The paper presents some key lessons and "folk wisdom" that machine learning researchers and practitioners have learnt from experience and which are hard to find in textbooks.

All machine learning algorithms have three components:

- Representation for a learner is the set if classifiers/functions that can be possibly learnt. This set is called hypothesis space. If a function is not in hypothesis space, it can not be learnt.

- Evaluation function tells how good the machine learning model is.

- Optimisation is the method to search for the most optimal learning model.

The fundamental goal of machine learning is to generalize beyond the training set. The data used to evaluate the model must be kept separate from the data used to learn the model. When we use generalization as a goal, we do not have access to a function that we can optimize. So we have to use training error as a proxy for test error.

Since our ultimate goal is generalization (see point 2), there is no such thing as "enough" data. Some knowledge beyond the data is needed to generalize beyond the data. Another way to put is "No learner can beat random guessing over all possible functions." But instead of hard-coding assumptions, learners should allow assumptions to be explicitly stated, varied and incorporated automatically into the model.

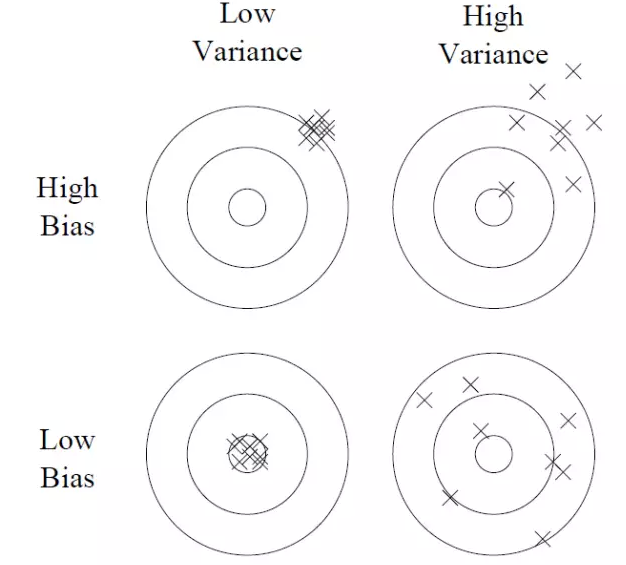

One way to interpret overfitting is to break down generalization error into two components: bias and variance. Bias is the tendency of the learner to constantly learn the same wrong thing (in the image, a high bias would mean more distance from the centre). Variance is the tendency to learn random things irrespective of the signal (in the image, a high variance would mean more scattered points).

A more powerful learner (one that can learn many models) need not be better than a less powerful one as they can have a high variance. While noise is not the only reason for overfitting, it can indeed aggravate the problem. Some tools against overfitting are - cross-validation, regularization, statistical significance testing, etc.

Generalizing correctly becomes exponentially harder as dimensionality (number of features) become large. Machine learning algorithms depend on similarity-based reasoning which breaks down in high dimensions as a fixed-size training set covers only a small fraction of the large input space. Moreover, our intuitions from three-dimensional space often do not apply to higher dimensional spaces. So the curse of dimensionality may outweigh the benefits of having more features. Though, in most cases, learners benefit from the blessing of non-uniformity as data points are concentrated in lower-dimensional manifolds. Learners can implicitly take advantage of this lower effective dimension or use dimensionality reduction techniques.

A common type of bound common when dealing with machine learning algorithms is related to the number of samples needed to ensure good generalization. But these bounds are very loose in nature. Moreover, the bound says that given a large enough training dataset, our learner would return a good hypothesis with high probability or would not find a consistent hypothesis. It does not tell us anything about how to select a good hypothesis space.

Another common type of bound is the asymptotic bound which says "given infinite data, the learner is guaranteed to output correct classifier". But in practice we never have infinite data and data alone is not enough (see point 3). So theoretical guarantees should be used to understand and drive the algorithm design and not as the only criteria to select algorithm.

Machine Learning is an iterative process where we train the learner, analyze the results, modify the learner/data and repeat. Feature engineering is a crucial step in this pipeline. Having the right kind of features (independent features that correlate well with the class) makes learning easier. But feature engineering is also difficult because it requires domain specific knowledge which extends beyond just the data at hand (see point 3).

As a rule of thumb, a dumb algorithm with lots of data beats a clever algorithm with a modest amount of data. But more data means more scalability issues. Fixed size learners (parametric learners) can take advantage of data only to an extent beyond which adding more data does not improve the results. Variable size learners (non-parametric learners) can, in theory, learn any function given sufficient amount of data. Of course, even non-parametric learners are bound by limitations of memory and computational power.

In early days of machine learning, the model/learner to be trained was pre-determined and the focus was on tuning it for optimal performance. Then the focus shifted to trying many variants of different learners. Now the focus is on combining the various variants of different algorithms to generate the most optimal results. Such model ensembling techniques include bagging, boosting and stacking.

Though Occam's razor suggests that machine learning models should be kept simple, there is no necessary connection between the number of parameters of a model and its tendency to overfit. The complexity of a model can be related to the size of hypothesis space as smaller spaces allow the hypothesis to be generated by smaller, simpler codes. But there is another side to this picture - A learner with a larger hypothesis space that tries fewer hypotheses is less likely to overfit than one that tries more hypotheses from a smaller space. So hypothesis space size is just a rough guide towards accuracy. Domingos conclude in his other paper that "simpler hypotheses should be preferred because simplicity is a virtue in its own right, not because of a hypothetical connection with accuracy."

Just because a function can be represented, does not mean that the function can actually be learnt. Restrictions imposed by data, time and memory, limit the functions that can actually be learnt in a feasible manner. For example, decision tree learners can not learn trees with more leaves than the number of training data points. The right question to ask is "whether a function can be learnt" and not "whether a function can be represented".

Correlation may hint towards a possible cause and effect relationship but that needs to be investigated and validated. On the face of it, correlation can not be taken as proof of causation.

Edit :

I write these summaries as part of my initiative called a-paper-a-week where in I committed myself to reading and summarising one research paper every week. You can find all the summaries here.

Easy to understand and clear. Good work!