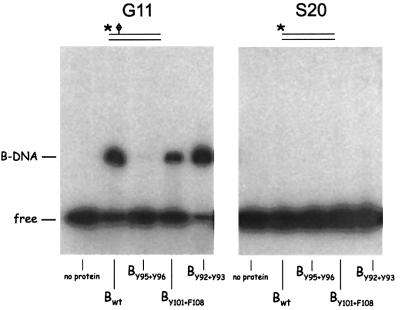

To test whether the mutants UvrBY95+Y96 and UvrBY101+F108 are affected in the UvrA-mediated loading of UvrB onto the damaged site, or in the damage recognition per se, we next analysed the binding of the UvrB proteins to substrate G11. In this 31 bp substrate, the damage is located eight nucleotides from the 5′ end of the fragment and it has been shown that the wild-type UvrB protein no longer needs UvrA to bind to the damaged site, because it can approach the damaged site from the end of the fragment (Moolenaar et al., 2000a; Figure 6). In this binding assay, mutants UvrBY101+F108 and UvrBY95+Y96 behave differently. UvrBY101+F108 binds to G11, albeit with a somewhat lower affinity than the wild-type protein (Figure 6, panel 1), indicating that this mutant protein is still capable of recognizing damage in the DNA. UvrBY101+F108 apparently is disturbed in the UvrA-mediated loading of UvrB onto the damaged site, but it still has its damage-recognizing determinants. With mutant UvrBY95+Y96, no complex is observed, suggesting that one or both of these residues at the base of the hairpin plays an important role in the damage recognition. Finally UvrBY92+Y93 is capable of damage recognition resulting in binding of substrate G11 similar to the wild-type protein. As was found for G0, none of the UvrB proteins shows complex formation on the control substrate S20, which is not damaged.

Fig. 6. Complex formation of the different UvrB mutants with substrates G11 and S20. Substrate G11 is a 31 bp double-stranded DNA fragment with the cholesterol damage located eight nucleotides from the 5′ end. Substrate S20 is the same fragment without the damage. The position of the damage-specific UvrB–DNA complex is shown.

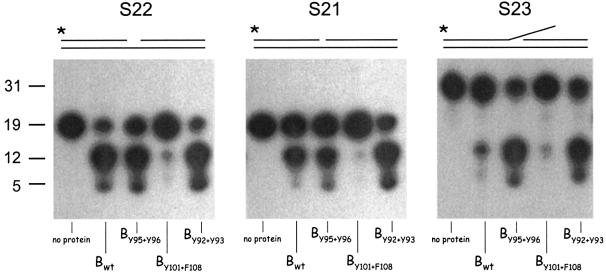

Effect of the UvrB mutants on damage-independent incision by UvrBC

We have shown in the past that UvrB and UvrC are capable of damage-independent incision on DNA substrates carrying a single-stranded nick (Moolenaar et al., 1998). This incision, which is independent of UvrA, takes place at the seventh phosphodiester bond from the 5′ side of the nick, and it is induced by the 5′ catalytic site of UvrC (Moolenaar et al., 1998). The damage-independent incision by UvrBC is responsible for the extra 5′ incision on damaged DNA. Further analysis of the damage-independent incision has revealed a double-stranded DNA fragment with a one nucleotide gap to be the optimal DNA substrate (G.F.Moolenaar and N.Goosen, in preparation). This substrate is also incised at the seventh phosphodiester bond 5′ from the gap. We tested the three UvrB mutants for incision on a 40 bp substrate with a one nucleotide gap (S22). The incisions in the presence of wild-type UvrB, UvrBY92+Y93 and UvrBY95+Y96 are very efficient (Figure 7, panel 1). The fact that UvrBY95+Y96 is defective in the damage-specific incision, but not in incision of the undamaged gapped substrate, again shows that residues Y95 and/or Y96 are particularly important for the damage-specific binding. With mutant UvrBY101+F108, no incision is observed, showing that Y101 and/or Y108 are essential for proficient UvrBC–DNA complex formation on both damaged and gapped DNA.

Fig. 7. Damage-independent incision by the different UvrB mutants. Substrate S22 contains a one nucleotide gap, substrate S21 contains a single-stranded nick, and substrate S23 contains the same one nucleotide gap as S22 but with the 5′ top oligo extended with 12 nucleotides. The substrates used are indicated above each panel. The 5′ end-labelled DNA substrates were incubated with UvrC and the indicated (mutant) UvrB for 30 min. DNA fragments of 19 (S22 and S21) and 31 (S23) nucleotides correspond to the non-incised substrates. Fragments of 12 and five nucleotides correspond to the first and second UvrBC incision event, respectively.

We also analysed the UvrBC incision on two other substrates. Substrate S21 contains a single-stranded nick in the top strand instead of the one nucleotide gap and is comparable to the nicked substrate described previously (Moolenaar et al., 1998). Substrate G23 contains the same one nucleotide gap as substrate S22, but the 5′ top oligo is extended with 12 nucleotides, resulting in a ‘flap’ structure. Figure 7 (panel 2) shows that wild-type UvrBC incises substrate S21 but with a lower efficiency than S22. Again, mutant UvrBY101+F108 is deficient in the UvrBC incision of this substrate, and mutant UvrBY95+Y96 results in a similar amount of incision as the wild-type protein. With mutant UvrBY92+Y93, incision is now even more efficient than with wild-type UvrB, which agrees with the observed enhanced additional 5′ incision on substrate G1 (Figure 4A). The incision obtained in the presence of UvrBY92+Y93 on substrate S21 is comparable with the amount obtained with wild-type UvrB or UvrBY92+Y93 on substrate S22. The difference between S21 and S22 is the presence or absence of one nucleotide in the 3′ top strand. It appears that removal of this nucleotide enhances the formation of an efficient UvrBC–DNA complex with the wild-type proteins, but has no effect on complex formation with UvrBY92+Y93 and UvrC. This strongly suggests that residues Y92 and/or Y93 provide steric hindrance for UvrBC binding to S21 but not to S22, which would mean that in the protein–DNA complex these residues are located very close to the gap of substrate S22 and therefore collide with the nucleotide that fills this gap in S21.

An even more striking effect of the mutant UvrB proteins is observed with the flap substrate S23 (Figure 7, panel 3). The incision of this substrate with wild-type UvrBC is very low, indicating that the protruding 12 nucleotide flap interferes with formation of an efficient complex. Again, mutant UvrBY101+F108 does not show activity on this substrate. Now, however, not only UvrBY92+Y93 but also UvrBY95+Y96 results in a very efficient incision. Apparently, in the wild-type UvrB protein, Y92 and/or Y93 again clash with the nucleotide that ‘fills’ the gap (the first nucleotide of the flap protrusion) but now Y95 and/or Y96 also clash, probably with nucleotides further away in the protrusion.

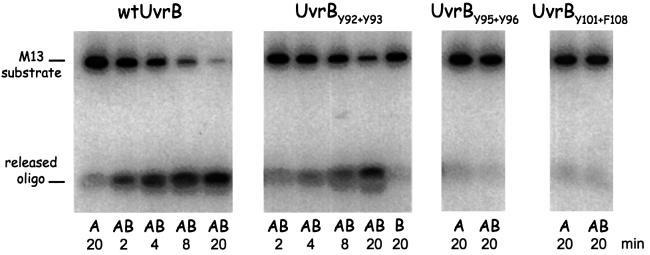

DNA-unwinding and ATPase activity of the UvrB mutants

It has been shown that UvrB together with UvrA possesses a limited DNA-unwinding activity (Oh and Grossman, 1987, 1989; Gordienko and Rupp, 1997). This activity most probably represents a local strand separation by UvrB as part of the UvrA2B complex, which is required to load UvrB onto the damaged site (Moolenaar et al., 1994). We have tested the DNA unwinding activity of the mutant UvrB proteins using a 17 nucleotide oligo annealed to single-stranded M13 DNA as a substrate. Figure 8 (panel 1) shows that with wild-type UvrB, after 4 min, >50% of the oligo is already released. With mutant UvrBY92+Y93, the unwinding activity is also observed but it is reduced compared with wild-type UvrB (panel 2). This partial activity agrees with the partial activity of this mutant in formation of the pre-incision complex and the subsequent incisions. Mutants UvrBY95+Y96 and UvrBY101+F108 do not show any release of the oligo (Figure 8, panels 3 and 4), showing that the inability of these mutants to form UvrA-dependent UvrB–DNA complexes on substrate G1 coincides with their inability to unwind DNA.

Fig. 8. DNA-unwinding activity of the different UvrB mutants. The (mutant) UvrB used is indicated above each panel. The substrate used is a terminally labelled 17 nucleotide oligo annealed to M13 single-stranded DNA. The substrate was incubated with UvrA or UvrAB for the indicated time, after which the reaction was stopped by the addition of SDS. The positions of the substrate and the released oligo are shown.

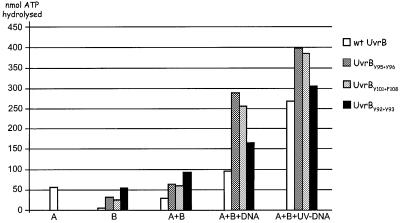

DNA unwinding by the UvrA2B complex requires ATP hydrolysis by the UvrB protein (Seeley and Grossman, 1990). We therefore tested the ATPase activity of the mutant UvrB proteins (Figure 9). As shown previously (Oh et al., 1989), the ATPase activity of UvrB alone or in complex with UvrA is very limited. Addition of DNA to the UvrA2B complex stimulates ATP hydrolysis (Figure 9), and mutational analysis has shown the UvrB protein to be responsible for this (Seeley and Grossman, 1990). In the presence of UV-irradiated DNA, the ATP hydrolysis is enhanced even further (Figure 9; Oh et al., 1989). All three UvrB mutants show ATPase activity in response to the presence of (damaged) DNA (Figure 9). This means that the inability of mutants UvrBY95+Y96 and UvrBY101+F108 to unwind DNA is not caused by a defect in the ‘motor’ of the strand-separating activity. Strikingly, the ATPase activities of all three mutants are enhanced compared with that of wild-type UvrB. The ATP hydrolysis that occurs upon addition of undamaged DNA is expected to be accomplished by UvrA2B complexes that are searching for damage. During this search, UvrA initially will detect a potential irregularity in the DNA and this will trigger the ATPase and the accompanying DNA-unwinding activity of UvrB to probe the DNA for the presence of damage. When no damage is detected, the protein complex will dissociate from the DNA. When damage is detected, the UvrB–DNA pre-incision complex will be formed, which is probably associated with other rounds of ATP hydrolysis (Moolenaar et al., 2000b), resulting in the observed further enhanced ATPase activity in the presence of UV-damaged DNA. With mutants UvrBY95+Y96 and UvrBY101+F108, which are still capable of forming the UvrA2B complex, similarly to wild-type UvrB, the detection of potential damage in the DNA by UvrA will trigger the ATPase activity of UvrB. In contrast to the wild-type protein, however, this ATP hydrolysis does not result in strand separation because the mutant proteins are affected in important DNA interactions. We therefore propose that the enhanced ATPase activity of these mutants results from a futile ‘running’ of the ATP motor, which is now uncoupled from the desired effect on the DNA conformation. On damaged DNA, more of these futile ATP-hydrolysing complexes are expected, since UvrA2B binds more readily to damaged sites and therefore the ATPase activity of the mutants in the presence of UV-damaged DNA is enhanced further.

Fig. 9. ATPase activity of the different UvrB mutants. ATP hydrolysis was measured using UvrA alone (A), (mutant) UvrB alone (B), (mutant) UvrB in the presence of UvrA (A + B), (mutant) UvrB in the presence of UvrA and non-damaged DNA (A + B + DNA) and (mutant) UvrB in the presence of UvrA and UV-irradiated DNA (A + B + UV–DNA). ATPase activity is expressed as nmol ATP hydrolysed per nmol UvrA (or UvrB) per minute.

The enhanced ATP hydrolysis observed in the presence of UvrBY92+Y93 must be explained in a different way. We have shown here that this mutant is capable of forming incisable pre-incision complexes on non-damaged DNA. The observed ATPase activity of UvrBY92+Y93 in the presence of undamaged DNA is therefore a combination of ATP hydrolysis that accompanies the search for damage as described above and the ATP hydrolysis that is associated with pre-incision complex formation, similar to what is observed with wild-type UvrB in the presence of damaged DNA. Besides binding to non-damaged sites, UvrBY92+Y93 is also capable of preferentially binding to a lesion. Therefore, the ATP hydrolysis in the presence of UV-damaged DNA is even higher, since more pre-incision complexes are expected to form on damaged DNA.

Discussion

The broad substrate range of NER, in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes, has raised the intriguing question of how all the different types of damage can be recognized by the same protein(s). Clearly the repair proteins do not bind specifically to the damage itself, but they should be able to recognize a common structural alteration in the DNA helix caused by the damage. In this study, we have identified residues of UvrB that are very important for the discrimination between damaged and non-damaged DNA, allowing us for the first time to propose a model for the process of damage recognition during NER at the molecular level.

Substitution of Y92 and Y93 at the base of the β-hairpin results in a protein that is loaded onto non-damaged DNA by UvrA, resulting in stable UvrB–DNA complexes that can be incised by UvrC. Despite this affinity for non-damaged DNA, mutant UvrBY92+Y93 is still capable of forming efficient UvrB–DNA pre-incision complexes on a damaged site, albeit with a somewhat reduced stability. It would appear that Y92 and Y93 are not essential for the recognition of the damage per se, but the main function of these residues is to prevent the formation of pre-incision complexes on non-damaged sites. How this is achieved becomes clear from our studies on the damage-independent incision by (mutant) UvrBC.

The optimal substrate for the damage-independent UvrBC incision is a double-stranded DNA fragment with a one nucleotide gap (G.F.Moolenaar and N.Goosen, in preparation). A similar substrate with a single-stranded nick is also incised, but to a minor extent. On these substrates, incision is induced at the 5′ side of the gap/nick by the same catalytic site of UvrC that on damaged DNA induces the 5′ incision (Moolenaar et al., 1998). The gapped/nicked DNA is incised seven nucleotides from the gap/nick and 5′ incision on damaged DNA also takes place seven nucleotides from the damaged base (i.e. the eighth phosphodiester bond from the damage). Therefore, the gap should be at the same position in the UvrB–DNA complex where the lesion normally is located. This means that in the nicked DNA, the first nucleotide at the 3′ side of the nick will be at the position of the lesion in the UvrB–DNA complex. Our results show that the presence of this additional nucleotide in the nicked substrate reduces UvrBC incision of wild-type UvrB, but has no effect on incision in the presence of UvrBY92+Y93. This strongly suggests steric hindrance between the nucleotide that occupies the ‘lesion site’ and residues Y92 and/or Y93. Such steric hindrance by Y92 and/or Y93 can also explain the role of these residues in preventing the binding of UvrB to ‘normal’ non-damaged DNA. In the nicked substrate, clashing between the nucleotide and Y92 and/or Y93 is not absolute, since the presence of the nick provides flexibility in the DNA, allowing the nucleotide to move away from the hydrophobic residues. Therefore, UvrB binding and subsequent UvrC incision, albeit reduced, can still occur. In normal double-stranded DNA, there is no such flexibility and the nucleotide will be held in place by stacking with the neighbouring bases. As a result, the presence of this nucleotide and the tyrosine residues is mutually exclusive and no stable UvrB–DNA complex can be formed.

If indeed clashing of a non-damaged nucleotide with Y92 and/or Y93 avoids the binding of UvrB to non-damaged sites, what will happen when this nucleotide is damaged? We propose that the damaged nucleotide will be flipped out of the DNA helix, allowing Y92 and/or Y93 to occupy the vacated space. Such nucleotide flipping might be a crucial feature of the damage recognition process. It has been suggested that the alterations in stacking interactions are the only common denominator of helical deformation by all DNA lesions recognized by UvrB (van Houten and Snowden, 1993). Such alterations in stacking would promote flipping of the lesion in favour of the Y92 and/or Y93 residues occupying its place. In other words, damage recognition would be determined by the ease of flipping a nucleotide out of the DNA helix.

Nucleotide flipping seems to be a common theme in many different DNA repair systems. The co-crystal structures of uracil-DNA glycosylase (Slupphaug et al., 1996), 3-methyladenine-DNA glycosylase (Lau et al., 1998) and 8-oxoguanine-DNA glycosylase (Bruner et al., 2000) showed the damaged nucleotides to be in an extrahelical position. In the complex of endonuclease IV bound to DNA with an abasic (AP) site, not only the AP site, but also the opposing nucleotide is flipped out of the DNA helix (Hosfield et al., 1999). In the different repair complexes, the flipped configuration is stabilized by insertion of one or more amino acids into the DNA helix to occupy the vacated space. For all of these repair enzymes, the purpose of nucleotide flipping is to present the damaged base (or AP site) to the protein, where it fits nicely into a binding pocket of the enzyme. For UvrB, this is not expected. Damage recognized by UvrB can sometimes be very bulky adducts (like the cholesterol used in this study) and it is therefore more likely that the damaged nucleotide will be rotated away from the protein, thereby preventing an adduct from forming a steric hindrance.

Our proposed flipping mechanism also explains an early observation that UvrB and photolyase can bind simultaneously to a pyrimidine dimer (Sancar et al., 1984). The binding of photolyase was even shown to stimulate incision of UV-damaged DNA by UvrABC. From the structure of photolyase, it was predicted that upon binding to its DNA substrate, the cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer (CPD) will flip out of the DNA helix and enter the cavity of the enzyme that contains the catalytic cofactor (Vande Berg and Sancar, 1998). Flipping of the dimer away from the UvrB protein will present this photoproduct to the binding pocket of photolyase and, vice versa, the binding of photolyase will stabilize the extrahelical conformation of the CPD, thereby stimulating the UvrABC repair.

Substitution of the two other tyrosine residues at the base of the β-hairpin, Y95 and Y96, completely abolishes the damage-specific binding of UvrB, but the damage-independent incision of the nicked and gapped DNA fragments is not affected. This strongly suggests a direct role for Y95 and/or Y96 in damage-specific binding. It is possible that these residues play an important role in stabilizing the proposed flipped structure. How this is achieved at a molecular level cannot be concluded from the results presented here, but the activity of UvrBY95+Y96 on the flap substrate S23 might give a clue as to where Y95 and/or Y96 might be situated in the complex with respect to the lesion. The UvrBC incision of substrate S23 with wild-type UvrB is very low, indicating that the protruding flap somehow interferes with the UvrB binding. With mutant UvrBY95+Y96, incision is significantly increased, indicating that in the absence of Y95 and Y96 the flap no longer interferes with DNA binding. On substrate S21 with the single-stranded nick, there is no difference between the incisions with wild-type UvrB or UvrBY95+Y96, indicating that the nucleotide that occupies the ‘lesion site’ in the complex with S21 does clash with Y92 and/or Y93 as stated above, but not with Y95 or Y96. Therefore, Y95 and/or Y96 are expected to collide with nucleotide(s) further away in the flap. Extrapolating this to the complex formed on damaged DNA, the Y95 and/or Y96 residues should be positioned at the 3′ side of the lesion.

The two hydrophobic residues in the tip of the β-hairpin are not directly involved in damage-specific binding, since substitution of Y101 and F108 does not prevent binding of UvrB to substrate G11. On a normal damaged substrate (G1), however, the UvrB–DNA complex is no longer formed. This is most likely to be related to the complete defect in DNA unwinding by this mutant, despite the activity of the ATPase ‘motor’. Since the DNA-unwinding activity of the (wild-type) UvrA2B complex can be detected on a non-damaged substrate, it most probably represents the strand-separating activity by UvrB in search of damage. We propose that the hydrophobic residues in the tip of the hairpin are important for initial disruption of the double-stranded DNA, probably via stacking between the bases. This initial unwinding will allow the hairpin to insert between the DNA strands, as proposed by Theis et al. (1999), after which further contacts between the DNA and residues elsewhere in the protein will lead to further strand separation. Mutation of Y101 and F108 will block this first step of insertion of the hairpin, explaining why the DNA unwinding by this mutant is completely abolished. For the binding of substrate G11, unwinding is not required because ‘breathing’ of the DNA ends allows the hairpin to be inserted from the end of the fragment. This explains why UvrBY101+F108 does bind to G11 efficiently. In agreement with this, we have shown in the past that a ‘true’ helicase mutant, which is disturbed in both ATPase and DNA-unwinding activities, also binds G11 efficiently (Moolenaar et al., 2000a).

Mutant UvrBY95+Y96 is also completely defective in DNA-unwinding activity. Our proposed model for damage recognition via flipping implies that during the search for lesions, nucleotides will be probed for the presence of damage by flipping them out of the helix. Such probing by flipping of the nucleotides most probably constitutes an important part of the DNA-unwinding activity of UvrB, explaining the defect of UvrBY95+Y96 in our DNA-unwinding assay.

In summary, we arrive at the following model for damage-specific binding by UvrB. Initially, UvrA, as part of the UvrA2B complex, probes the DNA for the presence of irregularities via an as yet unknown mechanism. When such an irregularity is detected, the ATPase activity of UvrB is activated to promote strand opening by the UvrB protein. This strand opening is facilitated by the wrapping of DNA around the UvrB protein and probably also by the damage itself, which in most cases destabilizes the helix structure. Initially, the hydrophobic residues in the tip of the hairpin will disrupt the base pairing. Interaction of the DNA strands with other parts of the protein, coupled to ATPase-induced domain movement, will assist the strand opening further, allowing the hairpin to insert between the two DNA strands. Next, the hydrophobic residues at the base of the hairpin will probe the nucleotides for impaired stacking interactions by flipping them out of the helix. Residues Y95 and Y96 seem to have a more or less direct role in this nucleotide flipping. When no damage is detected, the flipped configuration is unstable, mainly because stacking of the neighbouring bases tends to hold the non-damaged nucleotide in place. This nucleotide subsequently clashes with residues Y92 and/or Y93 and UvrB will dissociate from the DNA. When damage is detected, the flipped configuration is maintained and the subsequent steps of the repair reaction can be initiated.

Mammalian NER shares a property with bacterial repair in that it recognizes a large variety of lesions. Also, as in bacterial repair, damage-specific binding is a multistep process, involving multiple damage-recognizing factors, among which are XPA, XPC-HR23B and TFIIH (Batty and Wood, 2000). Although it is still a matter of debate as to which protein is the ultimate damage-recognizing protein, we predict that it will probe the DNA for the presence of damage in a similar way, i.e. by flipping nucleotides out of the helix thereby testing for alteration in base stacking with the neighbouring nucleotides.

Materials and methods

Construction of the UvrB mutants

UvrBY95+Y96, UvrBY101+F108 and UvrBY92+Y93 contain alanine substitutions of the indicated hydrophobic residues (Figure 1). All UvrB mutants were constructed by PCR in the following way. One PCR was performed using oligo B1 hybridizing upstream of the unique NcoI site of the uvrB gene and an oligo carrying the desired mutation. A second PCR was performed with the complementary oligo carrying the same mutation and oligo B2 hybridizing downstream of the unique BclI site. Next the two PCR fragments were combined and used in a third PCR with oligos B1 and B2. The resulting fragment was restricted with NcoI and BclI and subsequently used to substitute the NcoI–BclI fragment of the UvrB-overproducing plasmid pNP83 (Moolenaar et al., 1994). All mutant plasmids finally were verified by sequencing for the absence of additional PCR-induced mutations.

For in vivo studies of the UvrB mutants, the mutated uvrB genes were inserted into the low copy number plasmid pNP121 (Moolenaar et al., 2000c), which is a pSC101 derivative expressing the uvrB gene from its own promoter. The transfer of the mutations was achieved by exchanging the BglII–NcoI fragment.

UV sensitivity assay

The pSC101 derivatives expressing the mutant UvrB proteins were introduced into CS 5017 (ΔuvrB; Moolenaar et al., 1994) or the isogenic wild-type strain GM1 (Coulondre and Miller, 1977). Transformants were grown to an OD600 of 0.3. Next the culture was diluted 10 times and spots of 2 µl were deposited on agar plates, which were irradiated with the indicated doses of UV light. The plates subsequently were incubated overnight at 30°C.

Protein purifications

The UvrA, UvrB and UvrC proteins were purified as described (Visse et al., 1992). The mutant UvrB proteins were purified from a ΔuvrA, ΔuvrB background (CS 5018; Moolenaar et al., 1994). Cells were harvested from a 1 l culture, 2 h after induction of UvrB expression by isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). The cells were resuspended in 6 ml of sucrose solution (40 mM Tris pH 8.0, 10 mM EDTA, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 2.4 M sucrose), after which 12 ml of buffer B (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 20% glycerol) containing 25 mM KCl and 125 µg/ml lysozyme were added. The mixture was kept on ice for 20 min and the lysate was spun down for 25 min in 60 Ti tubes at 37 000 r.p.m. The supernatant was loaded on a hydroxyapatite column, which was equilibrated with buffer H1 (10 mM KPO4 pH 6.8, 1 mM EDTA, 20% glycerol, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol) and the protein was eluted with buffer H2 (200 mM KPO4 pH 6.8, 1 mM EDTA, 20% glycerol, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol). The UvrB-containing fractions were loaded on a blue Sepharose column in buffer B containing 25 mM KCl. Subsequently, the proteins were eluted in buffer B using a gradient from 25 mM to 1 M KCl. Finally, the UvrB-containing fractions were dialysed in buffer Q [20 mM imadazole pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol] with 100 mM KCl. After loading on a mono-Q column (Amersham-Pharmacia), the proteins were eluted in buffer Q using a gradient from 100 to 500 mM KCl. The UvrB-containing fractions that were >99% pure were used for in vitro analysis.

DNA substrates

The 50 bp DNA substrate G1 contains a cholesterol lesion at position 27 of the top strand. Substrate G2 is similar to G1, but with a nick at the 3′ incision position (between positions 31 and 32). Substrate G11 is a 31 bp DNA fragment containing the cholesterol lesion at position 8 of the top strand. These damage-containing substrates were constructed as described (Moolenaar et al., 2000a). Substrates G0 and S20 are the same as G1 and G11, respectively, but without the damage. Substrate S21 is a 40 bp DNA fragment with a nick between positions 19 and 20 of the top strand and was constructed by hybridization of the bottom strand 5′-CGTTCTGAGTTCCAGTAGTAATGTGGCCGTAAGTAATCCC-3′ with the 5′ top oligo 5′-GGGATTACTTACGGCCACA-3′ and the 3′ top oligo 5′-TTACTACTGGAACTCAGAACG-3′. Substrate S22 contains a one nucleotide gap at position 20 of the top strand and was constructed similarly to S21 but replacing the 3′ top oligo with 5′-TACTAC TGGAACTCAGAACG-3′. The flap substrate S23 is similar to substrate S22, but with the 5′ top strand elongated with 12 nucleotides (GGGATT ACTTACGGCCACACCTTCTTCCCTG-3′).

Incision assays

Supercoiled DNA of pUC19 (100 ng/µl) was irradiated with 450 J/m2 and was combined with an equal amount of non-irradiated pNP81 supercoiled DNA. The plasmids were incubated in 10 µl of Uvr-endo buffer [50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 100 mM KCl, 0.1 µg/µl bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 1 mM ATP] containing 50 nM UvrA, 100 nM UvrB and 100 nM UvrC. The reaction was incubated for 30 min, after which the reaction was terminated by addition of 3 µl of gel loading buffer (15% Ficoll, 0.25% bromophenol blue, 0.25% xylene cyanol) containing 3% SDS. The samples were run on a 0.7% agarose gel in Tris–borate and the DNA was visualized with ethidium bromide.

The linear DNA substrates were 5′ terminally labelled in the top strand using T4 polynucleotide kinase. The damaged DNA substrates G1 and G2 (2–4 fmol) were incubated with 100 nM UvrB, 50 nM UvrC and 2.5 nM UvrA in 20 µl of Uvr-endo buffer (Moolenaar et al., 2000a). After the indicated times, the reaction was stopped by adding 2 µl of 2 µg/ml glycogen followed by ethanol precipitation. The incision products were visualized on a 15% acrylamide gel containing 7 M urea as described (Moolenaar et al., 2000a). Substrates S21, S22 and S23 (2–4 fmol) were incubated with 100 nM UvrB and 50 nM UvrC in 20 µl of Uvr-endo buffer. After the indicated times, the reaction was stopped and the samples treated as described above.

Filter binding assay

DNA of pBR322 was linearized with ClaI and the ends were labelled using Klenow fragment. The DNA was irradiated with UV light (600 J/m2) when indicated. A mixture of 8.3 nM UvrA, 16.6 nM UvrB and 0.3 nM DNA was incubated for 20 min at 37°C in 60 µl of 50 mM MOPS pH 7.6, 85 mM KCl, 10 mM MgSO4, 1 mM EDTA. Nucleoprotein complexes were diluted in 3 ml of ice-cold 2× SSC and passed through a nitrocellulose filter (Millipore 0.45 µm HA). The filters were counted and the amount of protein–DNA complexes was calculated as the percentage of input DNA retained on the filter by the proteins.

Gel retardation assay

The terminally labelled DNA substrates (2 fmol) were incubated with 100 nM UvrB, with or without 2.5 nM UvrA and/or 50 nM UvrC in Uvr-endo buffer. The mixture was incubated at 37°C as described (Visse et al., 1992); subsequently, 1 µl of antiserum was added where indicated. Analysis of the protein–DNA complexes in the absence of ATP was carried out by loading the samples on a 3.5% native polyacrylamide gel in 0.5× Tris–borate/EDTA. For analysis of the complexes in the presence of ATP, 1 mM ATP and 10 mM MgCl2 were included in the gel and in the running buffer as described (Visse et al., 1992). The gels were run at 4°C at 9 mA for gels without ATP and at 15 mA for gels with ATP, and the protein–DNA complexes were visualized using autoradiography.

ATPase and DNA helicase assays

The ATPase assay was performed as described (Moolenaar et al., 1994). The supercoiled DNA used in this assay was 3.4 nM pWU5 (3450 bp), irradiated with 1000 J/m2 when indicated.

The substrate used for the helicase assay was a 32P-labelled 17mer (GTTTTCCCAGTCACGAC) annealed to M13mp18 single-stranded DNA. The assay was performed as described (Moolenaar et al., 1994).

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Marko Potman for technical assistance. This work was supported by the J.A.Cohen Institute for Radiopathology and Radiation protection (IRS) and an EC grant on Quality of Life and Management of Living Resources (QLG1-CT-1999-00008).

References

- Batty D.P. and Wood,R.D. (2000) Damage recognition in nucleotide excision repair of DNA. Gene, 241, 193–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruner S.D., Norman,D.P. and Verdine,G.L. (2000) Structural basis for recognition and repair of the endogenous mutagen 8-oxoguanine in DNA. Nature, 403, 859–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulondre P.R. and Miller,J.H. (1977) Mutagenic specificity in the lacI gene of Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol., 117, 577–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordienko I. and Rupp,W.D. (1997) The limited strand-separating activity of the UvrAB protein complex and its role in the recognition of DNA damage. EMBO J., 16, 889–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosfield D.J., Guan,Y., Haas,B.J., Cunningham,R.P. and Tainer,J.A. (1999) Structure of the DNA repair enzyme endonuclease IV and its complex: double-nucleotide flipping at abasic sites and three-metal-ion catalysis. Cell, 98, 397–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.L., Morgenstern,K.A., Griffith,J.P., Dwyer,M.D., Thomson,M.A., Murcko,M.A., Lin,C. and Caron,P.R. (1998) Hepatitis C virus NS3 RNA helicase domain with a bound oligonucleotide: the crystal structure provides insights into the mode of unwinding. Structure, 6, 89–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korolev S., Hsieh,J., Gauss,G.H., Lohmann,T.M. and Waksman,G. (1997) Major domain swiveling revealed by the crystal structures of complexes of E.coli Rep helicase bound to single-stranded DNA and ADP. Cell, 90, 635–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau A.Y., Scharer,O.D., Samson,L., Verdine,G.L. and Ellenberger,T. (1998) Crystal structure of a human alkylbase-DNA repair enzyme complexed to DNA: mechanisms for nucleotide flipping and base excision. Cell, 95, 249–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J.-J. and Sancar,A. (1992) Active site of (A)BC excinuclease. I. Evidence for 5′ incision by UvrC through a catalytic site involving Asp399, Asp438, Asp466 and His538 residues. J. Biol. Chem., 267, 17688–17692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machius M., Henry,L., Palnitkar,M. and Deisenhofer,J. (1999) Crystal structure of the DNA nucleotide excision repair enzyme UvrB from Thermus thermophilus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 11717–11722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur S.J. and Grossman,L. (1991) Dimerization of Escherichia coli UvrA and its binding to undamaged and ultraviolet-light damaged DNA. Biochemistry, 30, 4432–4443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moolenaar G.F., Visse,R., Ortiz-Buysse,M., Goosen,N. and van de Putte,P. (1994) Helicase motifs V and VI of the Escherichia coli UvrB protein of the UvrABC endonuclease are essential for the formation of the preincision complex. J. Mol. Biol., 240, 294–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moolenaar G.F., Bazuine,M., van Knippenberg,I.C., Visse,R. and Goosen,N. (1998) Characterisation of the Escherichia coli damage-independent UvrBC endonuclease activity. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 34896–34903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moolenaar G.F., Monaco,V., van der Marel,G.A., van Boom,J.H., Visse,R. and Goosen,N. (2000a) The effect of the DNA flanking the lesion on formation of the UvrB–DNA preincision complex. Mechanism for the UvrA-mediated loading of UvrB onto the damage. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 8038–8043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moolenaar G.F., Herron,M.F., Monaco,V., Van der Marel,G.A., van Boom,J.H., Visse,R. and Goosen,N. (2000b) The role of ATP binding and hydrolysis by UvrB during nucleotide excision repair. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 8044–8050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moolenaar G.F., Moorman,C. and Goosen,N. (2000c) Role of the Escherichia coli nucleotide excision repair proteins in DNA replication. J. Bacteriol., 182, 5706–5714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa N., Sugahara,M., Masui,R., Kato,R., Fukuyama,K. and Kuramitsu,S. (1999) Crystal structure of Thermus thermophilus HB8 UvrB protein, a key enzyme of nucleotide excision repair. J. Biochem., 126, 986–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh E.Y. and Grossman,L. (1987) Helicase properties of the Escherichia coli UvrAB protein complex. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 84, 3638–3642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh E.Y. and Grossman,L. (1989) Characterization of the helicase activity of the Escherichia coli UvrAB protein complex. J. Biol. Chem., 264, 1336–1343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh E.Y., Claassen,L., Thiagalingam,S., Mazur,S. and Grossman,L. (1989) ATPase activity of the UvrA and UvrB protein complexes of the Escherichia coli UvrABC endonuclease. Nucleic Acids Res., 17, 4145–4159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orren D.K. and Sancar,A. (1989) The (A)BC excinuclease of Escherichia coli has only the UvrB and UvrC subunits in the incision complex. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 86, 5237–5241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancar A., Franklin,K.A. and Sancar,G.B. (1984) Escherichia coli DNA photolyase stimulates UvrABC excision nuclease in vitro. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 81, 7397–7401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeberg E. and Steinum,A. (1982) Purification and properties of the UvrA protein from Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 79, 988–992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeley T.W. and Grossman,L. (1990) The role of Escherichia coli UvrB in nucleotide excision repair. J. Biol. Chem., 265, 7158–7165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slupphaug G., Mol,C.D., Kavli,B., Arvai,A.S., Krokan,H.E. and Tainer,J.A. (1996) A nucleotide-flipping mechanism from the structure of human uracil-glycosylase bound to DNA. Nature, 384, 87–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theis K., Chen,P.J., Skorvaga,M., Van Houten,B. and Kisker,C. (1999) Crystal structure of UvrB, a helicase adapted for nucleotide excision repair. EMBO J., 18, 6899–6907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiagalingam S. and Grossman,L. (1991) Both ATPase sites of Escherichia coli UvrA have functional roles in nucleotide excision repair. J. Biol. Chem., 266, 11395–11403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vande Berg B.J. and Sancar,G.B. (1998) Evidence for dinucleotide flipping by DNA photolyase. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 20276–20284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Houten B. and Snowden,A. (1993) Mechanism of action of the Escherichia coli UvrABC nuclease: clues to the damage recognition problem. BioEssays, 15, 51–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velankar S.S., Soultanas,P., Dillingham,M.S., Subramanya,H.S. and Wigley,D.B. (1999) Crystal structures of complexes of PcrA DNA helicase with a DNA substrate indicate an inchworm mechanism. Cell, 97, 75–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeven E.E.A., Wyman,C., Moolenaar,G.F., Hoeijmakers,J.H.J. and Goosen,N. (2001) Architecture of nucleotide excision repair complexes: DNA is wrapped by UvrB before and after damage recognition. EMBO J., 20, 601–611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visse R., de Ruijter,M., Moolenaar,G.F. and van de Putte,P. (1992) Analysis of UvrABC endonuclease reaction intermediates on cisplatin-damaged DNA using mobility shift gel electrophoresis. J. Biol. Chem., 267, 6736–6742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung A.T., Mattes,W.B. and Grossman,L. (1986) Protein complexes formed during the incision reaction catalyzed by the Escherichia coli UvrABC endonuclease. Nucleic Acids Res., 14, 2567–2582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]