Abstract

In this research we examined relationships between Big Five personality traits, emotion regulation strategies and subjective well-being. In two studies we explored the mediational role of habitual use of two regulation strategies: reappraisal and suppression in the relationship between personality traits and two aspects of well-being (i.e., life satisfaction and experience of positive affect and negative affect). In Study 1 (n = 233) we found that the most robust predictors of higher life satisfaction were higher extraversion, conscientiousness, emotional stability (lower neuroticism) and reappraisal, as well as lower suppression of emotions. We obtained similar pattern of results in Study 2 (n = 265) which showed that higher positive affect was significantly predicted by higher extraversion, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and reappraisal. Negative affect was negatively predicted only by emotional stability. Additional analyses indicated that suppression mediated the link between extraversion and life satisfaction, whereas reappraisal mediated associations of emotional stability with life satisfaction and positive affect. The studies reveal the role of emotion regulation for extraversion and emotional stability and their association with well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Personality and Subjective Well-Being

Subjective well-being (SWB) is defined as a group of multi-dimensional (cognitive, affective), appraisals of one’s own life and functioning (Diener et al. 1999). From numerous studies devoted to the determinants of well-being, researchers have concluded that external events and objective variables, such as broad situational and demographic factors, explain surprisingly little in the variability of subjective well-being (Diener et al. 1999). The top-down approaches explaining variability in SWB seem more promising. The most important construct studied in this context is personality. It is argued that personality influences the way in which people experience what happens in their lives and determines typical levels of SWB (Magnus et al. 1993, p. 1047). Personality seems to be one of the major predictors of SWB (Diener and Lucas 1999); however, the mechanisms underlying this association are still poorly understood. In the present studies we examine whether specific emotion regulation strategies may explain the link between various personality traits and SWB.

Among personality traits, two seem especially important for SWB: extraversion and neuroticism (sometimes labeled by its lower extreme ‘emotional stability’). Generally, neuroticism correlates negatively, while extraversion positively with both cognitive (e.g., life satisfaction) and affective components (experienced mood and affect) of SWB (Diener and Lucas 1999). Of particular interest has been the association between personality and affective responses. The relevant research (Matthews et al. 2009; Thayer 1989; Watson 2000) has indicated that high neuroticism is connected to negative affect and tense arousal, while high extraversion is associated with positive affect, hedonic tone, and energetic arousal. Furthermore, it has been suggested that neuroticism is generally a substantial predictor of negative mood, independently of situational context. At the same time, the link of extraversion with affect is more dependent on external factors (Goryńska et al. 2015; Matthews et al. 2009; Zajenkowska et al. 2015; Zajenkowski et al. 2012).

Other major personality traits were rarely studied in the context of SWB. Among other Big Five traits, conscientiousness (Goryńska et al. 2015; Soto 2015; Weiss et al. 2008) and agreeableness (DeNeve and Cooper 1998; Steel et al. 2008) were found to predict higher positive affect and happiness. By contrast, openness showed no consistent associations with SWB (Watson 2000). However, in a recent study, Zajenkowski and Matthews (2019) have shown that the openness subfactors might be differentially associated with affect. Specifically, intellect reflecting intellectual engagement and perceived intelligence, was associated with high positive emotionality, whereas openness (sensational experiences and creativity) did not correlate with affect.

Several theories explaining the mechanisms underlying the personality-SWB link have been proposed (Diener and Lucas 1999). Some researchers emphasized that basic personality predispositions may determine one’s typical level of well-being through biological mechanisms (e.g. Headey and Wearing 1989). In line with this logic, different life can change a person’s well-being but sooner or later it will return to the typical level determine by personality. This notion is supported by the studies showing that after powerful events, people have a tendency to regain affective balance thanks to stable personality predispositions (Headey and Wearing 1989), as well as by genetic studies indicating that genes strongly influence happiness (Diener et al. 1999; Lykken and Tellegen 1996; Lyubomirsky et al. 2005). Additionally, there is some evidence from twin samples that personality and SWB may have common genetic basis (Weiss et al. 2008).

According to other theory explaining the link between personality and SWB, personality traits may have an indirect impact on individual’s happiness, for example particular personality dispositions may be related to behaviors promoting happiness (Soto 2015). Correspondingly, extraverts are more sociable, spend more time with friends, which may lead better interpersonal relationships and result in SWB icrease (Diener 1984). By contrast, people high in neuroticism focus more on threatening stimuli, which may prone them to experience more negative affect and low life satisfaction (Matthews et al. 2009).

Some prior studies have indicated that personality traits are linked with a tendency toward specific emotion regulation strategies (cf. John and Gross 2004). Furthermore, these strategies have been found to correlate with SWB (Gross 1998). Thus, in the present studies we examine whether personality traits may indirectly influence the level of SWB via a tendency toward using a specific emotion regulation strategy (i.e., expressive suppression and cognitive reappraisal).

Emotion Regulation and Subjective Well-Being

Emotion regulation is typically defined as a process by which people influence their emotions: what and when they feel, and how emotions are experienced and expressed (Campos et al. 2004; Garnefski et al. 2001; Gross 2014, 2015a, b; Koole 2009). Emotional regulation influences the dynamics, speed and duration of emotion occurrence. Furthermore, it has impact on behavior, experience and physiology. Emotional regulation reduces, strengthens or maintains either positive or negative emotions, due to the person’s current goals (Gross 1998, 2002, 2014; Tamir 2009). Successful emotion regulation depends on achieving the goals that are adopted in a particular emotion regulation episode. Previous studies showed that successfull emotion regulation has many adaptive outcomes, including better psychological health and higher level of well-being (Aldao et al. 2010; Catalino and Fredrickson 2011; Gross 2015a, b; Gross and John 2003; Koole et al. 2015; Luhmann et al. 2012; Nyklicek et al. 2011; Salovey et al. 2010; Schwager and Rothermund 2014; Troy et al. 2010, 2013). Due to successful emotional regulation, people can make better use of their emotions. This in turn facilitates better coping and goal achievement (Frijda 2007). At the same time, emotion regulation impairment is observed in many different psychological disorders (DeSteno et al. 2013; Etkin and Wager 2007; Jazaieri et al. 2013; Kring and Sloan 2009; Werner and Gross 2010).

Some previous studies documented how chosen emotion regulation strategies can directly correlate to different aspects of well-being. Researchers have focused mainly on two strategies of emotion regulation: cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression. Reappraisal, defined as “construing a potentially emotion-eliciting situation in a way that changes its emotional impact” (Gross and John 2003, p. 349) or modifying the interpretation of the situation, occurs before an emotional reaction is generated (e.g., Gross 2002; Gross and John 2003; Ochsner and Gross 2008, 2014). Thus, it can be more effective in regulating the whole emotional experience and response. Suppression, aimed at inhibiting the expression of experienced emotion (Gross 1998), affects only behavioral outcomes of the emotional response.

In research undertaken by Gross and John (2003), habitual use of reappraisal correlated negatively with depression, and positively with optimism, life satisfaction and well-being (e.g., in the domains of “environmental mastery, personal growth, self-acceptance, positive relations with others and purpose in life” Ryff and Keyes 1995, p. 719; see also Cutuli 2014). This can partly result from the fact that in general, that participants experienced and expressed more positive and less negative affect (Gross and Levenson 1993; John and Gross 2004). By contrast, suppression negatively correlated with well-being, optimism, satisfaction with life and with interpersonal relations (Srivastava et al. 2009). Furthermore, habitual use of suppression was negatively related to experiencing positive affect and positively related to negative negative (John and Gross 2004). Additionally, experimental evidence shows that reappraisal has a more adaptive profile of affective, cognitive and social consequence than suppression (Dan-Glauser and Gross 2011; John and Gross 2004; Mauss and Gross 2004). Using instructed reappraisal in experimental studies, as well as in everyday negative situations, leads to reducing negative emotions and increasing positive ones, while using suppression either increases or does not affect subjectively experienced negative emotions and decreases positive emotions (John and Gross 2004).

Furthermore, Aldao and Nolen-Hoeksema (2012a, b) demonstrated that particular regulatory strategies, for example suppression and rumination were strongly related to psychopathology, while other strategies, mainly reappraisal and acceptance, seemed to be more related to psychological health. As argued by Bloch et al. (2010) „studies documented the greater us of suppression among clinical populations compared with healthy controls (p. 97). This result is especially strong for patients suffering from anxiety, eating disorders and PTSD. The longitudinal study by Larsen et al. (2012) suggests a causal relation between suppression and psychopathology symptoms, showing that using suppression preceded appearance of depressive symptoms.

Thus, the results of previous research clearly suggest that reappraisal is positively related to well-being and psychological health, while suppression is negatively related to well-being and positively related to psychopathology (Moore et al. 2008).

Personality and Emotion Regulation

To date, only a few investigations have explored the relationship between personality and emotion regulation in non-clinical populations (John and Gross 2004; Purnamaningsih 2017; Wang et al. 2009). However, quite a number of studies looked into the link between emotion regulation and personality disorders. As the results indicate, various personality disorders are related to different forms of emotion dysregulation, including using maladaptive strategies, such as rumination, avoidance or suppression (Aldao et al. 2010; Gartz and Roemer 2004; Gross et al. 2019). For example, individuals with borderline personality disorder manifest high impulsivity and affective lability, which are associated with poor emotion regulation (Rosenthal et al. 2008).

As for Big Five personality traits and emotion regulation, findings seem consistent across studies. Specifically, neuroticism was shown to be negatively correlated with reappraisal (Gross and John 2003; Purnamaningsih 2017; Wang et al. 2009). John and Gross (2004) have suggested that emotionally stable individuals (those who were low in neuroticism) experience less negative affect and as a result do not have to deal with consequences of strong negative affect. This may make it easier for them to use adaptive and effective regulation strategies early in the process of emotion generation than it is for individuals with high neuroticism. Further, the authors emphasize that “to the extent that neuroticism is associated with either tonic levels or phasic responses of negative emotion (Gross et al. 1998), and that reappraisal involves the down-regulation of the brain regions (such as the amygdala) that are involved in negative-emotion generation (Ochsner et al. 2002), individuals low in neuroticism may find it easier to use reappraisal to regulate negative emotion” (John and Gross 2004, p. 1322).

Extraversion has been found to correlate mainly with low suppression (John and Gross 2004; Purnamaningsih 2017; Wang et al. 2009). This result seems to be consistent with the definition of extraversion, which implies that extraverts do not hide emotions and easily express their feelings (Eysenck 1967). John and Gross (2004) interpret this finding in the context of sociability associated with extraversion. Specifically, introverts avoid interpersonal contact and it may result in hiding and suppressing their feelings. Extraverts, on the other hand, feel comfortable among other people and therefore are more often they express emotions in social situations.

Although Gross and John (2003) reported only a weak positive correlation between agreeableness and reappraisal, a recent study by Purnamaningsih (2017) revealed stronger association between these variables. This result is consistent with many studies demonstrating that agreeable individuals use reappraisal to modify the impact of antisocial stimuli (Meier and Robinson 2004). It was proved that agreeable individuals, in comparison to people lower in agreeableness, put more effort into controlling negative emotions, especially those related to anger and aggression as produced by negatively-valenced stimuli (Finley et al. 2016; Tobin et al. 2000). This increased effort seems to result from engaging reappraisal. Meier et al. (2006) showed that people with high level of agreeableness activate prosocial ways of thinking in reaction to aggression-related primes. They categorize prosocial words faster (compared to less agreable individuals) when the words are primed with hostile stimuli.

Finally, the remaining two traits from the Big Five were found to correlate with emotion regulation strategies. Specifically, both conscientiousness and openness correlated positively to reappraisal and negatively - to suppression (Gross and John 2003; Purnamaningsih 2017). However, these associations were relatively small and no attempts have been made to theoretically explain their underlying mechanisms.

Current Research

In the current studies we planned to investigate the relationships between personality traits, emotion regulation strategies and SWB. Specifically, we were interested in Big Five personality traits and habitual use of two chosen regulatory strategies: reappraisal and suppression. Moreover, we investigated cognitive and affective aspects of well-being such as: life satisfaction (Study 1) and experience of positive affect and negative affect (Study 2).

The present research had two aims. First, we wanted to confirm the relationships between Big Five traits, SWB and (chosen) emotion regulation strategies found in prior studies. Specifically, we expected that extraversion, agreeableness and conscientiousness would be positively correlated with SWB, whereas neuroticism would be negatively related to SWB as suggested by previous studies (Diener and Lucas 1999; Matthews et al. 2009). Additionally, we expected that reappraisal and suppression would correlate positively and negatively with SWB, respectively (e.g., John and Gross 2004). Finally, we predicted that reappraisal should be negatively linked to neuroticism and positively linked to agreeableness, whereas suppression would be negatively correlated with extraversion (Gross and John 2003; Purnamaningsih 2017).

The second aim of our research was to test the mediational role of emotion regulation in the relationship between personality and SWB. As mentioned above, personality traits might influence SWB directly or indirectly (Diener and Lucas 1999). In the case of the latter possibility, it has been suggested that some personality traits may be associated with behavioral tendencies, preferences and strategies that increase or decrease SWB. It is likely that the habitual use of a given strategy is one of such tendencies and indirectly promotes (or reduces) SWB. In particular, one may expect that frequent use of reappraisal, a characteristic that is mainly for agreeable and stable (low on neuroticism) individuals, leads to higher levels of SWB, whereas the use of suppression, characteristic of introverts (low extraversion) decreases SWB.

Study 1

Study 1 aimed to verify associations between Big Five traits, emotion regulation strategies and life satisfaction, as well as to test whether emotion regulation mediates relationships between personality and life satisfaction.

Method

Participants

Study 1 was conducted among 233 Polish undergraduate students from several universities in Warsaw, Poland. The whole sample consisted of 123 women and 110 men. The age of the participants ranged from 18 to 39 years (Mage = 23.62 SD = 3.79). All participants were Polish native speakers. Participation was voluntary and anonymous. Participants were recruited via generally accessible websites. They were volunteers. Participants were tested individually in laboratory settings at University of Warsaw. Participants completed several measures, some of which were not relevant for the present study, and received approximately 10 EUR for participation.

Measures

The habitual use of the two emotion regulation strategies, cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression, was measured with the Polish version of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (Gross and John 2003), already used in previous studies (e.g., Kobylińska et al. 2018; Śmieja et al. 2011). It consists of 10 questions. Six questions measure the tendency to use cognitive reappraisal (e.g., “When I want to feel more positive emotions, I change the way I think about a situation I’m in”). The remaining four questions measure the tendency to use suppression (e.g., “I control my emotions by not expressing them”). Participants answer the questions on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 = I totally disagree to 7 = I totally agree. According to the results of the previous research, the Polish version of ERQ is highly reliabile (αs ranging from .74 to .85 for suppression subscale and from .75 to .85 for reappraisal subscale; Śmieja et al. 2011).

Big Five traits were measured with the 50-item set of International Personality Items Pool Big Five Factor Markers questionnaire (Goldberg 1992) in the Polish adaptation by Strus et al. (2014). The questionnaire measures: emotional stability (e.g., “I often feel depressed”; reverse coded, “I do not like myself”; reverse coded), extraversion (e.g., “I feel great among people”, “I easily make friends”), agreeableness (e.g., “I believe that other people have good intentions”, “I accept people as they are”), conscientiousness (e.g., “I only do what is necessary”, “I do not finish what I’ve started”; reverse coded) and intellect (e.g., “I avoid philosophical discussions”; reverse coded, “I do not like arts”; reverse coded) It has a 5-point Likert-type response format ranging from 1 = very inaccurate to 5 = very accurate. The Polish version has high internal consistency (αs ranging from .73 to .91), and adequate validity (factor structure and correlations with other Big Five measures; Strus et al. 2014).

Life satisfaction was measured with the Polish version of Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al. 1985; adapted by Jankowski 2015). The scale consists of five items, for example, “I am satisfied with my life” or “The conditions of my life are excellent”. The participants answer using a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = I totally disagree to 7 = I fully agree. Previous research (Jankowski 2015) showed that reliability of the Polish SWLS was high as indicated by Cronbach’s α .86 and test–retest coefficient .85–.93 (three-week intervals).

Procedure

The study was conducted in laboratory at University of Warsaw, Poland. After informed consent, participants completed several questionnaires and cognitive tasks, some of which are not relevant for the present research. At the end participants were informed that they could leave their e-mail address if they would like to receive information about group results of the study.

Results and Discussion

Zero-Order Correlations

These are presented in Table 1. Life satisfaction positively correlated with extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability and reappraisal but negatively correlated with suppression. Reappraisal significantly positively correlated with agreeableness and emotional stability. Suppression was significantly negatively correlated with extraversion, agreeableness and intellect. Life satisfaction significantly positively correlated with extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness and emotional stability. The relationship between life satisfaction and intellect was not significant.

Regression Analysis

We performed multiple regression analysis to investigate the effects of personality traits and emotion regulation strategies (i.e., reappraisal and suppression) on life satisfaction (Table 2).

In the first step we introduced personality traits and found significant positive effects of: extraversion, conscientiousness and emotional stability on life satisfaction.

In the second step we introduced emotion regulation strategies and found a significant positive effect of reappraisal and a significant negative effect of suppression. After introducing emotion regulation strategies, extraversion was no longer a significant predictor of life satisfaction. We found a weaker, albeit still significant, positive effect of emotional stability and significant positive effect of conscientiousness.

To perform a full test of our hypotheses, we checked for the indirect effects of extraversion, conscientiousness and emotional stability on life satisfaction via emotion regulation strategies (reappraisal and suppression). Moreover, in reported models, aside from investigating the effect of the independent variables (the IVs) on life satisfaction, we controlled for the effects of all personality traits. All mediation models reported for Study 1 were estimated with Model 4 of the PROCESS macro (Hayes 2015) using a bootstrap procedure with 5000 resamples.

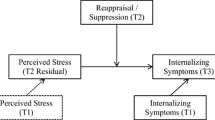

In the first model extraversion served as the focal predictor, reappraisal and suppression were treated as parallel mediators and life satisfaction constituted the dependent variable (DV). As shown in Fig. 1, it was suppression (95%CIbc = .003 to .02) but not reappraisal (95%CIbc = −.003 to .006) that fully mediated the positive effect of extraversion on life satisfaction. Specifically, extraversion was negatively related to suppression, which, in turn, was a negative predictor of life satisfaction.

Results of the mediation analysis from Study 1: effect of extraversion on life satisfaction. On the path from extraversion to life satisfaction the direct effect is shown on the arrow above, and the total effect (the effect without controlling for the mediator variables) is shown on the arrow below. The entries are unstandardised effects. Solid arrows reflect significant effects (*** p < .001. ** p < .01. * p < .05)

In the second model emotional stability served as the focal predictor, reappraisal and suppression were treated as parallel mediators and life satisfaction constituted the DV. As shown in Fig. 2, it was reappraisal (95%CIbc = 0.001 to 0.01) but not suppression (95%CIbc = −0.01 to 0.001) that partially mediated the positive effect of emotional stability on life satisfaction. Specifically, emotional stability was positively related to reappraisal, which, in turn, was a positive predictor of life satisfaction.

Results of the mediation analysis from Study 1: effect of emotional stability on life satisfaction. On the path from emotional stability to life satisfaction the direct effect is shown on the arrow above, and the total effect (the effect without controlling for the mediator variables) is shown on the arrow below. The entries are unstandardised effects. Solid arrows reflect significant effects (*** p < .001. ** p < .01. * p < .05)

In the third model, conscientiousness served as the focal predictor, reappraisal and suppression were treated as parallel mediators and life satisfaction constituted the DV. The indirect effects of conscientiousness on life satisfaction were insignificant using both reappraisal (95%CIbc = −0.01 to 0.001) and suppression (95%CIbc = −0.01 to 0.002) as mediators (Fig. 3).

Results of the mediation analysis from Study 1: effect of conscientiousness on life satisfaction. On the path from conscientiousness to life satisfaction the direct effect is shown on the arrow above, and the total effect (the effect without controlling for the mediator variables) is shown on the arrow below. The entries are unstandardised effects. Solid arrows reflect significant effects (*** p < .001. ** p < .01.)

Study 2

Study 2 aimed to verify associations between Big Five traits, emotion regulation strategies and positive/negative affect, as well as to test whether emotion regulation mediates relationships between personality and positive/negative affect.

Method

Participants

Two hundred sixty-five students of the University of Warsaw, Poland and attendees of an open lecture organized at the university (192 women, 69 men, four people did not specify their gender) participated in Study 2. The lecture topic was not related to the current study. All participants were native Polish speakers. Their age varied from 19 to 61 (Mage = 22.04, SD = 3.53; eight people did not report their age).

Measures

Habitual use of emotion regulation strategies and Big Five were assessed with the same measures as in Study 1.

Trait positive and negative emotions were assessed with the Polish version of Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS, trait version; Watson et al. 1988; adapted by Brzozowski 2010). This version consisted of 10 positive and 10 negative adjectives that measured positive and negative affect. “Participants rated how much they experienced each particular state using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = not at all or very slightly to 5 = extremely” (Zajenkowski and Matthews 2019, p. 4; see also: Brzozowski 2010).

Reliability indices for measures used in this study, along with basic descriptive statistics, are shown in Table 3.

Procedure

The study always took place at the end of a lecture. At the beginning, the researchers’ assistant introduced herself and presented some information about the study. Participants were informed that the study refers to links between personality and methods of dealing with emotions, and that it is absolutely voluntary and anonymous. Next, participants filled in the questionnaires in rotated order. Each questionnaire had its own instruction. At the end, participants were informed that they could leave their e-mail address if they would like to receive information about group results of the study. There was no compensation for participating in the study.

Results and Discussion

Zero-order correlations are presented in Table 3. Trait positive affect was significantly positively correlated with reappraisal and significantly negatively correlated with suppression. Moreover, trait positive affect was significantly positively related to all personality traits (i.e., extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, intellect).

On the other hand, trait negative affect was negatively correlated with reappraisal, but its correlation with suppression was not significant. Additionally, this dimension was related negatively to extraversion, agreeableness and emotional stability, but not to conscientiousness and intellect.

As in Study 1, reappraisal was significantly positively correlated with agreeableness and emotional stability. We did not obtain significant correlation coefficients between reappraisal and: extraversion, conscientiousness or intellect. Also, in line with the results of Study 1, suppression was significantly negatively correlated with extraversion and agreeableness. Interestingly, our results also showed a small but significant positive relationship between suppression and emotional stability. However, this correlation disappeared when controlling for the relationship between reappraisal and emotional stability (partial Pearson correlation coefficient: r(263) = .08, p = .18). We did not find significant correlations between suppression and conscientiousness or intellect.

Regression Analysis

We performed multiple regression analyses to investigate the effects of personality traits and emotion regulation strategies (i.e., reappraisal and suppression) on trait positive affect (Table 4) and negative affect (Table 5).

Trait Positive Affect

In the first step we introduced personality traits as predictors of trait positive affect and found significant positive effects of extraversion, conscientiousness, emotional stability and intellect. In the second step we introduced two additional predictors – emotion regulation strategies – and found a significant positive effect of reappraisal, but not suppression. We also observed that the effect of emotional stability on trait positive affect decreased after introducing additional predictors into the model (Table 4).

Trait Negative Affect

Following similar pattern of analysis as the one described above, after including personality traits into the model in the first step, we found significant negative effect of emotional stability on trait negative. Other personality variables did not significantly predict trait negative. Both variables introduced in the second step—reappraisal and suppression—were also not related to negative affect (Table 5).

Following a procedure similar to that of Study 1, in the next step we checked if the use of reappraisal and suppression emotion regulation strategies mediated the direct relations between personality traits (extraversion, emotional stability, conscientiousness) and trait positive affect. We did not perform similar analyses for negative affect, as the effects of both potential mediators – reappraisal and suppression – on this variable, were not significant (see Table 5). As with Study 1, all mediation models reported for Study 2 were estimated with Model 4 of the PROCESS macro (Hayes 2015) using a bootstrap procedure with 5000 resamples. Moreover, in reported models, aside from investigating the effect of the IV on trait positive affect, we controlled for the effects of all personality traits.

In the first mediation model, extraversion was put in the role of the IV. We did not obtain a significant indirect effect of extraversion on positive affect with reappraisal (95%CIbc = −.004 to .000) and suppression (95%CIbc = −.003 to .005) in the mediator role (Fig. 4). Although reappraisal significantly predicted trait positive affect, it was not significantly related to extraversion.

Results of the mediation analysis from Study 2: effect of extraversion on trait PA. On the path from extraversion to trait PA the direct effect is shown on the arrow above, and the total effect (the effect without controlling for the mediator variables) is shown on the arrow below. The entries are unstandardised effects. Solid arrows reflect significant effects (*** p < .001. ** p < .01.)

In the second model, emotional stability was a direct predictor, while reappraisal and suppression was treated as mediators and positive affect constituted the DV. As shown in Fig. 5, reappraisal (95%CIbc = .002 to .011) but not suppression (95%CIbc = −.003 to .001) partially mediated the positive effect of emotional stability on trait positive affect. Emotional stability was positively related to reappraisal, which was a positive predictor of trait positive affect.

Results of the mediation analysis from Study 2: effect of emotional stability on trait PA. On the path from emotional stability to trait PA the direct effect is shown on the arrow above, and the total effect (the effect without controlling for the mediator variables) is shown on the arrow below. The entries are unstandardised effects. Solid arrows reflect significant effects (*** p < .001. ** p < .01. * p < .05)

In the third model, conscientiousness served as the IV, with two emotion regulation strategies as parallel mediators and positive affect as the DV. Analysis showed that both reappraisal (95%CIbc = −.002 to .002) and suppression (95%CIbc = −.001 to .001) did not significantly mediate the relationship between conscientiousness and trait positive affect (Fig. 6).

Results of the mediation analysis from Study 2: effect of conscientiousness on trait PA. On the path from conscientiousness to trait PA the direct effect is shown on the arrow above, and the total effect (the effect without controlling for the mediator variables) is shown on the arrow below. The entries are unstandardised effects. Solid arrows reflect significant effects (** p < .01. * p < .05)

Discussion

The aim of the present research was to elucidate the role of Big Five personality domains and strategies of emotion regulation in well-being. In a series of two studies ran on two separate participant groups, we found that significant predictors of higher life satisfaction were greater extraversion, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and reappraisal, as well as lower suppression of emotions. Furthermore, greater positive affect was significantly predicted by higher extraversion, emotional stability, conscientiousness and reappraisal strategy, while negative affect was predicted only by lower emotional stability. Moreover, mediation models showed that suppression mediated the link between extraversion and life satisfaction, whereas reappraisal mediated the link between: emotional stability (low neuroticism) and: (1) life satisfaction and (2) positive affect. Below, we discuss these findings in more detail.

Emotional stability was positively associated with life satisfaction, positive affect and negatively with negative affect. These findings are consistent with those of previous research, which demonstrated that this personality trait fosters lowered levels of cognitive and affective components of SWB (Diener and Lucas 1999). It should be noted, however, that amongst the two facets of affect, the one theoretically related to neuroticism is negative affect, whereas positive affect is considered to be an aspect of extraversion (Rusting and Larsen 1997). Nevertheless, empirical findings show that neuroticism does associate with positive affect as well (Costa and McCrae 1980). Therefore, our results strengthen this position. On the other hand, effects of neuroticism on positive affect can likely be ascribed, at least in part, to the common variance between neuroticism and extraversion.

We considered life satisfaction and affect as the DVs separately in both studies, but it must be kept in mind that it is rather affective components that mediate the impact of personality on life satisfaction (Schimmack et al. 2002). Therefore, it seemed reasonable to consider emotion regulation strategies as a vital link on a path leading from neuroticism (low emotional stability) to SWB. Nevertheless, future studies could directly test the serial mediation hypothesis, where neuroticism impacts reappraisal that in turn influences affect, and it is affect that finally shapes life satisfaction.

Wang et al. (2009) showed that in a Chinese group of participants, neuroticism contributed to negative affect partly via reappraisal, but not via suppression. These authors did not test the path from neuroticism to positive affect, nor did they test life satisfaction in their mediation model. Thus, our results corroborate the observation that reappraisal is an emotion regulation strategy that can be ascribed to neuroticism. This partly explains its impact on affect (Gross and John 2003; John and Gross 2004; Ochsner et al. 2002). Our results, however, also extend observations made by Wang and co-workers (Wang et al. Wang et al. 2009), by showing that reappraisal also mediates effects of neuroticism on positive affect and life satisfaction. Interestingly, reappraisal plays a role here for “positive” aspects of SWB such as satisfaction and positive affect, rather than negative aspects (e.g., negative affect). It is possible that inability to reappraise emotional content prevents people high in neuroticism from experiencing positive emotionality. This explanation is consistent with John and Gross (2004), who suggested that since reappraisal occurs early in the emotion-generative process, persons with high level of neuroticism may be too overwhelmed by emotions to use this strategy.

The negative association between extraversion and suppression is consistent with previous findings (John and Gross 2004; Purnamaningsih 2017), as well as the theoretical characteristic of extraversion (Eysenck 1967). Furthermore, Study 1 revealed that suppression mediated the relationship between extraversion and life satisfaction. This result might be explained in several ways. First, as mentioned above, John and Gross (2004) emphasized the role of sociability, the main aspect of extraversion. They suggested that suppression might give rise to social costs. Specifically, the suppressor may appear avoidant, disconnected from the interaction. This may result in a sense of not being true to oneself and inauthentic to other people, which in turn may result in negative feelings about oneself and alienation of the individual, which makes developing close relationships difficult (John and Gross 2004). Extraverts’ tendency to openly express their feelings in social situations may counteract all the negative consequences related to suppression and promote more authentic relations with others. Consequently, extraverts may be more satisfied with their life.

Another explanation of the low suppression role in extraversion and well-being might be based on more general characteristics of extraversion. Extraversion is believed to reflect the manifestation of sensitivity to reward (e.g., Smillie 2013). According to Gray (1981), extraverts are more sensitive to reward than punishment cues due to the dominating behavioral activation system. Reward signals produce pleasantness, which, in turn, leads to positive mood. Moreover, extraversion is the trait linked to dopamine (Smillie 2013), which was demonstrated to be the major neurotransmitter connected to incentive reward and exploration (DeYoung 2013). The high levels of the behavioral activation system and approach motivation certainly reduce suppression, which inhibits rather than encourages affective response. Thus low levels of suppression, observed among extraverts, might be a consequence of the increased tendency to explore one’s surroundings and sensitivity toward reward. The latter, in turn, may enhance SWB in extraversion.

Present research provides important information about the relationships between personality factors, emotion regulation and well-being. However, it is itself not devoid of limitations. Firstly, studies reported in the present paper have a cross-sectional character. Taking the nature of tested relationship patterns into account (e.g., mediational models), longitudinal studies would provide an even stronger and more appropriate test of our hypothesis. This issue should be addressed in future studies. Secondly, in our studies, we examined the role of habitual use of emotion regulation strategies in the relationship between personality and well-being. However, one may wonder how personality would interact with emotion regulation in predicting affect in an experimental context, e.g. when participants are instructed to use a particular strategy. Conducting such experimental research would supplement our correlational studies, and could show whether personality traits can overcome the habitual processes in emotion regulation. Another important issue is that many of effects obtained in our analyses are small in size (r between .10 and .30; Cohen 1992), which suggests the need for future replication studies. Both of our studies were also based on samples of Polish students. Although the used tools were shown to be valid and reliable for Polish participants (as described in Method section), we are aware of the possible cultural differences that may limit the generalizability of our findings. For example, some former studies had shown differences between independent and collective cultures in the affective and social consequences of using reappraisal and suppression (Mesquita et al. 2014). Researchers had reported differences between independent and collective cultures in factors that shape well-being (Kitayama and Markus 2000) and well as links between personality traits and Hofstede’s dimensions of culture (Hofstede and McCrae 2004). Poland, as a more independent (rather than collective) country (Hofstede 2011), is more similar to United States, where most of the studies, on which we based our predictions, had been conducted. We suggest that our results may reflect the reality of independent cultures rather than the interdependent ones. The topic of cultural differences in relationships between personality, emotion regulation and well-being should be given more attention and is worth directly addressing in future research.

References

Aldao, A., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2012a). The influence of context on the implementation of adaptive emotion regulation strategies. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50, 493–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2012.04.004.

Aldao, A., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2012b). When are adaptive strategies most predictive of psychopathology? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 121, 276–281. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023598.

Aldao, A., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Schweizer, S. (2010). Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 217–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004.

Bloch, L., Moran, E. K., & Kring, A. M. (2010). On the need for conceptual and definitional clarity in emotion regulation research on psychopathology. In A. M. Kring & D. M. Sloan (Eds.), Emotion regulation and psychopathology: A transdiagnostic approach to etiology and treatment (pp. 88–104). New York: Guilford.

Brzozowski, P. (2010) Skala uczuć pozytywnych i negatywnych SUPIN: polska adaptacja skali PANAS Davida Watsona i Lee Ann Clark. [Polish adaptation of the PANAS by David Watson and Lee Ann Clark]. Warsaw, Poland: PTP.

Campos, J. J., Frankel, C. B., & Camras, L. (2004). On the nature of emotion regulation. Child Development, 75, 377–394. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00681.x.

Catalino, L. I., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2011). A Tuesday in the life of a flourisher: The role of positive emotional reactivity in optimal mental health. Emotion, 11, 938–950. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024889.

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 155–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155.

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1980). Influence of extraversion and neuroticism on subjective well-being: Happy and unhappy people. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38, 668–678. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.38.4.668.

Cutuli D. (2014). Cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression strategies role in the emotion regulation: an overview on their modulatory effects and neural correlates. Frontiers in systems neuroscience, 8(175). https://doi.org/10.3389/fnsys.2014.00175.

Dan Glause, E. S., & Gross, J. J. (2011). The temporal dynamics of two response-focused forms of emotion regulation: experiential, expressive, and autonomic consequences. Psychophysiology, 48, 1309–1322. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.2011.01191.x.

DeNeve, K. M., & Cooper, H. (1998). The happy personality: A meta-analysis of 137 personality traits and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 124, 197–229. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.124.2.197.

DeSteno, D., Goss, J. J., & Kubzansky, L. (2013). Affective science and health: The importance of emotion and emotion regulation. Health Psychology, 32, 474–486. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030259-2909.124.2.197.

DeYoung, C. G. (2013). The neuromodulator of exploration: A unifying theory of the role of dopamine in personality. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 762. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2013.00762.

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 542–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542.

Diener, E., & Lucas, R. (1999). Personality and subjective well-being. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13.

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 276–302. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276.

Etkin, A., & Wager, T. D. (2007). Functional neuroimaging of anxiety: A meta-analysis of emotional processing in PTSD, social anxiety disorder, and specific phobia. American Journal of Psychiatry, 164, 1476–1488. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07030504.

Eysenck, H. J. (1967). The biological basis of personality. Springfield: Thomas.

Finley, A., Crowell, A., Harmon-Jones, E., & Schmeichel, B. (2016). The influence of agreeableness and ego depletion on emotional responding. Journal of Personality, 85, 643–657. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12267.

Frijda, N. (2007). The laws of emotion. Mahwah: Erlbaum.

Garnefski, N., Kraaij, V., & Spinhoven, P. (2001). Negative life events, cognitive emotion regulation and depression. Personality and Individual Differences, 30, 1311–1327. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00113-6.

Gartz, K. L., & Roemer, L. (2004). Dysregulation: development, factor structure, and initial validation of the differences in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(1), 41–55.

Goldberg, L. R. (1992). The development of markers for the Big-Five factor structure. Psychological Assessment, 4, 26–42. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.4.1.26.

Goryńska, E., Winiewski, M., & Zajenkowski, M. (2015). Situational factors and personality traits as determinants of college students’ mood. Personality and Individual Differences, 77, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.12.027.

Gray, J. A. (1981). A critique of Eysenck’s theory of personality. In H. J. Eysenck (Ed.), A model for personality. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

Gross, J. J. (1998). Antecedent- and response-focused emotion regulation: Divergent consequences for experience, expression, and physiology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 224–237. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.1.224.

Gross, J. J. (2002). Emotion regulation: Affective, cognitive and social consequences. Psychophysiology, 39, 281–291. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0048577201393198.

Gross, J. J. (2014). Handbook of emotion regulation (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford.

Gross, J. J. (2015a). Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospects. Psychological Inquiry, 26, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2014.940781.

Gross, J. J. (2015b). The extended process model of emotion regulation: Elaborations, applications, and future directions. Psychological Inquiry, 26, 130–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2015.989751.

Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 348–362. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348.

Gross, J. J., & Levenson, R. W. (1993). Emotional suppression: Physiology, self-report, and expressive behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 970–986. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.64.6.970.

Gross, J. J., Feldman Barrett, L., & Richards, J. M. (1998). Emotion regulation in everyday life. (Unpublished manuscript).

Gross, J. J., Uusberg, H., & Uusberg, A. (2019). Mental illness and well-being: an affect regulation perspective. World Psychiatry, 18, 130–139.

Hayes, A. F. (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2014.962683.

Headey, B., & Wearing, A. (1989). Personality, life events, and subjective well-being: Toward a dynamic equilibrium model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 731–739. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.4.731.

Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing Cultures: The Hofstede Model in Context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1014.

Hofstede, G., & McCrae, R. R. (2004). Culture and personality revisited: Linking traits and dimensions of culture. Cross-Cultural Research, 38, 52–88.

Jankowski, K. S. (2015). Is the shift in chronotype associated with an alteration in well-being? Biological Rhythm Research, 46, 237–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/09291016.2014.985000.

Jazaieri, H., Urry, H. L., & Gross, J. J. (2013). Affective disturbance and psychopathology: An emotion regulation perspective. Journal of Experimental Psychopathology, 4, 584–599. https://doi.org/10.5127/jep.030312.

John, O. P., & Gross, J. J. (2004). Healthy and unhealthy emotion regulation: Personality processes, individual differences, and life span development. Journal of Personality, 72, 1301–1334. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00298.x.

Kitayama, S., & Markus, H. R. (2000). The pursuit of happiness and the realization of sympathy: cultural patterns of self, social relations, and well-being. In E. Diener & E. Suh (Eds.), Subjective well-being across cultures (pp. 113–161). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Kobylińska, D., Lewczuk, K., Marchlewska, M., & Pietraszek, A. (2018). For body and mind: practicing yoga and emotion regulation. Social Psychological Bulletin, 13, Article e25502. https://doi.org/10.5964/spb.v13i1.25502

Koole, S. L. (2009). The psychology of emotion regulation. Cognition and Emotion, 23, 4–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930802619031.

Koole, S. L., Schwager, S., & Rothermund, K. (2015). Resilience is more about being flexible than about staying positive. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 38, 109. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930802619031.

Kring, A. M., & Sloan, D. S. (2009). Emotion regulation and psychopathology. New York: Guilford.

Larsen, J. K., Vermulst, A. A., Geenen, R., van Middendorp, H., English, T., Gross, J. J., Ha, T., Evers, K. Engels, R. (2012). Emotion regulation in adolescence: a prospective study of expressive suppression and depressive symptoms. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 33(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431611432712.

Luhmann, M., Hofmann, W., Eid, M., & Lucas, R. E. (2012). Subjective well-being and adaptation to life events: A meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102, 592–615. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025948.

Lykken, D., & Tellegen, A. (1996). Happiness is a stochastic phenomenon. Psychological Science, 7, 186–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.1996.tb00355.x.

Lyubomirsky, S., Sheldon, K. M., & Schkade, D. (2005). Pursuing happiness: The architecture of sustainable change. Review of General Psychology, 9, 111–131. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.9.2.111.

Magnus, K., Diener, E., Fujita, F., & Pavot, W. (1993). Extraversion and neuroticism as predictors of objective life events: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 1046–1053. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.65.5.1046.

Matthews, G., Deary, I., & Whiteman, A. (2009). Personality traits. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mauss, I. B., & Gross, J. J. (2004). Emotion suppression and cardiovascular disease: Is hiding feelings bad for your heart? In I. Nyklicek, L. Temoshok, & A. Vingerhoets (Eds.), Emotional expression and health: Advances in theory, assessment, and clinical applications (pp. 62–81). New York: Brunner-Routledge.

Meier, B. P., & Robinson, M. D. (2004). Does quick to blame mean quick to anger? The role of agreeableness in dissociating the blame/anger relationship? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 856–867. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167204264764.

Meier, B. P., Robinson, M. D., & Wilkowski, B. M. (2006). Turning the other cheek: Agreeableness and the regulation of aggression-related primes. Psychological Science, 17, 136–142. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01676.x.

Mesquita, B., De Leersnyder, J., & Albert, D. (2014). The cultural regulation of emotions. In J. J. Gross (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation (2nd ed., pp. 284–301). New York: Guilford Press.

Moore, S. A., Zoellner, L. A., & Mollenholt, N. (2008). Are expressive suppression and cognitive reappraisal associated with stress-related symptoms? Behavioural Research and Therapy, 46, 993–1000. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2008.05.001.

Nyklicek, I., Vingerhoets, A., Zeelenberg, M., & Denollet, J. (2011). Emotion regulation and well-being. New York: Springer.

Ochsner, K. N., & Gross, J. J. (2008). Cognitive emotion regulation: Insights from social cognitive and affective neuroscience. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17, 153–158. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00566.x.

Ochsner, K. N., & Gross, J. J. (2014). The neural bases of emotion and emotion regulation: A valuation perspective. In J. J. Gross (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation (2nd ed., pp. 23–42). New York: Guilford.

Ochsner, K. N., Bunge, S. A., Gross, J. J., & Gabrieli, J. D. E. (2002). Rethinking feelings: An fMRI study of the cognitive regulation of emotion. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 14, 1215–1229. https://doi.org/10.1162/089892902760807212.

Purnamaningsih, E. H. (2017). Personality and emotion regulation strategies. International Journal of Psychological Research, 10, 53–60. https://doi.org/10.21500/20112084.2040.

Rosenthal, M. Z., Gratz, K. L., Kosson, D. S., et al. (2008). Borderline personality disorder and emotional responding: a review of the research literature. Clinical Psychology Review, 28, 75–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.04.001.

Rusting, C. L., & Larsen, R. J. (1997). Extraversion, neuroticism, and susceptibility to positive and negative affect: A test of two theoretical models. Personality and Individual Differences, 22(5), 607–612. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(96)00246-2.

Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 719–727.

Salovey, P., Detweiler-Bedell, B. T., Detweiler-Bedell, J. B., & Mayer, D. (2010). Emotional intelligence. In M. Lewis, J. M. Haviland-Jones, & L. Feldman Barrett (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (2nd ed., pp. 533–547). New York: Guilford.

Schimmack, U., Radhakrishnan, P., Oishi, S., Dzokoto, V., & Ahadi, S. (2002). Culture, personality, and subjective well-being: integrating process models of life-satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 582–593. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.4.582.

Schwager, S., & Rothermund, K. (2014). The automatic basis of resilience: Adaptive regulation of affect and cognition. In M. Kent, M. C. Davis, & J. W. Reich (Eds.), The resilience handbook: Approaches to stress and trauma (pp. 55–72). New York: Routledge.

Śmieja, M., Mrozowicz, M., & Kobylińska, D. (2011). Emotional intelligence and emotion regulation strategies. Studia Psychologiczne, 49, 55–64.

Smillie, L. D. (2013). Extraversion and reward processing. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22, 167–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721412470133.

Soto, C. J. (2015). Is happiness good for your personality? Concurrent and prospective relations of the Big Five with subjective well-being. Journal of Personality, 83, 45–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12081.

Srivastava, S., Tamir, M., McGonigal, K. M., John, O. P., & Gross, J. J. (2009). The social cost of emotional suppression: A prospective study of the transition to college. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96, 883–897. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014755.

Steel, P., Schmidt, J., & Shultz, J. (2008). Refining the relationship between personality and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 138–161. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.134.1.138.

Strus, W., Cieciuch, J., & Rowiński, T. (2014). Polska adaptacja kwestionariusza IPIP-BFM-50 do pomiaru pięciu cech osobowości w ujęciu leksykalnym [Polish adaptation of IPIP-BFM-50 measuring five personality traits in a lexical approach]. Roczniki Psychologiczne, 17, 327–346.

Tamir, M. (2009). Differential preferences for happiness: extraversion and trait-consistent emotion regulation. Journal of Personality, 77, 447–470. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00554.x.

Thayer, R. E. (1989). The biopsychology of mood and arousal. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tobin, R. M., Graziano, W. G., Vanman, E. J., & Tassinary, L. G. (2000). Personality, emotional experience, and efforts to control emotions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 656–669. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.4.656.

Troy, A. S., Wilhelm, F. H., Shallcross, A. J., & Mauss, I. B. (2010). Seeing the silver lining: Cognitive reappraisal ability moderates the relationship between stress and depressive symptoms. Emotion, 10, 783–795. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020262.

Troy, A. S., Shallcross, A. J., & Mauss, I. B. (2013). A person-by-situation approach to emotion regulation: Cognitive reappraisal can either help or hurt, depending on the context. Psychological Science, 24, 2505–2014. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613496434.

Wang, L., Shi, Z., & Li, H. (2009). Neuroticism, extraversion, emotion regulation, negative affect and positive affect: The mediating roles of reappraisal and suppression. Social Behavior and Personality, 37, 193–194. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2009.37.2.193.

Watson, D. (2000). Mood and temperament. New York: Guilford.

Watson, D., Clark, A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect. The PANAS Scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063–1070. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063.

Weiss, A., Bates, T. C., & Luciano, M. (2008). Happiness is a personal(ity) thing: The genetics of personality and well-being in a representative sample. Psychological Science, 19, 205–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02068.x.

Werner, K. H., & Gross, J. J. (2010). Emotion regulation and psychopathology: A conceptual framework. In A. Kring & D. Sloan (Eds.), Emotion regulation and psychopathology: A transdiagnostic approach to etiology and treatment (pp. 13–37). New York: Guilford.

Zajenkowska, A., Zajenkowski, M., & Jankowski, K. (2015). The relationship between mood experienced during an exam, proneness to frustration and neuroticism. Learning and Individual Differences, 37, 237–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2014.11.014.

Zajenkowski, M., & Matthews, G. (2019). Intellect and openness differentially predict affect: Perceived and objective cognitive ability contexts. Personality and Individual Differences, 137, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.08.001.

Zajenkowski, M., Goryńska, E., & Winiewski, M. (2012). Variability of the relationship between personality and mood. Personality and Individual Differences, 52, 858–861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.01.007.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

All the Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kobylińska, D., Zajenkowski, M., Lewczuk, K. et al. The mediational role of emotion regulation in the relationship between personality and subjective well-being. Curr Psychol 41, 4098–4111 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00861-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00861-7