Abstract

Background

Activation of the RON receptor tyrosine kinase, a member of the c-MET family, regulates tumorigenic phenotypes. The RON extracellular domains are critical in regulating these activities. The objective of this study was to determine the role of the first IPT domain in regulating RON-mediated tumorigenic activities and the underlying mechanisms.

Results

Two RON variants, RON160 and RONE5/6in with deletion and insertion in the first IPT domain, respectively, were molecularly cloned. RON160 was a splicing variant generated by deletion of 109 amino acids encoded by exons 5 and 6. In contrast, RONE5/6in was derived from a transcript with an insertion of 20 amino acids between exons 5 and 6. Both RON160 and RONE5/6in were proteolytically matured into two-chain receptor and expressed on the cell surface. RON160 was constitutively active with tyrosine phosphorylation. However, activation of RONE5/6in required ligand stimulation. Deletion resulted in the resistance of RON160 to proteolytic digestion by cell associated trypsin-like enzymes. RON160 also resisted anti-RON antibody-induced receptor internalization. These features contributed to sustained intracellular signaling cascades. On the other hand, RONE5/6in was highly susceptible to protease digestion, which led to formation of a truncated variant known as RONp110. RONE5/6in also underwent rapid internalization upon anti-RON antibody treatment, which led to signaling attenuation. Although ligand-induced activation of RONE5/6in partially caused epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT), it was RON160 that showed cell-transforming activities in cell focus formation and anchorage-independent growth. RON160-mediated EMT is also associated with increased motile/invasive activity.

Conclusions

Alterations in the first IPT domain in extracellular region differentially regulate RON mediated tumorigenic activities. Deletion of the first IPT results in formation of oncogenic variant RON160. Enhanced degradation and internalization with attenuated signaling cascades could be the mechanisms underlying non-tumorigenic features of RONE5/6in.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The RON (recepteur d'origine nantais) receptor tyrosine kinase belongs to the MET proto-oncogene family [1, 2], which plays a critical role in epithelial cell homeostasis and tumorigenic development [3]. Expression of RON has been found mainly in cells of epithelial origin although certain tissue macrophages and immune cells also express the RON mRNA and protein [4–6]. Accumulated evidences have indicated that aberrant RON expression, characterized by protein overexpression and generation of various variants, contributes to pathogenesis of epithelial cancers [7, 8]. Immunohistochemical staining has demonstrated that RON is overexpressed in more than 40% of primary cancer samples from breast, colon, and pancreatic tissues [4, 9–11]. Increased RON expression has also been considered as a validated prognostic factor for predicting disease progression and survival rate in certain cancer patients [10, 12]. Although RON gene mutations were not found in primary cancer samples, aberrant splicing resulting in formation of various tumorigenic RON variants is frequently observed in primary colon, breast, and brain tumors [7, 13, 14]. Functional analysis has revealed that RON activation promotes malignant phenotype of cancer cells [3]. In tumor cells overexpressing RON, cells undergo epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) featured by spindle-like morphology, diminished E-cadherin expression, and increased vimentin expression [15, 16]. EMT is a unique phenotype observed in cancer stem cells and is a critical process required for cancer metastasis [17]. Evidence has also indicated that altered RON expression results in increased survival and pro-apoptotic activity of tumor cells [18, 19]. These activities of RON help to sustain tumor growth under hostile environment such as hypoxia [3, 19, 20]. Recent studies further demonstrate that abnormality in RON expression contributes to acquired resistance of cancer cells to conventional chemotherapeutics [21]. We have recently observed that down-regulation of RON expression under chronic hypoxia is a mechanism contributing to the insensitivity of tumor cells towards small molecule inhibitor-induced inhibitory or cytotoxic activities [22]. Clearly, aberrant RON expression is a pathogenic factor contributing to cancer development and malignant progression. Such abnormality also provides the molecular basis of targeting RON for potential therapeutic intervention [23].

As described above, aberrant RON expression is featured by generation of biologically active RON variants [7, 13, 14]. Currently, seven RON variants including RON170, RON165, RON160, RON155, RONp110, RON85, and RON52 have been identified in primary cancer samples and in established cell lines [7, 14, 24]. One of the tumorigenic variants is RON160, which is constitutively active and has oncogenic activities in vivo[13]. RON160 is produced by a RON mRNA transcript through alternative splicing that eliminates 109 amino acids in the RON extracellular domain [13]. These amino acids are encoded by exons 5 and 6, which constitute the first IPT domain in the RON β-chain [25]. The β-chain extracellular sequences harbor a cluster of four IPT units between sema and transmembrane segment [25–27]. The first IPT unit contains 103 amino acids (from Pro569 to Asp671) and is featured by immunoglobulin-like fold [25]. The functions of the second and third IPT units are currently unknown. The fourth IPT unit is critically important in regulating RON protein maturation and cell surface expression [28, 29]. Currently, the mechanism of how the deletion of the first IPT domain resulting in oncogenic conversion is largely unknown. It is reasoned that the deletion causes RON conformational change and leads to spontaneous dimerization, which causes constitutive receptor phosphorylation and increased intracellular signaling activation [13].

The purpose of the present work is to determine the role of the first IPT unit in the RON extracellular sequences in regulating RON-mediated tumorigenic activities in epithelial cells. By studying two RON variants formed either by deletion of 109 amino acids coded by exons 5 and 6 or by insertion of 20 amino acids between exons 5 and 6, we observed striking differences in biochemical and biological properties. Clearly, deletion or insertion induced alterations in the first IPT domain have different biological consequences, which may have pathogenic implications in regulating RON-mediated activities.

Materials and methods

Cell Lines and Reagents

Human colon (HT-29, SW620, and SW837), breast (HCC-1937, MDA-MB231, T-47D, ZR-751, and MCF-7), and pancreatic (BxPc-3, L3.6pl, and Panc-1) cancer cell lines and NIH3T3 cells were from ATCC (Manassas, VA). Madin Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells stably expressing RON or RON160 (M-RON or M-RON160 cells) were established as previously described [15]. Human MSP was provided by Dr. E. J. Leonard (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD). Mouse monoclonal antibodies (mAb) specific to the RON extracellular sequences (clones Zt/g4 and Zt/c1) were used as preciously described [30]. Rabbit IgG antibody specific to RON C-terminal peptide was described previously [31]. Recombinant human furin was from New England BioLabs (Ipswich, MA). PD98059 (PD), SB203580 (SB) and wortmannin (WT) were from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). Mouse mAb specific to phospho-tyrosine (PY-100), phospho-Erk1/2, AKT, and other signaling proteins were from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). Rabbit or goat IgG antibodies specific to E-cadherin, vimentin, or β-actin were from BD Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY).

Reverse Transcription (RT)-Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and DNA sequencing

RT-PCR was performed as previously described [32]. Briefly, total RNA was isolated from individual cell lines using Trizol (Invitrogen, CA). RT was carried out using 2 μg of total RNA with a SuperScript Preamplification kit (Invitrogen). PCR was conducted by using a pair of oligomers to amplify RON160 or RONE5/6in cDNA fragments [32]. Amplified cDNA fragments were subcloned into the pGEM-T-easy vector (Promega) and sequenced at the Texas Tech University DNA Sequence Core facility (Lubbock, TX).

Construction of the full-length RONE5/6in cDNA and its expression in MDCK cells

The complete RONE5/6in cDNA was constructed by replacing a fragment in the wild-type RON cDNA with an amplified 0.6 Kb fragment to create the full-length RONE5/6in cDNA as previously described [32]. Transfection of MDCK cells with RONE5/6in, selection of stable cell lines, and Western blot analysis of protein expression were conducted as previously described [13].

Immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis

These methods were performed as detailed previously [31, 32]. Cellular proteins (250 μg/sample) were used for immunoprecipitation by Zt/g4 (2 μg/sample) coupled to protein G Sepharose beads. Individual proteins were detected using specific antibodies in Western blot analysis under reduced conditions. Membranes were also reprobed with rabbit IgG antibody to β-actin to ensure equal sample loading [31, 32].

Immunofluorescent cell surface analysis

Fluorescent cell surface analysis was carried out as previously described [33]. Briefly, M-RON, M-RON160 or M-RONE5/6in cells (1 × 106 cells/ml) were incubated with Zt/g4 (1 μg/sample/ml) followed by goat anti-mouse IgG coupled with FITC. Fluorescent intensity was determined by FACscan (Becton Dickinson) analysis as previously described [33]. In all assays, normal mouse IgG was used as the negative control.

Protein micro-sequencing

M-RON and M-RONE5/6in cells (3 × 106 cells/ml) in DMEM were treated with 0.05% of trypsin for various times. Cellular proteins (350 μg/sample) from lysates of M-RON or M-RONE5/6in cells were first immunoprecipitated by Zt/g4 (1 μg/sample) coupled with protein G Sepharose beads [31]. Samples were then separated in 8% SDS-PAGE under reduced conditions followed by transfer to a poly(vinylidene difluoride) membrane (Problott; Applied Biosystems) [34]. The protein bands were identified, marked and analyzed directly on an Applied Biosystems 473A protein sequencer fitted with a reaction cartridge specifically designed for poly(vinylidene difluoride) bound samples at the Colorado State University Core facility (Ford Collin, Co).

Cell migration assays

Wound healing assays were used to determine the ability of cells to migrate to cover the open space as previously described [24]. Cells were stimulated with MSP (2 nM) for 16 h. The percentage of open spaces covered by migrated cells was determined as previously described [24].

Bioassays for cell focus formation and anchorage-independent growth in soft agar

Both assays were performed as previously described [13]. For focus formation, cultured NIH-3T3 cells in 30 mm diameter dish were transiently transfected with the pcDNA3.1 expression vector containing RON, RON160, or RONE5/6in cDNA, respectively. Foci were counted after cells were maintained in DMEM with 1% FBS for 18 days. For colony formation, cells (2000 cells/dish) in 2 ml DMEM with 5% FBS and 0.3% agarose were seeded in a 30 mm diameter culture dish containing 0.7% agarose. The colony numbers were determined 18 days after initiation of cell culture.

Results

Different RON mRNA transcripts with alterations in the first IPT unit are present in colon, breast, and pancreatic cancer cells

Previous studies have shown that deletion of the first IPT unit coded by exons 5 and 6 results in formation of oncogenic variant RON160 [13]. To determine if other types of alterations exists in the first IPT unit, total RNA isolated from a panel of twelve cancer cell lines was subjected to RT-PCR analysis. The cDNA fragments were amplified by using primers that cover the first IPT unit and its surrounding sequences (+1646 to +2184 from exons 4 to 7). Results in Table 1 and Figure 1A are the summary of the RT-PCR analysis. Three cDNA fragments, Fgm-I (0.54 kb), Fgm-II (0.21 kb), and Fgm-III (0.6 kb) were obtained (data not shown). The cDNA sequence analysis indicated that Fgm-I encodes a portion of wild-type RON, which was amplified in all eleven cell lines known to express RON. MCF-7 cells do not express RON [32] and were used as a negative control. Fgm-II showed a deletion of 109 amino acids coded by exons 5 and 6 and was observed in HT-29, SW620, SW837 and Du4475 cell lines. Expression of this transcript was consistent with previous studies showing the existence of RON160 in colon and other cancer cell lines [13].

Identification and cloning of RON mRNA transcripts with alterations in the first IPT domain in cancer cell lines. A) Partial sequences of amplified RON cDNA fragments. The sequences show a deletion of 327 nucleotides coded by exons 5 and 6 and an insertion of 60 nucleotides between exons 5 and 6. The deleted sequences that encode 109 amino acids by exons 5 and 6 are italicized (as detected in RON160 cDNA). The inserted sequences encoding 20 new amino acids are underlined (as detected in RONE5/6in cDNA). The beginning and ending of the first IPT unit are indicated. The first nucleotides of exons 5, 6, and 7 are marked with an arrow. The amino acids that act as the digestive site for trypsin-like serine proteases, which led to generation of RONp110, are shown in bold. B) Schematic representation of wild-type RON, RON160, RONE5/6in, and RONp110. Mature RON contains a sema domain (localized in both α and β-chains) followed by a PSI motif and four IPT units. The deletion of exons 5 and 6 and the insertion between exons 5 and 6 in the first IPT unit are indicated with arrows. Cleavage by trypsin-like serine protease in the digestive site results in a truncated variant known as RONp110. Two tyrosine residues (Y1353 and Y1360) in the C-terminal tail are indicated. TM: transmembrane domain; TK: tyrosine kinase domain.

An interesting finding was the detection of a 0.6 kb Fgm III from HT-29, SW620, Du4475, and Panc-1 cells. Sequence analysis showed an insertion of 20-amino acids (60 nucleotides) between the last amino acid of exon 5 (Arg627) and the first amino acid of exon 6 (Pro628) (Figure 1A and Table 1). The inserted sequences were identical among fragments amplified from four cell lines. By comparing the genomic sequence of the RON gene [25], it was determined that 60 nucleotides belong to the intron sequence between exons 5 and 6, which were retained during the splicing process. The resulting product is a RON mRNA transcript, which should be expressed as a novel RON variant with insertion in the first IPT unit (designated as RONE5/6in). Thus, three specific mRNA transcripts encoding wild-type RON, RON160, and RONE5/6in were amplified from several cancer cell lines. Schematic representations of RON160 and RONE5/6in with deletion or insertion in the first IPT unit are shown in Figure 1B. Clearly, RONE5/6in is a novel variant that has not been previously reported.

Although wild-type RON and RON160 were detected by Western blot analysis using rabbit IgG specific to the RON C-terminus, we were unable to distinguish wild-type RON and RONE5/6in due to small differences in their protein size (data not shown). Moreover, since the molecular mass of RONE5/6in is almost identical to that of wild-type RON, we were unable to confirm if the RONE5/6in protein is expressed in RT-PCR positive cell lines. Nevertheless, existence of mRNA transcripts for RON160 and RONE5/6in provides us an opportunity to study the significance of the first IPT alterations in regulating RON-mediated activities.

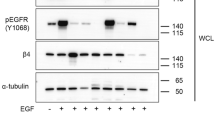

RON160 and RONE5/6in are both expressed on cell surface but showed different phosphorylation status

Since the deletion of the first IPT unit leads to oncogenic conversion [13], we wanted to know if insertion in the same domain has a similar effect. To this end, the cDNA encoding the RONE5/6in was constructed by replacing a fragment in wild-type RON cDNA with the cloned Fgm-III and then stably transfected into MDCK cells. Results from Western blot analysis showed that both RON160 and RONE5/6in were processed from single-chain precursor into mature α/β heterodimer (as evident by the presence of the β-chain) (Figure 2A). These indicate that deletion or insertion does not affect the exposure of α/β chain cleavage site (Lys304-Arg-Arg-Arg) on the surface of RON for enzymatic conversion. Interestingly, a protein with molecular mass of 110 kDa was observed in M-RONE5/6in cells, which is not observed in RON or RON160 expressing cells (this variant RONp110 will be described later in detail). This suggests that the processing of RONE5/6in differs from RON160. Immunofluorescent analysis showed that both RON160 and RONE5/6in are expressed on the cell surface (Figure 2B), suggesting that synthesized receptors were transported from cytoplasm to cell surface. Analysis of protein phosphorylation revealed that RON160 is constitutively active with high levels of tyrosine phosphorylation. MSP stimulation only marginally enhanced its phosphorylation status (Figure 2C). In contrast, RONE5/6in was not phosphorylated in unstimulated cells. MSP stimulation was required for its phosphorylation (Figure 2C). These results indicate that deletion in the first IPT unit causes spontaneous activation. However, the insertion does not transform the protein into a constitutively active variant. At intracellular signaling, RONE5/6in-mediated activation of Erk1/2 and AKT relied on MSP stimulation (Figure 2D). In contrast, Erk1/2 and AKT were constitutively phosphorylated in M-RON160 cells. MSP only slightly enhanced RON160-mediated phosphorylation of Erk1/2 and AKT. Taken together, these results demonstrate that insertion and deletion in the first IPT unit do not affect transportation, maturation, and cell surface expression of RON160 and RONE5/6n. However, the deletion resulted in constitutive activation of RON160. In contrast, the insertion failed to convert RONE5/6in into a constitutively active variant.

Expression, localization, and phosphorylation of RON160 and RONE5/6inin MDCK cells. A) Expression of RON160 and RONE5/6in in MDCK cells. Cell lysates (50 μg/sample) from M-RON, M-RON160, or M-RONE5/6in after 72 h incubation were analyzed by Western blot analysis using rabbit IgG antibody to RON C-terminus [29]. β-actin was used as the loading control. Both pro- and mature proteins were observed. The presence of RONp110 in M-RONE5/6in cells was indicated. B) Immunofluorescent analysis of RON, RON160, and RONE5/6in expression on cell surface. Cells (1 × 106 cells per sample) were incubated with 1 μg/ml of Zt/g4 specific to the RON extracellular domain [30]. Goat-anti-mouse IgG coupled with FITC was used as the secondary antibody. MDCK cells were used as the negative control. Fluorescent intensity of individual samples was analyzed by FACScan. C) Spontaneous and MSP-induced phosphorylation of RON, RON160, and RONE5/6in in MDCK cells. Cells (3 × 106 cells/sample) after 72 h incubation were stimulated at 37°C with or without 2 nM of MSP for 10 min. Cellular proteins (250 μg/sample) were immunoprecipitated with Zt/g4 (1 μg/ml) followed by Western blot analysis using anti-phosphotyrosine mAb PY-100. Membranes were also reprobed with rabbit anti-RON C-terminus antibodies as the loading control. D) Effect of MSP on RON, RON160, and RONE5/6in-mediated phosphorylation of downstream signaling proteins. Cells were stimulated for 10 min with MSP as described in C. Western blot analysis using antibodies to regular or phosphorylated Erk1/2 and AKT were carried out as previously described [29]. Data shown here are from one of three experiments with similar results.

Variant RONp110 is generated from RONE5/6in and RON but not from RON160 in response to cell-derived proteases

As shown in Figure 2A, the expression pattern of RONE5/6in differs from wild-type RON and RON160 with an additional RON variant (RONp110). Analysis by protein micro-sequencing revealed that RONp110 is a proteolytic cleaved and truncated protein missing the majority of the extracellular sequence (Figure 1A and 1B). The N-terminal first amino acid was Lys632, which is in the middle of the first IPT unit coded by exon 6. Consistent with these analyses, we detected a soluble RON isoform with molecular mass of ~80 kDa (designated as RONEr80) from culture fluids under non-reduced conditions. This protein was not observed in cells expressing RONE5/6in (data not shown). These results indicate that RONE5/6in is proteolytically processed to form RONp110 and RONEr80. Analysis of amino acids adjacent to Lys632 showed that the sequence Val-Pro-Arg-Lys632-Asp-Phe-Val is highly susceptible to digestion by trypsin-like serine proteases [35]. This indicates that insertion in the first IPT unit facilitates the exposure of this particular sequence for potential digestion by trypsin-like serine proteases. In contrast, deletion of the first IPT unit eliminates this sequence. Therefore, RON160 is resistant to trypsin-like serine proteases.

To confirm this, trypsin was used to treat M-RON160 and M-RONE5/6in cells followed by Western blot analysis. M-RON cells were used as the control. Results in Figure 3A showed that RON expression in MDCK cells did not result in RONp110 formation. RONp110 was only produced when M-RON cells were treated with trypsin in a time-dependent manner. In contrast, RONp110 existed in M-RONE5/6in cells in the absence of trypsin. The amounts of RONp110 were dramatically increased after trypsin treatment. As expected, RONp110 was not produced from RON160 when M-RON160 cells were treated with trypsin. Results in Figure 3A further confirmed that treatment of cells with soybean trypsin inhibitor (STI) blocks trypsin activity, which inhibits RONp110 generation. Thus, RONp110 generation is mediated by enzymatic cleavage at the digestive site of Val-Pro-Arg-Lys632-Asp-Phe-Val. Expression of RONE5/6in spontaneously causes RONp110 formation. Both RON and RONE5/6in have the potential to produce RONp110 after exogenous trypsin treatment.

Generation of RONp110 from RONE5/6inbut not from RON160 in response to trypsin or cell-derived trypsin-like proteases. A) M-RON, M-RON160 and M-RONE5/6in cells (2 × 106 cells per sample) were incubated for 24 h and then treated with 0.05% of trypsin in the presence or absence of STI in DMEM at 37°C for 5, 15, and 30 min. Proteins (50 μg per sample) from cell lysates were analyzed by Western blot analysis using rabbit anti-RON antibody. B) Cells were incubated for 72 h and then treated at 37°C with different amounts of FBS in DMEM for 15 min. Western blot analysis was performed as described in B. C) Effect of STI on RONp110 formation mediated by cell-associated proteases. M-RONE5/6in cells in serum-free DMEM were treated at 37°C with different amounts of STI for 48 h. Levels of RONp110 in cell lysates were determined by Western blot analysis as detailed in C. Results shown here were from one of three experiments with similar results.

To determine the source of trypsin-like proteases, M-RON160, and M-RONE5/6in cells were incubated for 72 h in serum-free or FBS-containing medium. M-RON cells were used as the control. Results from Western blot analysis showed that culture of M-RON cells with increased amounts of FBS does not result in any RONp110 formation, indicating that RONp110 is not produced by M-RON cells under regular culture conditions containing FBS (Figure 3B). Similarly, RONp110 was not generated from M-RON160 cells in the presence or absence of serum. In contrast, RONp110 was produced in M-RONE5/6in cells cultured with serum-free medium (Figure 3C). Addition of serum did not further increase RONp110 production by M-RONE5/6in cells. These results suggest that FBS is not the source for trypsin-like enzymes. It is very likely that cell-associated proteases are responsible for the generation of RONp110 in M-RONE5/6in cells.

To determine if cell-derived proteases are sensitive to inhibition by trypsin inhibitors, M-RONE5/6in cells in serum-free medium were treated with different amounts of STI. Results in Figure 3C showed that STI inhibits RONp110 formation in a dose-dependent manner, suggesting that although the nature of the enzyme is unknown, cell-associated trypsin-like protease(s) is responsible for the conversion of RONE5/6in into RONp110.

Cytoplasmic pro-RON160 and pro-RONE5/6in are differentially converted into α/β mature protein

Proteolytic conversion of pro-RON into two-chain mature RON is required for expression on the cell surface and for interaction with MSP [8, 36]. By analyzing the levels of precursor and β-chain, the conversion process can be determined. Results in Figure 4A showed the different patterns of proteolytic conversion of pro-RON160 and pro-RONE5/6in in MDCK cells. Using β-chain as an indicator, conversion of pro-RON was seen as early as 3 h, reached maximal level at about 12 h, and then stabilized thereafter. Proteolytic cleavage of pro-RON160 was processed in a manner similar to pro-RON. The mature RON160 β-chain was observed after initiation of cell labeling. Saturated levels of RON160 β-chain were seen around 12 h and maintained thereafter. In contrast, pro-RONE5/6in conversion was significantly delayed in comparison with pro-RON and pro-RON160. Although trace amounts of converted products were observed in the early stages of incubation, significant amounts of RONE5/6in β-chain were detected only after cells were incubated for 24 h. Stabilized RONE5/6in β-chain was seen mainly at 72 h of incubation (data not shown).

Differential conversions of pro-RON160 and pro-RONE5/6inexpressed in MDCK cells. A) Time-dependent conversion of pro-RON160 and pro-RONE5/6in in MDCK cells. Individual cell lines (2 × 106 cells/sample) were treated with 0.05% trypsin for 30 min to eliminate mature β-chain and then incubated with DMEM containing 10% FBS for variable hours. Cell proteins were subjected to Western blot analysis as described above Figure 3. B) Proteolytic effect of furin on pro-RON160 and pro-RONE5/6in. Purified pro-RON, RON160 and RONE5/6in in DMEM were incubated at 37°C with different amounts of furin for 5 h as previously described [37]. The samples were then subjected to Western blot analysis as described above. Protein intensity was determined by VersaDoc Imagining software as previously described [28].

Proteolytic conversion of the MET precursor is mediated by members of the subtilisin-like proprotein convertase family such as furin, which has the preferred Arg-X-Lys/Arg-Arg sequence as the cleavage site [37, 38]. We tested if delayed maturation is caused by insensitivity of pro-RONE/56in to furin-mediated cleavage. After purification by Zt/g4 immunoprecipitation, individual samples of pro-RON, pro-RON160, and pro-RONE5/6in were treated with various amounts of recombinant furin at 37°C and the conversion was evaluated by Western blot analysis. As shown in Figure 4B, pro-RON and pro-RON160 were correctly cleaved by furin in a dose-dependent manner. In contrast, pro-RONE5/6in was relatively insensitive to furin-mediated cleavage. When treated with 0.6 unit/ml of furin, only small amounts of pro-RONE5/6in were converted to the mature β-chain. Thus, pro-RONE5/6in is relatively insensitive to enzymatic cleavage by protein convertase furin.

Down-regulation of RONE5/6in but not RON160 is significantly accelerated upon anti-RON mAb engagement

The differences between RON160 and RONE5/6in prompted us to study if RONE5/6in differs from RON160 in receptor internalization process. Anti-RON mAb Zt/g4-induced RON internalization and degradation [39] was used as the model. Results in Figure 5A show a time-dependent internalization of RON160 and RONE5/6in after Zt/g4 treatment. Quantitative values are presented in Figure 5B. Zt/g4-induced RON internalization was used as the control. After Zt/g4 treatment for 12 h, more than 80% of mature RON (evident by levels of the RON β-chain) was internalized followed by degradation. Zt/g4-induced RON160 internalization was significantly delayed than that of wt-RON. Only 60% of mature RON160 was down-regulated 12 h after Zt/g4 treatment. In contrast, the down-regulation of RONE5/6in was significantly accelerated. After Zt/g4 treatment for 3 h, almost all mature RONE5/6in was internalized followed by degradation. These results suggest that RONE5/6in internalization and down-regulation is significantly accelerated upon Zt/g4 engagement. In contrast, RON160 displayed relative resistance to Zt/g4-induced internalization and degradation.

Accelerated down-regulation of RONE5/6inbut not RON160 upon anti-RON mAb treatment: A) Zt/g4-induced receptor down regulation. M-RON, M-RON160 and M-RONE5/6in cells (2 × 106 cells per sample) were treated at 37°C with 10 μg/ml of Zt/g4 for various intervals. Normal mouse IgG was used as the negative control. Cellular proteins (50 μg/ml per sample) from cell lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis using rabbit anti-RON C-terminus antibody. B) Intensity of individual protein bands from different groups in A were compared and plotted against various time points after Zt/g4 treatment. C) Preventive effect of Ccm A on Zt/g4-induced receptor down-regulation. Cells were treated for 12 h as described above. Ccm A was added after initiation of Zt/g4 treatment followed by Western blot analysis. D) Preventive effect of lactacystin on Zt/g4-inuced receptor down-regulation. Cells were treated for 12 h as described above. Lactacystin was added after initiation of Zt/g4 treatment followed by Western blot analysis. Data shown here are from one of three experiments with similar results.

Chemical inhibitors, concanamycin A (Ccm-A) and lactacystin that specifically inhibit lysosome and proteoasome-mediated protein degradation, respectively [40, 41], were used to determine how internalized proteins were degraded. Results in Figure 5C show the preventive effect of Ccm-A on lysosome-mediated degradation of RON, RON160, and RONE5/6in in MDCK cells. Although Ccm-A almost completely prevented Zt/g4-induced down-regulation of RON and RON160, it showed only a moderate effect on prevention of RONE/5/6in degradation. Similar results were also observed when proteoasome inhibitor lactacystin was used (Figure 5D). In this case, lactacystin almost completely prevented RON and RON160 degradation. However, degradation of RONE5/6in was only partially prevented by lactacystin. These results suggest that inhibition of lysosome or proteoasome-mediated degradation prevents Zt/g4-induced RON and RON160 down-regulation. However, Ccm-A or lactacystin alone only partially prevents Zt/g4-induced degradation of RONE5/6in.

Functional differences between RON160 and RONE5/6in in regulating tumorigenic activities

Overexpression of RON and RON160 in epithelial cells results in EMT-like phenotype [15, 16], which is characterized by reduced E-cadherin expression (epithelial marker) and appearance of vimentin (mesenchymal protein) (Figure 6A). Such changes were also observed in M-RONE5/6in cells; in which vimentin is expressed and levels of E-cadherin are reduced, although the levels of expression were not as obvious as RON160. Morphological analysis of cell shape also showed that RONE5/6in expression moderately causes cell morphological change (Figure 6B). In contrast, RON160 expression significantly altered cell morphologies. Scatter-like activities mediated by RON160 upon MSP stimulation were more significant in M-RON160 than in M-RONE5/6in cells.

Regulatory effect of RON160 and RONE5/6inon EMT-like activities in MDCK cells: A) Effect of RON, RON160, and RONE5/6in on epithelial/mesenchymal protein expression. Proteins (50 μg per sample) from cell lysates prepared after 72 h incubation were subjected to Western blot analysis using antibodies specific to vimentin and E-cadherin, respectively. Actin was used as the loading control. B) Effect of RON, RON160 and RONE5/6in on cell morphological changes. MDCK, M-RON, M-RON160 and M-RONE5/6in cells were cultured for 24 h and then stimulated with 2 nM of MSP for 48 h. Cell morphological changes were observed under Olympus Inverted microscope and photographed. C) Effect of RON, RON160 and RONE5/6in on spontaneous or MSP-induced MDCK cell migration. Cell monolayer was wounded as previously described [29] and stimulated with or without 2 nM of MSP for 16 h. Chemical inhibitors such as PD98059 (10 nM, specific to MAP kinase) and wortmannin (50 μg/ml, specific to PI-3 kinase) were added simultaneously. The wounded area covered by migrated cells was measured and shown as % of the covered space. Data shown here are from one of three experiments with similar results.

Results from analysis of cell migration showed that expression of RONE5/6in moderately increases spontaneous migration of MDCK cells (from 0% to 48%). The migration was further enhanced by MSP stimulation (from 53% to 78%). In contrast, RON160 expression significantly increases spontaneous migration (from 0% to 86%) (Figure 6C). MSP stimulation also slightly enhanced this activity (from 86% to 93%). Experiments using MAP kinase (PD98059) or PI-3 kinase (wortmannin) inhibitors further showed that spontaneous or MSP-induced migration is preventable by addition of PD98058 in all cell lines tested. In contrast, the effect of wortmannin was minimal. These results demonstrate that RON160 is a much stronger molecule than RONE5/6in in induction of EMT and cell migration.

We further studied the effect of RON160 and RONE5/6in on induction of focus formation and anchorage-independent growth in soft agar using NIH 3T3 cells as the model. Results in Figure 7A showed that transient expression of RONE5/6in does not cause focus formation by NIH-3T3 cells. MSP stimulation also failed to induce focus formation in RONE5/6in expressing cells. These results were in line with cells expressing wild-type RON, which is known as a non-transforming agent [42]. In contrast, RON160 expression resulted in numerous large-sized foci in transfected NIH3T3 cells. Although MSP stimulation only moderately increased the number of foci, it dramatically enlarged the size of these foci.

Effect of RON, RON160, and RONE5/6in on focus formation and anchorage independent growth: A) Focus formation by transformed NIH3T3 cells. NIH3T3 cells (1 × 105 cells per dish) were transiently transfected with 3 μg of individual pcDNA3 expression vector containing RON, RON160 or RONE5/6in cDNA as previously described [13]. After incubation for 48 h, cells in 2% FBS-DMEM were stimulated with or without 2 nM of MSP for additional 8 days. Focus formation was observed, photographed, and counted from individual groups. B) Colony formation in soft agar by transfected NIH3T3 cells. The soft agar assays were performed as previously described [13]. NIH3T3, 3T3-RON, 3T3-RON160, and 3T3-RONE5/6in cells (1000 cells per dish) were seeded in soft agar with or without 2 nM of MSP for 25 days. Cell growth at ≥30 cells per cluster was marked as a positive colony and counted.

Consistent with focus formation studies, results from the soft agar experiments showed that RONE5/6in expression does not lead to colony formation in soft agar. Addition of MSP only marginally stimulated a few small-sized colonies grown in soft agar. In contrast, RON160 expression resulted in numerous colony growths in soft agar. This effect was further enhanced after MSP is added to cell culture. Moreover, the size of individual colonies was much bigger than those in unstimulated 3T3-RON160 cells. Thus, like wild-type RON, RONE5/6in is not a transforming agent. Its expression is not sufficient to cause focus and colony formation. In contrast, RON160 is a strong transforming agent, which can be verified in both focus and colony formation assays.

Discussion

The findings in this study demonstrate that alterations in the first IPT unit in the RON extracellular sequence results in two novel variants with different biological profiles. Structurally, the IPT units consist of 80 to 100 amino acids and are featured by immunoglobulin-like fold [25, 43]. The IPT units are also found in certain transcription factors such as NF-κB and c-Jun, where it is involved in protein-protein and/or protein-DNA interaction [44]. The significance of the IPT units in MET and RON has recently been discovered and emphasized. The deletion of the first IPT unit in the RON extracellular sequences converts wild-type RON into oncogenic agent RON160 [13], although the underlying mechanisms are unknown. In MET, the fourth IPT unit in the β-chain extracellular sequence harbors a high affinity binding site for ligand HGF/SF [45]. HGF/SF binding to this IPT unit is essential for induction of MET activation [45]. Clearly, these findings illustrate the importance of the IPT units in MET/RON-mediated signaling cascades and tumorigenic activities. The data from our current studies demonstrate that deletion or insertion in the RON first IPT unit exerts different consequences. Although deletion of the first IPT unit leads to oncogenic conversion, insertion of 20 amino acids in the same unit is not sufficient to transform the RON protein into an oncogenic agent. However, insertion has important impact on biochemical properties of RON. We show that proteolytic conversion of pro-RONE5/6in into the two-chain mature protein by convertase furin is significantly delayed upon precursor synthesis. RONE5/6in is also highly susceptible to cell-associated serine proteases, which act on a short sequence leading to generation of another variant RONp110. Moreover, RONE5/6in is internalized in an accelerated manner upon anti-RON mAb engagement. Thus, alterations in the first IPT unit differentially regulate RON-mediated activity with different biochemical properties. In addition, generation of RON160 and RONE5/6in provides an opportunity to understand the roles of IPT units in regulating RON activation and activity, which could aid to develop therapeutic agents for inhibition of RON-mediated tumorigenic signaling.

Overexpression of RON in cancerous tissues is often accompanied with the generation of aberrant mRNA transcripts and their corresponding variants [13, 14]. This has been considered as a mechanism by which RON displays its protein diversity and regulates epithelial homeostasis and malignant transformation [7]. A survey by PCR of primary colon, lung, breast, and brain tumor samples has revealed that aberrant mRNA transcripts encoding for known and unknown variants such as RON165, RON160, and RON155 were wildly produced with relatively high frequencies in colon, breast, lung and other types of cancers [46]. These variants are mainly generated by aberrant mRNA splicing processes that delete exon 11 (RON165), exons 5 and 6 (RON160), and exons 5, 6 and 11 (RON155) [7, 46]. It needs to be emphasized that exon 11 encodes 49 amino acids belonging to the fourth IPT unit in the RON β-chain extracellular sequences [25], which is required for pro-RON maturation and cell surface localization [28]. Results in current studies demonstrate that alterations in the first IPT unit in the RON protein are not a rare occurrence. Among 12 cancer cell lines analyzed, abnormality in the first IPT unit was observed in 5 cell lines originating from colon, breast and pancreatic tumors. These results are consistent with those from analysis of primary tumor samples [14, 46]. As reported, deletion of exons 5 and 6 were observed in more than 50% of primary colon and 90% of brain tumor samples but not in any normal tissues [14, 46]. Further analysis of insertions between exons 5 and 6 using clinical tumor samples would be very informative. Although the underlying mechanisms of variant generation are currently unknown, it is known that aberrant splicing and intron retention in receptor tyrosine kinases occur commonly in cancer cells [47, 48]. Considering the oncogenicity is of RON160 in vivo, such alterations with high frequencies should have pathogenic significance in relevance to tumor progression and malignant phenotypes.

From the viewpoint of disrupting the first IPT unit, it was a surprise that RONE5/6in differs significantly from RON160 in terms of their biochemical and biological properties (Table 2). First, RON160 and RONE5/6in both are cleaved from precursor into respective mature forms but the kinetics of their processing is different (Figure 4). Pro-RON160 is cleaved at a rate similar to that of pro-RON. In contrast, RONE5/6in is matured at relatively late stages. This is probably due to relative insensitivity of RONE5/6in to convertase furin-mediated proteolytic cleavage. Such insensitivity could be due to sequence alterations in the insertion. Site-directed mutagenesis may verify if this is the case. Another possibility is that insertion-induced conformational change may affect the access of furin to the cleavage site located at α/β chain junction. Second, under regular culture conditions containing FBS, RONE5/6in is the major source for generation of RONp110, although wild-type RON can also be truncated by exogenous trypsin to form RONp110. This suggests that the insertion causes the digestion site (Val629-Pro-Arg-Lys-Asp-Phe) in the first IPT unit more accessible to cell-associated trypsin-like serine proteases. As a post-translational truncated product, RONp110 misses the majority of the extracellular domains including sema, PSI, and a large portion of the first IPT. MSP stimulation hardly induced its phosphorylation (Figure 1B and 2C), which suggests that MSP may not bind to RONp110. As expected, enzymatic digestion of RON or RONE56in by cell-derived trypsin-like proteases also produce a soluble ~80 kDa RON extracellular isoform (RONEr80) comprising the entire 35 kDa α-chain and a ~45 kDa partial extracellular β-chain. The isoform is similar to a previously reported RONΔ85 [24]. RONΔ85 is a soluble truncated RON variant produced by a mRNA transcript from a breast cancer cell line with insertion of 49 nucleotides between exons 5 and 6 [24]. RONΔ85 has the inhibitory effect on MSP-induced RON signaling events [24]. Considering their structural similarities, it is reasoned that the RONEr80 may have the ability to regulate MSP-induced RON-mediated activities. Currently, the role of RONp110 is unknown. Interestingly, a similar variant of MET lacking the ectodomain but retaining the transmembrane and intracellular domains has been discovered in several cancer samples [49]. This protein resides on the cell surface and displays transforming, invasive, and tumorigenic activities [49]. Third, deletion of the first IPT unit results in constitutive tyrosine phosphorylation [13]. In contrast, insertion does not convert RONE5/6in into constitutive phosphorylation. RONE5/6in remains inactive and requires MSP stimulation for phosphorylation and activation of downstream signaling molecules such as Erk1/2 and AKT (Figure 2C). Previous studies have shown that deletion of first IPT unit results in imbalance of cysteine residues in the extracellular sequences, a possible reason for spontaneous dimerization leading to constitutive phosphorylation [13]. Interestingly, a cysteine residue was seen in the inserted 20 amino acids in the RONE5/6in molecule, which also causes an imbalance in the number of cysteine residues in the extracellular sequence. However, such addition does not seem to affect the extracellular conformation of RONE5/6in. Thus, additional mechanism(s) is probably involved in constitutive activation of RON160. Fourth, RON160 is relatively resistant to anti-RON mAb-induced internalization and degradation. In contrast, RONE5/6in is highly susceptible to Zt/g4-mediated degradation (Figure 5). At present, we do not know mechanism(s) responsible for such an accelerated process. However, this is important for RON160 to sustain its intracellular oncogenic signaling. As reported previously, oncogenic RON variants created by mutations in the kinase domain are highly resistant to ligand-induced internalization [50]. We have previously found that anti-RON mAb-induced down-regulation attenuates RON-mediated tumorigenic signaling and motile-invasive activities in colon cancer cells [39]. Thus, insertion in the first IPT unit, through an unknown mechanism, accelerates antibody-induced RONE5/6in internalization and degradation. Finally, insertion and deletion in the first IPT showed differential effects on cellular activities. From functional analysis, RONE5/6in mediated EMT-like activities are similar to those mediated by wild-type RON. However, as judged by levels of vimentin and E-cadherin, changes in cell morphologies, and cell motility, RON160 is much more potent than RONE5/6in in mediating these tumorigenic activities. Analysis of cell transforming and anchorage-independent activities further demonstrate that insertion in the first IPT unit does not convert wild-type RON into a transforming agent. It is the deletion that renders RON160 as the transforming variant. As evident by in vitro transforming assays, the number of foci mediated by RON160 was significantly higher than that in RONE5/6in expressed NIH3T3 cells. Anchorage-independent growth by colonies in soft agar was also observed only in RON160 expressing NIH3T3 cells. Thus, alterations in the first IPT unit, either by insertion or deletion, result in two RON variants with distinct structural and cellular activities.

References

Ronsin C, Muscatelli F, Mattei MG, Breathnach R: A novel putative receptor protein tyrosine kinase of the met family. Oncogene. 1993, 8: 1195-1202.

Benvenuti S, Comoglio PM: The MET receptor tyrosine kinase in invasion and metastasis. J Cell Physiol. 2007, 213: 316-325. 10.1002/jcp.21183

Wagh PK, Peace BE, Waltz SE: Met-related receptor tyrosine kinase Ron in tumor growth and metastasis. Adv Cancer Res. 2008, 100: 1-33. full_text

Wang MH, Lee W, Luo YL, Weis MT, Yao HP: Altered expression of the RON receptor tyrosine kinase in various epithelial cancers and its contribution to tumorigenic phenotypes in thyroid cancer cells. J Pathol. 2007, 213: 402-411. 10.1002/path.2245

Wilson CB, Ray M, Lutz M, Sharda D, Xu J, Hankey PA: The RON receptor tyrosine kinase regulates IFN-gamma production and responses in innate immunity. J Immunol. 2008, 181: 2303-2310.

Chen YQ, Fisher JH, Wang MH: Activation of the RON receptor tyrosine kinase inhibits inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression by murine peritoneal exudate macrophages: phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase is required for RON-mediated inhibition of iNOS expression. J Immunol. 1998, 161: 4950-4959.

Lu Y, Yao HP, Wang MH: Multiple Variants of the RON Receptor Tyrosine Kinase: Biochemical Properties, Tumorigenic Activities, and Potential Drug Targets. Cancer Letter. 2007, 257: 157-164. 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.08.007.

Wang MH, Yao HP, Zhou YQ: Oncogenesis of RON receptor tyrosine kinase: a molecular target for malignant epithelial cancers. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2006, 27: 641-650. 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2006.00361.x

Thomas RM, Toney K, Fenoglio-Preiser C, Revelo-Penafiel MP, Hingorani SR, Tuveson DA, Waltz SE, Lowy AM: The RON receptor tyrosine kinase mediates oncogenic phenotypes in pancreatic cancer cells and is increasingly expressed during pancreatic cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2007, 67: 6075-6082. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4128

Welm AL, Sneddon JB, Taylor C, Nuyten DS, van de Vijver MJ, Hasegawa BH, Bishop JM: The macrophage-stimulating protein pathway promotes metastasis in a mouse model for breast cancer and predicts poor prognosis in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007, 104: 7570-7575. 10.1073/pnas.0702095104

Maggiora P, Marchio S, Stella MC, Giai M, Belfiore A, De Bortoli M, Di Renzo MF, Costantino A, Sismondi P, Comoglio PM: Overexpression of the RON gene in human breast carcinoma. Oncogene. 1998, 16: 2927-2933. 10.1038/sj.onc.1201812

Lee WY, Chen HH, Chow NH, Su WC, Lin PW, Guo HR: Prognostic significance of co-expression of RON and MET receptors in node-negative breast cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2005, 11: 2222-2228. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1761

Zhou YQ, He C, Chen YQ, Wang D, Wang MH: Altered expression of the RON receptor tyrosine kinase in primary human colorectal adenocarcinomas: generation of different splicing RON variants and their oncogenic potential. Oncogene. 2003, 22: 186-197. 10.1038/sj.onc.1206075

Eckerich C, Schulte A, Martens T, Zapf S, Westphal M, Lamszus K: RON receptor tyrosine kinase in human gliomas: expression, function, and identification of a novel soluble splice variant. J Neurochem. 2009, 109: 969-980. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06027.x

Wang D, Shen Q, Chen YQ, Wang MH: Collaborative activities of macrophage-stimulating protein and transforming growth factor-beta1 in induction of epithelial to mesenchymal transition: roles of the RON receptor tyrosine kinase. Oncogene. 2004, 23: 1668-1680. 10.1038/sj.onc.1207282

Côté M, Miller AD, Liu SL: Human RON receptor tyrosine kinase induces complete epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition but causes cellular senescence. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007, 360: 219-225. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.06.033

Acloque H, Adams MS, Fishwick K, Bronner-Fraser M, Nieto MA: Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions: the importance of changing cell state in development and disease. J Clin Invest. 2009, 119: 1438-1449. 10.1172/JCI38019

Xu XM, Wang D, Shen Q, Chen YQ, Wang MH: RNA-mediated gene silencing of the RON receptor tyrosine kinase alters oncogenic phenotypes of human colorectal carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2004, 23: 8464-8474. 10.1038/sj.onc.1207907

Wang J, Rajput A, Kan JL, Rose R, Liu XQ, Kuropatwinski K, Hauser J, Beko A, Dominquez I, Sharratt EA, Brattain L, Levea C, Sun FL, Keane DM, Gibson NW, Brattain MG: Knockdown of Ron kinase inhibits mutant phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and reduces metastasis in human colon carcinoma. J Biol Chem. 2009, 284: 10912-10922. 10.1074/jbc.M809551200

Guin S, Ma Q, Padhye S, Zhou YQ, Yao HP, Wang MH: Targeting acute hypoxic cancer cells by doxorubicin-immunoliposomes directed by monoclonal antibodies specific to RON receptor tyrosine kinase. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2010

Logan-Collins J, Thomas RM, Yu P, Jaquish D, Mose E, French R, Stuart W, McClaine R, Aronow B, Hoffman RM, Waltz SE, Lowy AM: Silencing of RON receptor signaling promotes apoptosis and gemcitabine sensitivity in pancreatic cancers. Cancer Res. 2010, 70: 1130-1140. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0761

Guin S, Wang MH: Down-Regulation of MET/RON Receptor Tyrosine Kinases in Colon Cancer Cells under Chronic Hypoxia as A Mechanism for Resistance towards Targeted Therapy. Proceedings of AACR 101th Annual Meeting: 7-21. 2010, 51: 442-April ; Washington, DC

Wang MH, Padhye SS, Guin S, Ma Q, Zhou YQ: Potential Therapeutics Specific to c-MET/RON Receptor Tyrosine Kinases for Molecular Targeting in Cancer Therapy. Acta Pharmacol Sinica. 2010, 31: 1181-1188. 10.1038/aps.2010.106.

Ma Q, Zhang K, Yao HP, Zhou YQ, Padhye S, Wang MH: Inhibition of MSP-RON signaling pathway in cancer cells by a novel soluble form of RON comprising the entire sema sequence. Int J Oncol. 2010, 36: 1551-1561.

Angeloni D, Danilkovitch-Miagkova A, Ivanov SV, Breathnach R, Johnson BE, Leonard EJ, Lerman MI: Gene structure of the human receptor tyrosine kinase RON and mutation analysis in lung cancer samples. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2000, 29: 147-156. 10.1002/1098-2264(2000)9999:9999<::AID-GCC1015>3.0.CO;2-N

Angeloni D, Danilkovitch-Miagkova A, Miagkov A, Leonard EJ, Lerman MI: The soluble sema domain of the RON receptor inhibits macrophage-stimulating protein-induced receptor activation. J Biol Chem. 2004, 279: 3726-3732. 10.1074/jbc.M309342200

Gherardi E, Love CA, Esnouf RM, Jones EY: The sema domain. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004, 14: 669-678. 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.10.010

Collesi C, Santoro MM, Gaudino G, Comoglio PM: A splicing variant of the RON transcript induces constitutive tyrosine kinase activity and an invasive phenotype. Mol Cell Biol. 1996, 16: 5518-5526.

Zhang K, Zhou YQ, Yao HP, Wang MH: Alterations in a defined extracellular region of the RON receptor tyrosine kinase promote RON-mediated motile and invasive phenotypes in epithelial cells. Int J Oncol. 2010, 36: 255-264.

Yao HP, Luo YL, Feng L, Cheng LF, Lu Y, Li W, Wang MH: Agonistic monoclonal antibodies potentiate tumorigenic and invasive activities of splicing variant of the RON receptor tyrosine kinase. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006, 5: 1179-1186.

Zhang K, Yao HP, Wang MH: Activation of RON Differentially Regulates Claudin Expression and Localization: Role of Claudin-1 in RON-Mediated Epithelial Cell Motility. Carcinogenesis. 2008, 29: 552-559. 10.1093/carcin/bgn003

Chen YQ, Zhou YQ, Angeloni D, Kurtz AL, Qiang XZ, Wang MH: Overexpression and activation of the RON receptor tyrosine kinase in a panel of human colorectal carcinoma cell lines. Exp Cell Res. 2000, 261: 229-238. 10.1006/excr.2000.5012

Guin S, Yao HP, Wang MH: RON receptor tyrosine kinase as a target for delivery of chemodrugs by antibody directed pathway for cancer cell cytotoxicity. Mol Pharm. 2010, 7: 386-797. 10.1021/mp900168v

Morris GE, Jackson PJ: Identification by protein microsequencing of a proteinase-V8-cleavage site in a folding intermediate of chick muscle creatine kinase. Biochem J. 1991, 280: 809-811.

Evnin LB, Vasquez JR, Craik CS: Substrate Specificity of Trypsin Investigated by Using a Gentic Selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990, 87: 6659-6663. 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6659

Wang MH, Julian FM, Breathnach R, Godowski PJ, Takehara T, Yoshikawa W, Hagiya M, Leonard EJ: Macrophage stimulating protein (MSP) binds to its receptor via the MSP beta chain. J Biol Chem. 1997, 272: 16999-17004. 10.1074/jbc.272.27.16999

Mark MR, Lokker NA, Zioncheck TF, Luis EA, Godowski PJ: Expression and characterization of hepatocyte growth factor receptor-IgG fusion proteins. Effects of mutations in the potential proteolytic cleavage site on processing and ligand binding. J Biol Chem. 1992, 267: 26166-26171.

Komada M, Hatsuzawa K, Shibamoto S, Ito F, Nakayama K, Kitamura N: Proteolytic processing of the hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor receptor by furin. FEBS Lett. 1993, 328: 25-29. 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80958-W

Li ZZ, Yao HP, Guin S, Padhye SS, Zhou YQ, Wang MH: Monoclonal antibodies-induced down-regualtion of RON receptor tyrosine kinase diminishes tumorigenic activities of colon cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2010, 37: 473-482.

Petrelli A, Circosta P, Granziero L, Mazzone M, Pisacane A, Fenoglio S, Comoglio PM, Giordano S: Ab-induced ectodomain shedding mediates hepatocyte growth factor receptor down-regulation and hampers biological activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006, 103: 5090-5095. 10.1073/pnas.0508156103

Monticone M, Biollo E, Fabiano A, Fabbi M, Daga A, Romeo F, Maffei M, Melotti A, Giaretti W, Corte G, Castagnola P: z-Leucinyl-leucinyl-norleucinal induces apoptosis of human glioblastoma tumor-initiating cells by proteasome inhibition and mitotic arrest response. Mol Cancer Res. 2009, 7: 1822-1834. 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0225

Santoro MM, Collesi C, Grisendi S, Gaudino G, Comoglio PM: Constitutive activation of the RON gene promotes invasive growth but not transformation. Mol Cell Biol. 1996, 16: 7072-7083.

Bork P, Doerks T, Springer TA, Snel B: Domains in plexins: links to integrins and transcription factors. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999, 24: 261-263. 10.1016/S0968-0004(99)01416-4

Siponen MI, Wisniewska M, Lehtio L, Johansson I, Svensson L, Raszewski G, Nilsson L, Sigvardsson M, Berglund H: Structural determination of functional domains in Early B-cell Factor (EBF) family of transcription factors reveals similarities to rel DNA binding proteins and a novel dimerisation motif. J Biol Chem. 2010, 285: 25875-25879. 10.1074/jbc.C110.150482

Basilico C, Arnesano A, Galluzzo M, Comoglio PM, Michieli P: A high affinity hepatocyte growth factor-binding site in the immunoglobulin-like region of Met. J Biol Chem. 2008, 283: 21267-21277. 10.1074/jbc.M800727200

Wortinger M, Liu L: RON splice variant prevalence in human tumors. Proceedings of AACR 99th Annual Meeting: 12-16. 2008, 49: 3610-April ; San Diego, CA

Robinson CJ, Stringer SE: The splice variants of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and their receptors. J Cell Sci. 2001, 114: 853-865.

Tacconelli A, Farina AR, Cappabianca L, Gulino A, Mackay AR: Alternative TrkAIII splicing: a potential regulated tumor-promoting switch and therapeutic target in neuroblastoma. Future Oncol. 2005, 1: 689-698. 10.2217/14796694.1.5.689

Merlin S, Pietronave S, Locarno D, Valente G, Follenzi A, Prat M: Deletion of the ectodomain unleashes the transforming, invasive, and tumorigenic potential of the MET oncogene. Cancer Sci. 2009, 100: 633-638. 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.01079.x

Penengo L, Rubin C, Yarden Y, Gaudino G: c-Cbl is a critical modulator of the Ron tyrosine kinase receptor. Oncogene. 2003, 22: 3669-3679. 10.1038/sj.onc.1206585

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by R01 grant (CA91980) from US National Institutes of Health and Amarillo Area Foundation (to MHW). We thank Dr. E. J. Leonard (National Cancer Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) for providing mature human MSP. The assistance from Ms. Snehal S. Padhye (Texas Tech University HSC School of Pharmacy, Amarillo, TX) in editing the manuscript is greatly appreciated.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

QM carried out most biochemical and biological studies. KZ did RT-PCR and cDNA cloning studies. SG performed internalization/degradation experiments. YQZ and MHW participated in the design of the study and draft the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, Q., Zhang, K., Guin, S. et al. Deletion or insertion in the first immunoglobulin-plexin-transcription (IPT) domain differentially regulates expression and tumorigenic activities of RON receptor Tyrosine Kinase. Mol Cancer 9, 307 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-4598-9-307

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-4598-9-307