Abstract

Background and objectives

Despite anecdotal evidence pointing to the high prevalence of job stress and burnout among dietitians and nutritionists, few studies have been conducted on this topic. Moreover, most studies are from Western countries. The objective of the current study, based on systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression, is aimed to provide systematically graded evidence to assess the prevalence of emotional burnout among dietitians and nutritionists across age, sex, and cultural backgrounds.

Methods

Two reviewers independently conducted a systematic search from 1 January 2000, to 1 April 2024 and was later updated to 15 November 2024, across seven databases: EBSCOhost Research Platform, EMBASE, PubMed/MEDLINE, ProQuest, ScienceDirect, Scopus, and Web of Science. The DerSimonian-Laird method was utilized to pool the data in this meta-analysis. Data from a total of 12,166 dietitians and nutritionists were extracted from 16 datasets (published in twelve research reports) covering a period of approximately 25 years. We measured the pooled prevalence of global burnout syndrome and its individual symptoms among dietitians and nutritionists. Subgroup meta-analyses were also conducted to identify a comprehensive set of moderators, including participants’ age and sex.

Results

The prevalence of global burnout syndrome in dietitians and nutritionists (K = 10, N = 10,081) showed an overall prevalence rate of 40.43% [23.69; 59.74], I² = 99.3%, τ [95% CI] = 1.18 [0.84; 1.97], τ² [95% CI] = 1.38 [0.71; 3.89], H [95% CI] = 12.68 [11.70; 13.74]. The prevalence of burnout dimensions/individual symptoms in dietitians and nutritionists (K = 2, N = 695) is summarized as follows: emotional exhaustion (EE) at 26.11% [15.14; 41.17], I² = 84.0%, τ = 0.21, τ² = 0.46, Q = 6.25, p < 0.001; depersonalization (DP) at 6.59% [1.08; 31.22], I² = 95.0%, τ = 1.72, τ² = 1.31, Q = 20.18, p < 0.001; and personal accomplishment (PA) at 59.29% [39.81; 76.23], I² = 89.3%, τ = 0.29, τ² = 0.54, Q = 9.36, p < 0.001. Meta-regression showed no difference by age or sex, p = 0.80, and p = 0.20, respectively.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis revealed that the prevalence of burnout among dietitians and nutritionists is as high as in other medical professionals. Furthermore, age and sex were not significantly associated with emotional burnout among dietitians and nutritionists. This study provides the impetus for policy changes to improve dietitians’ and nutritionists’ working conditions, as well as the overall quality of nutrition care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The concept of “burnout” describes the emotional and psychological stress faced by employees [1]. The term has been used to describe chronic exposure to job-related stress syndromes among workers [2], including staff working at facilities ranging from community hospitals to globally prominent tertiary health centers [3]. Registered dietitians and nutritionists are essential members of the healthcare team, especially for metabolic and psychological disorders that lead to obesity or excessive weight loss [4]. Leiter and Schaufeli (1996) reported [5] that burnout could occur in any occupation. The term burnout has been validated and categorized by Maslach and Jackson (1981) [6] into three reliable subscales, including emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP), and lack of personal accomplishment (PA). Emotional exhaustion refers to a sense of overwhelming fatigue, detachment, and diminished capacity to function effectively. Depersonalization is a psychological phenomenon where an individual experiences a persistent or recurrent sense of detachment from their thoughts, feelings, or body. In the specific instance of burnout, it means losing the sense of “belongingness” in one’s work environment. Lack of personal accomplishment is related to one’s low satisfaction about work performance and accomplishment. Each subscale has the potential to have a significant impact on a person’s career trajectory and physical health [7].

Burnout among dietitians and nutritionists appears to be common. In Canada, where over 57% of dietitians had overall burnout scores that ranged from moderate to high with 19.96% for EE, 4.31% for DP, and 38.61% for PA [8]. Similar results were reported in the United State of America (USA), where the EE, DP, and PA subscale scores were 20.6%, 5.3%, 38.6%, respectively [7].

Dietitians and nutritionists are assigned various tasks to handle, including nutritional counseling, diet planning, nutritional assessment, purchasing and receiving food, financial/accounting management [9]. They may also be in charge of scheduling employees, processing paperwork, attending to customer needs, and working collaboratively with other professionals who have been identified as having compassion fatigue [9, 10]. Switching between different modes of thinking and working in these types of environments can cause mental stress, which can affect dietitians’ workload perception and make dietitians more vulnerable to burnout [10]. Generally, headaches, gastrointestinal problems, anxiety, irritation, hypercritical behavior, and muscle pain are all physical symptoms of burnout [7]. Dietitians and nutritionists, like other healthcare professionals, experience a direct link between their physical and mental well-being and their work performance and quality of life [11]. According to research, burnout can be a source of frustration, moral distress [4], traumatic stress [10], emotional fatigue, decreased performance, and increased health problems [12] in the workplace. Following a thorough scoping of the electronic databases (i.e., PubMed/MEDLINE, Web of Science, Scopus) and registration platforms (i.e., PROSPERO, Open Science Framework), we found no evidence of an existing or ongoing systematic review with or without meta-analysis on the prevalence of emotional burnout among dietitians and nutritionists. To address this knowledge gap, we systematically graded evidence to assess the prevalence of emotional burnout among dietitians and nutritionists across age, sex/gender, and cultural backgrounds. This meta-analysis was conducted to assess burnout globally in the workplace of dietitians and nutritionists with the goal of devising systemic solutions aimed at mitigation and relief.

Methods

In accordance with our aim of generating knowledge on the prevalence of burnout among dietitians and nutritionists, the flow diagram of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020) was utilized to select studies for inclusion [13]. The statistical analyses of this review were conducted and presented within the framework of the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) protocol, this is used to enhance the quality, structure, and utility of the meta-analysis study design [14].

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The included studies are relevant to burnout as a syndrome characterized by EE, DP, and decreased effectiveness in achieving PA in people who work with others. The following were the inclusion criteria for the included studies: 1) full research papers (cross-sectional, case-control, and cohort), 2) published in any Language before 15th November 2024, from both the Western and non-Western populations 3) focused on specific occupational, dietitians and nutritionists representing both sexes, 4) and reported burnout prevalence among dietitians and nutritionists. The Western countries were those classified as such by the United Nations [15]. Exclusion criteria included review articles, book chapters, abstracts, and unpublished data. Studies were excluded that: 1) reported non-dietitians and nutritionists; examined mental health issues, stress, or distress rather than the prevalence of dietitians and nutritionist burnout; 3) lacked access to the full-text articles despite contacting the authors.

Searching strategy

Two reviewers, OA and FFR, performed an independent and systematic search between the period of 1/1/2000 to 1/4/2024 and was later update to 15/11/2024 by using seven databases, including EBSCOhost Research Platform, EMBASE, PubMed/MEDLINE, ProQuest, ScienceDirect, Scopus, and Web of Science. For the database searches, the following keywords or the names of the subscales and lists were used to find appropriate studies and search: List A: dietitians [OR] dieticians [OR] nutritionist [OR] healthcare worker [OR] clinical nutritionist [OR] clinical dietitian, registered dietitians. List B: burnout [OR] emotional exhaustion [OR] depersonalization [OR] personal accomplishment [OR] job satisfaction. The detailed search process and PICO framework [16] are presented in Table 1.

Two reviewers (OA, and FFR) independently conducted a thorough screening process for all available studies identified for possible inclusion. Initially, titles of all studies were identified for their relevance to our research topic. Then, after narrowing down the selection, the abstracts were read to ensure that the content closely aligned with the inclusion criteria of our study. Finally, the remaining articles were fully reviewed to assess the data, quality and relevance in greater detail. Moreover, grey literature was inspected independently by two reviewers (OA, and FFR) considering the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and remove any duplicates.

Grey literature refers to theses, reports, policy literature, working papers, newsletters, official government documents, speeches, white papers, urban plans, and other types of information, is material created outside of standard publication and dissemination channels. If there was a disagreement (study’s suitability for review and inclusion), another pair of reviewers (HJ, and WH) was requested to make an independent assessment. If disagreement remained, a joint decision was made by the entire research team.

Measure, primary and secondary outcomes

According to Maslach and Jackson (1981) [6], job burnout has three dimensions/symptoms/subscales: (1) emotional exhaustion (EE) comprises of 9 items; (2) depersonalization (DP) comprises 5 items; and (3) professional accomplishment (PA) comprises 8 items. Each subscale has a frequency response scale with a 7-point Likert type (0 = never, 1 = a few times a year or less, 2 = once or less per month, 3 = a few times a month, 4 = once a week, 5 = a few times.

The primary outcomes are the mean prevalence of emotional burnout among dietitians and nutritionists as measured by EE, PA, and DP. Furthermore, we also provide a set of moderators, including a comparison of burnout prevalence based on participants’ age and sex.

Data collection and extraction

Two independent members of the study team (any two of: DS, MW, and FFR) extracted the following variables from included studies using a Microsoft Excel file to standardize data description: Authors’ names, year of publication, sample size, age, design, country of collection, reported prevalence estimates of burnout, and measure used. Missing data in the articles were obtained by one of the coauthors (HJ) emailing the corresponding authors as needed.

Quality assessment of included studies

An independent evaluation was conducted by two authors (FFR and OA) to assess the quality score and risk of bias of the included studies using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) [17]. This scale is based on three main factors, including participant representativeness and selection, comparisons, and results and statistics. Three levels of quality rating were used for dividing lines and ranged from high quality to poor quality. Studies having a score of higher than 8 are considered high quality with a low risk of bias. Those with a borderline score between 5 and 7 have moderate quality associated with a moderate risk of bias. Scores ranging from 0 to 4 indicate poor quality and a high risk of bias.

Quality of evidence grading using GRADE

The quality of evidence was evaluated using the Grading approach of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach [18], which is based on four dimensions of risk of bias: results inconsistency, evidence indirectness, effect size imprecision, and publication bias. The overall quality of evidence is rated as “high risk,” “moderate risk,” “low risk,” or “very low risk.” When evaluating the strength of the evidence, data synthesis is influenced by the quality of the evidence assessment.

Data synthesis, data visualization, and statistical analyses

In this meta-analysis, we pooled the data using the DerSimonian-Laird method [19]. We reported the pooled prevalence and the 95% confidence interval for each study according to the random-effects model. To evaluate variability between studies, we used the I2 statistic, with values between 75 and 100% indicating a high level of heterogeneity [20]. Additionally, we explored the sources of this variability through Cochran’s Q statistics [21], tau2 (τ2), and tau (τ) (Higgins & Thompson, 2002). The H statistic was calculated as the square root of the Cochran’s χ2 heterogeneity statistic divided by the degree of freedom [22]. We employed a simplified Galbraith radial plot to visually represent heterogeneity [23].

To ensure that no single study disproportionately affected the results, we conducted a Jackknife sensitivity analysis, removing one study at a time and repeating the meta-analysis for each iteration [24]. This approach helps identify and address outliers that can compromise the validity and robustness of the meta-analysis. Studies whose confidence intervals did not align with the pooled effect’s confidence interval were considered outliers and were examined through this sensitivity analysis [25].

A publication bias, which occurs when the likelihood of its being published is influenced by its results, was assessed initially using a funnel plot [26]. To correct for asymmetry in the funnel plots, indicating potential publication bias, we employed the trim and fill analysis to adjust the point estimates [27]. For a more thorough investigation of publication bias, we also used Peters’ correlations [28] and Egger’s regression [29].

Subgroup meta-analyses were performed by categorizing the data into subgroups based on the different burnout symptoms, allowing for comparisons across symptoms. These analyses helped to explore heterogeneous outcomes and address specific questions related to distinct populations or study characteristics [30].

Meta-regressions, which involves regression models using one or more explanatory factors to predict the outcome variable, was conducted to examine how age and sex might influence the overall results [22]. The regression coefficient in meta-regression indicates how changes in the explanatory variables affect the outcome variable [22].

All data analyses were conducted using R software Version 4.4.0 (April, 2024), with the ‘meta’ [31] and ‘metafor’ [32] packages used for classical meta-analytics procedures. Risk-of-bias plots were generated using the ‘robvis’ package for quality assessment [33], and a weighted summary plot was created to illustrate the proportion of information for each judgment domain [33].

Results

Study selection

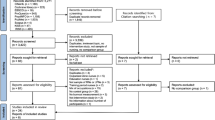

The initial search strategies produced a preliminary set of 337 potential papers. Specifically, EBSCOhost Research Platform = 51, EMBASE = 46, PubMed/MEDLINE = 52, ProQuest = 43, ScienceDirect = 46, Scopus = 48, and Web of Science = 49. Two papers were identified from grey literature. After removing 214 duplicates and ineligible articles, 77 published papers were reviewed based on titles and abstracts for eligibility. Out of these, 12 published studies (including 16 datasets) [7,8,9,10, 34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41] were found to meet the inclusion criteria (Table 2). Two studies [35, 37] did not report on global burnout syndrome; instead, they focused on individual burnout symptoms, specifically emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment. The reasons for excluding studies, as detailed in our PRISMA 2020 chart, include no data (n = 75), focused on the wrong population (n = 14), or were review articles (n = 3).

Characteristics of the included studies

The current systematic review and meta-analysis comprise 12 studies including 16 datasets) (K = 16) including a total of 12,166 individuals from six countries covering the period between January 2000 – mid-November 2024.

The plurality (42%) of the included studies were conducted in Western countries, while no study was conducted in more than one country. The percentage of included studies according to countries is shown as follows: USA (25%), Korea (17%), and others (58%), including Australia, Brazil, Canada, Japan, Portugal, Saudi Arabia, and Singapore (each contributing 8% of studies).

Five tools were used to measure the prevalence of emotional burnout among dietitians and nutritionists: Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI and MBI-HSS combined: 58%), Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI: 25%), Professional Quality of Life Scale (ProQOL: 8%), and Stress Impact Scale (SIS: 8%). MBI remained the most commonly used assessment tool.

The median sample size across studies was 102.5 participants (range: 4 to 8,038). The mean age of participants was 37.53 years (median: 38.35 years), and studies included a predominantly female population with a mean proportion of 92% female participants (median: 94%).

Figure 1 shows PRISMA 2020 flowchart of study selection for emotional burnout among dietitians and nutritionists.

PRISMA 2020 flowchart of study selection for emotional burnout among dietitians and nutritionists. Flowchart of the process for identifying studies for inclusion in the systematic review and meta-analysis. The steps involved in the identification, screening, and selection of studies are shown, including the number of records at each stage

Quality assessment and identification of total risk of bias

The quality assessment and total risk of bias of the included studies were determined using the NOS quality score in accordance to the following criteria: selection, comparability, and outcome as shown in Fig. 2 as traffic light plot. The overall risk of bias was distributed as follows: medium/moderate (50%) and low (50%) as shown in the summary plot in Fig. 3 and this is attributed to the risk of bias in sample selection.

Quality assessment/Traffic light plot of included studies using the NOS. Quality assessment of the included studies. The horizontal bars represent the assessment across different domains: Selection, Comparability, Outcome, and Overall. The color coding indicates the level of quality, with green representing low risk or high quality, yellow representing moderate risk or quality, and red representing critical risk or low quality

Summary plot of included studies. Risk of bias assessment for the included studies. The table shows the risk of bias across three domains: D1 (Selection), D2 (Comparability), and D3 (Outcome). The overall risk of bias is also provided for each study. The color coding indicates the level of risk, with green representing a low risk, yellow representing a moderate risk, and red representing a critical risk

Meta-analysis of emotional burnout among dietitians and nutritionists

Table 3 reports the characteristics of the included studies in this meta-analysis including number (K), samples (N), random effects model, heterogeneity tests, and publication bias of prevalence of emotional burnout among dietitians and nutritionists.

Global burnout syndrome

The prevalence of global burnout syndrome in dietitians and nutritionists (K = 10, N = 10,081) showed an overall prevalence rate of 40.43% [23.69; 59.74], I² = 99.3%, τ [95% CI] = 1.18 [0.84; 1.97], τ² [95% CI] = 1.38 [0.71; 3.89], H [95% CI] = 12.68 [11.70; 13.74] as shown in Fig. 4. Model fit statistics indicated the following: for the maximum-likelihood method, the log-likelihood was − 0.33, deviance was 50.09, AIC was 4.66, BIC was 5.26, and AICc was 6.37; for the restricted maximum-likelihood method, the log-likelihood was − 0.85, deviance was 1.70, AIC was 5.70, BIC was 6.09, and AICc was 7.70. Regarding publication bias assessment, the fail-safe N analysis revealed a fail-safe N of 6293.00 with a p-value of < 0.001, indicating a robust result. The Funnel plot is as shown in Fig. 5.

The cumulative prevalence (%), random effects model, and heterogeneity of global burnout syndrome and its symptoms among dietitians and nutritionists. Meta-analysis of the prevalence of the global burnout syndrome and its symptoms among dietitians and nutritionists across different studies. The forest plot visualizes the prevalence estimates and their 95% confidence intervals for each study

Funnel plot of included studies. The funnel plot/scatter plot shows the individual study proportions along with the overall density distribution. The density plot represents the estimated probability density function of the proportion across the studies, providing insights into the variability and spread of the observed proportions

In the random effects model, participants during COVID-19 had a proportion of 65.36% [95% CI: 24.27; 91.74] with k = 2 studies, τ² = 1.0367, and τ = 1.0182. For those during non-COVID-19, the proportion was 35.64% [95% CI: 18.67; 57.18] with k = 8 studies, τ² = 1.5063, and τ = 1.2273.

The test for subgroup differences in the random effects model indicated no significant difference between groups, with Q = 1.47, d.f. = 1, and p-value = 0.22. In the random effects model, participants from Western countries had a proportion of 35.13% [95% CI: 14.60; 63.17] with k = 5 studies, τ² = 1.7015, and τ = 1.3044. For those from non-Western countries, the proportion was 48.31% [95% CI: 27.33; 69.91] with k = 5 studies, τ² = 0.7679, and τ = 0.8763. The test for subgroup differences in the random effects model indicated no significant difference between groups, with Q = 0.53, d.f. = 1, and p-value = 0.47.

Individual burnout syndrome (EE, DP, PA)

The prevalence of EE symptoms in dietitians and nutritionists (K = 2, N = 695) showed an overall prevalence rate of 26.11% [15.14; 41.17], I² = 84.0%, τ [95% CI] = 0.21, τ² [95% CI] = 0.46, Q = 6.25, p-value < 0.001. The prevalence of DP symptoms in dietitians and nutritionists (K = 2, N = 695) indicated an overall prevalence rate of 6.59% [1.08; 31.22], I² = 95.0%, τ [95% CI] = 1.72, τ² [95% CI] = 1.31, Q = 20.18, p-value < 0.001.

The prevalence of reduced PA in dietitians and nutritionists (K = 2, N = 695) revealed an overall prevalence rate of 59.29% [39.81; 76.23], I² = 89.3%, τ [95% CI] = 0.29, τ² [95% CI] = 0.54, Q = 9.36, p-value < 0.001.

According to the analysis of meta-regression in Table 3, there were no differences either by age nor sex; i.e., p = 0.70, and p = 0.90, respectively. Consequently, age and sex are not associated with emotional burnout among dietitians and nutritionists. Figures 6 and 7 show bubble plots of the meta-regression line for age and sex, respectively.

Meta-regression between age and global burnout syndrome among dietitians and nutritionists. Scatterplot of the relationship between age and the modeled global burnout syndrome symptom score. Each datum (i.e., point on the graph) represents a study, with the size of the point proportional to the sample size. The red line shows the fitted linear regression line, indicating the overall trend of decreasing GBS symptom score with increasing age

Meta-regression between sex and global burnout syndrome dietitians and nutritionists. Scatterplot of the relationship between sex (proportion of women) and the modeled global burnout syndrome symptom score. Each data point represents a study, with the size of the point proportional to the sample size. The red line shows the fitted linear regression line, indicating the overall trend of decreasing global burnout syndrome symptom score with increasing proportion of women

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first thorough meta-analysis that uses the DerSimonian-Laird approach to investigate the prevalence of emotional burnout among dietitians and nutritionists. As with other health professions, there was a high rate of burnout among dietitians and nutritionists. More research is needed to better understand the effects of emotional and psychological stress, as well as the underlying mechanisms and causes of burnout. The ultimate goal is to identify approaches to reduce the burden of job stress and burnout globally in the workplace of dietitians and nutritionists. The results of the present systematic review and meta-analysis showed that the pooled prevalence of burnout was 40.4% for dietitians and nutritionists. To the best of our knowledge, the comparison between the different burnout levels in dietitians and nutritionists in published series remains limited. Indeed, so far, there has been no previous meta-analysis or systematic review published previously.

Burnout has been studied frequently and commonly has been found prevalent among different healthcare professionals. Literature reveals several meta-analyses that focused on analyzing burnout prevalence among diversified healthcare workers. Most of these meta-analyses are related to exploring burnout among nurses [42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55] and medical doctors [56,57,58,59,60,61,62]. Researchers have also conducted meta-analyses to analyze burnout among emergency department healthcare workers [63], plastic surgeons [61], ophthalmologists [64], dentists [65], psychiatrists [66], mental health professionals [67], midwives [68], occupational or physiotherapists [69,70,71], pulmonologists or respiratory therapists [72], speech-language pathologists [73], radiologists [74], and pharmacists [75]. Despite this rich literature, no systematic review or meta-analysis had thoroughly examined burnout prevalence among dietitians prior to our initiative. To the best of our knowledge, the current study was the first thorough meta-analysis that uses the DerSimonian-Laird approach to investigate the prevalence of emotional burnout among dietitians and nutritionists. By extracting data from 16 datasets involving 12,166 dietitians and nutritionists, our meta-analysis concluded that the prevalence of burnout among dietitians and nutritionists was 40%.

Because there was no earlier meta-analysis on the prevalence of burnout among dietitians and nutritionists, we compared our findings with other healthcare professions. We analyzed all the aforesaid meta-analyses in this regard [42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52, 54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75]. We excluded meta-analyses related to medical students, ones that focused on specific working conditions during COVID-19, and ones that did not report a point/pooled-prevalence percentage. Based on this comparative analysis involving various health specialists, we found that the level of burnout in dietitians and nutritionists (56%) is similar to the one found among emergency department healthcare workers (43%) [63], midwives (40%) [68], but higher rates compared to plastic surgeons (32%) [61], psychiatrists (26%) [66], dentists (13%) [65], physiotherapists (8%) [71], and lower than the upper bound found among nurses (up to 72%) [43, 46, 53], medical doctors (up to 72%) [56,57,58,59,60, 62], pulmonologists or respiratory therapists (62%) [72], and radiologists (83%) [74].

There were significant differences across geographical regions, professional specialties, and the type of burnout measurement tools employed. The Sub-Saharan African region reported the highest prevalence of burnout symptoms, while Europe and Central Asia reported the lowest [55]. Furthermore, another meta-analysis of eight studies found that EE prevalence was 28% (95%CI = 22–34%), high DP was 15% (95%CI = 9.23%), and poor PA was 31% (95%CI = 6–66%) among 1110 primary care nurses [50]. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 37 French research studies reported that the random effects pooled prevalence was 49% [76]. While it may be true that physician specialties deal more with death, there are certainly dietetic specialties that deal with death or life-threatening illness as well [76]. In European countries, the pooled prevalence rate of burnout was 7.7% [77]. The high heterogeneity result in our meta-analysis study necessitates caution when comparing burnout estimates across studies, as well as agreement on the description and measurement properties of burnout to allow a more consistent assessment of burnout worldwide.

Duarte and colleagues have reported that personal and organizational factors lead to burnout in the workplace among healthcare workers [36]. Workplace unhappiness (dissatisfaction), role uncertainty (confusion), and role ambiguity are examples of personal variables, whereas organizational ones include workload, excessive administrative chores, a lack of control, and client load [78]. Furthermore, the dietetic profession is interpersonal and emotionally charged, which is exacerbated by the numerous meanings and emotional charge that food contains for people throughout illness and disease, which may raise the risk of burnout for dietitians [8, 79, 80].

Dietitians and nutritionists are typically in charge of various responsibilities, including menu scheduling, economic/accounting management, purchasing, and management of food safety issues [9]. They also are in charge of employee scheduling, paperwork management, and customer service. Switching from one mode of thinking to another may cause mental stress, influencing dietitians’ perception of workload [81, 82]. Workplace misalignment also can contribute to work overload. Even if the workload is reasonable, employees may experience work overload if they lack the necessary skills or inclination for their job [83]. Furthermore, dietitians are trained to provide personalized food and nutrition plans and solutions [84], which may manage underlying complex social issues such as poverty and food insecurity [85]. Dietetics is concerned with individual eating habits influenced by the social environment and culture [86, 87]. Registered dietitians working with cancer patients and their families were found to often face eating-related distress, placing them in similarly high-stress environments as other healthcare professionals in oncology and palliative care [35]. Furthermore, the key finding of this study [35] was that burnout related to PA was significantly higher among registered dietitians working with cancer patients, compared to other oncology staff. In contrast, the proportion of individuals experiencing burnout related to EE was similar, while the proportion experiencing burnout related to DP was lower compared to other oncology staff.

Dietitians’ functions are evolving and expanding, according to various studies, as they play a critical role in medical management and operations, particularly in food service management, private practices, and research [81, 82]. They are subjected to several administrative procedures resembling those found in business [82]. The existence of difficulties connected to employment, pay allocation, workplace activities, career planning, decision-making, human resource development, legal compliance, and task planning [88]. All the mentioned circumstances could necessitate dietitians gaining extra food service management skills such as communication and leadership skills [89]. These types of skills are considered a strategic component in most industrial organizations and have an impact on the professional careers of the employees [89].

Burnout is usually associated with worker anxiety, disruption, social avoidance, self- criticism, depression, somatization, non-attendance, intention to depart, and actual turnover, as well as decreased productivity in those who stay on the job [90]. In addition, Job burnout, especially among dietitians and nutritionists, may restrict effective pathways for preventing or controlling nutrition-related chronic diseases, decrease public faith in dietitians, and influence the dynamics of the inter-professional healthcare team [8]. In particular, registered dietitians working with cancer patients were found to have some factors associated with burnout, including their experiences during nutrition counseling, their sense of contribution, and a less positive attitude toward caring for dying patients [35]. Moreover, registered dietitians frequently work with cancer patients and their families who experience severe eating-related distress in their daily practice. Additionally, appetite loss and malnutrition in advanced cancer patients often resist nutritional interventions. As a result, dietitians witness the decline in patients’ physical condition and their eventual passing [35]. The stress and burnout experienced by registered dietitians highlight the need for closer communication and collaboration among healthcare professionals, along with training in resilience, mindfulness, and empathy to help prevent burnout and stress [4, 91].

Previous research indicates that the prevalence of burnout differs by nation, and generalizing research findings may be difficult due to cultural differences that influence characteristics related to burnout and its prevalence [92, 93]. Furthermore, the etiology of burnout is based on an imbalance between job demands and available resources to meet demands [94]; this imbalance may differ significantly between countries.

The results of this study showed that there was no statistically significant difference in burnout based on sex or age. However, some studies reported that the burnout rate is higher among females than males, whereas others have found no difference [83]. Regarding age, some studies reported a higher burnout rate and work stress among younger workers [8, 95, 96] but ageing-related barriers are determined by job characteristics, and ageing is not always a barrier. A higher DP score was found to be significantly associated with several sociodemographic factors, including a lack of experience in proposing specific recipes for patients and families (p = 0.02), a need for guidance and guidelines on nutritional counseling (p = 0.009), fewer years of clinical experience (p = 0.01), and more overtime hours (p = 0.02) [35].

Strengths, limitations, and future directions

This meta-analysis provides clear guidance for understanding the causes and consequences of job stress for dietitians/ nutritionists specifically, although the literature review explored potential causes and consequences that relate to the role/roles of the dietitian. Future research with larger samples from different work settings, such as clinics, hospitals, and sports gyms, will help us better understand job stress and its consequences among dietitians and nutritionists. Workload perceptions of dietitians and nutritionists could be reduced through flexible schedules, computerization of repetitive tasks, and proper training. Dietitians’ perceptions of interpersonal conflict would improve in a supportive environment, such as proper and timely performance feedback from headquarters and cooperative relationships with client organizations.

The small number of studies focusing on burnout among dietitians and nutritionists was a limitation of this study. Most studies failed to address the job burnout sub-constructs (EE, DP, and diminished PA). In addition, most studies did not include symptoms or associated factors such as age, sex, and duration in the field, all of which can affect job burnout and could not easily be analyzed due to the differences in study designs. The majority of those represented in this systematic review and meta-analysis were women. Inadequate data influenced the outcomes and the interpretation. However, the data exploratory trimming method was used to identify the major data cluster in the final database. On the other hand, this analysis included research that used self-administered questionnaires (most notably MBI), which might have resulted in response biases. However, these study questionnaires are now the most extensively utilized in burnout studies, and MBI serves as the golden standard in particular [97].

Conclusion

This meta-analysis revealed that prevalence rates of burnout among dietitians and nutritionists were within the range of burnout among health professionals, which is high. This study provides momentum for legislative changes to improve the working circumstances of dietitians and nutritionists, as well as the overall quality of nutrition care. To enable universal comparisons of burnout prevalence across various settings, we argue that agreement on the definition and measurement aspects of burnout is necessary. This would be the first step toward developing interventions aimed at preventing and reducing burnout among dietitians and nutritionists. These interventions should be tailored to the particular socio-cultural and educational context. Work and workplace relationships both have an impact on job burnout. Workload and time constraints are stated to exacerbate burnout, especially the exhaustion dimension.

Data availability

Availability of data and materials: Data is available in Table 1.

Abbreviations

- AIC:

-

Akaike Information Criterion

- AICc:

-

Corrected Akaike Information Criterion

- BIC:

-

Bayesian Information Criterion

- CBI:

-

Copenhagen Burnout Inventory

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus Disease 2019

- DP:

-

Depersonalization

- EE:

-

Emotional Exhaustion

- GBS:

-

Global Burnout Syndrome

- GRADE:

-

Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

- I²:

-

I-squared (a measure of heterogeneity)

- MBI:

-

Maslach Burnout Inventory

- MOOSE:

-

Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology

- NOS:

-

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

- PA:

-

Personal Accomplishment

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- ProQOL:

-

Professional Quality of Life Scale

- Q:

-

Cochran’s Q statistic

- SIS:

-

Stress Impact Scale

- τ:

-

Tau (a measure of heterogeneity)

- τ²:

-

Tau-squared (a measure of heterogeneity)

References

Freudenberger HJ. Staff burn-out. J Soc Issues. 1974;30(1):159–65.

De Hert S. Burnout in healthcare workers: prevalence, impact and preventative strategies. Local Reg Anesth 2020:171–83.

Rotenstein LS, Torre M, Ramos MA, Rosales RC, Guille C, Sen S, Mata DA. Prevalence of burnout among physicians: a systematic review. JAMA. 2018;320(11):1131–50.

Eliot KA, Kolasa KM, Cuff PA. Stress and burnout in nutrition and dietetics: strengthening interprofessional ties. Nutr Today. 2018;53(2):63–7.

Leiter MP, Schaufeli WB. Consistency of the burnout construct across occupations. Anxiety Stress Coping. 1996;9(3):229–43.

Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J organizational Behav. 1981;2(2):99–113.

Fall ML, Wolf KN, Schiller MR, Wilson SL. Dietetic technicians report low to moderate levels of burnout. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103(11):1520–2.

Gingras J, De Jonge LA, Purdy N. Prevalence of dietitian burnout. J Hum Nutr Dietetics. 2010;23(3):238–43.

Lee K-H, Shin K-H. Job burnout, engagement and turnover intention of dietitians and chefs at a contract foodservice management company. J Community Nutr. 2005;7(2):100–6.

Osland E. An investigation into the P rofessional Q uality of L ife of dietitians working in acute care caseloads: are we doing enough to look after our own? J Hum Nutr dietetics. 2015;28(5):493–501.

Naja F, Radwan H, Cheikh Ismail L, Hashim M, Rida WH, Abu Qiyas S, Bou-Karroum K, Alameddine M. Practices and resilience of dieticians during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national survey in the United Arab Emirates. Hum Resour Health. 2021;19:1–12.

Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach burnout inventory: Scarecrow Education; 1997.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. bmj 2021, 372.

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–12.

Gupta RS, Kim JS, Barnathan JA, Amsden LB, Tummala LS, Holl JL. Food allergy knowledge, attitudes and beliefs: focus groups of parents, physicians and the general public. BMC Pediatr. 2008;8:1–10.

Schardt C, Adams MB, Owens T, Keitz S, Fontelo P. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med Inf Decis Mak. 2007;7:1–6.

Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. 2000.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924–6.

Jackson D, White IR, Thompson SG. Extending DerSimonian and Laird’s methodology to perform multivariate random effects meta-analyses. Stat Med. 2010;29(12):1282–97.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60.

Huedo-Medina TB, Sánchez-Meca J, Marín-Martínez F, Botella J. Assessing heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic or I² index? Psychol Methods. 2006;11(2):193.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–58.

Galbraith RF. Some applications of radial plots. J Am Stat Assoc. 1994;89(428):1232–42.

Patsopoulos NA, Evangelou E, Ioannidis JP. Sensitivity of between-study heterogeneity in meta-analysis: proposed metrics and empirical evaluation. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37(5):1148–57.

Viechtbauer W, Cheung MWL. Outlier and influence diagnostics for meta-analysis. Res synthesis methods. 2010;1(2):112–25.

Mathur MB, VanderWeele TJ. Sensitivity analysis for publication bias in meta-analyses. J Royal Stat Soc Ser C: Appl Stat. 2020;69(5):1091–119.

Duval S, Tweedie R. A nonparametric trim and fill method of accounting for publication bias in meta-analysis. J Am Stat Assoc. 2000;95(449):89–98.

Lin L, Chu H. Quantifying publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2018;74(3):785–94.

Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–34.

Sedgwick P. Meta-analyses: heterogeneity and subgroup analysis. BMJ. 2013;346.

Schwarzer G, Carpenter JR, Rücker G. Meta-analysis with R. Volume 4784. Springer; 2015.

Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J Stat Softw. 2010;36(3):1–48.

McGuinness LA, Higgins JP. Risk-of‐bias VISualization (robvis): an R package and Shiny web app for visualizing risk‐of‐bias assessments. Res synthesis methods. 2021;12(1):55–61.

Alqahtani N, Mohammad-Mahmood A. The Burnout Syndrome among Dietitians in Arar, Saudi Arabi. 2024.

Chitose H, Kuwana M, Miura T, Inoue M, Nagasu Y, Shimizu R, Hattori Y, Uehara Y, Kosugi K, Matsumoto Y. A Japanese nationwide survey of nutritional counseling for cancer patients and risk factors of burnout among registered dietitians. Palliat Med Rep. 2022;3(1):211–9.

Duarte I, Teixeira A, Castro L, Marina S, Ribeiro C, Jácome C, Martins V, Ribeiro-Vaz I, Pinheiro HC, Silva AR. Burnout among Portuguese healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1–10.

Lee K-E. Moderating effects of leader-member exchange (LMX) on job burnout in dietitians and chefs of institutional foodservice. Nutr Res Pract. 2011;5(1):80–7.

Lima VLMB, Ramos FJS, Suher PH, Souza MA, Zampieri FG, Machado FR. Freitas FGRd: Prevalence and risk factors of Burnout syndrome among intensive care unit members during the second wave of COVID-19: a single-center study. einstein (São Paulo). 2024;22:eAO0271.

Perdue CN. Emotional intelligence, job satisfaction, and burnout for dietitians. Walden University; 2016.

Teo YH, Xu JTK, Ho C, Leong JM, Tan BKJ, Tan EKH, Goh W-A, Neo E, Chua JYJ, Ng SJY. Factors associated with self-reported burnout level in allied healthcare professionals in a tertiary hospital in Singapore. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(1):e0244338.

Williams K, Eggett D, Patten EV. How work and family caregiving responsibilities interplay and affect registered dietitian nutritionists and their work: A national survey. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(3):e0248109.

De la Fuente-Solana EI, Suleiman-Martos N, Pradas-Hernandez L, Gomez-Urquiza JL, Canadas-De la Fuente GA, Albendín-García L. Prevalence, related factors, and levels of burnout syndrome among nurses working in gynecology and obstetrics services: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(14):2585.

Ge MW, Hu FH, Jia YJ, Tang W, Zhang WQ, Chen HL. Global prevalence of nursing burnout syndrome and temporal trends for the last 10 years: A meta-analysis of 94 studies covering over 30 countries. J Clin Nurs. 2023;32(17–18):5836–54.

Gómez-Urquiza JL, Albendín-García L, Velando-Soriano A, Ortega-Campos E, Ramírez-Baena L, Membrive-Jiménez MJ, Suleiman-Martos N. Burnout in palliative care nurses, prevalence and risk factors: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(20):7672.

Gómez-Urquiza JL, De la Fuente-Solana EI, Albendín-García L, Vargas-Pecino C, Ortega-Campos EM. Canadas-De la Fuente GA: Prevalence of burnout syndrome in emergency nurses: A meta-analysis. Crit Care Nurse. 2017;37(5):e1–9.

Khammar A, Dalvand S, Hashemian AH, Poursadeghiyan M, Yarmohammadi S, Babakhani J, Yarmohammadi H. Data for the prevalence of nurses׳ burnout in Iran (a meta-analysis dataset). Data brief. 2018;20:1779–86.

López-López IM, Gómez‐Urquiza JL, Cañadas GR, De la Fuente EI, Albendín‐García L. Cañadas‐De la Fuente GA: Prevalence of burnout in mental health nurses and related factors: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2019;28(5):1035–44.

Ma Y, Xie T, Zhang J, Yang H. The prevalence, related factors and interventions of oncology nurses’ burnout in different continents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Nurs. 2023;32(19–20):7050–61.

Membrive-Jiménez MJ, Pradas-Hernández L, Suleiman-Martos N, Vargas-Román K, Cañadas-De la Fuente GA, Gomez-Urquiza JL, De la Fuente-Solana EI. Burnout in nursing managers: a systematic review and meta-analysis of related factors, levels and prevalence. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(11):3983.

Monsalve-Reyes CS, San Luis-Costas C, Gómez-Urquiza JL, Albendín-García L, Aguayo R. Cañadas-De la Fuente GA: Burnout syndrome and its prevalence in primary care nursing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19:1–7.

Pradas-Hernández L, Ariza T, Gómez-Urquiza JL, Albendín-García L, De la Fuente EI. Cañadas-De la Fuente GA: Prevalence of burnout in paediatric nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(4):e0195039.

Ramírez-Elvira S, Romero-Béjar JL, Suleiman-Martos N, Gómez-Urquiza JL, Monsalve-Reyes C, Cañadas-De la Fuente GA, Albendín-García L. Prevalence, risk factors and burnout levels in intensive care unit nurses: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(21):11432.

Rezaei S, Karami Matin B, Hajizadeh M, Soroush A, Nouri B. Prevalence of burnout among nurses in Iran: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Nurs Rev. 2018;65(3):361–9.

Sohrabi Y, Yarmohammadi H, Pouya AB, Arefi MF, Hassanipour S, Poursadeqiyan M. Prevalence of job burnout in Iranian nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Work. 2022;73(3):937–43.

Woo T, Ho R, Tang A, Tam W. Global prevalence of burnout symptoms among nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2020;123:9–20.

Chirico F, Magnavita N. Burnout syndrome and meta-analyses: Need for evidence-based research in occupational health. comments on prevalence of burnout in medical and surgical residents: A meta-analysis. int. j. environ. res. public. health. 2019, 16, doi: 10.3390/ijerph16091479. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17(3):741.

Hiver C, Villa A, Bellagamba G, Lehucher-Michel M-P. Burnout prevalence among European physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2022:1–15.

Karuna C, Palmer V, Scott A, Gunn J. Prevalence of burnout among GPs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2022;72(718):e316–24.

Low ZX, Yeo KA, Sharma VK, Leung GK, McIntyre RS, Guerrero A, Lu B, Sin Fai Lam CC, Tran BX, Nguyen LH. Prevalence of burnout in medical and surgical residents: a meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(9):1479.

Pujol-de Castro A, Valerio-Rao G, Vaquero-Cepeda P, Catalá-López F. Prevalence of burnout syndrome in physicians working in Spain: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gac Sanit 2024:S0213–9111 (0224) 00031.

Ribeiro RV, Martuscelli OJ, Vieira AC, Vieira CF. Prevalence of burnout among plastic surgeons and residents in plastic surgery: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Plast Reconstr Surgery–Global Open. 2018;6(8):e1854.

Shen X, Xu H, Feng J, Ye J, Lu Z, Gan Y. The global prevalence of burnout among general practitioners: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fam Pract. 2022;39(5):943–50.

Alanazy ARM, Alruwaili A. The global prevalence and associated factors of burnout among emergency department healthcare workers and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Healthcare: 2023. MDPI; 2023. p. 2220.

Cheung R, Yu B, Iordanous Y, Malvankar-Mehta MS. The prevalence of occupational burnout among ophthalmologists: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Rep. 2021;124(5):2139–54.

Long H, Li Q, Zhong X, Yang L, Liu Y, Pu J, Yan L, Ji P, Jin X. The prevalence of professional burnout among dentists: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Health Med. 2023;28(7):1767–82.

Bykov KV, Zrazhevskaya IA, Topka EO, Peshkin VN, Dobrovolsky AP, Isaev RN, Orlov AM. Prevalence of burnout among psychiatrists: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2022;308:47–64.

O’Connor K, Neff DM, Pitman S. Burnout in mental health professionals: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence and determinants. Eur Psychiatry. 2018;53:74–99.

Suleiman-Martos N, Albendín-García L, Gómez-Urquiza JL, Vargas-Román K, Ramirez-Baena L, Ortega-Campos E, De La Fuente-Solana EI. Prevalence and predictors of burnout in midwives: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(2):641.

Clarke M, Frecklington M, Stewart S. Prevalence and Severity of Burnout Risk Among Musculoskeletal Allied Health Practitioners: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-analysis. Occup Health Sci 2024:1–26.

Park E-Y. Meta-Analysis of Factors Associated with Occupational Therapist Burnout. Occup therapy Int. 2021;2021(1):1226841.

Venturini E, Ugolini A, Bianchi L, Di Bari M, Paci M. Prevalence of burnout among physiotherapists: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Physiotherapy. 2024;124.

Bai X, Wan Z, Tang J, Zhang D, Shen K, Wu X, Qiao L, Zhou Y, Wang Y, Cheng W. The prevalence of burnout among pulmonologists or respiratory therapists pre-and post-COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Med. 2023;55(1):2234392.

Brito-Marcelino A, Oliva-Costa EF, Sarmento SCP, Carvalho AA. Burnout syndrome in speech-language pathologists and audiologists: a review. Revista Brasileira de Med do Trabalho. 2020;18(2):217.

Hassankhani A, Amoukhteh M, Valizadeh P, Jannatdoust P, Ghadimi DJ, Sabeghi P, Gholamrezanezhad A. A meta-analysis of burnout in radiology trainees and radiologists: insights from the Maslach Burnout Inventory. Acad Radiol. 2024;31(3):1198–216.

Dee J, Dhuhaibawi N, Hayden JC. A systematic review and pooled prevalence of burnout in pharmacists. Int J Clin Pharm. 2023;45(5):1027–36.

Kansoun Z, Boyer L, Hodgkinson M, Villes V, Lançon C, Fond G. Burnout in French physicians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2019;246:132–47.

Hiver C, Villa A, Bellagamba G, Lehucher-Michel MP. Burnout prevalence among European physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2022;95(1):259–73.

Solomonidou A, Katsounari I. Experiences of social workers in nongovernmental services in Cyprus leading to occupational stress and burnout. Int Social Work. 2022;65(1):83–97.

Aphramor L, Gingras J. Helping people change: promoting politicised practice in the health care professions. Debating obesity: Critical perspectives. edn.: Springer; 2011. pp. 192–218.

Gingras J. Evoking trust in the nutrition counselor: why should we be trusted? J Agric Environ Ethics. 2005;18:57–74.

Rusali R, Jamaluddin R, Md Yusop NB, Ghazali H. Management Responsibilities Among Dietitians: What is the Level of Job Satisfaction and Skills Involved? A Scoping Review. Malaysian J Med Health Sci 2020, 16(6).

Sauer K, Canter D, Shanklin C. Job satisfaction of dietitians with management responsibilities: an exploratory study supporting ADA’s research priorities. J Acad Nutr Dietetics. 2012;112(5 Suppl):S6–11.

Maslach C, Schaufeli W, Leiter M. Job B urnout. A nnu R ev P sychol. Job burnout Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52.

Beneficiaries, CoNSfM. The role of nutrition in maintaining health in the nation’s elderly: Evaluating coverage of nutrition services for the Medicare population. National Academies; 2000.

Wetherill MS, White KC, Rivera C. Food Insecurity and the Nutrition Care Process: Practical Applications for Dietetics Practitioners. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2018;118(12):2223–34.

Higgs S, Ruddock H. Social influences on eating. In Handbook of eating and drinking interdisciplinary perspectives: interdisciplinary perspectives. Heidelberg: Springer. 2020. pp. 277–91.

Raine KD. Determinants of healthy eating in Canada: an overview and synthesis. Can J Public Health. 2005;96(Suppl 3):S8–14.

Jayarathna DY, Weerakkody W. Impact of Administrative Practices on Job Performance: With Reference to Public Banks in Sri Lanka. 2015.

Maunder K, Walton K, Williams P, Ferguson M, Beck E. A framework for eHealth readiness of dietitians. Int J Med Informatics. 2018;115:43–52.

Carod-Artal FJ, Vázquez-Cabrera C. Burnout syndrome in an international setting. Burnout for experts: Prevention in the context of living and working. edn.: Springer; 2012. pp. 15–35.

Duarte J, Pinto-Gouveia J. Mindfulness, self-compassion and psychological inflexibility mediate the effects of a mindfulness-based intervention in a sample of oncology nurses. J Context Behav Sci. 2017;6(2):125–33.

Kumar S. Burnout and doctors: prevalence, prevention and intervention. In: Healthcare: 2016: MDPI; 2016: 37.

Malach Pines A. Occupational burnout: a cross-cultural Israeli Jewish‐Arab perspective and its implications for career counselling. Career Dev Int. 2003;8(2):97–106.

Bakker AB, Demerouti E. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. J managerial Psychol. 2007;22(3):309–28.

Soares J, Grossi G, Sundin Ö. Burnout among women: associations with demographic/socio-economic, work, life-style and health factors. Arch Women Ment Health. 2007;10:61–71.

Hsu H-C. Age differences in work stress, exhaustion, well-being, and related factors from an ecological perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(1):50.

Williamson K, Lank PM, Cheema N, Hartman N, Lovell EO. Comparing the Maslach Burnout Inventory to Other Well-Being Instruments in Emergency Medicine Residents. J Grad Med Educ. 2018;10(5):532–6.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, O.A.A., N.A.E., F.F.-R., M.W., D.H.S., W.H., A.A., K.T., J.R.H., and H.J.; Methodology, O.A.A., N.A.E., F.F.-R., M.W., D.H.S., W.H., A.A., K.T., J.R.H., and H.J.; Software, HJ; Formal Analysis, HJ; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, O.A.A., N.A.E., F.F.-R., M.W., D.H.S., W.H., A.A., K.T., J.R.H., and H.J.; Writing – Review & Editing, O.A.A., N.A.E., F.F.-R., M.W., D.H.S., W.H., A.A., K.T., J.R.H., and H.J.; Funding Acquisition, not applicable. All authors have seen and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

Not applicable. This is a systematic review and meta-analysis of published studies that are indexed in the public domain.

Informed consent

Not applicable. This is a systematic review and meta-analysis of published studies that are indexed in the public domain.

Consent for publication

Not applicable. This is a systematic review and meta-analysis of published studies that are indexed in the public domain.

Registration and protocol

The review protocol of this study was registered at Open Science Framework (OSF). Registration is available online at https://osf.io/j9nx5/ and the digital object identifier (DOI) is DOI: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/J9NX5.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alhaj, O.A., Elsahoryi, N.A., Fekih-Romdhane, F. et al. Prevalence of emotional burnout among dietitians and nutritionists: a systematic review, meta-analysis, meta-regression, and a call for action. BMC Psychol 12, 775 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-02290-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-02290-8