TRIPS to Where? A Narrative Review of the Empirical Literature on Intellectual Property Licensing Models to Promote Global Diffusion of Essential Medicines

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Barriers to the Effective Use of TRIPS Flexibilities

1.2. Voluntary Licensing and Patent Medicines Patent Pools as New Access Paradigms

1.3. Rationale and Aims

2. Review Scope and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

3.2. Pooled and Bilateral VLs and Access to Medicines

3.2.1. Generic Drug Diffusion

Total Quantity and Price of Generic Drugs Purchased

3.2.2. Actual and Projected Cost Savings

3.2.3. Public Health Impact

3.2.4. Follow-On Innovation

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Main Findings

4.2. Challenges in Measuring Voluntary Licensing Impact on Access to Health

4.3. Future Research

4.3.1. Measuring the Effects of Different VL Practices in Different Settings

4.3.2. Qualitative Studies

4.3.3. Affordability and Budget Impact

4.3.4. Collaborative IP, TRIPS Flexibilities and Health Governance during COVID-19

4.4. Review Limitations

5. Concluding Remarks and Policy Implications

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wirtz, V.J.; Hogerzeil, H.V.; Gray, A.L.; Bigdeli, M.; de Joncheere, C.P.; Ewen, M.A.; Gyansa-Lutterodt, M.; Jing, S.; Luiza, V.L.; Mbindyo, R.M.; et al. Essential Medicines for Universal Health Coverage. Lancet 2017, 389, 403–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampat, B.N. Academic Patents and Access to Medicines in Developing Countries. Am. J. Public Health 2009, 99, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Model Lists of Essential Medicines. Available online: https://www.who.int/groups/expert-committee-on-selection-and-use-of-essential-medicines/essential-medicines-lists (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Owoeye, O.; Olatunji, O.; Faturoti, B. Patents and the Trans-Pacific Partnership: How TPP-Style Intellectual Property Standards May Exacerbate the Access to Medicines Problem in the East African Community. Int. Trade J. 2019, 33, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, S.; Goldberg, P.K.; Jia, P. Estimating the Effects of Global Patent Protection in Pharmaceuticals: A Case Study of Quinolones in India. Am. Econ. Rev. 2006, 96, 1477–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Beall, R.F.; Attaran, A. A Method for Understanding Generic Procurement of HIV Medicines by Developing Countries with Patent Protection. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 185, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoen, E.; Veraldi, J.; Toebes, B.; Hogerzeil, H.V. Medicine Procurement and the Use of Flexibilities in the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, 2001–2016. Bull. World Health Organ. 2018, 96, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Office of the United States Trade Representative 2019 Special 301 Report. 2019. Available online: https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/press-office/reports-and-publications/2019/2019-special-301-report (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Adekola, T.A. Public Health–Oriented Intellectual Property and Trade Policies in Africa and the Regional Mechanism under Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights Amendment. Public Health 2019, 173, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hingun, M.; Nizamuddin, R.M. Incorporating Article 31bis Flexibilities on Trips Public Health into Domestic Patent System: The Inescapable Way Forward for Malaysia. J. Int. Stud. 2020, 16, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morten, C.; Duan, C. Who’s Afraid of Section 1498? A Case for Government Patent Use in Pandemics and Other National Crises. Yale J. Law Technol. 2020, 23, 1–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drugs for Neglected Diseases (DNDi). Medicines for the People Annual Report 2020; Drugs for Neglected Diseases (DNDi): Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, M. Ten Years in Public Health, 2007–2017; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, S.; Bermudez, J.; Hoen, E. Innovation and Access to Medicines for Neglected Populations: Could a Treaty Address a Broken Pharmaceutical R&D System? PLoS Med. 2012, 9, e1001218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keestra, S.; Osborne, R.; Rodgers, F.; Wimmer, S. University Patenting and Licensing Practices in the United Kingdom during the COVID-19 Pandemic—Implications for Global Equitable Access to COVID-19 Health Technologies. medRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crager, S.E.; Guillen, E.; Price, M. University Contributions to the HPV Vaccine and Implications for Access to Vaccines in Developing Countries: Addressing Materials and Know-How in University Technology Transfer Policy. Am. J. Law Med. 2009, 35, 253–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Islam, M.D.; Kaplan, W.A.; Trachtenberg, D.; Thrasher, R.; Gallagher, K.P.; Wirtz, V.J. Impacts of Intellectual Property Provisions in Trade Treaties on Access to Medicine in Low and Middle Income Countries: A Systematic Review. Glob. Health 2019, 15, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vondeling, G.T.; Cao, Q.; Postma, M.J.; Rozenbaum, M.H. The Impact of Patent Expiry on Drug Prices: A Systematic Literature Review. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 2018, 16, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Urias, E.; Ramani, S.V. Access to Medicines after TRIPS: Is Compulsory Licensing an Effective Mechanism to Lower Drug Prices? A Review of the Existing Evidence. J. Int. Bus. Policy 2020, 3, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Schans, S.; Vondeling, G.T.; Cao, Q.; van der Pol, S.; Visser, S.; Postma, M.J.; Rozenbaum, M.H. The Impact of Patent Expiry on Drug Prices: Insights from the Dutch Market. J. Mark. Access Health Policy 2021, 9, 1849984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohara, A.; Yamabhai, I.; Chaisiri, K.; Tantivess, S.; Teerawattananon, Y. Impact of the Introduction of Government Use Licenses on the Drug Expenditure on Seven Medicines in Thailand. Value Health 2012, 15, S95–S99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ortiz-Prado, E.; Cevallos-Sierra, G.; Teran, E.; Vasconez, E.; Borrero-Maldonado, D.; Ponce Zea, J.; Simbaña-Rivera, K.; Gómez-Barreno, L. Drug Prices and Trends before and after Requesting Compulsory Licenses: The Ecuadorian Experience. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2019, 29, 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MedsPaL. Available online: https://www.medspal.org/?page=1 (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- Sun, J.; Cheng, H.; Hassan, M.R.A.; Chan, H.-K.; Piedagnel, J.-M. What China Can Learn from Malaysia to Achieve the Goal of “Eliminate Hepatitis C as a Public Health Threat” by 2030—A Narrative Review. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2021, 16, 100261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, M.; Kimmitt, R.; Moon, S. Non-Commercial Pharmaceutical R&D: What Do Neglected Diseases Suggest about Costs and Efficiency? F1000Research 2021, 10, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, J.; Hill, A. Is Pricing of Dolutegravir Equitable? A Comparative Analysis of Price and Country Income Level in 52 Countries. J. Virus Erad. 2018, 4, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.; Hoen, E. Medicines for the World. The Scientist Magazine®. 1 October 2012. Available online: https://www.the-scientist.com/critic-at-large/medicines-for-the-world-40426 (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- World Health Organization. Selection of Essential Medicines at Country Level: Using the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines to Update a National Essential Medicines List; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Clinton, C.; Sridhar, D. Who Pays for Cooperation in Global Health? A Comparative Analysis of WHO, the World Bank, the Global Fund to Fight HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. Lancet 2017, 390, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stevens, H.; Huys, I. Innovative Approaches to Increase Access to Medicines in Developing Countries. Front. Med. 2017, 4, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Access to Medicine Index Less than Half of Key Products Are Covered by Pharma Companies’ Access Strategies in Poorer Countries. Available online: https://accesstomedicinefoundation.org/access-to-medicine-index/results/less-than-half-of-key-products-are-covered-by-pharma-companies-access-strategies-in-poorer-countries (accessed on 26 November 2021).

- Access to Medicine Index Do Pharma Companies Plan Ahead to Ensure Their Products Are Accessible to Patients in Low- and Middle-Income Countries? Available online: https://accesstomedicinefoundation.org/access-to-medicine-index/results/do-pharma-companies-plan-ahead-to-ensure-their-products-are-accessible-to-patients-in-low-and-middle-income-countries (accessed on 26 November 2021).

- Bermudez, J.; Hoen, E. The UNITAID Patent Pool Initiative: Bringing Patents Together for the Common Good. Open AIDS J. 2010, 4, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Martinelli, A.; Mina, A.; Romito, E. Collective Licensing and Asymmetric Information: The Double Effect of the Medicine Patent Pool on Generic Drug Markets. Scuola Superiore SantíAnna Working Paper. 2020, pp. 1–45. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3949438 (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Medicines Patent Pool. Exploring the Expansion of the Medicines Patent Pool’s Mandate to Patented Essential Medicines: A Feasibility Study of the Public Health Needs and Potential Impact; Medicines Patent Pool: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Wang, L.X. Global Drug Diffusion and Innovation with a Patent Pool: The Case of HIV Drug Cocktails. SSRN Electron. J. 2019, 1–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galasso, A.; Schankerman, M. Patents and Cumulative Innovation: Causal Evidence from the Courts. Q. J. Econ. 2015, 130, 317–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.R.A.; Chan, H.K. Comment on: “Projections of the Healthcare Costs and Disease Burden Due to Hepatitis C Infection Under Different Treatment Policies in Malaysia, 2018–2040”. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 2020, 18, 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, K.B.; Kim, C.Y.; Lee, T.J. Understanding of for Whom, under What Conditions and How the Compulsory Licensing of Pharmaceuticals Works in Brazil and Thailand: A Realist Synthesis. Glob. Public Health 2019, 14, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zimmeren, E.; Vanneste, S.; Matthijs, G.; Vanhaverbeke, W.; van Overwalle, G. Patent Pools and Clearinghouses in the Life Sciences. Trends Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- What LDC Graduation Will Mean for Bangladesh’s Drugs Industry LDC Portal. Available online: https://www.un.org/ldcportal/what-ldc-graduation-will-mean-for-bangladeshs-drugs-industry/ (accessed on 26 November 2021).

- TRIPS Database—Medicines, Law & Policy. Available online: http://tripsflexibilities.medicineslawandpolicy.org/ (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- Patent Application for AIDS Drug Opposed for First Time in India MSF. Available online: https://www.msf.org/patent-application-aids-drug-opposed-first-time-india (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Patent Opposition Database. Available online: https://www.patentoppositions.org/ (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- Löfgren, H. The Politics of the Pharmaceutical Industry and Access to Medicines: World Pharmacy and India; Routledge: Abingdon on Thames, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Europe Cannot “Treaty” Its Way Out of the Pandemic—Health Policy Watch. Available online: https://healthpolicy-watch.news/europe-treaty-pandemic/ (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Maxmen, A. The Fight to Manufacture COVID Vaccines in Lower-Income Countries. Nature 2021, 597, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juneja, S.; Gupta, A.; Moon, S.; Resch, S. Projected Savings through Public Health Voluntary Licences of HIV Drugs Negotiated by the Medicines Patent Pool (MPP). PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Third World Network (WTN). Medicines Patent Pool License Strengthens Merck’s Market Control and Undermines the Pool’s Core Principles—TWN Info Service on Health Issues (Nov21/01). Available online: https://www.twn.my/title2/health.info/2021/hi211101.htm (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, R. Writing Narrative Style Literature Reviews. Med. Writ. 2015, 24, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Fidler, F.M.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Brennan, S.E.; Haddaway, N.R.; Hamilton, D.G.; Kanukula, R.; Karunananthan, S.; Maxwell, L.J.; et al. The REPRISE Project: Protocol for an Evaluation of REProducibility and Replicability In Syntheses of Evidence. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Galasso, A.; Schankerman, M. Licensing Life-Saving Drugs for Developing Countries: Evidence from the Medicines Patent Pool. National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Paper No. 28545. 2020, pp. 1–49. Available online: https://www.nber.org/papers/w28545 (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Simmons, B.; Cooke, G.S.; Miraldo, M. Effect of Voluntary Licences for Hepatitis C Medicines on Access to Treatment: A Difference-in-Differences Analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2019, 7, E1189–E1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morin, S.; Moak, H.B.; Bubb-Humfryes, O.; von Drehle, C.; Lazarus, J.V.; Burrone, E. The Economic and Public Health Impact of Intellectual Property Licensing of Medicines for Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries: A Modelling Study. Lancet Public Health 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assefa, Y.; Hill, P.S.; Ulikpan, A.; Williams, O.D. Access to Medicines and Hepatitis C in Africa: Can Tiered Pricing and Voluntary Licencing Assure Universal Access, Health Equity and Fairness? Glob. Health 2017, 13, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröeder, S.E.; Pedrana, A.; Scott, N.; Wilson, D.; Kuschel, C.; Aufegger, L.; Atun, R.; Baptista-Leite, R.; Butsashvili, M.; El-Sayed, M.; et al. Innovative Strategies for the Elimination of Viral Hepatitis at a National Level: A Country Case Series. Liver Int. 2019, 39, 1818–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sampat, B. A Survey of Empirical Evidence on Patents and Innovation. National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Paper No. 25383. 2018, pp. 1–42. Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w25383 (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Sampat, B.; Williams, H.L. How Do Patents Affect Follow-on Innovation? Evidence from the Human Genome. Am. Econ. Rev. 2019, 109, 203–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Motari, M.; Nikiema, J.B.; Kasilo, O.M.J.; Kniazkov, S.; Loua, A.; Sougou, A.; Tumusiime, P. The Role of Intellectual Property Rights on Access to Medicines in the WHO African Region: 25 Years after the TRIPS Agreement. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, C. Navigating the Patent Thicket: Cross Licenses, Patent Pools, and Standard Setting. Innov. Policy Econ. 2000, 1, 119–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trachtenberg, D.; Kaplan, W.A.; Wirtz, V.J.; Gallagher, K.P. The Effects of Trade Agreements on Imports of Biologics: Evidence from Chile. J. Glob. Dev. 2019, 10, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Medeiros Rocha, M.; de Andrade, E.P.; Alves, E.R.; Cândido, J.C.; de Miranda Borio, M. Access to Innovative Medicines by Pharma Companies: Sustainable Initiatives for Global Health or Useful Advertisement? Glob. Public Health 2020, 15, 777–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, S. Bio-Patent Pooling and Policy on Health Innovation for Access to Medicines and Health Technologies That Treat HIV/AIDS: A Need for Meeting of [Open] Minds. In Global Governance of Intellectual Property in the 21st Century: Reflecting Policy Through Change; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Third World Network (WTN). Third World Network COVID-19: WTO & WHO Hold Meet with Big Pharma on Access to Vaccine. TWN Info Service on Health Issues (Jul21/06). Available online: https://www.twn.my/title2/health.info/2021/hi210706.htm (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Médecins Sans Frontières. Voluntary Licenses and Access to Medicines: Recommendations to Governments to Safeguard Access to Medicines in Pharmaceutical Voluntary License Agreements; Médecins Sans Frontières: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gotham, D.; Meldrum, J.; Nageshwaran, V.; Counts, C.; Kumari, N.; Martin, M.; Beattie, B.; Post, N. Global Health Equity in United Kingdom University Research: A Landscape of Current Policies and Practices. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2016, 14, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wagstaff, A.; Eozenou, P.H.-V. CATA Meets IMPOV: A Unified Approach to Measuring Financial Protection in Health. World Bank Washington DC Working Paper Series 6861. 2014, pp. 1–41. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/18353 (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Gaviria, M.; Kilic, B. A Network Analysis of COVID-19 MRNA Vaccine Patents. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 546–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampat, B.N.; Shadlen, K.C. The COVID-19 Innovation System. Health Aff. 2021, 40, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Medicines for COVID-19. Available online: https://publicmeds4covid.org/ (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- Coronavirus (COVID-19) Vaccinations—Statistics and Research—Our World in Data. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- Labonté, R.; Johri, M.; Plamondon, K.; Murthy, S. Canada, Global Vaccine Supply, and the TRIPS Waiver. Can. J. Public Health 2021, 112, 543–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfizer and Medicines Patent Pool Reach “Ground-Breaking” Voluntary Licensing Deal for New COVID-19 Treatment Pill—Health Policy Watch. Available online: https://healthpolicy-watch.news/pfizer-and-medicines-patent-pool/ (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- Merck COVID-19 Pill Sparks Calls for Access for Lower Income Countries Reuters. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/merck-covid-19-pill-sparks-calls-access-lower-income-countries-2021-10-17/ (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- Legge, D.G.; Kim, S. Equitable Access to COVID-19 Vaccines: Cooperation around Research and Production Capacity Is Critical. J. Peace Nucl. Disarm. 2021, 4, 73–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Technology Transfer Hub—MPP. Available online: https://medicinespatentpool.org/covid-19/technology-transfer-hub (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Erren, T.C.; Lewis, P.; Shaw, D.M. The COVID-19 Pandemic: Ethical and Scientific Imperatives for “Natural” Experiments. Circulation 2020, 142, 309–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COVID-19 Vaccine Manufacturing Knowledge Portal. Available online: https://www.knowledgeportalia.org/covid19-vaccine-manufacturing (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- COVID-19 Vaccine Manufacturing Capacity—Knowledge Ecology International. Available online: https://www.keionline.org/covid-19-vaccine-manufacturing-capacity (accessed on 27 November 2021).

- Vu, M.; Yu, J.; Awolude, O.A.; Chuang, L. Cervical Cancer Worldwide. Curr. Probl. Cancer 2018, 42, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bambra, C.; Riordan, R.; Ford, J.; Matthews, F. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Health Inequalities. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2020, 74, 964–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Founding Principles Global Health Innovative Technology Fund. Available online: https://www.ghitfund.org/overview/principles/en (accessed on 30 November 2021).

| Mechanism | Description | Example | Publicly Available Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| LDCs waiver | LCDs are exempted from key TRIPS provisions related to medical technologies, which may allow them to purchase or produce generics even for patented drugs | Bangladesh’s large pharmaceutical industry accounts for around 1% of gross domestic product and supplies almost the entire domestic market and export to >100 countries. Around a fifth of generic drugs produced in the country under the TRIPS waiver are patented in other countries [41]. There is a concern that when Bangladesh will leave the UN LDC category in 2024, and no longer be eligible for the waiver, it will hinder the country’s technological development and a substantial rise in health costs [41]. | TRIPS Flexibilities Database (Medicines Law & Policy) [42] |

| Compulsory licenses (CLs) and government use of patents | Under TRIPS, a country is authorized to license IP rights for a patented medical product for domestic production without the patent holder permission to increase access to a particular drug | Malaysia, an upper-middle-income country, was excluded from VLs of costly patented DAAs despite a high burden of HCV infection (prevalence of 2.5% among the adult population in 2009). Patented sofosbuvir, a core of DAAs, was sold in Malaysia at about US$11,000, while its production was estimated to be below US$136 [24]. In 2017, the government issued a compulsory license, which was also followed by the country’s inclusion in bilateral VLs. In about two years, generic versions of sofosbuvir under the compulsory license brought down the public procurement price to US$300 per 12-week treatment [24,38]. | TRIPS Flexibilities Database (Medicines Law & Policy) [42] |

| Patent opposition | National legal procedure where a third party may object to an application for registration of a trivial patent as part of an ever-greening strategy | Successful patent oppositions are common in countries with strong national legislative mechanisms for the use of TRIPS flexibilities, such as India and Brazil. A patient-led group led to the rejection of GlaxoSmithKline’s patent application in India in 2006 on the HIV fixed-dose-combination zidovudine/lamivudine, on the grounds that it was not an ‘inventing step’, but rather a combination of two existing drugs widely used in practice [43]. | Patent Opposition Database (Médecins Sans Frontières) [44] |

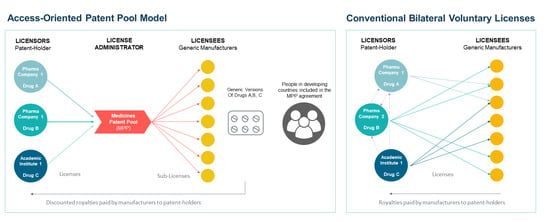

| Voluntary licenses (VLs) | Bilateral, non-exclusive contractual agreements between patent-holding firms (licensors) and each generic manufacturer (licensees) which allow the supply of lower-cost generic medicines to certain LMICs in exchange for a royalty fee | In 2014–2015, Gilead Sciences licensed patents for its DAAs compounds used to treat HCV (sofosbuvir, ledipasvir, and a newer compound, velpatasvir) through bilateral agreements with 11 generic manufacturers for use in 101 countries, predominantly LMICs [1]. | MedsPal (MPP) [23] |

| Voluntary licensing through a patent pool | The UN-backed Medicines Patent Pool (administrator) negotiates licenses for high-value EMs with patent-holding firms (licensors) to allow their production by generic manufacturers (sublicenses) in exchange for a reduced royalty fee | In 2015, the MPP signed an agreement with Bristol-Myers Squibb that allows the supply of generic versions of DAA compound daclatasvir in 112 LMICs [1]. | MedsPal (MPP) [23] |

| Patents non-assertion declaration | In humanitarian situations and in response to access campaigns, patent holder companies may commit not to enforce patent lefts in a defined group of countries and under specific conditions, allowing a generic version to be produced | In 2009, Boehringer Ingelheim granted non-assert declarations to all generic manufacturers prequalified by the WHO in Africa and India to produce HIV/AIDS drugs containing the active ingredient nevirapine. The declaration covered 78 countries, including all African countries, low-income countries, and LDCs [45]. | MedsPal (MPP) [23] |

| Reference | Objective | Methodology | Data Sources | Population | Period | Medicines | Main Outcomes | Controls |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simmons, Cooke, & Miraldo, 2019 [55] [Peer reviewed] | To estimate the effect of the introduction of bilateral and MPP voluntary licenses for HCV drugs on access to treatment | Difference-in-difference analysis Treatment group: countries included in the licensing for HCV treatment from either Gilead (VL) or Bristol-Myers Squibb (through the MPP) Comparison group: countries not included | Polaris Observatory—HCV epidemiology and treatment volumes, Gilead and MPP voluntary licensing agreements data | MPP-licensed LMICs (n = 19): 127.2 M people, average GDP per capita $8.5 K, average 9% prevalence of HCV among adult populations. Non-licensed LMICs (n = 16): 132.6 M people, average GDP per capita $17.3 K, average 0.9% prevalence of HCV. | 2004–2016 | HCV DAAs | Annual HCV treatment uptake per 1000 individuals diagnosed with HCV | Country-level fixed effects; Time-variant economic effects, health expenditure, and health system indicators; Region-specific year effects to control for unobserved time-variant factors |

| Wang, 2019 [36] [Preprint] | To evaluate the impact of the MPP on static and dynamic welfare: how the MPP affects generic shares in LMICs, the changes in R&D associated with the pool, and the welfare gains compared to the pool’s operating costs | Mixed-methods, including difference-in-difference analysis and cost-benefit analysis | The global fund price and quality reporting, FDA and AIDSinfo.gov | 103 LMICs | 2007–2017 | HIV medicines | Total quantities and generic shares Changes in R&D (new trials and approval of new drugs associated with the pool) Welfare gains compared to the pool’s operating costs. | GDP per capita, Worldwide Governance indicators, HIV prevalence and age-adjusted death rates |

| Martinelli, Mina & Romito, 2020 [34] [Working paper] | To exploit heterogeneity in the timing of entry into the MPP across countries to estimate the effect of the pool on the market for EMs | Difference-in-difference analysis | The GPRM (Global Price Reporting Mechanism), the MPP website, and the MedsPaL (Medicines Patents and Licenses database) | The final sample included 3862 observations and 616 pairs of country/active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) included in the pool. Countries where a generic version of the MPP-API was already available and commercialized before they joined the pool. | 2005–2017 | HIV medicines | The annual total quantity and share of generic versions of pills of a specific API bought yearly by procurement agencies and delivered in a specific country | Fixed-country effects and a variable controls for the possibility that shifts are driven by changes in the agencies’ budgets, Ginarte Park index (a proxy for level of nations’ patent protection) |

| Galasso & Schankerman, 2021 [54] [Working paper] | To study how the Medicines Patent Pool affects the licensing, launch and sales of drugs in LMICs | Difference-in-difference analysis Treatment group: drug-country pairs from the MPP Comparison group: drug-country pairs—medicines that the MPP aimed to license when the pool was formed in 2010, for which bargaining with the pool started but failed. | IQVIA data on international drug products sales, MPP licensing data (including information on non-MPP products and non-MPP bilateral VLs between the upstream patentee and generic firms) | 129 LMICs countries for which patent protection was in place for at least one of the sample drugs. Data on sales are only available for a subset of 32 countries, mostly middle-income countries outside Sub-Saharan Africa. | 2005–2018 | 173 EMs for HIV, TB and HCV | Number of downstream licensing deals, launch, quantity sold and price of EMs in LMICs. | Time-varying demographic features of the sample countries (World Bank Data) Prevalence of HIV in each country per-capita health expenditure |

| Juneja, Gupta, Moon, & Resch, 2017 [48] [Peer-reviewed] | To estimate the savings generated by licenses negotiated by the MPP for ARVs to treat HIV/AIDS for the period 2010–2028 (the year by which patents on all of these drugs will have expired) | Cost savings attributed to the MPP were calculated by subtracting the expected price of ARVs medicines following inclusion in MPP licenses from a counterfactual situation in which the MPP does not exist. A cost-benefit ratio was calculated based on the pool’s actual and projected costs. | MPP Medspal, UNAIDS reports on patients accessing HIV/AIDS therapies, and tiered prices data by Médecins Sans Frontières | MPP impact is attributed only to countries where the MPP license had unblocked existing patent, and the country was not eligible for supply by generic producers included in any existing or planned bilateral VL | 2010–2028 | All 13 HIV medicines included in the pool by 2016 | Projected cost savings associated with 13 MPP licenses A cost-benefit ratio | N/A |

| Morin et al., 2021 [56] [Peer reviewed] | To study the economic and health effect of voluntary licensing for medicines for HIV and HCV in LMICs | MPP impact assessment modeling study to examine the difference between factual and counterfactual scenarios, with and without an MPP license for two case study medicines | MPP licensees, the Polaris Observatory (market share forecasts), matched with epidemiological information from UNAIDS | All LMICs | 2012–2020; 2020–2032 | Dolutegr-avir (for HIV) and daclatasv-ir (for HCV) | Cost savings—drugs costs and health system costs associated with untreated disease progression. Health impact—uptake, mortality, morbidity, and adverse effects linked to HIV or HCS disease progression or the medicines used. | N/A |

| Beall & Attaran, 2017 [6] [Peer reviewed] | To assess to what extent LMICs that have granted patent protection on essential ARVs procure generic equivalents of those medicines, and identify which legal flexibilities (CLs, LCD waivers, VLs, and non-assert declarations) may have been most relevant for facilitating this access. | Data linkage and cross-sectional descriptive statistical analysis. The researchers cross-referenced the datasets with lists of legal flexibilities which facilitate generic access where patents have been granted. | Patent databases (USA, Canada, and international) WHO’s Global Price Reporting Mechanism ARVs procurement data in LMICs, and various institutional and academic sources tracking the use of legal IP flexibilities | 85 LMICs, a total of 1924 generic procurement transactions (1.34 billion units) for a sample of ARVs | 2013–2014 | 13 patented ARVs that were sold by a single, originator supplier in the US or Canada and are likely to be patent-protected in LMICs | Median patent coverage Alignment of generic procurement with patent protection in the exporting and/or importing country. Volume of generics purchased attributed to different legal flexibilities | N/A |

| Assefa et al., 2017 [57] [Peer-reviewed] | To test the hypothesis that Gilead’s bilateral VLs and tiered pricing strategies for DAAs in seven African countries will fail to achieve the SDG 2030 goal of HCV elimination and are insufficient for achieving fair and equitable access to DAAs in those countries. | A cross-sectional analysis of countries’ financial capacity to provide DAAs for HCV treatment under present VLs and tiered-pricing arrangements. Conservative estimates were used—prices for 12-weeks regimens, lowest and factory gate prices, assumed zero re-infection. | The prices used for modelling were taken from a 2016 WHO report | A convenience sample of 7 African countries with experiencing a different range of HCV disease burden and eligible for generic supply under Gilead’s VL: Egypt, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Democratic Republic of Congo, Cameroon, Rwanda and South Africa. | 2016 | HCV DAA’s (sofosbuvir and sofosbuvir/ledipasvir) | Financial capacity of each country to provide universal access to selected DAAs under present VLs and tiered-pricing arrangements with Gilead | N/A |

| Design | Reference | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Quasi-Experimental Studies | Simmons, Cooke, & Miraldo, 2019 [55] |

|

| Wang, 2019 [36] |

| |

| Martinelli, Mina & Romito, 2020 [34] |

| |

| Galasso & Schankerman, 2021 [54] |

| |

| Impact Assessment Models | Juneja, Gupta, Moon, & Resch, 2017 [48] |

|

| Morin et al., 2021 [56] |

| |

| Descriptive Study | Beall & Attaran, 2017 [6] |

|

| Capacity to Pay Analysis | Assefa et al., 2017 [57] |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mermelstein, S.; Stevens, H. TRIPS to Where? A Narrative Review of the Empirical Literature on Intellectual Property Licensing Models to Promote Global Diffusion of Essential Medicines. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics14010048

Mermelstein S, Stevens H. TRIPS to Where? A Narrative Review of the Empirical Literature on Intellectual Property Licensing Models to Promote Global Diffusion of Essential Medicines. Pharmaceutics. 2022; 14(1):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics14010048

Chicago/Turabian StyleMermelstein, Shiri, and Hilde Stevens. 2022. "TRIPS to Where? A Narrative Review of the Empirical Literature on Intellectual Property Licensing Models to Promote Global Diffusion of Essential Medicines" Pharmaceutics 14, no. 1: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics14010048

APA StyleMermelstein, S., & Stevens, H. (2022). TRIPS to Where? A Narrative Review of the Empirical Literature on Intellectual Property Licensing Models to Promote Global Diffusion of Essential Medicines. Pharmaceutics, 14(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics14010048