Abstract

Background

Immunotherapy improves overall survival for patients with metatstatic melanoma and improves recurrence–free survival in the adjuvant setting, but is costly and has adverse effects. Little is known about the preferences of patients and clinicians regarding immunotherapy. This study aimed to identify factors important to patients and clinicians when deciding about immunotherapy for stages 2–4 melanoma.

Methods

This study searched the Medline, EMBASE, ECONLIT, PsychINFO, and COCHRANE Systematic Reviews databases from inception to June 2018 for immunotherapy choice and preference studies. Findings were tabulated and summarized, and study reporting was assessed against recommended checklists.

Results

This investigation identified eight studies assessing preferences for melanoma treatment; four studies regarding nivolumab, pembrolizumab, or ipilimumab; and four studies regarding interferon conducted in the United States, Germany, and Australia. The following 10 factors were important to decision-making: overall survival, recurrence-free survival, treatment side effects, dosing regimen, patient or payer cost, patient age, clinician or family/friend treatment recommendation, quality of life, and psychosocial effects. Overall survival was the most important factor for all respondents. The patients judged severe toxicities to be tolerable for small survival gains. The description of information about treatment harms and benefits was limited in most studies.

Conclusions

Overall survival was of primary importance to patients and clinicians considering immunotherapy. Impaired quality of life due to adverse effects appeared to be a second-order consideration. Future research is required to determine preferences for contemporary combination therapies, extended treatment durations, and avoidance of chronic side effects.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO registration number CRD42018095899.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Global Burden of Disease Cancer Collaboration, Fitzmaurice C, Allen C et al. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life years for 32 cancer groups, 1990 to 2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease study. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:524–48.

Gershenwald JE, Hess KR, Sondak VK, et al. (2017) Melanoma staging. CA Cancer J Clin. 67:472–92.

Eggermont AM, Chiarion-Sileni V, Grob JJ, et al. Adjuvant ipilimumab versus placebo after complete resection of high-risk stage III melanoma (EORTC 18071): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:522–30.

Eggermont AMM, Blank CU, Mandala M, et al. Adjuvant pembrolizumab versus placebo in resected stage III melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1789–801.

Weber J, Mandala M, Del Vecchio M, et al. Adjuvant nivolumab versus ipilimumab in resected stage III or IV melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1824–35.

US National Library of Medicine (2019). Safety and Efficacy of Pembrolizumab Compared to Placebo in Resected High-Risk Stage II Melanoma (MK-3475-716/KEYNOTE-716). Retrieved 29 April 2019 at https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03553836.

IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science (2018). Global Oncology Trends 2018, Innovation, Expansion and Disruption. Retrieved 18 May 2019 at https://www.iqvia.com/-/media/iqvia/pdfs/institute-reports/global-oncology-trends-2018.pdf?_=1558151400938.

Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: a pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient’s experience. Oncologist. 2013;18:381–90.

Cancer Council Australia Melanoma Guidelines Working Party. Sydney: Cancer Council Australia (2008). Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of melanoma. Retrieved 29 April 2019 at https://wiki.cancer.org.au/australiawiki/index.php?oldid=201397.

National Collaborating Centre for Cancer (UK) (2015). Melanoma: Assessment and Management. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (NICE guideline no. 14.) Retrieved 29 April 2019 at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK315807/.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535.

Bridges JF, Hauber AB, Marshall D, et al. Conjoint analysis applications in health–a checklist: a report of the ISPOR Good Research Practices for Conjoint Analysis Task Force. Value Health. 2011;14:403–13.

Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e297.

Higgins JPT, Green S (eds). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Retrieved 29 April 2019 at https://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/.

Ryan M, Gerard, K, Amaya-Amaya, M. Using Discrete Choice Experiments to Value Health and Health Care. Springer, New York, 2008.

Gafni A. The standard gamble method: what is being measured and how it is interpreted. Health Services Res. 1994;29:207–24.

Beusterien K, Middleton MR, Wang PF, et al. Patient and physician preferences for treating adjuvant melanoma: a discrete choice experiment. J Cancer Ther. 2017;08:37–50.

Bramlette TB, Lawson DH, Washington CV, et al. Interferon alfa-2b or not 2b? Significant differences exist in the decision-making process between melanoma patients who accept or decline high-dose adjuvant interferon alfa-2b treatment. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:11–6.

Kaehler KC, Blome C, Forschner A, et al. Preferences of German melanoma patients for interferon (IFN) alpha-2b toxicities (the DeCOG “GERMELATOX survey”) versus melanoma recurrence to quantify patients’ relative values for adjuvant therapy. Medicine. 2016;95:e5375.

Kahler KC, Blome C, Forschner A, et al. The outweigh of toxicity versus risk of recurrence for adjuvant interferon therapy: a survey in German melanoma patients and their treating physicians. Oncotarget. 2018;9:26217–25.

Kilbridge KL, Weeks JC, Sober AJ, et al. Patient preferences for adjuvant interferon alfa-2b treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:812–23.

Huynh E, Rose J, Lambides M, et al. Preferences for advanced melanoma immuno-oncology treatments. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2018;31:149.

Krammer R, Heinzerling L. Therapy preferences in melanoma treatment: willingness to pay and preference of quality versus length of life of patients, physicians and healthy controls. PLoS One. 2014;9:e111237.

Stenehjem DD, Au TH, Ngorsurachese S, et al. Immunotargeted therapy in melanoma: patient, provider preferences, and willingness to pay at an academic cancer center. Melanoma Res. https://doi.org/10.1097/cmr.0000000000000572.

Mansfield C, Ndife B, Chen J, et al. Patient preferences for treatment of metastatic melanoma. Future Oncol. 2019;15:1255–68.

Gutkin PM, Hiniker SM, Swetter SM, et al. Complete response of metastatic melanoma to local radiation and immunotherapy: 6.5 year follow-up. Cureus. 2018;10:e372. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.3723.

Acknowledgement

Ann Livingstone is supported by an Australian NHMRC postgraduate scholarship (APP1168194), a Sydney Catalyst Postgraduate Research Supplementary Scholarship, and a Melanoma Institute Australia postgraduate research scholarship (top up award). Anupriya Agarwal is supported by a NHMRC Clinical Trials Centre non-award postgraduate scholarship. Alexander M. Menzies is supported by a Cancer Institute New South Wales Fellowship. Rachael L. Morton is supported by an Australian NHMRC Translating Research Into Practice (TRIP) Fellowship (APP1150989) and a University of Sydney Robinson Fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosure

Martin R. Stockler has served on advisory boards for Amgen, Astra Zeneca, BMS, MSD, Pfizer, and Roche. Alexander M. Menzies has served on advisory boards for BMS, MSD, Novartis, Roche, and Pierre-Fabre. Ann Livingstone, Anupriya Agarwal, Kirsten Howard, and Rachael L. Morton have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: MEDLINE search strategy with MeSH terms and text words

1 | exp MELANOMA/ |

2 | melano*.tw,kf. |

3 | (skin* adj4 cancer*).tw,kf. |

4 | 1 or 2 or 3 |

5 | adadjuvant*.tw,kf. |

6 | immunotherapy/ or radioimmunotherapy/ |

7 | (immunotherap* or radioimmunotherap*).tw,kf. |

8 | (adjuvan* adj4 immunotherap*).mp. |

9 | 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 |

10 | Patient preference/ |

11 | Decision-making/ or choice behavior/ |

12 | exp “Patient acceptance of health care”/ |

13 | ((patient* or doctor* or clinician*) adj4 (preference* or accept* or participat*)).tw,kf. |

14 | ((decision* or choice* or choose*) adj4 (treat* or therap* or mak* or behavio?r*)).tw,kf. |

15 | (“discrete choice*” or dce or “stated preference*” or “conjoint analys*” or “choice experiment*” or “discrete rank*” or “best worst” or “best best”).tw,kf. |

16 | 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 |

17 | 4 and 9 and 16 |

Appendix 2: ISPOR Statement: a checklist for conjoint analysis applications in health care

1 Was a well-defined research question stated and is a conjoint analysis an appropriate method for answering it? |

1.1 Were a well-defined research question and a testable hypothesis articulated? |

1.2 Was the study perspective described, and was the study placed in a particular decision-making or policy context? |

1.3 What is the rationale for using conjoint analysis to answer the research question? |

2 Was the choice of attributes and levels supported by evidence? |

2.1 Was attribute identification supported by evidence (literature reviews, focus groups, or other scientific methods)? |

2.2 Was attribute selection justified and consistent with theory? |

2.3 Was level selection for each attribute justified by the evidence and consistent with the study perspective and hypothesis? |

3 Was the construction of tasks appropriate? |

3.1Was the number of attributes in each conjoint task justified (i.e., full or partial profile)? |

3.2 Was the number of profiles in each conjoint task justified? |

3.3 Was (should) an opt out or status-quo alternative (be) included? |

4 Was the choice of experimental design justified and evaluated? |

4.1 Was the choice of experimental design justified? Were alternative experimental designs considered? |

4.2 Were the properties of the experimental design evaluated? |

4.3 Was the number of conjoint tasks included in the data-collection instrument appropriate? |

5 Were preferences elicited appropriately given the research question? |

5.1 Was there sufficient motivation and explanation of conjoint tasks? |

5.2 Was an appropriate elicitation format (i.e., rating, ranking, or choice) used? Did (should) the elicitation format allow for indifference? |

5.3 In addition to preference elicitation, did the conjoint tasks include other qualifying questions (e.g., strength of preference, confidence in response, and other methods)? |

6 Was the data-collection instrument designed appropriately? |

6.1 Was appropriate respondent information collected (e.g., sociodemographic, attitudinal, health history or status, and treatment experience)? |

6.2 Were the attributes and levels defined, and was any contextual information provided? |

6.3 Was the level of burden of the data-collection instrument appropriate? Were respondents encouraged and motivated? |

7 Was the data-collection plan appropriate? |

7.1 Was the sampling strategy justified (e.g., sample size, stratification, and recruitment)? |

7.2 Was the mode of administration justified and appropriate (e.g., face-to-face, pen-and-paper, web-based)? |

7.3 Were ethical considerations addressed (e.g., recruitment, information, and/or consent, compensation)? |

8 Were statistical analyses and model estimations appropriate? |

8.1 Were respondent characteristics examined and tested? |

8.2 Was the quality of the responses examined (e.g., rationality, validity, reliability)? |

8.3 Was model estimation conducted appropriately? Were issues of clustering and subgroups handled appropriately? |

9. Were the results and conclusions valid? |

9.1 Did study results reflect testable hypotheses and account for statistical uncertainty? |

9.2 Were study conclusions supported by the evidence and compared with existing findings in the literature? |

9.3 Were study limitations and generalizability adequately discussed? |

10. Was the study presentation clear, concise, and complete? |

10.1 Was study importance and research context adequately motivated? |

10.2 Were the study data-collection instrument and methods described? |

10.3 Were the study implications clearly stated and understandable to a wide audience? |

Appendix 3: STROBE statement: a checklist of items that should be included in reports of cross-sectional studies

Item no. | Recommendation | |

|---|---|---|

Title and abstract | 1 | (a) Indicate the study’s design with a commonly used term in the title or the abstract |

(b) Provide in the abstract an informative and balanced summary of what was done and what was found | ||

Introduction | ||

Background/rationale | 2 | Explain the scientific background and rationale for the investigation being reported |

Objectives | 3 | State specific objectives, including any pre-specified hypotheses |

Methods | ||

Study design | 4 | Present key elements of study design early in the paper |

Setting | 5 | Describe the setting, locations, and relevant dates, including periods of recruitment, exposure, follow-up, and data collection |

Participants | 6 | (a) Give the eligibility criteria, and the sources and methods of selection of participants |

Variables | 7 | Clearly define all outcomes, exposures, predictors, potential confounders, and effect modifiers. Give diagnostic criteria, if applicable |

Data sources/measurement | 8a | For each variable of interest, give sources of data and details of methods of assessment (measurement). Describe comparability of assessment methods if there is more than one group |

Bias | 9 | Describe any efforts to address potential sources of bias |

Study size | 10 | Explain how the study size was determined |

Quantitative variables | 11 | Explain how quantitative variables were handled in the analyses. If applicable, describe which groupings were chosen and why |

Statistical methods | 12 | (a) Describe all statistical methods, including those used to control for confounding |

(b) Describe any methods used to examine subgroups and interactions | ||

(c) Explain how missing data were addressed | ||

(d) If applicable, describe analytical methods taking account of sampling strategy | ||

(e) Describe any sensitivity analyses | ||

Results | ||

Participants | 13a | (a) Report numbers of individuals at each stage of study (e.g., numbers potentially eligible, examined for eligibility, confirmed eligible, included in the study, completing follow-up, and analyzed) |

(b) Give reasons for nonparticipation at each stage | ||

(c) Consider use of a flow diagram | ||

Descriptive data | 14a | (a) Give characteristics of study participants (e.g., demographic, clinical, social) and information on exposures and potential confounders |

(b) Indicate number of participants with missing data for each variable of interest | ||

Outcome data | 15a | Report numbers of outcome events or summary measures |

Main results | 16 | (a) Give unadjusted estimates and, if applicable, confounder-adjusted estimates and their precision (e.g., 95% CI). Make clear which confounders were adjusted for and why they were included |

(b) Report category boundaries when continuous variables were categorized | ||

(c) If relevant, consider translating estimates of relative risk into absolute risk for a meaningful time period | ||

Other analyses | 17 | Report other analyses done (e.g., analyses of subgroups and interactions, and sensitivity analyses) |

Discussion | ||

Key results | 18 | Summarize key results with reference to study objectives. |

Limitations | 19 | Discuss limitations of the study, taking into account sources of potential bias or imprecision. Discuss both direction and magnitude of any potential bias |

Interpretation | 20 | Give a cautious overall interpretation of results considering objectives, limitations, multiplicity of analyses, results from similar studies, and other relevant evidence |

Generalizability | 21 | Discuss the generalizability (external validity) of the study results |

Other information | ||

Funding | 22 | Give the source of funding and the role of the funders for the current study and, if applicable, for the original study on which the present article is based |

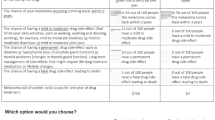

Appendix 4: Methodologic considerations of studies

Presentation of risk information | Choice survey designs | Analytical methods |

|---|---|---|

Opt-out alternative included (if unable to chose between treatments) 17,24 | ||

Pictorial aids plus % of risk 24 | Mixed logit models and hierarchical Bayesian model 22 | |

Visual bars showing number out of 100 experiencing side effects 22 | ||

Text plus risk (%) of side effects 17 | ||

Appendix 5: Quality assessment of included studies using ISPOR toola

Author | Well-defined research question | Choice of attributes/levels evidence based | Task construction appropriate | Choice of design justified and evaluated | Preferences elicited appropriate | Data collection design appropriate | Data collection plan appropriate | Statistical analysis and model estimations appropriate | Results and conclusions valid | Study presentation clear concise complete |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Beusterien et al. 17 | ✓ | ✓ | Partial | Partial | ✓ | Partial | Partial | Partial | Partial | ✓ |

Huynh et al. 22b | Partial | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Partial | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

Stenehjem et al. 24 | ✓ | ✓ | Partial | Partial | Partial | ✓ | ✓ | Partial | ✓ | ✓ |

Appendix 6: Quality assessment of included studies using STROBE toola

First author surname, initials, publication year | Title and abstract | Introduction | Methods | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Background | Objectives | Study design | Setting | Participants | Variables | Data sources | Bias | Study size | Quan variables | Stat methods | ||

Bramlette et al. 18 | Partial | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Partial | ✓ | X | ✓ | ✓ | Partial |

Kaehler et al. 19 | Partial | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Partial | Partial | Partial | ✓ | X | X | ✓ | Partial |

Kahler et al. 20 | Partial | ✓ | ✓ | Partial | Partial | Partial | ✓ | ✓ | X | X | ✓ | Partial |

Kilbridge et al. 21 | Partial | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Partial | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Krammer and Heinzerling 23 | Partial | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Partial | X | ✓ | ✓ | X | X | ✓ | Partial |

First author surname, initials, publication year | Title and abstract | Results | Discussion | Other info | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Participants | Descrip data | Outcome data | Main results | Other analyses | Key results | Limit | Interpret | General | Funding | ||

Bramlette et al. 18 | Partial | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Partial | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Kaehler et al. 19 | Partial | ✓ | Partial | ✓ | Partial | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Partial | ✓ |

Kahler et al. 20 | Partial | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Partial | X | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Kilbridge et al. 21 | Partial | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Partial | Partial | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X | ✓ |

Krammer and Heinzerling 23 | Partial | Partial | ✓ | ✓ | Partial | X | ✓ | Partial | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Livingstone, A., Agarwal, A., Stockler, M.R. et al. Preferences for Immunotherapy in Melanoma: A Systematic Review. Ann Surg Oncol 27, 571–584 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-019-07963-y

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-019-07963-y