Abstract

Background

Retinoic acid receptors (RARs) are ligand-regulated transcription factors controlling cellular proliferation and differentiation. Receptor-interacting proteins such as corepressors and coactivators play a crucial role in specifying the overall transcriptional activity of the receptor in response to ligand treatment. Little is known however on how receptor activity is controlled by intermediary factors which interact with RARs in a ligand-independent manner.

Results

We have identified the promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger protein (PLZF), a transcriptional corepressor, to be a RAR-interacting protein using the yeast two-hybrid assay. We confirmed this interaction by GST-pull down assays and show that the PLZF N-terminal zinc finger domain is necessary and sufficient for PLZF to bind RAR. The RAR ligand binding domain displayed the highest affinity for PLZF, but corepressor and coactivator binding interfaces did not contribute to PLZF recruitment. The interaction was ligand-independent and correlated to a decreased transcriptional activity of the RXR-RAR heterodimer upon overexpression of PLZF. A similar transcriptional interference could be observed with the estrogen receptor alpha and the glucocorticoid receptor. We further show that PLZF is likely to act by preventing RXR-RAR heterodimerization, both in-vitro and in intact cells.

Conclusion

Thus RAR and PLZF interact physically and functionally. Intriguingly, these two transcription factors play a determining role in hematopoiesis and regionalization of the hindbrain and may, upon chromosomal translocation, form fusion proteins. Our observations therefore define a novel mechanism by which RARs activity may be controlled.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

atRA receptors (RARs) α, β and γ and 9-cis retinoic acid receptors α, β and γ (RXRs) are encoded by three different genes and are members of the nuclear receptor superfamily. They function as ligand-inducible transcription factors in the form of RAR/RXR heterodimers. RAR is activated by atRA and binding of this ligand induces receptor conformational changes that switch on transcription of genes containing RA Response Elements (RAREs) by favoring coactivator tethering to regulated promoters. This protein complex assembly at regulated promoters induces chromatin remodeling and increased binding of RNA polymerase II to these promoters, thereby inducing a variety of biological effects (reviewed in [1, 2]). While a detailed understanding of the ligand-dependent activation of RARs has been achieved by structural and functional studies, little is known about factors regulating the activity of the unliganded receptor. We therefore undertook a 2-hybrid screen in yeast using an AF2-inactivated hRARα as a bait, thus unable to respond transcriptionally to ligand, to identify proteins potentially able to regulate RAR functions in a ligand-independent manner. Among the identified proteins, PLZF was found to physically interact with RARα through its zinc finger domain.

The human promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger (PLZF) protein is a 673 amino acid (AA) transcriptional repressor belonging to a large protein family characterized by a 120 AA N-terminal bric-à-brac, tramtrack, brad complex (BTB)/poxvirus zinc finger (POZ) domain. Proteins containing this BTB/POZ domain are associated to multiple functions such as development, embryogenesis and chromatin remodeling. The BTB/POZ domain allows protein homodimerization [3] and is involved in the recruitment of transcriptional corepressor complexes (NCoR) harboring histone deacetylases (HDAC) activity [4, 5]. In addition, this multimeric NCoR complex has been shown to provide a docking site for eight-twenty one (ETO), a non-DNA binding transcriptional repressor fused to the transcriptional activator AML1 in acute myelogenous leukemia [6, 7]. Another structural feature of PLZF is its C-terminal DNA binding domain made of nine C2H2 Kruppel-like zinc fingers that binds the consensus sequence GTACAGTTSCAU [8]. The first two zinc fingers are dispensable for DNA binding [9, 10], although other domains of the protein seem to contribute to the DNA binding specificity by restricting the DNA binding repertoire of PLZF [8]. Finally, a proline-rich and an acidic domains are found in the central part of the molecule (see also Figure 1 for more details).

Structure and properties of the bait RAR mutant and of one of the identified preys, PLZF. A) Schematic representation of the nuclear receptor RARα and structural localization of the two mutations K262A and K244A. These mutations weaken the interaction with the corepressor SMRT and abolish the interaction with the coactivator SRC-1, as visualized by GST pull-down assays (insert). B) Structure of the transcription factor PLZF identified by the two-hybrid screening of an ovary cDNA library with pLex12-RAR K244A-K262A used as a bait.

The exact biological role of PLZF remains to be established. However, its localization to nuclear bodies [11], which are nuclear structures associated to a central, transcriptional regulatory role [12], as well as its down regulation upon myeloid cell differentiation hint at a crucial role in cell growth control [13]. Indeed, genetic ablation of the PLZF gene in mice led to aberrant limb modeling resulting from deregulated cell proliferation and apoptosis, and also suggested that PLZF is, like all trans retinoic acid (atRA), a critical regulator of the linear expression of the Hox gene cluster [14]. Another strong argument for the biological importance of PLZF is the association of the chromosomal translocation t(11;17) to a rare variant of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL), which fuses the PLZF protein to retinoic acid receptor " (RARα, [15–17]). The PLZF-RARα fusion protein maintains most of the DNA and dimerization properties of both moieties, and PLZF-RAR binds to retinoic acid response elements (RAREs) as a heterodimeric partner of RXR, interfering with RARα functions by exerting a dominant negative effect [16, 18]. The resistance of t(11;17) APL to pharmacological doses of atRA contrasts with the sensitivity of the more common t(15;17) APL, which is characterized by a fusion between the promyelocytic leukemia transcription factor PML and the RARα proteins [19]. Thus the highly stable, targeted recruitment of NCoRs and HDACs to PLZF-RAR, mostly through the BTB/POZ domain, is likely to underlie the pathogenesis of the t(11;17) APL and renders it refractory to atRA chemotherapy, although additional factors are involved in the t(11;17)-induced leukemogenesis [20].

Interestingly, the PML protein acts either as a corepressor or a coactivator in a DNA-binding independent manner. PML gene inactivation leads to a strongly decreased transcriptional activation of the p21 gene and to impaired myeloid differentiation in response to retinoid stimulation [21]. Consistent with its role of coactivator, it has been shown to be integrated in the DRIP complex [22] and to interact with CBP [23].

Thus, quite intriguingly, PML and RAR have a functional relationship during transcriptional regulatory processes, and are chromosomal translocation partners. In this paper, we describe the physical interaction of PLZF with RARα and explore the functional consequences of this interaction on retinoid-regulated transcription.

Results and Discussion

PLZF interacts with RARα in-vitro

In a search for proteins that could interact with the unliganded, transcriptionally inactive RARα, we set up a yeast two hybrid screen using a mutated receptor (Figure 1A). Mutations were designed on the basis of the three-dimensional structure of the RARα ligand binding domain (LBD). It defines K262 as establishing salt bridges with E412 and E415 of the RARα activating function 2 (AF2) activating domain (AD) upon agonist binding [24, 25]. Mutation of K262 and of the neighboring K244 into alanine residues (RARα 2 K) prevents the ligand-induced folding of RARα AF2, impedes coactivator recruitment, weakens corepressor interaction (Figure 1A) and inactivates the transcriptional activity of RARα [26].

A human ovary cDNA library was screened for interaction with RARα 2 K and twelve positive clones were isolated and further characterized by DNA sequencing. A BLAST search indicated that we isolated, among these clones, a cDNA encoding amino acids 389 to 658 of human promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger protein (PLZF, Figure 1B), thus encompassing the first three N-terminal zinc fingers (ZF) of the PLZF DNA-binding domain. Although PLZF has been reported to interact specifically with LexA consensus binding sequences [10], the two N-terminal ZF are dispensable for this activity [9]. We therefore carried out in-vitro protein interaction assays (Figure 2) using the three PLZF Nt-ZF fused to glutathione-S-transferase (GST-PLZF 3ZF) to determine its ability to bind to full length RARα, RARα 2 K, or various deletion mutants of this receptor [AF1: RARα AF1 (AAs 1–88); LBD: RARα LBD (AAs 152–462); RARα)403 (AAs 1 to 403)]. As a control for specificity, we used RXRα, a nuclear receptor displaying strong sequence homologies with RAR in the DNA binding domain, but harboring significant sequence divergence in both the AF1 and AF2 regions. As expected, PLZF 3ZF interacted with RARα in a ligand-independent manner, as well as with the AF2-inactivated RARα 2 K mutant. Thus ligand-induced structural transitions do not affect PLZF/RARα interactions and are not conditioned by AF2-AD positioning, as confirmed by the interaction of RARα)403 with PLZF (Figure 2). The isolated RARα AF1 domain did not retain a strong affinity for PLZF 3ZF, however, a weak but reproducible interaction was detected with the LBD moiety of the receptor. RXRα did not bind to PLZF 3ZF, suggesting that some degree of specificity may be achieved in the PLZF/nuclear receptors interaction. Reciprocal protein interaction assays were then carried out using wild type RARα or RARα 2 K, and functional domains of human PLZF (Figure 3). Full length PLZF interacted with wild type RARα and RARα 2 K in a ligand-independent manner, suggesting that intra molecular interactions do not affect PLZF affinity for RARα. The DNA binding domain of PLZF, comprising 9 C2H2 zinc fingers, interacted significantly with wild type RARα and RARα 2 K, demonstrating that this domain is necessary and sufficient to promote the physical association of RARα with PLZF. None of the other isolated structural domains (BTB/POZ, acidic or proline-rich) demonstrated detectable binding to RARα or to RARα 2 K.

Interaction of RARα with the first three N-terminal zinc fingers of the DNA-binding domain of PLZF. A) Bacterially expressed GST-PLZF 3ZF fusion protein was used to generate an affinity matrix with which (panel B) 35S-labeled full length RARα, RARα 2 K, isolated functional domains (RARα AF1, RARα AF2) or RARα deleted of its AF2-AD and the domain F (RARα Δ403) were incubated in the absence or presence of 1 μM atRA. Receptors bound to PLZF 3ZF resin were then resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and quantified by autoradiography using the ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics, Inc.).

The Zn fingers domain of PLZF is sufficient for the RAR-PLZF interaction. Full length PLZF and isolated domains of PLZF (BTB/POZ, Acidic, intermediary, Proline-rich, Zn Fingers) were synthesized and labeled by in-vitro coupled transcription/translation and then incubated either with a GST-RARα or with RAR K244A-K262A-Sepharose matrix in the absence or presence of 1 μM atRA. Complexes were then resolved and quantified as in Figure 2.

PLZF interacts functionally and physically with RARα and other nuclear receptors

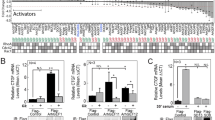

We further assayed the ability of PLZF and PLZF 3ZF to interfere with the transcriptional activity of RARα (Figure 4A). HeLa cells were transfected with a chimeric retinoid-responsive reporter gene insensitive to endogenous receptors, a derivative of RXRα able to bind to glucocorticoid response elements (GRE) and RARα [27]. Adding increasing amounts of PLZF 3ZF efficiently repressed the retinoid-induced activity of RARα, and full length PLZF exhibited a similar property, albeit to a lesser extent (Figure 4A). Overexpression of β-galactosidase did not alter the responsiveness of the system, suggesting that the observed effect is specific for PLZF and its derivatives. A likely explanation for this functional interference would be that PLZF interaction prevents RARα-lignad interaction. We excluded this possibility by carrying out ligand binding experiments which showed no interference of PLZF with the ligand binding activity of RARα (Figure 7, see Additional file 1).

PLZF interferes with the transcriptional activity of RARα and of ERα, GR and VDR. A) Transcriptional activation of RARα is decreased upon overexpression of PLZF 3ZF or of full length PLZF. HeLa cells were transiently transfected with the p(GRARE)tkLuc reporter gene, the pSG5-RARα and the pSG5-RXGR expression vectors together with increasing amounts of pCMV-PLZF 3ZF or pSG5-PLZF expression vectors as indicated. Cells were treated with 1 μM atRA and luciferase activity was assayed 16 h later as described under "Experimental Procedures". Results are expressed as the mean +/- S.D. of at least three individual experiments, with the basal level of luciferase activity arbitrarily set to 1. B) PLZF inhibits the transcriptional activity of ERα, GR and VDR. HeLa cells were transiently transfected with the luciferase reporter genes p(ERE)3tkLuc, pVDREtkLuc or pCF3tkLuc and the pSG5-ERα, pSG5-VDR and pSG5-RXR or pRSV-GR expression vectors respectively. Cells were treated with 1 μM estradiol (E2), 0.1 μM Dexamethasone (Dex), or 1 μM vitamin D3 (Vit D3) respectively. Luciferase activity was assayed 16 h later.

We then investigated whether PLZF acts similarly on other nuclear receptor-controlled systems. The transcriptional activity of ERα, GR and VDR was thus evaluated in conditions analogous to those described above. As for RARα, increasing amounts of PLZF 3ZF repressed the ligand induced activity of ERα, GR and to a lesser extent that of VDR (Figure 4B). This ligand activity was similarly decreased when full length PLZF is added for VDR and GR. ERα turned out to be less sensitive to full length-PLZF mediated inhibition, which was only detectable at high doses of transfected expression vector (Figure 4B). As a control, overexpression of β-galactosidase did not alter the responsiveness of the system (Figure 4A), suggesting that the observed effect is specific for PLZF and its derivatives.

We then wanted to establish whether this transcriptional inhibition was correlated or not to a physical interaction between these proteins. In vitro GST pull-down assays using GST-PLZF 3ZF and 35S radiolabelled GR or ERα were performed. As shown in Figure 5, PLZF 3ZF interacted significantly with ERα and GR in a ligand independent manner. As previously reported [28], we observed that VDR interacted with PLZF (data not shown). These results thus demonstrate that PLZF interacts physically with others nuclear receptors and can interfere with their transcriptional activity, although there is not a strict relationship between dimerization in-vitro and transcriptional inhibition.

PLZF interferes with the dimerization of RARα with RXRα

PLZF interference with the RXRα:RARα heterodimer transcriptional activity suggested that one plausible mechanism for the observed inhibition is a PLZF-triggered decrease of RARα dimerization with RXRα. To test this hypothesis, we first used a mammalian two-hybrid assay (Figure 6A) which reflects the ability of RARs to interact with RXRs [27]. HeLa cells were transfected with a Gal4 responsive gene, the RARα gene fused to the VP16 activation domain gene and the RXRα gene fused to the Gal4 DNA binding domain gene as described before [27]. In the presence of Am580, a selective agonist of RARα, we observed a stronger luciferase activity in our system, reflecting a more stable interaction between RARα and RXRα. Adding increasing amounts of PLZF 3ZF, as well as full length PLZF reduced the luciferase activity (Figure 6A), suggesting that PLZF interferes with the dimerization of RARα with RXRα. Overexpression of the LacZ gene did not alter the responsiveness of the system, suggesting that the observed effect is specific for PLZF. We then tested the ability of PLZF to prevent RXR:RAR dimer formation by in vitro protein interaction assays by using a GST-RARα fusion protein and radiolabeled RXRα. As shown in Figure 6B, RARα and RXRα interacted constitutively, however, this interaction was potentiated in the presence of 1 μM atRA. Adding increasing amounts of in vitro translated PLZF protein inhibited both the ligand-independent and the ligand-dependent dimerization between RARα and RXRα, whereas similar amounts of control protein (luciferase) did not alter the interaction between RARα and RXRα. Thus the dimerization of RAR with RXR is specifically inhibited by PLZF in a dose-dependent manner, and the inhibition occurs irrespective of the presence of the ligand. In this respect, we also observed that the ligand-dependent dimerization occured in the presence of TTNPB and Am580, two synthetic retinoids. Moreover, the complexation of RARα to Ro41-5253, a synthetic antagonist, did not modify the PLZF-mediated inhibition of RXR-RAR dimerization, strongly suggesting that PLZF binding to RARα is not affected by ligand-induced structural transitions (Figure 7, see additional file 1).

PLZF decreases the dimerization of RARα with RXRα. A) PLZF decreases the interaction of RAR with RXR in intact cells. HeLa cells were transiently transfected with the UAS-tkLuc reporter gene, the pCMV-Gal4-RXRα and the pCMV-VP16-RARα expression vectors and the pSG5-PLZF or the pCMV-PLZF 3ZF as indicated. The pRSV-βGal expression was used as a control in this 2-hybrid assay. Cells were treated with 0.1 μM of the RARα-selective ligand Am580, and luciferase activity was assayed 16 h later as described in Figure 4. B) PLZF inhibits the dimerization of RARα with RXRα in-vitro. RXRα was synthesized in vitro as a 35S-labeled protein, by coupled transcription/translation, in rabbit reticulocyte lysate and was incubated with increasing amounts of PLZF or of control protein (luciferase) as non-labeled proteins. Protein mixes were then incubated with a GST-RARα-Sepharose affinity matrix with 1 μM atRA or not. Proteins were then separated and quantified as indicated in Figure 1. Representative autoradiographs are shown. Bar graphs show data averaged from 2 independent experiments.

Conclusions

In this report we show that PLZF engages functional interaction with several nuclear receptors, acting as a general repressor of their ligand-induced transcriptional activity as assayed by transient transfection experiments. A more detailed analysis of the PLZF-RARα interaction showed that this functional interaction stems from a direct, physical interaction of RAR with PLZF. We also noted that bcl6, a transcriptional repressor [29] sharing structural and functional similarities with PLZF, also interacted with RARα (data not shown). Alignment of PLZF and bcl-6 sequences did not however reveal significant homologies that could represent a conserved motif of interaction. While the domain of PLZF required for the interaction with RAR maps, and is limited to, the 3 N-terminal zinc fingers, the structural integrity of RAR seems to be required for a strong interaction, although the isolated ligand binding domain is able to interact significantly with PLZF. The AF2 activation domain (helix H12) is not required for this interaction, as shown by the interaction observed with the hRARα ΔAF2 and the hRARα 2 K mutants. This further suggests that PLZF is unlikely to interact with the coactivator binding interface. Furthermore, PLZF exerted a similar effect when a mutation preventing the association of corepressors to RARα was introduced. This mutation is located in the domain D (RARα AHT, see [27]). Thus, our data instead suggest that PLZF interferes with the RXR-RAR dimerization process, and not with the ligand binding activity of RARα, based on experiments carried out in intact cells or in an acellular system. This is in contrast with a previous report showing that PLZF inhibits the VDR transcriptional activity by forming a complex with the VDR-RXR dimer, the formation of which requiring the DNA binding domain of VDR and the BTB/POZ domain of PLZF [28]. In this case, increased recruitment of corepressors to the VDR-RXR complex through the BTB/POZ domain is unlikely to be the mechanism of repression, since histone deacetylase inhibitors such as trichostatin A (TSA) did not perturb the observed inhibition [28]. Similarly, we observed that the addition of TSA or sodium butyrate did not alter the outcome of PLZF overexpression on the RXR-RAR dimer transcriptional activity, ruling out a possible inhibition through increased corepressor binding to the RXR-RAR complex.

Recently, Ward and collaborators [28] reported that RARα was unable to bind to PLZF in GST pull down experiments and to interfere with RAR-mediated transcriptional activation in the lymphoma cell line U937. While the activity of PLZF may be conditioned by cell-specific factors, it is not clear why in-vitro protein-protein interaction assays did not reveal such an interaction. We showed that domains involved in the PLZF-RAR interactions are clearly distinct from these involved in PLZF-VDR interaction, and it is likely that subtle differences in the experimental procedures make a direct comparison very difficult.

Alternative splicing of the PLZF pre mRNA species generates potentially several proteins deleted from the BTB/POZ domain [30]. We also noted that the isolated 3ZF molecule was a better inhibitor of the RXR-RAR response when carrying out dose-response assays, and that the interaction of full length PLZF with RAR is weak when compared to other known interacting proteins such as coactivators and corepressors. This suggests that a possible functional interference will occur at high PLZF concentrations. Although we have not evaluated the respective half-lives of each PLZF species, it is interesting to note that P19 cells express only the spliced form corresponding to the truncated protein, and that the full length transcript appears upon atRA treatment. The ratio of spliced transcripts to full length transcripts also varies in a tissue-specific manner [31], suggesting that the degree of interference of PLZF with the RAR-RXR pathway may vary similarly, although this point remains speculative at this stage. PLZF mRNA expression is regulated both spatially and temporally in the developping central nervous system, suggesting that it may exert some control on the retinoid pathway. Indeed, a high level of PLZF expression indicates rhombomeric boundaries [31] and this up regulation is observed concomitantly to a down regulation of other markers of segmentation, and most notably Hox genes and Krox-20, which are known to be regulated by retinoic acid and to play a crucial role in hindbrain anterioposterior patterning (reviewed in [32]).

Methods

Materials

atRA was obtained from Sigma. DNA restriction and modification enzymes were purchased from Promega (Charbonnières, France). Polyethyleneimine (ExGen 500) was obtained from Euromedex (Souffelweyersheim, France), and [35S]methionine from Amersham (Les Ulis, France).

Plasmids

The yeast expression plasmid pLex12-RARK244A-K262A was generated by insertion of the RARK244A-K262A cDNA [26] between the Bgl2 andXba1 sites of pLex10, a LexA DBD fusion vector. pSG5-PLZF was a gift from J.D. Licht, while p(GRARE)3tkLuc, pSG5-RXGR, pSG5-hRARα, pSG5-RARα AHT, pSG5-RARα K244A-K262A, pSG5-RARα AF1, pSG5-RARα AF2 and pSG5-RAR)403 were described elsewhere [26, 27, 33]. pCMV-Gal4-hRXRα LBD and pCMV-VP16-hRARα were obtained from Dr T. Perlmann [34]. The UAS-tk-Luc reporter gene was a gift from V. K. Chatterjee and contains two 17 mer UAS Gal4 response elements upstream of the tk promoter [35]. The pGST fusion plasmids (pGST-PLZF 3ZF, pGST-POZ, pGST-Acidic, pGST-X, pGST-PRO, pGST-Zn) and the expression vector pCMV-PLZF 3ZF were engineered using the Gateway Cloning Technology kit (InVitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). All constructs were checked by automatic sequencing.

Yeast 2-hybrid library screen

An ovary cDNA library (in pACT2 vector, Clontech) was screened using the L40a yeast strain transformed with the pLex10-RARK244A-K262A vector, essentially as described in [29].

Cell Culture and Transfections

HeLa Tet-On cells were cultured as monolayer in Dulbecco's minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. Cells were treated for 16 h with atRA or Am580 at a final concentration of 10-6M and 10-7M respectively as indicated. Transfections were performed using the polyethyleneimine coprecipitation as described previously [36]. The luciferase assay was performed with the Bright-Glo Luciferase assay system from Promega (Charbonnières, France).

GST pull-down experiments

The GST vectors were transformed into the Escherichia coli strain BL21. GST fusion proteins (X-GST) were adsorbed on glutathione (GSH)-sepharose beads as previously described [36]. 35S-labeled proteins were synthesized with the Quick T7 TnT kit (Promega). 5 μL of each reaction were diluted in 150 μL of GST binding buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH7.4, 100 mM KCl, 0.05% NP40, 1 mM DTT, 20% glycerol, 1 mg/ml BSA) and agitated slowly on a rotating wheel for 2 h at 4°C, in the presence or not of ligand, with 40 μL of a 50% X-GST-sepharose slurry. Unbound material was removed by three successive washes of Sepharose beads with 200 μL of GST wash buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH7.4, 100 mM KCl, 0.1% NP40, 1 mM DTT, 20% glycerol). Resin-bound proteins were then resolved by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and quantified with a Storm 860 phosphorimager (Molecular Dynamics). Values were averaged from at least three independent experiments carried out with two different bacterial extracts.

Statistical analysis

All incubations or assays were performed at least in triplicate. Measured values were used to calculate mean +/- S.E.M. Calculations were carried out using the Prism software (GraphPAD Inc., San Diego, CA).

References

Lefebvre P: Molecular basis for designing selective modulators of retinoic acid receptor transcriptional activities. Curr Drug Targets Immune Endocr Metabol Disord. 2001, 1: 153-164.

Rachez C, Freedman LP: Mediator complexes and transcription. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001, 13: 274-280. 10.1016/S0955-0674(00)00209-X.

Li X, Lopez-Guisa JM, Ninan N, Weiner EJ, Rauscher FJ, Marmorstein R: Overexpression, purification, characterization, and crystallization of the BTB/POZ domain from the PLZF oncoprotein. J Biol Chem. 1997, 272: 27324-27329. 10.1074/jbc.272.43.27324.

Lin RJ, Nagy L, Inoue S, Shao WL, Miller WH, Evans RM: Role of the histone deacetylase complex in acute promyelocytic leukaemia. Nature. 1998, 391: 811-814. 10.1038/35895.

Grignani F, DeMatteis S, Nervi C, Tomassoni L, Gelmetti V, Cioce M, et al: Fusion proteins of the retinoic acid receptor-alpha recruit histone deacetylase in promyelocytic leukaemia. Nature. 1998, 391: 815-818. 10.1038/35901.

Melnick AM, Westendorf JJ, Polinger A, Carlile GW, Arai S, Ball HJ, et al: The ETO protein disrupted in t(8;21)-associated acute myeloid leukemia is a corepressor for the promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger protein. Mol Cell Biol. 2000, 20: 2075-2086. 10.1128/MCB.20.6.2075-2086.2000.

Gelmetti V, Zhang J, Fanelli M, Minucci S, Pelicci PG, Lazar MA: Aberrant recruitment of the nuclear receptor corepressor-histone deacetylase complex by the acute myeloid leukemia fusion partner ETO. Mol Cell Biol. 1998, 18: 7185-7191.

Ball HJ, Melnick A, Shaknovich R, Kohanski RA, Licht JD: The promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger (PLZF) protein binds DNA in a high molecular weight complex associated with cdc2 kinase. Nucl Acid Res. 1999, 27: 4106-4113. 10.1093/nar/27.20.4106.

Li JY, English MA, Ball HJ, Yeyati PL, Waxman S, Licht JD: Sequence-specific DNA binding and transcriptional regulation by the promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger protein. J Biol Chem. 1997, 272: 22447-22455. 10.1074/jbc.272.36.22447.

Sitterlin D, Tiollais P, Transy C: The RAR alpha-PLZF chimera associated with Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia has retained a sequence-specific DNA-binding domain. Oncogene. 1997, 14: 1067-1074. 10.1038/sj.onc.1200916.

Koken MH, Reid A, Quignon F, Chelbi-Alix MK, Davies JM, Kabarowski JH, et al: Leukemia-associated retinoic acid receptor alpha fusion partners, PML and PLZF, heterodimerize and colocalize to nuclear bodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997, 94: 10255-10260. 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10255.

Zhong S, Salomoni P, Pandolfi PP: The transcriptional role of PML and the nuclear body. Nat Cell Biol. 2000, 2: E85-E90. 10.1038/35010583.

Shaknovich R, Yeyati PL, Ivins S, Melnick A, Lempert C, Waxman S, et al: The promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger protein affects myeloid cell growth, differentiation, and apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 1998, 18: 5533-5545.

Barna M, Hawe N, Niswander L, Pandolfi PP: PLZF regulates limb and axial skeletal patterning. Nat Genet. 2000, 25: 166-172. 10.1038/76014.

Chen SJ, Zelent A, Tong JH, Yu HQ, Wang ZY, Derre J, et al: Rearrangements of the retinoic acid receptor alpha and promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger genes resulting from t(11;17)(q23;q21) in a patient with acute promyelocytic leukemia. J Clin Invest. 1993, 91: 2260-2267.

Chen Z, Guidez F, Rousselot P, Agadir A, Chen SJ, Wang ZY, et al: PLZF-RAR alpha fusion proteins generated from the variant t(11;17)(q23;q21) translocation in acute promyelocytic leukemia inhibit ligand-dependent transactivation of wild-type retinoic acid receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994, 91: 1178-1182.

Licht JD, Chomienne C, Goy A, Chen A, Scott AA, Head DR, et al: Clinical and molecular characterization of a rare syndrome of acute promyelocytic leukemia associated with translocation (11;17). Blood. 1995, 85: 1083-1094.

Licht JD, Shaknovich R, English MA, Melnick A, Li JY, Reddy JC, et al: Reduced and altered DNA-binding and transcriptional properties of the PLZF-retinoic acid receptor-alpha chimera generated in t(11;17)-associated acute promyelocytic leukemia. Oncogene. 1996, 12: 323-336.

Guidez F, Huang W, Tong JH, Dubois C, Balitrand N, Waxman S, et al: Poor response to all-trans retinoic acid therapy in a t(11;17) PLZF/RAR alpha patient. Leukemia. 1994, 8: 312-317.

Koken MH, Daniel MT, Gianni M, Zelent A, Licht J, Buzyn A, et al: Retinoic acid, but not arsenic trioxide, degrades the PLZF/RARalpha fusion protein, without inducing terminal differentiation or apoptosis, in a RA-therapy resistant t(11;17)(q23;q21) APL patient. Oncogene. 1999, 18: 1113-1118. 10.1038/sj.onc.1202414.

Wang ZG, Delva L, Gaboli M, Rivi R, Giorgio M, CordonCardo C, et al: Role of PML in cell growth and the retinoic acid pathway. Science. 1998, 279: 1547-1551. 10.1126/science.279.5356.1547.

Zhong S, Delva L, Rachez C, Cenciarelli C, Gandini D, Zhang H, et al: A RA-dependent, tumour-growth suppressive transcription complex is the target of the PML-RARalpha and T18 oncoproteins. Nat Genet. 1999, 23: 287-295. 10.1038/15463.

Doucas V, Tini M, Egan DA, Evans RM: Modulation of CREB binding protein function by the promyelocytic (PML) oncoprotein suggests a role for nuclear bodies in hormone signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999, 96: 2627-2632. 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2627.

Renaud JP, Rochel N, Ruff M, Vivat V, Chambon P, Gronemeyer H, et al: Crystal structure of the RAR-gamma ligand-binding domain bound to all-trans retinoic acid. Nature. 1995, 378: 681-689. 10.1038/378681a0.

Bourguet W, Vivat V, Wurtz JM, Chambon P, Gronemeyer H, Moras D: Crystal structure of a heterodimeric complex of RAR and RXR ligand-binding domains. Mol Cell. 2000, 5: 289-298.

Mouchon A, Delmotte M-H, Formstecher P, Lefebvre P: Allosteric Regulation Of The Discriminative Responsiveness of Retinoic Acid Receptor to Natural and Synthetic Ligands By Retinoid X Receptor And DNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1999, 19: 3073-3085.

Depoix C, Delmotte MH, Formstecher P, Lefebvre P: Control of retinoic acid receptor heterodimerization by ligand-induced structural transitions. a novel mechanism of action for retinoid antagonists. J Biol Chem. 2001, 276: 9452-9459.

Ward JO, McConnell MJ, Carlile GW, Pandolfi PP, Licht JD, Freedman LP: The acute promyelocytic leukemia-associated protein, promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger, regulates 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3)-induced monocytic differentiation of U937 cells through a physical interaction with vitamin D(3) receptor. Blood. 2001, 98: 3290-3300. 10.1182/blood.V98.12.3290.

Dhordain P, Albagli O, Lin RJ, Ansieau S, Quief S, Leutz A, et al: Corepressor SMRT binds the BTB/POZ repressing domain of the LAZ3/BCL6 oncoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997, 94: 10762-10767. 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10762.

Zhang T, Xiong H, Kan LX, Zhang CK, Jiao XF, Fu G, et al: Genomic sequence, structural organization, molecular evolution, and aberrant rearrangement of promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999, 96: 11422-11427. 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11422.

Lin B, Chen GQ, Xiao D, Kolluri SK, Cao X, Su H, et al: Orphan receptor COUP-TF is required for induction of retinoic acid receptor beta, growth inhibition, and apoptosis by retinoic acid in cancer cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2000, 20: 957-970. 10.1128/MCB.20.3.957-970.2000.

Gavalas A: ArRAnging the hindbrain. Trends in Neurosciences. 2002, 25: 61-64. 10.1016/S0166-2236(02)02067-2.

Delmotte MH, Tahayato A, Formstecher P, Lefebvre P: Serine 157, a retinoic acid receptor alpha residue phosphorylated by protein kinase C in vitro, is involved in RXR.RARalpha heterodimerization and transcriptional activity [In Process Citation]. J Biol Chem. 1999, 274: 38225-38231. 10.1074/jbc.274.53.38225.

Perlmann T, Jansson L: A novel pathway for vitamin A signaling mediated by RXR heterodimerization with NGFI-B and NURR1. Genes Dev. 1995, 9: 769-782.

Collingwood TN, Butler A, Tone Y, Clifton-Bligh RJ, Parker MG, Chatterjee VKK: Thyroid hormone-mediated enhancement of heterodimer formation between thyroid hormone receptor beta and retinoid X receptor. J Biol Chem. 1997, 272: 13060-13065. 10.1074/jbc.272.20.13060.

Lefebvre B, Mouchon A, Formstecher P, Lefebvre P: H11–H12 Loop Retinoic Acid Receptor Mutants Exhibit Distinct trans-Activating and trans-Repressing Activities in the Presence of Natural or Synthetic Retinoids. Biochemistry. 1998, 37 (26): 9240-9249. 10.1021/bi9804840.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Drs D. Leprince and S. Deltour (Institut de Biologie de Lille) for initial advice about the yeast two-hybrid system. We also thank Drs J.D. Licht, T. Perlmann and V.K. Chatterjee for the gift of plasmids. P.M. is supported by a fellowship from the Ministère de la Recherche et des Nouvelles Technologies. We acknowledge suggestions and discussions of Drs C. Rachez, B. Lefebvre and P. Sacchetti. This work was supported by grants from INSERM and Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

41076_2003_7_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Additional File 1: PLZF and ligand interaction with RARα. A) PLZF decreases the dimerization of RAR with RXR in a ligand structure-independent manner. RXR-RAR interaction was tested by GST pulldown assays as in Figure 6B in the presence of RAR agonists (atRA, CD367, Am580) or of an antagonist (Ro41-5253). B) The interaction of PLZF with RAR does not alter RAR ligand binding affinity. Ligand binding assays were carried out as follows: The GST-RARα was expressed as described in the Materials and Methods section. PLZF or a control protein were synthesized with the Quick T7 TnT kit (Promega) with unlabeled methionine. GST-RARα was incubated on a rotating wheel for 2 h at 4°C with increased amounts of PLZF or of control protein in the presence of 20 nM [3H] atRA (50 Ci/mmol, PerkinElmer), and with or without 1 μM unlabeled atRA to assess non specific binding. Conditions were strictly similar to those used in GST pulldown experiments. 20 μL of 50% Sepharose-GSH were then added and incubated on a rotating wheel for 1 h at 4°C. Unbound material was removed by three successive washes of Sepharose beads with 200 μL of ice-cold 1 × PBS. The amount of [3H] bound to the matrix was determined by liquid scintillation counting. Results are plotted as a function of atRA concentration. They demonstrate that the ligand binding activity of RARα is not altered in the presence of either PLZF or a control protein (luciferase). (PDF 52 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Martin, P.J., Delmotte, MH., Formstecher, P. et al. PLZF is a negative regulator of retinoic acid receptor transcriptional activity. Nucl Recept 1, 6 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-1336-1-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-1336-1-6