ABSTRACT

Liver X receptor (LXR) signaling broadly restricts virus replication; however, the mechanisms of restriction are poorly defined. Here, we demonstrate that the cellular E3 ligase LXR-inducible degrader of low-density lipoprotein receptor (IDOL) targets the human cytomegalovirus (HMCV) UL136p33 protein for turnover. UL136 encodes multiple proteins that differentially impact latency and reactivation. UL136p33 is a determinant of reactivation. UL136p33 is targeted for rapid turnover by the proteasome, and its stabilization by mutation of lysine residues to arginine results in a failure to quiet replication for latency. We show that IDOL targets UL136p33 for turnover but not the stabilized variant. IDOL is highly expressed in undifferentiated hematopoietic cells where HCMV establishes latency but is sharply downregulated upon differentiation, a stimulus for reactivation. We hypothesize that IDOL maintains low levels of UL136p33 for the establishment of latency. Consistent with this hypothesis, knockdown of IDOL impacts viral gene expression in wild-type (WT) HCMV infection but not in infection where UL136p33 has been stabilized. Furthermore, the induction of LXR signaling restricts WT HCMV reactivation from latency but does not affect the replication of a recombinant virus expressing a stabilized variant of UL136p33. This work establishes the UL136p33-IDOL interaction as a key regulator of the bistable switch between latency and reactivation. It further suggests a model whereby a key viral determinant of HCMV reactivation is regulated by a host E3 ligase and acts as a sensor at the tipping point between the decision to maintain the latent state or exit latency for reactivation.

IMPORTANCE Herpesviruses establish lifelong latent infections, which pose an important risk for disease particularly in the immunocompromised. Our work is focused on the betaherpesvirus human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) that latently infects the majority of the population worldwide. Defining the mechanisms by which HCMV establishes latency or reactivates from latency is important for controlling viral disease. Here, we demonstrate that the cellular inducible degrader of low-density lipoprotein receptor (IDOL) targets a HCMV determinant of reactivation for degradation. The instability of this determinant is important for the establishment of latency. This work defines a pivotal virus-host interaction that allows HCMV to sense changes in host biology to navigate decisions to establish latency or to replicate.

KEYWORDS: cytomegalovirus, herpesvirus, IDOL, LXR, liver X receptor signaling, UL136, cholesterol

INTRODUCTION

Viral latency, the ability of a virus to persist indefinitely in the infected host, is a hallmark of herpesviruses. Latency is defined as a nonreplicative state punctuated by sporadic reactivation events where the virus replicates productively for transmission. Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is a betaherpesvirus that establishes latent infection in hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs) and cells of the myeloid lineage (1). Reactivation of HCMV from latency in the immunocompromised can result in life-threatening disease and is a particularly important risk factor in the context of stem cell and solid organ transplantation. The molecular mechanisms by which HCMV senses changes in the host to make decisions to maintain latency or reactivate from latency are important for developing novel strategies to control viral reactivation and subsequent cytomegalovirus (CMV) disease.

Latency is a complex multifactorial phenomenon dependent on viral determinants and host cell intrinsic, innate, and adaptive responses, as well as host cell signaling and chromatin remodeling (2). Current paradigms hold that HCMV reactivation is tightly connected to hematopoietic cell differentiation (3–7) or inflammatory signaling (3, 8–10). However, much remains to be understood about the precise host contributions and key viral factors that navigate the entry into or exit from latency. We and others have defined the roles of the UL133-138 gene locus encoded within the ULb’ region of the HCMV genome for latency and reactivation. UL138 is required for latency, and the UL138 protein functions by regulating cell surface receptor trafficking and signaling (11–14) and innate immune responses (15, 16) and also contributes to the repression of viral gene expression (17). UL135, by contrast, is required for reactivation from latency, functioning in part by opposing the function of UL138 (18–20). UL136 is expressed as 5 protein isoforms that have differential effects on the establishment of latency or reactivation. The largest, membrane-associated isoforms, namely, UL136p33 (UL136p33) and p26, are required for reactivation, whereas the small, soluble isoforms are required for latency in both in vitro and in vivo experimental models (21, 22). Importantly, UL136 proteins accumulate with delayed kinetics relative to UL135 and UL138, and maximal accumulation of UL136 gene products depend on the onset of viral DNA synthesis and/or entry into late phase. Given its kinetics and dependence on viral DNA synthesis for maximal expression, we postulate that UL136 may negotiate checkpoints that function to maintain latency or commitment to reactivation from latency. Identifying host pathways regulating these viral determinants is key to defining the mechanistic basis by which HCMV senses and responds to changes in host biology to maintain latency or to reactivate.

The cellular environment the virus encounters upon infection undoubtedly plays important roles in the establishment of latency with a host of restriction factors prepared to silence the viral genome, as well as a transcriptional milieu that impacts viral gene expression. As an example, we have shown that the cellular transcription factor early growth response factor-1 (EGR-1) drives the expression of UL138 for the establishment of latency (20, 23). As EGR-1 is required to maintain stemness in the bone marrow niche and is highly expressed in undifferentiated hematopoietic cells (24), cells are primed to drive the expression of UL138 for latency upon infection. In addition, HCMV regulates EGR-1 expression through the differential trafficking and turnover of the host receptor tyrosine kinase epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) upstream of EGR-1 (11, 19, 20) and through direct targeting by microRNAs that promote reactivation (23). Thus, HCMV has evolved a multipronged strategy to manipulate and utilize host pathways to regulate its gene expression, hardwiring infection into host signaling pathways. With regard to reactivation, activation of the major immediate early (MIE) transcriptional unit, encoding the major transactivators for viral replication, is highly dependent on host transcription factors in myeloid cells (25). Host transcription factors CREB, FOXO3a, and AP-1 are downstream of major signaling pathways, including Src, PI3K/Akt, and MEK/ERK, and are important for re-expression of MIE genes (26–28). Furthermore, UL7 encodes a ligand that binds the cellular Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 receptor (Flt-3R) that when secreted upon reactivation activates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling to prevent cell death and to stimulate differentiation for reactivation (29, 30). Through its coevolution with the human host, the biology of HCMV infection has become tightly intertwined with the biology of its host, which reflects the complex mechanisms the virus has evolved to “sense” and “respond” to changes in the cellular environment to influence “decisions”' to maintain latency or reactivate from latency.

Here, we demonstrate that the largest isoform of UL136, namely, UL136p33, is targeted for rapid turnover relative to other UL136 protein isoforms and that its instability (half-life [t1/2], ~1 h) is important to the establishment of latency. We identified the LXR-inducible degrader of low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) IDOL (also known as myosin regulatory light chain interacting protein [MYLIP]) as the host E3 ligase that targets UL136p33 for turnover. IDOL expression is induced by oxysterol activation of the liver X receptor (LXR) (31) and is regulated through hematopoietic differentiation (32, 33). In addition to LDLR, IDOL also targets VLDLR and ApoER-2 and, therefore, is an important homeostatic regulator of intracellular cholesterol (31, 34–36). The targeting of UL136p33 by IDOL suggests that the virus has evolved to be responsive to changes in sterols in its commitment to reactivation. A model emerges whereby high levels of IDOL maintain low levels of UL136p33 for the establishment of latency, and the downregulation of IDOL by differentiation results in the accumulation of UL136p33 to drive reactivation. Indeed, the induction of IDOL results in an increased turnover of UL136p33 and prevents reactivation of HCMV from latency, whereas depletion of IDOL increases viral gene expression in hematopoietic cells. Our findings define UL133p33 as a key viral determinant of HCMV reactivation that acts as a sensor at the tipping point between the decision to maintain the latent state or exit latency for reactivation.

RESULTS

UL136p33 is unstable and targeted for proteasomal degradation.

UL136 is expressed as at least 5 coterminal protein isoforms (Fig. 1A). These isoforms are encoded by transcripts with unique 5′ ends and have distinct roles in viral latency and reactivation (21, 22). The largest of these isoforms is a 33-kDa protein (UL136p33) that is required for replication in endothelial cells as well as reactivation from latency in CD34+ HPCs and in humanized mice (21). Conversely, the two small isoforms p23 and p19 suppress replication in endothelial cells and promote latency in CD34+ HPCs and humanized mice (22). The diametric nature of the UL136 system presupposes additional levels of control to coordinate and commit to one infection program over another, thereby allowing for either optimal replication/reactivation or robust latency. The UL136 isoforms, and particularly the full-length isoform UL136p33, are uniquely labile and sensitive to mechanical lysis while being processed (22). Based on this information, we hypothesized that the concentration of some UL136 isoforms is regulated by increased proteolysis and that the instability of UL136p33 may be important for establishing or maintaining latency.

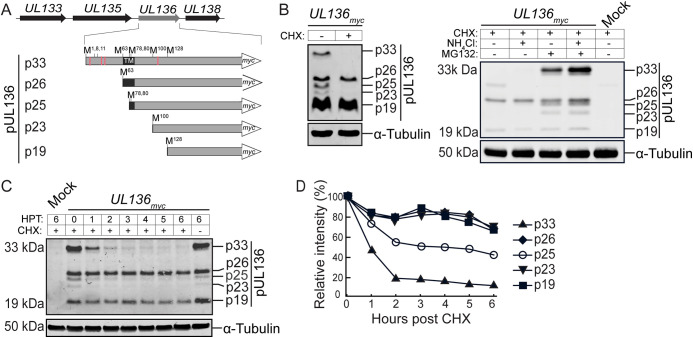

FIG 1.

The UL136p33 isoform is turned over rapidly by the proteasome. (A) Schematic depiction of the UL133-UL138 polycistronic gene locus and UL136 protein isoforms. A C-terminal myc tag is used to detect UL136 isoforms. Red lines represent lysine residues, and the black box shows the putative transmembrane domain (TM). (B to D) Fibroblasts were infected with TB40/E-UL136myc virus at an MOI of 1. (B) At 48 hours postinfection (hpi), cells were treated with 50 μg/mL cycloheximide (CHX) for 6 h (left). Alternatively, mock- or TB40/E-infected cells were treated with CHX in the context of proteasomal (MG132) or lysosomal (NH4Cl) inhibition (right). UL136myc protein isoforms or tubulin as a loading control were detected by immunoblotting using by a monoclonal α-myc antibody or tubulin, respectively. (C) Cells were untreated or treated with CHX at 48 hpi, and UL136 decay was analyzed over a 6-h time course by immunoblotting, as described for panel B. (D) Relative quantification of UL136 isoforms normalized to tubulin. HPT, hours posttreatment.

To explore the possibility that UL136 isoforms have different stabilities, we analyzed the levels of UL136 isoforms in infected fibroblasts treated with cycloheximide (CHX) to halt protein synthesis. Cycloheximide treatment resulted in a striking loss of UL136p33, p25, and p23 but not p26 or p19 (Fig. 1B, left). These results indicated differential stability whereby UL136p33, p25, and p23 may be subject to more rapid turnover, while other UL136 isoforms are relatively stable. Proteasome inhibition robustly rescued UL136p33, p25, and p23 isoforms (Fig. 1B, right panel). Inhibition of the lysosome with NH4Cl had no effect on rescue of any of the UL136 isoforms; however, inhibition of both the lysosome and proteasome showed a somewhat additive effect. Together, these results indicate that the rapid turnover of UL136p33, p25, and p23 is regulated by the proteasome.

To establish the kinetics of isoform turnover, we analyzed the decay of UL136 isoforms in fibroblasts infected with TB40/E-UL136myc and treated with CHX at peak UL136 isoform expression (Fig. 1C). UL136p33 decayed with a half-life of 1 h (t1/2, 1 h) and p25 exhibited a t1/2 of 3 h, while all other isoforms were stable over the 6-h time course (Fig. 1D). The p23 isoform accumulates to very low levels, making the decay of this protein difficult to determine. The rapid decay of UL136p33 relative to the other isoforms, as well as its significance in HCMV reactivation, prompted us to focus on determining the factor(s) contributing to its instability.

Lysine-to-arginine mutations stabilize UL136p33.

UL136 has four lysine (K) residues (denoted by red lines in Fig. 1A), of which three lie upstream of the transmembrane domain (TMD) and are unique to the p33 isoform. To determine if the turnover of UL136p33 was regulated by ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis, we substituted all lysine residues for arginine (R) through site-directed mutagenesis in an expression vector encoding UL136p33 to generate UL136p33mycΔK→R. The p33ΔK→R mutant had a t1/2 of 5 h compared with ~1 h for UL136p33 following CHX treatment (Fig. 2A). This observation, together with the stabilization of UL136p33 by proteasomal inhibition (Fig. 1B), suggests that UL136p33 turnover is regulated by ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal decay. Furthermore, the rapid turnover of exogenously expressed UL136p33 (Fig. 2A, left) indicates that the degradation of UL136p33 is not dependent on virus or infection-induced factors.

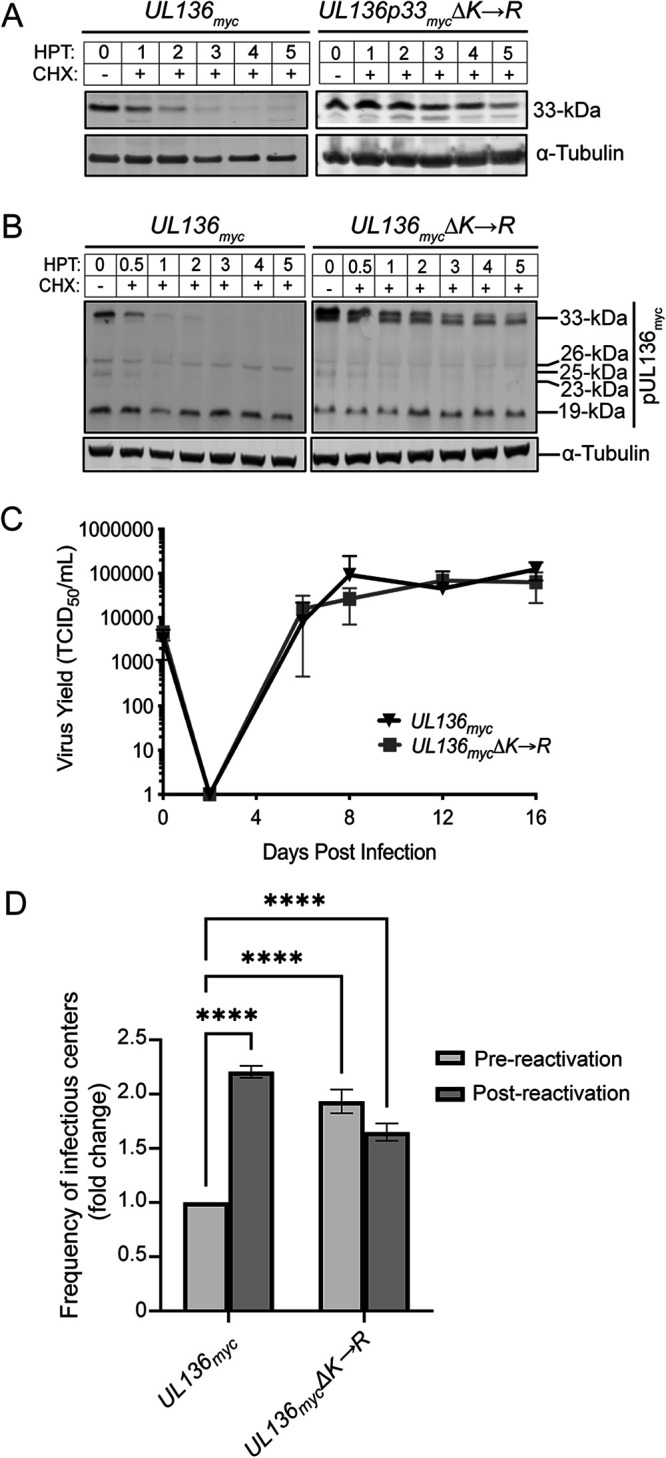

FIG 2.

Stabilizing UL136p33 results in a virus that fails to establish latency, but has no effect on replication in fibroblasts. (A) Fibroblasts were transduced with lentiviruses engineered to express p33myc or p33K→R, and protein decay was analyzed by immunoblotting following CHX treatment. (B) Fibroblasts were infected with TB40/E-UL136myc or TB40/E-UL136mycΔK→R viruses (MOI, 1) and treated with CHX at 48 hpi or left untreated. Protein decay was analyzed as described in Fig. 1C. (C) Fibroblasts were infected at an MOI of 0.02, and samples were collected for 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) at indicated times. All data points are an average of 3 biological replicates, and error bars represent standard deviation. (D) CD34+ HPCs were infected with UL136myc or UL136mycΔK→R viruses (MOI, 2). Infected cells were purified by FACS at 1 dpi seeded into long-term culture. At 10 days, half of the culture was reactivated by seeding intact cells by limiting dilution into coculture with fibroblasts in a cytokine-rich media to promote myeloid differentiation (reactivation). The other half of the culture was mechanically lysed and seeded onto fibroblasts as the prereactivation control. The frequency of infectious centers was determined for each sample by extreme limiting dilution. (C and D) The data represent replicates with cells from 3 independent donors. The means were compared with two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Tukey post hoc test. (C) No significant differences measured. (D) P < 0.0001.

To determine the importance of UL136p33 instability in infection, we introduced the lysine-to-arginine mutations into the UL136myc gene within the bacterial artificial chromosome clone of TB40/E (UL136mycΔK→R). We measured the relative rates of decay in fibroblasts infected with either the parental UL136myc or UL136mycΔK→R virus and treated with CHX. p33ΔK→R was stabilized during infection relative to wild-type UL136p33 (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, we found that stabilization of UL136p33 diminished levels of UL136p26 and p25 isoforms by mechanisms that have yet to be determined.

We then performed multistep growth curves on fibroblasts infected with UL136myc or UL136mycΔK→R to analyze the impact of stabilizing UL136p33 on virus replication. No change in the kinetics or yield of viral growth was observed during the productive infection in fibroblasts when UL136p33 is stabilized relative to the WT infection (Fig. 2C). This result was not surprising since the UL136p33 isoform, while important for replication in endothelial cells and CD34+ HPCs, is dispensable for replication in fibroblasts (21, 22). In summary, UL136p33 instability is the result of lysine-dependent proteasomal degradation, and mutating lysine residues to arginine in UL136 stabilizes the protein with no effect on virus replication in fibroblasts.

Since UL136p33 is required for reactivation from latency in CD34+ HPCs (21), we hypothesized that the instability of UL136p33 allows for a tunable concentration gradient where low levels are important for the establishment of latency and accumulation past a threshold is important for reactivation. To test this hypothesis, we performed a latency assay in primary human CD34+ HPCs infected with the parental UL136myc or UL136mycΔK→R viruses. UL136myc-infected CD34+ HPCs generated >2-fold frequencies of infectious centers following reactivation compared with the prereactivation control (Fig. 2D). However, the pre- and postreactivation frequencies of infectious centers were not different in the UL136mycΔK→R infection and were almost 2-fold above UL136myc prereactivation. These results indicate that HCMV replication in CD34+ HPCs is not quieted when UL136p33 is stabilized and that this virus does not establish a latent infection. In a separate study, we have shown that the stabilization of UL136p33 results in increased virus replication (a failure to establish latency) in a humanized mouse model of latency (37). As is often the case with HCMV proteins, UL136 isoforms, even with a myc epitope tag, are not expressed to detectable levels in hematopoietic cells, and we have been unsuccessful in generating antibodies to UL136. Nevertheless, given the requirement for UL136p33 for reactivation and replication in CD34+ HPCs, the UL136mycΔK→R infection phenotype is consistent with the accumulation of UL136p33 beyond a threshold critical for commitment to replication.

The host E3 ligase IDOL targets UL136p33 for proteasomal degradation.

Ubiquitination of cargo by E3 ligases is an important step in targeting a protein for proteasomal degradation (38, 39). Because UL136p33 is rapidly turned over by the proteasome even in the absence of infection and lysine-to-arginine substitutions stabilized UL136p33, we hypothesized that a host E3 ligase targets UL136p33 for turnover. We identified UL136-interacting proteins by a yeast two-hybrid screen (Y2H) using the C-terminal region of UL136 (amino acids 141 to 240) as bait. Intriguingly, we identified the host E3 ligase inducible degrader of low-density lipoprotein receptor (IDOL), also known as MYLIP, as a candidate host interactor of UL136 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). IDOL induces the degradation of the low-density lipoprotein receptor family members LDLR, VLDLR, and ApoER-2 (35, 36). The degradation of these receptors is a physiological response to increased cholesterol, which is modified to oxysterols that activate the LXR transcription factor to induce IDOL expression (36, 40, 41).

To determine if IDOL targets UL136p33, we analyzed the ability of IDOL to interact with and impact UL136p33 levels. We validated the interaction between IDOL and UL136p33 by immunoprecipitating (IP) UL136p33-IDOL complexes from cells transiently overexpressing myc-tagged UL136p33 or hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged IDOL. Transient overexpression is necessary due to the lack of commercially available antibodies specific and sensitive enough to detect or immunoprecipitate endogenous IDOL. Pulldown of IDOLHA or p33myc coprecipitated the alternant partner (Fig. 3A), confirming the interaction between UL136p33 and IDOL. Further analysis indicated that coexpression of IDOL with UL136p33 resulted in an ~60% reduction in UL136p33 levels compared with that when UL136p33 was coexpressed with an empty vector (Fig. 3B, top, and quantified in Fig. 3C), consistent with IDOL driving UL136p33 turnover. In contrast, p33ΔK→R levels were not affected by IDOL coexpression (Fig. 3B, bottom, and quantified in Fig. 3C). Taken together, IDOL functions as a host E3 ligase that targets UL136p33 for proteasomal degradation.

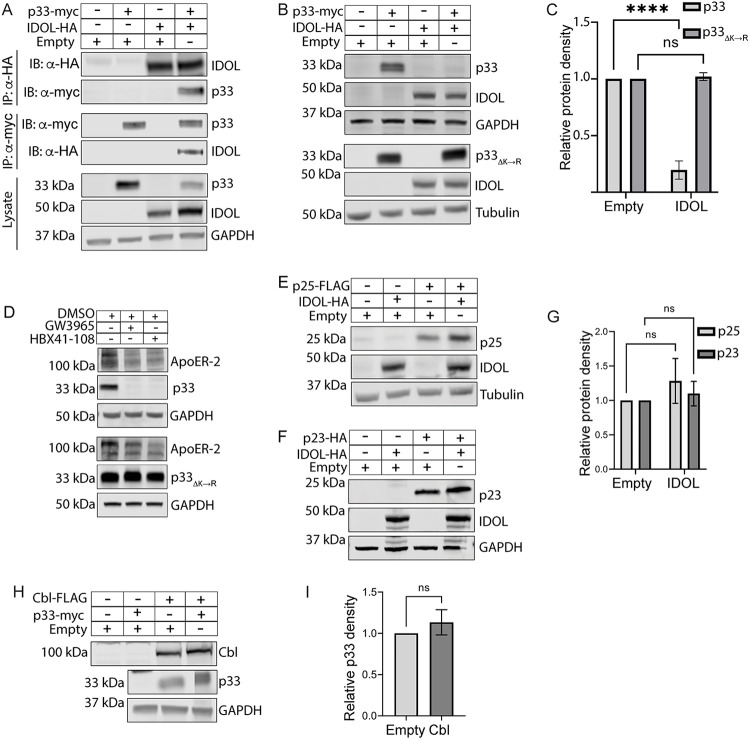

FIG 3.

The host E3 ligase IDOL specifically targets UL136p33 for turnover. (A) HEK 293T cells were transiently transfected with plasmids expressing UL136p33, IDOL, empty vector, or the indicated combinations. UL136p33 or IDOL was immunoprecipitated from protein lysates using α-myc or α-HA magnetic beads, respectively. Protein was detected by immunoblotting using the antibodies indicated. Lysates were blotted as a control for expression and GAPDH used as a loading control. (B) HEK cells were transiently transfected with plasmids expressing p33ΔK→R, IDOL or empty vector. Proteins were detected by immunoblotting using α-myc or α-HA monoclonal antibodies. (C) Protein densities of UL136p33 (from A) or p33ΔK→R (from B) were normalized to their loading control and are shown relative to each empty vector control. (D) HEK cells were transiently transfected to express UL136p33 or p33ΔK→R. IDOL was induced 48 h later with 2 μM LXR-agonists, GW3965 or HBX41-108, or vehicle (DMSO) for 6 h. Detection of ApoER-2 was used as a proxy for validating the induction of IDOL. p33myc, p33K→R, and tubulin as a loading control were detected by immunoblotting using α-myc or α-tubulin. (E to G) HEK 293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing IDOL, p25, or empty vector (E) or IDOL, p23, or empty vector (F). Proteins detected by immunoblotting using antibodies to FLAG or HA to detect the indicated proteins. Tubulin or GAPDH were used as loading controls for normalization. (G) Relative p25 or p23 densities. (H) HEK 293T cells were cotransfected with plasmids expressing UL136p33, the E3 ligase Cbl, or empty vector. Proteins were detected by immunoblotting using antibodies to the myc epitope tag or Cbl. (I) Relative UL136p33 densities were measured and quantified. All data points represent the mean of at least 3 independent replicates, and the means were compared by two-way ANOVA with a Tukey post hoc test. Error bars represent standard deviation. ns, nonsignificant P > 0.05; ****, P < 0.0001.

We next induced endogenous IDOL expression with the LXR agonist GW3965 or LXR-independent agonist HBX41-108 in cells transiently expressing UL136p33 or p33ΔK→R. Because endogenous IDOL cannot be detected by Western blot using available antibodies (34, 42, 43), the induction of IDOL was verified by the loss of its target ApoER-2 (Fig. 3D). Induction of IDOL, by both GW3965 and HBX41-108, resulted in a reduction of UL136p33 (Fig. 3D, top) but not p33ΔK→R (Fig. 3D, bottom). These results further support that endogenous IDOL targets UL136p33 for ubiquitin-dependent degradation.

The Y2H bait was composed of the C-terminal region of UL136 spanning amino acids 141 to 240 downstream of the predicted transmembrane domain. These residues are shared by all the UL136 isoforms (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, our data indicated that p25 and p23 proteins are also labile following CHX treatment and that these smaller isoforms could be rescued, like UL136p33, by inhibiting the proteasome (Fig. 1B, right). The p25 and p23 isoforms have a single lysine which is located downstream of the TMD in the full-length UL136 isoform (Fig. 1A). Transient coexpression of IDOL with either p25 or p23 did not lead to any notable turnover of these proteins (Fig. 3E to G). These data collectively led us to conclude that IDOL specifically targets UL136p33 for turnover, and it does not mediate the degradation of p25 and p23. The mechanism by which p25 and p23 are turned over remains to be elucidated and could reflect differential trafficking and localization of the proteins (22).

To further define the specificity of IDOL-mediated turnover of UL136p33, we coexpressed UL136p33 with another E3 ligase, Cbl. Cbl targets tyrosine kinase receptors, such as EGFR, for ubiquitination and subsequent degradation by the lysosome (44). Levels of UL136p33 were unaffected by coexpression with Cbl (Fig. 3H and I), indicating some specificity of IDOL for proteasomal turnover of UL136p33.

IDOL impacts UL136p33 protein levels in HCMV-infected primary fibroblasts.

In the context of a productive infection in fibroblasts, we found that infection with either the parental UL136myc or UL136mycΔK→R induced IDOL transcripts by at least 5-fold compared with mock infection by reverse transcriptase quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR), (Fig. 4A). IDOL transcript upregulation was sustained over time during infection and peaked at close to 10-fold by 3 days postinfection (dpi). No changes in IDOL transcript levels were detected in mock controls over the same time course. Because IDOL induction is a consequence of increased cellular cholesterol, we measured cholesterol content in infected cells to correlate it to the upregulation of IDOL transcripts. Using this approach, we noted that HCMV increased cholesterol concentration by at least 29% from 1 dpi onward (Fig. 4B), consistent with previous findings on HCMV modulation of lipid biosynthesis (45–50). Taken together, infection in fibroblasts upregulates expression levels of IDOL transcripts, which is correlated with increased intracellular cholesterol levels.

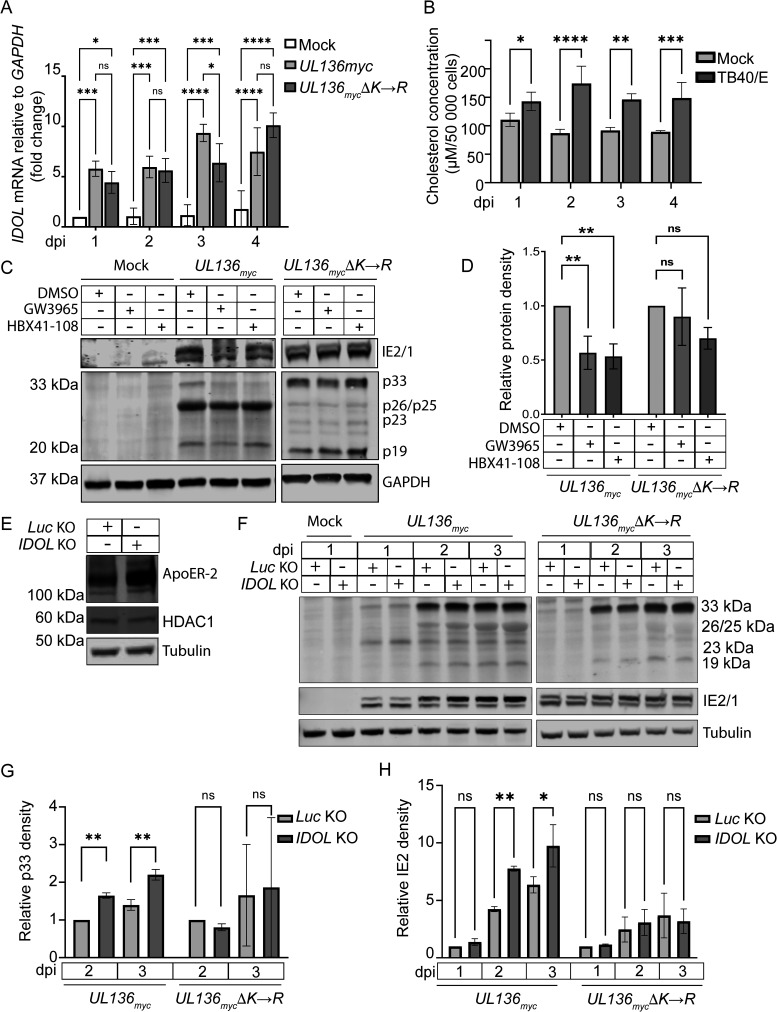

FIG 4.

IDOL expression in HCMV-infected fibroblasts impacts UL136p33 stability. (A) Fibroblasts were mock infected or infected with UL136myc or UL136mycΔK→R viruses at an MOI of 1, and total RNA was extracted at indicated time points. RT-qPCR was used to quantify relative IDOL transcripts using the ΔΔCT method. IDOL transcripts were normalized to GAPDH and compared with expression levels in mock samples at 1 dpi. (B) Fibroblasts were infected with TB40/E at an MOI of 1 followed by incubation in serum-free media. Cholesterol concentrations were measured and compared with mock-infected cells at 1 dpi. (C) Fibroblasts were mock infected or infected with UL136myc or UL136mycΔK→R viruses at an MOI of 1. At 2 dpi, IDOL expression was induced by treatment with 2 μM GW3965 or HBX41-108 for 6 h followed by Western blot evaluation of UL136p33 levels. Relative UL136p33 levels are quantified in D. (E) IDOL KO cell lysates were analyzed by Western blot to evaluate ApoER-2 expression levels compared with a Luc KO control. To evaluate CRISPR-Cas9 off-target effects, we measured HDAC1 in Luc or IDOL KO cell lysates. (F) UL136myc or UL136mycΔK→R viruses were used to infect either Luc or IDOL KO cells at an MOI of 1. Cell lysates were collected at indicated times and evaluated for UL136p33, IE1 and IE2 protein levels. (G) Quantification of p33 protein densities relative to the Luc KO at 2 dpi under each infection condition in panel F. (H) Quantification of IE2 protein densities relative to Luc KO at 2 dpi under each infection condition in panel F. Quantitative data points represent the mean of 3 independent replicates, and error bars represent standard deviation. Differences in the means were compared using two-way ANOVA with a Tukey post hoc test. ns, P > 0.05; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

To address the effect of HCMV-mediated induction of IDOL on UL136p33 levels in a productive infection, we again induced IDOL expression with the LXR agonist GW3965 or HBX41-108 in TB40/E-UL136myc- or TB40/E-UL136mycΔK→R-infected fibroblasts. IDOL induction resulted in a 50% reduction in the levels of UL136p33 but did not significantly affect p33ΔK→R levels (Fig. 4C; quantified in Fig. 4D). Diminished levels of smaller UL136 isoforms are again apparent in the UL136mycΔK→R infection. We next disrupted IDOL expression in fibroblasts to answer the question whether IDOL depletion would rescue UL136p33 turnover. CRISPR-mediated knockout (KO) of IDOL using guide RNAs to disrupt all the isoforms of IDOL was validated by Sanger sequencing and increased ApoER-2 as a proxy for IDOL KO (Fig. 4E). Furthermore, CRISPR KO of IDOL had no effect on HDAC1, a potential off-target hit when knocking out IDOL. In fibroblasts depleted of IDOL, UL136p33 levels increased at 2 and 3 dpi compared with luciferase KO controls but did not affect levels of p33ΔK→R (Fig. 4F; quantified in Fig. 4G). Furthermore, IE2 levels were also significantly increased in IDOL KO cells infected with UL136myc, but they were not changed by IDOL KO in the UL136mycΔK→R infection (Fig. 4H). Together, these results indicate that IDOL regulates UL136p33 concentration, which indirectly impacts IE expression in the context of infection.

LXR induction and IDOL restrict HCMV gene expression and reactivation in models of latency.

HCMV latency is studied in a variety of models. Due to limitations inherent to each model, there is no perfect model. Therefore, we explore latency questions using multiple complementary models. To explore the role of IDOL in regulating UL136p33 levels in latency and reactivation, we have used two models of HCMV: (i) a THP-1 cell line model and (ii) a CD34+ primary HPC model. In the THP-1 monocytic cell line model, cells are infected in an undifferentiated state for the establishment of latency. Viral gene expression is detected early (1 dpi) following infection but is silenced as the virus establishes a latent-like state (51). Re-expression of viral genes for reactivation is stimulated by differentiating the cells into macrophages with a phorbol ester, tetradecanoylphorbol acetate (TPA) (51–56). This model is a strong one for looking at transcriptional changes associated with latency and reactivation; however, this model is limited in that THP-1 cells do not robustly or consistently support viral genome synthesis or production of viral progeny following TPA induction, which is a requirement for bona fide reactivation. The gold standard for HCMV latency is the ability of the virus to establish and reactivate from latency in primary human CD34+ HPCs (57). In contrast to THP-1 cells, the primary CD34+ HPC model supports viral genome synthesis and the formation of infectious progeny in response to reactivation. However, the model is limited by substantial donor variability associated with primary human cells, heterogeneity of the population, the availability of cells in numbers to provide sufficient starting material for many assays, and the ability to manipulate these cells (e.g., gene knockdowns or overexpression) without affecting their differentiation or quantities sufficient for HCMV infection assays. Furthermore, because reactivation of HCMV from CD34+ HPCs occurs at low frequency (1 in ~9,000 cells), an analysis of molecular events associated with reactivation is challenging. The use of both models yields complementary insights into the patterns of gene expression upon infection or reactivation (THP-1) and virus production (CD34+ HPCs) to understand latency and reactivation.

Dynamic gene expression changes are associated with monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation (32, 58, 59). Because IDOL is highly expressed in bone marrow (60), we hypothesized that IDOL expression may be dictated by the differentiation state of the cell and would regulate UL136 levels in a differentiation-dependent manner. Indeed, we found that IDOL was highly expressed in undifferentiated THP-1 monocytes prior to infection but was sharply downregulated upon THP-1 cell differentiation (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, while no significant differences in IDOL expression were observed between uninfected cells and UL136myc infection, UL136mycΔK→R infection significantly reduced IDOL expression in the undifferentiated, latent phase (Fig. 5A). This result suggests that UL136p33 levels may feed back to impact IDOL expression in a cell type-dependent manner, as this was not observed in fibroblasts (Fig. 4A).

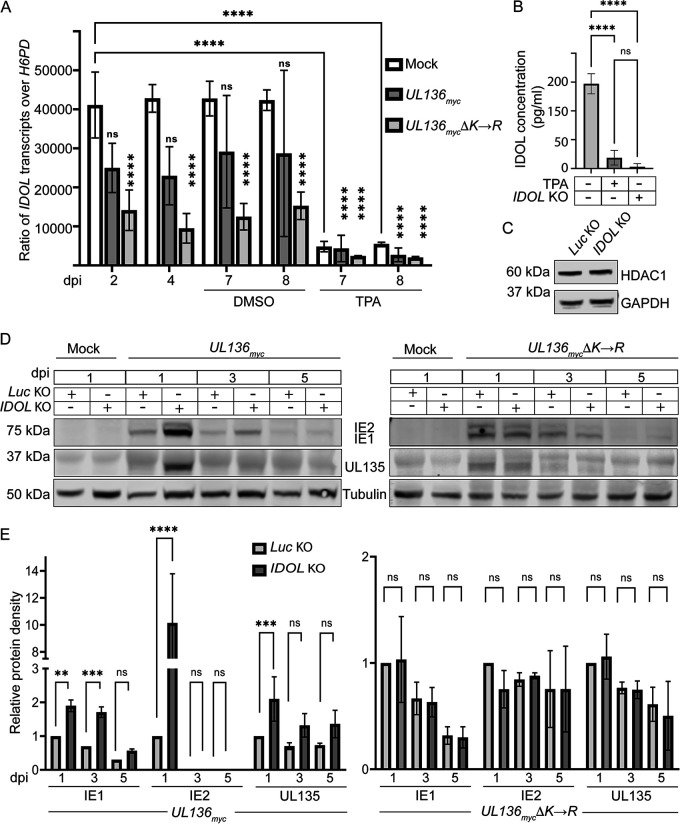

FIG 5.

IDOL impacts viral protein expression in a THP-1 cell latency model. (A) THP-1 cells were mock infected or infected with UL136myc or UL136mycΔK-->R at an MOI of 2. At 5 dpi, cells were treated with TPA to induce differentiation or the vehicle control (DMSO). Total RNA was extracted from mock-, UL136myc-, or UL136mycΔK→R-infected THP-1 cells at indicated time points. cDNA was synthesized from the RNA and RT-qPCR was used to determine the relative expression levels of IDOL transcripts compared with the low-copy cellular housekeeping gene H6PD using the ΔΔCT method. (B) Validation of IDOL KO in undifferentiated THP-1 cells was confirmed by ELISA. Where indicated, cells were treated with TPA as a positive control for the loss of IDOL. (C) Immunoblot of HDAC1 in Luc control or IDOL KO THP-1 cells to rule out off-target CRISPR-Cas9 effects. (D) IDOL or Luc KO THP-1 cells were infected with TB40/E-UL136myc (left) or TB40/E-UL136mycΔK→R (right) at an MOI of 2, and cell lysates were collected at indicated time points. IE1/2 and UL135 accumulation was evaluated by immunoblotting protein lysates over a time course using a monoclonal α-IE1/2 and polyclonal α-UL135. (E) IE1, IE2, and UL135 were quantified, and levels were normalized to Tubulin and are shown relative to levels present at 1 dpi in the Luc KO control for UL136myc and UL136mycΔK→R infections. Note that comparisons were made between Luc KO and IDOL KO, not between UL136myc and UL136mycΔK→R infections. All data points are representative as the mean 3 independent replicates, and error bars represent standard deviation. The means were compared by two-way ANOVA with a Tukey post hoc test. ns, P > 0.05; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

To determine how IDOL impacts HCMV infection in hematopoietic cells, we knocked out IDOL in THP-1 cells using CRISPR. The knockdown was validated using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for the detection of the IDOL protein (Fig. 5B); the IDOL protein was reduced in undifferentiated cells to levels induced by differentiation. Furthermore, the IDOL KO had no off-target effects on HDAC1 (Fig. 5C). Given the challenges of detecting UL136 isoforms, particularly in hematopoietic cells, we examined IE1, IE2, and UL135 gene expression as proxies for determining the effect of IDOL KO on infection in THP-1 cells. UL135 and IE1/2 proteins are detected early during infection in THP-1 cells but diminish as the virus establishes latency between 3 and 5 dpi (Fig. 5D; quantified in Fig. 5E) (51). The IDOL KO resulted in an increased initial burst in the expression of IE1, IE2, and UL135 at 1 dpi relative to control Luc KO cells in the UL136myc infection. Notably, the major HCMV transactivator IE2 was detected in UL136myc infection under the IDOL KO condition but not in the Luc KO control. The increased viral gene expression in the IDOL KO is consistent with increased viral activity. However, gene expression was still relatively quieted by 5 dpi, suggesting that the induction of IDOL does not fully prevent the silencing of viral gene expression in this system and that other viral or cellular factors are required. As we have never identified a condition or mutant virus that is not ultimately silenced in THP-1 cells, this finding is not unexpected and it may reflect the robust program for restriction and silencing in THP-1, indicated by the inability of these cells to support viral DNA synthesis and progeny formation even with TPA treatment. UL135 and IE1, as well as IE2, were detected in UL136mycΔK→R infection of THP-1 cells. Importantly, IDOL KO had no effect on IE1, IE2, or UL135 expression in UL136mycΔK→R infection (Fig. 5D; quantified in Fig. 5E), consistent with a role for IDOL in regulating the establishment of latency by targeting UL136p33 for turnover. In contrast to UL136myc infection, IE2 was detected under all conditions of the UL136mycΔK→R infection and is not increased further by IDOL KO. While a potent transactivator, IE2 feeds back to negatively regulate the major immediate early promoter and its own expression (61–64). The differences in IE expression in IDOL KO in UL136myc and UL136mycΔK→R infection may reflect complexities in the regulation of IE gene expression or the possible dysregulation and loss of middle UL136 isoforms in UL136mycΔK→R infection (Fig. 2). Further work is required to understand this relationship. These results indicate that the loss of IDOL increases viral gene expression in UL136myc infection at least at early times following the infection of THP-1 cells, suggesting a role for IDOL in regulating HCMV infection in undifferentiated THP-1 cells. This finding reflects IDOL-induced changes in UL136p33 since the stabilized variant does not differentially express genes in an IDOL-dependent manner. These findings are further consistent with a role for IDOL in driving the instability of UL136p33 and the role of UL136p33 in driving HCMV replication in hematopoietic cells (21). Further, these data indicate that UL136p33 may negatively regulate IDOL expression in hematopoietic cells, as the stabilized form of UL136p33 results in greater repression of IDOL transcripts by HCMV infection.

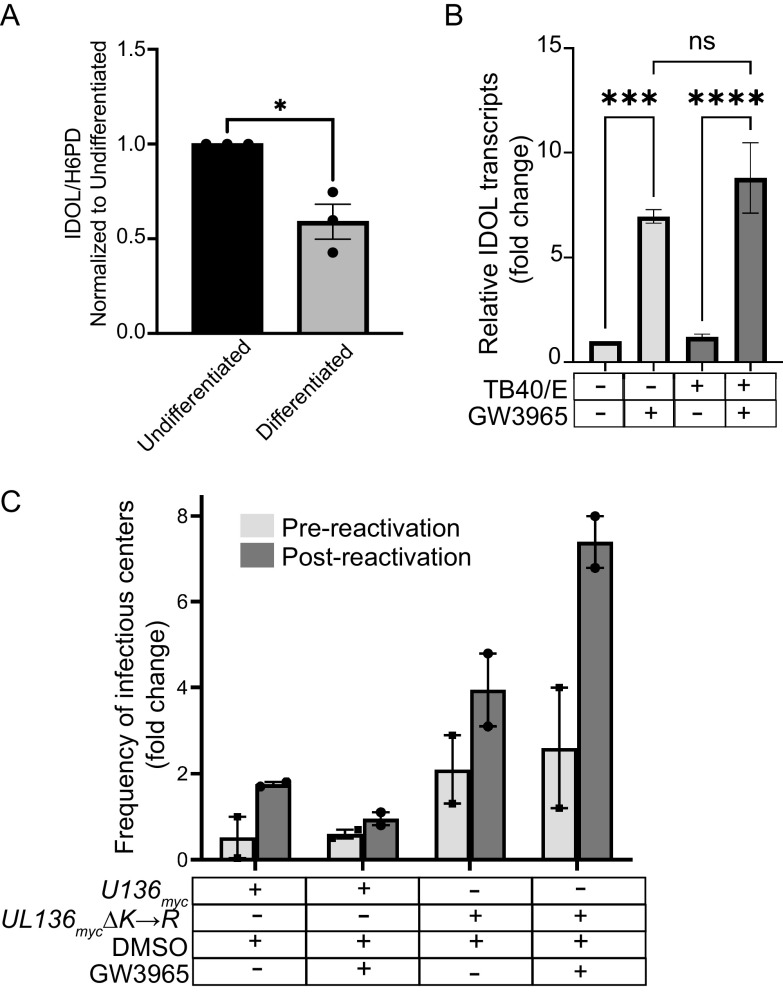

To further explore the importance of IDOL in latency, we turned to the primary CD34+ HPC experimental model (57). IDOL is expressed in undifferentiated CD34+ HPCs, and similar to our findings in the THP-1 cell model, its expression is downregulated by differentiation (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, the LXR-agonist GW3965 induces IDOL expression in either infected or uninfected CD34+ HPCs (Fig. 6B). To measure the impact of LXR induction on reactivation in primary CD34+ HPCs, we isolated CD34+ HPCs infected with TB40/E-UL136myc or TB40/E-UL136mycΔK→R (green fluorescent protein + [GFP+]) by fluorescence-activated cell sorting and seeded the cells into long-term bone marrow cultures. To analyze infectious virus production, infected CD34+ HPC cultures were split at 10 dpi. Half the cells were seeded by limiting dilution into co-culture with fibroblasts and cytokine-rich media to stimulate reactivation from latency. The other half was mechanically lysed, and lysates were seeded by limiting dilution onto fibroblast monolayers to determine the virus present prior to reactivation (pre-reactivation). Relative to the dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) control, GW3965 treatment restricted UL136myc reactivation (Fig. 6C), consistent with a requirement for accumulation of UL136p33 for reactivation. In contrast, UL136mycΔK→R did not establish latency, and LXR induction did not restrict replication of UL136mycΔK→R. Given the limited availability of human CD34+ HPCs, data from two independent donors are shown for Fig. 6C. These results are consistent with the model that IDOL restricts virus reactivation in a manner dependent on its ability to turnover UL136p33 since LXR induction has no effect on the infection of UL136mycΔK→R. Taken together with the THP-1 experiments, these results suggest that IDOL-driven UL136p33 instability is required for latency and that induction of IDOL suppresses reactivation, presumably through suppressing the accumulation of UL136p33 (Fig. 7).

FIG 6.

Induction of IDOL in CD34+ HPCs inhibits reactivation. (A) CD34+ HPCs were cultured for 5 days in media with cytokines to stimulate differentiation or were left undifferentiated. RNA was isolated, and transcripts encoding IDOL were quantified by RT-qPCR relative to the H6PD housekeeping gene using the ΔΔCT method. Values were normalized to the undifferentiated population and graphed for statistical analysis. Statistical significance was calculated using unpaired Student’s t test and represented by asterisks. Graphs represent the mean of three replicates, and error bars represent SEM. (B) CD34+ HPCs were mock- or TB40/E-infected at an MOI of 2. At 1 dpi, cells were treated with 1 μM GW3965 for 6 h, and total RNA isolated for qPCR was used to measure IDOL transcript levels relative to H6PD. The data points represent the mean from 3 independent experiments. The means were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with a Tukey post hoc test. ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. (C) CD34+ HPCs were infected at an MOI of 2. At 24 hpi, infected CD34+ cells were isolated by FACS and seeded into long-term culture. GW3965 (1 μM) was added to induce IDOL at the time of reactivation. At 10 days, half of the culture was reactivated by seeding intact cells by limiting dilution into coculture with fibroblasts in a cytokine-rich medium to promote myeloid differentiation (reactivation). The other half of the culture was mechanically lysed and seeded onto fibroblasts as the prereactivation control. The frequency of infectious centers was determined for each sample by extreme limiting dilution assay (ELDA). The data points represent replicates from 2 independent donors, and the range is indicated.

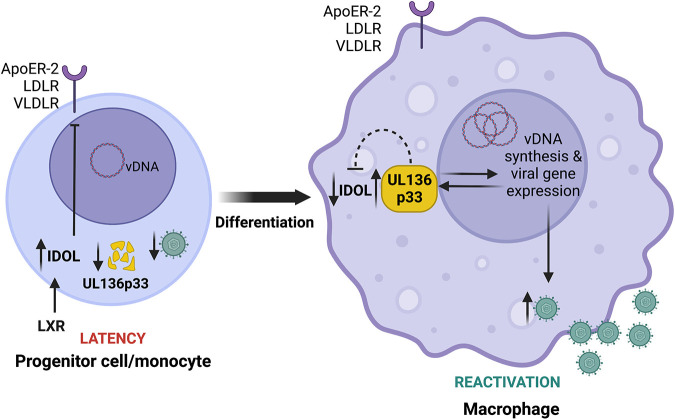

FIG 7.

Model for differentiation-dependent IDOL regulation to control UL136p33 levels. Progenitor cells are relatively small and intolerant of high cholesterol, which they control, in part, through the expression of IDOL to reduce cholesterol/lipid uptake. We propose that high levels of IDOL maintain low levels of UL136p33 to restrict HCMV replication for the establishment of latency following infection. Upon cell differentiation, the downregulation of IDOL is observed and is expected to correspond to an increased accumulation of UL136p33 to drive reactivation and replication, consistent with our finding that depletion of IDOL increases HCMV gene expression and that an LXR agnonist restricts reactivation. We have shown previously that UL136p33 levels further accumulate in late phase upon the commitment to viral DNA synthesis. Therefore, following reactivation, we postulate that UL136p33 levels increase due to a combination of decreased turnover and increased synthesis. Furthermore, because stabilization of UL136p33 results in a corresponding downregulation of IDOL expression, UL136p33 may feed back to suppress IDOL gene expression. This work implicates IDOL as a host factor that fine tunes levels of UL136p33 to control decisions to enter and exit latency. UL136p33 acts as a sensor at the tipping point between the decision to maintain the latent state or exit latency for reactivation where its instability is critical for the establishment or latency and its accumulation critical for reactivation. This study suggests that LXR signaling and cholesterol homeostasis may impact HCMV latency and reactivation and will be explored in future studies. The figure was created with Biorender.com.

DISCUSSION

Latent viruses require mechanisms to sense the cellular environment, filter noise, and respond to host cues to maintain a quiescent latent state or to reactivate replication (1). While the decision to enter or exit latency is often depicted as a simple binary on/off switch, the reality is more likely that a number of successive checkpoints must be crossed, each requiring thresholds in viral or cellular activities to be reached in making the commitment to productive reactivation. Developing strategies to control entry into or exit from HCMV latency and ultimately control CMV disease rests upon identifying virus-host interactions that govern the decisions around latency and reactivation. Here, we demonstrate the existence of an unstable viral determinant of reactivation, UL136p33 (Fig. 1), and that its instability is important for the establishment of latency in CD34+ HPCs (Fig. 2). We demonstrate that its instability is dependent upon a host E3 ligase, IDOL, which is regulated by hematopoietic differentiation (Fig. 3). Knockdown of IDOL levels increases viral gene expression (Fig. 4 and 5) and LXR induction restricts replication in hematopoietic models of latency (Fig. 6). Our results support a model, which is rich in hypotheses for further investigation, whereby UL136p33 is maintained at low levels for the establishment of latency in undifferentiated because IDOL levels are high (Fig. 7). Upon differentiation, IDOL levels fall (Fig. 5A and 6A), allowing UL136p33 levels to rise, which facilitates HCMV crossing at least one threshold toward reactivation. UL136p33 accumulation is amplified and re-enforced by the onset of viral DNA synthesis and entry into late phase (22), and high levels of UL136p33 further suppress IDOL expression (Fig. 5A). These findings define novel virus-host interactions that govern entry into and exit from latency. Moreover, these findings suggest that by utilizing IDOL to regulate levels of a critical viral determinant for reactivation, the virus evolved to hardwire this decision into LXR signaling, which ultimately controls IDOL levels. Future work will define the mechanisms by which UL136 regulates HCMV infection and commitment to replication in hematopoietic cells. Understanding the relationship between UL136 isoforms and other UL133-UL138 locus-encoded proteins and host interactors will be critical to mechanistic insights.

IDOL is transcriptionally upregulated by excess cholesterol derivatives (oxysterols) that are sensed by LXR in a cell type-dependent manner (36, 65–68). RNA sequencing to classify the tissue-specific expression of genes across a representative set of all major human organs and tissues revealed that IDOL is highly expressed in the bone marrow, where CD34+ HPCs and monocytes are generated (69). The level of IDOL expression in the bone marrow is only second to that in the placenta. High expression of IDOL in undifferentiated progenitor cells (Fig. 6A) or in monocytes (Fig. 5A) suggests they are intolerant of high cholesterol levels. Consistent with this finding, undifferentiated THP-1 monocytes express significantly higher levels of cholesterol efflux genes, such as CES1, and express significantly lower levels of influx genes (70). In contrast, THP-1 monocyte-derived macrophages upregulate cholesterol influx genes, such as scavenger receptor A1 (SR-A1) and CD36, to become lipid-loaded macrophages or foam cells. Furthermore, statin treatment to lower cholesterol reduces CD34+ HPC populations in the circulation and high cholesterol promotes CD34+ HPC proliferation, myelopoiesis, and monocyte and granulocytic differentiation (71–73). While carefully designed studies are required to understand how statins specifically affect HCMV latency and/or reactivation, these findings suggest the possibility that sterol homeostasis impacts HCMV latency and reactivation. Untreated hypercholesterolemia might lead to increased hematopoietic differentiation and a higher frequency of HCMV reactivation events, whereas statin treatments may restrict HCMV reactivation and replication. Given the role demonstrated here for IDOL in the regulation of UL136p33 expression, the high levels of IDOL expression make progenitor cells an ideal environment for HCMV latency in which UL136p33 is suppressed by rapid turnover. It is intriguing to speculate a possible role of UL136p33 as a viral sensor of changes in LXR signaling compatible with reactivation.

HCMV infection remodels the cellular lipid metabolic landscape by upregulating de novo cholesterol biosynthesis during a productive infection (46, 49, 50). It is, therefore, expected that HCMV infection would induce IDOL expression during a replicative infection. While IDOL and cholesterol are induced by infection in fibroblasts (Fig. 4A and B), IDOL expression was not induced by infection in hematopoietic cells. In fact, IDOL expression was downregulated by UL136mycΔK→R infection (Fig. 5A). This disparity in the regulation of IDOL likely reflects cell type-specific differences, including tolerance for cholesterol and differences in the nature of the infection in each cell. While cholesterol increases in macrophage cells, they also have higher tolerance to cholesterol than HPCs or monocytes (74–76). Accordingly, despite increased cholesterol in macrophages, IDOL levels are strikingly downregulated in THP-1 cells induced to differentiate with TPA (Fig. 5A) or CD34+ HPCs are induced to differentiate with cytokines (Fig. 6A).

IDOL recognizes a conserved FERM domain (WxxKNxxSI/MxF) within the cytoplasmic tail of its targets (ApoER-2, LDLR and VLDLR) to mediate ubiquitination for lysosomal degradation (31, 35, 36, 77). Canonical IDOL targets reside at the plasma membrane and are typically internalized via the endocytosis and trafficked to the lysosome (77). In contrast, UL136p33 is predominantly Golgi associated (22), lacks a FERM domain, and is degraded via the proteasome (Fig. 1B). Differences in localization and trafficking pathways between natural IDOL targets and UL136p33 may differentially direct the degradation pathway. It remains to be determined how IDOL recognizes and targets UL136p33, but it is possible that the two proteins interact indirectly.

Activation of LXR in human foreskin fibroblasts with GW3965 prior to HCMV infection has been shown to depress expression levels of viral proteins, such as IE2, pp28, pp65, and gB (78). GW3965 treatment is also reported to induce interferon gamma (IFN-γ) (79), which is a cytokine that directly inhibits IE1/2 mRNA expression (80). These findings suggest the possibility that the effects of LXR agonists on UL136p33 levels are due to a global repression of viral gene expression. However, our results argue against this scenario. First, we observed no effect on IE gene expression at 2 dpi in infected fibroblasts treated with GW3965 or HBX41-108 (Fig. 4C and D), consistent with the attenuation of IFN-γ at later times (81). Second, specific depletion of IDOL increases UL136p33, consistent with IDOL-specific effects on UL136p33 levels. Nevertheless, to avoid this potential pitfall, we treated cells in our experiments with these agonists following the establishment of infection and IE gene expression in our studies.

The LXR axis is important for the biology of other herpesviruses. A recent report demonstrates that the alphaherpesvirus pseudorabies virus (PRV), the etiologic agent of the economically important Aujeszky’s disease, has evolved to inhibit LXR at both transcription and protein levels (82). Using an inverse LXR agonist SR9243, Wang and colleagues (82) showed that inhibiting LXR increased PRV replication, whereas 3 different LXR agonists and the oxysterol 22R-hydroxycholesterol all inhibited PRV replication. However, PRV can be rescued from the suppressive effects of an LXR agonist by supplementing it with cholesterol (82), consistent with a viral need for cholesterol to replicate. LXR also inhibits the murine gammaherpesvirus MHV68 as it replicates better in LXR−/− macrophages and, contrary to PRV, MHV68 infection increases LXRα (83). Importantly, LXRα restricts reactivation of MHV86 in peritoneal cells but not in splenocytes (84). The cell type-dependent role of LXR signaling for reactivation suggests the possibility that a LXR signaling might control a MHV68 determinant of reactivation in peritoneal cells that is dispensable in splenocytes. Similarly, disruption of or stabilization of UL136p33 has no impact on replication in fibroblasts (Fig. 2C) (22) but impacts replication in HPCs (Fig. 2D) and endothelial cells (21). Viral factors encoded by MHV68 and regulated by LXR signaling have yet to be determined.

In addition to herpesviruses, LXR signaling suppresses the replication of other viruses, including hepatitis C virus (HCV) (85, 86), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (87–89), and Newcastle disease virus (NDV) (90). Intriguingly, activation of LXR signaling suppresses HCV replication in an IDOL-dependent manner. The suppression of HCV is presumably due to the requirement for LDLR as an entry receptor since once infection is established, IDOL induction does not seem to have an effect on HCV replication (85). However, there are mixed reports on the requirement for LDLR for HCV entry or its specific function in HCV replication (91–93).

While many host pathways are implicated in the regulation of herpesvirus latency, the interplay between viral determinants and their regulation by host mechanisms to terminate activity is less well appreciated, particularly for HCMV. The expression of herpes simplex virus type-1 (HSV-1) ICP0, a critical protein for reactivation and replication, is suppressed by the host neuronal microRNA-138 to facilitate latency (94, 95). Moreover, ICP0 was shown recently to be regulated by the host E3 ligase TRIM23, which is, in turn, countered by the HSV-1 late protein γ134.5 (96). While speculative, TRIM23 may moderate ICP0 protein levels for latency, where γ134.5 ensures the commitment to replication by blocking TRIM23-mediated turnover of ICP0. Furthermore, the E3 ubiquitin ligase MDM2 restricts levels of the Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) transactivator RTA/ORF50, acting as a proviral factor for latency (97). RTA/ORF50 in turn induces the degradation of vFLIP through the host Itch E3 ubiquitin ligase to attenuate vFLIP-driven NF-κB signaling for reactivation (98, 99). Co-opting and regulating host E3 ligases to target viral proteins for latency allow infections to respond quickly to host cues (e.g., prior to changes requiring transcription of genes and translation of proteins) for reactivation. Furthermore, it will be important to determine if UL136p33 feeds back to regulate IDOL expression based on the observation that the stabilization of UL136p33 represses IDOL expression in undifferentiated THP-1 cells (Fig. 5A). It will be important to further define the mechanisms by which UL136p33 interacts with host pathways to impact viral gene expression and promote context-dependent reactivation and replication.

The evolution of viruses to depend on host factor-mediated turnover of critical viral determinants is shared across highly divergent systems. Bacteriophages establish a dormant lysogenic state to cope with their variable and unpredictable environment (100). Bacteriophage λ lysogeny depends on the competition between repressors and activators of gene expression that serve as a gatekeeper for the lytic pathways (101, 102). As a primary example, competitive binding of the lysogeny determinant CI and the immediate early gene Cro at regulatory operator elements puts CI-Cro at the heart of a bistable switch controlling lysogenic-lytic decisions. Another determinant, CII, is expressed with later kinetics and is also critical to the commitment to lysogeny (103, 104). CII promotes expression of CI while it represses expression of the antiterminator Q, which must accumulate to a threshold to drive lytic gene expression. Critical effectors in bacteriophage lysogeny, such as CI and CII, are susceptible to destruction by host proteases that are induced in response to stresses, such as DNA damage (105, 106). Similar to the model emerging for the UL136-IDOL interaction in regulating a determinant of reactivation for latency, the decision to establish lysogeny depends on the accumulation of lysogenic effectors and is responsive to host determinants regulated by environmental cues. Furthermore, while CI is robust, the expression of CII, like UL136, is sensitive to genome copy number or other fluctuations in the system, providing additional checkpoints in regulating the decision.

With respect to the system emerging for HCMV, the UL133-UL138 locus coordinates the expression of multiple genes impacting infection fate decisions. While UL135 and UL138 are not known to directly regulate gene expression, their opposing impact on host EGFR/PI3K signaling (11, 18, 20) has parallels to the Cro-CI bistable genetic switch. Furthermore, UL136p33 is expressed with later kinetics than the UL135/UL138 determinants, and robust UL136p33 expression is dependent on crossing a threshold of commitment to viral DNA synthesis (22). In addition, UL136p33 is remarkably unstable compared with other UL133-UL138 genes and other UL136 isoforms, and as we have shown here, its instability is dependent differentiation-linked changes in IDOL expression. Although the UL136p33 protein is undetectable in THP-1 monocytes or hematopoietic cells, KO of IDOL increases the expression of genes critical for replication (e.g., IEs and UL135), and stabilization of UL136p33 results in a virus that replicates in the absence of a stimulus for reactivation in vitro (Fig. 2D) but also in a humanized mouse model of latency (37). While UL135 is critical for overcoming the repressive effects of UL138 for successful reactivation, we assert that the subsequent accumulation of UL136p33 beyond a threshold is also important for commitment to the replicative state (Fig. 7). It is important to understand (i) the relationship between UL135 and UL136p33 in the commitment to HCMV reactivation (37), as both are required for reactivation and (ii) how latency-promoting UL136p23/19 isoforms (21) may contribute to the establishment of latency or counter the progression toward reactivation to maintain a latent infection. This is a particularly intriguing question as the stabilization of UL136p33 not only affects levels of IDOL mRNA but also affects levels of other UL136 isoforms (Fig. 2B). Finally, these findings indicate that the LXR-IDOL axis may be a potential target for clinically controlling HCMV reactivation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast two-hybrid screen.

A yeast screen for human cellular interacting proteins of pUL136 was performed using the Matchmaker gold yeast two-hybrid system (Clontech) and the mate and plate universal human library (Clontech). This yeast two-hybrid universal library was constructed from human cDNA that has been normalized to remove high-copy-number cDNAs (overrepresented transcripts) to facilitate the discovery of low-copy-number novel protein-protein interactions. All protocols were carried out according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. Yeast dual transformation and yeast mating were performed according to established protocols from Clontech. Yeast prey vectors were isolated from Y187 yeast and subsequently transformed into DH10B Escherichia coli. After selection for E. coli containing yeast prey vectors, the plasmids were isolated and sequenced to identify interacting partners. Candidate interactors are listed in Table S1.

Cells and viruses.

Human primary embryonic fibroblasts (MRC-5; ATCC) and human kidney embryonic 293T (HEK 293T; ATCC) cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s essential medium (DMEM). The DMEM was supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 2 mM l-alanyl-glutamine, 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs) were isolated from deidentified medical waste following bone marrow isolations from healthy donors for clinical procedures at the Banner-University Medical Center at the University of Arizona (57). THP-1 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma).

The wild-type TB40E/05 strain expressing GFP as a marker for infection (107) was engineered to fuse the myc epitope tag in frame at the 3′ end of UL136 (UL136myc virus) using BAC recombineering as described previously (22). The UL136mycΔK→R virus was constructed following methods described previously (22). For the generation of UL136mycΔK→R, a UL136mycΔK→R pGEM-T Easy construct was created by site-directed Phusion mutagenesis according to the manufacturer’s instruction (New England BioLabs). Inverse PCR was used to mutagenize lysines 4, 20, 25, and 113 to arginine using the primers 5′-GACGTTGGAAATAGATGGCGGCGTCGAAGGCCCTGAGTCGC-3′ (forward) and CAAGTCCCACGTCATTTCTGGCATCTCCACGCCCCTGACTGACAT-3′ (reverse) for the first 3 lysine residues in the N-terminal region, and 4th lysine was mutagenized to arginine with the forward primer 5′-ACGAGCGGCAGAGAAGCAGACGGC-3′ and reverse primer GGTGCCGACGGCACCTCTCAGGATAATG-3′. Following verification by Sanger sequencing, a region of the UL136K-Rmyc pGEM-T Easy was PCR amplified from bp 854 of UL135 [UL135(bp854)] to UL138 (bp139). This PCR product was gel purified and recombined with a ΔUL136<GalK> BAC as described previously (22). BAC integrity was tested by enzyme digest fragment analysis and sequencing of the UL133/8 viral genomic region. All BAC genomes were maintained in Escherichia coli SW102, and viral stocks were propagated by transfecting 15 to 20 μg of each BAC genome, along with 2 μg of a plasmid encoding UL82 (pp71) into 5 × 106 MRC-5 fibroblasts, and subsequently purified and stored as described previously (22).

Immunoblotting.

Cells were washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Gibco) and lifted from cell culture vessels with 0.25× trypsin (Gibco). Cells were washed in cold PBS and pelleted at 1,000 × g for 2 min, followed by storage at −80°C before lysis in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer. Total protein was quantified using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay, and 50 μg of each sample was prepared for loading onto 12% precast PAGE gels (GenScript). Wet transfers were performed onto 0.45 μM pore-sized polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Immobilon). Blocking was achieved by 5% skimmed milk in 1× Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBST) or 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in 1× TBST. Primary and secondary antibodies used for Western blot analyses are indicated in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Antibodies used in this study

| Antibody name | Manufacturer | Catalog no. |

|---|---|---|

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-ApoER-2 | Abcam | ab108208 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-FLAG tag | Sigma-Aldrich | F7425 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-GAPDH (clone D16H11) | Cell Signaling Technology | 5174 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-HA tag | Sigma-Aldrich | H6908 |

| Mouse HDAC1 (clone 10E2) | Santa Cruz Biotech | sc-81598 |

| IE1/2 (3H4) | Princeton University/Tom Shenk | N/Aa |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-Myc tag (clone 71D10) | Cell Signaling Technology | 2278 |

| Tubulin (clone DM1A) | T6199 | |

| UL135 | Open Biosystems | Custom antibody |

| Goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (IR Dye 680) | LI-COR Biosciences | 926-68070 |

| Goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (IR Dye 800) | LI-COR Biosciences | 926-32211 |

N/A, not applicable.

RT-qPCR assays.

Cells were washed twice in cold PBS and lysed in 400 μL of RNA/DNA lysis buffer (Zymo Research). Total cellular RNA was extracted according to the manufacturer’s protocol for Quick-DNA/RNA minipreps. cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of DNase-treated RNA using the Vilo cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Quantitative PCRs (qPCRs) were prepared with the IDOL TaqMan assay (ID Hs00982312_m1; ThermoFisher Scientific), Platinum quantitative PCR SuperMix-UDG w/ROX (ThermoFisher Scientific), and 50 ng cDNA. qPCRs were run in a QuantStudio 3 real-time PCR machine (Applied Biosystems). Gene expression was normalized to GAPDH (Hs01922876_u1) or H6PD (Hs00188728_m1), and the cycle threshold (ΔΔCT) method was used to calculate relative gene expression levels (108, 109). Alternatively, cDNA was quantified using a LightCycler SYBR mix kit (Roche) and corresponding primers to IDOL (Biorad PrimePCR primers) and H6PD (forward, 5′-GGACCATTACTTAGGCAAGCA-3′; reverse, 5′-CACGGTCTCTTTCATGATGATCT-3′). Assays were performed on a Light Cycler 480 instrument and corresponding software. Relative expression was determined using the ΔΔCT method normalized to H6PD.

Coimmunoprecipitation.

Cells were washed twice with PBS and trypsinized. The PBS-washed cell pellet was lysed on ice for 30 min in a lysis buffer made of 100 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.4), 100 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaFl, and 0.5% NP-40. The complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) was added to the lysis buffer according to manufacturer recommendations. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C. One milligram of the lysate was incubated with Pierce anti-myc or anti-HA magnetic beads for 1 h at 4°C. The beads were washed 3 times and the protein eluted according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

CRISPR-CAS9-mediated knock out of IDOL.

Guide RNAs (gRNAs) used to knock out IDOL were designed using online gRNA design tools at atum.bio and synthego.com. Sequences of the gRNAs are shown in Table 2. The gRNAs were cloned into lentiCRISPR v2 (110). Lentiviruses to deliver the gRNAs were generated by cotransfecting the lentiCRISPR v2 constructs with pDMG.2 and psPAX2 in HEK 293T cells. MRC-5 and THP-1 cells were transduced at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 3 and 10, respectively. Transduced cells were selected with 2 μg/mL puromycin for 2 days. Validation of the knockout was done by blotting for ApoER-2, Sanger sequencing, or quantifying levels of IDOL by ELISA. The Synthego gRNA design algorithm (synthego.com) indicates potential off-target genes for the gRNAs, and we selected HDAC1 to evaluate potential off-target effects by Western blot analyses.

TABLE 2.

gRNAs used to KO IDOL and luciferase gene (from Photinus pyralis)a

| Gene | Nucleotide position | Forward sequence | Reverse sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| IDOL | 16,145,148 | CACCGGCGCCGTGATGATGCAGUAU | AAACAUACUGCAUCAUCACGGCGCC |

| IDOL | 16,143,526 | CACCGCCUUUUUGUUUUAGGUGUGC | AAACGUUUCUCAGGUUUAGCCAUAC |

| IDOL | 16,143,613 | CACCGUAUGGCUAAACCUGAGAAAC | AAACGUUUCUCAGGUUUAGCCAUAC |

| Luc | 1,355 | CACCGACAACUUUACCGACCGCGCC | AAACGGCGCGGUCGGUAAAGUUGU |

The gRNA sequence is in bold text, and the preceding sequence was used to facilitate cloning onto the lentiCRISPR v2 vector.

IDOL ELISA.

We used a sandwich ELISA (Cusabio) to quantify IDOL protein levels in THP-1 cells. Cells were washed in cold PBS and resuspended at 108 cells/mL followed by freezing at −20°C. Following 3 freeze-thaw cycles, IDOL was quantified according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Optical densities were determined using a Clariostar plate reader (BMG Labtech), and sample values were interpolated from a standard curve in GraphPad Prism v9.

Cholesterol assay.

Fibroblasts were seeded at 3 × 105 cells per well in 6-well dishes and incubated overnight. Infections were done at an MOI of 1 for 1 h, the inoculum was removed, and cells were washed twice with PBS. Infected cells were incubated in serum-free media, and 50,000 cells were harvested at appropriate time points. Samples were prepared using a cholesterol Glo bioluminescent assay (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Relative light units were measured using a Clariostar Plus plate reader (BMG Labtech), and sample values were extrapolated from a standard curve in GraphPad Prism v9.

Latency assays.

Latency assays in CD34+ HPCs were carried out as described previously (57). IDOL expression was induced prior to reactivation by treatment with 1 μM GW3965. Infections for latency in THP-1 cells were done as described previously (51).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/National Institutes of Health (NIAID/NIH) grants AI079059 and AI131598 to F.G. K.Z. was supported by a training grant (T32 AG058503) from the National Institute of Aging. We are grateful for the support of the Flow Cytometry and Human Immune Monitoring Shared Resource, supported through the Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA023074 awarded to University of Arizona.

We appreciate technical assistance from Lincoln Gay. We thank James Alwine (University of Pennsylvania), Lynn Enquist (Princeton University), Jean Wilson (University of Arizona), and John Purdy (University of Arizona) for critical discussions on this work.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Felicia Goodrum, Email: fgoodrum@arizona.edu.

Stacey Schultz-Cherry, St Jude Children's Research Hospital.

REFERENCES

- 1.Goodrum F. 2022. The complex biology of human cytomegalovirus latency and reactivation. In Kielian M, Roossinck M (ed), Advances in virus research, 1 ed, vol 112. Academic Press, New York, NY. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goodrum F, Britt W, Mocarski ES. 2022. Cytomegalovirus. In Howley PM, Knipe DM, Cohen JL, Damania BA (ed), Fields virology: DNA viruses, 7th ed, vol 2. Wolters Kluwer, Hagerstown, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hahn G, Jores R, Mocarski ES. 1998. Cytomegalovirus remains latent in a common precursor of dendritic and myeloid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:3937–3942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Min C-K, Shakya AK, Lee B-J, Streblow DN, Caposio P, Yurochko AD. 2020. The differentiation of human cytomegalovirus infected-monocytes is required for viral replication. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 10:368. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reeves MB, MacAry PA, Lehner PJ, Sissons JGP, Sinclair JH. 2005. Latency, chromatin remodeling, and reactivation of human cytomegalovirus in the dendritic cells of healthy carriers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:4140–4145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408994102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reeves MB, Sinclair JH. 2013. Circulating dendritic cells isolated from healthy seropositive donors are sites of human cytomegalovirus reactivation in vivo. J Virol 87:10660–10667. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01539-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor-Wiedeman J, Sissons JGP, Borysiewicz LK, Sinclair JH. 1991. Monocytes are a major site of persistence of human cytomegalovirus in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Gen Virol 72:2059–2064. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-9-2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forte E, Swaminathan S, Schroeder MW, Kim JY, Terhune SS, Hummel M. 2018. Tumor necrosis factor alpha induces reactivation of human cytomegalovirus independently of myeloid cell differentiation following posttranscriptional establishment of latency. mBio 9:e01560-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01560-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Söderberg-Nauclér C, Fish KN, Nelson JA. 1997. Reactivation of latent human cytomegalovirus by allogeneic stimulation of blood cells from healthy donors. Cell 91:119–126. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)80014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reeves MB, Compton T. 2011. Inhibition of inflammatory interleukin-6 activity via extracellular signal-regulated kinase-mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling antagonizes human cytomegalovirus reactivation from dendritic cells. J Virol 85:12750–12758. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05878-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buehler J, Zeltzer S, Reitsma J, Petrucelli A, Umashankar M, Rak M, Zagallo P, Schroeder J, Terhune S, Goodrum F. 2016. Opposing regulation of the EGF receptor: a molecular switch controlling cytomegalovirus latency and replication. PLoS Pathogens 12:e1005655. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weekes MP, Tan SYL, Poole E, Talbot S, Antrobus R, Smith DL, Montag C, Gygi SP, Sinclair JH, Lehner PJ. 2013. Latency-associated degradation of the MRP1 drug transporter during latent human cytomegalovirus infection. Science 340:199–202. doi: 10.1126/science.1235047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Le VTK, Trilling M, Hengel H. 2011. The cytomegaloviral protein pUL138 acts as potentiator of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor 1 surface density to enhance ULb′-encoded modulation of TNF-α signaling. J Virol 85:13260–13270. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06005-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Montag C, Wagner JA, Gruska I, Vetter B, Wiebusch L, Hagemeier C. 2011. The latency-associated UL138 gene product of human cytomegalovirus sensitizes cells to tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) signaling by upregulating TNF-α receptor 1 cell surface expression. J Virol 85:11409–11421. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05028-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Albright ER, Mickelson CK, Kalejta RF. 2021. Human cytomegalovirus UL138 protein inhibits the STING pathway and reduces interferon beta mRNA accumulation during lytic and latent infections. mBio 12:e0226721. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02267-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zarrella K, Longmire P, Zeltzer S, Collins-McMillen D, Hancock M, Buehler J, Reitsma JM, Terhune SS, Nelson JA, Goodrum F. 2023. Human cytomegalovirus UL138 interaction with USP1 activates STAT1 in infection. bioRxiv. doi: 10.1101/2023.02.07.527452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Lee SH, Albright ER, Lee J-H, Jacobs D, Kalejta RF. 2015. Cellular defense against latent colonization foiled by human cytomegalovirus UL138 protein. Sci Adv 1:e1501164. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1501164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Umashankar M, Rak M, Bughio F, Zagallo P, Caviness K, Goodrum FD. 2014. Antagonistic determinants controlling replicative and latent states of human cytomegalovirus infection. J Virol 88:5987–6002. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03506-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rak MA, Buehler J, Zeltzer S, Reitsma J, Molina B, Terhune S, Goodrum F. 2018. Human cytomegalovirus UL135 interacts with host adaptor proteins to regulate epidermal growth factor receptor and reactivation from latency. J Virol 92:e00919-18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00919-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buehler J, Carpenter E, Zeltzer S, Igarashi S, Rak M, Mikell I, Nelson JA, Goodrum F. 2019. Host signaling and EGR1 transcriptional control of human cytomegalovirus replication and latency. PLoS Pathogens 15:e1008037. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caviness K, Bughio F, Crawford LB, Streblow DN, Nelson JA, Caposio P, Goodrum F. 2016. Complex interplay of the UL136 isoforms balances cytomegalovirus replication and latency. mBio 7:e01986-15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01986-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caviness K, Cicchini L, Rak M, Umashankar M, Goodrum F. 2014. Complex expression of the UL136 gene of human cytomegalovirus results in multiple protein isoforms with unique roles in replication. J Virol 88:14412–14425. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02711-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mikell I, Crawford LB, Hancock MH, Mitchell J, Buehler J, Goodrum F, Nelson JA. 2019. HCMV miR-US22 down-regulation of EGR-1 regulates CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cell proliferation and viral reactivation. PLoS Pathog 15:e1007854. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Min IM, Pietramaggiori G, Kim FS, Passegué E, Stevenson KE, Wagers AJ. 2008. The transcription factor EGR1 controls both the proliferation and localization of hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 2:380–391. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Collins-McMillen D, Kamil J, Moorman N, Goodrum F. 2020. Control of immediate early gene expression for human cytomegalovirus reactivation. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 10:476. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krishna BA, Wass AB, O'Connor CM. 2020. Activator protein-1 transactivation of the major immediate early locus is a determinant of cytomegalovirus reactivation from latency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117:20860–20867. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2009420117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hale AE, Collins-McMillen D, Lenarcic EM, Igarashi S, Kamil JP, Goodrum F, Moorman NJ. 2020. FOXO transcription factors activate alternative major immediate early promoters to induce human cytomegalovirus reactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117:18764–18770. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2002651117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kew VG, Yuan J, Meier J, Reeves MB. 2014. Mitogen and stress activated kinases act co-operatively with CREB during the induction of human cytomegalovirus immediate-early gene expression from latency. PLoS Pathog 10:e1004195. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crawford LB, Kim JH, Collins-McMillen D, Lee BJ, Landais I, Held C, Nelson JA, Yurochko AD, Caposio P. 2018. Human cytomegalovirus encodes a novel FLT3 receptor ligand necessary for hematopoietic cell differentiation and viral reactivation. mBio 9. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00682-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hancock MH, Crawford LB, Perez W, Struthers HM, Mitchell J, Caposio P. 2021. Human cytomegalovirus UL7, miR-US5-1, and miR-UL112-3p inactivation of FOXO3a protects CD34(+) hematopoietic progenitor cells from apoptosis. mSphere 6:e00986-20. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00986-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scotti E, Hong C, Yoshinaga Y, Tu Y, Hu Y, Zelcer N, Boyadjian R, de Jong PJ, Young SG, Fong LG, Tontonoz P. 2011. Targeted disruption of the idol gene alters cellular regulation of the low-density lipoprotein receptor by sterols and liver x receptor agonists. Mol Cell Biol 31:1885–1893. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01469-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Bruin RG, Shiue L, Prins J, de Boer HC, Singh A, Fagg WS, van Gils JM, Duijs JMGJ, Katzman S, Kraaijeveld AO, Böhringer S, Leung WY, Kielbasa SM, Donahue JP, van der Zande PHJ, Sijbom R, van Alem CMA, Bot I, van Kooten C, Jukema JW, Van Esch H, Rabelink TJ, Kazan H, Biessen EAL, Ares M, Jr, van Zonneveld AJ, van der Veer EP. 2016. Quaking promotes monocyte differentiation into pro-atherogenic macrophages by controlling pre-mRNA splicing and gene expression. Nat Commun 7:10846. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Y, Tingart M, Lecouturier S, Li J, Eschweiler J. 2021. Identification of co-expression network correlated with different periods of adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs by weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA). BMC Genomics 22:254. doi: 10.1186/s12864-021-07584-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scotti E, Calamai M, Goulbourne CN, Zhang L, Hong C, Lin RR, Choi J, Pilch PF, Fong LG, Zou P, Ting AY, Pavone FS, Young SG, Tontonoz P. 2013. IDOL stimulates clathrin-independent endocytosis and multivesicular body-mediated lysosomal degradation of the low-density lipoprotein receptor. Mol Cell Biol 33:1503–1514. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01716-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hong C, Duit S, Jalonen P, Out R, Scheer L, Sorrentino V, Boyadjian R, Rodenburg KW, Foley E, Korhonen L, Lindholm D, Nimpf J, van Berkel TJC, Tontonoz P, Zelcer N. 2010. The E3 ubiquitin ligase IDOL induces the degradation of the low density lipoprotein receptor family members VLDLR and ApoER2. J Biol Chem 285:19720–19726. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.123729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zelcer N, Hong C, Boyadjian R, Tontonoz P. 2009. LXR regulates cholesterol uptake through Idol-dependent ubiquitination of the LDL receptor. Science 325:100–104. doi: 10.1126/science.1168974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]