Abstract

In eukaryotes, crossovers in mitotic cells can have deleterious consequences and therefore must be suppressed. Mutations in BLM give rise to Bloom syndrome, a disease that is characterized by an elevated rate of crossovers and increased cancer susceptibility. However, simple eukaryotes such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae have multiple pathways for suppressing crossovers, suggesting that mammals also have multiple pathways for controlling crossovers in their mitotic cells. We show here that in mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells, mutations in either the Bloom syndrome homologue (Blm) or the Recql5 genes result in a significant increase in the frequency of sister chromatid exchange (SCE), whereas deleting both Blm and Recql5 lead to an even higher frequency of SCE. These data indicate that Blm and Recql5 have nonredundant roles in suppressing crossovers in mouse ES cells. Furthermore, we show that mouse embryonic fibroblasts derived from Recql5 knockout mice also exhibit a significantly increased frequency of SCE compared with the corresponding wild-type control. Thus, this study identifies a previously unknown Recql5-dependent, Blm-independent pathway for suppressing crossovers during mitosis in mice.

Homologous recombination is a basic molecular process that operates in both meiotic and mitotic cells in mammals. Meiotic recombination is necessary for the proper segregation of homologous chromosomes between daughter cells and for creating genetic diversity through the random mixing of the parental chromosomes and allele shuffling (23). Mitotic recombination facilitates the high-fidelity, nonmutagenic repair of DNA double-stranded breaks and damaged DNA replication forks (7, 21, 34), if the repair is mediated by gene conversion or by crossovers between identical sister chromatids. However, other types of crossovers can be mutagenic or oncogenic. For example, a reciprocal exchange between two nonhomologous chromosomes can lead to translocation, while crossovers between two homologous chromosomes can result in somatic loss of heterozygosity (LOH) (2). In mammals, translocations can lead to the activation of oncogenes or inactivation of tumor suppressor genes, while somatic loss of heterozygosity can convert an otherwise inconsequential heterozygous mutation in a tumor suppressor gene into a complete loss-of-function status (31, 32). In addition, reciprocal exchanges that result from intrachromosomal recombination can lead to deletions or inversions, which can also result in the activation of oncogenes or inactivation of tumor suppressor genes. Thus, while mitotic recombination plays critical roles in the repair of double-stranded breaks and damaged replication forks, crossovers resulting from these repair events can lead to oncogenic DNA rearrangements, increasing the risk of developing cancer (56). Therefore, in mammalian cells, mitotic recombination is highly regulated to favor gene conversion and minimize crossovers (27, 42, 48).

The mechanisms that regulate mitotic recombination remain poorly understood. In Saccharomyces serevisiae, two DNA helicases, Sgs1p and Srs2p, are involved in different pathways that suppress crossovers (26, 33, 55). Sgs1p is a member of the RecQ family of DNA helicases (59). In mammals, homologues of the Bloom syndrome (BLM) helicase (9) have also been shown to play important roles in regulating mitotic recombination (37, 46, 54, 62). RecQ DNA helicases belong to a family of evolutionarily conserved enzymes that have been found in many organisms examined to date. The first RecQ gene was identified in Escherichia coli as a nonessential gene involved in the RecF pathway (44). The yeast RecQ homologue, SGS1, was identified in a genetic screen of suppressors for the slow-growth phenotype of top3 mutant strains in S. cerevisiae (13). The sgs1 mutant exhibits a range of phenotypes, including slow growth, hyperrecombination, and chromosome missegregation (59, 60). The corresponding rqh1 mutant in Schizosaccharomyces pombe also exhibits similar phenotypes (43, 53). Unlike unicellular organisms, which have a single RecQ DNA helicase gene, both the mouse and humans have five genes (Recql, Blm, Wrn, Recql4, and Recql5 for mice, and RECQL, BLM, WRN, RECQL4, and RECQL5 for humans) encoding multiple RecQ homologues (9, 24, 29, 47, 50, 63). Mutations in BLM, WRN, and RECQL4 give rise to three distinct syndromes: Bloom (9), Werner (63), and Rothmund-Thomson (30) syndromes, respectively.

Bloom syndrome is characterized by elevated frequencies of both sister chromatid exchange (SCE) and multiradial structures (4, 15) and increased susceptibility to a wide spectrum of malignancies (13). Likewise, cells from Blm knockout mice also exhibit elevated frequencies of SCE (5, 37, 41) and multiradial structure (41) and increased susceptibility to a wide variety of cancers (18, 37, 41). In contrast, cells from Werner and Rothmund-Thomson syndrome patients do not exhibit the SCE phenotype. Although patients of these two syndromes are also cancer prone, they tend to develop specific types of cancers. These observations have indicated that both human BLM and its murine homologue play important roles in the suppression of crossovers in mitotic cells and have suggested that elevated crossovers in mitotic cells represent a common contributing factor in mammalian carcinogenesis.

The underlying mechanisms by which RecQ DNA helicases regulate mitotic recombination have not been well defined. However, it is clear that many RecQ helicases can recognize Holliday junctions or Holliday junction-like structures and unwind double-stranded DNA in a 3′ to 5′ direction (6, 14, 28). Genetic studies in yeast have implicated type IA topoisomerases in the RecQ helicase-mediated regulation of recombination (13). Biochemical studies have also shown that human BLM interacts with TOPOIIIα, a type IA topoisomerase (25, 62); this interaction enhances the helicase activity of BLM (62). Therefore, it appears that the interaction between RecQ helicases and type IA topoisomerases plays an important role in the RecQ helicase-mediated regulation of mitotic recombination. Recently, it was shown that human RECQL5β physically interacts with both TOPOIIIα and IIIβ (51), making it the only other human RecQ homologue (other than BLM) that physically interacts with type IA topoisomerases. This observation has led to the speculation that BLM and RECQL5β might have similar roles in regulating mitotic recombination. In an attempt to address this question, Wang and colleagues deleted the chicken RECQL5 homologue in DT40 cells. They detected no effect of RECQL5 deletion on the frequency of spontaneous SCE. However, the same RECQL5 deletion in a BLM−/− background increased the frequency of SCE. These observations led them to conclude that RECQL5 suppresses SCE but only under BLM function-impaired conditions (57).

Here, we report that inactivation of the Recql5 gene alone is sufficient to cause a significant increase in the frequency of spontaneous SCE in both mouse ES cells and in differentiated mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF). Furthermore, deleting both Blm and Recql5 in mouse ES cells resulted in an even higher frequency of SCE than mutating either one of these two genes alone. These results demonstrate that Recql5, like Blm, plays an essential role in the suppression of crossovers and it does so through a pathway that is distinct from that of Blm.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of Recql5 targeting vectors.

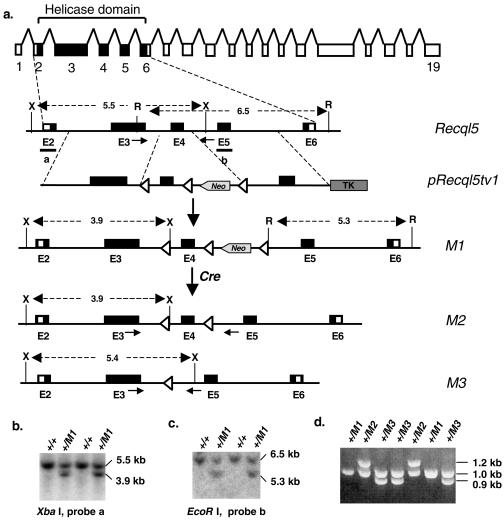

The recombineering technique (35, 64) was used to construct the Recql5 targeting vectors. First, a 2.4-kb genomic sequence was amplified by PCR and used as a probe to screen the RPCI-22 129S6/SvEv bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) library. The primers used were Q5e3f (5′-ATGGCGCGCCGAGATGGCAGCTTCAGCCTCCTTCCA-3′) and Q5e5r (5′-ATGGCGCGCCCGGACATTAGCTTTGTCTACTCCCAT-3′). Clone RPCI-22-51D24 was found to contain the entire Recql5 gene by PCR and Southern blot analysis (data not shown) and was chosen as the starting material for constructing Recql5 targeting vectors. Subsequently, a targeting strategy and the first targeting vector were designed (Fig. 1a). In this strategy, a 7.3-kb genomic fragment was used to construct a targeting vector, with which a conditional Recql5 knockout allele was created. In this allele, exon 4 of Recql5 was replaced by a loxP-exon4-loxP-PGKNeo-loxP cassette. To construct this vector, an RPCI-22-51D24 BAC clone was introduced into DY380 cells by electroporation. In the meantime, a retrieval vector, pQ5RevTK, was constructed. In this vector, two small genomic fragments, 400 bp each and corresponding to the 5′ and 3′ ends of the 7.3-kb genomic fragment, respectively, were amplified by PCR and cloned into pMc1TK. The primers used were as follows: Q5RevP1, 5′-GCGTGATCTAGAAACCCCAAAAAGATGATGAGG-3′; Q5RevP2, 5′-GCGGAATTCGCTAGCATTCCTGAGGTAAGACA-3′; Q5RevP3, 5′-GCGGAATTCGGATCCAGTATTTGTCCTGACCTC-3′; and Q5RevP4, 5′-CGTCGAGCGGCCGCACTCCATAGTGGGCCAG-3′. These two genomic fragments provided the homologies for the recombination between the retrieval vector and the BAC clone, whereas the Mc1TK cassette was used as a negative selection marker in the gene targeting experiments in mouse ES cells. The retrieval vector was linearized by BamHI and electroporated into DY380 cells containing the RPCI-22-51D24 BAC clone. Induced recombination inside the DY380 cells resulted in the retrieval of a 7.3-kb genomic fragment from the BAC clone onto the retrieval vector, generating an intermediate vector, pQ5TK. Then, a modification cassette was created. First, a loxP-exon4-loxP-PGKNeo-loxP cassette was constructed. In the meantime, two small genomic fragments, 400 bp each and corresponding to the 5′ and 3′ ends of exon 4, respectively, were amplified by PCR and cloned into pBluescript (Stratagene). The primers used were Q5BMP1, 5′-CGGAATTCCGGCGCGCCCTTGGACAGAAGGCTGAGAACGGG-3′; Q5BMP2, 5′-GCTCTAGAGATAACTTCGTATAATGTATGCTATACGAAGTTATCAGCCCACTCACTAGAGCACAGCA-3′; Q5BMP3, 5′-GCTCTAGAGCTGATTGTACCACCCTTCCCCTAG-3′; and Q5BMP4, 5′-GTGGCGCGCCAAGGGTACCTGTTCTGTTGTGATCCA-3′. Insertion of the loxP-exon4-loxP-PGKNeo-loxP cassette between the two genomic fragments then gave rise to the plasmid pQ5mod containing the 5′arm-loxP-exon4-loxP-PGKNeo-loxP-3′arm modification cassette. This cassette was then excised from pQ5mod and introduced into DY380 cells together with pQ5TK. Induced recombination between the homologous sequences in pQ5TK and the modification cassette led to the replacement of exon 4 with the loxP-exon4-loxP-PGKNeo-loxP cassette and gave rise to the first targeting vector, pRecql5tv1 (Fig. 1a). This vector was partially sequenced to confirm that no unintended mutations were created in exon 4 during these manipulations. Two other targeting vectors, pRecql5tv2 (Fig. 2a) and pRecql5tv3 (information available upon request) were generated by replacing the PGKNeo cassette of pRecql5tv1 with a PGKHprt minigene cassette and a PGKPuro cassette, respectively.

FIG. 1.

Gene targeting at the Recql5 locus. (a) The targeting strategy to delete exon 4 of the Recql5 gene. The 19 exons encoding Recql5 beta are shown as boxes, and the sequences encoding the conserved helicase domain are indicated by black boxes. With this strategy, a correct targeting event replaces exon 4 with a LoxP-exon4-LoxP-PGKNeo-LoxP cassette, giving rise to the first Recql5 targeted allele, the M1 allele. Subsequently, a Cre-mediated deletion of sequences between the two loxP sites (open triangles) flanking the Neo cassette leads to a conditional Recql5 knockout allele, the M2 allele, in which exon 4 is flanked by a pair of loxP sites. Alternatively, a Cre-mediated deletion of both exon 4 and the Neo cassette results in a true Recql5 knockout allele, the M3 allele. Note the opposite directions of transcriptions for PGKNeo and Recql5. Neo, neomycin phosphotransferase gene; TK, thymidine kinase gene; X, XbaI; R, EcoR I. (b) Identifications of ES clones with correctly targeted events within the 5′ homology by Southern using probe a. (c) Identification of ES clones with correctly targeted events within the 3′ homology by Southern using probe b. (d) Identification of ES cell clones containing either the M2 allele or the M3 allele by PCR. The primers used in the PCR are shown in panel a as short arrows.

FIG. 2.

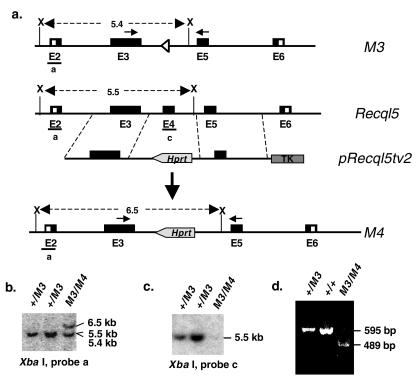

Generation of Recql5−/− ES cells. (a) A gene targeting strategy to replace exon 4 with a PGKHprt (Hprt) cassette. This strategy can be used to generate a true Recql5 knockout allele, the M4 allele, in a single targeting experiment. Specifically, the targeting of the remaining wild-type Recql5 allele in heterozygous Recql5 knockout ES cells containing a M3 allele is shown. This resulted in the generation of homozygous Recql5 knockout (Recql5−/−) ES cells. Note the opposite directions of transcription for the Hprt cassette and Recql5. X, XbaI. (b) Identification of ES clones in which both Recql5 alleles have been targeted. Clones in which the remaining wild-type Recql5 allele was correctly targeted within the 5′ homology were identified by Southern using probe a. (c) Confirmation of the complete deletion of exon 4 in clones identified in panel b by Southern with an exon 4-specific probe (probe c). (d) Results of an RT-PCR experiment showing the absence of the expected 595-bp product from the normal Recql5 mRNA and the presence of a 489-bp product from an aberrant transcript in a homozygous Recql5 knockout (M3/M4) ES cell clone. The primers used in the RT-PCRs are indicated in panel a as short arrows.

Gene targeting in mouse ES cells.

Gene targeting experiments in the AB2.2 ES cells were conducted as described previously (37). For all the clones used in experiments, correct targeting events were verified by Southern hybridization. All ES clones were subsequently reseeded at low densities to obtain single-cell-derived clonal lines.

Mouse work.

Two ES clones heterozygous for the M2 Recql5 conditional knockout allele (+/M2) were used to generate chimeras and to obtain germ line transmission of the conditional knockout allele as previously described (38). Zp3-Cre transgenic mice (8) were used to excise exon 4 in the conditional allele of Recql5 in mouse oocytes to generate heterozygous Recql5 knockout mice (+/M3). Recql5-targeted alleles were maintained in an F2 mixed genetic background between 129/SvEv and C57BL/6J inbred strains.

Cell culture and analyses.

ES cells were cultured in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (Invitrogen) containing 15% fetal bovine serum as previously described (38). For cell growth analysis, 104 cells were plated in each well of six-well feeder plates. The number of cells in each well was counted 48 h after plating and every 24 h afterwards. Standard colonogenic survival assays were used to assess sensitivities to gamma radiation. Briefly, ES cells were trypsinized into single-cell suspensions and then exposed to different doses (0 to 10 Gy) of radiation from a Cs-137 irradiator. After irradiation, cells were plated onto six-well feeder plates at 104 cells/well to allow formation of single-cell-derived colonies. Eight days after plating, colonies that were at least 1 mm in diameter were counted. Experiments were carried out in triplicate and repeated twice. In each experiment, appropriate controls for evaluating plating efficiencies of individual cell lines were also included. Statistical analysis was performed using Prism software (GraphPad Software).

RT-PCR.

Total RNA was isolated from ES cells grown in gelatinized plates using TRIzol (Invitrogen) according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer. All reverse transcription-PCRs (RT-PCRs) were carried out using Superscript II RT/Platinum Taq mixture (Invitrogen). Primer pair Q5e3f1 (5′-ATGGCGCGCCCGGACATTAGCTTTGTCTACTCCCAT-3′)-Q5e5r1 (5′-ATGGCGCGCCCGGACATTAGCTTTGTCTACTCCCAT-3′) was used in studying the expression of wild-type and targeted Reclq5 alleles. These primers are specific to exons 3 and 5, respectively. To quantify the expression of Recql5 in BAC-rescued Recql5 knockout ES cells by quantitative RT-PCR, primer pair Q5e3f2 (5′-GGCAATCTGAGGGACTTCTGCCT-3′)-Q5e4r1 (5′-CTGCGTGGTAAGCCTTGGCGTTC-3′) was used. Q5e4r1 is specific to exon 4, which is deleted in the Recql5 knockout allele. Thus, RT-PCR using this primer pair results in the amplification of transcripts from only the wild-type Recql5 and not the knockout alleles. The primers used for amplifying the internal control Gapdh are Gapdh.f1 (5′-GTGCTGAGTATGTCGTGGAGT-3′) and Gapdh.r1 (5′-CACACACCCATCACAAACATG-3′). Semiquantitative, low-cycle-number RT-PCR amplification with 32P-labeled primers (40) was used to quantify the expression of Recql5 transcripts. Specifically, for each RT-PCR, first-strand synthesis of cDNA was carried out using 1 μg of the total RNA. After that, 32P-labeled 5′ primers were added, and the PCRs were allowed to proceed for various numbers of cycles which were expected to be within the linear range of target amplification according to the results of trial experiments. The RT-PCR products were then fractionated on a nondenatured polyacrylamide gel. After electrophoresis, the gel was dried and analyzed with a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). Data from the RT-PCRs within the linear range were used to calculate the relative levels of Recql5 expression.

SCE analysis.

The SCE analysis was carried out using a classical 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU)-labeling protocol (17) with a minor modification: the concentrations of BrdU were reduced to 1.5 μg/ml for ES cells and 3 μg/ml for MEF cells, respectively. Also, to minimize the variations between experiments, all cell lines involved in the large-scale SCE analyses were processed simultaneously in a single experiment. Sister chromatids were visualized by staining with acridine orange (Sigma) solution (0.1 mg/ml). Specifically, to count the number of SCE, images of metaphase spreads were captured, and SCE of individual cell lines were scored blind. Statistical analysis was performed with Prism software (GraphPad Software).

RESULTS

Inactivation of Recql5 in mouse ES cells by gene targeting.

Human RECQL5 has been shown to express three different transcripts encoding three RecQ DNA helicase isoforms (α, β, and γ) (29, 51). The three isoforms share the conserved helicase domain encoded by exons 2 to 6 (45), but only RECQL5β, the longest isoform, contains a nuclear localization signal. The mouse Recql5 gene is very similar to its human homologue; however, its expression has not been well characterized. Thus, to ensure the functional inactivation of the mouse Recql5 gene, we decided to delete its 106-bp exon 4 to create a frameshift mutation at codon 260. Furthermore, in anticipation of the possibility that the deletion of Recql5 might lead to lethality, we created a conditional Recql5 knockout allele. Specifically, we replaced exon 4 of Recql5 with a loxP-exon4-loxP-PGKNeo-loxP cassette to obtain a primary Recql5-targeted allele, the M1 allele (Fig. 1a). Following that, a conditional knockout allele (the M2 allele) and a true knockout allele (the M3 allele) were derived from this M1 allele by Cre-mediated deletions (Fig. 1a). ES cell clones carrying the desirable Recql5 alleles were identified either by Southern (Fig. 1b and c) or by PCR (Fig. 1d) analysis. Two targeted ES cell clones with the M2 conditional knockout allele were used to generate conditional knockout mice (see below and Fig. 7). In the meantime, two clones with the M3 allele were used to generate homozygous Recql5 knockout ES cells by deletion of the remaining wild-type Recql5 allele with a different targeting vector, pRecql5tv2 (Fig. 2a). This vector was designed to replace exon 4 of Recql5 with a PGKHprt minigene cassette, leading to another Recql5 knockout allele, the M4 allele (Fig. 2a). Correctly targeted ES cell clones were identified by Southern analysis (Fig. 2b and c).

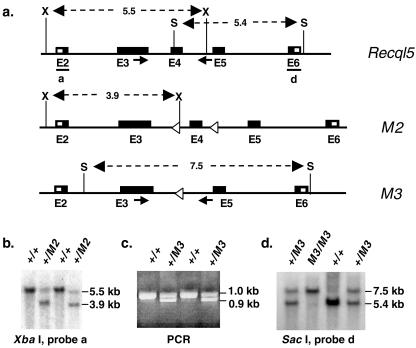

FIG. 7.

Generation of Recql5 knockout mice. (a) A schematic illustration of portions of the wild-type Recql5 allele, the M2 conditional knockout allele, and the M3 knockout allele. Regions between exons 2 and 6 are shown. X, XbaI; S, SacI. (b) Identification of mice carrying the M2 allele (+/M2) by Southern analysis using probe a. (c) Identification of mice carrying the M3 allele (+/M3) by PCR. (d) Identification of homozygous Recql5 knockout (M3/M3) mice among the progeny of a cross between heterozygous knockout (+/M3) mice by Southern analysis by using probe d. The positions of the primers (arrows) used in PCRs are indicated in panel a.

RT-PCR analysis showed that the homozygous Recql5 knockout (M3/M4) ES cells no longer express the wild-type Recql5 mRNA, but they do express an aberrant transcript (Fig. 2d). Sequencing analysis showed that this aberrant transcript originated from the M3 allele and is expected to encode a truncated polypeptide of 260 amino acids consisting of the first 259 amino acids of the 981-amino-acid Recql5β helicase (45) plus an additional alanine residue. Thus, this M3 allele is expected to produce either an N-terminal truncated polypeptide without any discernible domain or no protein product at all because of a nonsense-mediated decay. Therefore, this allele likely represents a null allele without any dominant negative effect. These data also indicate that the M4 allele does not express any detectable transcripts. Thus, these Recql5 knockout (M3/M4) ES cells represent Recql5 null ES cells. They are referred to as Recql5−/− ES cells hereafter.

Recql5−/− ES cells have an elevated frequency of SCE and an increased incidence of multiradial structures.

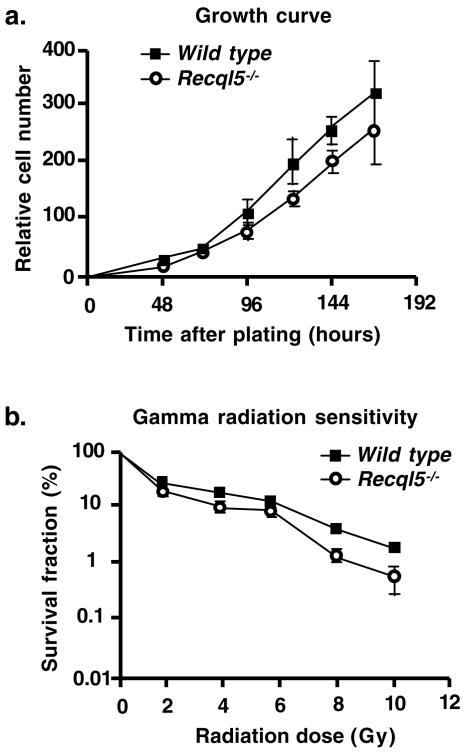

Recql5−/− ES cells have growth characteristics similar to those of their parental wild-type ES cells (Fig. 3a and data not shown). The major objective of this study was to investigate whether Recql5 plays a role in suppressing crossovers in mitotic cells. Deletion of a gene can affect the frequency of crossovers by affecting either the recombination repair machinery or the regulation of recombination. Thus, we first assessed the repair capacity of the recombination repair machinery in Recql5−/− ES cells by comparing their sensitivity to gamma irradiation with that of its parental cell line. The result showed that Recql5−/− ES cells and its parental line have similar sensitivities to gamma irradiation (Fig. 3b), indicating that deletion of Recql5 does not significantly impair the recombination repair capacity in mouse ES cells.

FIG. 3.

Growth characteristics and responses to gamma radiation in mouse ES cells. (a) Growth curves of wild-type and Recql5−/− ES cells. (b) Sensitivity to gamma radiation. The results of clonogenic survival assay experiments. Error bars represent standard deviations.

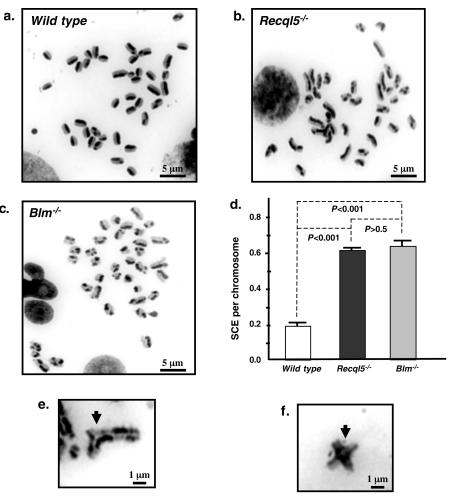

To investigate whether Recql5 is involved in the suppression of crossovers in mouse ES cells, we first compared the frequencies of SCE among wild-type, Recql5+/−, and Recql5−/− ES cells. Initially, 20 metaphase spreads derived from wild-type, two Recql5+/−, and two Recql5−/− ES cell lines were examined. This experiment showed that wild-type and Recql5+/− ES cells have similar SCE frequencies. However, the two Recql5−/− ES cell lines have similarly higher frequencies of SCE that are about three times higher than those of wild-type and Recql5+/− ES cells (data not shown). Subsequently, we conducted a large-scale experiment to compare the frequencies of SCE in wild-type and Recql5−/− ES cells. As a positive control, we also included Blm−/− ES cells (19, 37) in this experiment. Specifically, the blm (M3-M4) ES cells (19) were used. These ES cells express 12% of the wild-type Blm protein from the M3 hypomorphic allele (41). These were also the cells used to generate Blm Recql5 double-knockout ES cells (see below). The results showed that Recql5−/− ES cells indeed have a frequency of spontaneous SCE that is significantly higher than that of the wild-type control (P < 0.001) but is similar to that in Blm−/− ES cells (Fig. 4a to d and Table 1). These data clearly indicate that the deletion of the Recql5 gene resulted in a significant increase in the rate of crossovers between sister chromatids.

FIG. 4.

Spontaneous crossovers in mouse ES cells. (a to c) Representative metaphase spreads from wild-type, Recql5−/−, and Blm−/− cells showing SCE. (d) The results of statistical analysis of SCE frequencies. Average number of SCE per chromosome in wild type, Recql5−/−, and Blm−/− cells were calculated and compared. Error bars indicate standard errors of the mean, and P values were calculated by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with posttest. (e to f) Two examples of multiradial structures (indicated by arrows) observed in Recql5−/− cells, indicative of interchromosomal exchanges.

TABLE 1.

Spontaneous SCE in mouse ES cellsa

| No. of SCE events per chromosome | Percentage of events in:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | Recql5−/− | Blm−/− | Recql5−/−Blm−/− | |

| 0 | 82.0 | 59.6 | 54.6 | 42.4 |

| 1 | 16.4 | 25.5 | 32.1 | 29.3 |

| 2 | 1.52 | 10.7 | 11.0 | 19.2 |

| 3 | 0.13 | 3.19 | 2.10 | 6.47 |

| 4 | 0 | 0.69 | 0.09 | 1.31 |

| ≥5 | 0 | 0.27 | 0.09 | 1.26 |

Total chromosomes were derived from 56, 80, 30, and 48 metaphase spreads of the wild type, Recql5−/−, Blm−/−, and Blm−/− Recql5−/− ES cells, respectively. Total chromosomes were 2,238 for the wild type, 2,913 for Recql5−/−, 1,142 for Blm−/−, and 1,902 for Blm−/−Recql5−/− ES cells. The total number of SCE events was 251 for the wild type, 1,769 for Recql5−/−, 829 for Blm−/−, and 1,884 for Blm−/−Recql5−/− ES cells. The average number of SCEs per chromosome (values in parentheses are standard errors) was 0.198 (0.009) for the wild type, 0.607 (0.016) for Recql5−/−, 0.614 (0.023) for Blm−/−, and 0.991 (0.025) for Blm−/−Recql5−/−.

In cells from both Bloom syndrome patients and Blm knockout mice, elevated frequencies of SCE are accompanied by an increased incidence of multiradial structures (16, 41), which are indicative of interchromosomal exchange. Consistent with these previous observations, we observed six such structures from 200 metaphase spreads derived from Recql5−/− ES cells (Fig. 4e and f) but none from >500 spreads from wild-type ES cells. Thus, it appears that the increase in the frequency of SCE in Recql5−/− ES cells is also accompanied by an increased frequency of interchromosomal exchange. However, the frequencies of other types of chromosome aberrations, such as chromsome-chromatid breaks, are not significantly different between Recql5 knockout and wild-type ES cells (data not shown).

The SCE phenotype of Recql5−/− ES cells is due to the inactivation of Recql5.

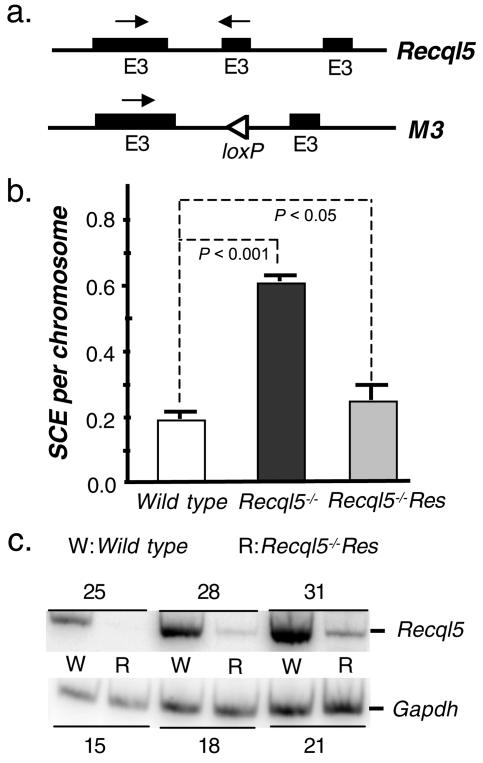

In chicken DT40 cells, deletion of the RECQL5 homologue does not affect the rate of spontaneous SCE (57). This raised the question as to whether the SCE phenotype seen in Recql5−/− ES cells was indeed due to the loss of Recql5 or some other unintended effects that were brought about when this Recql5−/− ES cell line was generated. To address this issue, we attempted to rescue the SCE phenotype of Recql5−/− ES cells by using a genetic complementation strategy. We argued that if the SCE phenotype of our Recql5−/− ES cells was indeed caused by the loss of Recql5 function, reintroduction of a single copy of a functional Recql5 gene into Recql5−/− ES cells would be sufficient to rescue the SCE phenotype, since Recql5+/− ES cells have a normal frequency of SCE.

To ensure the proper expression of the Recql5 gene, we introduced a Recql5-containing BAC vector that contains the coding region plus both 5′ and 3′ regulatory sequences of the Recql5 gene into Recql5−/− ES cells. We obtained a Recql5-containing BAC clone, RPCI-22-51D24, by screening a mouse BAC library. This BAC clone contains the entire Recql5 coding sequence plus more than 10 kb of both 5′ and 3′ regulatory sequences (data not shown). A PGKNeo selection marker was introduced into this BAC clone by the recombineering technique (64). Then, this modified BAC clone was introduced into Recql5−/− ES cells to obtain stable transfected lines (designated Recql5−/− Res cells) (data not shown). RT-PCR analysis using total RNA isolated from two of these Recql5−/− Res clones showed that they both expressed wild-type Recql5 transcript as expected (data not shown and see below).

Initial SCE analysis of 20 chromosome spreads from two of these clones showed that they have frequencies that are much lower than their parental Recql5−/− ES cells, but similar to that of the wild-type control. Thus, a large-scale analysis was carried out to compare the frequencies of SCE among one of these two rescued (Recql5−/− Res) ES cell line, the parental Recql5−/− cells, and the wild-type ES cells. The results of this study confirmed that the SCE of the Recql5−/− Res cell line is indeed rescued to the level of wild-type ES cells (Fig. 5b). However, it remained possible that the reduction of SCE frequency in the Recql5−/− Res cell line was caused by a nonspecific effect, due to overexpression of Recql5. To address this issue, the expression of Recql5 transcripts in this Recql5−/− Res cell line and in wild-type ES cells were quantified and compared. The results of semiquantitative RT-PCR experiments showed that Recql5 was not overexpressed in Recql5−/− Res cells; instead, it was expressed at only about 5% of that in the wild-type ES cells (Fig. 5c). Thus, these data provide the definitive proof that the SCE phenotype of Recql5−/− ES cells is caused by the loss of Recql5 function.

FIG. 5.

Genetic rescue of the SCE phenotype in Recql5−/− ES cells. (a) A schematic illustration of wild-type Recql5 and M3 alleles, showing the locations of primers (arrows) used in the RT-PCRs. (b) The frequencies of SCE in wild-type, Recql5−/−, and Recql5−/− Res cells. Error bars indicate standard errors of the mean and P values were calculated by one-way ANOVA with posttest. (c) The results of semiquantitative RT-PCR analyses. Semiquantitative RT-PCRs were performed with total RNA extracted from wild-type (W) and Recql5−/− Res (R) ES cells. Primers used in the RT-PCRs are indicated in panel a as arrows above the wild-type Recql5 allele. The expression of the Gapdh gene was used as an internal control to compare the levels of Recql5 expression among samples. The cycle numbers of RT-PCRs were indicated above or below the images, showing results for Recql5 and Gapdh, respectively.

Recql5 and Blm have nonredundant roles in the suppression of crossovers in mouse ES cells.

The observation that deletions of Blm or Recql5 led to similar SCE phenotypes in mouse ES cells raised the question as to whether these two RecQ helicases are both required in the same genetic pathway or act independently through different pathways to suppress crossovers in mouse ES cells. To address this issue, we examined the effect of the deletion of Recql5 on the frequency of SCE in Blm knockout ES cells.

To generate Blm−/− Recql5−/− ES cells, we inactivated the two copies of the Recql5 gene in Blm−/− ES cells, the blm (M3/M4) ES cells (19), by two consecutive rounds of gene targeting experiments. First, we generate a new Recql5-targeted allele in these Blm−/− ES cells, the M4 allele, by the same strategy described previously for a similar experiment with wild-type ES cells (Fig. 2a) but with inactivation of the other Recql5 allele by another strategy which replaces exon 4 of Recql5 with a PGKPuro cassette (information available upon request). These experiments resulted in the generation of several Blm−/− Recql5−/− ES cell lines. Blm−/− Recql5−/− ES cells showed growth characteristics similar to those of wild-type ES cells (data not shown). RT-PCR using a pair of primers specific for exon 3 and exon 5, respectively, failed to detect any Recql5 transcript from these cells (information available upon request), indicating that neither mutant allele produces any detectable amount of Recql5 transcripts.

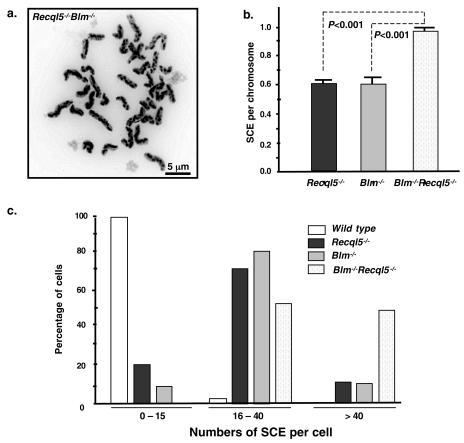

We then examined the effect of the deletion of Recql5 on the frequency of SCE in Blm−/− ES cells. Specifically, we compared the frequencies of SCE among the Blm−/−, Recql5−/−, and Blm−/− Recql5−/− ES cells. To ensure the accuracy of the experiments, the SCE frequencies of all the cell lines described in this paper were derived from cells that were prepared simultaneously in one experiment. This study showed that Blm−/− Recql5−/− ES cells have a very high frequency of SCE. In some cells, the presence of many SCE events on some chromosomes made it difficult to accurately measure the number of SCE (Fig. 6a). Nevertheless, even based on an anticipated underestimation, the overall frequency of SCE of the double-knockout ES cells was significantly higher than that of either Blm−/− or Recql5−/− ES cells (P < 0.001 in both cases) (Fig. 6b). In particular, the percentage of cells with more than 40 SCEs (e.g., an average of 1 SCE per chromosome) is much higher in the Blm−/− Recql5−/− ES cells (44%) than in Blm−/− ES cells (9.3%), Recql5−/− ES cells (10.7%), and wild-type ES cells (<0.1%) (Fig. 6c). Therefore, these data clearly showed that in the mouse ES cells, Blm and Recql5 have nonredundant roles in the suppression of crossovers.

FIG. 6.

Spontaneous SCE in Recql5−/− Blm−/− ES cells. (a) A representative metaphase spread with a high number of SCE. (b) The result of statistical analysis on the frequencies of SCE. The numbers of SCE per chromosome in Recql5−/−, Blm−/−, and Recql5−/− Blm−/− ES cells were compared. Error bars indicate the standard errors of the mean, and P values were calculated by one-way ANOVA with posttest. (c) The distributions of cells in categories of different ranges of SCE.

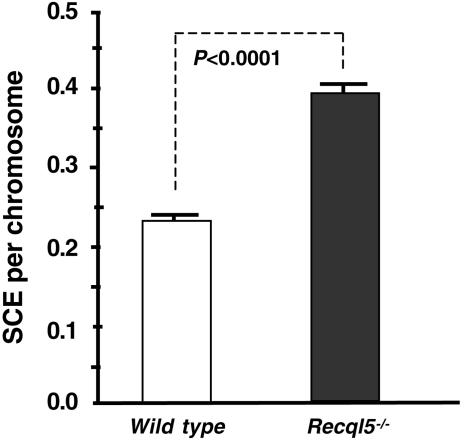

Primary embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cells derived from Recql5 knockout mice exhibited an elevated SCE frequency.

Our data from experiments using knockout ES cells clearly showed that Recql5 plays an important role in the suppression of crossovers in mouse ES cells. However, mouse ES cells are unique in many aspects of their cell cycle checkpoint controls (1), as well as DNA repair and recombination (10, 11). Thus, a mutant phenotype observed in knockout ES cells might not indicate a similar phenotype in differentiated cells of the corresponding knockout mice. To examine whether Recql5 also has a role in suppressing crossovers in differentiated mouse cells, we created Recql5 knockout mice and studied the frequencies of SCE in differentiated cells derived from Recql5 knockout mice.

We first used ES cells that carry the Recql5 conditional knockout allele and the M2 allele (Fig. 1a) to generate a Recql5 conditional knockout mouse model. Two M2 allele-containing ES cell lines, Recql5tm2Luo-1, and Recql5tm2Luo-2, were used to generate mice carrying the M2 conditional knockout allele. Germ line transmission of the M2 conditional knockout allele was obtained from both cell lines (Fig. 7a and b and data not shown). We then introduced this Recql5 conditional allele into female Zp3-Cre transgenic mice (8) to facilitate the deletion of exon 4 of Recql5. Removal of the exon 4 of the Recql5 gene by Cre-mediated deletion in the oocytes of Zp3-Cre transgenic mice produced heterozygous Recql5 knockout mutant mice carrying the M3 allele as designed (Fig. 7a and c). Heterozygous Recql5 knockout mutant mice are viable, fertile, and indistinguishable from their wild-type littermates (data not shown). Intercrosses among these heterozygous mutants gave rise to progeny, including homozygous mutants, at the expected ratio (Fig. 7d and data not shown). To date, 50 homozygous Recql5 knockout mice have been monitored for 3 to 7 months. These mice do not appear to have any gross developmental abnormalities. They also enjoy normal postnatal growth and development and have normal fertility (data not shown). Detailed phenotypic characterization of these mice is in progress. In the meantime, these knockout mice provide a source for differentiated Recql5 knockout cells to study the effect of Recql5 deficiency on the rates of crossovers in differentiated mouse cells.

Primary MEFs provide a readily available source of differentiated cells from knockout mouse models that are also compatible with SCE analysis. Thus, to examine whether Recql5 plays a role in suppressing crossovers in differentiated mouse cells, we compared the frequencies of MEFs derived from three wild-type and four Recql5 knockout embryos. The results of this study showed that Recql5 knockout MEFs have a significantly elevated frequency of SCE compared with that of wild type MEFs (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 8). Therefore, Recql5 is also required for the suppression of crossovers in differentiated MEF cells.

FIG. 8.

The frequencies of spontaneous SCE in primary MEF cells. The numbers of SCE per chromosome in wild-type and Recql5−/− MEF cells were compared. Error bars indicate the standard errors of the mean, and P values were calculated by t test.

DISCUSSION

Role of Recql5 and its homologues in the suppression of crossovers in mitotic cells.

The observation that human RECQL5 physically interacts with both TOPOIII alpha and TOPOIIIβ prompted the speculation that RECQL5 and its homologues might play important roles in the suppression of crossovers. This was challenged by the finding that deletion of the chicken RECQL5 homologue in DT40 cells did not lead to an increase in the rate of spontaneous SCE (57). In contrast, we have shown here that the deletion of Recql5 alone in mouse ES cells is sufficient to cause a significant increase in the frequency of spontaneous SCE, comparable to the increase caused by the deletion of Blm. Furthermore, this elevated SCE frequency is accompanied by an increased incidence of multiradial structures, which are indicative of interchromosomal exchanges. The SCE phenotype observed in Recql5 knockout ES cells does not appear to be caused by either a dominant negative effect or gain-of-function effect due to the targeted mutation, since heterozygous knockout ES cells do not have this phenotype. Most importantly, the results from our genetic complementation experiment clearly demonstrated that the elevated SCE frequency is caused by the loss of Recql5. At present, we do not have a clear explanation for this apparent discrepancy between our findings and that based on DT40 cells (57). This could reflect either cell-type-specific or species-specific differences between chicken DT40 cells and mouse ES cells. However, our observations of similar SCE phenotypes in two different Recql5 knockout cells, ES cells and MEFs, argue against a cell-type-specific difference. Further experiments are needed to resolve this issue. Importantly, our findings confirm the speculation that multiple pathways exist for suppressing crossovers in mitotic cells, which should be expected given the great complexity of the mammalian genome and the potential deadly consequences, i.e., carcinogenesis, due to crossovers. Mouse Recql5β and human RECQL5β share 72% identities in amino acid composition and likely have similar functions. Thus, we believe that human RECQL5 is also required for the suppression of spontaneous crossovers in mitotic cells. Currently, it remains unclear whether these helicases play any roles in regulating meiotic crossovers.

Human RECQL5 produces three mRNAs as the result of alternative RNA processing and hence was predicted to encode three RecQ helicase isoforms (29, 49, 51). The expression of mouse Recql5 has not been very well studied, but it is predicted to produce three isoforms similar to those of humans, since human RECQL5 and mouse Recql5 genes are highly conserved. In all the Recql5 knockout alleles reported here, the targeted mutations were expected to delete the conserved helicase domain of all three predicted Recql5 helicase isoforms. Thus, the SCE phenotype that we have observed could be due to the lack of any of these isoforms. However, only RECQL5β has been found to interact with TOPOIIIα and IIIβ (51), to have the 3′-to-5′ helicase activity, and to have single-strand annealing activity (14). Although it is not yet clear whether the helicase activity or the single-strand annealing activity is related to the regulation of recombination, it has been shown that the interaction between BLM and TOPOIIIα plays an important role in the suppression of crossovers (26). Furthermore, RECQL5β is also the only isoform that contains a putative nuclear localization signal. Thus, we believe that the deletion of Recql5β is primarily responsible for the SCE phenotype observed in our Recql5 knockout ES cells. But future experiments are needed to verify or refute this prediction.

The nonredundant roles of Blm and Recql5 in the suppression of crossovers.

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, SGS1 and SRS2 are known to be involved in nonredundant pathways to control crossovers, indicating the importance of such regulatory mechanisms in the homeostasis of eukaryotes (26). This also suggests that crossovers can be initiated from different events that are subjected to the regulations of different pathways. We showed here that Blm and Recql5 are apparently involved in independent, nonredundant pathways to suppress crossovers in mouse ES cells, confirming the speculation that mammals also have more than one pathway for suppressing crossovers in mitotic cells. Interestingly, to date, no mammalian homologues of SRS2 have been found.

Our present data do not explain how these two helicases have different specificities towards specific types of recombination events or pathways. It is conceivable that the specificities lie in the unique structural motifs found within them. Members of the RecQ helicase family all have a conserved helicase domain but also have unique motifs at their N or C termini, or both. Thus, the specificity of an individual RecQ helicase is likely dictated, at least in part, by its N- and/or C-terminal motifs. In this regard, it is noteworthy that BLM and RECQL5β are structurally distinct. In particular, BLM has distinct structural motifs at both its N and C termini, whereas RECQL5β lacks any discernible conserved motifs at its N terminus (51). BLM interacts with TOPOIIIα and several other components of the replication and recombination machineries via both its unique N- and C-terminal motifs (3, 58, 61). To date, the only known interacting partners for RECQL5 are TOPOIIIα and IIIβ (51). But given the lack of any identifiable N-terminal motifs in all predicted isoforms encoded by RECQL5 (51), it is conceivable that their interacting partners differ from those of BLM. Functionally speaking, both BLM and RECQL5β are able to unwind double-stranded DNA in a 3′-to-5′ direction in vitro, but only RECQL5β can stimulate the annealing of complementary single-stranded DNA molecules (14). Thus, it is clear that there exist both structural and functional differences between human BLM and RECQL5. Homologues of the RecQ family are highly conserved between mice and humans. In particular, human RECQL5β and mouse Recql5β share 72% identities. Thus, it is likely that mouse Blm and Recql5β also have structural and functional properties similar to those of their human counterparts.

An elevated frequency of crossovers could either be due to an overall increase in the frequency of recombination or from a skewing in the resolution of recombination repair intermediates that favors crossovers. Based on our present data, we cannot determine the mechanism by which Recql5 deficiency increases SCE frequency in mouse ES cells. It should be noted that this is also an unresolved issue with respect to BLM- and Blm-deficient cells. Future experiments are needed to address this issue.

RecQ DNA helicase-mediated suppression of crossovers and carcinogenesis.

Mutations in the single RecQ DNA helicase-encoding gene in budding yeast cause a multitude of phenotypes, including hyperrecombination and chromosome missegregation (59, 60). In humans, mutations in three of five RecQ-encoding genes give rise to three distinct cancer-prone genetic diseases: Werner (63), Rothmund-Thomson (30), and Bloom (9) syndromes. These observations imply that RecQ helicases have multiple distinct roles and that in mammals, individual RecQ helicase has acquired specialized roles in maintaining the stability of the genome. Cells from Werner syndrome patients have been shown to exhibit extensive deletions (12). The nature of genomic instability associated with Rothmund-Thomson syndrome has not been well characterized. However, we very recently showed that Recql4-deficient cells derived from Recql4 knockout mice exhibited a chromosomal instability phenotype as the result of defective sister chromatid cohesion (39). We showed here that two members of the mammalian RecQ gene family, Blm and Recql5, are involved in the suppression of crossovers. This new finding underscores both the essential role of recombination repair in mitotic cells and the importance of regulating this repair process to suppress crossovers, which can lead to deleterious consequences.

SCE, the outcome of crossovers between identical sister chromatids, results in high-fidelity recombination repair of DNA lesions. Thus, SCE is not mutagenic or oncogenic. However, other types of crossovers in mitotic cells can lead to potential oncogenic events, such as translocations, deletion, inversion, and somatic LOH. In particular, recent data have shown that crossovers between homologous chromosomes can lead to crossover-mediated LOH (2, 36). This crossover-mediated LOH represents a major mechanism of LOH in noncancerous human cells (20). Importantly, such a mechanism also has been shown to play a critical role in the loss of function of tumor suppressor genes at the early stage of colorectal cancer (22, 37, 52). Consistent with this, both Bloom syndrome patients and Blm knockout mice exhibit striking cancer susceptibility phenotypes (16, 37, 41). Thus, our finding that Blm and Recql5 are involved in nonredundant pathways to suppress crossovers in mouse ES cells suggests that Recql5 also plays important roles in the suppression of crossovers and perhaps carcinogenesis. Currently, human RECQL5 mutations have not been linked to any cancer-prone disorders. However, given the viable nature of Recql5 knockout mice and the anticipated functional conservation between human RECQL5 and mouse Recql5, it is reasonable to speculate that RECQL5 deficiency may be compatible with viability in humans. Thus, it remains possible that RECQL5 is the disease-causing gene for a cancer-prone syndrome. The mouse model reported here will provide a valuable tool for investigating the role of Recql5 as well as the relative contributions of the Blm-dependent and Recql5-dependent pathways to tumor suppression in mice. The results of such studies may also aid in the future identification of the human disease(s) that is caused by RECQL5 mutations, should there be any.

Acknowledgments

We thank Peter Harte, Patricia Hunt, and David Boothman for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aladjem, M. I., B. T. Spike, L. W. Rodewald, T. J. Hope, M. Klemm, R. Jaenisch, and G. M. Wahl. 1998. ES cells do not activate p53-dependent stress responses and undergo p53-independent apoptosis in response to DNA damage. Curr. Biol. 8:145-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beumer, K. J., S. Pimpinelli, and K. G. Golic. 1998. Induced chromosomal exchange directs the segregation of recombinant chromatids in mitosis of Drosophila. Genetics 150:173-188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braybrooke, J. P., J. L. Li, L. Wu, F. Caple, F. E. Benson, and I. D. Hickson. 2003. Functional interaction between the Bloom's syndrome helicase and the RAD51 paralog, RAD51L3 (RAD51D). J. Biol. Chem. 278:48357-48366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaganti, R. S., S. Schonberg, and J. German. 1974. A manyfold increase in sister chromatid exchanges in Bloom's syndrome lymphocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 71:4508-4512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chester, N., F. Kuo, C. Kozak, C. D. O'Hara, and P. Leder. 1998. Stage-specific apoptosis, developmental delay, and embryonic lethality in mice homozygous for a targeted disruption in the murine Bloom's syndrome gene. Genes Dev. 12:3382-3393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Constantinou, A., M. Tarsounas, J. K. Karow, R. M. Brosh, V. A. Bohr, I. D. Hickson, and S. C. West. 2000. Werner's syndrome protein (WRN) migrates Holliday junctions and co-localizes with RPA upon replication arrest. EMBO Rep. 1:80-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cox, M. M. 2002. The nonmutagenic repair of broken replication forks via recombination. Mutat. Res. 510:107-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Vries, W. N., L. T. Binns, K. S. Fancher, J. Dean, R. Moore, R. Kemler, and B. B. Knowles. 2000. Expression of Cre recombinase in mouse oocytes: a means to study maternal effect genes. Genesis 26:110-112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellis, N. A., J. Groden, T. Z. Ye, J. Straughen, D. J. Lennon, S. Ciocci, M. Proytcheva, and J. German. 1995. The Bloom's syndrome gene product is homologous to RecQ helicases. Cell 83:655-666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Essers, J., R. W. Hendriks, S. M. Swagemakers, C. Troelstra, J. de Wit, D. Bootsma, J. H. Hoeijmakers, and R. Kanaar. 1997. Disruption of mouse RAD54 reduces ionizing radiation resistance and homologous recombination. Cell 89:195-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Essers, J., H. van Steeg, J. de Wit, S. M. Swagemakers, M. Vermeij, J. H. Hoeijmakers, and R. Kanaar. 2000. Homologous and non-homologous recombination differentially affect DNA damage repair in mice. EMBO J. 19:1703-1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukuchi, K., G. M. Martin, and R. J. Monnat, Jr. 1989. Mutator phenotype of Werner syndrome is characterized by extensive deletions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:5893-5897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gangloff, S., J. P. McDonald, C. Bendixen, L. Arthur, and R. Rothstein. 1994. The yeast type I topoisomerase Top3 interacts with Sgs1, a DNA helicase homolog: a potential eukaryotic reverse gyrase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:8391-8398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garcia, P. L., Y. Liu, J. Jiricny, S. C. West, and P. Janscak. 2004. Hum. RECQ5β, a protein with DNA helicase and strand-annealing activities in a single polypeptide. EMBO J. 23:2882-2891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.German, J. 1993. Bloom syndrome: a mendelian prototype of somatic mutational disease. Medicine (Baltimore) 72:393-406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.German, J. 1995. Bloom's syndrome. Dermatol. Clin. 13:7-18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.German, J., and B. Alhadeff. 1994. Sister chromatic exchange (SCE) analysis, p. 8.6.1-8.6.10. In N. C. Dracopoli, J. L. Haines, B. R. Korf, D. T. Moir, C. C. Morton, C. E. Seidman, J. A. Seidman and D. R. Smith (ed.), Current protocols in human genetics. John Wiley & Sons, New York, N.Y.

- 18.Goss, K. H., M. A. Risinger, J. J. Kordich, M. M. Sanz, J. E. Straughen, L. E. Slovek, A. J. Capobianco, J. German, G. P. Boivin, and J. Groden. 2002. Enhanced tumor formation in mice heterozygous for Blm mutation. Science 297:2051-2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo, G., W. Wang, and A. Bradley. 2004. Mismatch repair genes identified using genetic screens in Blm-deficient embryonic stem cells. Nature 429:891-895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta, P. K., A. Sahota, S. A. Boyadjiev, S. Bye, C. Shao, J. P. O'Neill, T. C. Hunter, R. J. Albertini, P. J. Stambrook, and J. A. Tischfield. 1997. High frequency in vivo loss of heterozygosity is primarily a consequence of mitotic recombination. Cancer Res. 57:1188-1193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haber, J. E. 1999. DNA recombination: the replication connection. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24:271-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haigis, K. M., and W. F. Dove. 2003. A Robertsonian translocation suppresses a somatic recombination pathway to loss of heterozygosity. Nat. Genet. 33:33-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hassold, T., S. Sherman, and P. Hunt. 2000. Counting cross-overs: characterizing meiotic recombination in mammals. Hum. Mol. Genet. 9:2409-2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hickson, I. D. 2003. RecQ helicases: caretakers of the genome. Nat. Rev. Cancer 3:169-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu, P., S. F. Beresten, A. J. van Brabant, T. Z. Ye, P. P. Pandolfi, F. B. Johnson, L. Guarente, and N. A. Ellis. 2001. Evidence for BLM and topoisomerase IIIα interaction in genomic stability. Hum. Mol. Genet. 10:1287-1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ira, G., A. Malkova, G. Liberi, M. Foiani, and J. E. Haber. 2003. Srs2 and Sgs1-Top3 suppress crossovers during double-strand break repair in yeast. Cell 115:401-411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson, R. D., and M. Jasin. 2000. Sister chromatid gene conversion is a prominent double-strand break repair pathway in mammalian cells. EMBO J. 19:3398-3407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karow, J. K., A. Constantinou, J. L. Li, S. C. West, and I. D. Hickson. 2000. The Bloom's syndrome gene product promotes branch migration of holliday junctions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:6504-6508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kitao, S., I. Ohsugi, K. Ichikawa, M. Goto, Y. Furuichi, and A. Shimamoto. 1998. Cloning of two new human helicase genes of the RecQ family: biological significance of multiple species in higher eukaryotes. Genomics 54:443-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kitao, S., A. Shimamoto, M. Goto, R. W. Miller, W. A. Smithson, N. M. Lindor, and Y. Furuichi. 1999. Mutations in RECQL4 cause a subset of cases of Rothmund-Thomson syndrome. Nat. Genet. 22:82-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knudson, A. G., Jr. 1971. Mutation and cancer: statistical study of retinoblastoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 68:820-823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knudson, A. G., Jr. 1978. Retinoblastoma: a prototypic hereditary neoplasm. Semin. Oncol. 5:57-60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krejci, L., S. Van Komen, Y. Li, J. Villemain, M. S. Reddy, H. Klein, T. Ellenberger, and P. Sung. 2003. DNA helicase Srs2 disrupts the Rad51 presynaptic filament. Nature 423:305-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuzminov, A. 2001. DNA replication meets genetic exchange: chromosomal damage and its repair by homologous recombination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:8461-8468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee, E. C., D. Yu, J. Martinez de Velasco, L. Tessarollo, D. A. Swing, D. L. Court, N. A. Jenkins, and N. G. Copeland. 2001. A highly efficient Escherichia coli-based chromosome engineering system adapted for recombinogenic targeting and subcloning of BAC DNA. Genomics 73:56-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu, P., N. A. Jenkins, and N. G. Copeland. 2002. Efficient Cre-loxP-induced mitotic recombination in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat. Genet. 30:66-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luo, G., I. M. Santoro, L. D. McDaniel, I. Nishijima, M. Mills, H. Youssoufian, H. Vogel, R. A. Schultz, and A. Bradley. 2000. Cancer predisposition caused by elevated mitotic recombination in Bloom mice. Nat. Genet. 26:424-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luo, G., M. S. Yao, C. F. Bender, M. Mills, A. R. Bladl, A. Bradley, and J. H. Petrini. 1999. Disruption of mRad50 causes embryonic stem cell lethality, abnormal embryonic development, and sensitivity to ionizing radiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:7376-7381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mann, M. B., C. A. Hodges, E. Barnes, H. Vogel, T. J. Hassold, and G. Luo. 2005. Defective sister-chromatid cohesion, aneuploidy and cancer predisposition in a mouse model of type II Rothmund-Thomson syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 14:813-825. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.McCullough, A. J., and S. M. Berget. 1997. G triplets located throughout a class of small vertebrate introns enforce intron borders and regulate splice site selection. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:4562-4571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McDaniel, L. D., N. Chester, M. Watson, A. D. Borowsky, P. Leder, and R. A. Schultz. 2003. Chromosome instability and tumor predisposition inversely correlate with BLM protein levels. DNA Repair (Amsterdam) 2:1387-1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moynahan, M. E., and M. Jasin. 1997. Loss of heterozygosity induced by a chromosomal double-strand break. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:8988-8993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murray, J. M., H. D. Lindsay, C. A. Munday, and A. M. Carr. 1997. Role of Schizosaccharomyces pombe RecQ homolog, recombination, and checkpoint genes in UV damage tolerance. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:6868-6875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nakayama, H., K. Nakayama, R. Nakayama, N. Irino, Y. Nakayama, and P. C. Hanawalt. 1984. Isolation and genetic characterization of a thymineless death-resistant mutant of Escherichia coli K12: identification of a new mutation (recQ1) that blocks the RecF recombination pathway. Mol. Gen. Genet. 195:474-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ohhata, T., R. Araki, R. Fukumura, A. Kuroiwa, Y. Matsuda, and M. Abe. 2001. Cloning, genomic structure and chromosomal localization of the gene encoding mouse DNA helicase RECQL5β. Gene 280:59-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Onclercq-Delic, R., P. Calsou, C. Delteil, B. Salles, D. Papadopoulo, and M. Amor-Gueret. 2003. Possible anti-recombinogenic role of Bloom's syndrome helicase in double-strand break processing. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:6272-6282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Puranam, K. L., and P. J. Blackshear. 1994. Cloning and characterization of RECQL, a potential human homologue of the Escherichia coli DNA helicase RecQ. J. Biol. Chem. 269:29838-29845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Richardson, C., M. E. Moynahan, and M. Jasin. 1998. Double-strand break repair by interchromosomal recombination: suppression of chromosomal translocations. Genes Dev. 12:3831-3842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sekelsky, J. J., M. H. Brodsky, G. M. Rubin, and R. S. Hawley. 1999. Drosophila and human RecQ5 exist in different isoforms generated by alternative splicing. Nucleic Acids Res. 27:3762-3769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seki, M., H. Miyazawa, S. Tada, J. Yanagisawa, T. Yamaoka, S. Hoshino, K. Ozawa, T. Eki, M. Nogami, K. Okumura, et al. 1994. Molecular cloning of cDNA encoding human DNA helicase Q1 which has homology to Escherichia coli Rec Q helicase and localization of the gene at chromosome 12p12. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4566-4573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shimamoto, A., K. Nishikawa, S. Kitao, and Y. Furuichi. 2000. Human RecQ5β, a large isomer of RecQ5 DNA helicase, localizes in the nucleoplasm and interacts with topoisomerases 3α and 3β. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:1647-1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sieber, O. M., H. Lamlum, M. D. Crabtree, A. J. Rowan, E. Barclay, L. Lipton, S. Hodgson, H. J. Thomas, K. Neale, R. K. Phillips, S. M. Farrington, M. G. Dunlop, H. J. Mueller, M. L. Bisgaard, S. Bulow, P. Fidalgo, C. Albuquerque, M. I. Scarano, W. Bodmer, I. P. Tomlinson, and K. Heinimann. 2002. Whole-gene APC deletions cause classical familial adenomatous polyposis, but not attenuated polyposis or “multiple” colorectal adenomas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:2954-2958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stewart, E., C. R. Chapman, F. Al-Khodairy, A. M. Carr, and T. Enoch. 1997. rqh1+, a fission yeast gene related to the Bloom's and Werner's syndrome genes, is required for reversible S phase arrest. EMBO J. 16:2682-2692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Traverso, G., C. Bettegowda, J. Kraus, M. R. Speicher, K. W. Kinzler, B. Vogelstein, and C. Lengauer. 2003. Hyper-recombination and genetic instability in BLM-deficient epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 63:8578-8581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Veaute, X., J. Jeusset, C. Soustelle, S. C. Kowalczykowski, E. Le Cam, and F. Fabre. 2003. The Srs2 helicase prevents recombination by disrupting Rad51 nucleoprotein filaments. Nature 423:309-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vilenchik, M. M., and A. G. Knudson. 2003. Endogenous DNA double-strand breaks: production, fidelity of repair, and induction of cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:12871-12876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang, W., M. Seki, Y. Narita, T. Nakagawa, A. Yoshimura, M. Otsuki, Y. Kawabe, S. Tada, H. Yagi, Y. Ishii, and T. Enomoto. 2003. Functional relation among RecQ family helicases RecQL1, RecQL5, and BLM in cell growth and sister chromatid exchange formation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:3527-3535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang, Y., D. Cortez, P. Yazdi, N. Neff, S. J. Elledge, and J. Qin. 2000. BASC, a super complex of BRCA1-associated proteins involved in the recognition and repair of aberrant DNA structures. Genes Dev. 14:927-939. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Watt, P. M., I. D. Hickson, R. H. Borts, and E. J. Louis. 1996. SGS1, a homologue of the Bloom's and Werner's syndrome genes, is required for maintenance of genome stability in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 144:935-945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Watt, P. M., E. J. Louis, R. H. Borts, and I. D. Hickson. 1995. Sgs1: a eukaryotic homolog of E. coli RecQ that interacts with topoisomerase II in vivo and is required for faithful chromosome segregation. Cell 81:253-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wu, L., S. L. Davies, N. C. Levitt, and I. D. Hickson. 2001. Potential role for the BLM helicase in recombinational repair via a conserved interaction with RAD51. J. Biol. Chem. 276:19375-19381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wu, L., and I. D. Hickson. 2003. The Bloom's syndrome helicase suppresses crossing over during homologous recombination. Nature 426:870-874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yu, C. E., J. Oshima, Y. H. Fu, E. M. Wijsman, F. Hisama, R. Alisch, S. Matthews, J. Nakura, T. Miki, S. Ouais, G. M. Martin, J. Mulligan, and G. D. Schellenberg. 1996. Positional cloning of the Werner's syndrome gene. Science 272:258-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yu, D., H. M. Ellis, E. C. Lee, N. A. Jenkins, N. G. Copeland, and D. L. Court. 2000. An efficient recombination system for chromosome engineering in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:5978-5983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]