Abstract

Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) latent infection in vivo is characterized by the constitutive expression of the latency-associated transcripts (LAT), which originate from the LAT promoter (LAP). In an attempt to determine the functional parts of LAP, we previously demonstrated that viruses harboring a DNA fragment 3′ of the LAT promoter itself were able to maintain detectable promoter expression throughout latency whereas viruses not containing this element could not (J. R. Lokensgard, H. Berthomme, and L. T. Feldman, J. Virol. 71:6714–6719, 1997). This element was therefore called a long-term expression element (LTE). To further study the role of the LTE, we constructed plasmids containing a DNA fragment encompassing the LTE inserted into a synthetic intron between the reporter lacZ gene and either the LAT or the HSV-1 thymidine kinase promoter. Transient-expression experiments with both neuronal and nonneuronal cell lines showed that the LTE locus has an enhancer activity that does not activate the cytomegalovirus enhancer but does activate the promoters such as the LAT promoter and the thymidine kinase promoter. The enhancement of these two promoters occurs in both neuronal and nonneuronal cell lines. Recombinant viruses containing enhancer constructs were constructed, and these demonstrated that the enhancer functioned when present in the context of the viral DNA, both for in vitro infections of cells in culture and for in vivo infections of neurons in mouse dorsal root ganglia. In the infections of mouse dorsal root ganglia, there was a very high level of promoter activity in neurons infected with viruses bearing the LAT promoter-enhancer, but this decreased after the first 2 or 3 weeks. By 18 days postinfection, neurons harboring latent virus without the enhancer showed no β-galactosidase (β-gal) staining whereas those harboring latent virus containing the enhancer continued to show β-gal staining for long periods, extending to at least 6 months postinfection, the longest time examined.

A hallmark of herpesviruses is the ability to establish a lifelong latent infection in their hosts. Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) establishes a latent infection in neurons of the peripheral nervous system in both their natural host, humans, and a variety of animal models (29). During the course of latency, virtually no expression can be detected from the many genes of the lytic cycle. Instead, only a single region of the viral DNA expresses RNA transcripts of sufficient quantity to be detected by in situ hybridization. These viral RNAs are the latency-associated transcripts (LATs), which originate in a region in the long repeat elements of the viral genome (6, 7, 25, 27, 32, 33). The latency-associated promoter (LAP) is thought to express a single primary LAT, referred to as the minor LAT, which is then spliced, leading to two abundant RNA species referred to as the major LAT RNAs (2, 11, 35–38). These major LAT RNAs, of 1.5 and 2 kb, are stable introns which are antisense to part of the third exon of the ICP0 mRNA (8, 13).

Since the discovery of the LAT RNAs, there has been speculation about their function. The strong accumulation of these RNAs in the nuclei of the latently infected cells in vivo led several laboratories to examine their role in the establishment and maintenance of latency and reactivation. Previous studies showed that viruses with the LAT introns or the LAP deleted were very capable of establishing a latent infection (19, 20). On the other hand, viruses with part or all of the LAP deleted were deficient in reactivation from the latent state (3, 18, 22). Therefore, for many years it was accepted that LAP mutants grew equally as well as wild-type viruses in sensory neurons in vivo and established latency as well but failed to reactivate. However, other reports have questioned this statement and shown that deletion of LAP reduced the ability of such mutant viruses to enter the latent state (30, 34), indicating that the LAT locus may promote latent infection. In addition, another study showed that mutant viruses unable to produce LATs synthesize productive-cycle genes in a greater number of neurons in vivo than wild-type viruses do (16). In that report, the authors hypothesized that this ability to grow better during the acute infection in vivo could lead to an enhanced neuronal cell death, which could explain the reduced frequency for reactivation of the LAT− viruses.

We were interested in how the LAP remains active in latently infected neurons in vivo whereas all other viral promoters fail to express RNA after the first week of infection. Previously, we and others have reported that viruses containing reporter constructs driven by the LAP only do not remain active well into latency but instead appear to shut off transcription some time during the first week or two of infection. We later found that a region downstream of the LAT transcription start site appeared to restore the ability of the LAP to continue to function during latency. We term this region of the LAT transcription unit the long-term expression element (LTE) region (23). In this study, insertion of a DNA fragment of more than 1 kb between the LAP and the lacZ gene allowed the LAP to continue to function throughout latency, as demonstrated by RNase protection assays of lacZ mRNA. Similarly, Perng et al. showed by reverse transcription-PCR analysis that viruses harboring the LAT promoter and the downstream 1.5kb of DNA were able to continue synthesizing RNA during latency (27). Also, Lachman and Efstathiou showed that by inserting an IRES element between the LAT promoter and this region, expression during latency was observed (21).

To further map the LTE function within this large viral DNA fragment, we wanted to make deletions of this sequence for insertion into recombinant viruses. Because the lacZ mRNA is rather unstable, we needed a more sensitive assay for measuring LTE function during latency. To this end, we placed the DNA fragment encoding the LTE function within an intron. This allowed its insertion between the LAP and the lacZ gene without disrupting translation of the lacZ mRNA. By this technique, we were able to measure LAP activity in vivo by measuring β-galactosidase activity, an approach that is both more sensitive and more convenient than the RNase protection assay.

Using different recombinant viruses based on this approach, we found that the LTE region substantially increased LAP activity, both in the context of plasmid DNA in transient-transfection assays and in the context of viral DNA. In infections using recombinant viruses in vivo, the presence of the LTE region enhanced LAP activity during the first weeks of infection. Thereafter, the activity declined but the presence of the enhancer kept the LAP far more active throughout latency than was found in viruses lacking the enhancer. These experiments not only highlight the existence of a new function within the LAT region but also may shed some light on the mechanism by which viruses containing this region continue transcription throughout latency.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

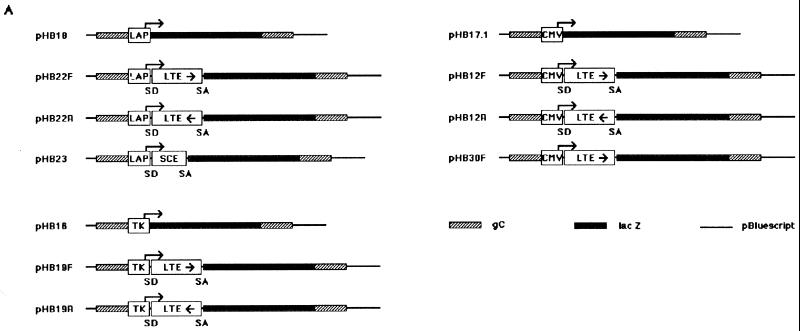

The plasmids used in this study are displayed in Fig. 1A. Plasmid pHB18 was derived, with minor modifications, from plasmid pJA1 described previously (23). It contains the LAP extending from a SmaI site to a SacII site (positions 117938 to 118843 on the HSV-1 genome) upstream from the reporter gene lacZ (from pCH110; Pharmacia). Plasmids pHB22F and pHB22R were derived from pHB18 by first inserting the LTE sequence from a PstI site to a HpaI site (positions 118862 to 120303) as a BamHI-BglII fragment into the BglII site of the intron sequence (GGATCCAGGTAAGCCTAGATCTCTAACCATGTTCATGCCTTCTTTTCCTAGGATCC) either in the forward (pHB22F) or in the reverse (pHB22R) orientation and then inserting the LTE-intron sequence as a BamHI-BamHI fragment into a BamHI site between LAP and lacZ of pHB18. Plasmid pHB23 was similar to pHB22F, but the LTE sequence was replaced by an inverted 855-bp DNA fragment internal to the coding sequence of the I-Sce1 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Plasmids pHB17.1, pHB12F, and pHB12R are the counterparts of pHB18, pHB22F, and pHB22R, respectively, with the LAP being replaced by the cytomegalovirus (CMV) enhancer-promoter. Plasmid pHB30F was derived from pHB17.1 by inserting the LTE sequence (BamHI-BglII fragment) alone in the forward orientation into the BamHI site between the CMV promoter and the lacZ gene of pHB17.1. Plasmids pHB16, pHB19F, and pHB19R are the counterparts of pHB18, pHB22F, and pHB22R, respectively, with the LAP being replaced by the HSV-1 thymidine kinase (TK) promoter (from a PvuII site at position 48108 to a BglII site at position 47855).

FIG. 1.

Graphic map of the DNA structures of plasmids and viruses. (A) Plasmids were constructed by inserting either the CMV enhancer/promoter, the LAP, or the HSV-1 TK promoter upstream from the reporter gene lacZ. The presence of the LTE region and the synthetic intron are indicated by the LTE box and the splice donor (SD) and the splice acceptor (SA) sites, respectively. Arrows show the orientation of the inserted LTE or Sce (internal fragment of the I-SceI gene of S. cerevisiae) sequences. All transcriptional units were flanked with sequences from the HSV-1 gC gene, to allow the recombination at the gC locus of virus KOS dl1.8 HSV-1 (21), leading to KOS18, KOS22F, and KOS22R viruses. (B) Complete genome of HSV-1 and an expanded view of the long internal repeat (IRL). Positions on the HSV-1 genome as well as the flanking restriction sites of the LAP and LTE sequences used in this study are also indicated. The bottom line shows the region of the LAT intron (dark rectangle) and its overlap with the third exon of the ICP0 mRNA.

Cells and viruses.

African green monkey kidney (Vero), rabbit skin (RS), and ND7 cells were maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium plus 10% fetal bovine serum, in Earle's minimum essential medium plus 5% newborn calf serum, and RPMI 1640 medium plus 10% fetal bovine serum, respectively. All media were also supplemented with penicillin and streptomycin and were buffered with sodium bicarbonate. Vero cells were used for selection, propagation, and titer determination of the recombinant viruses. RS and ND7 cells were used for gene expression analysis following transfection of plasmids or productive infection.

The recombinant viruses described in this report, hereafter designated KOS18, KOS22F, and KOS22R, were constructed by recombination at the gC locus between the parental virus KOS dl1.8 HSV-1 (kindly provided by David Leib [22]) and plasmids pHB18, pHB22F, and pHB22R, respectively. These viruses were selected, plaque purified, and produced as previously described (10).

Animal inoculation.

All animals were manipulated using institutionally approved animal welfare procedures. Experiments were carried out essentially as previously described (10). Briefly, 6-week-old female Swiss Webster mice were anesthetized by ether inhalation and a 10% NaCl solution was injected subcutaneously in the footpads. After 3 h, the mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital (60 mg/kg). The skin of the footpads was removed, and 107 PFU of the viral stocks was applied on each footpad. The infections were carried out for at least an hour.

Histochemical staining.

At the times indicated in Fig. 5, infected mice were euthanized by Halothane inhalation and exsanguinated by transcardiac perfusion with phosphate-buffered-saline (PBS) through the left ventricle after cutting the right atrium. The mouse tissue was fixed with a PBS solution containing 2% formaldehyde and 0.2% glutaraldehyde. The L3 to L6 dorsal root ganglia (DRG) were surgically removed and further fixed for 15 min in the same fixative solution. Histochemical staining was conducted exactly as previously described (10).

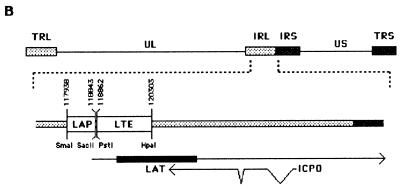

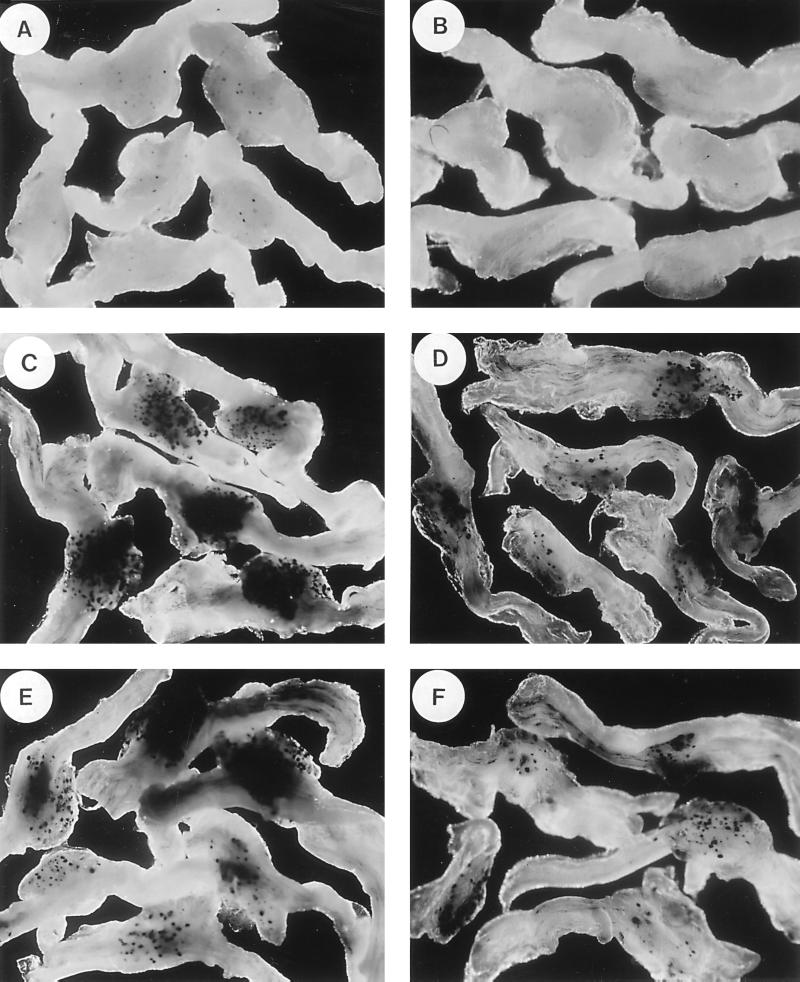

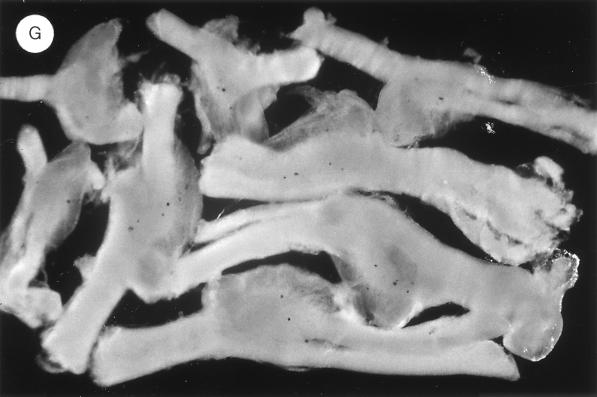

FIG. 5.

β-Galactosidase activity in whole-mount infected DRG by histochemical staining. Swiss Webster mice were inoculated with KOS18, KOS22F, and KOS22R, and DRG were removed and stained as indicated in Materials and Methods. L3, L4, and L5 DRG infected by KOS18 at 4 days p.i. (A) or 12 days p.i. (B), by KOS22F at 4 days p.i. (C) or 12 days p.i. (D), by KOS22R at 4 days p.i. (E) or 12 days p.i. (F), or by KOS22F at 6 months p.i. (G) are shown.

Immunohistochemistry.

At the times indicated in Fig. 7, mice were euthanized by carbon dioxide inhalation and transcardiac perfusion with PBS (pH 7.2) followed by perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. The dorsal root ganglia from three experimental animals were then removed, combined, and immersion fixed at 4°C in 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 h. Fixed tissue was then equilibrated with 20% sucrose, embedded in OCT, and frozen in liquid nitrogen (23). Serial sections (6 μm) were cut from frozen ganglia and collected as five alternative sets onto a Superfrost plus slide (Fisher). The tissue slides were stored at −20°C.

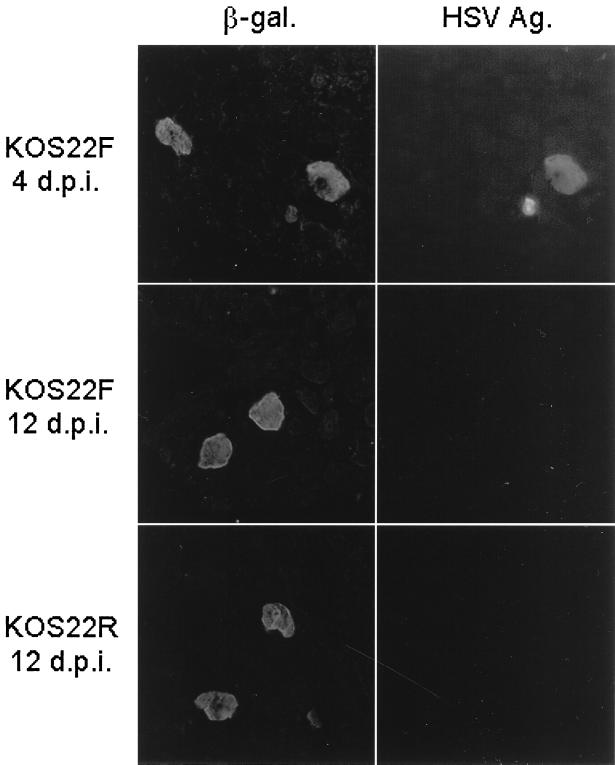

FIG. 7.

Immunodetection of β-galactosidase (β-gal.) and HSV-1 antigens (Ag.) on infected DRG sections. Swiss Webster mice were inoculated with KOS22F and KOS22R viruses. At the indicated time, DRG were removed, equilibrated with 20% sucrose, embedded in OCT, and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Serial sections (6 μm), were cut, stained for β-galactosidase and HSV-1 antigens, and evaluated under a fluorescence microscope.

For dual-immunofluorescence studies of β-galactosidase and HSV antigen expression, tissue sections were first incubated for 1 h at room temperature with rabbit anti-β-galactosidase antiserum (Cappel, Durham, N.C.) diluted 1:700 in PBS. Tissue sections were then sequentially incubated with biotinylated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (Vector Labs, Burlingham, Calif.) for 1 h, rhodamine600 avidin D (Vector) diluted 1:1,200 for 40 min, and biotinylated goat anti-avidin D diluted 1:1,200 for 40 min. After being washed, the sections were blocked with 10% normal rabbit serum for 10 min and incubated for 40 min with both fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated rabbit anti-HSV-1 (Dako Corp., Carpinteria, Calif.) diluted 1:100 and rhodamine600 avidin D diluted 1:1,200. Sections were then washed and mounted with coverslips using Vectashield (Vector). Stained slides were evaluated using a Nikon fluorescence photomicroscope.

Quantification of β-galactosidase activity.

Tissue culture plates (60 mm) containing 1 × 106 (transfection) or 3 × 106 (infection) RS (fibroblast) or ND7 (neuronal) cells were either transfected with 2 μg of DNA of the indicated plasmids previously mixed with 10 μl of Lipofectin as specified by the manufacturer (Gibco) or infected at a multiplicity of infection of 3 PFU/cell. At 2 days postinfection (p.i.) or at 2 days posttransfection the cells were harvested in 200 μl of PBS and immediately frozen.

Unfixed L3 to L6 DRG from infected mice (three mice per time point per virus) were removed as indicated above and immediately frozen. Cellular extracts were produced by grinding these DRG in 200 μl of ice-cold PBS in a 0.1-ml Dounce homogenizer. Prior to use, the cells were frozen and thawed three times and cellular debris were briefly microcentrifuged. Aliquots (10 to 40 μl) of the supernatants were incubated in the previously described in vitro β-galactosidase assay (9), using chlorophenolred-β-d-galactopyranoside (CPRG; Sigma) as the substrate.

RESULTS

Validation of the intron strategy.

We previously showed that a DNA fragment 3′ of the LAP but within the LAT transcription unit was able to support long-term expression of the LAP during latency (23). Because the lacZ mRNA was relatively unstable, leading to a signal barely detectable by the RNase protection assay, it was difficult to quantify the effect of the LTE on the activity of LAP. Another difficulty of the previous assay system is that the presence of the LTE sequence, inserted between the promoter and the lacZ coding region, prevented translation of the lacZ mRNA (23). To address these problems, we inserted the LTE DNA fragment (positions 118862 to 120303) into a cassette flanked by the consensus splice donor, branch point, and splice acceptor sites and cloned the LTE/intron sequence between the promoters and the lacZ reporter gene (see Materials and Methods) (Fig. 1A). This construction should allow the LTE region to function while allowing translation of the reporter gene, which would increase the sensitivity of our assays. To demonstrate the effect of the splicing signals on mRNA translation, we inserted the LTE, either alone or within an intron, between the CMV immediate-early enhancer-promoter and the lacZ gene. We then transfected the plasmids in RS cells and analyzed the reporter gene expression using an in vitro enzymatic assay to quantify the β-galactosidase activity. As shown in Fig. 2, β-galactosidase activity is very high for transfection of a control plasmid in which the CMV immediate-early enhancer is driving the lacZ gene, pHB17.1. Insertion of the LTE fragment without flanking intron signals, pHB30F, blocked the majority of lacZ expression (compare pHB17.1 to pHB30F). By contrast, insertion of the LTE as an intron between the promoter and the lacZ gene resulted in transient-transfection assays with high levels of β-galactosidase activity. This was true whether the LTE was inserted in the forward (natural) direction, pHB12F, or in the reverse direction, pHB12R. In each case, the level of expression was very similar to that obtained with the CMV-driven lacZ gene, pHB17.1. In other words, insertion of the LTE within the context of an intron allowed efficient translation of the lacZ mRNA but did not decrease or increase the level of expression compared to that obtained with a plasmid lacking the LTE and splicing signals. From these results, we conclude that insertion of the LTE without splicing signals prevented efficient expression of a downstream coding sequence (as stated previously) and that the LTE/intron sequence merely restored the same level of CMV promoter-enhancer activity. Therefore, we could apply this approach to other experiments to further analyze the role of the LTE.

FIG. 2.

β-Galactosidase activity from transfections of the CMV promoter plasmids. Dishes (60 mm) containing 106 RS cells were transfected independently with 2 μg of DNA of plasmids pHB17.1, pHB30F, pHB12F, and pHB12R. At 2 days post-transfection, β-galactosidase activity was determined in vitro using CPRG as the substrate. Values are indicated as the mean of experiments conducted in triplicate and are expressed as fold increase over background.

The LTE region has an enhancer activity for the LAP.

To construct viruses containing the LTE/intron in the context of the LAP, we first constructed a set of plasmids and examined their expression in transient-transfection assays. In our previous work, we had inserted a similar but slightly shorter LTE DNA fragment between the LAP and the lacZ gene. As explained in the introduction, this LTE fragment blocked translation of the lacZ mRNA (24). We again transfected this construct, under the CMV enhancer, in pHB30 (see above) and again observed a strong block of translation, which was alleviated when the LTE fragment was placed in an intron. Because we had already shown that the LAP-LTE constructs were not translated, we excluded them from further study here. Instead, a control plasmid, pHB18, was constructed, in which the LAP was placed in front of the lacZ gene (Fig. 1A). The activity of this plasmid was compared to that of two others in which the LTE was inserted in the context of an intron between the LAP and the lacZ gene, in either the forward (pHB22F) or the reverse (pHB22R) direction (Fig. 1A). These three plasmids were transfected into ND7 cells, a neuronal cell line representing a fusion between neuroblastoma cells and a primary culture of neurons originating from DRG. Surprisingly, plasmids containing the LTE within an intron (pHB22F and pHB22R) showed a high increase in lacZ expression compared to the plasmid (pHB18) lacking an LTE (Fig. 3A). Thus, the result of inserting the LTE DNA fragment into an intron between the LAT promoter and lacZ was to increase lacZ expression. To show that this increased expression was due specifically to the LTE, a DNA fragment from the I-Sce1 gene of S. cerevisiae was inserted in the reverse orientation into the intron in place of the LTE, leading to plasmid pHB23. The transient-expression experiment performed with pHB18, pHB22F, pHB22R, and pHB23 in ND7 cells showed that this I-Sce1 DNA fragment was not able to increase the expression of lacZ (Fig. 3B). Therefore, the LTE sequence is able to specifically increase the expression of the reporter gene when placed in an intron between LAP and lacZ, in a manner independent of its orientation. Considering that the LTE, when not placed in the context of an intron, was unable to increase the expression of either the LAT or the CMV enhancer (23) (Fig. 2), it is unlikely that the increased expression of pHB22F and pHB22R over the control pHB18 is due to the activity of a promoter within the LTE. Furthermore, if this activity were due to a promoter, one would expect it to be directional; thus, the fact that both orientations of the LTE increased the level of expression of the LAT promoter also suggests that the LTE does not contribute a promoter-like activity in these transfections.

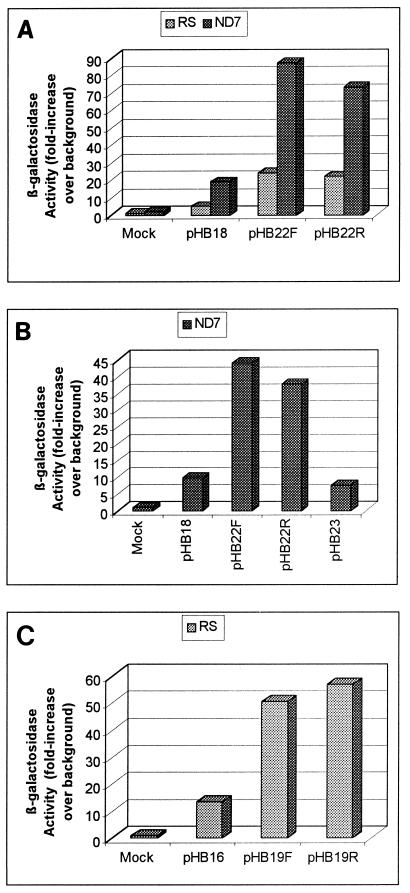

FIG. 3.

β-Galactosidase activity from transfections of the LAT or TK promoter plasmids. (A and B) Plasmids pHB18, pHB22F, pHB22R, and pHB23 were all or partly used to transfect RS (A) or ND7 (B) cells independently as described in Materials and Methods. (C) Similarly, plasmids pHB16, pHB19F, and pHB19R were transfected in RS cells. At 2 days posttransfection, β-galactosidase activity was measured using the CPRG assay. Values are indicated as the mean of experiments conducted in triplicate and are expressed as fold increase over background.

The LTE enhancer activity is not tissue specific or promoter specific.

To determine if the LTE functions in a tissue-specific manner, rabbit skin cells (fibroblasts) were transfected with the three plasmids, pHB18, pHB22F, and pHB22R. The results showed a similar fold increase in lacZ gene expression for both pHB22F and pHB22R over pHB18 in these cells to that in ND7 cells (Fig. 3A). Therefore, the enhancer function of the LTE sequence seemed not to be specific to a particular cell line.

To study a potential effect of the LTE region on another promoter than LAP, another set of plasmids was also constructed. Plasmids pHB16, pHB19F, and pHB19R, bearing the lacZ gene downstream from an early viral promoter, the TK promoter (position 48108 to position 47855), alone (pHB16) or with the LTE inserted in the forward (pHB19F) or reverse (pHB19R) orientation into the intron (Fig. 1a) were then transfected into RS cells. The results of this transient-expression experiment showed that lacZ expression from pHB19F and pHB19R was significantly higher than that from pHB16 (Fig. 3C), suggesting that the LTE enhancer can function with another promoter than LAP and is therefore not specific to a promoter.

The LTE region increases gene expression in an orientation-dependent manner during productive infection in vitro.

To study the effect of the LTE region on the activity of the LAT promoter in the context of the virus, the three plasmids pHB18, pHB22F, and pHB22R were inserted into the gC locus of HSV-1. Because of the extensive homology to the two copies of the LTE and LAP in the long repeat regions, HSV-1 KOS dl1.8, a LAT region deletion virus described previously by Leib et al. (22), was used as the parental strain. Recombinant viruses were screened for the insertion of the lacZ gene and plaque purified a total of five times. The DNA structure of each recombinant virus was verified by Southern blot hybridization (data not shown). RS cells and ND7 cells were infected at a multiplicity of infection of 3 PFU per cell. At 2 days later, the infected cells were harvested and β-galactosidase activity was determined using an in vitro enzymatic assay. As shown in Fig. 4, there was no significant difference in lacZ expression between KOS18 and KOS22R. Only KOS22F-infected cells showed an increase beyond the control KOS18-infected cells. Since it has been shown that the ICP4 protein down regulates the LAP during productive infection by binding to the ICP4 binding motif at the LAP cap site (1, 2, 14), we assume that LAP is repressed in all three viruses during the lytic cycle. Therefore, the lacZ expressions observed with KOS18 and KOS22R corresponded to a background expression from cells infected with lacZ coding sequence-containing viruses. As expected from our previous study of LAP activity, the background expression from KOS18, KOS22F, and KOS22R is much higher in ND7 than in RS cells (9).

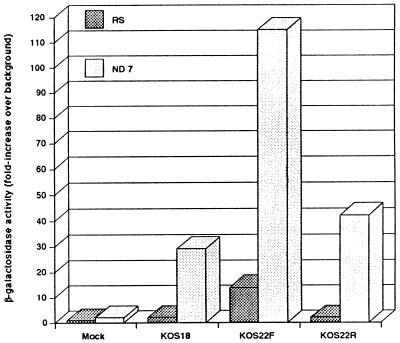

FIG. 4.

β-Galactosidase activity from infected RS and ND7 cells in culture. RS and ND7 cells grown to near confluence were either mock infected or infected with KOS18, KOS22F, and KOS22R independently at a MOI of 3 PFU per cell. These viruses corresponded respectively to the insertion of plasmid pHB18, pHB22F, and pHB22R at the gC locus of the parental KOS dl1.8 HSV-1 (21). At 2 days p.i., cells were harvested and lysed and β-galactosidase activity was determined using the CPRG assay. Values are indicated as the mean of experiments conducted in triplicate and are expressed as fold increase over background.

lacZ expression arising from KOS22F-infected cells was significantly higher than that from KOS18- and KOS22R-infected cells in the same infected cell line, indicating that the lacZ gene is highly expressed during productive infection in vitro only when the LTE is inserted into the intron in the forward orientation. These results, markedly different from those obtained in transient expression with the plasmids, showed that lacZ gene expression is dependent on the orientation of the LTE. The LTE contains LAP2, a viral promoter that is active only in the lytic cycle (17). Although LAP2 expression could explain the increased expression from virus 22F, it is several hundred bases from the splice acceptor site and would require the utilization of a cryptic splice donor site to avoid several ATG codons upstream of the lacZ gene. Perhaps a more likely reason for increased expression from the 22F virus is the presence of a TATA element just upstream of the HpaI site, only a short distance from the end of the LTE. This TATA box would be activated by ICP4, rather than repressed; furthermore, this element is very far away from the lacZ gene in virus KOS22R.

The LTE region increased gene expression during acute and latent infection in vivo.

To examine the effect of the LTE on LAP expression in vivo, mice were infected via the footpads of the rear limbs. On days 4 and 12, DRG were removed and analyzed for β-galactosidase activity by in situ staining. As shown in Fig. 5, whole ganglia stained for β-galactosidase activity showed a large increase in KOS22F- and KOS22R-infected ganglia compared to KOS18-infected ganglia at 4 days p.i. By 12 days p.i., both KOS22F and KOS22R showed less total activity than on day 4 but substantially more activity than KOS18 on day 12, for which no detectable expression was observed.

To quantify the lacZ gene expression and to examine the effect of the enhancer over a longer period of latency, we extended the period of infection. At 4, 12, and 28 days p.i., unfixed L3 to L6 DRG were removed and used to produce cellular extracts, which were subsequently analyzed for β-galactosidase activity in an in vitro quantitative assay (CPRG assay). The results showed that at 4 days p.i., β-galactosidase activity from KOS22F-infected DRG was 18-fold higher than from KOS18-infected DRG and 3-fold higher than from KOS22R-infected DRG (Fig. 6). At 12 days p.i., however, expression from both KOS22F- and KOS22R-infected DRG were clearly reduced by about 50%. As expected, by 12 days p.i., lacZ gene expression originating from KOS18-infected DRG was not significantly different from the background level. Also, at 28 days p.i., no β-galactosidase activity was observed for KOS18-infected DRG. This has been a consistent observation in our laboratory, i.e., that just pairing the upstream LAP region to the lacZ gene does not result in long-term expression in vivo (9, 22). By contrast, β-galactosidase activity could still be detected at 28 days p.i. for both KOS22F- and KOS22R-infected DRG, although the level of expression was markedly reduced compared to the expression at 4 days p.i.

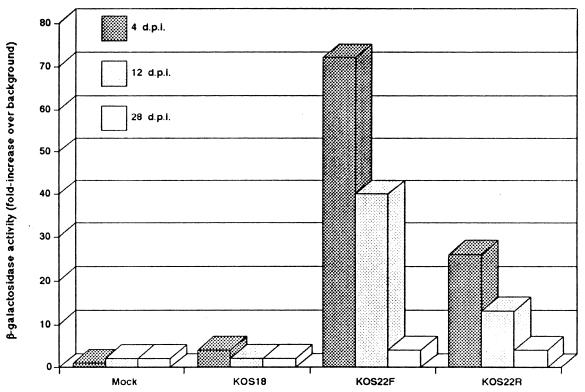

FIG. 6.

β-Galactosidase activity in infected DRG extracts by the quantitative CPRG assay. Swiss Webster mice were inoculated with KOS18, KOS22F, and KOS22R viruses. At the indicated time, cellular extracts from pooled L3, L4, L5, and L6 DRG were produced and used to quantify lacZ gene expression as indicated in Materials and Methods. Values are the mean of the DRG from three mice per time point per virus.

It has been our experience that by 42 days p.i., the level of LAP activity in vivo has essentially reached a plateau. This is true for measuring the levels of the LAT intron, or when the LAP was paired with a long terminal repeat element from a retrovirus to generate long-term expression from a reporter virus (24). To verify that the level of expression of LAP-LTE activity was relatively constant, mouse ganglia latently infected with KOS22F and KOS22R were periodically removed and stained for activity. A level of expression similar to that at 28 days p.i. was also observed in KOS22F- and KOS22R-infected ganglia at 60 days and at 6 months p.i. A picture of the 6-month data is included in Fig. 5G. Thus, the presence of the LTE/intron sequence initially stimulated a very dramatic increase in lacZ gene expression in vivo, which subsequently declined to a lower level. The fact that the neurons remained blue when infected by a virus harboring the LTE/intron sequence could be interpreted in different ways and is discussed below.

It was clear from the data shown in Fig. 5 and 6, that both KOS22F- and KOS22R-infected ganglia expressed far more β-galactosidase protein than did KOS18-infected ganglia. To ensure that the difference in gene expression observed in KOS18-, KOS22F-, and KOS22R-infected ganglia was not due to differences in the abilities of the viruses to grow in vivo, the titers of each virus per time point per mouse were determined. As shown in Table 1, titers of KOS18, KOS22F, and KOS22R ranged from 1.8 × 103 to 3.1 × 103 at 4 days p.i., and as expected, no infectious virus could be recovered at 12 or at 28 days p.i. Thus, the differences in expression observed on days 4 and 12 were not due to differences in viral growth.

TABLE 1.

Virus titers in infected DRG in vivo

| Virus | Titera at:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 days p.i. | 12 days p.i. | 28 days p.i. | |

| None (mock infection) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KOS18 | 1.8 × 103 | 0 | 0 |

| KOS22F | 2.1 × 103 | 0 | 0 |

| KOS22R | 3.1 × 103 | 0 | 0 |

Number of PFU per ganglion.

Immunostaining for β-galactosidase and viral antigens in infected DRG.

Margolis et al. have previously shown that by 4 days p.i. most neurons expressing β-galactosidase from the LAT promoter were in the latent phase of infection and did not express viral antigen, although a small percentage of neurons expressed both β-galactosidase and viral antigens (24). However, we showed earlier in this report that KOS22F virus was able to express β-galactosidase protein in lytically infected cells in culture. Therefore, it was important to know if the cells staining for β-galactosidase at 4 or 12 days p.i. were lytically or latently infected. In the present experiment, DRG infected for 4 days (KOS22F) or for 12 days (KOS22F and KOS22R) were sectioned and double stained using antisera against β-galactosidase and viral antigens. As qualitatively illustrated in Fig. 7, no viral antigen-positive neurons were detected at 12 days after KOS22F or KOS22R infection, confirming our previous data that no infectious virus could be recovered at that time (Table 1). By contrast, at 4 days p.i., KOS22F- and KOS22R-infected ganglia harbored both lytically and latently infected neurons (Fig. 7).

DISCUSSION

During latency, only one transcription unit of the HSV-1 genome is expressed. The LATs are under the control of the LAP, which is constitutively active during the course of the latent state. The reasons why the LAP remains active in latently infected neurons in vivo whereas all the other promoters are shut down are poorly understood. In a previous study, we showed that viruses containing a DNA element located immediately downstream from the transcriptional start site of LAP were able to continue reporter gene transcription during latency whereas viruses lacking this element could not (23). These results were obtained either by in situ staining of or by RNase protection assay on cellular extracts of DRG acutely infected for 4 days.

The initial aim of the present study was to confirm a role of the LTE region in helping the LAP remain active during latency. Using a new approach allowing the expression of a reporter gene situated downstream from a promoter followed by the LTE, we showed that the LTE region contains a surprisingly active enhancer of the LAP. This enhancer activity is bidirectional and increases the activity of the TK promoter as well. The LTE does not increase the activity of the CMV enhancer, but it is not unusual for enhancers to not activate other enhancers.

Another interesting finding in this study is the activity of the LTE in latently infected neurons. Although the LTE is able to increase the activity of the LAP within latently infected neurons, the combined activity of the LAP-LTE substantially decreases between 4 and 28 days p.i. Despite the loss of activity during this time, the level of expression of the LAT-LTE viruses at 28 days is considerably higher than that observed in virus-infected ganglia such as KOS18, which lack the LTE fragment. Therefore, two things are happening in viruses harboring the LTE: there is a high level of expression that is slowly decreased, and the absolute level of expression is higher during latency. An unresolved question is whether these two things are manifestations of the same function or whether they derive from two separate functions. One interpretation of these data is that the LTE has two functions, an enhancer that functions only transiently and a long-term expression function. In this model, the LAP in KOS18 is expressed only during the first week of infection and then is down regulated by some change, perhaps in the viral chromatin structure. This results in a gradual loss of β-galactosidase activity until none is detected by day 28. In KOS22F- and KOS22R-infected neurons, it could be that the LTE loses its enhancer function as a result of the same changes that cause the LAP in KOS18-infected neurons to lose activity. Under this model, the LTE fragment contains a separate, long-term expression function which keeps the LAP active at approximately the same level as at 4 days p.i. In that respect, it would be similar to the LTR that we reported previously, which appears to keep the LAP active throughout latency (24). The fact that KOS22F expresses much more detectable activity than KOS18 at 28 and 42 days and 2 and 6 months shows that the LTE exerts a clear difference in long-term expression. Because the enhancer loses activity and yet viruses containing it remain more active, there is no way at this point to rule out the possibility of the LTE containing a long-term expression function in addition to an enhancer. The only way to rule that out is by a detailed genetic analysis, which is in progress but is beyond the scope of the present work.

An alternative explanation is that the LTE contains only a single function, an enhancer. In this model, when the LAP is down regulated some time during the first week of infection, the LAP-LTE is similarly down regulated. Under this model, the LAT-LTE has no long-term function. Instead, the LAT-LTE construct expresses a detectable level of β-galactosidase protein at 28 days because the initial level of expression is so much higher than that observed for the LAT-lacZ constructs. That is, a 20-fold reduction in expression of the LAP-LTE still results in a level of expression that is detectable at 28 days p.i. whereas a 20-fold reduction in expression in KOS18-infected neurons results in loss of detectable activity.

At present, we have not distinguished between these two possibilities. In either case, the activity of this enhancer is potentially significant. Recently, authors have shown that there is a latency establishment defect in mouse trigeminal ganglia for viruses with the LAP deleted (35). Another group demonstrated that LAP mutants appear to grow better in neurons in vivo than do wild-type viruses (16). Both of these studies suggested a potential role for the LAT intron in opposing ICP0 function. We have previously shown by transient-expression assays that the LAT intron is capable of blocking ICP0 protein function (13). The very substantial increase in activity it contributes to the LAP comes at a time when the virus is capable of forming either a lytic or a productive infection of the neuron. An enormous increase in transcription by the LAP would result in a very large increase in the concentration of the LAT intron, an RNA molecule that is antisense to the ICP0 mRNA. Thus, the enhancer is in theory capable of exerting an influence on the establishment properties of the virus, perhaps giving the virus a push toward the establishment of a latent infection by increasing the inhibition of ICP0 gene expression.

In these studies, we also observed what appears to be a lytic promoter activity within the LTE/intron in the forward direction. Since the LAP2 is active during a lytic but not a latent infection (5), it is conceivable that the increased expression observed by lytic infection with virus KOS22F may be due to LAP2 activity. If it is due to LAP2, the increased β-galactosidase protein expression may be aided by the splicing cassette, in that a cryptic splice donor may remove start codons between LAP2 and the splice acceptor site. An alternative explanation for the lytic activity of KOS22F and not KOS22R is the presence near the 3′ end of the LTE of a TATA sequence. This element could be transactivated by ICP4 or ICP0, and in the reverse orientation in KOS22R this element would be even further from the splice acceptor site than would LAP2. In either case, there is no evidence that either LAP2 or the TATA element is expressed during latency. Thus, the significance of the lytic activity of KOS22F is doubtful.

There is some evidence in the literature to support a role for the region as being an enhancer as well as playing a role in the lytic cycle. Previous work has shown that motifs in the LAP2 region of HSV-1 were able to bind HMG1(Y) proteins, thus facilitating the binding of Sp1 transcription factors (15). HMG1(Y) proteins do not possess an intrinsic transactivator activity. However, they are known to bind DNA and to alter the DNA structure (12). This DNA-bending activity is thought to remodel the promoter region so that it becomes more active (31). In our model, binding of both HMG1(Y) and Sp1 factors to the LAP2 region (corresponding approximately to the first half of our LTE region) would lead to remodeling of LAP1, thus increasing its activity. As expected, this type of enhancer would be independent of its orientation and would not be specific to a promoter or to a cell line since cellular extracts from both HeLa cells and a neuroblastoma cell line (B103) were able to protect the same region in LAP2 (15).

Recent studies have also shown that HMG1(Y) proteins served as a coactivators of the HSV-1 ICP4 transcriptional factor in vitro (4, 26), leading to augmentation of the ICP4 activity. Thus, it is possible that binding of HMG1(Y) proteins within LAP2 would recruit the ICP4 transactivator when it is synthesized during productive infection. The LAP2 region would therefore become a very efficient promoter in the course of the lytic cycle, but the role of this region would be mainly an enhancer activity for LAP1 during latency.

Finally, we note that some recombinant viruses that are deleted in the LTE region are also inactive for reactivation from latency. Both the StyI mutant used by Fraser and colleagues (18a) and the Δ348 virus used by Bloom et al. (3) are defective in reactivation from latency. Both of the deletions are in the RNA sequence 5′ of the intron, within the LTE region, and in both cases it has been difficult to ascribe a molecular reason for the effect of the deletion on reactivation. It will be interesting to determine if the cause of the failure of these viruses to reactivate may be due to the absence of an enhancer function.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We especially thank David Leib, Washington University, St. Louis, Mo., for generously providing KOS dl1.8. We also thank Adam Weidera for excellent technical support.

These experiments were supported by NIH grants AI28338 to L.T.F. and Ey10008 to T.M.

REFERENCES

- 1.Batchelor A H, O'Hare P. Regulation and cell-type-specific activity of a promoter located upstream of the latency-associated transcript of herpes simplex virus type 1. J Virol. 1990;64:3269–3279. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.7.3269-3279.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Batchelor A H, Wilcox K W, O'Hare P. Binding and repression of the latency-associated promoter of herpes simplex virus by the immediate early 175K protein. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:753–767. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-4-753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bloom D C, Hill J M, Devi-Rao G, Wagner E K, Feldman L T, Stevens J G. A 348-base-pair region in the latency-associated transcript facilitates herpes simplex virus type 1 reactivation. J Virol. 1996;70:2449–2459. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.4.2449-2459.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carrozza M J, DeLuca N. The high-mobility-group protein 1 is a coactivator of herpes simplex virus ICP4 in vitro. J Virol. 1998;72:6752–6757. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.8.6752-6757.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen X, Schmidt M C, Goins W F, Glorioso J C. Two herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-active promoters differ in their contributions to latency-associated transcript expression during lytic and latent infections. J Virol. 1995;69:7899–7908. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.7899-7908.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Croen K D, Ostrove J M, Dragovic L J, Smialek J E, Straus S E. Latent herpes simplex virus in human trigeminal ganglia. Detection of an immediate early gene “anti-sense” transcript by in situ hybridization. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1427–1432. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198712033172302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deatly A M, Spivack J G, Lavi E, Fraser N W. RNA from an immediate early region of the type 1 herpes simplex virus genome is present in the trigeminal ganglia of latently infected mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:3204–3208. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.10.3204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Devi-Rao G B, Goodart S A, Hecht L M, Rochford R, Rice M K, Wagner E K. Relationship between polyadenylated and nonpolyadenylated herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcripts. J Virol. 1991;65:2179–2190. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.5.2179-2190.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dobson A T, Margolis T P, Gomes W A, Feldman L T. In vivo deletion analysis of the herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcript promoter. J Virol. 1995;69:2264–2270. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2264-2270.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dobson A T, Margolis T P, Sedarati F, Stevens J G, Feldman L T. A latent, nonpathogenic HSV-1-derived vector stably expresses beta-galactosidase in mouse neurons. Neuron. 1990;5:353–360. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90171-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dobson A T, Sederati F, Devi-Rao G, Flanagan W M, Farrell M J, Stevens J G, Wagner E K, Feldman L T. Identification of the latency-associated transcript promoter by expression of rabbit beta-globin mRNA in mouse sensory nerve ganglia latently infected with a recombinant herpes simplex virus. J Virol. 1989;63:3844–3851. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.9.3844-3851.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Falvo J V, Thanos D, Maniatis T. Reversal of intrinsic DNA bends in the IFN beta gene enhancer by transcription factors and the architectural protein HMG I(Y) Cell. 1995;83:1101–1111. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90137-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farrell M J, Dobson A T, Feldman L T. Herpes simplex virus latency-associated transcript is a stable intron. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:790–794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.3.790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farrell M J, Margolis T P, Gomes W A, Feldman L T. Effect of the transcription start region of the herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcript promoter on expression of productively infected neurons in vivo. J Virol. 1994;68:5337–5343. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.5337-5343.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.French S W, Schmidt M C, Glorioso J C. Involvement of a high-mobility-group protein in the transcriptional activity of herpes simplex virus latency-active promoter 2. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5393–5399. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.10.5393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garber D A, Schaffer P A, Knipe D M. A LAT-associated function reduces productive-cycle gene expression during acute infection of murine sensory neurons with herpes simplex virus type 1. J Virol. 1997;71:5885–5893. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.5885-5893.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goins W F, Sternberg L R, Croen K D, Krause P R, Hendricks R L, Fink D J, Straus S E, Levine M, Glorioso J C. A novel latency-active promoter is contained within the herpes simplex virus type 1 UL flanking repeats. J Virol. 1994;68:2239–2252. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.4.2239-2252.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hill J M, Sedarati F, Javier R T, Wagner E K, Stevens J G. Herpes simplex virus latent phase transcription facilitates in vivo reactivation. Virology. 1990;174:117–125. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18a.Hill J M, Maggioncalda J B, Garza H H, Jr, Su Y H, Fraser N W, Block T M. In vivo epinephrine reactivation of ocular herpes simplex virus type 1 in the rabbit is correlated to a 370-base-pair region located between the promoter and the 5′ end of the 2.0-kilobase latency-associated transcript. J Virol. 1996;70:7270–7274. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.7270-7274.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ho D Y, Mocarski E S. Herpes simplex virus latent RNA (LAT) is not required for latent infection in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:7596–7600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.19.7596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Javier R T, Stevens J G, Dissette V B, Wagner E K. A herpes simplex virus transcript abundant in latently infected neurons is dispensable for establishment of the latent state. Virology. 1988;166:254–257. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90169-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lachman R H, Efstathiou S. Utilization of the herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated regulatory region to drive stable reporter gene expression in the nervous system. J Virol. 1997;71:3197–3207. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.3197-3207.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leib D A, Bogard C L, Kosz-Vnenchak M, Hicks K A, Coen D M, Knipe D M, Schaffer P A. A deletion mutant of the latency-associated transcript of herpes simplex virus type 1 reactivates from the latent state with reduced frequency. J Virol. 1989;63:2893–2900. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.7.2893-2900.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lokensgard J R, Berthomme H, Feldman L T. The latency-associated promoter of herpes simplex virus type 1 requires a region downstream of the transcription start site for long-term expression during latency. J Virol. 1997;71:6714–6719. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6714-6719.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Margolis T P, Sedarati F, Dobson A T, Feldman L T, Stevens J G. Pathways of viral gene expression during acute neuronal infection with HSV-1. Virology. 1992;189:150–160. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90690-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitchell W J, Steiner I, Brown S M, MacLean A R, Subak-Sharpe J H, Fraser N W. A herpes simplex virus type 1 variant, deleted in the promoter region of the latency-associated transcripts, does not produce any detectable minor RNA species during latency in the mouse trigeminal ganglion. J Gen Virol. 1990;71:953–957. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-4-953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Panagiotidis C A, Silverstein S J. The host-cell architectural protein HMG I(Y) modulates binding of herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP4 to its cognate promoter. Virology. 1999;256:64–74. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perng G, Ghiasi H, Slavina S M, Nesburn A B, Wechsler S. The spontaneous reactivation function of the herpes simplex virus type 1 LAT gene resides completely within the first 1.5 kilobases of the 8.3-kilobase primary transcript. J Virol. 1996;70:976–984. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.976-984.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rock D L, Nesburn A B, Ghiasi H, Ong J, Lewis T L, Lokensgard J R, Wechsler S L. Detection of latency-related viral RNAs in trigeminal ganglia of rabbits latently infected with herpes simplex virus type 1. J Virol. 1987;61:3820–3826. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.12.3820-3826.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roizman B, Sears A E. An inquiry into the mechanisms of herpes simplex virus latency. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1987;41:543–571. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.41.100187.002551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sawtell N M, Thompson R L. Herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcription unit promotes anatomical site-dependent establishment and reactivation from latency. J Virol. 1992;66:2157–2169. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.2157-2169.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shykind B M, Kim J, Sharp P A. Activation of the TFIID-TFIIA complex with HMG-2. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1354–1365. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.11.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spivack J G, Fraser N W. Detection of herpes simplex virus type 1 transcripts during latent infection in mice. J Virol. 1987;61:3841–3847. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.12.3841-3847.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stevens J G, Wagner E K, Devi-Rao G B, Cook M L, Feldman L T. RNA complementary to a herpesvirus alpha gene mRNA is prominent in latently infected neurons. Science. 1987;235:1056–1059. doi: 10.1126/science.2434993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thompson R L, Sawtell N M. The herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcript gene regulates the establishment of latency. J Virol. 1997;71:5432–5440. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5432-5440.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wagner E K, Devi-Rao G, Feldman L T, Dobson A T, Zhang Y F, Flanagan W M, Stevens J G. Physical characterization of the herpes simplex virus latency-associated transcript in neurons. J Virol. 1988;62:1194–1202. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.4.1194-1202.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wechsler S L, Nesburn A B, Watson R, Slanina S M, Ghiasi H. Fine mapping of the latency-related gene of herpes simplex virus type 1: alternative splicing produces distinct latency-related RNAs containing open reading frames. J Virol. 1988;62:4051–4058. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.11.4051-4058.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zwaagstra J, Ghiasi H, Nesburn A B, Wechsler S L. In vitro promoter activity associated with the latency-associated transcript gene of herpes simplex virus type 1. J Gen Virol. 1989;70:2163–2169. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-70-8-2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zwaagstra J C, Ghiasi H, Slanina S M, Nesburn A B, Wheatley S C, Lillycrop K, Wood J, Latchman D S, Patel K, Wechsler S L. Activity of herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcript (LAT) promoter in neuron-derived cells: evidence for neuron specificity and for a large LAT transcript. J Virol. 1990;64:5019–5028. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.10.5019-5028.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]