Abstract

We have examined the exposure and conservation of antigenic epitopes on the surface envelope glycoproteins (gp120 and gp41) of 26 intact, native, primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) group M virions of clades A to H. For this, 47 monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) derived from HIV-1-infected patients were used which were directed at epitopes of gp120 (specifically V2, C2, V3, the CD4-binding domain [CD4bd], and C5) and epitopes of gp41 (clusters I and II). Of the five regions within gp120 examined, MAbs bound best to epitopes in the V3 and C5 regions. Only moderate to weak binding was observed by most MAbs to epitopes in the V2, C2, and CD4bd regions. Two anti-gp41 cluster I MAbs targeted to a region near the tip of the hydrophilic immunodominant domain bound strongly to >90% of isolates tested. On the other hand, binding of anti-gp41 cluster II MAbs was poor to moderate at best. Binding was dependent on conformational as well as linear structures on the envelope proteins of the virions. Further studies of neutralization demonstrated that MAbs that bound to virions did not always neutralize but all MAbs that neutralized bound to the homologous virus. This study demonstrates that epitopes in the V3 and C5 regions of gp120 and in the cluster I region of gp41 are well exposed on the surface of intact, native, primary HIV-1 isolates and that cross-reactive epitopes in these regions are shared by many viruses from clades A to H. However, only a limited number of MAbs to these epitopes on the surface of HIV-1 isolates can neutralize primary isolates.

The genomic composition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) is characterized by extensive genetic variability that divides this virus into three groups: M (major), O (outlier), and N (non-M, non-O) (22, 26, 27, 33, 34, 37, 44, 54, 58, 64). Based on the sequence of the envelope glycoproteins (gp120 and gp41), 11 genetic subtypes (A to K) have been identified in group M, whereas subtypes within group O remain unidentified (22, 26, 27, 33, 44, 64). The group M subtypes have average nucleotide distances of about 30% to a common ancestral node (43, 44). Viruses belonging to group M have been identified throughout the world, with certain subtypes predominating in different geographic areas (37). Group O is relatively restricted to West Central Africa, while group N was only recently identified, and only a few patient sera have been found to react with its V3 peptides (27, 58).

The envelope glycoproteins of HIV-1 are synthesized as a gp160 polypeptide precursor molecule which is cleaved by cellular proteases to produce two noncovalently associated subunits, gp120 and gp41 (10); these are thought to form heterotrimers in the envelope of the virion. Studies of sequences and biologic properties, as well as crystallographic and immunochemical data, have revealed information on the atomic structure and function of HIV-1 gp120 and gp41. The core of a truncated form of gp120 is composed of two domains (70): the inner domain faces the trimer axis and, presumably, gp41, whereas the outer domain is mostly exposed on the surface of the trimer (70). The whole gp120 subunit is composed of five constant regions (C1 to C5) interspersed by five variable regions (V1 to V5) (60). These constant and variable regions are heavily glycosylated, containing the receptor binding domain used for virus attachment to cells and determinants for cell tropism. Studies have shown that the variable regions of HIV-1 are constrained by disulfide bonds and, as a result, form loop-like structures which may be better exposed than other envelope regions (35, 39, 71). The envelope glycoprotein gp120 is noncovalently associated with gp41, and models of the envelope trimer suggest that gp41 is covered by gp120 (34, 68, 70). The N-terminal fusion domain of gp41 is thought to be released only after gp120 has undergone a conformational change resulting from its interaction with CD4 and one of the coreceptors (8, 28, 56, 66).

Upon infection of a host by HIV, the host immune system produces antibodies that recognize structures on both of the viral envelope glycoproteins. In several studies, these antibodies react with epitopes in the constant and variable regions of gp120 and in several regions of gp41 (14, 16, 17, 19–21). These antibodies have been used in several independent studies to examine the antigenic cross-reactivity of HIV-1 by studying the reactivity patterns of monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) and sera with peptides, monomeric gp120, gp160, oligomeric forms of the envelope, and infected cells (15, 17, 25, 38, 40, 47, 74). In additional studies, HIV-positive sera and MAbs directed at gp120 epitopes in the V3 and CD4bd or at gp41 epitopes in cluster II have been shown to neutralize HIV-1 isolates of different clades (6, 9, 13, 23, 32, 41, 46, 63), but there is no correlation of the neutralization patterns of these reagents with binding to soluble or recombinant viral proteins (17, 30, 38, 47). Moreover, there are no published studies of the epitopes available on the surface of intact, native virus particles, and there are no data with which to study the relationship between the ability of antibodies to bind to virions and to neutralize those virions.

Studies that examine the exposure of antigenic structures on intact, native, primary HIV-1 virions should contribute to efforts to develop a broadly potent vaccine against HIV by identifying shared antigenic structures that also induce antibodies capable of neutralizing diverse HIV strains. Antibodies that are produced by infected humans provide the best tools to explore the antigenic landscape of HIV that is recognized by the human immune system. In our previous study (45), we developed a new strategy for studying the exposure of epitopes on the envelope of intact HIV-1 virions. However, that work used a limited number of HIV-1 isolates and MAbs, and the ability of any given MAb to bind to a virus and neutralize it was not studied. In the present study, we have examined the exposure and conservation of antigenic epitopes on the surface of 26 intact, native HIV-1 group M isolates of clades A to H obtained globally, using 47 MAbs derived from HIV-1-infected patients. We also examined the ability of MAbs to bind to and neutralize intact, native virions. Of the five regions within gp120 and the two regions within gp41 examined, MAbs bound most strongly to epitopes in the V3 and C5 regions of gp120 and to the gp41 cluster I region. The ability of MAbs to bind to a virus did not always correlate with neutralizing ability; however, neutralization of an isolate by a MAb always correlated with its ability to bind to that particular virus isolate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses and virus stock preparation.

A total of 26 HIV-1 group M isolates of clades A to H were studied. The viruses used and the clade to which each belongs are shown in Fig. 1 (see below). The HIV-1 isolates were obtained from patients in Cameroon (CA1, CA4, CA5, CA13, and CA20), Belgium (VI191), Uganda (92UG021 and 92UG001), France (BX08), the United States (MNp, IIIB, and JR-FL), Senegal (SG2728), Zimbabwe (2036), Rwanda (92RW021), Zambia (ZB18), Ivory Coast (CI13), Zaire (MAL), Brazil (93BR019 and 93BR029), Thailand (92TH009, 92TH011, BK131, and CM235), and Gabon (VI525 and VI526). All the viruses have been passaged only in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) except for MAL and IIIB, which had, in the past, been passaged in a continuous cell line (H9 cells) before being carried in human PBMCs. To prepare virus stocks, 1 ml of p24-positive culture supernatants were used to infect 3-day phytohemagglutinin-stimulated HIV-negative donor PBMCs as previously described (47, 48). After 2 to 3 weeks of culture, the culture supernatant from infected PBMCs was aliquoted (1 ml/tube) and stored in liquid nitrogen until use. The p24 concentration in each virus stock was quantitated using our noncommercial p24 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (45).

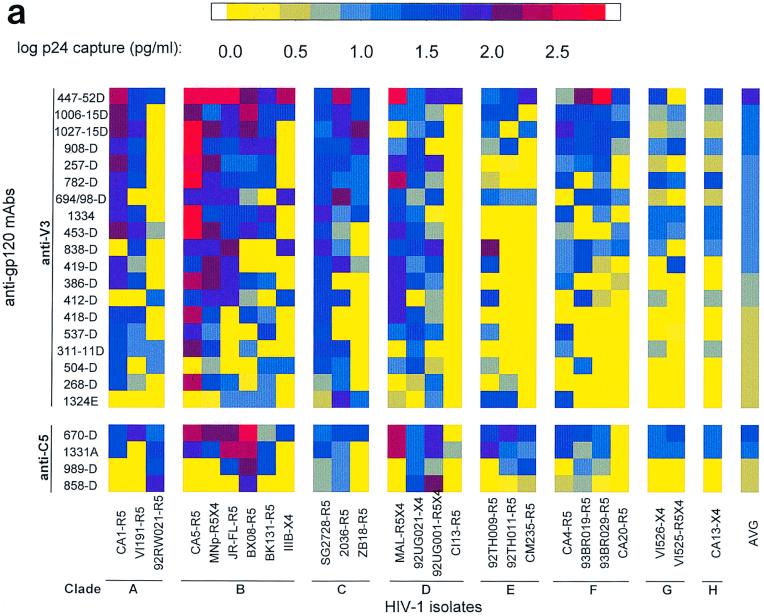

FIG. 1.

Binding patterns of anti-gp120 and anti-gp41 MAbs to intact, native HIV-1 primary group M isolates of clades A to H. (a) Binding of anti-V3 and anti-C5 MAbs; (b) binding of anti-CD4bd, anti-C2, and anti-V2 MAbs; (c) binding of anti-gp41 cluster I and II MAbs. The capacity of a MAb to bind to each virus was measured by assaying the amount of p24 (in picograms per milliliter) released from bound virus after lysis by using a noncommercial p24 ELISA. The p24 levels detected are represented as the log of the amount of p24. For clarity, these logarithmic values are color coded. Color ranges between 0.0 and 1.04 log units (yellow to gray) correspond to lack of binding. Color ranges higher than 1.04 log units (blue to dark blue to red) correspond to weak to strong binding. The isolates represented on the x axis are grouped according to their clades, A to H. The identity of the isolate is followed by its coreceptor usage. For example, isolate CA1 uses coreceptor R5 (CA1-R5). MAbs within each category are shown on the y axis in decreasing order of their average binding to the 26 isolates. The right-hand column in each matrix shows the color-coded value for the average binding of each MAb.

Human anti-HIV MAbs.

A total of 45 human anti-HIV-1 MAbs against various regions of gp120 (V2, C2, V3, CD4bd, and C5) and gp41 (clusters I and II), produced in our laboratory (9, 14–16, 19, 29, 72), were used. Table 1 lists these MAbs along with the epitopes for which each is specific. These MAbs were derived from the PBMCs of HIV-1 clade B-infected patients (and in one case, clade E [MAb 1342E]) as previously described (14–16). Briefly, patients PBMCs were transformed with Epstein-Barr virus and those that were positive for the production of the desired antibodies were expanded and then fused with the SHM-D33 human X mouse heteromyeloma. The resulting heterohybridomas were rescreened for the production of the desired antibody, and the positive cultures were sequentially cloned at limiting cell concentrations until monoclonality was achieved.

TABLE 1.

Human MAbs tested against HIV-1 virions

| MAb | Core epitope | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-gp120 | ||

| Anti-V3 loop | ||

| 257-D | KRIHI | 20 |

| 268-D | HIGPGR | 20 |

| 311-11D | KRIHIGP | 20 |

| 386-D | HIGPGR | 20 |

| 412-Da | RKRIHIGPGRAFYTT | 20 |

| 418-D | HIGPGRA | 20 |

| 419-D | KRIHIGP | 20 |

| 447-52D | GPGR | 20 |

| 453-D | IHIGPGR | 20 |

| 504-D | IHIGPGR | 20 |

| 537-D | IGPGR | 20 |

| 694/98-D | GRAF | 20 |

| 782-D | KSITKG | 17 |

| 838-D | KSITK | 17 |

| 908-D | KSITKG | 17 |

| 1006-15D | KSITKG | 17 |

| 1027-15D | KSITKGP | 17 |

| 1324E | TRTSVR | 15 |

| 1334D | NTb | 73 |

| Anti-CD4 binding domain | ||

| 448-D | Discontinuous | 30 |

| 559/64-D | Discontinuous | 30 |

| 588-D | Discontinuous | 30 |

| 654-D | Discontinuous | 31 |

| 1202-D | Discontinuous | 45 |

| IgG1b12c | Discontinuous | 6 |

| Anti-C2d | ||

| 847-D | aa 241–260 | |

| 1006-30D | aa 241–260 | |

| Anti-C5e | ||

| 670-D | PTKAKRR (aa 503–509)f | 74 |

| 858-D | aa 495–516 | 74 |

| 989-D | aa 495–516 | 74 |

| 1331A | aa 495–516 | 2 |

| Anti-V2 | ||

| 697-D | Discontinuous | 16 |

| 1357 | NT | 45 |

| 1361 | NT | 45 |

| 1393A | NT | |

| 830A | NT | |

| Anti-gp41 | ||

| Cluster I | ||

| 50-69 | Conformational (aa 579–613) | 14 |

| 181-D | LLGIW (aa 592–596) | 72 |

| 240-D | IWG (aa 595–597) | 72 |

| 246-D | LLGI (aa 592–595) | 72 |

| 1367 | Conformational (aa NT) | 45 |

| Cluster II | ||

| 2F5c | ELDKWA (aa 662–667) | 42 |

| 98-6 | Conformational (aa 644–663) | 14 |

| 126-6 | Conformational (aa 644–663) | 72 |

| 167-D | Conformational (aa 644–663) | 72 |

| 1281 | Conformational (aa NT) | 23 |

| 1342 | Conformational (aa NT) | 18 |

Reactive only with 15-mer peptide of HIV-1MN.

NT, not tested.

Recombinant MAb.

The epitopes of anti-C2 are based on reactivity to a region within aa 241 to 260 (KGSCKNVSTVQCTHGIRPVV) from gp120 of HIV-1MN.

The C5 epitope is based on reactivity to aa 495 to 516 (KIEPLGVAPTKAKRRVVQREKR) from gp120 of HIV-1BRU.

Epitope localized to aa 503 to 509 based on reactivity with three overlapping C5 peptides of HIV-1BRU.

Recombinant human MAb IgG1b12 (anti-CD4bd) was provided by D. Burton and P. Parren (6). Recombinant MAb 2F5 to gp41 cluster II (42) was obtained from the Medical Research Council Reagent Program. These MAbs have been extensively described elsewhere (6, 32, 42). Human MAb 860-55D to parvovirus B19 (12) was used as a negative control.

Virus binding assay.

We have previously described a virus binding assay for the detection of epitopes exposed on the surface of intact, native HIV-1 primary isolates (45). Briefly, ELISA wells were coated at 4°C overnight with 100 μl of MAb at 10 μg/ml. After the wells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and blocked with 0.2 ml of 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS (BSA-PBS), virus was added (100 μl/well at 100 ng of p24/ml). After incubation at 37°C for 1 h, the wells were washed with RPMI 1640 to remove unbound virus, the bound virus was lysed with 250 μl of 1% Triton X-100, and the contents of each well were assayed for p24 by a noncommercial ELISA as described below. All experiments were performed in duplicate, and after the broad reactivity of two cluster I gp41 MAbs was identified, one of these (MAb 246-D) was consistently used as a positive control. MAb 860-55D to parvovirus B19 was used as a negative control.

The amount of p24 captured in the virus binding assay was quantified using human anti-p24 MAb 91-5 (14) in a noncommercial p24 ELISA. For this assay, ELISA wells were coated at 4°C overnight with 100 μl of MAb 91-5 at 0.5 μg/ml. After the wells were washed with PBS-Tween 20 (PBST) and blocked with 0.2 ml of 5% BSA in PBST (BSA-PBST) for 6 h at 37°C, the lysate from the virus binding assay was added (100 μl/well). Recombinant p24 from HIV-1SF2 expressed in yeast (Chiron Corp., Emeryville, Calif.) was reconstituted to contain 250 pg/ml and then serially diluted twofold from 250 to 15.6 pg/ml, and a 100-μl sample of each concentration was added in duplicate to microtiter wells. The microtiter plates were incubated at 4°C overnight and then washed with PBST, biotinylated anti-p24 MAb 241-D (14, 45) (which recognizes a different epitope from that seen by MAb 91-5) was added, and the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 2.5 h. After subsequent washing, the plates were incubated with streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase (Life Technologies Inc., Gaithersburg, Md.) for 1 h. Color was developed with an amplification system (Life Technologies Inc.), and plates were read at 490 nm. The amount of p24 measured was determined by extrapolating the optical density value of the test sample (lysate) on the curve plotted from the values obtained with the recombinant p24.

Infectivity assay.

To determine whether MAbs bound infectious virions, the virus binding assay described above was used with some modifications. After virus was incubated on MAbs coated on microtiter wells, unbound virus particles were removed by washing four times with RPMI 1640. PBMCs, preincubated for 3 days with phytohemagglutinin (at 0.5 μg/ml) and for 2 days with interleukin-2 (at 20 U/ml), were added to the microtiter wells at 1.5 × 105 cells/well in 50 μl RPMI 1640 and incubated for 2 h in 5% CO2 at 37°C, after which 150 μl of RPMI 1640 was added. (The RPMI 1640–IL-2 medium was supplemented with 15% fetal calf serum, 3% l-glutamine, 2 μg of Polybrene per ml, 5 μg of hydrocortisone per ml, and antibiotics [penicillin and streptomycin]). The cultures were further incubated in 5% CO2 at 37°C for 3 weeks and monitored weekly for p24 production by using the noncommercial p24 ELISA described above.

Neutralization.

The ability of MAbs to neutralize HIV-1 isolates was tested in the GHOST cell neutralization assay, as previously described (7). For use in neutralization assays, the titers of virus stocks were determined on GHOST cell lines carrying the coreceptors used by each isolate so as to determine the dilution factor at which virus stocks were able to infect 200 to 1,000 GHOST cells/15,000 total cells at 3 to 5 days postinfection. The appropriate dilution of virus in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium was incubated with MAbs (at 10 μg/ml) for 1 h at 37°C. The virus-MAb mixture (110 μl/well) was then added to GHOST cells expressing the appropriate coreceptor (CCR5 or CXCR4) and incubated at 37°C in 7% CO2 overnight. The virus and antibody were then washed off, Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium was added, the mixture was incubated again for 3 to 5 days, and the cells were then analyzed for infectivity by fluorescence-activated cell sorting as previously described (7).

Statistical analysis.

We determined whether a particular MAb-virus combination displayed binding by comparing the amount of captured p24 (in picograms per milliliter) to a threshold value (45). The threshold was calculated as the mean plus 6 standard deviations of p24 from virus captured by the negative control anti-parvovirus MAb 860-55D. The threshold value (T) is 11 pg of p24/ml (log10 T = 1.04), and any value exceeding T was considered to indicate positive binding.

RESULTS

Five regions (V2, C2, V3, CD4bd, and C5) in the gp120 domain of the HIV-1 envelope of clades A to H were examined. Two regions in the gp41 domain (clusters I and II) were also examined. Binding was defined as weak if it exceeded the cutoff threshold (11 pg/ml) but reached a maximum of only 49 pg/ml. Moderate binding was defined as binding levels between 50 and 149 pg/ml, and strong binding was defined as a level that exceeded 150 pg/ml (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Binding levels of anti-gp120 and anti-gp41 MAbs to HIV-1 isolatesa

| Range of bindingb (pg of p24/ml) | No. (%) of MAb-virus test combinations reactive at different levels of binding

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-gp120

|

Anti-gp41

|

||||||

| Anti-V2 | Anti-C2 | Anti-V3 | Anti-CD4bd | Anti-C5 | Cluster I | Cluster II | |

| 0–11 | 94 (72) | 27 (52) | 276 (56) | 90 (58) | 55 (53) | 25 (19) | 74 (47) |

| 12–49 | 30 (23) | 24 (46) | 130 (26) | 47 (30) | 31 (30) | 40 (31) | 60 (39) |

| 50–149 | 5 (4) | 1 (2) | 70 (14) | 18 (12) | 12 (12) | 39 (30) | 20 (13) |

| ≥150 | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 18 (4) | 1 (0.6) | 6 (6) | 26 (20) | 2 (1) |

| Total test combinations | 130 | 52 | 494 | 156 | 104 | 130 | 156 |

The binding patterns of the various human anti-HIV-1 MAbs were determined using 26 intact native primary HIV-1 isolates of group M (clades A to H), shown in Fig. 1. Nineteen anti-V3 MAbs, 5 anti-V2 MAbs, 2 anti-C2 MAbs, 6 anti-CD4bd MAbs, 4 anti-C5 MAbs, and 11 anti-gp41 MAbs (5 to cluster I, and 6 to cluster II) were used.

Range of binding: 0 to 11, no binding; 12 to 49, weak binding; 50 to 149, moderate binding; and ≥150, strong binding.

Overall, moderate and strong cross-clade binding was observed with several anti-V3, anti-C5, and anti-gp41 cluster I MAbs (Table 2). This table shows a similar proportion of MAb-virus combinations with moderate binding for most regions but a higher proportion of MAb-virus combinations with strong binding to V3 (4%) and C5 (6%) and gp41 cluster I (20%) compared to CD4bd (0.6%), anti-V2 (0.8%), anti-C2 (0%), and cluster II (1%). Thus, a similar proportion (18%) of anti-V3–virus combinations and of anti-C5–virus combinations showed moderate and strong binding, while 50% of the anti-gp41 cluster I-virus combinations showed moderate and strong binding (Table 2). Only weak to moderate and sporadic binding characterized the reactivities of the anti-CD4bd, anti-V2, anti-C2, and anti-gp41 cluster II MAbs (Fig. 1 and Table 2).

Anti-gp120 MAb binding patterns with intact, native primary HIV-1 isolates of clades A to H. (i) anti-V3 MAbs.

A total of 19 anti-V3 MAbs were tested for their abilities to bind to 26 HIV-1 group M isolates of clades A to H, giving 494 anti-V3 MAb-virus test combinations. The log transformations of p24 values (in picograms per milliliter) are shown in Fig. 1, and the number of anti-V3–virus test combinations showing different levels of binding is shown in Table 2. Figure 1a shows the anti-V3 MAbs in rank order from the strongest average binding to all 26 isolates to the weakest average binding. (All subsequent groups of MAbs in Fig. 1 are similarly displayed.) Of the 494 individual anti-V3–virus combinations tested, 218 (44%) displayed significant levels of virus binding (as defined in Materials and Methods), with log p24 values from bound virus being greater than 1.04 (11 pg/ml). The remaining 56% of the test combinations were negative, with log p24 values from bound virus being less than 1.04. Each anti-V3 MAb was capable of binding to at least 4 of the 26 isolates. The most reactive anti-V3 MAb, 447-52D, bound to 24 of the 26 viruses (92%) of all the clades examined, although binding to the viruses of clades G and H was weak (Fig. 1a). In addition, MAbs 419-D, 694/98D, 838-D, 412-D, and 1006-15D bound to 39 to 69% of the isolates tested. These results suggest that the epitopes to which the first six anti-V3 MAbs shown at the top of Fig. 1a are directed are well exposed and conserved on 39 to 92% of the isolates of all the HIV-1 clades examined. These results also confirm previous observations (17, 45, 73) that the V3 loop is neither type-specific nor cryptic, as suggested by others (4, 49, 70). While the six most reactive anti-V3 MAbs bound to several isolates (10 to 24 viruses), other MAbs such as the last six anti-V3 MAbs listed in Fig. 1a failed to bind to most of the isolates or bound poorly and sporadically to only a few isolates. This suggests that these latter MAbs may be specific for “private” epitopes, which are more restricted in their representation on viruses within the HIV-1 family.

The converse analysis shows that every isolate could be bound by one or more anti-V3 MAbs (Fig. 1a). Some viruses among clades A, B, C, and D could bind to the majority of the anti-V3 MAbs. For example, viruses CA1 (clade A), CA5 (clade B), SG2728 (clade C), and MAL (clade D) bound to the majority of anti-V3 MAbs (Fig. 1a), indicating that several epitopes in the V3 region are exposed on some isolates belonging to different clades. However, some other viruses in the same clades (A, B, C, and D) and most viruses in clades E, F, G, and H, were bound by only a minority of anti-V3 MAbs.

Anti-V3 MAbs–virus binding did not correlate with the virus clade or virus phenotype (syncytium or non-syncytium inducing), as has previously been suggested on the basis of peptide binding (17, 73). As previously shown, the binding of MAbs to virus also did not correlate with the presence or absence of the exact sequence of the core epitope on the virus (reference 45 and data not shown).

(ii) Anti-C5 MAbs.

Four anti-C5 MAbs were tested with the 26 viruses. Two patterns of binding were observed: two MAbs bound well and across almost all the clades (MAb 670-D and 1331A) and two MAbs did not bind or bound weakly (858-D and 989-D). Those four MAbs, 670-D, 1331A, 858-D, and 989-D, bound to 21 (81%), 18 (69%), 4 (15%), and 6 (23%) of the isolates, respectively (Fig. 1a). The core epitope to which 670-D is directed (amino acids [aa] 503 to 509) is different from that recognized by 1331A, 858-D, and 989-D (aa 495 to 516) (Table 1). Because these last three MAbs recognize the same linear epitope and have similar relative affinities (unpublished data), the different pattern of binding of 1331A compared to 858-D and 989-D might be due to recognition of different conformational aspects of C5. Indeed, the conformation dependence of MAb 1331A has recently been described (24), and we have previously shown that epitope conformation may contribute as much as 90% of the binding energy of even those MAbs for which linear core epitopes can be identified (13). Thus, the data are clear that MAbs 670-D and 1331A recognize a complex conformational region of the C terminus of gp120 that is highly conserved and well exposed on the surface of virions.

(iii) Anti-CD4bd MAbs.

A total of six anti-CD4bd MAbs were tested for their abilities to bind to the 26 HIV-1 isolates. Of the eight HIV-1 clades (A to H) tested, these MAbs consistently bound to most isolates of clade D, with binding levels up to 208 pg/ml (2.3 log units) (Fig. 1b). However, binding by anti-CD4bd MAbs to isolates in clades A, B, C, E, F, G, and H was lacking in the majority of combinations and rarely exceeded weak binding. Of all six anti-CD4bd MAbs examined, only one MAb, IgG1b12, bound consistently to the isolates tested. This MAb (IgG1b12) bound to 22 of 26 isolates (85%) with moderate to strong binding (Fig. 1b). MAb 654-D was the weakest in binding and bound to only 4 of 26 isolates (15%) tested. Overall, the binding of anti-CD4bd MAbs was generally poor (Table 2). The binding patterns observed with the anti-CD4bd MAbs suggest that the epitopes to which MAbs 654-D, 448-D, 559/64, 588, and 1202 are directed are not exposed on the surfaces of most of the 26 viruses tested. The epitope to which MAb IgG1b12 is directed is better exposed and conserved on the surfaces of viruses in several clades.

(iv) Anti-C2 MAbs.

Overall, binding of the two anti-C2 MAbs (847-D and 1006-30D) to the 26 HIV-1 isolates was weak (Fig. 1b). Of the 52 MAb-virus test combinations, 24 (46%) were positive for binding, although they were weak (range, 12 to 43 pg/ml = 1.08 to 1.6 log units) (Table 2 and Fig. 1b). They bound to isolates of clades B, C, D, E, F, and G but not to isolates of clades A and H. Since only two MAbs to C2 exist and could be tested, the data reflecting the poor binding of virions to these MAbs must be taken as preliminary, suggesting that C2 is not well exposed on isolates of different clades but that this region may be conserved among some of the isolates of different clades.

(v) Anti-V2 MAbs.

Five anti-V2 MAbs were examined for their abilities to bind to 26 isolates, resulting in 130 MAb-virus test combinations. Overall, binding of these anti-V2 MAbs to the HIV-1 isolates was weak and sporadic (Fig. 1b). A total of 30 MAb-virus test combinations (23%) bound poorly (Table 2). However, five and one MAb-virus test combinations showed moderate and strong binding, respectively (Table 2). This category of MAbs bound most frequently to viruses of clades C and D. A total of 130 anti-V2/virus combinations were tested, and the results suggest that the epitopes to which these MAbs are directed are generally not well exposed on the surfaces of virions.

(vi) Anti-gp41 MAbs.

A total of 11 anti-gp41 MAbs (five to cluster I and six to cluster II) (Table 1) were used to study the exposure and conservation of gp41 epitopes on HIV-1 isolates belonging to different clades. Interestingly, the two categories of anti-gp41 MAbs demonstrated distinct patterns of binding. MAbs to cluster I bound strongly or moderately across all the HIV-1 clades examined, while MAbs to cluster II bound only moderately or poorly and sporadically to the isolates (Fig. 1c and Table 2).

Of the 130 anti-gp41 cluster I MAb-virus test combinations examined, 50% showed moderate to strong binding patterns (Table 2). In particular, MAb 246-D (to cluster I) bound well to all the isolates tested, while MAb 240-D also bound well to 24 of the 26 isolates (Fig. 1c). Indeed, MAbs 246-D and 240-D bound better than any other anti-HIV envelope MAbs tested, including those to the V3 and C5 regions of gp120. The other three cluster I MAbs (50–69, 1367, and 181-D) also bound the majority of isolates, although the binding was often weak to moderate. As in the case with the anti-C5 antibodies, this could be due to differences between the anti-cluster I MAbs in their requirements for conformational or linear structures.

Unlike the anti-gp41 cluster I MAbs, the majority of cluster II MAbs did not bind (47%) or bound only poorly (39%) to the isolates examined (Fig. 1c and Table 2). Of the 156 cluster II-virus combinations, only 20 (13%) and 2 (1%) combinations bound moderately and strongly, respectively (Table 2). Two of the MAbs (98-6 and 1342) failed to bind to most of the isolates. The data suggest that the cluster II region may be concealed in most virions, although binding of this class of MAbs was strongest to clade D viruses, as was the case for other classes of MAbs with marginal binding, such as anti-CD4bd and anti-V2 MAbs.

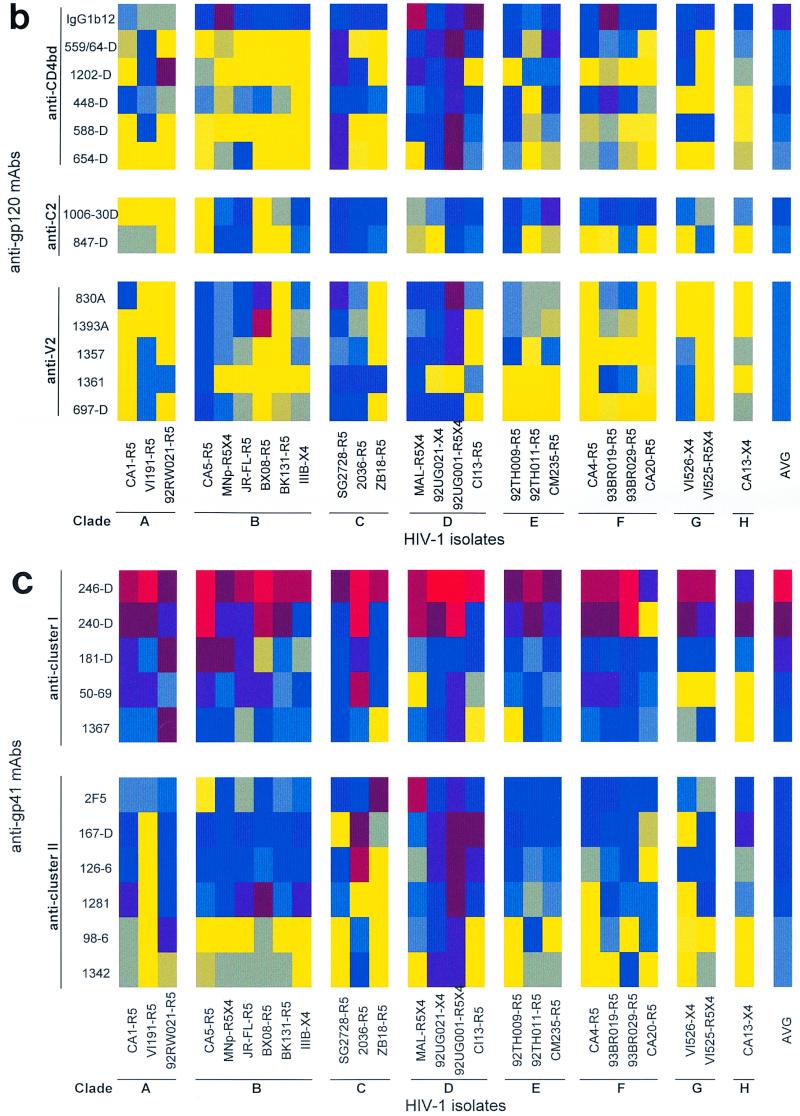

Determination of the ability of virions bound to various MAbs to infect human PBMCs.

Because models of the HIV-1 envelope structure indicate that the gp120 protein shields the gp41 molecule (34, 68, 70), it was intriguing that the anti-gp41 MAbs (246-D and 240-D) specific for the apex of gp41 bound to the isolates better than did all the other 45 anti-gp120 and anti-gp41 MAbs examined. To verify that these two anti-cluster I MAbs bound to infectious virions and that virus binding to these MAbs was not the result of exposure of gp41 due to gp120 shedding, we examined whether the virus that was bound to MAb 246-D on microtiter wells was infectious. In addition, we determined whether virus bound to anti-C5 MAb 1331A was infectious. As negative controls, anti-cluster II MAb 1342 and anti-parovirus MAb 860-55D were also tested. Thus, as described in Materials and Methods, after microtiter wells were coated with these MAbs, virus was added and unbound virus was washed off. PBMCs were then added to the microtiter wells and incubated in 5% CO2 at 37°C for a 3-week period during which p24 antigen production was monitored weekly. Two viruses (CA5 [clade B] and 93BR019 [clade F]) were used in these experiments. As expected, both viruses bound to MAb 246-D and/or to MAb 1331A with levels ranging from 84 to 197 pg/ml but did not bind to MAbs 1342 and 860-55D (Fig. 1 and 2). When PBMCs were added to wells after unbound virus had been thoroughly washed away, infection of PBMCs was demonstrated by the presence of increasing p24 production over 3 weeks when the viruses bound to MAbs 246-D and 1331-A. In cultures where nonbinding MAbs (1342 and 860-55D) were used, no infection was detected (Fig. 2). These results indicate that the MAbs displaying virion binding do indeed bind to intact, native, infectious virions.

FIG. 2.

Binding and replicative capacities of virus CA5 (a) and 93BR019 (b) upon capture with MAbs. The ability of MAbs to bind to virus was tested in quadruplicate wells with the MAbs shown in the figure and as described in Materials and Methods. After virus binding, p24 concentrations in duplicate wells were measured. The p24 concentrations recorded on day 0 reflect the amount of virus captured in the virus binding assay. PBMCs were added to two additional wells, and virus replication was monitored for 7 to 19 days by measuring p24 production.

Role of epitope conformation in MAb-virus binding.

In our previous study, we examined the ability of anti-V3 MAbs to bind to HIV-1 isolates bearing the exact or altered versions of the core epitope of the MAbs (45). The results clearly indicated that binding of MAbs to virions did not require the presence of the exact core epitope in the viral sequence, suggesting that conformation plays a critical role in the binding of MAbs to the viruses. In the present study, we examined the presence of the exact sequence of the core epitopes in the C2, C5, and gp41 regions of several isolates and the ability of the MAbs to bind to the individual virus isolates (Table 3). The results again indicated that the exact sequence of the core epitope is not required for a MAb to bind to virus. Conversely, the presence of the core epitope does not always result in binding, although binding was noted in 81% of the cases (39 of 48) where the core epitope was present (Table 3). These results, in addition to the patterns of binding observed with MAbs to discontinuous epitopes (Table 1), suggest that both the conformation and exposure of an epitope play critical roles in the binding process.

TABLE 3.

Correlation between the presence of the exact core epitopes in HIV-1 isolates and their ability to bind to the MAb recognizing that epitopea

| Isolate | Clade | Anti-C2

|

Anti-C5

|

Anti-gp41

|

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 847-D

|

1006-30D

|

670-D

|

1331-A

|

858-D

|

989-D

|

181-D (cluster I)

|

240-D (cluster I)

|

246-D (cluster I)

|

2F5 (cluster II)

|

||||||||||||

| Epitopeb | Bindingc | Epitope | Binding | Epitope | Binding | Epitope | Binding | Epitope | Binding | Epitope | Binding | Epitope | Binding | Epitope | Binding | Epitope | Binding | Epitope | Binding | ||

| CA1 | A | − | − | − | − | + | ± | − | ± | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − |

| VI191 | A | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | − |

| JRFL | B | − | ± | − | ± | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | ± | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| CA5 | B | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − |

| IIIB | B | − | ± | − | ± | + | ± | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | ± | + | + | + | ± |

| MNp | B | + | ± | + | ± | + | + | − | ± | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | ± |

| CI13 | D | − | − | − | ± | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | ± | + | + | − | ± |

| MAL | D | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | + |

| CA4 | F | − | − | − | ± | − | ± | − | ± | − | − | − | − | − | ± | − | + | − | + | − | ± |

| CA20 | F | − | − | − | ± | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | ± | + | − | + | + | − | ± |

| VI526 | G | − | − | − | ± | − | ± | − | ± | − | − | − | − | + | ± | + | + | + | + | − | ± |

| VI525 | G | − | ± | − | − | − | ± | − | ± | − | − | − | − | − | ± | + | + | − | + | − | − |

| CA13 | H | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | ± | − | − | − | ± | + | ± | + | + | + | + | − | ± |

+, binding of >49 pg/ml; ±, weak binding (12 to 49 pg/ml); −, p24 concentration of ≤11 pg/ml (see the text for more details).

Denotes the presence or absence in the test viruses of the exact core epitope recognized by each MAb (shown in Table 1). With the exception of virus JRFL, IIIB, and MNp, all viruses were grown from the cultures from which the sequences were analyzed. The sequences of JRFL, IIIB, and MNp were obtained from the Los Alamos database.

Denotes the ability of the MAb to bind to the isolate.

The conservation of the cluster I epitopes of gp41 is again evident from Table 3, which shows that 10 of 13 of the viruses examined possessed one or more of the epitopes at the apex of this immunodominant region despite the assignment of these viruses to six clades. The binding data reveal that the two MAbs which target this region (MAbs 240-D and 246-D) are highly reactive with a broad array of viruses (Table 3 and Fig. 1c), with or without the exact epitope, suggesting again that there is a conserved conformation in this region and that this region is consistently exposed on intact virions.

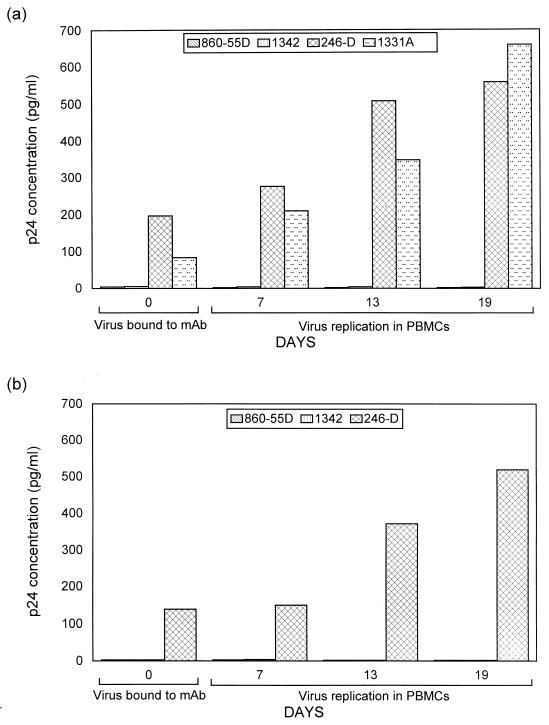

Correlation between binding of MAbs to HIV-1 isolates and neutralization of the homologous isolates.

The ability of a MAb to bind a virus isolate and to neutralize the homologous isolate was examined. This is critical to identify immunogenic epitopes that are exposed and conserved on the surface of different viruses that induce antibodies that may be relevant to protection.

A total of eight MAbs were tested for their abilities to neutralize five viruses. These MAbs were selected to include five that bound well to different isolates and three that bound poorly, if at all, to these viruses. The ability of these MAbs to neutralize these viruses was tested with the MAbs at a concentration of 10 μg/ml (the same concentration used in the virus binding assay).

Overall, the majority of MAb-virus combinations tested did not display neutralization (Table 4). Only two of the eight MAbs (447-52D and IgG1b12) achieved 90% neutralization and only one additional MAb (908-D) achieved 50% neutralization at 10 μg of MAb/ml. In most cases, binding of a MAb to a virus isolate did not correlate with the ability of the antibody to neutralize the homologous strain. Of the 27 MAb-virus combinations that showed positive binding, only 7 (26%) were associated with the ability to achieve 50% neutralization of the homologous virus and only 4 (15%) achieved 90% neutralization. Conversely, however, if a MAb neutralized a virus, it always bound to that virus, and if a MAb did not bind to a virus, it did not neutralize it.

TABLE 4.

Correlation between binding of MAb to virus and neutralization of the homologous virus

| MAb | HIV isolate

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MNp

|

CA5

|

JR-FL

|

MAL

|

BR93019

|

||||||||||

| Bindinga | Neutralizationb

|

Binding | Neutralization

|

Binding | Neutralization

|

Binding | Neutralization

|

Binding | Neutralization

|

|||||

| 50% 90% | 50% | 90% | 50% | 90% | 50% | 90% | 50% | 90% | ||||||

| 447-52D | 299 | + + | 390 | + | − | 370 | − | − | 276 | − | − | 102 | − | − |

| 419-D | 90 | − − | 50 | − | − | 57 | − | − | 64 | − | − | 18 | − | − |

| 908-12D | 104 | + − | 538 | + | − | 26 | − | − | 8 | − | − | 19 | − | − |

| IgG1b12 | 91 | + + | 36 | − | − | 43 | + | + | 208 | + | + | 94 | − | − |

| 246-D | 134 | − − | 197 | − | − | 164 | − | − | 245 | − | − | 84 | − | − |

| 98-6 | 0 | − − | 0 | − | − | 0 | − | − | 6 | − | − | 7 | − | − |

| 1367 | 25 | − − | 25 | − | − | 3 | − | − | 11 | − | − | 26 | − | − |

| 1342 | 4 | − − | 2 | − | − | 3 | − | − | 0 | − | − | 0 | − | − |

Amount of virus, measured as picograms of p24 per milliliter, detected in the virus binding assay using 10 μg of each MAb per ml.

+, 50% or 90% neutralization achieved with 10 μg of MAb per ml; −, 50% or 90% neutralization not achieved with 10 μg of MAb per ml.

DISCUSSION

Immunochemical analysis of HIV peptides, soluble gp120, and oligomeric gp160 has proved useful in studies of HIV-1 genetic and antigenic diversity. Such studies have identified antigenic regions of the envelope that are linear or conformational and have demonstrated that HIV-1 genotypes do not correlate with antigenic types, indicating that isolates of different clades have common epitopes (17, 21, 39, 46, 73). HIV-1 subunit proteins are also being evaluated in vaccine studies. Reports indicate, however, that these subunit proteins are not adequate mimics of the more complex structures present on virions (5, 38, 55, 59). Furthermore, it is probable that subunit proteins derived from a single virus from a single clade will not induce broad cross-clade protective immune responses.

Ultimately, antibodies induced by a vaccine against different HIV clades must target the native viral envelope. Therefore, the identification of the immunogenic epitopes that are conserved and expressed on the surface of intact, native HIV primary isolates of different clades are crucial to our understanding of how to design a vaccine that will be potent against the diverse clades of HIV found around the world.

However, studies using virions produced in culture could be complicated by the presence of defective virions and virions that have shed their gp120. These issues are addressed in the present study, in which we have examined the antigenic structure of HIV by using intact, native HIV-1 primary isolates of different genetic clades (A to H) and human MAbs directed at epitopes in the gp120 and gp41 envelope regions of HIV-1. With these reagents, we were able to demonstrate that epitopes in the V3, C5, and gp41 (cluster I) regions are conserved and well exposed on the surface of intact, infectious HIV-1 primary isolates of different clades irrespective of the geographic origin. The moderate and strong binding exhibited by MAb IgG1b12 to a conformational epitope in the CD4bd also suggests that this epitope is also well exposed and conserved on isolates of different clades.

Overall, 53% of the 1,222 MAb-virus combinations showed no binding. In particular, most MAbs directed at epitopes in V2 and C2 bound weakly and sporadically to the different isolates tested. With the exception of MAb IgG1b12, antibodies directed at epitopes in the CD4bd bound weakly and sporadically to the different isolates tested. Several possibilities could account for the poor binding observed with MAb directed at epitopes in these regions. (i) The envelope gp120 of HIV-1 isolates is heavily glycosylated, shielding many epitopes (1, 3, 67, 69). (ii) Some epitopes are exposed only after gp120 binds to CD4 and undergoes conformational changes, thereby exposing some epitopes and inducing antibodies that recognize the virus only at a postbinding stage (51, 53, 62). (iii) Certain point mutations on the viral envelope in these regions or in distant regions could result in a conformational change that affects the exposure of an epitope. For example, a mutation in the gp41 amino acid at position 582 is known to effect changes at a distant site (52).

Of all epitopes studied, the cluster I region of gp41 was the best exposed on the surface of HIV-1 virions. The cluster I region (aa 579 to 613) is located around the hydrophilic region of gp41 that encompasses a disulfide loop. Interestingly, two MAbs, 246-D and 240-D, directed at core epitopes LLGI and IWG, respectively, in cluster I and located at the apex of this hydrophilic immunodominant region bound strongly to all or most of the isolates tested. The data suggest that these epitopes are well exposed and conserved on the majority of the primary HIV-1 isolates of clades A to H tested. Binding of the remaining cluster I MAbs to the isolates was moderate and in some cases weak or lacking, while MAbs to the cluster II region did not bind or bound weakly to moderately at best. The extensive binding observed with the cluster I MAbs suggests that the gp120 of HIV-1 viruses does not cover the entire gp41 protein and that the cluster I region may be the most highly exposed and conserved envelope region of HIV-1 isolates belonging to different clades.

Models of the HIV envelope suggest that the noncovalent association of gp120 with gp41 entirely shields the latter. The data presented above directly test this assumption, suggest that it is incorrect, and posit that gp120 does not shield the entire gp41 protein. Alternatively, the ability of cluster I MAbs 240-D and 246-D to bind to intact virions could be the result of some or all of the gp120 molecules being shed by the virions. However, several lines of evidence suggest that this alternative is not consistent with the data. For example, if binding of the cluster I MAbs results from the shedding of gp120, one would expect that all five cluster I MAbs would bind strongly. However, only two of the five, which bind to the same region at the apex of the hydrophilic tip, actually capture virions.

Further support for the exposure of the immunodominant loop of gp41 on intact virions comes from independent studies that examined the immunoreactivity of anti-gp41 MAbs with gp41 peptides representing the pre-fusion and fusion-competent forms of the molecule (21). These studies revealed that many of the cluster I and II MAbs react strongly with gp41 peptides representing the fusion-competent molecule which one would expect to find after virions had shed their gp120 (21). However, none of these latter MAbs that recognize the fusion-competent form of gp41 bound well to intact virions. Two examples are cluster I MAb 1367 and cluster II MAb 98-6, both of which recognize the coiled coil of the fusion-competent gp41 but bind weakly, at best, to the 26 primary isolates studied here (Fig. 1c). Therefore, if MAbs 240-D and 246-D, which bind to most viruses of clades A to H, were binding because the virions had shed some or all of their gp120, allowing the formation of the fusion-competent coiled coil of gp41, one would expect these viruses to also bind to MAbs such as 1367 and 98-6. The fact that these latter MAbs do not bind suggests that extensive shedding is not occurring.

Yet another finding suggesting that the immunodominant loop of gp41 is exposed on virions that retain their gp120 comes from the data showing that virus bound by MAb 246-D is infectious (Fig. 2). If a virus sheds all or part of its gp120, the gp41 becomes well exposed but the virus becomes noninfectious or less infectious (50). The data show, however, that virions with exposed 246-D epitopes are able to infect PBMCs. Thus, three lines of evidence, summarized here, suggest that the immunodominant loop of gp41 is exposed on the surface of intact, infectious virions; the data do not support the hypothesis that this is due to gp120 shedding.

Two other regions of the envelope, besides cluster I of gp41, are well exposed on virus particles. These include the V3 and C5 regions of gp120. Genetically, the V3 loop of HIV is known to be highly variable and is one of the major regions that has been used extensively to genetically characterize HIV-1 strains into different clades (26, 36, 44). Nonetheless, the structure of the V3 is quite highly conserved, consisting of 30 to 35 aa with a βII turn at the tip and a disulfide clasp at the base. The data presented herein demonstrate that human anti-V3 MAbs bound well to 26 HIV-1 virus isolates belonging to eight different clades. In addition, MAb binding to virus did not correlate with the HIV-1 clade, with the presence of the exact sequence of the epitope on the virus, or with the phenotype or coreceptor usage (R5, X4) of the isolate. Taken together, these data suggest that the conformation of the V3 region is highly conserved and exposed on HIV-1 isolates of different clades and that the V3 region is not type specific or cryptic as previously suggested (4, 49, 70). Furthermore, the similarity in the patterns of binding of the anti-V3 MAbs to isolates of clades B, C, and F corroborate previous studies suggesting that many isolates belonging to these clades are antigenically related (65, 73).

The C5 region is also exposed and is known to be conserved (43, 60). Some models of gp120, based on studies of the monomer, propose that the C5 domain is buried (39, 40). However, the results of the present study and our previous study show that some epitopes in this region are well exposed on the surfaces of HIV-1 of different clades (45). The exposure of the C5 regions, as is evident from the binding patterns with MAbs, is consistent with the results of other studies suggesting that the C5 region is not involved in the gp120-gp41 interaction (50) and that C5 is expressed on the surface of cells infected with different strains of HIV-1 (74).

It was intriguing that the majority of isolates of clade D consistently bound to MAbs to each of the epitopes studied, although binding was weak with some of the MAbs (Fig. 1). These data suggest that the majority of the epitopes examined in the different regions of both gp120 and gp41 are exposed and conserved on most of the clade D viruses. Studies are needed to verify whether the sera of patients infected with clade D viruses induce antibodies that are extensively cross-clade reactive. In addition, the different binding patterns observed with each category of MAbs attests to the complexity of the immunologic structure of HIV-1. Deciding whether apparent patterns of binding are real requires a multivariate analysis of the data, which has recently been completed, and the results have been submitted for publication (P. Nyambi et al., submitted).

Given that several categories of antibodies can bind to the surface of HIV virions, it was important to determine if binding is sufficient to effect neutralization. To address this, we tested the ability of MAbs that bound well, and those that did not, to neutralize the homologous virus isolate. We observed that a majority of the MAbs that bound well to viruses did not neutralize the homologous isolate (Table 4). However, when a MAb neutralized an isolate, it bound to the homologous isolate when tested in the binding assay. Furthermore, when a MAb did not bind to a virus, it also lacked the ability to neutralize the virus. The results suggest that only a limited number of epitopes in the V3 and CD4bd regions that are well or moderately exposed on the surface of HIV-1 strains induce antibodies that are able to neutralize the virus. The question thus remains of what constitutes a neutralizing epitope, since many antibodies exist which are specific for exposed determinants on the virus but few cause neutralization. Indeed, many antibodies to the V3 and CD4bd have been described, but only two (447-52D and IgG1b12) display significant neutralizing activity. Partial answers come from the literature with viruses such as poliovirus and influenza virus, showing different antigenic sites on the virions involved in binding to certain “neutralization relevant and irrelevant” spikes (11, 57, 61). Thus, many antibodies may bind to the surface of a virus but only antibodies that inhibit critical, downstream steps in virus entry and replication will actively inhibit infectivity. Continued study of the epitopes of broadly neutralizing antibodies should illuminate critical steps in the virus life cycle and define the determinants that vaccines will have to target.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AI 44302, AI 32424, AI 36085, and HL 59725) and from the Department of Veterans Affairs.

We thank John Sullivan for the primary HIV-1MN isolate (MNp) and Dennis Burton and Paul Parren for the IgG1b12. We also thank Guido van der Groen for the isolates from Cameroon, Ivory Coast, Belgium, and Gabon used in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Back N K T, Smith L, Dejong J J, Keulen W, Schutten M, Goudsmit J, Tersmette M. An N-glycan within the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 V3 loop affects virus neutralization. Virology. 1994;199:431–438. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bandres J C, Wang Q F, O'Leary J, Baleaux F, Amara A, Hoxie J, Zolla-Pazner S, Gorny M K. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) envelope binds to CXCR4 independently of CD4, and binding can be enhanced by interaction with soluble CD4 or by HIV envelope deglycosylation. J Virol. 1998;72:2500–2504. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.2500-2504.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolmstedt A, Olofsson S, Sjogren-Jansson E, Jeansson S, Sjoblom I, Akerblom L, Hansen J-E S, Hu S-L. Carbohydrate determinant NeuAc-GalB(1–4) of N-linked glycans modulates the antigenic activity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 glycoprotein gp120. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:3099–3105. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-12-3099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bou-Habib D C, Roderiquez G, Oravecz T, Berman P W, Lusso P, Norcross M A. Cryptic nature of envelope V3 region epitopes protect primary monocytotropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 from antibody neutralization. J Virol. 1994;68:6006–6013. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.6006-6013.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Broder C C, Earl P L, Long D, Abedon S T, Moss B, Doms R W. Antigenic implications of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope quaternary structure: oligomer-specific and -sensitive monoclonal antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11699–11703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burton D R, Pyati J, Koduri R, Sharp S J, Thornton G B, Parren P W H I, Sawyer L S W, Hendry R M, Dunlop N, Nara P L, Lamacchia M, Garratty E, Stiehm E R, Bryson Y J, Cao Y, Moore J P, Ho D D, Barbas C F., III Efficient neutralization of primary isolates of HIV-1 by a recombinant human monoclonal antibody. Science. 1994;266:1024–1027. doi: 10.1126/science.7973652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cecilia D, KewalRamani V N, O'Leary J, Volsky B, Nyambi P N, Burda S, Xu S, Littman D R, Zolla-Pazner S. Neutralization profiles of primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates in the context of coreceptor usage. J Virol. 1998;72:6988–6996. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.6988-6996.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan D C, Kim P S. HIV entry and its inhibition. Cell. 1998;93:681–684. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81430-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conley A J, Gorny M K, Kessler II J A, Boots L J, Lineberger D, Emini E A, Ossorio M, Koenig S, Williams C, Zolla-Pazner S. Neutralization of primary HIV-1 virus isolates by the broadly-reactive anti-V3 monoclonal antibody, 447-52D. J Virol. 1994;68:6994–7000. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.11.6994-7000.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Earl P L, Doms R W, Moss B. Oligomeric structure of the human immunodeficiency virus type1 envelope glycoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:648–652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.2.648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emini E A, Jameson B A, Wimmer E. Priming for an induction of anti-poliovirus neutralizing antibodies by synthetic peptides. Nature. 1983;304:699–703. doi: 10.1038/304699a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gigler A, Dorsch S, Hemauer A, Williams C, Kim S, Young N S, Zolla-Pazner S, Wolf H, Gorny M K, Modrow S. Generation of neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies against parvovirus B19 proteins. J Virol. 1999;73:1974–1979. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.1974-1979.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gorny M K, Conley A J, Karwowska S, Buchbinder A, Xu J-Y, Emini E A, Koenig S, Zolla-Pazner S. Neutralization of diverse HIV-1 variants by an anti-V3 human monoclonal antibody. J Virol. 1992;66:7538–7542. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.12.7538-7542.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gorny M K, Gianakakos V, Sharpe S, Zolla-Pazner S. Generation of human monoclonal antibodies to HIV. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:1624–1628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.5.1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gorny M K, Mascola J R, Israel Z R, VanCott T C, Williams C, Balfe P, Hioe C, Brodine S, Burda S, Zolla-Pazner S. A human monoclonal antibody specific for the V3 loop of HIV type 1 clade E cross-reacts with other HIV type 1 clades. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1998;14:213–221. doi: 10.1089/aid.1998.14.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gorny M K, Moore J P, Conley A J, Karwowska S, Sodroski J, Williams C, Burda S, Boots L J, Zolla-Pazner S. Human anti-V2 monoclonal antibody that neutralizes primary but not laboratory isolates of HIV-1. J Virol. 1994;68:8312–8320. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.8312-8320.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gorny M K, VanCott T C, Hioe C, Israel Z R, Michael N L, Conley A J, Williams C, Kessler II J A, Chigurupati P, Burda S, Zolla-Pazner S. Human monoclonal antibodies to the V3 loop of HIV-1 with intra- and inter-clade cross-reactivity. J Immunol. 1997;159:5114–5122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gorny M K, VanCott T C, Williams C, Revesz K, Zolla-Pazner S. Effects of oligomerization on the epitopes of the HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins. Virology. 2000;267:220–228. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gorny M K, Xu J-Y, Gianakakos V, Karwowska S, Williams C, Sheppard H W, Hanson C V, Zolla-Pazner S. Production of site-selected neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies against the third variable domain of the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3238–3242. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gorny M K, Xu J-Y, Karwowska S, Buchbinder A, Zolla-Pazner S. Repertoire of neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies specific for the V3 domain of HIV-1 gp120. J Immunol. 1993;150:635–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gorny M K, Zolla-Pazner S. Recognition by human monoclonal antibodies of free and complexed peptides representing the prefusogenic and fusogenic forms of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41. J Virol. 2000;74:6186–6192. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.13.6186-6192.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gurtler G, Hauser P H, Eberle J, von Brunn A, Knapp S, Zekeng L, Tsague J M, Kaptue L. A new subtype of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (MVP5180) from Cameroon. J Virol. 1994;68:1581–1585. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.1581-1585.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hioe C E, Xu S, Chigurupati P, Burda S, Williams C, Gorny M K, Zolla-Pazner S. Neutralization of HIV-1 primary isolates by polyclonal and monoclonal human antibodies. Int Immunol. 1997;9:1281–1290. doi: 10.1093/intimm/9.9.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hochleitner E O, Gorny M K, Zolla-Pazner S, Tomer K B. Mass spectrometric characterization of a discontinuous epitope of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) envelope protein HIV-gp120 recognized by the human monoclonal antibody 1331A. J Immunol. 2000;164:4156–4161. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.8.4156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Israel Z R, Gorny M K, Palmer C, McKeating J A, Zolla-Pazner S. Prevalence of a V2 epitope in clade B primary isolates and its recognition by sera from HIV-1 infected individuals. AIDS. 1997;11:128–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Janssens W, Heyndrickx L, Fransen K, Mitte J, Peeters M, Nkengasong J N, Ndumbe P M, Delaporte E, Perret J-L, Atende C, Piot P, van der Groen G. Genetic and phylogenetic analysis of env subtypes G and H in Central Africa. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1994;10:877–879. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janssens W, Nkengasong J N, Heyndrickx L, Fransen K, Ndumbe P M, Delaporte E, Peeters M, Perret J-L, Ndoumou A, Atende C, Piot P, van der Groen G. Further evidence of the presence of genetically aberrant HIV-1 strains in Cameroon and Gabon. AIDS. 1994;8:1012–1013. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199407000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones P L, Korte T, Blumenthal R. Conformational changes in cell surface HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins are triggered by cooperation between cell surface CD4 and co-receptors. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:404–409. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.1.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karwowska S, Gorny M K, Buchbinder A, Gianakakos V, Williams C, Fuerst T, Zolla-Pazner S. Production of human monoclonal antibodies specific for conformational and linear non-V3 epitopes of gp120. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1992;8:1099–1106. doi: 10.1089/aid.1992.8.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karwowska S, Gorny M K, Buchbinder A, Zolla-Pazner S. “Type-specific” human monoclonal antibodies cross-react with the V3 loop of various HIV-1 isolates. Vaccines. 1992;92:171–174. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karwowska S, Gorny M K, Culpepper S, Burda S, Laal S, Samanich K, Zolla-Pazner S. The similarities and diversity among human monoclonal antibodies to the CD4-binding domain of HIV-1. Vaccines. 1993;93:229–232. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kessler J A, II, McKenna P M, Emini E A, Chan C P, Patel M D, Gupta S K, Mark III G E, Barbas III C F, Burton D R, Conley A J. Recombinant human monoclonal antibody IgG1b12 neutralizes diverse human immunodeficiency virus type 1 primary isolates. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1997;13:575–582. doi: 10.1089/aid.1997.13.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kostrikis L G, Bagdades E, Cao Y, Zhang L, Dimitriou D, Ho D D. Genetic analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 strains from patients in Cyprus: identification of a new subtype designated subtype I. J Virol. 1995;69:6122–6130. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.6122-6130.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kwong P D, Wyatt R, Robinson J, Sweet R W, Sodroski J, Hendrickson W A. Structure of an HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein in complex with the CD4 receptor and a neutralizing human antibody. Nature. 1998;393:648–659. doi: 10.1038/31405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leonard C K, Spellman M W, Riddle L, Harris R J, Thomas J N, Gregory T J. Assignment of intrachain disulfide bonds and characterization of potential glycosylation sites of the type 1 recombinant human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein (gp120) expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:10373–10382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Louwagie J, Janssens W, Mascola J, Heyndrickx L, Hegerich P, van der Groen G, McCutchan F E, Burke D S. Genetic diversity of the envelope glycoprotein from human immunodeficiency virus type-1 isolates of African origin. J Virol. 1995;69:263–271. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.1.263-271.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Louwagie J, McCutchan F E, Peeters M, Brennan T P, Sanders-Buell E, Eddy G A, van der Groen G, Fransen K, Gershy-Damet G-M, Deleys R, Burke D S. Phylogenetic analysis of gag genes from 70 international HIV-1 isolates provides evidence for multiple genotypes. AIDS. 1993;7:769–780. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199306000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moore J P, Cao Y, Qing L, Sattentau Q J, Pyati J, Koduri R, Robinson J, Barbas III C F, Burton D R, Ho D D. Primary isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 are relatively resistant to neutralization by monoclonal antibodies to gp120, and their neutralization is not predicted by studies with monomeric gp120. J Virol. 1995;69:101–109. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.1.101-109.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moore J P, Sattentau Q, Wyatt R, Sodroski J. Probing the structure of the human immunodeficiency virus surface glycoprotein gp120 with a panel of monoclonal antibodies. J Virol. 1994;68:469–484. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.1.469-484.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moore J P, Sodroski J. Antibody cross-competition analysis of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 exterior envelope glycoprotein. J Virol. 1996;70:1863–1872. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.1863-1872.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muster T, Guinea R, Trkola A, Purtscher M, Klima A, Steindl F, Palese P, Katinger H. Cross-neutralizing antibodies against divergent human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates induced by the gp41 sequence ELDKWAS. J Virol. 1994;68:4031–4034. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.6.4031-4034.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muster T, Steindl F, Purtscher M, Trkola A, Klima A, Himmler G, Ruker F, Katinger H. A conserved neutralizing epitope on gp41 of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1993;67:6642–6647. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.11.6642-6647.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Myers G, Korber B, Foley B, Smith R F, Jeang K-T, Mellors J W, Wain-Hobson A. Human retroviruses and AIDS. Los Alamos, N.M: Theoretical Biology and Biophysics, Los Alamos National Laboratories; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nkengasong J N, Janssens W, Heyndrickx L, Fransen K, Ndumbe P M, Motte J, Leonaers A, Ngolle M, Ayuk J, Piot P, van der Groen G. Genetic subtypes of HIV-1 in Cameroon. AIDS. 1994;8:1405–1412. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199410000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nyambi P N, Gorny M K, Bastiani L, van der Groen G, Williams C, Zolla-Pazner S. Mapping of epitopes exposed on intact HIV-1 virions: a new strategy for studying the immunologic relatedness of HIV-1. J Virol. 1998;72:9384–9391. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.9384-9391.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nyambi P N, Nkengasong J, Lewi P, Andries K, Janssens W, Fransen K, Heyndrickx L, Piot P, van der Groen G. Multivariate analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 neutralization data. J Virol. 1996;70:6235–6243. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.6235-6243.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nyambi P N, Nkengasong J, Peeters M, Simon F, Eberle J, Janssens W, Fransen K, Willems B, Vereecken K, Heyndrickx L, Piot P, van der Groen G. Reduced capacity of antibodies from patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus type-1 (HIV-1) group O to neutralize primary isolates of HIV-1 group M viruses. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:1228–1237. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.5.1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nyambi P N, Willems B, Janssens W, Fransen K, Nkengasong J, Peeters M, Vereecken K, Heyndrickx L, Piot P, van der Groen G. The neutralization relationship of HIV type 1, HIV type 2, and SIVcpz is reflected in the genetic diversity that distinguishes them. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1996;13:7–17. doi: 10.1089/aid.1997.13.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Palker T J, Clark M E, Langlois A J, Matthews T J, Weinhold K J, Randall R R, Bolognesi D P, Haynes B F. Type-specific neutralization of the human immunodeficiency virus with antibodies to env-encoded synthetic peptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:1932–1936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.6.1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Park E J, Quinnan G V., Jr Both neutralization resistance and high infectivity phenotypes are caused by mutations of interacting residues in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 leucine zipper and the gp120 receptor- and coreceptor-binding domains. J Virol. 1999;73:5707–5713. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5707-5713.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Posner M R, Hideshima T, Cannon T, Mukherjee M, Mayer K H, Byrn R. Human monoclonal antibody that reacts with HIV-1/gp120 inhibits virus binding to cells and neutralizes infection. J Immunol. 1991;146:4325–4332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reitz M S, Wilson C, Naugle C, Gallo R C, Robert-Guroff M. Generation of a neutralization-resistant variant of HIV-1 is due to selection for a point mutation in the envelope gene. Cell. 1988;54:57–63. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90179-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rizzuto C D, Wyatt R, Hernandez-Ramos N, Sun Y, Kwong P D, Hendrickson W A, Sodroski J. A conserved HIV gp120 glycoprotein structure involved in chemokine receptor binding. Science. 1998;280:1949–1953. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roques P, Menu E, Narwa R, Scarlatti G, Tresoldi E, Damond F, Mauclere P, Dormont D, Chaouat G, Simon F, Barre-Sinoussi F The European Network on the Study of In Utero Transmission of HIV-1. An unusual HIV type 1 env sequence embedded in a mosaic virus from Cameroon: identification of a new env clade. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1999;15:1585–1589. doi: 10.1089/088922299309883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sattentau Q J, Moore J P. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 neutralization is determined by epitope exposure on the gp120 oligomer. J Exp Med. 1995;182:185–196. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.1.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sattentau Q J, Moore J P, Vignaux F, Traincard F, Poignard P. Conformational changes induced in the envelope glycoproteins of the human and simian immunodeficiency viruses by soluble receptor binding. J Virol. 1993;67:7383–7393. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.7383-7393.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schofield D J, Stephenson J R, Dimmock N J. High and low efficiency neutralization epitopes on the haemagglutinin of type A influenza virus. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:2441–2446. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-10-2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Simon F, Mauclere P, Roques P, Loussert-Ajaka I, Muller-Trutwin M C, Saragosti S, Georges-Coubot M C, Barre-Sinoussi F, Brun-Vezinet F. Identification of a new human immunodeficiency virus type 1 distinct from group M and group O. Nat Med. 1998;4:1032–1037. doi: 10.1038/2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stamatatos L, Cheng-Mayer C. Structural modulations of the envelope gp120 glycoprotein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 upon oligomerization and differential V3 loop epitope exposure of isolates displaying distinct tropism upon virion-soluble receptor binding. J Virol. 1995;69:6191–6198. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.6191-6198.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Starcich B R, Hahn B H, Shaw G M, McNeely P D, Modrow S, Wolf H, Parks E S, Parks W P, Josephs S F, Gallo R C, Wong-Staal F. Identification and characterization of conserved and variable regions in the envelope gene of HTLV-III/LAV, the retrovirus of AIDS. Cell. 1986;45:637–648. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90778-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Taylor H P, Armstrong S J, Dimmock N J. Quantitative relationships between an influenza virus and neutralizing antibody. Virology. 1987;159:288–298. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90466-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thali M, Moore J P, Furman C, Charles M, Ho D D, Robinson J, Sodroski J. Characterization of conserved HIV-type 1 gp120 neutralization epitopes exposed upon gp120-CD4 binding. J Virol. 1993;67:3978–3988. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.3978-3988.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Trkola A, Pomales A B, Yuan H, Korber B, Maddon P J, Allaway G P, Katinger H, Barbas III C F, Burton D R, Ho D D, Moore J P. Cross-clade neutralization of primary isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by human monoclonal antibodies and tertrameric CD4-IgG. J Virol. 1995;69:6609–6617. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6609-6617.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vanden Haesevelde M, Decourt J-L, De Leys R, Vanderborght B, van der Groen G, van Heurverswijn H, Saman E. Genomic cloning and complete sequence analysis of a highly divergent African human immunodeficiency virus isolate. J Virol. 1994;68:1586–1596. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.1586-1596.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Verrier F, Burda S, Belshe R, Duliege A-M, Excler J-L, Klein M, Zolla-Pazner S. Prime/boost immunization of humans induces antibodies that are broadly cross-reactive with V3 peptides and recombinant gp120 from several clades, and neutralize several X4-, R5-, and dual-tropic, clade B and C primary isolates. Molecular approaches to vaccine design. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Weissenhorn W, Dessen A, Harrison S C, Skehel J J, Wiley D C. Atomic structure of the ectodomain from HIV-1 gp41. Nature. 1997;387:426–430. doi: 10.1038/387426a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wu Z, Kayman S C, Honnen W, Revesz K, Chen H, Vijh-Warrier S, Tilley S A, McKeating J, Shotton C, Pinter A. Characterization of neutralization epitopes in the V2 region of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120: role of glycosylation in the correct folding of the V1/V2 domain. J Virol. 1995;69:2271–2278. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2271-2278.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wyatt R, Desjardin E, Olshevsky U, Nixon C, Binley J, Olshevsky V, Sodroski J. Analysis of the interaction of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 envelope glycoprotein with the gp41 transmembrane glycoprotein. J Virol. 1997;71:9722–9731. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9722-9731.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wyatt R, Kwong P D, Desjardins E, Sweet R W, Robinson J, Hendrickson W A, Sodroski J G. The antigenic structure of the HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein. Nature. 1998;393:705–711. doi: 10.1038/31514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wyatt R, Sodroski J. The HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins: fusogens, antigens and immunogens. Science. 1998;280:1884–1888. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wyatt R, Sullivan N, Thali M, Repke H, Ho D D, Robinson J, Posner M, Sodroski J. Functional and immunologic characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoproteins containing deletions of the major variable regions. J Virol. 1993;67:4557–4565. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.4557-4565.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Xu J-Y, Gorny M K, Palker T, Karwowska S, Zolla-Pazner S. Epitope mapping of two immunodominant domains of gp41, the transmembrane protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1, using ten human monoclonal antibodies. J Virol. 1991;65:4832–4838. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.9.4832-4838.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zolla-Pazner S, Gorny M K, Nyambi P N, VanCott T C, Nadas A. Immunotyping of HIV-1: an approach to immunologic classification of HIV. J Virol. 1999;73:4042–4051. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.4042-4051.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zolla-Pazner S, O'Leary J, Burda S, Gorny M K, Kim M, Mascola J, McCutchan F E. Serotyping of primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates from diverse geographic locations by flow cytometry. J Virol. 1995;69:3807–3815. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3807-3815.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]