Abstract

Type 2 diabetes mellitus is a major risk factor for melioidosis, which is caused by Burkholderia pseudomallei. Our previous study has shown that polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) from diabetic subjects exhibited decreased functions in response to B. pseudomallei. Here we investigated the mechanisms regulating cytokine secretion of PMNs from diabetic patients which might contribute to patient susceptibility to bacterial infections. Purified PMNs from diabetic patients who had been treated with glibenclamide (an ATP-sensitive potassium channel blocker for anti-diabetes therapy), showed reduction of interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-8 secretion when exposed to B. pseudomallei. Additionally, reduction of these pro-inflammatory cytokines occurred when PMNs from diabetic patients were treated in vitro with glibenclamide. These findings suggest that glibenclamide might be responsible for the increased susceptibility of diabetic patients, with poor glycemic control, to bacterial infections as a result of its effect on reducing IL-1β production by PMNs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Patients with diabetes in general show increased susceptibility to bacterial infections but the mechanisms by which this occurs are poorly understood1,2,3. In Thailand, type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) is the most common underlying condition associated with melioidosis, a serious infection caused by the soil-dwelling Gram-negative bacillus, Burkholderia pseudomallei4. This infectious disease is endemic in Southeast Asia and Northern Australia. In Northeast Thailand, melioidosis accounts for 20% of cases of community-acquired septicemia with a mortality rate of 50%5,6. Animal models have shown that polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) play a critical role in B. pseudomallei infection7,8. Previously, we have demonstrated that PMNs from diabetic patients had impaired functions, including phagocytosis, migration and apoptosis, in response to B. pseudomallei infection9. However, the cytokine response has not yet been elucidated in melioidosis, even though it is one of the crucial functions of PMNs10.

It has been demonstrated that Toll-like receptors (TLRs) play a critical role in melioidosis pathogenesis11 and MyD88, the key TLR adaptor protein, regulates tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α production in response to B. pseudomallei12. TLR ligands and TNF-α are both potent activators of the transcription factor NF-κB, the main positive regulator of transcription of a wide range of pro-inflammatory cytokine mRNA including precursor interleukin (IL)-1β (pro-IL-1)13. However, this pro-form of IL-1β is inactive and requires activation via a protein complex called the inflammasome14,15. The mature form of IL-1β induces the production of a wide range of cytokines and chemokines such as CC-chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2), CCL3 and CXC chemokine ligand 8 (also known as IL-8) through NF-κB activation15,16,17.

Caspase-1-dependent immune mechanisms play an essential role in resistance against B. pseudomallei infection in murine macrophages18. Reduction or inhibition of inflammasome activation in PMNs may contribute to the increased susceptibility to this infection19. Additionally, in vivo data showed that PMNs of diabetic patients compared to healthy subjects presented an impaired ability to produce sufficient key cytokines, especially IL-1β in response to E. coli LPS20. Those findings then led us to determine the effect of DM treatment by glibenclamide (international nonproprietary name), also known as glyburide (United States adopted name), which is a common treatment for DM in the World Health Organization Model List of Essential Medicines. Glibenclamide works by inhibiting ATP-sensitive potassium channels in pancreatic beta cells resulting in an increase in intracellular calcium and subsequent stimulation of the release of insulin from beta cells and increased glucose uptake into the cells. However, glibenclamide is also known to have an inhibitory effect on inflammasome assembly21. Our results suggest possible mechanisms involved in the regulation of cytokine production in response to B. pseudomallei in PMNs of diabetic patients who had been treated with glibenclamide.

RESULTS

PMNs of diabetic subjects exhibit reduced pro-inflammatory cytokine production in response to B. pseudomallei, LPS, flagellin and TNF-α

First, we evaluated the kinetics of proinflammatory cytokine production and found that TNF-α could be detected in supernatants with similar levels and kinetics for PMNs from diabetic and healthy subjects (Figure 1A). In contrast, significantly lower levels of IL-1β and IL-8 were secreted by PMNs from diabetic patients (Figure 1A; P < 0.001) and observed over a range of 0.3–10 multiplicity of infection (MOI) (Figure 1B; P < 0.05), indicating that this phenotype is unlikely to result from reduced contact between PMNs of diabetic subjects and the bacteria. We also confirmed that there was no difference in bacterial loads and PMN viability between the two subjects groups over the time course investigated (see Supplementary Fig. S3 and S4 online).

PMNs from diabetic subjects exhibit reduced pro-inflammatory cytokine production.

(A) Purified PMNs of 3 healthy (closed circles) and 3 DM (open circles) subjects (one glibenclamide alone and two combination treatment) were infected with B. pseudomallei at MOI of 0.3:1 for 1, 2, 4, 16 and 24 h. TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-8 were measured in supernatants by ELISA. The circles indicate means ± s.d. Asterisks indicate significant differences between healthy and DM subjects at the same time point by paired t test. (B) Purified PMNs from 2 healthy and 2 DM subjects (one glibenclamide and one combination treatment) stimulated for 16 h with various B. pseudomallei MOIs, various concentrations of LPS, flagellin, or the recombinant human TNF-α (rTNF-α). Cell supernatants were analyzed for IL-1beta and IL-8 by ELISA. Error bars represent means ± s.d. Data represents one of two independent experiments with similar results. Asterisks indicate significant differences between healthy and DM subjects at the same concentration by paired t test. **P < 0.01 and *P < 0.05. ns, non significant.

In order to confirm whether recognition of bacterial components by PMNs from diabetic subjects was impaired, we investigated their ability to produce IL-1β and IL-8 after stimulation with defined TLR ligands; LPS and flagellin are recognized by TLR4 and TLR5 respectively and TNF-α. In PMNs from both diabetic and healthy subjects, less IL-1β and IL-8 were induced in response to TLR ligands compared to B. pseudomallei infection at the concentrations used. These data indicate that B. pseudomallei is capable of activating cytokine production from PMNs through pathways other than TLR4, TLR5 and the TNF-α receptor. These data are also consistent with our previous studies showing that LPS could stimulate purified PMNs to produce cytokines22. Moreover, they provide compelling evidence that PMNs from diabetic subjects fail to produce IL-1β and induce less IL-8 upon activation of such receptors compared with PMNs from healthy controls.

B. pseudomallei activates PMNs to produce IL-1β via a caspase-1-dependent pathway

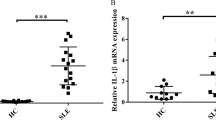

In macrophages, IL-1β is proteolytically processed to its active form by caspase-1, in response to B. pseudomallei14,15,16. In PMNs, we found that caspase-1 inhibition significantly reduced IL-1β and IL-8 production in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2A; P < 0.05), suggesting that B. pseudomallei triggers IL-1β processing through the activation of a caspase-1-dependent pathway. Western blot analysis confirmed that the activated 17.5-kDa fragment of IL-1β was detected from supernatant of infected healthy PMNs (Figure 2B and Supplementary Fig. 5S online). Real-time quantitative RT-PCR indicated that both LPS and B. pseudomallei induced transcription of IL-1β, IL-8, caspase-1 and NLRP3 genes relative to medium alone (Figure 2C); however, transcripts of these genes were significantly less abundant in PMNs from diabetic subjects upon treatment with LPS or B. pseudomallei (Figure 2C; P < 0.05). These results suggest that the inflammasome-associated pathway is impaired in PMNs from diabetic subjects.

B. pseudomallei activate PMNs to produce IL-1β via a caspase1-dependent pathway.

(A) IL-1β and IL-8 were produced from purified PMNs of 3 healthy and 3 DM subjects (two glibenclamide alone and one combination treatment) treated with various concentrations of caspase-1 inhibitor (inh) before being infected with B. pseudomallei at an MOI of 0.3:1 for 16 h. The data represent one of three independent experiments with similar results expressed as means ± s.d. Asterisks indicate significant differences between no caspase-1inh and infected with B. pseudomallei by Two Way ANOVA. (B) Purified PMNs from healthy subject and DM who had been treated with combination drug were infected for 1 h with B. pseudomallei and IL-1β in supernatant was assessed by Western blot using antibody specific for IL-1β. The full-length blots on the same conditions are presented in Supplementary Figure S5. (C) Purified PMNs were co-cultured for 4 h with B. pseudomallei at an MOI of 0.3:1 or LPS at 300 ng/ml. Expression of cytokine-related mRNA (IL-1beta, IL-8, caspase1 and NLRP3) was detected by using real-time PCR. Representative data from one experiment is expressed as means ± s.d. Asterisks indicate significant differences between the open columns compared diabetic to healthy subjects at the same condition by paired t test. ***P < 0.001 **P < 0.01 and *P < 0.05. No asterisk or ns, non significant.

IL-1β induces IL-8 production in PMNs in response to pathogens

We found that IL-8 production in PMNs from diabetic subjects was induced by rIL-1β in a dose-dependent manner, although at lower levels than observed with PMNs from healthy donors (Figure 3A; P < 0.001 and Supplementary Fig. S1 online). We further evaluated whether additional IL-1β could compensate reduced IL-8 production of diabetic subjects. We found that rIL-1β induced IL-8 production in B. pseudomallei infected PMNs from both healthy and diabetic subjects, despite the lower level of IL-8 released by PMNs from diabetic subjects. This suggests that signaling downstream of the IL-1 receptor (IL-1R) could be perturbed in PMNs from diabetic subjects.

IL-1β induces IL-8 production in response to pathogens.

(A) Purified PMNs of 3 healthy and 3 diabetic subjects (two glibenclamide alone and one combination treatment) were pretreated for 30 min with various concentrations of the recombinant human IL-1β (rIL-1β) before being infected with B. pseudomallei at an MOI of 0.3:1 or with added medium for 16 h; level of IL-8 in the supernatants was measured. Data are expressed as means ± s.d. Asterisks indicate significant differences between between healthy and diabetic subjects at the same time point by paired t test. (B) IL-8, IL-1β and TNF production by PMNs from 3 healthy subjects were determined by ELISA in the supernatant harvested after PMNs were pretreated for 60 min with anti-human IL-1 RI antibody and infected with B. pseudomallei at MOI of 0.3:1 for 16 h. Data were contained 3 healthy subjects as means ± s.d. and samples were assayed in duplicate. Asterisks indicate significant differences between antibody treatment and B. pseudomallei-infectection alone by One way ANOVA. (C) PMNs treated as in (B) then infected with S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (Sal) or E. coli at the same MOI. Asterisks indicate significant differences between treatment with IL-R1 and medium alone in the same conditions by paired t test. ***P < 0.001 **P < 0.01 and *P < 0.05. No asterisk or ns, non significant.

Next, we treated PMNs from healthy donors with anti-human IL-1RI antibody23 to inhibit IL-1 signaling during infection with B. pseudomallei in vitro. IL-1β and IL-8 levels were decreased in a dose-dependent manner by IL-1RI-specific antibody, whereas levels of TNF-α were not altered (Figure 3B; P < 0.05). The similar blocking effect of anti-IL-1RI at a concentration of 20 μg/ml on cytokine release in response to B. pseudomallei infection was observed following infection with the other Gram-negative bacteria, S. enterica serovar Typhimurium and E. coli (Figure 3C; P < 0.05 and Supplementary Fig. S2 online). In combination with our previous experiments, we conclude that PMNs from diabetic subjects have reduced ability to produce IL-8 upon exposure to B. pseudomallei and other Gram negative bacteria as a result of both their impaired production of and response to IL-1β production.

Glibenclamide, but not metformin reduces IL-1β and IL-8 production

More than half of the patients with type 2 diabetes in endemic areas of melioidosis are prescribed glibenclamide or a combination of glibenclamide and metformin to control blood glucose levels 1(Table 2). To determine whether the impaired cytokine response to B. pseudomallei was an intrinsic property of the diabetic state or also reflected aspects of their treatment, PMNs were incubated with the drugs at a dose comparable to the range of glibenclamide given during oral therapy to the human subjects24,25. Glibenclamide impaired IL-1β and IL-8 production by PMNs from healthy subjects infected in vitro with B. pseudomallei in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 4A; P < 0.05). In contrast, metformin did not affect the production of IL-1β and IL-8 production. Addition of glibenclamide and metformin together produced the same dose-dependent effects as glibenclamide alone (Figure 4A; P < 0.05) indicating that it was the effect of glibenclamide rather than metformin that reduced production of these two cytokines from PMNs. A similar effect was observed upon LPS activation and PMA treatment (Figure 4B). However, IL-8 levels were significantly reduced in proportion to the increasing concentrations of glibenclamide. When using PMNs from diabetic subjects, glibenclamide reduced IL-8 production upon B. pseudomallei infection or PMA activation, but not following LPS activation (Figure 4C). Of note, the level of IL-1β produced by PMNs from diabetic subjects was lower than the limit of detection by ELISA (data not shown). Our data confirm that treatment of PMNs with glibenclamide reduces cytokine production in response to B. pseudomallei infection and other stimuli.

Glibenclamide but not metformin reduces IL-1β and IL-8 production.

(A) Purified PMNs from healthy donors were treated for 1 h with glibenclamide and/or metformin at concentrations as indicated before infection with B. pseudomallei (Bps) at an MOI 0.3:1 for 16 h and IL-1β and IL-8 levels in supernatants were measured by ELISA. Data for 3 healthy subjects are means ± s.d and samples were assayed in duplicate. Asterisks indicate significant differences between treated and non-treated groups by One Way ANOVA. (B, C) Purified PMNs of healthy (B) and glibenclamide-treated diabetic (C) subjects were treated with glibenclamide at concentrations as indicated for 1 h and stimulated by B. pseudomallei (MOI 0.3:1), LPS (300 ng/ml) and PMA (3 ng/ml) for 16 h. IL-1β and IL-8 levels in supernatants were measured. Data are expressed as means ± s.d. and represent one of the three independent experiments with similar results. Asterisks indicate significant differences between glibenclamide-treated and no glibenclamide groups by Two Way ANOVA. ***P < 0.001 **P < 0.01 and *P < 0.05. No asterisk or ns, non significant.

Decreased IL-1β and IL-8 production by PMNs from diabetic subjects associated with glibenclamide treatment

To assess whether specific drug treatment regimes for diabetic subjects influence cytokine production by their PMNs, we compared the cytokine production of PMNs isolated from diabetic subjects (see Table 2 for details of subjects). These subjects had similar levels of glycemic control whichever anti-diabetic drug treatment was used (Table 2). As shown in Figure 5B, significantly lower levels (P < 0.05) of IL-1β and IL-8 were produced by PMNs from diabetic subjects who were being treated with glibenclamide compared to PMNs from patients yet to receive treatment (NDM group). In contrast, levels of TNF-α were not significantly different between the various subject groups (data not shown), which indicated that glibenclamide specifically affects IL-1β and IL-8 production by PMNs in response to B. pseudomallei infection.

Decreased IL-1β and IL-8 production is associated with glibenclamide treatment.

IL-1β and IL-8 levels in supernatants were assessed at 16 h after purified PMNs from five subject groups as mentioned infected with B. pseudomallei at an MOI of 0.3:1. Data are expressed as means ± s.d. Asterisks indicate significant differences between not-treated and healthy subjects and between other DM and not-treated subjects by One Way ANOVA. **P < 0.01 and *P < 0.05. No asterisk or ns, non significant.

Taken together, our findings demonstrate that PMNs from diabetic subjects who are treated with glibenclamide have impaired ability to produce IL-1β and IL8 in response to B. pseudomallei compared to those from healthy donors.

Discussion

Diabetes is the strongest primary risk factor in melioidosis but it is not known which immunological processes underlie the susceptibility of diabetic patients to B. pseudomallei infection. According to our previous study, not only the impairment of PMN functions in diabetic patients9, but also deterioration in early cytokine response is a problem. In this study, possible mechanisms concerned with the regulation of cytokine production in response to B. pseudomallei have been demonstrated in PMNs of diabetic patients. Our first observation was that PMNs from diabetic subjects infected with B. pseudomallei showed reduced production of IL-1β and IL-8 but maintained TNF-α production. These results differ from those in other studies showing that with E. coli LPS stimulation, PMNs from diabetic subjects produced higher amounts of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-8 than healthy controls26. Moreover, another study using a whole-blood stimulation assay has shown that the level of IL-8 was elevated in individuals with type 2 diabetes27. These may be due to difference in the experimental system used, as the study did not mention how DM was controlled among their donors or did not specify generic names of medications.

In addition to controlling IL-1β production in PMNs, we have shown that B. pseudomallei induced PMNs to produce IL-1β through caspase-1-dependent pathway. Previous studies on the inflammasome activation by B. pseudomallei have shown that NLRC4 (Nod-like receptor family) detects the basal body rod component of the type III secretion systems apparatus (rod protein) from B. pseudomallei (BsaK)28. However, PMNs express NLRP3 mRNA but not NLRC4 mRNA, therefore production of IL-1β is primarily dependent on the NLRP3 inflammasome29. Although previous studies show that the inflammasome is normally associated with macrophages in response to B. pseudomallei infection30, in our samples, the contribution of monocyte/macrophage contamination to IL-1β production is likely to be negligible. These suggest that PMNs are an important source of IL-1β in PMN dominant foci. We have confirmed here that B. pseudomallei activated PMNs to upregulate the levels of mRNA expressions of IL-1β, caspase-1 and NLRP3 genes. We also found that these expression levels from poor glycemic control diabetic patients treated with glibenclamide were significantly lower than healthy controls. These results suggest that glibenclamide might affect initial IL-1β production through regulation of transcription or translation. It is also known that IL-1β induces chemokines, such as IL-8, MCP-1 and RANTES, involved in PMN recruitment to infection sites31. In a mouse model, IL-1β led to excessive recruitment of PMNs in the lungs during B. pseudomallei infection29. Unsurprisingly, when we blocked caspase-1 activity in PMNs, not only did it reduce IL-1β production, but also completely suppressed IL-8 production. This suggests that caspase-1 may be an important mediator for PMNs to produce IL-8 in response to B. pseudomallei.

We further demonstrated here that the blockage of IL-1 receptor partially reduced IL-8 secretion from PMNs whereas the level of TNF-α was not influenced, which attested to the specificity of inflammasome activation. This suggests that the inflammasome activation in PMNs could induce IL-8 production independently of IL-1β. Studies in humans have also shown that inhibition of the function of IL-1 using the IL-1R antagonist IL-1ra is associated with increased susceptibility to bacterial infection32. Our results were in accordance with recent studies of early cytokine response in the diabetic mouse model of melioidosis which demonstrated impaired proinflammatory cytokine response; moreover, PMN predominant infiltration at the site of infection was more extensive in diabetic mice33. However, it is not feasible to confirm whether reduced IL-8 production could influence migration of PMNs to infected foci or not in human patients. Therefore, we propose that reduced IL-1β and IL-8 axis, which is a strong activator of PMN functions, may result in impaired activation of PMNs at the infection site and reduced bacterial killing as suggested in the diabetic mouse model33. These suggestions are consistent with the evidence in humans shown that diabetes is the most common underlying condition associated with melioidosis4.

Moreover, we show here that medication for diabetes was associated with decreased cytokine production, especially with glibenclamide treatment. As previously shown, this drug had an inhibitory effect on an inflammasome assembly21. Our data from this study indicate that both gene expression and protein of IL-1β in diabetic subjects were reduced. We suggest that glibenclamide may directly affect the modification of IL-1β or inflammasome related gene expression. These may explain how glibenclamide administration disrupts the ability to produce IL-1β under the poor glucose control of DM. There is not only the direct effect on IL-1β production but the sulfonylureas have also been shown to act as an antagonist of the CXCR234 and to inhibit PMN migration in mice with sepsis35. This drug might have an effect on the failure of PMN migration to the focus of infection, which could increase susceptibility and the risk of severe sepsis in polymicrobial infections, as well as in melioidosis. However, It has been reported that there was reduced mortality in melioidosis patients with preexisting DM who were treated with glibenclamide36. These patients would not have an undesirable overinflammatory state in septic melioidosis; these observations may be explained, at least in part, by our data suggesting that glibenclamide could directly decrease IL-1β and IL-8 production of PMNs infected with B. pseudomallei. So impaired functions of PMNs might be due, in part, to the reduction of IL-1β linked to the effect of glibenclamide during melioidosis. Nevertheless, glibenclamide treatment with poor control of blood glucose level may place diabetic patients at a disadvantage for onset or a recurrence of B. pseudomallei infection.

More than half of diabetic patients in an endemic area of melioidosis in Northeast Thailand have been treated with glibenclamide alone or both glibenclamide and metformin. We found no evidence that metformin, another anti-diabetic drug, directly affects PMN cytokine production. So far, studies of the contribution of metformin to inflammasome activation have provided indirect evidence suggesting that the beneficial effects of metformin in DM might arise from its ability to regulate the inflammasome by enhancing autophagic activity37,38. Further understanding of the effects of anti-diabetes drugs on PMN functions may lead to reduced risks of infection by some other intracellular bacterial pathogens in diabetic patients.

Taken together, the data point to possible mechanisms of impaired cytokine response in PMNs from diabetic subjects infected with B. pseudomallei. Our findings are the first to raise the intriguing mechanism that glibenclamide may act as one of the crucial factors involved in the impairment of innate immunity and the manifestation of bacterial infections in poorly controlled diabetes mellitus.

Methods

Patients

We enrolled 46 diabetic and 32 healthy Thai subjects. All subjects were defined here as aged over 35 years and matched by sex and place of residence (Northeast, Thailand)9. None of the subjects had any signs of acute infectious disease in the three months prior to sampling. The healthy control group consisted of subjects with normal fasting blood glucose levels (3.9–6.2 mmol/L) and normal glycosylated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels (<6.5%). HbA1c was detected by immunoturbidimetric assay and the results were reported following guidelines of the National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program. The healthy subjects were recruited from both blood bank donors and healthy university staff, who live in the same endemic area as patients. The patients involved in this study had been treated with either glibenclamide, metformin, or both. Patients defined as no treatment group were newly diagnosed with diabetic mellitus (NDM), as defined by World Health Organization criteria39. Diabetic patients from each group exhibited very poor glycemic control on the basis of HbA1c levels (>8.5%) previously described9. Unless stated otherwise, only diabetic subjects who had been treated with glibenclamide or metformin alone or a combination of glibenclamide and metformin were enrolled. All diabetic subjects were treated at the Outpatient Department, Khon Kaen Hospital and Khon Kaen Primary Medical Service. The exclusion criteria for both healthy and diabetic volunteers were impaired renal function which causes secondary immunosuppression, defined by a serum creatinine level of ≥0.11 mmol/L. All subjects had creatinine level <0.11 mmol/L and the characteristics of all subjects are shown in Table 2. The collection and analysis of all samples was approved by the Khon Kaen University Ethics Committee for Human Research and the Khon Kaen Hospital Ethics Committee. All subjects provided written informed consent. Each experiment was performed with both healthy and matching DM subjects, generally one healthy versus one matching DM subject, unless stated otherwise.

Microorganisms

B. pseudomallei K96243 strain was grown to mid-logarthmic phase at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth. Bacterial growth was assessed by measuring the optical density at 600 nm. Generally, an absorbance index of 1 was equivalent to109 CFU/mL of bacteria and the number of viable bacteria (colony-forming units) in inocula was determined by retrospective plating of serial ten-fold dilutions on LB agar. There was no outlier of the variation of the inoculating dose within batches. Live B. pseudomallei was handled under the US Centers for Disease Control regulations for research at containment level 3. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium ATCC 13311 and Escherichia coli ATCC 25422 were obtained from Microbial Culture Collection Center, Thailand, grown overnight in LB broth at 37°C and enumerated as above.

PMN isolation and stimulation

We isolated PMNs from heparinized venous blood by dextran sedimentation and Ficoll-Paque centrifugation, as previously described9 and the resulting cell preparation was confirmed to consist of >95% PMNs by flow cytometry and by CD14 staining. The morphology of PMNs was also determined by Giemsa staining and microscopy and the cell viability was >98%, as determined by trypan blue exclusion. Unless stated otherwise, purified PMNs at a concentration of 2.5 × 106 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 culture medium (Gibco) were incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 16 h with B. pseudomallei at an MOI of 0.3:1 or activated with 300 ng/ml of LPS (from E coli, Sigma), 300 ng/ml of B. pseudomallei flagellin (BPSL3319, obtained from Dr. Philip L. Felgner, University of California, Irvine, USA), 30 ng/ml of recombinant human TNF-α (BD Biosciences), or 5 ng/ml of human rIL-1β (eBiosciences). In some experiments, the following reagents were added to PMNs for 1 h prior to infection with B. pseudomallei (MOI 0.3:1), or treatment with LPS (300 ng/ml), or 3 ng/ml of phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA, Sigma). The reagents were 10 μg/ml caspase-1 inhibitor VI (Calbiochem), 20 μg/ml anti-human IL-1RI neutralizing antibody (R&D systems), or anti-diabetic drugs: 50 μM glibenclamide (Sigma) which is comparable to human blood concentration achieved following a 20 mg oral dose40, or 50 μM metformin (Sigma) which is comparable to human blood concentration achieved following a 2000 mg oral dose41.

Cytokine measurement

When indicated, we assessed IL-1β, IL-8 and TNF-α concentration in the supernatant of PMN cultures in duplicate by ELISA (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The supernatants were stored at −80°C until the cytokine assay.

Reverse transcription and real time PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). Reverse transcription reactions were performed using Improm-II reverse transcriptase (Promega) according to the manufacturers' instructions. Transcript levels were determined by SYTO9-based real-time PCR using an ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). GAPDH transcripts were quantified as an internal control. The relative expression level was calculated by the 2−ΔΔCt method. The sequences of all transcripts in this study were retrieved from PubMed (www.ncbi.nln.nih.gov) and specific primers (listed in Table 1) were designed using the NCBI primer designing tool. We also confirmed the melting peak analysis of real time PCR products specific to individual gene.

Western blot analysis of mature IL-1β

The supernatants of PMN cultures were collected after 16 h. The samples were concentrated using nanosep 3 k omega kit (Pall Corporation) and lysed in 2× sample buffer in the presence of protease inhibitors. Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Pall Corporation). Membranes were blocked with 5% (w/v) skimmed milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) and were incubated with rabbit primary antibodies against human IL-1β (Cell Signaling, 1: 1000 dilution) for 1 h at room temperature. After three washes in TBST, the membranes were incubated with horseradish-peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling, 1: 2000 dilution) for 1 h at room temperature. After three TBST washes, antibody binding was visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce).

Statistics

Statistical analysis (two way ANOVA and one way ANOVA with post test Bonferroni and paired t test) was performed by using Graphpad PRISM statistical software version 5 (Graphpad 5). P values ≤0.05 were taken to be significant.

References

Joshi, N., Caputo, G. M., Weitekamp, M. R. & Karchmer, A. W. Infections in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus. New England Journal of Medicine 341, 1906–1912 (1999).

Shah, B. R. & Hux, J. E. Quantifying the Risk of Infectious Diseases for People With Diabetes. Diabetes Care 26, 510–513 (2003).

Koh, G., Peacock, S. J., Poll, T. & Wiersinga, W. J. The impact of diabetes on the pathogenesis of sepsis. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases, 1–10 (2011).

Suputtamongkol, Y. et al. Risk factors for melioidosis and bacteremic melioidosis. Clin Infect Dis 29, 408–413 (1999).

Cheng, A. C. & Currie, B. J. Melioidosis: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology and Management. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 18, 383–416 (2005).

White, N. J. Melioidosis. Lancet 361, 1715–1722 (2003).

Easton, A., Haque, A., Chu, K., Lukaszewski, R. & Bancroft, G. J. A Critical Role for Neutrophils in Resistance to Experimental Infection with Burkholderia pseudomallei. Journal of Infectious Diseases 195, 99–107 (2007).

Reckseidler-Zenteno, S. L., DeVinney, R. & Woods, D. E. The Capsular Polysaccharide of Burkholderia pseudomallei Contributes to Survival in Serum by Reducing Complement Factor C3b Deposition. Infect. Immun. 73, 1106–1115 (2005).

Chanchamroen, S., Kewcharoenwong, C., Susaengrat, W., Ato, M. & Lertmemongkolchai, G. Human Polymorphonuclear Neutrophil Responses to Burkholderia pseudomallei in Healthy and Diabetic Subjects. Infect. Immun. 77, 456–463 (2009).

Nathan, C. Neutrophils and immunity: challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Immunol 6, 173–182 (2006).

Wiersinga, W. J. et al. Toll-Like Receptor 2 Impairs Host Defense in Gram-Negative Sepsis Caused by Burkholderia pseudomallei (Melioidosis). PLoS Med 4, e248 (2007).

Wiersinga, W. J., Wieland, C. W., Roelofs, J. J. T. H. & van der Poll, T. MyD88 Dependent Signaling Contributes to Protective Host Defense against Burkholderia pseudomallei. PLoS ONE 3, e3494 (2008).

Bryant, C. & Fitzgerald, K. A. Molecular mechanisms involved in inflammasome activation. Trends Cell Biol 19, 455–464 (2009).

Schroder, K., Zhou, R. & Tschopp, J. The NLRP3 Inflammasome: A Sensor for Metabolic Danger? Science 327, 296–300 (2010).

Donath, M. Y. & Shoelson, S. E. Type 2 diabetes as an inflammatory disease. Nature reviews. Immunology 11, 98–107 (2011).

Ehses, J. A. et al. Increased Number of Islet-Associated Macrophages in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes 56, 2356–2370 (2007).

Sunil, Y., Ramadori, G. & Raddatzc, D. Influence of NFkappaB inhibitors on IL-1beta-induced chemokine CXCL8 and -10 expression levels in intestinal epithelial cell lines: glucocorticoid ineffectiveness and paradoxical effect of PDTC. Int J Colorectal Dis 25, 323–333 (2010).

Breitbach, K. et al. Caspase-1 Mediates Resistance in Murine Melioidosis. Infect. Immun. 77, 1589–1595 (2009).

Oncul, O. et al. Effect of the function of polymorphonuclear leukocytes and interleukin-1 beta on wound healing in patients with diabetic foot infections. Journal of Infection 54, 250–256 (2007).

Andreasen, A. et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus is associated with impaired cytokine response and adhesion molecule expression in human endotoxemia. Intensive Care Medicine 36, 1548–1555 (2010).

Lamkanfi, M. et al. Glyburide inhibits the Cryopyrin/Nalp3 inflammasome. J Cell Biol 187, 61–70 (2009).

Rinchai, D. et al. Production of interleukin-27 by human neutrophils regulates their function during bacterial infection. Eur J Immunol 42, 3280–3290 (2012).

Dinarello, C. A. Interleukin-1 in the pathogenesis and treatment of inflammatory diseases. Blood 117, 3720–3732 (2011).

Jonsson, A., Hallengren, B., Rydberg, T. & Melander, A. Effects and serum levels of glibenclamide and its active metabolites in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 3, 403–409 (2001).

DeFronzo, R. A. Pharmacologic Therapy for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Annals of Internal Medicine 133, 73–74 (2000).

Hatanaka, E., Monteagudo, P. T., Marrocos, M. S. M. & Campa, A. Neutrophils and monocytes as potentially important sources of proinflammatory cytokines in diabetes. Clinical & Experimental Immunology 146, 443–447 (2006).

Morris, J. et al. Burkholderia pseudomallei Triggers Altered Inflammatory Profiles in a Whole-Blood Model of Type 2 Diabetes-Melioidosis Comorbidity. Infection and Immunity 80, 2089–2099 (2012).

Miao, E. A. et al. Innate immune detection of the type III secretion apparatus through the NLRC4 inflammasome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107, 3076–3080 (2010).

Ceballos-Olvera, I., Sahoo, M., Miller, M. A., Barrio, L. d. & Re, F. Inflammasome-dependent Pyroptosis and IL-18 Protect against Burkholderia pseudomallei Lung Infection while IL-1β Is Deleterious. PLoS Pathog 7, e1002452 (2011).

Sun, G. W., Lu, J., Pervaiz, S., Cao, W. P. & Gan, Y.-H. Caspase-1 dependent macrophage death induced by Burkholderia pseudomallei. Cellular Microbiology 7, 1447–1458 (2005).

Hertting, O. et al. Enhanced chemokine response in experimental acute Escherichia coli pyelonephritis in IL-1β-deficient mice. Clinical & Experimental Immunology 131, 225–233 (2003).

Opal, S. M. et al. Confirmatory interleukin-1 receptor antagonist trial in severe sepsis: a phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. The Interleukin-1 Receptor Antagonist Sepsis Investigator Group. Crit Care Med 25, 1115–1124 (1997).

Hodgson, K. A., Govan, B. L., Walduck, A. K., Ketheesan, N. & Morris, J. L. Impaired Early Cytokine Responses at the Site of Infection in a Murine Model of Type 2 Diabetes and Melioidosis Comorbidity. Infection and Immunity 81, 470–477 (2013).

Winters, M. P. et al. Carboxylic acid bioisosteres acylsulfonamides, acylsulfamides and sulfonylureas as novel antagonists of the CXCR2 receptor. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters 18, 1926–1930 (2008).

Spiller, F. et al. Hydrogen Sulfide Improves Neutrophil Migration and Survival in Sepsis via K + ATP Channel Activation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 182, 360–368 (2010).

Koh, G. C. K. W. et al. Glyburide Is Anti-inflammatory and Associated with Reduced Mortality in Melioidosis. Clinical Infectious Diseases 52, 717–725 (2011).

Shaw, R. J. et al. The Kinase LKB1 Mediates Glucose Homeostasis in Liver and Therapeutic Effects of Metformin. Science 310, 1642–1646 (2005).

Wen, H. et al. Fatty acid-induced NLRP3-ASC inflammasome activation interferes with insulin signaling. Nat Immunol 12, 408–415 (2011).

Alberti, K. G. & Zimmet, P. Z. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. in Report of WHO consultation: Part 1 Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med 15, 539–553 (1998).

Niopas, I. & Daftsios, A. C. A validated high-performance liquid chromatographic method for the determination of glibenclamide in human plasma and its application to pharmacokinetic studies. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis 28, 653–657 (2002).

Bailey, C. J. & Turner, R. C. Metformin. New England Journal of Medicine 334, 574–579 (1996).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the help of physicians and nurses at Khon Kaen Medical Care Center and Ms. Jeerawan Dhanasen in sample collection. We are grateful to Dr. Philip L. Felgner for kindly providing B. pseudomallei flagellin. We thank Professor Mark P. Stevens, Dr. Saskia Decuypere and Ms. Bianca Kessler for their helpful and critical comments. We thank Ms. Donporn Riyapa and Mr. Surachat Buddhisa for technical help during preliminary investigations and Ms. Vicki Harley for editorial help.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.K., G.B., M.A. and G.L. wrote the main manuscript text and C.K., D.R., K.U. and D.S. prepared figures 1–5 and supplementary figures S1–S5. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures S1-S5

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Kewcharoenwong, C., Rinchai, D., Utispan, K. et al. Glibenclamide reduces pro-inflammatory cytokine production by neutrophils of diabetes patients in response to bacterial infection. Sci Rep 3, 3363 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03363

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03363